Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Industrial Transformation in the North, 1800–1850

On the Move: The Transportation Revolution

OpenStaxCollege

[latexpage]

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the development of improved methods of nineteenth-century domestic transportation

- Identify the ways in which roads, canals, and railroads impacted Americans’ lives in the nineteenth century

Americans in the early 1800s were a people on the move, as thousands left the eastern coastal states for opportunities in the West. Unlike their predecessors, who traveled by foot or wagon train, these settlers had new transport options. Their trek was made possible by the construction of roads, canals, and railroads, projects that required the funding of the federal government and the states.

New technologies, like the steamship and railroad lines, had brought about what historians call the transportation revolution. States competed for the honor of having the most advanced transport systems. People celebrated the transformation of the wilderness into an orderly world of improvement demonstrating the steady march of progress and the greatness of the republic. In 1817, John C. Calhoun of South Carolina looked to a future of rapid internal improvements, declaring, “Let us . . . bind the Republic together with a perfect system of roads and canals.” Americans agreed that internal transportation routes would promote progress. By the eve of the Civil War, the United States had moved beyond roads and canals to a well-established and extensive system of railroads.

ROADS AND CANALS

One key part of the transportation revolution was the widespread building of roads and turnpikes. In 1811, construction began on the Cumberland Road , a national highway that provided thousands with a route from Maryland to Illinois. The federal government funded this important artery to the West, beginning the creation of a transportation infrastructure for the benefit of settlers and farmers. Other entities built turnpikes, which (as today) charged fees for use. New York State, for instance, chartered turnpike companies that dramatically increased the miles of state roads from one thousand in 1810 to four thousand by 1820. New York led the way in building turnpikes.

Canal mania swept the United States in the first half of the nineteenth century. Promoters knew these artificial rivers could save travelers immense amounts of time and money. Even short waterways, such as the two-and-a-half-mile canal going around the rapids of the Ohio River near Louisville, Kentucky, proved a huge leap forward, in this case by opening a water route from Pittsburgh to New Orleans. The preeminent example was the Erie Canal ( [link] ), which linked the Hudson River, and thus New York City and the Atlantic seaboard, to the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River Valley.

With its central location, large harbor, and access to the hinterland via the Hudson River, New York City already commanded the lion’s share of commerce. Still, the city’s merchants worried about losing ground to their competitors in Philadelphia and Baltimore. Their search for commercial advantage led to the dream of creating a water highway connecting the city’s Hudson River to Lake Erie and markets in the West. The result was the Erie Canal. Chartered in 1817 by the state of New York, the canal took seven years to complete. When it opened in 1825, it dramatically decreased the cost of shipping while reducing the time to travel to the West. Soon $15 million worth of goods (more than $200 million in today’s money) was being transported on the 363-mile waterway every year.

Explore the Erie Canal on ErieCanal.org via an interactive map. Click throughout the map for images of and artifacts from this historic waterway.

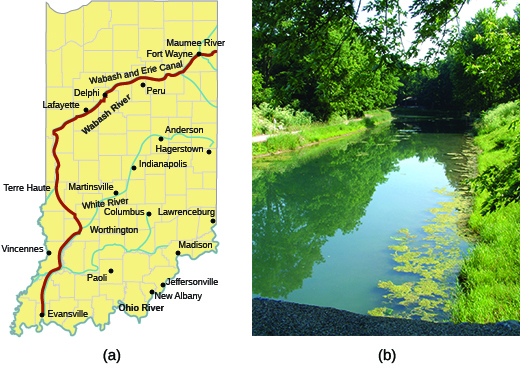

The success of the Erie Canal led to other, similar projects. The Wabash and Erie Canal, which opened in the early 1840s, stretched over 450 miles, making it the longest canal in North America ( [link] ). Canals added immensely to the country’s sense of progress. Indeed, they appeared to be the logical next step in the process of transforming wilderness into civilization.

Visit Southern Indiana Trails to see historic photographs of the Wabash and Erie Canal:

As with highway projects such as the Cumberland Road, many canals were federally sponsored, especially during the presidency of John Quincy Adams in the late 1820s. Adams, along with Secretary of State Henry Clay, championed what was known as the American System, part of which included plans for a broad range of internal transportation improvements. Adams endorsed the creation of roads and canals to facilitate commerce and develop markets for agriculture as well as to advance settlement in the West.

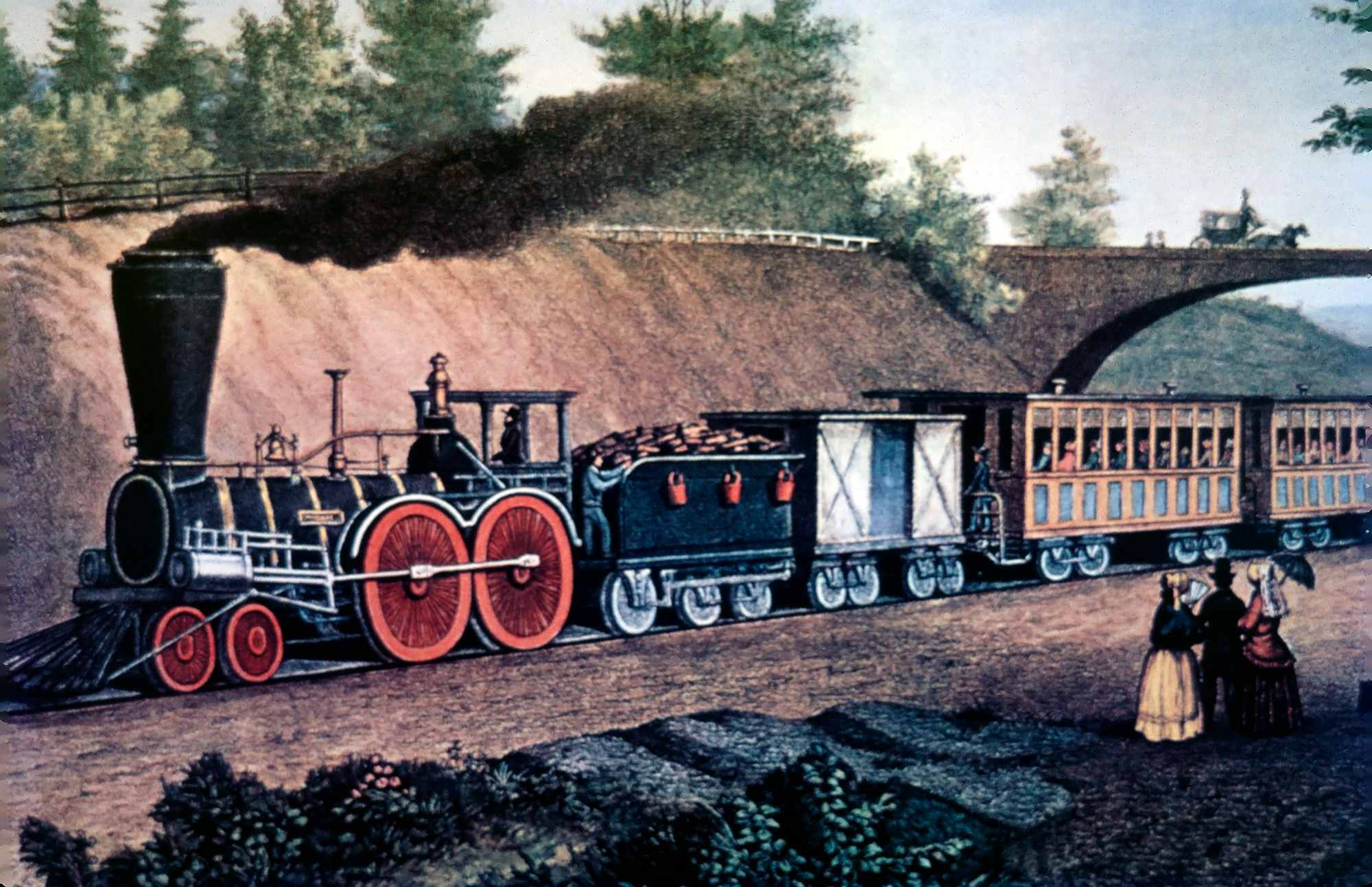

Starting in the late 1820s, steam locomotives began to compete with horse-drawn locomotives. The railroads with steam locomotives offered a new mode of transportation that fascinated citizens, buoying their optimistic view of the possibilities of technological progress. The Mohawk and Hudson Railroad was the first to begin service with a steam locomotive. Its inaugural train ran in 1831 on a track outside Albany and covered twelve miles in twenty-five minutes. Soon it was traveling regularly between Albany and Schenectady.

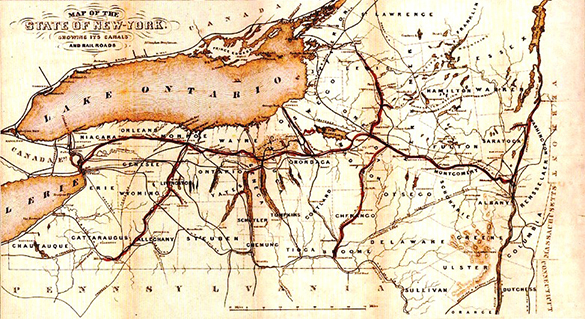

Toward the middle of the century, railroad construction kicked into high gear, and eager investors quickly formed a number of railroad companies. As a railroad grid began to take shape, it stimulated a greater demand for coal, iron, and steel. Soon, both railroads and canals crisscrossed the states ( [link] ), providing a transportation infrastructure that fueled the growth of American commerce. Indeed, the transportation revolution led to development in the coal, iron, and steel industries, providing many Americans with new job opportunities.

AMERICANS ON THE MOVE

The expansion of roads, canals, and railroads changed people’s lives. In 1786, it had taken a minimum of four days to travel from Boston, Massachusetts, to Providence, Rhode Island. By 1840, the trip took half a day on a train. In the twenty-first century, this may seem intolerably slow, but people at the time were amazed by the railroad’s speed. Its average of twenty miles per hour was twice as fast as other available modes of transportation.

By 1840, more than three thousand miles of canals had been dug in the United States, and thirty thousand miles of railroad track had been laid by the beginning of the Civil War. Together with the hundreds of steamboats that plied American rivers, these advances in transportation made it easier and less expensive to ship agricultural products from the West to feed people in eastern cities, and to send manufactured goods from the East to people in the West. Without this ability to transport goods, the market revolution would not have been possible. Rural families also became less isolated as a result of the transportation revolution. Traveling circuses, menageries, peddlers, and itinerant painters could now more easily make their way into rural districts, and people in search of work found cities and mill towns within their reach.

Section Summary

A transportation infrastructure rapidly took shape in the 1800s as American investors and the government began building roads, turnpikes, canals, and railroads. The time required to travel shrank vastly, and people marveled at their ability to conquer great distances, enhancing their sense of the steady advance of progress. The transportation revolution also made it possible to ship agricultural and manufactured goods throughout the country and enabled rural people to travel to towns and cities for employment opportunities.

Review Questions

Which of the following was not a factor in the transportation revolution?

What was the significance of the Cumberland Road?

What were the benefits of the transportation revolution?

The Cumberland Road made transportation to the West easier for new settlers. The Erie Canal facilitated trade with the West by connecting the Hudson River to Lake Erie. Railroads shortened transportation times throughout the country, making it easier and less expensive to move people and goods.

On the Move: The Transportation Revolution Copyright © 2014 by OpenStaxCollege is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

What It Was Really Like To Travel Across The US In The 1800s

One of the things we take completely for granted in the 21st century is the act of being comfortable. If you are driving somewhere, you can open or close your car windows at the push of a button. You can push another button to warm your butt. Add in modern tires, not to mention good (or at least decent) roads, and it all means a painless ride. Sure, there's plenty you could complain about, like traffic jams, potholes, the type of music your passengers are making you listen to, and how you can never adjust the seat to get the lumbar support exactly how you like it.

Well, your ancestors are rolling over in their graves, you ungrateful little – Not only did traveling back in the 1800s take tens or even hundreds of times longer than it does now, but the process of traveling was painful, uncomfortable, and very often deadly. That's right: even though we're talking about covered wagons , slow trains, and bicycles , just about every type of travel would try to kill you. So you'd spend days or weeks being uncomfortable and cold, only to maybe die before you even reached your destination.

But the 1800s was a time of immense progress. In that 100-year period, you went from people dreaming that the Industrial Revolution might make boats a little bit faster, to the first person driving a car across the entire United States. Here's what it was really like to travel across the U.S. in the 1800s.

Wagon trains and the Oregon Trail

It won't be a surprise to anyone who's a millennial that traveling by wagon train, specifically on the Oregon Trail, was a dangerous endeavor. But there was a lot more that could kill you than fording rivers and dysentery. And even if you lived, that didn't mean taking a wagon out west was at all a pleasant experience.

The Oregon Trail Center says Margaret Frink kept a journal when she and her husband traveled to California in search of gold in 1850, and that it's one of the best records we have of the experience. One average day went like this: "We started at six o' clock, forded Thomas Fork, and, turning to the west, came to a high steep spur that extends to the river. Over this high spur we were compelled to climb ... Part of the way I rode on horseback, the rest I walked. The descent was very long and steep. All the wheels of the wagon were tied fast, and it slid along the ground. At one place the men held it back with ropes, and let it down slowly." Two days later, things got worse: "It rained considerably during the night. Mr. Frink was on guard until two o' clock, when he returned to camp bringing the startling news, that for some unknown cause, the horses had stampeded."

Abigail Scott was just a girl when she was put in charge of recording her family's journey out west. One line highlights the harsh realities of the trail: "The mosquitoes are troublesome in the extreme: passed four graves."

The Cumberland Road

In a country where an interstate system of highways has been the reality for almost 100 years, it's easy to forget that means for a century and a half before that there just ... wasn't one. But once the U.S. started claiming and colonizing the West in earnest around the turn of the 19th century, they realized the lack of good roads was an issue. Suddenly people on the East Coast had reason to head west in droves, and they knew the trip would be a million times easier if there was a road.

This meant there was a big push to build said road. Known as the National Road at the time, now the Cumberland Road, it transformed the country completely. According to National Geographic , it was the first road in the new country to be funded by the federal government. Started in 1811, it was a massive undertaking which continued for decades. But as each new section was built, it opened up wide areas of the country to colonizers, allowed easier trade, and laid the literal and figurative groundwork for the eventual highway system we have today.

Even at the time, everyone knew how big a deal the National Road was. Politico reveals that by 1825, the road was so beloved it was "celebrated in song, story, painting and poetry." Can that be said about any other road besides Route 66? After all, even with all the creative types who live in Los Angeles, no one is writing love songs about I-5.

Surely, of all the ways to travel in the 1800s, the steamboat must have been the most pleasant. No beautiful views, nice regular pace, room to walk around on deck. Look how happy Mickey Mouse was in that cartoon! The Mississippi was the backbone of the country, and people traveled up and down it constantly.

One person who spent a lot of time on steamboats on the Mississippi was Mark Twain. His pen name even comes from his time on the river, and he wrote a memoir about his experiences called "Old Times on the Mississippi." In an except ( via the New York Times ), he talked about how his first steamboat experience involved some unexpected issues: "What with lying on the rocks four days at Louisville, and some other delays, the poor old Paul Jones fooled away about two weeks in making the voyage from Cincinnati to New-Orleans."

Not all steamboat trips were on the Mississippi, nor so boring. A student at Oberlin wrote a letter to his family in 1837 telling them about his dramatic journey to the college on a steamboat traveling from Providence to New York: "A sudden and severe gale struck upon us, which for a few minutes, rendered the prospects of life, hopeless. There were three or four hundred on board, I should think, whose lives were all saved by a hair's breadth. – The wind came so sudden & strong, that it tipped the boat up so much that it almost dipped, ... But while it was safety for us, others were overwhelmed in the deep."

Before railroads, canals were going to be the next big thing. And they were the cutting edge of progress; Thomas Jefferson called the proposal for the Erie Canal "little short of madness," according to Eyewitness to History . Once it was finished in 1825, the Erie Canal cut the time it took to get from New York to Chicago in half, plus it was a much smoother ride than a carriage on unpaved roads.

Thomas S. Woodcock took a trip on the Erie Canal in 1836 was amazed at how nice the boat was, even though it looked so small from the outside. But, Tardis-like, somehow the inside was lovely. "These boats are about 70 feet long, and with the exception of the kitchen and bar, is occupied as a cabin ... at mealtimes ... the table is supplied with everything that is necessary and of the best quality with many of the luxuries of life."

Who wouldn't like traveling on a canal boat? Luxurious, calm, good food. And surely nothing could be safer than slowly floating down a canal. Right, Thomas S. Woodcock? You're not going to tell us that horrific deaths occurred on the boats? "The Bridges on the Canal are very low, particularly the old ones. Every bridge makes us bend double if seated on anything, and in many cases you have to lie on your back ... Some serious accidents have happened for want of caution. A young English woman met with her death a short time since, she having fallen asleep with her head upon a box, had her head crushed to pieces."

Early railroads

It cannot be overstated how important the railroad was. But in the year 1800, there were no railroads. Which meant the next 100 years involved inventing and perfecting them, but the bit in between could get a bit messy. Early railroads were not the same as the railroads travelers would enjoy at the turn of the 20th century.

Inventor Oliver Evans famously predicted in 1812, "The time will come when people will travel in stages moved by steam engines from one city to another almost as fast as birds fly – 15 to 20 miles an hour ... A carriage will set out from Washington in the morning, and the passengers will breakfast at Baltimore, dine in Philadelphia, and sup at New York the same day."

The dream began to be realized in 1827, according to the Library of Congress , when the first 13 miles of railroad track opened. The train was still only about as fast as a horse, but it was a start. What was fast was the expansion of the railroads from there. There was big money in it, no government oversight, and ridiculously half-arsed construction. This meant train derailments were common, per American Rails , and people died. Sometimes the floors of the train car would "disintegrate," with deadly results. The trips were also psychologically jarring. Railroads and the Making of Modern America explains how people's very concept of space and time was "annihilated" by the speed of this new way of travel.

Room and board

When you were traveling out west, you usually had to pack light. This meant that most people had to rely on places along the way for a place to sleep and, more importantly, a square meal. Even today stopping at a roadside restaurant while on a road trip is a gamble. Some places will be hidden gems, most ... not so much. While establishments like the St. James Hotel in Red Wing, Minnesota claim on its website today that after it opened in 1875 it was a "regular stop for riverboats and trains alike" and the guests found "modern features, including steam heat, hot and cold running water, and a state of-the-art kitchen," the general rule of stopping for food on your trip west was that it was going to be terrible.

"We found the quality on the whole bad," said traveler William Robertson, according to American Heritage , "and all three meals, breakfast, dinner and supper, were almost identical, viz., tea, buffalo steaks, antelope chops, sweet potatoes, and boiled Indian corn, with hoe cakes and syrup ad nauseam." Another man said things got worse the further west you went, when all you found were restaurants "consisting of miserable shanties, with tables dirty, and waiters not only dirty, but saucy."

But every now and then the traveler struck culinary gold ... or so one group thought. "The passengers were replenished with an excellent breakfast—a chicken stew, as they supposed, but which, as they were afterward informed, consisted of prairie-dogs—a new variety of chickens, without feathers. This information created an unpleasant sensation in sundry delicate stomachs."

Going around Cape Horn

Possibly the main reason so many advances in getting across the country emerged in the 1800s was because the only real viable way of doing it in the first half of the century took an absurdly long time. Basically, you got on a boat and then you didn't get off again for the better part of a year.

Not that the boats didn't look pretty! One observer, writing in "The Annals of the City of San Francisco, June 1852" ( via The Maritime Heritage Project ) described the sight of the boats entering the Bay, "large and beautifully lined marine palaces, often of two thousand tons ... These are like the white-winged masses of cloud that majestically soar upon the summer breeze."

But for those who were on the boats, they were probably more like a never-ending hell. Going from New York to California meant sailing around the very bottom of South America, a.k.a. Cape Horn. To get an idea of how slow this was, according to Stephens & Kenau , "the fastest clipper ship ever launched" was the Flying Cloud and her stats make for depressing reading today. In 1851, the ship "reached San Francisco in a record time of 89 days and 8 hours. The average time for clipper ships being more than 120 days." Three years later the boat beat her own record by a mere 13 hours. Even more shocking, no one else would beat that time for well over a century: not until 1989. And since most people in the 1800s weren't on the Formula 1 car of boats, and even the Flying Cloud ran into major, time-consuming issues on many of her voyages, this was not sustainable.

'An Overland Journey From New York To San Francisco In The Summer Of 1859'

The most logical way to get across the country in a quicker, safer, relatively cheaper fashion seemed to be by rail. But the idea of a transcontinental railroad was almost ludicrous. Take just one of the issues you'd run into: the Rocky freaking Mountains. Considering how new the technology was even in the middle of the century, not everyone was convinced it was possible.

One person who was sure it was worth trying was the founder of the New York Tribune, Horace Greeley. According to Encyclopedia.com , in 1859, he traveled across the country, writing articles about his journey for his newspaper. These were then turned into a book. Greeley wanted people to know all about the western part of the country and how awesome it was, and once they wanted to see it themselves, he'd get what he really wanted: a railroad to make the trip easier. Because Greeley had a tough time of it: a New York Times review of his book explained how "his stagecoach was overturned by buffaloes. His body was racked by boils from riding muleback weeks on end ... Fastidious about food and cleanliness, he had little chance to observe his principles about either westward of the Mississippi."

While the railroad was the most important reason he wanted people to learn about his trip west, there was another vital thing that he believed America needed to get to the frontier ASAP: "The first need of California today is a large influx of intelligent, capable, virtuous women."

The Transcontinental Railroad

While there were plenty of railroads before the Transcontinental railroad, they were a spider web of tracks and companies, mostly relatively localized. The Transcontinental would be different, and would do what it said on the tin: connect one coast to the other with railroad tracks. Technically, track only needed to be laid from Nebraska to California, and in 1869 it was finished. Now people could travel that 2,000 mile stretch in just a matter of days, according to History . Seven years after the Transcontinental railroad was finished, an express train made the journey in 83 hours .

It was not only faster, but impossibly more comfortable. "I had a sofa to myself, with a table and a lamp," wrote one rider ( via American Heritage ). "The sofas are widened and made into beds at night. My berth was three feet three inches wide, and six feet three inches long. It had two windows looking out of the train, a handsome mirror, and was well furnished with bedding and curtains." A reporter from the New York Times wrote it was "not only tolerable but comfortable, and not only comfortable but a perpetual delight. At the end of our journey [we] found ourselves not only wholly free from fatigue, but completely rehabilitated in body and spirits."

Of course, no long journey is perfect. In 1972, one traveler said the train trip "caused more hard words to be spoken than can be erased from the big book for many a day."

Getting across the country by (wo)manpower

One of the most extraordinary journeys that was undertaken during the 1800s wasn't from east to west, and it wasn't undertaken by a man.

An article in the San Francisco Call from May 5, 1896 explained the crazy plan: "Mrs. H. Estby and her daughter, aged 18, leave tomorrow morning to walk to New York City. They are respectable but will 'rough it' as regular tramps and carry no baggage." Respectable women walking alone across town was scandalous, let alone doing something no one had ever tried before. (Although Frank Weaver had made a cross-country trip by bicycle in 1890.) But times were hard, and the women had good reason, since "Mrs. Estby is the mother of eight children, all of whom are living with their father on a ranch near here, except the one going with her. The family is poor, and the ranch is mortgaged. Mrs. Estby, seeing no other way of getting out, concluded to make the journey afoot."

How would walking across the country save the farm? Well, some person or group or company (unfortunately this detail was lost somewhere over the past century, according to Transportation History ) was offering $10,000 to the first woman to accomplish the feat. For seven and a half months, going around 30 miles a day, working along the way to pay for food and board, the mother and daughter made their way to New York ... whereupon the sponsors refused to give them the prize on a technicality, and wouldn't even pay for the women to get home.

The first cross-country car journey was the end of an era

You could argue that in Britain, the 19th century didn't really end until 1901, with the death of Queen Victoria. In America, the key date could be seen as 1903, when the first person crossed the country by car. This signaled a new era, one where the West was no longer wild or out of reach to anyone. The continent had been crossed by foot, wagon, train, and now the newfangled car was added to the list.

H. Nelson Jackson, a doctor, and Sewall K. Crocker, a mechanic, drove from San Francisco to New York City after Jackson's friends said they didn't think it was possible. "The majority opinion expressed was that, save for short distances, the automobile was an unreliable novelty," Jackson would later explain ( via SFGate ). "Everyone pooh-poohed the idea of even attempting such a journey." So the two men and a dog named Bud set off.

While no one today would consider their trek easy, they managed it without major issues in just 63 days. Jackson spent $8,000 on the trip, which was a lot of money back then, but that number does include the cost of the car. Others were inspired, and copycat cross-country trips started by the dozens. The trip "was a pivotal moment in American automotive history ," said Roger White, curator at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. "At the time they made the trip, there was a perception that the American frontier was closed. The Jackson-Crocker trip excited people across the nation. It got people thinking about long-distance highways."

19th Century Transportation Movement

Westward expansion and the growth of the United States during the 19th century sparked a need for a better transportation infrastructure. At the beginning of the century, U.S. citizens and immigrants to the country traveled primarily by horseback or on the rivers. After a while, crude roads were built and then canals. Before long the railroads crisscrossed the country moving people and goods with greater efficiency. This caused distinct regional economies to form and, by the turn of the century, a national economy.

Travel through these technological developments during the 19th Century Transportation Movement with the selected classroom resources.

Human Geography, Social Studies, U.S. History

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 6

- The Gold Rush

- The Homestead Act and the exodusters

- The reservation system

- The Dawes Act

- Chinese immigrants and Mexican Americans in the age of westward expansion

- The Indian Wars and the Battle of the Little Bighorn

- The Ghost Dance and Wounded Knee

Westward expansion: economic development

- Westward expansion: social and cultural development

- The American West

- Land, mining, and improved transportation by rail brought settlers to the American West during the Gilded Age.

- New agricultural machinery allowed farmers to increase crop yields with less labor, but falling prices and rising expenses left them in debt.

- Farmers began to organize in local and regional cooperatives like the Grange and the Farmers’ Alliance to promote their interests.

Who owns the West?

Developing the west.

- (Choice A) Railroads led to the discovery of profitable minerals. A Railroads led to the discovery of profitable minerals.

- (Choice B) Railroads brought more people to the East Coast. B Railroads brought more people to the East Coast.

- (Choice C) Railroads allowed farmers to sell their goods in distant markets. C Railroads allowed farmers to sell their goods in distant markets.

Farmers in an industrial age

The grange and the farmers’ alliance, what do you think.

- The Homestead Act , 1862.

- See OpenStax, The Westward Spirit , U.S. History, OpenStax CNX, 2019.

- See David M. Kennedy and Lizabeth Cohen, The American Pageant: A History of the American People, 15th (AP) Edition, (Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning, 2013), 584-585.

- Kennedy and Cohen, The American Pageant , 512-513.

- See Eric Foner, Give Me Liberty!: An American History, 5th AP Edition (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2016), 593.

- Kennedy and Cohen, The American Pageant , 594-596.

- Kennedy and Cohen, The American Pageant , 596-598.

- See Foner, Give Me Liberty! , 641-643.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Westward Expansion

By: History.com Editors

Updated: September 30, 2019 | Original: December 15, 2009

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson purchased the territory of Louisiana from the French government for $15 million. The Louisiana Purchase stretched from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains and from Canada to New Orleans, and it doubled the size of the United States. To Jefferson, westward expansion was the key to the nation’s health: He believed that a republic depended on an independent, virtuous citizenry for its survival, and that independence and virtue went hand in hand with land ownership, especially the ownership of small farms. (“Those who labor in the earth,” he wrote, “are the chosen people of God.”) In order to provide enough land to sustain this ideal population of virtuous yeomen, the United States would have to continue to expand. The westward expansion of the United States is one of the defining themes of 19th-century American history, but it is not just the story of Jefferson’s expanding “empire of liberty.” On the contrary, as one historian writes, in the six decades after the Louisiana Purchase, westward expansion “very nearly destroy[ed] the republic.”

Manifest Destiny

By 1840, nearly 7 million Americans–40 percent of the nation’s population–lived in the trans-Appalachian West. Following a trail blazed by Lewis and Clark , most of these people had left their homes in the East in search of economic opportunity. Like Thomas Jefferson , many of these pioneers associated westward migration, land ownership and farming with freedom. In Europe, large numbers of factory workers formed a dependent and seemingly permanent working class; by contrast, in the United States, the western frontier offered the possibility of independence and upward mobility for all. In 1843, one thousand pioneers took to the Oregon Trail as part of the “ Great Emigration .”

Did you know? In 1853, the Gadsden Purchase added about 30,000 square miles of Mexican territory to the United States and fixed the boundaries of the “lower 48” where they are today.

In 1845, a journalist named John O’Sullivan put a name to the idea that helped pull many pioneers toward the western frontier. Westward migration was an essential part of the republican project, he argued, and it was Americans’ “ manifest destiny ” to carry the “great experiment of liberty” to the edge of the continent: to “overspread and to possess the whole of the [land] which Providence has given us,” O’Sullivan wrote. The survival of American freedom depended on it.

Westward Expansion and Slavery

Meanwhile, the question of whether or not slavery would be allowed in the new western states shadowed every conversation about the frontier. In 1820, the Missouri Compromise had attempted to resolve this question: It had admitted Missouri to the union as a slave state and Maine as a free state, preserving the fragile balance in Congress. More important, it had stipulated that in the future, slavery would be prohibited north of the southern boundary of Missouri (the 36º30’ parallel) in the rest of the Louisiana Purchase .

However, the Missouri Compromise did not apply to new territories that were not part of the Louisiana Purchase, and so the issue of slavery continued to fester as the nation expanded. The Southern economy grew increasingly dependent on “King Cotton” and the system of forced labor that sustained it. Meanwhile, more and more Northerners came to believed that the expansion of slavery impinged upon their own liberty, both as citizens–the pro-slavery majority in Congress did not seem to represent their interests–and as yeoman farmers. They did not necessarily object to slavery itself, but they resented the way its expansion seemed to interfere with their own economic opportunity.

Westward Expansion and the Mexican War

Despite this sectional conflict, Americans kept on migrating West in the years after the Missouri Compromise was adopted. Thousands of people crossed the Rockies to the Oregon Territory, which belonged to Great Britain, and thousands more moved into the Mexican territories of California , New Mexico and Texas . In 1837, American settlers in Texas joined with their Tejano neighbors (Texans of Spanish origin) and won independence from Mexico. They petitioned to join the United States as a slave state.

This promised to upset the careful balance that the Missouri Compromise had achieved, and the annexation of Texas and other Mexican territories did not become a political priority until the enthusiastically expansionist cotton planter James K. Polk was elected to the presidency in 1844. Thanks to the maneuvering of Polk and his allies, Texas joined the union as a slave state in February 1846; in June, after negotiations with Great Britain, Oregon joined as a free state.

That same month, Polk declared war against Mexico , claiming (falsely) that the Mexican army had “invaded our territory and shed American blood on American soil.” The Mexican-American War proved to be relatively unpopular, in part because many Northerners objected to what they saw as a war to expand the “slaveocracy.” In 1846, Pennsylvania Congressman David Wilmot attached a proviso to a war-appropriations bill declaring that slavery should not be permitted in any part of the Mexican territory that the U.S. might acquire. Wilmot’s measure failed to pass, but it made explicit once again the sectional conflict that haunted the process of westward expansion.

Westward Expansion and the Compromise of 1850

In 1848, the Treaty of Guadelupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican War and added more than 1 million square miles, an area larger than the Louisiana Purchase, to the United States. The acquisition of this land re-opened the question that the Missouri Compromise had ostensibly settled: What would be the status of slavery in new American territories? After two years of increasingly volatile debate over the issue, Kentucky Senator Henry Clay proposed another compromise. It had four parts: first, California would enter the Union as a free state; second, the status of slavery in the rest of the Mexican territory would be decided by the people who lived there; third, the slave trade (but not slavery) would be abolished in Washington , D.C.; and fourth, a new Fugitive Slave Act would enable Southerners to reclaim runaway slaves who had escaped to Northern states where slavery was not allowed.

Bleeding Kansas

But the larger question remained unanswered. In 1854, Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas proposed that two new states, Kansas and Nebraska , be established in the Louisiana Purchase west of Iowa and Missouri. According to the terms of the Missouri Compromise, both new states would prohibit slavery because both were north of the 36º30’ parallel. However, since no Southern legislator would approve a plan that would give more power to “free-soil” Northerners, Douglas came up with a middle ground that he called “popular sovereignty”: letting the settlers of the territories decide for themselves whether their states would be slave or free.

Northerners were outraged: Douglas, in their view, had caved to the demands of the “slaveocracy” at their expense. The battle for Kansas and Nebraska became a battle for the soul of the nation. Emigrants from Northern and Southern states tried to influence the vote. For example, thousands of Missourians flooded into Kansas in 1854 and 1855 to vote (fraudulently) in favor of slavery. “Free-soil” settlers established a rival government, and soon Kansas spiraled into civil war. Hundreds of people died in the fighting that ensued, known as “ Bleeding Kansas .”

A decade later, the civil war in Kansas over the expansion of slavery was followed by a national civil war over the same issue. As Thomas Jefferson had predicted, it was the question of slavery in the West–a place that seemed to be the emblem of American freedom–that proved to be “the knell of the union.”

Access hundreds of hours of historical video, commercial free, with HISTORY Vault . Start your free trial today.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Chapter 9: Industrial Transformation in the North: 1800-1850

On the move: the transportation revolution, learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the development of improved methods of nineteenth-century domestic transportation

- Identify the ways in which roads, canals, and railroads impacted Americans’ lives in the nineteenth century

Americans in the early 1800s were a people on the move, as thousands left the eastern coastal states for opportunities in the West. Unlike their predecessors, who traveled by foot or wagon train, these settlers had new transport options. Their trek was made possible by the construction of roads, canals, and railroads, projects that required the funding of the federal government and the states.

New technologies, like the steamship and railroad lines, had brought about what historians call the transportation revolution. States competed for the honor of having the most advanced transport systems. People celebrated the transformation of the wilderness into an orderly world of improvement demonstrating the steady march of progress and the greatness of the republic. In 1817, John C. Calhoun of South Carolina looked to a future of rapid internal improvements, declaring, “Let us . . . bind the Republic together with a perfect system of roads and canals.” Americans agreed that internal transportation routes would promote progress. By the eve of the Civil War, the United States had moved beyond roads and canals to a well-established and extensive system of railroads.

ROADS AND CANALS

One key part of the transportation revolution was the widespread building of roads and turnpikes. In 1811, construction began on the Cumberland Road , a national highway that provided thousands with a route from Maryland to Illinois. The federal government funded this important artery to the West, beginning the creation of a transportation infrastructure for the benefit of settlers and farmers. Other entities built turnpikes, which (as today) charged fees for use. New York State, for instance, chartered turnpike companies that dramatically increased the miles of state roads from one thousand in 1810 to four thousand by 1820. New York led the way in building turnpikes.

Canal mania swept the United States in the first half of the nineteenth century. Promoters knew these artificial rivers could save travelers immense amounts of time and money. Even short waterways, such as the two-and-a-half-mile canal going around the rapids of the Ohio River near Louisville, Kentucky, proved a huge leap forward, in this case by opening a water route from Pittsburgh to New Orleans. The preeminent example was the Erie Canal , which linked the Hudson River, and thus New York City and the Atlantic seaboard, to the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River Valley.

Although the Erie Canal was primarily used for commerce and trade, in Pittsford on the Erie Canal (1837), George Harvey portrays it in a pastoral, natural setting. Why do you think the painter chose to portray the canal this way?

With its central location, large harbor, and access to the hinterland via the Hudson River, New York City already commanded the lion’s share of commerce. Still, the city’s merchants worried about losing ground to their competitors in Philadelphia and Baltimore. Their search for commercial advantage led to the dream of creating a water highway connecting the city’s Hudson River to Lake Erie and markets in the West. The result was the Erie Canal. Chartered in 1817 by the state of New York, the canal took seven years to complete. When it opened in 1825, it dramatically decreased the cost of shipping while reducing the time to travel to the West. Soon $15 million worth of goods (more than $200 million in today’s money) was being transported on the 363-mile waterway every year.

The success of the Erie Canal led to other, similar projects. The Wabash and Erie Canal, which opened in the early 1840s, stretched over 450 miles, making it the longest canal in North America. Canals added immensely to the country’s sense of progress. Indeed, they appeared to be the logical next step in the process of transforming wilderness into civilization.

This map (a) shows the route taken by the Wabash and Erie Canal through the state of Indiana. The canal began operation in 1843 and boats operated on it until the 1870s. Sections have since been restored, as shown in this 2007 photo (b) from Delphi, Indiana.

As with highway projects such as the Cumberland Road, many canals were federally sponsored, especially during the presidency of John Quincy Adams in the late 1820s. Adams, along with Secretary of State Henry Clay, championed what was known as the American System, part of which included plans for a broad range of internal transportation improvements. Adams endorsed the creation of roads and canals to facilitate commerce and develop markets for agriculture as well as to advance settlement in the West.

Starting in the late 1820s, steam locomotives began to compete with horse-drawn locomotives. The railroads with steam locomotives offered a new mode of transportation that fascinated citizens, buoying their optimistic view of the possibilities of technological progress. The Mohawk and Hudson Railroad was the first to begin service with a steam locomotive. Its inaugural train ran in 1831 on a track outside Albany and covered twelve miles in twenty-five minutes. Soon it was traveling regularly between Albany and Schenectady.

Toward the middle of the century, railroad construction kicked into high gear, and eager investors quickly formed a number of railroad companies. As a railroad grid began to take shape, it stimulated a greater demand for coal, iron, and steel. Soon, both railroads and canals crisscrossed the states, providing a transportation infrastructure that fueled the growth of American commerce. Indeed, the transportation revolution led to development in the coal, iron, and steel industries, providing many Americans with new job opportunities.

This 1853 map of the “Empire State” shows the extent of New York’s canal and railroad networks. The entire country’s transportation infrastructure grew dramatically during the first half of the nineteenth century.

AMERICANS ON THE MOVE

The expansion of roads, canals, and railroads changed people’s lives. In 1786, it had taken a minimum of four days to travel from Boston, Massachusetts, to Providence, Rhode Island. By 1840, the trip took half a day on a train. In the twenty-first century, this may seem intolerably slow, but people at the time were amazed by the railroad’s speed. Its average of twenty miles per hour was twice as fast as other available modes of transportation.

By 1840, more than three thousand miles of canals had been dug in the United States, and thirty thousand miles of railroad track had been laid by the beginning of the Civil War. Together with the hundreds of steamboats that plied American rivers, these advances in transportation made it easier and less expensive to ship agricultural products from the West to feed people in eastern cities, and to send manufactured goods from the East to people in the West. Without this ability to transport goods, the market revolution would not have been possible. Rural families also became less isolated as a result of the transportation revolution. Traveling circuses, menageries, peddlers, and itinerant painters could now more easily make their way into rural districts, and people in search of work found cities and mill towns within their reach.

Section Summary

A transportation infrastructure rapidly took shape in the 1800s as American investors and the government began building roads, turnpikes, canals, and railroads. The time required to travel shrank vastly, and people marveled at their ability to conquer great distances, enhancing their sense of the steady advance of progress. The transportation revolution also made it possible to ship agricultural and manufactured goods throughout the country and enabled rural people to travel to towns and cities for employment opportunities.

Review Question

- What were the benefits of the transportation revolution?

Answer to Review Question

- The Cumberland Road made transportation to the West easier for new settlers. The Erie Canal facilitated trade with the West by connecting the Hudson River to Lake Erie. Railroads shortened transportation times throughout the country, making it easier and less expensive to move people and goods.

Cumberland Road a national highway that provided thousands with a route from Maryland to Illinois

Erie Canal a canal that connected the Hudson River to Lake Erie and markets in the West

Mohawk and Hudson Railroad the first steam-powered locomotive railroad in the United States

- US History. Authored by : P. Scott Corbett, Volker Janssen, John M. Lund, Todd Pfannestiel, Paul Vickery, and Sylvie Waskiewicz. Provided by : OpenStax College. Located at : http://openstaxcollege.org/textbooks/us-history . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/content/col11740/latest/

The Geography of Transport Systems

The spatial organization of transportation and mobility

American Rail Network, 1861

Sources: Railroads and the Making of Modern America, University of Nebraska, Lincoln (Rail Network). US Census Bureau (Urban Population).

In only 30 years after its introduction, the American rail network totaled about 28,900 miles (46,500 km) on the eve of the Civil War (1861-1865). Yet, the American rail network was composed of two systems reflecting the political division between the North (Union States) and the South (Confederate States). Outside a connection through Washington, the networks were disconnected and serviced different economic systems. This lack of connectivity was compounded by the fact that railways servicing the same city were often not connected, requiring ferrying cargo from one terminal to the other and for passengers to spend a night to catch the next day train (schedules were not effectively coordinated).

The dominantly rural society of the South was mainly serviced by penetration lines seeking to connect the agricultural hinterland to ports where surpluses were exported (e.g. New Orleans & Charleston). As such, the network was not very cohesive. The more urbanized North developed a network that interconnected its main urban centers and agricultural regions in the Midwest in a complex lattice. At the end of the Civil War, the expansion of the network would resume, as well as its level of integration.

Share this:

United States Expansion and the Railroads, 1880

4 Routes to the West Used by American Settlers

Roads, Canals, and Trails Led the Way for Western Settlers

Artodidact / Pixabay

- America Moves Westward

- Important Historical Figures

- U.S. Presidents

- Native American History

- American Revolution

- The Gilded Age

- Crimes & Disasters

- The Most Important Inventions of the Industrial Revolution

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/McNamara-headshot-history1800s-5b7422c046e0fb00504dcf97.jpg)

Americans who heeded the call to "go west, young man" may have been proceeding with a great sense of adventure. But in most cases, those trekking to the wide-open spaces were following paths that had already been marked. In some notable cases, the way westward was a road or canal which had been constructed specifically to accommodate settlers.

Before 1800, the mountains to the west of the Atlantic seaboard created a natural obstacle to the interior of the North American continent. And, of course, few people even knew what lands existed beyond those mountains. The Lewis and Clark Expedition in the first decade of the 19th century cleared up some of that confusion. But the enormity of the west was still largely a mystery.

In the early decades of the 1800s, that all began to change as very well-traveled routes were followed by many thousands of settlers.

The Wilderness Road

George Caleb Bingham / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

The Wilderness Road was a path westward to Kentucky established by Daniel Boone and followed by thousands of settlers in the late 1700s and early 1800s. At its beginning, in the early 1770s, it was a road in name only.

Boone and the frontiersmen he supervised managed to link together a route comprising old Indigenous peoples' pathways and trails used for centuries by herds of buffalo. Over time, it was improved and widened to accommodate the wagons and travelers.

The Wilderness Road passed through the Cumberland Gap , a natural opening in the Appalachian mountain range, and became one of the main routes westward. It was in operation decades before other routes to the frontier, such as the National Road and the Erie Canal.

Though Daniel Boone's name has always been associated with the Wilderness Road, he was actually acting in the employ of a land speculator, Judge Richard Henderson. Recognizing the value of vast tracts of land in Kentucky, Henderson had formed the Transylvania Company. The purpose of the business enterprise was to settle thousands of emigrants from the East Coast to the fertile farmlands of Kentucky.

Henderson faced several obstacles, including the aggressive hostility of the Indigenous tribes who were becoming increasingly suspicious of white encroachment on their traditional hunting lands.

And a nagging problem was the shaky legal foundation of the entire endeavor. Legal problems with land ownership thwarted even Daniel Boone, who became embittered and left Kentucky by the end of the 1700s. But his work on the Wilderness Road in the 1770s stands as a remarkable achievement that made westward expansion of the United States possible.

The National Road

Doug Kerr from Albany, NY, United States / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.0

A land route westward was needed in the early 1800s, a fact made evident when Ohio became a state and there was no road that went there. And so the National Road was proposed as the first federal highway.

Construction began in western Maryland in 1811. Workers started building the road going westward, and other work crews began heading east, toward Washington, D.C.

It was eventually possible to take the road from Washington all the way to Indiana. And the road was made to last. Constructed with a new system called "macadam," the road was amazingly durable. Parts of it actually became an early interstate highway.

The Erie Canal

Federal Highway Administration / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Canals had proven their worth in Europe, where cargo and people traveled on them, and some Americans realized that canals could bring great improvement to the United States.

Citizens of New York state invested in a project that was often mocked as folly. But when the Erie Canal opened in 1825, it was considered a marvel.

The canal connected the Hudson River, and New York City, with the Great Lakes. As a simple route into the interior of North America, it carried thousands of settlers westward in the first half of the 19th century.

The canal was such a commercial success that soon, New York was being called "The Empire State."

The Oregon Trail

Albert Bierstadt / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

In the 1840s, the way westward for thousands of settlers was the Oregon Trail, which began in Independence, Missouri.

The Oregon Trail stretched for 2,000 miles. After traversing prairies and the Rocky Mountains, the end of the trail was in the Willamette Valley of Oregon.

While the Oregon Trail became known for westward travel in the mid-1800s, it was actually discovered decades earlier by men traveling eastward. Employees of John Jacob Astor , who had established his fur trading outpost in Oregon, blazed what became known as the Oregon Trail while carrying dispatches back east to Astor's headquarters.

Fort Laramie

MPI/Stringer / Getty Images

Fort Laramie was an important western outpost along the Oregon Trail. For decades, it was an important landmark along the trail. Many thousands of emigrants heading to the west passed by it. Following the years of it being an important landmark for westward travel, it became a valuable military outpost.

The South Pass

BLM Wyoming / Flickr / CC BY 2.0

The South Pass was another very important landmark along the Oregon Trail. It marked the spot where travelers would stop climbing in the high mountains and would begin a long descent to the regions of the Pacific Coast.

The South Pass was assumed to be the eventual route for a transcontinental railroad, but that never happened. The railroad was built farther to the south, and the importance of the South Pass faded.

- The National Road, America's First Major Highway

- Biography of Daniel Boone, Legendary American Frontiersman

- Exploration of the West in the 19th Century

- Albert Gallatin's Report on Roads, Canals, Harbors, and Rivers

- Cumberland Gap

- Manifest Destiny: What It Meant for American Expansion

- Building the Erie Canal

- The Growth of the Early US Economy in the West

- American History Timeline: 1820-1829

- Biography of Kit Carson

- American Indian Removal Policy and the Trail of Tears

- Timeline from 1810 to 1820

- The California Gold Rush

- The Donner Party, Ill-Fated Group of Settlers Headed to California

- Biography of John C. Frémont, Soldier, Explorer, Senator

History of Railroads in the 1800s: The Horse Carriage Trains began as horse-drawn carts or wagons that carried heavy loads. The problem was that even the gravel roads were invariably rough in places. It then occurred to some bright spark that it would be better to lay down flat, wooden rails and then to place a rim on the wagon wheels that would keep the wagons on the rails - the idea of the Horse Car and the rail-road was born. Rails reduced friction and increased efficiency.

History of Railroads in the 1800s: The Rail-Road The first rail-road of this kind in America was built at Boston in 1807. It was a very basic design used to carry soil from the top of a hill to Boston harbor. However the wooden rails soon wore out, and another bright spark had the idea to nail strips of iron on top of the wooden rail-roads. The idea caught on and long lines of railroads of this kind were soon built to carry both passengers and produce.

History of Railroads in the 1800s for kids: The First Railroads The first railroads - literally rail-roads - were built by privately, by companies, towns and states. Any one having horses and wagons with flanged (rimmed) wheels could use the railway on the payment of a small sum of money. The Horse car , and the first railroads they ran on, were developed about the same time as the steam locomotive was invented in the late 1820s.

History of Railroads in the 1800s: The Locomotive T he steamboat had been invented, steam was used to drive boats through the water. Inventors had been looking for ways to use steam to haul wagons and carriages over a railroad and the steam locomotive was invented by George Stephenson.

Railroads in the 1800s: The Early Locomotives The early railroad trains were extremely basic. The cars were little more than stagecoaches with flanged wheels. The cars were secured together with chains, and when the engine started or stopped, there was a terrible clanging, bumping and jolting. The smoke pipe of the engine was very tall and was hinged so that it could be let down when coming to a low bridge or a tunnel. The chimney of a locomotive was called a smoke-stack. The first passenger carriages were extremely uncomfortable, cinders and smoke flew straight into the passengers' faces. But the trains over the railroads went faster than steamboats and quickly became the favored form of transportation. The first steam locomotives were built with fixed wheels, which worked well on straight tracks but not so well in America's mountainous landscape.

● 1814: George Stephenson constructed a locomotive that could pull 30 tons up a hill at 4 mph. Stephenson called his locomotive, the Blutcher. He is considered to be the inventor of the first steam locomotive engine for railways. ● 1825: Colonel John Stevens is considered to be the father of American railroads and designed and built a steam locomotive capable of hauling several passenger cars in Hoboken, New Jersey ● 1828: The first operational locomotive on an American railroad was the Stourbridge Lion. The Lion was built in 1828 and imported from England by Horatio Allen of New York ● 1829: George Stephenson He named his steam locomotive the 'Rocket' ● 1830: In 1830, the Tom Thumb was the first American-built steam locomotive to be operated on a common-carrier railroad. The Tom Thumb was designed and built by Peter Cooper ● 1831: The name of the first locomotive to pull a train of cars over an American railroad was the 1831 Best Friend of Charleston. The Best Friend was designed by E. L. Miller (it operated for 6 months until its boiler exploded) ● 1831: In 1831 Matthias Baldwin established the Baldwin Locomotive Works and established the prototype from which later engines developed ● 1832: In 1832 John Jervis, designed the locomotive called the 'Experiment' which had a swiveling four-wheeled guide truck that could follow the track and enabled locomotives to travel on railways with tighter curves - more suited to mountainous terrain ● 1833: The firm of Robert Stephenson in England constructed the locomotive the "John Bull" for the Camden and Amboy Railroad. The John Bull was one of the first American locomotives to be fitted with a pilot aka the 'cow catcher'. The 'cow-catcher' was the nickname given to the inclined frame in front of a locomotive that pushed obstructions from the track. The pilot aka the 'cow catcher' soon became standard devices on all American locomotives ● 1837: The invention of the Morse Code and the first telegraph line led to telegraph lines being erected alongside the Railroads

● Railroads cut travel time by 90% ● Railroads improved transportation across the U.S. ● Thousands of settlers utilized the Railroads in the 1800s to move west ● New cities and towns emerged along the route of the railways. For additional facts refer to the History of Urbanization in America ● Many industrialist acquired great wealth, the unscrupulous businessmen were referred to as Robber Barons ● It increased trade by providing the means for transporting agricultural products and manufactured goods across the country and to the eastern seaboard for export to Europe ● The construction of the railroads was a feat of U.S. engineering and a source of great national pride to the United States ● The " Underground Railroad " escape route for slaves was also established in 1831 and used railroad terminology for its secret codes ● The Civil War heralded the use of railroads as a Important means of transporting troops and supplies and the wounded in hospital trains. - refer to Civil War Inventions and Technology .

Facts about the Railroads in the 1800s for kids Interesting Facts about the Railroads in the 1800s History are detailed below. The history is told in a series of facts providing a simple method of relating to the expansion of the Railroads in the 1800s. The facts answer the questions of when the expansion of the Railroads in the 1800s, its effects on transportation and its significance to the United States of America.

Railroads in the 1800s Fact 1: In 1830, the rail network consisted of just 30 miles

Railroads in the 1800s Fact 3: Between 1849 and 1858 21,000 miles of railroad were built in the United States

Railroads in the 1800s Fact 5: The US rail network grew from 35,000 miles to a peak of 254,000 miles in 1916.

Railroads in the 1800s Fact 7: The Erie Railroad and the Albany & New York Central connected New York State and New York City with the Great Lakes

Railroads in the 1800s Fact 9: The Tracks were built in a variety of gauges (the distance between the rails) that ranged from 2 and one-half feet to 6 feet.

Railroads in the 1800s Fact 11: Speculators in the 1850s bought land hoping that a railroad would come through an area and they could then resell the land at a much higher price.

Railroads in the 1800s Fact 13: The American Civil War (1861-1865) became the first Important conflict in which railroads played a Important role as both sides used trains to move troops and supplies

Railroads in the 1800s Fact 16: At noon on November 18, 1883 standard time was introduced to the nation by the railroads

Railroads in the 1800s Fact 18: Railroads were faster and cheaper than canals to construct, and they did not freeze over in the winter so became the favored form of transportation

Railroads in the 1800s Fact 20: The railroads were shut down during the great railroad strike of 1894 and the true importance of the railroads was fully realized. The 1916 Adamson Act and the ruling of the Supreme Court established and 8 hour working day for railroad workers

Railroads in the 1800s - President John Quincy Adams Video The article on the Railroads in the 1800s provides an overview of one of the Important innovations of his presidential term in office. For additional info refer to Facts on Industrial Revolution Inventions . The following John Quincy Adams video will give you additional important facts and dates about the political events experienced by the 6th American President whose presidency spanned from March 4, 1825 to March 4, 1829.

Railroads in the 1800s

● Facts about the Railroads in the 1800s for kids and schools ● Facts about the construction of the railroads ● Facts about trains and Railroads in the 1800s ● John Quincy Adams Presidency from March 4, 1825 to March 4, 1829 ● Fast, fun, interesting facts about the Railroads in the 1800s ● Foreign & Domestic policies of President John Quincy Adams ● John Quincy Adams Presidency and the significance of the Railroads in the 1800s for schools, homework, kids and children

- A-R.com Blog

- Industry History

- Fallen Flags

- Tycoons And Barons

- Famous Landmarks

- Streamliners

- Locomotive History

- Steam Locomotives

- Diesel Locomotives

- Electric Locomotives

- Passenger Car Types

- Freight Car Types

- Short Lines

- Rail Maintenance

- Rail Infrastructure

- Travel By Train

- Commuter Rail

- Tourist Train Rides

- Fall Foliage Rides

- Halloween Train Rides

- Christmas Train Rides

- Polar Express Rides

- Dinner Train Rides

- Valentine's Day Train Rides

- Passenger Train Guide

- Interurbans

- Narrow Gauge Railroads

- Logging Lines

- State History

- Stations And Depots

- Railroad Jobs

- Glossary And Terms

- Railroad Stories

- Privacy Policy

- Terms Of Use

- Book Reviews

- Rail History

Railroads In The 1840s, A New Industry Takes Flight

Last revised: June 7, 2023

By: Adam Burns

As 1840 dawned in the United States, railroads remained largely novelty. Watercraft were still the most efficient means of transportation, aided in part by numerous canals (notably the Erie Canal and Pennsylvania's Main Line of Public Works) either in full operation or under construction at that time.

However, having already proved their advantage in speed and year-round operation, railroads were here to stay.

As John Stover points out in his book, " The Routledge Historical Atlas Of The American Railroads ," in 1840 the U.S. contained just under 3,000 miles of track. This number would more than triple by 1850 (9,000+).

Much of it was concentrated in the Northeast/New England although some disconnected lines had opened in the Southeast and as far west as Illinois.

One of the decade's most significant developments was the Pennsylvania Railroad's chartering in 1846, formed by the state legislature to maintain Philadelphia's leverage as a major port city.

By 1850 railroads had blossomed into a unified matrix with lines linking the east coast and Midwest.

The industry's growth led to a significant (and important) auxiliary network of car builders, locomotive manufacturers, and related businesses. In this section we will look briefly at how railroads continued to expand during the 1840s.

Establishing A Network

While the late 1820's and 1830's are widely understood as the founding era of American railroads, the 1840's were also an experimental decade.

During that period engineers and early experts were still under a huge learning curve trying to establish a guide of "best practices" including such things as a standard gauge, efficient coupling system, and car designs.

A few of the more notable advancements occurred in infrastructure. While many early railroads still employed the strap iron rail method (thin sheets of iron fastened to wooden stringers) it was fast being replaced by the solid "T" rail.

In his book, " Railroads Across America: A Celebration Of 150 Years Of Railroading ," author and historian Mike Del Vecchio describes the following regarding this revolutionary invention:

"Legend has it that T-rail was invented by Robert Stevens (the son of Colonel John Stevens). Robert was whittling while traveling to England to purchase rails for the Camden & Amboy, and [stumbled onto] the I- or T-shaped form.

The first boatload of T-rails, 550 pieces, each sixteen feet long, three inches tall and weighing thirty-six pounds per yard, arrived in Philadelphia in May, 1831. "

Sources (Above Table):

- Boyd, Jim. American Freight Train, The. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 2001.

- Schafer, Mike and McBride, Mike. Freight Train Cars. Osceola: MBI Publishing, 1999.

- McCready, Albert L. and Sagle, Lawrence W. (American Heritage). Railroads In The Days Of Steam. Mahwah: Troll Associates, 1960.

- Stover, John. Routledge Historical Atlas of the American Railroads, The. New York: Routledge, 1999.

T-rail held numerous advantages over the strap-iron method:

- Firstly, it was much stronger and could support far greater weight.

- Secondly, it was cheaper (less labor involved)

- Thirdly, could be spiked to a support base, in this case a wooden tie.

Many of the country's first railroads, like the Baltimore & Ohio, used stone ties. The massive blocks were very labor extensive to both transport and install.

By contrast, their wooden counterparts were much lighter while still providing sufficient lateral strength. Finally, ballast (crushed stone) found increasingly widespread use during the 1840s.

Engineers found that it not only reinforced the track but also acted as an excellent drainage system which kept water away from the rails.

With an improving infrastructure and increasing demand, cars and locomotives also needed upgraded. The latter witnessed major advancements through the 1840s and 1850s as America veered away from English designs.

The earliest predecessor of the modern American Locomotive Company was established in Schenectady, New York in 1848 (Schenectady Locomotive Works) while Matthias W. Baldwin, a former jewelry maker, built his first steam locomotive in 1831.

In his book, " Baldwin Locomotives ," Brian Solomon notes it was a small design commissioned by Franklin Peale as a display piece for the Philadelphia Museum.

Baldwin based his locomotive on those used in England's famous Rainhill Trials held in October, 1829.

He continued refining his work and even helped assemble British locomotives shipped to America. In 1832 he manufactured his very first, full-scale locomotive for the Philadelphia, Germantown & Norristown Railroad. It carried a 2-2-0 wheel arrangement and was named Old Ironsides .

Closely based on Robert Stephenson's early 2-2-0 Planet design , it was placed into service on November 23rd that year.

As previously mentioned, early American railroads imported almost everything from England (rails, locomotives, cars, etc.) since that country had a well-established manufacturing center and its products were less expensive. This had changed, however, as America's network became better established.

In his authoritative book, " The American Railroad Freight Car ," author John H. White, Jr. notes that by 1840 most U.S. railroads had further broken from British influence and abandoned the open freight car concept.

Instead, most were closed (aside from flatcars) in an effort to protect ladding (freight) against weather and, in some cases, vandals.

Two-Axle Trucks

It was becoming clear America would surpass its longtime rival in overall tonnage and mileage. To meet growing demand, American railroads shifted to two-axle trucks by 1840.

As Mr. White notes, they offered more than just increased capacity for freight cars; since many railroads had been built cheaply with, in many cases, sharp grades, stiff curves, light rail, and little or no ballast the extra axles offered greater weight distribution.

Perhaps, though, its greatest attribute was its pivoting, free-swiveling design which enabled a car to easily navigate all types of track conditions.

The first four-axle car was placed into service on the Baltimore & Ohio during the winter of 1830/1831 to ship cords of firewood from outlying forests into Baltimore as home heating fuel.

These experimental cars worked exceedingly well and the B&O eventually rostered some 25 of what were dubbed "Trussell Cars" by 1834.

Shortly thereafter the railroad contracted with J. Rupp and H. Schultz for 110, 24-foot boxcars featuring two-axle trucks.

By 1838 the B&O stated it was upgrading all freight cars with two-axle trucks. The concept quickly caught on throughout the industry and by 1850 few two-axle freight cars remained in service.

Passenger cars remained as rudimentary as their freight hauling counterparts.

In many ways, they had seen even fewer advancements during the ten years following the B&O's inauguration of passenger service (Mount Clare to Carrollton Viaduct) on January 7, 1830.

The first railroads relied on cars inspired by stagecoaches, which provided few accommodations and an even rougher ride.

The modern diner, lounge, sleeper, and other popular services which became commonplace by the late 19th century were still decades away. However, advancements in the standard coach were being made.

Soon after the B&O placed its first Trussell Car into service, the company sought an overhaul of its stagecoach-influenced passenger cars.

In his book, " The American Railroad Passenger Car ," author John H. White, Jr. points out that as early as 1828 or 1829 the B&O was visited by Joseph Smith from Philadelphia with a proposal for a rectangular coach of significant length to handle more travelers.

While never actually built it was a radical departure from typical designs.

The idea was later picked up by B&O's treasurer, George Brown, who requested an testbed car based on Smith's idea which would feature double trucks. It was named the Columbus and constructed during the spring of 1831.

Officially placed into service on July 4, 1831 it was initially pulled by horses although steam locomotives had soon taken over these duties by July 13th.

In another first, the B&O also placed the first modern coach into service during 1834. In his excellent book, " The Railroad Passenger Car ," author August Mencken notes it was the work of Ross Winans, featuring a center aisle running longitudinally with seating to each side that carried double-trucks.

While only a prototype all future passenger cars were based from this design (incredibly, one such "Winans Car" remained in regular use on the Tioga Railroad until 1883). As the 1850's dawned, strides were being made in seating capacity but also passenger comfort.

The latter was revolutionized by George Pullman during that decade who recognized a market in pampering travelers.

During the 1840s railroads could still be described as rudimentary with little government jurisdiction. As a result, accidents, injuries, and deaths were common.

The lack of federal authority meant railroads could do whatever they pleased and most refused to work together in the name of competition and greed.

Despite these problems, railroads were the fastest way to travel and by 1850 every state east of the Mississippi, except Florida, could boast at least a few miles of track.

In addition, the now widely recognized 4-4-0 wheel arrangement was developed at this time, credited to Henry R. Campbell in 1839. The so-called "American" type became the most commonly used and best recognized locomotive of the 19th century thanks to its combination of power, speed, and reliability.

Pioneering Locomotives

The Camden & Amboy's John Bull , a pioneering locomotive built by Robert Stephenson & Company and entered service in 1831, was later upgraded by C&A engineers with a lead "bogey" truck.

This feature allowed the locomotive to easily negotiate curves and became a common feature for those wheel arrangements used in main line service.

This included the 4-4-0, which was refined into the late 1800s and early 20th century with arrangements like the 2-8-0, 2-6-0, 2-8-2, 4-6-0, and many others. By the 1840s, the seeds of which became the four major eastern trunk lines (Pennsylvania Railroad, New York Central, Baltimore & Ohio, and Erie) were well established.

What transpired in the 1840s led to an even greater explosion of new construction the following decade. Aside from the tripling of mileage further technological improvements allowed trains to reach the Midwest in a mere two days instead of a month at the 19th century's dawning.

The 1850s would witness railroads breaking across the Mississippi River into Texas while plans were being drawn up for a transcontinental route into California.

The book " Railroads In The Days Of Steam " by Albert L. McCready and Lawrence W. Sagle, notes that in 1835 more than 200 railroads were either proposed or under construction with around 1,000 miles in operation. By 1850, 9,022 miles of railroad were in service which constituted an investment of $372 million.

SteamLocomotive.com

Wes Barris's SteamLocomotive.com is simply the best web resource on the study of steam locomotives.

It is difficult to truly articulate just how much material can be found at this website.

It is quite staggering and a must visit!

© Copyright 2007-2024 American-Rails.com. All written content, photos, and videos copyright American-Rails.com (unless otherwise noted).

Please wait while your request is being verified...

- Today's news

- Reviews and deals

- Climate change

- 2024 election

- Fall allergies

- Health news

- Mental health

- Sexual health

- Family health

- So mini ways

- Unapologetically

- Buying guides

Entertainment

- How to Watch

- My watchlist

- Stock market

- Biden economy

- Personal finance

- Stocks: most active

- Stocks: gainers

- Stocks: losers

- Trending tickers

- World indices

- US Treasury bonds

- Top mutual funds

- Highest open interest

- Highest implied volatility

- Currency converter

- Basic materials

- Communication services

- Consumer cyclical

- Consumer defensive

- Financial services

- Industrials

- Real estate

- Mutual funds

- Credit cards

- Credit card rates

- Balance transfer credit cards

- Business credit cards

- Cash back credit cards

- Rewards credit cards

- Travel credit cards

- Checking accounts

- Online checking accounts

- High-yield savings accounts