Return visit audits, quality improvement infrastructure, and a culture of safety: a theoretical model and practical assessment tool

- Open access

- Published: 15 June 2023

- Volume 25 , pages 649–652, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Jesse T. T. McLaren ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6310-4988 1 , 2 , 4 ,

- Tahara D. Bhate 1 , 2 ,

- Ahmed K. Taher 1 , 3 &

- Lucas B. Chartier 1 , 3

950 Accesses

5 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Return visit reviews have been a longstanding method of identifying emergency department (ED) adverse events and other quality issues, but the evolving culture of safety has shifted their focus: while the traditional view of “bouncebacks” reflected retrospective judgement on individual errors, “return visits” emphasize root-cause analysis and prospective change [ 1 ]. The field of quality improvement and patient safety (QIPS) within emergency medicine has developed significantly, but there is unevenness across national settings with gaps in infrastructure, training, and capacity [ 2 ].

Here, we describe our past 5 years of experience with QIPS from the local to the national level, and propose a theoretical model for understanding the interaction of safety culture, quality improvement (QI) infrastructure, and return visit audits. This forms the basis of an assessment tool, which should be helpful to EDs of any size in identifying next steps in their QIPS journey through the catalyst of return visit audits.

A theoretical model for assessment and growth

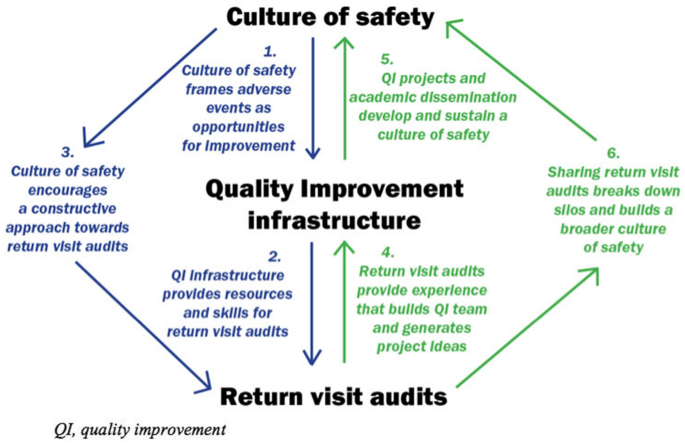

Healthcare QI strategies have often been described as “top-down” or “bottom-up”, with the former providing central coordination and resourcing, while the latter captures the ideas and commitment of frontline providers. However, this dichotomy fails to capture the complex relationships between safety culture, QI infrastructure, and return visit audits. Figure 1 provides a theoretical model for assessment and growth, including a combination of “top-down” interactions (the left half, in blue), and “bottom-up” interactions (the right-half, in green). These are not hierarchical or unidirectional, but cyclical and dynamic: each component is mutually dependent on the others, and each can be harnessed to bolster the others.

Theoretical model for mutual interactions between culture of safety, QI infrastructure and return visit audits

Culture of safety frames adverse events as opportunities for improvement.

A positive safety culture frames adverse events as opportunities for improvement, which encourages the growth of QIPS infrastructure. This varies widely: an environmental scan of emergency medicine academic centers across Canada found that 91% had developed QIPS committees but only 27.3% had administrative support and two-thirds had two or less physicians trained in QI [ 2 ]. Our center, the University Health Network (UHN), has a QIPS committee that includes more than 50 inter-professional team members—a dozen of whom are formally trained in QIPS. This partly reflects our resources as a tertiary academic center, but also reflects the deliberate application of safety culture: 7 years ago, we relaunched our QIPS committee, following a blueprint that can be replicated in other types of centers [ 3 ]. Analysis of return visits is one means by which a department can screen for and identify adverse events and other quality issues, in turn motivating QIPS infrastructure development.

Quality improvement infrastructure provides resources and skills for return visit audits.

QIPS infrastructure, both provincially and locally, influences the capacity for formal return visit audits. In 2016, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term care launched the ED Return Visit Quality Program (RVQP), mandating large hospitals (those 70 + hospitals with > 30,000 visits/year) to review ED return visits resulting in hospital admission. The RVQP is based on safety culture [ 4 ]: the goal is not to reduce return visits but to promote quality improvement. While there is no direct funding, the program provides return visit audit templates to identify root causes (patient factors, provider factors, and system factors). In its first 3 years, 86 hospitals conducted 12,852 return visit audits, uncovering 3,010 adverse events or quality issues, leading to hundreds of QIPS projects [ 5 ]. However, the quantity of chart audits ranged from a few to all return visits, and the quality ranged from a few sentences to full root-cause analyses. Further qualitative analysis found that this variation reflected pre-existing QIPS infrastructure, training, and support [ 6 ].

Leveraging our departmental QIPS committee, we have developed an enhanced version of the RVQP. Our ED QI coordinator (research coordinator who also assists in the QI committee activities) sends out cases of return visits resulting in admission (automatically flagged by our electronic medical record), both to primary reviewers to analyze their own cases as well as to secondary reviewers (uninvolved physicians) with QI interest (whether formally trained or not). Unscheduled return visits are then analyzed with a root-cause analysis framework (patient/ provider/ system factors), in addition to other relevant elements, including ED overcrowding and social determinants of health. Reviewers are encouraged to think about QIPS interventions, which are then reviewed by the ED QI leads and QIPS committee for action (see appendix 1 for our return visit template).

Culture of safety encourages a constructive approach toward return visit audits.

The qualitative analysis of the Ontario RVQP revealed variations in local safety culture, which impacted the methods of analysis and the resulting attitude of frontline providers [ 6 ]. A centralized approach, where the ED medical director or manager completed the audits on behalf of the physician group, led to apprehension from frontline providers regarding what was perceived as performance reviews, due to historic medico-legal or punitive approaches to chart audits. Conversely, we and other centers use a distributed approach where every physician audits their own charts, with emphasis from ED leadership on identifying QI opportunities for the department as a whole. As a result, while our audits found that only 21% of return visits experienced an adverse event, with only 12% were attributed to cognitive lapses, 67% of audits were rated as useful by those completing them.

If only the left side of the model diagram were true, then ED return visit audits would be constrained by pre-existing QIPS culture and infrastructure. Fortunately, the engagement of frontline providers with return visit audits also feeds back into the development of QIPS capacity and a culture of safety, which is particularly relevant for centers without pre-existing QIPS infrastructure. EDs can use a variety of tools to build QIPS infrastructure and a culture of safety, but return visits are a shared experience for every provider in every ED, so audits are an important tool for EDs of any size.

Return visit audits provide experience that builds QI team and generates project ideas.

Return visit audits not only uncover safety issues and other QI learnings, but they can be part of building the QIPS infrastructure to address them [ 3 , 7 ]: enlisting frontline providers to identify local priorities, highlighting patient stories to create a sense of urgency, and adapting interventions to the local context. A number of our QI projects have been motivated by return visit audits and helped build QIPS infrastructure, including: a protocol for repeating vital signs on discharge, a physician handover tool to improve transition of information and accountability, evidence-based order sets in response to return visits for alcohol withdrawal or undertreated sickle cell crises, and rapid follow-up clinics for addiction medicine or COVID. Anyone in our department is welcome to lead QI projects of their choosing, with the support of our QI committee (see our blueprint [ 3 ] for more project examples). A resident-driven model for return visit audits could also build up future QIPS infrastructure by training the next generation in QIPS methodology [ 8 ].

QI projects and academic dissemination develop and sustain a culture of safety.

QI projects can promote a culture of safety through their outcomes, but it is also important to consider their process. For example, a comparative study found that a smaller county hospital experienced greater improvement in safety culture than a larger university hospital, because the former had initiatives driven from the “bottom-up” by frontline physicians whereas the latter was “top-down” with little engagement31. In other words, larger academic centers need to be mindful they are not taking the initiative from frontline providers, and smaller community centers do not need large committees to improve patient safety [ 9 ].

This is where return visit audits play a crucial role—enlisting frontline staff in both identifying quality issues and designing solutions, both of which are important for improving safety culture. Many of our QIPS interventions have been shared through multiple publications [ 3 ] contributing to the science of QIPS and sustaining a culture of safety through academic dissemination, and a website to share articles and projects about Health informatics, Quality improvement and Patient safety (HiQuiPs; www.hiquips.com ).

Sharing return visit audits breaks down silos and builds a broader culture of safety.

Return visit audits can promote a local safety culture, but these lessons are often not shared outside the department—a remnant of a medico-legal approach to safety issues that keeps EDs operating in their own silos. This can reinforce a divide between larger academic hospitals with QI infrastructure and smaller community hospitals without them.

We have developed and collaborated in novel strategies to break down these barriers. At the city-wide level, we collaborated with the Hospital for Sick Children on the development of routine audits [ 10 ], and with QIPS physician leads across the region (in both academic and community hospitals) to launch an Emergency Medicine Quality Improvement Digest [ 11 ]. At the provincial level, we have contributed to provincial webinars organized by Health Quality Ontario to share lessons to EDs across the province on how they can use their own return visits to build a culture of safety. At the national level, we have launched a new podcast on return visits and QIPS on the website Emergency Medicine Cases ( emergencymedicinecases.com ) targeted to all ED providers, irrespective of formal QIPS training.

A practical assessment tool

Drawing from the above theoretical model, we have developed a practical assessment tool for any ED to assess their local strengths, limitations, and opportunities for QIPS growth, through the catalyst of return visit audits. Below are six questions progressing sequentially through the “top-down” and “bottom-up” sides of the model.

What is the current safety culture, and how can it be leveraged to expand QI infrastructure? For example, the ED Medical Director could support development of local QIPS infrastructure, including a QIPS Committee [ 3 ].

What is the current QI infrastructure and how can it support return visit audits, both quantitatively and qualitatively? For example, the QIPS committee could provide a return visit template and share skills with frontline providers to support return visit audits [ 5 ].

How is safety culture influencing return visits, and can this be improved? For example, using distributive methods and emphasizing system-wide quality improvement instead of individual performance [ 6 ].

How can return visit audits be used to train frontline providers in QI methodology, develop their skills, and build local QIPS infrastructure? For example, establish a formal QI team, train secondary reviewers, and formalize change ideas into specific QI projects [ 3 , 8 ].

How can QI projects be used to develop and sustain a culture of safety? For example, use QI projects in conjunction with formal departmental support to increase visibility and uptake of local QIPS projects, and to share more broadly though academic dissemination [ 3 ].

How can sharing return visit audits break down silos and build a broader culture of safety? For example, collaborate with other EDs or hospital departments to break down silos and normalize the discussion of return visits [ 10 ].

Chartier LB. What’s in a name? ‘return visits’ in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2022;29(7):914–5.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Kwok ESH, Perry JJ, Mondoux S, et al. An environmental scan of quality improvement and patient safety activities in emergency medicine in Canada. CJEM. 2019;21(4):535–41.

Chartier LB, Masood S, Choi J, et al. A blueprint for building an emergency medicine quality improvement and patient safety committee. CJEM. 2022;24(2):195–205.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Calder L, Pozgay A, Riff S, et al. Adverse events in patients with return emergency department visits. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(2):142–8.

Chartier LB, Ovens H, Hayes E, et al. Improving quality of care through a mandatory provincial audit program: Ontario’s emergency department return visit quality program. Ann Emerg Med. 2021;77(2):193–202.

Chartier LB, Jalali H, Seaton MB, et al. Qualitative evaluation of a mandatory programme auditing emergency department return visits. BMJ Open. 2021;11(4): e044218.

Chartier LB, Mondoux SE, Stang AS, et al. How do emergency departments and emergency leaders catalyze positive change through quality improvement collaborations. CJEM. 2019;21(4):542–9.

Shy BD, Shapiro JS, Shearer PL, et al. A conceptual framework for improved analysis of 72-hour return cases. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(1):104–7.

Burström L, Letterstål A, Engström M, et al. The patient safety culture as perceived by staff at two different emergency departments before and after introducing a flow-oriented working model with team triage and lean principles: a repeated cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:296.

Ostrow O, Zelinka A, Shim A, et al. Pediatric emergency department return visits: an innovative and systematic approach to promote quality improvement and patient safety. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020;36(12):e726–31.

McLaren JTT, Chartier LB, Shelton D, et al. Sustaining a shared culture of safety: the emergency medicine quality improvement digest. CJEM. 2022;24(Suppl 1):S1–100.

Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Emergency Department, University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada

Jesse T. T. McLaren, Tahara D. Bhate, Ahmed K. Taher & Lucas B. Chartier

Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Jesse T. T. McLaren & Tahara D. Bhate

Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Ahmed K. Taher & Lucas B. Chartier

Toronto General Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada

Jesse T. T. McLaren

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

JTTM and LBC contributed to the development of the concept, wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, provided critical revisions, and approved the final version. TDB and AKT contributed to the development of the concept, provided critical revisions to the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jesse T. T. McLaren .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

All authors report no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 15 KB)

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

McLaren, J.T.T., Bhate, T.D., Taher, A.K. et al. Return visit audits, quality improvement infrastructure, and a culture of safety: a theoretical model and practical assessment tool. Can J Emerg Med 25 , 649–652 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-023-00539-6

Download citation

Received : 02 February 2023

Accepted : 28 May 2023

Published : 15 June 2023

Issue Date : August 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-023-00539-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Return visit

- Quality improvement

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Application of the Informatics Stack framework to describe a population-level emergency department return visit continuous quality improvement program

Affiliations.

- 1 Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States.

- 3 Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; University Health Network, Toronto, Canada.

- 4 Division of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Department of Paediatrics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada.

- 5 Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; Sinai Health System, Toronto, Canada.

- 6 Health Quality Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

- 7 Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; ICES, Toronto, Canada.

- PMID: 31739223

- DOI: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.07.016

Introduction: Population health programs are increasingly reliant on Health Information Technology (HIT). Program HIT architecture description is a necessary step prior to evaluation. Several sociotechnical frameworks have been used previously with HIT programs. The Informatics Stack is a novel framework that provides a thorough description of HIT program architecture. The Emergency Department Return Visit Quality Program (EDRVQP) is a population-level continuous quality improvement (QI) program connecting EDs across Ontario. The objectives of the study were to utilize the Informatics Stack to provide a description of the EDRVQP HIT architecture and to delineate population health program factors that are enablers or barriers.

Materials and methods: The Informatics Stack was used to describe the HIT architecture. A qualitative study was completed with semi-structured interviews of key informants across stakeholder organizations. Emergency departments were selected randomly. Purposive sampling identified key informants. Interviews were conducted until saturation. An inductive qualitative analysis using grounded theory was completed. A literature review of peer-reviewed background literature, and stakeholder organization reports was also conducted.

Results: 23 business actors from 15 organizations were interviewed. The EDRVQP architecture description is presented across the Informatics Stack levels. The levels from most comprehensive to most basic are world, organization, perspectives/roles, goals/functions, workflow/behaviour/adoption, information systems, modules, data/information/knowledge/wisdom/algorithms, and technology. Enabling factors were the high rate of electronic health record adoption, legislative mandate for data collection, use of functional data standards, implementation flexibility, leveraging validated algorithms, and leveraging existing local health networks. Barriers were privacy legislation and a high turn-around time.

Discussion: The Informatics Stack provides a robust approach to thoroughly describe the HIT architecture of population health programs prior to program replication. The EDRVQP is a population health program that illustrates the pragmatic use of continuous QI methodology across a population (provincial) level.

Keywords: Emergency department; Information technology; Patient safety; Public health informatics; Quality improvement.

Copyright © 2019 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

- Data Collection

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Service, Hospital*

- Medical Informatics

- Qualitative Research

- Quality Improvement*

Status message

Moscow office.

1350 Troy Highway Moscow , ID 83843 United States

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- West J Emerg Med

- v.22(5); 2021 Sep

Inpatient Outcomes Following a Return Visit to the Emergency Department: A Nationwide Cohort Study

Chu-lin tsai.

* National Taiwan University Hospital, Department of Emergency Medicine, Taipei, Taiwan

† National Taiwan University Hospital, College of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Taipei, Taiwan

Dean-An Ling

Tsung-chien lu, jasper chia-cheng lin, chien-hua huang, cheng-chung fang, introduction.

Emergency department (ED) revisits are traditionally used to measure potential lapses in emergency care. However, recent studies on in-hospital outcomes following ED revisits have begun to challenge this notion. We aimed to examine inpatient outcomes and resource use among patients who were hospitalized following a return visit to the ED using a national database.

This was a retrospective cohort study using the National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan. One-third of ED visits from 2012–2013 were randomly selected and their subsequent hospitalizations included. We analyzed the inpatient outcomes (mortality and intensive care unit [ICU] admission) and resource use (length of stay [LOS] and costs). Comparisons were made between patients who were hospitalized after a return visit to the ED and those who were hospitalized during the index ED visit.

Of the 3,019,416 index ED visits, 477,326 patients (16%) were directly admitted to the hospital. Among the 2,504,972 patients who were discharged during the index ED visit, 229,059 (9.1%) returned to the ED within three days. Of them, 37,118 (16%) were hospitalized. In multivariable analyses, the inpatient mortality rates and hospital LOS were similar between the two groups. Compared with the direct-admission group, the return-admission group had a lower ICU admission rate (adjusted odds ratio, 0.78; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.72–0.84), and lower costs (adjusted difference, −5,198 New Taiwan dollars, 95% CI, −6,224 to −4,172).

Patients who were hospitalized after a return visit to the ED had a lower ICU admission rate and lower costs, compared to those who were directly admitted. Our findings suggest that ED revisits do not necessarily translate to poor initial care and that subsequent inpatient outcomes should also be considered for better assessment.

INTRODUCTION

Return emergency department (ED) visits pose a significant burden on both patients and healthcare providers, with approximately 5–10% of the patients returning to the ED within three days. 1 – 4 Return ED visits are not only burdensome but costly, as one study found that the total cost of return ED visits was even higher than the total cost of all initial visits. 1 Due to its clinical and economic ramifications, the rate of ED revisit has been used to measure potential lapses in initial emergency care. 5 Recent studies, however, have begun to challenge this conventional wisdom. While the ED revisit rate is easy to measure, many factors may come into play, including factors related to the patient, the illness, the system, and finally to the clinician. 6

It is estimated that only 5–10% of return ED visits are associated with potential deficiencies in care. 7 – 10 More recent studies have examined patient outcomes after return ED visits as an alternative quality metric, such as hospitalization rates after ED revisits 11 – 16 or even inpatient outcomes during the hospitalization after an ED revisit. 17 , 18 Hospitalization rates after an ED revisit may also be problematic because ED admission rates per se are highly variable across EDs. 19 Moreover, if the subsequent hospitalization after an ED revisit did not result in worse inpatient clinical outcomes due to a delay in admission, the assumption of poor care at the initial ED visit may be questionable.

Few studies to date (one of which focused on adults) have investigated inpatient outcomes among patients hospitalized during a return ED visit. 17 , 18 , 20 The study with an adult cohort used data from two large, US states and found that patients who were admitted during an ED revisit had lower in-hospital mortality and intensive care unit (ICU) admission rates, compared with those who were admitted during the initial ED visit. 17 To date, no studies have used nationwide data to address this issue. In the current study, we used nationwide data from a universal healthcare system to examine this topic. We investigated the patient characteristics, inpatient clinical outcomes, and resource use among patients who were admitted following a return visit to the ED, compared to those who were directly admitted during the index ED visit. We hypothesized that patients who were admitted after a revisit to the ED would experience similar inpatient outcomes and use similar inpatient resources.

Study Design and Setting

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) in Taiwan. The NHIRD contains all medical claims records from all clinical care settings covered by the National Health Insurance (NHI) program. The NHI is a mandatory, single-payer, government-run health insurance program that provides comprehensive health insurance to more than 99% of the 23 million Taiwanese residents. 21 The NHIRD, maintained by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, has recorded comprehensive claims data in the NHI since 2000, including patient demographics, diagnoses, examinations, procedures, medications, and costs. 22 The NHIRD is de-identified but contains a unique, encrypted personal identifier that allows researchers to link claims between outpatient, ED, and inpatient databases. We received a waiver for this analysis from our institutional review board.

Study Population

We retrieved data from the registry of beneficiaries for the time period January 1, 2012–December 31, 2013. The sample for the current analysis contained approximately one-third of ED records, which were randomly extracted from the NHIRD via simple random sampling during the study period, including records of patients for their subsequent hospitalizations. This was the maximum amount of the data that could be requested. We excluded ED visits made by patients younger than 18 years, visits to urgent care clinics, ED transfers, or visits with unclear or missing time information.

Population Health Research Capsule

What do we already know about this issue?

Emergency department (ED) revisits are used to measure potential lapses in emergency care. However, in-hospital outcomes are seldom examined after an ED revisit .

What was the research question?

We aimed to examine inpatient outcomes and resource use among patients hospitalized following a return visit to the ED .

What was the major finding of the study?

Patients hospitalized after an ED revisit had a lower ICU admission rate and incurred lower costs, compared to those directly admitted after the index ED visit .

How does this improve population health?

Revisits to the ED do not necessarily translate to poor initial care. Subsequent inpatient outcomes should also be considered for better assessment .

We defined an index ED visit as an ED visit without a prior visit or hospitalization during the preceding three days. A return visit was defined as an ED revisit within 72 hours after discharge from the index ED. For multiple revisits within 72 hours, we selected only the first revisit. The unit of analysis was the visit, and one patient could have had multiple index visits during the study period. We chose to investigate early rather than late revisits because early revisits/readmissions have been shown to be more preventable and amenable to hospital-based interventions. 23 We divided the cohort into two groups for comparison depending on the timing of hospitalization: (1) direct admissions, ie, patients who were admitted to the hospital during the index visit; and (2) return admissions, ie, those who were discharged from the ED at the index visit and were later hospitalized during the return visit to the ED.

The NHIRD contains information on patient demographics, visit date and time, triage level, diagnostic codes ( International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM]), procedures, medications, ED disposition, hospital length of stay (LOS), and hospital disposition. We grouped the primary diagnosis field of ED and inpatient discharges into clinically meaningful categories using the ICD’s Clinical Classification Software. 24 Comorbidities were also derived based on the ICD-9 codes using the Elixhauser Comorbidity index. This risk-adjustment tool has been validated extensively. 25

In Taiwan, hospitals are classified into three distinct levels of accreditation according to the Joint Commission of Taiwan, including academic medical centers, regional hospitals, and community hospitals. The Taiwan Triage and Acuity Scales system is a computerized, five-level system with acuity levels 1 to 5 indicating resuscitation, emergent, urgent, less urgent, and non-urgent, respectively. 26 The “untriaged” situation occurred in some of the psychiatric visits to community hospitals. The time of ED visit was classified as daytime (8 am – 4 pm), evening (4 pm – midnight), and night-time (12 am – 8 am).

Outcome Measures

The outcome measures were inpatient mortality, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, LOS, and total inpatient costs in NT$ (New Taiwan dollar). We also examined the most common hospital discharge diagnoses among the two admission groups.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics are presented as proportions (with 95% confidence intervals [CI]), means (with standard deviations), or medians (with interquartile ranges). We examined bivariate associations using Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney tests, and chi-square tests, as appropriate. The inpatient outcomes (mortality and ICU admission) and resource use (LOS and cost) were analyzed by comparing the direct-admission group with the return-admission group. We used multivariable logistic and linear regression models to adjust for differences in patient mix. Although LOS and cost data were skewed, we did not transform the data because parametric methods are robust to non-normality with large samples. 27 Instead, the associated multivariable linear-regression models were bootstrapped 1000 times to obtain the bias-corrected CIs. 28 Potential confounding factors included age, gender, and Elixhauser comorbidities. All odds ratios (OR) and beta-coefficients are presented with 95% CIs. We performed all analyses using Stata 16.0 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX). All P values are two-sided, with P <0.05 considered statistically significant.

After applying the exclusion criteria, there were 3,019,416 index ED visits during the two-year study period ( Figure 1 ). Of them, 477,326 patients (16%) were admitted to the hospital following the index ED visit. Among the 2,504,972 ED discharges, 229,059 returned to the ED within three days. Of them, 37,118 (16%) were admitted to the hospital.

Flow diagram of the patient selection process.

ED , emergency department; y , years old; ED , emergency department.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the two hospitalization groups stratified by ED revisit status. Compared with the direct-admission group, patients in the return-admission group were slightly younger, predominantly male, and more likely to be triaged at a lower level (ie, less urgent). When revisiting the ED, the patients in the return-admission group were more likely to “move up” to regional hospitals or academic medical centers and were slightly more likely to show up at night, compared with the direct-admission group. In terms of revisit characteristics, most revisits occurred on day 1 after discharge, with a median time to revisit of 23 hours. Within the return-admission group, the triage levels went up upon revisit, compared with those at the index visits. However, the triage levels upon revisit in the return-admission group still appeared to be lower than those in the direct-admission group. Concerning comorbidities, in general, the return-admission group had fewer comorbid conditions, such as diabetes, hypertension, and congestive heart failure, compared with the direct-admission group. Of note, slightly more alcohol abuse and depression were present in the return-admission group.

Characteristics of hospitalizations stratified by revisit status.

IQR , interquartile range; ED , emergency department; SD , standard deviation.

Table 2 lists the hospital discharge diagnosis by ED visit status. The most common discharge diagnoses were quite similar between the two groups. Table 3 shows the study outcomes by ED revisit status. Compared with the direct-admission group, the return-admission group had lower inpatient mortality, a lower ICU admission rate, a shorter LOS, and incurred lower costs. Table 4 shows the study outcomes by ED visit status, after adjusting for age, gender, and 29 comorbidities. The differences in inpatient mortality and length of hospital stay became statistically non-significant between the two groups, while the return-admission group still had a lower ICU admission rate (adjusted OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.72–0.84), and incurred lower costs (adjusted difference, −5,198 NT$, 95% CI, −6,224 to −4,172).

Most common hospitalization diagnoses by revisit status.

Study outcomes by revisit status (unadjusted).

IQR , interquartile range; SD , standard deviation; ICU , intensive care unit, NT$ , New Taiwan dollar.

Study outcomes by revisit status, adjusted.

CI , confidence interval; OR , odds ratio; ICU , intensive care unit; NT$ , New Taiwan dollar.

In this national ED and inpatient sample of 3,019,416 visits in Taiwan, we found that patients who were hospitalized after a return visit to the ED had a lower ICU admission rate and incurred lower costs, compared to those who were directly admitted during the index ED visit. Our data suggest that ED return admission does not necessarily reflect deficiencies in the initial ED care. Instead, because some clinical outcomes were better in the return-admission group than those in the direct-admission group, the clinicians at the initial ED encounter may have done what they were supposed to do, striking a balance between admitting sicker patients and safely discharging less-sick patients.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies that reported a less-ill revisit cohort compared with those without a prior ED visit. 17 , 29 Both studies indicated that patients who returned to the ED were more likely to be uninsured, had fewer comorbidities, lower triage acuity, and similar or lower hospital admission rates. 17 , 29 Our study extends these findings to a non-US population with universal health insurance coverage, suggesting these findings were not likely to be explained by lack of insurance alone. Given universal coverage, patients may choose to return to the ED for a quick assessment instead of scheduled outpatient follow-up. Of note, it is estimated that one-third of the revisits occurred at a different ED. 1 , 4 Our study included both same- and different-hospital revisits in the entire nation, which may increase the likelihood of capturing more revisits and frequent ED users who may prefer the ED as a site of care. 30 , 31 Despite the suggestion that some revisit patients appeared less ill, they might still prefer hospitalization as demonstrated by the similar hospitalization rates between the two groups. Again, this may reflect a shared decision-making process between patients and providers, which adds to the variation of revisit admission rates, undermining its validity as a quality metric. 19

As EDs worldwide are seeing more and sicker patients, emergency physicians must make an appropriate decision to admit patients who are most likely to benefit from inpatient resources. After prioritizing patients, some will be sent home with certain risks of treatment failure, for example, prescribing antibiotics for pneumonia with outpatient follow-up. As shown in our data, although revisit patients had a higher acuity level compared with their prior visits, 32 the revisit acuity was still lower than those who were admitted in the first place, suggesting a small and reasonable fraction of outpatient treatment failure. Furthermore, the lower ICU admission rates among the revisits did not suggest a harmful effect resulting from the decision to discharge at the index ED visits.

Consistent with a previous US study, 17 we also found lower rates of ICU admission and costs among patients who returned to the ED, compared to those without a prior visit. Some of the mortality and LOS benefit among the revisit population was explained away by adjusting for age and comorbidities. Nonetheless, considering the additional evidence from ED revisits studies of inpatient outcomes, the ED revisit rate should not be used as a marker for ED quality. 5 At a minimum, the subsequent inpatient outcome should be examined before adjudicating the initial ED quality of care. The slightly better inpatient outcomes among the revisit population also coincided with the finding of declined post-ED mortality among Medicare beneficiaries in the US who had visited an ED from 2009 to 2016. 33 Taken together, these findings suggest that overall the post-ED outcomes of patients vising the ED have improved and that the rate of revisit as a quality metric must be evaluated from a patient outcome perspective.

LIMITATIONS

This study has some potential limitations. First, we included only a limited number of patient outcomes in our analysis. There were additional clinical outcomes worth investigating that require more granular data, such as patient safety events and patient-reported outcomes. Second, we could not ascertain deaths after ED discharge. However, given the small number of post-ED deaths (0.12%) estimated from a prior study, 34 the results should not have materially changed. Third, the data were somewhat aged and contained approximately one-third of the ED visits instead of the entire ED visit universe. However, this was the maximum amount of data that could be requested. As there have been no major policy changes regarding ED revisit in the past few years in Taiwan, the age of the data should have little, if any, influence on our results. Fourth, because we included only adult ED visits our results may not be generalizable to children. Fifth, caution should be exercised when applying the results to other healthcare settings. Finally, while we have adjusted for age, gender, and comorbidities when assessing inpatient outcomes, potential unmeasured confounders may still exist.

In this national ED and inpatient database, patients who were hospitalized after a return visit to the ED within three days did not experience worse outcomes or use more resources than those who were directly admitted during the index ED visit. Our findings suggest that ED revisits per se do not necessarily translate to poor initial ED care and that inpatient outcomes should also be considered for better assessment. Further studies are needed to devise a feasible, sensitive, and specific quality-measure or screening algorithm (eg, return ICU admissions or return in-hospital mortality) for quality issues surrounding ED revisit.

Section Editor: Gary Johnson, MD

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Conflicts of Interest : By the West JEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. This project was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (109-2634-F002-041). There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Is It Safe in Moscow?

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/RussianKerry2-56a39e8d5f9b58b7d0d2ca8c.jpg)

Stanislav Solntsev / Getty Images

When you visit Moscow , Russia, you’re seeing one of the world’s largest, and most expensive, capital cities . While there is a history of violent crime against foreign journalists and aid personnel in Russia, a trip to Moscow is usually safe for mainstream travelers. Most tourists in Moscow only face potential issues with petty crime, though terrorism is also a concern. Visitors should stick to the principal tourist areas and abide by the local security advice.

Travel Advisories

- The U.S. Department of State urges travelers to avoid travel to Russia because of COVID-19 and to "exercise increased caution due to terrorism, harassment, and the arbitrary enforcement of local laws."

- Anyone exploring more of Russia should avoid "The North Caucasus, including Chechnya and Mount Elbrus, due to terrorism, kidnapping, and risk of civil unrest." Also, travelers should stay away from "Crimea due to Russia’s occupation of the Ukrainian territory and abuses by its occupying authorities."

- Canada states travelers should use a high degree of caution in Russia due to the threat of terrorism and crime.

Is Moscow Dangerous?

The Moscow city center is typically safe. In general, the closer you are to the Kremlin , the better. Travelers mainly need to be aware of their surroundings and look out for petty crime. Be especially careful in tourist areas such as Arbat Street and crowded places like the Moscow Metro transit system. The suburbs are also generally fine, though it is advised to stay away from Maryino and Perovo districts.

Terrorism has occurred in the Moscow area, leading authorities to increase security measures. Be more careful at tourist and transportation hubs, places of worship, government buildings, schools, airports, crowds, open markets, and additional tourist sites.

Pickpockets and purse snatching happen often in Russia, perpetrated by groups of children and teenagers who distract tourists to get their wallets and credit cards. Beware of people asking you for help, who then trick you into their scheme. Don’t expect a backpack to be a safe bag bet; instead, invest in something that you can clutch close to your body or purchase a money belt . Always diversify, storing some money in a separate location so that if you are pickpocketed, you'll have cash elsewhere. Keep an eye out for thieves in public transportation, underground walkways, tourist spots, restaurants, hotel rooms and homes, restaurants, and markets.

Is Moscow Safe for Solo Travelers?

Large cities like Moscow in Russia are overall fairly safe if you are traveling alone, and the Moscow Metro public transit is a secure and easy way to get around. But it is still a good idea to follow basic precautions as in any destination. Avoid exploring alone at night, especially in bad areas. You may want to learn some basic Russian phrases or bring a dictionary, as many locals don't speak English. However, in case you need any help, there are tourist police that speak English. Also, exploring with other trusted travelers and locals or on professional tours is often a good way to feel safe.

Is Moscow Safe for Female Travelers?

Catcalling and street harassment are infrequent in Moscow and the rest of Russia and females traveling alone don't usually have problems. There are plenty of police officers on the streets as well. Still, it serves to stick to Moscow's well-lit, public areas, avoid solo night walks, and use your instincts. Women frequenting bars may take receive some friendly attention. Females can wear whatever they want, but those entering Orthodox churches will be required to cover up. Though women in Russia are independent, domestic violence and other inequality issues take place regularly.

Safety Tips for LGBTQ+ Travelers

Russia is not known as a gay-friendly country. However, Moscow is one of the more welcoming cities with a blooming LGBTQ+ community and many friendly restaurants, bars, clubs, and other venues. Hate crimes in Russia have increased since the 2013 anti-gay propaganda law. Openly LGBTQ+ tourists in this conservative country may experience homophobic remarks, discrimination, or even violence, especially if traveling with a partner. Also, while women hold hands or hug publicly—whether romantically involved or not—men should avoid public displays of affection to prevent being insulted or other issues.

Safety Tips for BIPOC Travelers

Moscow and other big cities in Russia have sizable populations of various cultures, so discrimination against BIPOC travelers is rarer than in other parts of the country where it can become dangerous. Some people living in Russia who are Black, Asian, Jewish, and from other backgrounds have experienced racial discrimination and violence. Tourists won't usually experience overt racism but may be the recipients of some stares. If anyone should bother you, be polite and resist being taunted into physically defending yourself.

Safety Tips for Travelers

Travelers should consider the following general tips when visiting:

- It's best not to drink the tap water. If you do, boil it before drinking, though showering is safe and the amount used to brush teeth is generally not harmful. Mineral water is widely drunk, especially at restaurants, and if you prefer not to have it carbonated ask for “ voda byez gaz” (water without gas).

- If you need emergency assistance in case of fire, terrorism, medical issues, or more, dial 112 in Russia for bilingual operators.

- Be judicious about taking photographs, especially of police or officials. This can potentially bring unwanted attention to yourself by members of law enforcement who won’t mind asking to see your passport. Also avoid snapping photos of official-looking buildings, such as embassies and government headquarters.

- Carry your passport in as secure a manner as possible. If you get stopped for any reason by the police, they can fine or arrest you if you don't have the document with you. Also, keep photocopies of your passport, the page on which your travel visa appears, and any other documents that relate to your stay in Russia.

- Use official taxis only and steer clear of illegal taxi companies, especially at night. Ask your hotel to call a reputable taxi company.

U.S. Department of State. " Russia Travel Advisory ." August 6, 2020.

Government of Canada. " Official Global Travel Advisories ." November 19, 2020.

Is It Safe in Peru?

Is It Safe in Guatemala?

Is It Safe in Rio de Janeiro?

Is It Safe in Barbados?

Is It Safe in Egypt?

Is It Safe in Sweden?

Is It Safe in Colombia?

Is It Safe in Jamaica?

Is It Safe in Germany?

Is It Safe in Iceland?

Is It Safe in Mexico?

2020 Travel Warnings for Countries in Africa

Is It Safe in Russia?

Is It Safe in Amsterdam?

Is It Safe in Thailand?

Is It Safe in Trujillo, Peru?

- ALL MOSCOW TOURS

- Getting Russian Visa

- Top 10 Reasons To Go

- Things To Do In Moscow

- Sheremetyevo Airport

- Domodedovo Airport

- Vnukovo Airport

- Airports Transfer

- Layover in Moscow

- Best Moscow Hotels

- Best Moscow Hostels

- Art in Moscow

- Moscow Theatres

- Moscow Parks

- Free Attractions

- Walking Routes

- Sports in Moscow

- Shopping in Moscow

- The Moscow Metro

- Moscow Public Transport

- Taxi in Moscow

- Driving in Moscow

- Moscow Maps & Traffic

- Facts about Moscow – City Factsheet

- Expat Communities

- Groceries in Moscow

- Healthcare in Moscow

- Blogs about Moscow

- Flat Rentals

Healthcare in Moscow – Personal and Family Medicine

Emergency : 112 or 103

Obstetric & gynecologic : +7 495 620-41-70

About medical services in Moscow

Moscow polyclinic

Emergency medical care is provided free to all foreign nationals in case of life-threatening conditions that require immediate medical treatment. You will be given first aid and emergency surgery when necessary in all public health care facilities. Any further treatment will be free only to people with a Compulsory Medical Insurance, or you will need to pay for medical services. Public health care is provided in federal and local care facilities. These include 1. Urban polyclinics with specialists in different areas that offer general medical care. 2. Ambulatory and hospitals that provide a full range of services, including emergency care. 3. Emergency stations opened 24 hours a day, can be visited in a case of a non-life-threatening injury. It is often hard to find English-speaking staff in state facilities, except the largest city hospitals, so you will need a Russian-speaking interpreter to accompany your visit to a free doctor or hospital. If medical assistance is required, the insurance company should be contacted before visiting a medical facility for treatment, except emergency cases. Make sure that you have enough money to pay any necessary fees that may be charged.

Insurance in Russia

Travelers need to arrange private travel insurance before the journey. You would need the insurance when applying for the Russian visa. If you arrange the insurance outside Russia, it is important to make sure the insurer is licensed in Russia. Only licensed companies may be accepted under Russian law. Holders of a temporary residence permit or permanent residence permit (valid for three and five years respectively) should apply for «Compulsory Medical Policy». It covers state healthcare only. An employer usually deals with this. The issued health card is shown whenever medical attention is required. Compulsory Medical Policyholders can get basic health care, such as emergencies, consultations with doctors, necessary scans and tests free. For more complex healthcare every person (both Russian and foreign nationals) must pay extra, or take out additional medical insurance. Clearly, you will have to be prepared to wait in a queue to see a specialist in a public health care facility (Compulsory Medical Policyholders can set an appointment using EMIAS site or ATM). In case you are a UK citizen, free, limited medical treatment in state hospitals will be provided as a part of a reciprocal agreement between Russia and UK.

Some of the major Russian insurance companies are:

Ingosstrakh , Allianz , Reso , Sogaz , AlfaStrakhovanie . We recommend to avoid Rosgosstrakh company due to high volume of denials.

Moscow pharmacies

A.v.e pharmacy in Moscow

Pharmacies can be found in many places around the city, many of them work 24 hours a day. Pharmaceutical kiosks operate in almost every big supermarket. However, only few have English-speaking staff, so it is advised that you know the generic (chemical) name of the medicines you think you are going to need. Many medications can be purchased here over the counter that would only be available by prescription in your home country.

Dental care in Moscow

Dentamix clinic in Moscow

Dental care is usually paid separately by both Russian and expatriate patients, and fees are often quite high. Dentists are well trained and educated. In most places, dental care is available 24 hours a day.

Moscow clinics

«OAO Medicina» clinic

It is standard practice for expats to visit private clinics and hospitals for check-ups, routine health care, and dental care, and only use public services in case of an emergency. Insurance companies can usually provide details of clinics and hospitals in the area speak English (or the language required) and would be the best to use. Investigate whether there are any emergency services or numbers, or any requirements to register with them. Providing copies of medical records is also advised.

Moscow hosts some Western medical clinics that can look after all of your family’s health needs. While most Russian state hospitals are not up to Western standards, Russian doctors are very good.

Some of the main Moscow private medical clinics are:

American Medical Center, European Medical Center , Intermed Center American Clinic , Medsi , Atlas Medical Center , OAO Medicina .

Several Russian hospitals in Moscow have special arrangements with GlavUPDK (foreign diplomatic corps administration in Moscow) and accept foreigners for checkups and treatments at more moderate prices that the Western medical clinics.

Medical emergency in Moscow

Moscow ambulance vehicle

In a case of a medical emergency, dial 112 and ask for the ambulance service (skoraya pomoshch). Staff on these lines most certainly will speak English, still it is always better to ask a Russian speaker to explain the problem and the exact location.

Ambulances come with a doctor and, depending on the case, immediate first aid treatment may be provided. If necessary, the patient is taken to the nearest emergency room or hospital, or to a private hospital if the holder’s insurance policy requires it.

Our Private Tours in Moscow

Moscow metro & stalin skyscrapers private tour, moscow art & design private tour, soviet moscow historical & heritage private tour, gastronomic moscow private tour, «day two» moscow private tour, layover in moscow tailor-made private tour, whole day in moscow private tour, all-in-one moscow essential private tour, tour guide jobs →.

Every year we host more and more private tours in English, Russian and other languages for travelers from all over the world. They need best service, amazing stories and deep history knowledge. If you want to become our guide, please write us.

Contact Info

+7 495 166-72-69

119019 Moscow, Russia, Filippovskiy per. 7, 1

Mon - Sun 10.00 - 18.00

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Focusing on the quality of care in emergency departments, this program builds a culture of continuous improvement. It is designed to help clinicians and hospitals in Ontario identify, audit and investigate underlying causes of return visits to their emergency departments and take steps to address them. Supported by Health Quality Ontario ...

The Emergency Department (ED) Return Visit Quality Program has been in operation since 2016. Each. January, participating hospitals answer a set of questions as part of their annual submission of results to Ontario Health. In the January 2020 submission, we asked hospitals whether they had any questions for other participating sites.

In the ED Return Visit Quality Program, hospitals review data on return visits involving their ED, conduct audits to identify the underlying causes of these return visits, and take steps to address these underlying causes. Hospitals present the results of these audits to their CEO and Quality Committee of the Board and submit results to Ontario ...

The Emergency Department Return Visit Quality Program was launched in Ontario, Canada, to promote a culture of quality. It mandates the province's largest-volume emergency departments (EDs) to audit charts of patients who had a return visit leading to hospital admission, including some of their 72-hour all-cause return visits with admission and all of their 7-day ones with sentinel diagnoses ...

The Emergency Department Return Visit Quality Program Results from the first year. [Accessed September 30, 2017]. ... Emergency department return visits within a large geographic area. J Emerg Med. 2017; 52 (6):801-8. [Google Scholar] 32. Hung SC, Chew G, Kong CT, et al. Unplanned emergency department revisits within 72 hours. J Emerg Med ...

Introduction: Analyzing the charts of patients who have a return visit to an emergency department (ED) requiring hospital admission (termed 'RV') is an efficient way to identify adverse events (AEs). Investigating these AEs can inform efforts to improve the quality of care provided. The ED RV Quality Program (RVQP) is a new initiative supported by Ontario's Ministry of Health and Long ...

Emergency Department (ED) return visit is a known quality indicator for patient care and safety in EDs worldwide. Patients returning to the ED within a short period from initial presentation contribute to overcrowding 1-4 which leads to delayed treatment, patient displeasure, waste of ED resources and increased costs of health care. 1, 2, 5, 6

The Emergency Department Return Visit Quality Program was launched in Ontario, Canada, to promote a culture of quality. It mandates the province's largest-volume emergency departments (EDs) to ...

Return visit reviews have been a longstanding method of identifying emergency department (ED) adverse events and other quality issues, but the evolving culture of safety has shifted their focus: while the traditional view of "bouncebacks" reflected retrospective judgement on individual errors, "return visits" emphasize root-cause analysis and prospective change [].

The Emergency Department (ED) Return Visit Quality Program builds a continuous structure of quality improvement (QI) in Ontario's EDs. This program is an Ontario-wide audit-and-feedback program involving routine analysis of ED return visits resulting in admission. Where quality issues are identified, hospitals take steps to address their root ...

Introduction. Return visits to the emergency department (ED) are common among US children, with 72-hour return rates of 2.5% - 5.2% previously documented. 1 As a quality measure, ED return visits align conceptually with two of the National Quality Strategy's six priority areas: 2 safety of care—as a measure of harm caused by inadequate ED diagnosis or management 3 —and coordination of ...

The Emergency Department Return Visit Quality Program (EDRVQP) is a population-level continuous quality improvement (QI) program connecting EDs across Ontario. The objectives of the study were to utilize the Informatics Stack to provide a description of the EDRVQP HIT architecture and to delineate population health program factors that are ...

The Emergency Department Return Visit Quality Program was launched in Ontario, Canada, to promote a culture of quality. It mandates the province's largest-volume emergency departments (EDs) to audit charts of patients who had a return visit leading to hospital admission, including some of their 72-hour all-cause return visits with admission and all of their 7-day ones with sentinel diagnoses ...

In Ontario, Canadathe EDRVQP spans across 86 EDs, with over 3.6 million ED visits per year (and over 36,000 return visits). This represents over 90% of Ontario's ED visits [28], from a population ...

Introduction: Emergency department (ED) return visits are used for quality monitoring.Health information technology (HIT) has historically supported return visit programs in the same hospital or hospital system. The Emergency Department Return Visit Quality Program (EDRVQP) is a novel population level continuous quality improvement (QI) program connecting EDs across Ontario that leverages HIT.

This page provides the percent of all emergency department (ED) visits with a diagnosis of COVID-19, influenza, or RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) by week.The activity levels of COVID-19, influenza, and RSV in the ED are shown below and whether COVID-19, influenza, and RSV are increasing, decreasing, or stable in the previous week. In addition, ED visit data for these viruses are shown by ...

The 2019 results of the ED Return Visit Quality Program demonstrate many excellent examples of quality improvement initiatives in Ontario's EDs. The program has helped foster a culture of quality in participating sites. Participating sites continue to evolve and learn from the program to support and complement their quality improvement work.

1350 Troy Highway. Moscow, ID 83843. United States. Monday - Friday: 8:00 am-5:00 pm. Saturday - Sunday: Closed. Closed on holidays. Some services are only available by phone. Please call first before going to an office. Services Phone Numbers.

INTRODUCTION. Return emergency department (ED) visits pose a significant burden on both patients and healthcare providers, with approximately 5-10% of the patients returning to the ED within three days. 1 - 4 Return ED visits are not only burdensome but costly, as one study found that the total cost of return ED visits was even higher than the total cost of all initial visits. 1 Due to its ...

Travel Advisories . The U.S. Department of State urges travelers to avoid travel to Russia because of COVID-19 and to "exercise increased caution due to terrorism, harassment, and the arbitrary enforcement of local laws."; Anyone exploring more of Russia should avoid "The North Caucasus, including Chechnya and Mount Elbrus, due to terrorism, kidnapping, and risk of civil unrest."

AMI. In the 2017 submissions, 200 cases involving AMI and a paired diagnosis on the index visit were audited, and 84 (42%) resulted in the identification of a quality issue/AE. In the 2016 report, we identified four themes among the quality issues/AEs involving AMI: Patients who leave against medical advice.

These include 1. Urban polyclinics with specialists in different areas that offer general medical care. 2. Ambulatory and hospitals that provide a full range of services, including emergency care. 3. Emergency stations opened 24 hours a day, can be visited in a case of a non-life-threatening injury.

Applications for the 2025/2026 Academic year will be available starting September 1st, 2024 and will be accepted until March 1st, 2025. Interviews will be held mid-end of March 2025 (date TBD) for the 2025/2026 academic year. Reach out to our Volunteer Coordinator with any questions at [email protected] or 208-883-7163.

Health Quality Ontario has prepared the following resources for participants in this program. Introductory Guidance: Read this guidance document for an overview of the program, including a timeline for program implementation . Frequently Asked Questions: Find the answers to common questions about the Emergency Department Return Visit Quality Program