- Story Writing Guides

12 Hero’s Journey Stages Explained (+ Free Templates)

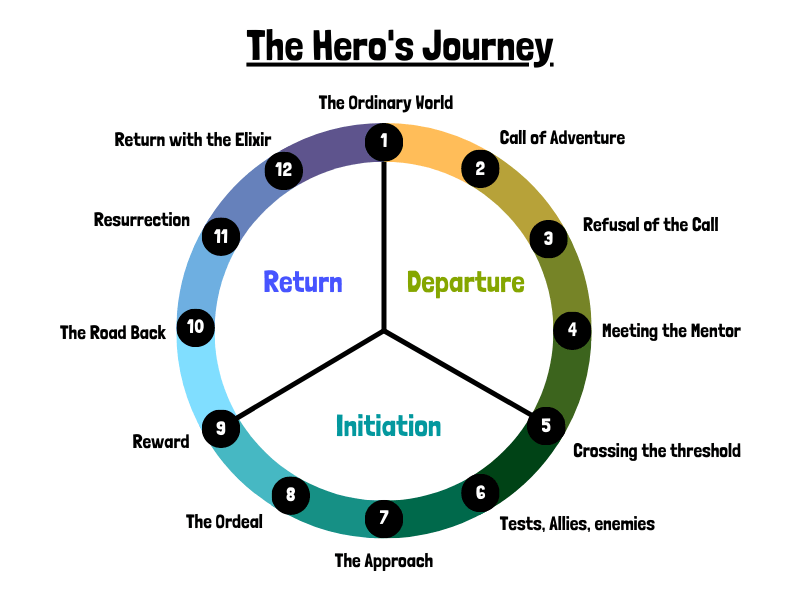

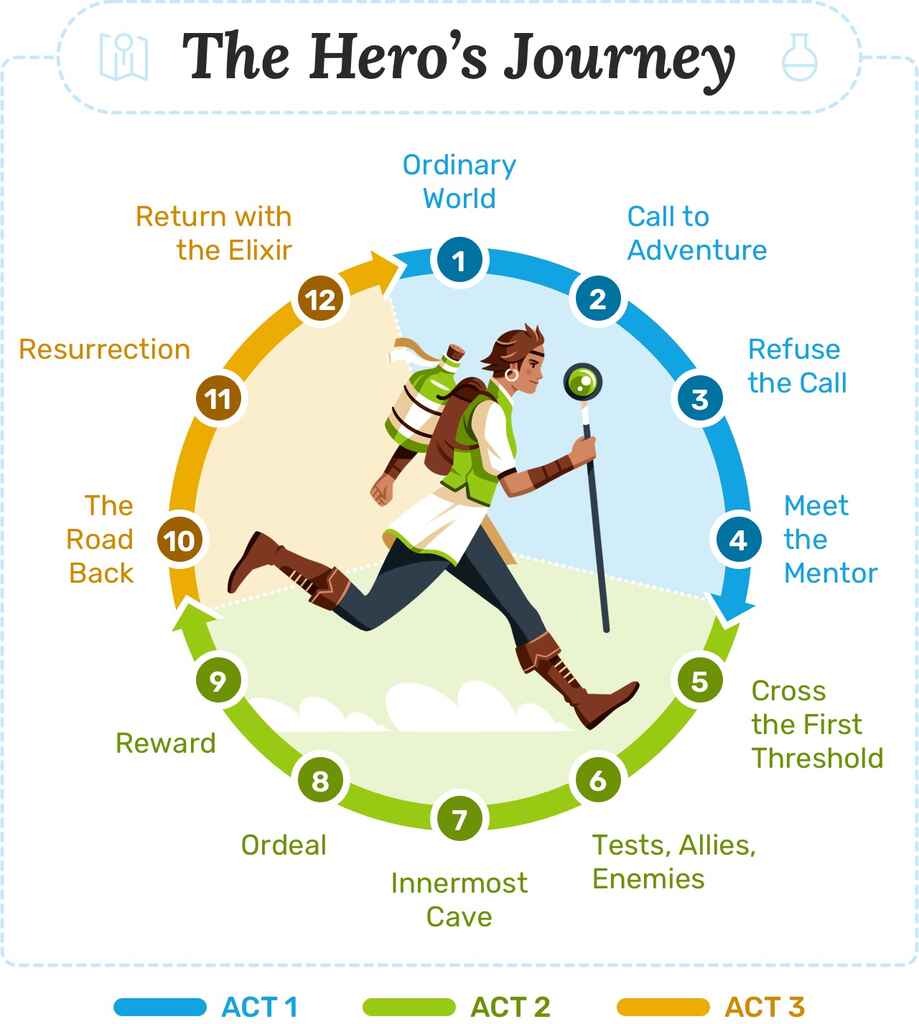

From zero to hero, the hero’s journey is a popular character development arc used in many stories. In today’s post, we will explain the 12 hero’s journey stages, along with the simple example of Cinderella.

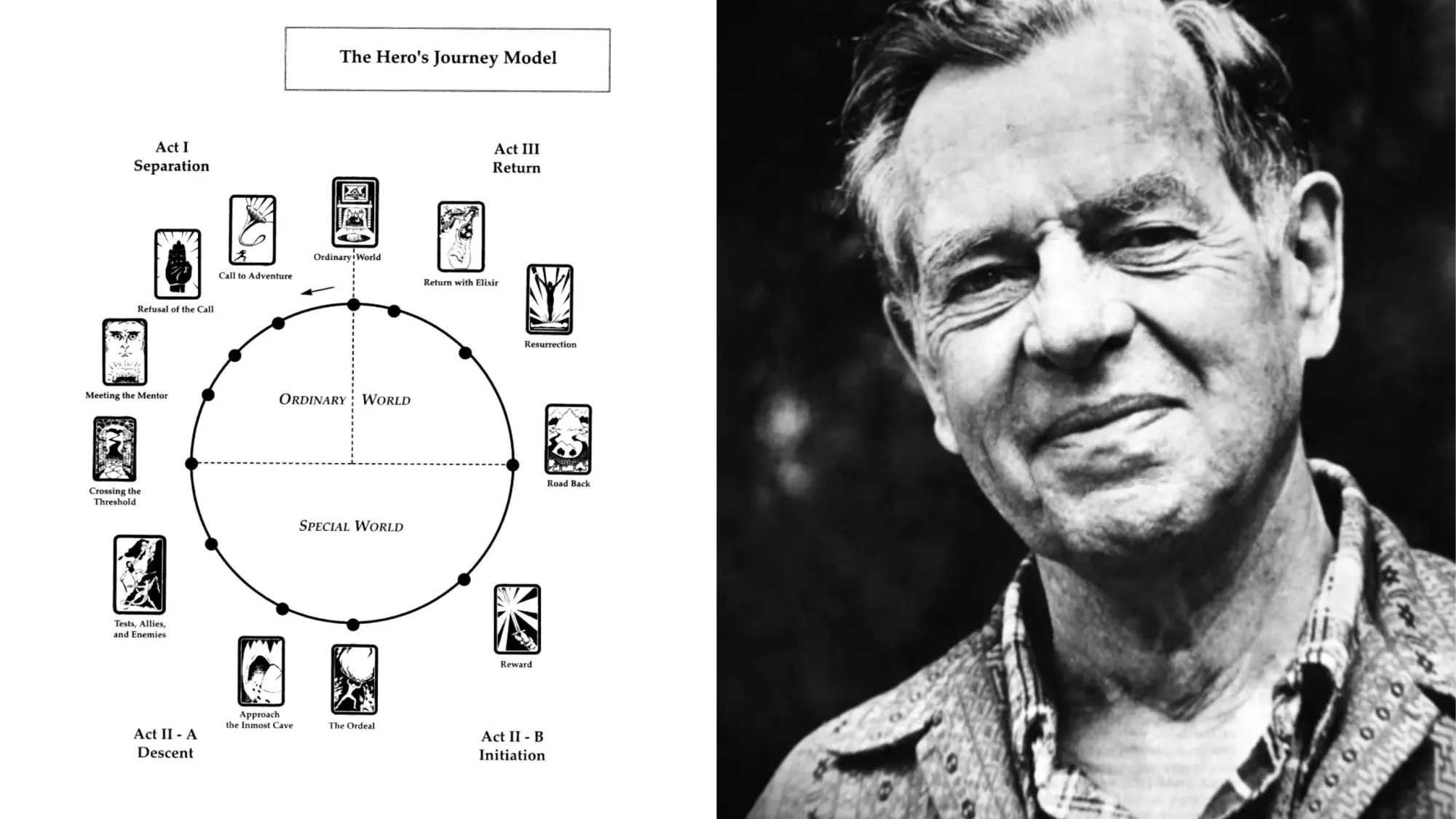

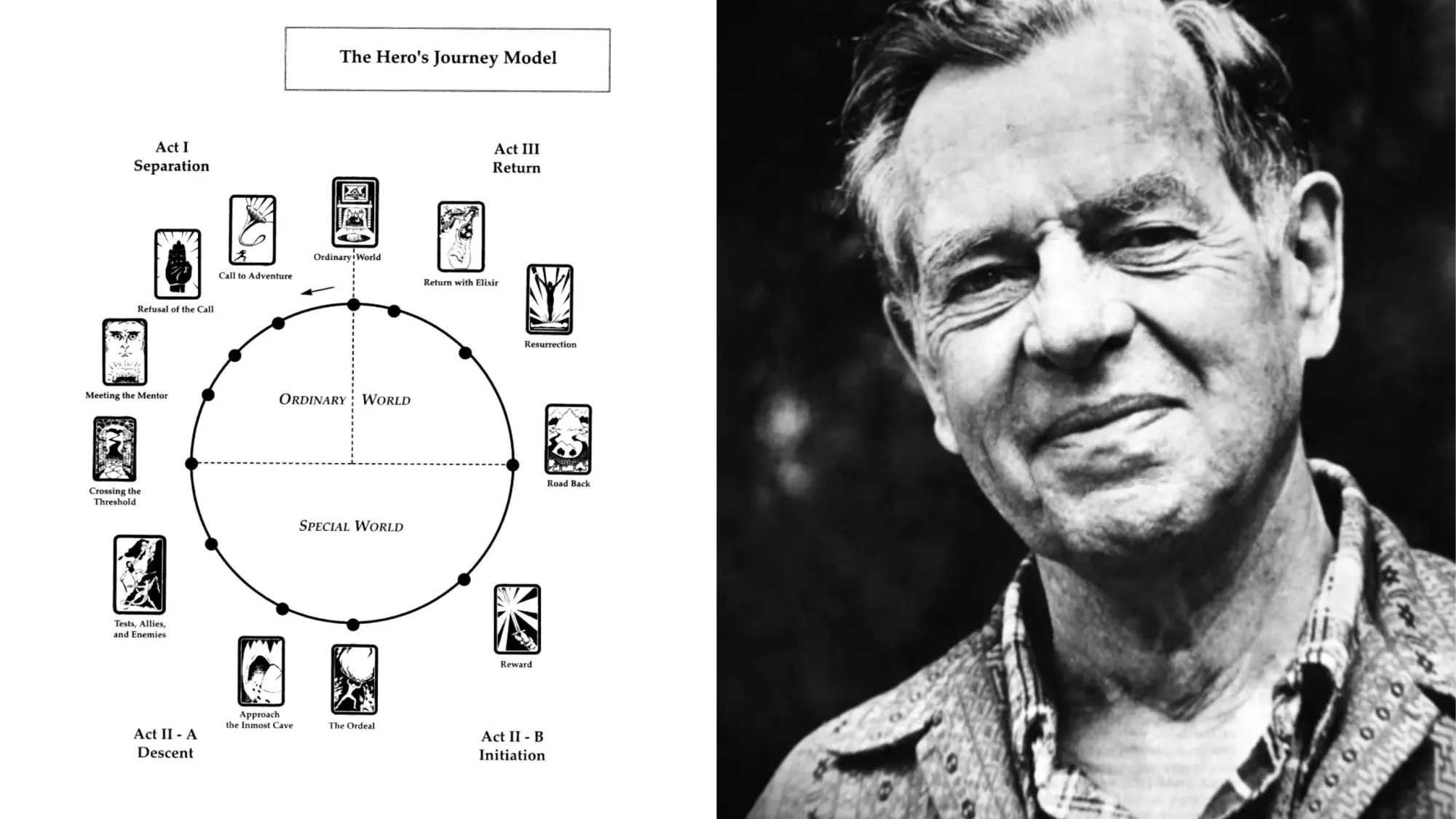

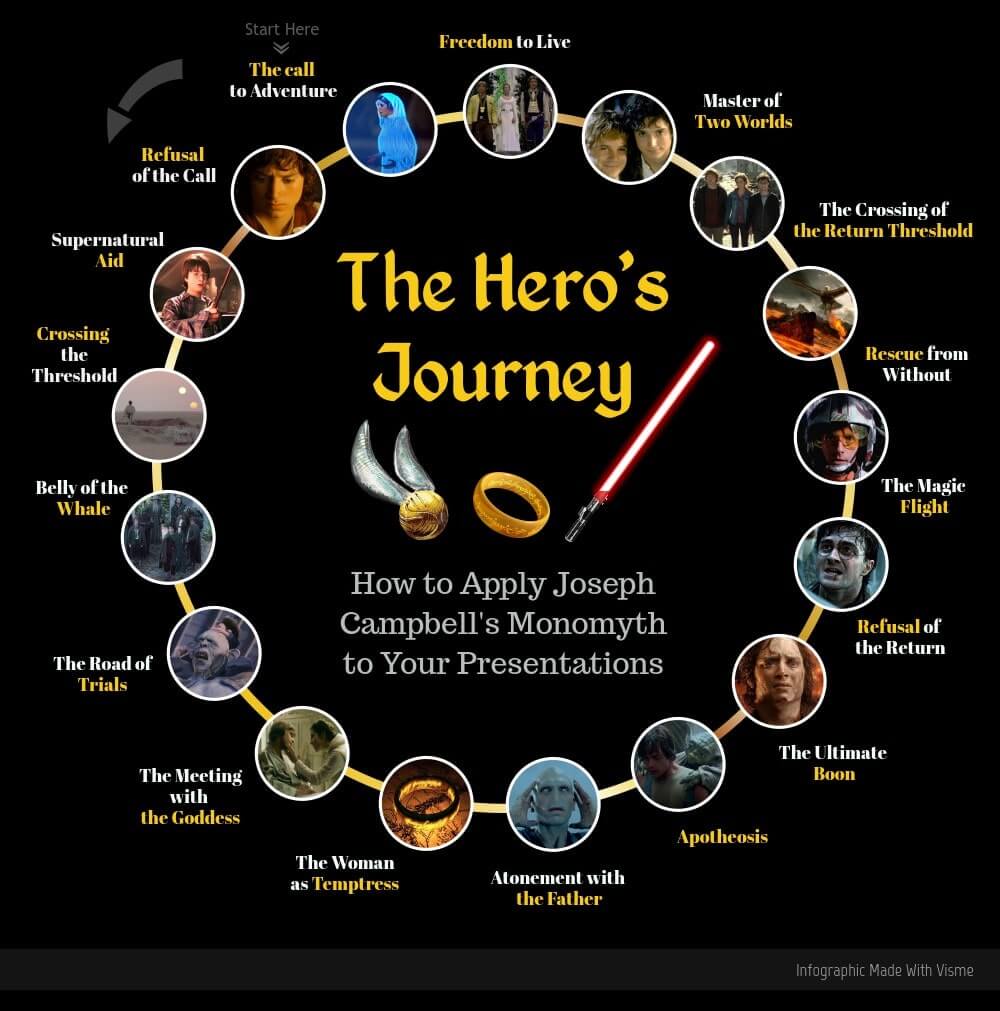

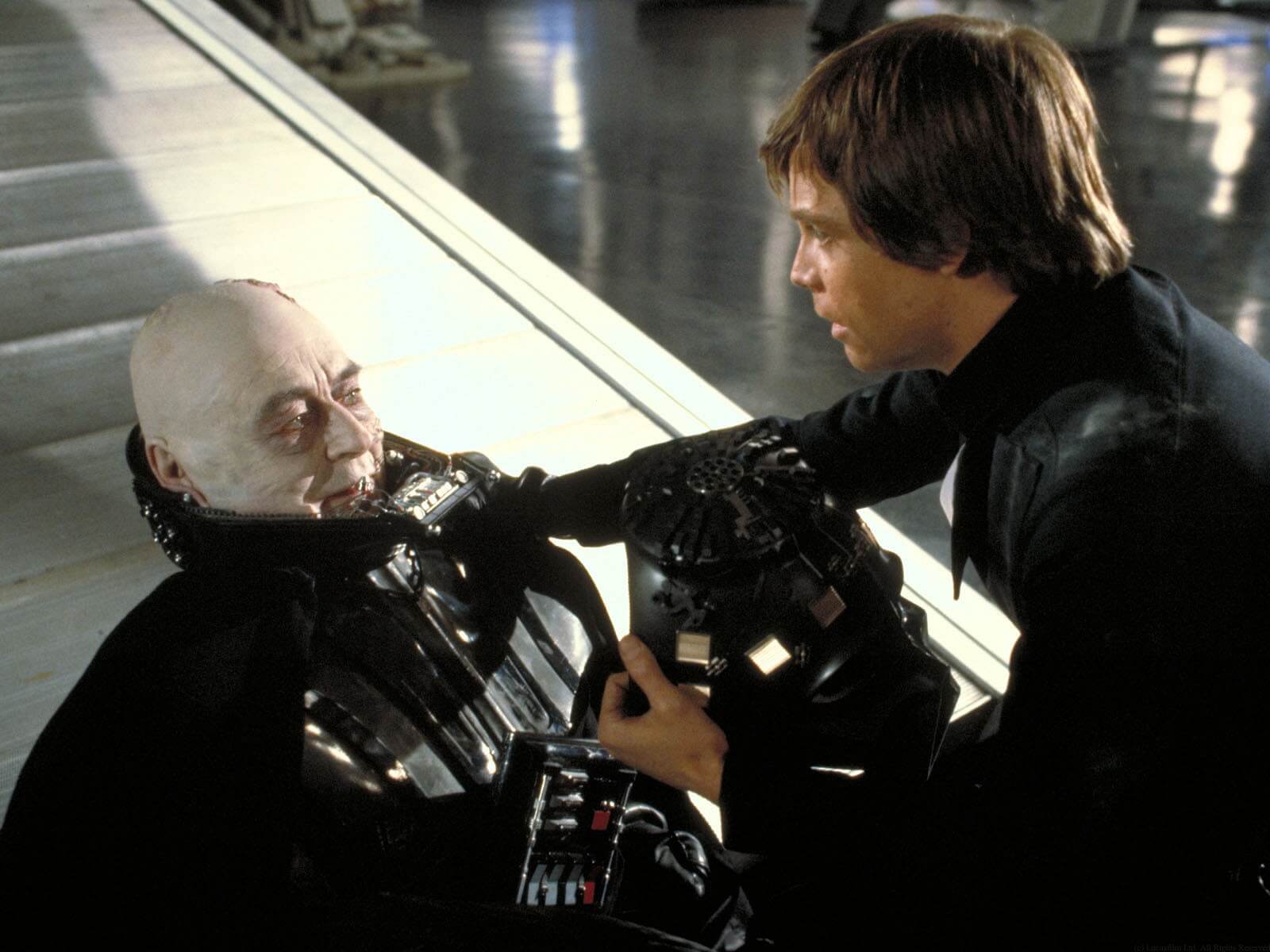

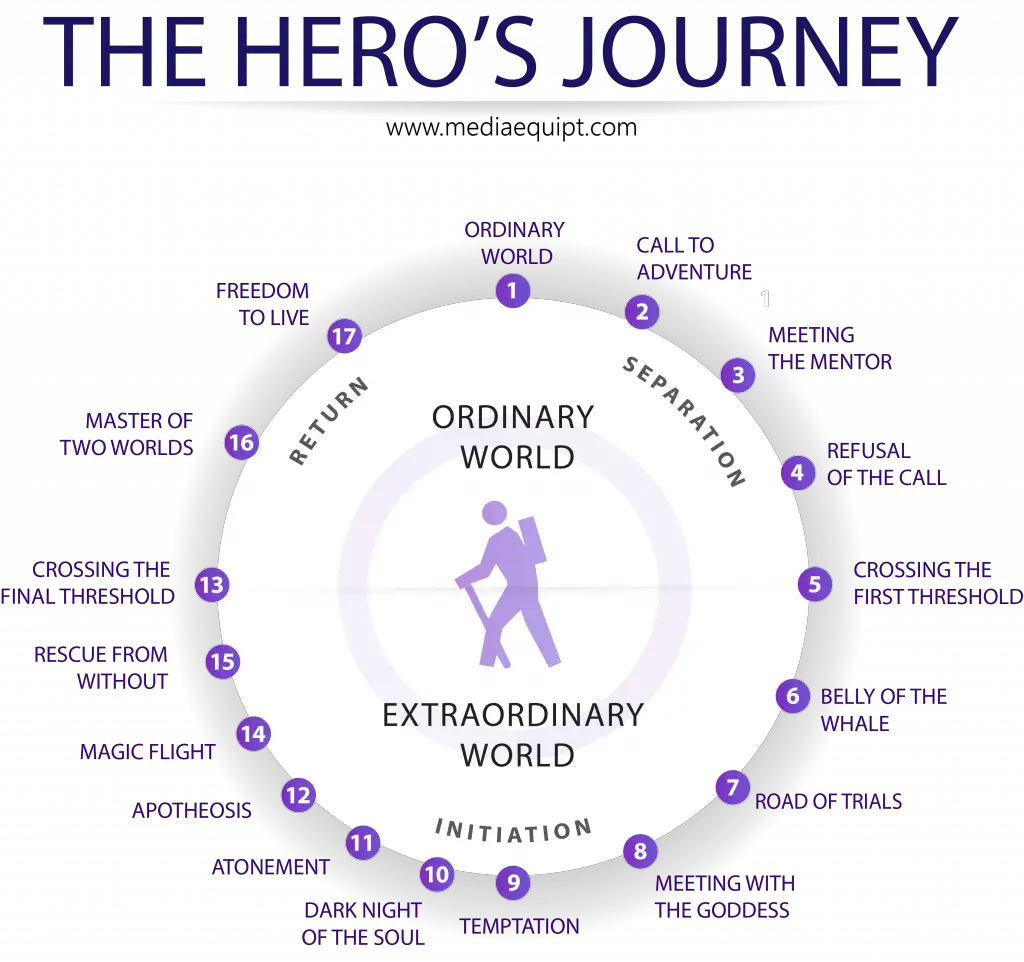

The Hero’s Journey was originally formulated by American writer Joseph Campbell to describe the typical character arc of many classic stories, particularly in the context of mythology and folklore. The original hero’s journey contained 17 steps. Although the hero’s journey has been adapted since then for use in modern fiction, the concept is not limited to literature. It can be applied to any story, video game, film or even music that features an archetypal hero who undergoes a transformation. Common examples of the hero’s journey in popular works include Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, The Hunger Games and Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.

- What is the hero's journey?

Stage 1: The Ordinary World

Stage 2: call of adventure, stage 3: refusal of the call, stage 4: meeting the mentor, stage 5: crossing the threshold, stage 6: tests, allies, enemies, stage 7: the approach, stage 8: the ordeal, stage 9: reward, stage 10: the road back, stage 11: resurrection, stage 12: return with the elixir, cinderella example, campbell’s 17-step journey, leeming’s 8-step journey, cousineau’s 8-step journey.

- Free Hero's Journey Templates

What is the hero’s journey?

The hero’s journey, also known as the monomyth, is a character arc used in many stories. The idea behind it is that heroes undergo a journey that leads them to find their true selves. This is often represented in a series of stages. There are typically 12 stages to the hero’s journey. Each stage represents a change in the hero’s mindset or attitude, which is triggered by an external or internal event. These events cause the hero to overcome a challenge, reach a threshold, and then return to a normal life.

The hero’s journey is a powerful tool for understanding your characters. It can help you decide who they are, what they want, where they came from, and how they will change over time. It can be used to

- Understand the challenges your characters will face

- Understand how your characters react to those challenges

- Help develop your characters’ traits and relationships

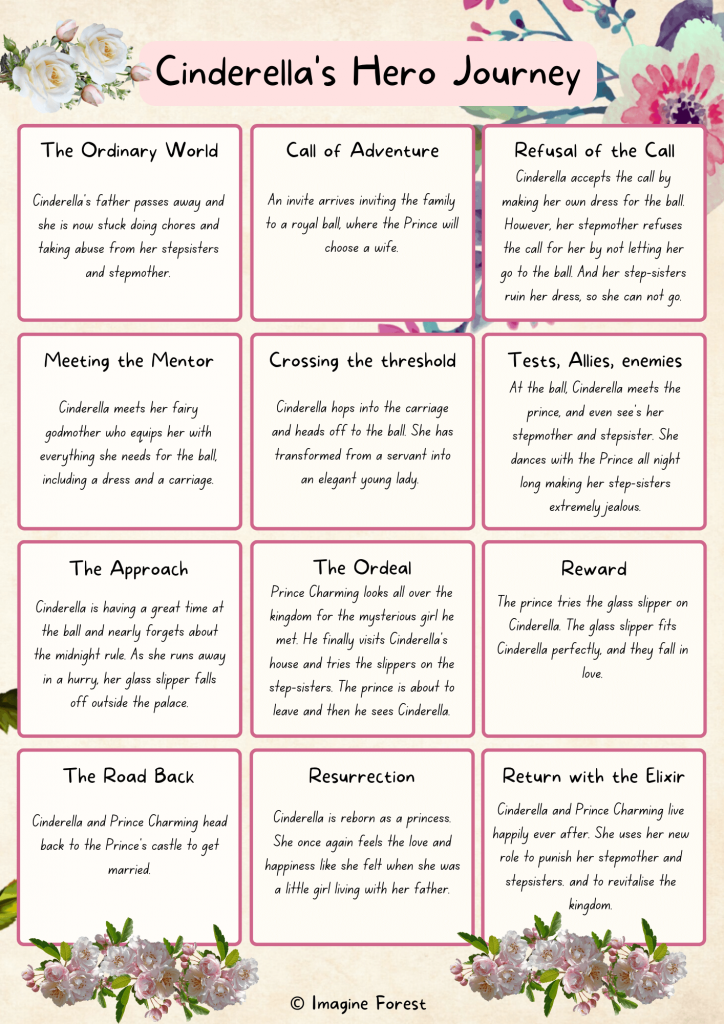

In this post, we will explain each stage of the hero’s journey, using the example of Cinderella.

You might also be interested in our post on the story mountain or this guide on how to outline a book .

12 Hero’s Journey Stages

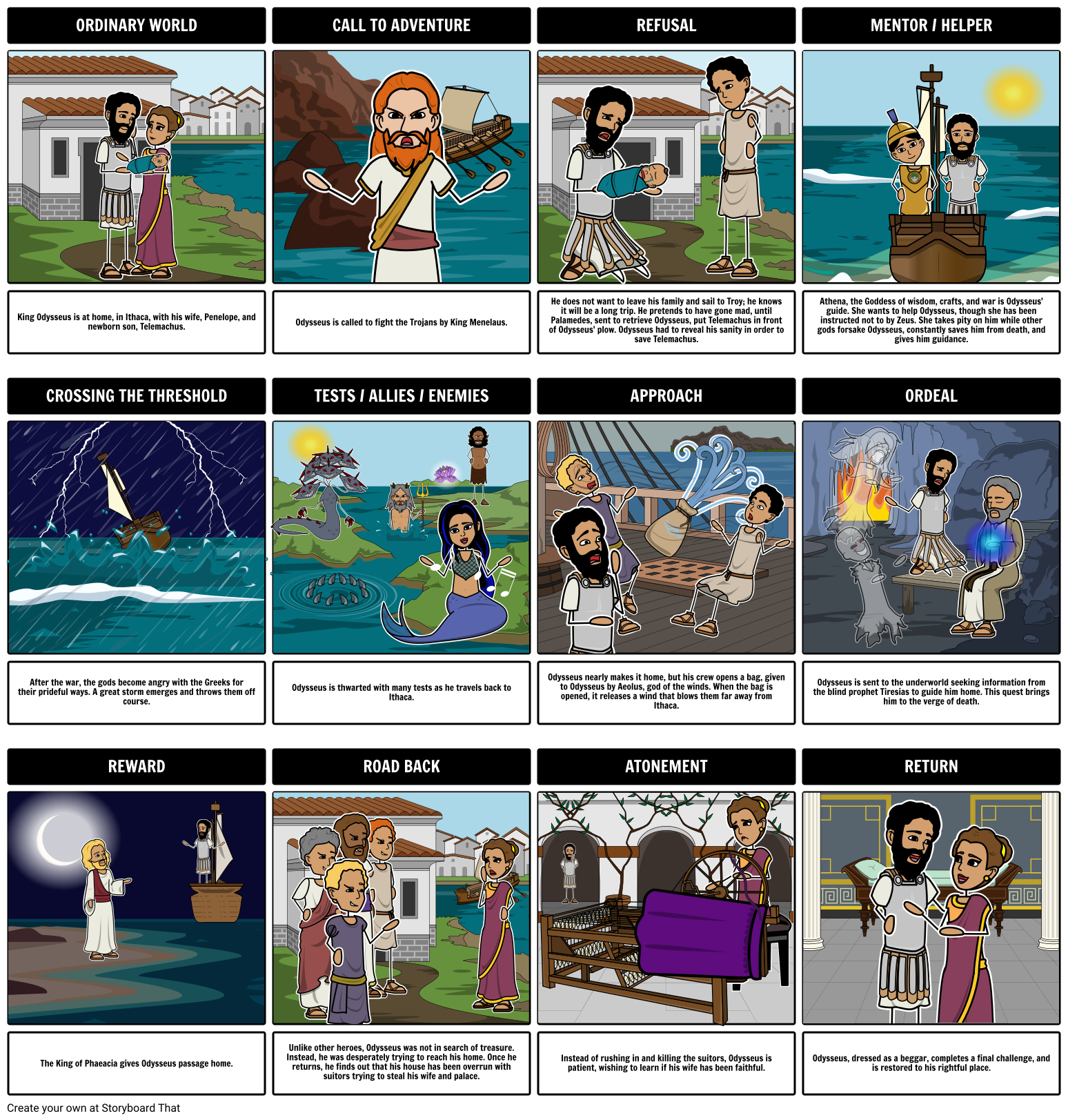

The archetypal hero’s journey contains 12 stages and was created by Christopher Vogler. These steps take your main character through an epic struggle that leads to their ultimate triumph or demise. While these steps may seem formulaic at first glance, they actually form a very flexible structure. The hero’s journey is about transformation, not perfection.

Your hero starts out in the ordinary world. He or she is just like every other person in their environment, doing things that are normal for them and experiencing the same struggles and challenges as everyone else. In the ordinary world, the hero feels stuck and confused, so he or she goes on a quest to find a way out of this predicament.

Example: Cinderella’s father passes away and she is now stuck doing chores and taking abuse from her stepsisters and stepmother.

The hero gets his or her first taste of adventure when the call comes. This could be in the form of an encounter with a stranger or someone they know who encourages them to take a leap of faith. This encounter is typically an accident, a series of coincidences that put the hero in the right place at the right time.

Example: An invite arrives inviting the family to a royal ball where the Prince will choose a wife.

Some people will refuse to leave their safe surroundings and live by their own rules. The hero has to overcome the negative influences in order to hear the call again. They also have to deal with any personal doubts that arise from thinking too much about the potential dangers involved in the quest. It is common for the hero to deny their own abilities in this stage and to lack confidence in themselves.

Example: Cinderella accepts the call by making her own dress for the ball. However, her stepmother refuses the call for her by not letting her go to the ball. And her step-sisters ruin her dress, so she can not go.

After hearing the call, the hero begins a relationship with a mentor who helps them learn about themselves and the world. In some cases, the mentor may be someone the hero already knows. The mentor is usually someone who is well-versed in the knowledge that the hero needs to acquire, but who does not judge the hero for their lack of experience.

Example: Cinderella meets her fairy godmother who equips her with everything she needs for the ball, including a dress and a carriage.

The hero leaves their old life behind and enters the unfamiliar new world. The crossing of the threshold symbolises leaving their old self behind and becoming a new person. Sometimes this can include learning a new skill or changing their physical appearance. It can also include a time of wandering, which is an essential part of the hero’s journey.

Example: Cinderella hops into the carriage and heads off to the ball. She has transformed from a servant into an elegant young lady.

As the hero goes on this journey, they will meet both allies (people who help the hero) and enemies (people who try to stop the hero). There will also be tests, where the hero is tempted to quit, turn back, or become discouraged. The hero must be persistent and resilient to overcome challenges.

Example: At the ball, Cinderella meets the prince, and even see’s her stepmother and stepsister. She dances with Prince all night long making her step-sisters extremely jealous.

The hero now reaches the destination of their journey, in some cases, this is a literal location, such as a cave or castle. It could also be metaphorical, such as the hero having an internal conflict or having to make a difficult decision. In either case, the hero has to confront their deepest fears in this stage with bravery. In some ways, this stage can mark the end of the hero’s journey because the hero must now face their darkest fears and bring them under control. If they do not do this, the hero could be defeated in the final battle and will fail the story.

Example: Cinderella is having a great time at the ball and nearly forgets about the midnight rule. As she runs away in a hurry, her glass slipper falls off outside the palace.

The hero has made it to the final challenge of their journey and now must face all odds and defeat their greatest adversary. Consider this the climax of the story. This could be in the form of a physical battle, a moral dilemma or even an emotional challenge. The hero will look to their allies or mentor for further support and guidance in this ordeal. Whatever happens in this stage could change the rest of the story, either for good or bad.

Example: Prince Charming looks all over the kingdom for the mysterious girl he met at the ball. He finally visits Cinderella’s house and tries the slippers on the step-sisters. The prince is about to leave and then he sees Cinderella in the corner cleaning.

When the hero has defeated the most powerful and dangerous of adversaries, they will receive their reward. This reward could be an object, a new relationship or even a new piece of knowledge. The reward, which typically comes as a result of the hero’s perseverance and hard work, signifies the end of their journey. Given that the hero has accomplished their goal and served their purpose, it is a time of great success and accomplishment.

Example: The prince tries the glass slipper on Cinderella. The glass slipper fits Cinderella perfectly, and they fall in love.

The journey is now complete, and the hero is now heading back home. As the hero considers their journey and reflects on the lessons they learned along the way, the road back is sometimes marked by a sense of nostalgia or even regret. As they must find their way back to the normal world and reintegrate into their former life, the hero may encounter additional difficulties or tests along the way. It is common for the hero to run into previous adversaries or challenges they believed they had overcome.

Example: Cinderella and Prince Charming head back to the Prince’s castle to get married.

The hero has one final battle to face. At this stage, the hero might have to fight to the death against a much more powerful foe. The hero might even be confronted with their own mortality or their greatest fear. This is usually when the hero’s true personality emerges. This stage is normally symbolised by the hero rising from the dark place and fighting back. This dark place could again be a physical location, such as the underground or a dark cave. It might even be a dark, mental state, such as depression. As the hero rises again, they might change physically or even experience an emotional transformation.

Example: Cinderella is reborn as a princess. She once again feels the love and happiness that she felt when she was a little girl living with her father.

At the end of the story, the hero returns to the ordinary world and shares the knowledge gained in their journey with their fellow man. This can be done by imparting some form of wisdom, an object of great value or by bringing about a social revolution. In all cases, the hero returns changed and often wiser.

Example: Cinderella and Prince Charming live happily ever after. She uses her new role to punish her stepmother and stepsisters and to revitalise the kingdom.

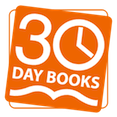

We have used the example of Cinderella in Vogler’s hero’s journey model below:

Below we have briefly explained the other variations of the hero’s journey arc.

The very first hero’s journey arc was created by Joseph Campbell in 1949. It contained the following 17 steps:

- The Call to Adventure: The hero receives a call or a reason to go on a journey.

- Refusal of the Call: The hero does not accept the quest. They worry about their own abilities or fear the journey itself.

- Supernatural Aid: Someone (the mentor) comes to help the hero and they have supernatural powers, which are usually magical.

- The Crossing of the First Threshold: A symbolic boundary is crossed by the hero, often after a test.

- Belly of the Whale: The point where the hero has the most difficulty making it through.

- The Road of Trials: In this step, the hero will be tempted and tested by the outside world, with a number of negative experiences.

- The Meeting with the Goddess: The hero meets someone who can give them the knowledge, power or even items for the journey ahead.

- Woman as the Temptress: The hero is tempted to go back home or return to their old ways.

- Atonement with the Father: The hero has to make amends for any wrongdoings they may have done in the past. They need to confront whatever holds them back.

- Apotheosis: The hero gains some powerful knowledge or grows to a higher level.

- The Ultimate Boon: The ultimate boon is the reward for completing all the trials of the quest. The hero achieves their ultimate goal and feels powerful.

- Refusal of the Return: After collecting their reward, the hero refuses to return to normal life. They want to continue living like gods.

- The Magic Flight: The hero escapes with the reward in hand.

- Rescue from Without: The hero has been hurt and needs help from their allies or guides.

- The Crossing of the Return Threshold: The hero must come back and learn to integrate with the ordinary world once again.

- Master of the Two Worlds: The hero shares their wisdom or gifts with the ordinary world. Learning to live in both worlds.

- Freedom to Live: The hero accepts the new version of themselves and lives happily without fear.

David Adams Leeming later adapted the hero’s journey based on his research of legendary heroes found in mythology. He noted the following steps as a pattern that all heroes in stories follow:

- Miraculous conception and birth: This is the first trauma that the hero has to deal with. The Hero is often an orphan or abandoned child and therefore faces many hardships early on in life.

- Initiation of the hero-child: The child faces their first major challenge. At this point, the challenge is normally won with assistance from someone else.

- Withdrawal from family or community: The hero runs away and is tempted by negative forces.

- Trial and quest: A quest finds the hero giving them an opportunity to prove themselves.

- Death: The hero fails and is left near death or actually does die.

- Descent into the underworld: The hero rises again from death or their near-death experience.

- Resurrection and rebirth: The hero learns from the errors of their way and is reborn into a better, wiser being.

- Ascension, apotheosis, and atonement: The hero gains some powerful knowledge or grows to a higher level (sometimes a god-like level).

In 1990, Phil Cousineau further adapted the hero’s journey by simplifying the steps from Campbell’s model and rearranging them slightly to suit his own findings of heroes in literature. Again Cousineau’s hero’s journey included 8 steps:

- The call to adventure: The hero must have a reason to go on an adventure.

- The road of trials: The hero undergoes a number of tests that help them to transform.

- The vision quest: Through the quest, the hero learns the errors of their ways and has a realisation of something.

- The meeting with the goddess: To help the hero someone helps them by giving them some knowledge, power or even items for the journey ahead.

- The boon: This is the reward for completing the journey.

- The magic flight: The hero must escape, as the reward is attached to something terrible.

- The return threshold: The hero must learn to live back in the ordinary world.

- The master of two worlds: The hero shares their knowledge with the ordinary world and learns to live in both worlds.

As you can see, every version of the hero’s journey is about the main character showing great levels of transformation. Their journey may start and end at the same location, but they have personally evolved as a character in your story. Once a weakling, they now possess the knowledge and skill set to protect their world if needed.

Free Hero’s Journey Templates

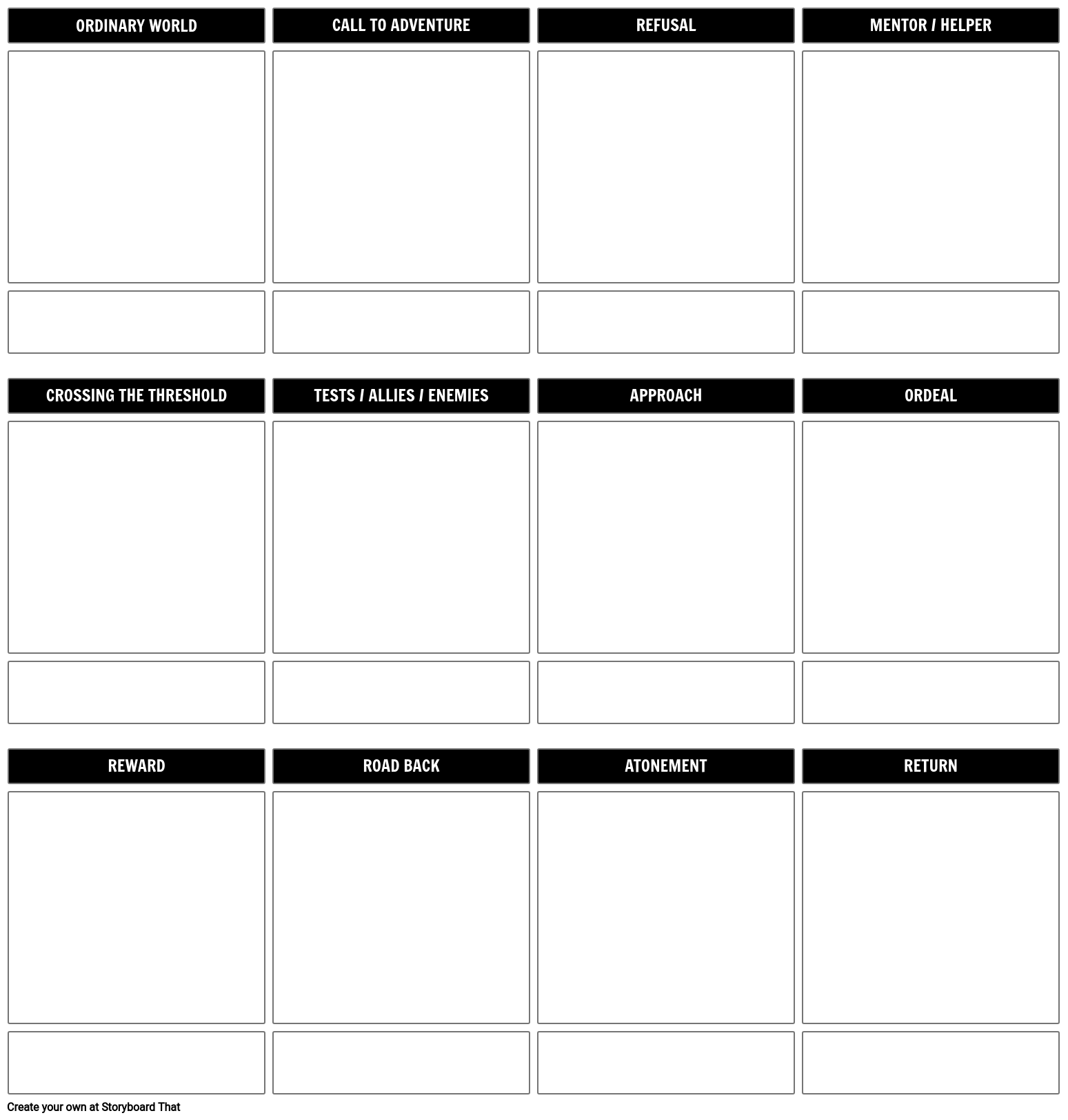

Use the free Hero’s journey templates below to practice the skills you learned in this guide! You can either draw or write notes in each of the scene boxes. Once the template is complete, you will have a better idea of how your main character or the hero of your story develops over time:

The storyboard template below is a great way to develop your main character and organise your story:

Did you find this guide on the hero’s journey stages useful? Let us know in the comments below.

Marty the wizard is the master of Imagine Forest. When he's not reading a ton of books or writing some of his own tales, he loves to be surrounded by the magical creatures that live in Imagine Forest. While living in his tree house he has devoted his time to helping children around the world with their writing skills and creativity.

Related Posts

Comments loading...

Holiday Savings

cui:common.components.upgradeModal.offerHeader_undefined

The hero's journey: a story structure as old as time, the hero's journey offers a powerful framework for creating quest-based stories emphasizing self-transformation..

Table of Contents

Holding out for a hero to take your story to the next level?

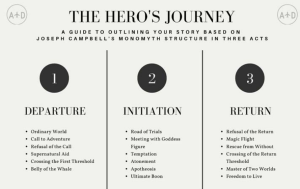

The Hero’s Journey might be just what you’ve been looking for. Created by Joseph Campbell, this narrative framework packs mythic storytelling into a series of steps across three acts, each representing a crucial phase in a character's transformative journey.

Challenge . Growth . Triumph .

Whether you're penning a novel, screenplay, or video game, The Hero’s Journey is a tried-and-tested blueprint for crafting epic stories that transcend time and culture. Let’s explore the steps together and kickstart your next masterpiece.

What is the Hero’s Journey?

The Hero’s Journey is a famous template for storytelling, mapping a hero's adventurous quest through trials and tribulations to ultimate transformation.

What are the Origins of the Hero’s Journey?

The Hero’s Journey was invented by Campbell in his seminal 1949 work, The Hero with a Thousand Faces , where he introduces the concept of the "monomyth."

A comparative mythologist by trade, Campbell studied myths from cultures around the world and identified a common pattern in their narratives. He proposed that all mythic narratives are variations of a single, universal story, structured around a hero's adventure, trials, and eventual triumph.

His work unveiled the archetypal hero’s path as a mirror to humanity’s commonly shared experiences and aspirations. It was subsequently named one of the All-Time 100 Nonfiction Books by TIME in 2011.

How are the Hero’s and Heroine’s Journeys Different?

While both the Hero's and Heroine's Journeys share the theme of transformation, they diverge in their focus and execution.

The Hero’s Journey, as outlined by Campbell, emphasizes external challenges and a quest for physical or metaphorical treasures. In contrast, Murdock's Heroine’s Journey, explores internal landscapes, focusing on personal reconciliation, emotional growth, and the path to self-actualization.

In short, heroes seek to conquer the world, while heroines seek to transform their own lives; but…

Twelve Steps of the Hero’s Journey

So influential was Campbell’s monomyth theory that it's been used as the basis for some of the largest franchises of our generation: The Lord of the Rings , Harry Potter ...and George Lucas even cited it as a direct influence on Star Wars .

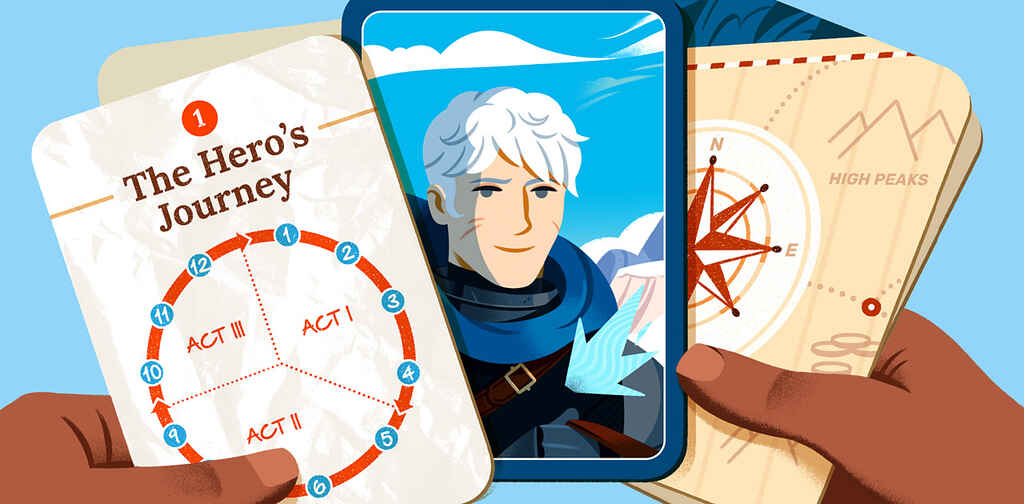

There are, in fact, several variations of the Hero's Journey, which we discuss further below. But for this breakdown, we'll use the twelve-step version outlined by Christopher Vogler in his book, The Writer's Journey (seemingly now out of print, unfortunately).

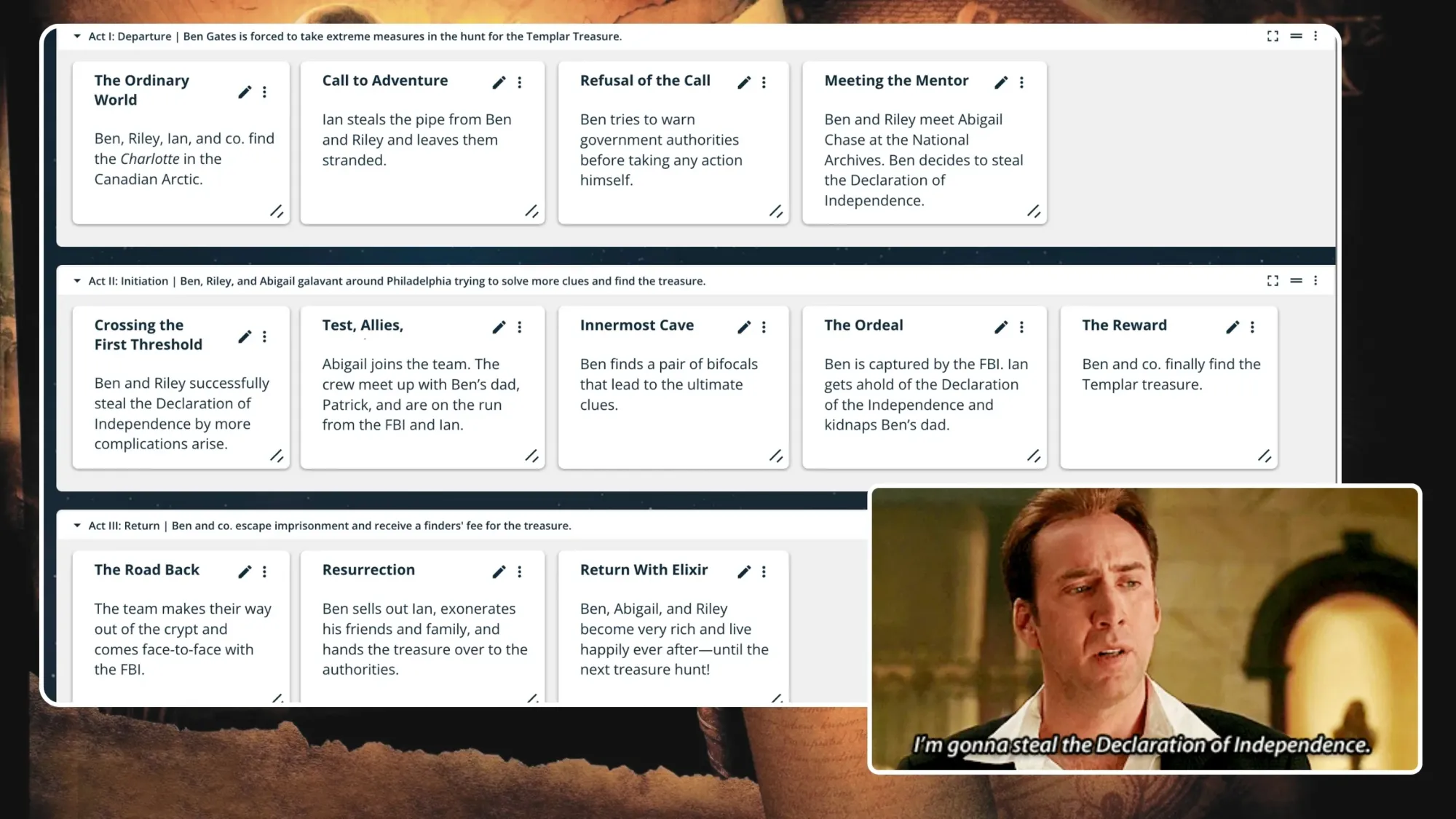

You probably already know the above stories pretty well so we’ll unpack the twelve steps of the Hero's Journey using Ben Gates’ journey in National Treasure as a case study—because what is more heroic than saving the Declaration of Independence from a bunch of goons?

Ye be warned: Spoilers ahead!

Act One: Departure

Step 1. the ordinary world.

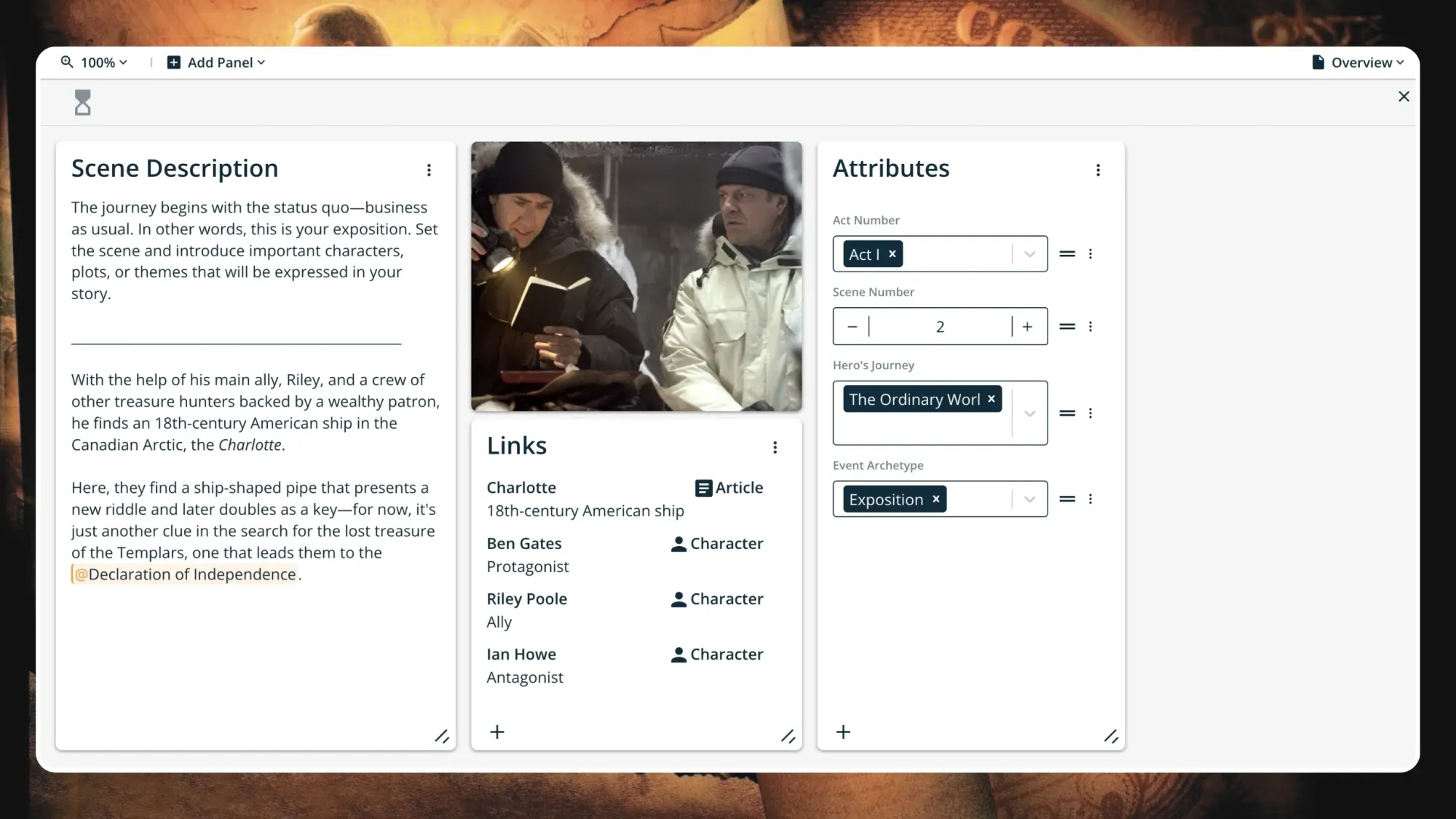

The journey begins with the status quo—business as usual. We meet the hero and are introduced to the Known World they live in. In other words, this is your exposition, the starting stuff that establishes the story to come.

National Treasure begins in media res (preceded only by a short prologue), where we are given key information that introduces us to Ben Gates' world, who he is (a historian from a notorious family), what he does (treasure hunts), and why he's doing it (restoring his family's name).

With the help of his main ally, Riley, and a crew of other treasure hunters backed by a wealthy patron, he finds an 18th-century American ship in the Canadian Arctic, the Charlotte . Here, they find a ship-shaped pipe that presents a new riddle and later doubles as a key—for now, it's just another clue in the search for the lost treasure of the Templars, one that leads them to the Declaration of Independence.

Step 2. The Call to Adventure

The inciting incident takes place and the hero is called to act upon it. While they're still firmly in the Known World, the story kicks off and leaves the hero feeling out of balance. In other words, they are placed at a crossroads.

Ian (the wealthy patron of the Charlotte operation) steals the pipe from Ben and Riley and leaves them stranded. This is a key moment: Ian becomes the villain, Ben has now sufficiently lost his funding for this expedition, and if he decides to pursue the chase, he'll be up against extreme odds.

Step 3. Refusal of the Call

The hero hesitates and instead refuses their call to action. Following the call would mean making a conscious decision to break away from the status quo. Ahead lies danger, risk, and the unknown; but here and now, the hero is still in the safety and comfort of what they know.

Ben debates continuing the hunt for the Templar treasure. Before taking any action, he decides to try and warn the authorities: the FBI, Homeland Security, and the staff of the National Archives, where the Declaration of Independence is housed and monitored. Nobody will listen to him, and his family's notoriety doesn't help matters.

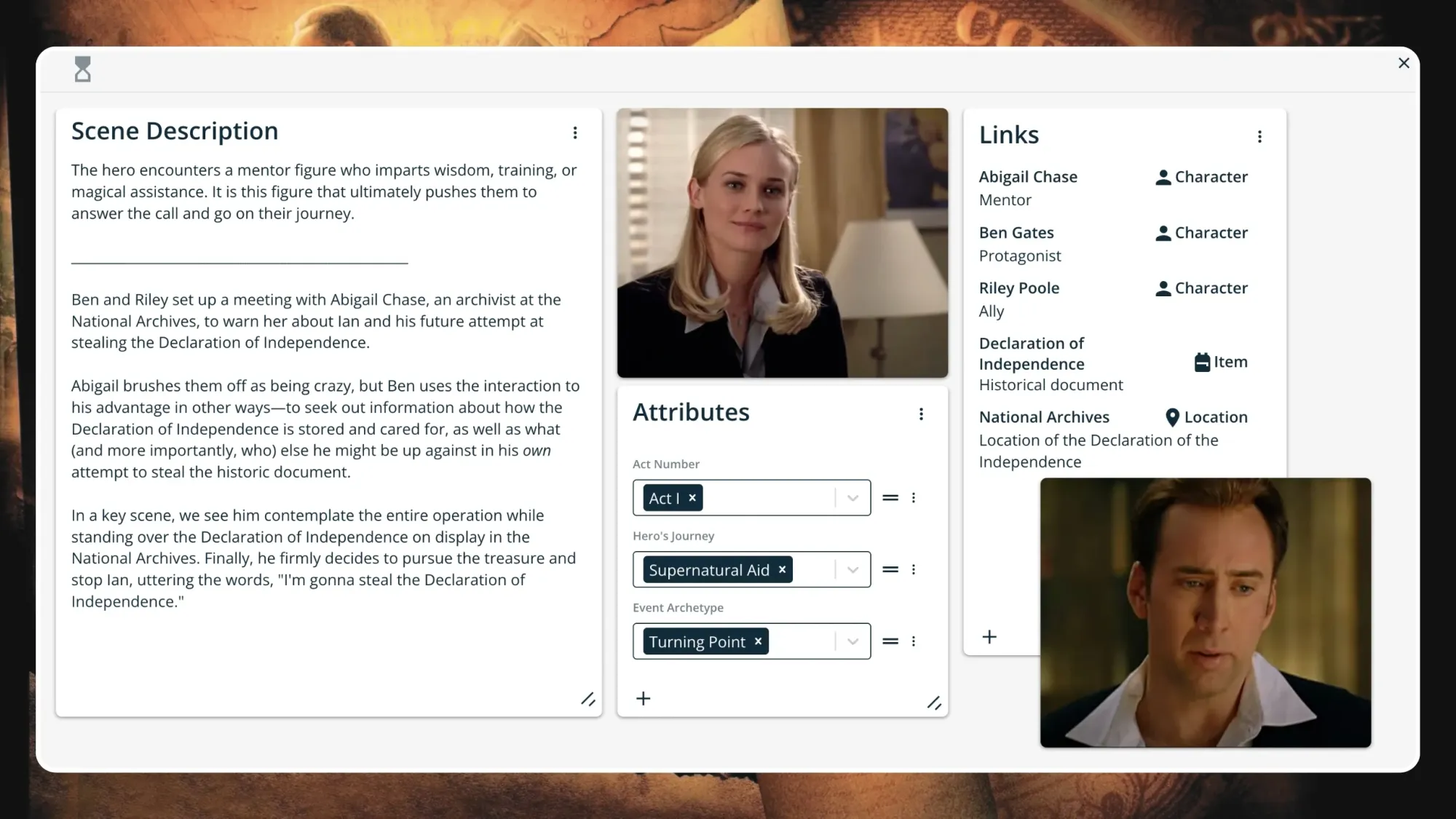

Step 4. Meeting the Mentor

The protagonist receives knowledge or motivation from a powerful or influential figure. This is a tactical move on the hero's part—remember that it was only the previous step in which they debated whether or not to jump headfirst into the unknown. By Meeting the Mentor, they can gain new information or insight, and better equip themselves for the journey they might to embark on.

Abigail, an archivist at the National Archives, brushes Ben and Riley off as being crazy, but Ben uses the interaction to his advantage in other ways—to seek out information about how the Declaration of Independence is stored and cared for, as well as what (and more importantly, who) else he might be up against in his own attempt to steal it.

In a key scene, we see him contemplate the entire operation while standing over the glass-encased Declaration of Independence. Finally, he firmly decides to pursue the treasure and stop Ian, uttering the famous line, "I'm gonna steal the Declaration of Independence."

Act Two: Initiation

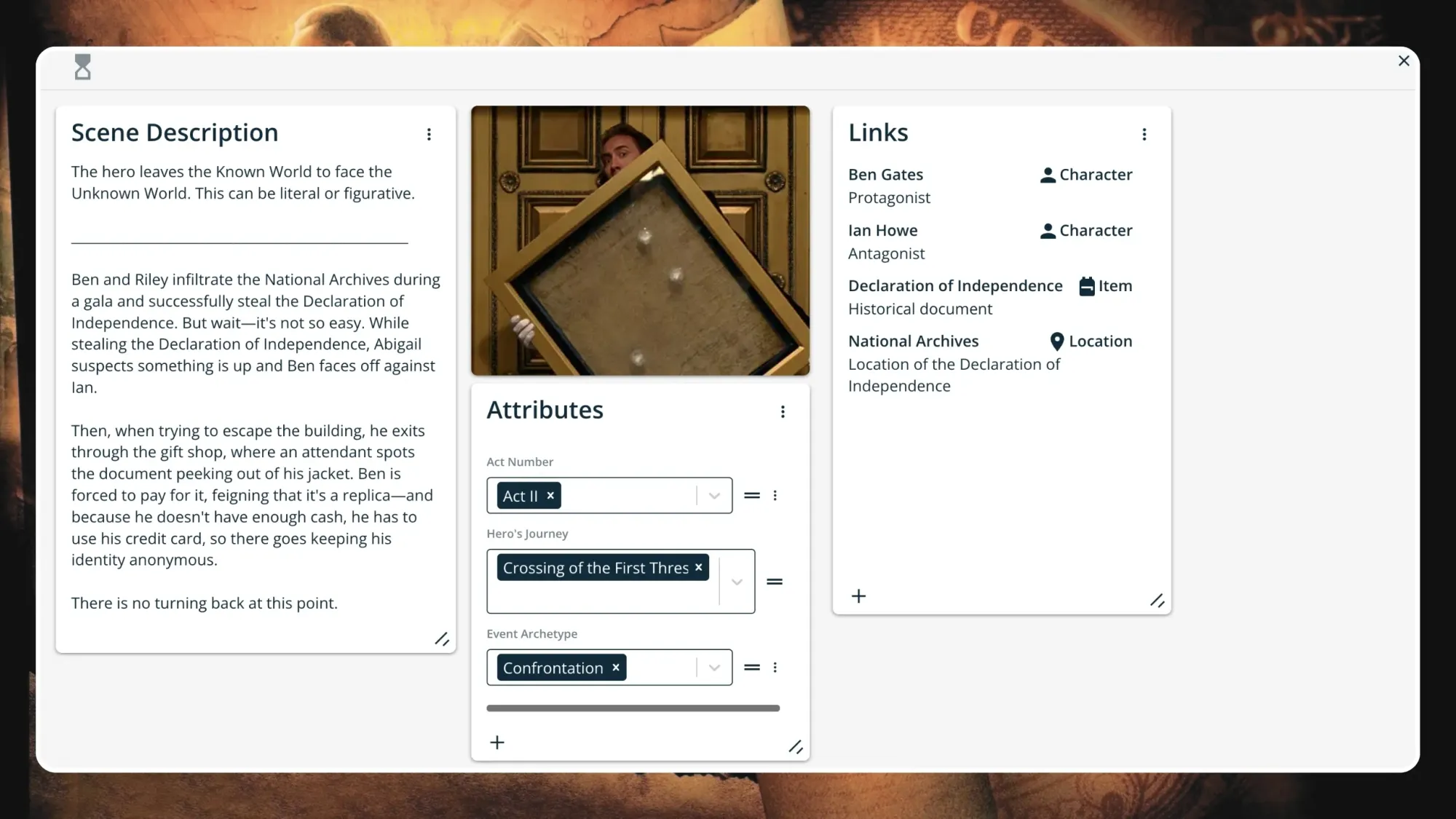

Step 5. crossing the threshold.

The hero leaves the Known World to face the Unknown World. They are fully committed to the journey, with no way to turn back now. There may be a confrontation of some sort, and the stakes will be raised.

Ben and Riley infiltrate the National Archives during a gala and successfully steal the Declaration of Independence. But wait—it's not so easy. While stealing the Declaration of Independence, Abigail suspects something is up and Ben faces off against Ian.

Then, when trying to escape the building, Ben exits through the gift shop, where an attendant spots the document peeking out of his jacket. He is forced to pay for it, feigning that it's a replica—and because he doesn't have enough cash, he has to use his credit card, so there goes keeping his identity anonymous.

The game is afoot.

Step 6. Tests, Allies, Enemies

The hero explores the Unknown World. Now that they have firmly crossed the threshold from the Known World, the hero will face new challenges and possibly meet new enemies. They'll have to call upon their allies, new and old, in order to keep moving forward.

Abigail reluctantly joins the team under the agreement that she'll help handle the Declaration of Independence, given her background in document archiving and restoration. Ben and co. seek the aid of Ben's father, Patrick Gates, whom Ben has a strained relationship with thanks to years of failed treasure hunting that has created a rift between grandfather, father, and son. Finally, they travel around Philadelphia deciphering clues while avoiding both Ian and the FBI.

Step 7. Approach the Innermost Cave

The hero nears the goal of their quest, the reason they crossed the threshold in the first place. Here, they could be making plans, having new revelations, or gaining new skills. To put it in other familiar terms, this step would mark the moment just before the story's climax.

Ben uncovers a pivotal clue—or rather, he finds an essential item—a pair of bifocals with interchangeable lenses made by Benjamin Franklin. It is revealed that by switching through the various lenses, different messages will be revealed on the back of the Declaration of Independence. He's forced to split from Abigail and Riley, but Ben has never been closer to the treasure.

Step 8. The Ordeal

The hero faces a dire situation that changes how they view the world. All threads of the story come together at this pinnacle, the central crisis from which the hero will emerge unscathed or otherwise. The stakes will be at their absolute highest here.

Vogler details that in this stage, the hero will experience a "death," though it need not be literal. In your story, this could signify the end of something and the beginning of another, which could itself be figurative or literal. For example, a certain relationship could come to an end, or it could mean someone "stuck in their ways" opens up to a new perspective.

In National Treasure , The FBI captures Ben and Ian makes off with the Declaration of Independence—all hope feels lost. To add to it, Ian reveals that he's kidnapped Ben's father and threatens to take further action if Ben doesn't help solve the final clues and lead Ian to the treasure.

Ben escapes the FBI with Ian's help, reunites with Abigail and Riley, and leads everyone to an underground structure built below Trinity Church in New York City. Here, they manage to split from Ian once more, sending him on a goose chase to Boston with a false clue, and proceed further into the underground structure.

Though they haven't found the treasure just yet, being this far into the hunt proves to Ben's father, Patrick, that it's real enough. The two men share an emotional moment that validates what their family has been trying to do for generations.

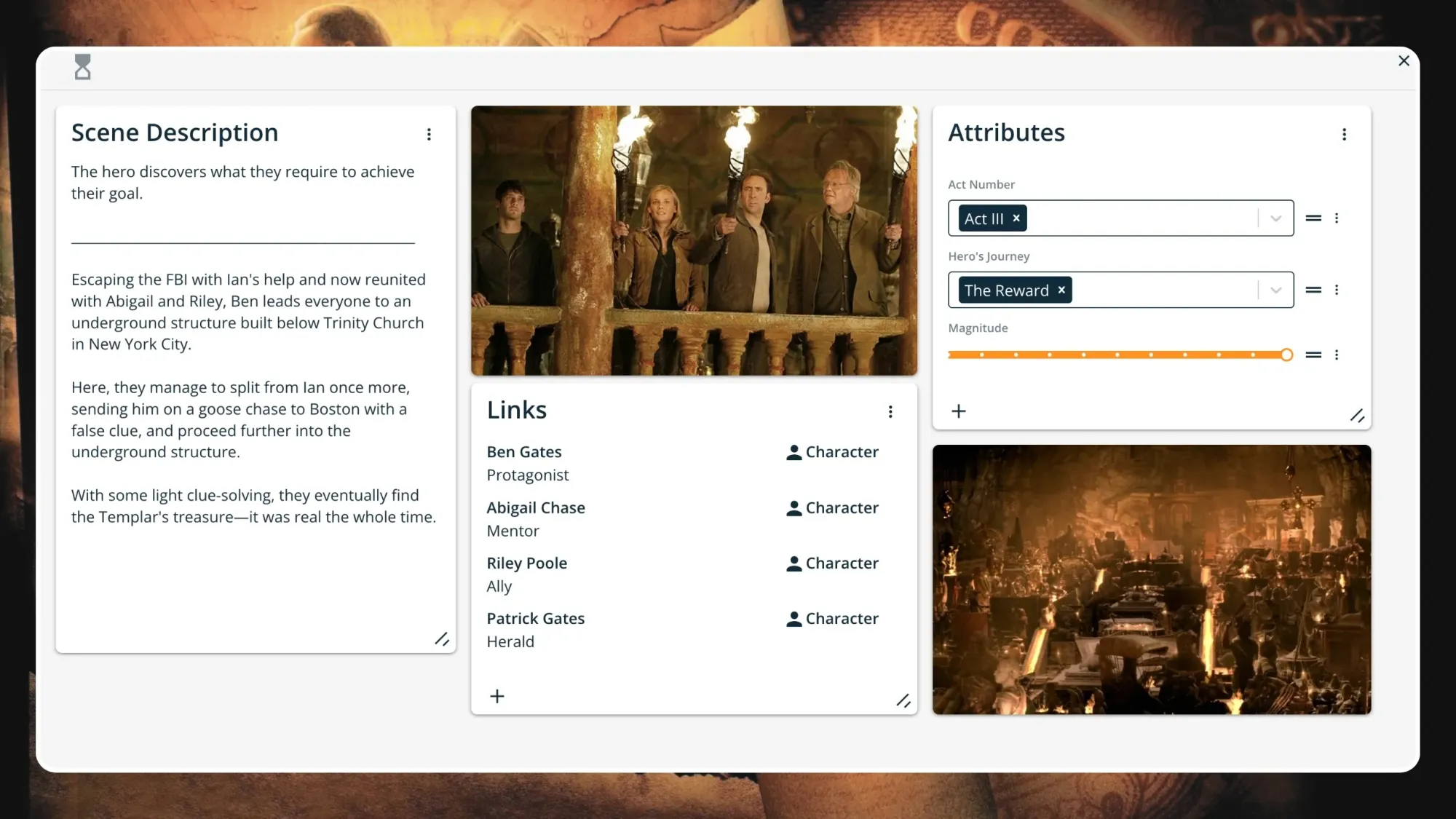

Step 9. Reward

This is it, the moment the hero has been waiting for. They've survived "death," weathered the crisis of The Ordeal, and earned the Reward for which they went on this journey.

Now, free of Ian's clutches and with some light clue-solving, Ben, Abigail, Riley, and Patrick keep progressing through the underground structure and eventually find the Templar's treasure—it's real and more massive than they could have imagined. Everyone revels in their discovery while simultaneously looking for a way back out.

Act Three: Return

Step 10. the road back.

It's time for the journey to head towards its conclusion. The hero begins their return to the Known World and may face unexpected challenges. Whatever happens, the "why" remains paramount here (i.e. why the hero ultimately chose to embark on their journey).

This step marks a final turning point where they'll have to take action or make a decision to keep moving forward and be "reborn" back into the Known World.

Act Three of National Treasure is admittedly quite short. After finding the treasure, Ben and co. emerge from underground to face the FBI once more. Not much of a road to travel back here so much as a tunnel to scale in a crypt.

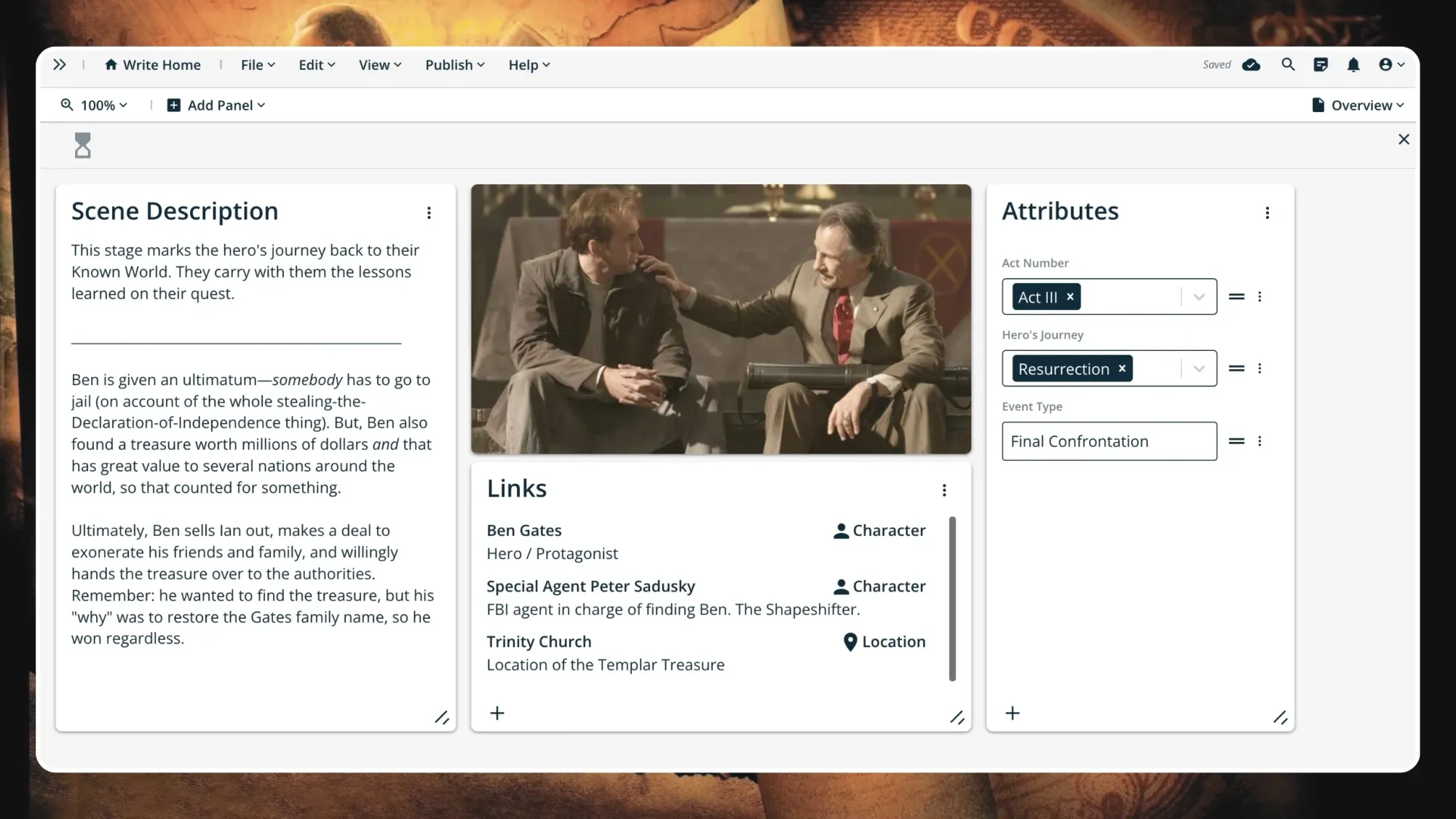

Step 11. Resurrection

The hero faces their ultimate challenge and emerges victorious, but forever changed. This step often requires a sacrifice of some sort, and having stepped into the role of The Hero™, they must answer to this.

Ben is given an ultimatum— somebody has to go to jail (on account of the whole stealing-the-Declaration-of-Independence thing). But, Ben also found a treasure worth millions of dollars and that has great value to several nations around the world, so that counts for something.

Ultimately, Ben sells Ian out, makes a deal to exonerate his friends and family, and willingly hands the treasure over to the authorities. Remember: he wanted to find the treasure, but his "why" was to restore the Gates family name, so he won regardless.

Step 12. Return With the Elixir

Finally, the hero returns home as a new version of themself, the elixir is shared amongst the people, and the journey is completed full circle.

The elixir, like many other elements of the hero's journey, can be literal or figurative. It can be a tangible thing, such as an actual elixir meant for some specific purpose, or it could be represented by an abstract concept such as hope, wisdom, or love.

Vogler notes that if the Hero's Journey results in a tragedy, the elixir can instead have an effect external to the story—meaning that it could be something meant to affect the audience and/or increase their awareness of the world.

In the final scene of National Treasure , we see Ben and Abigail walking the grounds of a massive estate. Riley pulls up in a fancy sports car and comments on how they could have gotten more money. They all chat about attending a museum exhibit in Cairo (Egypt).

In one scene, we're given a lot of closure: Ben and co. received a hefty payout for finding the treasure, Ben and Abigail are a couple now, and the treasure was rightfully spread to those it benefitted most—in this case, countries who were able to reunite with significant pieces of their history. Everyone's happy, none of them went to jail despite the serious crimes committed, and they're all a whole lot wealthier. Oh, Hollywood.

Variations of the Hero's Journey

Plot structure is important, but you don't need to follow it exactly; and, in fact, your story probably won't. Your version of the Hero's Journey might require more or fewer steps, or you might simply go off the beaten path for a few steps—and that's okay!

What follows are three additional versions of the Hero's Journey, which you may be more familiar with than Vogler's version presented above.

Dan Harmon's Story Circle (or, The Eight-Step Hero's Journey)

Screenwriter Dan Harmon has riffed on the Hero's Journey by creating a more compact version, the Story Circle —and it works especially well for shorter-format stories such as television episodes, which happens to be what Harmon writes.

The Story Circle comprises eight simple steps with a heavy emphasis on the hero's character arc:

- The hero is in a zone of comfort...

- But they want something.

- They enter an unfamiliar situation...

- And adapt to it by facing trials.

- They get what they want...

- But they pay a heavy price for it.

- They return to their familiar situation...

- Having changed.

You may have noticed, but there is a sort of rhythm here. The eight steps work well in four pairs, simplifying the core of the Hero's Journey even further:

- The hero is in a zone of comfort, but they want something.

- They enter an unfamiliar situation and have to adapt via new trials.

- They get what they want, but they pay a price for it.

- They return to their zone of comfort, forever changed.

If you're writing shorter fiction, such as a short story or novella, definitely check out the Story Circle. It's the Hero's Journey minus all the extraneous bells & whistles.

Ten-Step Hero's Journey

The ten-step Hero's Journey is similar to the twelve-step version we presented above. It includes most of the same steps except for Refusal of the Call and Meeting the Mentor, arguing that these steps aren't as essential to include; and, it moves Crossing the Threshold to the end of Act One and Reward to the end of Act Two.

- The Ordinary World

- The Call to Adventure

- Crossing the Threshold

- Tests, Allies, Enemies

- Approach the Innermost Cave

- The Road Back

- Resurrection

- Return with Elixir

We've previously written about the ten-step hero's journey in a series of essays separated by act: Act One (with a prologue), Act Two , and Act Three .

Twelve-Step Hero's Journey: Version Two

Again, the second version of the twelve-step hero's journey is very similar to the one above, save for a few changes, including in which story act certain steps appear.

This version skips The Ordinary World exposition and starts right at The Call to Adventure; then, the story ends with two new steps in place of Return With Elixir: The Return and The Freedom to Live.

- The Refusal of the Call

- Meeting the Mentor

- Test, Allies, Enemies

- Approaching the Innermost Cave

- The Resurrection

- The Return*

- The Freedom to Live*

In the final act of this version, there is more of a focus on an internal transformation for the hero. They experience a metamorphosis on their journey back to the Known World, return home changed, and go on to live a new life, uninhibited.

Seventeen-Step Hero's Journey

Finally, the granddaddy of heroic journeys: the seventeen-step Hero's Journey. This version includes a slew of extra steps your hero might face out in the expanse.

- Refusal of the Call

- Supernatural Aid (aka Meeting the Mentor)

- Belly of the Whale*: This added stage marks the hero's immediate descent into danger once they've crossed the threshold.

- Road of Trials (...with Allies, Tests, and Enemies)

- Meeting with the Goddess/God*: In this stage, the hero meets with a new advisor or powerful figure, who equips them with the knowledge or insight needed to keep progressing forward.

- Woman as Temptress (or simply, Temptation)*: Here, the hero is tempted, against their better judgment, to question themselves and their reason for being on the journey. They may feel insecure about something specific or have an exposed weakness that momentarily holds them back.

- Atonement with the Father (or, Catharthis)*: The hero faces their Temptation and moves beyond it, shedding free from all that holds them back.

- Apotheosis (aka The Ordeal)

- The Ultimate Boon (aka the Reward)

- Refusal of the Return*: The hero wonders if they even want to go back to their old life now that they've been forever changed.

- The Magic Flight*: Having decided to return to the Known World, the hero needs to actually find a way back.

- Rescue From Without*: Allies may come to the hero's rescue, helping them escape this bold, new world and return home.

- Crossing of the Return Threshold (aka The Return)

- Master of Two Worlds*: Very closely resembling The Resurrection stage in other variations, this stage signifies that the hero is quite literally a master of two worlds—The Known World and the Unknown World—having conquered each.

- Freedom to Live

Again, we skip the Ordinary World opening here. Additionally, Acts Two and Three look pretty different from what we've seen so far, although, the bones of the Hero's Journey structure remain.

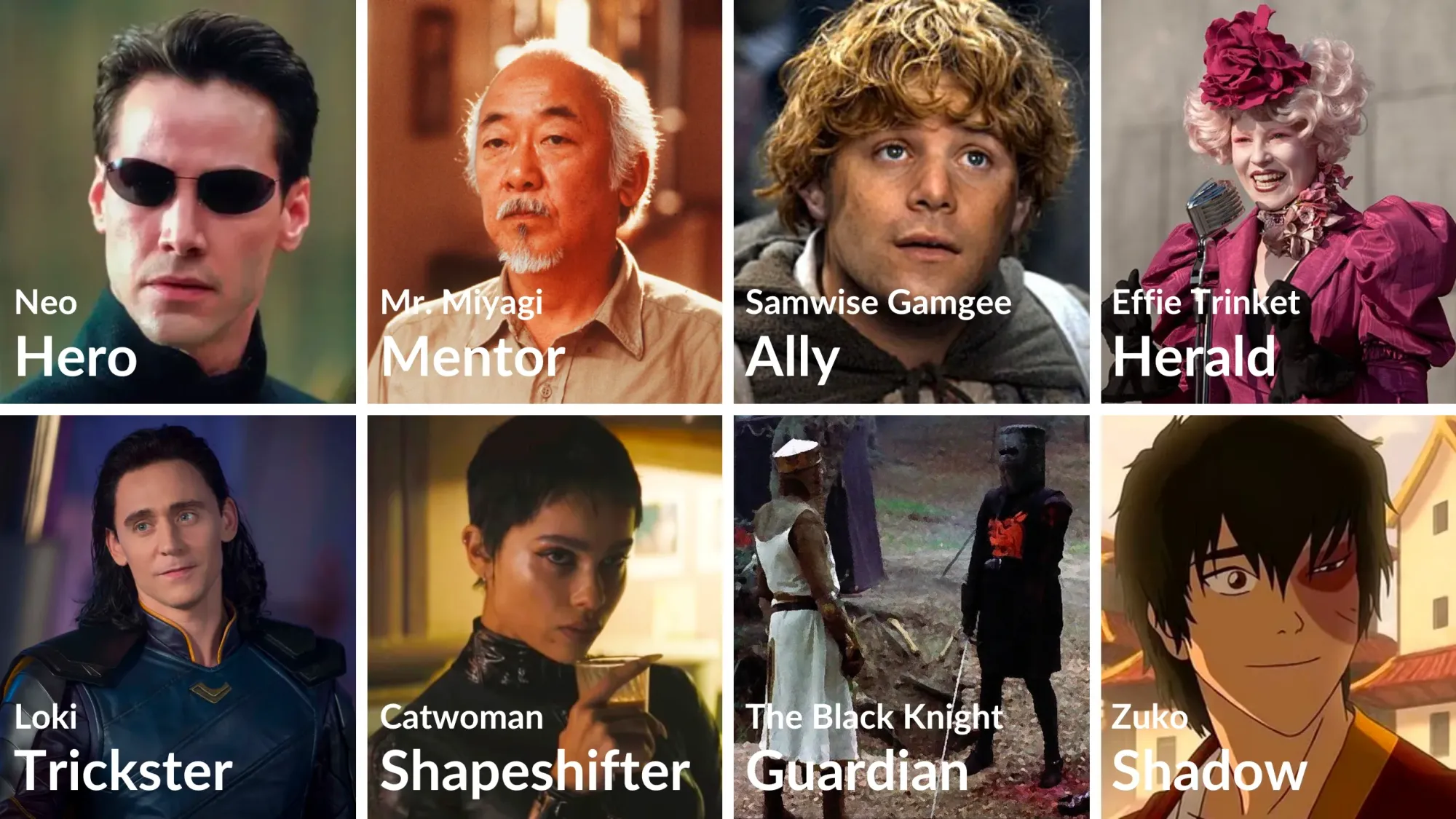

The Eight Hero’s Journey Archetypes

The Hero is, understandably, the cornerstone of the Hero’s Journey, but they’re just one of eight key archetypes that make up this narrative framework.

In The Writer's Journey , Vogler outlined seven of these archetypes, only excluding the Ally, which we've included below. Here’s a breakdown of all eight with examples:

1. The Hero

As outlined, the Hero is the protagonist who embarks on a transformative quest or journey. The challenges they overcome represent universal human struggles and triumphs.

Vogler assigned a "primary function" to each archetype—helpful for establishing their role in a story. The Hero's primary function is "to service and sacrifice."

Example: Neo from The Matrix , who evolves from a regular individual into the prophesied savior of humanity.

2. The Mentor

A wise guide offering knowledge, tools, and advice, Mentors help the Hero navigate the journey and discover their potential. Their primary function is "to guide."

Example: Mr. Miyagi from The Karate Kid imparts not only martial arts skills but invaluable life lessons to Daniel.

3. The Ally

Companions who support the Hero, Allies provide assistance, friendship, and moral support throughout the journey. They may also become a friends-to-lovers romantic partner.

Not included in Vogler's list is the Ally, though we'd argue they are essential nonetheless. Let's say their primary function is "to aid and support."

Example: Samwise Gamgee from Lord of the Rings , a loyal friend and steadfast supporter of Frodo.

4. The Herald

The Herald acts as a catalyst to initiate the Hero's Journey, often presenting a challenge or calling the hero to adventure. Their primary function is "to warn or challenge."

Example: Effie Trinket from The Hunger Games , whose selection at the Reaping sets Katniss’s journey into motion.

5. The Trickster

A character who brings humor and unpredictability, challenges conventions, and offers alternative perspectives or solutions. Their primary function is "to disrupt."

Example: Loki from Norse mythology exemplifies the trickster, with his cunning and chaotic influence.

6. The Shapeshifter

Ambiguous figures whose allegiance and intentions are uncertain. They may be a friend one moment and a foe the next. Their primary function is "to question and deceive."

Example: Catwoman from the Batman universe often blurs the line between ally and adversary, slinking between both roles with glee.

7. The Guardian

Protectors of important thresholds, Guardians challenge or test the Hero, serving as obstacles to overcome or lessons to be learned. Their primary function is "to test."

Example: The Black Knight in Monty Python and the Holy Grail literally bellows “None shall pass!”—a quintessential ( but not very effective ) Guardian.

8. The Shadow

Represents the Hero's inner conflict or an antagonist, often embodying the darker aspects of the hero or their opposition. Their primary function is "to destroy."

Example: Zuko from Avatar: The Last Airbender; initially an adversary, his journey parallels the Hero’s path of transformation.

While your story does not have to use all of the archetypes, they can help you develop your characters and visualize how they interact with one another—especially the Hero.

For example, take your hero and place them in the center of a blank worksheet, then write down your other major characters in a circle around them and determine who best fits into which archetype. Who challenges your hero? Who tricks them? Who guides them? And so on...

Stories that Use the Hero’s Journey

Not a fan of saving the Declaration of Independence? Check out these alternative examples of the Hero’s Journey to get inspired:

- Epic of Gilgamesh : An ancient Mesopotamian epic poem thought to be one of the earliest examples of the Hero’s Journey (and one of the oldest recorded stories).

- The Lion King (1994): Simba's exile and return depict a tale of growth, responsibility, and reclaiming his rightful place as king.

- The Alchemist by Paolo Coehlo: Santiago's quest for treasure transforms into a journey of self-discovery and personal enlightenment.

- Coraline by Neil Gaiman: A young girl's adventure in a parallel world teaches her about courage, family, and appreciating her own reality.

- Kung Fu Panda (2008): Po's transformation from a clumsy panda to a skilled warrior perfectly exemplifies the Hero's Journey. Skadoosh!

The Hero's Journey is so generalized that it's ubiquitous. You can plop the plot of just about any quest-style narrative into its framework and say that the story follows the Hero's Journey. Try it out for yourself as an exercise in getting familiar with the method.

Will the Hero's Journey Work For You?

As renowned as it is, the Hero's Journey works best for the kinds of tales that inspired it: mythic stories.

Writers of speculative fiction may gravitate towards this method over others, especially those writing epic fantasy and science fiction (big, bold fantasy quests and grand space operas come to mind).

The stories we tell today are vast and varied, and they stretch far beyond the dealings of deities, saving kingdoms, or acquiring some fabled "elixir." While that may have worked for Gilgamesh a few thousand years ago, it's not always representative of our lived experiences here and now.

If you decide to give the Hero's Journey a go, we encourage you to make it your own! The pieces of your plot don't have to neatly fit into the structure, but you can certainly make a strong start on mapping out your story.

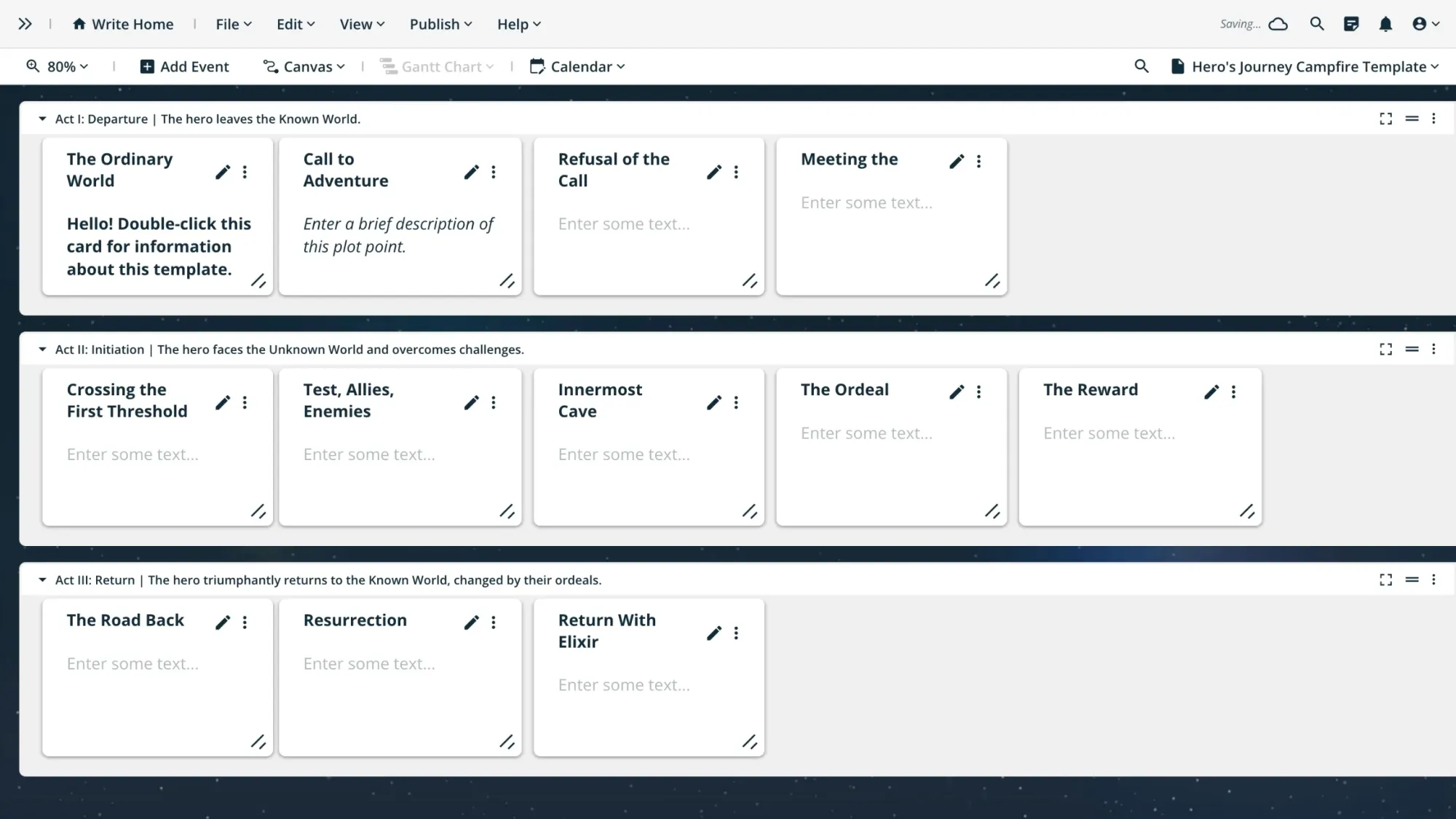

Hero's Journey Campfire Template

The Timeline Module in Campfire offers a versatile canvas to plot out each basic component of your story while featuring nested "notebooks."

Simply double-click on each event card in your timeline to open up a canvas specific to that card. This allows you to look at your plot at the highest level, while also adding as much detail for each plot element as needed!

If you're just hearing about Campfire for the first time, it's free to sign up—forever! Let's plot the most epic of hero's journeys 👇

Lessons From the Hero’s Journey

The Hero's Journey offers a powerful framework for creating stories centered around growth, adventure, and transformation.

If you want to develop compelling characters, spin out engaging plots, and write books that express themes of valor and courage, consider The Hero’s Journey your blueprint. So stop holding out for a hero, and start writing!

Does your story mirror the Hero's Journey? Let us know in the comments below.

- Scriptwriting

Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey: A Better Screenplay in 17 Steps

- What is a Scene

- What is The Three Act Structure

- What is Story Structure

- What is a Story Beat

- What Is a Plot

- Plot vs Story

- What is a Non-Linear Plot

- What is a Plot Device

- What is Freytag’s Pyramid

- Screenplay Structure Examples

- What is a Story Mountain

- Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey

- What is Save the Cat

- Dan Harmon’s Story Circle

- What is Aristotle’s Poetics

- What is Exposition

- What is an Inciting Incident

- What is Rising Action

- What is the Climax of a Story

- What is the Falling Action

- What is Denouement

- How to Write the First Ten Pages of a Screenplay

- Plot Structure Tools

- The Ultimate Film Beat Sheet

- Secrets to Great Exposition in Screenwriting

- Writing Exposition in Film

- Best Inciting Incident Examples

- Examples of Midpoint In Movies

- Write Your Script For Free

dds are that if you’ve had any interest in writing a script within the past fifty years you’ve heard of the Hero’s Journey. A writer you got drinks with swore by it, a film professor suggested you read about it. Or you overheard the barista at your local coffee shop talking about how Die Hard is a picture-perfect template for it. But… what is it? I’ll explain all of the Hero’s Journey’s 17 steps and provide examples in the modern canon. Then you can kick writer’s block and get a strong script into the hands of agents and producers.

Watch: The Hero's Journey Explained

Subscribe for more filmmaking videos like this.

- Call to Action

- Refusal of Call

- Supernatural Aid

- Crossing The Threshold

- Belly of the Whale

- The Road of Trials

- Meeting the Goddess

- Atonement With the Father

- The Ultimate Boon

- Refusal of Return

- Magic Flight

- Rescue from Without

- Crossing the Return Threshold

- Master of Two Worlds

- Freedom to Live

Hero’s Journey Examples

The monomyth featuring three of your favorite franchises!

The hero's journey begins, 1. call to action.

Adventure is calling. Will your hero pick up?

The initial step in the first act of the Hero’s Journey - known as the departure - is the “call to action." The Hero is beckoned to go on a journey. Think Frodo Baggins meeting Gandalf. Or the Owl inviting Harry Potter to Hogwarts.

If having a tall wizard extend a hand may be a little too on the nose for you, don't worry. This comes in all forms. In Citizen Kane , the mystery surrounding Charles Foster Kane’s final words is the call to action for the reporter, Jerry Thompson, to get to work.

The Hero Hesitates

2. refusal of call.

Next is the Hero’s “refusal of call.” The Hero initially balks at the idea of leaving their lives. The Shire is beautiful, after all, who wants to embark on a dangerous journey across the world?

This refusal is typically because of a duty or obligation they have at home. Be it family, or work, it’s something our Hero cares deeply about. But, as pressure mounts, they eventually succumb and decide to leave with the help of “supernatural aid.”

The Hero Receives Assistance

3. supernatural aid.

Once the Hero has committed themselves to embarking on whatever that quest may be (keep in mind, a Hero’s Journey can apply to a modern, emotional story, as well), they receive “supernatural aid.”

Individuals give the Hero information or tools at the start of their journey to help their chances of completing the task. Rome wasn’t built in a day, and it definitely wasn’t built alone. Every hero has a set of allies helping them get the job done. From Luke, Han, and Chewie to Harry, Ron, and Hermoine, these teams are iconic and nearly inseparable.

The tools provided come in handy as the Hero begins…

The Hero Commits

4. crossing the threshold.

Now the hero ventures into a new, unfamiliar world where the rules and dangers are unknown. They’re not in Kansas anymore, Toto, and that becomes evidently clear when monkeys start flying.

This stage often requires a few examples to crystalize the change in environment from familiar to dangerous. The contrast is key to play up how ill-prepared they initially are.

The Hero is Challenged

5. belly of the whale.

Next thing you know, we're in “the belly of the whale.” The first point of real danger in the Hero’s Journey. Taken from the Biblical story of Jonah entering a literal whale’s belly, it’s here that the dangers we’ve been warned about are manifested into tangible characters. Like hungry Orcs with swords.

This is Jonah moments before actually being in the belly of the whale.

Now our Hero must make a decision to continue and, in turn, undergo a personal metamorphosis in the process.

They will not be the same individual at the end of this tale as they were in the beginning. This must be made clear while in the belly of the whale, as we enter Initiation, or act two. Which is the longest slice of the Hero’s Journey pie.

This part is filled with the most failure and risk, and ends with the climax. But first, it starts with...

The Hero is Tested

6. the road of trials.

“Road of trials” is a set of three tests that the Hero must take. Usually they will fail at least one of these tests. This could be a montage. It could also be a series of obstacles leading to a smaller goal in the journey.

Here is where the Hero learns to use his or her tools and allies while on their way to a...

The Great Advisor

7. meeting the goddess.

At this point in the monomyth, our Hero needs a break to adjust perspective and digest the ways they've changed. It’s here that they meet with an advisor, or a trusted individual, who will help them gain a better insight into the next steps of the journey. Frodo met with Galadriel, an elf who enlightened him with visions of potential futures.

This is Frodo meeting with the goddess

Luke met Leia, and the two formed of a bond of kinship, motivating them to commit more to their cause. This individual doesn’t have to be a woman, but whoever it is our hero will gain something from the wisdom they impart.

But no good deed goes unpunished, and as we reward our Heroes in storytelling, we must also tempt them to failure.

The Hero is Torn

8. temptation.

Much like “road of trials,” “temptation” is a test in the Hero’s Journey. It presents a set of, well… temptations... that our Hero must either overcome or avoid. These temptations pick and pull at the insecurities of the Hero. A microcosm can be found in our own everyday lives with the simple act of getting out of bed.

The temptation to stay in the cozy confines of our comforters (and comfort zones) can be strong and sometimes overwhelming. This must be manifested in our story with some type of a cheap way out. Or an opportunity to throw in the towel. Our Hero must decline and press forward, nobly facing danger.

A Moment of Catharsis

9. atonement with the father.

Once they’ve thrown away their temptations, the Hero enters the “atonement with the father.” This is always an emotional part of the Hero’s Journey. It's a point in the monomyth where our protagonist must confront an aspect of their character from act one that has been slowing them down.

Something that could be fatal to their journey in the coming climactic stages. While this is actuated as a confrontation with a male entity, it doesn’t have to be.

The point here is that the Hero finds within themselves a change from who they were into someone more capable. Harry has to reconcile with the loss of his father figure, Dumbledore. Now take on Voldemort alone, using the lessons he’s learned on the way. Just like Luke...and every other hero ever. This is the emotional climax of the story.

"Tell your sister... you were riiiiiiiiiight..."

Death of the hero, 10. apotheosis.

With a new sense of confidence and clarity we must then make our Hero deal with “apotheosis.” This is the stage of the Hero’s Journey where a greater perspective is achieved. Often embodied by a death of the Hero’s former self; where the old Frodo has died and the new one is born.

But this is sometimes interpreted as a more “a-ha!” moment — a breakthrough that leads to the narrative’s climax. This, too, can be tied to the death of Dumbledore and Harry’s reconciliation with the loss. This step is usually the final motivator for the Hero, driving the story into...

THe Hero Victorious

11. the ultimate boon.

This monomyth step is the physical climax of the story. This is often considered the MacGuffin of a film — the physical object that drives our Hero’s motivation. But it's a MacGuffin, to use Hitchcock's famous term, because ultimately... it doesn't matter.

In Pulp Fiction , we never find out what’s in the briefcase, but it’s the briefcase that led them on the wild journey. When we find out what “Rosebud” actually means, it simply forms a lynchpin to help us understand who Charles Foster Kane was. The mission is accomplished and the world can rest easy knowing that it is safe from evil.

The Hero's Journey Home

12. refusal of return.

Upon a successful completion of the Hero’s Journey, and a transformation into a different person, the Hero has a “refusal to return.” The Shire seems so boring now and the last thing Harry wants is to go back to that drawer under the stairs.

And, oftentimes, the return can be just as dangerous. This is the beginning of the third act of Campbell’s Hero’s Journey (known as the Return) and, while shorter, should still contain conflict. Our next step is an opportunity for that...

The Hero Transported

13. magic flight.

This is the point in the Hero’s Journey where they must get out alive, often requiring the help of individuals they met along the way. Dorothy still has to get back to Kansas, the solution to which may seem like a leap of faith.

The eagles rescue from without with a magic flight to Frodo and friends

The hero's rescue, 14. rescue from without.

Bringing us to the “rescuers from without” point in the monomyth. Just because Frodo destroyed the one ring to rule them all doesn’t mean he gets a free ride back to the Shire. Remember those giant eagles we met a while back in act two? Well their back just in time!

Homeward Bound

15. crossing the return threshold.

Once the Hero is back home, it’s time to acknowledge their change in character. “Crossing the return threshold” is the stage in the monomyth where the hero has left the chaos of the outer world and return home.

But it's hard to adjust to the old world. Remember that scene where Frodo tried to enjoy a beer back at the shire? Hard to go back to normal when you essentially live with Dark Lord PTSD.

A Triumphant Return

16. master of two worlds.

The hero survived an adventure in the chaos realm, and now survives in the normal order realm. This makes him or her the master of two worlds. Not many people come back and live to tell the tale.

Frodo and Gandalf wandering off into the sunset post accomplishing their mission

Plus which, throughout the story, they’ve become someone much more capable and resilient than they were in act one. They've learned lessons, and brought what they learned home with them.

Whatever issues they may have had before embarking on this chaotic tale (often the ones preventing from taking the call to action) now pale in comparison with what they’ve been through.

It’s easier to deal with your annoying cousin, Dudley, after you’ve defeated Voldemort. This, in turn, leads to...

The New Status Quo

17. freedom to live.

In many ways the Hero's Journey is about death and rebirth. The story may manifest as the death of an aspect of character, and the birth of some new way of life. But the metaphor behind any story is one about mortality.

Change is constant. Hero's living through the Hero's Journey are models for us. Models that we can travers the constant change of existence, face our mortality, and continue. In a religious sense, and religions are all part of the monomyth, this is about the eternal spirit.

Look no farther than the prayer of St. Francis to understand this final step in the Hero's quest. "It is in dying that we are born to eternal life."

The Hero’s Journey Concludes

Cinematic heroes.

The monomyth is practically ubiquitous in Hollywood. As you’ve read earlier, Harry Potter , Star Wars , Lord of the Rings , and Citizen Kane all follow the Hero’s Journey. But, because this concept was built upon the foundations of major mythologies, it's truly a "tale as old as time."

Because Campbell discovered the Hero's Journey. He didn't make it up. Neither did those older myths. He realized as an anthropologist, that every culture all around the globe had the same story beats in all their myths.

Sure, some myths, and some movies, use 10 of the 17, or even just 5. But throughout human history, around the world, these story beats keep showing up. In cultures that had nothing to do with one another.

The Hero's Journey is a concept innate to being human.

And if remembering these 17 steps may seem a little daunting, fear not. Make sure to check out Dan Harmon's abridged 8-step variation of the Hero's Journey monomyth. Same structure, just made more digestible.

Dan Harmon’s Story Circle

Practically speaking, the Hero’s Journey is an excellent tool for structuring an outline in a clear and familiar way. It has the power to make your script much more powerful and emotionally resonant.

It’s circular, allowing for repeat adventures (which works well if you're learning how to write a TV pilot ) and each aspect drives the hero to the next. From the Goddess, the Hero finds temptation. From reconciling with the father, the Hero is now prepared for the final boon.

Story Circle • 8 Proven Steps to Better Stories

Using a Hero’s Journey worksheet can help you write a treatment or create a well-structured outline , which is a valuable tool for creating a strong first draft.

By putting in the 17 steps of the Hero’s Journey before building the outline, you can ensure that the writing process will flow smoothly and efficiently. Let us know in the comments how the monomyth has helped you craft a story that escalates with every beat to an exciting climax.

Up Next: Dan Harmon's Story Circle →

Write and produce your scripts all in one place..

Write and collaborate on your scripts FREE . Create script breakdowns, sides, schedules, storyboards, call sheets and more.

- Pricing & Plans

- Product Updates

- Featured On

- StudioBinder Partners

- The Ultimate Guide to Call Sheets (with FREE Call Sheet Template)

- How to Break Down a Script (with FREE Script Breakdown Sheet)

- The Only Shot List Template You Need — with Free Download

- Managing Your Film Budget Cashflow & PO Log (Free Template)

- A Better Film Crew List Template Booking Sheet

- Best Storyboard Softwares (with free Storyboard Templates)

- Movie Magic Scheduling

- Gorilla Software

- Storyboard That

A visual medium requires visual methods. Master the art of visual storytelling with our FREE video series on directing and filmmaking techniques.

We’re in a golden age of TV writing and development. More and more people are flocking to the small screen to find daily entertainment. So how can you break put from the pack and get your idea onto the small screen? We’re here to help.

- Making It: From Pre-Production to Screen

- What is Film Distribution — The Ultimate Guide for Filmmakers

- What is a Fable — Definition, Examples & Characteristics

- Whiplash Script PDF Download — Plot, Characters and Theme

- What Is a Talking Head — Definition and Examples

- What is Blue Comedy — Definitions, Examples and Impact

- 299 Facebook

- 238 Pinterest

- 12 LinkedIn

- Apr 11, 2022

Visual Storytelling: Introduction: The Hero's Journey

The Hero´s Journey

Carl Jung famously theorizes that myths are none other than the dreams of the collective mind. He went to demonstrate this idea by noting how all dreams and myths in history are populated by the same heavily standardized figures, which he called archetypes. He believed these characters and the roles they play, in every collective story and individual dream, were common to the entire human species because they were bequeathed through the collective unconscious. Based on his reasoning, these types, each with their epitomized attributes, are a prosopopoeia of all the parts of ourselves who live in the penumbra of our psyche.

A few decades later, Joseph Campbell, an expert in comparative mythology and religion, tries to further develop Jung’s theory. In his book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, he analyses a plethora of ancient myths and stories from every corner of the earth through the lens of the archetypes’ argument and finally demonstrates the constant existence of several identifiable figures in all epic and legendary narratives. There are numerous archetypes, but Campbell ascertained that there are a few notable stronghold figures, such as 'the Hero', 'the Mentor', 'the Shadow', 'the Shapeshifter', 'the Ally' and 'the Trickster'. He however took his analysis a step further as he found that there is a specific template guiding the design of stories which almost resembles a planned script. The protagonists, he noticed, all follow a similarly-paced heroic path; every hero faces akin challenges in the same order and with undeniably similar timing. He defined the cornerstones of the Hero’s adventure, effectively discovering the lines of a pattern which he named ' The Hero’s Journey' .

Campbell’s theories, on the common universal structure of every tale, myth, story and narration, became a crucial axiom in the artistic field. The delineation of this narrative framework, which Campbell considered to be “[…] a blueprint to leading an audience through a profound, transformative experience” (1949, p.14), gained the essential role of becoming a pillar for cinematographic and visual screenwriting.

The screenplay-oriented guide to the Hero’s Journey is definitely laid down by Christopher Vogler in his book, The Writer’s Journey . He sums up both Jung and Campbell’s theories and he proves that movies and television products, just as plays, fairy tales and epic sagas, have unconsciously maintained the portrayal of these archetypes and the narrative structure of the Hero’s Journey (Vogler, 2007, p. XXVII).

Vogler arranges the phases of this path in the classical Aristotelian three-act structure in order to make the scheme more comprehensible from a screenwriting angle.

Act One normally opens the curtains on the 'Ordinary World'; the reality in which the Hero has been living their entire life. This phase is set to illustrate, in the sharpest and quickest way possible, all we need to know about our hero's inner and outer life: their background, what their values are, what their life has consisted of thus far, the people they love and the sacrifices they are willing to make. The Ordinary World is a safe, monotonous, space, short of any possible challenge and a familiar ground which represents a comfort zone.

At times, the first act is actually preceded by a prologue. This is an external piece of the narration that may inform the audience about possible past or parallel events that are or will be an integral part of the tale. In the series Game of Thrones, the scene shown in the first few minutes of the pilot episode is of a group of men from the Night’s Watch who find themselves face to face with the threat of the White Walkers. At this point in time, neither the public nor the characters are aware of the fact that the White Walkers will be the greatest and ultimate forthcoming enemy of the entire story. The scene following is, in fact, an immediate presentation of the Ordinary World as the viewer is introduced to the Stark family in their normal everyday life at Winterfell, and the connection to the prologue remains vague and to be defined as the show goes on.

The first act comes to a turning point with 'The Call to Adventure'. This is the moment the Hero receives the call that will get the story rolling. This proposal may come in any form, whether it be through a messenger, a sudden discovery, a personal revelation or a stirring within the Hero’s inner moral code. The one fixed purpose of this phase is for the Hero to be presented with a request to leave their world and venture into the unknown, which will actively shatter their perception of reality.

The Hero at this point is either forced into the adventure or has to ponder whether to leave his simple but somehow comfortable life for a perilous and foreign environment. Sometimes, when he firstly rejects this call, there is an intermediate step called 'Refusal of the Call'. It is and emblematic moment for the audience to understand that the adventurous feat is not a trivial enterprise, but a high-stakes wager that could lead the Hero to lose his life or fortune (Vogler, 2017, pp.107-108). The Hero’s fear and reluctance helps the viewer to sympathize with their flawed, recognizable human traits.

Before making the final decision, the Hero meets with the Mentor, one of the main archetypes of every story. The Mentor, whether their deep knowledge be because of their own past experience or because of a special talent, tries to assist the Hero in their quest to find the right path, and often reminds them that the answers they seek are already clear. The Hero is necessarily faced with the realization that they must go into action, which leads them to the final step of Act One, called 'Crossing the First Threshold'. At this point in the story, the Hero commits wholeheartedly to the pursuit. Very often, this moment is defined by the literal crossing of a physical barrier towards the Special World, like doors, gates, or arches. (Vogler, 2007, pp.129-130).

The transition between Act One and Act Two, which in old movies is often signalled by a brief fade-out and is equivalent to the curtain coming down during a play, is strikingly noticeable. There is a drastic shift in energy and, most importantly, in pacing, as the Hero finally enters the Special World.

The purpose of this period of adjustment to the Special World is testing the first phase of Act Two. The Hero is put through a series of trials and ordeals that are intended to prepare them for the greatest challenges ahead. These tests, meant to train the Hero and subtly inform them on how to deal with the unfamiliar situation, are often difficult, but they do not have the life-threatening connotation that characterizes the final ordeal. Normally the Hero takes this time to understand and identify who their allies or potential enemies will be.

In the movie Hunger Games , when Katniss Everdeen enters the Special World, in this case Capitol City, she undergoes a series of tests before entering the Arena, where she will unavoidably have to battle death. She has to meet the other participants, give interviews, prove her skills in front of the committee charged to give her a vote. These tasks are disguised as preparations and evaluations for her entering the Games, but from a narrative point of view, they are meant to sharpen her understanding of her strengths and weaknesses, of what the intricate structure of this reality actually is, of who she can or cannot trust, and how to use to her own advantage the inner workings of the environment.

From this moment on, during the so-called Approach, the Hero prepares for the apogee of Act Two: The Ordeal. This is ultimate challenge that they have been bracing to face all along. The Ordeal is the final showdown between the Hero and their enemy, the Shadow; it is aimed to lead the Hero to confront, not only outside forces, but their own inner demons. It is the battle the tale is based on, and the common factor in all its adaptations is that the Hero has to encounter Death, whether it be literal, metaphorical or both. They need to come to terms with the ultimate demise of their old self, so that they can be reborn as an improved and wiser version.

After surviving the battle, the Hero and the Allies enter the last stage of Act Two, the Reward, which usually consists of a celebration. The evil has been slain, the Hero has conquered death and triumphed and both the protagonists and the audience need a loosening of the tensions amassed during the trials. The Reward, however, can also be comprised of the moment the Hero retrieves a price, a valuable item that, most of the time, is held in the hands of the now-defeated Shadow. This boon can be physical as a treasure or a person who needed to be rescued, but it can also be metaphorical, as a prized lesson the Hero is required to assimilate.

The first phase of Act Three, 'The Road Back', is a fundamental threshold, as it marks the return to the Ordinary World, the setting the Hero used to consider familiar and safe. The experiences the Hero lived during the journey, however, have fundamentally changed them to their core, as their understanding of reality has now exponentially grown in width. This different and more nuanced version of the Hero shows its true colours during The Resurrection, as they deal with the final steps of rebirth and purification, re-aligning their new enriched self with the person they were when the story begun.

The final step, 'The Return with The Elixir', or denouement, is the moment where all the knots of the story are untied or come undone, as everything gets solved in order to restore a sense of balance. It can mainly be presented in two ways; in the closed or circular ending, the Hero seems content with returning back in the Ordinary World, sharing their new-found knowledge with everyone else, and matter-of-factly closing the circle of the narration as they return to the beginning of the First Act. The open-ended form, instead, leaves the audience with some ambiguities and unresolved tensions, or, more drastically, with a final crucial question. In this ending, the storytelling goes on after the story is over, as it requires the audience to actively wonder about what the real conclusion might have been.

An extreme example of an open ending, which leaves the audience not only to question what could have happened next but also to re-evaluate the entire point of view of the story, is the conclusion of the movie Shutter Island , by Martin Scorsese. In the final minutes, after numerous tribulations, the main character, who the audience believes at this point to be clinically insane, poses a staggering question that in just a few seconds can possibly subvert the interpretation of the entire story. The audience has no choice but to ponder what the real truth is, entirely on their own.

The Hero’s journey evidently defines, at least to an elemental level, the basis of most of the narrative structure of human-made stories. The psychological component of this path and these archetypes are fundamental to understanding how humanity has collectively come to define such specific rules and stages of this journey. It can be said that the Hero’s journey is none other than the projection of human perception of life as a series of steps that lead to a continuous cycle of rebirth. The Hero’s courage and fortitude, along with their more flawed human traits, is an emblem of people’s will to conquer their own fears and, ultimately, death. It is also crucial to underline that each archetype is not necessarily a single character playing the same role in the entire story, as they represent nothing more than the various faces of humans’ personality. A Hero can as easily become a Shadow, an Ally can give advice and temporarily take the mantle of a Mentor, and a Shadow can be the Hero of their own story. The shifting adapting nature of these Archetypes renders them comparable to stage masks that actors wear during a performance. They are definite and primal roles, but as they merely represent all sides of human nature. They can, in every form of narration, be interchangeable.

Bibliographical sources

Campbell, J. (1949) The Hero with a Thousand Faces (Kindle Version). Retrieved from Amazon.it

Schanzer, E. ; Vitolo, A. (1977) Gli Archetipi dell'Inconscio Collettivo. (C. G. Jung, Trans.) . Turin: Editore Boringhieri S.p.a.

Vogler, C. (2007) The Writer's journey: mythical structure for writers (Third Edition) . Los Angeles: Michael Wiese Productions.

Visual Sources

Antiope Group (The), Hydria with the chariot of Achilles dragging the corpse of Hector, 510 - 520 B.C.

https://bit.ly/3LNptIg

Christopher Vogler. Schematic illustration. Retrieved from The Writer's journey: mythical structure for writers (Third Edition).

Johnson, R.(2017). Star Wars: Episode VIII - The Last Jedi [Photo] https://bit.ly/3DTvxML

Lucas, G. (1977). Star Wars: Episode IV - a New Hope [Photo] Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3KonMk5

Ross, G. (2012). Hunger Games. [Photo] https://bit.ly/3KFBP5j

Scorsese, M. (2010). Shutter Island . [Photo] Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3JodP54

- Cinematography

Elena Maiolini

Arcadia, has many categories starting from Literature to Science. If you liked this article and would like to read more, you can subscribe from below or click the bar and discover unique more experiences in our articles in many categories

Let the posts come to you.

Thanks for submitting!

The Hero’s Journey: 12 Steps That Make Up the Universal Structure of Great Stories

by David Safford | 0 comments

At some in your writer's life, you've probably come across the term Hero's Journey. Maybe you've even studied this guide for storytelling and applied it to your own books—and yet, something about your own application felt off. You wanted to learn more, but didn't know where to start.

Maybe you needed a resource that would simplify the hero's journey steps and all the other major details instead of complicate them.

The Hero's Journey is as old as humanity itself. And through history, this single story form has emerged over and over again. People from all cultures have seemed to favor its structure, and its familiar types of characters (archetypal hero, anyone?), symbols, relationships, and steps.

If you want to build or strengthen your writing career and win a following of many happy readers, you want this particular tool in your writer's toolbox.

Let's dive in.

Need help applying The Hero's Journey to your story outline and manuscript? Download this free Hero's Journey worksheet now!

Why I Love the Hero's Journey (And You Will, Too)

Like many, I grew up loving Star Wars. I especially loved the music and bought the soundtracks at some point in middle school. When my parents weren't home and I had the house all to myself, I'd slip one of the CDs into my stereo, crank the volume up, and blast the London Symphony Orchestra. I even pretended I was conducting the violins and timpani myself.

I know it's nerdy to admit. But we love what we love, and I love the music of great movies.

In a way, the Hero's Journey is like a soundtrack. It follows familiar beats and obeys age-old principles of human emotion. We can't necessarily explain why a piece of music is so beautiful, but we can explain what it does and simply acknowledge that most people like it.

As I've come to understand Joseph Campbell's groundbreaking monomyth theory, commonly known as the Hero's Journey, I've fallen deeper and deeper in love with it.

But it's important to make sure you know what it is, and what it isn't.

The Hero's Journey isn't a formula to simply follow, plugging in hackneyed characters into cliched situations.

It's not “selling out” and giving up your artistic integrity

The Hero's Journey is a set of steps, scenes, character types, symbols, and themes that tend to recur in stories regardless of culture or time period. Within these archetypes are nearly infinite variations and unique perspectives that are impacted by culture and period, reflecting wonderful traits of the authors and audiences.

Also, the Hero's Journey is a process that your reader expects your story to follow, whether they know it or not. This archetype is hard-wired into our D.N.A. Let's look at how to use it to make your own stories stronger.

How to Use This Hero's Journey Post

In the beginning, there were stories. These stories were told by mothers, soldiers, and performers. They were inscribed on the walls of caves, into tablets of stone, and on the first sheets of papyrus.

This is how the Hero's Journey was born.

In this post, I'll walk you through the Hero's Journey twelve steps, and teach you how to apply them into your story. I'll also share additional resources to teach you some other Hero's Journey essentials, like character archetypes, symbols, and themes. By the end of this post, you'll be able to easily apply the Hero's Journey to your story with confidence.

And don't skip out on the practice exercise at the end of the post! This will help you start to carve out the Hero's Journey for your story with a practical fifteen minute exercise—the best way to really retain how the Hero's Journey works is to apply it.

Table of Contents: The Hero's Journey Guide

What is the Hero's Journey?

Why the Hero's Journey will make you a better writer

The Twelve-Step Hero's Journey Structure

- The Ordinary World

- The Call to Adventure

- The Refusal of the Call

- Meeting the Mentor

- Crossing the Threshold

- Trials, Allies, and Enemies

- The Approach

- The Road Back

- The Resurrection

- Return With the Elixir

5 Essential Hero's Journey Scenes

A Guide to Structuring Your Hero's Journey

Bonus! Additional Hero's Journey Resources

- 5 Character Archetypes

- 5 Hero's Journey Symbols

- 5 Hero's Journey Themes

What Is the Hero's Journey?

The Hero's Journey is the timeless combination of characters, events, symbols, and relationships frequently structured as a sequence of twelve steps. It is a storytelling structure that anyone can study and utilize to tell a story that readers will love.

First identified and defined by Joseph Campbell, the Hero's Journey was theorizied in The Hero With a Thousand Faces . Today, it has been researched and taught by great minds, some including Carl Jung and Christopher Vogler (author of The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers ).

This research has given us lengthy and helpful lists of archetypes , or story elements that tend to recur in stories from any culture at any time.

And while some archetypes are unique to a genre, they are still consistent within those genres. For example, a horror story from Japan will still contain many of the same archetypes as a horror story from Ireland. There will certainly be notable differences in how these archetypes are depicted, but the tropes will still appear.

That's the power of the Hero's Journey. It is the skeleton key of storytelling that you can use to unlock the solution to almost any writing problem you are confronted with.

Why the Monomyth Will Make You a Better Writer

The Hero's Journey is the single most powerful tool at your disposal as a writer.

But it isn't a “rule,” so to speak. It's also not a to-do list.

If anything, the Hero's Journey is diagnostic, not prescriptive. In other words, it describes a story that works, but doesn't necessarily tell you what to do.

But the reason you should use the Hero's Journey isn't because it's a great trick or tool. You should use the Hero's Journey because it is based on thousands of years of human storytelling.

It provides a way to connect with readers from all different walks of life.

This is why stories about fantastical creatures from imaginary worlds can forge deep emotional connections with audiences. Hollywood knows this, and its best studios take advantage. As an example, The Lord of the Rings, by J. R. R. Tolkien, contains mythical creatures like elves and hobbits. Yet it is Frodo's heroic journey of sacrifice and courage that draws us to him like a magnet.

Learn how to easily apply the Hero's Journey 12 Steps to your books in this post. Tweet this

David Safford

You deserve a great book. That's why David Safford writes adventure stories that you won't be able to put down. Read his latest story at his website. David is a Language Arts teacher, novelist, blogger, hiker, Legend of Zelda fanatic, puzzle-doer, husband, and father of two awesome children.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers