The Battle of Tours - A Decisive Fight for Europe’s Future

- Read Later

The early medieval world of our ancestors was built upon struggles and decisive battles. The emerging nations united the broken tribes, expanded their borders, conquered their enemies, and often enough - fended off invaders. But rare are the battles that really left a long lasting impact that echoed through the generations that followed.

Rare are such conflicts that changed the history of the world with their importance and decided the future of us all for centuries to come. And one of those rare, world-changing battles is the Battle of Tours - fought in 732 AD between the Christian Frankish forces and the invading Muslim Umayyad Caliphate.

This fierce and destructive conflict, that shaped the future of Europe and echoed through time, was a great gamble, fought against all odds. But it remains as one of the biggest lessons of Europe’s past, and today we are going in detail about that fated day in 732.

A triumphant Charles Martel (mounted) faces Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi (right) at the Battle of Tours. Source: Bender235 / Public Domain .

The Prelude to the Battle of Tours

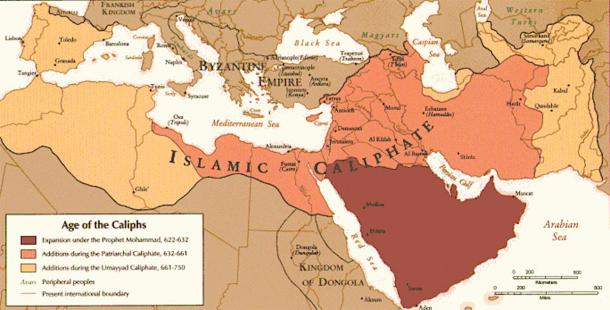

Around the very beginning of the 8 th century, in the year 700 AD, the Muslim Umayyad Caliphate was rapidly spreading its empire around the world. It was the second of the four great caliphates that emerged after the death of Muhammad and was one of the largest empires of the world at the time.

After conquering the lands of North Africa, they saw mainland Europe as the next prey for their conquests. From the shores of North Africa, they had a clear passage - in the form of the Gibraltar Strait. This would allow their forces to cross over onto the Iberian Peninsula , from which they would spread further inland.

At the time, Iberia was under the control of the Visigothic Kingdom, a centralized state under the rule of King Roderic. Nonetheless, the Umayyads crossed the strait in the year 711 AD, under the leadership of one Tariq ibn Ziyad, and soon after clashed with the Visigothic army in the Battle of Guadalete, in the same year, in the very south of Iberia.

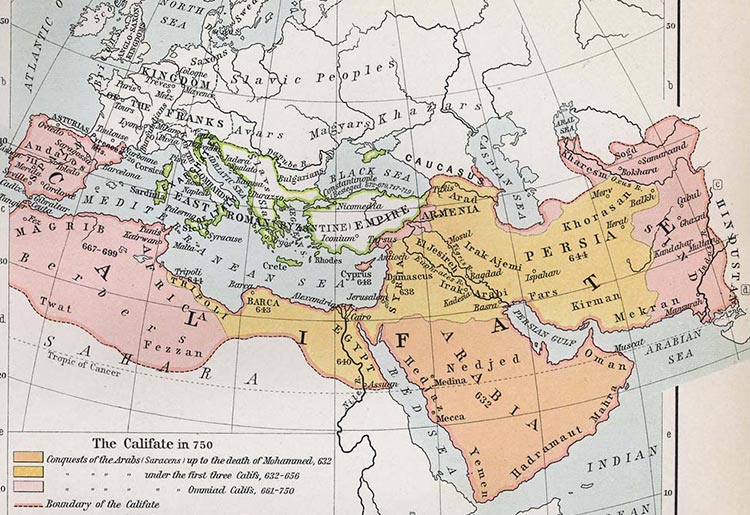

The "Age of the Caliphs", shows the Umayyad dominance stretched from the Middle East to the Iberian Peninsula, including the port of Narbonne, c. 720. (McZusatz / Public Domain )

At the time of the Umayyad invasion, King Roderic was far in the north, attempting to fight a Basque rebellion. This unfortunately placed him in a bad situation, as he was forced to a long march south, to face this much bigger enemy. In the end, the Visigoths were defeated in the face of the overwhelming Muslim cavalry.

In the battle, King Roderic and most of the nobles of his kingdom lost their lives, which allowed the Umayyads to effectively conquer Iberia, step by step. This they managed in just a little under seven years. And once Iberia was theirs, Frankish Gaul was just a step away.

The only thing that divided the Umayyads from their prey - the Frankish Kingdom - were the Pyrenees Mountains . This was a fitting natural barrier - but it was in no way untraversable. In time, the Umayyads began crossing over and making incursions into the very south of Gaul. By 720 they conquered the southern province of Septimania.

In the following year, they focused on the large city to the immediate west, Toulouse, which they besieged. This siege was brought to an end by the prominent Frankish Duke Odo - who managed to overwhelm the Umayyad forces outside Toulouse and defeat them. Nonetheless, large numbers of Umayyads kept crossing over the Pyrenees and laying waste to the southern provinces of Gaul.

The Duchy of Aquitaine laid in the south and faced the brunt of this invasion. Its largest towns, Bordeaux and Toulouse were ravaged, and in no time the invaders reached even the Duchy of Burgundy to its north.

But it wasn’t until 732 that the Umayyad Caliphate truly amassed its forces with proper conquering intentions and adequate strength. The man that was at the head of this force was Abdul Rahman al Ghafiqi, the then-Governor General of Muslim Iberia. He led his forces across the Pyrenees once again and plundered the land and all the cities he came across.

- Unique Iberian Male DNA was Practically Wiped Out by Immigrant Farmers 4500 Years Ago [New Study]

- Raiders of Hispania: Unravelling the Secrets of the Suebi

- Was the First Islamic Siege of Constantinople (674 – 678 AD) a Historical Misnomer?

Abdul Rahman al Ghafiqi led his troops over the Pyrenees Mountains toward the Battle of Tours. (Jean-Christophe BENOIST / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

The Umayyads greatly coveted riches, and their main activity during this conquest was plunder. After completely ransacking Bordeaux once again, the Umayyad forces faced Duke Odo once more. Odo led his army in an attempt to stop the invasion as he did a few years before.

But this time, he was terribly outnumbered and outmaneuvered, and his forces were crushed. Realizing the gravity of the situation, and that his own lands of Aquitaine were overrun, Odo fled to the north seeking assistance from the de-facto ruler of the Frankish Kingdom - Charles Martel.

Before the Umayyad invasion Odo and Charles were enemies. Charles sought to expand his lordship over Aquitaine and Odo saw the Franks as invaders. But with this new and much greater threat, Odo had no choice but to seek help from the Franks. Charles Martel agreed to join up with him, but the “price” was Odo’s acceptance of Frankish overlordship. Odo agreed.

The Hammer Enters the Fray

Charles Martel was a seasoned ruler and a battle hardened veteran. His troops were equally experienced having been in constant clashes along the eastern borders of their kingdom, fighting neighboring tribes.

Charles also understood how important the situation was and began gathering his levies from all over the north. And he would show his shrewdness as a battle commander, when he carefully understood the intentions of his enemy.

Meanwhile, the Umayyad forces moved slowly across the Frankish lands, their forces spread into war parties that ravaged the countryside and amassed an enormous amount of plunder. This “greedy” focus on war booty would greatly influence their future undoing. They had to take their time, as they greatly depended on the crop season for their food source.

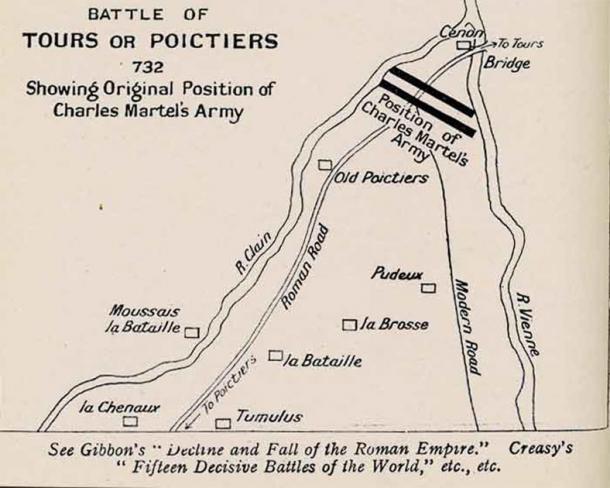

But their destination was clear to Charles Martel. It was the rich city of Tours - prominent and wealthy, filled with abbeys of great importance. Thus, Charles placed his Frankish forces directly on the path of the coming Umayyads. He situated his army roughly in between the city of Tours and the ravaged town of Poitiers further south.

The Franks were placed close to the confluence of rivers Clain and Vienne, on a slightly elevated and forested hill. Charles Martel deliberately and shrewdly chose this position. First of all - he was outnumbered and knew it.

Map of the Battle of Tours with the position of Charles Martel's army. (Evzen M / Public Domain )

Thus he chose the cover of the forest to displace his troops and hide his number in hope to not reveal his disadvantage. Secondly - he chose a place where the Umayyads would have to enter into battle, as the only crossing over the rivers was behind the Frankish forces. Thirdly - the forest protected his troops - mainly the second lines - from the full brunt of a cavalry charge, and somewhat protected his sides from flanking attacks.

When the Umayyads approached the assembled Christian army, their leader Abdul Rahman al Ghafiqi - also a seasoned commander - knew that Charles Martel took the upper hand, by choosing his preferred place of battle. Even so, al Ghafiqi trusted in his strength and deployed for battle.

One thing he must have noticed is the difference in the troops - Umayyads relied heavily on cavalry, while the Franks were mostly footmen. But he failed to take several things into account.

The Muslim cavalry was lightly armored - they preferred to adorn themselves with chainmail and not much else in terms of armor. Riches and trinkets were much more to their liking.

They also rode willful Arabic horses, which were difficult to break in, and thus not the truly perfect cavalry mounts. Some historians also mention that this cavalry was in large part armed with spears - which were unseasoned and would break on first impact.

The Muslim cavalry rode willful Arabic horses during the Battle of Tours. (Trzęsacz / Public Domain )

On the other hand, the Frankish infantry was thoroughly seasoned. Most of the army were veterans, with only a small part of fresh recruits reserved in the second lines. They were well armored for the time, and well-armed as well. They stood packed in tight lines and ready for a cavalry charge.

But the battle did not begin immediately. The opposing forces “tested the waters”, with sporadic small skirmishes going on for seven days.

This was in truth a deliberate stalling from al Ghafiqi, who waited for his whole army to assemble fully. In the end, with the Umayyads fearing the approaching winter, they commenced battle on the seventh day - on the 10th of October 732 AD.

The Umayyad Wave That Broke On the Frankish Rock

The Umayyad commander, al Ghafiqi, heavily relied on his cavalry, even though he didn’t possess much knowledge about the assembled enemy. He sent waves of cavalry charges in an attempt to break the Frankish lines - but this did not happen. The seasoned Franks were tightly packed - shoulder to shoulder - and withstood all assaults.

The rare combination of slight elevation, good arms and armor, and tree cover allowed them to hold their ground - when it was almost impossible for infantry to hold against cavalry in medieval times. Even when some small parts of the line faltered and broke under the cavalry, the fresh second lines were quick to react - sealing the gap.

Frankish knight fighting against an Umayyad horseman. (Helix84 / Public Domain )

As the battle went on in that way, Duke Odo commenced a crucial flanking operation that greatly tipped the scales in Frankish favor. He gathered a cavalry force and flanked wide - reaching the distant Muslim encampment - i.e. their rear. This was where the Umayyad tents were and all of their abundant plunder.

Odo managed to inflict great losses here, retrieve the precious plunder, free around 200 captive Franks, and draw the eye of the enemy. But what happened next was more than he hoped for. Upon realizing that their camp and their plunder were under attack, many Umayyad units from the central battlefield rushed back in a frenzy to save their loot.

This was an unprecedented situation, one that al Ghafiqi never expected. His attempts at rallying his troops were in vain, and Charles Martel - who knew exactly what he was doing - seized this opportunity.

As the Umayyad forces dissipated to retrieve the loot, he swung his forces from left, right, and center, and engaged in both pursuit and encirclement. The remaining body of the Umayyads was surrounded and suffered immense casualties.

The chief of these was al Ghafiqi himself - who fell in battle while attempting to rally his troops. Meanwhile, Duke Odo swung north again and cut off the fleeing Umayyads, inflicting great losses. In effect, the Umayyad forces fled.

- The Heroic Story of Roland: A Valiant Knight With an Unbreakable Sword

- Cataphracts: Armored Warriors and their Horses of War

- The Mighty Magyars, a Medieval Menace to the Holy Roman Empire

Charles Martel gathered his cavalry at Battle of Tours and attacked the Umayyad encampment. (Levan Ramishvili / Public Domain )

Now, Charles Martel expected a second day of battles and remained in his position, treating the wounded and re-organizing. But another day never came. The Umayyads, with their commander dead, could not successfully organize another attack or choose a fitting leader. They had suffered great losses as well.

Charles Martel feared an ambush and would not descend from the hill at any cost. Eventually, he sent out extensive reconnaissance parties to survey the Umayyad forces - but only to learn that there were none. They had gathered all the remaining plunder they could and fled during the night - extremely hastily. They had returned to Iberia.

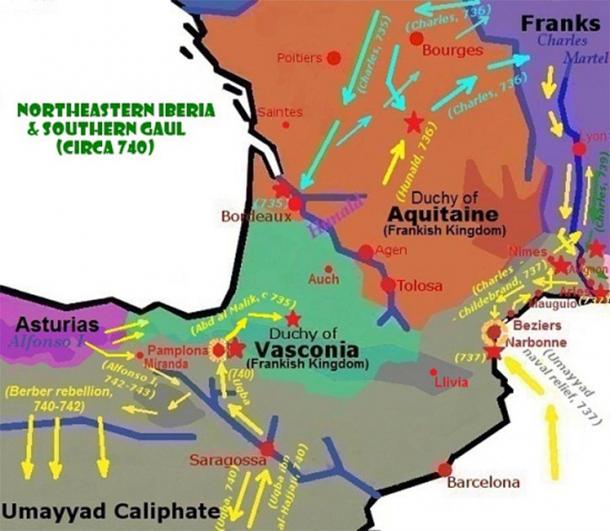

Charles Martel won a crushing and glorious victory that cemented his reputation of a noble and capable leader. He was praised all across Europe as the savior of the Christendom and the “Hammer that Broke the Muslims”. Thus he earned his nickname - Martel - meaning Charles the Hammer.

He subsequently expanded his rule over Aquitaine and successfully isolated the invaders to the southern region of Septimania, where they remained for another 27 years and were completely unable to break through. Charles’ wealth, influence, power, and ability led to the emergence of the Carolingian dynasty , which would rise and last for centuries to follow.

Charles Martel's military campaigns in Aquitaine, Septimania, and Provence after the Battle of Tour-Poitiers (734–742). (Iñaki LLM / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Changing the Future of the World

The Europe of the early 18 th century desperately needed a capable and strong commander that would stop the Muslim Umayyad invaders dead in their tracks. And that commander was Charles Martel. He stood up to ravaging flood of conquerors and using his superior tactics, shrewdness, and reputation, he managed to win a crushing battle - against all odds. Like a beacon that kept burning throughout a storm, his Frankish warriors defied their enemy in battle. And it is this battle that changed the course of European history, and with that - the history of the World.

Top image: Medieval soldier at war. Credit: Andrey Kiselev / Adobe Stock

By Aleksa Vučković

Creasy, E. 2016. The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World . Enhanced Media.

Neiberg, M. 2003. Warfare in World History . Taylor & Francis.

Scott, J. 2011. Battle of Tours - A New Look at an Old Enemy . eBookIt.

I am a published author of over ten historical fiction novels, and I specialize in Slavic linguistics. Always pursuing my passions for writing, history and literature, I strive to deliver a thrilling and captivating read that touches upon history's most... Read More

Related Articles on Ancient-Origins

Muslim Invasions of Western Europe: The 732 Battle of Tours

- Battles & Wars

- Key Figures

- Arms & Weapons

- Naval Battles & Warships

- Aerial Battles & Aircraft

- French Revolution

- Vietnam War

- World War I

- World War II

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/khickman-5b6c7044c9e77c005075339c.jpg)

- M.A., History, University of Delaware

- M.S., Information and Library Science, Drexel University

- B.A., History and Political Science, Pennsylvania State University

The Battle of Tours was fought during the Muslim invasions of Western Europe in the 8th century.

Armies & Commanders at the Battle of Tours

- Charles Martel

- 20,000-30,000 men

- Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi

- unknown, but perhaps as high as 80,000 men

Battle of Tours - Date

Martel's triumph at the Battle of Tours occurred on October 10, 732.

Background on the Battle of Tours

In 711, the forces of the Umayyad Caliphate crossed into the Iberian Peninsula from Northern Africa and quickly began overrunning the region's Visigothic Christian kingdoms. Consolidating their position on the peninsula, they used the area as a platform for commencing raids over the Pyrenees into modern-day France. Initially meeting little resistance, they were able to gain a foothold and the forces of Al-Samh ibn Malik established their capital at Narbonne in 720. Commencing attacks against Aquitaine, they were checked at the Battle of Toulouse in 721. This saw Duke Odo defeat the Muslim invaders and kill Al-Samh. Retreating to Narbonne, Umayyad troops continued raiding west and north reached as far as Autun, Burgundy in 725.

In 732, Umayyad forces led by the governor of Al-Andalus, Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi, advanced in force into Aquitaine. Meeting Odo at the Battle of the River Garonne they won a decisive victory and commenced sacking the region. Fleeing north, Odo sought aid from the Franks. Coming before Charles Martel, the Frankish mayor of the palace, Odo was promised aid only if he promised to submit to the Franks. Agreeing, Martel began raising his army to meet the invaders. In the years previous, having assessed the situation in Iberia and the Umayyad attack on Aquitaine , Charles came to believe that a professional army, rather than raw conscripts, was needed to defend the realm from invasion. To raise the money necessary to build and train an army that could withstand the Muslim horsemen, Charles began seizing Church lands, earning the ire of the religious community.

Battle of Tours - Moving to Contact

Moving to intercept Abdul Rahman, Charles used secondary roads to avoid detection and allow him to select the battlefield. Marching with approximately 30,000 Frankish troops he assumed a position between the towns of Tours and Poitiers. For the battle, Charles selected a high, wooded plain which would force the Umayyad cavalry to charge uphill through unfavorable terrain. This included trees in front of the Frankish line which would aid in breaking up cavalry attacks. Forming a large square, his men surprised Abdul Rahman, who did not expect to encounter a large enemy army and forced the Umayyad emir to pause for a week to consider his options. This delay benefited Charles as it allowed him to summon more of his veteran infantry to Tours.

Battle of Tours - The Franks Stand Strong

As Charles reinforced, the increasingly cold weather began to prey on the Umayyads who were unprepared for the more northern climate. On the seventh day, after gathering all of his forces, Abdul Rahman attacked with his Berber and Arab cavalry. In one of the few instances where medieval infantry stood up to cavalry, Charles' troops defeated repeated Umayyad attacks. As the battle waged, the Umayyads finally broke through the Frankish lines and attempted to kill Charles. He was promptly surrounded by his personal guard who repulsed the attack. As this was occurring, scouts that Charles had sent out earlier were infiltrating the Umayyad camp and freeing prisoners and enslaved people.

Believing that the plunder of the campaign was being stolen, a large part of the Umayyad army broke off the battle and raced to protect their camp. This departure appeared as a retreat to their comrades who soon began to flee the field. While attempting to stop the apparent retreat, Abdul Rahman was surrounded and killed by Frankish troops. Briefly pursued by the Franks, the Umayyad withdrawal turned into a full retreat. Charles re-formed his troops expecting another attack the next day, but to his surprise, it never came as the Umayyads continued their retreat all the way to Iberia.

While exact casualties for the Battle of Tours are not known, some chronicles relate that Christian losses numbered around 1,500 while Abdul Rahman suffered approximately 10,000. Since Martel's victory, historians have argued over the battle's significance with some stating that his victory saved Western Christendom while others feel that its repercussions were minimal. Regardless, the Frankish victory at Tours, along with subsequent campaigns in 736 and 739, effectively stopped the advance of Muslim forces from Iberia allowing the further development of the Christian states in Western Europe.

- Battle of Tours: 732

- Decisive Battles: Battle of Tours

- Battle of Tours: Primary Sources

- Biography of Charles Martel, Frankish Military Leader and Ruler

- What Was the Umayyad Caliphate?

- Second Punic War: Battle of the Trebia

- Hundred Years' War: Battle of Poitiers

- The Crusades: Battle of Hattin

- Invasions of England: Battle of Hastings

- What Effect Did the Crusades Have on the Middle East?

- Teutonic War: Battle of Grunwald (Tannenberg)

- Charlemagne: Battle of Roncevaux Pass

- Key Events in French History

- Mongol Invasions: Battle of Legnica

- Muslim Empire: Battle of Siffin

- Indian Wars: Lt. Colonel George A. Custer

- Roman Empire: Battle of the Milvian Bridge

- Napoleonic Wars: Battle of Austerlitz

- Little-Known Asian Battles That Changed History

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

The History Hit Miscellany of Facts, Figures and Fascinating Finds

Battle of Tours: Its Significance and Historical Implications

Celeste Neill

01 oct 2018.

On 10 October 732 Frankish General Charles Martel crushed an invading Muslim army at Tours in France , decisively halting the Islamic advance into Europe.

The Islamic advance

After the death of the Prophet Muhammed in 632 AD the speed of the spread of Islam was extraordinary, and by 711 Islamic armies were poised to invade Spain from North Africa. Defeating the Visigothic kingdom of Spain was a prelude to increasing raids into Gaul, or modern France, and in 725 Islamic armies reached as far north as the Vosgues mountains near the modern border with Germany .

Opposing them was the Merovingian Frankish kingdom , perhaps the foremost power in western Europe. However given the seemingly unstoppable nature of the Islamic advance into the lands of the old Roman Empire further Christian defeats seemed almost inevitable.

Map of the Umayyad Caliphate in 750 AD. Image credit: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In 731 Abd al-Rahman, a Muslim warlord north of the Pyrenees who answered to his distant Sultan in Damascus, received reinforcements from North Africa. The Muslims were preparing for a major campaign into Gaul.

The campaign commenced with an invasion of the southern kingdom of Aquitaine, and after defeating the Aquitanians in battle Abd al-Rahman’s army burned their capital of Bordeaux in June 732. The defeated Aquitanian ruler Eudes fled north to the Frankish kingdom with the remnants of his forces in order to plead for help from a fellow Christian, but old enemy: Charles Martel .

Martel’s name meant “the hammer” and he had already many successful campaigns in the name of his lord Thierry IV, mainly against other Christians such as the unfortunate Eudes, who he met somewhere near Paris . Following this meeting Martel ordered a ban , or general summons, as he prepared the Franks for war.

14th century depiction of Charles Martel (middle). Image credit: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Battle of Tours

Once his army had gathered, he marched to the fortified city of Tours, on the border with Aquitaine, to await the Muslim advance. After three months of pillaging Aquitaine, al-Rahman obliged.

His army outnumbered that of Martel but the Frank had a solid core of experienced armoured heavy infantry who he could rely upon to withstand a Muslim cavalry charge.

With both armies unwilling to enter the bloody business of a Medieval battle but the Muslims desperate to pillage the rich cathedral outside the walls of Tours, an uneasy standoff prevailed for seven days before the battle finally began. With winter coming al-Rahman knew that he had to attack.

The battle began with thundering cavalry charges from Rahman’s army but, unusually for a Medieval battle, Martel’s excellent infantry weathered the onslaught and retained their formation. Meanwhile, Prince Eudes’ Aquitanian cavalry used superior local knowledge to outflank the Muslim armies and attack their camp from the rear.

Christian sources then claim that this caused many Muslim soldiers to panic and attempt to flee to save their loot from the campaign. This trickle became a full retreat, and the sources of both sides confirm that al-Rahman died fighting bravely whilst trying to rally his men in the fortified camp.

The battle then ceased for the night, but with much of the Muslim army still at large Martel was cautious about a possible feigned retreat to lure him out into being smashed by the Islamic cavalry. However, searching the hastily abandoned camp and surrounding area revealed that the Muslims had fled south with their loot. The Franks had won.

Despite the deaths of al-Rahman and an estimated 25,000 others at Tours, this war was not over. A second equally dangerous raid into Gaul in 735 took four years to repulse, and the reconquest of Christian territories beyond the Pyrenees would not begin until the reign of Martel’s celebrated grandson Charlemagne.

Martel would later found the famous Carolingian dynasty in Frankia, which would one day extend to most of western Europe and spread Christianity into the east.

Tours was a hugely important moment in the history of Europe, for though the battle of itself was perhaps not as seismic as some have claimed, it stemmed the tide of Islamic advance and showed the European heirs of Rome that these foreign invaders could be defeated.

You May Also Like

Mac and Cheese in 1736? The Stories of Kensington Palace’s Servants

The Peasants’ Revolt: Rise of the Rebels

10 Myths About Winston Churchill

Medusa: What Was a Gorgon?

10 Facts About the Battle of Shrewsbury

5 of Our Top Podcasts About the Norman Conquest of 1066

How Did 3 People Seemingly Escape From Alcatraz?

5 of Our Top Documentaries About the Norman Conquest of 1066

1848: The Year of Revolutions

What Prompted the Boston Tea Party?

15 Quotes by Nelson Mandela

The History of Advent

Battle of Tours

Frankish victory over the umayyad caliphate, 732 / from wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, dear wikiwand ai, let's keep it short by simply answering these key questions:.

Can you list the top facts and stats about Battle of Tours?

Summarize this article for a 10 year old

The Battle of Tours , [6] also called the Battle of Poitiers and the Battle of the Highway of the Martyrs ( Arabic : معركة بلاط الشهداء , romanized : Maʿrakat Balāṭ ash-Shuhadā' ), [7] was fought on 10 October 732, and was an important battle during the Umayyad invasion of Gaul . It resulted in the victory for the Frankish and Aquitanian forces, [8] [9] led by Charles Martel , over the invading Muslim forces of the Umayyad Caliphate , led by Abd al-Rahman al-Ghafiqi , governor of al-Andalus . Several historians, such as Edward Gibbon , have credited the Christian victory in the battle as an important factor in curtailing the Islamization of Western Europe . [10]

Kingdom of the Franks ( Western Franks ) [5]

- Vascones [5]

- Charles Martel [5]

- Odo, Duke of Aquitaine [5]

Details of the battle, including the number of combatants and its exact location, are unclear from the surviving sources. Most sources agree that the Umayyads had a larger force and suffered heavier casualties. Notably, the Frankish troops apparently fought without heavy cavalry . [11] The battlefield was located somewhere between the cities of Poitiers and Tours , in northern Aquitaine in western France, near the border of the Frankish realm and the then-independent Duchy of Aquitaine under Odo the Great .

Al-Ghafiqi was killed in combat, and the Umayyad army withdrew after the battle. The battle helped lay the foundations of the Carolingian Empire and Frankish domination of western Europe for the next century. Most historians agree that "the establishment of Frankish power in western Europe shaped that continent's destiny and the Battle of Tours confirmed that power." [12]

The Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayads were the first Muslim dynasty — that is, they were the first rulers of the Islamic Empire to pass down power within their family.

According to tradition, the Umayyad family (also known as the Banu Abd-Shams) and Muhammad [saw] both descended from a common ancestor, Abd Manaf ibn Qusai, and they originally came from the city of Mecca . Muhammad [saw] descended from Abd Manāf via his son Hashim, while the Umayyads descended from Abd Manaf via a different son, Abd-Shams, whose son was Umayya. The two families are therefore considered to be different clans (those of Hashim and of Umayya, respectively) of the same tribe (that of the Quraish).

The shift in power to Damascus, the Umayyad capital city, was to have profound effects on the development of Islamic history. For one thing, it was a tacit recognition of the end of an era. The first four caliphs had been without exception Companions of the Prophet – pious, sincere men who had lived no differently from their neighbors and who preserved the simple habits of their ancestors despite the massive influx of wealth from the conquered territories. Even ‘Uthman, whose policies had such a divisive effect, was essentially dedicated more to the concerns of the next world than of this. With the shift to Damascus much was changed.

In the early days of Islam , the extension of Islamic rule had been based on an uncomplicated desire to spread the Word of God. Although the Muslims used force when they met resistance they did not compel their enemies to accept Islam. On the contrary, the Muslims permitted Christians and Jews to practice their own faith and numerous conversions to Islam were the result of exposure to a faith that was simple and inspiring.

With the advent of the Umayyads, how ever, secular concerns and the problems inherent in the administration of what, by then, was a large empire began to dominate the attention of the caliphs, often at the expense of religious concerns – a development that disturbed many devout Muslims. This is not to say that religious values were ignored; on the contrary, they grew in strength for centuries. But they were not always at the forefront and from the time of Mu’awiyah the caliph’s role as “Defender of the Faith” increasingly required him to devote attention to the purely secular concerns which dominate so much of every nation’s history. Muiawiyah was an able administrator, and even his critics concede that he possessed to a high degree the much-valued quality of hilm – a quality which may be defined as “civilized restraint” and which he himself once described in these words:

I apply not my sword where my lash suffices, nor my lash where my tongue is enough. And even if there be one hair binding me to my fellowmen, I do not let it break: when they pull I loosen, and if they loosen I pull.

Nevertheless, Mu’awiyah was never able to reconcile the opposition to his rule nor solve the conflict with the Shi’is. These problems were not unmanageable while Mu’awiyah was alive, but after he died in 680 the partisans of ‘Ali resumed a complicated but persistent struggle that plagued the Umayyads at home for most of the next seventy years and in time spread into North Africa and Spain.

The Umayyads, however, did manage to achieve a degree of stability, particularly after ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan succeeded to the caliphate in 685. Like the Umayyads who preceded him, ‘Abd al-Malik was forced to devote a substantial part of his reign to political problems. But he also introduced much needed reforms. He directed the cleaning and reopening of the canals that irrigated the Tigris-Euphrates Valley – a key to the prosperity of Mesopotamia since the time of the Sumerians – introduced the use of the Indian water buffalo in the riverine marshes, and minted a standard coinage which replaced the Byzantine and Sassanid coins, until then the sole currencies in circulation. ‘Abd al-Malik’s organization of government agencies was also important; it established a model for the later elaborate bureaucracies of the ‘Abbasids and their successor states. There were specific agencies charged with keeping pay records; others concerned themselves with the collection of taxes. ‘Abd al-Malik established a system of postal routes to expedite his communications throughout the far flung empire. Most important of all, he introduced Arabic as the language of administration, replacing Greek and Pahlavi. Under ‘Abd al-Malik, the Umayyads expanded Islamic power still further. To the east they extended their influence into Transoxania, an area north of the Oxus River in today’s Soviet Union, and went on to reach the borders of China. To the west, they took North Africa, in a continuation of the campaign led by ‘Uqbah ibn Nafi’ who founded the city of Kairouan – in what is now Tunisia – and from there rode all the way to the shores of the Atlantic Ocean. These territorial acquisitions brought the Arabs into contact with previously unknown ethnic groups who embraced Islam and would later influence the course of Islamic history. The Berbers of North Africa, for example, who resisted Arab rule but willingly embraced Islam, later joined Musa ibn Nusayr and his general, Tariq ibn Ziyad, when they crossed the Strait of Gibraltar to Spain. The Berbers later also launched reform movements in North Africa which greatly influenced the Islamic civilization. In the East, Umayyad rule in Transoxania brought the Arabs into contact with the Turks who, like the Berbers, embraced Islam and, in the course of time, became its staunch defenders. Umayyad expansion also reached the ancient civilization of India, whose literature and science greatly enriched Islamic culture.

In Europe, meanwhile, the Arabs had passed into Spain, defeated the Visigoths, and by 713 had reached Narbonne in France. In the next decades, raiding parties continually made forays into France and in 732 reached as far as the Loire Valley, only 170 miles from Paris. There, at the Battle of Tours, or Poitiers, the Arabs were finally turned back by Charles Martel. One of the Umayyad caliphs who attained greatness was ‘Umar ibn ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, a man very different from his predecessors. Although a member of the Umayyad family, ‘Umar had been born and raised in Medina, where his early contact with devout men had given him a concern for spiritual as well as political values. The criticisms that religious men in Medina and elsewhere had voiced of Umayyad policy – particularly the pursuit of worldly goals – were not lost on ‘Umar who, reversing the policy of his predecessors, discontinued the levy of a poll tax on converts. This move reduced state income substantially, but as there was a clear precedent in the practice of the great ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab, the second caliph, and as ‘Umar ibn ‘Abd al-‘Aziz was determined to bring government policy more in line with the practice of the Prophet, even enemies of his regime had nothing but praise for this pious man. The last great Umayyad caliph was Hisham, the fourth son of ‘Abd al-Malik to succeed to the caliphate. His reign was long – from 724 to 743 – and during it the Arab empire reached its greatest extent. But neither he nor the four caliphs who succeeded him were the statesmen the times demanded when, in 747, revolutionaries in Khorasan unfurled the black flag of rebellion that would bring the Umayyad Dynasty to an end. Although the Umayyads favored their own region of Syria, their rule was not without accomplishments. Some of the most beautiful existing buildings in the Muslim world were constructed at their instigation – buildings such as the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, and the lovely country palaces in the deserts of Syria, Jordan, and Iraq. They also organized a bureaucracy able to cope with the complex problems of a vast and diverse empire and made Arabic the language of government. The Umayyads, furthermore, encouraged such writers as ‘Abd Allah ibn al-Muqaffa’ and ‘Abd al-Hamid ibn Yahya al-Katib, whose clear, expository Arabic prose has rarely been surpassed.

For all that, the Umayyads, during the ninety years of their leadership, rarely shook off their empire’s reputation as a mulk – that is, a worldly kingdom – and in the last years of the dynasty, their opponents formed a secret organization devoted to pressing the claims to the caliphate put forward by a descendant of al-‘Abbas ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib, an uncle of the Prophet. By skillful preparation, this organization rallied to its cause many mutually hostile groups in Khorasan and Iraq and proclaimed Abu al-‘Abbas caliph. Marwan ibn Muhammad, the last Umayyad caliph, was defeated and the Syrians, still loyal to the Umayyads, were put to rout.

Under ʿAbd al-Malik (reigned 685–705) the Umayyad caliphate reached its peak. Muslim armies overran most of Spain in the west and invaded Mukrān and Sindh in India, while in Central Asia the Khorāsānian garrisons conquered Bukhara, Samarkand, Khwārezm, Fergana, and Tashkent. In an extensive program of Arabization, Arabic became the official state language; the financial administration of the empire was reorganized, with Arabs replacing Persian and Greek officials; and a new Arabic coinage replaced the former imitations of Byzantine and Sāsānian coins. Communications improved with the introduction of a regular post service from Damascus to the provincial capitals, and architecture flourished (see, for example, khan; desert palace; mihrab).

The decline began with the disastrous defeat of the Syrian army by the Byzantine emperor Leo III (the Isaurian; 717). Then the fiscal reforms of the pious ʿUmar II (reigned 717–720), intended to mollify the increasingly discontented mawālī (non-Arab Muslims) by placing all Muslims on the same footing without respect of nationality, led to the financial crisis, while the recrudescence of feuds between southern (Kalb) and northern (Qays) Arab tribes seriously reduced military power.

Hishām ibn ʿAbd Al-Malik (reigned 724–743) was able to stem the tide temporarily. As the empire was reaching the limits of expansion—the Muslim advance into France was decisively halted at Poitiers (732), and Arab forces in Anatolia were destroyed (740)—frontier defenses, manned by Syrian troops, were organized to meet the challenge of Turks in Central Asia and Berbers (Imazighen) in North Africa. But in the years following Hishām’s death, feuds between the Qays and the Kalb erupted into major revolts in Syria, Iraq, and Khorāsān (745–746), while the mawālī became involved with the Hāshimiyyah, a religio-political sect that denied the legitimacy of Umayyad rule. In 749 the Hāshimiyyah, aided by the western provinces, proclaimed as caliph Abū al-ʿAbbās al-Saffāḥ, who thereby became the first of the ʿAbbāsid dynasty.

The last Umayyad, Marwān II (reigned 744–750), was defeated at the Battle of the Great Zāb River (750). Members of the Umayyad house were hunted down and killed, but one of the survivors, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān, escaped and established himself as a Muslim ruler in Spain (756), founding the dynasty of the Umayyads in Córdoba.

The Umayyad caliphate was marked both by territorial expansion and by the administrative and cultural problems that such expansion created. Despite some notable exceptions, the Umayyads tended to favor the rights of the old Arab families, and in particular their own, over those of newly converted Muslims (mawali). Therefore they held to a less universalist conception of Islam than did many of their rivals. As G.R. Hawting has written, “Islam was in fact regarded as the property of the conquering aristocracy.”

During the period of the Umayyads, Arabic became the administrative language. State documents and currency were issued in the language. Mass conversions brought a large influx of Muslims to the caliphate. The Umayyads also constructed famous buildings such as the Dome of the Rock at Jerusalem, and the Umayyad Mosque at Damascus.

According to one common view, the Umayyads transformed the caliphate from a religious institution (during the rashidun) to a dynastic one. However, the Umayyad caliphs do seem to have understood themselves as the representatives of God on earth, and to have been responsible for the “definition and elaboration of God’s ordinances, or in other words the definition or elaboration of Islamic law.”

The Umayyads have met with a largely negative reception from later Islamic historians, who have accused them of promoting a kingship (mulk, a term with connotations of tyranny) instead of a true caliphate (khilafa). In this respect it is notable that the Umayyad caliphs referred to themselves not as khalifat rasul Allah (“successor of the messenger of God”, the title preferred by the tradition), but rather as khalifat Allah (“deputy of God”). The distinction seems to indicate that the Umayyads “regarded themselves as God’s representatives at the head of the community and saw no need to share their religious power with, or delegate it to, the emergent class of religious scholars.”In fact, it was precisely this class of scholars, based largely in Iraq, that was responsible for collecting and recording the traditions that form the primary source material for the history of the Umayyad period. In reconstructing this history, therefore, it is necessary to rely mainly on sources, such as the histories of Tabari and Baladhuri, that were written in the Abbasid court at Baghdad.

Modern Arab nationalism regards the period of the Umayyads as part of the Arab Golden Age which it sought to emulate and restore. This is particularly true of Syrian nationalists and the present-day state of Syria, centered like that of the Umayyads on Damascus. White, one of the four Pan-Arab colors which appear in various combinations on the flags of most Arab countries, is considered as representing the Umayyads.

Digital Islamic Library

- Facebook 4.1k Followers

- Twitter 3.7k Followers

Timeline of Islamic history

Join our blog.

Signup today and be the first to get notified on new articles!

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Join Our Blog :)

Signup today for free and be the first to get notified on new articles In shaa Allah!

Pin It on Pinterest

Battle of Tours (732 A.D.)

The Battle of Tours (often called the Battle of Poitiers, but not to be confused with the Battle of Poitiers, 1356) was fought on October 10, 732 between forces under the Frankish leader Charles Martel and a massive invading Islamic army led by Emir Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi Abd al Rahman, near the city of Tours, France. During the battle, the Franks defeated the Islamic army and Emir Abd er Rahman was killed. This battle stopped the northward advance of Islam from the Iberian peninsula, and is considered by most historians to be of macrohistorical importance, in that it halted the Islamic conquests, and preserved Christianity as the controlling faith in Europe, during a period in which Islam was overrunning the remains of the old Roman and Persian Empires.

Franks, led by Charles Martel. Estimates of the Frankish army defending Gaul vary, but by most accounts were between 15,000 and 75,000. Losses according to St. Denis were about 1,500.

Muslims, between 60,000 and 400,000 cavalry, (most likely closer to the lower number) under Abd er Rahman; besides source differences, this army is difficult to estimate in size, since it was often fractured into raiding parties to carry out the pillaging and plundering of various richly cultured Frankish centers; however, the entire Muslim army was present at Tours by Arab accounts. During the six days he waited to begin the Battle, Abd er Rahman recalled all those columns raiding and pillaging, so that on the seventh day, when by both eastern and western accounts the Battle began, both armies were at full strength.

The Muslims in northern Spain had easily overrun Septimania, had set up a capital at Narbonne which they called Arbuna, giving its largely Arian inhabitants honorable terms, and quickly pacified the south and for some years threatened Frankish territories. Duke Odo of Aquitaine, also known as Eudes the Great, had decisively defeated a major invasion force in 721 at the Battle of Toulouse, but Arab raids continued, in 725 reaching as far as the city of Autun in Burgundy. Threatened by both the Arabs in the south and by the Franks in the north, in 730 Eudes allied himself with Uthman ibn Naissa, called "Munuza" by the Franks, the Berber emir in what would later become Catalonia. As a gage, Uthman was given Eudes's daughter Lampade in marriage to seal the alliance, and Arab raids across the Pyrenees, Eudes' southern border, ceased [1].

However, the next year, Uthman rebelled against the governor of al-Andalus, Abd er Rahman. Abd er Rahman quickly crushed the revolt, and next directed his attention against the traitor's former ally, Eudes. According to one unidentified Arab, "That army went through all places like a desolating storm." Duke Eudes (called King by some), collected his army at Bordeaux, but was defeated, and Bordeaux was plundered. The slaughter of Christians at the River Garonne was evidently horrific; Isidorus Pacensis commented that "solus Deus numerum morientium vel pereuntium recognoscat", 'God alone knows the number of the slain' (Chronicon). The Muslim horsemen then utterly devastated that portion of Gaul, their own histories saying the "faithful pierced through the mountains, tramples over rough and level ground, plunders far into the country of the Franks, and smites all with the sword, insomuch that when Eudo came to battle with them at the River Garonne, and fled." Eudes appealed to the Franks for assistance, which Charles Martel only granted after Eudes agreed to submit to Frankish authority.

In 732, the Arab advance force was proceeding north toward the River Loire having already outpaced their supply train and a large part of their army. Essentially, having easily destroyed all resistance in that part of Gaul, the invading army had split off into several raiding parties, simply looting and destroying, while the main body advanced more slowly. A military explanation for why Eudes was defeated so easily at Bordeaux, after having won 11 years earlier at Battle of Toulouse, was simple. At Toulouse, Eudes managed a basic surprise attack against an overconfident and unprepared foe, all of whose defensive works were aimed inward, while he attacked from the outside. The Arab cavalary never got a chance to mobilize and meet him in open battle. At Bordeaux, they did, and resulted in absolute devastation of Eudes army, almost all of whom were killed, with minimal losses to the Muslims. Eudes forces, like other European troops of that era, lacked stirrups, and therefore had no armoured cavalry. Virtually all of their troops were infantry. The Muslim heavy cavalry broke the Christian infantry in their first charge, and then simply slaughtered them at will as they broke and ran. The invading force then went on to devastate southern Gaul, preparing it for complete conquest. One of the major raiding parties advanced on Tours. A possible motive, according to the second continuator of Fredegar, was the riches of the Abbey of Saint Martin of Tours, the most prestigious and holiest shrine in western Europe at the time. Upon hearing this, Austrasia Mayor of the Palace Charles Martel, collected his army of an estimated 15-75,000 veterans, and marched south avoiding the old Roman roads hoping to take the Muslims by surprise.

Despite the great importance of this battle, its exact location remains unknown. Most historians assume that the two armies met each other where the rivers Clain and Vienne join between Tours and Poitiers.

Charles chose to begin the battle in a defensive, phalanx-like formation. According to the Arabian sources they drew up in a large square. Certainly, given the disparity between the armies, in that the Franks were mostly infantry, all without armour, against mounted and Arab armored or mailed horsemen, (the Berbers were less heavily protected) Charles Martel fought a brilliant defensive battle. In a place and time of his choosing, he met a far superior force, and defeated it.

For six days, the two armies watched each other with just minor skirmishes. The Muslims waited for their full strength to arrive, which it did, but they were still uneasy. No good general, and Abd er Rahman was one, liked to let his opponent pick the ground and conditions for battle -- and Martel had done both. Creasy says, and his theory is probably best, that the Muslims best strategic choice would have been to simply decline battle, depart with their loot, garrisoning the captured towns in southern Gaul, and return when they could force Martel to a battleground more to their liking, one that maximized the huge advantage they had of the first true "knights" mailed and amoured horsemen -- the Franks, without stirrups in wide use, had to depend on unarmoured foot soldiers. Martel gambled everything that Abd er Rahman would in the end feel compelled to battle, and to go on and loot Tours. Neither of them wanted to attack. The Franks were well dressed for the cold, and had the terrain advantage. The Arabs were not as prepared for the intense cold, but did not want to attack what they thought might be a numerically superior Frankish army. (most historians believe it was not) Essentially, the Arabs wanted the Franks to come out in the open, while the Franks, formed in a tightly packed defensive formation, wanted them to come uphill, into the trees, (negating at once some of the advantages of their cavalry). It became a waiting game, which Martel won. The fight commenced on the seventh day, as Abd er Rahman did not want to postpone the battle indefinitely.

Abd er Rahman trusted the tactical superiority of his cavalry, and had them charge repeatedly. This time the faith the Muslims had in their cavalry, armed with their long lances and swords which had brought them victory in previous battles, was not justified.

In one of the rare instances where medieval infantry stood up against cavalry charges, the disciplined Frankish soldiers withstood the assaults, though according to Arab sources, the Arab cavalry several times broke into the interior of the Frankish square. But despite this, Franks did not break, and it is probably best expressed by a translation of an Arab account of the battle from the Medieval Source Book: "And in the shock of the battle the men of the North seemed like North a sea that cannot be moved. Firmly they stood, one close to another, forming as it were a bulwark of ice; and with great blows of their swords they hewed down the Arabs. Drawn up in a band around their chief, the people of the Austrasians carried all before them. Their tireless hands drove their swords down to the breasts of the foe."

It might have been different, however, had the Muslim forces remained under control. According to Muslim accounts of the battle, in the midst of the fighting on the second day, scouts from the Franks began to raid the camp and supply train (including slaves and other plunder). A large portion of the army broke off and raced back to their camp to save their plunder. What appeared to be a retreat soon became one. While attempting to restore order to his men, who had managed to break into the defensive square, Abd er Rahman was surrounded by Franks and killed.

According to a Frankish source, the battle lasted one day. Frankish histories claim that when the rumor went through the Arab army that Frankish cavalry threatened the booty they had taken from Bordeaux, (Charles supposedly had sent scouts to cause chaos in the Muslim base camp, and free as many of the slaves as possible, hoping to draw off part of his foe, it succeeded beyond his wildest dreams), many of the Muslim Cavalry returned to their camp. This, to the rest of the Muslim army, appeared to be a full-scale retreat, and soon it was one. Both histories agree that while attempting to stop the retreat, Abd er Rahman became surrounded, which led to his death, and the Muslims returned to their camp.

The next day, when the Muslims did not renew the battle, the Franks feared an ambush. Only after extensive reconnaissance by Frankish soldiers of the Muslim camp was it discovered that the Muslims had retreated during the night.

The Arab army retreated south over the Pyrenees. Charles earned his nickname Martel, meaning hammer, in this battle. He continued to drive the Muslims from France in subsequent years. After Eudes died, who had been forced to acknowledge, albeit reservedly, the suzerainty of Charles in 719, his son wished independence. Though Charles wished to unite the duchy directly to himself and went there to elicit the proper homage of the Aquitainians, the nobility proclaimed Odo's son, Hunold, whose dukedom Charles recognised when the Arabs invaded Provence the next year. Hunold, who originally resisted acknowledging Charles as overlord, had no choice when the Muslims returned.

In 736 the Caliphate launched another massive invasion -- this time by sea. This naval Arab invasion was headed by Abdul Rahman's son. It landed in Narbonne in 736 and took Arles. Charles, the conflict with Hunold put aside, descended on the Proven�al strongholds of the Muslims. In 736, he retook Montfrin and Avignon, and Arles and Aix-en-Provence with the help of Liutprand, King of the Lombards. N�mes, Agde, and B�ziers, held by Isalm since 725, fell to him and their fortresses destroyed. He smashed a Muslim force at the River Berre, and prepared to meet their primary invasion force at Narbonne. He defeated a mighty host outside of that city, using for the first time, heavy cavalry of his own, which he used in coordination with his planax. He crushed the Muslim army, though outnumbered, but failed to take the city. Provence, however, he successfully rid of its foreign occupiers.

Notable about these campaigns was Charles' incorporation, for the first time, of heavy cavalry with stirrups to augment his phalanx. His ability to coordinate infantry and cavalry veterans was unequaled in that era and enabled him to face superior numbers of invaders, and decisively defeat them again and again. Some historians believe Narbonne in particular was as imporant a victory for Christian Europe as Tours. Charles was that rarest of commonities in the dark ages: a brilliant stategic general, who also was a tactical commander par excellance, able in the crush and heat of battle to adapt his plans to his foes forces and movement -- and amazingly, defeated them repeatedly, especially when, as at Tours, they were far superior in men and weaponry, and at Berre and Narbonne, when they were superior in numbers of brave fighting men. Charles had the last quality which defines genuine greatness in a military commander: he foresaw the dangers of his foes, and prepared for them with care; he used ground, time, place, and fierce loyalty of his troops to offset his foes superior weaponry and tactics; third, he adapted, again and again, to the enemy on the battlefield, cooly shifting to compensate for the foreseen and unforeseeable.

The importance of these campaigns, Tours and the later campaigns of 736-7 in putting an end to Muslim bases in Gaul, and any immediate ability to expand Islamic influence in Europe, cannot be overstated. Gibbons and his generation of historians, and the majority of modern experts agree with them that they were unquestionably decisive in world history. Despite these victories, the Arabs remained in control of Narbonne and Septimania for another 27 years, but could not expand further than that. The treaties reached earlier with the local population stood firm and were further consolidated in 734 when the governor of Narbonne, Yusuf ibn 'Abd al-Rahman al-Fihri, concluded agreements with several towns on common defense arrangements against the encroachments of Charles Martel, who had systematically brought the south to heel as he extended his domains. He believed, and rightly so, that it was vital to keep the Muslims in Iberia, and not allow them a foothold in Gaul itself. Though he won the battle of Narbonne when the army there came out to meet him, Charles failed in his attempt to take Narbonne by siege in 737, when the city was jointly defended by its Muslim Arab and Christian Visigoth citizens. It was left to his son, Pippin the short, to force the city's surrender, in 759, and to drive the Arabs completely back to Iberia, and bring Narbonne into the Frankish Domains. His Grandson, Charlamagne, became the first Christian ruler to actually begin what would be called the Reconquista from Europe proper. In the east of the peninsula the Frankish emperors established the Marca Hispanica across the Pyrenees in part of what today is Catalonia, reconquering Girona in 785 and Barcelona in 801. This formed a buffer zone against Islam across the Pyrenees.

Tours in history

In Western history

Christian contemporaries, from Bede to Theophanes carefully recorded the battle and were keen to spell out what they saw as its implications. Later scholars, such as Edward Gibbon, would contend that had Martel fallen, the Moors would have easily conquered a divided Europe. Gibbon wrote that "A victorious line of march had been prolonged above a thousand miles from the rock of Gibraltar to the banks of the Loire; the repetition of an equal space would have carried the Saracens to the confines of Poland and the Highlands of Scotland; the Rhine is not more impassable than the Nile or Euphrates, and the Arabian fleet might have sailed without a naval combat into the mouth of the Thames. Perhaps the interpretation of the Qur'an would now be taught in the schools of Oxford, and her pulpits might demonstrate to a circumcised people the sanctity and truth of the revelation of Muhammed." Certainly, the Islamic invasions were an enormous danger during the window of 721 from Toulouse to 737 at the Arab defeat at Narbonne. But the window was closing. The unified Caliphate collapsed into civil war in 750 at the Battle of the Zab which left the Umayyad dynasty literally wiped out except for the Princes who escaped to Africa, and then Iberia, where they established the Umayyad Emirate in opposition to the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad.

Both ancient, mid, and modern historians agree that Martel was the father of western heavy cavalry, and literally stole the technoloy from his slain foe! He had no trouble using his enemies tools against them, no pride stopped him from seizing any advantage he could in defending his faith, his father's home and homeland, and his people, from what he saw was a danger that would destroy them if not checked. His foresight in moving to strike first, to stop them short of his "front door," reminds one of Winston Churchill's famous statement, that "it is better to fight in your neighbors back yard, than have to defend your own front door." In 5 short years, from the Battle of Tours, to the Battle of Narbonne, he fathered western heavy cavalry, and used it in conjunction with his planax with devastating effect.

In the modern era, Norwich, the most widely read authority on the Eastern Roman Empire, says the Franks halting Muslim Expansion at Tours literally preserved Christianity as we know it. A more realistic viewpoint may be found in Barbarians, Marauders, and Infidels by Antonio Santosuosso, Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Western Ontario, and considered an expert historian in the era in dispute in this article. It was published in 2004, and has quite an interesting modern expert opinion on Charles Martel, Tours, and the subsequent campaigns against Rahman's successor in 736-737. Santosuosso makes a compelling case that these defeats of invading Muslim Armies, were at least as important as Tours in their defense of western Christianity, and the preservation of those Christian monastaries and centers of learning which ultimately led Europe out of the dark ages. He also makes a compelling case that while Tours was unquestionably of macrohistorical importance, the later battles were at least equally so. Both invading forces defeated in those campaigns had come to set up permanent outposts for expansion, and there can be no doubt that these three defeats combined broke the back of European expansion by Islam while the Caliphate was still united. While some modern assessments of the battle's impact have backed away from the extreme of Gibbon's position, Gibbons's conjecture is supported by other historians such as Edward Shepard Creasy and William E. Watson. Most modern historians such as Norwich and Santosuosso generally support the concept of Tours as a macrohistorical event favoring western civilization and Christianity . Military writers such as Robert W. Martin, "The Battle of Tours is still felt today", also argue that Tours was such a turning point in favor of western civilization and Christianity that its aftereffect remains to this day.

In Arab history

Contemporary Arab historians and chroniclers are much more interested in the second Umayyad siege Arab defeat at Constantinople in 718, which ended in a disastrous defeat. After the first Arab siege of Constantinople (674-678) ended in complete failure, the Arabs Umayyad Caliphate attempted a second decisive attack on the city. An 80,000 strong army led by Maslama, the brother of Caliph Umar II, crossed the Bosporus from Anatolia to besiege Constantinople by land, while a massive fleet of Arab war galleys, estimated between 1,800 and 2,000, sailed into the Sea of Marmara to the south of the city. Fortunately for the Byzantines, the great chain kept the fleet from entering the inner harbor, and the Arab galleys were unable to sail up the Bosporus as they were under constant attack and harassment by the Greek fleet, who used Greek fire to level the differences in numbers. (The Byzantine fleet was less than a third of the Arab, but Greek fire swiftly evened the numbers). Emperor Leo III was able to use the famed Walls of Constantinople to his advantage and the Arab army was unable to breach them. (it must be noted that Bulgar forces had come to the aid of the Byzantines, and constantly harassed the Muslim army, and definitely disrupted resupply to the point that much of the army was close to starvation by the time the siege was abandoned. Some Muslim historians have argued that had the Caliph recalled his armies from Europe to aid in the siege, the city might have been taken by land, despite the legendary walls - such a recall would have doubled the army laying siege, allowed a full attack while still beating off Bulgar forces attempting to end the siege by harassing the army from outside while the defenders held the walls.

Some contemporary historians argue that had the Arabs actually wished to conquer Europe they could easily have done so. Essentially these historians argue that the Arabs were not interested enough to mount a major invasion, because Northern Europe at that time was considered to be a socially, culturally and economically backward area with little to interest any invaders. Some western scholars, such as Bernard Lewis, agree with this stance, though they are in a minority.

This is also disputed by Arab histories of the period circa 722-850 which mentioned the Franks more than any other Christian people save the Byzantines, (The Arabian chronicles were compiled and translated into Spanish by Jos� Antonio Conde, in his "Historia de la Dominaci�n de los �rabes en Espa�a", published at Madrid in 1820, and in dealing specifically with this period, the Arab chronicles discuss the Franks as one of two non-Muslim Powers then concerning the Caliphate). Further, this is disputed by the records of the Islamic raids into India and other non-Muslim states for loot and converts. Given the great wealth in Christian shrines such as the one at Tours, Islamic expansion into that area would have been likely had it not been sharply defeated in 732, 736, and 737 by Martel, and internal strife in the Islamic world prevented later efforts. Other relevant evidence of the importance of this battle lies in Islamic expansion into all other regions of the old Roman Empire -- except for Europe, and what was retained by Byzantium, the Caliphate took all of the old Roman and Persian Empires. It is not likely Gaul would have been spared save by the campaigns by, and the loyalty of, Charles Martel's veteran Frankish Army. Finally, it ignores that 4 separate Emirs of al-Andalus, over a 25 year period used a Fatwa from the Caliph to levy troops from all provinces of Africa, Syria, and even Turkomens who were beginning conversion, to raise 4 huge invading armies, well supplied and equipped, with the intention of permanent expansion across the Pyrenees into Europe. No such later attempts however were made as conflict between the Umayyad Emirate of Iberia and the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad prevented a unified assault on Europe.

Given the importance Arab histories of the time placed on the death of Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi Abd al Rahman and the defeat in Gaul, and the subsequent defeat and destruction of Muslim bases in what is now France, it seems reasonably certain that this battle did have macrohistorical importance in stopping westward Islamic expansion. Arab histories written during that period and for the next seven centuries make clear that Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi Abd al Rahman's defeat and death was regarded, and most scholars believe, as a catastrophe of major proportions. Their own words record it best: (translated from Arabic) "This deadly defeat of the Moslems, and the loss of the great leader and good cavalier, Abderrahman, took place in the hundred and fifteenth year." (Islamic Calendar) This, from the portion of the history of the Umayyad Caliphate, and the great Arab period of expansion, also translated into Spanish by Don Jose Antonio Conde, in his "Historia de la Dominacion de los Arabos en Espa�a," appears to put the importance of the Battle of Tours in macrohistorical perspective.

Contemporary analysis

Had Martel fallen at Tours the long term implications for European Christianity may have been devastating. His victory there, and in the following campaigns, may have literally saved Europe and Christianity as we know it, from conquest while the Caliphate was unified and able to mount such a conquest. Had the Franks fallen, no other power existed stopping Muslim conquest of Italy and the effective end of what would become the modern Catholic Church. In addition, Martel's incorporation of the stirrup and mailed cavalry into the Frankish army gave birth to the armoured Knights which would form the backbone of western armies for the next five centuries. But had Martel failed, there would have been no Charlemagne, no Holy Roman Empire or Papal States. The majority view argues that all these events occurred because Martel was able to contain Islam from expanding into Europe while it could. His son retook Narbonne, and his Grandson Charlamagne actually established the Marca Hispanica across the Pyrenees in part of what today is Catalonia, reconquering Girona in 785 and Barcelona in 801. This formed a permanent buffer zone against Islam, with Frankish strongholds in Iberia, which became the basis, along with the King of Asturias, named Pelayo (718-737, who started his fight against the Moors in the mountains of Covadonga 722) for the origins of the Reconquista until all of the Muslims were expelled from the Iberia.

No later Muslim attempts against Asturias or the Franks was made as conflict between what remained of the Umayyad Dynasty, (which was the Umayyad Emirate and then Caliphate of Iberia) and the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad prevented a unified assault on Europe. It would be another 700 years before the Ottomans managed to invade Europe via the Balkans.

Umayyad Caliphate Timeline

Cyprus, crete, and rhodes falls, establishment and early expansion, mu'awiya establishes the umayyad dynasty, arab conquest of north africa, first arab siege of constantinople, rapid expansion and consolidation, battle of karbala, second fitna, siege of mecca death of yazid, dome of the rock completed, battle of maskin, umayyad control over ifriqiya, armenia annexed, umayyad conquest of hispania, battle of guadalete, umayyad campaigns in india, transoxiana conquered, battle of aksu, second arab siege of constantinople, caliphate of umar ii, battle of tours, berber revolt against the umayyad caliphate, third fitna, abbasid revolution, decline and fall of the caliphate, end of the umayyad caliphate, banquet of blood, umayyad dynasty in al-andalus, abd al-rahman i establishes the emirate of cordoba.

Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad . The caliphate was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. Uthman ibn Affan (r. 644–656), the third of the Rashidun caliphs, was also a member of the clan. The family established dynastic, hereditary rule with Muawiya ibn Abi Sufyan, long-time governor of Greater Syria, who became the sixth caliph after the end of the First Fitna in 661. After Mu'awiyah's death in 680, conflicts over the succession resulted in the Second Fitna, and power eventually fell into the hands of Marwan I from another branch of the clan. Greater Syria remained the Umayyads' main power base thereafter, with Damascus serving as their capital. The Umayyads continued the Muslim conquests, incorporating the Transoxiana, Sindh, the Maghreb and the Iberian Peninsula (Al-Andalus) under Islamic rule. At its greatest extent, the Umayyad Caliphate covered 11,100,000 km2 (4,300,000 sq mi), making it one of the largest empires in history in terms of area. The dynasty in most of the Islamic world was eventually overthrown by a rebellion led by the Abbasids in 750.

During the pre-Islamic period, the Umayyads or "Banu Umayya" were a leading clan of the Quraysh tribe of Mecca. By the end of the 6th century, the Umayyads dominated the Quraysh's increasingly prosperous trade networks with Syria and developed economic and military alliances with the nomadic Arab tribes that controlled the northern and central Arabian desert expanses, affording the clan a degree of political power in the region. The Umayyads under the leadership of Abu Sufyan ibn Harb were the principal leaders of Meccan opposition to the Islamic prophet Muhammad , but after the latter captured Mecca in 630, Abu Sufyan and the Quraysh embraced Islam. To reconcile his influential Qurayshite tribesmen, Muhammad gave his former opponents, including Abu Sufyan, a stake in the new order. Abu Sufyan and the Umayyads relocated to Medina, Islam's political centre, to maintain their new-found political influence in the nascent Muslim community.

Muhammad's death in 632 left open the succession of leadership of the Muslim community. The Muhajirun gave allegiance to one of their own, the early, elderly companion of Muhammad, Abu Bakr, and put an end to Ansarite deliberations. Abu Bakr was viewed as acceptable by the Ansar and the Qurayshite elite and was acknowledged as caliph (leader of the Muslim community). He showed favor to the Umayyads by awarding them command roles in the Muslim conquest of Syria . One of the appointees was Yazid, the son of Abu Sufyan, who owned property and maintained trade networks in Syria.

Abu Bakr's successor Umar (r. 634–644) curtailed the influence of the Qurayshite elite in favor of Muhammad's earlier supporters in the administration and military, but nonetheless allowed the growing foothold of Abu Sufyan's sons in Syria, which was all but conquered by 638. When Umar's overall commander of the province Abu Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah died in 639, he appointed Yazid governor of Syria's Damascus, Palestine and Jordan districts. Yazid died shortly after and Umar appointed his brother Mu'awiya in his place. Umar's exceptional treatment of Abu Sufyan's sons may have stemmed from his respect for the family, their burgeoning alliance with the powerful Banu Kalb tribe as a counterbalance to the influential Himyarite settlers in Homs who viewed themselves as equals to the Quraysh in nobility or the lack of a suitable candidate at the time, particularly amid the plague of Amwas which had already killed Abu Ubayda and Yazid. Under Mu'awiya's stewardship, Syria remained domestically peaceful, organized and well-defended from its former Byzantine rulers.

During Umar's reign, the governor of Syria, Muawiyah I, sent a request to build a naval force to invade the islands of the Mediterranean Sea but Umar rejected the proposal because of the risk to the soldiers. Once Uthman became caliph, however, he approved Muawiyah's request. In 650, Muawiyah attacked Cyprus, conquering the capital, Constantia, after a brief siege, but signed a treaty with the local rulers. During this expedition, a relative of Muhammad , Umm-Haram, fell from her mule near the Salt Lake at Larnaca and was killed. She was buried in that same spot, which became a holy site for many local Muslims and Christians and, in 1816, the Hala Sultan Tekke was built there by the Ottomans. After apprehending a breach of the treaty, the Arabs re-invaded the island in 654 with five hundred ships. This time, however, a garrison of 12,000 men was left in Cyprus, bringing the island under Muslim influence. After leaving Cyprus, the Muslim fleet headed towards Crete and then Rhodes and conquered them without much resistance. From 652 to 654, the Muslims launched a naval campaign against Sicily and captured a large part of the island. Soon after this, Uthman was murdered, ending his expansionist policy, and the Muslims accordingly retreated from Sicily. In 655 Byzantine Emperor Constans II led a fleet in person to attack the Muslims at Phoinike (off Lycia) but it was defeated: both sides suffered heavy losses in the battle, and the emperor himself narrowly avoided death.

There is little information in the early Muslim sources about Mu'awiya's rule in Syria, the center of his caliphate. He established his court in Damascus and moved the caliphal treasury there from Kufa. He relied on his Syrian tribal soldiery, numbering about 100,000 men, increasing their pay at the expense of the Iraqi garrisons; also about 100,000 soldiers combined.

Mu'awiya is credited by the early Muslim sources for establishing diwans (government departments) for correspondences (rasa'il), chancellery (khatam) and the postal route (barid). According to al-Tabari, following an assassination attempt by the Kharijite al-Burak ibn Abd Allah on Mu'awiya while he was praying in the mosque of Damascus in 661, Mu'awiya established a caliphal haras (personal guard) and shurta (select troops) and the maqsura (reserved area) within mosques.

Although the Arabs had not advanced beyond Cyrenaica since the 640s other than periodic raids, the expeditions against Byzantine North Africa were renewed during Mu'awiya's reign.

In 665 or 666 Ibn Hudayj led an army which raided Byzacena (southern district of Byzantine Africa) and Gabes and temporarily captured Bizerte before withdrawing to Egypt . The following year Mu'awiya dispatched Fadala and Ruwayfi ibn Thabit to raid the commercially valuable island of Djerba.Meanwhile, in 662 or 667, Uqba ibn Nafi, a Qurayshite commander who had played a key role in the Arabs' capture of Cyrenaica in 641, reasserted Muslim influence in the Fezzan region, capturing the Zawila oasis and the Garamantes capital of Germa. He may have raided as far south as Kawar in modern-day Niger.

The first Arab siege of Constantinople in 674–678 was a major conflict of the Arab–Byzantine wars, and the first culmination of the Umayyad Caliphate's expansionist strategy towards the Byzantine Empire, led by Caliph Mu'awiya I. Mu'awiya, who had emerged in 661 as the ruler of the Muslim Arab empire following a civil war, renewed aggressive warfare against Byzantium after a lapse of some years and hoped to deliver a lethal blow by capturing the Byzantine capital, Constantinople. As reported by the Byzantine chronicler Theophanes the Confessor, the Arab attack was methodical: in 672–673 Arab fleets secured bases along the coasts of Asia Minor, and then proceeded to install a loose blockade around Constantinople. They used the peninsula of Cyzicus near the city as a base to spend the winter, and returned every spring to launch attacks against the city's fortifications. Finally, the Byzantines, under Emperor Constantine IV, managed to destroy the Arab navy using a new invention, the liquid incendiary substance known as Greek fire. The Byzantines also defeated the Arab land army in Asia Minor, forcing them to lift the siege.

The Byzantine victory was of major importance for the survival of the Byzantine state, as the Arab threat receded for a time. A peace treaty was signed soon after, and following the outbreak of another Muslim civil war, the Byzantines even experienced a period of ascendancy over the Caliphate.

The Battle of Karbala was fought on 10 October 680 CE between the army of the second Umayyad Caliph Yazid I and a small army led by Husayn ibn Ali, the grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad , at Karbala, modern day Iraq . Husayn was killed along with most of his relatives and companions, while his surviving family members were taken prisoner. The battle was followed by the Second Fitna, during which the Iraqis organized two separate campaigns to avenge the death of Husayn; the first one by the Tawwabin and the other one by Mukhtar al-Thaqafi and his supporters.

The Battle of Karbala galvanized the development of the pro-Alid party (Shi'at Ali) into a unique religious sect with its own rituals and collective memory. It has a central place in the Shi'a history, tradition, and theology, and has frequently been recounted in Shi'a literature.

The Second Fitna was a period of general political and military disorder and civil war in the Islamic community during the early Umayyad Caliphate. It followed the death of the first Umayyad caliph Mu'awiya I in 680 and lasted for about twelve years. The war involved the suppression of two challenges to the Umayyad dynasty, the first by Husayn ibn Ali, as well as his supporters including Sulayman ibn Surad and Mukhtar al-Thaqafi who rallied for his revenge in Iraq , and the second by Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr.