- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 6, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

John Cabot (or Giovanni Caboto, as he was known in Italy) was an Italian explorer and navigator who was among the first to think of sailing westward to reach the riches of Asia. Though the details of his life and expeditions are subject to debate, by the late 1490s he was living in England, where he gained a commission from King Henry VII to make an expedition across the Atlantic. He set sail in May 1497 and made landfall in late June, probably in modern-day Canada. After returning to England to report his success, Cabot departed on a final expedition in 1498, but was allegedly never seen again.

Giovanni Caboto was born circa 1450 in Genoa, and moved to Venice around 1461; he became a Venetian citizen in 1476. Evidence suggests that he worked as a merchant in the spice trade of the Levant, or eastern Mediterranean, and may have traveled as far as Mecca, then an important trading center for Oriental and Western goods.

He studied navigation and map-making during this period, and read the stories of Marco Polo and his adventures in the fabulous cities of Asia. Similar to his countryman Christopher Columbus , Cabot appears to have become interested in the possibility of reaching the rich gold, silk, gem and spice markets of Asia by sailing in a westward direction.

Did you know? John Cabot's landing in 1497 is generally thought to be the first European encounter with the North American continent since Leif Eriksson and the Vikings explored the area they called Vinland in the 11th century.

For the next several decades, Cabot’s exact activities are unknown; he may have been forced to leave Venice because of outstanding debts. He then spent several years in Valencia and Seville, Spain, where he worked as a maritime engineer with varying degrees of success.

Cabot may have been in Valencia in 1493, when Columbus passed through the city on his way to report to the Spanish monarchs the results of his voyage (including his mistaken belief that he had in fact reached Asia).

By late 1495, Cabot had reached Bristol, England, a port city that had served as a starting point for several previous expeditions across the North Atlantic. From there, he worked to convince the British crown that England did not have to stand aside while Spain took the lead in exploration of the New World , and that it was possible to reach Asia on a more northerly route than the one Columbus had taken.

First and Second Voyages

In 1496, King Henry VII issued letters patent to Cabot and his son, which authorized them to make a voyage of discovery and to return with goods for sale on the English market. After a first, aborted attempt in 1496, Cabot sailed out of Bristol on the small ship Matthew in May 1497, with a crew of about 18 men.

Cabot’s most successful expedition made landfall in North America on June 24; the exact location is disputed, but may have been southern Labrador, the island of Newfoundland or Cape Breton Island. Reports about their exploration vary, but when Cabot and his men went ashore, he reportedly saw signs of habitation but few if any people. He took possession of the land for King Henry, but hoisted both the English and Venetian flags.

Grand Banks

Cabot explored the area and named various features of the region, including Cape Discovery, Island of St. John, St. George’s Cape, Trinity Islands and England’s Cape. These may correspond to modern-day places located around what became known as Cabot Strait, the 60-mile-wide channel running between southwestern Newfoundland and northern Cape Breton Island.

Like Columbus, Cabot believed that he had reached Asia’s northeast coast. He returned to Bristol in August 1497 with extremely favorable reports of the exploration. Among his discoveries was the rich fishing grounds of the Grand Banks off the coast of Canada, where his crew was allegedly able to fill baskets with cod by simply dropping the baskets into the water.

John Cabot’s Final Voyage

In London in late 1497, Cabot proposed to King Henry VII that he set out on another expedition across the north Atlantic. This time, he would continue westward from his first landfall until he reached the island of Cipangu ( Japan ). In February 1498, the king issued letters patent for the second voyage, and that May Cabot set off once again from Bristol, but this time with five ships and about 300 men.

The exact fate of the expedition has not been established, but by July one of the ships had been damaged and sought anchorage in Ireland. Reportedly the other four ships continued westward. It was believed that the ships had been caught in a severe storm, and by 1499, Cabot himself was presumed to have perished at sea.

Some evidence, however, suggests that Cabot and some members of his crew may have stayed in the New World; other documents suggest that he and his crew returned to England at some point. A Spanish map from 1500 includes the northern coast of North America with English place names and the notation “the sea discovered by the English.”

What Did John Cabot Discover?

In addition to laying the groundwork for British land claims in Canada, his expeditions proved the existence of a shorter route across the northern Atlantic Ocean, which would later facilitate the establishment of other British colonies in North America .

One of John Cabot's sons, Sebastian, was also an explorer who sailed under the flags of England and Spain.

John Cabot. Royal Museums Greenwich . Who Was John Cabot? John Cabot University . John Cabot. The Canadian Encyclopedia .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Pre-Revolution Timeline - The 1400s

A decade when the men who discovered the New World began the exploration and colonization of the Americas, even if they weren't the firsts they thought they were.

More Pre-Revolution

- To the 1400s

- To the 1500s

- To the 1600s

- To the 1700s

- To the 1770s

Above: Explorer John Cabot. Image courtesy Wikipedia Commons. Right: Painting Christopher Columbus taking possession of San Salvador, Watling Island by L Prang and Co., 1893. Images courtesy Library of Congress.

Columbus and Cabot

1497 Detail

Sponsor this page for $75 per year. Your banner or text ad can fill the space above. Click here to Sponsor the page and how to reserve your ad.

1497 - Detail

May 2, 1497 - on his second voyage for england from the port of bristol, john cabot (aka giovanni, a genoese native sailing under the english flag) rediscovers the north american continent on june 24, 1497, the first european exploration of the continent since norse explorers in the 11th century. he explores the northeast coast, landing first at cape bonavista in newfoundland. they made landfall for a short period of time to raise the english flag, then explored the coast. his ship was known as the matthew of bristol..

Although the first voyage in 1496 had been a failure, England still wanted John Cabot, the Italian explorer, to sail under their flag and make discoveries for their nation. Another voyage was planned. He would set sail again to find a north passage to Asia as Columbus had most likely thought, at the time, he had found the southern route in his voyages of 1492 and 1493 . Like other explorers before and after Columbus and Cabot, that did not work out as planned. They had found America, the Caribbean islands and North America instead. Cabot, with nearly twenty shipmates on the ship Matthew of Bristol, left Bristol on May 2, 1497. One of his shipmates was likely William Weston, a merchant from Bristol who may have returned to Newfoundland two years later under Cabot's patent. The Matthew of Bristol headed due west, passing the tip of Dursey Head in southern Ireland, before shifting slightly north in a parabola before crossing the Atlantic Ocean. After over a month at sea, John Cabot arrived on June 24, 1497 near Avalon Peninsula on the southern end of Newfoundland. He would explore that eastern coast of Newfoundland, but did not explore deep inland, returning to England thereafter. The exact location of Cabot's landfall has been disputed with claims by localities in Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, St. John's Bay and Cape Bonavista, Newfoundland, and Maine that they were the true destination of Cabot's landing. Most historians seem to think that the location is either on Cape Breton Island or Newfoundland.

John day letter, 1497, cabot's second voyage, the letter below from john day, a bristol merchant in the spanish trade who knew of cabot's second voyage, was thought sent to christopher columbus, the lord grand admiral. it speaks, in as much detail as is known, about the voyage. your lordship's servant brought me your letter. i have seen its contents and i would be most desirous and most happy to serve you. i do not find the book inventio fortunata, and i thought that i (or he) find it because i wanted very much to serve you. i am sending the other book of marco polo and a copy of the land which has been found [by john cabot]. i do not send the map because i am not satisfied with it, for my many occupations forced me to make it in a hurry at the time of my departure; but from the said copy your lordship will learn what you wish to know, for in it are named the capes of the maindland and the islands, and thus you will see where land was first sighted, since most of the land was discovered after turning back. thus your lordship will know that the cape nearest to ireland is 1800 miles west of dursey head which is in ireland, and the southernmost part of the island of the seven cities is west of bordeaux river, and your lordship will know that he landed at only one spot of the mainland, near the place where land was first sighted, and they disembarked there with a crucifix and raised banners with the arms of the holy father and those of the king of england, my master; and they found tall trees of the kind masts are made, and other smaller trees, and the country is very rich in grass. in that particular spot, as i told your lordship, they found a trail that went inland, they saw a site where a fire had been made, they saw manure of animals which they thought to be farm animals, and they saw a stick half a yard long pierced at both ends, carved and painted with brazil, and by such signs they believe the land to be inhabited. since he was with just a few people, he did not dare advance inland beyond the shooting distance of a crossbow, and after taking in fresh water he returned to his ship. all along the coast they found many fish like those which in iceland are dried in the open and sold in england and other countries, and these fish are called in england 'stockfish'; and thus following the shore they saw two forms running on land one after the other, but they could not tell if they were human beings or animals; and it seemed to them that there were fields where they thought might also be villages, and they saw a forest whose foliage looked beautiful. they left england toward the end of may, and must have been on the way 35 days before sighting land; the wind was east-north-east and the sea calm going and coming back, except for one day when he ran into a storm two or three days before finding land; and going so far out, his compass needle failed to point north and marked two rhumbs below. they spent about one month discovering the coast and from the above mentioned cape of the mainland which is nearest to ireland, they returned to the coast of europe in fifteen days. they had the wind behind them, and he reached brittany because the sailors confused him, saying that he was heading too far north. from there he came to bristol, and he went to see the king to report to him all the above mentioned; and the king granted him an annual pension of twenty pounds sterling to sustain himself until the time comes when more will be known of this business, since with god's help it is hoped to push through plans for exploring the said land more thoroughly next year with ten or twelve vessels - because in his voyage he had only one ship of fifty toneles and twenty men and food for seven or eight months -- and they want to carry out this new project. it is considered certain that the cape of the said land was found and discovered in the past by the men from bristol who found 'brasil' as your lordship well knows. it was called the island of brasil, and it is assumed and believed to be the mainland that the men from bristol found. since your lordship wants information relating to the first voyage, here is what happened: he went with one ship, his crew confused him, he was short of supplies and ran into bad weather, and he decided to turn back. magnificent lord, as to other things pertaining to the case, i would like to serve your lordship if i were not prevented in doing so by occupations of great importance relating to shipments and deeds for england which must be attended to at once and which keep me from serving you: but rest assured, magnificent lord, of my desire and natural intention to serve you, and when i find myself in other circumstances and more at leisure, i will take pains to do so; and when i get news from england about the matters referred to above - for i am sure that everything has to come to my knowledge - i will inform your lordship of all that would not be prejudicial to the king my master. in payment for some services which i hope to render you, i beg your lordship to kindly write me about such matters, because the favour you will thus do me will greatly stimulate my memory to serve you in all the things that may come to my knowledge. may god keep prospering your lordship's magnificent state according to your merits. whenever your lordship should find it convenient, please remit the book or order it to be given to master george. i kiss your lordship's hands, johan day so word was spreading throughout europe of the race to discover the new world, or passages to asia, no matter what side of the topic, in this case england versus spain, that you were on. it was likely christopher columbus had the wish to stay informed about the competition and whether that competition was breaching the terms of the treaty of tordesillas , of which england was not really part of, or at least stretching it to their advantage. columbus, essentially, wanted to protect his monopoly. john cabot would take a third voyage for england , beginning may 1498. photo above: john cabot statue at cape bonavista, 2016, evan t. jones. courtesy wikipedia commons. image below: discovery of north america engraving showing john and sebastian cabot, 1855, ballou's pictorial, volume 8, page 216. courtesy library of congress. info source: department of history, university of bristol; heritagenf.ca; canadian historical review, 38 (1957), pp. 219-28; john cabot database, johncabotdatabase.weebly.com; wikipedia commons..

History Photo Bomb

Columbus meeting with the Spanish Queen. Courtesy Wikipedia Commons.

Christopher Columbus, by Ridalfo Ghirlandaio, 1520. Courtesy Wikipedia Commons.

Replica of the ship Matthew of Bristol of John Cabot. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

America's Best History where we take a look at the timeline of American History and the historic sites and national parks that hold that history within their lands. Photos courtesy of the Library of Congress, National Archives, National Park Service, americasbesthistory.com and its licensors.

If you like us, share this page on Twitter, Facebook, or any of your other favorite social media sites.

- © 2021 Americasbesthistory.com.

Template by w3layouts .

Search The Canadian Encyclopedia

Enter your search term

Why sign up?

Signing up enhances your TCE experience with the ability to save items to your personal reading list, and access the interactive map.

- MLA 8TH EDITION

- Hunter, Douglas . "John Cabot". The Canadian Encyclopedia , 19 May 2017, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot. Accessed 12 April 2024.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , 19 May 2017, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot. Accessed 12 April 2024." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- APA 6TH EDITION

- Hunter, D. (2017). John Cabot. In The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- CHICAGO 17TH EDITION

- Hunter, Douglas . "John Cabot." The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published January 07, 2008; Last Edited May 19, 2017.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published January 07, 2008; Last Edited May 19, 2017." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- TURABIAN 8TH EDITION

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "John Cabot," by Douglas Hunter, Accessed April 12, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "John Cabot," by Douglas Hunter, Accessed April 12, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Article by Douglas Hunter

Published Online January 7, 2008

Last Edited May 19, 2017

Early Years in Venice

John Cabot had a complex and shadowy early life. He was probably born before 1450 in Italy and was awarded Venetian citizenship in 1476, which meant he had been living there for at least fifteen years. People often signed their names in different ways at this time, and Cabot was no exception. In one 1476 document he identified himself as Zuan Chabotto, which gives a clue to his origins. It combined Zuan, the Venetian form for Giovanni, with a family name that suggested an origin somewhere on the Italian peninsula, since a Venetian would have spelled it Caboto. He had a Venetian wife, Mattea, and three sons, one of whom, Sebastian, rose to the rank of pilot-major of Spain for the Indies trade. Cabot was a merchant; Venetian records identify him as a hide trader, and in 1483 he sold a female slave in Crete. He was also a property developer in Venice and nearby Chioggia.

Cabot in Spain

In 1488, Cabot fled Venice with his family because he owed prominent people money. Where the Cabot family initially went is unknown, but by 1490 John Cabot was in Valencia, Spain, which like Venice was a city of canals. In 1492, he partnered with a Basque merchant named Gaspar Rull in a proposal to build an artificial harbour for Valencia on its Mediterranean coast. In April 1492, the project captured the enthusiasm of Fernando (Ferdinand), king of Aragon and husband of Isabel, queen of Castille, who together ruled what is now a unified Spain. The royal couple had just agreed to send Christopher Columbus on his now-famous voyage to the Americas. In the autumn of 1492, Fernando encouraged the governor-general of Valencia to find a way to finance Cabot’s harbour scheme. However, in March 1493, the council of Valencia decided it could not fund Cabot’s plan. Despite Fernando’s attempt to move the project forward that April, the scheme collapsed.

Cabot disappeared from the historical record until June 1494, when he resurfaced in another marine engineering plan dear to the Spanish monarchs. He was hired to build a fixed bridge link in Seville to its maritime centre, the island of Triana in the Guadalquivir River, which otherwise was serviced by a troublesome floating one. Though Columbus had reached the Americas, he believed he had found land on the eastern edge of Asia, and Seville had been chosen as the headquarters of what Spain imagined was a lucrative transatlantic trade route. Cabot’s assignment thus was an important one, but something went wrong. In December 1494, a group of leading citizens of Seville gathered, unhappy with Cabot’s lack of progress, given the funds he had been provided. At least one of them thought he should be banished from the city. By then, Cabot probably had left town.

Cabot in England

Following the demise of Cabot’s Seville bridge project, the marine engineer again disappeared from the historical record. In March 1496 he resurfaced, this time as the commander of a proposed westward voyage under the flag of the King of England, Henry VII. Although there is no documentary proof, during Cabot’s absence from the historical record, between April 1493 and June 1494, he could have sailed with Columbus’s second voyage to the Caribbean. Most of the names of the over 1,000 people who accompanied Columbus weren’t recorded; however, Cabot could have been among the marine engineers on the voyage’s 17 ships who were expected to construct a harbour facility in what is now Haiti. Had Cabot been present on this journey, Henry VII would have had some basis to believe the would-be Venetian explorer could make a similar voyage to the far side of the Atlantic. It would help explain why Henry VII hired Cabot, a foreigner with a problematic résumé and no known nautical expertise, to make such a journey.

On 5 March 1496, Henry awarded Cabot and his three sons a generous letters patent, a document granting them the right to explore and exploit areas unknown to Christian monarchs. The Cabots were authorized to sail to “all parts of the eastern, western and northern sea, under our banners, flags and ensigns,” with as many as five ships, manned and equipped at their own expense. The Cabots were to “find, discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of heathens and infidels, in whatsoever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians.” The Cabots would serve as Henry’s “vassals, and governors lieutenants and deputies” in whatever lands met the criteria of the patent, and they were given the right to “conquer, occupy and possess whatsoever towns, castles, cities and islands by them discovered.” With the letters patent, the Cabots could secure financial backing. Two payments were made in April and May 1496 to John Cabot by the House of Bardi (a family of Florentine merchants) to fund his search for “the new land,” suggesting his investors thought he was looking for more than a northern trade route to Asia.

First Voyage (1496)

Cabot’s first voyage departed Bristol, England, in 1496. Sailing westward in the north Atlantic was no easy task. The prevailing weather patterns track from west to east, and ships of Cabot’s time could scarcely sail toward the wind. No first-hand accounts of Cabot’s first attempt to sail west survive. Historians only know that it was a failure, with Cabot apparently rebuffed by stormy weather.

Second Voyage (1497)

Cabot mounted a second attempt from Bristol in May 1497, using a ship called the Matthew . It may have been a happy coincidence that its name was the English version of Cabot’s wife’s name, Mattea. There are no records of the ship’s individual crewmembers, and all the accounts of the voyage are second-hand — a remarkable lack of documentation for a voyage that would be the foundation of England’s claim to North America.

Historians have long debated exactly where Cabot explored. The most authoritative report of his journey was a letter by a London merchant named Hugh Say. Written in the winter of 1497-98, but only discovered in Spanish archives in the mid-1950s, Say’s letter (written in Spanish) was addressed to a “great admiral” in Spain who may have been Columbus.

The rough latitudes Say provided suggest Cabot made landfall around southern Labrador and northernmost Newfoundland , then worked his way southeast along the coast until he reached the Avalon Peninsula , at which point he began the journey home. Cabot led a fearful crew, with reports suggesting they never ventured more than a crossbow’s shot into the land. They saw two running figures in the woods that might have been human or animal and brought back an unstrung bow “painted with brazil,” suggesting it was decorated with red ochre by the Beothuk of Newfoundland or the Innu of Labrador. He also brought back a snare for capturing game and a needle for making nets. Cabot thought (wrongly) there might be tilled lands, written in Say’s letter as tierras labradas , which may have been the source of the name for Labrador. Say also said it was certain the land Cabot coasted was Brasil, a fabled island thought to exist somewhere west of Ireland.

Others who heard about Cabot’s voyage suggested he saw two islands, a misconception possibly resulting from the deep indentations of Newfoundland’s Conception and Trinity Bays, and arrived at the coast of East Asia. Some believed he had reached another fabled island, the Isle of Seven Cities, thought to exist in the Atlantic.

There were also reports Cabot had found an enormous new fishery. In December 1497, the Milanese ambassador to England reported hearing Cabot assert the sea was “swarming with fish, which can be taken not only with the net, but in baskets let down with a stone.” The fish of course were cod , and their abundance on the Grand Banks later laid the foundation for Newfoundland’s fishing industry.

Third Voyage (1498)

Henry VII rewarded Cabot with a royal pension on December 1497 and a renewed letters patent in February 1498 that gave him additional rights to help mount the next voyage. The additional rights included the ability to charter up to six ships as large as 200 tons. The voyage was again supposed to be mounted at Cabot’s expense, although the king personally invested in one participating ship. Despite reports from the 1497 voyage of masses of fish, no preparations were made to harvest them.

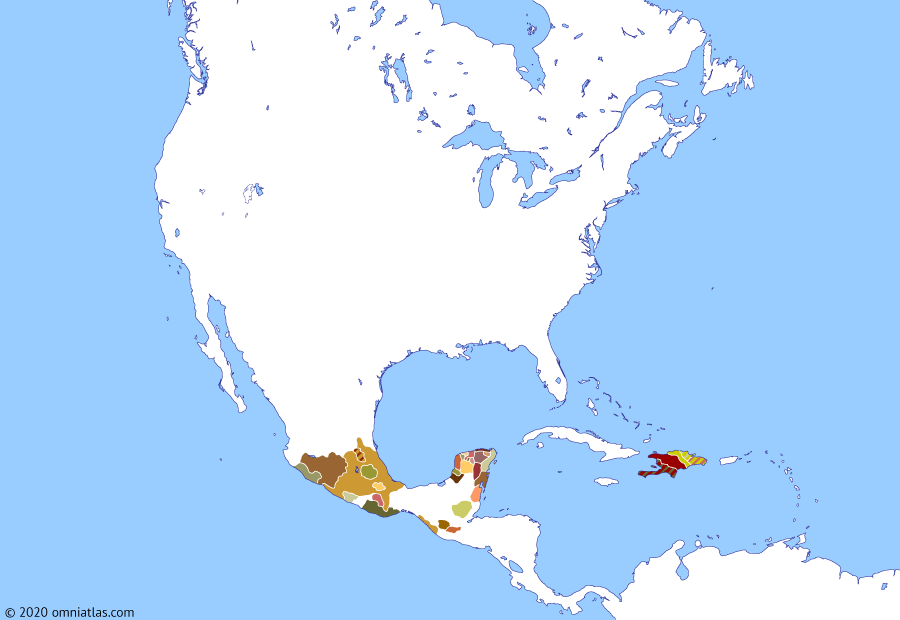

A flotilla of probably five ships sailed in early May. What became of it remains a mystery. Historians long presumed, based on a flawed account by the chronicler Polydore Vergil, that all the ships were lost, but at least one must have returned. A map made by Spanish cartographer Juan de la Cosa in 1500 — one of the earliest European maps to incorporate the Americas — included details of the coastline with English place names, flags and the notation “the sea discovered by the English.” The map suggests Cabot’s voyage ventured perhaps as far south as modern New England and Long Island.

Cabot’s royal pension did continue to be paid until 1499, but if he was lost on the 1498 voyage, it may only have been collected in his absence by one of his sons, or his widow, Mattea.

Despite being so poorly documented, Cabot’s 1497 voyage became the basis of English claims to North America. At the time, the westward voyages of exploration out of Bristol between 1496 and about 1506, as well as one by Sebastian Cabot around 1508, were probably considered failures. Their purpose was to secure trade opportunities with Asia, not new fishing grounds, which not even Cabot was interested in, despite praising the teeming schools. Instead of trade with Asia, Cabot and his Bristol successors found an enormous land mass blocking the way and no obvious source of wealth.

- Newfoundland and Labrador

Further Reading

Douglas Hunter, The Race to the New World: Christopher Columbus, John Cabot and a Lost History of Discovery (2012).

External Links

Heritage Newfoundland and Labrador A biography of John Cabot from this site sponsored by Memorial University.

Dictionary of Canadian Biography An account of John Cabot’s life from the Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

Recommended

Giovanni da verrazzano, jacques cartier.

Sir Humphrey Gilbert: Elizabethan Explorer

The UK National Charity for History

Password Sign In

Become a Member | Register for free

The Voyages of John and Sebastian Cabot

Classic Pamphlet

- Add to My HA Add to folder Default Folder [New Folder] Add

Discovering North America

Historians have debated the voyages of John and Sebastian Cabot who first discovered North America under the reign of Henry VII. The primary question was who [John or Sebastian] was responsible for the successful discovery . A 1516 account stated Sebastian Cabot sailed from Bristol to Cathay, in the service of Henry VII; environmental hardships had compelled Sebastian to travel to lower latitudes that led to the subsequent discovery of eastern North America. Still, early writers did not provide sufficient details of the expedition creating a number of discrepancies that undermine its validity.

In 1582, Richard Hakluyt printed letters that were granted on March 5, 1496 on behalf of King Henry VII to John Cabot that asked him to discover unknown lands in an effort to annex them for the Crown and monopolize English trade. This account, in contrast, indicated that John Cabot actually led the journey with his son Sebastian as his subordinate. Despite these opposing sources, it was not until the 19th century that historians began rejecting Sebastian as the primary discoverer of North America largely due to Richard Biddle who had published a Memoir of Sebastian Cabot in 1831. This memoir collated the sixteenth century writers with documents asserting Sebastian’s father, John Cabot, was merely a sleeping partner and an elderly merchant who did not go to sea—rendering Sebastian as the leader of the journey. Eventually, important documents emerged from unexamined archives of European states that almost irrefutably debunked Sebastian as the captain...

This resource is FREE for Student HA Members .

Non HA Members can get instant access for £3.49

Add to Basket Join the HA

- Documentary

- Entertainment

- Building Big

- How It’s Made

- Monarchs and Rulers

- Travel & Exploration

Who was John Cabot and What Happened to His Final Expedition?

John Cabot was an explorer and navigator who was the first European since Leif Erikson in the eleventh century to set foot on North American soil. So what is John Cabot best known for? Did Cabot discover America? This is the story of Cabot’s last voyage.

John Cabot was born Giovanni Caboto in Genoa around or perhaps slightly earlier than 1450 and it’s believed he moved to Venice in 1461. There, he read of Marco Polo’s adventures along the Silk Road in the late thirteenth century and wanted to explore the wonderful cities in China, Persia, India and Japan for himself. Lands he believed were rich with gold, spices and exotic luxuries.

While he was working for a Venetian mercantile company in the early 1480s, he travelled to the eastern Mediterranean where goods from the East and West were freely traded. It was on these travels that he learned navigational skills and, it is assumed, he got the idea that a shorter route to Asia would be to go west from Europe.

Zuan Cabotto, the Venetian version of Giovanni Caboto, was mentioned in several documents in Venice in the 1480s. He married Mattea around 1481 and by 1484 they had three sons, Ludovico, Sebastian and Sancto.

John Cabot’s whereabouts over the next decade are a matter of conjecture. He may have fled Venice as an insolvent debtor around 1488 and possibly spent time in Valencia and Seville in Spain. He then came to England sometime in 1495 and went to Bristol.

Like Christopher Columbus, he believed the world was much smaller than it actually is, and he set sail from England in May 1497 believing he would find the silk and spices of Asia just a few thousand miles west. In fact he landed in North America.

The First Cabot Expedition

John Cabot (known in Italian as Giovanni Caboto) (Photo: UniversalImagesGroup via Getty Images)

Undertaking long expensive journeys in those days required funding and royal patronage and Cabot secured both.

The money came from a number of wealthy merchants in Bristol as well as from his Italian connections, most notably Brother Giovanni Antonio de Carbonariis, a Milanese diplomat and the Pope’s tax collector in England.

With the money secure, he needed the blessing of King Henry VII, who Cabot convinced by arguing that England didn’t have to stand by and watch idly while the Spanish explored the New World unopposed.

On March 5 1496 the king issued Letters Patent. This is a legally-binding document that allowed Cabot to set sail under the English flag. He was given the right to ‘discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of heathens and infidels, in whatsoever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians.’

In the summer of 1496 he attempted the voyage. However, according to a contemporary report, a letter written by a Bristol merchant to – it is believed – Christopher Columbus, ‘he went with one ship, his crew confused him, he was short of supplies and ran into bad weather, and he decided to turn back.’

Cabot’s Second Voyage

John Cabot Arrives In Newfoundland, Canada (Photo: Stock Montage via Getty Images)

On May 2 1497, Giovanni Caboto – or John Cabot as he was now known – set sail from Bristol on a small ‘fifty tons burden’ ship called The Mathew with around eighteen men. This time the voyage would be a success.

They made landfall in North America on June 24, although the precise location has been disputed for five centuries. Some say they landed at the southernmost tip of Labrador on Newfoundland – so called, allegedly, as one sailor proclaimed a ‘new found land’ – others suggest Cape Breton Island on Nova Scotia or even the Maine coast.

When they went ashore, there was evidence of habitation but no people. John Cabot took possession of the land for King Henry VII, planting the flags of England and Venice.

Like Columbus who ended up in the West Indies, John Cabot believed, quite wrongly as it transpired, he had found the northeast coast of Asia.

Cabot and his men returned to Bristol in August 1497 with reports of an extremely successful voyage, but that wasn’t enough. He wanted to return, and this time he set his sights further. Much further.

The Mystery of Cabot’s Last Voyage

John Cabot is thought to have been lost at sea (Photo: Corbis Historical via Getty Images)

On February 3 1498, Cabot was issued with new Letters Patent from the king and soon after, left Bristol with five ships and around 300 men.

The aim was to retrace his previous steps but to continue west from his first landing point until he reached the island Marco Polo named Cipangu. Today we know it as Japan, and any modern world map will tell you that the journey west from Bristol to Japan is virtually impossible.

Whichever way he was planning to go, north via Canada or South around the southern tip of Chile, is in excess of 20,000 miles, in February, through the Arctic Ocean or the Southern Ocean… As we say, virtually impossible.

The five ships of Cabot’s last voyage were equipped with a years’ worth of food and supplies. It’s believed one ship got damaged and turned back to Ireland, with the others sailing forth into the unknown.

That’s the last that anyone recorded of Cabot’s final voyage. To this day, no-one knows what became of the ships or the men. Accounts vary as to what may have happened. Some say they were caught in a storm and all perished. Others suggest they made it to the continental USA and stayed there. Yet more suggest they all returned to the UK.

By 1500, John Cabot was presumed dead.

One of the men who was scheduled to sail in this final expedition, Lancelot Thirkill, was recorded as living in London in 1501. Maybe he went and came back. Maybe he didn’t go at all.

Did John Cabot Discover America?

Leif Erikson Exploring Greenland (Photo: Bettmann via Getty Images)

The short answer is no. Norse explorer Leif Erikson settled in Vinland – modern day Newfoundland – around 1000 AD and there were indigenous populations in what we now know as the United States from about 15,000 BC.

While he can’t lay claim to the discovery of America, the Cabot discoveries were historically important in that they laid the groundwork for English expansion into North American lands. In addition they established quicker and shorter routes across the Atlantic Ocean which facilitated the English colonisation of North America.

You May Also Like

The legend of aztlan: mythical origin of aztec civilisation, unraveling the secrets of the betz mystery sphere, the beast of gevaudan: france’s legendary nightmare, the piltdown man hoax: unravelling a scientific scandal, explore more, adam’s calendar: humanity’s oldest timekeeper, olivier levasseur: the pirate’s code and buried treasure, skyquake: the mysterious sounds from the sky, who started april fools’ day, zosimos of panopolis: alchemy and the quest for knowledge, deciphering the sator square: ancient puzzle or mysterious magic.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Native Americans

- Age of Exploration

- Revolutionary War

- Mexican-American War

- War of 1812

- World War 1

- World War 2

- Family Trees

- Explorers and Pirates

John Cabot Facts, Voyage, and Accomplishments

Published: Jul 25, 2016 · Modified: Nov 11, 2023 by Russell Yost · This post may contain affiliate links ·

John Cabot was a Genoese navigator and explorer whose 1497 discovery of parts of North America under the commission of Henry VII of England is commonly held to have been the first European exploration of the mainland of North America since the Norse Vikings' visits to Vinland in the eleventh century.

It would also be one of the last times, until Queen Elizabeth, that England would set foot in the New World.

John Cabot Facts: Early Life

John cabot facts: england and expeditions, john cabot facts: historical thoughts, online resources.

He may have been born slightly earlier than 1450, which is the approximate date most commonly given for his birth.

In 1471, Caboto was accepted into the religious confraternity of St John the Evangelist. Since this was one of the city's prestigious confraternities, his acceptance suggests that he was already a respected member of the community.

Following his gaining full Venetian citizenship in 1476, Caboto would have been eligible to engage in maritime trade, including the trade to the eastern Mediterranean that was the source of much of Venice's wealth.

A 1483 document refers to his selling a slave in Crete whom he had acquired while in the territories of the Sultan of Egypt, which then comprised most of what is now Palestine, Syria, and Lebanon.

Cabot is mentioned in many Venetian records of the 1480s. These indicate that by 1484, he was married to Mattea and already had at least two sons.

Cabot's sons are Ludovico, Sebastian, and Sancto. The Venetian sources contain references to Cabot's being involved in house building in the city. He may have relied on this experience when seeking work later in Spain as a civil engineer.

Cabot appears to have gotten into financial trouble in the late 1480s and left Venice as an insolvent debtor by 5 November 1488.

He moved to Valencia, Spain, where his creditors attempted to have him arrested. While in Valencia, John Cabot proposed plans for improvements to the harbor. These proposals were rejected.

Early in 1494, he moved on to Seville, where he proposed, was contracted to build, and, for five months, worked on the construction of a stone bridge over the Guadalquivir River. This project was abandoned following a decision of the City Council on 24 December 1494.

After this, Cabot appears to have sought support from the Iberian crowns of Seville and Lisbon for an Atlantic expedition before moving to London to seek funding and political support. He likely reached England in mid-1495.

Like other Italian explorers, including Christopher Columbus , Cabot led an expedition on commission to another European nation, in his case, England.

Cabot planned to depart to the west from a northerly latitude where the longitudes are much closer together and where, as a result, the voyage would be much shorter. He still had an expectation of finding an alternative route to China.

On 5 March 1496, Henry VII gave Cabot and his three sons letters patent with the following charge for exploration:

...free authority, faculty, and power to sail to all parts, regions, and coasts of the eastern, western, and northern sea, under our banners, flags, and ensigns, with five ships or vessels of whatsoever burden and quality they may be, and with so many and with such mariners and men as they may wish to take with them in the said ships, at their own proper costs and charges, to find, discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of heathens and infidels, in whatsoever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians.

Those who received such patents had the right to assign them to third parties for execution. His sons are believed to have still been under the age of 18

Cabot went to Bristol to arrange preparations for his voyage. Bristol was the second-largest seaport in England. From 1480 onward, it supplied several expeditions to look for Hy-Brazil. According to Celtic legend, this island lay somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean. There was a widespread belief among merchants in the port that Bristol men had discovered the island at an earlier date but then lost track of it.

Cabot's first voyage was little recorded. Winter 1497/98 letter from John Day (a Bristol merchant) to an addressee believed to be Christopher Columbus refers briefly to it but writes mostly about the second 1497 voyage. He notes, "Since your Lordship wants information relating to the first voyage, here is what happened: he went with one ship, his crew confused him, he was short of supplies and ran into bad weather, and he decided to turn back." Since Cabot received his royal patent in March 1496, it is believed that he made his first voyage that summer.

What is known as the "John Day letter" provides considerable information about Cabot's second voyage. It was written during the winter of 1497/8 by Bristol merchant John Day to a man who is likely Christopher Columbus . Day is believed to have been familiar with the key figures of the expedition and thus able to report on it.

If the lands Cabot had discovered lay west of the meridian laid down in the Treaty of Tordesillas, or if he intended to sail further west, Columbus would likely have believed that these voyages challenged his monopoly rights for westward exploration.

Leaving Bristol, the expedition sailed past Ireland and across the Atlantic, making landfall somewhere on the coast of North America on 24 June 1497. The exact location of the landfall has long been disputed, with different communities vying for the honor.

Cabot is reported to have landed only once during the expedition and did not advance "beyond the shooting distance of a crossbow." Pasqualigo and Day both state that the expedition made no contact with any native people; the crew found the remains of a fire, a human trail, nets, and a wooden tool.

The crew appeared to have remained on land just long enough to take on fresh water; they also raised the Venetian and Papal banners, claiming the land for the King of England and recognizing the religious authority of the Roman Catholic Church. After this landing, Cabot spent some weeks "discovering the coast," with most "discovered after turning back."

On return to Bristol, Cabot rode to London to report to the King.

On 10 August 1497, he was given a reward of £10 – equivalent to about two years' pay for an ordinary laborer or craftsman. The explorer was feted; Soncino wrote on 23 August that Cabot "is called the Great Admiral and vast honor is paid to him and he goes dressed in silk and these English run after him like mad."

Such adulation was short-lived, for over the next few months, the King's attention was occupied by the Second Cornish Uprising of 1497, led by Perkin Warbeck.

Once Henry's throne was secure, he gave more thought to Cabot. On 26 September, just a few days after the collapse of the revolt, the King made an award of £2 to Cabot. In December 1497, the explorer was awarded a pension of £20 per year, and in February 1498, he was given a patent to help him prepare a second expedition.

In March and April, the King also advanced a number of loans to Lancelot Thirkill of London, Thomas Bradley, and John Cair, who were to accompany Cabot's new expedition.

Cabot departed with a fleet of five ships from Bristol at the beginning of May 1498, one of which had been prepared by the King. Some of the ships were said to be carrying merchandise, including cloth, caps, lace points, and other "trifles."

This suggests that Cabot intended to engage in trade on this expedition. The Spanish envoy in London reported in July that one of the ships had been caught in a storm and been forced to land in Ireland but that Cabot and the other four ships had continued on.

For centuries, no other records were found (or at least published) that relate to this expedition; it was long believed that Cabot and his fleet were lost at sea. But at least one of the men scheduled to accompany the expedition, Lancelot Thirkill of London, is recorded as living in London in 1501.

The historian Alwyn Ruddock worked on Cabot and his era for 35 years. She had suggested that Cabot and his expedition successfully returned to England in the spring of 1500. She claimed their return followed an epic two-year exploration of the east coast of North America, south into the Chesapeake Bay area and perhaps as far as the Spanish territories in the Caribbean. Ruddock suggested Fr. Giovanni Antonio de Carbonariis and the other friars who accompanied the 1498 expedition had stayed in Newfoundland and founded a mission.

If Carbonariis founded a settlement in North America, it would have been the first Christian settlement on the continent and may have included a church, the only medieval church to have been built there.

The Cabot Project at the University of Bristol was organized in 2009 to search for the evidence on which Ruddock's claims rest, as well as to undertake related studies of Cabot and his expeditions.

The lead researchers on the project, Evan Jones and Margaret Condon, claim to have found further evidence to support aspects of Ruddock's case, particularly in relation to the successful return of the 1498 expedition to Bristol.

They have located documents that appear to place John Cabot in London by May 1500 but have yet to publish their documentation.

- John Cabot's Wikipedia Page

- Cabot Project

- Find a Grave: John Cabot Memorial

- John Cabot Study Guide

- The History Junkie's Guide to Famous Explorers

- The History Junkie's Guide to Colonial America

World History Edu

- Famous Explorers

John Cabot: History and Major Accomplishment of the Renowned Italian Explorer

by World History Edu · February 6, 2024

John Cabot, born Giovanni Caboto around 1450 in Genoa, Italy, was an Italian explorer and navigator known for his voyages across the Atlantic Ocean under the commission of Henry VII of England. This exploration led to the European discovery of parts of North America, believed to be the earliest since the Norse visits to Vinland in the eleventh century.

John Cabot, for example, was an Italian explorer known for his 1497 voyage to North America, where, though mistaking the land for Asia, he reached Newfoundland. Cabot is thought to have died only a few years later, possibly on a similar voyage. Image: A painting of Cabot by Italian painter Giustino Menescardi.

This is the story of the famed Italian explorer.

Birth and Early Life

His exact birth date is uncertain, but he is thought to have been born to a spice merchant, Giulio Caboto, and his wife; this background likely instilled in Cabot a curiosity about foreign lands and the lucrative spice trade.

Cabot’s early life is shrouded in mystery, but it is believed that he received a decent education, likely in navigation and seamanship, given Genoa’s prominence as a maritime republic.

By the late 1470s, Cabot had moved to Venice, a leading maritime power with extensive trade networks, where he became a citizen in 1476. During his time in Venice, he likely engaged in trade in the Eastern Mediterranean, gaining invaluable experience and knowledge about the trade routes.

Who were the 10 Most Influential Explorers of the Age of Discovery?

Time in England

By the 1480s, Cabot had moved to Spain and later to England, where he settled in Bristol, a leading maritime center. Bristol merchants had been interested in finding a direct trade route to Asia by sailing westward, and Cabot proposed that by sailing across the North Atlantic, one could reach Asia quicker and more safely than by the traditional routes around Africa.

Newfoundland Arrival

In 1496, Cabot received a royal patent from King Henry VII, which authorized him to search for unknown lands to establish trade. This patent was a significant milestone, as it marked England’s entry into the era of transatlantic exploration. The following year, Cabot set sail with one ship, the Matthew, and a crew of about 20 men. The exact course of his 1497 voyage is the subject of much debate, but it is widely accepted that he landed on the coast of what is today known as Newfoundland or Cape Breton Island, claiming the land for the English crown.

Significance of Cabot’s voyage

Cabot’s 1497 voyage was significant for several reasons. Firstly, it is believed to have been the first European exploration of the North American mainland since the Norse. Secondly, it laid the groundwork for future English claims in North America, which would eventually lead to the establishment of English colonies in the New World.

Despite the historical significance of his 1497 voyage, details about Cabot’s life and subsequent expeditions remain scarce and sometimes contradictory. A second expedition is believed to have taken place in 1498, with Cabot commanding a larger fleet aimed at establishing a base in the New World and further exploring the coast. However, the fate of this expedition is unclear, with some accounts suggesting that Cabot and his fleet were lost at sea, while others propose that he returned to England but fell out of favor.

Did you know…?

- Giovanni Caboto, known as John Cabot in English, reflects a historical European practice of adapting names to local languages in documents, a tradition often embraced by individuals themselves, leading to variations like Zuan Caboto in Venetian and Jean Cabot in French.

- In Venice, Cabot used “Zuan Chabotto,” a local form of John. He maintained this version in England among Italians, while his Italian banker in London uniquely referred to him as “Giovanni” in contemporary documents.

- For the 500th anniversary of Cabot’s expedition, Cape Bonavista, Newfoundland was officially recognized by Canada and the UK as his first landing site, despite other proposed locations for his historic North American arrival.

Cabot’s legacy is complex; while he did not establish lasting European settlements in North America, his voyages opened the North Atlantic and contributed to the European understanding of the New World’s geography. His expeditions under the English flag were among the first steps in the long process that eventually led to the establishment of British North America.

In the centuries following Cabot’s voyages, his achievements were somewhat overshadowed by those of other explorers such as Christopher Columbus and Vasco da Gama .

However, the 19th and 20th centuries saw a resurgence of interest in Cabot as historians and scholars began to recognize his contributions to the Age of Discovery.

Today, John Cabot is celebrated as a pioneering figure in Atlantic exploration, with monuments, geographical locations, and institutions named in his honor, reflecting the enduring impact of his voyages on the history of exploration and the eventual shaping of the modern world.

Most Famous Explorers of All Time

Frequently Asked Questions about John Cabot and his Voyages

These FAQs aim to provide a brief overview of some of the most common questions related to John Cabot and his exploratory voyages to North America.

When was John Cabot born?

Cabot’s birth might predate the commonly cited year of 1450, suggesting an earlier timeline. His 1471 admission into Venice’s esteemed Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista indicates his early respect and standing within the community, reflecting his societal position.

Why was Vasco da Gama determined to open trade route to the east?

Who were john cabot’s parents.

Cabot, son of Giulio Caboto, with a brother named Piero, had his birthplace debated between Gaeta, Province of Latina, and Castiglione Chiavarese, Province of Genoa, Italy.

John Cabot, originally Giovanni Caboto, was an Italian navigator and explorer who is credited with the discovery of parts of North America under the commission of Henry VII of England in 1497.

What did John Cabot discover?

John Cabot is best known for his 1497 voyage across the Atlantic Ocean, where he reached what is believed to be the coast of Newfoundland, thus marking one of the earliest European explorations of the North American continent since the Norse.

Why did John Cabot explore?

Cabot was motivated by the desire to find a westward route to Asia to access its lucrative spice trade, bypassing the overland routes that were controlled by the Ottomans.

Was John Cabot the first to discover North America?

No, Cabot was not the first. The Norse, led by Leif Eriksson, had reached North America, specifically Vinland, which is thought to be modern-day Newfoundland, around the year 1000. However, Cabot’s voyage in 1497 is significant as it led to the European rediscovery of the continent.

Who was Barentsz and how significant was his exploration of the Arctic?

Did john cabot think he had found asia.

Yes, like many explorers of his time, Cabot believed that the lands he had found were the eastern outskirts of Asia. The concept of the “New World” as separate continents of North and South America was not widely recognized at the time.

What happened to John Cabot after his voyages?

The details surrounding Cabot’s fate after his voyages are unclear and subject to debate. He is believed to have embarked on a second voyage in 1498, from which he may not have returned, possibly dying during this expedition.

Cabot’s voyages were significant because they were among the first to suggest the existence of a northwestern route to Asia and they laid the groundwork for future European exploration and eventual colonization of the Americas. Image: Sculpture of Giovanni Caboto, crafted by Italian artits Augusto Benvenuti in 1881.

Did John Cabot have any interaction with indigenous peoples?

There is no conclusive evidence that Cabot directly interacted with indigenous peoples during his voyages. The records of his 1497 voyage are sparse, and if there were interactions, they were not well-documented.

What flag did John Cabot sail under?

John Cabot sailed under the flag of England, having been granted a royal patent by King Henry VII, which authorized him to explore “new lands” on behalf of the English crown.

Tags: 15th Century Explorers Age of Discovery Canada Henry VII of England Italian explorers John Cabot Newfoundland North America

You may also like...

February 9, 2024

February 3, 2024

Who was the Chinese Admiral Zheng He?

February 16, 2024

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Next story The birth of the Gorgons according to Hesiod’s Theogony

- Previous story What transpired at the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403?

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

Mount Olympus in Greek Mythology

Life of Saint Barbara and why she was beheaded by her own father

Most Important Accomplishments of Lee Kuan Yew, Founding Father of Modern Singapore

Edward the Black Prince: History, Accomplishments, & Major Facts

What Happened to the Muslim Majority of Portugal and Spain?

Greatest African Leaders of all Time

Queen Elizabeth II: 10 Major Achievements

Donald Trump’s Educational Background

Donald Trump: 10 Most Significant Achievements

8 Most Important Achievements of John F. Kennedy

Odin in Norse Mythology: Origin Story, Meaning and Symbols

Ragnar Lothbrok – History, Facts & Legendary Achievements

9 Great Achievements of Queen Victoria

12 Most Influential Presidents of the United States

Most Ruthless African Dictators of All Time

Kwame Nkrumah: History, Major Facts & 10 Memorable Achievements

Greek God Hermes: Myths, Powers and Early Portrayals

8 Major Achievements of Rosa Parks

How did Captain James Cook die?

10 Most Famous Pharaohs of Egypt

Kamala Harris: 10 Major Achievements

The Exact Relationship between Elizabeth II and Elizabeth I

Poseidon: Myths and Facts about the Greek God of the Sea

Nile River: Location, Importance & Major Facts

Importance and Major Facts about Magna Carta

- Adolf Hitler Alexander the Great American Civil War Ancient Egyptian gods Ancient Egyptian religion Aphrodite Apollo Athena Athens Black history Carthage China Civil Rights Movement Constantine the Great Constantinople Egypt England France Germany Ghana Hera Horus India Isis John Adams Julius Caesar Loki Military Generals Military History Nobel Peace Prize Odin Osiris Pan-Africanism Queen Elizabeth I Ra Ragnarök Religion Set (Seth) Soviet Union Thor Timeline Women’s History World War I World War II Zeus

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot)

Introduction, general overviews.

- Encyclopedia Entries

- Birth and Early Life

- The 1496 Voyage

- The 1497 Voyage

- The 1498 Voyage

- Funding of Voyages

- Sebastiano Caboto, Son (d. 1557)

- Maps and Cartography

- Early English Voyages (pre-Caboto)

- Later English Voyages (post-Caboto)

- Internet Resources

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Maps in the Atlantic World

- Pre-Columbian Transatlantic Voyages

- Tudor and Stuart Britain in the Wider World, 1485–1685

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- European Enslavement of Indigenous People in the Americas

- Nobility and Gentry in the Early Modern Atlantic World

- Phillis Wheatley

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot) by Francesco Guidi Bruscoli LAST MODIFIED: 29 November 2022 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199730414-0374

Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot, b. c. 1450–d. c . 1500) was an Italian navigator credited to be the first European to set foot in North America after the Norse, during an expedition of 1497 carried out under the English flag. Little is known about his origins, although he certainly took up Venetian citizenship, implying origin elsewhere. He was known as Zuan Chabotto in Venice, and he presented himself as a Venetian when he moved to England. As early as the late sixteenth/early seventeenth century, Richard Hakluyt and Samuel Purchas praised Caboto’s pioneering “discoveries” (despite some confusion between the role of Giovanni and that of his son). But it was especially from 1897 (the 400th anniversary of his landing) that—following new archival discoveries—his achievement as an explorer was celebrated. Until then his role had been overshadowed by that of his son Sebastian, who in part because of the influence of Sebastian’s own accounts, had been credited with being in charge of the voyages. It was in particular Henry Harrisse, in John Cabot, the Discoverer of North America, and Sebastian his Son: A Chapter of the Maritime History of England under the Tudors, 1496–1557 (London: Stevens, 1896), who revived the figure of Giovanni, while at the same time lambasting Sebastiano as an impostor. In the same period, more or less co-incident with the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s 1492 voyage, general interest in voyages of exploration revived also in Italy, although studies on Caboto mainly focused on his origin. In the 1940s new documentary discoveries threw some light on Caboto’s years both in Spain and in Venice. In the 1950s the discovery of John Day’s letter in the Simancas archive stimulated a new wave of studies, for the letter hints at a previously unknown voyage of 1496, provides many technical details concerning the 1497 voyage (thus opening debate on the latitude of the landing), and alludes to earlier discoveries. The most important study, still a crucial reference for studies on Caboto, is James A. Williamson’s The Cabot Voyages and Bristol Discovery under Henry VII (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press/Hakluyt Society, 2nd Series, vol. 120, 1962). For the 500th anniversary of the landing, in 1997, several conferences were organized, in many cases leading to the publication of proceedings. The most relevant recent advances, however, have been made within the framework of the Cabot Project, based at the University of Bristol. Following unpublished leads left behind by deceased scholar Alwyn Ruddock, Evan Jones and others have proposed new hypotheses, and uncovered the first known financiers of the 1497 voyage.

The volume of literature on Giovanni Caboto is overwhelming. New waves of publications coincided either with the celebration of anniversaries (especially in 1897 and 1997) or with the discovery of new documents, as summarized by Luzzana Caraci 1999 . In Italian the first analytical study of Caboto’s achievements was Almagià 1937 . In English the classic work (still seminal) is Williamson 1962 . Countless scholars and writers have published on Caboto’s voyages before and since. Among the most recent academic publications, Pope 1997 discusses at length the possible landfall of the 1497 voyage, still claimed by various Canadian regions, including Cape Bonavista (Newfoundland) and Cape Breton (Nova Scotia), whereas Jones 2008 sets the agenda for new streams of research to be undertaken in order to substantiate or rebut novel claims made by deceased historian Alwyn Ruddock (d. 2005). Recent popular literature includes Hunter 2011 , which takes a broader approach including Columbus’s voyages, and Jones and Condon 2016 , which summarizes current knowledge and is the prelude to a forthcoming academic publication.

Almagià, Roberto. Gli italiani primi scopritori dell’America . Rome: La Libreria dello Stato, 1937.

Voluminous (and rare) publication in Italian on Italian “first discoverers” of America. Starts from Columbus, and devotes several pages to Caboto. It also includes tables and maps. Critically discusses documents relating to the life and voyages of Caboto (and his son).

Hunter, Douglas. The Race to the New World: Christopher Columbus, John Cabot, and a Lost History of Discovery . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

A popular history book, aimed at comparing the figures, the careers, and the achievements of Christopher Columbus and Giovanni Caboto. Includes the hypothesis (not backed by any documentary evidence) that Caboto might have accompanied Columbus on his second voyage of 1493.

Jones, Evan T. “Alwyn Ruddock: ‘John Cabot and the Discovery of America.’” Historical Research 81 (2008): 224–254.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2281.2007.00422.x

Discusses claims made by late historian Alwyn Ruddock concerning new discoveries relating to Caboto’s voyages. This article originated new archival research aimed at substantiating or clarifying Ruddock’s claims. See also The Cabot Project , cited under Internet Resources .

Jones, Evan T., and M. Condon. Cabot and Bristol’s Age of Discovery: The Bristol Discovery Voyages 1480–1508 . Bristol, UK: University of Bristol, 2016.

Aimed at a general audience, this book presents an updated summary of what we currently know about Caboto and his voyages. It also discusses claims made by the late historian Alwyn Ruddock concerning the discovery of new documents. Also available online .

Luzzana Caraci, Ilaria. “Giovanni Caboto cinquecento anni dopo.” In Giovanni Caboto e le vie dell’Atlantico settentrionale . Atti del Convegno Internazionale (Roma, 29 settembre–1 ottobre 1997). Edited by Marcella Arca Petrucci and Simonetta Conti, 51–68. Rome: CISGE, 1999.

Useful and articulated—albeit brief—summary of the main advancement in the knowledge of Caboto’s life and voyages from the sixteenth century (until 1997).

Pope, Peter. The Many Landfalls of John Cabot . Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997.

DOI: 10.3138/9781442681699

Discusses the current knowledge about Caboto, but also the claims of his son Sebastiano (denying his participation in his father’s voyage). Much space is devoted to the possible landfalls of the 1497 voyage and to the celebrations of 1897 (400th anniversary of the landing), when “anglophone/francophone cultural tensions [and] competition between Canada and Newfoundland” (p. 8) sparked debate on the landfall itself.

Williamson, James A. The Cabot Voyages and Bristol Discovery under Henry VII . Hakluyt Society Works, 2nd Series, Vol. 120. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1962.

Albeit dated, it is still the fundamental reference for sources concerning the voyages of John Cabot, as well as his son Sebastian’s and other Bristol voyages. A long introduction summarizes and compares all the sources and offers a considered narrative. It also includes an Appendix by R.A. Skelton, “The Cartography of the Voyages.” The volume reworks, with new documents added, an earlier study of 1929.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Atlantic History »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abolition of Slavery

- Abolitionism and Africa

- Africa and the Atlantic World

- African American Religions

- African Religion and Culture

- African Retailers and Small Artisans in the Atlantic World

- Age of Atlantic Revolutions, The

- Alexander von Humboldt and Transatlantic Studies

- America, Pre-Contact

- American Revolution, The

- Anti-Catholicism and Anti-Popery

- Army, British

- Art and Artists

- Asia and the Americas and the Iberian Empires

- Atlantic Biographies

- Atlantic Creoles

- Atlantic History and Hemispheric History

- Atlantic Migration

- Atlantic New Orleans: 18th and 19th Centuries

- Atlantic Trade and the British Economy

- Atlantic Trade and the European Economy

- Bacon's Rebellion

- Barbados in the Atlantic World

- Barbary States

- Berbice in the Atlantic World

- Black Atlantic in the Age of Revolutions, The

- Bolívar, Simón

- Borderlands

- Bourbon Reforms in the Spanish Atlantic, The

- Brazil and Africa

- Brazilian Independence

- Britain and Empire, 1685-1730

- British Atlantic Architectures

- British Atlantic World

- Buenos Aires in the Atlantic World

- Cabato, Giovanni (John Cabot)

- Cannibalism

- Captain John Smith

- Captivity in Africa

- Captivity in North America

- Caribbean, The

- Cartier, Jacques

- Catholicism

- Cattle in the Atlantic World

- Central American Independence

- Central Europe and the Atlantic World

- Chartered Companies, British and Dutch

- Chinese Indentured Servitude in the Atlantic World

- Church and Slavery

- Cities and Urbanization in Portuguese America

- Citizenship in the Atlantic World

- Class and Social Structure

- Coastal/Coastwide Trade

- Cod in the Atlantic World

- Colonial Governance in Spanish America

- Colonial Governance in the Atlantic World

- Colonialism and Postcolonialism

- Colonization, Ideologies of

- Colonization of English America

- Communications in the Atlantic World

- Comparative Indigenous History of the Americas

- Confraternities

- Constitutions

- Continental America

- Cook, Captain James

- Cortes of Cádiz

- Cosmopolitanism

- Credit and Debt

- Creek Indians in the Atlantic World, The

- Creolization

- Criminal Transportation in the Atlantic World

- Crowds in the Atlantic World

- Death in the Atlantic World

- Demography of the Atlantic World

- Diaspora, Jewish

- Diaspora, The Acadian

- Disease in the Atlantic World

- Domestic Production and Consumption in the Atlantic World

- Domestic Slave Trades in the Americas

- Dreams and Dreaming

- Dutch Atlantic World

- Dutch Brazil

- Dutch Caribbean and Guianas, The

- Early Modern Amazonia

- Early Modern France

- Economy and Consumption in the Atlantic World

- Economy of British America, The

- Edwards, Jonathan

- Emancipation

- Empire and State Formation

- Enlightenment, The

- Environment and the Natural World

- Europe and Africa

- Europe and the Atlantic World, Northern

- Europe and the Atlantic World, Western

- European, Javanese and African and Indentured Servitude in...

- Evangelicalism and Conversion

- Female Slave Owners

- First Contact and Early Colonization of Brazil

- Fiscal-Military State

- Forts, Fortresses, and Fortifications

- Founding Myths of the Americas

- France and Empire

- France and its Empire in the Indian Ocean

- France and the British Isles from 1640 to 1789

- Free People of Color

- Free Ports in the Atlantic World

- French Army and the Atlantic World, The

- French Atlantic World

- French Emancipation

- French Revolution, The

- Gender in Iberian America

- Gender in North America

- Gender in the Atlantic World

- Gender in the Caribbean

- George Montagu Dunk, Second Earl of Halifax

- Georgia in the Atlantic World

- German Influences in America

- Germans in the Atlantic World

- Giovanni da Verrazzano, Explorer

- Glorious Revolution

- Godparents and Godparenting

- Great Awakening

- Green Atlantic: the Irish in the Atlantic World

- Guianas, The

- Haitian Revolution, The

- Hanoverian Britain

- Havana in the Atlantic World

- Hinterlands of the Atlantic World

- Histories and Historiographies of the Atlantic World

- Hunger and Food Shortages

- Iberian Atlantic World, 1600-1800

- Iberian Empires, 1600-1800

- Iberian Inquisitions

- Idea of Atlantic History, The

- Impact of the French Revolution on the Caribbean, The

- Indentured Servitude

- Indentured Servitude in the Atlantic World, Indian

- India, The Atlantic Ocean and

- Indigenous Knowledge

- Indigo in the Atlantic World

- Internal Slave Migrations in the Americas

- Interracial Marriage in the Atlantic World

- Ireland and the Atlantic World

- Iroquois (Haudenosaunee)

- Islam and the Atlantic World

- Itinerant Traders, Peddlers, and Hawkers

- Jamaica in the Atlantic World

- Jefferson, Thomas

- Jews and Blacks

- Labor Systems

- Land and Propert in the Atlantic World

- Language, State, and Empire

- Languages, Caribbean Creole

- Latin American Independence

- Law and Slavery

- Legal Culture

- Leisure in the British Atlantic World

- Letters and Letter Writing

- Literature and Culture

- Literature of the British Caribbean

- Literature, Slavery and Colonization

- Liverpool in The Atlantic World 1500-1833

- Louverture, Toussaint

- Manumission

- Maritime Atlantic in the Age of Revolutions, The

- Markets in the Atlantic World

- Maroons and Marronage

- Marriage and Family in the Atlantic World

- Material Culture in the Atlantic World

- Material Culture of Slavery in the British Atlantic

- Medicine in the Atlantic World

- Mental Disorder in the Atlantic World

- Mercantilism

- Merchants in the Atlantic World

- Merchants' Networks

- Migrations and Diasporas

- Minas Gerais

- Mining, Gold, and Silver

- Missionaries

- Missionaries, Native American

- Money and Banking in the Atlantic Economy

- Monroe, James

- Morris, Gouverneur

- Music and Music Making

- Napoléon Bonaparte and the Atlantic World

- Nation and Empire in Northern Atlantic History

- Nation, Nationhood, and Nationalism

- Native American Histories in North America

- Native American Networks

- Native American Religions

- Native Americans and Africans

- Native Americans and the American Revolution

- Native Americans and the Atlantic World

- Native Americans in Cities

- Native Americans in Europe

- Native North American Women

- Native Peoples of Brazil

- Natural History

- Networks for Migrations and Mobility

- Networks of Science and Scientists

- New England in the Atlantic World

- New France and Louisiana

- New York City

- Nineteenth-Century Atlantic World

- Nineteenth-Century France

- North Africa and the Atlantic World

- Northern New Spain

- Novel in the Age of Revolution, The

- Oceanic History

- Pacific, The

- Paine, Thomas

- Papacy and the Atlantic World

- People of African Descent in Early Modern Europe

- Pets and Domesticated Animals in the Atlantic World

- Philadelphia

- Philanthropy

- Plantations in the Atlantic World

- Poetry in the British Atlantic

- Political Participation in the Nineteenth Century Atlantic...

- Polygamy and Bigamy

- Port Cities, British

- Port Cities, British American

- Port Cities, French

- Port Cities, French American

- Port Cities, Iberian

- Ports, African

- Portugal and Brazile in the Age of Revolutions

- Portugal, Early Modern

- Portuguese Atlantic World

- Poverty in the Early Modern English Atlantic

- Pregnancy and Reproduction

- Print Culture in the British Atlantic

- Proprietary Colonies

- Protestantism

- Quebec and the Atlantic World, 1760–1867

- Race and Racism

- Race, The Idea of

- Reconstruction, Democracy, and United States Imperialism

- Red Atlantic

- Refugees, Saint-Domingue

- Religion and Colonization

- Religion in the British Civil Wars

- Religious Border-Crossing

- Religious Networks

- Representations of Slavery

- Republicanism

- Rice in the Atlantic World

- Rio de Janeiro

- Russia and North America

- Saint Domingue

- Saint-Louis, Senegal

- Salvador da Bahia

- Scandinavian Chartered Companies

- Science, History of

- Scotland and the Atlantic World

- Sea Creatures in the Atlantic World

- Second-Hand Trade

- Settlement and Region in British America, 1607-1763

- Seven Years' War, The

- Sex and Sexuality in the Atlantic World

- Shakespeare and the Atlantic World

- Ships and Shipping

- Slave Codes

- Slave Names and Naming in the Anglophone Atlantic

- Slave Owners In The British Atlantic

- Slave Rebellions

- Slave Resistance in the Atlantic World

- Slave Trade and Natural Science, The

- Slave Trade, The Atlantic

- Slavery and Empire

- Slavery and Fear

- Slavery and Gender

- Slavery and the Family