Your browser is not supported for this experience. We recommend using Chrome, Firefox, Edge, or Safari.

visitors guide

Sign up for our

Enewsletter.

Historic Shirley

Nine Generations of Captivity

In 1613 Lord Thomas West received a 4,000-acre grant of land from the King of England to establish a settlement on the upper James River. The land on the north side of the river was settled in 1615 creating the earliest English-speaking settlement in what we know today as Charles City County. The settlement was named West and Sherley Hundred after West’s own family and that of his wife Lady Cessalye Shirley. A Roll of the Living made in 1623 counted 45 men, women and children alive at West and Shirley Hundred. The Roll of the Dead made at the same time, counted 11 dead, including two Indians, living within the settlement and one “negar,” likely a captive African arriving in 1619 on the White Lion or the Treasurer . Thus, Shirley is one of the earliest sites of the county’s African American history. Johannes Vingboons , “ Caert Vande Riuier Powhatan Geleg in Niew Nederlandt” (Ca. 1639). Plate 89 in Johannes Vongboons , “ Verzameling van pas- kaarten , dienede tot de vaart Oost- en Westindien .” [1628-1693]. Kaartenafdeling Terkeningen , Algemeen Rijksarchief , The Hague, Netherlands. Portrait of Lord Thomas West courtesy Encyclopedia of Virginia. Cesellye Sherley West, Lady de la Warr (d. 1661/62) , Circle of Cornelius Johnson , English, 17th Century , Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation JYF2005.54 , Gift of the Gladys and Franklin Clark Foundation .

About 40 years after this first settlement Edward Hill purchased land in Shirley Hundred that would become Historic Shirley. Twelve generations of Edward Hill’s descendants have lived at Shirley, while from 1656 to 1864 at least nine generations of enslaved laborers lived there too. Shirley welcomes all visitors, especially those who descend from its remarkable enslaved community. Historic Shirley is open for house and grounds tours daily, on a seasonal basis, and at no charge to members of Shirley’s enslaved descendant community. Shirley encourages descendants to connect with its enslaved descendant community group.

https://historicshirley.com/descendants/

Following his initial purchase of land Edward Hill was granted 2,060 acres in Shirley Hundred in 1660. At the same time, he claimed headrights – benefits attached to bringing settlers to Virginia — for the importation of two family members, 14 indentured servants (including two already dead), and three “negroes” named Joseph, Richard and John. In so doing, Edward Hill I established one of America’s oldest enslaved communities. Shirley’s workforce remained a mix of indentured Europeans, enslaved Africans and a few Indians until the death of Edward Hill III in 1726, by which time the work force had become mostly, if not entirely, enslaved Africans, and their often-mixed-race children enslaved at birth. While the Hill and Carter families up to the time of the Civil War benefited from nine generations of enslavement, Shirley’s enslaved families survived nine generations of captivity. Image courtesy https://www.slavevoyages.org/

This enslaver-enslaved relationship is depicted in an historically valuable portrait that hangs in Shirley. Recent scholarship has established that the allegorical style painting depicts a juvenile Edward Hill III, and was painted in England in the 1680s when he is thought to have been attending school. The child points to a mansion in the distance and figure standing between the child and the house. The figure—so darkened by time that it is difficult to see—is an African groom also in allegorical Roman costume, holding the reigns of a horse. It is the earliest known example of an African groom in colonial portraiture, and a possible figurative representation of Joseph, Richard or John, or their progeny.

The Story of Edward Hill

Photos courtesy Historic Shirley.

View the Next Section >>

Stolen From African Shores

A decade after Edward Hill I established Historic Shirley and passed it to Edward Hill II, the Royal African Trading Company was established in 1672 and given a monopoly over trade between Africa and the Colonies, including the importation of captive Africans. Only a small number of Africans were imported until the last two decades of the 1600s when the Black population of Virginia rose from 3,000 to 16,390. By 1720 the total was 26,559. According to one historian, a small number of Virginia gentry, men like Edward Hill II located in the section of Virginia where sweet-smelling tobacco was grown, were able to use their relations with British tobacco merchants to contract directly for the purchase and importation of Africans during those last twenty years. Thus, they were able to move to an all-enslaved workforce before Virginia planters with less wealth and influence were able to do the same. John C. Coombs, The Phases of Conversion: A New Chronology for the Rise of Slavery in Early Virginia, William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser. 68, no.3, July 2011.Royal African Company of Merchant Adventurers: Royal charter granted to, by Charles II.: 1663.: Copy.African Company, Royal: Charter granted to the Royal English Merchant Adventurers Company trading to Africa: 1663.: Copy.© British Library Board (Sloane MS 205, page 1).

Edward Hill III was at the center of the trade in captive Africans as one of only seven Virginians selected by the Royal African Trading Company to be its agents. The men who served were not just owners of large estates, but they also were knowledgeable of Virginia’s affairs, held political favor in the colony, and maintained close business and family ties with England. Hill was appointed in 1701 as the agent for the Upper James. His appointment came after the Trading Company had lost its monopoly, but the roll of agent was still a powerful and lucrative one. The agent earned a commission by arranging for the sale of all company captives, extended credit by granting Bills of Exchange to would-be buyers and collecting from creditors. In addition, the agent monitored all traffic by separate traders who paid tariffs to the Trading Company to support maintenance of the company’s African facilities. Hill was complimented by the company for diligently reporting on the arrivals of ships and the duties they paid. Charles L. Killinger, III, The Royal African Company Slave Trade to Virginia, 1689-1713, (Master’s Thesis William & Mary 1969). Hill portrait courtesy Historic Shirley; Tobacco label https://www.slaveryimages.org/

Most Africans brought to the colonies came from the West Coast of Africa from Senegal in the north to Angola in the south. The Royal African Company built several forts—termed “factories”—where captives purchased from African traders were held for shipment. Fort James on the Gambia River was the source of the Senegambians, the most numerous imports in the late 17th century. Robert “King” Carter, the wealthiest man in the colony and enslaver of more than 700 souls, spoke highly of “Gambians” because he thought them “more used to work” than other Africans and he was prepared to pay two pounds more per head for them than for “bites,” meaning captives from Bight of Biafra and Bight of Benin. Guinea map 1725 and James Island, Fort Gambia courtesy https://www.slaveryimages.org/

While Virginia planters may have had preferences for Africans from certain regions, their choice was dictated by supply. During the 1700s, a majority came from the Bight of Biafra and Bight of Benin. The International Slave trade data base presently lists 72 voyages known to have disembarked on the Upper James River during the 1700s. African origins are listed for 38 of those vessels. Of the 38, 20 carried “bites,” 10 carried “Gambians,” and 4 carried Angolans. Transport des negres dans les colonies courtesy www.slaveryimages.org.

Calabar and Bonny were the two Royal African Forts on the Niger River in the Bight of Biafra where “bites” were loaded onto vessels destined for the James River. Others came from Ouida in the Bight of Benin, whose king is pictured here. The “bites” were less valued by traders because the captives were predominantly women and children. Images (first) Bight of Biafra Slavery and Remembrance, (second) Public Appearance of the King of Benin, courtesy www.slaveryimages.org .

During the time period when Africans were being imported to Virginia in large numbers, John Carter married Elizabeth Hill, daughter of Edward Hill III, in 1723. He was Secretary of the Colony and eldest son of Robert ‘King” Carter. When Edward Hill III died three years later Elizabeth inherited Shirley, making their combined wealth even more substantial. The enslaved individuals on Carter plantations, however, were “entailed”—meaning tied to the land. As a result, Shirley’s enslaved community was one primarily created by the Hills, rather than the Carters. John Carter and Elizabeth Hill portraits courtesy Historic Shirley.

Like Edward Hill III, John Carter was involved in the trade in captive Africans. He acted as agent for two British traders, meeting the vessels on arrival, advertising the sale, and collecting the proceeds for which he received a commission. Surviving letters document the sale of captives from at least two vessels at Shirley in 1738 and 1739. One of those vessels carried Senegambians who sold well. The other carried Angolans who were in such dreadful condition a number died on arrival or shortly thereafter. Carter did not purchase captives from either vessel for his own account. However, Carter likely was purchasing slaves from other traders because he brought 12 children into court in April 1738 to have their ages determined for purposes of taxation. The group included one girl and eleven boys between the ages of two and ten (Sally, Dick, Tom, John, Sam, Oliver, Dawber, Frederick, Newman, Primus, Walker and Banger). The Slave Deck of the Albanez courtesy www.slaveryimages.org; Virginia Gazette 30 JUN 1738; Virginia Gazette 06 JUL 1739. Charles City Court Orders 1737- 1751, pp. 38-39.

A 2004 archeological investigation in the north yard at Shirley of an earthen cellar, later used as a fill pit, produced many artifacts dated between 1670 and 1720. The artifacts provide precious traces of Shirley’s earliest Africans. One collection of artifacts pictured on the left is a possible spiritual cache. This unusual collection of artifacts was found concentrated near the southeast corner of the pit at the floor level. The collection included a chunk of intentionally fractured crystalline quartz, a flake of European flint distinctly pointed at one end, the bones of a raptor, possibly a red-tailed hawk, and large pig canines. Spiritual caches reflected African religious beliefs that were a part of the Kongo culture of Central Africa. The contents provide a glimpse into beliefs about spirit power, transcendent connections, and the importance of protection in a fearful and uncertain world. The cowrie shell pictured on the right has been pierced on the back, indicating it was worn by its owner. Cowrie shells had several uses in African cultures and were brought to Virginia by captives either from Africa or from the Caribbean. The artifacts are on display in the Shirley kitchen. Possible spiritual cache and cowrie shell photos courtesy Charles City County Richard M. Bowman Center for Local History. View the Next Section >>

A Lineage Preserved in Names

During the 1600s Virginia planters had no customary practices regarding the naming of imported Africans. By the 1700s, however, it became customary to rename Africans with English names. Robert “King” Carter directed that each new arrival be given an English name and the name be repeated over and over until the captive responded to the name. While the act of renaming was designed to erase an African identity, it was used by the enslaved themselves to create a family lineage. English forenames passed on by enslaved women to their own children documented their parentage. While the surnames mothers gave to their children preserved a family lineage for generations to come. Several decades after the Civil War, Mary Patterson, who had been enslaved on a plantation adjoining Shirley, testified in a Civil War pension application stating that “[i]t was the custom that all the enslaved persons were called after their master, although they often called themselves after what they believed to be their true family names.” Music and Dance in Beaufort County, attributed to John Rose, Beaufort County, South Carolina, circa1785, watercolor on laid paper, 1935.301.3, image #Tl 995-001. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Gift of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller.

In addition to the three Africans imported by Edward Hill I, Edward Hill II claimed headrights for the importation of seven Africans in 1694 and three more in 1696. Two years later the Royal African Trading Company lost its monopoly on the African slave trade and independent British traders jumped into the trade, significantly increasing the number of vessels reaching Virginia. As noted above, the Africans they imported in large numbers were women and children. In 1696 Hill also claimed headrights for the importation of 98 English men and women. Of the 98 white servants only 17 were female. Living and working side by side, the English men and African women, formed unions which produced mixed race offspring. Because the status of the mother determined the status of the child, the children were born into hereditary enslavement. Sidney E. King painting from a postcard.

A striking pattern emerges when the 1696 list of immigrants is compared to the 1806 inventory of those enslaved on the Hill plantations inherited by Charles Carter, son of John Carter and Elizabeth Hill. Many of the enslaved were listed without their surnames, however, among the surnames that are listed there are five “matches” with the 1696 list. The logical conclusion is that these matches reflect an English indentured ancestor. The matches include Jo: Barber and John Barber (at Harden’s), Wm Rogers and Charles Rogers (at Shirley), Wm. Cooper and Betty Cooper (North Wales), John Green and Lucy Green (at South Wales), Tho. Bottomly and Harry Bottom (at Shirley). The sixth match is missing from the inventory because he was the condemned slave Jack Fells from North Wales (described in the next section) and the Henry Fells on the 1696 list. Another surname may date to earlier indentured servants. Tho. Moore was among the servants imported in 1660. Another Thomas Moore was imported in 1663, and two more Thomas Moores (possibly the same man claimed twice) were listed as headrights in 1711. The 1806 inventory includes a Tom Moore at Shirley and a John Moore at North Wales. Cultivating Tobacco, Virginia, 1798 courtesy www.slaveryimages.org.

Other surnames emerge from Charles Carter’s 1783 Personal Property Tax list—Hall, Gill, Scott, Bates, Parrish, Russell, Tin, Tucker, Burwell, and Griffin, many of them names shared by Charles City families who likely descended from indentured servants. Several of the surnames may have come from overseers. John Bates was Edward Hill III’s overseer at the time of his death and Thomas Hall was Charles Carter’s overseer listed in this tax list.

Forenames passed down among Shirley enslaved hint at other family histories. Three African names appear in the 1782 personal property tax list. Cuffee—meaning “born on a Friday,” and Mingo—meaning “Chief”—are common names for Senegambians and suggest ancestors imported from Gambia. Congo is a name of geographic origin appearing at Shirley as a Surname. Philander and Bibbianna are archaic English names of Greek origin that were passed down at Shirley until the Civil War. The most common male forename in the 1783 tax list, Tom, of which there are 8, suggests a connection to the “negro Tom” whose ownership by purchase Edward Hill II proved in court in 1695. The family lineages Shirley’s enslaved community sought to preserve by calling themselves by “what they believed to be their true family names” deserve—and await—scholarly examination. Charles City County Personal Property Tax list 1783, Library of Virginia Archives; Charles City County Court Orders 03 OCT 1695.

One additional confirmation that surnames utilized by Shirley’s enslaved community originated with white indentured servants is provided by this curious writing which appears at the back of a manuscript known as the Charles City Militia book. The book is a muster roll of troops enlisted at Charles City Courthouse 21 NOV 1776. The writing which is titled Roach explains that an English man named Roach (also spelled Roc in county records) indentured to Col. Edward Hill III cohabited with a free Black woman during the period of his servitude and had several children by her who took the name of their natural father. At the end of his servitude, he married an English woman named Royster, who likewise had been indentured to Col. Hill, and had children by her. What this manuscript fails to mention is that John Roach also appears to have had at least one child by a woman enslaved at Shirley. The evidence comes from Charles City Baptist Church records which show John Roc, who was enslaved at Shirley, enrolled as a member between 1791 and 1810, more than a century after the indentured John Roach labored there. Charles City Militia Book, Library of Virginia Archives; Charles City Baptist Church Records, typescript copy, Richard M. Bowman Center for Local History

The only surviving Shirley Runaway Slave Advertisement from the 18th century conveys an image of the enslaved population consistent with this history. Nancy Lymus was a light-skinned, Virginia-born house servant who first escaped in 1775 and then escaped a second time in 1780 after she had been recaptured and sold to a second enslaver. She was dressed consistent with the status of one employed in the household. She was capable of evading recapture for some time by hiding among Charles City’s free Black community and then in the larger free Black community of Hampton. She was wed to an enslaved “fiddler” from New Kent County whom she likely met when he played for dances at Shirley or at the home of her second enslaver. And, she aided an African-born slave in his escape. In short, Nancy was probably a second or third generation Virginian using a surname who was skilled at navigating the disparate worlds of the immigrant enslaved and the free. The 1783 tax list includes six Nancys, and the total would have been seven had Nancy Lymus been counted. Virginia Gazette 28 JUL 1775; Virginia Gazette (Dixon & Nicholson), Richmond, 18 NOV 1780.

Robin Clark Walker is a member of the Shirley enslaved descendant community whose DNA results and family surnames reflect Shirley’s enslaved community history. Robin’s African ethnicity shows the predominance of captives from the Nigeria—Congo region that was the Bight of Biafra. A smaller percentage of her African ancestry comes from the Benin and Togo region that was the Bight of Benin. While the significant percentage of English and Irish ancestry reflects those indentured servants who labored beside and bore children with her captive African foremothers.

The names in Robin’s family also suggest a—yet to be fully understood—family lineage. Robin’s great grandmother Lucy Moore was born in 1862 at the outset of the Civil war. Her father was George Moore and her mother was Julia Howard Moore, a daughter of Tom and Bessie Howard. Robin’s 2nd great grandfather’s forename, George, is uncommon in the Shirley community and may reflect descent from one of the few enslaved individuals named in Charles Carter’s will. Carter gave his wife a life interest in his “Postillion George.” The Moore surname may have originated with the Thomas Moore who arrived in 1660, the man of the same name who arrived in 1663, or the two Thomas Moores who supposedly arrived in 1711 or it may come from Charles Carter’s second wife who was Anne Butler Moore. Ancestry DNA results courtesy Robin Clark Walker. View the Next Section >>

A Long Memory for Insurrection

Communities enslaved for generations and tied by complex webs of kinship develop a community character and institutional memory. Historian Philip J. Schwarz has suggested that “long memory” may have connected some Virginia slave insurrections. Schwartz uses the example of individuals enslaved by Charles Carter at South Wales, his plantation on the Pamunkey River in Hanover County, where a spontaneous uprising took place in 1769 and the involvement of individuals enslaved by Carter at North Wales across the river in Caroline County in Gabriel’s planned insurrection in 1800. A spontaneous revolt took place around Christmas 1769 in Hanover. An informant to the Virginia Gazette reported that the enslaved had “long been treated with too much lenity and indulgence, were grown insolent and unruly.” A new overseer was brought in to regain control. When his young steward attempted to strike an enslaved man who had failed to do an assigned task, the enslaved man swung at him with an axe. Forty to 50 enslaved laborers fought white men armed with guns. The leader of the rebellion and some of his allies were killed on the spot. If the whites had not been armed with firearms, they would not have regained control. Philip J. Schwarz, Twice Condemned, Slave and the Criminal Laws of Virginia, 1705-1865 pg. 180; Virginia Gazette (R) 25 Jan. 1770; South Wales photo courtesy Library of Congress.

Thirty years later in 1800, an enslaved man named Gabriel began plotting a wide-scale insurrection, recruiting men in Richmond, Petersburg and neighboring counties. Gabriel made a decision to recruit men for his planned insurrection along the Hanover- Caroline border where he knew few if any enslaved individuals, perhaps suspecting the presence of a revolutionary tradition among Carter’s enslaved people. He quickly recruited Jack Gabriel and it was agreed Gabriel would be Captain of the Caroline men and bring them to the rendezvous. Should he be unable to travel “he would send his men by John Fells,” a boatman, “who was to be a Colonel upon that occasion.” When the plan was uncovered four of Carter’s men were arrested and charged with conspiracy- One-eyed Ben, Jack Fells, Jack Gabriel and John a Boatman. John was acquitted, but the other three were condemned to death. To limit the cost of reimbursing enslavers, the Virginia General Assembly quickly passed a law allowing condemned slaves to be sold to traders who would convey them to places from whence they could not return to Virginia. The three Carter men were among those transported in lieu of hanging, and Carter was paid $934 for the men who were transported to New Orleans.

Jack Fells may have inherited a long memory from an English forefather as Henry Fells was charged in 1693 along with William Cater, another indentured servant and Lewis, an enslaved man, with carrying away and eating a hog from Hill’s Old Town plantation. Douglas R. Edgerton, Gabriel’s Rebellion, The Virginia Slave Conspiracies of 1800 and 1802, pg.62, 96-98, 112, 151. Carter Claim courtesy of the Library of Virginia, Virginia Untold digital collection. Charles City County Court Orders 03 OCT 1693.

Spontaneous uprisings and planned insurrections were not confined to Charles Carter’s North Wales property. Shirley or Hardens saw its own uprising in 1792. “[S]everal negroes were discovered on a neck of land near the river, belonging to Col. Carter, stealing sheep.” An overseer armed himself and went in pursuit “entering a thicket of wood.” One of the enslaved men shot and killed the overseer. Neighbors sent for a “Negro hunter” from Chesterfield County and his dogs “who were famous for negro hunting.” The dogs found an encampment “filled with wheat and other plunder,” and captured several of the men, among them the man who had killed the overseer. The hunters then crossed the river, pursuing others and on the south side of the river, likely on Carter’s Old Town plantation. More than ten altogether were captured. The report of the uprising reveals the “alternative geographies” of enslaved people whose superior knowledge of the land, woods and waterways allowed them to create private places for meetings known as “hush harbors” or for butchering the enslavers’ livestock. General Advertiser, 24 Nov. 1792; Fugitive slave attacked by dogs courtesy www.slaveryimages.org.

Seventy years after the 1792 spontaneous armed insurrection, in June 1861, Shirley’s William Buck was charged with conspiring with Charles Lewis and William White, men enslaved by Richard Epps with conspiracy to make insurrection “by conversing together about the Northern Army & their expectations of being set free & having arms put in their hands & their readiness to rebel against their masters.” The offense was a felony carrying the death penalty. Hill Carter and John Selden, Justices of the Peace, found the evidence insufficient to establish a conspiracy, but sentenced each man to receive “thirty nine lashes upon the upper back well laid on.” The prosecution of William Buck and others for conspiracy to make insurrection, Charles City County Ended Causes Box 10, Library of Virginia Archives.

William Buck who was charged with insurrection could be the same man, Hill Carter’s cook, who ran away in July 1855. The $200 reward Carter offered for his apprehension was the largest reward ever offered for a self-liberating laborer. If it was the same man, most likely the only thing that saved him from sale was his importance to Carter as a cook. A 35-year-old William Buck, also described as a cook, left with McClellan’s Army in 1862 . Richmond Whig 17 JUL 1855. View the Next Section >>

Agricultural Reform and the Second Middle Passage

Robert Carter, son of Charles, was destined to inherit Shirley, but died before his father. Consequently, Shirley passed to Robert’s son Hill Carter, who was 10 at the time of his grandfather’s death in 1806. Robert had been a reluctant enslaver. He once wrote to his children, “[f]rom the earliest point in time when I could distinguish right from wrong, I conceived a great distaste for the slave trade and all its barbarous consequences.” Shirley was managed for a decade by uncles until Hill came of age and took over management in 1816. C.B.F. de St. Memin portrait of Robert Carter (first), Hill Carter photo (second) courtesy Historic Shirley.

When Hill Carter became Shirley’s manager many Tidewater planters were selling their farms and moving south because soils in the Tidewater had been depleted by tobacco and farms employing enslaved labor had become unprofitable. Other planters who remained in Virginia began selling enslaved workers from their farms to slave traders who conveyed them to the deep south. The rise of “King Cotton” created what historians call the “second middle passage,” during which approximately one million enslaved laborers were “stolen” from their parents, spouses, children and grandparents in the upper south and sold to labor on cotton plantations in the deep south. Slave Trader, Sold to Tennessee courtesy slaveryimages.org.

Shirley’s precarious condition was evident even before Charles Carter’s death. In 1802 Carter Berkeley, whom Carter had placed in charge of his North and South Wales Plantations, argued forcefully against Carter’s request to send lambs to Shirley fearing that it might incite depredations by the North & South Wales enslaved laborers who “are apt to conclude from this, that your negroes every where else fare better than themselves & whenever they have an opportunity, they help themselves.” Berkeley observed that Carter might sell all of his laborers in Charles City and Henrico, and invest the proceeds to earn a greater profit than he was experiencing by keeping them. Letter, 1802 of Carter Berkeley to Charles Carter of Shirley Plantation, 19 Oct 1802 courtesy Library of Virginia Unknown No Longer Digital Collection.

Upon taking the reins of his inheritance in 1816, young Hill Carter was determined to make reforms. He lobbied other planters to remain in the Tidewater, claiming “Virginia Negroes [constitute] a most desirable class,” and that “it only requires system and some little management to make them valuable as a class of laborers.” Slavery itself was not the problem in Carter’s view, it was the failure to employ good agricultural practices. Carter began his reforms, however, by selling 25 enslaved laborers in 1818 for $4,500 and 23 for the same amount in 1821, nearly half of the 106 he had inherited. While he sold them in family groups, that did not stop traders from separating husbands and wives and mothers and children. These sales likely accounted for the disappearance of certain surnames, like Cane (Cain) and Chern, from among Shirley’s enslaved families. Slaves awaiting sale, Richmond courtesy www.slaveryimages.org.

Carter believed that proper allotments of food, clothing and shelter were fundamental to maintaining a productive labor force, and so he used some of the proceeds from the sales to invest in clothing, blankets, shoes and improved medical care for those who remained. Food was distributed to family groups on a weekly basis and consisted of meat, corn meal and molasses. Rations provided only a portion of enslaved family diets. For the remainder Shirley’s enslaved families tended their own gardens and fruit trees, and raised chickens and occasionally hogs, as well. An archeological excavation of one of the cabins in the Great Quarter conducted in 1979-80 revealed that Shirley’s enslaved also consumed wild animals, most especially opossums which are nocturnal creatures that could be hunted at night. Meat List, July 12th, 1861, Shirley Plantation Papers, Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library, Univ. of Virginia; Great Quarter excavation photo courtesy Historic Shirley.

Carter invested heavily in the construction of new slave quarters, building five cabins in 1825, three in 1832, two in 1840, two in 1842, and eight between 1851 and 1854. Enslaved laborers whitewashed the quarters every year. The building pictured to the left was constructed in the 1850s and is the only one still standing, but located on land that is no longer part of Shirley. The photo in the middle shows seven cabins in the Great Quarter in the early 1900s, and the photo to the right shows Robin Clark Walker, a descendant of the Shirley enslaved community, with Lauren Carter, mother of the 12th generation of the Hill-Carter family to live at Shirley, standing at the Great Quarter site. First photo courtesy Historic Shirley; second photo Frank & Courtelle Hutchins, Houseboating on a Colonial Waterway (1910), pg.244; third photo courtesy Judy Ledbetter.

As Carter greatly reduced the labor force at Shirley, he also reduced the amount of acreage under cultivation. However, his reforms increased the amount and difficulty of labor required, and its complexity as well. Carter experimented with a five-field system finally settling on a four-field rotation. His laborers reclaimed swamp land and spread marl and manures. They also learned new skills and assumed responsibility for laboring independently. Huestis Cook of Upper Shirley courtesy Historic Shirley

Working free from constant oversight was one of the benefits enjoyed by some of Shirley’s enslaved men. Woodcutter Tom Howard, John Clark’s 3rd great grandfather, and a man named Young labored in the woods during daylight hours felling trees and hauling cut logs. That freedom was a precious commodity as it may have allowed the men time to hunt, meet secretly with enslaved workers from other farms or with free persons of color, or simply the opportunity to converse without fear of being overheard. Working independently also made it easier to run away. Cutting Timber in Virginia courtesy www.slaveryimages.org; John Clark photo courtesy John Clark.

Like enslaved laborers everywhere, Shirley’s laborers resisted enslavement by running way, as did Tom Moore in 1845. Four years later he was one of the casualties in a great cholera epidemic that swept Shirley, killing 31 individuals within three terrifying weeks during the summer of 1849. At the outset of the epidemic, Carter sent healthy laborers to Caroline County and he and his wife Mary moved out to live in the quarters nursing the sick and burying the dead. Tom may have been George Moore’s father, and, if so, was Robin Clark Walker’s 3rd great grandfather. Shirley Plantation Records, UVA. Richmond Whig, 07 FEB 1845; List of cholera dead, Shirley Plantation Papers, Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library, Univ. of Va.; photo of Robin Clark Walker courtesy Judy Ledbetter.

Some of Shirley’s Africans brought spiritual practices with them from Africa, others may have been Muslims or Christians before they were enslaved, and some may have become converts to Christianity within a short time after their arrival in Virginia. The Rector of Westover Parish from 1721 to 1757, Rev. Peter Fontaine, was committed to providing religious instruction to the enslaved, a commitment that distinguished him from most Episcopal priests of the time. Rev. Fontaine reported to Commissary Blair in 1724 that he took “all opportunities both public and private to exhort masters and mistresses to instruct their slaves in the principles of Christianity at home and to send them to church to be examined and instructed by me during the time of the catechetical exercises which I begin in April and continue every Lord’s Day to the later end of June.” Whether or not Shirley enslaved were converted by Rev. Fontaine, by the time of the Revolutionary War evangelical Baptist and Methodist preachers were seeking converts among the county’s enslaved population. On Dec. 1, 1776 the Virginia Gazette published a Charles City Petition Concerning Dissenters signed by 260 residents which among its grievances contained the statement: “We have seen meetings in the night with our slaves without our consent to receive the instructions of these teachers, which we apprehend could produce nothing but deeds of darkness, and which have already produced their proper fruits of disobedience and insolence to masters, and glorying in what they are taught to believe to be persecution for conscience’ sake.” Virginia Gazette (Purdie), 06 DEC 1776.

Charles City Baptist Church, organized the same year (1776), was led by Rev. James Bradley, a white minister. The church’s membership included whites and free blacks, but most of the members were enslaved. Records of the church beginning when it was reconstituted 1791 list almost 50 members from Shirley Plantation who joined before 1810. A church meeting house was constructed near the intersection of Old Union and Barnetts Roads, and Shirley’s church members apparently were allowed to travel the 10½ miles to church on Sundays. Image courtesy www.slaveryimages.org .

In an advertisement for six runaways in April 1829 (Joe Lyons, John Sampson, Wm. Sampson, Billy Tanner, Sam & Charles Smith) Hill Carter described the clothing of some as “old blue jackets, coats and pantaloons, white cotton or linen shirts, and other Sunday clothes, as they call them.” While most of the men were quickly apprehended, William Sampson still had not been apprehended nine months later when Carter offered a $100 reward for his return. Richmond Enquirer 28 JAN 1830.

The reforms that Carter instituted—and his enslaved laborers carried out—succeeded in making Shirley profitable again. Carter was widely regarded as one of the best farmers in the state. For their labor, Shirley’s captive workforce earned improved living conditions, but more importantly they saved themselves from the second middle passage. The enslaved community that Carter had reduced to 58 had grown to 139, more than doubling by the dawn of the Civil War. The wealth Shirley’s enslaved laborers had created in their children and grandchildren was not sold away from them. Staunton Spectator and General Advertiser, 14 SEP 1843. View the Next Section >> View the Next Section >>

Claiming Freedom Amidst Civil War

After the Union took control of the lower peninsula and Union gun boats began forays into the James River, Siah Hulett, a 23-year-old carpenter, was the first to claim his freedom and the first known to have broken the chain of nine generations of servitude. He made his escape to freedom in dramatic fashion rowing out to the US Navy’s first ironclad the USS Monitor on May 18, 1862. Siah Hulett Carter photo detail courtesy Shirley Plantation.

According to a William F. Keeler, Paymaster for the Monitor , “the poor trembling contraband rowed a boat from the plantation’s river bank out to the anchored USS Monitor by cover of night.” Thinking the approaching boat could be a Confederate boarding party, Monitor crew members grabbed their small arms and lined the deck. One of them even shot a warning at the approaching vessel. “[He] cried, “O’ Lor’ Massa, oh don’t shoot, I’se a black man Massa, I’se a black man.” He told the crew that “his master was a colonel in the rebel army… & told [all his slaves] that if any of them went on board of the Yankee ships, the Yankees would carry them out to sea, tie a piece of iron about their necks & throw them overboard”. Siah Hulett was enlisted in the U.S. Navy as Siah Carter, a name given to him by the U.S. Navy. Wiliam F. Keeler, Aboard the USS Monitor:1862, Naval Letters Series, Vol.1, U.S. Naval Institute (1964), pg.132; Deck of the USS Monitor U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photos.

Carter survived the sinking of the Monitor and went on to serve aboard the USS Brandywine, Wabash, Florida and Commodore Barney . It was aboard the Commodore Barney , pictured here in the James River, that he suffered frostbite on his toes while searching for torpedoes in the Appomattox River. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

Shortly after his discharge from service Siah married Eliza Tarrow (Tarrer) another member of the Shirley community. The marriage was performed by Rev. Zachariah Evans, first pastor of the newly built First Baptist Church in Hampton. A number of Shirley family and acquaintances were in attendance, and later gave affidavits in Eliza’s Widow’s Pension application. Eliza is shown in this Freedmen’s Bureau Record as a dependent on a government farm near Fort Monroe. The couple lived in Bermuda Hundred, Chesterfield County, for five years while Siah worked as a carpenter before moving to Philadelphia, PA in 1870 and his new job as a longshoreman. U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau Records, 1865-1878, Ancestry

Throughout their married life, Siah used the surname Carter while his wife used the surname Hulett. When he could no longer work Siah applied for, and received a pension. He died April 12, 1892 at age 52. Eliza buried him as Siah Hulett. Then to receive a Widow’s Pension she had to prove that Siah Carter and Siah Hulett were the same man. A Bureau of Pensions examiner travelled to Charles City and interviewed a member of the Carter family who said that Siah was the first to “desert” them and one of their “most valuable slaves.” He was buried in Olive Cemetery in west Philadelphia. The cemetery was condemned and disinterred in 1923. The burials were reinterred at historic Eden Cemetery in Collingdale, PA. One hundred twenty-nine years after his passing, in 2021, Siah Hulett Carter received a government issued headstone through the efforts of Camp #124, New York Dept. Sons of Union Veterans and its Vice-Commander Stump. Siah’s second great nephew Daniel C. Jones, Jr. and third great nephew Christian A. Jones are pictured next to the headstone. Photos courtesy Daniel C. Jones, Jr.

Siah was not the only member of the Shirley community to claim freedom aboard a US. Navy vessel. Acting on instructions to “threaten Richmond” eight Union gunboats—the USS Sangamon, Lehigh, Mahaska, Morse, Commodore Barney, Commodore Jones, Shokokon, and Seymour —ventured up the James River in mid-July 1863. On the 14th they captured Fort Powhatan across the James River from Charles City. On July 18th the Navy recorded the enlistment “in the James River and at Harrison’s Landing” of 20 men, including at least 10 from Shirley Plantation. One of the sailors would later refer to the men as “the 18 of July 18, 1863.” The men from Shirley whose Naval service has been documented are William Bates, Joseph Burrill, Edward Christian, Daniel Christian, John Christian, Martin Hewlett, Thomas J. Howard, John Morris, Phillip Pride, and Henry Washington. Crew of the USS LeHigh in the James River (showing at least two Black men in uniform), image courtesy National Archives U.S. Naval History & Heritage Command photos.

Nine months later in May 1864, when Brig. Gen. Benjamin Butler moved his forces to Bermuda Hundred, several of the men returned to Shirley to help their wives and children claim the freedom that had been granted to them by the Emancipation Proclamation. A member of the Carter family penned a letter dated May 14th in which she wrote “[w]e are in great straits every day. Betsy Buck’s family and the girls who waited in the dining room, Phyllis daughter are missing today. We hear their husbands came ashore and took them off.” Julia Moore attested in Phoebe Ann Harris’s Widow’s Pension application that she knew William Harris had served on a gunboat because “I see him while he was in service when they all come in their uniforms.” Fanny Nelson Carter to Sister Lucy, May 8, 1864, reprinted in Charles City County Historical Society Newsletter, March 1995; William Harris, widow’s pension application 17389; Ships at City Point courtesy Library of Congress.

With Gen. Butler in residence across the river Shirley came under the watchful eyes of Union soldiers and experienced frequent visits from landing parties. As Hill Carter’s wife Mary lay dying of pneumonia in May 1864, her youngest son Beverly Randolph Carter, a sharpshooter on leave from the 12th Virginia Infantry, came secretly to Shirley to visit his mother. While he was asleep in the house Union officers came to search out rumors of a Confederate spy. Beverly’s sister-in-law, Louise Humphreys Carter hid his boots and pistols in her bed while Beverley climbed up to the attic and hid in the shadow of one of the massive chimneys where he escaped detection. Photo courtesy Historic Shirley.

After the officers left Beverley quickly departed. On his departure, Lydia Buck Washington or “Old Liddy” as she was called by the Carter family, 6th great grandmother of Syncere Smith (pictured here), said to Beverly, “Mass Beverley you ought to love Miss Lou and do for her as long as you live, for she has saved your life from these Yankees.” Beverley commanded Lydia to “get right out or he would blow her brains out for she was at the bottom of the whole thing.” The next day a company of Union soldiers marched to the house and presented an order from Gen. Butler to arrest Hill Carter and everyone else, male and female, white and Black to be taken to headquarters to answer for harboring a rebel spy. Louise Humphreys Carter insisted that the white women would have to be taken in chains and told them the truth about Beverley’s visit, insisting that no information had been exchanged on any matter related to the war. The officers relented, but took Carter and others, including Lydia, to Bermuda Hundred for three days while they all were examined, and all reportedly gave the same testimony. According to Louise Humphreys Carter, Butler had put out the word that he would pay $20 in gold and more for information and Lydia thought she was going to get a “pile of money” for her courageous act of defiance. Louise Humphries Carter memoir dated June 20, 1905, courtesy Library of Virginia Digital Collection Unknown No Longer; Photo courtesy Syncere Smith.

Louise Humphries Carter recalled other events of May 1864. “Those were most trying days the soldiers all about and sitting in the servants houses, who could with difficulty be made to stay at their work and all with buttons pinned on their breasts with Butler’s picture pinned on them.” It is unclear from her recollection whether it was the soldiers or the enslaved who were wearing the buttons, and which buttons they were wearing. The well-known medal of the James River which Butler issued to U.S. Colored Troops depicted U.S.C.T. and not the Brig. General himself, and it was issued to honor the bravery of U.S.C.T. in the Battle of New Market Heights four months later in September 1864. If Shirley’s enslaved were wearing any sort of Union or Butler buttons that would have been an open act of defiance. Gen. Benjamin Butler was despised by the Carter women for many reasons, but especially because they felt insulted when he sent U.S. Colored Troops to guard the house. Louise Humphries Carter memoir dated June 20, 1905 courtesy Library of Virginia Digital Collection Unknown No Longer. Benjamin Butler Medal courtesy Division of Political and Military History, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. View the Next Section >>

The look of freedom—Reconstruction and Reformation

In the May 8th, 1864 letter described in the last section, the writer further described the scene when an elderly dining room servant was taken away from Shirley. A small boat from one of ships in the river had landed at Shirley with a Union officer who said he had been ordered to take away any male servants who might know the river. Carter said that all had run away to the woods, but reluctantly called up 77-year-old Anthony Pride. The letter described him as “in the last stages of consumption though he is a most excellent dining room servant and a great loss to us.” According to the letter writer “Nat begged hard” not to go, and the officer “gave his word of honor” that he would be returned though he was not. Fanny Nelson Carter to Sister Lucy, May 8, 1864, reprinted in Charles City County Historical Society Newsletter, March 1995; Ships at City Point courtesy Library of Congress.

During the course of the war 70,000 enslaved men, women and children claimed freedom behind the Union lines. At the war’s end conditions in the Freedmen’s Bureau camps of the lower peninsula were horrific. To depopulate the peninsula the Bureau began returning freedmen to the counties where they previously had been enslaved. Anthony, his wife Sarah, daughter-in-law Betsy and grandson Nat, age 8 were shipped to Bermuda Hundred across the river from Shirley as shown in the first Freedmen’s Bureau record. In the second record a Bureau agent sought to get rations supplied to them from time to time because they were very aged and their son had consumption. The final record indicates their son had died and Mr. Carter would call for provisions at the storehouse when notified, suggesting that Anthony and Sarah had come back to Shirley where they would live out their final days. U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau Records, 1865-1878, Ancestry

Tidewater farmers faced an enormous labor shortage after the war and welcomed back freedmen who returned. Hill Carter was instrumental in obtaining agreement among local farmers to fix wages and expectations for farm laborers. Farmers agreed to pay the fixed wages and to refrain from employing any laborer who had been discharged elsewhere for misconduct. The $10.00 per month wage for a first-class field hand was higher than the state average for farm wages. Farmers also agreed on the amount of food to be supplied and the deductions that would be made from wages for fuel (wood) supplied during the winter months. Virginia Pilot, 11 JAN 1866.

The Freedmen’s Bureau transportation record for Stephen Whirley and family indicates he had secured employment with Hill Carter in advance of transport to Carter’s landing. The notation is curious because Whirley had not been enslaved at Shirley and was not among those first hired to work. Eventually Whirley was hired to work at Shirley. His son, pictured here, also named Stephen, worked at Shirley and served as a deacon of New Vine Baptist Church. U.S., Freedmen’s Bureau Records, 1865-1878, Ancestry; photo courtesy New Vine Baptist Church.

These lists for January and March 1866 show the first laborers who were paid wages at Shirley, the sum of wages they were paid and the provisions they were supplied. All of the employees were Shirley freedmen with the exception of Napoleon Bates whose wife and children had been enslaved at Shirley. All of the laborers signed with an “X” to document their receipt of wages and rations. Looking at the list one might rightly ask, “What did freedom bring?” While not evident at first sight, freedom brought important changes both for the former enslavers and the former enslaved. Account of Wages Paid to Hirelings, Shirley Plantation Papers, Albert & Shirley Small Special Collection Library, Univ. of Va.

Robert Randolph Carter, Hill Carter’s second son pictured left, took over management of Shirley in 1866. During the war he had served as Captain of the Confederate blockade runner Coquette and as a member of the Confederate Secret Service. He applied for amnesty and was granted a pardon by President Andrew Johnson. Among the laborers employed at Shirley were five Union seamen (Ned Christian, John Christian, William Harris, Charles Lewis and Andrew Sampson), four of whom had served on vessels enforcing the blockade and chasing the runners. That these former enemy combatants managed to work side by side after the war is a testament both to necessity and reconciliation. Robert Carter shared the risks attendant to farm labor and died as a result of injuries sustained in a farming accident in 1888. His widowed daughter Alice Bransford took over management of Shirley which she ran until 1917 when she wrote in the Farm Journal that her cousin Charles Hill Carter, Sr. would be taking over the farm “I am down and out and can no longer do it…have had no cook and no housemaid for a year.” Robert Randolph Carter and Alice Bransford photos courtesy Historic Shirley.

Five years after the end of Reconstruction in 1876 Robert Carter calculated all of Shirley’s income and expenditures over the 10 years after the end of the Civil War, showing a net loss of $10,000. Farming itself was profitable in all but one year. It was the household expenses that produced the loss. The only reforms that could save Shirley a second time were increased mechanization and a reduced standard of living for the Hill-Carter family. Results of Farming at Shirley exclusive of other resource, Shirley Plantation Papers, Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library, Univ. of Va.

The most significant hallmark of freedom experienced by families who returned to live and work at Shirley was the right to vote which was extended to Black men by the 15th Amendment. The roll of Colored Voters in District No. 1 (Harrison) includes many Shirley freedmen including seven men of the Washington family (Henry, Joseph, James, John, James, and George). All of these men voted in their first election 22 OCT 1867 in favor of a Constitutional Convention and for Lemuel E. Babcock as a Delegate. District No. 1 Colored Voters, Library of Virginia Digital Collection Virginia Untold.

When they registered to vote or gave information to census takers a few Shirley families provided surnames different from the ones Hill Carter used to identify them in countless Shirley Plantation records. The family of Jim and Lydia Buck in Shirley records became James and Lydia Washington in public documents. Harry and Nancy Tin became Henry and Nancy Washington (shown here). Charles and Iris Buck became Charles and Iris Morris and Daniel and Charity Sampson became Daniel and Charity Christian. This is yet one more example of unexplored history in the names. One possible explanation is that Carter favored mothers’ surnames over fathers. Another possibility is that Carter simply did not know the surnames his enslaved families believed to be their true names. 1870 U.S. Census listing for Henry Washington in Charles City County, VA, Ancestry.

Freedom changed the role of women. Under Hill Carter’s agricultural reforms much of the farm labor, including many of the tedious tasks, were performed by women and children. When free to choose Shirley women left the fields—except for harvest times—and either became homemakers or worked as domestics. While no women worked as farm laborers at Shirley during Reconstruction, later in the 19th century four women were employed regularly, but they were the only ones. One of those women was Nancy Bates Carter, wife of William Claiborne Carter. Her mother, Phyllis Grassly Bates had worked in the house and her brothers William and Stephen had been dining room waiters, and so her choice reflected a reversal of family tradition. This photo shows women stacking wheat at Curles Neck, not far from Shirley. Huestis Cook photo courtesy Cook Collection, The Valentine.

The role of children changed as well. While children continued to be born at and live in the quarters, now they were attending county schools. Pictured here is a consent to the issuance of a marriage license written with precise penmanship and wording by Lucy Anne Moore who had been born during the war. In the consent Lucy names her parents and states that she is a resident of Shirley where she was born. Both her penmanship and her grammar are better than that exhibited in many of the consents written at the time. Charles City Marriage Licenses and Consents (1888) Charles City County Richard M. Bowman Center for Local History Archives; Heustis Cook photo taken at Upper Shirley courtesy Historic Shirley.

Property ownership was another hallmark of freedom. Major Drewry, pictured left, bought Westover in 1862. He had no children by either of his wives, and that may be the reason that he and his second wife were willing to sell more than 50 small parcels of land to buyers, most of whom were freedmen. The parcels were carved out of properties known as Mill Quarter, Turkey Trot and Little Berkeley. Land ownership was something freedmen might not easily acquire if they moved north, and so it may have been the Drewrys who accounted for the significant number of formerly enslaved who remained in Charles City after the end of Reconstruction to work the fields of Shirley, Berkeley and Westover. Shirley families who purchased land included Julia Moore (20 acres 1893), James Washington (10 acres 1894), John Christian (10 acres 1895), Charity Christian (6 acres 1895), Jerry Jones & Lucy Christian (5 acres 1896), Mary Washington (12 acres 1897), Pompey Cox (6 acres 1898), Phoebe A. Harris (15 acres 1905), Richard Crump (5 acres 1899), Sam & Stephen Whirley (2¼ acres 1899 and 6 acres 1901). Their community came to be known as Kimages. By 1900 one-third of the property in Charles City was owned by persons of color. Pictured first “Major Drewry and Friends at Westover”. Pictured second, “Man Smoking in Doorway” photos courtesy Cook Collection, The Valentine.

Richard Crump was one of the freedmen who bought land from Maj. Drewry. He was born into slavery on Weyanoke Plantation, but married Lizzie Washington, a granddaughter of James and Lydia (Buck) Washington. In doing so, Richard joined the ranks of men like Charles Lewis and William Harris before him who seem to have been attracted to work at Shirley by the women they married. Richard and Lizzie lived in the quarters at Shirley where they raised 11 children, earning at the end of the century the same $10 a month that had been paid to laborers at the beginning of Reconstruction. They also received rations consisting of a peck and half of meal and blackstrap molasses. Their eldest child Henry, pictured here, was born 8 NOV 1889, and dropped out of school after the 3rd grade to work with his parents. Henry left the county to serve in WWI and moved to New Jersey after the war. In 1934 he returned to the county where he worked at Shirley and other places and served as a Deacon of New Vine Baptist until he died at the age of 103. Henry may have inherited his longevity from an enslaved man, called “Old Buck” who was born in 1749 and died in 1849 at the age of 100. Photo courtesy Byron Adkins.

In a 1992 interview, Henry Crump recalled an incident that occurred when he was three or four. One of the jobs his father performed was to unload 167-pound bags of burnt oyster shell from a lighter onto a cart on the Shirley wharf. One time the mule pulling the cart accidentally stepped off the wharf and fell pulling the cart into the James River. His father jumped in, trying to cut the traces to save the mule, but the mule pulled him under. Richard might have drowned if a fellow laborer hadn’t grabbed him by the collar and pulled him out. Interview with Henry Crump, Shirley Plantation; photo courtesy Historic Shirley.

Pompey Cox, Sr. was another freedman who bought land from Maj. Drewry and whose first wife was a woman from Shirley. He was born in Powhatan County, but began employment at Shirley in the 1880s. Mr. Cox provided an affidavit in support of the Widow’s application of Phoebe Ann Harris, describing how he and other men including William Harris worked in the fields at Shirley and neighboring farms. One local resident remembers Pompey’s son as the county’s first “engineer” because of his extraordinary ability to read the terrain of a field and to determine where ditches should be dug to ensure proper irrigation and drainage. Pompey Jr. likely learned this skill from his father. Pompey Sr. is pictured with his great granddaughter Victoria Cox Washington who was elected Charles City Circuit Court Clerk in 2015. Photos courtesy Victoria Cox-Washington.

Many of Shirley’s formerly enslaved families never returned to Charles City, finding new homes in Norfolk and Hampton, or migrating north to Philadelphia and New York. One of the most remarkably successful migrants was Stephen Bates, a dining room waiter, who left Shirley with McClellan’s Army in the summer of 1862, as documented by this Auditor’s Report. Stephen was a son of Phyllis Bates, who worked in the house, and Napoleon Bates, a carpenter enslaved on a neighboring farm. His older brother William was also a dining room waiter, who later enlisted in the U.S. Navy with “the 18” in July 1863. Stephen Bates photo Boston Herald 27 DEC 1905; Shirley dining room courtesy Historic Shirley; Record of Slaves escaped to the enemy, Library of Virginia digital collection Virginia Untold.

After the war Bates obtained employment as a coachman for Vermont Congressman Frederick Enoch Woodbridge. When Woodbridge lost re-election, Bates followed him to Vergennes, Vermont, a town with 13 Black residents. Bates continued his association with the Woodbridge family and trained thoroughbred horses for them. Congressman Woodbridge photo courtesy Library of Congress.

Five years after the end of Reconstruction, In 1875 Bates was appointed Chief Constable, a position he held until 1879 when he was elected Sheriff of Vergennes by its overwhelmingly white population. Bates was re-elected (or appointed Chief of Police) almost every year thereafter until his death in 1907. He was described in contemporaneous accounts as “almost entirely a self-taught man, who in the discharge of the duties of his office was cool and self-restrained, rarely if ever acting hastily.” The State of Vermont erected an historical marker in 2021, recognizing Bates as the first Black to serve as Sheriff and as Chief of Police in the State of Vermont. Bates’ great grandsons Larry and Nick Schuyler are pictured here at the dedication of a Vermont Historical marker in Vergennes town center. The ceremony can be viewed here . Photos courtesy Jane Williamson.

Bates’ son Frederick and daughter Rose moved to Worchester, Massachusetts, where a sizable Black community had been formed by Blacks moving out of the South. Photos of Stephen Bates’ grandchildren taken by photographer William Bullard around the turn of the century reveal the substantial prosperity enjoyed by these members of freedom’s second generation. Pictured first, Raymond Schyuler and his children, Credit: Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts, USA© Worcester Art, Museum /Bridgeman Images. Pictured second Rose Bates, Credit: Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts, USA© Worcester Art Museum/Bridgeman Images.

Richmond photographer Huestis Cook captured an unnamed Shirley gardener near the turn of the century. The unsmiling photo was published in Shadows in Silver in 1954 with a caption that read, “When the photographer chanced upon this young gardener at Shirley, he was in his state of ‘seekin’ religion.’ He had pledged to live a sober and serious life and, as he explained to the cameraman, this meant that he was not permitted to smile or even look pleasant, He allowed that if he were to smile, he would be ‘turned back’ and would have to start his ‘seekin’ all over again.” Mrs. James Harrison Oliver of Shirley is credited in the Acknowledgments and undoubtedly was the source of the caption for the staged photograph. While the published photo and its caption are somewhat satirical, the handsome unnamed Shirley gardener pictured in both photographs speaks beyond the prejudices of the times and tells us two things. Shirley’s enslaved families bequeathed a heritage of devout Christian faith to their children, many of whom filled the pews at New Vine Baptist Church. They also taught them to “put on a face” as needed to get by. Heustis Cook photos courtesy Cook Collection, The Valentine; New Vine photo courtesy New Vine Baptist Church. View the Next Section >>

The Lives and Legacy of Ned and Sarah Christian

This priceless family Bible is a living testimonial to the resiliency of the hands that first received it and managed to preserve it for future generations; hands that belonged to a woman who could neither read nor write. Although it has been separated from its cover and lost the first few pages of text, the fact that it survives at all is remarkable. The Bible, which belonged to Sarah Christian, documents the lives and legacy of Sarah and her husband Ned. If—as it appears—the first entries were made around the time their first child was born in 1852—the Bible has escaped to freedom on a Union gunboat, resided on three different Freedmen’s Bureau farms, returned by government transport to Shirley, resided in the quarters for several decades before moving to the Kimages neighborhood and then being passed on to daughter Lucy. Writing on the Bible jacket summarizes this eventful journey with the simple words “Sarah Christian Shirley turning to Lucy Jones.” Photos courtesy Charles City County Richard M. Bowman Center for Local History.

Sarah Christian was born on May 8, 1828. Her family relationships illustrate the complex and, thus far, poorly understood naming practices employed by the Shirley community. Her mother was Molly (Mary) Ann Tin, but Sarah’s birth name was Washington. Molly Ann was the mother of brothers Siah Hulett Carter and Martin Hewlett. In Civil War Pension affidavits Sarah described herself as sister of both Siah and Martin, rather than as a half-sister. She also described herself as a first cousin to Phoebe Ann Harris, daughter of James and Lydia Washington, suggesting strongly that Sarah’s father was a Washington. Sarah also was a sister to a man listed in Shirley records as Harry Tin, but listed in post-war public records as Henry Washington. Henry and his wife Nancy Christian named their youngest daughter Virginia Dare, the name of the first English child born in the New World. Virginia Dare was born in 1598 at the Lost Colony of Roanoke, a fact one might not expect individuals enslaved in Virginia to know. More likely, the name came from the schooner Virginia Dare , built in Richmond to carry flour to England. On her maiden voyage Virginia Dare spent a week anchored at Bermuda Hundred across the river from Shirley in 1860. Yet another history in the names waiting to be better understood. Photo courtesy Charles City County Richard M. Bowman Center for Local History; John Selden Journal of John Seldon 1858-64, Dec. 1860.

Family oral history tells that Sarah’s husband Ned (Edward) Christian, whose birth on January 10, 1828 is recorded in the Bible, arrived on a boat and left on a boat. Both events appear to be confirmed by documentary evidence. Hill Carter purchased Edward and another enslaved man named Joe in 1849 from J. Stamper who was a trustee under of a deed of trust made by Dr. John F. Christian of New Kent to secure certain debtors. The note showing payment of $1,300 for the two men is dated 28 DEC 1849. Hill Carter was purchasing slaves at this time, no doubt, to replace his heavy losses the summer before in the cholera epidemic. Ned may have arrived at Shirley a month before payment was made. In her Civil War Widow’s Pension affidavit Sarah stated that she and Ned were married at Shirley by a preacher named Williams on 26 NOV 1849 (a month before payment for Ned was made). In an earlier Pension affidavit, however, Edward stated the couple were married JUN 1850 at Shirley. The date supplied by Edward seems more realistic (6 months after his arrival), and the date of marriage is not recorded in the family Bible, which suggests the Bible was given to Sarah after she was married. Perhaps Sarah remembered the date of his arrival as the date of their marriage. With an enslaved community as inter-related as Shirley’s the arrival of new, and unrelated, eligible bachelors likely excited the imagination of more than one enslaved woman at Shirley. 28 DEC 1849 slave purchase receipt, Shirley Plantation Papers, Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library, Univ. of Va.

Ned’s departure from Shirley as one of the “18 of July, 1863” is documented in numerous records. It is difficult to imagine how painful the decision to leave must have been, as his third child Lillian had just been born eight days earlier on July 10th. Lillian was the second great grandmother of Tracey Gunthorpe. Ned was 38 years old when he enlisted in the U.S. Navy and stood 5 foot 8 inches tall. He served as a 1st Class Boy on the USS Mahaska, Wabash and Ohio. The USS Wabash was the flagship of the Atlantic blockading squadron. The Mahaska was also involved in blockading off Charleston, South Carolina. It was off the coast of South Carolina that Ned suddenly experienced the loss of sight in one of his eyes unrelated to any injury. USS Mahaska image courtesy the Library of Congress; photo courtesy Tracey Gunthorpe.

Sarah was a member of the household staff, one so trusted she was at the bedside of Mary, Hill Carter’s wife, when she died May 10, 1864. It seems likely Sarah received her Bible from Mary, pictured here, who was a devout Christian, known by her family to give “testaments” to Shirley’s enslaved families and also reported to have been caught teaching them to read, which was against the law.

When the Carter family awakened on the morning of July 4th, 1862, to see scores of Union soldiers wounded in the Battle of Malvern Hill lying about the lawn, Mary and the other women of the house went out to nurse them providing water, bread and soup. Her compassionate action likely saved Shirley from destruction because Gen. McClellan issued an order guaranteeing protection for the house and Carter family (pictured right). No doubt Sarah Christian was nursing soldiers, as well, but she paid a high price for her compassionate care. Ned and Sarah’s son Jacob contracted Camp Fever from the soldiers, suffering for seven months with a fever before he died March 18, 1863 his “brain much effected.” Photos courtesy Historic Shirley.

Family oral tradition also tells that Sarah was a cook laboring in the Shirley kitchen, pictured here, to prepare the elaborate meals served at Shirley. In 1833, Henry Barnard, a passing visitor from Connecticut, wrote about the elaborate meals and service provided to guests by Shirley’s enslaved waiters. Breakfast included Virginia ham and hot muffins and corncakes served every two minutes. Dinner began with soup and included mutton, ham, beef, turkey, duck, eggs with greens, potatoes, beets and hominy. Three dessert courses included plum pudding and tarts followed by ice cream, West India preserves, and brandied peaches, followed by figs, raisins and almonds. The alcohol courses began with Champagne followed by Madera, Port and a sweet wine for the ladies and cigars for the men. Shirley kitchen photos courtesy Historic Shirley.

All the table linens were changed between the dinner and dessert courses. Plumbing installed in the front parlor allowed precious Canton China plates to be washed between courses. The enslaved cooks and waiters who were responsible for the magic and extravagant production of a Shirley meal including countless entrees, washed and starched linens, polished and properly placed silver, freshly washed China, multiple wines, Chrystal glasses and the best cigars, were so highly-skilled they might have run a restaurant in a major city or worked in the White House. Indeed, Shirley staff had experience serving Presidents like Millard Fillmore who dined at Shirley in 1851 and Vice-President John Tyler who spent the night at Shirley on his way to Washington to assume the presidency following the death of Pres. William Henry Harrison. Just before the war Lord Napier, the British Minister Plenipotentiary to the U.S. dined at Shirley in 1860. Faucet and China photos courtesy Historic Shirley; Huestis Cook, Bringing in Dinner at Upper Shirley Plantation courtesy Cook Collection, the Valentine.

On June 10, 1864, Sarah and her four children left Shirley. Over the course of the next year, four Freedmen’s Bureau records list Sarah and their four children as recipients of rations at Newtown, a farm in Newport News. One lists the family at Howell’s Farm, also in Newport News, and one lists the family at Sugar Hill, a farm in the vicinity of Hampton. The listing for Sugar Hill contains a notation CCC 6/19 confirmed, and lists two adults with four children, suggesting that transportation for the family back to Charles City County had been confirmed in June of 1865. U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau Records, 1865-1878, Ancestry.

Ned and Sarah moved back into the quarters at Shirley and returned to work as paid laborers. In 1874 Ned suffered a broken leg when a cart turned over on him. It was a somewhat disabling injury, but the 1880 census still lists him as a farm laborer and Sarah as a homemaker. Heustis Cook, Farm Laborers at Upper Shirley courtesy Historic Shirley.

Lucy Christian, Ned and Sarah’s daughter, became the second Bible owner. Lucy married Jeremiah (Jerry) Jones, the free-born son of Rev. John E. Jones, founding pastor of St. Johns Baptist Church. The couple bought a 5-acre tract of land which they farmed. The two-story house they built was home to nine children. Before marriage Lucy had lived in Philadelphia for a while and worked as a cook in a commercial establishment. After marriage she worked at Shirley, at least she did so after their last child Daniel C. Jones was born. Lucy’s grandson remembers that the front parlor of the Jones house had a pump organ and velvet curtains and that boxwoods lined the front entrance walk that reminded him of Shirley. Photo Of Lucy and Jeremiah Jones courtesy Tanya Darden-Nelson; photo of Jones house and barn courtesy Charles City County Richard M. Bowman Center for Local History.

Lucy and Jerry’s daughter Sarah established and managed the P and J Bros. Store located on Route 5 between Kimages Road and Route 106. According to family oral tradition Sarah was the first woman to own a business on Route 5 in the county. Sarah is pictured in front of the store with some of her children. Her husband, William Albert Percy is pictured to the right. Photos courtesy Charles City County Richard M. Bowman Center for Local History.

Sarah and Ned’s grandson Daniel Cornell Jones was the third Bible owner. He entered 1st grade in 1916 in the one-room Kimages School built in 1876. The teacher taught 41 students in grades 1 to 6. Daniel was a good student who went on to graduate from the Ruthville Training School, the Virginia State High School, and Virginia State College receiving a B.S in Chemistry with Honors in 1933. End of Term Report, Charles City County School records, Richard M. Bowman Center for Local History; Daniel C. Jones diploma and graduation photo courtesy Daniel C. Jones, Jr.

Needing to earn money to pursue further education, Jones returned to Charles City and taught Chemistry at the newly constructed Ruthville High School, where he also taught the boys to play football. Daniel C. Jones Commonwealth of Virginia State Teachers Certificate courtesy Daniel C. Jones, Jr. Ruthville photo courtesy Charles City County Richard M. Bowman Center for Local History.

When he had sufficient savings, Jones entered Meharry Medical School in Nashville Tennessee where he received his M.D. with Honors in 1940. 1940 Meharry Medical College graduating class and Dr. Daniel C. Jones photo courtesy Daniel C. Jones, Jr.

In 1941 Dr. Jones became the first Black doctor to serve Farmville, VA. His office was in his home at 202 South Main Street. In the basement which had a separate entrance under the stairs he had a small hospital laboratory and surgery. He was a member of the Rappahannock Medical Society pictured here at Richmond Community Hospital with Dr. Charles Drew in the early 1940s. (Dr. Jones is standing third from the left in the next to last row.) Daniel C. Jones, Jr. , the fourth Bible owner, was born during the years Dr. Jones practiced in Farmville. At the end of WWII, the family moved to Ardmore, PA. where Dr. Jones practiced for another 45 years and furthered his education at Thomas Jefferson Medical School, Hahnemann School of Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and John Hopkins University. Following his studies, he was elected a charter Fellow of the American Academy of Family Physicians. Photos courtesy Daniel C. Jones, Jr.

Dr. Jones visited Shirley in the 1970s with his son and grandsons. During their tour he shared with family members his recollections of playing at Shirley when his mother Lucy was working as a cook. He told them how he and the late Charles Hill Carter II, slid down the banister of the famous Shirley hanging staircase which rises for three stories with no visible support. He also told them that he and his playmate had carved their initials into the woodwork some place in the house. Sarah probably would have taken a dim view of her grandson’s shenanigans, but she also would have taken great pride in his accomplishments and those of all of her grandchildren. And so, we borrow the words of Langston Hughes to end this tour.

“Three Hundred years in the deepest South, But God put a song and a prayer in my mouth, God put a dream like steel in my soul, Now, through my children, I’m reaching the goal, … Oh, my dark children, may my dreams and my prayers Impel you forever up the great stairs— For I will be with you till no white brother Dares keep down the children of the Negro Mother.”

The Negro Mother, Langston Hughes; Photo courtesy Shirley Plantation.

« All Events

- This event has passed.

Visit Shirley

March 7, 2023 10:00 am - december 30, 2023 4:00 pm, visit shirley in 2023.

Shirley is open to the public.

Shirley’s grounds, gardens, and seven 18th-century outbuildings will be open for self-guided admission Mondays through Saturdays from 10:00 AM until 4:00 PM, with the exit gate closing at 4:30 PM for ticketed guests.

Guided Tours of the home’s first floor are only available for special events and by advance reservation.

___________________________________________________________

Self-Guided Grounds Admission Pricing:

- Adult (Ages 17+): $11.00

- Youth (Ages 7 – 16): $7.50

- Senior Citizens (Ages 60+): $9.50

- US Active Duty Military/US Veterans: $9.50

- US Military Youth (Ages 7 – 16): $6.00

- AAA Adults (Ages 17+): $9.50

- AAA Youths (Ages 7 -16): $6.00

- Students (w/ID): $7.50

- 6 and Under: Free

Self-Guided Grounds Admission Includes:

- Self-guided tour of the grounds and eight 18th-century buildings

- Gift Shop (Open Tuesdays – Saturdays)

- Enslavement Walking Tour on Saturdays at 11:30 am and 1:00 PM

Guided House Tour Pricing (Includes Self-Guided Grounds Admission):

Adult (Ages 17+): $25.00 Youth (Ages 7 – 16): $17.50 Students (w/ID): $17.50 Senior Citizens (Ages 60+): $22.50 US Active Duty Military/US Veterans: $20.00 US Military Youth (Ages 7 – 16): $14.00 AAA Adults (Ages 17+): $22.50 AAA Youths (Ages 7 – 16): $15.75 6 and Under: Free

Admission to Shirley’s guided tour of the home’s first floor includes:

- Self-guided tour of the grounds and 18th-century buildings

- Complimentary audio tour downloadable on a smartphone

- Google Calendar

- Outlook 365

- Outlook Live

Leave a Comment Cancel

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Email Address:

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Shirley Plantation

Built on the banks of the James River, this is Virginia's oldest plantation (1613). It retains an original row of brick service and trade houses – tool barn, ice house, laundry etc – leading up to the big house, which dates from 1738. Established by Edward Hill I, the plantation was subsequently owned by descendants of Robert 'King' Carter and is still home to members of the Hill-Carter family. Guided tours of the downstairs reception rooms are held on the hour.

501 Shirley Plantation Rd. Charles City

Get In Touch

800-829-5121

https://www.shirleyplantation.com

Lonely Planet's must-see attractions

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

18.83 MILES

Richmond is a cultured city, and this splendid art museum is the cornerstone of the local arts scene. Highlights of its eclectic, world-class collection…

Historic Jamestowne

28.15 MILES

Run by the NPS, this fascinating place is the original Jamestown site, established in 1607 and home of the first permanent English settlement in North…

15.96 MILES

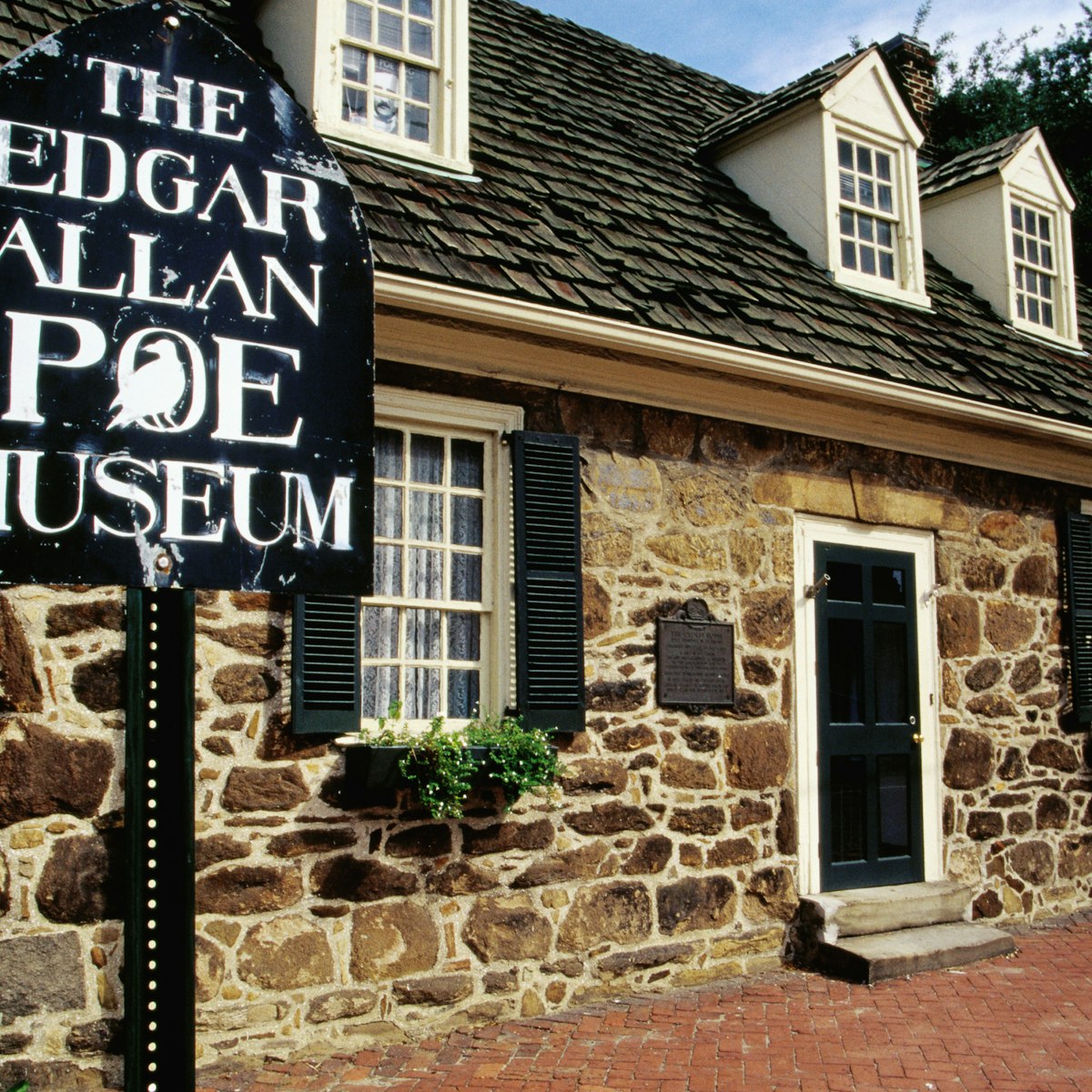

Contains the world's largest collection of manuscripts and memorabilia of poet and horror-writer Edgar Allan Poe, who lived and worked in Richmond…

Virginia State Capitol

16.57 MILES

Designed by Thomas Jefferson, the capitol building was completed in 1788 and houses the oldest legislative body in the Western Hemisphere – the Virginia…

Berkeley Plantation

Dating from 1726, this plantation on the James River was the birthplace and home of Benjamin Harrison V, a signatory of the Declaration of Independence,…

Petersburg National Battlefield Park

Several miles east of town, Petersburg National Battlefield is where Union soldiers planted explosives underneath a Confederate breastwork, leading to the…

National Museum of the Civil War Soldier

16.33 MILES

West of downtown and inside the privately run Pamplin Historical Park, the excellent National Museum of the Civil War Soldier illustrates the hardships…