- The Magazine

- Stay Curious

- The Sciences

- Environment

- Planet Earth

A Century Ago, Einstein’s First Trip to the U.S. Ended in a PR Disaster

The scientist insulted americans in a newspaper interview, requiring a hasty apology tour..

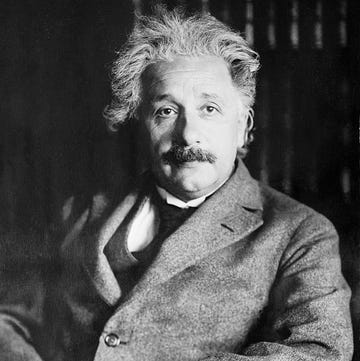

One hundred years ago, Albert Einstein first stepped foot in the United States. The journey served as a fundraising tour for a new Hebrew University in Jerusalem and an opportunity to lecture at some of America’s most prestigious academic institutions. It was also the moment Einstein established himself as a bona fide "celebrity scientist” in the English-speaking world — until a disastrous interview nearly unraveled the whole thing.

On April 3, 1921, the physicist arrived in New York Harbor to handkerchief-waving fans and throngs of photographers. He’d shot to fame a year and a half before when he demonstrated that the sun does in fact deflect starlight and bend light, verifying one of the classic tests of his Theory of Relativity and sending shockwaves through the scientific community. Einstein was now the most famous scientist in the world, both for his research and his personal quirks.

“They’re focusing on his wild and wooly hair and that he plays the violin and has the pipe, and those personable touches that get lots of people interested,” says Trevor Lipscombe, director of Catholic University of America Press and author of Albert Einstein: A Biography.

Chaim Weizmann, president of the World Zionist Organization, had organized the trip and persuaded the celebrated Jewish scientist to help draw attention (and donations) to establishing a Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Though not a practicing Jew and a self-identified non-Zionist, the cause of the University mattered to Einstein because he felt concerned by growing anti-Semitism and the limits on Jewish people’s access to universities throughout Europe. In fact, it was an important enough trip that he opted out of attending the third Solvay Conference on Physics, a major gathering of European scientists.

“The organizers thought that with Einstein being a fellow non-Zionist, he could draw support from other non-Zionists,” says Ze'ev Rosenkranz, assistant director and senior editor of the Einstein Papers Project at California Institute of Technology.

Einstein was received warmly at a string of charity dinners, ticker-tape parades and a meeting with President Warren G. Harding . Throughout, the physicist diligently spoke in favor of the need for a Hebrew University in Jerusalem, raising more than a quarter-million dollars toward that goal.

He also gave a series of talks at Harvard, Columbia, the City College of New York and elsewhere. Most celebrated was a series of four lectures at Princeton University, where he laid out his Theory of Relativity more fully than ever before.

While broadly a success, the tour exhausted Einstein. A natural introvert who spoke primarily in German, he often found himself overwhelmed by the attention from the press and public. While he expressed excitement about the trip, the scientist privately bristled at being “shown around like a prize ox” and said he was relieved when he boarded the Celtic ship to return to Europe.

An Unfortunate Interview

Einstein’s relief after returning home may have led the otherwise cautious scientist to let his guard down. At the beginning of July, Einstein agreed to an interview with Nell Boni, a young Berlin correspondent for the Dutch newspaper Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant (who was also a family acquaintance). “He basically thought he was talking off the record,” Rosenkranz says.

During their casual and wide-ranging discussion, the physicist expressed himself more freely than he had ever done while in the states. The lengthy interview appeared in the Courant on July 4 to little attention.

But the comments quickly ricocheted: Three days after the initial interview, excerpts translated into German were published in Berliner Tageblatt, the most popular liberal German newspaper in Berlin. These excerpts were then translated into English and published the next day in the New York Times.

Rather than an expansive conversation about Einstein’s reflections on his trip, Americans picking up their Times on July 8 were greeted, under the headline “ Einstein Declares Women Rule Here ,” to a fusillade of casual insults of the country he’d dazzled just weeks before.

Among his observations:

He described how women “dominate the entire life in America,” and that “men take an interest in absolutely nothing at all. They work and work, the like of which I have never seen anywhere yet. For the rest they are the toy dogs of the women, who spend the money in a most unmeasurable, illimitable way.”

“The excessive enthusiasm for me in America appears to be typically American. And if I grasp it correctly the reason is that the people in America are so colossally bored, very much more than is the case with us. After all, there is so little for them there!”

“There are cities with 1,000,000 inhabitants, despite which what poverty, intellectual poverty! The people are, therefore, glad when something is given them with which they can play and over which they can enthuse. And that they do, then, with monstrous intensity.”

While he complimented a few of the scientists with whom he had spoken, Einstein concluded that “to compare the general scientific life in America with Europe is nonsense.”

Einstein Does Damage Control

Backlash followed immediately, provoking complaints from newspaper editors, academics and members of the public, who defended the U.S. and questioned the scientist’s character. Within three days of the story hitting print, the New York Times featured updates and analysis under headlines including “Chicago Women Resent Einstein’s Opinion,” “Probably He Did Say It All,” “A Product of His Education.” The Gray Lady also published a letter from Popular Science editor Kenneth Payne claiming that the “ Eminent Scientist Failed to Understand Us .”

Rather than complete anger, many responses expressed sadness that the charming genius who’d engrossed Americans did not seem to reciprocate their warm feelings.

Polish-American physicist Ludwik Silberstein wrote directly to Einstein, expressing concern from him and other scientists, asking that “you please tell me whether this ‘correspondence’ originates with you (I mean, whether what you said has been correctly reproduced) or is instead an invention by the newspaperman and therefore the whole or a part of it is false.”

The comments, of course, alarmed Chaim Weizmann. The negative coverage threatened to not only embarrass Einstein, but to hurt the entire effort he’d been enlisted to help.

Einstein scrambled to clean up the mess, telling the Tageblatt editor that he “absolutely disagrees” with the translation of what he’d said. He sent a telegram to the Zionist Organization of America (a rival to the World Zionist Organization) declaring that he would like “to deny the veracity of statements credited to me” in the story.

He even provided an interview to the Berlin newspaper Vossische Zeitung in which he referred to the original story as “so hopelessly inaccurate that I feel more than justified in giving my own account” to refute it.

While Einstein issued one response after another, “he’s not exactly denying everything that he said,” according to Rosenkranz. “He wasn’t upset by the views that were published as much as how they were perceived and the selectiveness of it.”

Indeed, the New York Times headlined its coverage of this interview as being, “Explanation Rather Than Denial.”

Einstein’s efforts managed to at least partly calm the furor. By July 18, Silberstein wrote to Einstein expressing relief that “we knew very well that this correspondence (evaluation of America) cannot have stemmed from you.” Most seemed willing to just take the scientist’s word for it that he meant no ill will.

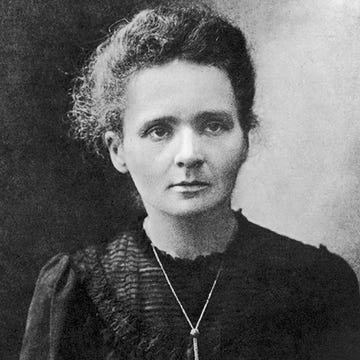

Overall, Einstein proved himself as comfortable saying one thing in public while expressing less prudent views privately. Lipscombe points to a stirring eulogy he gave for Marie Curie in which he said many wonderful things about her, but also wrote in a private letter that she “is very intelligent, but has the soul of a herring, meaning that she is lacking in all feelings of joy and sorrow.”

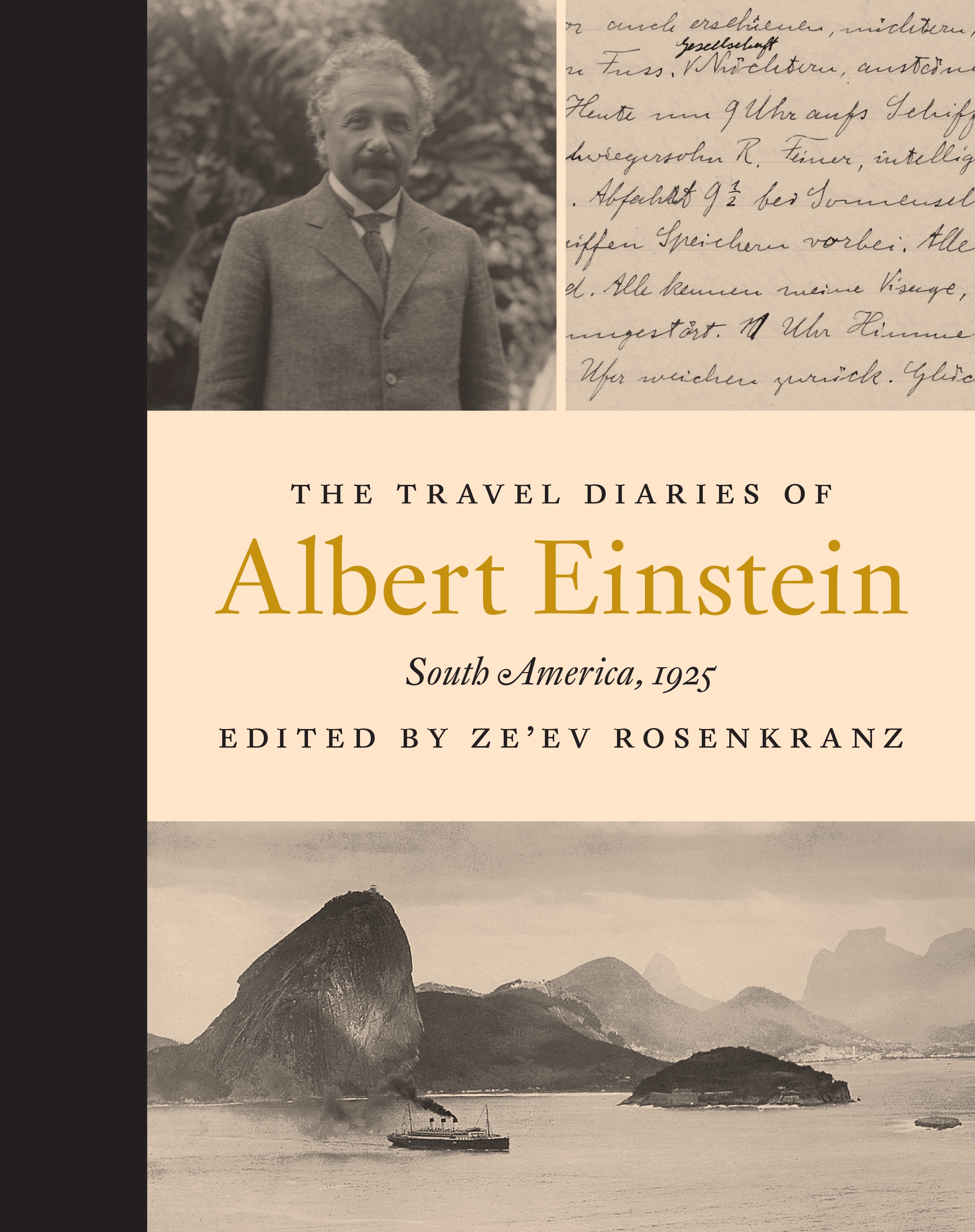

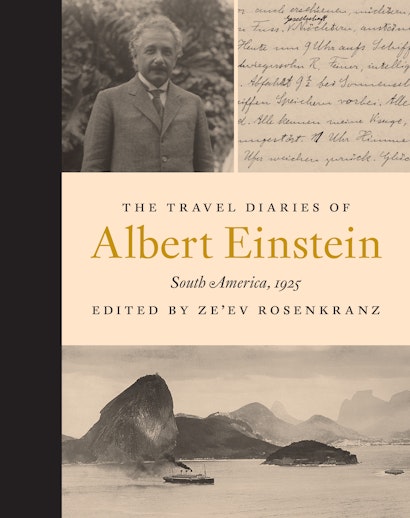

And in The Travel Diaries of Albert Einstein , edited by Rosenkranz, Einstein expresses a variety of stereotypes and racist views about people he meets throughout his travels through Asia and the Middle East. These writings conflict with his civil rights advocacy later in his career.

The Physicist’s Press Comeback

However accurate the original report had been, Lipscombe sees the many times Einstein attempted to clean up his statements as characteristic of the physicist, who would sometimes speak first and clarify later. “In his science writing, very often he writes a paper, then he writes either a correction to it or an addendum to it,” Lipscombe says. For example: the famous Princeton lectures Einstein had delivered three months earlier.

“Although the Theory of Relativity was completed and published in 1919, it took several years of revisions and refinements of the arguments,” says Hanoch Gutfreund, former president of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and co-author of Einstein on Einstein , published last year. Similarly, Einstein’s apology took a few tries before he felt it was satisfactory.

While the post-tour interview mess reflected how Einstein was still adapting to his role as a public figure, it also represented a turning point for the scientist: He was suddenly learning how his high profile could not only draw attention to his work, but also to his beliefs.

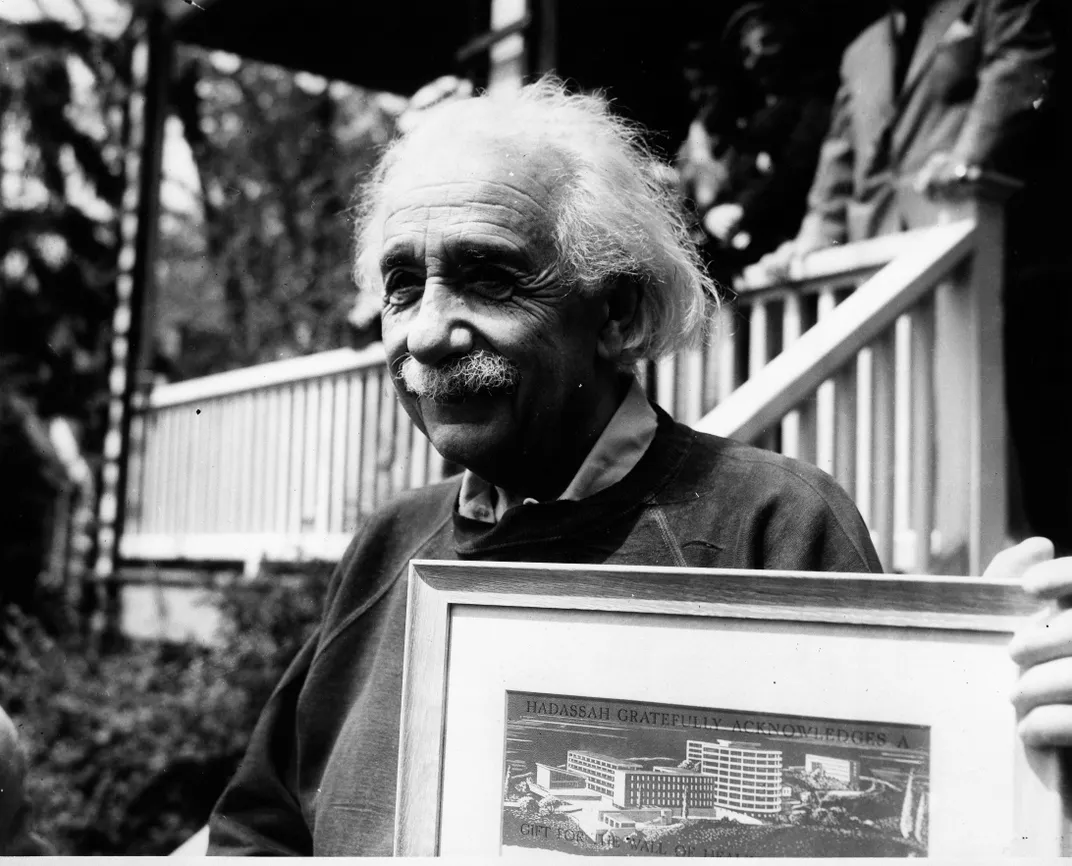

In subsequent years, Einstein would continue his advocacy and fundraising to increasing effect for the Hebrew University — expressing pride at the opening of its Mount Scopus campus in 1925 and serving on its first Board of Governors — as well as for a number of other causes including civil rights , international cooperation and humanitarianism. Meanwhile, he’d refrain from further rash comments.

“In 1921, he’s still really finding his feet when it comes to talking to the press,” Rosenkranz says. “He becomes much more circumspect about what he says to the press after that. Eventually he learns how to use it for his own purposes and the causes he wants to advance — he uses his public persona.”

- behavior & society

Already a subscriber?

Register or Log In

Keep reading for as low as $1.99!

Sign up for our weekly science updates.

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Advertisement

Voice of the Engineer

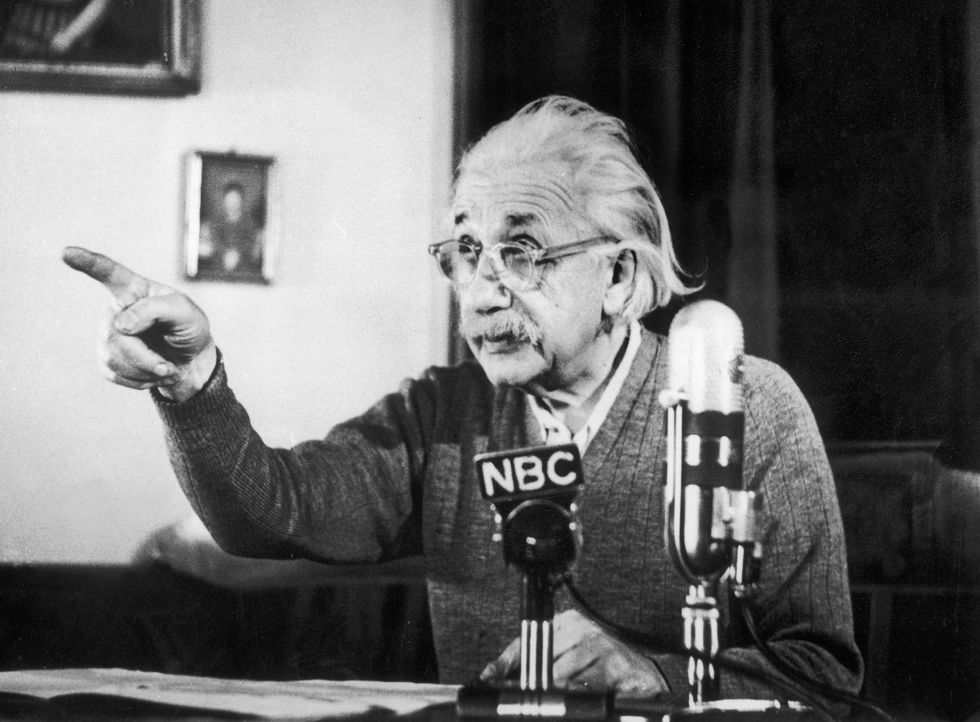

Einstein moves to US, October 17, 1933

He and his wife Elsa returned by ship to Belgium in March 1933 to find that that their cottage had been raided. Einstein turned in his passport to the German consulate and formally renounced his German citizenship. By the summer, Einstein learned that his name was on a list of assassination targets.

He resided in Belgium for some months and then moved to England for a short period. On October 17, 1933, he returned to the US and took up a position at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton in New Jersey. The Princeton agreement required he stay for six months. With offers from numerous universities, including Oxford, Einstein was undecided on his future.

In 1935 Einstein decided to stay in the US and became a citizen in 1940. His affiliation with the Institute for Advanced Study would last until his death in 1955.

In the 20-plus years he lived in the US, Einstein made many contributions, perhaps most notably the atomic bomb. On the eve of World War II, Einstein helped alert President Franklin D Roosevelt that Germany might be developing an atomic weapon. Upon Einstein’s recommendation, the US began similar research, which would eventually lead to the Manhattan Project . Einstein was in support of defending the Allied forces, but largely denounced using the new discovery of nuclear fission as a weapon.

Also during his time in the US, Einstein tried to develop a unified field theory and to refute the accepted interpretation of quantum physics, both unsuccessfully.

Einstein died at Princeton Hospital in 1955 after suffering a burst aortic aneurysm.

Related articles:

- Albert Einstein is born, March 14, 1879

- Wise words from Einstein, Tesla, Spock, and others

- Einstein wins 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics, November 9, 1922

- Greatest minds in physics play poker

- Einstein’s relatively funny photo

- Atomic bomb drops on Hiroshima, August 6, 1945

- Einstein’s theory of general relativity is tested, May 29, 1919

- Einstein paper outlines E=mc2, November 21, 1905

For more moments in tech history, see this blog . EDN strives to be historically accurate with these postings. Should you see an error, please notify us .

Editor’s note : This article was originally posted on October 17, 2012 and edited on October 17, 2019.

div-gpt-ad-inread

2 comments on “ Einstein moves to US, October 17, 1933 ”

This was the same Einstein that J. Edgar Hoover mistrusted and thought was a commie. Hoovers paranoia kept Einstein off the A. Bomb project and out of government labs.

Einstein loved humanity and hated war, and saw thru the lies about “good wars”. All wars destroy humans beings, 99.9% of whom are either innocent, or just acting in good faith (fighting for country of birth). Einstein could not be controlled, not by Hitler or even lesser versions like Hoover.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must Sign in or Register to post a comment.

[ninja_form id=2]

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

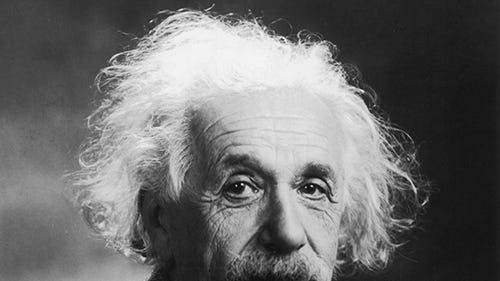

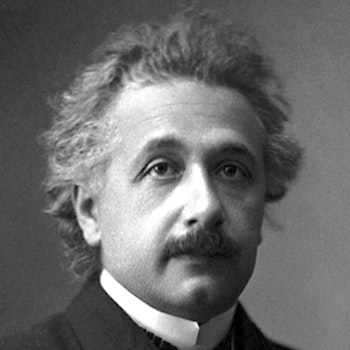

Albert Einstein

By: History.com Editors

Updated: May 16, 2019 | Original: October 27, 2009

The German-born physicist Albert Einstein developed the first of his groundbreaking theories while working as a clerk in the Swiss patent office in Bern. After making his name with four scientific articles published in 1905, he went on to win worldwide fame for his general theory of relativity and a Nobel Prize in 1921 for his explanation of the phenomenon known as the photoelectric effect. An outspoken pacifist who was publicly identified with the Zionist movement, Einstein emigrated from Germany to the United States when the Nazis took power before World War II. He lived and worked in Princeton, New Jersey, for the remainder of his life.

Einstein’s Early Life (1879-1904)

Born on March 14, 1879, in the southern German city of Ulm, Albert Einstein grew up in a middle-class Jewish family in Munich. As a child, Einstein became fascinated by music (he played the violin), mathematics and science. He dropped out of school in 1894 and moved to Switzerland, where he resumed his schooling and later gained admission to the Swiss Federal Polytechnic Institute in Zurich. In 1896, he renounced his German citizenship, and remained officially stateless before becoming a Swiss citizen in 1901.

Did you know? Almost immediately after Albert Einstein learned of the atomic bomb's use in Japan, he became an advocate for nuclear disarmament. He formed the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists and backed Manhattan Project scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer in his opposition to the hydrogen bomb.

While at Zurich Polytechnic, Einstein fell in love with his fellow student Mileva Maric, but his parents opposed the match and he lacked the money to marry. The couple had an illegitimate daughter, Lieserl, born in early 1902, of whom little is known. After finding a position as a clerk at the Swiss patent office in Bern, Einstein married Maric in 1903; they would have two more children, Hans Albert (born 1904) and Eduard (born 1910).

Einstein’s Miracle Year (1905)

While working at the patent office, Einstein did some of the most creative work of his life, producing no fewer than four groundbreaking articles in 1905 alone. In the first paper, he applied the quantum theory (developed by German physicist Max Planck) to light in order to explain the phenomenon known as the photoelectric effect, by which a material will emit electrically charged particles when hit by light. The second article contained Einstein’s experimental proof of the existence of atoms, which he got by analyzing the phenomenon of Brownian motion, in which tiny particles were suspended in water.

In the third and most famous article, titled “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies,” Einstein confronted the apparent contradiction between two principal theories of physics: Isaac Newton’s concepts of absolute space and time and James Clerk Maxwell’s idea that the speed of light was a constant. To do this, Einstein introduced his special theory of relativity, which held that the laws of physics are the same even for objects moving in different inertial frames (i.e. at constant speeds relative to each other), and that the speed of light is a constant in all inertial frames. A fourth paper concerned the fundamental relationship between mass and energy, concepts viewed previously as completely separate. Einstein’s famous equation E = mc2 (where “c” was the constant speed of light) expressed this relationship.

From Zurich to Berlin (1906-1932)

Einstein continued working at the patent office until 1909, when he finally found a full-time academic post at the University of Zurich. In 1913, he arrived at the University of Berlin, where he was made director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics. The move coincided with the beginning of Einstein’s romantic relationship with a cousin of his, Elsa Lowenthal, whom he would eventually marry after divorcing Mileva. In 1915, Einstein published the general theory of relativity, which he considered his masterwork. This theory found that gravity, as well as motion, can affect time and space. According to Einstein’s equivalence principle–which held that gravity’s pull in one direction is equivalent to an acceleration of speed in the opposite direction–if light is bent by acceleration, it must also be bent by gravity. In 1919, two expeditions sent to perform experiments during a solar eclipse found that light rays from distant stars were deflected or bent by the gravity of the sun in just the way Einstein had predicted.

The general theory of relativity was the first major theory of gravity since Newton’s, more than 250 years before, and the results made a tremendous splash worldwide, with the London Times proclaiming a “Revolution in Science” and a “New Theory of the Universe.” Einstein began touring the world, speaking in front of crowds of thousands in the United States, Britain, France and Japan. In 1921, he won the Nobel Prize for his work on the photoelectric effect, as his work on relativity remained controversial at the time. Einstein soon began building on his theories to form a new science of cosmology, which held that the universe was dynamic instead of static, and was capable of expanding and contracting.

Einstein Moves to the United States (1933-39)

A longtime pacifist and a Jew, Einstein became the target of hostility in Weimar Germany, where many citizens were suffering plummeting economic fortunes in the aftermath of defeat in the Great War. In December 1932, a month before Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany, Einstein made the decision to emigrate to the United States, where he took a position at the newly founded Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey . He would never again enter the country of his birth.

By the time Einstein’s wife Elsa died in 1936, he had been involved for more than a decade with his efforts to find a unified field theory, which would incorporate all the laws of the universe, and those of physics, into a single framework. In the process, Einstein became increasingly isolated from many of his colleagues, who were focused mainly on the quantum theory and its implications, rather than on relativity.

Einstein’s Later Life (1939-1955)

In the late 1930s, Einstein’s theories, including his equation E=mc2, helped form the basis of the development of the atomic bomb. In 1939, at the urging of the Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard, Einstein wrote to President Franklin D. Roosevelt advising him to approve funding for the development of uranium before Germany could gain the upper hand. Einstein, who became a U.S. citizen in 1940 but retained his Swiss citizenship, was never asked to participate in the resulting Manhattan Project , as the U.S. government suspected his socialist and pacifist views. In 1952, Einstein declined an offer extended by David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s premier, to become president of Israel .

Throughout the last years of his life, Einstein continued his quest for a unified field theory. Though he published an article on the theory in Scientific American in 1950, it remained unfinished when he died, of an aortic aneurysm, five years later. In the decades following his death, Einstein’s reputation and stature in the world of physics only grew, as physicists began to unravel the mystery of the so-called “strong force” (the missing piece of his unified field theory) and space satellites further verified the principles of his cosmology.

HISTORY Vault: Secrets of Einstein's Brain

Originally stolen by the doctor trusted to perform his autopsy, scientists over the decades have examined the brain of Albert Einstein to try and determine what made this seemingly normal man tick.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Follow us on LinkedIn

- Watch us on Youtube

- Latest Explore all the latest news and information on Physics World

- Research updates Keep track of the most exciting research breakthroughs and technology innovations

- News Stay informed about the latest developments that affect scientists in all parts of the world

- Features Take a deeper look at the emerging trends and key issues within the global scientific community

- Opinion and reviews Find out whether you agree with our expert commentators

- Interviews Discover the views of leading figures in the scientific community

- Analysis Discover the stories behind the headlines

- Blog Enjoy a more personal take on the key events in and around science

- Physics World Live

- Impact Explore the value of scientific research for industry, the economy and society

- Events Plan the meetings and conferences you want to attend with our comprehensive events calendar

- Innovation showcases A round-up of the latest innovation from our corporate partners

- Collections Explore special collections that bring together our best content on trending topics

- Artificial intelligence Explore the ways in which today’s world relies on AI, and ponder how this technology might shape the world of tomorrow

- #BlackInPhysics Celebrating Black physicists and revealing a more complete picture of what a physicist looks like

- Nanotechnology in action The challenges and opportunities of turning advances in nanotechnology into commercial products

- The Nobel Prize for Physics Explore the work of recent Nobel laureates, find out what happens behind the scenes, and discover some who were overlooked for the prize

- Revolutions in computing Find out how scientists are exploiting digital technologies to understand online behaviour and drive research progress

- The science and business of space Explore the latest trends and opportunities associated with designing, building, launching and exploiting space-based technologies

- Supercool physics Experiments that probe the exotic behaviour of matter at ultralow temperatures depend on the latest cryogenics technology

- Women in physics Celebrating women in physics and their contributions to the field

- Audio and video Explore the sights and sounds of the scientific world

- Podcasts Our regular conversations with inspiring figures from the scientific community

- Video Watch our specially filmed videos to get a different slant on the latest science

- Webinars Tune into online presentations that allow expert speakers to explain novel tools and applications

- IOP Publishing

- Enter e-mail address

- Show Enter password

- Remember me Forgot your password?

- Access more than 20 years of online content

- Manage which e-mail newsletters you want to receive

- Read about the big breakthroughs and innovations across 13 scientific topics

- Explore the key issues and trends within the global scientific community

- Choose which e-mail newsletters you want to receive

Reset your password

Please enter the e-mail address you used to register to reset your password

Registration complete

Thank you for registering with Physics World If you'd like to change your details at any time, please visit My account

- Opinion and reviews

Einstein, the travelling physicist

Einstein on the Road Josef Eisinger 2011 Prometheus Books £21.95/ $25.00hb 219pp

Albert Einstein did not normally keep a diary, but he often wrote in travel notebooks. From 1921 to 1933 his itinerary included trips to New York, Hong Kong, Singapore, Malacca, Penong, Palestine, Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, Havana, Palm Springs, Oxford, Panama, Honduras, Salvador and beyond. Josef Eisinger’s Einstein on the Road tells the story of these journeys, drawing mostly from Einstein’s unpublished notebooks.

After newspapers trumpeted the eclipse observations that supported Einstein’s theory of gravity, turning him into an international celebrity in 1919, people around the world clamoured to see him. The worsening political situation back home in Germany also led him to travel. At first, Einstein had appreciated the Weimar Republic as his political dreams come true, but growing hostilities there – including the 1922 assassination of his Jewish friend Walther Rathenau, the republic’s foreign minister – meant that he soon found reasons to travel outside “woeful Europe”.

The title Einstein on the Road is something of a misnomer, since most of Einstein’s journeys took place aboard cruise ships. Einstein did not want to give guest lectures anywhere. He despised photograph sessions, tiresome receptions and the barrage of journalists’ inane questions: “Define the fourth dimension in one word”, “Define relativity in one sentence”. But travel on board ship was different. Away from reporters and fans, he had some leisure time to think about physics, and to pay attention to little things. He noticed, for example, that younger people are more prone to being seasick than old people, and women more susceptible than men. Once, when his ship was in a storm, he stood on a bathroom scale and noted with interest that his weight oscillated between heaviest and lightest in the ratio of 3:2. From this, he computed the ship’s acceleration as it dropped into the trough between waves.

Einstein’s notes contain some clever moments, but also biases. I was particularly amused by the way he seemed to subscribe to the old theory that regional climates determine native behaviours. While travelling through the Strait of Messina, towards the Mediterranean, Einstein reacted to the heat and “severity” of the landscapes by speculating that the climate must have been different in antiquity, such that the Greeks and Jews inhabited a temperate zone more suitable for intellectual work. He also thought that the people of the island of Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and China were primitive and miserable because of their tropical climates. Tepid water in the equator, he argued, spread serenity and drowsiness.

On land, Einstein’s experiences and impressions were varied. In person, he was gracious, patient and clever. But in his travel books he recorded snippy thoughts too. He was delighted by the enthusiasm and friendliness of the people of Japan, but he disliked their music and inferred that the Japanese were more artistic than intellectual by nature. He was deeply affected by visiting Palestine, yet when he saw many Jews praying at the Wailing Wall he thought “the dull-witted fellow-members of the tribe” made a deplorable scene. Einstein thought that the Chinese, though modest and gentle, were the most unfortunate people on Earth: listless, cruelly abused and treated worse than cattle. Meanwhile, in Pasadena, California, people seemed to him like scentless flowers.

Thousands of admirers swarmed around Einstein, on docks, in the streets, in lecture halls. They bought expensive tickets to see him. Most did not understand what he said, in German or in French, yet they were fascinated. Einstein complained that he did not know why people were so interested in his theories. He made few public pronouncements at events and receptions, and told his wife, Elsa, that he felt like a con artist who did not give people what they expected. Unlike the work of Copernicus, he said, his theories of relativity did not effect any radical change of perspective on humanity’s place in the universe. Although he accepted honorary degrees, he did not wear the medals. He tolerated countless handshakes and journalists as a slow form of torture, recalling the German proverb “Anyone can get used to being hanged”.

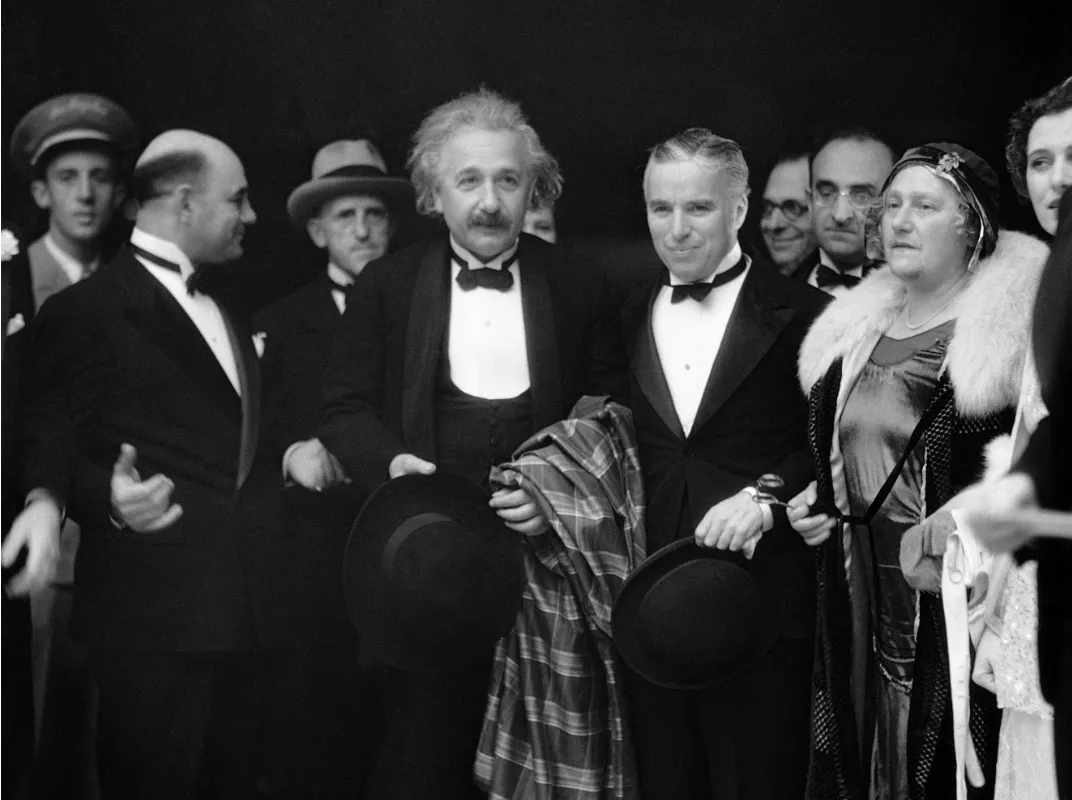

Eisinger’s book records such amusing complaints, but it also gradually demolishes the old impression that Einstein wanted to be a recluse. He said that he did, but his actions give a different impression. He met scores of individuals and carried out a voluminous correspondence with them. He socialized until it made him physically ill. Though he claimed to be indifferent to social standing, he took especial care to befriend people who were wealthy and successful. He hobnobbed with presidents and royalty. He was accessible to famous musicians. With them, many times, Einstein played Mozart on his violin, to the extent that Mozart could have been a secondary character in the book.

Einstein on the Road is easy to read, and Eisinger, an emeritus professor who has worked on nuclear physics and molecular biology, makes a pleasant narrator. At its best, his book is an interesting travelogue. But at its worst, it illustrates a little too well the tedium Einstein suffered by constantly meeting boring strangers. The book is thin on scientific content, with just faint glimpses of Einstein’s work on physics, though perhaps more relating to astronomy and cosmology, such as his support of Richard Tolman’s model of a pulsating universe. Similarly, most of Einstein’s more intriguing encounters are mentioned much too briefly. Passing descriptions of meetings with Clarence Darrow, Winston Churchill and many others are gone in a blink. Eisinger also mentions books that Einstein read at sea – on Chinese wisdom, Jewish history and so on – but lacks discussion of their substance. It would have been better to select fewer anecdotes and develop them more.

Einstein on the Road includes 42 photographs but unfortunately most are already well known: Einstein as a child; at the patent office; with his first wife Mileva Mari? with Charlie Chaplin. Photographs of Einstein in the many countries he visited would have been much better. The book also suffers from minor mistakes, mostly in the background material. For example, Eisinger states that Einstein was recognized as a child prodigy entering the Zürich Polytechnic (he was not), that his daughter was “quietly given up for adoption” (we do not know what happened to her) and that his first paper of 1905 showed the equivalence of mass and energy (it was on the photoelectric effect). Nonetheless, Einstein on the Road is a welcome contribution to the literature as it illuminates how Einstein gradually departed from the isolated individual he once was.

Want to read more?

- E-mail Address

Alberto A Martínez is a historian at the University of Texas at Austin, US, and the author, most recently, of Science Secrets: the Truth About Darwin's Finches, Einstein's Wife, and Other Myths

Physics World Careers

Providing valuable careers advice and a comprehensive employer directory

- Telescopes and space missions

Neil deGrasse Tyson makes the case for space exploration

Atmospheric tales, discover more from physics world.

- Quantum mechanics

Entangled entities: Bohr, Einstein and the battle over quantum fundamentals

- Particle and nuclear

Peter Higgs: the story behind his interview with Physics World

- Philosophy, sociology and religion

Can thinking like a scientist help us tackle societal issues?

Related jobs, helping you train to teach physics, classified networks vulnerability and protective monitoring liaison officer, faculty position in theoretical physics (lecturer in extrasolar planets), related events.

- Materials | Symposium The Eigthth International Symposium on Dielectric Materials and Applications (ISyDMA'8) 12—16 May 2024 | Orlando, US

- Materials | Symposium Eighth International Symposium on Dielectric Materials and Applications (ISyDMA'8) 12—16 May 2024 | Orlando, US

- Biophysics and bioengineering | Workshop Chemotaxis – from Basic Physics to Biology 13—17 May 2024 | Dresden, Germany

- 0 Comments Add Your Comment

Albert Einstein in America, 1921

July 1, 2009 • Walter Isaacson

Albert Einstein’s exploding global fame and budding Zionism came together in the spring of 1921 for an event that was unique in the history of science, and indeed remarkable for any realm: a grand two-month processional through the eastern and midwestern United States that evoked the sort of mass frenzy and press adulation that would thrill a touring rock star. The world had never before seen, and perhaps will never again, such a scientific celebrity superstar, one who also happened to be a gentle icon of humanist values and a living patron saint for Jews.

Princeton University Press, as volume 12 in its Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, is publishing his correspondence for this amazing and critical year of his life. It includes the full text of 169 letters he wrote this year along with 180 that he received. Also included is a detailed calendar of his year that draws on information from hundreds of other documents. All told, the volume presents an exquisite and rich tapestry of Einstein’s initial involvement with the Zionist movement and with the United States, which 12 years later would become his home.

Einstein had initially thought that his first visit to America might be a way to make some money in a stable currency in order to provide for his family in Switzerland. “I have demanded $15,000 from Princeton and Wisconsin,” he wrote his friend and fellow scientist Paul Ehrenfest. “It will probably scare them off. But if they do bite, I will be buying economic independence for myself – and that’s not a thing to sniff at.”

The American universities did not bite. “My demands were too high,” he reported back to Ehrenfest. So by February of 1921, he had made other plans for the spring: He would present a paper at the third Solvay Conference in Brussels and give some lectures in Leiden at the behest of Ehrenfest.

Continue reading in the Princeton University Press blog.

Related Posts

March 29, 2024 Rev. Dr. Audrey Price & 1 more

October 16, 2023 Religion & Society Program & 1 more

The best of the Institute, right in your inbox.

Sign up for our email newsletter

Albert Einstein

2011-10-12 06:06:56

Identification: German-born American physicist

Born: March 14, 1879; Ulm, Germany

Died: April 18, 1955; Princeton, New Jersey

Significance: The greatest physicist of the twentieth century, Albert Einstein found refuge from Nazi threats in the United States, where he became a symbol of scientific genius and internationalism.

Albert Einstein was born into a middle-class Jewish German family in 1879. He found German schooling stultifying and in 1895 went to study in Switzerland. He renounced his German citizenship in 1896, when he was only sixteen. During the first two decades of the twentieth century, Einstein transformed modern science with his theoretical work on the photoelectric effect, Brownian motion, quantum energy, light, gravity, relativity of space and time, and conversion of matter into energy (E = mc 2 ).

Albert Einstein. (Library of Congress)

In 1914, Einstein returned to Germany as a professor at the University of Berlin, winning the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics. Einstein’s fame brought him lectureships throughout the world; it also made him the focus of attacks in an increasingly anti-Semitic and militaristic Germany. Fearing for his safety, he and his wife, Elsa, immigrated to the United States on October 17, 1933, where Einstein accepted a position at the Institute for Advanced Study in New Jersey. Although some Americans opposed Einstein’s immigration for his "radical” views, Einstein embraced the opportunities and freedom of his new nation. He cowrote a famous letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1939 advising him of the possibilities of developing an atomic bomb. On June 22, 1940, Einstein took his American citizenship test and gave a talk for the government’s I Am an American radio series; he was naturalized on October 1, 1940. After World War II, Einstein advocated nuclear disarmament and international cooperation. He died in 1955.

Howard Bromberg

Further Reading

Isaacson, Walter. Albert Einstein: His Life and Universe. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007.

Sayen, Jamie. Einstein in America: The Scientist’s Conscience in the Age of Hitler and Hiroshima. New York: Crown, 1985.

Schweber, Silvan. Einstein and Oppenheimer: The Meaning of Genius. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2008.

See also: Anti-Semitism; Citizenship and Immigration Services, U.S.; Congress, U.S.; German immigrants; Jewish immigrants; Naturalization; New Jersey; Science; Swiss immigrants; World War II.

- Immigrant groups

- Civil rights and liberties

- Refugees and displaced persons

- Court cases

- Illegal immigration

- Advocacy organizations and movements

- Arts and music

- European immigrants

- Anti-immigrant movements and policies

- African immigrants

- Citizenship and naturalization

- Asian immigrants

- Agricultural workers

- Immigration reform

- East asian immigrants

- Deportation

- Events and movements

- International agreements

- Mexican immigrants

- Ethnic enclaves

- Latin american immigrants

- Science and technology

- Government agencies and commissions

- Politics and government

- Family issues

- Economic issues

- Southeast asian immigrants

- Canadian immigrants

- Push-pull factors

- Transportation

- Philanthropy

- Demographics

- Assimilation

- Subversive and radical political movements

- Communications

- Language issues

- Law enforcement

- West indian immigrants

- Stereotypes

- South and Southwest Asian immigrants

- Pacific Islander immigrants

- Colonies and colonial regions

- Legislation and regulations

- United States

- War and immigration

- Administration

- Hispanic issues and leaders

- Economics and commerce

- Immigration policy

- Colonial founders and leaders

- Explorers and geographers

- Political figures: Canada

- Political figures: United States

- Race and ethnicity

- Reformers, activists, and ethnic leaders

Albert Einstein

One of the most influential scientists of the 20 th century, Albert Einstein was a physicist who developed the theory of relativity.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back.

Quick Facts

Early life, family, and education, einstein’s iq, patent clerk, inventions and discoveries, nobel prize in physics, wives and children, travel diaries, becoming a u.s. citizen, einstein and the atomic bomb, time travel and quantum theory, personal life, death and final words, einstein’s brain, einstein in books and movies: "oppenheimer" and more, who was albert einstein.

Albert Einstein was a German mathematician and physicist who developed the special and general theories of relativity. In 1921, he won the Nobel Prize in Physics for his explanation of the photoelectric effect. In the following decade, he immigrated to the United States after being targeted by the German Nazi Party. His work also had a major impact on the development of atomic energy. In his later years, Einstein focused on unified field theory. He died in April 1955 at age 76. With his passion for inquiry, Einstein is generally considered the most influential physicist of the 20 th century.

FULL NAME: Albert Einstein BORN: March 14, 1879 DIED: April 18, 1955 BIRTHPLACE: Ulm, Württemberg, Germany SPOUSES: Mileva Einstein-Maric (1903-1919) and Elsa Einstein (1919-1936) CHILDREN: Lieserl, Hans, and Eduard ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Pisces

Albert Einstein was born on March 14, 1879, in Ulm, Württemberg, Germany. He grew up in a secular Jewish family. His father, Hermann Einstein, was a salesman and engineer who, with his brother, founded Elektrotechnische Fabrik J. Einstein & Cie, a Munich-based company that mass-produced electrical equipment. Einstein’s mother, the former Pauline Koch, ran the family household. Einstein had one sister, Maja, born two years after him.

Einstein attended elementary school at the Luitpold Gymnasium in Munich. However, he felt alienated there and struggled with the institution’s rigid pedagogical style. He also had what were considered speech challenges. However, he developed a passion for classical music and playing the violin, which would stay with him into his later years. Most significantly, Einstein’s youth was marked by deep inquisitiveness and inquiry.

Toward the end of the 1880s, Max Talmud, a Polish medical student who sometimes dined with the Einstein family, became an informal tutor to young Einstein. Talmud had introduced his pupil to a children’s science text that inspired Einstein to dream about the nature of light. Thus, during his teens, Einstein penned what would be seen as his first major paper, “The Investigation of the State of Aether in Magnetic Fields.”

Hermann relocated the family to Milan, Italy, in the mid-1890s after his business lost out on a major contract. Einstein was left at a relative’s boarding house in Munich to complete his schooling at the Luitpold.

Faced with military duty when he turned of age, Einstein allegedly withdrew from classes, using a doctor’s note to excuse himself and claim nervous exhaustion. With their son rejoining them in Italy, his parents understood Einstein’s perspective but were concerned about his future prospects as a school dropout and draft dodger.

Einstein was eventually able to gain admission into the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, specifically due to his superb mathematics and physics scores on the entrance exam. He was still required to complete his pre-university education first and thus attended a high school in Aarau, Switzerland, helmed by Jost Winteler. Einstein lived with the schoolmaster’s family and fell in love with Winteler’s daughter Marie. Einstein later renounced his German citizenship and became a Swiss citizen at the dawn of the new century.

Einstein’s intelligence quotient was estimated to be around 160, but there are no indications he was ever actually tested.

Psychologist David Wechsler didn’t release the first edition of the WAIS cognitive test, which evolved into the WAIS-IV test commonly used today, until 1955—shortly before Einstein’s death. The maximum score of the current version is 160, with an IQ of 135 or higher ranking in the 99 th percentile.

Magazine columnist Marilyn vos Savant has the highest-ever recorded IQ at 228 and was featured in the Guinness Book of World Records in the late 1980s. However, Guinness discontinued the category because of debates about testing accuracy. According to Parade , individuals believed to have higher IQs than Einstein include Leonardo Da Vinci , Marie Curie , Nikola Tesla , and Nicolaus Copernicus .

After graduating from university, Einstein faced major challenges in terms of finding academic positions, having alienated some professors over not attending class more regularly in lieu of studying independently.

Einstein eventually found steady work in 1902 after receiving a referral for a clerk position in a Swiss patent office. While working at the patent office, Einstein had the time to further explore ideas that had taken hold during his university studies and thus cemented his theorems on what would be known as the principle of relativity.

In 1905—seen by many as a “miracle year” for the theorist—Einstein had four papers published in the Annalen der Physik , one of the best-known physics journals of the era. Two focused on the photoelectric effect and Brownian motion. The two others, which outlined E=MC 2 and the special theory of relativity, were defining for Einstein’s career and the course of the study of physics.

As a physicist, Einstein had many discoveries, but he is perhaps best known for his theory of relativity and the equation E=MC 2 , which foreshadowed the development of atomic power and the atomic bomb.

Theory of Relativity

Einstein first proposed a special theory of relativity in 1905 in his paper “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies,” which took physics in an electrifying new direction. The theory explains that space and time are actually connected, and Einstein called this joint structure space-time.

By November 1915, Einstein completed the general theory of relativity, which accounted for gravity’s relationship to space-time. Einstein considered this theory the culmination of his life research. He was convinced of the merits of general relativity because it allowed for a more accurate prediction of planetary orbits around the sun, which fell short in Isaac Newton ’s theory. It also offered a more expansive, nuanced explanation of how gravitational forces worked.

Einstein’s assertions were affirmed via observations and measurements by British astronomers Sir Frank Dyson and Sir Arthur Eddington during the 1919 solar eclipse, and thus a global science icon was born. Today, the theories of relativity underpin the accuracy of GPS technology, among other phenomena.

Even so, Einstein did make one mistake when developing his general theory, which naturally predicted the universe is either expanding or contracting. Einstein didn’t believe this prediction initially, instead holding onto the belief that the universe was a fixed, static entity. To account for, this he factored in a “cosmological constant” to his equation. His later theories directly contracted this idea and asserted that the universe could be in a state of flux. Then, astronomer Edwin Hubble deduced that we indeed inhabit an expanding universe. Hubble and Einstein met at the Mount Wilson Observatory near Los Angeles in 1931.

Decades after Einstein’s death, in 2018, a team of scientists confirmed one aspect of Einstein’s general theory of relativity: that the light from a star passing close to a black hole would be stretched to longer wavelengths by the overwhelming gravitational field. Tracking star S2, their measurements indicated that the star’s orbital velocity increased to over 25 million kph as it neared the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy, its appearance shifting from blue to red as its wavelengths stretched to escape the pull of gravity.

Einstein’s E=MC²

Einstein’s 1905 paper on the matter-energy relationship proposed the equation E=MC²: the energy of a body (E) is equal to the mass (M) of that body times the speed of light squared (C²). This equation suggested that tiny particles of matter could be converted into huge amounts of energy, a discovery that heralded atomic power.

Famed quantum theorist Max Planck backed up the assertions of Einstein, who thus became a star of the lecture circuit and academia, taking on various positions before becoming director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics (today is known as the Max Planck Institute for Physics) from 1917 to 1933.

In 1921, Einstein won the Nobel Prize in Physics for his explanation of the photoelectric effect, since his ideas on relativity were still considered questionable. He wasn’t actually given the award until the following year due to a bureaucratic ruling, and during his acceptance speech, he still opted to speak about relativity.

Einstein married Mileva Maric on January 6, 1903. While attending school in Zurich, Einstein met Maric, a Serbian physics student. Einstein continued to grow closer to Maric, but his parents were strongly against the relationship due to her ethnic background.

Nonetheless, Einstein continued to see her, with the two developing a correspondence via letters in which he expressed many of his scientific ideas. Einstein’s father passed away in 1902, and the couple married shortly thereafter.

Einstein and Mavic had three children. Their daughter, Lieserl, was born in 1902 before their wedding and might have been later raised by Maric’s relatives or given up for adoption. Her ultimate fate and whereabouts remain a mystery. The couple also had two sons: Hans Albert Einstein, who became a well-known hydraulic engineer, and Eduard “Tete” Einstein, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia as a young man.

The Einsteins’ marriage would not be a happy one, with the two divorcing in 1919 and Maric having an emotional breakdown in connection to the split. Einstein, as part of a settlement, agreed to give Maric any funds he might receive from possibly winning the Nobel Prize in the future.

During his marriage to Maric, Einstein had also begun an affair some time earlier with a cousin, Elsa Löwenthal . The couple wed in 1919, the same year of Einstein’s divorce. He would continue to see other women throughout his second marriage, which ended with Löwenthal’s death in 1936.

In his 40s, Einstein traveled extensively and journaled about his experiences. Some of his unfiltered private thoughts are shared two volumes of The Travel Diaries of Albert Einstein .

The first volume , published in 2018, focuses on his five-and-a-half month trip to the Far East, Palestine, and Spain. The scientist started a sea journey to Japan in Marseille, France, in autumn of 1922, accompanied by his second wife, Elsa. They journeyed through the Suez Canal, then to Sri Lanka, Singapore, Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Japan. The couple returned to Germany via Palestine and Spain in March 1923.

The second volume , released in 2023, covers three months that he spent lecturing and traveling in Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil in 1925.

The Travel Diaries contain unflattering analyses of the people he came across, including the Chinese, Sri Lankans, and Argentinians, a surprise coming from a man known for vehemently denouncing racism in his later years. In an entry for November 1922, Einstein refers to residents of Hong Kong as “industrious, filthy, lethargic people.”

In 1933, Einstein took on a position at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where he would spend the rest of his life.

At the time the Nazis, led by Adolf Hitler , were gaining prominence with violent propaganda and vitriol in an impoverished post-World War I Germany. The Nazi Party influenced other scientists to label Einstein’s work “Jewish physics.” Jewish citizens were barred from university work and other official jobs, and Einstein himself was targeted to be killed. Meanwhile, other European scientists also left regions threatened by Germany and immigrated to the United States, with concern over Nazi strategies to create an atomic weapon.

Not long after moving and beginning his career at IAS, Einstein expressed an appreciation for American meritocracy and the opportunities people had for free thought, a stark contrast to his own experiences coming of age. In 1935, Einstein was granted permanent residency in his adopted country and became an American citizen five years later.

In America, Einstein mostly devoted himself to working on a unified field theory, an all-embracing paradigm meant to unify the varied laws of physics. However, during World War II, he worked on Navy-based weapons systems and made big monetary donations to the military by auctioning off manuscripts worth millions.

In 1939, Einstein and fellow physicist Leo Szilard wrote to President Franklin D. Roosevelt to alert him of the possibility of a Nazi bomb and to galvanize the United States to create its own nuclear weapons.

The United States would eventually initiate the Manhattan Project , though Einstein wouldn’t take a direct part in its implementation due to his pacifist and socialist affiliations. Einstein was also the recipient of much scrutiny and major distrust from FBI director J. Edgar Hoover . In July 1940, the U.S. Army Intelligence office denied Einstein a security clearance to participate in the project, meaning J. Robert Oppenheimer and the scientists working in Los Alamos were forbidden from consulting with him.

Einstein had no knowledge of the U.S. plan to use atomic bombs in Japan in 1945. When he heard of the first bombing at Hiroshima, he reportedly said, “Ach! The world is not ready for it.”

Einstein became a major player in efforts to curtail usage of the A-bomb. The following year, he and Szilard founded the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, and in 1947, via an essay for The Atlantic Monthly , Einstein espoused working with the United Nations to maintain nuclear weapons as a deterrent to conflict.

After World War II, Einstein continued to work on his unified field theory and key aspects of his general theory of relativity, including time travel, wormholes, black holes, and the origins of the universe.

However, he felt isolated in his endeavors since the majority of his colleagues had begun focusing their attention on quantum theory. In the last decade of his life, Einstein, who had always seen himself as a loner, withdrew even further from any sort of spotlight, preferring to stay close to Princeton and immerse himself in processing ideas with colleagues.

In the late 1940s, Einstein became a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), seeing the parallels between the treatment of Jews in Germany and Black people in the United States. He corresponded with scholar and activist W.E.B. Du Bois as well as performer Paul Robeson and campaigned for civil rights, calling racism a “disease” in a 1946 Lincoln University speech.

Einstein was very particular about his sleep schedule, claiming he needed 10 hours of sleep per day to function well. His theory of relativity allegedly came to him in a dream about cows being electrocuted. He was also known to take regular naps. He is said to have held objects like a spoon or pencil in his hand while falling asleep. That way, he could wake up before hitting the second stage of sleep—a hypnagogic process believed to boost creativity and capture sleep-inspired ideas.

Although sleep was important to Einstein, socks were not. He was famous for refusing to wear them. According to a letter he wrote to future wife Elsa, he stopped wearing them because he was annoyed by his big toe pushing through the material and creating a hole.

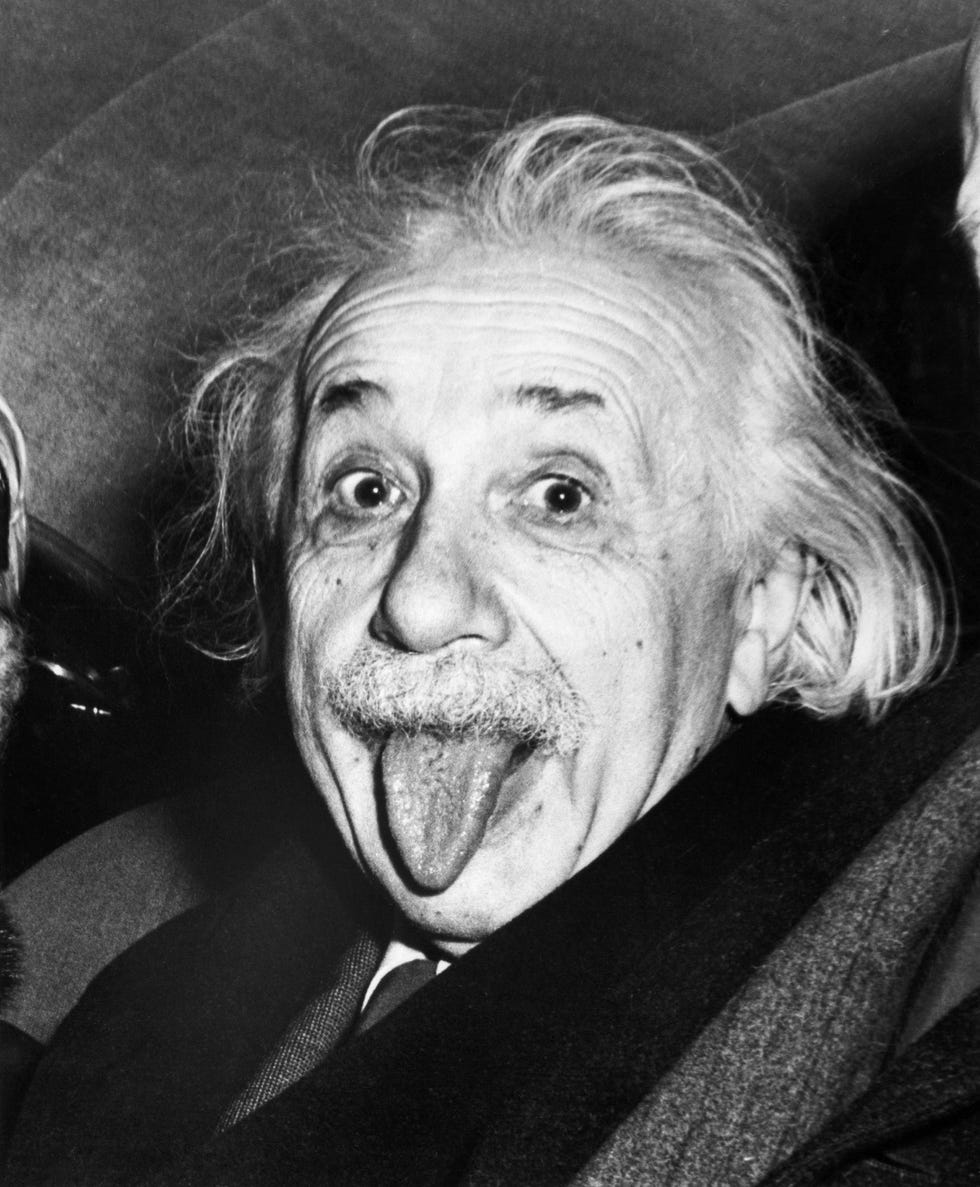

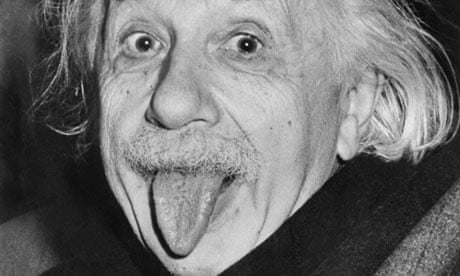

One of the most recognizable photos of the 20 th century shows Einstein sticking out his tongue while leaving his 72 nd birthday party on March 14, 1951.

According to Discovery.com , Einstein was leaving his party at Princeton when a swarm of reporters and photographers approached and asked him to smile. Tired from doing so all night, he refused and rebelliously stuck his tongue out at the crowd for a moment before turning away. UPI photographer Arthur Sasse captured the shot.

Einstein was amused by the picture and ordered several prints to give to his friends. He also signed a copy of the photo that sold for $125,000 at a 2017 auction.

Einstein died on April 18, 1955, at age 76 at the University Medical Center at Princeton. The previous day, while working on a speech to honor Israel’s seventh anniversary, Einstein suffered an abdominal aortic aneurysm.

He was taken to the hospital for treatment but refused surgery, believing that he had lived his life and was content to accept his fate. “I want to go when I want,” he stated at the time. “It is tasteless to prolong life artificially. I have done my share, it is time to go. I will do it elegantly.”

According to the BBC, Einstein muttered a few words in German at the moment of his death. However, the nurse on duty didn’t speak German so their translation was lost forever.

In a 2014 interview , Life magazine photographer Ralph Morse said the hospital was swarmed by journalists, photographers, and onlookers once word of Einstein’s death spread. Morse decided to travel to Einstein’s office at the Institute for Advanced Studies, offering the superintendent alcohol to gain access. He was able to photograph the office just as Einstein left it.

After an autopsy, Einstein’s corpse was moved to a Princeton funeral home later that afternoon and then taken to Trenton, New Jersey, for a cremation ceremony. Morse said he was the only photographer present for the cremation, but Life managing editor Ed Thompson decided not to publish an exclusive story at the request of Einstein’s son Hans.

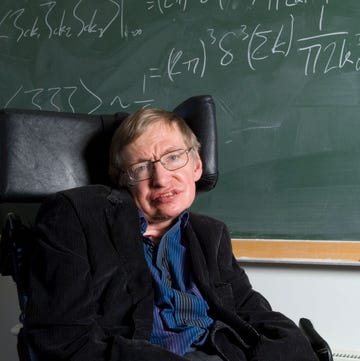

During Einstein’s autopsy, pathologist Thomas Stoltz Harvey had removed his brain, reportedly without his family’s consent, for preservation and future study by doctors of neuroscience.

However, during his life, Einstein participated in brain studies, and at least one biography claimed he hoped researchers would study his brain after he died. Einstein’s brain is now located at the Princeton University Medical Center. In keeping with his wishes, the rest of his body was cremated and the ashes scattered in a secret location.

In 1999, Canadian scientists who were studying Einstein’s brain found that his inferior parietal lobe, the area that processes spatial relationships, 3D-visualization, and mathematical thought, was 15 percent wider than in people who possess normal intelligence. According to The New York Times , the researchers believe it might help explain why Einstein was so intelligent.

In 2011, the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia received thin slices of Einstein’s brain from Dr. Lucy Rorke-Adams, a neuropathologist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and put them on display. Rorke-Adams said she received the brain slides from Harvey.

Since Einstein’s death, a veritable mountain of books have been written on the iconic thinker’s life, including Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson and Einstein: A Biography by Jürgen Neffe, both from 2007. Einstein’s own words are presented in the collection The World As I See It .

Einstein has also been portrayed on screen. Michael Emil played a character called “The Professor,” clearly based on Einstein, in the 1985 film Insignificance —in which alternate versions of Einstein, Marilyn Monroe , Joe DiMaggio , and Joseph McCarthy cross paths in a New York City hotel.

Walter Matthau portrayed Einstein in the fictional 1994 comedy I.Q. , in which he plays matchmaker for his niece played by Meg Ryan . Einstein was also a character in the obscure comedy films I Killed Einstein, Gentlemen (1970) and Young Einstein (1988).

A much more historically accurate depiction of Einstein came in 2017, when he was the subject of the first season of Genius , a 10-part scripted miniseries by National Geographic. Johnny Flynn played a younger version of the scientist, while Geoffrey Rush portrayed Einstein in his later years after he had fled Germany. Ron Howard was the director.

Tom Conti plays Einstein in the 2023 biopic Oppenheimer , directed by Christopher Nolan and starring Cillian Murphy as scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer during his involvement with the Manhattan Project.

- The world is a dangerous place to live; not because of the people who are evil, but because of the people who don’t do anything about it.

- A question that sometimes drives me hazy: Am I or are the others crazy?

- A person who never made a mistake never tried anything new.

- Logic will get you from A to B. Imagination will take you everywhere.

- I want to go when I want. It is tasteless to prolong life artificially. I have done my share, it is time to go. I will do it elegantly.

- If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.

- Nature shows us only the tail of the lion. But there is no doubt in my mind that the lion belongs with it even if he cannot reveal himself to the eye all at once because of his huge dimension. We see him only the way a louse sitting upon him would.

- [T]he distinction between past, present, and future is only an illusion, however persistent.

- Living in this “great age,” it is hard to understand that we belong to this mad, degenerate species, which imputes free will to itself. If only there were somewhere an island for the benevolent and the prudent! Then also I would want to be an ardent patriot.

- I, at any rate, am convinced that He [God] is not playing at dice.

- How strange is the lot of us mortals! Each of us is here for a brief sojourn; for what purpose he knows not, though he sometimes thinks he senses it.

- I regard class differences as contrary to justice and, in the last resort, based on force.

- I have never looked upon ease and happiness as ends in themselves—this critical basis I call the ideal of a pigsty. The ideals that have lighted my way, and time after time have given me new courage to face life cheerfully, have been Kindness, Beauty, and Truth.

- My political ideal is democracy. Let every man be respected as an individual and no man idolized. It is an irony of fate that I myself have been the recipient of excessive admiration and reverence from my fellow-beings, through no fault and no merit of my own.

- The most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion that stands at the cradle of true art and true science. Whoever does not know it and can no longer wonder, no longer marvel, is as good as dead, and his eyes are dimmed.

- An autocratic system of coercion, in my opinion, soon degenerates. For force always attracts men of low morality, and I believe it to be an invariable rule that tyrants of genius are succeeded by scoundrels.

- My passionate interest in social justice and social responsibility has always stood in curious contrast to a marked lack of desire for direct association with men and women. I am a horse for single harness, not cut out for tandem or team work. I have never belonged wholeheartedly to country or state, to my circle of friends, or even to my own family.

- Everybody is a genius.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Tyler Piccotti first joined the Biography.com staff as an Associate News Editor in February 2023, and before that worked almost eight years as a newspaper reporter and copy editor. He is a graduate of Syracuse University. When he's not writing and researching his next story, you can find him at the nearest amusement park, catching the latest movie, or cheering on his favorite sports teams.

Nobel Prize Winners

14 Hispanic Women Who Have Made History

Marie Curie

Martin Luther King Jr.

Henry Kissinger

Malala Yousafzai

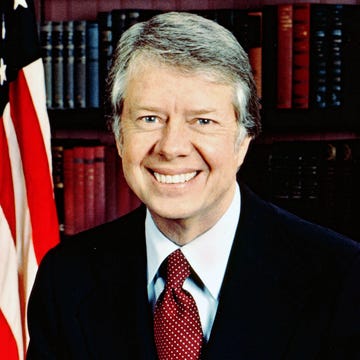

Jimmy Carter

10 Famous Poets Whose Enduring Works We Still Read

22 Famous Scientists You Should Know

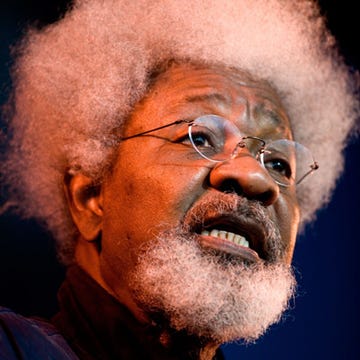

Wole Soyinka

Jean-Paul Sartre

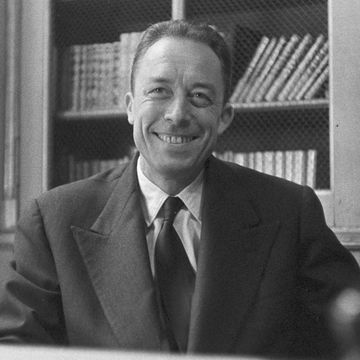

Albert Camus

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

From the archive, 7 December 1932: Einstein a go-go

Professor Einstein received his American visa today. The incident that postponed his departure was not serious. He was subjected to the same questions at the United States Consulate here that all who apply for a visa are subjected to.

These questions sound naively comic in European ears, but they are, as a rule, answered good-humouredly. The applicant is, for example, asked if he intends to over-throw the United States Constitution. If he says no - as, of course, he will - he may, if still suspect of being sympathetic to Communism or Socialism, be asked if he can give an assurance that he would not be pleased if the United States Constitution were to be over-thrown. (This question was actually put to a distinguished European applicant some weeks ago.)

Professor Einstein has visited the United States before, but hitherto the Hamburg-Amerika line obtained his visa for him. This time he was asked - like ordinary persons - to go to the United States Consulate himself. He has long been associated with organisations that are more or less associated with Communism or Socialism. He is a pacifist, and belongs to the War Resisters' movement. He has often added his signature to others in protest against non-Russian Imperialism.

When he was in all solemnity cross-examined at the United States Consulate here he got annoyed (though he had no more reason to be so than other less distinguished persons who have to go through the same formalities) and threatened to give up his journey altogether.

Some women's organisation in the United States has also interfered by asking the State Department not to let him land. When Professor Einstein heard that these busybodies had been at work he said something about "cackling geese" who wanted to save Rome once again and asked the Consular officials whether the "chicanery" that was being practised was deliberate or not. Professor Einstein has now obtained his visa, thanks, so I understand, to the intervention of the United States Embassy.

In an interview with Reuter's Berlin correspondent, Professor Einstein confessed himself more amused than offended by the opposition of the American Women's Patriotic Association to his visit to America.

"Never before, I think, have I received such an energetic rebuff at the hands of the fair sex," he said, "and not by so many all at once.

"But aren't they perfectly right, those watchful Citizens? Why should one admit to the country a man who devours capitalists with the same appetite and relish as once upon a time the monster Minotaurus in Crete devoured luscious Greek maidens, a man who in addition is so vulgar as to oppose every war except the inevitable one with his own wife?"

"Give heed, therefore, to these dear, wise, patriotic ladies and remember that the Capitol of mighty Rome was once saved by the cackling of its faithful geese."

Reuter's New York correspondent adds that Professor Nicholas Murray Butler, President of the University of Columbia, said in a reference to the action by the women's patriotic organisation: "As an American citizen, I feel so humiliated and disgraced that I have no words to express myself."

[Einstein decided not to return to Germany after his tour of America in 1933. He had spoken out against the treatment of Jews in the country, and his cottage had been raided while he was away. He renounced his German citizenship, and became an American citizen in 1940.]

- Albert Einstein

- From the Guardian archive

- US immigration

- US politics

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Book Review

- Published: October 2000

Driving Mr. Albert: A trip across America with Einstein's brain

- Steve Horwitz 1

Nature Medicine volume 6 , page 1090 ( 2000 ) Cite this article

927 Accesses

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Michael Paterniti

The real story here takes place on April 18 th , 1955 in the dank, dark morgue of Princeton Hospital. The recently deceased Albert Einstein, contemplating calculations until his final breath, lays still on the metal gurney. Dr. Thomas Harvey, then a 42 year-old chief of pathology at the hospital, enters the morgue, takes out his scalpel and goes to work on the corpse. And during the course of this routine autopsy on an anything but routine cadaver, Dr. Harvey makes a decision; one that will cast a shadow on his entire existence up to this very day. He removes Einstein's brain. And then he takes it home with him, storing it in a Tupperware container in his closet. Some branded him a hero, a man willing to risk his reputation in order to keep the brain from becoming an exhibit, something yokels gawk at when the county fair is in town. Others, especially the surviving members of the Einstein family, were not so kind.

And this is where Paterniti's cross country odyssey comes in. The idea started as an article for Harper's Weekly , an idea good enough to win him the 1998 National Magazine Award. And that article became this book. It really is a fascinating premise. A first-hand glimpse into the Yale-educated mind of one of this century's most notorious brain-nappers. And a showdown with the surviving family that wants it back. For it was the author's idea to set up the meeting between Einstein's granddaughter, a research scientist at The University of California at Berkley, and the aforementioned grave robber/pariah.

Neither participant was pleased with the idea of meeting the other, but Paterniti kept on pushing for the meeting, and finally, miraculously, it was agreed upon. A date and place were settled on; all that remained for Paterniti was the small matter of driving both Harvey and the brain across the endless interstates connecting one coast of America with the other. Against this constantly changing landscape, Paterniti ruminates. He tells us about Einstein's life, wondering what the great intellect would think if he were sitting shotgun for the drive. He worries about his own life; there's a rocky unresolved relationship waiting back home for him in Maine. He talks with Harvey, trying to mine as many yarns and tidbits as he can from the doctor's brain, especially regarding the more famous brain in the trunk. And the car drives on, building up for the climactic meeting. The custody battle for one of the world's most famous organs. An ethical debate raging between humane sentiment and the unquenchable thirst for knowledge.

But in the end, nothing happens. Harvey offers her some of the brain but Einstein's granddaughter decides she doesn't want it. And everyone goes home. “It all seems so anticlimactic, but so appropriate,” Paterniti says of the meeting. At least he got a book out of the encounter. For the reader, however, there is nothing appropriate about it. Anticlimactic endings are like taking your dog for a walk only to watch him urinate on your rug when you come back home. Not that the walk itself wasn't enjoyable, just that the end result leaves a lot to be desired.

Similarly, Paterniti's romp through the wilderness is at times both entertaining and enlightening. He does a commendable job presenting Harvey as an interesting individual, even though it's clear from the doctor's dialogue he's anything but. The historical perspective of Einstein's life is also interesting, though it occasionally feels like a crutch Paterniti leans on when the endless hours on the road leave him scrounging for pages to fill. A visit to William Burrough's home in Lawrence, Kansas is quite entertaining. An associate of Harvey's while in Kansas, one certainly wonders what a meticulous pathologist and a belligerent Morphine-addicted author could possibly talk about, except for the former explaining to the latter all the damage being done to his cerebellum.

But in the end, all those nice moments along the way fail to justify the journey. Tangents are fine, but part of their charm comes from knowing that they are deviations from the route. In Driving Mr. Albert , those tangents function as the redeemer of a failed plot and not the segue between arcs of the story. Now I'm not suggesting the author should have taken a few “creative liberties” and added a few car chases or disproportional waitresses in all-night truck stops with acoustic guitars and Grammy aspirations. But how can you be in a car with the man who has hoarded Einstein's brain in a Tupperware container for over forty years and not ask him why he took it? Or why he still has it and won't give it up to a Hospital or University for other studies? The common thread running through all scientists is a simple question. Why? And it's the same thread that binds all readers. By the end of this book, you'll know a great deal about Harvey's failed relationships, the unmistakable smell of half a dozen cheap highways motels, that Joseph Stalin founded the Moscow Brain Institute in 1926 to study Lenin's recently removed noggin. And yet you still don't know why he took the brain in the first place. It doesn't take Albert Einstein to notice how unbalanced that equation really is.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Production Editor, Nature Medicine,

Steve Horwitz

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Horwitz, S. Driving Mr. Albert: A trip across America with Einstein's brain. Nat Med 6 , 1090 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/80406

Download citation

Issue Date : October 2000

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/80406

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Albert Einstein’s legacy as a refugee

Albert Einstein is known as a genius, physicist and Nobel Laureate. While his theory of relativity changed the world, it wasn’t his only legacy. He was also a refugee and humanitarian, having inspired the founding of the organization that became the International Rescue Committee.

Fleeing Nazi persecution

Einstein was already a famous physicist by the time Adolf Hitler rose to power in 1933. As a German Jew, however, his civil liberties were suspended and he was barred from resuming his professorship at the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin. Nazis also raided his property and burned his books.

Forced from his home, Einstein sought refuge in the United States and settled in Princeton, NJ. While there were no programs or no aid agencies to ensure the safety of fellow refugees, Einstein took matters into his own hands. He and his wife made visa applications for other German Jews and personally vouched for refugees fleeing Nazi rule.

“I am privileged by fate to live here in Princeton,” he wrote to the Queen of Belgium. “In this small university town the chaotic voices of human strife barely penetrate. I am almost ashamed to be living in such peace while all the rest struggle and suffer.”

Calling for a new rescue organization

In July 1933, upon Einstein’s request , a committee of 51 American artists, intellectuals and political leaders came together to form the International Relief Association. Among them were the philosopher John Dewey, the writer John Dos Passos, and the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. Other prominent citizens, even including First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, soon joined the effort.

The committee established offices at 11 West 42 Street in New York City, across from Bryant Park and not far from the IRC's current headquarters location. Its mission, as The New York Times reported on July 24, 1933, was to "assist Germans suffering from the policies of the Hitler regime."

Article worth reading from @TIME on @AlbertEinstein ’s very special 70th birthday party and the vital work he did to support refugees—including the role he played in founding the group that would later become IRC. Learn more: https://t.co/r2tkafVRnc — IRC - International Rescue Committee (@RESCUEorg) March 16, 2020

Years later, another group of leaders formed the Emergency Rescue Committee when Paris fell to the Nazis. As the crisis deepened into World War II, the two groups merged. And so came into being the organization that would grow into today's International Rescue Committee.

IRC volunteers were among the first civilians to offer aid to Europe's displaced peoples after Germany's surrender and the official end of World War II in 1945. They later assisted refugees from Mussolini's Italy and Franco's Spain as well.

A legacy of hope