We need your help now

Support from readers like you keeps The Journal open.

You are visiting us because we have something you value. Independent, unbiased news that tells the truth. Advertising revenue goes some way to support our mission, but this year it has not been enough.

If you've seen value in our reporting, please contribute what you can, so we can continue to produce accurate and meaningful journalism. For everyone who needs it.

- Temperature Check

- The Stardust Inquests

- Inside The Newsroom

- Climate Crisis

- International

Traveller health 'not being prioritised' despite 'shocking' outcomes for children

“WE ARE WORKING with young women who are leaving maternity wards post-pregnancy onto the street, homeless.”

Mary Nevin, a community development worker with Longford Traveller Primary Healthcare Project, told Noteworthy “it’s important for our children to be healthy [and] to be safe” but for the Travellers she works with, this is often not the case.

Hidden homelessness is often to blame for health problems in children, said Nevin, with families living in inappropriate accommodation such as a caravan in a relative’s yard or sleeping on the floor in a sitting room.

“As a result of homelessness, women and their families will not engage with services. It has a huge impact physically, emotionally, and mentally.”

Nevin, a Traveller herself, said she regularly helps mothers who are coming home with a new baby to a “house packed with other family members” and “if someone gets sick, everyone’s going to get sick”.

This year more than any other, due to both the damning Children’s Ombudsman report on overcrowded and unsafe conditions at a Cork halting site as well as the terrible impact of Covid, issues with housing in the Traveller community have hit the headlines.

However, the health implications of living in poor conditions, often with no access to sanitation, electricity and running water, as well as issues including discrimination by health and education providers, have been known by authorities for decades.

These are revealed in the stark health statistics facing Traveller children in every study and piece of Census data available: almost four times higher infant mortality rates than the general population, increased levels of disability at all ages, poor mental health with six to seven times higher a rate of suicide in the Traveller community. The result – a decade lower life expectancy compared to the general population.

At Noteworthy , over the past number of months, we examined supports for Traveller children as part of our TOUGH START investigation. In this part of the series, we looked at health outcomes and spoke to Traveller health workers across the country.

We can today report that:

- The long-awaited Traveller Health Action Plan will be published “soon” but has taken years to develop

- Travellers have the highest rate of perinatal deaths – the number of stillbirths and deaths from 22 weeks’ gestation to seven days after birth – out of all ethnicities

- There was no documented internal discussion that mentions Travellers in relation to the National Maternity Strategy in the months leading up to its publication

- There is no mention of Travellers in HSE hospital staff induction training , in spite of a recommendation in the All-Ireland Traveller Health Study over a decade ago

- Ethnicity identifiers are not being recorded as part of numerous HSE reports, health statistics and, most recently, the Covid vaccine rollout

- Travellers are missing health appointments due to having no postal delivery service

- High rates of Covid in the Traveller community were the “tip of the iceberg and may not reflect all cases”, according to the National Social Inclusion Office

- Systemic issues with housing and education issues are impacting the health of Traveller children

In part one , Children’s Minister Roderic O’Gorman told Noteworthy that “there’s ingrained institutional racism against the Traveller community”. Over the next two weeks will also be investigating systemic issues facing Traveller children in education and housing.

‘Not getting a start in life’

Travellers face an uphill battle even before birth as Ireland’s perinatal death figures reveal that they have the highest rate of perinatal deaths out of all ethnicities measured.

Perinatal mortality is the number of stillbirths and deaths from 22 weeks’ gestation to seven days after birth and is an important measure of maternity care, with the World Health Organisation (WHO) stating it can be used to “assess needs and develop programmes that will reduce avoidable child deaths more quickly”.

Mary-Brigid Collins works with a lot of young mothers through maternal health initiatives run by Pavee Point Traveller and Roma Centre. She is the assistant coordinator of the Primary Healthcare Project in the Dublin-based organisation.

There’s a huge amount of young babies not even getting a start in life – as soon as they’re born, being taken away.

The National Perinatal Epidemiology Centre produces a report on this each year – the most recent in 2017 – and each year since 2013 it stated: “While the numbers involved were small, Irish Traveller, Asian and Black ethnicities were overrepresented in the mothers who experienced perinatal deaths.”

Out of these ethnicities, Noteworthy analysis found that Irish Travellers are by far the most overrepresented for the years 2011 to 2017, with Travellers having an average of more than four times more perinatal deaths than expected for their population size.

This trend continued into recent years with seven deaths recorded in Travellers in 2018 and 10 in 2019, from unpublished HSE data obtained by Noteworthy through a freedom of information (FOI) and press request.

Other measures relating to maternal and neonatal health are also poor in Travellers, with Collins recently highlighting the low breastfeeding rate in the community – just 2% in comparison to the national average of 56% – at a Pavee Point event for National Breastfeeding Week.

The All-Ireland Traveller Health Study in 2010 – which compiled most of the statistics still used in relation to Traveller health, found that infant mortality – children who die under one year of age – was almost four times that of the general population. One of its key priority recommendations was that:

All sectoral aspects of mother and child services merit top priority to reduce infant mortality, support positive parenting outcomes and break the cycle of lifelong disadvantage that starts so early for Traveller families.

More recent data show that Travellers are also experiencing more trauma around birth. Irish Travellers are overrepresented in experiencing severe maternal morbidity which measures unexpected outcomes of labour and delivery that result in significant short- or long-term consequences to a woman’s health.

Traveller babies are overrepresented in infants undergoing therapeutic hypothermia – a treatment for those exposed to reductions of oxygen or blood supply before birth.

The latest report on planned home births reported no Traveller mothers were intending to have home births in 2016 or 2017 – both of the two years reported.

Lack of actions in Maternity Strategy

Despite all of this, Travellers received just one mention in the National Maternity Strategy 2016-2026 in relation to the “lower average age of mothers giving birth”. No mention of higher infant mortality, no mention of lower breastfeeding rates, not one other mention.

Noteworthy found, through FOI , that there were no memos or correspondence within the Department of Health that mentioned Travellers in relation to the strategy in the months leading up to its publication in 2016.

In addition, Irish Travellers didn’t get any mention in the National Maternity Strategy Implementation Plan – a set of actions designed to implement the 10-year strategy.

When asked about this lack of mentions, targeted actions and lack of internal discussion, a spokesperson for the Department of Health said that the pathways within the strategy “are designed to ensure that every woman can access the right level of care, from the right professional, at the right time and in the right place, based on her needs”.

The Department spokesperson added that consultation, both online and in person, was conducted and as a result of this a number of “key recommendations” were made in the strategy “in the areas of targeted additional supports, tailored information and cultural sensitivity”.

The consultation summary reported that “specific groups, such as Travellers, reported feeling stigmatised, which made them reluctant to engage with services for future pregnancies” and also mentioned that “interpersonal skills of healthcare professionals is very important”, using the example of the label ‘Traveller’ and not the care requirement, being put on a cot to ensure appropriate feeding in the context of a metabolic disorder.

“It’s very important that we are included in all these pieces of research and strategies,” Collins told Noteworthy , but added that Travellers should also be included in the resulting targets and plans.

Lynsey Kavanagh, health researcher and policy analyst at Pavee Point, said that this type of “one-size-fits-all policy is developed for the mainstream” but “when groups aren’t equal, you need targeted measures to ensure equity of outcomes”.

There was also no mention of Travellers in any of the following maternity-related reports : National Women and Infants Health Programme Report 2020, Development of Supported Care Pathway Irish Maternity Services 2020 or Irish Maternity Indicator System National Report 2020.

When asked about this, the Department spokesperson said that these “deal with progress made or reports on specific metrics and were not designed to cover ethnicity issues”.

A spokesperson for the HSE also noted that ethnicity is not included in the Maternity Safety Statements which contain information on metrics covering a range of clinical activities and incidents, including perinatal deaths.

They added that these reports are “reviewed by the HSE’s National Women and Infant’s Health Programme and discussed with the six maternity networks at the regular meeting” and though ethnicity is not included, they “do focus discussion about challenges associated with perinatal mortality and actions that may be required”.

‘Outcomes-focused approach’ is key

Lack of targeted actions or specific mentions across a range of Government strategies, policies and implementation plans was an issue highlighted by almost all Travellers that spoke to Noteworthy over the course of this investigation.

When we asked Minister for Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth Roderic O’Gorman about this, given many issues disproportionately impact the Traveller community, he said that with the review of the National Traveller and Roma Inclusion Strategy (NTRIS) happening this year, a “more outcomes-focused approach” is key.

NTRIS is the Government policy framework for addressing the health and other needs of Travellers. In relation to health, it contains over 30 actions across four themes.

O’Gorman said that currently NTRIS is focused on actions such as “implement a policy” or “pass a law” but what people really want to see is “tangible outcomes” such as by a certain date, there will be a certain increase in Traveller-specific accommodation.

These targeted and measurable actions with dedicated funding behind them are what Traveller advocates told us they will be hoping for when the long-awaiting Traveller Health Action Plan is published.

This action plan was one of the main recommendations made by the All-Ireland Traveller Health Study over a decade ago and there is a commitment in the Programme for Government to implement it.

It is also a key NTRIS action and one that Pavee Point’s Kavanagh uses as an example of the lack of implementation of key parts of the Government’s inclusion strategy. “We’re 11 years trying to fight this battle,” waiting for this plan.

The Traveller health researcher welcomed the plan’s consultation process in 2018, but said Travellers on the ground and Traveller organisations are frustrated because they “just don’t see Traveller health being prioritised despite really shocking [health] statistics, which were exacerbated even more during Covid”.

Michelle Hayes, project manager at the HSE’s National Social Inclusion Office said they will be publishing the action plan “soon” and that it is her understanding that it “will be resourced and that there will be further resources for Traveller health in the coming years”.

A spokesperson for the Department of Health (DOH) said that “consideration of the plan and its resource implications has been delayed by the prioritisation of the rollout of the Covid-19 vaccination programme”. They continued:

The Department is committed to providing the leadership and resources to ensure the implementation of the plan by the HSE.

Noteworthy sought all DOH records from 2018 to the end of August in relation to the the action plan – including minutes of meetings and reports – but none were released as they contain “matter relating to the deliberative process”.

However, the FOI response does reveal that over this 2.5-year period there were 23 records relating to the plan, mainly internal interactions or updates and emails between the HSE and DOH. All four in 2021 relate to the DOH seeking comments or sending observations on the draft plan.

Though the HSE was a “key partner” during Covid, when it comes to Traveller health, Kavanagh feels “there is a block somewhere in the Department of Health” and a “lack of prioritisation”.

In addition to the slow development of the action plan, Kavanagh uses the example of the National Traveller Advisory Committee not meeting since 2012.

When this was brought up in the Dáil in 2018 then Minister of State at the Department, Fine Gael’s Catherine Byrne, said that ”there is ongoing and extensive engagement with Traveller organisations” in regards to health inequality experienced by Travellers.

However, Kavanagh said that the advisory committee was “was a mechanism to develop Traveller policy and work with the Department”. She added: “We see his as a huge gap because we don’t have a direct relationship with the Department.”

She also told Noteworthy that Traveller health has received no new development funding since 2008, following austerity cuts – with the exception of some funding provided by initiatives through the Dormant Account Funds.

Though this was raised in the Joint Committee on Key Issues affecting the Traveller Community in 2019 , when then Minister of State at the Department of Health, Fine Gael’s Jim Daly, stated the Department was “open to suggestions” for new development funding for Travellers, Kavanagh said there was no new funding was in recent budgets.

When funding is provided, it does work, she added. The health researcher cited primary healthcare projects that targeted cervical smear and breast cancer screening, with uptake in Traveller women almost double that of the general population.

Childhood trauma impacting health

In addition to stark outcomes facing Traveller babies, older children continue to have poorer health than the general population. For every disability documented in the 2016 Census, Traveller children have a higher proportion recorded than the general population.

For under 15s, the percentage of Traveller children with a disability increased from 8.6% to 9.2% between the 2011 and 2016 Census, with boys being most impacted by all disabilities recorded. This is consistently higher than the level of disability in under 15s in the general population – 5.4% in 2011 and 5.9% in 2016.

The rate of disability worsens – with a growing gap between Traveller children and the general population – in older age groups.

One issue that all Traveller healthcare workers brought up with Noteworthy was poor mental health among all ages, which they said often go back to issues relating to childhood trauma.

The 2010 All-Ireland Traveller Health Study found that suicide represented 11% of all Traveller deaths. It was reported to be seven times higher in men – most commonly in young men aged 15-25 – and five times higher for Traveller women than the general population.

Over a decade later, suicide continues to be a problem in the Traveller community. The HSE gave Noteworthy initial findings of a study underway in the National Suicide Research Foundation examining emergency department presentations due to self-harm and suicide-related ideation.

Though still in progress, the study already found the highest rate of self-harm was observed among Traveller patients aged 50 or older, with Traveller men between 30 and 39 years having the highest risk of presenting with suicide-related ideation.

Patrick*, a Traveller community development worker from Cork City, said “you have to go back to the early days of school, children being segregated, people having childhood trauma, bringing that throughout their lives”.

Segregation policies were present in schools for Travellers throughout the last century, with activists saying that they continue today through the use of reduced school days. This will be the main focus of the next part of our TOUGH START series examining education – out next week.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) are potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood and are linked to chronic health problems, mental health conditions, and substance use problems in adulthood. Patrick said he often sees this in the Traveller community:

A lot of community I know of through a personal capacity and through my work would have had issues of childhood trauma and would have never engaged with a service to deal with that.

He felt that not feeling valued by Irish society plays a huge part in this with “decades and decades of fallout” from the 1963 Report of the Commission on Itinerancy which framed Traveller culture and way of life as a ‘problem’. This “has had a generational impact on people’s mental health”, added Patrick.

Children he works with often have a bleak outlook on life as “from a very young age, they are made feel very different and not wanted”.

Patrick spoke of one seven-year-old he worked with recently who was shocked to realise that Patrick was a working Traveller man as the boy felt he would not be able to get a job in the future. “Imagine all the issues that child will face going forward if that’s their outlook.”

He also said some were left isolated in council estates as “all the settled children were told not to play with the Traveller children”.

When asked if the HSE has any tailored mental health programmes aimed at Traveller children and young people, a spokesperson listed services and mental health supports for Travellers that it, as well as NGOs, provide – including initiatives in collaboration with Traveller organisations around the country.

The spokesperson added that the HSE has recruited eight out of the nine mental health service coordinator posts “to support access to, and delivery of, mental health services for Travellers in each Community Healthcare area”.

A ‘ceiling full of black dots’

Poor accommodation was also listed by every Traveller advocate we spoke to for problems with mental health as well as other – often chronic – health conditions.

In the recent Children’s Ombudsman report, it stated that one parent on the halting site “advised that their mental health team told them that their children’s poor mental wellbeing were linked to their living conditions”.

Overcrowding – according to one of the Ombudsman’s findings – “has resulted in serious risks on the site which present a real and present danger to the safety and health of children”.

Mary Nevin sees a “very high number of children with asthma and other types of chronic illnesses” in her work as a community development worker in Longford.

She was recently helping rehouse a woman with an asthmatic baby living in damp and cold private rented accommodation. She said that Travellers are looking for the basics and are not looking for luxury.

Missed health appointments

During the course of this investigation, Noteworthy uncovered an obstacle to healthcare that is very specific to the Traveller community – access to the postal service.

Pavee Point’s Collins, who lives in a large Traveller group housing scheme, said that no post has been delivered to the over 60 families living there since 2018. She said there have been similar issues on a number of halting sites as well as temporary sites.

To pick up their post, Collins and her neighbours have to travel to their local sorting office which she said is a 35-minute walk, with no direct bus route. “A huge amount of people can’t even get to their post.”

This has resulted in people missing health appointments – something that can result in them or their children being removed from patient lists due to non-attendance policies in most hospitals. “That’s having a huge impact on people’s health,” explained Collins.

The reason the residents were given by An Post for ceasing delivery was that there were loose dogs in the area, the advocate said, but she felt frustrated that delivery was stopped to all houses – not just those with dogs.

By law , on every working day, An Post must deliver to the home of every person in the State, except in such circumstances or geographical conditions deemed exceptional by ComReg.

Noteworthy asked An Post if they plan on resuming postal deliveries to this specific group housing scheme and also for figure on the number of Traveller housing units and halting sites they do not deliver to. However, at the time of publication, no response was provided.

We also asked ComReg is they were addressing this lack of service provision by An Post. A spokesperson said that it “is not aware of, nor has there been any complaint to ComReg from any addresses [in the specific Traveller group housing scheme], of disruptions to the provision of the universal postal service by An Post”.

Collins said they are currently trying to sort out the issue with An Post head office.

Literacy a barrier to children’s health

Even if Travellers do receive their health-related letters, low levels of literacy in the community can have an impact on care.

“Female literacy is a strong determinant of child health and is recognised by WHO,” according to Dr Margaret Fitzgerald, public health lead for social inclusion and vulnerable groups at the HSE National Social Inclusion Office.

When it comes to health literacy, the All-Ireland Traveller Health Survey found that half of Travellers who take prescription medications have difficulty in reading the instructions.

In addition, better provision for those with literacy problems was one of the top actions that Travellers said would improve their health and wellbeing, alongside better accommodation, education and uptake of preventative care services.

From her work with Travellers, Collins has seen the impact of this on maternal care and breastfeeding uptake.

One woman who “wasn’t able to read” and “had literacy problems” was given a book with hundreds of pages of information on pregnancy. “She got the book and put it in the bin as it was no good to her.”

To help with this, the Pavee Mothers initiative – which is funded by the HSE National Social Inclusion Office – published a book and an online resource that “was culturally appropriate and was by Travellers for Travellers”. This month, a new booklet was launched to promote breastfeeding in Traveller women.

However, when it comes to health, Traveller health workers mentioned trust and fear frequently when they spoke to Noteworthy .

Nevin encounters this regularly in her work in Longford and said that “sometimes doctors can use very highfalutin’ words so language can be a barrier”. It can be difficult to build trust, she explained, as “Travellers have been let down so many times”.

Mothers and families can also be fearful of health services for children “because they don’t have the appropriate accommodation” and worry about social worker involvement.

No mention in induction training

One way of addressing this is cultural training for healthcare staff. One of the recommendations of the All-Ireland Traveller Health Study was that a section on Travellers be included as part of routine staff inductions for hospitals with a significant Traveller catchment population. This was also recommended for GPs with a Traveller list.

Through FOI, Noteworthy asked a number of hospitals that treat children for staff induction training records such as reports, policy documents, presentations and information materials that related to Travellers.

This included CHI Temple Street, Crumlin and Tallaght as well as the paediatric section of the six hospitals in areas with a large Traveller catchment population – Cork, Limerick, Galway, Wexford and Drogheda.

The response from all Children’s Health Ireland (CHI) hospitals stated that their induction content doesn’t include “any reference to the Traveller community”. All of the other hospitals provided a similar response.

The statement from Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital, Drogheda, added that guidelines on newborn screening in the Traveller community form part of midwifery education in the college curriculum and this is “supported with practical education during clinical placements”.

When asked if any HSE hospitals include a section on Travellers as part of routine induction of staff, a HSE spokesperson said that “Traveller organisations and the Primary Health Care for Traveller projects around the country provide cultural awareness training on an ongoing basis in response to requests from health service providers”.

They added that with Covid, “they are recommending use of the eLearning module [Introduction to Traveller Health] until this can be complemented with face to face training post-Covid” and this is available to all staff through the HSE’s learning and development portal.

Cultural awareness builds trust

All Traveller advocates we spoke to felt Traveller cultural awareness training was important in healthcare. Traveller community development worker, Patrick*, said people can “have stereotypical views based on negative media” and assumptions can be made.

This training “works to break down those stereotypes and educate people about who Travellers are and what the needs are in the community” which results in better engagement in services.

Training was also important to Nevin, but she said that alongside it, having Traveller-specific workers integrated across the health services is also needed. “A peer-led support available to a Traveller who may feel vulnerable and fearful to engage with health and nursing staff” would make it a lot easier for Travellers, she explained.

This is particularly needed in maternity wards, she added, where Traveller workers could not only support Travellers but also be able to support nursing staff and doctors.

A HSE spokesperson said that “the National Social Inclusion office have provided funding for two Traveller specific maternity resources to support Traveller women’s engagement with the Maternity Hospitals”. They said this “is in response to the challenges identified by Traveller organisations on the ground”.

Dedicated healthcare workers for Travellers also enables greater trust, according to Nevin, who has seen this first hand when they had a public health nurse specifically for Travellers in Longford.

Because of the bond the public health nurse had built with the community, more women were connecting with the nurse and if mothers with small babies had a problem, Nevin said that they felt “they could talk to that nurse about ailments”.

However, their last Traveller specific nurse left for another job in 2018 and wasn’t replaced since. Nevin said because of this young women are being left untreated, and this has been exacerbated more due to Covid.

The community worker knows of one mother with a young baby who was hospitalised with postnatal depression, but Nevin felt she “wouldn’t have needed to go to hospital if she had been seen a little bit earlier”.

When asked if this public health nurse was going to be replaced, a spokesperson for the local HSE community healthcare organisation said that “the Longford Westmeath Travellers health post will be filled when transfers off the national panel are completed”. They did not give a timeline or date for when this would happen.

The added strain of Covid

Pavee Point’s Collins also said that Covid has not helped the situation in terms of Traveller health, with isolating a huge problem within the Traveller community. She added: “You knew you had to do it, you wanted to do it, but it was very difficult to do it.”

Collins lives in a four-bedroom house but with eight others living there, when she had Covid she found it difficult to isolate from her children and grandchildren.

She, alongside other Traveller healthcare workers across the country, were on the ground throughout the pandemic helping with the response and distributing information on prevention measures, testing and the vaccine.

Having Traveller primary healthcare projects already running meant the HSE had somebody to bring materials “straight to the doors” by people who were Travellers themselves, according to Hayes from the National Social Inclusion Office.

There was also “huge cooperation” on sites, said Hayes. “Families themselves were brilliant in outbreak situations – before we even get to the point of engagement, they would already have reorganised themselves.”

Travellers were among the hardest hit by Covid, with over 5,200 cases between March 2020 and April 2021 . That was three times the rate of the general population. To put those case numbers in context, there were just over 30,000 Travellers recorded here in the last Census.

The community was also sicker from the disease, with a hospitalisation rate (4.5%) nine times that of the general population (0.5%).

Outbreaks were a regular occurrence, with more notified in Irish Travellers than any other vulnerable group recorded by the Health Protection Surveillance Centre.

‘Tip of the iceberg’

“At the beginning of Covid, we were very cognisant of the challenges and we knew that we were going to have problems with some of our vulnerable groups,” the HSE’s Fitzgerald told Noteworthy .

“We tried to put in place quite a significant amount of prevention, awareness and a response,” she explained. “Generally it worked very well. But what we feared did happen, and we saw particularly high rates of Covid in Travellers.”

Fitzgerald said the high rates in Travellers were “the tip of the iceberg and may not reflect all cases”. Though Travellers “weren’t that sick” during the first and second waves, she said that “by the third wave they were”.

By the end of the latest wave, there were nearly 250 hospitalisations, 28 people in ICU and 15 deaths in the Traveller community, according to Fitzgerald. Those in ICU included young pregnant women.

Many Travellers were presenting later and sicker in the second and third wave due to, Fitzgerald said, “a combination of culture and social isolation”, including finding it difficult to source medical attention because some “had disengaged from mainstream health services”.

During the pandemic, the HSE “never had such an intense engagement with Traveller health units” and organisations, with “Travellers themselves looking for HSE involvement and health advice”, she added.

When asked if enough was done to address problems with social isolation and other issues encountered by Travellers during the pandemic, a spokesperson for the Department of Health said that there were “concerted efforts by departments and agencies to protect this group from Covid-19″.

The spokesperson said that the Department of Housing “acknowledged the constraints facing people who live in halting sites in adhering to public health advice” and that additional accommodation and sanitary services were provided. This will be covered more extensively as part of our article on Traveller accommodation – out later in this series.

The production of guidance of vulnerable groups, other HSE measures as well as work by the HSE Social Inclusion and Primary Care teams were also listed by the spokesperson, who continued:

“Overall, the impact of Covid-19 was greatly minimised by an intensive and collaborative response from government, the HSE and civil society. Socially excluded groups were prioritised and received priority action in terms of detection, case management and contact tracing.”

Given the large number of cases that occurred, Pavee Point’s Collins is worried about the future impact of the disease and felt “the long-term effects of Covid are going to be showing up” across the community – one which already has a significant disease burden.

‘Not systematically recorded’

Though the Health Protection Surveillance Centre reported outbreaks in Irish Travellers, ethnic identifiers were not a standard part of the pandemic response and are not integrated into the health service – or many other State systems.

For instance, it was recommended in the ‘HSE Vaccine Approach for Vulnerable Groups in Ireland’ report by the HSE National Social Inclusion Office in March 2021, that ethnicity be included in data capture to monitor progress. However, this was not implemented in the Covid vaccine rollout.

The HSE’s Fitzgerald said this was due to the “cyber attack and because of the difficulty with recording ethnicity” which she added is seen “across the whole government system” as it is “not something the State gathers, as a routine”.

Noteworthy asked the HSE about this as well as the vaccine uptake in Travellers by age group but did not receive a response to this query before publication.

Adding ethnicity to all datasets is something that the HSE National Social Inclusion Office has been advocating for many years, according to Hayes. She felt that once the health system is joined up with a unique identifier, that an ethnic identifier would be included. “It would be ridiculous if not,” she added.

Lack of ethnicity data collection in Ireland contrasts with the UK where over 90% of general practices have ethnicity data recorded. Over 80% of acute inpatient and day case records in Scotland also include this data.

When asked about the use of ethnic identifiers, a HSE spokesperson said that “a number of hospitals and health services” are collecting data as per the ethnic categories in the Census, which includes Irish Traveller. These include the Rotunda Maternity Hospital, CHI Temple Street and other services include the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service.

There is a commitment to incrementally roll out the Ethnic Identifier in the National Traveller Roma Inclusion Strategy as well as a commitment in the forthcoming National Traveller Health Action Plan (NTHAP) using the learning emerging from these programs to roll it out further in the health services.

The lack of an ethnic identifier means that much data and statistics relating to Traveller health come from academic research, Census data – now five years old – and the All-Ireland Traveller Health Study – over a decade old.

When Noteworthy asked the HSE for more up-to-date information on suicide in Travellers, a spokesperson said that the Central Statistics Office (CSO) is the source of official suicide data and its sources include findings and verdicts from Coroners.

However, the spokesperson added that ethnicity “is not systematically recorded” across the Coroner system. “Therefore official, complete data on suicide rates in the Traveller community is not available.”

Noteworthy was also unable to obtain records of Traveller complaints in the same eight hospitals we sent an FOI to in relation to induction training due to a lack of ethnic identifier in complaint data.

A whole-of-government approach needed

Though the data may not always be recorded, inequity between the childhood facing Travellers and their peers in the settled community jumps out from every statistic that is available. So, what can be done to close this gap and improve Traveller children’s health?

The HSE’s Fitzgerald said there “had to be greater investment in primary care and resourcing [of] Traveller community health workers”. She added that “Traveller children need wraparound care and support” with other sectors also needing to take action.

Pavee Point’s Kavanagh said that “it’s not just the HSE’s role to address Traveller health inequalities, but a role for all government departments”.

Kavanagh added that “the fact that Travellers are a really young population is indicative of health status” which is in turn “indicative of institutional racism, appalling living circumstances [and] severe overcrowding”.

In 2016 , almost 60% of Travellers were under 25, almost double that of the general population (33%), with just 3% aged 65, less than a quarter that of the general population (13%) .

Community development worker Nevin also felt sorting out the bigger picture – including housing and education – is important to “improve the lives of all Travellers”.

“Our children are our future and it’s important they are treated with the respect and dignity, are able to get an education, go to further education and make an impact in hospitals, council offices, right across the board.”

*Name has been changed.

This article is part of our TOUGH START investigation being led by Maria Delaney of Noteworthy and Michelle Hennessy of The Journal. Over the next two weeks will also reveal systemic issues facing Traveller children in education and housing.

This Noteworthy investigation was done in collaboration with The Journal. It was funded by you, our readers, with support from The Journal as well as the Noteworthy general fund to cover additional costs.

You may be interested in a proposed investigation which is almost funded – BLIND JUSTICE - where we want to look at the experience of Travellers in the justice system.

You can support our work by submitting an idea , funding for a particular proposal or setting up a monthly contribution to our general investigative fund HERE>>

To embed this post, copy the code below on your site

600px wide <iframe width="600" height="460" frameborder="0" style="border:0px;" src="https://www.thejournal.ie/https://www.thejournal.ie/tough-start-pt-2-traveller-children-health-5568495-Oct2021/?embedpost=5568495&width=600&height=460" ></iframe>

400px wide <iframe width="600" height="460" frameborder="0" style="border:0px;" src="https://www.thejournal.ie/https://www.thejournal.ie/tough-start-pt-2-traveller-children-health-5568495-Oct2021/?embedpost=5568495&width=400&height=460" ></iframe>

300px wide <iframe width="600" height="460" frameborder="0" style="border:0px;" src="https://www.thejournal.ie/https://www.thejournal.ie/tough-start-pt-2-traveller-children-health-5568495-Oct2021/?embedpost=5568495&width=300&height=460" ></iframe>

Create an email alert based on the current article

The long road towards acceptance for Irish Travellers

The Irish Traveller community is fighting for official recognition of its ethnic identity and for a way of life.

Avila Park, Dublin, Ireland – In a wooden shed in his back garden, James Collins sits on a low stool hammering out the final touches on a billy can. At 68, he is one of only two remaining traveller tinsmiths in Ireland.

Above the clutter of well-worn tools and scrap sheet metal hang a dozen or so other cans. Nowadays, he says, there’s precious little demand for his trade, and he largely continues it as a hobby, occasionally selling some of his work at vintage craft fairs.

Since the introduction of plastic homeware in the 1960s and 1970s, tinsmithing – traditionally dominated by the historically nomadic community known as Travellers – has effectively died out. Even the block tin, James originally used, is no longer available.

“It’s more difficult to work with,” he says, holding up a gleaming aluminium can. “You can’t make what you want to make out of it because you have to use solder and that won’t take solder.”

READ MORE: Ballinasloe Horse Fair – An ancient Irish tradition

James was raised on the road in the Irish midlands, a traditional upbringing unknown to most Travellers today. “I was bred, born and reared on the road,” he says, “but the young lads today wasn’t. They all grew up in houses and went to school and all this craic. I never got any education, never went to school in my life.”

Until his late 20s, when he settled in Avila Park, a housing estate for Travellers on the outskirts of Dublin, the Irish capital, James plied his trade for farmers, smithing and repairing buckets. “It never goes out of your mind; you’re always thinking, thinking the whole time about the road,” he says.

In comparison, younger generations have little interest in traditional crafts or the travelling lifestyle – James’ children and grandchildren don’t know how to harness a horse, for example. And anti-trespass legislation introduced in the early 2000s, which was used to disperse encampments by the side of roads or on council-owned land, made a nomadic existence increasingly difficult.

Yet, even as the distinct traditions of Irish Travellers seem to fade into the past, the battle for official recognition of their identity continues.

![irish traveller life expectancy Avila Park is a housing estate for Travellers on the outskirts of Dublin [Ruairi Casey/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/455a80191a7f42cba1122a7ca8039da2_18.jpeg)

The search for recognition

Unlike the United Nations and the United Kingdom, Ireland does not recognise Travellers as a separate ethnicity from the non-Traveller community. For decades, human rights organisations and Traveller advocacy groups have been seeking this recognition, but to little avail.

However, on January 26, a parliamentary committee established to investigate the issue stated unequivocally that “Travellers are, de facto, a separate ethnic group”.

“This is not a gift to be bestowed upon them, but a fact the state ought to formally acknowledge,” it further said.

The committee report urged the Taoiseach, Ireland’s prime minister, or the minister for justice to give a statement to the Dail, the Irish parliament, acknowledging this at the earliest opportunity.

This development was welcomed by members of the Travelling community, although some remain cautious in their optimism. It would not be the first time an Irish government has reneged on such commitments – a 2014 parliamentary report made the same recommendation, which was never acted upon.

A history of deprivation and discrimination

An examination of the almost 30,000 Travellers in the Republic of Ireland shows a staggering level of deprivation completely at odds with the non-Traveller community. Another 4,000 to 5,000 Travellers live in Northern Ireland, in a similar situation.

Around half of Travellers have no secondary education and only 1 percent have attended university, according to Pavee Point, a group fighting for the rights of Travellers.

WATCH: Irish travellers facing discrimination

Some 84 percent of Travellers are unemployed, while suicide rates are almost seven times higher than among settled people. A 2010 study found that life expectancy was 15 years lower among men and 11 years lower among women when compared with their settled counterparts.

Discrimination against Travellers remains endemic at social and institutional levels. Being denied entry to businesses is a common occurrence and many try to hide their background when applying for jobs, fearing that potential employers will not hire them.

“Symbolically it would have a profound impact on our collective sense of identity, self-esteem and confidence as a people,” says Martin Collins, the co-director of Pavee Point, on the recognition of Traveller ethnicity.

“Some travellers have internalised [racism] and end up believing that they are of no value, they are of no worth … So that’s the impact. That’s the outcome of both racism and your identity being denied.”

A culture denied

It was a 1963 government report, the Commission on Itinerancy, that has set the tone for the state’s attitude towards Travellers ever since, says Sinn Fein Senator Padraig MacLochlainn, the first person from a Traveller background to be elected to the Irish parliament.

![irish traveller life expectancy Traveller rights groups have been seeking recognition for their community [Ruairi Casey/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/c4d9036a96ee4f959ac072230476ad82_18.jpeg)

The Committee on Itinerancy ‘s terms of reference defined Travellers as a “problem”, whose social ills were “inherent in their way of life,” and outlined the goal of “promot[ing] their absorption into the general community”.

No Travellers were on the committee, nor were they consulted for its report.

“Our people and our state denied their history and decided that they were criminals and they needed to be immersed in with the rest of us,” says MacLochlainn.

This refusal to acknowledge the community’s rich cultural history – notably their own language, Cant, and significant contributions to Irish traditional music – persists today.

Traveller culture is frequently portrayed in the media as separate and distinct, MacLochlainn says, but almost always in negative terms, in exploitation TV shows such as My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding and exposes on Traveller criminality.

“You clearly accept them as a distinct group – why are you making these programmes if you don’t? If they’re a distinct group, could you do it now in positive terms?

“When it comes to negative characterisations, the media, the establishment … in Ireland are more than happy for them to be characterised in negative terms,” the senator says.

Behind James’ shed in Avila Park, traditional and modern Traveller accommodation sit side by side. A wooden barreltop caravan, washed green with blue and red embellishments, sits between two mobile home units, where his younger relatives stay.

Only one has both electricity and running water, which were installed by the family. Power is provided from the house by a yellow cable, wound loosely around plastic drainpipes and holes in its pebbledash exterior.

An early morning fire in a nearby prefabricated unit just a few weeks before offered a bleak reminder of the danger these makeshift electrical fixtures pose. A neighbour raised the alarm and the young couple inside escaped before their home was reduced to a charred husk.

Children burned to death

This near disaster has reminded some people of a fire in the south Dublin suburb of Carrickmines more than a year ago, which continues to cast a shadow over relations between the Traveller and the settled communities.

In the early hours of October 10, 2015, a fire ripped through a halting site killing 10 people, including five children, from two families – the Lynch and Gilbert family and the Connors. The youngest victim was five months old. It was one of the deadliest fires in the history of the Republic of Ireland.

Social workers had raised concerns about the site’s substandard prefabricated units to authorities in the months before the fire, but no action was taken. The blaze and its aftermath would, for many, become an example of the pervasive discrimination Travellers face in Ireland today.

Three days after the fire, some locals blockaded land marked for temporary accommodation for the surviving members of the Connors family, preventing construction vehicles from entering. Though the obstruction was condemned by then Environment Minister Alan Kelly and several Traveller groups, the protesters were successful.

OPINION: Catholic Ireland’s saints and sinners

On October 21, one day before the last victims were buried, the county council announced that the Connors family would instead be resettled on a reclaimed dump on council land in a nearby suburb. At the time of writing, the family remain in that location.

Alongside many expressions of grief on social media after the fire were comments highlighting the discrimination towards travellers in Irish society.

On one popular news site, a comment simply wishing that the victims rest in peace received hundreds of thumbs down votes from other readers. “Hundreds of Irish people gave a thumbs down to an expression of sympathy for children who were burned to death,” says MacLochlainn. “That’s terrifying; that’s absolutely terrifying.”

In response to the tragedy, local authorities across the country conducted fire safety audits at Traveller accommodation sites. “All we got was a few fire alarms, a few fire blankets and some carbon monoxide alarms,” says Collins, of Pavee Point.

“That’s like re-arranging the chairs on the Titanic. That’s totally inadequate. These sites need to be completely redeveloped [and] refurbished, because the sites are just inherently dangerous. Getting a few fire alarms and a few hoses will not rectify the situation.”

For Collins, the long overdue recognition of Traveller ethnicity is an important milestone, but as the Carrickmines example shows, a commitment to materially improving the lives of Travellers is also necessary if they are to be truly equal in their own country.

![irish traveller life expectancy Traveller culture is frequently portrayed negatively in the media [Ruairi Casey/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/20e4db51b2eb41a391ea190a642d302e_18.jpeg)

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Journal of Public Health

- About the Faculty of Public Health of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the United Kingdom

- Editorial Board

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, acknowledgments.

- < Previous

Social inequalities in health expectancy and the contribution of mortality and morbidity: the case of Irish Travellers

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Safa Abdalla, Cecily Kelleher, Brigid Quirke, Leslie Daly, on Behalf of the All-Ireland Traveller Health Study team, Fran Cronin, Anne Drummond, Patricia Fitzpatrick, Kate Frazier, Noor Aman Hamid, Claire Kelly, Jean Kilroe, Juzer Lotya, Catherine McGorrian, Ronnie G Moore, Sinead Murnane, Roisin Nic Carthaigh, Deirdre O'Mahony, Brid O'Shea, Anthony Staines, David Staines, Mary Rose Sweeney, Jill Turner, Aileen Ward, Jane Whelan, Social inequalities in health expectancy and the contribution of mortality and morbidity: the case of Irish Travellers, Journal of Public Health , Volume 35, Issue 4, December 2013, Pages 533–540, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fds106

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The health expectancy of Irish Travellers, a disadvantaged indigenous minority group in Ireland has not been previously estimated. This study aimed to examine health expectancy inequalities between Irish Travellers and the general population.

We used Sullivan's life table method to construct healthy life expectancy (HLE) and disability-free life expectancy (DFLE). The All-Ireland Traveller Health Study provided Irish Traveller population's mortality and health data. Vital registration, census and comparable national survey health data were used for the general population. We calculated the absolute and relative life expectancy, HLE and DFLE gaps between Irish Travellers and the general population and decomposed the HLE and DFLE gaps into mortality and morbidity contributions.

Irish Travellers had consistently lower HLE and DFLE than the general population. The health expectancy gap displayed notable age and gender variations and was wider than the life expectancy gap. Mortality contributed more than morbidity to the health expectancy gap in men but not in women.

This study illustrated the true extent of health inequalities experienced by an indigenous minority in Europe, clarifying the importance of reducing the burden of non-fatal disabling conditions for addressing these inequalities. The health expectancy measure used has application for other similar indigenous minorities elsewhere.

The poor health of disadvantaged indigenous minority groups has been documented in many countries, and is attributable to adverse socio-economic and environmental circumstances, marginalization and discrimination, unfavourable lifestyle factors and inadequate access to good quality health services. 1 , 2

Irish Travellers are one such indigenous minority group in Ireland, who share a distinctive history, value system, language and customs. They represent ∼1% of the population of Ireland and have the typical profile of a disadvantaged group, with lower employment and educational achievement. 3 Routine national data do not capture ethnic or cultural group status, but two major national studies in 1987 and again in 2010 showed that despite absolute improvements in their survivorship over two decades, Irish Travellers continue to fare poorly in terms of infant mortality and life expectancy, compared with the general population. 4 , 5

Commitment to reduce these inequalities is reflected in the national policy target of narrowing the life expectancy gap between Travellers and the general population. 6 However, using only life expectancy to track health inequalities overlooks inequalities in non-fatal health outcomes. Health expectancy, a measure widely used to assess health status and health inequalities in various settings, 7–10 adjusts life expectancy for time lived in less than perfect health, so that health expectancy at a particular age is the average time expected to be lived further in perfect health by an individual who reaches that age.

Studying the health expectancy of Irish Travellers presents a comprehensive yet concise baseline view of health inequalities related to this group. While health expectancy of the general population in Ireland is regularly measured by the European Health Expectancy Monitoring Unit, 11 the health expectancy of Irish Travellers has not been estimated before. This paper aimed to fill this gap by using health expectancy to examine health inequalities affecting Irish Travellers in the Republic of Ireland in 2007–2008. Specifically, we sought to answer the following questions:

What is the health expectancy of Irish Travellers in the Republic of Ireland?

What is the magnitude of inequalities in health expectancy between Irish Travellers and the general population and how does it compare with inequalities in life expectancy?

What is the contribution of mortality and morbidity to inequalities in health expectancy?

Health expectancy is a generic term encompassing a wide range of measures that vary by the underlying definition of health used in their construction. In this study, which was a secondary analysis and synthesis of existing mortality and cross-sectional survey data, we used Sullivan's prevalence-based life table method to construct healthy life expectancy (HLE) at age 15 and at age 65, based on poor self-reported perceived general health, and disability-free-life-expectancy (DFLE) at age 15 and at age 65, based on disability, for male and female Irish Travellers in the Republic of Ireland. A comparable set was constructed for the Irish general population. Life expectancy estimates were included for comparison. Using Sullivan's method required population data, mortality data and cross-sectional health data for each group. 12

Irish traveller data

Population and mortality data.

We used the Traveller population count by age and gender from the All-Ireland Traveller Health Study (AITHS). The study included a census of Irish Travellers and an assessment of their health status and mortality experience. The methodology of the study was published in a series of technical reports. 5 , 13 A Traveller was defined as a person identified by themselves and others as a member of the Traveller community, in keeping with the definition of the Traveller community in the Equal Status Act in Ireland. 14 The census interviews had a response rate of 78% of Traveller families in the Republic of Ireland. All families completed the core census section and a health status interview for a randomly selected child aged 5, 9 or 14 years, or in childless households, a health status or health service utilization interview for a randomly selected adult. AITHS received ethical approval from University College Dublin Research Ethics Committee. A written consent to participate was obtained from the respondents.

The mortality sub-study of AITHS provided the number of deaths over the year preceding the census. Traveller deaths were mainly reported by census respondents, with additional reports from Public Health Nurses. After the elimination of duplicate reports, a final list of Traveller deaths was matched with the official database of death records maintained by the General Registrar Office, using reported name, age, gender and place of death. 63% of the 166 identified deaths were successfully matched, and during the process, a researcher who was experienced in working with Travellers identified 22 further Traveller deaths that were not reported by the other sources, but had typical attributes of Travellers, e.g. trailer halting site for address or tinsmith for occupation. Those were confirmed by local study coordinators and Traveller peer researchers working with Travellers in the area where the deceased resided. More than 90% of the reported ages for those successfully matched were within a 5 years’ range of the ages in the official death record. Thus, for this study we included deaths identified from all sources, using the age and gender of the official record for the matched deaths and the reported age and gender for the unmatched deaths, excluding four males and two females lacking age data.

Perceived general health and disability data

We used perceived general health data and disability data from the health status survey of Irish Travellers aged 15 years and over in private households, conducted in 2008 as part of AITHS. 15 The survey had two components: a core component that included the perceived general health item, with a sample size of 5288 (2574 men and 2689 women) and a detailed component that included the disability item, with a sample size of 1663 (702 men and 961 women). These questions were selected from national instruments for comparability purposes, and conveyed to Traveller respondents in a culturally compatible manner (Table 1 ).

Perceived general health and disability questions used in the AITHS adult health status survey and in the SLAN 2007

a For the purpose of this study, poor health was taken as general health reported to be fair or poor in general.

b The culturally compatible harmonized form of the question administered to Traveller respondents was: ‘Have you any long-term medical problem or disability that stops you doing your daily work?’

General population data

For the general population, we used the number of deaths in 2007 by age and gender, 16 and the total population enumerated at census 2006. 17

The publicly available Survey of Lifestyle, Attitude and Nutrition (SLAN) 2007 data set included comparable perceived general health and disability questions (Table 1 ) for the general population in Ireland. 18 The survey included adults in private households aged 18 years and over and had a sample size of 10 364.

Calculation of health expectancy

Using the survey data from the Travellers and the general population, we estimated the age–gender specific prevalence of poor health and the age–gender specific prevalence of disability. As the Traveller survey was limited to those aged 15 years and over, and SLAN was limited to those aged 18 years and over, we used 5-year age groups starting from 15 years, assuming that the general population prevalence in those aged 18–19 years applied to those aged 15–19 years. SLAN data were available in 5-year age groups ending in the group 75 years and over, which was thus the final open-ended group for the analysis of both the SLAN and Traveller survey data.

For each gender, we constructed abridged life tables in 5-year age intervals, starting from the age of 15 and ending with an open-ended interval of 85 years and over. We used age-specific mortality rates to calculate the person-time contributed by a hypothetical cohort to each age interval, using Chiang's method. 19 Summing the person-time further to the age of 15 years and to the age of 65 years and dividing by the number of hypothetical survivors at the ages of 15 and 65 years, respectively, gave the life expectancy at those ages. For each gender group, and according to Sullivan's method, 12 we used the prevalence of poor health in each age interval to divide the person-time lived in that interval into person-time lived in poor health and person-time lived in good health. We constructed HLE at age 15 and at age 65, by summing the person-time in good health further to ages 15 and 65, respectively, and dividing by the number of hypothetical survivors at those ages. We applied the same approach to construct DFLE at age 15 and at age 65 using disability prevalence.

95% confidence intervals for life expectancy were computed using Chiang's method. 19 95% confidence intervals for HLE and DFLE were calculated according to Mathers (1991), 12 , 20 by quantifying and summing the variance resulting from mortality rates and the variance resulting from the prevalence of poor health and disability, respectively, to obtain the total variance and the standard error.

The gap between Travellers and the general population

We calculated absolute life expectancy, HLE and DFLE gaps as the difference between Traveller and the general population estimates. The standard error of the difference was the square root of the sum of the variance of Traveller and the general population estimates and was used to calculate 95% confidence intervals for the gap. The gap was statistically significant if the intervals did not include zero. To facilitate the comparisons of the gap across different indicators, ages and gender groups, it was also expressed in relative terms as a percentage of the general population estimates.

Mortality and morbidity contributions to the health expectancy gap

We performed a decomposition analysis to quantify the separate contribution of mortality and morbidity to the gap in HLE and DFLE at age 15 using the method described by Nusselder et al . 21 For HLE, the mortality contribution was the difference in person-years in good health due to the different mortality rates of the Travellers and the general population, assuming the same age-specific prevalence of poor health in both groups. The morbidity contribution was the difference in person-years in good health due to the difference in the prevalence of poor health, assuming the same age-specific mortality rates in both groups. The same applied for DFLE.

BM-SPSS statistics 18 (Release Version 18.0.2) was used for survey analysis, and Microsoft Excel (2007) spreadsheets were developed and used for health expectancy calculation and decomposition.

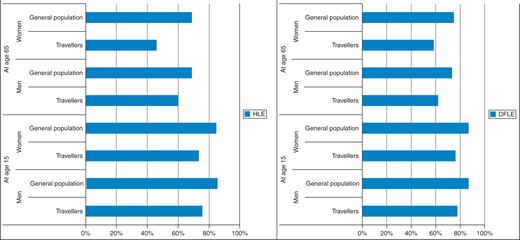

A comparison of the prevalence of poor health and disability between Irish Travellers and the general population is displayed in the online Supplementary data , appendix figure, and shows higher poor health and disability prevalence in Irish Travellers. Table 2 compares HLE and DFLE between Travellers and the general population. Traveller men at the age of 15 were expected to live 36.5 further years in good health and those at the age of 65 were expected to live 6.3 further years in good health, which was less than the HLE of the general population. Similar differentials were observed for women, with HLE at age 15 among Travellers of 41.1 years and at age 65 of 5.7 years. Likewise, Travellers' DFLE was lower than that of the general population. Travellers also had lower healthy proportions and disability-free proportions of their life expectancy than the general population (Fig. 1 ).

LE, HLE and DFLE at age 15 and at age 65 (in years) in Irish Travellers and the general population, together with the absolute and relative gaps, Republic of Ireland, 2007–2008

CI, confidence interval; DFLE, disability-free life expectancy; HLE, healthy life expectancy; LE, life expectancy.

a Absolute gap is in years and is based on subtracting the Irish Traveller estimate from the corresponding general population estimate. Figures differ slightly from differences calculated directly from the values in the table due to rounding.

b Statistically significant at the 0.05 level.

c Relative gap is the absolute gap expressed as a percentage of the general population estimate.

HLE and DFLE as a percentage of life expectancy, Republic of Ireland 2007–2008. The percentage of HLE and DFLE out of life expectancy is presented in horizontal bars, with the x -axis representing the percentage and the y -axis representing gender (men and women) and population group (Irish Travellers and the general population) categories. In both men and women, Travellers had lower percentage HLE at age 15 than that of the general population. Similar patterns were exhibited by HLE at age 65 and by DFLE at age 15 and at age 65.

The findings translated into statistically significant absolute gap between Irish Travellers and the general population in life expectancy, HLE and DFLE (Table 2 ). The gap was narrower at age 65 than at age 15. However, accounting for the lower health expectancy at age 65 revealed a wider relative gap in men (45 and 47% at age 65 compared with 32 and 31% at age 15 for HLE and DFLE, respectively) and women (59% and 51% at age 65 compared with 28% and 27% at age 15 for HLE and DFLE, respectively). The gap in HLE and DFLE at age 15 was wider in men than in women, but wider at age 65 in women than in men. The relative gaps were consistently wider with HLE and DFLE than with life expectancy where the latter showed gaps of 23% in men and 17% in women at the age of 15 and 37% in men and 38% in women at the age of 65.

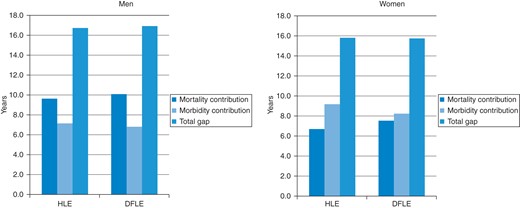

Mortality made a larger contribution to the gap in HLE at age 15 and DFLE at age 15 (9.6 and 10.1 years, respectively) than poor health (7.2 and 6.9 years, respectively) in men (Fig. 2 ). In women, poor health contributed more to HLE at age 15 (9.1 years) than mortality (6.7 years), while disability also made a slightly higher contribution to DFLE at age 15 (8.2 years) than mortality (7.5 years).

Contribution of mortality and morbidity (in years) to the absolute gap in HLE and DFLE at age 15 between Irish Traveller and the general population, Ireland 2007–2008. Vertical bar charts display the contribution in years of the mortality and morbidity components of the gap in HLE and DFLE to the total absolute gap in men and women separately. The total absolute gap is based on subtracting the Irish Traveller estimates from the estimates for their general population counterparts. Mortality made a greater contribution to the gap in HLE and DFLE in men than morbidity, while in women, morbidity contributed more to the gap in HLE and slightly more to the gap in DFLE than mortality.

Main findings of this study

Irish Travellers had lower health expectancy than the general population and are expected to spend a higher proportion of their life expectancy in poor health and with disability. The health expectancy gap between Travellers and the general population was wider in women than in men in older ages. Its relative form was invariably wider than the life expectancy gap, with higher contribution of mortality among men at the age of 15 and significant contribution of morbidity particularly in women where it exceeded that of mortality.

What is already known on this topic

At a local level, Irish travellers have historically had an unfavourable mortality profile compared with the general population in Ireland. 4 , 15 Internationally, inequalities in health expectancy have previously been documented in the USA between African Americans and Whites, 22 , 23 in Belgium between the population of the Walloon region and the culturally distinct population of the Flemish region 24 and in New Zealand between the Maori and the Non-Maori population. 25 , 26 Almost all those studies reported wider gaps based on health expectancy compared with life expectancy, and a wider gap in older ages compared with younger ones was evident in health expectancy comparisons between Black and White ethnicities in the USA. 23 To the best of our knowledge, no other studies have so far reported on the contribution of mortality and morbidity to this gap, although a study in Belgium revealed a predominant contribution of disability to the socio-economic gap in DFLE in both men and women. 27

What this study adds

Our results extend beyond the previously published life expectancy findings for Irish Travellers, by incorporating non-fatal health outcomes. They present a health expectancy profile for Irish Travellers that is typical of disadvantaged indigenous minorities, with an even wider gap, although variations in the data collection methodologies and data completeness may partly explain the difference. Such profile is in line with the adverse patterns among Irish Travellers of the well-recognized array of social, structural and behavioural risk factors that influence their health, such as their high prevalence of diabetes, smoking and physical inactivity. 13 , 28 , 29

Our findings of age–gender variations in health expectancy offer a depiction of health inequalities that sums the effect of selective survivorship and cumulative effects of adverse life circumstances known to influence the magnitude of health inequalities in later life, 30 a picture that would not be as clear if only mortality was considered. Traveller women have always had better survival than Traveller men, 4 , 5 leaving space for life time disadvantage to manifest as a widening gap in poor health and disability in older surviving cohorts. Unhealthy Traveller men selectively die earlier, leaving relatively healthy older cohorts, with a narrower gap compared with women.

The finding of wider health expectancy gap than life expectancy gap confirms that health inequalities would be underestimated if based only on life expectancy. This implies that due attention needs to be paid to the contribution of non-fatal disabling conditions, which could require different interventions than those required for preventing primarily fatal conditions. Our decomposition results have further clarified that this is particularly important in women, where the contribution of morbidity exceeded that of mortality. The commonest reported morbidities among both Travellers and the general population, apart from acute infections, were back conditions and arthritis, 13 the former being considerably more common among Travellers, and both capable of significantly limiting their functional capacity and reducing their quality of life.

The results confirm the need for tailored policies and inter-sectoral action to interrupt the Travellers' life trajectories of disadvantage, in order to reduce the burden of both fatal and non-fatal conditions and improve Travellers' quality of life. Such efforts need to be coupled with the adoption of the health expectancy measure to effectively track progress in this regard, which is as relevant to other disadvantaged indigenous minorities where this is not yet the case. Our study has for the first time clearly illustrated the true extent and components of health inequalities in a disadvantaged indigenous minority group in Europe using novel methods, adding to the growing body of international evidence on health expectancy inequalities.

Limitations of this study

A number of limitations need to be noted regarding our findings. Basing the study on self-reported health status could have affected the comparability of the health expectancy measures between Travellers and the general population, as different groups tend to use different health status levels as cut-off points for the range of survey item responses available. This is due to different health expectations and different semantics attached to survey items and response levels. 31 Such reporting differences were illustrated in surveys utilizing anchoring vignettes. 32 Also Beam et al . 33 found that lack of adjustment for reporting differences led to the underestimation of racial/ethnic inequalities in self-reported health in the USA. A similar process could have biased the Travellers' prevalence of poor health and disability downwards, implying that the gap between Travellers and the general population could even be wider. Also, despite both SLAN and Traveller surveys being interview surveys, with the health status questions having more or less similar locations in the questionnaires, different sampling designs and non-response could have affected their comparability. Using harmonized survey items was the most we could do to maximize the comparability of the health expectancy estimates.

Retrospective identification of Traveller deaths could have led to under-reporting, although this would have been minimized by the use of multiple sources. Limitations associated with Sullivan's method include the use of the currently observed prevalence reflecting past morbidity patterns, and the implicit assumption that there is no recovery from morbidity. 34 However, as we used the same method for both comparison groups, and given the stark differentials in current mortality, we expect our estimates to correctly represent the direction of differentials in HLE and DFLE.

All-Ireland Traveller Health Study was funded by the Department of Health and Children (DoHC) in the Republic of Ireland and the Department of Social Services and Personal Safety of Northern Ireland (DSSPSNI) (grant no. V0350). Fieldwork funding support was received from the Irish Health Service Executive (HSE).

This work is based on the All-Ireland Traveller Health Study, funded by the Department of Health and Children (DoHC) in the Republic of Ireland and the Department of Social Services and Personal Safety of Northern Ireland (DSSPSNI) (grant no. V0350). The views expressed in this study are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of the Department of Health and Children or the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety. The authors wish to thank the Irish Travellers, Traveller peer researchers, study coordinators, Public Health Nurses, the General Registrar Office, Central Statistics Office and AITHS Technical Steering Group. Apart from the authors listed, the AITHS study team members were Ms Fran Cronin, Dr Anne Drummond, Dr Patricia Fitzpatrick, Dr Kate Frazier, Dr Noor Aman Hamid, Ms Claire Kelly, Ms Jean Kilroe, Mr Juzer Lotya, Dr Catherine McGorrian, Dr Ronnie G Moore, Ms Sinead Murnane, Ms Roisin Nic Carthaigh, Ms Deirdre O'Mahony, Ms Brid O'Shea, Prof Anthony Staines, Mr David Staines, Dr Mary Rose Sweeney, Dr Jill Turner, Ms Aileen Ward and Dr Jane Whelan.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

- life expectancy

Supplementary data

Email alerts, citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1741-3850

- Print ISSN 1741-3842

- Copyright © 2024 Faculty of Public Health

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Social inequalities in health expectancy and the contribution of mortality and morbidity: the case of Irish Travellers

Collaborators.

- All-Ireland Traveller Health Study team : Fran Cronin , Anne Drummond , Patricia Fitzpatrick , Kate Frazier , Noor Aman Hamid , Claire Kelly , Jean Kilroe , Juzer Lotya , Catherine McGorrian , Ronnie G Moore , Sinead Murnane , Roisin Nic Carthaigh , Deirdre O'Mahony , Brid O'Shea , Anthony Staines , David Staines , Mary Rose Sweeney , Jill Turner , Aileen Ward , Jane Whelan

Affiliation

- 1 School of Public Health, Physiotherapy and Population Science, University College Dublin, Woodview House, Belfield, Dublin 4, Republic of Ireland.

- PMID: 23315684

- DOI: 10.1093/pubmed/fds106

Background: The health expectancy of Irish Travellers, a disadvantaged indigenous minority group in Ireland has not been previously estimated. This study aimed to examine health expectancy inequalities between Irish Travellers and the general population.

Methods: We used Sullivan's life table method to construct healthy life expectancy (HLE) and disability-free life expectancy (DFLE). The All-Ireland Traveller Health Study provided Irish Traveller population's mortality and health data. Vital registration, census and comparable national survey health data were used for the general population. We calculated the absolute and relative life expectancy, HLE and DFLE gaps between Irish Travellers and the general population and decomposed the HLE and DFLE gaps into mortality and morbidity contributions.