From Distraction to Mindfulness: Latent Structure of the Spanish Mind-Wandering Deliberate and Spontaneous Scales and Their Relationship to Dispositional Mindfulness and Attentional Control

- ORIGINAL PAPER

- Open access

- Published: 13 December 2022

- Volume 14 , pages 732–745, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Luis Cásedas ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5650-6332 1 , 2 ,

- Jorge Torres-Marín ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7663-0699 1 , 3 , 4 ,

- Tao Coll-Martín ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0591-4018 1 , 3 ,

- Hugo Carretero-Dios ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8822-3791 1 , 3 &

- Juan Lupiáñez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6157-9894 1 , 2

2084 Accesses

2 Citations

7 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Mind-wandering is a form of internal distraction that may occur both deliberately and spontaneously. This study aimed to provide a psychometric evaluation of the Spanish version of the Mind-Wandering Deliberate and Spontaneous (MW-D/MW-S) scales, as well as to extend prior research investigating their associations with dispositional mindfulness (Five Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire) and with the ability for attentional control of external distraction (Attentional Control Scale).

In two large samples ( n 1 = 795; n 2 = 1084), we examined latent structure, item- and dimension-level descriptive statistics, and internal consistency reliability scores of the Spanish MW-D/MW-S scales. Partial correlations were used to evaluate their associations with dispositional mindfulness and attentional control. Multiple linear regression and relative weight analyses were used to investigate whether or not, and to what extent, the facets of mindfulness could be uniquely predicted by internal and external distraction.

The Spanish MW-D/MW-S scales demonstrated a two-factor structure, high internal consistency reliability scores, and good nomological validity. Dispositional mindfulness was independently explained by internal and external distraction. MW-S was the largest (negative) predictor of the scores of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, being this association particularly strong for the facet Acting with awareness. Conversely, MW-D was mildly associated with increased mindfulness. In addition, attentional control was found moderately negatively associated with MW-S and mildly positively associated with MW-D.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that the Spanish version of the MW-D/MW-S scales are a useful tool to assess individual differences in deliberate and spontaneous mind-wandering, shed light on the relationship between mindfulness and both internal and external distraction, and accentuate the critical role of intentionality in the study of the mind-wandering phenomena.

Similar content being viewed by others

Positive Psychology: An Introduction

More Things in Heaven and Earth: Spirit Possession, Mental Disorder, and Intentionality

Mohammed Abouelleil Rashed

Brief Resilience Scale (BRS)

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Remaining attentive without getting distracted is a challenging endeavor. As the writer and inventor Hugo Gernsback ( 1925 ) described it, “[p]erhaps the most difficult thing that a human being is called upon to face is long, concentrated thinking” (p. 214). Whether it is sustaining attention to environmental stimuli or maintaining a train of thought in a goal-directed manner, external distraction can readily disturb our focus. This is the case, for example, of the noisy construction work across the street capturing our attention when we are trying to finish an important report. However, external, sensory stimuli are not the only cause by which we can get distracted; as Gernsback ( 1925 ) went on writing, “even if supreme quiet reigns, you are your own disturber practically fifty per cent of the time” (p. 214). In fact, the detour of our attention away from a given task can also be self-generated, or caused by internal distraction. This is the case, for instance, when repetitive thoughts about an uncertain personal circumstance are the reason why we struggle to finish our report. This kind of internally generated distraction refers to the phenomenon most commonly known as self-generated though, or mind-wandering.

Various specific definitions of mind-wandering have been proposed, each of them emphasizing different aspects. One of the most stablished views of mind-wandering defines it as the cognitive process by which we engage in thoughts unrelated to the current demands of the external environment (Schooler et al., 2011 ). This ground-breaking perspective of mind-wandering has generated a wealth of empirical findings and has greatly advanced our understanding of the topic. Being focused on thought content (i.e., task-unrelated thought), however, it does not address the dynamics of the thought process occurring during mind-wandering. In this vein, a second popular account understands mind-wandering as spontaneous thought, that is, as thought that is relatively unconstrained (Christoff et al., 2016 ). Under this view, the main feature of mind-wandering lies not in its content, but in how it transitions relatively freely from one mental state to the next. Note that while these are arguably the two most influential perspectives on mind-wandering within cognitive science, broader philosophical and metatheoretical accounts have also been proposed (see, e.g., Irving, 2016 ; Metzinger, 2013 ).

Likely due to its fundamentally private nature, mind-wandering has traditionally been relatively understudied as compared to other psychological phenomena. Over the last 15 years, however, the scientific interest in understanding why and how the mind wanders has seen a striking surge. A reason why this phenomenon may have inevitably gained popularity can be found in how ubiquitous it is. Conservative estimates of its prevalence indicate that we spend around 20% of our waking time in mind-wandering (Seli et al., 2018a ); less conservative estimations suggest that we spend up to 50% engaged in it (Killingsworth & Gilbert, 2010 ). Mind-wandering can be assessed using various subjective techniques, most commonly questionnaires, probe-caught, and self-caught methods (Smallwood & Schooler, 2015 ). Interestingly, mind-wandering has been linked not only with costs (e.g., impaired reading comprehension due to attentional disengagement) but also with certain benefits in areas including future planning or creative thought (Mooneyham & Schooler, 2013 ).

While mind-wandering was originally considered a single, unitary phenomenon, in recent years it has become increasingly acknowledged that it is best characterized, rather, as a family of related yet distinct processes (Seli et al., 2018c ) . One of the earliest and most prominent categorizations of the mind-wandering phenomena highlights that it can occur both with and without intention (Seli et al., 2016b ) . Whereas the latter refers to the automatic process by which our attention shifts from the external environment to internally generated cognitions, more often related to personal current concerns of neutral or negative valence, the former alludes to the same process but happening in a voluntary fashion, more commonly in relation to positively valenced content such as fantasies or daydreams (Carriere et al., 2013 ). Providing an example of the importance of this distinction, one study investigated the role of task difficulty in the prevalence of intentional and unintentional mind-wandering using thought-probes during a cognitive-behavioral assessment (Seli et al., 2016a ) . The study found that, although overall rates of mind-wandering did not differ across conditions, participants reported more intentional mind-wandering in the easy condition, but more unintentional mind-wandering in the difficult one. Had the distinction between intentional and unintentional mind-wandering been ignored, the authors would have incorrectly concluded that there was no effect of task difficulty over the rates of task-unrelated thought.

The tendency to engage in intentional versus unintentional mind-wandering has also been studied at the individual differences level. In this vein, Carriere et al., ( 2013 ) developed the Mind-Wandering: Deliberate ( MW-D ) and Mind-Wandering: Spontaneous ( MW-S ) scales to address the role of the intentionality of mind-wandering in its relationship to fidgeting (i.e., the tendency to make spontaneous, involuntary movements). The instrument was composed by eight statements (four items per scale) reflecting the proposed two-factorial structure of mind-wandering. Although this study lacked an assessment of the dimensionality of the MW-D/MW-S scales, it provided initial evidence of their discriminant associations by showing that only MW-S was a (positive) predictor of fidgeting (indicating that the tendency to make involuntary movements is related to involuntary, but not deliberate, forms of mind-wandering). More recently, Marcusson-Clavertz and Kjell ( 2018 ) conducted a formal psychometric validation procedure of the MW-D/MW-S scales, showing that they were optimally fitted by a two-factor solution (with the best fit attained excluding the third item from the MW-S) and demonstrated a psychometrically sound behavior, including strong measurement invariance across gender and time, and good reliability of their scores (α/ω ≥ 0.81/0.82; test–retest ≥ 0.75 [2-week-interval]). This initial validation study also showed that MW-D and MW-S differed in their prediction of external outcomes: Whereas MW-D was linked to openness and experience-sampling reports of intentional mind-wandering, MW-S predicted generalized anxiety and experience-sampling reports of unintentional mind-wandering.

Subsequent psychometric research has validated the MW-D/MW-S scales for use in other languages and cultures, including Chinese (Carciofo & Jiang, 2021 ), German (Martarelli et al., 2021 ), and Italian (Chiorri & Vannucci, 2019 ). These studies successfully replicated the original two-factor structure, and provided further evidence of their nomological validity by examining correlates with a wide range of external variables. Chiorri and Vannucci ( 2019 ) found that MW-S was more strongly correlated with other self-report measures of mind-wandering, and to attentional control, than was MW-D (while both scales predicted daydreaming to a similar extent). Martarelli et al., ( 2021 ) examined the associations of the MW-D and MW-S scales to trait boredom, similarly finding that the correlation was substantially weaker for MW-D than for MW-S. Carciofo and Jiang ( 2021 ) found that MW-S showed stronger positive correlations with negative affect and attentional lapses, and stronger negative correlations with agreeableness and positive affect; on the contrary, MW-D was more strongly positively associated to openness (in line with Marcusson-Clavertz & Kjell, 2018 ). Overall, these studies made possible to disentangle deliberate and spontaneous expressions of mind-wandering at the individual differences level in various cultural contexts other than the original (i.e., reinforcing the cross-cultural validity of the scales). Note however that, to date, there is no available version of the MW-D/MW-S scales that can be administered in Spanish samples.

Classically, mind-wandering has been considered antithetical to the construct of mindfulness, which can be broadly defined as the psychological inclination to attend to present-moment experience while having an attitude of acceptance towards it (Baer, 2019 ; Bishop et al., 2004 ). The distinction between intentional and unintentional mind-wandering, however, has revealed that this relationship may be more complex. In one study, Seli et al., ( 2015 ) investigated the unique contributions of the MW-D and MW-S scales to the five facets assessed by the Five Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer et al., 2006 ). The study found that the two types of mind-wandering were dissociable (i.e., an effect was observed for one but not the other, or the effects were in opposite direction) in their relationship to four of the five facets, and that deliberate mind-wandering was actually positively related to two of them (Observing and Non-reactivity to inner experience). These results thus nuanced the relationship between mindfulness and mind-wandering, emphasizing again the necessity of considering intentionality when investigating the mind-wandering phenomena.

As just described, the study by Seli et al., ( 2015 ) provided the first trait-level evidence characterizing the facets of mindfulness in terms of (spontaneous and deliberate) mind-wandering, or what we have termed above as internal distraction. However, to date, no study has yet attempted to extend these findings to encompass also external distraction as part of its nomological network. In particular, there are two specific sets of questions that remain to be addressed regarding external distraction, as it relates to internal distraction and mindfulness, as described next.

First, it is as yet unclear how MW-D and MW-S associate to the vulnerability to engage in external distraction. From an individual differences perspective, external distraction can be assessed with the Attentional Control Scale (ACS; Derryberry & Reed, 2002 ), a well-stablished two-factorial measure of the capacity to sustain ( Focus ) and reorient ( Shift ) attention in a goal-directed manner in the face of external events (e.g., music or other people talking around). Prior research has found that both Focus and Shift dimensions were largely negatively correlated to MW-S, while MW-D was only slightly negatively correlated (Carriere et al., 2013 ) or unrelated to them (Chiorri & Vannucci, 2019 ). However, and importantly, these studies relied exclusively on bivariate correlational analyses, which hinders the interpretation of their results given that MW-D and MW-S are also highly correlated constructs themselves. Instead, the study of the relationships of the MW-D/MW-S scales to attentional control or any other external variable is better suited by analytical approaches that can account for their commonality, thus quantifying the amount of variance that is uniquely explained by each of them (e.g., partial correlation or multiple linear regression analyses; Seli et al., 2015 ).

Second, it is also not known whether the tendency to engage in internal distraction (as assessed by MW-D and MW-S) and external distraction (as assessed by Focus and Shift) uniquely contribute to explain individual differences in the facets of mindfulness (as assessed by the FFMQ), and to what extent. Given that internal and external distraction are also expected to be moderately overlapping processes (Carriere et al., 2013 ; Chiorri & Vannucci, 2019 ; for a latent variable approach, see also Unsworth & McMillan, 2014 ), addressing both simultaneously as predictors of mindfulness is required to disentangle the distinctive contributions of each distraction-related dimension to the latter construct. Critically, without a combined analytical approach, it is not possible to know whether the variance common to mindfulness and internal distraction (as reported by Seli et al., 2015 ) is unique, or can be accounted for by individual differences in external distraction instead.

On the basis of these considerations, we conducted the present study pursuing two intertwined aims: (1) to develop and validate the Spanish-language version of the MW-D/MW-S scales for research use with Spanish samples and (2) to replicate and extend prior findings on the relationship between the facets of mindfulness (FFMQ), internal distraction (MW-D and MW-S), and external distraction (Focus and Shift). Regarding our second aim, and more precisely, we set out to (2a) replicate the findings by Seli et al., ( 2015 ) linking internal distraction and the facets of mindfulness; (2b) provide original evidence of the relationship between internal and external distraction; and (2c) provide original evidence of the unique contributions of internal and external distraction to the facets of mindfulness. In order to address our first aim, we conducted a forward- and back-translation procedure from the original instrument and evaluated its psychometric adequacy including item- and dimension-level distributional properties, dimensionality, and internal consistency reliability. Our second aim was addressed by means of partial correlations and multiple linear regressions combined with relative weight analyses. Note that while this second part was primarily motivated by an interest to empirically characterize the structure of relationships between dispositional mindfulness, mind-wandering, and attentional control, it was also a means to provide evidence of the nomological validity of the Spanish version of the MW-D/MW-S scales.

Participants

Two independent samples of 808 and 1095 participants were collected for this study. In both cases, the subjects were invited using the institutional email lists of the University of Granada, and participated in exchange of course credits (if they were undergraduate Psychology students) or monetary compensation (if they were students from other programs or university personnel). From each sample, we removed participants identified as completion time outliers (i.e., those with ± 3 standard deviations [SD] from the group mean in completing the survey; n excluded = 13 and n excluded = 11, respectively). The samples were thus finally comprised by 795 (sample 1 [S1]: 72.01% female; M age = 23.80 years, SD = 5.54) and 1084 (sample 2 [S2]: 74.91% female; M age = 22.80, SD = 5.49) participants. All subjects gave informant consent prior to participation.

The development of the Spanish version of the MW-D/MW-S scales comprised (1) translation of instructions for administration and items from the original English version (Carriere et al., 2013 ) into Spanish by two of the authors (LC and JL); and (2) independent back-translation into English by a professional native English translator. Inconsistencies between both versions were assessed through discussion and iterations of translation and back-translation until consensus among authors and translator was achieved.

In regard to the administration of the measures during the study session, the procedure was virtually identical for S1 and S2. After providing informant consent, participants were presented with a battery of sociodemographic questions, followed by the MW-D/MW-S, the FFMQ, and the ACS. Measures were implemented and data were collected online using the platform LimeSurvey ( http://www.limesurvey.org ). Participants were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time.

Mind-Wandering Deliberate and Spontaneous Scales

The MW-D/MW-S scales (Carriere et al., 2013 ) comprise four items each, assessing the propensity to engage in task-unrelated thought or mind-wandering voluntarily (e.g., “I allow my thoughts to wander on purpose”) and involuntarily (e.g., “I mind wander even when I’m supposed to be doing something else”), respectively. Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“rarely”) to 7 (“a lot”), except for the third item of the MW-D (from 1 = “not at all true” to 7 = “very true”) and the third item of the MW-S (from 1 = “almost never” to 7 = “almost always”). The original English version has been recently validated by Marcusson-Clavertz and Kjell ( 2018 ), demonstrating adequate factorial and construct validity, as well as good internal consistency reliability scores (MW-D: ranging from α = 0.86 to α = 0.90; MW-S: ranging from α = 0.81 to α = 0.82). The psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the MW-D and MW-S can be found in the “ Results ” section. The items and instructions for administration of the scales are provided in Supplementary Material S1 .

Five Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire

The FFMQ (Baer et al., 2006 ; Spanish version by Cebolla et al., 2012 ) is a 39-item instrument rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“never or very rarely true”) to 5 (“very often or always true”), designed to assess five distinct domains of trait mindfulness. (1) Observing (from here on referred to as Observe ), or the tendency to attend to and noticing internal and external experiences including sensations, emotions, and thoughts (e.g., “I notice the smells and aromas of things”). (2) Describing ( Describe ), or the ability to label internal experiences, and particularly emotions, with words (e.g., “I can usually describe how I feel at the moment in considerable detail”). (3) Acting with awareness ( Actaware ), or the tendency to be grounded on present-moment experience as opposed to behaving mindlessly or in autopilot (e.g., “I do jobs or tasks automatically without being aware of what I’m doing”, reversed item). (4) Non-judging of inner experience ( Nonjudge ), or the tendency to appraise thoughts and feelings from a non-evaluative stance (e.g., “I disapprove of myself when I have irrational ideas,” reversed item). And (5) non-reactivity to inner experience ( Nonreact ), or the capacity to experience thoughts and emotions without having to reflexively respond to nor being caught up by them (e.g., “I watch my feelings without getting lost in them”). The Spanish version of the FFMQ has shown adequate factorial and external validity, as well as good internal consistency reliability scores, both in previous research (ranging from α = 0.80 to α = 0.91; Cebolla et al., 2012 ) and in the two samples reported herein (see the “ Results ” section).

Attentional Control Scale

The ACS (Derryberry & Reed, 2002 ; Spanish by Pacheco-Unguetti et al., 2011 ) is a 20-item questionnaire rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“almost never”) to 4 (“always”). It was developed to assess two distinct attention-related factors, namely the capacity to maintain the focus of attention in the presence of distractors (Focus; e.g., “I have difficulty concentrating when there is music in the room around me,” reversed item) and the ability to efficiently switch attention between tasks or stimuli including the reorienting of attention from distractors to the primary task (Shift; e.g., “After being interrupted, I have a hard time shifting my attention back to what I was doing before,” reversed item). While originally comprised by 20 statements, subsequent psychometric research has proposed alternative, more efficient versions of the scale (12-item version in Judah et al., 2014 ; 8-item version in Carriere et al., 2013 ). For the present study, we conducted three competing confirmatory factor analyses on the ACS as translated into Spanish by Pacheco-Unguetti et al., ( 2011 ) in order to obtain the best fitting version of the Spanish version of the scale (i.e., 20 vs. 12 vs. 8 items). As detailed in Supplementary Material S2 , the best fit was attained by the 8-item version, which was therefore the one used for analyses. The 8-item ACS has shown adequate internal consistency reliability scores, both in previous research (Focus: ranging from α = 0.77 to α = 0.81; Shift: ranging from α = 0.69 to α = 0.82; Carriere et al., 2013 ) and in the two samples reported herein (see the “ Results ” section).

Data Analyses

To analyze the psychometric properties of the MW-D/MW-S scales, first descriptive statistics (i.e., mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis) and corrected item-total correlations were computed for all the items. The dimensionality of both scales was assessed by means of a set of confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) with robust maximum likelihood estimator. The relative fit of three models was tested: (a) one-factor structure or general factor of mind-wandering (model 1); (b) two-factor structure reflecting the deliberate and spontaneous components of mind-wandering (model 2); and (c) the same two-factor structure but excluding the item 3 of the MW-S (model 3) as recommended in the validation study of the original version of the scale (Marcusson-Clavertz & Kjell, 2018 ). Model fit was assessed following Kaplan’s ( 2009 ) recommendations, with CFI ≥ 0.90, TLI ≥ 0.90, RMSEA ≤ 0.08, and SRMR ≤ 0.08 reflecting adequate fit. After corroborating the internal structure of our scales, dimension-level descriptive statistics were calculated for the MW-D/MW-S scales, as well as for all other outcome variables, along with their internal consistency reliability coefficients using both Cronbach’s alpha (α) and McDonald’s omega (ω).

Pearson’s correlations were used to assess the bivariate relationships between MW-D/MW-S, FFMQ, and ACS. Subsequently, partial correlations were conducted to assess the unique associations of MW-D and MW-S (controlling for each other) with dispositional mindfulness and attentional control. Finally, multiple linear regressions along with relative weight analyses (RWAs) were conducted to assess the unique contributions of both internal distraction (MW-D and MW-S) and external distraction (Focus and Shift) to each of the mindfulness facets. By also introducing RWA into our analytic strategy, we overcame one limitation of the regression approach, namely that it does not reliably estimate the specific variance explained by each predictor under analyses, particularly when they are intercorrelated (see Tonidandel & LeBreton, 2011 ). To account for the influence of sociodemographics, age and sex were introduced in a first step in the regression model, and internal and external distraction variables in a second step (both methods: enter). For parsimony, only the final models are reported.

All the analyses were independently conducted in both S1 and S2. To control for the type I error rate, significance level was set at α = 0.01 and results were only interpreted as true positives when replicated in both samples. To avoid drawing conclusions upon findings without practical significance, we set the smallest effect size of interest (SESOI) at r = 0.10, R 2 = 0.01. Note that both S1 and S2 were sensitive enough to statistically detect effect sizes equal or higher than the SESOI, given α = 0.01. We used Mplus 8.1 software (Muthén & Muthén, 2017 ) and RStudio 2021.09.0 (RStudio Team, 2021 ) to conduct the CFA and RWA, respectively; all other analyses were conducted in Jamovi 1.6.23 (Jamovi Project, 2021 ).

Psychometric Properties of the Spanish MW-D and MW-S Scales

Item analyses.

Descriptive statistics for all the items of the Spanish MW-D/MW-S scales in S1 and S2 are provided in Supplementary Material S3 . As shown, no floor/ceiling effects in item responses were detected (5.08 ≥ M ≥ 2.96). High between-subject variabilities also emerged ( SD ≥ 1.65). Skewness and kurtosis indexes strongly suggested scores for all items to follow the normal distribution ( ≤|2| in all cases; Pituch & Stevens, 2015 ). Finally, the items of both scales displayed high discrimination indexes in both samples (MW-D from 0.65/0.60 [item 4] to 0.81/78 [item 2] in S1/S2; and MW-S from 0.58/0.51 [item 1] to 0.67/62 [item 4] in S1/S2). Together, these results indicate adequate item properties for Spanish-language version of the MW-D/MW-S scales.

Factor Structure

As shown in Table 1 , fit indices indicated that both two-factor structures (models 2 and 3) outperformed the one-factor solution (model 1) in terms of model fit. Mirroring the Marcusson-Clavertz and Kjell’s ( 2018 ) validation study for the English version of the instrument, the exclusion of the item 3 of the MW-S scale (model 3) outperformed the version with the full set of items (model 2). Model 3 thus appeared as the best fitting factor structure, globally yielding acceptable to good fit indices across both S1 and S2. We thus conducted the remaining analyses excluding the item 3 of the MW-S scale. All items were significant and showed high loadings in their corresponding latent factors across both samples, namely MW-D ≥ 0.69/0.65 and MW-S ≥ 0.62/0.58 in S1/S2. Latent correlation between the scores of the MW-D and MW-S only reflected a moderated overlapping (≈ 0.50), which provides further support for a two-factorial model of mind-wandering as the most interpretable solution.

Descriptive Statistics and Reliability

As shown in Table 2 (upper rows), the mean scores, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis of the Spanish MW-D/MW-S scales closely resemble the values originally obtained by Marcusson-Clavertz and Kjell ( 2018 ). Importantly, skewness and kurtosis coefficients indicated normal-like distribution of the scores of the MW-D and MW-D across both S1 and S2 ( ≤|2| in all cases). In terms of the internal consistency of their scores, the Spanish MW-D/MW-S scales showed convincing coefficients for research purposes (all α/ω ≥ 0.71). Note that both estimators (α and ω) largely converged in S1 and S2.

Bivariate and Partial Correlation Analyses

As can be seen in Table 2 (mid and bottom rows), the distributional properties and internal consistency reliability scores of the FFMQ facets and ACS factors were also satisfactory. Table 3 displays the structure of bivariate correlations among the three sets of constructs, for both S1 and S2. The pattern is highly similar across samples, highlighting the stability of the associations. As found in previous research (Carriere et al., 2013 ; Chiorri & Vannucci, 2019 ; Seli et al., 2015 ), MW-S was more strongly related to both dispositional mindfulness and attentional control than MW-D, as reflected by a larger number of observed correlations and stronger effect sizes. However, also in line with these studies, the MW-D and MW-S scales showed to be strongly associated to each other ( r ≈ 0.40), which hinders direct interpretation of their bivariate relationships with external variables (Seli et al., 2015 ). Thus, a series of partial correlations was conducted next.

The results of the partial correlation analyses between MW-D and MW-S, controlling for each other, and the FFMQ facets in both S1 and S2 can be found in Table 4 (left columns). As shown, the pattern of findings was similar across samples. Observe was found to be positively related to both types of mind-wandering, while the only consistent finding revealed for Describe, Actaware, and Nonjudge was their negative relationship to MW-S. In turn, Nonreact demonstrated to be positively associated with MW-D. All other contrast resulted non-significant either statistically, p ≥ 0.01, or practically, r < 0.10, in at least one of both samples. Nonjudge and Actaware showed medium-to-large and large (negative) correlations to MW-S, respectively; effect sizes for all other results ranged from small to medium. This pattern of findings closely replicates the seminal study by Seli et al., ( 2015 ).

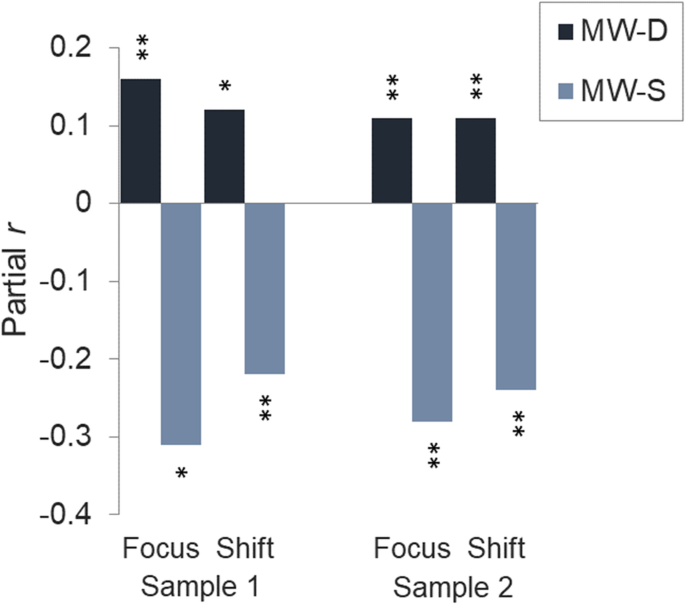

Going beyond Seli et al.’s ( 2015 ) findings, we further investigated the pattern of associations between deliberate and spontaneous mind-wandering (controlling for each other) and the two factors of attentional control. The results of these set of partial correlations are also displayed in Table 4 (right columns). As can be seen, small positive associations were found between MW-D and both Focus and Shift, while small-to-medium negative associations were revealed between these and MW-S. This was indicative of a double dissociation (see also Fig. 1 ).

Partial correlations of MW-D (controlling for MW-S) and MW-S (controlling for MW-D) with Focus and Shift in sample 1 ( n = 795) and sample 2 ( n = 1084). MW-D, Mind-Wandering: Deliberate; MW-S, Mind-Wandering: Spontaneous. * p < 0.01; ** p < 0.001 (two tailed)

Regression and Relative Weight Analyses

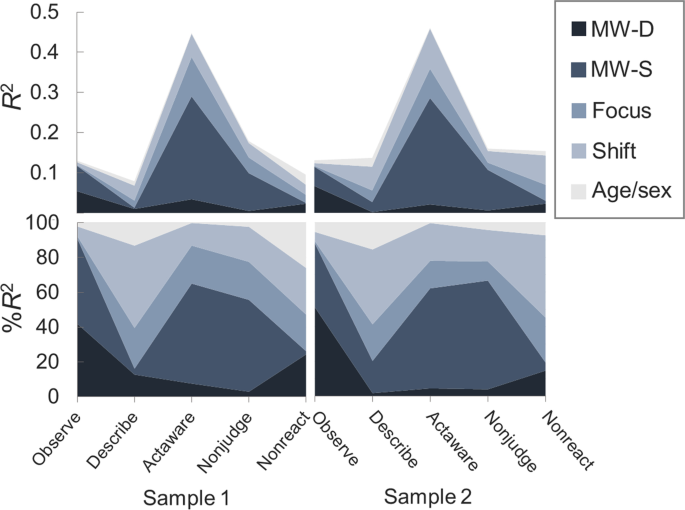

The results of the linear regression and RWA characterizing the five facets of mindfulness in terms of internal distraction (MW-D and MW-S) and external distraction (Focus and Shift) are provided in Table 5 and Table 6 for S1 and S2, respectively. They are also displayed graphically in Fig. 2 , which depicts for each of the mindfulness facets (1) the absolute variance explained by predictor ( R 2 ), and (2) the relative variance (or percentage of the total variance explained by the full model) explained by predictor (% R 2 ). As shown, the pattern of findings obtained by using this analytic approach, too, is consistent across samples. In step 1, age and sex demonstrated to be generally unrelated to mindfulness, with two exceptions: (1) older participants self-reported higher scores on Describe; and (2) male participants tended to self-report higher scores on Nonreact. Note that both effects were small in magnitude.

Stacked area plots depicting the absolute and relative variance explained (upper and lower panels, respectively) by internal distraction (MW-D and MW-S) and external distraction (Focus and Shift) across mindfulness facets, after controlling by age and sex, in sample 1 ( n = 795) and sample 2 ( n = 1084). MW-D, Mind-Wandering: Deliberate; MW-S, Mind-Wandering: Spontaneous

Internal and External distraction variables were introduced in the step 2 of the regression procedure. The total variance explained by the full model ranged from R 2 = 0.079 (Describe) to R 2 = 0.460 (Actaware), indicating that internal and external distraction explained the mindfulness facets by a medium to large extent in all cases. In both samples, internal distraction was the domain most strongly predictive of Observe, Actaware, and Nonjudge, whereas external distraction was the best predictor of Describe and Nonreact. Averaged across mindfulness facets and samples, the variance explained by internal and external distraction was R 2 = 0.111 and R 2 = 0.077, respectively; as per each individual factor, MW-S was the variable with the largest predictive power, R 2 = 0.086, followed by Shift, R 2 = 0.043, Focus, R 2 = 0.034, and MW-D, R 2 = 0.025.

At the level of individual mindfulness facets, each of them followed a distinctive pattern of contributions of MW-D, MW-S, Focus, and Shift, as described next (see also Fig. 2 ; the direction and statistical significance of the relationships are provided in Tables 5 and 6 ). The facet Observe demonstrated small-to-medium positive associations with both MW-D and MW-S. Describe, on the contrary, only appeared to be consistently linked to external distraction, showing a small-to-medium positive association with Shift. Notably, Actaware was the facet most strongly related to both internal and external distraction (see the central peak in the upper panels of Fig. 2 ), demonstrating medium positive associations with Focus and Shift, and a large negative association with MW-S. Nonjudge, in turn, showed a pattern similar to the former facet but of reduced magnitude, revealing small-to-medium positive associations with Focus and Shift, and a medium negative association with MW-S. Finally, Nonreact showed positive associations in the small-to-medium range with MW-D, Focus, and Shift. All other predictors resulted non-significant either statistically, p ≥ 0.01, or practically, R 2 < 0.01, in at least one of both samples.

Based on data from two independent samples comprising over 1800 participants, the present study aimed to evaluate the psychometric adequacy of the Spanish version of the MW-D/MW-S scales and to replicate and extend prior findings of their relationship with the facets of mindfulness and attentional control. The psychometric evaluation of the Spanish MW-D/MW-S scales indicated adequate validity and reliability. Factor analyses confirmed that the instrument is best characterized as two distinct factors reflective of deliberate and spontaneous or mind-wandering, as was initially conceived by Carriere et al., ( 2013 ). Mirroring the study formally assessing the psychometric properties of the original version of the scales (Marcusson-Clavertz & Kjell, 2018 ), the best model fit was attained excluding the third item from the MW-S scale; we thus recommend future research not include it into analyses. All remaining items showed convincing distributional properties, as did the two mind-wandering dimensions themselves. In all cases, internal consistency coefficients (α/ω) were ≥ 0.71 for MW-S and ≥ 0.86 for MW-D, which can be interpreted as evidence of high reliability, specially taking into account the concision and brevity of administration of the scales, composed by 3 and 4 items, respectively.

We successfully replicated the seminal findings relating spontaneous and deliberate mind-wandering to the five facets of mindfulness (Seli et al., 2015 ). There was only one exception, namely: whereas a negative relationship between Non-reactivity to inner experience and MW-S was reported originally, we could only reproduce this result in our second sample (but not in the first one). This seeming discrepancy, however, may not be surprising in the context of a fairly small effect size. Note that the statistical power achieved by our first sample ( n = 795) to capture true effects of small size ( ρ = 0.10) with a two-tailed test ( α = 0.01) was 0.60; meaning that the probability of committing a type II error was 40% (Faul et al., 2009 ). To further explore this interpretation, we conducted a fixed-effects meta-analysis of the results across both samples ( n = 1879), which afforded a statistical power of 0.96 in the same scenario. A small yet significant negative partial correlation between Non-reactivity to inner experience and spontaneous mind-wandering was revealed ( r = − 0.12, p < 0.001; see Supplementary Material S4 for details). Considering also this result, the pattern of findings obtained with the Spanish MW-D/MW-S in the present study appears virtually interchangeable with the findings obtained by Seli et al., ( 2015 ) using the original scales.

Interestingly, our assessment of the relationships between deliberate and spontaneous mind-wandering (controlling for each other) and the two factors of attentional control revealed the existence of a double dissociation: While participants more susceptible to engage in spontaneous mind-wandering also reported higher vulnerability to external distraction, those with a higher propensity to engage in mind-wandering in a voluntary fashion reported being less vulnerable to it (regarding both Focus and Shift). This finding is suggestive of the idea of “strategic” mind-wandering, which posits that individuals are able to and benefit from modulating their level of mind-wandering to accommodate the demands of the environment (e.g., Seli et al., 2018b ). Prior research has shown that this ability differs across individuals and situations. For instance, it has been shown that participants with high versus low working memory capacity display less mind-wandering during high demanding tasks (Kane & McVay, 2012 ), while, on the contrary, tend to engage more in mind-wandering when task demands are low (Levinson et al., 2012 ). In line with these findings, our results suggest that the proclivity to voluntarily let the mind wander, presumably when the environmental demands are more permissive, may be protective in more attention-demanding situations not only against subsequent task-unrelated though (as prior studies suggest) but also against becoming distracted by external events.

The present study also revealed various key aspects of the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and internal and external distraction. While, as discussed above, both deliberate and spontaneous mind-wandering have shown predictive capacity in explaining inter-individual variability in the facets of mindfulness (Seli et al., 2015 ), our study extend these results by showing that the capacity for attentional control of external distraction independently explains the facets of mindfulness over and above the variance accounted for by the mind-wandering factors. This finding, moreover, seems relatively stable across mindfulness facets, as in four of them at least one of the two factors of attentional control significantly contributed to explain a unique proportion of variance (the only exception was Observe). Complementarily, in all but one case, both deliberate and spontaneous mind-wandering were retained as significant predictors of the mindfulness facets after including Focus and Shift in the regression model (the previously observed relationship between Describe and MW-S was entirely accounted for by external distraction). Importantly, these findings indicate that internal and external distraction are (partially) independent domains in their relationship to dispositional mindfulness, being both relevant insofar the two of them uniquely contribute to explain it.

On average, internal distraction showed greater predictive capacity than did external distraction in explaining individual differences in dispositional of mindfulness (11.1% vs 7.7% of variance). While the contribution of external distraction was evenly shared by Focus and Shift (3.4% and 4.3% of variance), the great majority of the variance explained by internal distraction was accounted for by spontaneous mind-wandering—by far the stronger predictor across mindfulness facets (8.6% of variance on average). Importantly, these results suggest that dispositional mindfulness, while also protective against external distraction, is most strongly predictive of a decreased vulnerability to engage in mind-wandering, particularly without intention (note however that for Observe, the effect was in the opposite direction). By contrast, the results also indicate that dispositional mindfulness is linked, to a lesser degree, to an increased tendency to engage in mind-wandering voluntarily (2.5% of variance).

This latter finding echoes the one discussed above about the positive link between deliberate mind-wandering and attentional control, in that both indicate that the proclivity to allow the mind to wander on purpose, presumably in low attention-demanding contexts, may be mildly linked to traits that are adaptive in nature. Interestingly, both results are in line with earlier research indicating that mind-wandering may come not only with costs but also with certain benefits (e.g., Franklin et al., 2013 ; Gable et al., 2019 ), while in addition suggest that the intentionality with which it occurs may be a critical aspect determining its adaptive value. This can be interpreted under the so-called content and context regulation hypothesis (Smallwood & Andrews-Hanna, 2013 ), which proposes that the adaptive or maladaptive nature of a given mind-wandering episode is dependent on both its thought content and the task context in which it appears. While speculative, it seems reasonable to conceive deliberate mind-wandering as characterized by being positive in content and deployed in contexts where it is not critical for performance in the primary task, maximizing its adaptive value. As will be further discussed below, future research may find fruitful to further examine the intentionality of mind-wandering under the context and content regulation framework.

A finer-grained analysis at the level of individual mindfulness facets revealed that each of them was characterized by a distinctive pattern of unique contributions of the factors of distraction. While discussing these patterns in detail is beyond the scope of the present report, there is one salient observation worth mentioning: Acting with awareness was, by a large difference, the facet of mindfulness most strongly predicted by both internal and external distraction (28.8% and 16.5% of variance, respectively). Indeed, the total variance explained for this facet was more than twice than for any of the remaining ones. Importantly, virtually all variation accounted for by internal distraction was attributable to spontaneous mind-wandering (deliberate mind-wandering did not reach significance as predictor in any of our two samples). Acting with awareness thus appeared as the most protective facet against distraction, being particularly strongly associated to a decreased vulnerability to involuntarily engage in task-unrelated thought. This finding is consistent with the theoretical characterization of dispositional mindfulness, within which Acting with awareness was originally described as “attending to one’s activities of the moment [as] contrasted with behaving mechanically while attention is focused elsewhere” (Baer et al., 2008 , p. 330). It is also consistent with recent meta-analytical evidence indicating that Acting with awareness is the only mindfulness facet reliably linked with enhanced performance across a range of cognitive-behavioral attentional tasks, most of which are presumably affected by both external and internal types of distraction (Verhaeghen, 2021 ).

All in all, the main contributions of the present study can be summarized as follows. First, we have shown that the Spanish MW-D/MW-S scales have favorable psychometric properties, including factor structure, distributional properties, and internal consistency reliability scores. We have also shown that they have adequate nomological validity, since they displayed a notably similar pattern of relationships with the facets of mindfulness as compared to the original scales, while also demonstrating satisfactory discriminant properties in relation to the factors of attentional control. Collectively, these findings suggest that the Spanish MW-D/MW-S scales constitute a promising measure to assess individual differences of intentional and unintentional mind-wandering with Spanish samples. Second, we have shown that dispositional mindfulness, as primarily driven by the facet Acting with awareness, is independently associated to both enhanced attentional control of external distractions and, more prominently, decreased vulnerability to spontaneous mind-wandering. We have also shown that deliberate mind-wandering, by contrast, is mildly associated to increased dispositional mindfulness. Deliberate mind-wandering, in addition, was also found to be mildly linked to greater attentional control, which in turn was linked to diminished spontaneous mind-wandering. Together, these findings broaden our understanding of the relationship between mindfulness and (internal and external) distraction, while continue to accentuate the critical role of intentionality in the study of the mind-wandering phenomena.

Limitations and Future Research

This study is not without limitations. First, we used convenience samples primarily composed of young, well-educated, healthy participants mostly without meditation experience, a methodological feature that precludes the generalization of our conclusions beyond this particular population. In light of this, future research must consider extending our results to other distinct, more specific populations. Relatedly, future studies may find it fruitful to examine the variables assessed here in their interaction with mindfulness meditation training. In particular, given the strong link we observed between Actaware and MW-S, future research could test whether mindfulness-based interventions explicitly targeting this particular facet are specifically efficacious in reducing maladaptive, involuntary forms of mind-wandering. Second, the model fit of the CFA, while generally good, had margin for improvement. To obtain an even clearer representation of the latent structure of mind-wandering, future studies could consider creating additional indicators specifically addressing central aspects of each type of mind-wandering, so as to more strongly demarcate its two-factorial nature.

Third, our results were entirely based on self-report measures, which place them at risk of method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2012 ) and other artifacts (Quigley et al., 2017 ). Future research must consider exploring the correlates of deliberate vs. spontaneous mind-wandering using alternative methodologies, such as cognitive-behavioral tasks tapping into distractibility processes; as for their relation to mindfulness, the breath counting task may serve as an alternative, more ecological assessment (Levinson et al., 2014 ). Finally, and as outlined above, future studies may find it fruitful to explore the intentionality of mind-wandering in light of the content-context regulation hypothesis (Smallwood & Andrews-Hanna, 2013 ). For instance, it is conceivable that the positive links of deliberate mind-wandering with mindfulness and attentional control were stronger in individuals who are especially skillful at engaging in strategic mind-wandering, and that do so about topics particularly positive or constructive (and vice versa). Future research is warranted to further explore this intriguing possibility.

Data, Materials, and Code Availability

The data and the R scripts used for analyses are provided at the Open Science Framework ( https://osf.io/ceg89/ ).

Baer, R. A. (2019). Assessment of mindfulness by self-report. Current Opinion in Psychology, 28 , 42–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.10.015

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13 (1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191105283504

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., Walsh, E., Duggan, D., & Williams, J. M. G. (2008). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15 (3), 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191107313003

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmoda, J., Segal, Z. V., Abbey, S., Speca, M., Velting, D., & Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11 (3), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy/bph077

Article Google Scholar

Carciofo, R., & Jiang, P. (2021). Deliberate and spontaneous mind wandering in Chinese students: Associations with mindfulness, affect, personality, and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 180 , 110982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110982

Carriere, J. S. A., Seli, P., & Smilek, D. (2013). Wandering in both mind and body: Individual differences in mind wandering and inattention predict fidgeting. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 67 (1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031438

Cebolla, A., García-Palacios, A., Soler, J., Guillen, V., Baños, R., & Botella, C. (2012). Psychometric properties of the Spanish validation of the Five Facets of Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ). The European Journal of Psychiatry, 26 (2), 118–126. https://doi.org/10.4321/S0213-61632012000200005

Chiorri, C., & Vannucci, M. (2019). Replicability of the psychometric properties of trait-levels measures of spontaneous and deliberate mind wandering. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 35 (4), 459–468. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000422

Christoff, K., Irving, Z. C., Fox, K. C. R., Spreng, R. N., & Andrews-Hanna, J. R. (2016). Mind-wandering as spontaneous thought: A dynamic framework. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17 (11), 718–731. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2016.113

Derryberry, D., & Reed, M. A. (2002). Anxiety-related attentional biases and their regulation by attentional control. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111 (2), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.111.2.225

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41 (4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Franklin, M. S., Mrazek, M. D., Anderson, C. L., Smallwood, J., Kingstone, A., & Schooler, J. W. (2013). The silver lining of a mind in the clouds: Interesting musings are associated with positive mood while mind-wandering. Frontiers in Psychology, 4 , 583. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00583

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gable, S. L., Hopper, E. A., & Schooler, J. W. (2019). When the muses strike: Creative ideas of physicists and writers routinely occur during mind wandering. Psychological Science, 30 (3), 396–404. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618820626

Gernsback, H. (1925). The Isolator. Science and Invention, 13 (3), 214–281.

Google Scholar

Irving, Z. C. (2016). Mind-wandering is unguided attention: Accounting for the ‘“purposeful”’ wanderer. Philosophical Studies, 173 (2), 547–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-015-0506-1

Jamovi Project. (2021). jamovi (Version 1.6.23) [Computer software]. https://www.jamovi.org

Judah, M. R., Grant, D. M. M., Mills, A. C., & Lechner, W. V. (2014). Factor structure and validation of the attentional control scale. Cognition and Emotion, 28 (3), 433–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2013.835254

Kane, M. J., & McVay, J. C. (2012). What mind wandering reveals about executive-control abilities and failures. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21 (5), 348–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721412454875

Kaplan, D. (2009). Structural equation modeling: Foundations and extensions (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452226576

Book Google Scholar

Killingsworth, M. A., & Gilbert, D. T. (2010). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science, 330 (6006), 932–932. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1192439

Levinson, D. B., Smallwood, J., & Davidson, R. J. (2012). The persistence of thought: Evidence for a role of working memory in the maintenance of task-unrelated thinking. Psychological Science, 23 (4), 375–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611431465

Levinson, D. B., Stoll, E. L., Kindy, S. D., Merry, H. L., & Davidson, R. J. (2014). A mind you can count on: Validating breath counting as a behavioral measure of mindfulness. Frontiers in Psychology, 5 , 1202. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01202

Marcusson-Clavertz, D., & Kjell, O. N. E. (2018). Psychometric properties of the spontaneous and deliberate mind wandering scales. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 35 (6), 878–890. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000470

Martarelli, C. S., Bertrams, A., & Wolff, W. (2021). A personality trait-based network of boredom, spontaneous and deliberate mind-wandering. Assessment, 28 (8), 1915–1931. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191120936336

Metzinger, T. (2013). The myth of cognitive agency: Subpersonal thinking as a cyclically recurring loss of mental autonomy. Frontiers in Psychology, 4 , 931. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00931

Mooneyham, B. W., & Schooler, J. W. (2013). The costs and benefits of mind-wandering: A review. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 67 (1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031569

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). MPlus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

Pacheco-Unguetti, A. P., Acosta, A., Marqués, E., & Lupiáñez, J. (2011). Alterations of the attentional networks in patients with anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25 (7), 888–895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.04.010

Pituch, K. A., & Stevens, J. P. (2015). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences: Analyses with SAS and IBM’s SPSS (6th ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315814919

Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63 (1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Quigley, L., Wright, C. A., Dobson, K. S., & Sears, C. R. (2017). Measuring attentional control ability or beliefs? Evaluation of the factor structure and convergent validity of the attentional control scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 39 (4), 742–754. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-017-9617-7

RStudio Team. (2021). RStudio (Version 2021.09.0) [Computer software]. http://www.rstudio.com

Schooler, J. W., Smallwood, J., Christoff, K., Handy, T. C., Reichle, E. D., & Sayette, M. A. (2011). Meta-awareness, perceptual decoupling and the wandering mind. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15 (7), 319–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2011.05.006

Seli, P., Carriere, J. S. A., & Smilek, D. (2015). Not all mind wandering is created equal: Dissociating deliberate from spontaneous mind wandering. Psychological Research Psychologische Forschung, 79 (5), 750–758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-014-0617-x

Seli, P., Risko, E. F., & Smilek, D. (2016a). On the necessity of distinguishing between unintentional and intentional mind wandering. Psychological Science, 27 (5), 685–691. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797616634068

Seli, P., Risko, E. F., Smilek, D., & Schacter, D. L. (2016b). Mind-wandering with and without intention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20 (8), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2016.05.010

Seli, P., Beaty, R. E., Allan, J., Smilek, D., Oakman, J., & Schacter, D. L. (2018a). How pervasive is mind wandering, really? Consciousness and Cognition, 66 , 74–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2018.10.002

Seli, P., Carriere, J. S. A., Wammes, J. D., Risko, E. F., Schacter, D. L., & Smilek, D. (2018b). On the clock: Evidence for the rapid and strategic modulation of mind wandering. Psychological Science, 29 (8), 1247–1256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618761039

Seli, P., Kane, M. J., Smallwood, J., Schacter, D. L., Maillet, D., Schooler, J. W., & Smilek, D. (2018c). Mind-wandering as a natural kind: A family-resemblances view. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22 (6), 479–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2018.03.010

Smallwood, J., & Andrews-Hanna, J. (2013). Not all minds that wander are lost: The importance of a balanced perspective on the mind-wandering state. Frontiers in Psychology, 4 , 441. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00441

Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2015). The science of mind wandering: Empirically navigating the stream of consciousness. Annual Review of Psychology, 66 (5), 487–518. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015331

Tonidandel, S., & LeBreton, J. M. (2011). Relative importance analysis: A useful supplement to regression analysis. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9204-3

Unsworth, N., & McMillan, B. D. (2014). Similarities and differences between mind-wandering and external distraction: A latent variable analysis of lapses of attention and their relation to cognitive abilities. Acta Psychologica, 150 , 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2014.04.001

Verhaeghen, P. (2021). Mindfulness as attention training: Meta-analyses on the links between attention performance and mindfulness interventions, long-term meditation practice, and trait mindfulness. Mindfulness, 12 , 564–581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01532-1

Download references

Funding for open access publishing: Universidad de Granada/CBUA LC was supported by a doctoral fellowship from “la Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434; fellowship code LCF/BQ/DE18/11670002). JTM was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship “Margarita Salas” at the University of Granada, financed by the European Union–Next Generation EU funds. TCM was supported by a doctoral fellowship (FPU17/06169). HCD was supported by research projects grant from the Spanish Agencia Estatal de Investigación, Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (PID2019-104239 GB-I00/SRA (State Research Agency/ https://doi.org/10.13039/501100011033 )). JL was supported by research projects grants from the Spanish Agencia Estatal de Investigación, Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (PID2020-114790 GB-I00) and Junta de Andalucía (PY20_00693). This paper is part of the doctoral dissertation of the first author under the supervision of the last author. Funding for open access charge: Universidad de Granada / CBUA.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Mind, Brain and Behavior Research Center (CIMCYC), University of Granada, Granada, Spain

Luis Cásedas, Jorge Torres-Marín, Tao Coll-Martín, Hugo Carretero-Dios & Juan Lupiáñez

Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Granada, Granada, Spain

Luis Cásedas & Juan Lupiáñez

Department of Research Methods in Behavioral Sciences, University of Granada, Granada, Spain

Jorge Torres-Marín, Tao Coll-Martín & Hugo Carretero-Dios

Department of Social Psychology and Quantitative Psychology, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Jorge Torres-Marín

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

LC: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, visualization, writing—most of original draft, review, and editing; JTM: conceptualization, methodology, formal analyses, writing—part of original draft, review, and editing; TCM: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing; HCD: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing—review and editing; JL: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Luis Cásedas .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval.

The study was conducted according to the ethical principles established by the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments, and was as part of a larger research project (PSI2017-84926-P) approved by the University of Granada Ethical Committee (536/CEIH/2018).

Informed Consent

All subjects provided informed consent.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 41 KB)

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cásedas, L., Torres-Marín, J., Coll-Martín, T. et al. From Distraction to Mindfulness: Latent Structure of the Spanish Mind-Wandering Deliberate and Spontaneous Scales and Their Relationship to Dispositional Mindfulness and Attentional Control. Mindfulness 14 , 732–745 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-02033-z

Download citation

Accepted : 21 November 2022

Published : 13 December 2022

Issue Date : March 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-02033-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Deliberate mind-wandering

- Spontaneous mind-wandering

- Mindfulness

- Acting with awareness

- Attentional control

- Individual differences

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Psychology: Research and Review

- Open access

- Published: 02 June 2017

Translation and validation of the Mind-Wandering Test for Spanish adolescents

- Carlos Salavera 1 , 2 ,

- Fernando Urcola-Pardo 3 ,

- Pablo Usán 1 , 2 &

- Laurane Jarie 1 , 2

Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica volume 30 , Article number: 12 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

6026 Accesses

9 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Working memory capacity and fluent intelligence influence cognitive capacity as a predictive value of success. In line with this, one matter appears, that of mind wandering, which partly explains the variability in the results obtained from the subjects who do these tests. A recently developed measure to evaluate this phenomenon is the Mind-Wandering Questionnaire (MWQ).

The objective of this work was to translate into Spanish the MWQ for its use with adolescents and to validate it and to analyze its relation with these values: self-esteem, dispositional mindfulness, satisfaction with life, happiness, and positive and negative affects.

A sample of 543 secondary students: 270 males (49.72%) and 273 females (50.28%) were used, who completed the questionnaire, and also did tests of self-esteem, dispositional mindfulness, satisfaction with life, happiness, and positive and negative effects. The transcultural adaptation process followed these steps: translation, back translation, evaluation of translations by a panel of judges, and testing the final version.

Validity analyses were done of the construct (% explained variance = 52.1), and internal consistency was high (α = .766). The coefficients of correlation with the self-esteem, MASS, satisfaction with life, happiness, and affects scales confirmed the questionnaire’s validity, and a multiple regression analysis ( R 2 = 34.1; model F = 24.19. p < 0.001) was run.

Conclusions

The Spanish version of the questionnaire obtained good reliability coefficients and its factorial structure reliably replicated that obtained by the original measure. The results indicate that the Spanish version of the MWQ is a suitably valid measure to evaluate the mind-wandering phenomenon.

As human beings, we tend to be distracted by the activities we perform, which is when the mind tends to wander back to the past or to plan the future. This spontaneous tendency to produce thoughts and to freely allow our minds to wander, despite external stimuli, is considered a typical characteristic of the human mind (Smallwood and Schooler, 2006 ). Mind wandering is understood as a mental process during which attention is distracted from a task underway to focus on the contents that our minds intrinsically produce (Smallwood and Schooler, 2015 ). As it is one of the most common activities that the human mind performs, it occurs in practically all day-to-day activities, and individuals are gripped to their own mind events between 10 and 50% of the time they are awake (Kane, Brown, McVay, Silvia, Myin-Germeys & Kwapil, 2007 ; Killingsworth and Gilbert, 2010 ). Mind wandering presents wide inter-individual variability, and the mind-wandering trait appears as the personal characteristic of a tendency toward mind wandering for a given period of time (Mrazek, Smallwood, Franklin, Baird, Chin & Schooler, 2012a ).

Repetitive thoughts are considered an adaptive function of human beings. Despite the negative connotations associated with this concept, mind wandering is not itself considered a negative characteristic. Similar negative connotations are attached to common terms like cognitive failures, resting state, rumination, distraction, attentional failures, absent-mindedness, repetitiveness, and the like (Baars, 2010 ). Planning the future is one of the most beneficial results connected with mind wandering as its appearance is associated with thoughts about the future, and not with the past or present (Schooler, Smallwood, Christoff, Handy, Reichle & Sayette, 2011 ). Thoughts that focus on the future are increased by self-reflection (Smallwood and O’Connor, 2011 ) and by prioritizing personal goals (Stawarczyk, Majerus, Maj, Van der Linden and D’Argembeau, 2011 ), which is reduced by negative moods (Smallwood and O’Connor, 2011 ). Along these lines, mind wandering comes over as an adaptive advantage as it can diminish distress by predicting future events to better adapt to one’s own environment (Bar, 2009 ). Mind wandering allows information that cannot be analyzed when a stimulus emerges to be systematized because the semantic manipulation of information cannot take place while a stimulus occurs (Binder, Frost, Hammeke, Bellgowan, Rao & Cox, 1999 ), and is thus associated with effective coping (Greenwald and Harder, 1995 ) and creativity (Sio and Ormerod, 2009 ). This anticipative capacity and planning of the future allow problems to be creatively solved (Baird, Smallwood, Mrazek, Kam, Franklin & Schooler, 2012 ).

High levels of mind wandering are related with low moods (Killingsworth and Gilbert, 2010 ) and negative thinking (Smallwood, O’Connor, Sudbery, and Obonsawin, 2007 ). An increase in negative thoughts in relation to mind wandering has been associated with individual levels of depression (Marchetti, Koster and De Raedt, 2012 ). This association may be due to mind wandering which, given the spontaneous emergence of thoughts, is associated with paying more attention to one’s own thoughts, emotions, and experiences (Smallwood and Schooler, 2015 ). This marked increase in self-attention may mean being at more risk of self-assessment, which has been associated with negative emotions (Mor and Winquist, 2002 ). The appearance of repetitive thoughts is relevant for the appearance and maintenance of emotional disorders (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema and Schweizer, 2010 ) through brooding and worrying. Although both of these constructs are related with mind wandering, they are considered to semantically differ. Indeed, worrying is defined as expecting possible negative results in the future (Borkovec, Robinson, Pruzinsky and DePree, 1983 ), while brooding is defined as the repetitive response model that involves the constant development of distress symptoms, and of the causes and consequences of distress (Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco and Lyubomirsky, 2008 ).

Increased mind wandering and paying more attention to one’s own thoughts, emotions, and experiences have been related with low levels of self-esteem (Mrazek, et al. 2013 ). Nevertheless, paying more attention to oneself is not necessarily considered a negative activity for self-esteem. So mindfulness is considered a construct that contrasts with mind wandering (Mrazek, Smallwood, and Schooler, 2012b ). The mindfulness construct has been defined in many forms, and all its definitions coincide in that it is a matter of paying intentionally more attention to the present time and not taking a judgemental attitude about experience (Brown and Ryan, 2003 ; Germer, 2005 ; Kabat-Zinn, 1990 ; Segal, Williams and Teasdale, 2002 ). This non-judgemental attitude makes mindfulness appear positively related with self-esteem (Kong, Wang, and Zhao, 2014 ; Rasmussen and Pidgeon, 2011 ). In turn, self-esteem is considered a predictor of satisfaction with life (Diener and Diener, 1995 ; Mäkikangas and Kinnunen, 2003 ). Hence, the aforementioned factors may be considered modulators in the relation between mind wandering and satisfaction with life.

As no valid scale exists to measure mind wandering, the usual way to assess it involves periodically interrupting individuals while they do a task, and asking them to report the extent to which their attention was related to on-task or on task-unrelated concerns (Mrazek, Smallwood, Franklin, Baird, Chin & Schooler, 2012a ). In the last few years, the Mind-Wandering Questionnaire (MWQ) was developed. It is a simple validated tool designed to directly measure mind-wandering trait levels. Its design offers good reliability and validity in both adult and adolescent populations (Mrazek, 2013 ), and has been validated to Chinese (Luo, Zhu, Ju and You, 2016 ) and Japanese (Kajimura and Nomura, 2016 ). In Spain, studies have been conducted on mind wandering by electroencephalography in relation to movement (Melinscak, Montesano and Minguez, 2014 ). However, no references about psychometric studies of the construct are available. For this reason, the objective of this work was to translate into Spanish and to validate the Mind-Wandering Questionnaire and to analyze its relation with the values of self-esteem, dispositional mindfulness, satisfaction with life, happiness, and positive and negative affects among adolescents.

For the Spanish MWQ adaptation purposes, the following phases were followed:

Translation of the original scale into Spanish by a group of expert researchers in mindfulness.

The translated scale was administered to a sample of 50 people to detect any items that did not work well, and possible difficulties in understanding because items were poorly translated or badly written. No special difficulties were found in either the items or the instrument in general.

The work with the scale centered on the analysis, translation, and validation of the MWQ. The whole study sample ( N = 543) was recruited from four high school centres.

The objective of this research was to validate the MWQ. After finishing the translation processes (Fig. 1 ), the first step was to study the reliability of the scales. To do this, statistics were obtained as the scale was not adapted to Spanish. This analysis informed us about the value of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of reliability. In this questionnaire, good values were obtained (α = .766), which indicates good internal consistency among the scale elements.

Diagram showing the phases followed to adapt the MWQ

Participants

The research sample comprised 543 secondary students, 270 males (49.72%) and 273 females (50.28%). Subjects voluntarily participated and gave signed informed consents. The ethical norms of the Declaration of Helsinki were respected. The study population’s mean age was 17.24 years, and their ages ranged from 16 to 18 years, with a standard deviation of 1.015.

Measurements

The Mind-Wandering Questionnaire (MWQ) (Mrazek, 2013 ), is a self-report 5-item questionnaire that evaluates the levels of the mind-wandering trait. It is a 6-point Likert-type scale that goes from 1 (almost never) to 6 (almost always). Some item examples are “I have difficulty maintaining focus on simple or repetitive work” or “I do things without paying full attention”. The total MWQ score is the sum of the five items within a 5–30 range. After obtaining permission from the author of the MWQ, it was translated. The results and its reliability/validity are described in later sections of this document.

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) (Brown and Ryan, 2003 ) is a simple scale that is quickly administered and globally evaluates an individual’s dispositional capacity of being alert and aware of the present experience in his/her daily life. MAAS is a 15-item questionnaire that scores on a Likert scale from 1 (almost always) to 6 (almost never). It measures the frequency of the mindfulness state in activities of daily living without having to train subjects. Scores are obtained using the arithmetic mean of all the items, and high scores indicate a greater mindfulness state. In the present study, this scale shows high internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.878.

The Subjective Happiness Scale (Lyubomirsky and Lepper, 1999 ) is an overall measure of subjective happiness that evaluates a molar category of well-being as an overall psychological phenomenon by considering the definition of happiness from the respondent’s perspective. It comprises four items with Likert-type responses and is corrected by summing the points obtained and then dividing them by the total number of items. In the present study, this scale shows high internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.845.

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin, 1985 ) is a 5-item scale that evaluates satisfaction with life. The participants must indicate the extent to which they agree with each statement on a 7-point Likert scale (from 1 = I strongly disagree to 7 = I strongly agree). Scores may range from 5 to 35 points; higher scores indicate greater satisfaction with life. This scale in this study shows high internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.863.

Rosenberg’s Self-esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965 ) is self-applied and contains 10 statements of the feelings that each person feels about him/herself; five in the positive sense (items 1, 2, 4, 6, and 7) and five in the negative sense (items 3, 5, 8, 9, and 10). It is a Likert-type scale whose theoretical values fluctuate between 10 (low self-esteem) and 40 (high self-esteem). The Cronbach’s alpha obtained by this scale is 0.876.

The PANAS schedule (Watson, Clark and Tellegen, 1988 ), this being the positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS), includes 20 items, of which 10 refer to positive affects (PA) and 10 to negative affects (NA) on two Likert-type scales. They all refer to the time the scale is answered (right now), with a score from 0 (not at all emotional) to 5 (extremely emotional). This scale shows an alpha of 0.790 for PA and one of 0.874 for NA.

Data analysis

The statistical analysis was done using version 22.0 of the SPSS software package for Windows. Factorial analyses were done. By reducing data, this technique is used to explain the variability among observed variables in terms of a smaller number of non-observed variables called factors. The observed variables were modeled as linear combinations of factors, plus error expressions. The intention was to analyze the consistency of the scale factors. In this study, a combination of EFA and CFA was performed. The majority of the studies chose the use of EFA for factor analysis. Others used CFA, for specific hypothesized factor structure proposed in EFA. DeVellis ( 2003 ) suggested the combined use of EFA and CFA for more consistent results on the psychometric indices of new scales. Recently, this suggestion of considering the combined use of EFA and CFA during the evaluation of construct validity of new measures has been approved by other authors, in order to provide more consistent psychometric results (Morgado, Meireles, Neves, Amaral and Ferreira, 2017 ).

Confirmatory analyses were run with the AMOS program, v24.0, with the study sample to verify if the factorial structure of the Spanish version matched that in the original version. Following the recommendations by Batista and Coenders ( 2000 ), the maximum likelihood estimation method was used rather than the weighted least squares method given the small sample size and few variables involved. As variables were measured at the ordinal level, estimations were made with polychoric correlations matrices instead of with covariance matrices.

Construct validity