UN Tourism | Bringing the world closer

Product development.

- Rural tourism

- Gastronomy and Wine Tourism

- Mountain Tourism

Urban Tourism

- Sports Tourism

- Shopping Tourism

share this content

- Share this article on facebook

- Share this article on twitter

- Share this article on linkedin

According to UN Tourism, Urban Tourism is "a type of tourism activity which takes place in an urban space with its inherent attributes characterized by non-agricultural based economy such as administration, manufacturing, trade and services and by being nodal points of transport. Urban/city destinations offer a broad and heterogeneous range of cultural, architectural, technological, social and natural experiences and products for leisure and business".

According to the United Nations, in 2015, 54% of the world’s population lived in urban areas and, by 2030, this share is expected to reach 60%. Along with other key pillars, tourism constitutes a central component in the economy, social life and the geography of many cities in the world and is thus a key element in urban development policies.

Urban tourism can represent a driving force in the development of many cities and countries contributing to the progress of the New Urban Agenda and the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, in particular, Goal 11: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable . Tourism is intrinsically linked to how a city develops itself and provides more and better living conditions to its residents and visitors.

Fulfilling tourism’s potential as a tool of sustainable and inclusive growth for cities requires a multi-stakeholder and multilevel approach based on close cooperation among tourism and non-tourism administrations at different levels, private sector, local communities and tourists themselves. Likewise, the sustainable development and management of tourism in cities needs to be integrated into the wider urban agenda.

8th UN Tourism Global Summit on Urban Tourism "Smart Cities, Smart Destinations" 7th UN Tourism Global Summit on Urban Tourism 6th Global Summit on Urban Tourism 5th Global Summit on City Tourism 4th Global Summit on City Tourism 3rd Global Summit on City Tourism 2nd UN TourismGlobal Summit on City Tourism Global Summit on City Tourism

UN Tourism Conference on City Breaks: Creating Innovative Tourism Experiences

Mayors Forum for Sustainable Urban Tourism

3rd edition Mayors Forum for Sustainable Urban Tourism (Madrid)

2nd edition Mayors Forum for Sustainable Urban Tourism (Porto) 1st edition Mayors Forum for Sustainable Urban Tourism (Lisbon)

Quantifying tourism in city destinations

This joint report of UN Tourism and WTCF assesses the current situation and challenges of tourism data collection and reporting at the city level through the review and analysis of 22 case studies of city destinations covering Africa, the Americas, Asia and the Pacific, Europe, and the Middle East. The analysis will help advance the harmonization of existing data practices in city destinations with the ambition of creating a global database of urban tourism, enabling better understanding and benchmarking of its size, value and impacts, both globally and by region.

UN Tourism Recommendations on Urban Tourism

These recommendations stem from the series of UN Tourism Urban Tourism Summits held since 2012, and the Lisbon Declaration on Sustainable Urban tourism, adopted at the First UN Tourism Mayors Forum for Sustainable Urban Tourism, held in Portugal on 5 April 2019. They also drawn on the research conducted by the UN Tourism Secretariat in the field of urban tourism.

UN Tourism-WTCF City Tourism Performance Research

The UN Tourism/WTCF City Tourism Performance Research brings forward an analysis and evaluation of success stories in urban destinations. The results were collected by experts who applied the methodology created for the initiative through the realization of field visits and interviews of local tourism authorities and the main stakeholders. The publication based on case studies from 15 cities, provides in-depth understanding of each individual city and has the objective to enable other cities to learn from the progress they have achieved in order to enhance their performance, competitiveness and sustainability.

‘Overtourism’? – Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth beyond Perceptions

The management of tourism flows in cities to the benefit of visitors and residents alike is a fundamental issue for the tourism sector. It is critical to understand residents’ attitude towards tourism to ensure the development of successful sustainable tourism strategies. This report analyzes the perception of residents towards tourism in eight European cities – Amsterdam, Barcelona, Berlin, Copenhagen, Lisbon, Munich, Salzburg and Tallinn – and proposes 11 strategies and 68 measures to help understand and manage visitor’s growth in urban destinations. The implementation of the policy recommendations proposed in this report can advance inclusive and sustainable urban tourism that can contribute to the New Urban Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals.

‘Overtourism’? – Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth beyond Perceptions. Volume 2: Case Studies

This second volume includes 18 case studies across the Americas, Asia and the Pacific and Europe – Amsterdam, Antwerp, Barcelona, Berlin, Besalú, Cambridge, Dubrovnik, Edinburgh, Ghent, Hangzhou, London, Lucerne, Macao (China), New York, Lisbon, Seoul, Porto, Prague and Venice – on how cities are implementing the following eleven strategies: 1. Promote the dispersal of visitors within the city and beyond; 2. Promote time-based dispersal of visitors; 3. Stimulate new visitor itineraries and attractions; 4. Review and adapt regulation; 5. Enhance visitors’ segmentation; 6. Ensure local communities benefit from tourism; 7. Create city experiences that benefit both residents and visitors; 8. Improve city infrastructure and facilities; 9. Communicate with and engage local stakeholders; 10. Communicate with and engage visitors; and 11. Set monitoring and response measures.

Global survey on the perception of residents towards city tourism: impact and measures

This research is a result of a partnership between the World Tourism Organization (UN Tourism) and IPSOS. To better manage the issues arising from the growing tourism demand in urban destinations it is essential to understand resident's experiences and perceptions on city tourism. The research aims at understanding the perception of residents towards city tourism, its impacts, as well as the most adequate strategies to manage the growing tourism flows in cities.

New Business Models in the Accommodation Industry – Benchmarking of Rules and Regulations in the Short-term Rental Market

Several factors explain the growth of the so-called “sharing economy” in the tourism sector over recent years, including the 2010 global economic crisis, digitalization and new trends in travellers’ behaviour and preferences. This growth has been particularly notable in the accommodation industry. With the emergence of online platforms for short-term rentals, the market has been expanding at an unprecedented rate.

Building upon UN Tourism’s 2017 publication New Platform Tourism Services (or the so-called Sharing Economy) – Understand, Rethink and Adapt, this report provides an analysis and benchmarking of 21 case studies in terms of the rules and regulations applied to the short-term rental market, focusing on three key areas: 1) fair competition; 2) consumer protection; and 3) planning and sustainability.

- Tianjin Workshop, 2 September 2017

- Buenos Aires Workshop, 26 September 2017

ScienceSphere.blog

Exploring The Contrasts: How Does Rural Travel Differ From Urban Travel?

Traveling is a wonderful way to explore new places, experience different cultures, and create lasting memories. Whether you prefer the quiet serenity of rural areas or the bustling energy of urban environments, each type of travel offers its own unique charm and experiences. In this article, we will delve into the key contrasts between rural and urban travel experiences, allowing you to gain a deeper understanding of the benefits and attractions of each.

Table of Contents

Hook: Start with an interesting fact or statistic about travel

Did you know that according to the World Tourism Organization, international tourist arrivals reached a staggering 1.4 billion in 2018? This shows the immense popularity and appeal of travel for people all around the world.

Introduce the topic of rural travel vs. urban travel

When it comes to travel, one of the fundamental decisions to make is whether to explore rural or urban areas. Rural travel refers to visiting countryside regions, characterized by their natural beauty, tranquility, and slower pace of life. On the other hand, urban travel involves exploring vibrant cities, known for their fast-paced lifestyle, cultural diversity, and abundance of entertainment options.

Thesis statement: Explore the key contrasts between rural and urban travel experiences

In this article, we will delve into the defining characteristics of rural and urban travel, including transportation options, accommodation choices, activities and attractions, food and dining experiences, and budget considerations. By understanding the unique aspects of each type of travel, you will be able to make informed decisions and create unforgettable experiences.

Traveling to rural and urban areas offers distinct experiences that cater to different preferences and interests. While some may seek solace in the tranquility of rural landscapes, others may thrive in the vibrant energy of bustling cities. Ultimately, the choice between rural and urban travel depends on your personal preferences, the type of experience you seek, and the activities and attractions that resonate with you.

In the following sections, we will explore the various aspects of rural and urban travel, allowing you to gain a comprehensive understanding of what each has to offer. From transportation options to accommodation choices, activities and attractions to food and dining experiences, we will delve into the key contrasts between these two types of travel. So, let’s embark on this journey and discover the wonders of rural and urban travel!

Definition and Characteristics of Rural Travel

Rural travel refers to the act of exploring and experiencing the countryside and its surrounding areas. It offers a stark contrast to the hustle and bustle of urban life. Here are some key characteristics of rural travel:

Tranquility and Slower Pace

One of the defining features of rural travel is the tranquility it offers. Unlike urban areas, rural destinations are often characterized by peaceful surroundings and a slower pace of life. Travelers who seek a break from the chaos and noise of the city will find solace in the serene landscapes and quiet villages of rural areas. The absence of traffic congestion and the constant rush of people allows visitors to unwind and relax in a peaceful environment.

Connection with Nature and Outdoor Activities

Rural travel provides an excellent opportunity to connect with nature and engage in various outdoor activities. Nature enthusiasts will be delighted by the abundance of natural wonders, such as mountains, forests, lakes, and rivers. These areas offer a chance to hike, bike, swim, fish, and engage in other outdoor pursuits. The vast open spaces and untouched landscapes allow travelers to immerse themselves in the beauty of nature and experience a sense of freedom and tranquility that is often hard to find in urban areas.

Cultural Heritage and Authentic Experiences

Rural areas are often rich in cultural heritage and offer a glimpse into the traditions and customs of the local communities. Travelers can explore historic sites, visit traditional villages, and interact with the locals to gain a deeper understanding of the local culture. The authenticity of rural travel experiences is a significant draw for those seeking a more genuine and immersive travel experience. From participating in local festivals to learning traditional crafts or enjoying regional cuisine, rural travel allows visitors to connect with the local culture in a meaningful way.

In conclusion, rural travel provides a unique and contrasting experience to urban travel. The tranquility, connection with nature, and authentic cultural experiences make it an appealing option for those seeking a break from the fast-paced urban lifestyle. Whether it’s exploring the countryside, engaging in outdoor activities, or immersing oneself in the local culture, rural travel offers a chance to unwind, rejuvenate, and create lasting memories. So, why not venture off the beaten path and discover the hidden gems of rural destinations?

Definition and Characteristics of Urban Travel

Urban travel refers to the act of exploring and experiencing cities and their bustling environments. Unlike rural travel, which focuses on the tranquility and slower pace of rural areas, urban travel offers a fast-paced and vibrant atmosphere that is unique to cities. In this section, we will delve into the definition and characteristics of urban travel, highlighting what makes it distinct and appealing to travelers.

Define Urban Travel and its Main Features

Urban travel can be defined as the exploration of cities, including their culture, architecture, history, and entertainment options. It involves immersing oneself in the urban lifestyle, experiencing the energy and diversity that cities have to offer. The main features of urban travel include:

Fast-Paced Environment : Cities are known for their fast-paced nature, with people constantly on the move. The streets are filled with bustling crowds, vehicles, and the sounds of city life. This dynamic atmosphere creates a sense of excitement and energy that is unique to urban areas.

Vibrant Cultural Scene : Cities are cultural melting pots, offering a wide range of artistic and cultural experiences. From museums and art galleries to theaters and music venues, urban areas are filled with opportunities to immerse oneself in the arts and experience different cultural expressions.

Architectural Marvels : Urban travel allows visitors to marvel at impressive architectural structures that define city skylines. From towering skyscrapers to historical landmarks, cities are home to iconic buildings that showcase human creativity and engineering prowess.

Entertainment Opportunities : Urban areas are renowned for their entertainment options. Whether it’s shopping in high-end boutiques, dining at world-class restaurants, or enjoying vibrant nightlife, cities offer a plethora of entertainment choices that cater to diverse interests and preferences.

Discuss the Fast-Paced and Vibrant Atmosphere of Cities

One of the defining characteristics of urban travel is the fast-paced and vibrant atmosphere that permeates cities. Unlike rural areas, where life tends to move at a slower pace, cities are constantly buzzing with activity. The streets are filled with people rushing to work, tourists exploring the sights, and locals going about their daily routines.

The fast-paced nature of cities creates a sense of urgency and excitement. There is always something happening, whether it’s a street performance, a cultural festival, or a new restaurant opening. This constant buzz of activity makes urban travel an exhilarating experience, as there is never a dull moment in the city.

Moreover, cities offer a vibrant and diverse cultural scene. Museums, art galleries, and theaters showcase a wide range of artistic expressions, allowing travelers to immerse themselves in the local culture. Urban areas are also known for their diverse culinary scenes, offering a variety of international cuisines and dining experiences.

Highlight the Cultural and Entertainment Opportunities in Urban Areas

Urban travel provides ample opportunities for cultural enrichment and entertainment. Cities are home to a multitude of cultural attractions, such as historical sites, museums, and art galleries. Travelers can explore the rich history and heritage of a city by visiting landmarks, learning about local traditions, and engaging with the local community.

Furthermore, urban areas offer a wide range of entertainment options. From live music performances to theater shows and sporting events, cities provide a diverse array of entertainment choices that cater to different interests and preferences. The nightlife in cities is particularly vibrant, with numerous bars, clubs, and lounges offering a lively and energetic atmosphere.

In conclusion, urban travel offers a unique and exciting experience that is distinct from rural travel. The fast-paced and vibrant atmosphere of cities, coupled with their cultural and entertainment opportunities, make urban areas a magnet for travelers seeking a dynamic and enriching experience. So, whether you’re a fan of architectural marvels, cultural immersion, or vibrant nightlife, urban travel has something to offer for everyone.

Modes of Transportation in Rural and Urban Travel

Modes of transportation.

When it comes to traveling, one of the key aspects to consider is the mode of transportation. Whether you’re exploring rural areas or urban cities, the transportation options available can greatly impact your overall experience. Let’s delve into the contrasting modes of transportation in rural and urban travel.

Compare transportation options in rural and urban areas

In rural areas, personal vehicles are often the primary mode of transportation. Due to the limited public transportation infrastructure, owning a car becomes essential for getting around. This reliance on personal vehicles offers travelers the flexibility to explore remote areas at their own pace. However, it’s important to note that rural roads may be less developed and navigation can be challenging, especially for those unfamiliar with the area.

On the other hand, urban areas boast a wide array of transportation options. Public transportation systems such as buses, trains, and subways are readily available, providing convenient and affordable means of getting around. These networks are well-connected, allowing travelers to easily navigate through the city and reach various attractions. Additionally, urban areas often have ride-sharing services and bike-sharing programs , offering alternative and eco-friendly transportation options.

Discuss the convenience and accessibility of public transportation in cities

One of the major advantages of urban travel is the accessibility and convenience of public transportation. Cities are designed to accommodate a large population, resulting in extensive public transportation networks. Buses and trains run frequently, ensuring that travelers can reach their desired destinations without much hassle. Moreover, the presence of subway systems in many urban areas allows for quick and efficient travel, especially during peak hours when traffic congestion is common.

Public transportation in cities also offers the benefit of cost-effectiveness . Instead of spending money on fuel and parking fees, travelers can purchase affordable tickets or passes for unlimited rides. This makes it an attractive option for budget-conscious travelers who want to explore the city without breaking the bank.

Highlight the reliance on personal vehicles in rural areas

In contrast to urban travel, rural areas heavily rely on personal vehicles for transportation. The lack of comprehensive public transportation systems makes owning a car a necessity for residents and visitors alike. Travelers who prefer the freedom of exploring at their own pace will find that having a personal vehicle in rural areas is advantageous.

However, it’s important to consider the potential challenges that come with relying solely on personal vehicles in rural travel. Remote areas may have limited gas stations and repair facilities, so it’s crucial to plan ahead and ensure that you have enough fuel and necessary supplies. Additionally, navigating unfamiliar rural roads can be challenging, especially if GPS signals are weak or unavailable. It’s advisable to have a map or detailed directions to avoid getting lost.

In conclusion, the modes of transportation in rural and urban travel offer distinct experiences. While rural areas rely on personal vehicles for flexibility and exploration, urban areas provide the convenience and accessibility of public transportation. Consider your preferences and the nature of your travel destination when choosing the mode of transportation that best suits your needs. Whether you prefer the open road or the bustling city streets, both rural and urban travel have their own unique charm waiting to be discovered.

Accommodation Options

When it comes to planning a trip, one of the most important considerations is finding the perfect place to stay. The choice of accommodation can greatly impact the overall travel experience. In this section, we will compare the accommodation options available in rural and urban areas, highlighting the unique features of each.

Compare accommodation choices in rural and urban areas

In rural areas, travelers often have the opportunity to stay in charming bed and breakfasts or farm stays. These accommodations provide a cozy and intimate atmosphere, allowing visitors to immerse themselves in the local culture and experience the authentic rural lifestyle. Bed and breakfasts are known for their warm hospitality and homemade breakfasts, while farm stays offer the chance to get involved in farm activities and enjoy fresh produce.

On the other hand, urban areas offer a wide range of accommodation choices to suit every traveler’s preferences and budget. Hotels, hostels, and vacation rentals are commonly found in cities, providing a variety of options for different types of travelers. Hotels offer convenience and comfort, with amenities such as room service and fitness centers. Hostels are a popular choice for budget-conscious travelers, providing affordable dormitory-style accommodations and a chance to meet fellow travelers. Vacation rentals, such as apartments or houses, offer a more home-like experience and the opportunity to live like a local.

Discuss the availability of hotels, hostels, and vacation rentals in cities

Cities are known for their abundance of hotels, ranging from budget-friendly options to luxurious five-star establishments. The availability of hotels in urban areas ensures that travelers have a wide range of choices to suit their preferences and budget. Whether you prefer a boutique hotel in the heart of the city or a chain hotel with all the amenities, cities have it all.

Hostels are also prevalent in urban areas, catering to budget travelers and backpackers. These dormitory-style accommodations offer a social atmosphere, with common areas where travelers can mingle and share their experiences. Hostels are a great option for those looking to meet fellow travelers and make new friends while exploring the city.

Vacation rentals have gained popularity in recent years, offering a more unique and personalized experience. Many urban areas have a wide selection of vacation rentals available, ranging from apartments in trendy neighborhoods to spacious houses in residential areas. Vacation rentals provide the opportunity to live like a local, with amenities such as a kitchen and laundry facilities, making them ideal for longer stays or families traveling together.

Highlight the charm of bed and breakfasts and farm stays in rural areas

One of the unique aspects of rural travel is the opportunity to stay in charming bed and breakfasts or farm stays. Bed and breakfasts are often located in historic buildings or picturesque countryside settings, offering a cozy and intimate atmosphere. The hosts of these establishments are known for their warm hospitality, providing personalized service and insider tips on the best local attractions.

Farm stays, as the name suggests, allow travelers to stay on a working farm and experience the rural lifestyle firsthand. These accommodations offer a unique opportunity to get involved in farm activities, such as milking cows or harvesting crops. Farm stays often provide farm-fresh meals, allowing guests to savor the taste of local produce and experience farm-to-table dining.

In conclusion, the accommodation options in rural and urban areas offer distinct experiences for travelers. Rural areas provide the charm of bed and breakfasts and farm stays, allowing visitors to immerse themselves in the local culture and lifestyle. Urban areas, on the other hand, offer a wide range of choices, from hotels to hostels and vacation rentals, catering to different preferences and budgets. Whether you prefer the tranquility of rural accommodations or the convenience of urban options, both types of travel offer unique and memorable experiences.

Activities and Attractions

When it comes to activities and attractions , rural and urban areas offer unique experiences that cater to different interests. Whether you prefer exploring natural wonders or immersing yourself in cultural sites, both rural and urban travel have something to offer. Let’s delve into the types of activities and attractions you can expect in each setting.

Compare the types of activities and attractions in rural and urban areas

Rural areas are known for their natural wonders and outdoor adventures . If you enjoy hiking, camping, or wildlife spotting, rural travel is perfect for you. Imagine exploring picturesque hiking trails, breathing in the fresh air, and being surrounded by breathtaking landscapes. From national parks to scenic lakes, rural areas provide a serene escape from the hustle and bustle of city life.

On the other hand, urban areas offer a plethora of cultural sites , museums , and nightlife . If you’re a history buff or an art enthusiast, cities are the place to be. You can visit famous landmarks, such as museums, art galleries, and historical monuments. Additionally, urban areas are renowned for their vibrant nightlife, with numerous bars, clubs, and theaters to keep you entertained.

Discuss the natural wonders and outdoor adventures in rural areas

Rural travel allows you to immerse yourself in nature’s beauty . You can embark on hiking expeditions through lush forests, witness stunning waterfalls, or go kayaking in tranquil rivers. The opportunities for outdoor adventures are endless. Whether it’s birdwatching, fishing, or horseback riding, rural areas provide a chance to reconnect with nature and engage in thrilling activities.

Highlight the cultural sites, museums, and nightlife in urban areas

Urban areas are a treasure trove of cultural experiences . You can explore world-class museums, such as art museums, history museums, and science museums, which offer a glimpse into various aspects of human civilization. Additionally, cities host numerous cultural events, such as music festivals, theater performances, and art exhibitions, allowing you to indulge in the local arts scene.

When the sun sets, cities come alive with their vibrant nightlife . You can enjoy live music performances, dance the night away at trendy clubs, or savor delicious cuisine at upscale restaurants. Urban areas offer a diverse range of entertainment options that cater to different tastes and preferences.

In conclusion, both rural and urban travel provide distinct activities and attractions that cater to different interests. Whether you prefer the tranquility of nature or the vibrancy of city life, there is something for everyone. So, when planning your next trip, consider the type of experiences you seek and choose between the natural wonders of rural areas or the cultural richness of urban areas.

Food and Dining Experiences

When it comes to food and dining experiences, rural and urban areas offer distinct options that cater to different preferences and tastes. Let’s explore the contrasting culinary scenes in both settings.

Compare the food and dining options in rural and urban areas

In rural areas, farm-to-table dining experiences are a highlight. The focus is on fresh, locally sourced ingredients that are often grown or produced within the community. This emphasis on local cuisine allows travelers to savor the authentic flavors of the region. From farm-fresh vegetables to artisanal cheeses and meats, rural areas offer a unique opportunity to indulge in traditional and wholesome dishes.

On the other hand, urban areas boast a diverse culinary scene with a wide range of international cuisines. Cities attract talented chefs from around the world, resulting in an abundance of international cuisine options. Whether you’re craving sushi, pasta, or curry, urban areas provide a melting pot of flavors that cater to all taste buds. The vibrant food scenes in cities often include trendy restaurants, food trucks, and bustling markets, offering a plethora of choices for food enthusiasts.

Discuss the farm-to-table and local cuisine in rural areas

In rural areas, the connection to the land and local produce is deeply ingrained in the culinary culture. Farm-to-table dining experiences allow travelers to taste the freshest ingredients while supporting local farmers and producers. Many rural establishments offer menus that change with the seasons, showcasing the bounty of the region. From hearty stews made with locally raised meats to freshly baked bread made from locally milled grains, rural areas provide an authentic and sustainable dining experience.

Additionally, rural areas often feature bed and breakfasts and farm stays that offer homemade meals prepared with love and care. These accommodations not only provide a comfortable place to stay but also give travelers the opportunity to enjoy home-cooked meals made with local ingredients. The warm hospitality and personalized dining experiences in rural areas create a sense of connection and community.

Highlight the diverse culinary scenes and international cuisine in cities

Urban areas are known for their diverse culinary scenes, where travelers can embark on a global gastronomic adventure. From Michelin-starred restaurants to hole-in-the-wall eateries, cities offer an array of dining options to suit every palate and budget. The cultural diversity in urban areas translates into a rich tapestry of flavors, with restaurants specializing in cuisines from around the world.

Moreover, cities often host food festivals and events that celebrate different cultures and cuisines. These events provide an opportunity to sample a variety of dishes in a festive and lively atmosphere. Whether it’s street food, fine dining, or fusion cuisine, urban areas offer endless possibilities for food enthusiasts to indulge their taste buds.

In conclusion, the food and dining experiences in rural and urban areas present contrasting yet equally enticing options. Rural areas offer farm-to-table experiences and a chance to immerse oneself in the local cuisine, while urban areas provide a diverse culinary scene with international flavors. Whether you prefer the simplicity and authenticity of rural dining or the excitement and variety of urban gastronomy, both types of travel offer unforgettable culinary adventures. So why not consider exploring both rural and urban areas to truly savor the best of both worlds? Bon appétit!

Budget Considerations

When planning a trip, one of the most important factors to consider is the budget. Traveling can be an expensive endeavor, and it’s essential to understand the cost differences between rural and urban areas. Let’s take a closer look at the budget considerations for both types of travel.

Compare the cost of travel in rural and urban areas

When it comes to the overall cost of travel, rural areas tend to be more budget-friendly compared to urban areas. This is primarily because rural destinations often have lower accommodation and transportation costs. In rural areas, you can find affordable bed and breakfasts or even farm stays that provide a unique and charming experience at a fraction of the cost of a hotel in the city.

On the other hand, urban areas offer a wide range of accommodation options, from hotels and hostels to vacation rentals . While these options provide convenience and comfort, they can be more expensive, especially in popular cities. Additionally, the cost of dining out and entertainment in urban areas can also be higher compared to rural areas.

Discuss the affordability of accommodations, transportation, and attractions

In terms of transportation , urban areas often have a more developed public transportation system, which can be a cost-effective way to get around. Cities typically have buses, trains, and subways that provide convenient and affordable transportation options for travelers. This can help save money on taxi fares or car rentals, which are more common in rural areas where public transportation may be limited.

When it comes to attractions , both rural and urban areas offer unique experiences. However, the cost of attractions can vary. In rural areas, you’ll often find natural wonders and outdoor activities that are either free or have a minimal entrance fee. Urban areas, on the other hand, have a wide range of attractions such as museums, cultural sites, and nightlife, which may require admission fees or cover charges.

Highlight potential savings or expenses in each type of travel

While rural travel may offer savings in terms of accommodation and transportation, it’s essential to consider other factors that may impact your budget. For example, if you plan to explore remote areas in rural destinations, you may need to rent a car or hire a guide, which can add to your expenses. Additionally, dining options in rural areas may be limited, and you may need to factor in the cost of groceries or eating at local restaurants.

In urban areas, the cost of living is generally higher, which can impact your overall budget. However, cities often have a wide range of budget-friendly options available, such as street food stalls or affordable local eateries. By exploring these options, you can still enjoy the culinary scene without breaking the bank.

In conclusion, when considering budget considerations for travel, it’s important to weigh the pros and cons of both rural and urban areas. While rural travel may offer savings in terms of accommodation and transportation, urban travel provides a diverse range of attractions and dining experiences. By carefully planning your trip and considering your budget, you can have a memorable travel experience, regardless of whether you choose rural or urban destinations.

Unveiling The Shelf Life: How Long Does Citric Acid Last?

Unveiling The True Value: How Much Is Jcoin Worth In Today’s Market?

Rebooting Your Booze: How To Reset Alcohol Content

Quick And Easy: Mastering The Art Of Thawing Tuna

Unveiling The Dynamic Interplay: How Physical And Human Systems Shape A Place

Unlocking The Power: How Long Does It Take For Royal Honey To Activate?

Mastering Residency: A Guide On How To Study Effectively

Mastering The Art Of Die Cast Mold Making: A Step-By-Step Guide

Unveiling The Energy Consumption Of Water Coolers: How Much Electricity Do They Really Use?

Mastering Virtual Reality: Unlocking The Secrets To Altering Your Height

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Top 20 Slang For Travel – Meaning & Usage

Whether you’re a seasoned globetrotter or planning your first adventure, staying up to date with the latest slang for travel can make your journeys even more exciting. From “wanderlust” to “jet lagged,” our team has scoured the globe to bring you a curated list of the most trendy and essential travel slang. So pack your bags, get ready to explore, and let us be your guide to the lingo of the wanderlusters!

Click above to generate some slangs

1. Hit the road

This phrase is used to indicate the beginning of a trip or adventure. It can be used both literally and figuratively.

- For example , “We packed up the car and hit the road for our cross-country road trip.”

- Someone might say , “I’ve been stuck at home for too long, it’s time to hit the road and explore.”

- In a figurative sense , a person might say, “I’ve accomplished all my goals here, it’s time to hit the road and find new opportunities.”

2. Globetrotter

This term refers to someone who travels frequently or extensively to various parts of the world.

- For instance , “As a globetrotter, she has visited over 50 countries.”

- A travel blogger might describe themselves as a globetrotter , saying, “Follow my adventures as a globetrotter exploring the world.”

- In a conversation about travel , someone might ask, “Are you a globetrotter or do you prefer to stay in one place?”

3. Take off

This phrase is used to indicate the start of a journey or flight. It can be used for both literal and figurative departures.

- For example , “The plane is about to take off, please fasten your seatbelts.”

- Someone might say , “I’m taking off for my vacation tomorrow, can’t wait to relax on the beach.”

- In a figurative sense , a person might say, “I need to take off from work early today to attend a family event.”

This slang phrase means to leave for a trip or vacation in a hurry or without much notice.

- For instance , “She jetted off to Paris for a weekend getaway.”

- A friend might say , “I’m jetting off to visit my family in another state.”

- In a conversation about travel plans , someone might ask, “When are you jetting off on your next adventure?”

5. Get a little R&R

This phrase is an abbreviation for “rest and relaxation.” It refers to taking time off to relax and unwind from daily stress or work.

- For example , “After a busy week, I’m looking forward to getting a little R&R at the beach.”

- Someone might say , “I’m planning a spa weekend to get some much-needed R&R.”

- In a discussion about self-care , a person might suggest, “Take some time for yourself and get a little R&R to recharge.”

6. Backpacking

Backpacking refers to a style of travel where individuals carry their belongings in a backpack and typically stay in budget accommodations or camp. It often involves exploring multiple destinations and immersing oneself in the local culture.

- For example , “I’m going backpacking through Europe this summer.”

- A traveler might say , “Backpacking allows you to have more flexibility and freedom in your journey.”

- Someone might ask , “Do you have any tips for backpacking on a tight budget?”

7. Sightseeing

Sightseeing involves visiting famous landmarks, attractions, or points of interest in a particular destination. It often includes activities such as taking guided tours, visiting museums, or exploring natural wonders.

- For instance , “I spent the day sightseeing in Paris and saw the Eiffel Tower.”

- A traveler might say , “Sightseeing is a great way to learn about the history and culture of a new place.”

- Someone might ask , “What are the must-see sights when sightseeing in New York City?”

Wandering refers to exploring a destination without a specific plan or itinerary. It involves taking spontaneous detours, getting lost in the streets, and embracing the unexpected discoveries along the way.

- For example , “I love to wander through the narrow alleys of old cities.”

- A traveler might say , “Wandering allows you to stumble upon hidden gems and experience the local vibe.”

- Someone might ask , “Do you have any tips for wandering around a new city safely?”

Roaming involves moving freely and aimlessly, without a specific purpose or destination in mind. It often implies a sense of adventure and exploration, as one roams through different places and experiences.

- For instance , “I spent the day roaming the streets of Tokyo.”

- A traveler might say , “Roaming allows you to embrace spontaneity and go wherever your curiosity takes you.”

- Someone might ask , “What are the best neighborhoods to roam around in London?”

Cruising refers to traveling in a relaxed and leisurely manner, often by ship. It can also refer to driving or moving smoothly and effortlessly through a destination, enjoying the scenery and taking in the surroundings.

- For example , “We went on a Caribbean cruise and visited multiple islands.”

- A traveler might say , “Cruising allows you to enjoy a stress-free vacation and explore different ports of call.”

- Someone might ask , “What are the best cruise destinations for first-time travelers?”

11. Wanderer

A wanderer is someone who travels aimlessly or without a specific destination. It can also refer to someone who enjoys exploring new places and experiencing different cultures.

- For example , “He quit his job and became a wanderer, traveling from country to country.”

- A travel blogger might describe themselves as a wanderer , saying, “I’m always on the move, seeking new adventures.”

- In a conversation about travel , someone might ask, “Are you more of a planner or a wanderer?”

12. Road tripper

A road tripper is someone who enjoys traveling long distances by car, often taking a leisurely route and making stops along the way to explore different places.

- For instance , “We’re going on a road trip across the country and plan to visit several national parks.”

- A group of friends might say , “Let’s gather some snacks and hit the road as road trippers.”

- In a discussion about travel preferences , someone might ask, “Are you a road tripper or do you prefer flying?”

13. Travel enthusiast

A travel enthusiast is someone who has a strong interest in and passion for traveling. They enjoy exploring new destinations, trying new experiences, and immersing themselves in different cultures.

- For example , “She’s a travel enthusiast who has visited over 50 countries.”

- A travel blogger might describe themselves as a travel enthusiast , saying, “I’m constantly planning my next adventure.”

- In a conversation about hobbies , someone might ask, “Are you a travel enthusiast? Where have you been?”

14. Explore new horizons

To explore new horizons means to venture into unfamiliar territories or to try new travel experiences. It refers to the act of broadening one’s travel experiences and seeking out new destinations or activities.

- For instance , “I’m ready to explore new horizons and visit countries I’ve never been to before.”

- A travel agency might advertise , “Let us help you explore new horizons with our unique travel packages.”

- In a conversation about travel goals , someone might say, “I want to explore new horizons and step out of my comfort zone.”

15. Adventure seeker

An adventure seeker is someone who actively seeks out thrilling and exciting experiences while traveling. They enjoy activities such as hiking, skydiving, and exploring challenging terrains.

- For example , “He’s an adventure seeker who loves bungee jumping and rock climbing.”

- An adventure travel company might target adventure seekers , saying, “Join us for adrenaline-pumping experiences around the world.”

- In a discussion about travel preferences , someone might ask, “Are you more of a beach relaxer or an adventure seeker?”

16. Travel aficionado

This term refers to someone who is extremely passionate and knowledgeable about travel. A travel aficionado is someone who has a deep love for exploring new places and experiencing different cultures.

- For example , a travel aficionado might say, “I’ve been to over 50 countries and counting. Traveling is my biggest passion.”

- In a conversation about favorite destinations , a person might ask, “Any recommendations for a travel aficionado like me?”

- Someone might describe themselves as a travel aficionado by saying , “I spend all my free time planning my next adventure. I’m a true travel aficionado.”

17. Jet off to paradise

This phrase is used to describe traveling to a beautiful, exotic location, typically a tropical paradise. It implies a sense of excitement and luxury associated with traveling to a dream destination.

- For instance , someone might say, “I can’t wait to jet off to paradise and relax on the beach.”

- In a conversation about vacation plans , a person might say, “We’re jetting off to paradise next month for our honeymoon.”

- A travel blogger might write , “If you’re looking to escape the cold, jet off to paradise and enjoy the crystal-clear waters and white sandy beaches.”

18. Travel the world

This phrase is a common expression used to describe the act of traveling to various countries and experiencing different cultures. It emphasizes the idea of exploring and broadening one’s horizons through travel.

- For example , someone might say, “My dream is to quit my job and travel the world.”

- In a conversation about travel goals , a person might ask, “Have you ever wanted to travel the world and see all the wonders it has to offer?”

- A travel vlogger might say , “I’ve been lucky enough to travel the world and document my adventures on YouTube.”

19. Go on a journey

This phrase is used to describe the act of starting a new travel experience or adventure. It conveys a sense of excitement and anticipation for what lies ahead.

- For instance , someone might say, “I’m ready to go on a journey and explore new places.”

- In a conversation about travel plans , a person might ask, “Where are you going on your next journey?”

- A travel writer might describe their latest trip by saying , “I recently went on a journey through Europe, visiting multiple countries and immersing myself in the local culture.”

20. Travel in style

This phrase is used to describe traveling with a sense of luxury and style. It implies that the person is not just focused on getting from one place to another, but also on enjoying the journey and making a statement with their travel choices.

- For example , someone might say, “I always travel in style, staying in the finest hotels and flying first class.”

- In a conversation about travel preferences , a person might ask, “Do you prefer to travel in style or are you more budget-conscious?”

- A travel influencer might post on social media , “Traveling in style is all about the little details. From designer luggage to luxury accommodations, I always make sure to travel in style.”

You may also like

Slang dictionary

Trippin’.

or trippin [ trip -in]

What does trippin' mean?

You trippin’ means you’re acting a fool, thinking crazy thoughts, or are maybe high on mushrooms. Trippin’ out is “freaking out” or “being extremely high.”

Related words:

- geekin’

- set trippin’

- sweatin’

Where does trippin’ come from?

In drug slang, a trip is a metaphor for the hallucinatory high produced by LSD, magic mushrooms, and other drugs. The term dates back to the 1920s.

When people are tripping on hallucinogenic drugs, they can act very erratic, which probably accounts for the use of trppin’ for “acting insane, foolish, or without thinking” in general slang by the late 1980s.

The slang set trippin’ surfaced in 1990s West Coast gang culture for “killing a gang rival to show off your power.” Set alludes to a subset of a larger gang (e.g., the Pirus are a set of the Bloods ) and trip is black slang for “lose control,” as we’ve seen. Hip-hop artists like Dr. Dre, Coolio, and the Wu-Tang Clang all mentioned set trippin’ , often just trippin’ for short, in their lyrics around this time.

Dr. Dre notably used trippin’ in the “go crazy” sense in his 1992 hip-hop classic, “Nothin’ but a G Thang”: “Never let me slip, ’cause if I slip, then I’m slippin’ / But if I got my nina, then you know I’m straight trippin’.”

Examples of trippin’

Who uses trippin’.

Trippin’ is widespread slang …

The expression you trippin’ is frequently used to call out someone thought to be acting out of line or foolish.

Ain’t no “male best friend” You trippin. Talking bout get some ice cream. https://t.co/V15YB3Ze6J — Keeg (@iamkeganyates) May 30, 2018

The slang is so common it inspired the title of a 1999 film, Trippin’ , starring Deon Richmond as a daydreamer who just can’t get his act together to become a writer and win his prettiest girl.

Trippin’ also gets used when referring to some beef (e.g., I’m not trippin’ over what she said about me). And, tripping is still widely used to refer to being high on hallucinogenic drugs and sometimes just being very high in general.

This is not meant to be a formal definition of trippin’ like most terms we define on Dictionary.com, but is rather an informal word summary that hopefully touches upon the key aspects of the meaning and usage of trippin’ that will help our users expand their word mastery.

- By clicking "Sign Up", you are accepting Dictionary.com Terms & Conditions and Privacy policies.

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other categories

- Famous People

- Fictional Characters

- Gender & Sexuality

- Historical & Current Events

- Pop Culture

- Tech & Science

- Translations

Urban Thesaurus

Urban Thesaurus finds slang words that are related to your search query.

Click words for definitions

- teletubbies

- journey cow

- [deep step]

- mushroom mountain

- dextromethorphan

- magic mushroom

- hurdling in the special olympics

- birthday eloping

- run errands

- kennedy catholic high school

- hiking the appalachian trail

- tripping face nuggets

- fluggaenkoecchicebolsen

- procrastipacking

- lollylopzkizmal

- reika moment

- bad granola

- fornication vacation

- ebola troll

- fair winds & following seas

- business trip

Popular Slang Searches

Slang for trip.

As you've probably noticed, the slang synonyms for " trip " are listed above. Note that due to the nature of the algorithm, some results returned by your query may only be concepts, ideas or words that are related to " trip " (perhaps tenuously). This is simply due to the way the search algorithm works.

You might also have noticed that many of the synonyms or related slang words are racist/sexist/offensive/downright appalling - that's mostly thanks to the lovely community over at Urban Dictionary (not affiliated with Urban Thesaurus). Urban Thesaurus crawls the web and collects millions of different slang terms, many of which come from UD and turn out to be really terrible and insensitive (this is the nature of urban slang, I suppose). Hopefully the related words and synonyms for " trip " are a little tamer than average.

The Urban Thesaurus was created by indexing millions of different slang terms which are defined on sites like Urban Dictionary . These indexes are then used to find usage correlations between slang terms. The official Urban Dictionary API is used to show the hover-definitions. Note that this thesaurus is not in any way affiliated with Urban Dictionary.

Due to the way the algorithm works, the thesaurus gives you mostly related slang words, rather than exact synonyms. The higher the terms are in the list, the more likely that they're relevant to the word or phrase that you searched for. The search algorithm handles phrases and strings of words quite well, so for example if you want words that are related to lol and rofl you can type in lol rofl and it should give you a pile of related slang terms. Or you might try boyfriend or girlfriend to get words that can mean either one of these (e.g. bae ). Please also note that due to the nature of the internet (and especially UD), there will often be many terrible and offensive terms in the results.

There is still lots of work to be done to get this slang thesaurus to give consistently good results, but I think it's at the stage where it could be useful to people, which is why I released it.

Special thanks to the contributors of the open-source code that was used in this project: @krisk , @HubSpot , and @mongodb .

Finally, you might like to check out the growing collection of curated slang words for different topics over at Slangpedia .

Please note that Urban Thesaurus uses third party scripts (such as Google Analytics and advertisements) which use cookies. To learn more, see the privacy policy .

Recent Slang Thesaurus Queries

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 31 May 2023

Estimating urban spatial structure based on remote sensing data

- Masanobu Kii 1 ,

- Tetsuya Tamaki 2 ,

- Tatsuya Suzuki 2 &

- Atsuko Nonomura 2

Scientific Reports volume 13 , Article number: 8804 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2534 Accesses

4 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Socioeconomic scenarios

- Sustainability

Understanding the spatial structure of a city is essential for formulating a spatial strategy for that city. In this study, we propose a method for analyzing the functional spatial structure of cities based on satellite remote sensing data. In this method, we first assume that urban functions consist of residential and central functions, and that these functions are measured by trip attraction by purpose. Next, we develop a model to explain trip attraction using remote sensing data, and estimate trip attraction on a grid basis. Using the estimated trip attraction, we created a contour tree to identify the spatial extent of the city and the hierarchical structure of the central functions of the city. As a result of applying this method to the Tokyo metropolitan area, we found that (1) our method reproduced 84% of urban areas and 94% of non-urban areas defined by the government, (2) our method extracted 848 urban centers, and their size distribution followed a Pareto distribution, and (3) the top-ranking urban centers were consistent with the districts defined in the master plans for the metropolitan area. Based on the results, we discussed the applicability of our method to urban structure analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Ghost roads and the destruction of Asia-Pacific tropical forests

Disappearing cities on US coasts

Heat health risk assessment in Philippine cities using remotely sensed data and social-ecological indicators

Introduction.

Understanding the spatial structure of a city is essential for formulating a spatial strategy for that city. For this reason, many city officials and planners devote considerable resources to maintaining accurate data on the cities’ geographic features. Perhaps the two most crucial features are the spatial extent of the city and the layout of the centers of people’s activities. Classical urban economic models describe a mechanism by which transportation costs and land rents determine the extent and density of a city under a monocentric structure 1 ; however, many large cities have expanded and developed to have multiple urban centers because of population growth and advances in transportation technology 2 , 3 . Beyond their relevance to urban planning and governance, the extent of a city and the location of its urban centers have a significant effect on the lives of citizens—through their choice of residence and daily commute—in addition to disaster resilience 4 , 5 ; the peri-urban ecosystem and natural environment 6 , 7 ; and, more recently, infectious diseases 8 , 9 .

For this reason, various methods for quantitatively analyzing the spatial structure of cities have been explored. Perhaps the simplest strategy is to identify urban areas and population centers by analyzing various forms of statistical data, such as spatial distributions of population and employment 10 , commuting and shopping traffic 11 , 12 , or activity density and concentration 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 . However, the use of statistical data has disadvantages: spatial units of data aggregation and observation frequencies vary from country to country and region to region, and measurements may be spatially coarse and infrequent. To address these challenges, recent studies have investigated methods to characterize urban structure using two alternative data sources: remote sensing data and mobile terminal location data. These data sources provide frequent measurements and high spatial resolution across extensive coverage areas, even in developing nations. Varieties of remote sensing data considered to date include various earth reflectances of the electromagnetic spectrum (see review paper 19 ), light detection and ranging 20 , synthetic aperture radar 21 , 22 , stereoscopic digital surface models (DSMs) 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , and nighttime lights 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 . In studies using mobile terminal data, researchers have considered the use of communication traffic data collected by mobile network operators 31 , check-in data for location-based social networks 32 , frequency of call detail records from mobile terminals 33 , 34 , 35 , and Google location histories 36 . However, the location data of cell phones are held by private companies, such as cell phone companies. The data are not disclosed to the public because of privacy protection concerns. By contrast, many remote sensing data are widely disclosed by public organizations.

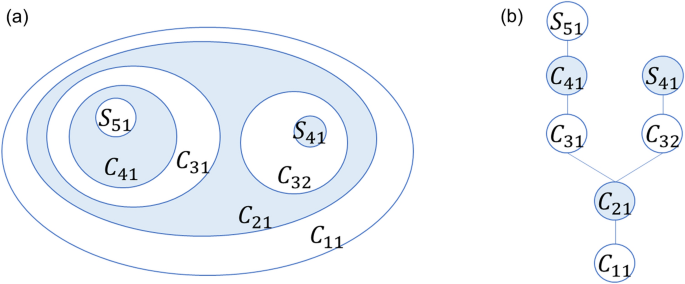

In one prominent study that captured urban centers in large cities using remote sensing data, Chen et al. 27 proposed a method to define urban centers using a nighttime light contour tree. They created a contour tree of nighttime lights for Shanghai and successfully detected the city center based on the threshold of nighttime lights. However, Chen et al. (1) defined the hierarchical level of urban centers using contour tree topology and it did not use the light intensity of urban center activity for the systematic activity level evaluation, and (2) set the threshold for urban center detection arbitrarily to match known urban centers that serve as references. The level of activity in city centers is essential information for urban planning and transportation planning; however, Chen et al. did not directly interpret nighttime light intensity in the planning context. They detected 33 urban centers in Shanghai with a population of more than 23 million, which means that they detected only major centers and ignored minor centers by truncating peaks below the threshold or averaging out small peaks.

The definition of urban center is ambiguous 26 . Therefore, various methodologies exist for the identification of polycentricity and subcenters, with different methods used in different studies. For example, Duranton and Puga 37 suggested that subcenters can range from large to small depending on their levels of functions. To address these issues, we propose a methodology to identify the hierarchical structure of all urban centers based on a contour tree, which reflects the activity intensity of urban centers.

The method proposed in this study is superior to existing methods in three respects. First, it evaluates the spatial distribution of urban activity using a model that transforms remote sensing data into trip attraction. As found by Burger and Meijers 11 , it is straightforward to understand the spatial distribution of urban activities as trip attraction, and to interpret its meaning in urban planning practice. A few studies have been conducted on the relationship between nighttime lights and traffic 38 , 39 . In this study, we employ statistical modeling to estimate trip attraction using remote sensing data. Specifically, we divide the traffic volume index into two categories: trips going out and trips returning home, based on the purpose of travel. This approach allows us to account for the empirical observation that the attraction volume of trips going out is influenced by the intensity of urban center activities, whereas the attraction volume of trips returning home is influenced by the intensity of residential areas. Thus, we can identify urban centers as the focal points of outgoing trips. We can recognize urban centers as places where going out trips are concentrated. By contrast, we can assume that the destination of a returning home trip is a residential area. Therefore, we can assume that the destinations of these two trips can define urban areas.

In previous studies, most land use and cover data classified land directly based on the surface reflectance spectrum. By incorporating the process of converting remote sensing data into trip attraction volume, we expect to be able to estimate urban areas that are more meaningful from the perspective of urban planning practice than conventional land use data. Using these models, we attempt to determine the spatial extent of the city and the location of city centers.

Second, we extract a comprehensive range of urban centers, from the major centers of the metropolitan area to local community centers, using the contour tree of an estimated going out trip attraction map. In the method of Chen et al., they defined the size and level of urban centers to be extracted using a specific threshold and ignored small centers. Our proposed method is unique in that it extracts a wide range of peaks of the trip attraction map as urban centers. Third, we use the topology information of the contour tree and measure the activity level of the extracted centers by cumulative trip attraction, including their hinterlands. This approach enables us to rank the centers while considering the overall structure of the city. It allows for an analysis that captures the competition among urban centers as well as the independence of suburban centers. This is not achievable when measuring the intensity of activity in urban centers solely based on local conditions, such as a threshold. Taking advantage of these features, in this study, we evolve a method for extracting the urban structure using remote sensing data. As discussed below, the proposed cumulative trip attraction index obtained by expanding the contour tree method achieved higher performance for urban center detection than the ordinary index obtained by the simple contour tree. This is an innovation in this study that advances previous research.

In this study, we use trip attraction as a functional variable of urban structure. We create a model with trip attraction as the dependent variable and morphological variables from remote sensing data as explanatory variables. We use nighttime light data and a DSM as input remote sensing data; however, these data can be replaced depending on the context. The trip attraction volume is statistical data and the unit of aggregation is the traffic analysis zone (TAZ). Generally, TAZs are smaller in the central area than in suburban areas, and TAZs are typically larger than the grid size of remote sensing data. We estimate the model of trip attraction using the data with TAZ as the spatial unit. By inputting grid-based remote sensing data into the estimated model, we can estimate spatially detailed traffic volume indices. We divide trip attraction according to the travel purpose into going out and return trips. We assume that each destination corresponds to a city center and residential area, and model each trip attraction. We use the estimated traffic volume indices to identify urban areas and urban centers. In particular, for urban centers, we replace the input information of the model proposed by Chen et al. from nighttime light with the estimated trip attraction density (TAD) to obtain a hierarchy of urban functions and their locations. Thus, we extract the spatial structure of the city. In the " Methods " section, we explain this analysis procedure in detail.

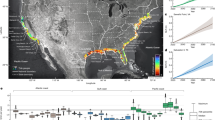

Regression analysis of trip attraction

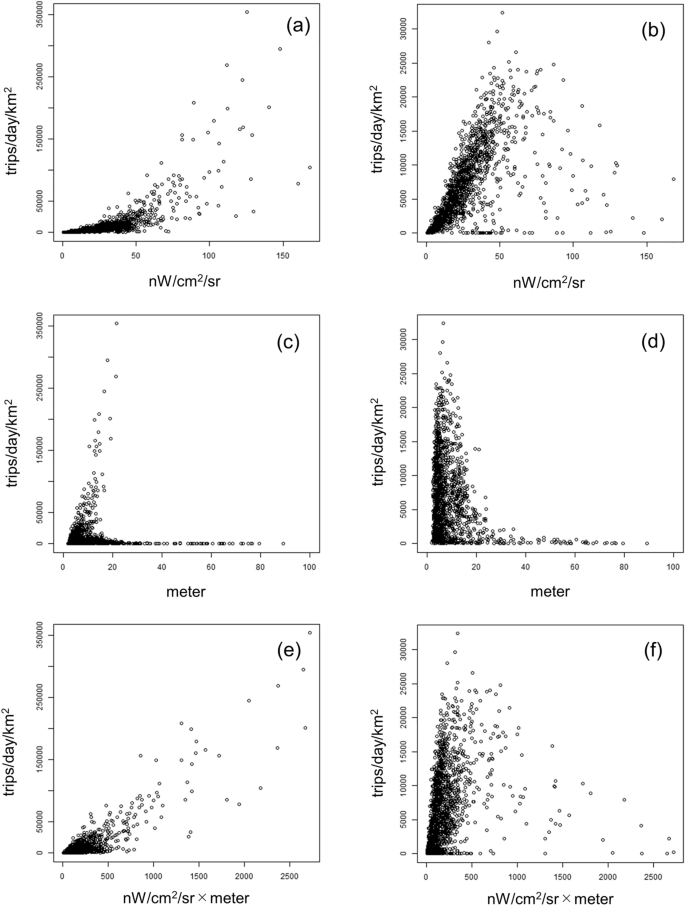

Before presenting the regression analysis, we check the necessity of the variable transformation of the dependent variable. We tested the parameters of the Box–Cox transformation 40 . The results demonstrated that the parameters were significant at the 1% level for rejecting the null hypothesis of the normality of dependent variable (λ = 1), except for the TAD for return trips with Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) nighttime lights (VNL), which was greater than or equal to 50 nW/cm 2 /sr (Table 1 ). Thus, the TAD for return trips with VNL ≥ 50 was not transformed, and the remainder of the variables were transformed with the parameters shown in Table 1 for the subsequent analysis.

To determine the regression model formulated in Eq. ( 3 ), we tested all combinations of VNL and altitude difference index (ADI) × VNL as explanatory variables. The details for the ADI are provided in the " Methods " section. We applied the Box–Tidwell transformation 41 to account for the nonlinearity of the effects of the explanatory variables. We assumed that the transformation parameters were unity if they were not significant. The results are shown in Table 2 .

The upper part of the table shows the results for zones with average VNL ≥ 50 nW/cm 2 /sr, and the lower part shows the results for zones with average VNL < 50 nW/cm 2 /sr. Additionally, (1)–(3) and (7)–(9) are the estimation results for going out and the remainder are the results for the return trip regression model. The notation "-" indicates that the parameter is not applicable.

First, considering the results of the Box–Tidwell transformations, the NA in model (3) means that the estimates diverged and could not be appropriately estimated. Additionally, all variables in models (4)–(6) and VNL × ADI in models (9) and (12) were not significant. We assumed that the influence of these variables was linear.

Next, considering the regression coefficients, all coefficients were significant at the 0.1% level, except for VNL in models (3) and (6) and VNL × ADI in models (9) and (12). Note that the coefficients of VNL in model (1) and VNL × ADI in model (11) were negative, which reflects the fact that the Box–Tidwell exponential was negative. Considering the significant parameters of the Box–Tidwell transformation and regression analysis, we observed that for VNL < 50 and VNL ≥ 50 going out trips, the higher the value of VNL or VNL × ADI, the higher the TAD. By contrast, in the model for return trips with VNL ≥ 50, the larger the values of VNL or VNL × ADI, the lower the TAD. This reflects the negative correlation between the TAD and the variables in the VNL ≥ 50 zone, as shown in Fig. 10 , and indicates that the TAD for return trips was low in the city center because the land use was specialized for business.

We considered R 2 between the estimated and observed values, where R 2 denotes the multiple correlation coefficient calculated for the Box–Cox-transformed dependent variable. We calculated R 2 (original) for the dependent variable after transforming the model estimates with the exponential power of the inverse of the Box–Cox parameter and returning to the original TAD scale. R 2 of the model with two variables, VNL and VNL × ADI, was naturally the highest, except for going out with VNL ≥ 50. For going out with VNL ≥ 50, R 2 of model (2) was higher because the Box–Tidwell transformation did not yield a solution in model (3). By contrast, one variable was not significant in any of models (6), (9), and (12) with two variables. R 2 and RMSE did not differ significantly from the model with only the variable that was considered significant in that model. Based on these results, we used (2) for going out with VNL ≥ 50, (5) for return trip with VNL ≥ 50, (7) for going out trip with VNL < 50, and (10) for return trip with VNL < 50.

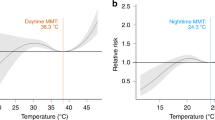

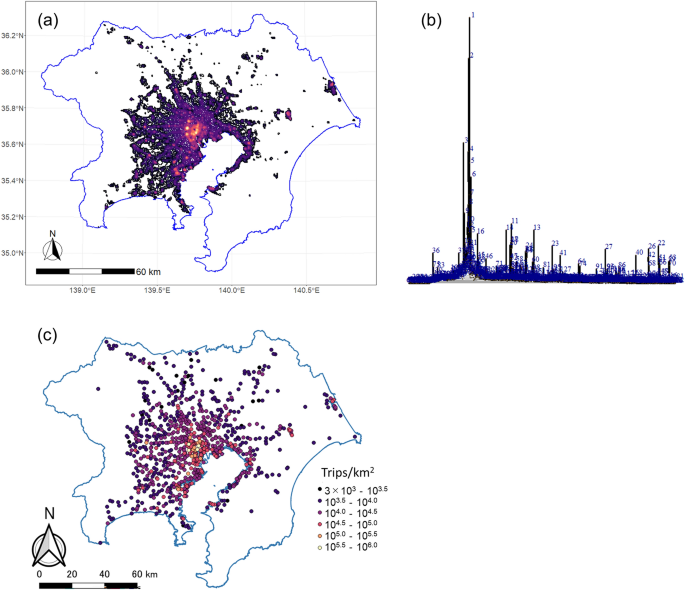

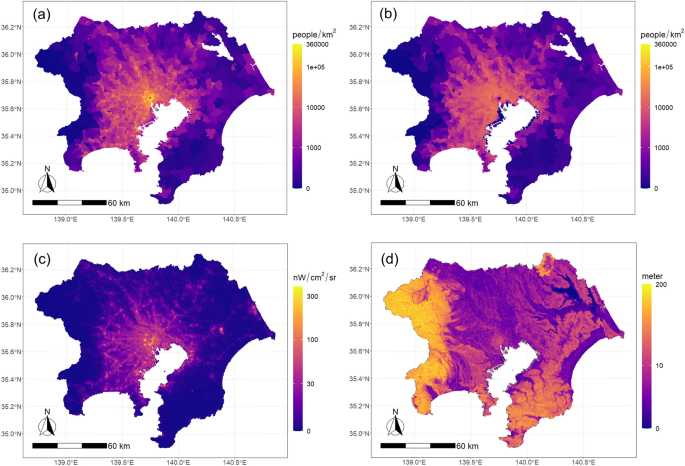

The model we obtained above is a simple estimation of the TAD using remote sensing data, but we obtained a certain level of reproducibility. The spatial distribution of estimation errors is shown in Fig. 1 . The upper panel of Fig. 1 shows the difference between the estimated and observed TAD, and the lower panel shows the relative error to the observed value. On the left is the going out trip and on the right is the return trip. There was a certain spatial autocorrelation for both going out and return trips. The model estimates were overestimated for the reclaimed areas along the coast of Tokyo Bay because most of these areas are used for the industrial sector. Industrial areas typically exhibit strong nighttime light emissions but tend to have relatively low trip attraction for people. Considering the lower panel, the relative error was larger in less populated zones at the outer edges. By contrast, in densely populated areas, the relative error was rather small. The details of the estimation error for the going out trip in VNL ≥ 50 zones are described in supplementary material S2 .

Spatial distribution of the estimation error: ( a ) error of the going out trip, ( b ) error of the return trip, ( c ) relative error of the going out trip, ( d ) relative error of the return trip (the maps were created with the software R 4.1.0 42 with packages sf 1.0.9 43 , stars 0.6.0 44 , ggplot2 3.4.0 45 , and ggspatial 1.1.7 46 . All maps presented in this paper below were created using the same software.).

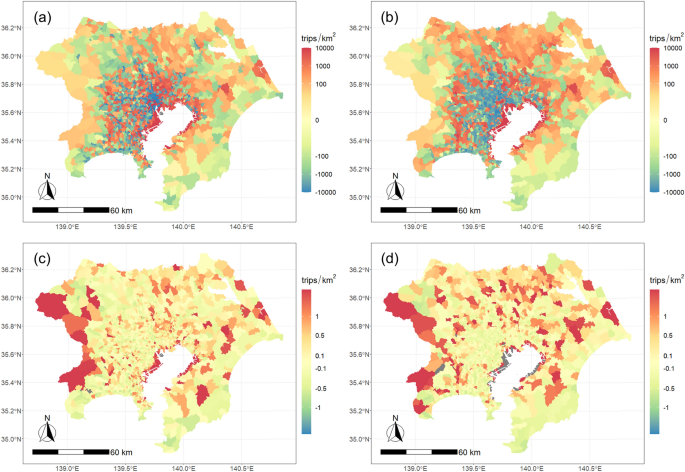

Urban structure detection on a grid system

We applied the above model to grid data to estimate the grid-based TAD. The results are shown in Fig. 2 . The figure shows that the overall trend of the target area was the same as that for the zone-based TAD in Fig. 9 , but the grid-based TAD provided higher spatial resolution than TAZ-based TAD, particularly in suburban areas.

Estimated TAD on the grid: ( a ) going out, ( b ) return.

In the following, we use this estimated grid-based TAD to analyze the extent of the urban area and the spatial distribution of city centers by applying the method described in " Methods " section.

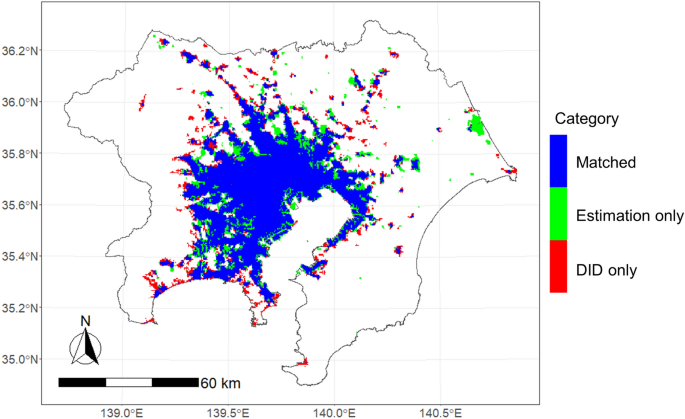

Estimation of the urban area

First, we estimated the urban area using Eqs. ( 4 )–( 6 ). We assumed that \(f_{u} \left( {q_{Hi} ,q_{Ei} } \right) = wq_{Hi} + \left( {1 - w} \right)q_{Ei}\) , and set weight \(w\) and threshold \(\delta_{M}\) to values that minimize the error from the current urban area. This minimization problem is formulated in Eq. ( 6 ). We defined the current urban area as a densely inhabited district (DID), which is a district with a population density of more than 4,000 people/km 2 and more than 5,000 people in adjacent areas, according to the Japanese census. As a result of the analysis, we estimated the threshold for minimizing the error to be \(\delta_{M}\) =2722 and the weight to be \(w\) = 0.461. The fit of the estimated urban area to the DID is shown in Fig. 3 .

Conformity of the estimated urban area to the DID.

Figure 3 shows that the estimated area and DID area generally matched in the central area of the metropolis, but there was a large error in the fringe area. In terms of the area, there were 2935 km 2 of grids where both areas matched, 687 km 2 of grids where only the estimated area was urban, and 538 km 2 of grids where only the DID was urban; compared with the total area of the DID, that is, 3474 km 2 , they were 84%, 20%, and 15%, respectively. The DIDs in the periphery were scattered, and remote sensing data-based indices, such as VNL and ADI, were unable to fully capture these urban areas. In particular, grids with a high proportion of natural land use, such as rivers and mountain forests, had a low average nighttime light intensity and were not considered as urban areas by the method. By contrast, there were many highways and large-scale factories in areas that were not DIDs but emitted strong nighttime light and were estimated as urban areas by the method. Although these facilities had a small residential population and did not fall under the category of DID, they were estimated to be urban areas by the method because of their strong nighttime light.

For reference, we compared the urban area defined by DID and that of the ESA CCI Land Cover (CCI-LC) time-series v2.0.7 47 dataset for 2015 as an example of a conventional method. Regarding the target area, the urban areas in both data coincided in the 3304 km2 grids, but only CCI-LC was urban in the 1972 km2 grids and only DID was urban in the 170 km2 grids. This means that the urban area of CCI-LC was more than twice the urban area of DID. Clearly, the urban areas differ according to their definition. Here, the models used for CCI-LC were not calibrated to represent DID. It is likely that conventional methods would be more suitable for our specific urban areas of interest if the models used for CCI-LC were calibrated accordingly. However, our approach is much simpler than recent sophisticated land use and cover classification methods. We expect it to be relatively easy to calibrate, particularly in urban areas. Further discussion on accuracy is provided in supplementary material S3 .

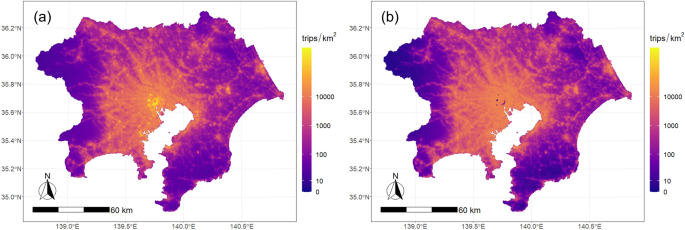

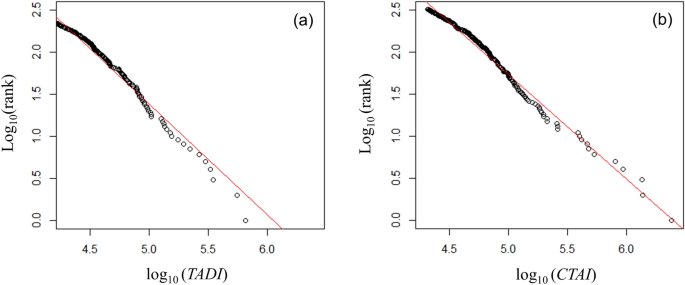

Estimation of urban centers

Next, we extracted the urban centers using the TAD for going out. For grids with a TAD of more than 3,000 trips/km 2 , we created a contour at a level of every 1,000 trips/km 2 , and created a contour tree using the " Methods " described in methods section. The number of contour levels was 653, and the total number of created contours was 7960, of which 848 were seeds. The created contour, its contour tree, and seeds are shown in Fig. 4 .

Results of urban center detection: ( a ) contour, ( b ) contour tree, ( c ) seeds.

We created the contour tree using the "igraph" package v1.2.6 of "R" 48 . We based the layout on the Reingold–Tilford graph layout algorithm 49 , and the height direction pseudo-represents the TAD of each contour. Additionally, in Fig. 4 b, we only assigned numbers to the seeds of the contour. The figure shows that seeds with a high TAD are close to each other on the graph, but seeds with a medium TAD are widely distributed, and many seeds have a low TAD. Some urban centers are formed by seeds and their hinterland overall. We evaluated the urban centers using two indices: the original TAD index (TADI) and cumulative trip attraction index (CTAI) at the seed. Cumulative trip attraction is defined in " Methods " section. Figure 5 shows the rank size plot of both indices. The figure shows that both followed a Pareto distribution. We excluded urban centers with fewer than 15,000 trips/km 2 for the TADI and fewer than 20,700 trips for the CTAI. Therefore, 281 locations are shown for the former and 326 locations for the latter. The values of the Pareto exponent were − 1.32 and − 1.25, respectively. This result implies that the CTAI had a slightly more concentrated distribution than the TADI.

Rank size plot of the trip attraction indices for urban centers: ( a ) TADI, ( b ) CTAI.

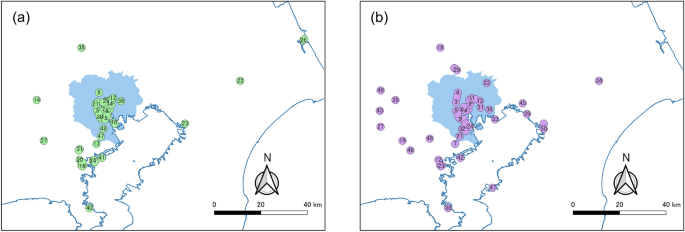

Figure 6 shows the locations of the top 50 urban centers for both indices. The blue zone indicates the 23 wards of Tokyo, that is, the central area of the Tokyo metropolitan area. The figure shows that, although both indices had the largest number of urban centers in the 23 wards, the TADI had a higher concentration of urban centers and fewer urban centers outside the 23 wards. On the other hand, CTAI identified a greater number of urban centers outside the 23 wards.

Extracted top 50 urban centers: ( a ) TADI at the seed, ( b ) cumulative trip attraction.

In the "Guidelines for the Development of the Central Area of the Special Wards of Tokyo" formulated by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government in 1997, the area from the vicinity of Tokyo Station to Shimbashi was designated as the central area of Tokyo. Regarding subcenters, Shinjuku, Shibuya, and Ikebukuro were designated in the National Central Region Development Plan for the Tokyo Metropolitan Area in 1958. Ueno/Asakusa, Kinshicho/Kameido, and Osaki were designated in the Long-Term Plan for the Tokyo Metropolis formulated in 1982. The Tokyo Rinkai subcenter was designated in the Second Long-Term Plan for the Tokyo Metropolis formulated in 1986. In 1986, the National Central Region Basic Plan for the Tokyo metropolitan area called for the development of business core cities on the periphery of the metropolitan area to alleviate congestion problems in city centers. In the current version of the National Central Region Development Plan, Yokohama/Kawasaki, Atsugi, Machida/Sagamihara, Hachioji/Tachikawa/Tama, Ome, Kawagoe, Kumagaya, Saitama, Kasukabe/Koshigaya, Kashiwa, Tsuchiura/Tsukuba/Ushiku, Narita, Chiba, and Kisarazu are designated as business cities to promote the agglomeration of business functions.

The locations of these urban centers are shown in Fig. 7 , and the ranks of these urban centers by the two indices are shown in Table 3 . Most of the centers in the special wards are ranked within the top 50. By contrast, some of the business core cities are ranked lower than 400th, which suggests that the dispersion of business functions in the plan has not progressed sufficiently. Comparing the ranks of the top centers, in the TADI, Shinjuku, the subcenter, is ranked first, and Shinbashi and Tokyo, the city center, are ranked second and fourth, respectively. In the CTAI, Shinbashi and Tokyo are ranked first and second, respectively, and Shinjuku, the subcenter, is ranked third. This suggests that the CTAI is more suitable for the positioning of urban centers as indicated in administrative plans.

Locations of urban centers in administrative plans: ( a ) centers outside the special wards of Tokyo, ( b ) centers inside the special wards of Tokyo.