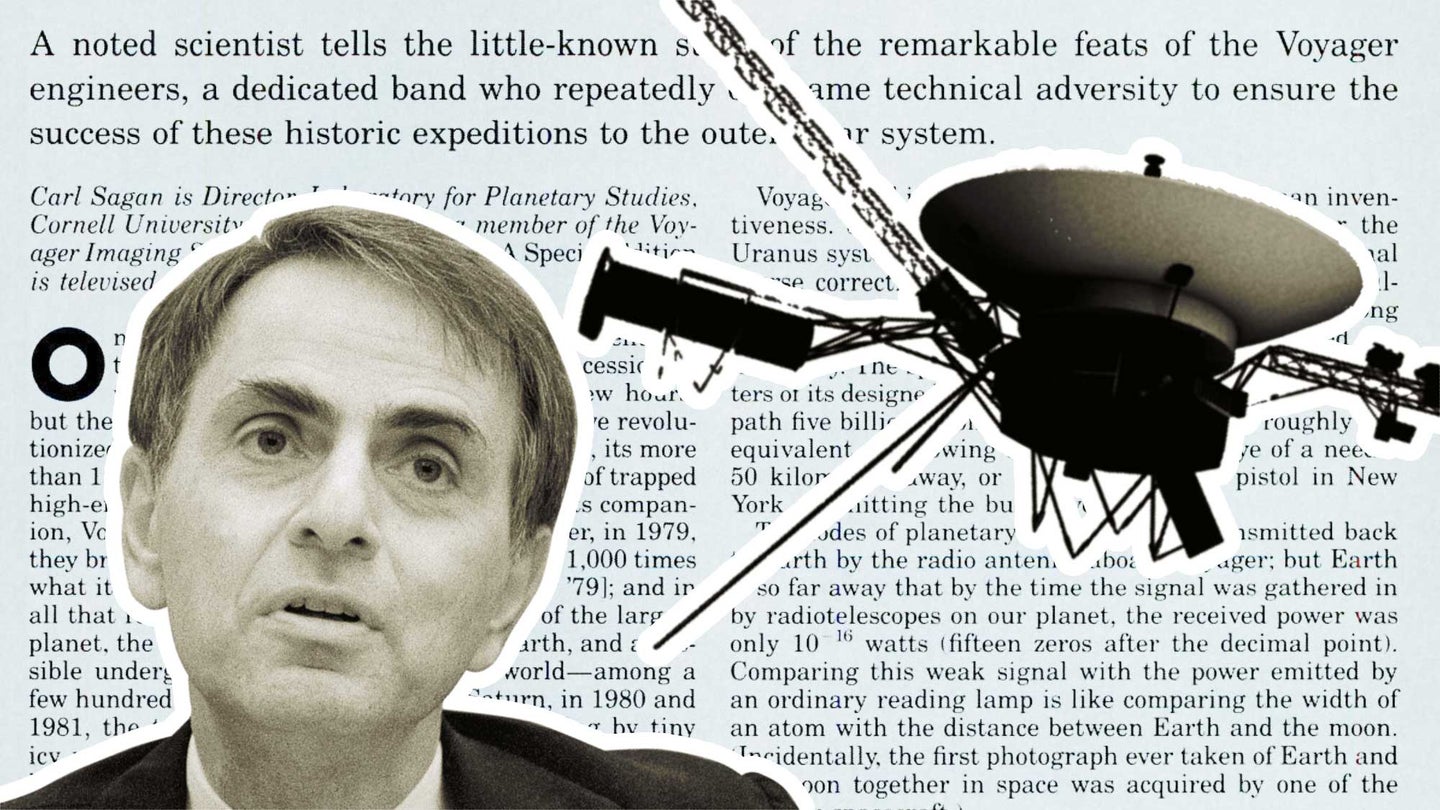

Carl Sagan in 1986: ‘Voyager has become a new kind of intelligent being—part robot, part human’

The renowned scientist reflected on the lesser-known triumphs and lofty ambitions of Voyager in Popular Science's October 1986 issue.

By Bill Gourgey | Published Mar 25, 2024 9:02 AM EDT

One of the worries that kept legendary astronomer Carl Sagan up at night was whether aliens would understand us. In the mid-1970s, Sagan led a committee formed by NASA to assemble a collection of images, recorded greetings, and music to represent Earth. The montage was pressed onto golden albums and dispatched across the cosmos on the backs of Voyagers 1 and 2 .

In a 1986 story Sagan wrote for Popular Science , he noted that “hypothetical aliens are bound to be very different from us—independently evolved on another world,” which meant they likely wouldn’t be able to decipher the golden discs. But he took assurance from an underappreciated dimension of Voyagers’ message: the designs of the vessels themselves.

“We are tool makers,” Sagan wrote. “This is a fundamental aspect, and perhaps the essence, of being human.” What better way to tell alien civilizations that Earthlings are toolmakers than by sending a living room-sized, aluminum-framed probe clear across the Milky Way.

Although both spacecraft were only designed to swing by Jupiter and Saturn , Voyager 2’s trajectory also hurled it past Uranus and Neptune . Despite numerous mishaps along the way—and because of the elite toolmaker skills of NASA engineers—the probe was in good enough shape to send back close-ups of those distant worlds. In 2012, Voyager 1 became the first interstellar spacecraft , followed soon thereafter by Voyager 2 . “Once out of the solar system,” Sagan wrote, “the surfaces of the spacecraft will remain intact for a billion years or more,” so resilient is their design.

Today, the probes are 12–15 billion miles from Earth , still operable (despite experiencing recent communication difficulties ), and sailing through the relative calm of interstellar space. They are expected to continue to transmit data back to Earth for another year or so , or until their plutonium batteries quit.

It was early 20th century wireless inventor Guglielmo Marconi who suggested that radio signals never die, they only diminish as they travel across space and time. Even after communications from the Voyager spacecraft cease, perhaps the tiny voices of Earth’s first emissaries, animated by NASA’s master toolmakers nearly half a century ago, will continue to drift through the cosmos for all time, accessible to far-flung civilizations equipped with sensitive enough receivers to listen.

“Voyager’s Triumph” (Carl Sagan, October 1986)

A noted scientist tells the little-known story of the remarkable feats of the Voyager engineers, a dedicated band who repeatedly overcame technical adversity to ensure the success of these historic expeditions to the outer solar system.

Carl Sagan is Director, Laboratory for Planetary Studies, Cornell University, and, since 1970, a member of the Voyager Imaging Science Team. His Cosmos: A Special Edition is televised this fall.

On Jan. 25, 1986, the Voyager 2 robot probe entered the Uranus system and reported a procession of wonders. The encounter lasted only a few hours, but the data faithfully relayed back to Earth have revolutionized our knowledge of the aquamarine planet, its more than 15 moons, its pitch black rings, and its belt of trapped high-energy charged particles. Voyager 2 and its companion, Voyager 1, have done this before. At Jupiter, in 1979, they braved a dose of trapped charged particles 1,000 times what it takes to kill a human being [PS, July ’79); and in all that radiation they discovered the rings of the largest planet, the first active volcanoes outside Earth, and a possible underground ocean on an airless world—among a few hundred other major findings. At Saturn, in 1980 and 1981, the two spacecraft survived a pummeling by tiny icy particles as they plummeted through previously un known rings; and there they discovered not a few, but thou sands of Saturnian rings, icy moons recently melted through unknown causes, and a large world with an ocean of liquid hydrocarbons surmounted by clouds of organic matter IPS, March ’81 l. These spacecraft have returned to Earth four trillion bits of information, the equivalent of about 100,000 encyclopedia volumes.

Because we are stuck on Earth, we are forced to peer at distant worlds through an ocean of distorting air. It is easy to see why our spacecraft have revolutionized the study of the solar system: We ascend to the stark clarity of the vacuum of space, and there approach our objectives, flying past them or orbiting them or landing on their surfaces. These nearby worlds have much to teach us about our own, and they will be—unless we are so foolish as to destroy ourselves—as familiar to our descendents as the neighboring states are to those who live in America today.

Voyager and its brethren are prodigies of human inventiveness. Just before Voyager 2 was to encounter the Uranus system, the mission design had scheduled a final course correction, a short firing of the on-board propulsion system to position Voyager correctly as it flew among the moving moons. But the course correction proved unnecessary. The spacecraft was already within 200 kilometers of its designed trajectory after a voyage along an arcing path five billion kilometers in length. This is roughly the equivalent of throwing a pin through the eye of a needle 50 kilometers away, or firing your target pistol in New York and hitting the bull’s eye in Dallas.

The lodes of planetary treasure were transmitted back to Earth by the radio antenna aboard Voyager; but Earth is so far away that by the time the signal was gathered in by radiotelescopes on our planet, the received power was only 10-16 watts (fifteen zeros after the decimal point). Comparing this weak signal with the power emitted by an ordinary reading lamp is like comparing the width of an atom with the distance between Earth and the moon. (Incidentally, the first photograph ever taken of Earth and the moon together in space was acquired by one of the Voyager spacecraft.)

We tend to hear much about the splendors returned, and very little about the ships that brought them, or the shipwrights. It has always been that way. Our history books do not tell us much about the builders of the Nina, Pinta, and Santa Maria, or even the principle of the caravel. Despite ample precedent, it is a clear injustice: The Voyager engineering team and its accomplishments deserve to be much more widely known.

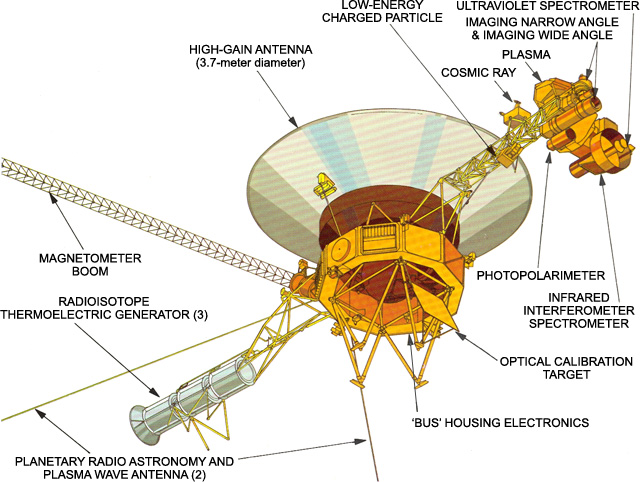

The Voyager spacecraft were designed and assembled, and are operated by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration in Pasadena, Calif. The mission was conceived during the late 1960s, first funded in 1972, but was not approved in its present form (which includes encounters at Uranus and Neptune) until after the 1979 Jupiter flyby. The two spacecraft were launched in late summer and early fall 1977 by a non-reusable Titan/Centaur booster configuration at Cape Canaveral, Fla. Weighing about a ton, a Voyager would fill a good-sized living room. Each spacecraft draws about 400 watts of power—considerably less than an average American home—from a generator that converts radioactive plutonium into electricity. The instrument that measures interplanetary magnetic fields is so sensitive that the flow of electricity through the innards of the spacecraft would generate spurious signals. As a result, this instrument is placed at the end of a long boom stretching out from the spacecraft. With other projections, it gives Voyager a slightly porcupine appearance. Two cameras, infrared and ultraviolet spectrometers, and an instrument called the photopolarimeter are on a scan platform; the platform swivels so these instruments can point toward a target world. The spacecraft antenna must know where Earth is if the transmitted data are to be received back home. The spacecraft also needs to know where the sun is and at least one bright star, so it can orient itself in three dimensions and point properly toward any passing world. It does no good to be able to return pictures over billions of miles if you can’t point the camera.

On-orbit repairs

Each spacecraft costs about as much as a single modern strategic bomber. But unlike bombers, Voyager cannot, once launched, be returned to the hangar for repairs.

As a result, the spacecraft’s computers and electronics are designed redundantly. And when Voyager finds itself in trouble, the computers use branched contingency tree logic to work out the appropriate course of action. As the spacecraft journeys increasingly far from Earth, the round-trip light (and radio) travel time also increases, approaching six hours by the time Voyager is at the distance of Uranus.

Thus, in case of an emergency, the spacecraft needs to know how to put itself in a safe standby mode while awaiting instructions from Earth. As the spacecraft ages, more and more failures are expected, both in its mechanical parts and its computer system, although there is as yet no sign of a serious memory deterioration, some robot Alzheimer’s disease. When an unexpected failure occurs, special teams of engineers—some of whom have been with the Voyager program since its inception—are assigned to “work” the problem. They will study the underlying basic science and draw upon their previous experience with the failed subsystems. They may do experiments with identical Voyager spacecraft equipment that was never launched or even manufacture a large number of components of the sort that failed in order to gain some statistical understanding of the failure mode.

In April 1978, almost eight months after launch, an omitted ground command caused Voyager 2’s on-board computer to switch from the prime radio receiver to its backup.

During the next ground transmission to the spacecraft, the receiver refused to lock onto the signal from Earth. A component called a tracking loop capacitor had failed. After seven days in which Voyager 2 was out of contact, its fault protection software commanded the backup receiver to be switched off and the prime receiver to be switched back on. But, mysteriously, the prime receiver failed moments later: It never recovered. Voyager 2 was now fundamentally imperiled. Although the primary receiver had failed, the on-board computer commanded the spacecraft to use it. There was no way for the controllers on Earth to command Voyager to revert to the backup receiver. Even worse, the backup receiver would be unable to receive the commands from Earth because of the failed capacitor. Finally, after a week of command silence, the computer was programmed to switch automatically between receivers.

And during that week’s time the JPL engineers designed an innovative command frequency control procedure to make a few essential commands comprehensible to the damaged backup receiver.

This meant the engineers were able to communicate, at least a little bit, with the spacecraft. Unfortunately the backup receiver now turned giddy, becoming extremely sensitive to the stray heat dumped when various components of the spacecraft were powered up or down. Over the following months the JPL engineers designed and conducted a series of tests that let them thoroughly understand the thermal consequences of most operational modes of the spacecraft on its ability to receive commands from Earth. The backup-receiver problem was entirely circumvented. It was this backup receiver that acquired all the commands from Earth on how to gather data in the Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus systems. The engineers had saved the mission. (But to be on the safe side, during most of Voyager’s subsequent flight there is in residence in the onboard computers a nominal data-taking sequence for the next planet to be encountered.)

Another heart-wrenching failure occurred just after Voyager 2 emerged from behind Saturn after its closest approach to the planet in August 1981. The scan platform had been moving rapidly in the azimuth direction—quickly pointing here and there among the rings, moons, and the planet itself during the time of closest approach. Suddenly, the platform jammed. A stuck scan platform obviously implies a severe reduction in future pictures and other key data. The scan platform is driven by gear trains called actuators, so first the JPL engineers ran an identical copy of the flight actuator in a simulated mission. The ground actuator failed after 348 revolutions: the actuator on the spacecraft had failed after 352 revolutions. The problem turned out to be a lubrication failure. Plainly, it would be impossible to overtake Voyager with an oil can. The engineers wondered whether it would be possible to restart the failed actuator by alternately heating and cooling it, so that the thermal stresses would cause the components of the actuator to expand and contract at different rates and un-jam the system. After gaining experience with specially manufactured actuators on the ground, the engineers jubilantly found that they were able to use this procedure to start the scan platform up again in space. More than this, they devised techniques to diagnose any imminent actuator failure early enough to work around the problem. Voyager 2’s scan platform worked perfectly in the Uranus system. The engineers had saved the day again.

Ingenious solutions

Voyager 1 and 2 were designed to explore the Jupiter and Saturn systems only. It is true that their trajectories would carry them to Uranus and Neptune, but officially these planets were never contemplated as targets for Voyager exploration: The spacecraft was not supposed to last that long. Because of trajectory requirements in the Saturn system, Voyager 1 was flung on a path that will never encounter any other known world; but Voyager 2 flew to Uranus with brilliant success, and is now on its way to an August 1989 encounter with the Neptune system.

At these immense distances, sunlight is getting progressively dimmer, and the spacecraft’s transmitted radio signals to Earth are getting progressively fainter. These were predictable but still very serious problems that the JPL engineers and scientists also had to solve before the encounter with Uranus.

Because of the low light levels at Uranus, the Voyager television cameras were obliged to take longer time exposures. But the spacecraft was hurtling through the Uranus system so fast (about 35,000 miles per hour) that the image would have been smeared or blurred—an experience shared by many amateur photographers. To overcome this, the entire spacecraft had to be moved during the time exposures to compensate for the motion, like panning in the direction opposite yours while taking a photograph of a street scene from a moving car. This may sound easier than it is: You have to compensate for the most casual of motions. At zero gravity, the mere start and stop of the on-board tape recorder that’s registering the image can jiggle the spacecraft enough to smear the picture. This problem was solved by commanding the spacecraft thrusters, instruments of exquisite sensitivity, to compensate for the tape-recorder jiggle at the start and stop of each sequence by turning the entire spacecraft just a little. To compensate for the low received radio power at Earth, a new and more efficient digital encoding algorithm was designed for the cameras, and the radiotelescopes on Earth were joined together with oth ers to increase their sensitivity. Overall, the imaging system worked, by many criteria, better at Uranus than it did at Saturn or even at Jupiter.

Voyager has become a new kind of intelligent being—part robot, part human. It extends the human senses to far-off worlds.

The ingenuity of the JPL engineers is growing faster than the spacecraft is deteriorating. And Voyager may not be done exploring after its Neptune encounter.

There is, of course, a chance that some vital subsystem will fail tomorrow, but in terms of the radioactive decay of the plutonium power source, the two Voyager spacecraft will be able to return data to Earth until roughly the year 2015. By then they will have traveled more than a hundred times Earth’s distance from the sun, and may have penetrated the heliopause, the place where the interplanetary magnetic field and charged particles are replaced by their interstellar counterparts; the heliopause is one definition of the frontier of the solar system.

Robot-human partnerships

These engineers are heroes of our time. And yet almost no one knows their names. I have attached a table giving the names of a few of the JPL engineers who played central roles in the success of the Voyager missions.

In a society truly concerned for its future, Don Gray, Charlie Kohlhase, or Howard Marderness, would be as well known for their extraordinary abilities and accomplishments as Dwight Gooden, Wayne Gretzky, or Kareem Abdul Jabbar are for theirs.

Voyager has become a new kind of intelligent being-part robot, part human. It extends the human senses to far-off worlds. For simple tasks and short-term problems, it relies on its own intelligence; but for more complex tasks and longer term problems, it turns to another, considerably larger brain—the collective intelligence and experience of the JPL engineers. This trend is sure to grow. The Voyagers embody the technology of the early 1970s; if such spacecraft were to be designed in the near future, they would incorporate stunning improvements in artificial intelligence, in data-processing speed, in the ability to self-diagnose and repair, and in the capacity for the spacecraft to learn from experience. In the many environments too dangerous for people, the future belongs to robot-human partnerships that will recognize Voyager as antecedent and pioneer.

Unlike what seems to be the norm in the so-called defense industry, the Voyager spacecraft came in at cost, on time, and vastly exceeding both their design specifications and the fondest dreams of their builders. These machines do not seek to control, threaten, wound, or destroy; they represent the exploratory part of our nature, set free to roam the solar system and beyond.

Once out of the solar system, the surfaces of the spacecraft will main intact for a billion years or more, as the Voyagers circumnavigate the center of the Milky Way galaxy.

This kind of technology, its findings freely revealed to all humans everywhere, is one of the few activities of the United States admired as much by those who find our policies uncongenial as by those who agree with us on every issue. Unfortunately, the tragedy of the space shuttle Challenger implies agonizing delays in the launch of Voyager’s successor missions, such as the Galileo Jupiter orbiter and entry probe. Without real support from Congress and the White House, and a clear long-term NASA goal, NASA scientists and engineers will be forced to find other work, and the historic American triumphs in solar-system exploration—symbolized by Voyager—will become a thing of the past. Missions to the planets are one of those things—and I mean this for the entire human species—that we do best. We are tool makers—this is a fundamental aspect, and perhaps the essence, of being human.

Greeting the aliens

Both Voyager spacecraft are on escape trajectories from the solar system. The gravitational fields of Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus have flung them at such high velocities that they are destined ultimately to leave the solar system altogether and wander for ages in the calm, cold blackness of interstellar space—where, it turns out, there is essentially no erosion.

Once out of the solar system, the surfaces of the spacecraft will main intact for a billion years or more, as the Voyagers circumnavigate the center of the Milky Way galaxy. We do not know whether there are other space-faring civilizations in the Milky Way. And if they do exist, we do not know how abundant they are.

But there is at least a chance that some time in the remote future one of the Voyagers will be intercepted by an alien craft. Voyagers 1 and 2 are the fastest spacecraft ever launched by humans; but even so, they are traveling so slowly that it will be tens of thousands of years before they go the distance to the nearest star. And they are not headed toward any of the nearby stars. As a result there could be no danger of Voyager attracting “hostile” aliens to Earth, at least not any time soon.

So, it seemed appropriate to include some message of greeting from Earth At NASA’s request, a committee I chaired designed a phonograph record that was affixed to the outside of each of the Voyager spacecraft. The records contain 116 pictures in digital form, describing our science and technology, our institutions, and ourselves; what will surely be unintelligible greetings in many languages; a sound essay on the evolution of our planet; and an hour and a half of the world’s greatest music. But the hypothetical aliens are bound to be very different from us—independently evolved on another world. Are we really sure they could understand our message? Every time I feel these concerns stirring, though, I reassure myself: Whatever the incomprehensibilities of the Voyager record, any extraterrestrial that finds it will have another standard by which to judge us.

Each Voyager is itself a message. In its exploratory intent, in the lofty ambition of its objectives, and in the brilliance of its design and performance, it speaks eloquently for us.

Bill Gourgey is a Popular Science contributor and unofficial digital archeologist who enjoys excavating PopSci’s vast archives to update noteworthy stories (yes, merry-go-rounds are noteworthy).

Like science, tech, and DIY projects?

Sign up to receive Popular Science's emails and get the highlights.

- Programs ’24

Psychiatry Films from AMHF: “Now, Voyager” (1942)

by Evander Lomke on February 19, 2012 6:23 pm

Thoughtful, caring: The ultimate analyst as shaman

Now, Voyager is the second “psychiatry film” in this series of blogs on movies with themes or characters that are relevant to the mission of AMHF. Released almost seventy years ago (October 22, 1942), Now, Voyager, which gets its title from lines in a poem by Walt Whitman (“The Untold Want”) , was something of a milestone in the career of Bette Davis . More to the point, though thought of as a weepie, the movie has important things to say about the power of psychoanalysis in the character of Dr. Jaquith, commandingly portrayed by Claude Rains .

The relatively complex plot, from Wikipedia, follows.

Charlotte Vale (Bette Davis) is an unattractive, overweight, repressed spinster whose life is dominated by her dictatorial mother (Gladys Cooper), an aristocratic Boston dowager whose verbal and emotional abuse of her daughter has contributed to the woman’s complete lack of self-confidence. Fearing Charlotte is on the verge of a nervous breakdown, her sister-in-law Lisa (Ilka Chase) introduces her to psychiatrist Dr. Jaquith (Claude Rains), who recommends she spend time in his sanatorium.

Away from her mother’s control, Charlotte blossoms. The transformed woman, at Lisa’s urging, opts to take a lengthy cruise rather than immediately return home. On board ship, she meets a married man, Jeremiah Duvaux Durrance ( Paul Henreid ), who is traveling with his friends Deb (Lee Patrick) and Frank McIntyre (James Rennie). It is from them that Charlotte learns of Jerry’s devotion to his young daughter, Christine (“Tina”), and how it keeps him from divorcing his wife, a manipulative, jealous woman who keeps Jerry from engaging in his chosen career of architecture, despite the fulfillment he gets from it.

Charlotte and Jerry become friendly, and in Rio de Janeiro the two are stranded on Sugarloaf Mountain when their car crashes. They miss the ship and spend five days together before Charlotte flies to Buenos Aires to rejoin the cruise. Although they have fallen in love, they decide it would be best not to see each other again.

When she arrives home, Charlotte’s family is stunned by the dramatic changes in her appearance and demeanor. Her mother is determined to regain control over her daughter, but Charlotte is resolved to remain independent. The memory of Jerry’s love and devotion help to give her the strength she needs to remain resolute.

Charlotte becomes engaged to wealthy, well-connected widower Elliot Livingston (John Loder), but after a chance meeting with Jerry, she breaks off the engagement, about which she quarrels with her mother. Her mother becomes so angry that she has a heart attack and dies. Guilty and distraught, Charlotte returns to the sanatorium.

When she arrives, she is immediately diverted from her own problems when she meets lonely, unhappy Tina, who greatly reminds her of herself; both were unwanted and unloved by their mothers. She is shaken out of her depression and instead becomes interested in Tina’s welfare. With Dr. Jaquith’s permission she takes the girl under her wing. When she improves, Charlotte takes her home to Boston.

Jerry and Dr. Jaquith visit the Vale home, where Jerry is delighted to see the changes in his daughter. While he initially pities Charlotte, believing her to be settling in her life, he’s taken aback by her acid contempt for his initial condescension. Dr. Jaquith has agreed to allow Charlotte to keep Tina there with the understanding that her relationship with Jerry will remain platonic. She tells Jerry that she sees Tina as his gift to her and her way of being close to him. When Jerry asks her if she’s happy, Charlotte finds much to value in her life and if it isn’t everything she would want, tells him, “Oh, Jerry, don’t let’s ask for the moon. We have the stars,” a line ranked number 46 in the American Film Institute’s list of the top 100 movie quotes in American cinema.

There is so much going on in this film, it is impossible to reduce the plot to “the beneficial effects of psychoanalysis on a seriously repressed personality.” The relationship between Charlotte and her domineering mother takes center stage, and is reflected in a subplot involving Charlotte and the young Tina. Jerry remains a bit of a cad from one point of view; yet, his influence on Charlotte is positive. She is out of her shell when they chance to meet. But it is Jerry who informs the rest of Charlotte’s life.

We see little of the actual methodology of Dr. Jaquith. In many ways, like the Marlon Brando character in Don Juan DeMarco , Claude Rains’s doctor-portrayal is almost as unrealistically indulgent and thoughtful on a single patient: Dr. Jaquith is an idealized psychiatrist, a magician of sorts.

As a study of the transforming power of analysis, the film is a little less believable in the first part, since (unlike Don Juan DeMarco), the viewer is privy to little of the psychiatrist’s methodology. Charlotte essentially blooms offscreen. Later, however, Charlotte’s ability to take Tina under her wing and provide her with the emotional backbone and stability that she (Charlotte) had lacked in the relationship with her own (eventually, and thankfully, deceased) mother—the Gladys Cooper character—show the possibilities of soulful growth thanks to, but clearly beyond, Dr. Jaquith’s techniques (whatever they were) and influence.

Overall, Now, Voyager remains one of the most astonishingly inspired and inspiring films ever made on the hope-filled, positive effects of psychiatry.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Psychoanalysis

Updates via Email

- Adolescence

- Alcohol and Substance Abuse

- Alexandra Styron

- Annual Reports

- Astor Services

- attachment theory

- Bipolar Disorder

- borderline personality

- Erich Fromm

- Featured Front Page

- Group Psychotherapy

- Individuals with Special Needs

- Mental Health Training

- Pearson Assessments

- Play Therapy

- Psychological Testing

- Psychopharmacology

- Psychotherapy

- Public Policy

- Religion and Mental Health

- Religion and Mental Health: The Varieties of Religious Experience by William James

- Schizophrenia

- Seizure Disorders and Epilepsy

- Special Needs

- Stefan de Shill

- Substance Abuse

- Suicide Prevention Initiatives

- Suicide Prevention International

- The Elderly

- Uncategorized

- William Styron

- Youth Violence

Box 3 Riverdale NY 10471-0003

- Tax Information

© 2024 American Mental Health Foundation

Subscribe or renew today

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

Voyager’s view.

Spacecraft’s journey to interstellar space helps put the solar system in perspective

Nicolle Rager Fuller

Share this:

By Andrew Grant

October 4, 2013 at 4:47 pm

It’s finally official: Voyager 1 has become the first human-made object to enter interstellar space, mission scientists report September 12 in Science . On August 25, 2012, the scientists say, Voyager 1 exited a giant invisible bubble called the heliosphere that is inflated by a torrent of subatomic particles spewing from the sun. Now the probe is surrounded almost exclusively by particles produced by other stars. But whether it’s correct to say that the probe has left the solar system depends on how you define the solar system. “From my perspective, Voyager is nowhere near the edge of the solar system,” says planetary scientist Hal Levison of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo. The sun continues to exert gravitational dominance out to hundreds of times the distance of Voyager 1 from the sun, where trillions of icy pebbles, boulders and comets orbit. In the last 36 years, Voyager has traveled an impressive 25.4 billion kilometers, but it still has a long way to go to unambiguously depart the solar system.

Distance from the sun: 5,000–100,000 AU The sun, planets and Voyager probes sit inside the tiny yellow dot at right, within a giant sphere called the Oort cloud. This reservoir of trillions of ice chunks extends 100,000 astronomical units out, tethered to the sun by gravity. Astronomers believe these objects got thrown out of the inner solar system as the planets took shape 4.5 billion years ago. Occasionally these castaways pass near Earth: The comet ISON, which may light up the night sky this November, started out in the Oort cloud. The Voyagers would have to travel another 30,000 years before clearing this broadest definition of the solar system.

Current distance from the sun: 126 AU 1 astronomical unit = 150 million kilometers (Earth-sun distance) Voyager 1 is now surrounded by a relatively thick fog of subatomic particles produced in the far reaches of the galaxy. Some particles originated in supernova explosions; others got blasted out of black holes. By 2016 astronomers expect the probe’s sibling spacecraft to pop through the solar bubble. Unlike Voyager 1, Voyager 2 carries a working instrument to measure the temperature and density of the interstellar medium. Both probes have enough plutonium power to communicate with Earth until about 2025.

Distance from the sun: about 122 AU Until recently, Voyager 1 was traveling within the heliosphere, bathed in a thin mist of particles from the solar wind. Voyager 1 passed through the boundary between the heliosphere and interstellar space, called the heliopause, last August. But the border crossing was not cut-and-dried: Astronomers expected the magnetic field to change direction in interstellar space along with the particle population, yet the field has barely budged. Theorists are struggling to understand why.

TERMINATION SHOCK

Distance from the sun: about 90 AU The solar wind gradually slows as it cruises past the planets. About 13 billion kilometers from where that wind originates, it slows down to about 350,000 kilometers per hour and generates a shock wave analogous to the one produced when a jet crosses the sound barrier. Voyager 1 reached this shock wave, known as the termination shock, in 2004. Beyond it, the solar wind wanes as the gateway to interstellar space approaches.

The sun unleashes a continuous stream of subatomic particles at more than 1.5 million kilometers per hour. This solar wind permeates a radius of billions of kilometers in all directions and inflates the heliosphere. For some astrophysicists, the solar system is defined by the presence of the solar wind.

KUIPER BELT

Distance from the sun: 30–100 AU For much of the past quarter century, Voyager 1 has been traversing this disk of icy objects (including Pluto) that were not incorporated into planets when the solar system formed.

The sun, planets and entire heliosphere orbit the center of the galaxy at a brisk 83,000 kilometers per hour. In July NASA’s Interstellar Boundary Explorer satellite discovered that the sun drags behind it a cometlike tail of subatomic particles (not shown) that may stretch 10 times as far from the sun as Voyager 1’s current position. The finding shows that the solar bubble is shaped more like an elongated bullet than a sphere. Fortunately Voyager 1 trekked toward the leading edge of the bubble, where the distance to interstellar space is comparatively short.

THE PLANETS

Neptune’s distance from sun: 30 AU The notion of the solar system as the sun plus eight planets (or nine, depending on your age) largely gets abandoned after grade school. Voyager 1 passed Neptune’s orbit in May 1987 and has since logged 14.2 billion kilometers.

More Stories from Science News on Astronomy

How a sugar acid crucial for life could have formed in interstellar clouds

How a 19th century astronomer can help you watch the total solar eclipse

A new image reveals magnetic fields around our galaxy’s central black hole

Did the James Webb telescope ‘break the universe’? Maybe not

JWST spies hints of a neutron star left behind by supernova 1987A

How to build an internet on Mars

Astronomers have snapped a new photo of the black hole in galaxy M87

Astronomers are puzzled over an enigmatic companion to a pulsar

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

- Voyeuristic Disorder

Table of Contents

Voyeuristic disorder is a condition wherein a person displays an extreme sexual interest in watching other people in their intimate moments such as during undressing, intercourse, or any other private action.

What Is Voyeuristic Disorder?

Voyeuristic disorder is a paraphilic disorder 1 Fisher KA, Marwaha R. Paraphilia. [Updated 2022 Mar 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554425/ , characterized by intense sexual gratification in watching or observing other people engage in sexual intercourse, undressing, or any other form of intimacy without their consent.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) defines 2 McManus, M. A., Hargreaves, P., Rainbow, L., & Alison, L. J. (2013). Paraphilias: definition, diagnosis and treatment. F1000prime reports, 5, 36. https://doi.org/10.12703/P5-36 this disorder as “urges to observe an unsuspecting person who is naked, undressing or engaging in sexual activities or in activities deemed to be of private nature.” It usually begins in adolescence or early adulthood.

The term comes from the French word “voir” meaning “to see” . Experts believe that this behavior is illegal, immoral, and undesirable and it causes distress to someone else.

However, it is neither a disorder nor an expression of an underlying mental disorder—unless a person becomes too consumed and distressed by voyeuristic thoughts and cannot function or act normally because of his/her fantasies. According to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), it is described as a “disorder of sexual preference.”

For diagnosing voyeuristic disorder, its symptoms must persist over a period of six months and the individual concerned must be over the age of 18 years. The diagnostic criteria laid down by the DSM-5 can be applied to individuals who accept or deny their paraphilic interests. But, the diagnosis 3 McManus, M. A., Hargreaves, P., Rainbow, L., & Alison, L. J. (2013). Paraphilias: definition, diagnosis and treatment. F1000prime reports, 5, 36. https://doi.org/10.12703/P5-36 of voyeuristic disorder becomes easier when the sufferers disclose their condition and report their emotional, social, or psychological impairment at the earliest.

Read More About DSM 5 Here

Understanding Voyeuristic Disorder

People suffering from the condition find sexual pleasure in observing or watching someone in an intimate moment, such as when they are naked, undressed, or engaged in sexual activities. They often go unnoticed since the receiving party is unaware that they are being observed.

The individual with this disorder experiences intense sexual gratification by observing unsuspecting and vulnerable people during their private affairs. It is worth mentioning that not everyone who has voyeuristic tendencies has a voyeuristic disorder.

This condition becomes a disorder when the urges and fantasies cause significant distress or hindrance in different areas of functioning. In such cases, it is important to learn about this condition, recognize when it becomes a problem, and understand how to overcome it responsibly without violating people’s privacy.

If you are on the receiving end of someone watching you, do not hesitate to call the police. It is not advisable to entertain the person who is ‘engaging’ with you without your consent. This behavior is also considered a criminal offense and if caught, the individual can face a prison sentence or a hefty fine.

Studies 4 Fedoroff, J. P. (2019). Voyeuristic disorder. The Paraphilias, 209-216. https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780190466329.003.0009 find voyeuristic disorder is prevalent in 12% of males and 4% of females across the globe.

Voyeurism Vs. Voyeuristic Disorder

Voyeurism 5 Smith, R.S. Voyeurism: A review of literature. Arch Sex Behav 5, 585–608 (1976). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01541221 refers to an intense interest in watching others engage in activities of private nature, like sexual activities. It doesn’t progress beyond sexual fantasies. For instance, someone might masturbate while watching pornography.

On the other hand, voyeurism turns into a serious voyeuristic disorder when these sexual fantasies cause significant distress to the individuals and impair their social, occupational, and other areas of functioning. It may even be distressing for others as well.

If a person gets sexually aroused by thinking or watching someone undress or have sex, they may have voyeuristic interests 6 Irányi, K., & Somogyi, E. (1980). Das Voyeur-Verhalten und dessen Modifizierung unter Alkoholeinfluss [The voyeur behavior and its modification under the influence of alcohol]. Psychiatrie, Neurologie, und medizinische Psychologie, 32(4), 199–205 . .

However, these interests are problematic when they take actions that violate a person’s right to consent or privacy. It is a matter of medical concern when a person cannot control his/her voyeuristic urges.

Symptoms Of Voyeuristic Disorder

The common voyeuristic disorder symptoms are as follows:

- Persistent and intense sexual arousal from fantasizing or watching an unsuspecting person naked, disrobing, or engaging in sexual activity for at least six months

- Experiencing sexual pleasure from watching people defecate

- Eavesdropping on a highly erotic conversation

- Masturbating or having sexual fantasies while watching a person, without any interest in sexual intercourse

- Severe distress and dysfunction in social and professional lives

- Violating a person’s privacy in their home, locker room, or similar areas

- Watching people engage in sexual activity without their consent

- Entering an area illegally to watch people in their intimate moments

- Filming or photographing a person without their permission

- Feeling frustrated or stressed when one can’t engage in voyeuristic behaviors

- Inability to get sexually aroused without watching others

- Inability to resist voyeuristic activities even when its detrimental to their health and well-being

What Causes Voyeuristic Disorder?

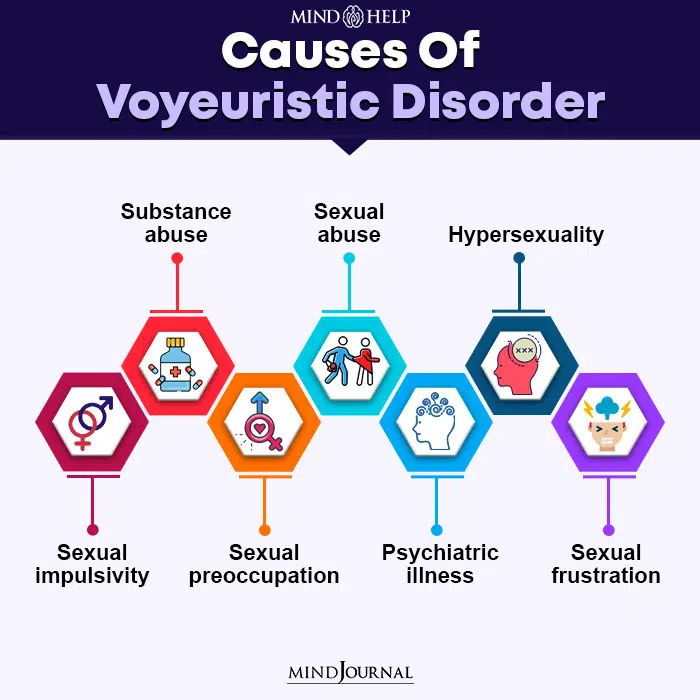

The exact causes of voyeuristic disorder are unknown. However, this condition is associated with several risk factors that fuel behavioral and conduct disorders linked to sexual arousal or urges.

Experts, researching into voyeuristic disorder causes, believe that his disorder originates from accidentally seeing someone naked or undressed, or participating in sexual activity. This further triggers the individuals suffering from voyeuristic disorders to further participate in these activities to the point where it is not considered acceptable or ‘normal’.

Adult males with voyeuristic disorder first become aware of their sexual interests in secretly watching unsuspecting persons in their intimate moments during adolescence. However, people with voyeuristic tendencies are terrified of getting caught or admitting that they have the condition.

Other factors that contribute to voyeuristic disorder risks include:

- Substance abuse

- Sexual abuse

- Hypersexuality 7 Fong T. W. (2006). Understanding and managing compulsive sexual behaviors. Psychiatry (Edgmont (Pa. : Township), 3(11), 51–58.

- Sexual preoccupation

- Sexual impulsivity

- Psychiatric illness

- Guilt, shame, or intense sexual frustration

Read More About Sexual Orientation Here

Responsible Behavior Related To Voyeurism

Some people with voyeuristic interests refuse to engage in behaviors that may harm someone else. Hence, they redirect their interests in other ways without violating anyone’s consent or privacy. These include:

1. Pornography

Voyeurism is a very popular genre in pornography. Adult films frequently show instances of violated privacy or uphold events from a voyeur’s point of view. Experts contend that watching pornography or consuming nude magazines and erotic literature can be one of the ways to cope with voyeuristic disorder.

2. Role-playing

If the person prefers a more hands-on action, he/she can try role-playing with consenting partners. In such cases, it is possible to set up any number of scenarios that may interest the individual, including watching from a distance or video recording. It is important to keep in mind that the individuals involved should consent to the role-playing act.

Moreover, individuals and couples can avail the services of sex-positive communities or organizations that invite people in groups or one-on-one settings to engage in sexual exploration.

3. Erotic podcasts

If the person prefers imagination over action, there are several websites from which the individual can download erotic podcasts. Erotic podcasts 8 Rojo López, A. M., Ramos Caro, M., & Espín López, L. (2021). Audio Described vs. Audiovisual Porn: Cortisol, Heart Rate and Engagement in Visually Impaired vs. Sighted Participants. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 661452. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.661452 allow a person to listen to someone engaging in sexual activity or roll with the story told from the perspective of the voyeur.

Comorbid Conditions Associated With Voyeuristic Disorder

There are several comorbid conditions associated with this disorder, including:

- Exhibitionistic disorder 9 Långström, N. The DSM Diagnostic Criteria for Exhibitionism, Voyeurism, and Frotteurism. Arch Sex Behav 39, 317–324 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9577-4

- Attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder (ADHD)

- Anti-social behaviors

- Hypersexuality

- Conduct disorders

- Personality Disorders

Read More About Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Here

Diagnosing Voyeuristic Disorder

If an individual is worried about his/her overwhelming voyeuristic behavior, it is important to seek medical attention. Voyeuristic disorder can only be diagnosed by a licensed medical or mental health professional.

The mental health professional may ask a series of questions about the patient’s sexual history, sex life, and medical history and plan the diagnosis and treatment process based on the revelations.

The DSM-5 has laid down the diagnostic criteria for voyeuristic disorder:

- Recurrent and intense sexual gratification or sexual behavior from observing unsuspecting targets when they are naked, disrobing, or engaging in sexual activity of any kind for a period of at least six months

- Exhibiting stress that leads them to seek sexual gratification from observing at least three or more unsuspecting targets when they are naked, disrobing, or engaging in sexual activity of any kind

- This condition causes clinical distress and/or social and occupational impairment

Voyeuristic disorder isn’t diagnosed in teenagers or children, as harboring a sense of curiosity and fascination about bodies and sexual activities are considered a normal aspect of growing up.

However, individuals who are above the age of 18 and appear to be exhibiting conduct disorders that violate the privacy of people around them should be diagnosed.

How To Treat Voyeuristic Disorder

The first step toward healing is to recognize and acknowledge that a person’s voyeuristic interests amount to a disorder. It’s often hard for people to realize paraphilic disorders since they are not aware of their behavior, so it is important to pay attention to such behaviors. A parent, spouse, friend, or legal authority may be the first one to recognize the disorder and recommend medical help.

The common voyeuristic disorder treatment methods include:

1. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)

CBT 10 Långström, N. The DSM Diagnostic Criteria for Exhibitionism, Voyeurism, and Frotteurism. Arch Sex Behav 39, 317–324 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9577-4 involves the identification of negative thoughts and patterns that govern the behavior of people with mental illness. After identification, the therapist helps the patient replace those negative thoughts with positive thoughts and approaches.

The therapist may also help the patient develop impulse control by finding new ways to manage their sexual curiosity, identifying locations or situations that are triggering the voyeuristic disorder symptoms, and developing coping strategies.

Read More About Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Here

2. Group therapy

Joining a support group can also go a long way in coping with the symptoms of voyeuristic disorder. Connecting with other people who are going through similar issues creates a space that is free of judgment and provides room for conversing about challenges and coping mechanisms.

Read More About Group Therapy Here

3. Medications

Medications may be prescribed to treat any associated comorbid conditions, such as depression or anxiety. Some studies 11 Clayton, A. H., McGarvey, E. L., Abouesh, A. I., & Pinkerton, R. C. (2001). Substitution of an SSRI with bupropion sustained release following SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 62(3), 185–190. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v62n0309 found that putting patients on fluoxetine and treating their voyeuristic behavior as an obsessive/compulsive disorder showed significant results.

Another 2010 study 12 Metzl, J. (2004). From scopophilia toSurvivor: A brief history of voyeurism. Textual Practice, 18(3), 415-434. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502360410001732935 revealed that using a mixture of antidepressants and antipsychotic medications can be used to successfully treat this disorder. Some antiandrogenic drugs 13 McLeod D. G. (1993). Antiandrogenic drugs. Cancer, 71(3 Suppl), 1046–1049. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19930201)71:3+<1046::aid-cncr2820711424>3.0.co;2-m that suppress intense sexual drive can also be used to treat patients with this condition.

4. Other methods

There is some evidence that shows that pornography can be used as a treatment. However, this is based on the idea that countries with pornography censorship have high rates of voyeurism.

Research 14 Jackson B. T. (1969). A case of voyeurism treated by counterconditioning. Behaviour research and therapy, 7(1), 133–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(69)90058-8 shows that voyeurs shifting the focus of their voyeuristic behaviors by looking at graphic pornography or nudes in adult magazines have been successful in addressing this disorder. In fact, consuming pornography is actually fulfilling voyeuristic desires without breaking any law.

Ways To Cope With Voyeuristic Disorder

Consider the following measures for coping with voyeuristic disorder:

- Acknowledge that you have a voyeurism-related disorder and that you need medical attention.

- Communicate with your family and friends about your disorder.

- Talk honestly with your romantic or sexual partner(s) about your sexual urges and fantasies.

- Consult with a sex therapist to explore your options for fulfilling your sexual urges and fantasies.

- Minimize the use of alcohol and other addictive substances which may increase your inappropriate urges.

- Devise self-help strategies for reducing compulsive behaviors and co-occurring mental health conditions.

- Seek social support in a community of other individuals struggling with voyeuristic disorder.

This disorder begins as a fairly common sexual interest, but then it becomes a concern where the individual cannot control his/her sexual desires and fantasies.

As the disorder grows severe, it begins to impact the patient’s daily life as well as make others feel uncomfortable or violated. Nonetheless, with treatment for voyeuristic disorder (using therapy and medication), it is possible to recover from this condition.

So if you are experiencing any voyeuristic disorder symptoms, it is advisable to seek professional help and timely avail treatment plans and coping strategies. This will allow you to lead a normal and healthy life, without violating or threatening anyone’s privacy.

Voyeuristic Disorder At A Glance

- Voyeuristic disorder is a paraphilic disorder in which a person gets sexually aroused by observing others during intimate moments.

- It is illegal, immoral, and undesirable behavior that violates people’s privacy.

- The condition is prevalent in people with hypersexuality, histories of sexual abuse and mental illness, etc.

- Its symptoms include sexual frustration, break-ins, obsessive consumption of pornography, etc.

- It can be easily treated with therapy and medication.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. what is the root cause of voyeuristic disorder.

Voyeuristic disorder does not have a fixed set of causes, but certain factors like sexual abuse, hypersexuality, substance abuse, and addiction to pornography and other erotic works increase the risks of developing the disorder.

2. What are paraphilic disorders?

Paraphilic disorders are behavioral disorders that involve intense, recurrent, and sexually arousing fantasies, urges, or conduct directed at inanimate objects, children, or nonconsenting adults.

3. Is voyeurism a mental disorder?

Voyeurism in itself is not a disorder. But, when a person becomes too consumed and distressed by voyeuristic thoughts and cannot function or act normally because of his/her fantasies, it becomes a disorder.

References:

- 1 Fisher KA, Marwaha R. Paraphilia. [Updated 2022 Mar 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554425/

- 2 McManus, M. A., Hargreaves, P., Rainbow, L., & Alison, L. J. (2013). Paraphilias: definition, diagnosis and treatment. F1000prime reports, 5, 36. https://doi.org/10.12703/P5-36

- 3 McManus, M. A., Hargreaves, P., Rainbow, L., & Alison, L. J. (2013). Paraphilias: definition, diagnosis and treatment. F1000prime reports, 5, 36. https://doi.org/10.12703/P5-36

- 4 Fedoroff, J. P. (2019). Voyeuristic disorder. The Paraphilias, 209-216. https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780190466329.003.0009

- 5 Smith, R.S. Voyeurism: A review of literature. Arch Sex Behav 5, 585–608 (1976). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01541221

- 6 Irányi, K., & Somogyi, E. (1980). Das Voyeur-Verhalten und dessen Modifizierung unter Alkoholeinfluss [The voyeur behavior and its modification under the influence of alcohol]. Psychiatrie, Neurologie, und medizinische Psychologie, 32(4), 199–205 .

- 7 Fong T. W. (2006). Understanding and managing compulsive sexual behaviors. Psychiatry (Edgmont (Pa. : Township), 3(11), 51–58.

- 8 Rojo López, A. M., Ramos Caro, M., & Espín López, L. (2021). Audio Described vs. Audiovisual Porn: Cortisol, Heart Rate and Engagement in Visually Impaired vs. Sighted Participants. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 661452. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.661452

- 9 Långström, N. The DSM Diagnostic Criteria for Exhibitionism, Voyeurism, and Frotteurism. Arch Sex Behav 39, 317–324 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9577-4

- 10 Långström, N. The DSM Diagnostic Criteria for Exhibitionism, Voyeurism, and Frotteurism. Arch Sex Behav 39, 317–324 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9577-4

- 11 Clayton, A. H., McGarvey, E. L., Abouesh, A. I., & Pinkerton, R. C. (2001). Substitution of an SSRI with bupropion sustained release following SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 62(3), 185–190. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v62n0309

- 12 Metzl, J. (2004). From scopophilia toSurvivor: A brief history of voyeurism. Textual Practice, 18(3), 415-434. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502360410001732935

- 13 McLeod D. G. (1993). Antiandrogenic drugs. Cancer, 71(3 Suppl), 1046–1049. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19930201)71:3+<1046::aid-cncr2820711424>3.0.co;2-m

- 14 Jackson B. T. (1969). A case of voyeurism treated by counterconditioning. Behaviour research and therapy, 7(1), 133–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(69)90058-8

Mental Health Topics (A-Z)

- Abrasive Personality

- Academic Problems And Skills

- Actor-Observer Bias

- Addiction And The Brain

- Causes Of Addiction

- Complications Of Addiction

- Stages Of Addiction

- Types Of Addiction

- Adjustment Disorder

- Adverse Childhood Experiences

- Premature Aging

- Aging And Mental Health

- Agoraphobia

- Agreeableness

- Alcohol Use Disorder

- Alcohol Withdrawal

- Alcohol And Mental Health

- End Stage Alcoholism

- Treatment For Alcoholism

- Alienation

- Alzheimer’s Disease

- Anger Management

- Animal Behavior

- Treatment For Anorexia Nervosa

- Anthropomorphism

- Anthropophobia

- Antidepressants

- Arachnophobia

- Art Therapy

- Causes Of Asperger’s Syndrome

- Coping With Asperger Syndrome

- Symptoms Of Asperger’s Syndrome

- Treatment For Asperger’s Syndrome

- Astraphobia

- Attachment styles

- Attachment Theory

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- Avoidant Personality Disorder

- Bathophobia

- Behavioral Change

- Behavioral Economics

- Bereavement

- Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviors (BFRB)

- Bibliophobia

- Bibliotherapy

- Big 5 Personality Traits

- Binge Drinking

- Binge Eating Disorder

- Binge Watching

- Causes Of Bipolar Disorder

- Treatment of Bipolar Disorder

- Birthday Depression

- Body language

- Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD)

- Causes Of Boredom

- How To Improve Brain Health

- Nutrition And Brain Health

- Brain Science

- Bulimia Nervosa

- Causes Of Burnout

- The Bystander Effect

- Caffeine Use Disorder

- Capgras Delusion

- Caregiving

- Character Traits

- Child Development

- Child Discipline

- Christmas And Mental Health

- Types Of Chronic Pain

- Chronomentrophobia

- City Syndromes

- Traits Of Cluster B Personality Disorder

- Cluster B Personality Disorders Treatment

- Coping With Codependency

- Effectiveness Of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

- Types of Cognitive Biases

- Cognitive Decline

- Cognitive Dissonance

- Color Psychology

- Commitment Phobia

- Communication Disorders

- Compassion Fatigue

- Compulsive Buying Disorder

- Conduct Disorder

- Confirmation Bias

- Conscientiousness

- Consumer Behavior

- Consumerism

- Couples Therapy

- Decision-making

- Default Mode Network (DMN) And Alzheimer’s Disease

- Defense Mechanisms

- Delusional Disorder

- Dependent Personality Disorder

- Depression

- Depression At Night

- Dermatillomania

- Discrimination

- Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD)

- Dissociative Disorders

- Treatment Of Dissociative Fugue

- Dissociative Identity Disorder

- Dissociative Trance Disorder

- Domestic Violence and Mental Health

- Dopamine Deficiency

- How To Increase Dopamine

- Dream Interpretation

- Drug Abuse

- Drunkorexia

- Coping With The Dunning-Kruger Effect

- Types of Dysgraphia

- Dyspareunia

- Dysthymia (Persistent Depressive Disorder)

- Causes Of Eating Disorders

- Self Help Strategies For Eating Disorders

- Treatment For Eating Disorders

- Ego Depletion

- Embarrassment

- Emotional Regulation

- Emotional Abuse

- Improving Emotional Intelligence (EI)

- Empathic Accuracy

- Environmental Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Executive Function

- Exhibitionistic Disorder

- Expressive Language Disorder

- Signs Of An Extrovert

- False Memory

- Types of Family Dynamics

- Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

- Financial Therapy

- First Impression

- Forensic Psychology

- Four Pillars Of Mental Health

- Free Will

- Freudian Psychology

- Friends And Mental Health

- Gambling Disorder

- Ganser Syndrome

- Gaslighting

- Gender Dysphoria

- Gender and Alienation

- Gender Bias

- Causes Of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

- Coping With Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

- Symptoms Of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder Treatment

- Geographical Psychology

- Gerascophobia

- Geriatric Depression

- Group Therapy

- Growth Mindset

- How To Strengthen Your Gut Feeling

- How To Form Effective Habits

- Hakomi Therapy

- Halo Effect

- Healing From Trauma

- Heliophobia

- Hexaco Personality Test

- Highly Sensitive Person (HSP)

- Histrionic Personality Disorder

- Hoarding Disorder

- Holiday Depression

- Holiday Stress

- Types Of Holistic Health Treatments

- Homelessness and Mental Health

- Homosexuality

- Horn Effect

- Human Trafficking And Mental Health

- Hypersomnia

- Illness Anxiety Disorder

- Imagination

- Impostor Syndrome

- Impulse Buying

- Impulse Control Disorder (ICD)

- Inspiration

- Intellectual Disability

- Internet Addiction

- Introversion

- Kleptomania

- Laughter Therapy

- Learned Helplessness

- Life Satisfaction

- Types Of Life Skills

- Living With Someone With Mental Illness

- Locus Of Control

- How To Practice Healthy Love In Relationships

- Love Addiction

- Love And Relationships

- Love And Mental Health

- Self Love Deficit Disorder

- Triangular Theory Of Love

- Machiavellianism

- Mageirocophobia

- Benefits Of Magical Thinking

- Magical Thinking OCD

- Causes Of Depression

- Coping With Depression

- Treatment For Depression

- Types Of Depression

- Maladaptive Daydreaming

- Manic Depression

- Manic Episode

- Mens Mental Health

- Mental Exercises

- Mental Health And Holidays

- Children’s Mental Health Awareness

- Mental Health Disability

- Mental Illness

- Mental Wellness In New Year

- Metacognition

- Microaggression

- Microexpressions

- Midlife Crisis

- Mindfulness

- Money and Mental Health

- Mood Disorders

- Motivated Reasoning

- Music and Mental Health

- Music Therapy

- Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI)

- Nature and Mental Health

- Necrophobia

- Neuroticism

- Night Eating Syndrome

- Causes Of Nightmare Disorder

- Treatment for Nightmare Disorder

- Nyctophobia

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Obsessive Love Disorder

- Online Counseling

- Online Therapy

- Onychophagia (Nail Biting)

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD)

- Panic Disorder

- Panic Disorder with Agoraphobia

- Causes Of Paranoia

- Coping With Paranoia

- Helping Someone With Paranoia

- Symptoms Of Paranoia

- Treatment Of Paranoia

- Types Of Paranoia

- Paranoid Personality Disorder

- Coping With Paranoid Schizophrenia

- Helping Someone With Paranoid Schizophrenia

- Treatment of Paranoid Schizophrenia

- Parental Alienation Syndrome

- Parkinson’s Disease

- Passive Aggression

- Pathological Jealousy

- Perfectionism

- Performance Anxiety

- Perinatal Mood And Anxiety Disorders (PMADs)

- Personality

- Pet Therapy

- Pica Disorder

- Positive Psychology

- Causes Of PTSD

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Children

- Coping With Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Diagnosis Of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Symptoms Of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Treatment Of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Treatment Of Postpartum Depression

- Postpartum Psychosis

- Premature Ejaculation

- Procrastination

- Psychoanalysis

- The Psychology Behind Smoking

- Psychotherapy

- Psychotic Depression

- Reactive Attachment Disorder

- Recovered Memory Syndrome

- Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria

- Relationships

- Reminiscence Therapy

- Repetitive Self-Mutilation

- Restless Legs Syndrome

- Retrograde Amnesia

- Rumination Disorder

- Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD)

- Schema Therapy

- Childhood Schizophrenia

- Hebephrenia (Disorganized Schizophrenia)

- Treatment Of Schizophrenia

- Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorder

- Selective Mutism

- Self-Actualization

- Self Care And Wellness

- Self-Control

- Self-disclosure

- Self-Esteem

- Self-Monitoring

- Self-motivation

- Self-Serving Bias

- Sensory Processing Disorder

- Separation Anxiety Disorder

- Separation Anxiety in Relationships

- Serial Killers

- Sexual Masochism Disorder

- Sexual Orientation

- Shared Psychotic Disorder

- Signs And Symptoms Of Schizophrenia

- Situational Stress

- Situationship

- Non-Rapid Eye Movement (NREM) Sleep Arousal Disorders

- Parasomnias

- Sleep Disorders

- Sleep Paralysis

- Sleeplessness

- Sleep Meditation

- Sociability

- Social Anxiety Disorder

- Social Media Addiction

- Social Media And Mental Health

- Somatic Symptom Disorder ( SSD )

- Specific Reading Comprehension Deficit

- Spirituality

- Stage Fright

- Stendhal Syndrome

- Stereotypes

- Acute Stress Disorder

- Stress Management

- Suicide And Mental Health

- Suicide Grief

- Teen Dating Violence

- Time Management Techniques

- 10 Helpful Time Management Tips

- Tobacco-Related Disorders

- Toxic Love Disorder

- Transgender

- Transient Tic Disorder

- Trauma and Addiction

- Trichotillomania

- Venustraphobia

- Video Game Addiction

- Virtual Reality and Mental Health

- Weight Watchers

- Werther Syndrome

- Good Mental Health

- Stockholm Syndrome

- Work and Mental Health

- How To Cure Workaholism

- Workplace Bullying

- Workplace Stress

- Yoga For Mental Health

- Young Male Syndrome

- Zeigarnik Effect

- Zone of Proximal Development

Copyright 2024

Typically replies within minutes

WhatsApp Us

🟢 Online | Privacy policy

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

40 years and counting: the team behind Voyager’s space odyssey

In 1977, Voyager 1 and 2 started their one-way journey across our galaxy, travelling a million miles a day. Jonathan Margolis meets the dedicated team keeping the craft moving

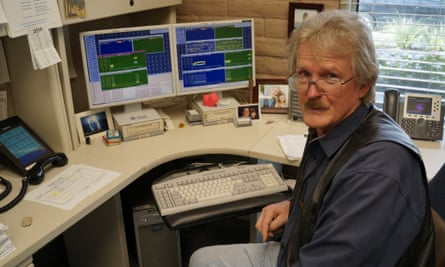

O n a chilly March morning, Steve Howard, aged 65, is at work in his office on the northern edge of Pasadena, California. Two computer screens are squeezed on to his corner desk along with family photos, a tissue box and tins of Altoids Curiously Strong Peppermints. The office is in a quiet business park by a workaday main road. Next to it is a McDonald’s, where people linger for hours over a $1 coffee, seemingly to keep warm. Over the road there’s a scruffier burger joint, Jim’s, with an M missing from its sign – and, visible from Howard’s window, a landscaping supplies yard.

If the few people walking by on West Woodbury Road, Altadena, or popping into the landscaping place for some patio paving slabs were to peer into Howard’s office, they might guess, seeing the graph-covered twin screens and a third PC at the other end of the desk, that he was, perhaps, a financial adviser or a day trader. But what Steve Howard is actually doing makes this very ordinary all-American scene quite extraordinary.

Howard is a Nasa mission controller. He is sending instructions to a probe in interstellar space, 12 billion miles from Earth, beyond Pluto and escaping our Solar System at 1 million miles a day. The 815kg craft, Voyager 1 , is one of two identical machines that for many years now have been the furthest human-made objects from Earth. Howard’s computer code takes 17 hours at the speed of light to reach Voyager 1, the furthest travelled. Voyager 2, which is leaving the solar system in a different direction, is 3bn miles closer. The responses, from transmitters on the twin probes running 23 watts of power – have the power of a billionth of a billionth of a watt by the time they reach Earth.

“So here, see, I have Voyager 1’s status and information up, at least as it was 17 hours ago,” Howard explains. “Right now I’m connected to our Canberra station, and these are seven commands, set to radiate one every five minutes starting 30 minutes from now. They’re to verify that the spacecraft can receive and reset its timer. Such is the speed of light, I will not get confirmation that all is OK until late tomorrow night, but it will have entailed a 25bn-mile round trip, so that’s not too bad.”

It is no hyperbole to say, then, that the man tapping away at his keyboard on the office park next to McDonald’s is a key figure in the greatest-ever feat of human exploration. There was nothing like the Voyager 1 and 2 missions to the outer planets before they launched in 1977, and although three outer planet probes launched last decade are still on mission, no new ventures into deep space are planned.

Space exploration tends to be more inward looking today than in the so-called Space Age. The famous Curiosity rover is of course still working wonders on Mars, but almost all the US’s coming spacecraft will be restricted to studying our own planet, with special attention to environmental issues. The Voyagers and the people like Howard who still work on them full-time – having, in many cases, done so their entire adult life – are from a different era, when budgets were unrestrained, audaciousness (and showing off to the Soviets) was in vogue and the environment was a concern only for hippies.

Voyager’s spindly limbed, Transit-van-sized machines have been travelling at around 37,000mph for almost 38 years. When they were launched, wooden-framed Morris 1000 Traveller cars had only recently stopped being produced by British Leyland in Oxford. The Voyagers’ on-board computers are early 1970s models that were advanced then but are puny now – an iPhone’s computer is some 200,000 times faster and has about 250,000 times more memory than Voyager’s hardware.

The Voyager mission’s early 70s-inspired and -equipped trip, originally meant to last four years, took the craft initially to Jupiter, then Saturn, then, as a bonus since everything was working well, to Uranus and finally Neptune, after which they spun off into their journey around the Milky Way. Against all expectations their vintage electronics and thrusters are still, mostly, working in the intense -253C cold of outer space. What’s more, their sensors are sending data all day every day, as some will continue to do until 2036. That said, by 2025 almost all the instruments sending worthwhile scientific information will be turned off as the ships’ tiny plutonium-238 power sources dwindle.

The on-board camera on each Voyager, for instance, was deactivated to save power 25 years ago last Valentine’s Day. This was after Voyager 1 took a now-iconic “family portrait” of the solar system from almost 4bn miles out. It captured Neptune, Uranus, Saturn, Jupiter, Venus, Earth (seen, in the late astrophysicist Carl Sagan ’s phrase, as a “pale blue dot”) and the Sun, by then just a tiny point of light. By 2036 the craft will be nearly out of the solar system altogether and will remain dead, although in perfect condition, probably for eternity.

It is the Voyager spacecrafts’ longevity, despite their becoming a bit arthritic in later years, that has led to their Mission Control being moved out to an office park. The problem for Nasa – more correctly for the California Institute of Technology’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory , which runs most robotic missions for Nasa – is that high-profile later expeditions, most notably Curiosity, have used the available space on CalTech’s campus. Proud as JPL is of the amazing Voyager story, the craft are not taking photos or doing a lot of sexy science any more and may not encounter anything of much interest for another 40,000 years, by which time they will be deaf and mute. So, like a great grandfather who stubbornly refuses to do the decent thing, the Earth end of the Voyager programme and the spacecraft’s devoted carers have been put in a somewhat off-piste rest home.

Engineers are not given to emotion, but the romance of this incredible voyage of discovery has, by their own account, kept the ageing mission team together. Even latecomers, who were at school when Voyager was launched, have been working on the same mission for 30 years and more. “I’m in my mid-50s and treat the craft like my ageing parents,” says Suzy Dodd , who was 16 at launch, joined as a graduate student and whose card now proclaims surely one of the cooler job titles in science: Project manager, Voyager Interstellar Mission.

“You treat them with a certain amount of reverence; you know they’re stately spacecraft, venerable senior citizens, and you want to do everything possible for them to have a healthy lifetime,” she says. “You need to help them a bit because things have failed and you want to be careful other things don’t. Most of the engineers here have dedicated their career to this project. They have turned down opportunities for promotions and other things because they like Voyager so much they want to stay with it.”

It is clear talking to Voyager staff that they genuinely love their spacecraft, even though most were too young to see them before they flew, and it is more than possible that the older ones will have died before the Voyagers bleep their last. But as engineers, they have mixed feelings about the most famous aspect of that romance, the “golden record” that each craft carries. This is a gold-covered copper LP, packed with a needle and cartridge (plus instructions), and containing, in groove form, 115 photos from Earth, a selection of natural sounds from surf to whales, music from a variety of cultures and eras (the modern west is represented by Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B Goode”) and spoken greetings in 55 languages, from Akkadian, spoken in Sumer about 6,000 years ago, to Welsh.

Carl Sagan, who had the initial idea for the record, wrote in the 1970s: “The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced spacefaring civilisations in interstellar space. But the launching of this bottle into the cosmic ocean says something very hopeful about life on this planet.” Sagan’s son Nick, then an infant, now a science-fiction novelist and screenwriter (his credits include Star Trek episodes), recorded the English message: “Hello from the children of planet Earth.” But one sure to make many tear up is the Mandarin: “Hope everyone’s well. We are thinking about you all. Please come here to visit when you have time.” (The messages are on the Voyager website, voyager.jpl.nasa.gov ).

Voyager’s mission controllers are less starry-eyed than Sagan about the golden records. You sense some feel that it was too much of a bow to religious sentiment. Steve Howard is one of the more positive on the record question. “Even though Earth may not be here, some intelligent being could pick it up and detect it. I would say that many of the civilisations are much more advanced and would detect something like that and simply go in and decipher it,” he says.

Suzy Dodd’s view is more typical of the team’s. “I think it’s a great idea to get humans and mankind thinking what-ifs. Let’s send a picture of ourselves vintage 1977 and put it on a spacecraft and send it out there forever. I think it’s done to connect us to the spacecraft more than for an alien running into it. I’m of the opinion that space is very empty and the chances of something finding it are remote. But that doesn’t diminish the fact that we’ve got a little time capsule out there travelling through space and now orbiting around in our galaxy. And that’s us.”

For the mission’s much-honoured chief scientist and spokesman since 1972, CalTech professor Ed Stone, aged 79, the romance of Voyager lies more in what it has discovered since he joined the project aged 36. “Yes, the Space Age was a young man’s game back then,” he says, not a little ruefully, sitting on a park bench on the green university campus. “We all knew we were on a mission of discovery. We just had no idea how much discovery there would be. We just kept finding things we didn’t know were there to be found.

“For example, before Voyager, the only known volcanoes in the solar system were here on Earth. Then we flew by Jupiter’s moon, Io, which had 10 times the volcanic activity of Earth. Ten times! We detected hot lakes of lava on the surface. That was the first major discovery and it set the tone for the rest of the mission. And there are five instruments still working. But by 2025 the last will go off.”

He doesn’t quite add that by then he will be nearly 90, but does say, smiling: “Thing is, if you want to do space experiments, you have to be optimistic that it’s all going to work and that you’re going to find something worth the work. And you have to be patient, because nothing happens fast in space.”

Stone explains how, although it’s widely considered freakish that the Voyager crafts are still working so well – a TV left permanently on since Jim Callaghan’s day would be hardly working today – it’s less surprising to people like him who built them. To anyone familiar with the inside of a vintage radio or TV, the hand-soldered circuit boards, capacitors, transistors, resistors and so on that run a Voyager would look reassuringly familiar, which isn’t the case with a modern computer or phone, whose microchip-studded innards look more like something out of a UFO.

But the parts in Voyager weren’t as ordinary as they looked. Suzy Dodd, a “newcomer” to the project with just over 30 years’ service, has also been intrigued by the spacecraft’s durability. “The robustness is unique,” she says. “If you talk to the older engineers, they’ll say: ‘Well, we were told to make a four-year mission, but we realised if you just used this higher-rated component, it would last twice as long.’ So they did that. They just didn’t tell anybody. The early engineers were very conscious of trying to make this last as long as possible and, quite frankly, being not as forthcoming with information about the types of parts they were using.”

Even so, Ed Stone says, there have been problems. A ground controller’s error in April 1978 meant that Voyager 2 switched itself irretrievably to its back-up receiver – meaning that the craft has been receiving transmissions from Earth on a dodgy back-up radio for almost the entire mission. One of the original thrusters also failed.

For spacecraft 12bn miles from home and in their dotage, the Voyagers are quite tranquil machines today, but they do need watching. As Steve Howard is in his office inputting code in primordial programming language, on the floor of what passes for the main mission control Enrique Medina, 65, is watching streams of engineering data from the craft. A computer engineer, Medina is another of the eight full- and part-time controllers.