What can we help you find?

While we certainly appreciate historical preservation, it looks like your browser is a bit too historic to properly view whitehousehistory.org. — a browser upgrade should do the trick.

Main Content

Rubenstein Center Scholarship

Mr. Churchill in the White House

- Robert Schmuhl

On December 13, 1941, six days after the “ infamy” of Pearl Harbor , Winston Churchill boarded the battleship Duke of York bound for America—and the White House. The British prime minister did not return to London until January 17, 1942, and this wartime visit to confer with President Franklin Roosevelt established Churchill’s own “special relationship” with the Executive Mansion at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. He was no longer alone, and his darkest hours had become history.

Before the United States entered World War II, the two leaders had exchanged over 200 messages (telegrams, letters, or phone calls) and met for four days in Newfoundland during August 1941. Churchill, who had become prime minister on May 10, 1940, as war in Europe escalated, desperately sought greater American involvement, while Roosevelt remained cautious yet helpful.

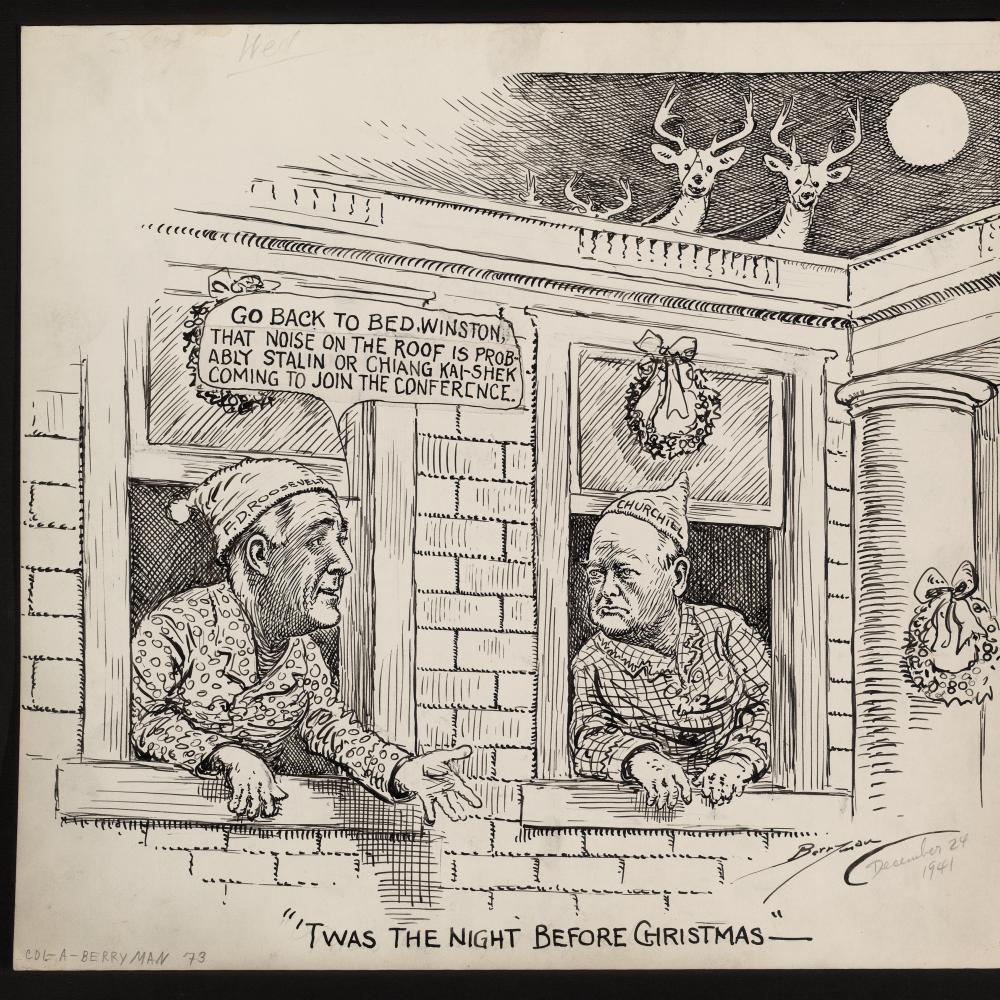

President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill give a joint press conference on December 23, 1941 in the Oval Office.

Show Me More

Everything changed on December 8 with the declaration of war by Congress. That day Roosevelt wired Churchill: “Today all of us are in the same boat . . . and it is a ship which will not and cannot be sunk.” 1 Churchill immediately began making travel plans to Washington, even though Roosevelt worried about his future guest’s safety on the Atlantic crossing. Protected by three destroyers and weathering gale-force winds, the Duke of York arrived at Norfolk Navy Yard in Virginia on December 22—with the president meeting the prime minister at a Washington airfield shortly thereafter.

How concerned was Roosevelt that there might be a leak about Churchill’s voyage? First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt remembered being told by her husband “that we would be having some guests visit us” that December. “He told me that I could not know who was coming, nor how many, but I must be prepared to have them stay over Christmas ,” she wrote years later in The Atlantic . “He added as an afterthought that I must see to it that we had good champagne and brandy in the house and plenty of whiskey.” 2

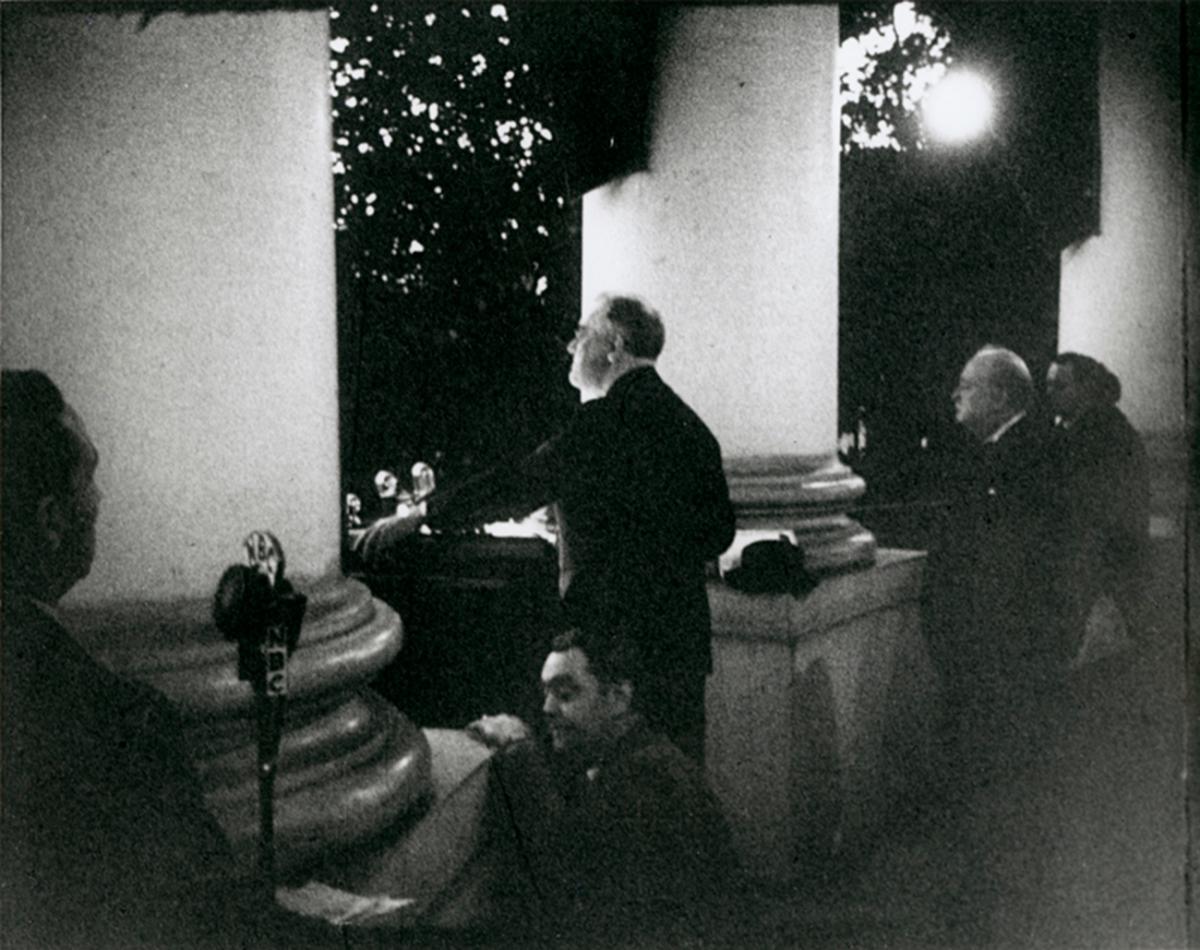

President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill preside over the National Christmas Tree lighting ceremony on December 24, 1941. Each leader gave a speech from the South Portico.

Once he was safely inside the White House, news of Churchill’s visit prompted banner headlines in newspapers around the world, and radio stations interrupted their broadcasts to announce his arrival. The two comrades in arms lost no time settling down for the first of many long discussions to plan military operations. Thus began the first of the prime minister’s five sojourns on American soil for consultations with FDR about the course of the war and its aftermath. The two leaders spent 113 days together between 1941 and 1945, and Churchill stayed at the White House on four different occasions. He also traveled with Roosevelt to the presidential retreat in Maryland (then called Shangri-La and today Camp David), as well as to Roosevelt’s beloved home in Hyde Park, N.Y.

Having Churchill as a guest in the Rose Bedroom of the White House meant that the president and his staff adapted to Churchillian ways. The Monroe Room on the Second Floor was converted into a map room to display the movement of troops and ships. His personal secretaries set up workspaces in the Lincoln Study. The visitor did much of his work—dictation of correspondence, reports, and speeches—after dinner and into the early morning hours. A self-described “tardy riser,” he liked to lounge in bed reading newspapers and catching up on affairs until lunchtime, and following that meal usually retired to his suite for an afternoon nap. But when the sun went down, he came alive for long conversations with his host or for composing his endless stream of documents.

In her book, On My Own (1958), Eleanor Roosevelt registered some displeasure with Churchill’s long-established routine. “They could talk for hours after dinner on any number of subjects,” she observed. “My husband, however, was so burdened with work that it was a terrible strain on him to sit up late at night with Mr. Churchill after working until 1 or 2 A.M. and then have to be at his desk early the next day while his guest stayed in his room until 11 A.M.” 3 Some memoirs detailing Roosevelt’s presidency mention that that he often needed time to recover from Churchill’s visits.

Both figures were outsized political personalities with immense confidence in themselves and what they were doing. Though Churchill was eight years older than Roosevelt, the prime minister understood that the president served as both head of state and head of government—and that Roosevelt had occupied this dual position since early 1933 . Recognizing these realities, as well as America’s much larger population and capacity for resources, the prime minister tended to defer to Roosevelt, despite differences of opinion that occurred, particularly in the later years of the war. Interestingly and despite trips abroad to Casablanca, Tehran, and Yalta, Roosevelt never visited Britain as president. Churchill, whose mother was an American, kept crossing the Atlantic for conferences at the White House and elsewhere.

Diana Hopkins, daughter of advisor Harry Hopkins, stands beside Mr. Churchill with President Roosevelt's dog Fala in January 1942.

The first visit from late December 1941 through early January 1942 was not only the longest but also the one that aroused the most curiosity and public interest. On December 23, Roosevelt and Churchill held a joint press conference . The next day the pair participated in the annual lighting of the National Christmas tree. On Christmas Day, they attended morning church services—and ended a round of White House events with a 90-minute discussion in Churchill’s suite. On December 26, the prime minister addressed a joint meeting of Congress, the first of three times (between 1941 and 1952) that he spoke to members of both the House of Representatives and Senate.

The evening after his speech at the Capitol, Churchill experienced what he called “a dull pain over my heart.” During an examination the following day, his doctor Sir Charles Wilson, later named Lord Moran, found that the “symptoms were those of coronary insufficiency,” a diagnosis he didn’t share with his patient. 4 Though Wilson suggested slowing down, Churchill kept to his busy schedule and headed to Ottawa for a speech to the Canadian Parliament on December 30. In his diary, published as Churchill in 1966, Lord Moran uses the phrase “heart attack” to describe the incident. 5 Medical professionals who have more recently studied Churchill’s records dispute that assessment.

Besides his public activities and a succession of planning meetings with Roosevelt and his war council, Churchill supplied a constant flow of reports and memoranda back to government officials in London. One update he wired to Clement Attlee, the deputy leader of the House of Commons and Lord Privy Seal, on January 3, 1942 is revealing in its description of what it was like to reside and work in the White House. Each page of the prime minister’s account—now available in the National Archives outside London—is marked with a warning in red: “HUSH—MOST SECRET.”

“We live here as a big family in the greatest intimacy and informality, and I have formed the very highest regard and admiration for the President,” Churchill said. “His breadth of view, resolution and his loyalty to the Common Cause are beyond all praise.” 6 Churchill’s opinion of the congenial domesticity is probably confirmed most dramatically by repeating an anecdote involving the president and his guest. In The Grand Alliance (1950), the third of six volumes comprising Churchill’s historical memoir, The Second World War , he notes that Roosevelt made a middle-of-the-night decision to call the Allies fighting the Axis countries the “ United Nations ” rather than the “Associated Powers.” In the prime minister’s account, “The President was wheeled in to me on the morning of January 1. I got out of my bath, and agreed to the draft.” 7

President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill fishing at the presidential retreat, Shangri-La in May 1943. This retreat is known today as Camp David.

Roosevelt’s recollection of what actually happened is somewhat more colorful. In F.D.R., My Boss (1949), his personal secretary Grace Tully remarked that the president later informed her about the incident, “You know, Grace, I just happened to think of it now. He’s pink and white all over.” 8

Margaret (Daisy) Suckley, a distant relative and confidante of President Roosevelt, corroborated the story. In her diary, published as Closest Companion (1995), Suckley says the president “called to W.S.C. & in the door leading to the bathroom appeared W.S.C.: a ‘pink cherub’ [FDR said] drying himself with a towel, & without a stitch on!” 9

Though Churchill denied ever uttering the quip often attributed to him during the encounter—“You see, Mr. President, I have nothing to conceal from you” 10 —the prime minister did, indeed, report to King George VI after his return later that January: “Sir, I believe I am the only man in the world who has received the head of a nation without any clothes on.” 11

The extended White House stay as the war began nurtured a personal bond between Churchill and Roosevelt. The president, in fact, sent a “Dear Winston” letter in March 1942 that included this advice: “I know you will keep up your optimism and your grand driving force, but I know you will not mind if I tell you that you ought to take a leaf out of my notebook. Once a month I go to Hyde Park for four days, crawl into a hole and pull the hole in after me. I am called on the telephone only if something of really great importance occurs.” 12

Churchill, however, relished action to the point of being somewhat of a daredevil and made more than two dozen trips abroad for meetings or battlefield visits during the war. But his time in Washington was special and sometimes quite out of the ordinary.

Once news broke that Mr. Churchill was residing at the White House, he began receiving fan mail from across the United States. This letter, addressed to "Churchill the Magnificent," was sent from Boston, Massachusetts during his extended visit of 1941-1942.

In the memoirs of the prime minister’s chief military assistant, General Hastings Ismay relates what happened in September 1943 during Churchill’s fourth visit to the White House. “The President had to go to Hyde Park before Churchill finished all that he wanted to do,” Ismay notes. “On leaving, he said, in so many words, ‘Winston, please treat the White House as your home. Invite anyone you like to any meals, and do not hesitate to summon any of my advisers with whom you wish to confer at any time you wish.” 13

Churchill seized the opportunity, later stopping at Hyde Park to report what he’d done. Ismay’s comment on Churchill’s decision to continue to conduct business at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue without the president in residence is striking: “I wonder if, in all history, there has ever existed between the war leaders of two allied nations, a relationship so intimate as that revealed by this episode.” 14

When Churchill became prime minister for a second time in 1951, he made trips to the United States on three different occasions—in 1952, 1953, and 1954. For the last one, the then-79-year-old leader wrote President Dwight Eisenhower , “My dear Friend,” proposing to “stay four or five days . . . at the [British] Embassy.” 15 Eisenhower, who had served as Supreme Allied Commander in Europe during World War II and worked closely with Churchill, came up with a different plan, which he expressed in an incomplete sentence: “Am desirous that you stay with me . . . at the White House.” 16 From the morning of June 25 until the afternoon of June 29, the prime minister engaged in his usual round of meetings, conversations, and meals with American officials. Despite being increasingly frail, the guest valued his return to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, wiring Eisenhower, “We have many pleasant and enduring memories of our visit to the White House.” 17

Five years later (in May 1959), President Eisenhower welcomed Britain’s most prominent statesman—and still an incumbent member of Parliament—back to Washington for yet another White House stay. Ike even took Churchill, a student of the American Civil War, to his farm in Gettysburg via helicopter to show him the nearly century-old battlefield from the air. Describing Churchill’s departure at the end of this stay, John Eisenhower, the president’s son and a noted historian, remarked that the years and several strokes had taken their toll on Britain’s bulldog. But he still commanded respectful attention: “When he left the White House after the visit, the entire presidential staff poured out to the northwest gate to send him off in his limousine, the members viewing him half in affection and half in awe.” 18

President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill pose with the Chiefs of Staff in May 1943. This photograph was taken in the garden outside the West Wing, known today as the Rose Garden.

That affection and awe only increased during Churchill’s final years. President John F. Kennedy considered Churchill a hero and invited him to return to the White House a few months after the young president’s inauguration in 1961. By that point such a journey was impossible and the offer was politely declined. Yet, two years later at a White House ceremony, Kennedy awarded Churchill honorary American citizenship, the first time a native of another country was so recognized by an Act of Congress. In his remarks, Kennedy, himself a Pulitzer Prize-winning author, praised the honoree’s ways with words: “In the dark days and darker nights when England stood alone . . . he mobilized the English language and sent it into battle.” 19

Even though Churchill could not make the journey to Washington, he composed a statement that his son, Randolph, read. In the eight-volume collection of Churchill’s “complete speeches”—8,917 pages in total—this address is the final one, and it combines both personal and historical reflections. “In this century of storm and tragedy,” he wrote, “I contemplate with high satisfaction the constant factor of the interwoven and upward progress of our peoples. Our comradeship and our brotherhood in war were unexampled. We stood together, and because of that fact the free world now stands.” 20

Churchill died on January 24, 1965, and Eisenhower traveled to London for the state funeral. In his tribute, he called his friend a “soldier, statesman, and citizen that two great countries were proud to claim as their own. Among all the things so written or spoken, there will ring out through all the centuries one incontestable refrain: Here was a champion of freedom.” 21 Freedom’s champion felt right at home in America, and the phrase he coined in 1944 to describe the enduring alliance between the United Kingdom and United States—“a special relationship”—also characterized his own personal association with the White House.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden are greeted by President Dwight Eisenhower, First Lady Mamie Eisenhower, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, and Vice-President Richard Nixon beneath the North Portico on June 25, 1954.

Robert Schmuhl is the Walter H. Annenberg-Edmund P. Joyce Professor of American Studies and Journalism at the University of Notre Dame. He recently served as a Visiting Research Fellow at the Rothermere American Institute at the University of Oxford, where he worked on his forthcoming book, Mr. Churchill in the White House .

This was originally published on February 12, 2018

Footnotes & Resources

- Warren F. Kimball, ed., Churchill & Roosevelt: The Complete Correspondence (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1984), 1: 283.

- Eleanor Roosevelt, “Churchill at the White House,” The Atlantic , March 1965, 77.

- Eleanor Roosevelt, On My Own (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1958), 34.

- Lord Moran, Churchill: Taken from the Diaries of Lord Moran, The Struggle for Survival 1940-1945 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1966), 17.

- Lord Moran, Churchill , 18-19.

- Winston S. Churchill, “Prime Minister to the Lord Privy Seal,” January 3, 1942, The National Archives (U.K.), Kew. Memorandum quoted in Winston S. Churchill, The Grand Alliance , vol. 3, The Second World War . (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1950), 686.

- Churchill, The Grand Alliance , 683.

- Grace Tully, F.D.R., My Boss (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1949), 305.

- Geoffrey C. Ward, ed., Closest Companion: The Unknown Story of the Intimate Friendship Between Franklin Roosevelt and Margaret Suckley (1995; repr., New York: Simon & Schuster, 2009), 385.

- Robert E. Sherwood, Roosevelt and Hopkins: An Intimate History (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1948), 442-443.

- Ward, Closest Companion , 385.

- Kimball, 1: 422.

- Hastings Lionel Ismay, The Memoirs of General the Lord Ismay (London: Heinemann, 1960), 319.

- Ismay, The Memoirs , 320.

- Peter G. Boyle, ed., The Churchill-Eisenhower Correspondence, 1953-1955 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1990), 141.

- Boyle, The Churchill-Eisenhower Correspondence , 143.

- Boyle, The Churchill-Eisenhower Correspondence , 153.

- John Eisenhower, “My Memories of Winston Churchill,” American Heritage , vol. 62, issue 3, summer 2017, <https://www.americanheritage.com/content/remembering-winston-churchill>

- John F. Kennedy, “Remarks on signing honorary citizenship for Sir Winston Churchill,” April 9, 1963, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston, Massachusetts. Presidential Papers. Speech Files, Series Number 03.

- Robert Rhodes James, ed., Winston S. Churchill His Complete Speeches 1897-1963 (London: Chelsea House, 1974), 8: 8709.

- Dwight D. Eisenhower, “Tribute to Sir Winston Churchill,” January 30, 1965, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum, Abilene, Kansas, Box 8, Speech Series, Post-Presidential Papers.

You Might Also Like

The american presidents song.

The origin of the "American Presidents" by Genevieve Ryan Bellaire is somewhat unique. One year, Genevieve's father asked her to memorize the order of the Presidents of the United States for Father's Day. As she did, she began to come up with rhymes to help her remember each President. After sharing this method with her family, they told her that

The Presidents and the Theatre

Read Digital Edition Foreword, William SealeThe Man Who Came to Dinner at the White House: Alexander Woollcott Visits the Roosevelts, Mary Jo Binker The Curse of the Presidential Musical: Mr. President and 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Amy HendersonFord's Theatre and the White House, William O'Brien The American Presidents and Shakespeare, Paul F. Boller Jr.Opera for the President: Superstars and Song in

International Presidents’ Day Wreath Laying

Carriages of the presidents.

Before the twentieth century, the presidents' vehicles were not armored-plated or specially built. Their carriages were similar to those of citizens of wealth. Often they were gifts from admirers. George Washington had the most elaborate turn out of the presidents for state occasions, sporting a cream-colored carriage drawn by six matched horses "all brilliantly caparisoned." Coachmen and footmen wore livery

Presidents at the Races

No sport created more excitement, enthusiasm and interest in the colonial period and the early republic than horse racing. Presidents George Washington and Thomas Jefferson took immense pride in their horses and bred them to improve the bloodlines of saddle, work, carriage and racehorses. Early presidents loved horse racing, the most popular sport in America at that time. George Washington,

The Presidents and Sports

Read Digital Version Forward by William SealeThe Presidents and Baseball: Presidential Openers and Other Traditions by Frederic J. FrommerUlysses S. Grant's White House Billiard Saloon by David RamseyTheodore Roosevelt: The President Who Saved Football by Mary Jo BinkerHoover Ball and Wellness in the White House by Matthew SchaeferCapturing A Moment in Time: Remembering My Summer Photographing President Eisenhower by Al

St. John’s, the Church of the Presidents

Featuring Rev. Robert Fisher, Rector at St. John’s Church

The Historic Stephen Decatur House

In 1816, Commodore Stephen Decatur, Jr. and his wife Susan moved to the nascent capital city of Washington, D.C. With the prize money he received from his naval feats, Decatur purchased the entire city block on the northwest corner of today’s Lafayette Square. The Decaturs commissioned Benjamin Henry Latrobe, one of America’s first professional architects, to design and buil

250 Years of American Political Leadership

Featuring Iain Dale, award-winning British author and radio and podcast host

"The President's Own"

On July 11, 1798, Congress passed legislation that created the United States Marine Corps and the Marine Band, America's oldest professional musical organization. The United States Marine Band has been nicknamed "The President's Own" because of its historic connection to the president of the United States. At its origin, the fledgling band consisted of a Drum Major, a Fife Major and 32 drums

Dinner with the President

Featuring Alex Prud’homme, bestselling author and great-nephew of cooking legend Julia Child

The History of Wine and the White House

Featuring Frederick J. Ryan, author of “Wine and the White House: A History" and member of the White House Historical Association’s National Council on White House History

The Official 2024 White House Christmas Ornament

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

From the archive, 27 December 1941: Churchill's speech to the US Congress

The Prime Minister was given an enthusiastic reception when he addressed both Houses of Congress in joint session at the Capitol yesterday.

Mr. Churchill said:

Anyone who did not understand the size and solidarity of the foundations of the United States might easily have expected to find an excited, disturbed, self-centred atmosphere, with all minds focused upon the novel, startling, and painful episodes of sudden war.

But here in Washington in these memorable days I have found an Olympian fortitude which, far from being based upon complacency, is the proof of a sure and well-grounded confidence in the outcome.

Now that we are together; now that we are linked in a righteous comradeship of arms; now, our steady light will glow and brighten.

Twice in a single generation, the catastrophe of world war has fallen upon us, twice in our lifetime has the long arm of fate reached across the ocean to bring the United States into the forefront of battle itself. If we had kept together after the last war, then this renewal of the curse need never have fallen upon us. (Cheers.)

Do we not owe it to ourselves, to our children, and to mankind to make sure that these catastrophes do not engulf us for the third time?

It is not given for us to peer into the mysteries of the future. Still, I avow my hope and faith, sure and inviolate, that in the days to come the British and American peoples will for their own safety and for the good of all walk together in majesty, in justice, and in peace.

Mr Churchill has planted himself firmly in the affections of the American people. He already had their admiration, built up largely on his home broadcasts. In his little Christmas Eve address he touched warmer and more intimate springs, and in his magnificent speech to Congress yesterday he gave Americans one of his masterpieces of political eloquence.

These things count enormously. Our two countries are embarked on a great partnership; so much depends on our knowledge of and confidence in each other. And from Mr. Churchill's visit we can look forward not only to the co-operation in strategy and supply which is essential but to the strengthening of that spiritual unity, that walking together "in majesty, in justice, and in peace," of which he spoke so finely. His reading of the American temper was sound; he rightly compared it with our own in the darkest days. He promised no smooth things; we should have to face more evil tidings (he was clearly preparing the way for more losses in the Pacific war), just as we should have good, as in Libya, on which he threw some significant light, and in the Battle of the Atlantic.

He faced boldly the questions which Americans, as well as we, have been putting about our unpreparedness in the Far East. He stated it frankly as a choice of where to apply limited resources, Libya or Malaya, the Atlantic or the Pacific. The United States, he said with truth, is suffering because of what she sent to help Britain. But "upon the whole," he argued, history will judge the disposition to have been the right one. The final appeal for Anglo-American unity was based on the firmest and most rational of grounds – a unity to prevent a third world catastrophe. In the last few weeks there has not been a great deal of domestic news coming from the United States. The applause of Congress showed better than a score of dispatches how American feeling runs – the great reception for Mr. Churchill, the cheers for Russia and China, the crushing cheers for the fight to a finish. The Americans are all set.

- Second world war

- From the Guardian archive

- Winston Churchill

- US politics

- Washington DC

Most viewed

- Divisions and Offices

- Grants Search

- Manage Your Award

- NEH's Application Review Process

- Professional Development

- Grantee Communications Toolkit

- NEH Virtual Grant Workshops

- Awards & Honors

- American Tapestry

- Humanities Magazine

- NEH Resources for Native Communities

- Search Our Work

- Office of Communications

- Office of Congressional Affairs

- Office of Data and Evaluation

- Budget / Performance

- Contact NEH

- Equal Employment Opportunity

- Human Resources

- Information Quality

- National Council on the Humanities

- Office of the Inspector General

- Privacy Program

- State and Jurisdictional Humanities Councils

- Office of the Chair

- NEH-DOI Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Partnership

- NEH Equity Action Plan

- GovDelivery

Christmas at the White House with Winston Churchill

After pearl harbor, the british prime minister insisted on visiting president roosevelt in washington..

Winston Churchill bunked at the White House in December 1941, spending Christmas with the Roosevelts and planning the next stage of World War II.

Library of Congress

On a cold December 22, 1941, an airplane carrying Winston Churchill touched down at an airfield near Washington, D.C. The prime minister had come to pay a visit to President Franklin Roosevelt and discuss how Britain and the United States could best coordinate strategy in the wake of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor.

Two weeks earlier, Roosevelt had stood before Congress and delivered a scathing indictment of the Japanese assault that left the U.S. Pacific fleet in pieces. “Yesterday, December 7th, 1941—a date which will live in infamy—the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan,” Roosevelt told Congress. The attack had destroyed 188 aircraft, sunk four battleships and one minesweeper, and turned thirteen other ships into floating wreckage. The human cost was even greater, as almost 3,500 sailors and soldiers lay either dead or wounded.

Roosevelt asked Congress for a declaration of war against Japan, which was quickly granted. On December 11, Nazi Germany, Japan’s ally, issued a declaration of war against the United States—and the United States responded in kind. After months of skirting the edge of neutrality, the United States had joined the Allies to fight the Axis in Europe and the Pacific.

Churchill welcomed American entry into the war but worried that pride and a desire for revenge would lead Roosevelt and his military chiefs to focus on Japan. Hoping to sway the president to prioritize the fight in Europe, where Nazi Germany continued its brutal assault on Britain and the Soviet Union, Churchill suggested he come for a visit to Washington.

“We could review the whole war plan in light of reality and new facts, as well as the problems of production and distribution,” he wrote Roosevelt. The president, knowing full well what the prime minister was up to, expressed concern that the voyage across the Atlantic, which crawled with German submarines, might be too hazardous. Churchill waved away Roosevelt’s fears about safety, arguing the bigger danger lay in not coordinating strategy immediately.

The global picture was harsh and threatening, with each new angle on the conflict giving way to another. Even the attack on Hawaii was part of a larger Japanese offensive that included assaults on Guam, the Philippines, Wake Island, and Midway Island. Britain suffered ongoing losses from Japanese attacks on Hong Kong and Malaya. Churchill also worried about how American entry into the war would affect its relations with Vichy France. What would that mean for North Africa?

Knowing how tenacious Churchill could be, Roosevelt quickly relented. “Delighted to have you here at the White House,” the president wrote on December 10.

Churchill looks on as Roosevelt delivers his remarks at the Christmas tree lighting on December 24, 1941.

Courtesy of FDR Library, Photo 74-20(492)

It is not really possible for a prime minister to disappear from London without anyone noticing. There is only so long that regrets can be given and excuses made before people begin to speculate.

As Churchill endured a turbulent ten-day trip aboard the British battleship Duke of York , Radio Berlin conjectured that he was in Washington, Moscow, or even the Middle East. Just four hours before Churchill arrived in Washington, a German radio broadcast noted that “diplomatic opinion is increasingly voiced that Churchill is in the Middle East.”

After the Duke of York docked at Hampton Roads, Virginia, on December 22, Churchill flew the last leg to Washington, where he was warmly received. “There was the President waiting in his car,” wrote Churchill. “I clasped his strong hand with comfort and pleasure.” They had not seen each other since their first meeting four months earlier in Newfoundland, although they had corresponded by telegram before that and with an increasing sense of comradery since.

At the White House, the two leaders paused long enough for the press corps to snap a few photos outside the front entrance, Churchill holding his cigar to the side. The fifty-nine-year-old Roosevelt, dressed in a patrician grey pinstripe suit, stands a full head taller than Churchill, who wore a double-breasted peacoat and a cap with the insignia of the Brotherhood of Trinity House, a royally chartered private corporation that cared for lighthouses and provided pilots for navigating the waterways for northern Europe. Churchill, who at age sixty-seven still loved a good uniform, had been a member since 1913. He also carried a walking stick outfitted with a light on the end, a necessity for navigating the nightly London blackouts. After the flashbulbs, Churchill popped his cigar back in his mouth and the two men headed inside.

Churchill stayed at the White House for the next three weeks, taking up residence in the Blue Room. The American newspapers couldn’t help but comment on the irony of the prime minister residing in the mansion that British troops burned during the War of 1812. The close quarters helped Churchill and Roosevelt cement their friendship. They started talking in the morning and didn’t stop until lights out, turning over ideas and weighing options. Both possessed lively minds that thrived on information. There were also some revealing moments. Roosevelt rolled his way over to Churchill’s room, to find the prime minister pink and pruned from his bath, dictating as he walked around, oblivious to the fact that his towel had fallen away.

The prime minister, of course, didn’t travel to Washington alone. The rest of his retinue—eighty-six members strong, ranging from Admiral Sir Dudley Pound and General Sir John Dill to stenographers, valets, detectives, private secretaries, and a code clerk—were lodged elsewhere.

The Washington that welcomed the British delegation had changed in the days since Pearl Harbor. Neon signs were dimmed. Black hoods covered the glow from fireboxes. Outdoor Christmas lights were rare, in keeping with regulations to avoid “unnecessary illumination of any kind.” Government agencies were being relocated to the Midwest to make room for military mobilization. Rationing, however, hadn’t yet reached the White House. When Churchill received two eggs at breakfast, he told First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, “Why, we only have one egg a week at home.”

The first meeting between Roosevelt , Churchill, and their military advisers was held on December 23 at 4:45 pm. The British received an early Christmas present—and the news for which they hoped. Roosevelt and his service chiefs were committed to a “Germany first” policy, which called for prioritizing the war in Europe over the Pacific. Disagreement, however, arose over where to strike first in Western Europe. The British favored an offensive in North Africa, which would provide a base for attacking southern France and Italy, while Americans wanted to take the fight to France directly across the English Channel.

Alongside discussions of strategy, there was also Christmas to attend to. On the afternoon of Christmas Eve, the president and the first lady distributed gifts to their 206 staff members. As they filed through the Oval Office, shaking hands with both Franklin and Eleanor, staff members received a photograph with the words “Christmas 1941” printed at the bottom. The picture featured the couple on the front porch at Hyde Park, the president in shirt sleeves and the first lady working her knitting needles.

After dusk, Churchill and part of the British delegation joined the president and the first lady on the South Portico of the White House for the lighting of the White House Christmas tree. Bundled up against the cold night air, the crowd pushed against the barricades to catch a glimpse of the world leaders. Multicolored lights soon came to life on the towering tree, and the president and prime minister delivered remarks.

“There are many men and women in America—sincere and faithful men and women—who asked themselves this Christmas: ‘How can we light our trees?” said Roosevelt, standing before radio microphones. “How can we meet and worship with love and with uplifted hearts in a world at war, a world of fighting and suffering and death?” Roosevelt believed that when people armed their hearts, the nation would endure and achieve victory. “Our strongest weapon in this war is that conviction of the dignity and brotherhood of man which Christmas day signifies—more than any other day or any other symbol. Against enemies who preach the principles of hate and practice them, we set our faith in human love and in God’s care for us and all men everywhere.” To encourage “the arming of our hearts,” he issued a proclamation, declaring January 1 a day of prayer.

Churchill also spoke, noting his mother’s American heritage and how he treasured his friendships with Americans. “I spend this anniversary and festival far from my country, far from my family, and yet I cannot truthfully say that I feel far from home,” he said. On this “strange Christmas eve,” he dedicated the night and holiday to children, giving them one night of wonder without the cares of war. “Make the children happy in a world of storm,” he told the American public. “Now, by our sacrifice and daring, these same children shall not be robbed of their inheritance, or denied the right to live in a free and decent world.”

It was never going to be an especially joyful holiday for the Roosevelts. Franklin’s mother, Sara, a force of personality in her own right, died earlier in the year. All four of the Roosevelt sons were in uniform and stationed elsewhere. Their daughter, Anna, decided to stay in Seattle with her husband and children. Instead of hanging stockings for their grandchildren, Eleanor hung a stocking on the mantle in the presidential bedroom for Fala, their beloved Scottish terrier, tucking a rubber bone inside. Rather than Franklin continuing the holiday tradition of reading A Christmas Carol to a group of wide-eyed grandchildren at his feet, another meeting was held to discuss wartime strategy.

On Christmas morning, the president and prime minister, guarded by a phalanx of gun-toting Secret Service agents, traveled up 16th Street to attend church at Foundry Methodist, sitting together in the fourth pew. Members of the British delegation also attended, along with General George Marshall and General Hap Arnold. The Stars and Stripes and Union Jack hung side by side next to the altar, while a bouquet of Easter lilies honored the memory of the president’s mother. After the hymns were sung and tidings offered for the season, the British and Americans headed back to the White House. Before they tucked into Christmas dinner, there would be one more strategy session, a discussion of how to defend Singapore from the Japanese.

When the hour finally arrived, Churchill and the other guests dined on a slate of American classics, starting with oysters on the half shell with crackers, clear soup with sherry, celery, assorted olives, and thin toast. The main course featured roast turkey, chestnut dressing, sausage-giblet gravy, beans, cauliflower, casserole of sweet potatoes, cranberry jelly, grapefruit salad and cheese crescents, and rolls. The meal ended with plum pudding and hard sauce, ice cream, coffee, salted nuts, and assorted bonbons. Whether the food tasted good was another matter, as the White House kitchen was notorious for churning out bad fare, much to the dismay of the president, who had a sophisticated palate.

After dinner, the group adjourned for a showing of Oliver Twist . When the screening paused to change the film reel, Churchill excused himself, claiming he needed to do some “homework.” His assignment was to finish the speech he was scheduled to deliver the next day to a joint session of Congress.

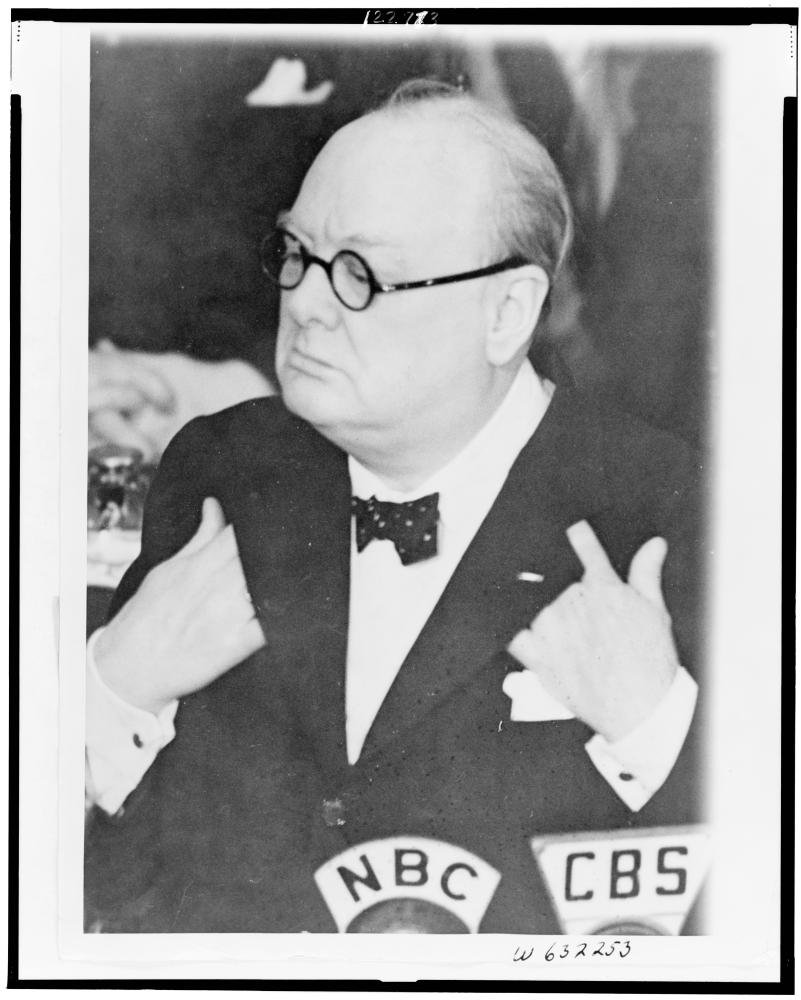

On December 26, senators and representatives packed the floor of the Senate, with extra chairs brought in for the occasion. Lucky spectators crammed the galleries above, hanging over the railings to get a better look at the first British prime minister to address Congress.

Churchill addresses Congress with wit, warmth, a great sense of occasion.

Stationed behind the clerk’s desk arrayed with a thicket of microphones, Churchill exuded confidence and warmth, calling the speech “one of the most moving and thrilling moments of my life which is already long and has not been entirely uneventful.” As laughter echoed through the chamber, he kept going. “I cannot help reflecting that if my father had been American and my mother British, instead of the other way round, I might have got here on my own. In that case, this would not have been the first time you would have heard my voice.”

Churchill’s tone turned serious when he spoke of the war, praising the “Olympian fortitude” he had encountered in Washington. He predicted “a long, hard war,” but one in which the Allies would assume “initiative upon an ample scale.” The supplies traversing the Atlantic, provided by the United States, would allow the British war effort to continue. “Sure I am that this day now, we are the masters of our fate; that the task which has been set us is not above our strength; that its pangs and toils are not beyond our endurance, as long as we have faith in our cause and unconquerable willpower, salvation will not be denied us,” he said.

He noted that twice in his lifetime “the long arm of fate has reached out to bring the United States into the forefront of the battle.” He lamented that if Britain and the United States had stuck together after the last war, the current war might never have happened. In response to his admonition about American isolationism, a few boos echoed through the chamber.

Churchill finished by praising the partnership and the possibilities of the Anglo-American alliance. “It is not given to us to peer into the mysteries of the future; yet, in the day to come, the British and American peoples will, for their own safety and for the good of all, walk together in majesty, in justice and in peace.”

Thunderous applause filled the chamber. Members of Congress and gallery occupants rose to their feet. Stepping off the rostrum, Churchill gave the “V” symbol for victory, prompting the chamber to roar again.

As he made his way out of the room, Churchill shook hands with the senators and representatives. Senator Ernest McFarland, a Democrat from Arizona, told Churchill his wife had to miss his speech because she was in the hospital. Later that day, the prime minister called her hospital room and wished her a “speedy recovery.”

Upon Churchill’s death 24 years later, his doctor revealed the prime minister had suffered a heart attack the night of his speech to Congress. Churchill ignored the common practice of bed rest for six weeks, and forged on with his meetings and memos. Now was not the time for weakness.

The First Washington Conference—also known by its code name ARCADIA—lasted through January 14. American and British planners laid out a plan for 1942. To fight Japan, they formed a joint command with the Dutch and Australians for the Far East. Plans were also made to send American bombers to bases in England and issue a declaration against making a separate peace with Germany. They also agreed to unify their military command structure, allowing for the coordination of land, air, and sea operations. The Combined Chiefs of Staff, based in Washington, became the body through which the Americans and British coordinated the execution of a global war. The decision to prioritize unity over parochialism played a key role in the success of the Anglo-American war effort during the next four years.

During discussions over where to strike first in Europe, the British argued for and won approval for an invasion of North Africa. The Americans, however, continued to resist the plan well into 1942, insisting that liberating France should be the focus. The Americans would ultimately lose that debate. In November 1942, American and British troops stormed the beaches at Casablanca, Oran, and Algiers, seizing control of French Morocco and Algeria in 74 hours. Operation TORCH provided a badly needed victory in the European theater for both the British and Americans. By May 1943, they had cleared the Germans and Italians from North Africa and the Middle East. Now, it was just a question of Italy, France, and Germany.

Meredith Hindley is a senior writer for Humanities .

Funding information

WETA received $750,000 from NEH to help support the production of Ken Burns’s The Roosevelts: An Intimate History . The George Marshall Research Foundation used $740,246 in NEH support to edit The Papers of George Catlett Marshall . The project, which started in 1982, recently published the final volume of the series. The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project at George Washington University has received $1.06 million to prepare print and digital versions of the first lady’s papers. The Washington, D.C.-based Churchill Centre has hosted two summer institutes for schoolteachers. David M. Kennedy received two NEH-supported fellowships to write his Pulitzer Prize-winning Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945 . Robert Dallek also used an NEH-supported fellowship for Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, 1932–194 5.

The Papers of George Catlett Marshall: Volume 3: The Right Man for the Job; U.S. State Department, Foreign Relations of the United States: The Conferences at Washington, 1941–1942, and Casablanca, 1943 ; U.S. Congress, Report of the Joint Committee on the Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack (GPO, 1946); Warren Kimball, Forged in War: Roosevelt, Churchill, and The Second World War (William Morrow, 1997); Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill: Road to Victory, 1941–1945 (Volume VII) (Rosetta Books, 2015); Newspaper articles from Baltimore Sun , Chicago Tribune , Christian Science Monitor , Los Angeles Times , New York Times , and New York Tribune .

SUBSCRIBE FOR HUMANITIES MAGAZINE PRINT EDITION Browse all issues Sign up for HUMANITIES Magazine newsletter

Skip to Main Content of WWII

Winston churchill's christmas meeting with fdr.

An interview with Anthony Tucker-Jones, author of the newly released Churchill: Master and Commander.

Anthony Tucker-Jones, author of the newly released Churchill, Master and Commander, interviewed by Jeremy Collins, Director of Conferences and Symposia at The National WWII Museum.

Churchill reflected upon his reaction to the news of the attack on Pearl Harbor and said he “slept the sleep of the saved.” Obviously, his spirits were elevated now that the United States was in the war, but tell us about those days, from December 8 through December 11, when there was no declaration of war between the Americans and Germans. Was he sleeping easy the nights of December 8, 9, or 10?

Immediately after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill declared war on Japan. Crucially, though, Roosevelt refrained from also declaring war on Germany, despite the provocation of a U-boat attack on the USS Kearny in mid-October 1941. This had left 11 dead and 22 wounded.

Churchill initially hoped that President Roosevelt would declare war on Germany and Italy in August 1941, when the pair met at Placentia Bay to discuss the situation in Europe. They had issued the Atlantic Charter that set out a series of broad American and British goals for the postwar world.

By the end of the year Churchill knew that war was brewing in the Far East thanks to British intelligence, which was monitoring Japanese fleet and troop movements. What he did not know was whether they would only attack British and Dutch interests. The American oil embargo against Japan for its incursions into Indochina indicated that the Japanese might also lash out against America.

While Churchill was relieved that Britain would not be fighting alone in the Far East, it would not benefit from American intervention in the Mediterranean and Europe. However, Hitler then did Churchill a quite remarkable favor on December 11 by declaring war on America. He was fed up with America violating its own neutrality policy by favoring Germany’s enemies with financial support, weapons, and training facilities.

Was the famous Christmas 1941 visit by Churchill planned before the attack on Pearl Harbor, or was it hastily put together in reaction to it? What were Churchill’s goals for the encounter?

In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt really had better things to do than host Churchill, but he knew that another face-to-face meeting was important. Undoubtedly Churchill’s emergency visit helped to energize and focus Roosevelt and the US chiefs of staff. It was vital that the two political leaders find common cause on how to win the war.

Churchill, in light of the Japanese rampaging through the Pacific, was anxious that America stick to its professed Europe-first strategy. He was understandably anxious that America might prioritize the campaign in the Pacific and reduce or cut off military aid. Roosevelt reassured him that he would stick to Europe-first, though under pressure from Churchill, it would soon turn into a Mediterranean-first strategy. It was agreed that the defeat of Hitler and Mussolini would be the top priority.

Major strategic aims were discussed and decided, but there was also much social and personal interaction between the two heads-of-state. Describe Churchill’s and Roosevelt’s time together during the Christmas season.

Churchill and the British chiefs of staff spent three weeks with Roosevelt and the US chiefs of staff, during which time there was a mixture of hard work and social events. Importantly, Churchill and Roosevelt presented a united front with the American media. When Churchill was asked by a reporter how long would it take to win the war, he replied, “If we manage it well, it will only take half as long as if we manage it badly.”

This had been met with much laughter. During their Christmas Eve party, after much champagne and as they settled down to brandy, Churchill teased Roosevelt that America had sent too much powdered egg. Roosevelt good humoredly retorted “Nonsense, you can do as much with powdered egg as with real egg.” Some joker then asked “How do you fry powdered egg?”

Hong Kong fell to Japanese forces on Christmas Day. Churchill delivered his now-famous speech to the joint chambers of Congress the next day. That evening, he had a mild heart attack. How taxing was this trip for him and were his health concerns known to his American counterparts?

When Churchill arrived in America on December 22, photographs show him looking absolutely exhausted, but he was immediately launched into a round of socializing that very night. It was not long before he was complaining to Sir Charles Wilson, his personal doctor, of palpitations and a racing pulse. Churchill was undoubtedly under enormous pressure and he worried constantly about his speech.

Having won over Roosevelt and the US chiefs of staff, he knew it was vital for him to win over the assembled American politicians. Fortunately, he was a resounding success, with Sir Charles remarking, “The Senators and Congressmen stood cheering and waving their papers till he went out.”

Immediately afterwards Churchill complained of chest pain and discomfort down his left arm. An alarmed Sir Charles diagnosed a mild heart attack, but refrained from telling Churchill for fear it would affect his conduct. He reasoned “at a moment when America had just come into the war, and there is no one but Winston to take her hand. I felt that the effect of announcing the P.M. had had a heart attack could only be disastrous.” Instead he simply told Winston he had been overdoing it. Just imagine what would have happened had Churchill died in Washington. It would have been catastrophic and undoubtedly setback the Anglo-American alliance.

The “Special Relationship” between the United Kingdom and the United States has come under fire of late. This summit certainly helped form the bonds of the western allies that would lead to ultimate victory. Just how special was the “Special Relationship”?

It is very important to remember that it was Roosevelt who initiated this relationship from the point when Churchill was reappointed First Lord of the Admiralty in September 1939. It then developed apace once Churchill became prime minister in May 1940. From then on, Roosevelt did everything in his power to help Britain even before America was dragged into the war and despite the legal constraints of the US neutrality acts.

He sold arms to Britain and France through his ‘cash and carry’ policy, he then transferred destroyers to the Royal Navy, provided the RAF with training bases, followed by Lend-Lease. An immensely grateful Churchill called the latter a “turning point” and described it “as the most unsordid act in the whole of recorded history.”

While it is accepted that both Britain and America had a common goal, ultimately they had very divergent agendas when it came to the future of Europe, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific. Roosevelt had no intention of restoring the British, nor the French for that matter, empire which he viewed as wholly undemocratic. Both he rightly felt were at odds with the Atlantic Charter, especially when it came to India. Likewise, Roosevelt did not share Churchill’s enthusiasm for Charles de Gaulle, the leader of the Free French, whom he saw as a dictator in waiting who wanted to take power in a liberated France.

Churchill and Roosevelt did not see eye to eye over the opening of the Second Front nor the conduct of the war in Italy and Southeast Asia. Regarding the latter, Churchill’s goal was to return Singapore to British authority, whereas Roosevelt’s goal was to gain China’s support for the war against Japan in the Pacific. Nonetheless, Churchill and Roosevelt retained a strong respect for each other.

After Roosevelt’s death on April 12, 1945 Churchill said, “I conceived an admiration for him as a statesman, a man of affairs and a war leader.” Churchill then added, “He was the greatest American friend that Britain ever found.” It was their personal bond which forged the “Special Relationship.”

Meet the Author: Anthony Tucker-Jones

British author and historian Anthony Tucker-Jones comes to discuss his latest work on one of the giants of history, Winston Churchill, with the Museum’s own Dr. Rob Citino.

Churchill, Master and Commander

Jeremy Collins

Jeremy Collins joined The National WWII Museum in 2001 as an intern, and now oversees the institution’s public programming initiatives.

Explore Further

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

When the Nazis came to clear out the Warsaw Ghetto, they were met with fierce resistance.

Stutthof Concentration Camp and the Death Marches

Stutthof concentration camp was among the sites of horror caught up in this gruesome crescendo to Adolf Hitler’s war for racial supremacy.

Dauntless: A Conversation with WWII Veteran Paul Hilliard

Visitors at the National WWII Museum had the special opportunity to hear from WWII veteran and Museum Trustee Paul Hilliard as he discussed his life story documented in the new biography, Dauntless .

Lee Miller: Witness to the Concentration Camps and the Fall of the Third Reich

One of America’s only women war correspondents reports on the liberation of the concentration camps, Soviet and American troops meeting at Torgau, and Hitler’s burning villa in Berchtesgaden

Lee Miller in Combat

One of America’s only female war correspondents reported on the aftermath of D-Day, the Battle of Saint-Malo, and the liberation of Paris.

Lee Miller: Women at War

One of America’s only female war correspondents captured the war through women’s service.

A Contested Legacy: The Men of Montford Point and the Good War

Despite their commendable service during World War II, the Marines of Montford Point would regularly contend with societal forces that vehemently resisted all measures taken toward racial integration.

Our War Too: Women's History Symposium

The symposium, which took place from February 29 to March 1, 2024, featured topics expanding upon the Museum’s special exhibit, Our War Too: Women in Service .

Winston Churchill in America

His travels and ties nurtured the special relationship between the United States and Britain

John H. Chettle

On Winston Churchill's first visit to the United States after Pearl Harbor, he told a joint session of Congress that "I cannot help reflecting that if my father had been American and my mother British, instead of the other way round, I might have got here on my own."

Churchill, more than any other person, turned what had been a tenuous and often uneasy association between the United States and Great Britainfor all the (not always helpful) historical tiesinto a special relationship.

Before World War II, isolationism and ethnic partisanship often intruded on any intimacy between the two countries. But Churchill's knowledge of the United States and its people brought his nation and ours together. His understanding of America was to a large extent the product of his visits here. From his first visit in 1895 to his last in 1961, he got to know the country and many of its statesmen, including Presidents from McKinley to Kennedy. His relationship with Franklin D. Roosevelt was one of the key elements of the Allied partnership.

Churchill made and lost large sums of money, and nearly lost his life in an automobile accident, in the United States. In Washington, D.C., he helped to formulate the strategy that won World War II. And he, more than anyone, was responsible for raising awareness of the Soviet danger at the outset of the Cold War, in his famous "Iron Curtain" speech, given at Fulton, Missouri, in 1946. It is an extraordinary record. As former Secretary of State Dean Acheson later wrote, "Mr. Churchill has been one of the fewthe very fewwho have significantly and beneficently affected the course of events.... How seldom can this be said of anyone!"

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The very hour that the United States entered World War II, Winston Churchill decided to invite himself to Washington, D.C. On December 8, 1941, even as Franklin D. Roosevelt was delivering his ...

Still, I avow my hope and faith, sure and inviolate, that in the days to come the British and American peoples will, for their own safety and for the good of all, walk together in majesty, in justice and in peace. Winston Churchill. December 26, 1941. Addressing a joint session of US Congress. Churchill addresses the Unites States' Congress.

Crowds wait for Churchill outside the U.S. Capitol (Washington Star)Winston Churchill's first address to the U.S. Congress was a 30-minute World War II-era radio-broadcast speech made in the chamber of the United States Senate on December 26, 1941. The prime minister of the United Kingdom addressed a joint meeting of the bicameral legislature of the United States about the state of the UK-U ...

On December 13, 1941, six days after the "infamy" of Pearl Harbor, Winston Churchill boarded the battleship Duke of York bound for America—and the White House. The British prime minister did not return to London until January 17, 1942, and this wartime visit to confer with President Franklin Roosevelt established Churchill's own "special relationship" with the Executive Mansion at ...

Within days of the Japanese surprise attack on the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Churchill (now Prime Minister) undertook a dangerous transatlantic journey on the HMS Duke of York. He arrived in America on December 22, in time to spend Christmas at the White House. ... Churchill would visit the United States four more times.

Churchill had made first visit to the United States shortly before his 21st birthday. In November 1895, he traveled by steamship to New York, where he stayed for more than a week on his way to ...

Churchill was eager to have the United States join the British forces in Europe and undertook a dangerous transatlantic journey to address Congress in December, 1941. The Japanese surprise attack on the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, brought America into the war. Four days later, Germany declared war on the United States, making U.S. involvement in Europe inevitable.

Churchill's schedule during his visit to Washington was tightly packed with business both official and social. ... At the conclusion of Churchill's 30-minute address, Chief Justice of the United States Harlan F. Stone extended a "V" for victory sign. ... 1941, 515-17; "Don't Count on Collapse in Reich, Says Churchill ...

Originally published in the Manchester Guardian on 27 December 1941 : The Prime Minister was given an enthusiastic reception when he addressed both Houses of Congress in joint session at the ...

February 11, 2009. Winston Churchill Addresses A Joint Session Of Congress on December 26, 1941. by Winston Churchill. I feel greatly honoured that you should have invited me to enter the United States Senate Chamber and address the representatives of both branches of Congress. The fact that my American forebears have for so many generations ...

About this event. This virtual event will explore the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941, and Sir Winston Churchill's historic visit to the White House in the weeks after the attack. Professors John Maurer and Paul Kennedy will lead the discussion, which will be moderated by ICS Executive Director Justin Reash.

On a cold December 22, 1941, an airplane carrying Winston Churchill touched down at an airfield near Washington, D.C. The prime minister had come to pay a visit to President Franklin Roosevelt and discuss how Britain and the United States could best coordinate strategy in the wake of Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor.

This exhibition examines the life and career of Winston Spencer Churchill and emphasizes his lifelong links with the United States--the nation he called "the great Republic." This exhibition comes nearly forty years after death of Winston Churchill and sixty D-Day allied invasion Nazi-occupied France during World War II. It commemorates both these events.

Undoubtedly Churchill's emergency visit helped to energize and focus Roosevelt and the US chiefs of staff. It was vital that the two political leaders find common cause on how to win the war. Churchill, in light of the Japanese rampaging through the Pacific, was anxious that America stick to its professed Europe-first strategy.

From his first visit in 1895 to his last in 1961, he got to know the country and many of its statesmen, including Presidents from McKinley to Kennedy. His relationship with Franklin D. Roosevelt ...

During his visit to the US in December 1941, the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill talked about World War Two. 21 December 2022. World War Two.

Winston Churchill made 16 visits to America in his lifetime. He traveled here as a soldier, a tourist and a lecturer, but his winter visit to America in 1941 as a wartime leader was perhaps his ...

The Roaring Lion, a portrait by Yousuf Karsh at the Canadian Parliament, 30 December 1941.. Winston Churchill was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty on 3 September 1939, the day that the United Kingdom declared war on Nazi Germany.He succeeded Neville Chamberlain as prime minister on 10 May 1940 and held the post until 26 July 1945. Out of office during the 1930s, Churchill had taken the ...

Join us for the 41st International Churchill Conference. London | October 2024 ... Designed in 1941 and first flown in mid-1942, it used the wings, tail, Rolls-Royce Merlin engines and landing gear of Bomber Command's famous Lancasters, but had a more capacious square-section fuselage. ... Churchill made numerous short hops to visit troops on ...

In December 1941, mere weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Winston Churchill traveled to the United States to meet with President Franklin Roosevelt. The two leaders and their staffs met and began preparations for the alliance that would change the course of history. It was the first year the National Community Christmas Tree was within the ...

This photograph taken in the summer of 1941, shows Churchill's recognizable figure as he watches the arrival of the first B-17 "Flying Fortress." Even though the U.S. was desperately trying to build up its military forces throughout 1941, Roosevelt decided to give the British models of the United States' most advanced weapons.

January 1, 1970. In November 1941, Churchill visits the 'warrior' towns of the north of England - Newcastle, Hull and Sheffield - to see dockyards, shell factory in Sheffield, and bomb damage. In his usual style, he gives his 'V-for-Victory sign and raises his hat on his walking stick, waving it to the crowds.