Is Time Travel Possible?

We all travel in time! We travel one year in time between birthdays, for example. And we are all traveling in time at approximately the same speed: 1 second per second.

We typically experience time at one second per second. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

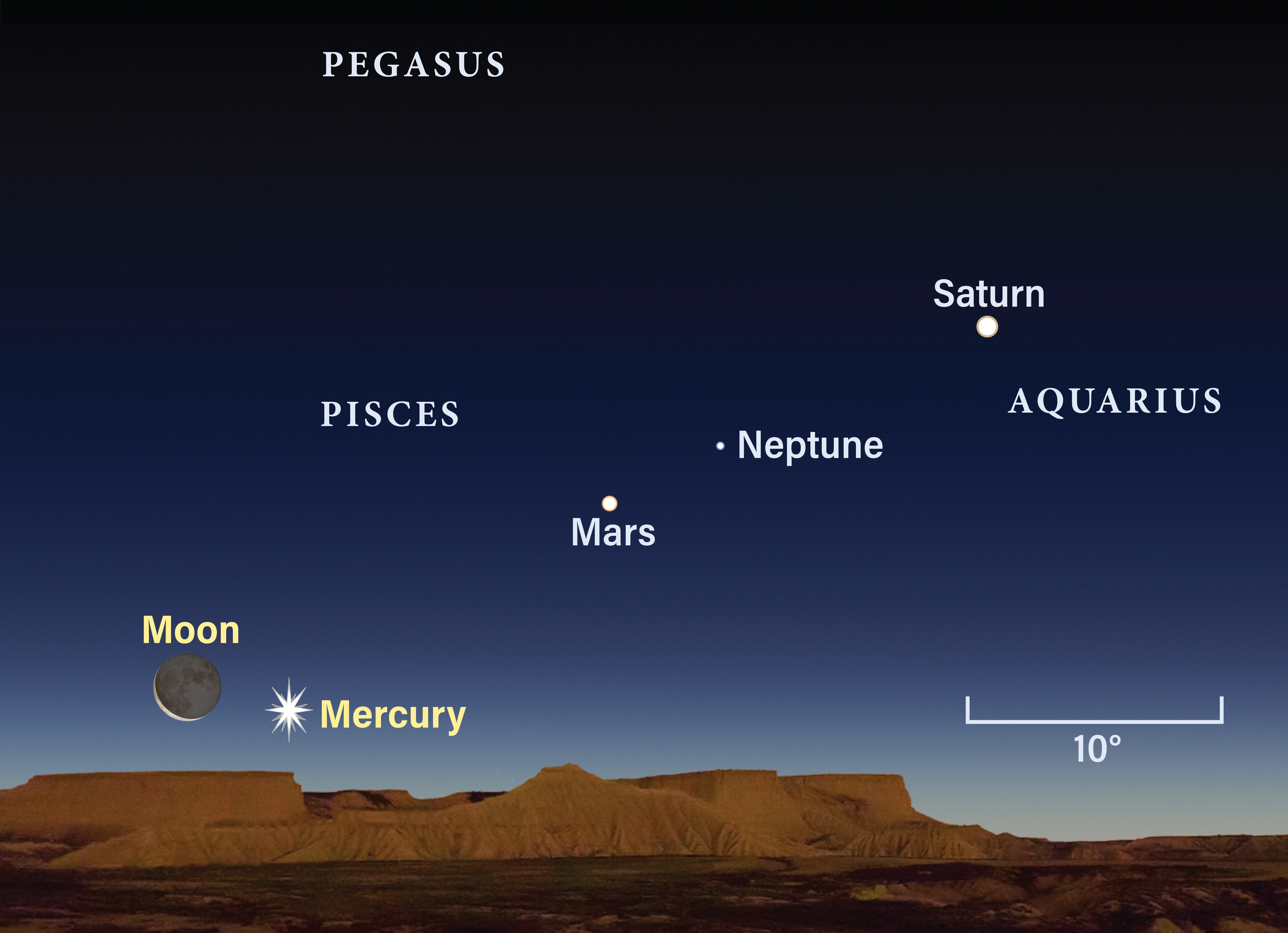

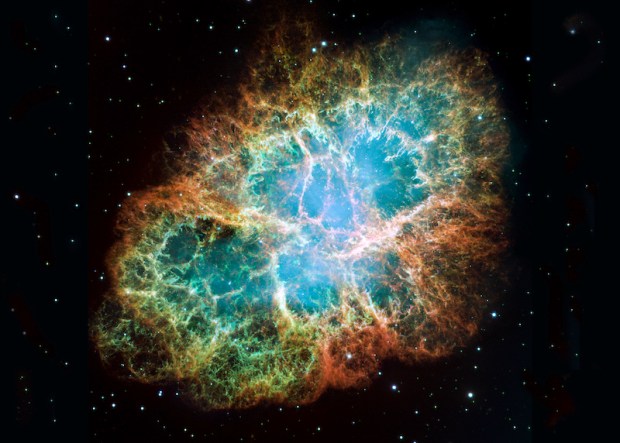

NASA's space telescopes also give us a way to look back in time. Telescopes help us see stars and galaxies that are very far away . It takes a long time for the light from faraway galaxies to reach us. So, when we look into the sky with a telescope, we are seeing what those stars and galaxies looked like a very long time ago.

However, when we think of the phrase "time travel," we are usually thinking of traveling faster than 1 second per second. That kind of time travel sounds like something you'd only see in movies or science fiction books. Could it be real? Science says yes!

This image from the Hubble Space Telescope shows galaxies that are very far away as they existed a very long time ago. Credit: NASA, ESA and R. Thompson (Univ. Arizona)

How do we know that time travel is possible?

More than 100 years ago, a famous scientist named Albert Einstein came up with an idea about how time works. He called it relativity. This theory says that time and space are linked together. Einstein also said our universe has a speed limit: nothing can travel faster than the speed of light (186,000 miles per second).

Einstein's theory of relativity says that space and time are linked together. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

What does this mean for time travel? Well, according to this theory, the faster you travel, the slower you experience time. Scientists have done some experiments to show that this is true.

For example, there was an experiment that used two clocks set to the exact same time. One clock stayed on Earth, while the other flew in an airplane (going in the same direction Earth rotates).

After the airplane flew around the world, scientists compared the two clocks. The clock on the fast-moving airplane was slightly behind the clock on the ground. So, the clock on the airplane was traveling slightly slower in time than 1 second per second.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Can we use time travel in everyday life?

We can't use a time machine to travel hundreds of years into the past or future. That kind of time travel only happens in books and movies. But the math of time travel does affect the things we use every day.

For example, we use GPS satellites to help us figure out how to get to new places. (Check out our video about how GPS satellites work .) NASA scientists also use a high-accuracy version of GPS to keep track of where satellites are in space. But did you know that GPS relies on time-travel calculations to help you get around town?

GPS satellites orbit around Earth very quickly at about 8,700 miles (14,000 kilometers) per hour. This slows down GPS satellite clocks by a small fraction of a second (similar to the airplane example above).

GPS satellites orbit around Earth at about 8,700 miles (14,000 kilometers) per hour. Credit: GPS.gov

However, the satellites are also orbiting Earth about 12,550 miles (20,200 km) above the surface. This actually speeds up GPS satellite clocks by a slighter larger fraction of a second.

Here's how: Einstein's theory also says that gravity curves space and time, causing the passage of time to slow down. High up where the satellites orbit, Earth's gravity is much weaker. This causes the clocks on GPS satellites to run faster than clocks on the ground.

The combined result is that the clocks on GPS satellites experience time at a rate slightly faster than 1 second per second. Luckily, scientists can use math to correct these differences in time.

If scientists didn't correct the GPS clocks, there would be big problems. GPS satellites wouldn't be able to correctly calculate their position or yours. The errors would add up to a few miles each day, which is a big deal. GPS maps might think your home is nowhere near where it actually is!

In Summary:

Yes, time travel is indeed a real thing. But it's not quite what you've probably seen in the movies. Under certain conditions, it is possible to experience time passing at a different rate than 1 second per second. And there are important reasons why we need to understand this real-world form of time travel.

If you liked this, you may like:

A beginner's guide to time travel

Learn exactly how Einstein's theory of relativity works, and discover how there's nothing in science that says time travel is impossible.

Everyone can travel in time . You do it whether you want to or not, at a steady rate of one second per second. You may think there's no similarity to traveling in one of the three spatial dimensions at, say, one foot per second. But according to Einstein 's theory of relativity , we live in a four-dimensional continuum — space-time — in which space and time are interchangeable.

Einstein found that the faster you move through space, the slower you move through time — you age more slowly, in other words. One of the key ideas in relativity is that nothing can travel faster than the speed of light — about 186,000 miles per second (300,000 kilometers per second), or one light-year per year). But you can get very close to it. If a spaceship were to fly at 99% of the speed of light, you'd see it travel a light-year of distance in just over a year of time.

That's obvious enough, but now comes the weird part. For astronauts onboard that spaceship, the journey would take a mere seven weeks. It's a consequence of relativity called time dilation , and in effect, it means the astronauts have jumped about 10 months into the future.

Traveling at high speed isn't the only way to produce time dilation. Einstein showed that gravitational fields produce a similar effect — even the relatively weak field here on the surface of Earth . We don't notice it, because we spend all our lives here, but more than 12,400 miles (20,000 kilometers) higher up gravity is measurably weaker— and time passes more quickly, by about 45 microseconds per day. That's more significant than you might think, because it's the altitude at which GPS satellites orbit Earth, and their clocks need to be precisely synchronized with ground-based ones for the system to work properly.

The satellites have to compensate for time dilation effects due both to their higher altitude and their faster speed. So whenever you use the GPS feature on your smartphone or your car's satnav, there's a tiny element of time travel involved. You and the satellites are traveling into the future at very slightly different rates.

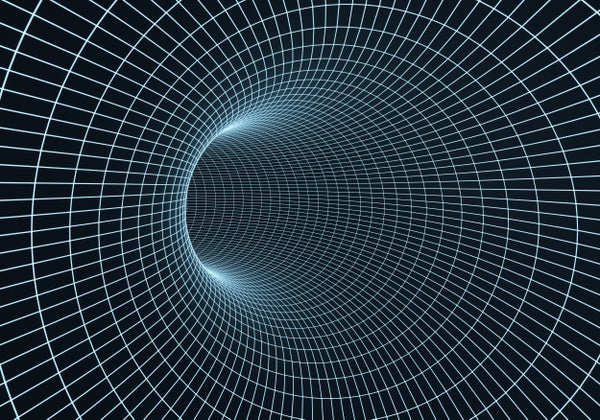

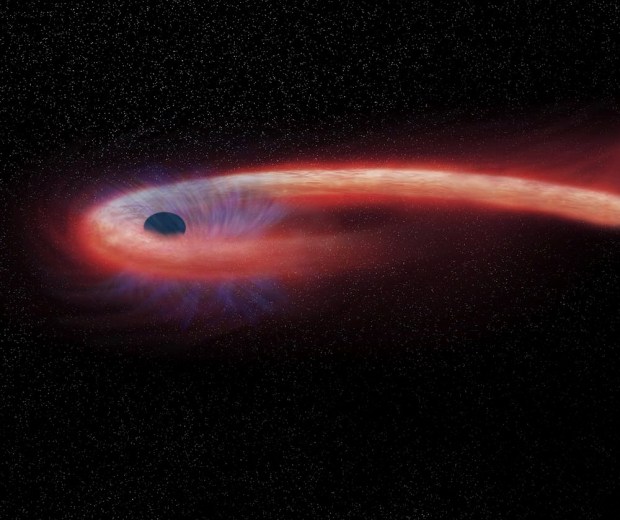

But for more dramatic effects, we need to look at much stronger gravitational fields, such as those around black holes , which can distort space-time so much that it folds back on itself. The result is a so-called wormhole, a concept that's familiar from sci-fi movies, but actually originates in Einstein's theory of relativity. In effect, a wormhole is a shortcut from one point in space-time to another. You enter one black hole, and emerge from another one somewhere else. Unfortunately, it's not as practical a means of transport as Hollywood makes it look. That's because the black hole's gravity would tear you to pieces as you approached it, but it really is possible in theory. And because we're talking about space-time, not just space, the wormhole's exit could be at an earlier time than its entrance; that means you would end up in the past rather than the future.

Trajectories in space-time that loop back into the past are given the technical name "closed timelike curves." If you search through serious academic journals, you'll find plenty of references to them — far more than you'll find to "time travel." But in effect, that's exactly what closed timelike curves are all about — time travel

This article is brought to you by How It Works .

How It Works is the action-packed magazine that's bursting with exciting information about the latest advances in science and technology, featuring everything you need to know about how the world around you — and the universe — works.

There's another way to produce a closed timelike curve that doesn't involve anything quite so exotic as a black hole or wormhole: You just need a simple rotating cylinder made of super-dense material. This so-called Tipler cylinder is the closest that real-world physics can get to an actual, genuine time machine. But it will likely never be built in the real world, so like a wormhole, it's more of an academic curiosity than a viable engineering design.

Yet as far-fetched as these things are in practical terms, there's no fundamental scientific reason — that we currently know of — that says they are impossible. That's a thought-provoking situation, because as the physicist Michio Kaku is fond of saying, "Everything not forbidden is compulsory" (borrowed from T.H. White's novel, "The Once And Future King"). He doesn't mean time travel has to happen everywhere all the time, but Kaku is suggesting that the universe is so vast it ought to happen somewhere at least occasionally. Maybe some super-advanced civilization in another galaxy knows how to build a working time machine, or perhaps closed timelike curves can even occur naturally under certain rare conditions.

This raises problems of a different kind — not in science or engineering, but in basic logic. If time travel is allowed by the laws of physics, then it's possible to envision a whole range of paradoxical scenarios . Some of these appear so illogical that it's difficult to imagine that they could ever occur. But if they can't, what's stopping them?

Thoughts like these prompted Stephen Hawking , who was always skeptical about the idea of time travel into the past, to come up with his "chronology protection conjecture" — the notion that some as-yet-unknown law of physics prevents closed timelike curves from happening. But that conjecture is only an educated guess, and until it is supported by hard evidence, we can come to only one conclusion: Time travel is possible.

A party for time travelers

Hawking was skeptical about the feasibility of time travel into the past, not because he had disproved it, but because he was bothered by the logical paradoxes it created. In his chronology protection conjecture, he surmised that physicists would eventually discover a flaw in the theory of closed timelike curves that made them impossible.

In 2009, he came up with an amusing way to test this conjecture. Hawking held a champagne party (shown in his Discovery Channel program), but he only advertised it after it had happened. His reasoning was that, if time machines eventually become practical, someone in the future might read about the party and travel back to attend it. But no one did — Hawking sat through the whole evening on his own. This doesn't prove time travel is impossible, but it does suggest that it never becomes a commonplace occurrence here on Earth.

The arrow of time

One of the distinctive things about time is that it has a direction — from past to future. A cup of hot coffee left at room temperature always cools down; it never heats up. Your cellphone loses battery charge when you use it; it never gains charge. These are examples of entropy , essentially a measure of the amount of "useless" as opposed to "useful" energy. The entropy of a closed system always increases, and it's the key factor determining the arrow of time.

It turns out that entropy is the only thing that makes a distinction between past and future. In other branches of physics, like relativity or quantum theory, time doesn't have a preferred direction. No one knows where time's arrow comes from. It may be that it only applies to large, complex systems, in which case subatomic particles may not experience the arrow of time.

Time travel paradox

If it's possible to travel back into the past — even theoretically — it raises a number of brain-twisting paradoxes — such as the grandfather paradox — that even scientists and philosophers find extremely perplexing.

Killing Hitler

A time traveler might decide to go back and kill him in his infancy. If they succeeded, future history books wouldn't even mention Hitler — so what motivation would the time traveler have for going back in time and killing him?

Killing your grandfather

Instead of killing a young Hitler, you might, by accident, kill one of your own ancestors when they were very young. But then you would never be born, so you couldn't travel back in time to kill them, so you would be born after all, and so on …

A closed loop

Suppose the plans for a time machine suddenly appear from thin air on your desk. You spend a few days building it, then use it to send the plans back to your earlier self. But where did those plans originate? Nowhere — they are just looping round and round in time.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Andrew May holds a Ph.D. in astrophysics from Manchester University, U.K. For 30 years, he worked in the academic, government and private sectors, before becoming a science writer where he has written for Fortean Times, How It Works, All About Space, BBC Science Focus, among others. He has also written a selection of books including Cosmic Impact and Astrobiology: The Search for Life Elsewhere in the Universe, published by Icon Books.

Jupiter may be the reason why Earth has a moon, new study hints

Space photo of the week: Little Dumbbell Nebula throws a wild party for Hubble telescope's 34th anniversary

Earth from space: Lava bleeds down iguana-infested volcano as it spits out toxic gas

Most Popular

- 2 James Webb telescope confirms there is something seriously wrong with our understanding of the universe

- 3 'I nearly fell out of my chair': 1,800-year-old mini portrait of Alexander the Great found in a field in Denmark

- 4 Scientists discover once-in-a-billion-year event — 2 lifeforms merging to create a new cell part

- 5 DNA analysis spanning 9 generations of people reveals marriage practices of mysterious warrior culture

- 2 'Octagonal' sword from Bronze Age burial in Germany is so well preserved it shines

- 3 Haunting photo of Earth and moon snapped by China's experimental lunar satellites

- 4 Tweak to Schrödinger's cat equation could unite Einstein's relativity and quantum mechanics, study hints

- 5 Can humans see ultraviolet light?

Can we time travel? A theoretical physicist provides some answers

Emeritus professor, Physics, Carleton University

Disclosure statement

Peter Watson received funding from NSERC. He is affiliated with Carleton University and a member of the Canadian Association of Physicists.

Carleton University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA.

Carleton University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

View all partners

- Bahasa Indonesia

Time travel makes regular appearances in popular culture, with innumerable time travel storylines in movies, television and literature. But it is a surprisingly old idea: one can argue that the Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex , written by Sophocles over 2,500 years ago, is the first time travel story .

But is time travel in fact possible? Given the popularity of the concept, this is a legitimate question. As a theoretical physicist, I find that there are several possible answers to this question, not all of which are contradictory.

The simplest answer is that time travel cannot be possible because if it was, we would already be doing it. One can argue that it is forbidden by the laws of physics, like the second law of thermodynamics or relativity . There are also technical challenges: it might be possible but would involve vast amounts of energy.

There is also the matter of time-travel paradoxes; we can — hypothetically — resolve these if free will is an illusion, if many worlds exist or if the past can only be witnessed but not experienced. Perhaps time travel is impossible simply because time must flow in a linear manner and we have no control over it, or perhaps time is an illusion and time travel is irrelevant.

Laws of physics

Since Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity — which describes the nature of time, space and gravity — is our most profound theory of time, we would like to think that time travel is forbidden by relativity. Unfortunately, one of his colleagues from the Institute for Advanced Study, Kurt Gödel, invented a universe in which time travel was not just possible, but the past and future were inextricably tangled.

We can actually design time machines , but most of these (in principle) successful proposals require negative energy , or negative mass, which does not seem to exist in our universe. If you drop a tennis ball of negative mass, it will fall upwards. This argument is rather unsatisfactory, since it explains why we cannot time travel in practice only by involving another idea — that of negative energy or mass — that we do not really understand.

Mathematical physicist Frank Tipler conceptualized a time machine that does not involve negative mass, but requires more energy than exists in the universe .

Time travel also violates the second law of thermodynamics , which states that entropy or randomness must always increase. Time can only move in one direction — in other words, you cannot unscramble an egg. More specifically, by travelling into the past we are going from now (a high entropy state) into the past, which must have lower entropy.

This argument originated with the English cosmologist Arthur Eddington , and is at best incomplete. Perhaps it stops you travelling into the past, but it says nothing about time travel into the future. In practice, it is just as hard for me to travel to next Thursday as it is to travel to last Thursday.

Resolving paradoxes

There is no doubt that if we could time travel freely, we run into the paradoxes. The best known is the “ grandfather paradox ”: one could hypothetically use a time machine to travel to the past and murder their grandfather before their father’s conception, thereby eliminating the possibility of their own birth. Logically, you cannot both exist and not exist.

Read more: Time travel could be possible, but only with parallel timelines

Kurt Vonnegut’s anti-war novel Slaughterhouse-Five , published in 1969, describes how to evade the grandfather paradox. If free will simply does not exist, it is not possible to kill one’s grandfather in the past, since he was not killed in the past. The novel’s protagonist, Billy Pilgrim, can only travel to other points on his world line (the timeline he exists in), but not to any other point in space-time, so he could not even contemplate killing his grandfather.

The universe in Slaughterhouse-Five is consistent with everything we know. The second law of thermodynamics works perfectly well within it and there is no conflict with relativity. But it is inconsistent with some things we believe in, like free will — you can observe the past, like watching a movie, but you cannot interfere with the actions of people in it.

Could we allow for actual modifications of the past, so that we could go back and murder our grandfather — or Hitler ? There are several multiverse theories that suppose that there are many timelines for different universes. This is also an old idea: in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol , Ebeneezer Scrooge experiences two alternative timelines, one of which leads to a shameful death and the other to happiness.

Time is a river

Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius wrote that:

“ Time is like a river made up of the events which happen , and a violent stream; for as soon as a thing has been seen, it is carried away, and another comes in its place, and this will be carried away too.”

We can imagine that time does flow past every point in the universe, like a river around a rock. But it is difficult to make the idea precise. A flow is a rate of change — the flow of a river is the amount of water that passes a specific length in a given time. Hence if time is a flow, it is at the rate of one second per second, which is not a very useful insight.

Theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking suggested that a “ chronology protection conjecture ” must exist, an as-yet-unknown physical principle that forbids time travel. Hawking’s concept originates from the idea that we cannot know what goes on inside a black hole, because we cannot get information out of it. But this argument is redundant: we cannot time travel because we cannot time travel!

Researchers are investigating a more fundamental theory, where time and space “emerge” from something else. This is referred to as quantum gravity , but unfortunately it does not exist yet.

So is time travel possible? Probably not, but we don’t know for sure!

- Time travel

- Stephen Hawking

- Albert Einstein

- Listen to this article

- Time travel paradox

- Arthur Eddington

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Regional Engagement Officer - Shepparton

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

April 26, 2023

Is Time Travel Possible?

The laws of physics allow time travel. So why haven’t people become chronological hoppers?

By Sarah Scoles

yuanyuan yan/Getty Images

In the movies, time travelers typically step inside a machine and—poof—disappear. They then reappear instantaneously among cowboys, knights or dinosaurs. What these films show is basically time teleportation .

Scientists don’t think this conception is likely in the real world, but they also don’t relegate time travel to the crackpot realm. In fact, the laws of physics might allow chronological hopping, but the devil is in the details.

Time traveling to the near future is easy: you’re doing it right now at a rate of one second per second, and physicists say that rate can change. According to Einstein’s special theory of relativity, time’s flow depends on how fast you’re moving. The quicker you travel, the slower seconds pass. And according to Einstein’s general theory of relativity , gravity also affects clocks: the more forceful the gravity nearby, the slower time goes.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“Near massive bodies—near the surface of neutron stars or even at the surface of the Earth, although it’s a tiny effect—time runs slower than it does far away,” says Dave Goldberg, a cosmologist at Drexel University.

If a person were to hang out near the edge of a black hole , where gravity is prodigious, Goldberg says, only a few hours might pass for them while 1,000 years went by for someone on Earth. If the person who was near the black hole returned to this planet, they would have effectively traveled to the future. “That is a real effect,” he says. “That is completely uncontroversial.”

Going backward in time gets thorny, though (thornier than getting ripped to shreds inside a black hole). Scientists have come up with a few ways it might be possible, and they have been aware of time travel paradoxes in general relativity for decades. Fabio Costa, a physicist at the Nordic Institute for Theoretical Physics, notes that an early solution with time travel began with a scenario written in the 1920s. That idea involved massive long cylinder that spun fast in the manner of straw rolled between your palms and that twisted spacetime along with it. The understanding that this object could act as a time machine allowing one to travel to the past only happened in the 1970s, a few decades after scientists had discovered a phenomenon called “closed timelike curves.”

“A closed timelike curve describes the trajectory of a hypothetical observer that, while always traveling forward in time from their own perspective, at some point finds themselves at the same place and time where they started, creating a loop,” Costa says. “This is possible in a region of spacetime that, warped by gravity, loops into itself.”

“Einstein read [about closed timelike curves] and was very disturbed by this idea,” he adds. The phenomenon nevertheless spurred later research.

Science began to take time travel seriously in the 1980s. In 1990, for instance, Russian physicist Igor Novikov and American physicist Kip Thorne collaborated on a research paper about closed time-like curves. “They started to study not only how one could try to build a time machine but also how it would work,” Costa says.

Just as importantly, though, they investigated the problems with time travel. What if, for instance, you tossed a billiard ball into a time machine, and it traveled to the past and then collided with its past self in a way that meant its present self could never enter the time machine? “That looks like a paradox,” Costa says.

Since the 1990s, he says, there’s been on-and-off interest in the topic yet no big breakthrough. The field isn’t very active today, in part because every proposed model of a time machine has problems. “It has some attractive features, possibly some potential, but then when one starts to sort of unravel the details, there ends up being some kind of a roadblock,” says Gaurav Khanna of the University of Rhode Island.

For instance, most time travel models require negative mass —and hence negative energy because, as Albert Einstein revealed when he discovered E = mc 2 , mass and energy are one and the same. In theory, at least, just as an electric charge can be positive or negative, so can mass—though no one’s ever found an example of negative mass. Why does time travel depend on such exotic matter? In many cases, it is needed to hold open a wormhole—a tunnel in spacetime predicted by general relativity that connects one point in the cosmos to another.

Without negative mass, gravity would cause this tunnel to collapse. “You can think of it as counteracting the positive mass or energy that wants to traverse the wormhole,” Goldberg says.

Khanna and Goldberg concur that it’s unlikely matter with negative mass even exists, although Khanna notes that some quantum phenomena show promise, for instance, for negative energy on very small scales. But that would be “nowhere close to the scale that would be needed” for a realistic time machine, he says.

These challenges explain why Khanna initially discouraged Caroline Mallary, then his graduate student at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, from doing a time travel project. Mallary and Khanna went forward anyway and came up with a theoretical time machine that didn’t require negative mass. In its simplistic form, Mallary’s idea involves two parallel cars, each made of regular matter. If you leave one parked and zoom the other with extreme acceleration, a closed timelike curve will form between them.

Easy, right? But while Mallary’s model gets rid of the need for negative matter, it adds another hurdle: it requires infinite density inside the cars for them to affect spacetime in a way that would be useful for time travel. Infinite density can be found inside a black hole, where gravity is so intense that it squishes matter into a mind-bogglingly small space called a singularity. In the model, each of the cars needs to contain such a singularity. “One of the reasons that there's not a lot of active research on this sort of thing is because of these constraints,” Mallary says.

Other researchers have created models of time travel that involve a wormhole, or a tunnel in spacetime from one point in the cosmos to another. “It's sort of a shortcut through the universe,” Goldberg says. Imagine accelerating one end of the wormhole to near the speed of light and then sending it back to where it came from. “Those two sides are no longer synced,” he says. “One is in the past; one is in the future.” Walk between them, and you’re time traveling.

You could accomplish something similar by moving one end of the wormhole near a big gravitational field—such as a black hole—while keeping the other end near a smaller gravitational force. In that way, time would slow down on the big gravity side, essentially allowing a particle or some other chunk of mass to reside in the past relative to the other side of the wormhole.

Making a wormhole requires pesky negative mass and energy, however. A wormhole created from normal mass would collapse because of gravity. “Most designs tend to have some similar sorts of issues,” Goldberg says. They’re theoretically possible, but there’s currently no feasible way to make them, kind of like a good-tasting pizza with no calories.

And maybe the problem is not just that we don’t know how to make time travel machines but also that it’s not possible to do so except on microscopic scales—a belief held by the late physicist Stephen Hawking. He proposed the chronology protection conjecture: The universe doesn’t allow time travel because it doesn’t allow alterations to the past. “It seems there is a chronology protection agency, which prevents the appearance of closed timelike curves and so makes the universe safe for historians,” Hawking wrote in a 1992 paper in Physical Review D .

Part of his reasoning involved the paradoxes time travel would create such as the aforementioned situation with a billiard ball and its more famous counterpart, the grandfather paradox : If you go back in time and kill your grandfather before he has children, you can’t be born, and therefore you can’t time travel, and therefore you couldn’t have killed your grandfather. And yet there you are.

Those complications are what interests Massachusetts Institute of Technology philosopher Agustin Rayo, however, because the paradoxes don’t just call causality and chronology into question. They also make free will seem suspect. If physics says you can go back in time, then why can’t you kill your grandfather? “What stops you?” he says. Are you not free?

Rayo suspects that time travel is consistent with free will, though. “What’s past is past,” he says. “So if, in fact, my grandfather survived long enough to have children, traveling back in time isn’t going to change that. Why will I fail if I try? I don’t know because I don’t have enough information about the past. What I do know is that I’ll fail somehow.”

If you went to kill your grandfather, in other words, you’d perhaps slip on a banana en route or miss the bus. “It's not like you would find some special force compelling you not to do it,” Costa says. “You would fail to do it for perfectly mundane reasons.”

In 2020 Costa worked with Germain Tobar, then his undergraduate student at the University of Queensland in Australia, on the math that would underlie a similar idea: that time travel is possible without paradoxes and with freedom of choice.

Goldberg agrees with them in a way. “I definitely fall into the category of [thinking that] if there is time travel, it will be constructed in such a way that it produces one self-consistent view of history,” he says. “Because that seems to be the way that all the rest of our physical laws are constructed.”

No one knows what the future of time travel to the past will hold. And so far, no time travelers have come to tell us about it.

We have completed maintenance on Astronomy.com and action may be required on your account. Learn More

- Login/Register

- Solar System

- Exotic Objects

- Upcoming Events

- Deep-Sky Objects

- Observing Basics

- Telescopes and Equipment

- Astrophotography

- Space Exploration

- Human Spaceflight

- Robotic Spaceflight

- The Magazine

Is time travel possible? An astrophysicist explains

Will it ever be possible for time travel to occur? – Alana C., age 12, Queens, New York

Have you ever dreamed of traveling through time, like characters do in science fiction movies? For centuries, the concept of time travel has captivated people’s imaginations. Time travel is the concept of moving between different points in time, just like you move between different places. In movies, you might have seen characters using special machines, magical devices or even hopping into a futuristic car to travel backward or forward in time.

But is this just a fun idea for movies, or could it really happen?

The question of whether time is reversible remains one of the biggest unresolved questions in science. If the universe follows the laws of thermodynamics , it may not be possible. The second law of thermodynamics states that things in the universe can either remain the same or become more disordered over time.

It’s a bit like saying you can’t unscramble eggs once they’ve been cooked. According to this law, the universe can never go back exactly to how it was before. Time can only go forward, like a one-way street.

Time is relative

However, physicist Albert Einstein’s theory of special relativity suggests that time passes at different rates for different people. Someone speeding along on a spaceship moving close to the speed of light – 671 million miles per hour! – will experience time slower than a person on Earth.

Related: The speed of light, explained

People have yet to build spaceships that can move at speeds anywhere near as fast as light, but astronauts who visit the International Space Station orbit around the Earth at speeds close to 17,500 mph. Astronaut Scott Kelly has spent 520 days at the International Space Station, and as a result has aged a little more slowly than his twin brother – and fellow astronaut – Mark Kelly. Scott used to be 6 minutes younger than his twin brother. Now, because Scott was traveling so much faster than Mark and for so many days, he is 6 minutes and 5 milliseconds younger .

Some scientists are exploring other ideas that could theoretically allow time travel. One concept involves wormholes , or hypothetical tunnels in space that could create shortcuts for journeys across the universe. If someone could build a wormhole and then figure out a way to move one end at close to the speed of light – like the hypothetical spaceship mentioned above – the moving end would age more slowly than the stationary end. Someone who entered the moving end and exited the wormhole through the stationary end would come out in their past.

However, wormholes remain theoretical : Scientists have yet to spot one. It also looks like it would be incredibly challenging to send humans through a wormhole space tunnel.

Time travel paradoxes and failed dinner parties

There are also paradoxes associated with time travel. The famous “ grandfather paradox ” is a hypothetical problem that could arise if someone traveled back in time and accidentally prevented their grandparents from meeting. This would create a paradox where you were never born, which raises the question: How could you have traveled back in time in the first place? It’s a mind-boggling puzzle that adds to the mystery of time travel.

Famously, physicist Stephen Hawking tested the possibility of time travel by throwing a dinner party where invitations noting the date, time and coordinates were not sent out until after it had happened. His hope was that his invitation would be read by someone living in the future, who had capabilities to travel back in time. But no one showed up.

As he pointed out : “The best evidence we have that time travel is not possible, and never will be, is that we have not been invaded by hordes of tourists from the future.”

Telescopes are time machines

Interestingly, astrophysicists armed with powerful telescopes possess a unique form of time travel. As they peer into the vast expanse of the cosmos, they gaze into the past universe. Light from all galaxies and stars takes time to travel, and these beams of light carry information from the distant past. When astrophysicists observe a star or a galaxy through a telescope, they are not seeing it as it is in the present, but as it existed when the light began its journey to Earth millions to billions of years ago.

NASA’s newest space telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope , is peering at galaxies that were formed at the very beginning of the Big Bang, about 13.7 billion years ago.

While we aren’t likely to have time machines like the ones in movies anytime soon, scientists are actively researching and exploring new ideas. But for now, we’ll have to enjoy the idea of time travel in our favorite books, movies and dreams.

This article first appeared on the Conversation. You can read the original here .

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to [email protected] . Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

Planets on parade: This Week in Astronomy with Dave Eicher

2024 Full Moon calendar: Dates, times, types, and names

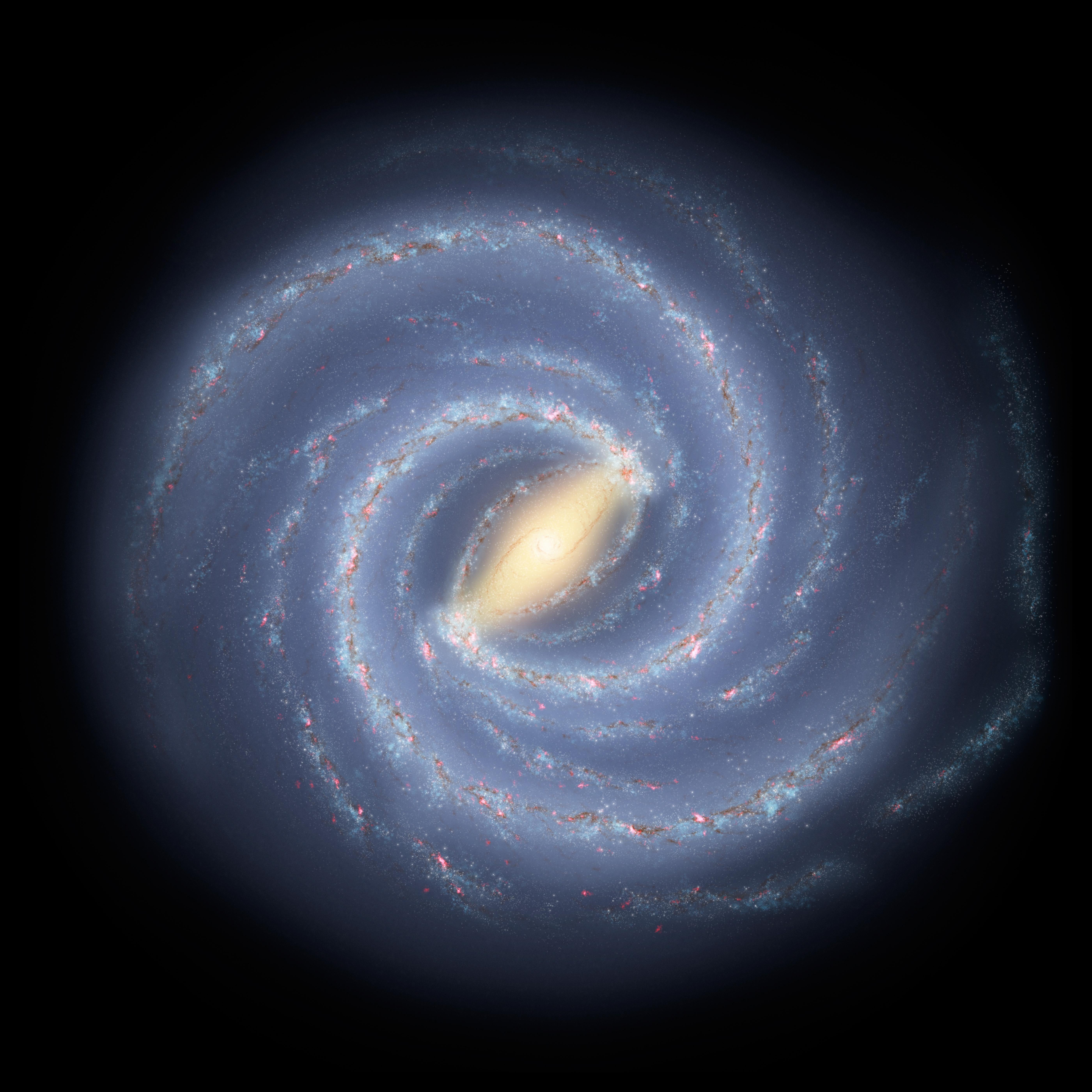

The Milky Way, to ancient Egyptians, was probably mixed Nuts

The reasons why numbers go on forever

Astronomy Magazine Annual Index

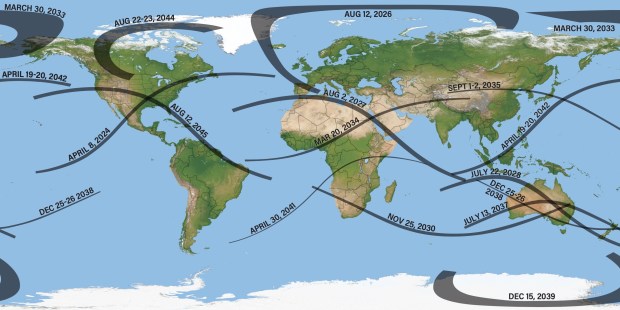

How to see the next 20 years of eclipses, including the eclipse of a lifetime

IceCube researchers detect a rare type of particle sent from powerful astronomical objects

A collision with something the size of Arizona could have formed half of Pluto’s ‘heart’

How many stars die in the Milky Way each year?

Time travel: Is it possible?

Science says time travel is possible, but probably not in the way you're thinking.

Albert Einstein's theory

- General relativity and GPS

- Wormhole travel

- Alternate theories

Science fiction

Is time travel possible? Short answer: Yes, and you're doing it right now — hurtling into the future at the impressive rate of one second per second.

You're pretty much always moving through time at the same speed, whether you're watching paint dry or wishing you had more hours to visit with a friend from out of town.

But this isn't the kind of time travel that's captivated countless science fiction writers, or spurred a genre so extensive that Wikipedia lists over 400 titles in the category "Movies about Time Travel." In franchises like " Doctor Who ," " Star Trek ," and "Back to the Future" characters climb into some wild vehicle to blast into the past or spin into the future. Once the characters have traveled through time, they grapple with what happens if you change the past or present based on information from the future (which is where time travel stories intersect with the idea of parallel universes or alternate timelines).

Related: The best sci-fi time machines ever

Although many people are fascinated by the idea of changing the past or seeing the future before it's due, no person has ever demonstrated the kind of back-and-forth time travel seen in science fiction or proposed a method of sending a person through significant periods of time that wouldn't destroy them on the way. And, as physicist Stephen Hawking pointed out in his book " Black Holes and Baby Universes" (Bantam, 1994), "The best evidence we have that time travel is not possible, and never will be, is that we have not been invaded by hordes of tourists from the future."

Science does support some amount of time-bending, though. For example, physicist Albert Einstein 's theory of special relativity proposes that time is an illusion that moves relative to an observer. An observer traveling near the speed of light will experience time, with all its aftereffects (boredom, aging, etc.) much more slowly than an observer at rest. That's why astronaut Scott Kelly aged ever so slightly less over the course of a year in orbit than his twin brother who stayed here on Earth.

Related: Controversially, physicist argues that time is real

There are other scientific theories about time travel, including some weird physics that arise around wormholes , black holes and string theory . For the most part, though, time travel remains the domain of an ever-growing array of science fiction books, movies, television shows, comics, video games and more.

Einstein developed his theory of special relativity in 1905. Along with his later expansion, the theory of general relativity , it has become one of the foundational tenets of modern physics. Special relativity describes the relationship between space and time for objects moving at constant speeds in a straight line.

The short version of the theory is deceptively simple. First, all things are measured in relation to something else — that is to say, there is no "absolute" frame of reference. Second, the speed of light is constant. It stays the same no matter what, and no matter where it's measured from. And third, nothing can go faster than the speed of light.

From those simple tenets unfolds actual, real-life time travel. An observer traveling at high velocity will experience time at a slower rate than an observer who isn't speeding through space.

While we don't accelerate humans to near-light-speed, we do send them swinging around the planet at 17,500 mph (28,160 km/h) aboard the International Space Station . Astronaut Scott Kelly was born after his twin brother, and fellow astronaut, Mark Kelly . Scott Kelly spent 520 days in orbit, while Mark logged 54 days in space. The difference in the speed at which they experienced time over the course of their lifetimes has actually widened the age gap between the two men.

"So, where[as] I used to be just 6 minutes older, now I am 6 minutes and 5 milliseconds older," Mark Kelly said in a panel discussion on July 12, 2020, Space.com previously reported . "Now I've got that over his head."

General relativity and GPS time travel

The difference that low earth orbit makes in an astronaut's life span may be negligible — better suited for jokes among siblings than actual life extension or visiting the distant future — but the dilation in time between people on Earth and GPS satellites flying through space does make a difference.

Read more: Can we stop time?

The Global Positioning System , or GPS, helps us know exactly where we are by communicating with a network of a few dozen satellites positioned in a high Earth orbit. The satellites circle the planet from 12,500 miles (20,100 kilometers) away, moving at 8,700 mph (14,000 km/h).

According to special relativity, the faster an object moves relative to another object, the slower that first object experiences time. For GPS satellites with atomic clocks, this effect cuts 7 microseconds, or 7 millionths of a second, off each day, according to the American Physical Society publication Physics Central .

Read more: Could Star Trek's faster-than-light warp drive actually work?

Then, according to general relativity, clocks closer to the center of a large gravitational mass like Earth tick more slowly than those farther away. So, because the GPS satellites are much farther from the center of Earth compared to clocks on the surface, Physics Central added, that adds another 45 microseconds onto the GPS satellite clocks each day. Combined with the negative 7 microseconds from the special relativity calculation, the net result is an added 38 microseconds.

This means that in order to maintain the accuracy needed to pinpoint your car or phone — or, since the system is run by the U.S. Department of Defense, a military drone — engineers must account for an extra 38 microseconds in each satellite's day. The atomic clocks onboard don’t tick over to the next day until they have run 38 microseconds longer than comparable clocks on Earth.

Given those numbers, it would take more than seven years for the atomic clock in a GPS satellite to un-sync itself from an Earth clock by more than a blink of an eye. (We did the math: If you estimate a blink to last at least 100,000 microseconds, as the Harvard Database of Useful Biological Numbers does, it would take thousands of days for those 38 microsecond shifts to add up.)

This kind of time travel may seem as negligible as the Kelly brothers' age gap, but given the hyper-accuracy of modern GPS technology, it actually does matter. If it can communicate with the satellites whizzing overhead, your phone can nail down your location in space and time with incredible accuracy.

Can wormholes take us back in time?

General relativity might also provide scenarios that could allow travelers to go back in time, according to NASA . But the physical reality of those time-travel methods is no piece of cake.

Wormholes are theoretical "tunnels" through the fabric of space-time that could connect different moments or locations in reality to others. Also known as Einstein-Rosen bridges or white holes, as opposed to black holes, speculation about wormholes abounds. But despite taking up a lot of space (or space-time) in science fiction, no wormholes of any kind have been identified in real life.

Related: Best time travel movies

"The whole thing is very hypothetical at this point," Stephen Hsu, a professor of theoretical physics at the University of Oregon, told Space.com sister site Live Science . "No one thinks we're going to find a wormhole anytime soon."

Primordial wormholes are predicted to be just 10^-34 inches (10^-33 centimeters) at the tunnel's "mouth". Previously, they were expected to be too unstable for anything to be able to travel through them. However, a study claims that this is not the case, Live Science reported .

The theory, which suggests that wormholes could work as viable space-time shortcuts, was described by physicist Pascal Koiran. As part of the study, Koiran used the Eddington-Finkelstein metric, as opposed to the Schwarzschild metric which has been used in the majority of previous analyses.

In the past, the path of a particle could not be traced through a hypothetical wormhole. However, using the Eddington-Finkelstein metric, the physicist was able to achieve just that.

Koiran's paper was described in October 2021, in the preprint database arXiv , before being published in the Journal of Modern Physics D.

Alternate time travel theories

While Einstein's theories appear to make time travel difficult, some researchers have proposed other solutions that could allow jumps back and forth in time. These alternate theories share one major flaw: As far as scientists can tell, there's no way a person could survive the kind of gravitational pulling and pushing that each solution requires.

Infinite cylinder theory

Astronomer Frank Tipler proposed a mechanism (sometimes known as a Tipler Cylinder ) where one could take matter that is 10 times the sun's mass, then roll it into a very long, but very dense cylinder. The Anderson Institute , a time travel research organization, described the cylinder as "a black hole that has passed through a spaghetti factory."

After spinning this black hole spaghetti a few billion revolutions per minute, a spaceship nearby — following a very precise spiral around the cylinder — could travel backward in time on a "closed, time-like curve," according to the Anderson Institute.

The major problem is that in order for the Tipler Cylinder to become reality, the cylinder would need to be infinitely long or be made of some unknown kind of matter. At least for the foreseeable future, endless interstellar pasta is beyond our reach.

Time donuts

Theoretical physicist Amos Ori at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, Israel, proposed a model for a time machine made out of curved space-time — a donut-shaped vacuum surrounded by a sphere of normal matter.

"The machine is space-time itself," Ori told Live Science . "If we were to create an area with a warp like this in space that would enable time lines to close on themselves, it might enable future generations to return to visit our time."

Amos Ori is a theoretical physicist at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, Israel. His research interests and publications span the fields of general relativity, black holes, gravitational waves and closed time lines.

There are a few caveats to Ori's time machine. First, visitors to the past wouldn't be able to travel to times earlier than the invention and construction of the time donut. Second, and more importantly, the invention and construction of this machine would depend on our ability to manipulate gravitational fields at will — a feat that may be theoretically possible but is certainly beyond our immediate reach.

Time travel has long occupied a significant place in fiction. Since as early as the "Mahabharata," an ancient Sanskrit epic poem compiled around 400 B.C., humans have dreamed of warping time, Lisa Yaszek, a professor of science fiction studies at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, told Live Science .

Every work of time-travel fiction creates its own version of space-time, glossing over one or more scientific hurdles and paradoxes to achieve its plot requirements.

Some make a nod to research and physics, like " Interstellar ," a 2014 film directed by Christopher Nolan. In the movie, a character played by Matthew McConaughey spends a few hours on a planet orbiting a supermassive black hole, but because of time dilation, observers on Earth experience those hours as a matter of decades.

Others take a more whimsical approach, like the "Doctor Who" television series. The series features the Doctor, an extraterrestrial "Time Lord" who travels in a spaceship resembling a blue British police box. "People assume," the Doctor explained in the show, "that time is a strict progression from cause to effect, but actually from a non-linear, non-subjective viewpoint, it's more like a big ball of wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey stuff."

Long-standing franchises like the "Star Trek" movies and television series, as well as comic universes like DC and Marvel Comics, revisit the idea of time travel over and over.

Related: Marvel movies in order: chronological & release order

Here is an incomplete (and deeply subjective) list of some influential or notable works of time travel fiction:

Books about time travel:

- Rip Van Winkle (Cornelius S. Van Winkle, 1819) by Washington Irving

- A Christmas Carol (Chapman & Hall, 1843) by Charles Dickens

- The Time Machine (William Heinemann, 1895) by H. G. Wells

- A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Charles L. Webster and Co., 1889) by Mark Twain

- The Restaurant at the End of the Universe (Pan Books, 1980) by Douglas Adams

- A Tale of Time City (Methuen, 1987) by Diana Wynn Jones

- The Outlander series (Delacorte Press, 1991-present) by Diana Gabaldon

- Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Bloomsbury/Scholastic, 1999) by J. K. Rowling

- Thief of Time (Doubleday, 2001) by Terry Pratchett

- The Time Traveler's Wife (MacAdam/Cage, 2003) by Audrey Niffenegger

- All You Need is Kill (Shueisha, 2004) by Hiroshi Sakurazaka

Movies about time travel:

- Planet of the Apes (1968)

- Superman (1978)

- Time Bandits (1981)

- The Terminator (1984)

- Back to the Future series (1985, 1989, 1990)

- Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986)

- Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure (1989)

- Groundhog Day (1993)

- Galaxy Quest (1999)

- The Butterfly Effect (2004)

- 13 Going on 30 (2004)

- The Lake House (2006)

- Meet the Robinsons (2007)

- Hot Tub Time Machine (2010)

- Midnight in Paris (2011)

- Looper (2012)

- X-Men: Days of Future Past (2014)

- Edge of Tomorrow (2014)

- Interstellar (2014)

- Doctor Strange (2016)

- A Wrinkle in Time (2018)

- The Last Sharknado: It's About Time (2018)

- Avengers: Endgame (2019)

- Tenet (2020)

- Palm Springs (2020)

- Zach Snyder's Justice League (2021)

- The Tomorrow War (2021)

Television about time travel:

- Doctor Who (1963-present)

- The Twilight Zone (1959-1964) (multiple episodes)

- Star Trek (multiple series, multiple episodes)

- Samurai Jack (2001-2004)

- Lost (2004-2010)

- Phil of the Future (2004-2006)

- Steins;Gate (2011)

- Outlander (2014-2023)

- Loki (2021-present)

Games about time travel:

- Chrono Trigger (1995)

- TimeSplitters (2000-2005)

- Kingdom Hearts (2002-2019)

- Prince of Persia: Sands of Time (2003)

- God of War II (2007)

- Ratchet and Clank Future: A Crack In Time (2009)

- Sly Cooper: Thieves in Time (2013)

- Dishonored 2 (2016)

- Titanfall 2 (2016)

- Outer Wilds (2019)

Additional resources

Explore physicist Peter Millington's thoughts about Stephen Hawking's time travel theories at The Conversation . Check out a kid-friendly explanation of real-world time travel from NASA's Space Place . For an overview of time travel in fiction and the collective consciousness, read " Time Travel: A History " (Pantheon, 2016) by James Gleik.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Ailsa is a staff writer for How It Works magazine, where she writes science, technology, space, history and environment features. Based in the U.K., she graduated from the University of Stirling with a BA (Hons) journalism degree. Previously, Ailsa has written for Cardiff Times magazine, Psychology Now and numerous science bookazines.

Satellites watch as 4th global coral bleaching event unfolds (image)

Happy Earth Day 2024! NASA picks 6 new airborne missions to study our changing planet

Boeing's Starliner spacecraft will not fly private missions yet, officials say

Most Popular

- 2 SpaceX launching Falcon 9 rocket on record-tying 20th mission today

- 3 Watch 2 gorgeous supernova remnants evolve over 20 years (timelapse video)

- 4 Boeing Starliner 1st astronaut flight: Live updates

- 5 US Space Force picks Rocket Lab for 2025 Victus Haze space domain awareness mission

Einstein's equation and time travel

How is Einstein's equation (Gμν = 8πG Tμν) actually applied? And how does it support the theory of time travel.

Many physicists refer to this as Einstein’s Equations (plural) because it's actually a set of several equations. The symbol Gμν denotes the "Einstein tensor," which is a measure of how much space-time is curving. The symbol Tμν denotes the "energy momentum tensor," which measures the density and flux of the energy and momentum of matter. The energy and momentum of matter causes space-time to curve in a way that is described by Einstein’s Equations. The curvature of space-time is what causes all the effects that we associate with "gravity."

There are many textbooks that explain how to apply Einstein’s Equations equations to various situations, but they require a very advanced background in physics and mathematics. I will therefore have to summarize things in words.

Before talking about time travel, let me first explain what a "world-line" is. Suppose that an object at a particular time is sitting at some particular point in space. At another time, it will be sitting at another point. Its locations at different times trace out a path through space-time, which is called the object’s world line. This path extends forward to points farther and farther in the future (until the object ceases to exist for some reason, at which point its world-line ends). But imagine that an object’s world-line bends around in a loop, so that at it arrives at a point in space-time where it had already been? For example, there may be a point on my world line that was me at my fifth birthday party at my parents’ home in New York City. Another point (farther along my world-line) is me now, aged 61, sitting in my office at the University of Delaware. If I continue farther and farther along my world line, might I end up again at my fifth birthday party in New York City in 1958? Could my five-year old self meet my much older self at that party? That is what most people mean by "time travel." In the jargon of physics, such a world line that bent around and intersected itself is called a "closed time-like loop" or "closed time-like curve."

The question is whether world-lines that are closed time-like loops are possible in the real world. It is comparatively easy to show that if space-time were not curved world-lines would definitely not be able to bend around to form closed time-like loops. But one might hope that gravity, by curving space-time, could bend some world-lines around to make closed loops. The way people have studied this question is to assume that Einstein’s equations correctly describe how the energy and momentum of matter curves space-time. Then they look for solutions of those equations where space-time curves in such a way as to make closed time-like loops possible, and therefore time-travel possible. No one has ever found such solutions. People have on occasion found what seemed to be such solutions, but on closer inspection it was found that when realistic conditions are imposed, no time travel is possible. An example is the Gödel Universe (or Gödel metric).

One kind of solution that would allow time travel is called a "Minkowski wormhole." A Minkowski wormhole would be like a tunnel that took you from one point in space-time to what seemed like a far distant point--a point far away in space, or in the past, or in the future. But people have shown that for a Minkowski wormhole to exist, there would have to be a type of matter whose energy and momentum were unlike any kind of matter ever seen and extremely unlikely to exist in the real world.

The great majority of experts believe that time travel is not allowed by the laws of physics. But no one has proved that rigorously. If you want to learn more, you could try to find discussions of closed time-like loops and Minkowski wormholes in books or on the internet.

-Stephen Barr

- General relativity

Navigation menu

Page actions.

- View source

Personal tools

- Recent changes

- Random page

- Help about MediaWiki

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Printable version

- Permanent link

- Page information

- This page was last edited on 18 May 2015, at 21:41.

- Privacy policy

- Disclaimers

Is Time Travel Possible?

- Cosmology & Astrophysics

- Physics Laws, Concepts, and Principles

- Quantum Physics

- Important Physicists

- Thermodynamics

- Weather & Climate

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/AZJFaceShot-56a72b155f9b58b7d0e783fa.jpg)

- M.S., Mathematics Education, Indiana University

- B.A., Physics, Wabash College

Stories regarding travel into the past and the future have long captured our imagination, but the question of whether time travel is possible is a thorny one that gets right to the heart of understanding what physicists mean when they use the word "time."

Modern physics teaches us that time is one of the most mysterious aspects of our universe, though it may at first seem straightforward. Einstein revolutionized our understanding of the concept, but even with this revised understanding, some scientists still ponder the question of whether or not time actually exists or whether it is a mere "stubbornly persistent illusion" (as Einstein once called it). Whatever time is, though, physicists (and fiction writers) have found some interesting ways to manipulate it to consider traversing it in unorthodox ways.

Time and Relativity

Though referenced in H.G. Wells' The Time Machine (1895), the actual science of time travel didn't come into being until well into the twentieth century, as a side-effect of Albert Einstein 's theory of general relativity (developed in 1915). Relativity describes the physical fabric of the universe in terms of a 4-dimensional spacetime, which includes three spatial dimensions (up/down, left/right, and front/back) along with one time dimension. Under this theory, which has been proven by numerous experiments over the last century, gravity is a result of the bending of this spacetime in response to the presence of matter. In other words, given a certain configuration of matter, the actual spacetime fabric of the universe can be altered in significant ways.

One of the amazing consequences of relativity is that movement can result in a difference in the way time passes, a process known as time dilation . This is most dramatically manifested in the classic Twin Paradox . In this method of "time travel," you can move into the future faster than normal, but there's not really any way back. (There's a slight exception, but more on that later in the article.)

Early Time Travel

In 1937, Scottish physicist W. J. van Stockum first applied general relativity in a way that opened the door for time travel. By applying the equation of general relativity to a situation with an infinitely long, extremely dense rotating cylinder (kind of like an endless barbershop pole). The rotation of such a massive object actually creates a phenomenon known as "frame dragging," which is that it actually drags spacetime along with it. Van Stockum found that in this situation, you could create a path in 4-dimensional spacetime which began and ended at the same point - something called a closed timelike curve - which is the physical result that allows time travel. You can set off in a space ship and travel a path which brings you back to the exact same moment you started out at.

Though an intriguing result, this was a fairly contrived situation, so there wasn't really much concern about it taking place. A new interpretation was about to come along, however, which was much more controversial.

In 1949, the mathematician Kurt Godel - a friend of Einstein's and a colleague at Princeton University's Institute for Advanced Study - decided to tackle a situation where the whole universe is rotating. In Godel's solutions, time travel was actually allowed by the equations if the universe were rotating. A rotating universe could itself function as a time machine.

Now, if the universe were rotating, there would be ways to detect it (light beams would bend, for example, if the whole universe were rotating), and so far the evidence is overwhelmingly strong that there is no sort of universal rotation. So again, time travel is ruled out by this particular set of results. But the fact is that things in the universe do rotate, and that again opens up the possibility.

Time Travel and Black Holes

In 1963, New Zealand mathematician Roy Kerr used the field equations to analyze a rotating black hole , called a Kerr black hole, and found that the results allowed a path through a wormhole in the black hole, missing the singularity at the center, and make it out the other end. This scenario also allows for closed timelike curves, as theoretical physicist Kip Thorne realized years later.

In the early 1980s, while Carl Sagan worked on his 1985 novel Contact , he approached Kip Thorne with a question about the physics of time travel, which inspired Thorne to examine the concept of using a black hole as a means of time travel. Together with the physicist Sung-Won Kim, Thorne realized that you could (in theory) have a black hole with a wormhole connecting it to another point in space held open by some form of negative energy.

But just because you have a wormhole doesn't mean that you have a time machine. Now, let's assume that you could move one end of the wormhole (the "movable end). You place the movable end on a spaceship, shooting it off into space at nearly the speed of light . Time dilation kicks in, and the time experienced by the movable end is much less than the time experienced by the fixed end. Let's assume that you move the movable end 5,000 years into the future of the Earth, but the movable end only "ages" 5 years. So you leave in 2010 AD, say, and arrive in 7010 AD.

However, if you travel through the movable end, you will actually pop out of the fixed end in 2015 AD (since 5 years have passed back on Earth). What? How does this work?

Well, the fact is that the two ends of the wormhole are connected. No matter how far apart they are, in spacetime, they're still basically "near" each other. Since the movable end is only five years older than when it left, going through it will send you back to the related point on the fixed wormhole. And if someone from 2015 AD Earth steps through the fixed wormhole, they'd come out in 7010 AD from the movable wormhole. (If someone stepped through the wormhole in 2012 AD, they'd end up on the spaceship somewhere in the middle of the trip and so on.)

Though this is the most physically reasonable description of a time machine, there are still problems. No one knows if wormholes or negative energy exist, nor how to put them together in this way if they do exist. But it is (in theory) possible.

- Can We Travel Through Time to the Past?

- Closed Timelike Curve

- Wormholes: What Are They and Can We Use Them?

- What Is the Twin Paradox? Real Time Travel

- Time Travel: Dream or Possible Reality?

- Einstein's Theory of Relativity

- The Science of Star Trek

- What Is Time? A Simple Explanation

- Understanding Time Dilation Effects in Physics

- Is Warp Drive From 'Star Trek' Possible?

- Understanding Cosmology and Its Impact

- An Introduction to Black Holes

- Cosmos Episode 4 Viewing Worksheet

- The History of Gravity

- Spiral Galaxies

- Black Holes and Hawking Radiation

Time Travel

Arguably, we are always travelling though time, as we move from the past into the future. But time travel usually refers to the possibility of changing the rate at which we travel into the future, or completely reversing it so that we travel into the past. Although a plot device in fiction since the 19 th Century (see the section on Time in Literature ), time travel has never been practically demonstrated or verified, and may still be impossible.

Time travel is not possible in Newtonian absolute time (we move deterministically and linearly forward into the future). Neither is it possible according to special relativity (we are constrained by our light cones). But general relativity does raises the prospect (at least theoretically) of travel through time, i.e. the possibility of movement backwards and/or forwards in time, independently of the normal flow of time we observe on Earth, in much the same way as we can move between different points in space.

Time travel is usually taken to mean that a person’s mind and body remain unchanged, with their memories intact, while their location in time is changed. If the traveller’s body and mind reverted its condition at the destination time, then no time travel would be perceptible.

Time Travel Scenarios

Although, in the main, differing fundamentally from the H.G. Wells concept of a physical machine with levers and dials, many different speculative time travel solutions and scenarios have been put forward over the years. However, the actual physical plausibility of these solutions in the real world remains uncertain.

At its simplest, as we have seen in the section on Relativistic Time , if one were to travel from the Earth at relativistic speeds and then return, then more time would have passed on Earth than for the traveller, so the traveller would, from his perspective, effectively have “travelled into the future”. This is not to say that the traveller suddenly jumped into the Earth’s future, in the way that time travel is often envisioned, but that, as judged by the Earth’s external time, the traveller has experienced less passage of time than his twin who remained on Earth. This is not real time travel, though, but more in the nature of “fast-forwarding” through time: it is a one-way journey forwards with no way back.

There does, however, appear to be some scientific basis within the Theory of Relativity for the possibility of real time travel in certain scenarios. Kurt Gödel showed, back in the early days of relativity, that there are some solutions to the field equations of general relativity that describe space-times so warped that they contain “ closed time-like curves ”, where an individual time-cone twists and closes in on itself, allowing a path from the present to the distant future or the past. Gödel’s solution was the first challenge in centuries to the dominant idea of linear time on which most of physics rests. Although a special case solution, based on an infinite, rotating universe (not the finite, non-rotating universe we actually find ourselves in), other time travel solution have been identified since then that do not require an infinite, rotating universe, but they remain contentious.

In the 1970s, controversial physicist Frank Tipler published his ideas for a “time machine”, using an infinitely long cylinder which spins along its longitudinal axis, which he claimed would allow time travel both forwards and backwards in time without violating the laws of physics, although Stephen Hawking later disproved Tipler’s ideas.

In 1994, Miguel Alcubierre proposed a hypothetical system whereby a spacecraft would contract space in front of it and expand space behind it, resulting in effective faster-than-light travel and therefore (potentially) time travel, but again the practicalities of constructing this kind of a “ warp drive ” remain prohibitive.

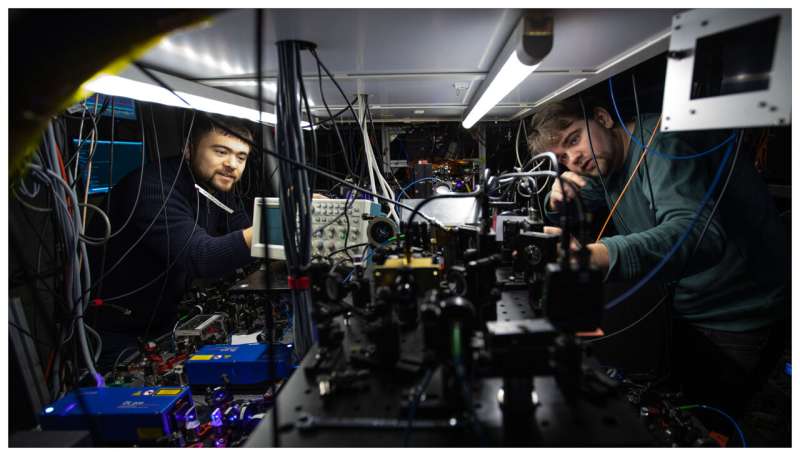

Other theoretical physicists like Kip Thorne and Paul Davies have shown how a wormhole in space-time could theoretically provide an instantaneous gateway to different time periods, in much the same way as general relativity allows the theoretical possibility of instantaneous spatial travel through wormholes. Wormholes are tubes or conduits or short-cuts through space-time, where space-time is so warped that it bends back on itself, another science fiction concept made potential reality by the Theory of Relativity. The drawback is that unimaginable amounts of energy would be required to bring about such a wormhole, although experiments looking into the possibility of creating mini-wormholes and mini-black holes are being carried out at the particle accelerator at CERN in Switzerland. It also seems likely that such a wormhole would collapse instantly into a black hole unless some method of holding it open were devised (possibly so-called “negative energy”, which is known to be theoretically possible, but which is not yet practically feasible). Stephen Hawking has suggested that radiation feedback, analogous to feedback in sound, would destroy the wormhole, which would therefore not last long enough to be used as a time machine. Actually controlling where (and when) a wormhole exits is another pitfall.

Another potential time travel possibility, although admittedly something of a long shot, relates to cosmic strings (or quantum strings ), long shreds of energy left over after the Big Bang, thinner than an atom but incredibly dense, that weave through the entire universe. Richard Gott has suggested that if two such cosmic strings were to pass close to each other, or even close to a black hole, the resulting warpage of space-time could well be so severe as to create a closed-time-like curve. However, cosmic strings remain speculative and the chances of finding such a phenomenon are vanishingly small (and, even if it were possible, such a loop may well find itself trapped inside a rotating black hole).

Physicist Ron Mallet has been looking into the possibility of using lasers to control extreme levels of gravity, which could then potentially be used to control time. According to Mallet, circulating beams of laser-controlled light could create similar conditions to a rotating black hole, with its frame-dragging and potential time travel properties.

Others are looking to quantum mechanics for a solution to time travel. In quantum physics, proven concepts such as superposition and entanglement effectively mean that a particle can be in two (or more) places at once. One interpretation of this (see the section on Quantum Time ) is the “ many worlds ” view in which all the different quantum states exist simultaneously in multiple parallel universes within an overall multiverse. If we could gain access to these alternative parallel universes, a form of time travel might then be possible.

At the sub-sub-microscopic level – at the level of so-called quantum foam , tiny bubbles of matter a billion-trillion-trillionths of a centimetre in length, perpetually popping into and out of existence – it is speculated that tiny tunnels or short-cuts through space-time are constantly forming, disappearing and reforming. Some scientists believe that it may be possible to capture such a quantum tunnel and enlarge it many trillions of times to the human scale. However, the idea is still at a very speculative stage,

It should be noted that, with all of these schemes and ideas, it does not look to be possible to travel any further back in time that the time at which the travel technology was devised.

Faster-Than-Light Particles

The equations of relativity imply that faster-than-light ( superluminal ) particles, if they existed, would theoretically travel backwards in time. Therefore, they could, again theoretically, be used to build a kind of “ antitelephone ” to send signals faster than light, and thus communicate backwards in time. Although the Theory of Relativity disallows particles from accelerating from sub-light speed to the speed of light (among other effects, time would slow right down and effectively stop for such a particle, and its mass would increase to infinity), it does not preclude the possibility of particles that ALWAYS travel faster than light. Therefore, the possibility does still exist in theory for faster-than-light travel in the case of a particle with such properties.

There is a rather strange theoretical particle in physics called the tachyon that routinely travels faster than light, with the corollary that such a particle would naturally travel backwards in time as we know it. So, in theory, one could never see such a particle approaching, only leaving, and the particle could even violate the normal order of cause and effect. For a tachyon, the speed of light is the lower speed limit, while the upper speed limit is infinity, and its speed increases as its energy decreases. Even stranger, the mass of a tachyon would technically be an imaginary number (i.e. the number squared is negative), whatever that might actually mean in practice.

It should be stressed that there is no experimental evidence to suggests that tachyons actually exist, and many physicists deny even the possibility. A tachyon has never been observed or recorded (although the search continues, particularly through analysis of cosmic rays and in particle accelerators), and neither has one ever been created, so they remain hypothetical, although theory strongly supports their existence.

Research using MINOS and OPERA detectors has suggested that tiny particles called neutrinos may travel faster than light. Other more recent research from CERN, however, has put the findings into dispute, and the matter remains inconclusive. Neutrinos are not merely hypothetical particles like tachyons, but a well-known part of modern particle physics. But they are tiny, almost-massless, invisible, electrically neutral, weakly-interacting particles that pass right through normal matter, and consequently are very difficult to measure and deal with (even their mass has never been measured accurately).

Time Travel Paradoxes

The possibility of travel backwards in time is generally considered by scientists to be much more unlikely than travel into the future. The idea of time travel to the past is rife with problems, not least the possibility of temporal paradoxes resulting from the violation of causality (i.e. the possibility that an effect could somehow precede its cause). This is most famously exemplified by the grandfather paradox : if a hypothetical time traveller goes back in time and kills his grandfather, the time traveller himself would never be born when he was meant to be; if he is never born, though, he is unable to travel through time and kill his grandfather, which means that he WOULD be born; etc, etc.

Some have sought to justify the possibility of time travel to the past by the very fact that such paradoxes never actually arise in practice. For example, the simple fact that the time traveller DOES exist at the start of his journey is itself proof that he could not kill his grandfather or change the past in any way, either because free will ceases to exist in the past, or because the outcomes of such decisions are predetermined. Or, alternatively, it is argued, any changes made by a hypothetical future time traveller must already have happened in the traveller’s past, resulting in the same reality that the traveller moves from.

Theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking has suggested that the fundamental laws of nature themselves – particularly the idea that causes always precede effects – may prevent time travel in some way. The apparent absence of “tourists from the future” here in our present is another argument, albeit not a rigorous one, that has been put forward against the possibility of time travel, even in a technologically advanced future (the assumption here is that future civilizations, millions of years more technologically advanced than us, should be capable of travel).