Exploring Sunita Williams' Life And Her Remarkable Journey To Space

Sunita williams was born in september 1965, in ohio, to dr deepak and mother bonnie pandya..

Sunita Williams grew up in Needham, Massachusetts. (File)

Sunita L Williams, an accomplished NASA astronaut and retired US Navy Captain, has left an indelible mark on the world of space exploration. She was born on September 19, 1965, in Euclid, Ohio, to Dr Deepak and Bonnie Pandya, and her extraordinary career has made her a trailblazer in space exploration.

Early Life and Education

Growing up in Needham, Massachusetts, Sunita Williams attended Needham High School before embarking on a stellar academic journey. She graduated from the US Naval Academy in 1987 with a Bachelor of Science in Physical Science and later earned a Master of Science in Engineering Management from the Florida Institute of Technology in 1995.

Military Career

Sunita Williams was commissioned as an Ensign in the US Navy in 1987 and swiftly rose through the ranks, becoming a Naval Aviator in 1989. Her military career included overseas deployments to the Mediterranean, Red Sea, and Persian Gulf in support of Desert Shield and Operation Provide Comfort.

NASA Selection and Training

Sunita Williams was selected as an astronaut by NASA in 1998 and she reported for training in August of that year. Her astronaut candidate training covered a wide array of areas, including shuttle and International Space Station systems, T-38 flight training, and survival techniques.

Space Missions

Ms Williams' space journey began with Expedition 14/15 (December 2006 to June 2007), where she established a world record for females with four spacewalks totalling 29 hours and 17 minutes. She returned to Earth with the STS-117 crew in June 2007.

Her second spaceflight, Expedition 32/33 (July to November 2012), saw her spend four months aboard the International Space Station, conducting research and performing three spacewalks. Ms Williams once again showcased her spacewalk prowess, logging a cumulative time of 50 hours and 40 minutes.

Awards and Honours

Ms Williams' illustrious career has earned her multiple accolades, including the Defense Superior Service Medal (DSSM), Legion of Merit, Navy Commendation Medal, and the Humanitarian Service Medal, among others.

Current Endeavours

Sunita Williams remains actively involved in space exploration. She is currently training to be the pilot of the Crew Flight Test mission aboard Boeing's Starliner spacecraft, marking her third mission aboard the International Space Station.

Ms Williams' journey into space serves as a beacon of inspiration for aspiring astronauts and space enthusiasts. Her achievements, records, and dedication underscore the significant role women play in STEM fields, leaving a significant legacy for future generations.

Promoted Listen to the latest songs, only on JioSaavn.com

Track Budget 2023 and get Latest News Live on NDTV.com.

Track Latest News Live on NDTV.com and get news updates from India and around the world .

India Elections | Read Latest News on Lok Sabha Elections 2024 Live on NDTV.com . Get Election Schedule , information on candidates, in-depth ground reports and more - #ElectionsWithNDTV

Watch Live News:

Meet Suni Williams, the First Test Pilot for Boeing’s Starliner Spaceship

With 50 hours and 40 minutes under her belt, she’s racked up the second-most cumulative spacewalk time for a female astronaut, too. No big deal.

After our interview, Williams would attend a training class—one of many sessions required to learn everything she can about the upcoming CST-100 Starliner mission to the International Space Station (ISS) in April. Williams will be a test pilot on the first team flying the Starliner, Boeing’s new, reusable spacecraft.

The goal of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program is to work with private companies to expand spaceflight technology. A first-time mission on a brand-new craft means figuring out all kinds of things, like how to manually dock at the station and which maintenance tools to bring.

“We are the guinea pigs,” Williams tells Popular Mechanics . The crew needs to make sure all life-support systems are running smoothly and interactions with onboard automation systems are going well. “The idea is, let’s get more creative, innovative ideas out there to make spaceflight safer, more affordable. Then more people can take that journey into space,” she says.

Prior to joining NASA’s astronaut program in 1998, Williams accumulated more than 3,000 hours flying over 30 different aircraft for the U.S. Navy. On the first of two missions to the ISS, she spent six and a half months in orbit—one of the longest durations of any astronaut on the station—as a way to gather data on the human body during longer periods in space . While serving as a flight engineer, Williams went on four spacewalks, more than any other female astronaut, totaling about 29 hours. During her second ISS mission, which lasted four months, she spent another 21 hours on spacewalks. In total, she’s racked up the second-most cumulative spacewalk time for a female astronaut, second only to Peggy Whitson .

One thing people back on Earth don’t realize is how hard it is to move around and handle tools while suited up in your space gear. Training for space is hard , Williams explains. While astronauts don’t notice the 300 pounds of weight in microgravity, it feels like you’re wearing a huge, multilayered balloon, she says. “And the gloves are big—it ’ s like wearing snow gloves to handle tools.”

Having patience is part of the job too, she says, because it takes a large team to make sure everything is done safely and accurately out there. On her first spacewalk, an 8-hour job, she and her partner had to play the waiting game, while engineers and Mission Control figured out the best way the astronauts should maneuver a large piece of equipment. “Having patience is is part of the job,” she says.

On the Mind-Boggling Reality of Earth From Space

Fortunately, there’s Earth below, a gorgeous site that never gets boring, Williams says. The first time she went outside, it was on Earth’s night side, and only her helmet light lit her path along the exterior. She wasn’t really nervous, because it felt just like her training exercises. “Then, the sun started to come up, and I could see the Earth below us. And then I was like, oh, whoa. When you see the Earth zipping below you—fast—you’re like, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m outside, flying formation, on this International Space Station. Hold on!’”

After a while, her sense of duty and focus kicked in, but Williams still took a second every now and then to soak in the sight of the bright Earth below . And after a couple of spacewalks, she and her partner were holding the ultimate geography quiz, debating geographical features on the real-life globe.

.css-2l0eat{font-family:UnitedSans,UnitedSans-roboto,UnitedSans-local,Helvetica,Arial,Sans-serif;font-size:1.625rem;line-height:1.2;margin:0rem;padding:0.9rem 1rem 1rem;}@media(max-width: 48rem){.css-2l0eat{font-size:1.75rem;line-height:1;}}@media(min-width: 48rem){.css-2l0eat{font-size:1.875rem;line-height:1;}}@media(min-width: 64rem){.css-2l0eat{font-size:2.25rem;line-height:1;}}.css-2l0eat b,.css-2l0eat strong{font-family:inherit;font-weight:bold;}.css-2l0eat em,.css-2l0eat i{font-style:italic;font-family:inherit;} “If you have a dream, go for it. Don’t let other people tell you, you can’t do that. It doesn’t matter where you come from, what your socio-economic, religious or racial background is. We have people from a lot of different occupations here, not only military pilots, like myself, but people who are doctors, teachers, scientists, engineers. Go for your passion, be dedicated to what you’re doing . . . all of this isn’t achievable unless you’re part of a big team. Nobody can do this alone.”

— Sunni Williams , on the advice she’d give to children who want to work in space

As a new astronaut, Williams was overwhelmed by her first glimpse of our planet. “I have to say, the first thing I thought was, ‘Oh, my God, it is round. Not that I didn ’ t believe it, you know. But when you see it with your own two eyes, it ’ s pretty amazing. You could see the curvature of the Earth. ... I mean, that is our little planet, a little planet in space … When you actually can see it, it ’ s overwhelming. It ’ s beautiful.”

The space station whirls around Earth once every 90 minutes. Williams never quite got used to seeing our planet below her, and the millions of stars in an inky blackness everywhere else. She and her colleagues had to work on board, but the sight of Earth was distracting, she says. “So, you have to get into the routine, or else you wouldn ’ t do anything, you ’ d be just sitting there gawking out the window the whole time.”

On Staying in Shape Without Earth Gravity

One of Williams’ regular duties on board the ISS is to exercise; she’s loved running all her life. While all astronauts need to counteract the muscle-diminishing effects of microgravity , Williams literally goes the extra mile, whether she’s on the space station or on the ground. During the 2007 Boston Marathon, she didn’t let her position—about 250 miles above the other runners’ heads—stop her from participating. After four hours of running on a treadmill on the ISS, which itself shoots around Earth at 17,500 miles per hour, she completed the race. Watching a video of five years of Boston Marathon highlights and listening to an outdoor running soundtrack that a mission control team recorded for her helped a lot, she says.

Still, it wasn’t easy running on a treadmill indoors—no real race atmosphere, no wind in her face. “About mile 10 I said, ‘Oh, my gosh, what am I doing?’” Williams recalls, laughing. “But I really just wanted to highlight that physical fitness is important. It doesn ’ t matter who you are, where you are, what you ’ re doing, you know. Just keeping yourself in good shape is really important.”

As a spacefarer, you have to adapt to wild, rapid changes in your environment. In just about 10 minutes, a human body on a rocket experiences three or more times the force of gravity, then leaves Earth gravity behind. Then you have to be fit enough to work on the space station, Williams says. “You know, it ’ s hard on your body and being able to stay be in shape. When you ’ re in space, using the exercise equipment is really important to make sure that you ’ re ready to come home, and your body is ready for all that gravity again.”

This story is part of an ongoing series for Women ’ s History Month. Stay tuned for future stories each week in March (and check out our first installment with Clarice Phelps , who is separating plutonium isotopes for NASA ’ s nuclear space batteries.)

Before joining Popular Mechanics , Manasee Wagh worked as a newspaper reporter, a science journalist, a tech writer, and a computer engineer. She’s always looking for ways to combine the three greatest joys in her life: science, travel, and food.

.css-cuqpxl:before{padding-right:0.3125rem;content:'//';display:inline;} Pop Mech Pro .css-xtujxj:before{padding-left:0.3125rem;content:'//';display:inline;}

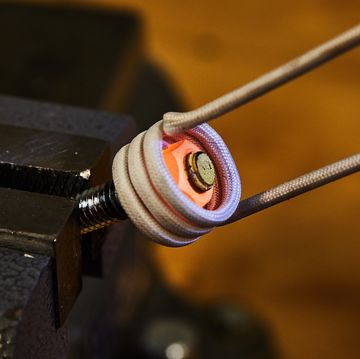

DIY Car Key Programming: Why Pay the Dealer?

Use Induction Heat to Break Free Rusted Bolts

How to Replace Your Car’s Brakes

The Air Force is Resurrecting a B-1 Bomber

Who Killed Harry Houdini?

A New Hypersonic Missile Will Give the F-35 Fangs

The Navy’s New Drone Could Turn into a Ship-Killer

The CIA’s Secret Plan to Turn Psychics Into Spies

Is This the Real Iceberg That Sank the Titanic?

A Barrage of Missiles Met Resistance Over Israel

The Navy's New Frigates Are Behind Schedule

Advertisement

Astronaut Sunita Williams On Her Time In Space And 'The Mars Generation'

Copy the code below to embed the wbur audio player on your site.

<iframe width="100%" height="124" scrolling="no" frameborder="no" src="https://player.wbur.org/radioboston/2017/07/28/sunita-williams-mars"></iframe>

- Caitlin O'Keefe, Meghna Chakrabarti

Sunita Williams, a native of Needham, has traveled far beyond Massachusetts as part of her work as an astronaut at the International Space Station. She served as the commander of the space station in 2012, and has spent a total 322 days in space. She also has spent more than 50 hours on space walks alone.

She is featured in the new documentary film " The Mars Generation ," which looks at a new generation of teenagers who are preparing to go to Mars in this century.

"The Mars Generation" is playing at the Woods Hole Film Festival on Sunday at 5 p.m. Williams will also be speaking on a panel about science and storytelling on Sunday at 2 p.m.

Sunita Williams , American astronaut and former commander of the International Space Station. She tweets @Astro_Suni .

Interview Highlights

On her path to becoming an astronaut It was a little bit of a happenstance, and a lot of good luck, and a lot of perseverance. I wanted to be a veterinarian, and go to school in Boston. It didn't quite work out that way, and I ended up joining the Navy as a suggestion of my big brother. It was really awesome, and I didn't realize it at the time, but provided a lot of leadership and followership teamwork opportunities. And it led me down the path to become a helicopter pilot and a test pilot. It was the shoe in the door to making me understand that, hey — things are possible. And I got down to NASA at Johnson Space Center and realized that I could do the things those guys were doing, like anybody can when they have that opportunity and take it.

On her time as a commander on the International Space Station It was awesome. A huge responsibility. But just like in the movie "The Martian," you take it one step at a time. You don't look at the big problem all together, because I think it's a little intimidating. So you just take it one day at a time, meet the people who are going to meet with you, for you, and who you're going to work for, and really try to do the best job that you can. That's all teamwork, and that's what space travel is about.

On what it's like to do a spacewalk It's a little scary at times, when it's just your visor between you and the outside, not-so-nice area of space where there's no air to breathe — a vacuum that's really hot, and really cold. So that's scary. But you take it one step at a time. You have a lot of things to do when you're out on a space walk, and that sort of overwhelms your mind. You're like, "I've got to get this test done, and this test done." But you can't help every now and then stopping, and looking at where you are, and watching the world whiz by you — and just going, "Whoah! But — never mind — just keep working, just keep working." It is an incredible view, an incredible place to work, and it's the culmination of a huge team of people making it work for the astronauts who are just out there doing their jobs.

On what her time in space has taught her about the challenges facing potential Mars astronauts You are away from home, and you do miss your family and your friends, and of course I missed my dog. But you have the ability to call home, and the ability to video conference on the weekends. We're close to Earth, and we only have about a half-second of delay when we're talking. But when you take that trip and are going to Mars, you're going to have a long delay. You're not going to be able to have those instant conversations. You're going to need to know how to fix things without calling home to ask how to do it. So there's going to be a lot of different challenges for that crew, and that crew needs to know that they'll be gone for a long time. I knew I would be gone for 6 months, and maybe a little bit more. [People going to Mars] need to go into this knowing that you might be gone for a year and a half or so. You're not going to be able to text to your friends and family like people are used to doing here. It's going to take a little while to get that communication back and forth.

On whether the golden age of manned missions to space through NASA has passed, with the advent of space trips through the private sector. This is all a partnership. There's been so much technology that has transpired over the last 20, 30 years, and it's time to move that into the spacecraft. Who can better do that than the technology gurus out there who have been working in some of these companies? We're really excited to see what their innovative ideas bring to the table when they create these spacecraft. They're going to solve the problem for us of low-earth orbit, which means going to the International Space Station and delivering people. And that frees up NASA to work on exploration. The thing that we all want to do is get out of low-earth orbit and go farther, so we can figure out that problem of how to go to Mars. So we have a lot on our plate, but we are working hand-in-hand with these companies, so we can leverage information and technology off each other. And my personal opinion, Suni Williams — I think that when we really leave the planet — we all go as humans, not as people from one country or another. We are humans, we work together. This is our only planet as human beings that we know of. So we all should have an interest in preserving it.

On the idea of space tourism I think it's great. If these companies can go out there and lower the price for folks to go to space, that's going to enhance space travel and make it safer. We've gone through this kind of evolution with aircraft, and aircraft are pretty darn safe. We joke that one day, we'll have a space station on the moon, and the tourists up there will be going, "Where's my spacecraft to get me home? It's 10 minutes late!" Just like we do when we're standing in the airline line waiting to board our aircraft. I think it's a good thing. It's progress. It's evolution. We're going to make it all happen. And I think this next generation of kids in high school and younger — we've got to set the stage for them, and they are going to make it happen.

On the most amazing thing she's ever witnessed in space There's so many things to say, but one things is the aurora. Watching the aurora from above is pretty spectacular. We live up here in the north, and sometimes we go to see our northern neighbors, where we can see the aurora at night, and see it above you and it's cool. But when you see it from above looking down below, and see that energy hitting the earth, it's spectacular. And you got to wonder — there is a lot of energy out there in the universe that we have no idea how to capture and use. Our problems here on earth are a little slim compared to the real deal.

This segment aired on July 28, 2017.

- Space.com Meet 'The Mars Generation': In Documentary, It's Red Planet or Bust

More from Radio Boston

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Brave New Workers

A nasa astronaut stays in orbit with spacex and boeing.

Alexi Horowitz-Ghazi

Emily Sullivan

Sunita Williams conducts routine maintenance during a stint aboard the International Space Station. Nowadays, the astronaut helps Boeing and SpaceX develop private spacecraft. NASA hide caption

Sunita Williams conducts routine maintenance during a stint aboard the International Space Station. Nowadays, the astronaut helps Boeing and SpaceX develop private spacecraft.

Sunita Williams wasn't the kind of kid who wanted to be an astronaut when she grew up. She wanted to be a veterinarian. But she managed to achieve the former kid's dream job, anyway.

Williams, 52, has completed two missions to the International Space Station, spending over 11 months orbiting the Earth in total. She's also noted for her total cumulative spacewalk time , having spent 50 hours and 40 minutes outside the International Space Station. She has continued her career in space on Earth as a member of NASA's Commercial Crew Transportation Capability (CCtCap), a group of veteran astronauts that works with privately held companies like Space X and Boeing to develop spacecraft.

Part of her job is to verify that the companies' spacecraft can launch, maneuver in orbit and dock to stationary spacecraft like the ISS. NASA announced the CCtCap in 2015 as part of "the Obama Administration's plan to partner with U.S. industry to transport astronauts to space, create good-paying American jobs and end the nation's sole reliance on Russia for space travel."

"This is really different from my old job, you know," Williams said. When she became an astronaut, the shuttle was already laid out. "It was all documented and out there, and [I] went through classes to understand all the systems," she said. "The plan was there, and you had to get this, this and this done before you could go fly out in space."

Her path to the stars began with the Navy. Williams graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy with a bachelor's degree in physical science in 1987. After graduation, she was designated a Basic Diving Officer at the Naval Coastal System Command. She was designated a naval aviator in 1989 and went on to log more than 3,000 flight hours in more than 30 different aircraft.

Williams received a master's degree in engineering management from the Florida Institute of Technology in 1995. In 1997, she, along with more than 100 other people, applied for a position as an astronaut. After more than a year of interviewing, she was selected by NASA in June 1998. Williams spent five months training for her first mission, and received intensive instruction in shuttle and ISS systems, and water and wilderness survival techniques. Williams also spent nine days underwater in NASA's undersea Aquarius laboratory .

Williams took her first ride into space on Dec. 9, 2006, aboard the STS-116. "We were hootin' and hollering," Williams said of her first takeoff. "It is like the best roller coaster ride you've ever been on."

"You take your gloves off, your gloves start to float," she recalled. "It's a whole different mindset. It's pretty spectacular."

Williams served as Expedition 14/15's flight engineer and returned to Earth on June 22, 2007. On July 14, 2012, Williams returned to the ISS as part of Expedition 32/33 to conduct general research abroad the orbiting laboratory. She returned to Earth on Nov. 18, 2012.

For Williams, every day at the International Space Station was different. "One day you might be cleaning the toilet, next day you might be doing some potentially Nobel Prize-winning science," she said.

Williams says that during her two long stays aboard the ISS, she and her fellow crew members worked to keep a normal earthbound schedule and a sense of regularity to their days. "We get up at 6 o' clock or so, and there's daily planning conferences with control centers all over the world," she said.

Sunita Williams performs maintenance during a spacewalk outside the International Space Station in 2012. The astronaut has spent more than 50 hours "spacewalking." NASA photo hide caption

Sunita Williams performs maintenance during a spacewalk outside the International Space Station in 2012. The astronaut has spent more than 50 hours "spacewalking."

On Fridays, the astronauts would indulge in films from both Russia and the United States. Williams recalled that Groundhog Day was a favorite, given how repetitive the days aboard the ISS could feel. By the time she returned permanently to Earth in 2012, she had spent 322 total days in space — at the time, her combined stints were the longest on record for female astronauts.

Since the discontinuation of NASA's space shuttle program in 2011, U.S. astronauts have had to rely on Russian shuttles to get into orbit — which Williams and her internationally sourced crew did during her 2012 mission. Compared to its heyday, publicly funded space travel in the U.S. was no longer a hugely viable option for those wishing to explore space — but as it turned out, private space travel was.

Privately funded companies such as Space X and Boeing have made it their business over the past two decades to take over some parts of space travel from NASA. That business is booming — just last month, Space X successfully launched the most powerful rocket in decades. The launch was one small step toward Space X founder Elon Musk's ultimate vision: a colony of a million people living on Mars.

In order to achieve those otherworldly ambitions, Space X and other private companies need the right kind of people working for them — people like Williams.

This Pilot Is Headed To Space With Or Without NASA

Hidden Brain

Even astronauts get the blues: or why boredom drives us nuts.

The space machinery of private companies that Williams now supports are still works-in-progress. "They don't really have training systems established for them yet," she said. "We're sort of creating that right now with the folks at the companies." That means deciding what things are important for astronauts to know — "classic things like getting in your seat, reach[ing] all the controls," she said. "We're establishing all that with the companies right now." Her contributions have helped to build the Boeing CST-100 Starliner and SpaceX Dragon .

Williams' work has also provided transportation for NASA astronauts to her old base, the ISS. And more broadly, Williams says that private space companies just want to keep learning and exploring. Though she works with familiar components and protocols, she says her new job feels like a new frontier. Williams hopes to revisit the ISS in the future on the very spacecraft she's helping to develop.

"We want to keep finding the next thing," she said. "And this type of exploration with a common goal, a common good of looking at something farther and bigger than ourselves. It totally opens the door for collaboration and cooperation for people from all over the world."

NPR's Noor Wazwaz helped to produce this story for broadcast.

Correction March 26, 2018

A previous version of the Web story said Sunita Williams holds the record for total cumulative spacewalk time by a female astronaut. In fact, though she once held the record, that record has been surpassed.

- private space exploration

- International Space Station

International Space Station Program Oral History Project Edited Oral History Transcript

Sunita l. williams interviewed by jennifer ross-nazzal houston, tx – 8 september 2015.

Ross-Nazzal: Today is September 8, 2015. This interview is being conducted with Sunita Williams in Houston, Texas, at the NASA Johnson Space Center for the International Space Station Program Oral History Project. The interviewer is Jennifer Ross-Nazzal. Thanks again for taking some time today to meet with me, appreciate it.

Williams: My pleasure.

Ross-Nazzal: Captain Williams, you became a member of the Astronaut Corps in 1998, and since that time you’ve served in a number of capacities for the Space Station Program. Following your training and evaluation, you worked in Moscow with the Russian Space Agency on their contribution to the Space Station and on the first Expedition. In 2006 you flew on STS-116, NASA’s twentieth Shuttle Station assembly mission, and remained onboard the Station, serving as flight engineer for Expedition 14-15 crews. Six years later, in 2012, you served as the flight engineer for Expedition 32 and commanded Expedition 33. That’s quite a list.

Williams: It’s fun. I’m lucky.

Ross-Nazzal: You’ve been involved in so many ways with the Space Station. Can you talk about how you became involved initially, and your role in Expedition 1?

Williams: As the seventeenth group of astronauts that came here in 1998, we were pretty lucky, because as soon as we got here the Space Station got rolling. That fall/winter was the first flight of the first piece that went up to create the Space Station: Zarya, the FGB [Functional Cargo Block], the first piece that the Russians launched. So it was almost immediately since we got here, things were happening for the Space Station. It’s neat to look back and look at our careers of our group of people. It’s all been Space Station pretty much the whole time. Right from the get-go, I think all of us really wanted to be involved one way or another in the construction, going up and living there, doing science experiments, or something that had to do with the Space Station. As soon as we got done with our basic training, that was a brand-new world; I came from the Navy helicopter world of test and evaluation and really had not much insight into the space program except for what was historically out there and what was advertised as cool. So it was like jumping in with two feet to really understand what was going on, just learning about how spacecraft worked and then of course the International Space Station. I was pretty pumped, because I come from a pretty diverse background. My dad’s from India, my mom has a Slovenian descent. I was pretty excited to learn about Russia and the Russians, particularly since I was in the military and it was a little different face on our relationship in my early military career. It was neat to actually get in there and put my hand up and volunteer to go to Russia. I knew a lot of people were doing that in the beginning, just to understand the Russian part of the Space Station and how that was going to be integrated with the American part of the Space Station. Then, of course, how we were going to further on integrate the rest of our international partners. Then I thought, “Wow! Language and culture are the first couple of ways that you understand a different system and program.” Tried to jump right in there with two feet and learn the language a little bit and started spending time over there as we were doing what you’d call procedure verifications on the Russian equipment with the Russian procedures. Essentially what that meant was the Russian procedures were out there in Russian, and then we had a group of translators who were translating them, although their backgrounds may or may not have been in the space business. As new astronauts, understanding how space systems are supposed to work, we would read through those procedures as they were translated into English and see if it actually made sense to us. We were AsCans, astronaut candidates, at the time. If it passed the AsCan test, then I think the rest of the astronauts would have been fine with the procedures that they were going to get. It was a neat opportunity. We lived in a place called the Volga in Moscow and would take transportation—a group of us—out to a company called Energia, which in my mind of the Soviet Union, lived up to every expectation, with the dual gates and the lady at the door with a card-punch reader, the barbed wire, the lights, and all this stuff. So we were really stepping into a Russian space company, and I thought, like I said, with my background as a military guy, that was pretty significant, that we, as partners, trusted each other. Granted, we were escorted wherever we were going, but still, we were welcomed with open arms to come in and do the job that we were assigned to do. That was pretty cool. Part of that was also going out to Star City for the first time and seeing the crews that had been training there for a long time. Of course, Bill [William M.] Shepherd, Susan [J.] Helms, Jim [James S.] Voss, for a number of years, had been training. Seeing what they were doing, and then seeing the work that we did with the procedures get turned over to them and see[ing] how they were going to react and what feedback they had, and how we could help them prepare and get ready for the first flights to the International Space Station was a pretty cool step right out the door after one year of just learning about space stuff. “Now get out there and actually put what you learned to use and help these guys be successful on their mission.” I think there was about 10 of us who were doing that, going back and forth to Russia: Tracy Caldwell [Dyson], Doug [Douglas H.] Wheelock, Peggy [A.] Whitson, Mike [Edward Michael] Fincke, Sandy [Sandra H.] Magnus, Rex [J.] Waldheim—I’m forgetting somebody—Piers [J.] Sellers, mostly class of ’96 and the class of ’98 who were helping these guys get ready. So it was a lot of fun. It was eye-opening, and I think it really got all of us in the mode to really want to be part of this program as well, being not only here on the ground, but really wanting to go to space, getting ready to go on a Shuttle or on a Soyuz eventually.

Ross-Nazzal: You mentioned you raised your hand?

Williams: Right away, yes. I was like, “Sign me up, I want to do that.” I was in a really nice position; I have a great supporting family and husband. He’s also military background. We both deployed quite a bit when we were active duty military, both of us together. I told him that I thought this was a neat opportunity, and he was like, “Go ahead.” So our family situation lended itself easily to this, which was nice too. He’s pretty supportive and interested himself. He actually had the opportunity to come to Russia right before the first Expedition crew launched as well, and we got a chance to tour around over there. I think it’s going to be part of your family life whether or not you like it or not. Once you become part of this office, your family gets involved one way or the other.

Ross-Nazzal: Did you get to see the launch of Expedition 1?

Williams: I did, yes. If you watch the IMAX film of the ISS, I have a cameo in there carrying Shep’s bags as he arrived in Baikonur right before the launch. I was down in Baikonur for the launch; my husband had just got to Moscow, he watched the launch from Mission Control at TsUP [Moscow Mission Control], and then we were around together before docking, because in those days, in my flight too, it was two days before the docking.

Ross-Nazzal: Wow, that’s pretty cool.

Williams: Yes, it was pretty neat.

Ross-Nazzal: Had you seen a Shuttle launch before then?

Williams: Yes, I had. One Shuttle launch, 4A [STS-97], which was pretty neat, because 4A brought up the very first solar array, P6, for the Space Station, which was necessary before they put on the laboratory Destiny. That was the power that was going to support the U.S. laboratory. Those were two critical steps before you could have people get to the Space Station. So yes, my very first Shuttle flight was 4A, and then Shep’s launch, which was in October. I think 4A was that summer. So those were all in rapid succession.

Ross-Nazzal: Could you compare and contrast the two? Were they very similar or different?

Williams: You know, Brent [W.] Jett was the commander of 4A, and I got to know him pretty well, another Navy guy, just like Shep; I think the Navy guys get to know each other pretty well. I knew what they were doing, [but] I think I didn’t understand the enormity of what they were doing, putting on this humongous solar array with the robotic arm on the Space Shuttle, which was pretty incredible, and how they actually maneuvered it. Joe [Joseph R.] Tanner was on that flight as well, and Carlos [I.] Noriega. I understood it just from the periphery. Those were my friends, and it was nighttime, so definitely it left an impression that you hope your friends are going to be okay. With Shep’s launch, the rocket’s a little smaller, the Soyuz rocket; you’re a little bit closer, so the feeling, the sound, the pressure are pretty comparable. I think I had worked a little bit closer with those guys and knew that they were going to be gone for a long period of time, so I think it was a slightly bigger impression on me with Shep’s launch. The two Russians, of course, had become my good friends, Sergei [K.] Krikalev and Yuri [P.] Gidzenko. I had worked with them as well as Bill Shepherd, all of us had, for the last year and a half or so, so it was neat to see those guys, who we really helped, things that we did helped them get into space. I think that was a little bit bigger impression. Pretty psyched for it. I think you have this impression that your country’s stuff is going to work. You’ve seen it before on TV, and when you’re someplace else watching somebody else’s stuff, you feel like it’s going to work but you’re not 100 percent sure. I don’t know why. That seems goofy, but I think it’s true. Until you get knowledgeable about it yourself a little bit, I think you’re additionally crossing your fingers and hoping everything’s going to go okay. Like I said, it’s a little bit goofy and a little silly. I feel very confident in the Russian stuff. Myself, I’ve launched on a Russian rocket, so I don’t have any questions about it. I think it’s just the fear of the unknown, and at that point in time it was a little bit more unknown to me.

Ross-Nazzal: Would you talk about your first Expedition, 15, being flight engineer?

Williams: I think everything, for the first time, is the first time, so you go into something with your eyes wide open, and I think I never really thought it was going to happen. I saw my friends, like I mentioned before, launch into space. Of course it’s getting closer and closer to our class, and people in our class getting assigned and actually going to space, but you never feel like it’s really going to happen to you, at least that was my impression. When we were getting ready to launch on STS-116, we actually had one launch attempt that didn’t happen. It got all the way down to about the five-minute hold, and then we stopped, which is a little bit farther down than the general hold is. It’s usually about nine minutes, but we went all the way down to right before APU [Auxiliary Power Unit] start, and we ended up having to scrub because of weather downstream. Then we were going to get ready to launch two days later, and the weather was seemingly, at least at the pad, much worse. It was actually raining on us when we went out to the pad. So again, I think that was one other piece of reassurance that this is never really going to happen to me. Not only me, but also the other rookies on the flight, Joanie [Joan E.] Higginbotham and Christer Fugelsang. They had been training for even longer than myself. I think all three of us were a little bit in disbelief it was actually going to happen. So when it did, I think the three of us were pretty much hootin’ and hollerin,’ like, “Oh my god, here we go!” It was pretty loud on the middeck. Actually the flight deck guys were like, “Hey, you three, be quiet down there,” and we were like, “Yes, here we go! Here we go!” It was great to train with those guys. I was a little bit of an outsider, I would say, because I had always, on my path, been a long-duration guy. I had gone from flight to flight, increment to increment. Started, I think, with Expedition 8 and got all the way up to Expedition 12. I had trained with all these different Expedition people, and that was on the cusp of Columbia [STS-107], so initially we were all going to go on Shuttles, and then people went on Soyuz. Then we were still part of the assembly, so finally it got nailed down to 12A.1 [STS-116], and I finally got put onto this crew. There was a little bit of crew changing around after Columbia also, just to optimize commanders and pilots and EVA [Extravehicular Activity] crews and things like that. It finally settled out so I came into their training flow a little bit late, but they welcomed me with open arms, and I felt like I was absolutely part of 116 by the time we got down to the last six months before flight and it was really going to happen. I will also say, when we shut the hatch and those guys were going home with Thomas Reiter, I was like, “Wait a minute, what am I doing? I’m still staying here. Why aren’t I going home with those guys?” It was a little bit of adjustment, I might want to say a mind adjustment, to try to get my arms wrapped around [the fact] that I was going to stay. Of course I had great friends up there—Mike [Michael E.] Lopez-Alegria, Misha [Mikhail] Tyurin, who I joined Expedition 14 with. I remember being in the Soyuz capsule with the window tilted a little bit, looking out at the Shuttle as it undocked and flew away. It was a tough moment, but then I went down to the table and had dinner with Misha and L.A., and all was much better. Then started a really fun increment. Maybe I have low expectations, but I never had an idea of how cool it was going to be to really live in space and adapt to space and just feel like you’re at home in space. That’s what Expedition 14 did for me, and part of that was three spacewalks with L.A. I had done one spacewalk during the Shuttle flight with Bob [Robert L.] Curbeam, who was awesome and taught me confidence and ability to just get out there and get stuff done, because we encountered a lot of interesting things. As you might have known, one of our solar arrays didn’t quite retract all the way, so we had to go up and shake it, to get it to move and do a couple of different on-the-fly types of things to get this thing to work. I think it was really solidified when I did my three spacewalks with L.A., and we had set tasks that we had to do. These were critical parts of changing the Space Station from a temporary living quarters to a more permanent living quarters, as we changed out the heating and cooling systems from temporary to more permanent, changed electrical power systems [from] temporary to permanent. These tasks were not simple, never been done before. They were hard; they didn’t all go as planned, sort of went out of order. Again, the confidence that I gained with doing spacewalks with Beamer was then solidified with L.A. as he taught me a lot of tricks of the trade and how to talk to the ground to make sure that they understand the issues that we’re having, and then solve them. I couldn’t have asked for two better mentors for spacewalking. So Expedition 14 rolled into 15 was all about construction of the Space Station and getting it to its more permanent configuration. That’s spacewalking, but that’s also inside, too. We did a lot of rewiring for the computer systems on the inside as well as oxygen generation and other things to make sure the inside of the Space Station was ready to go. There was a little bit of a gap in there, because STS-117 was supposed to come up and add on another solar array while we were there. However, they were delayed because their external tank got hit with hail out on the launchpad, and they had to roll the whole stack back into the VAB [Vehicle Assembly Building] and fix up the external tank. We all thought that was a joke, too. We were like, “No, you gotta be kidding me. That’s not really happening.” They were like, “Well, yes, it really is happening, and no, this next Shuttle is not going to come for a while.” “Oh, okay, well, whatever that means.” That gap was actually pretty interesting for me. It was a time when L.A. and Misha were going home, and then I was going to be there with two Russian colleagues, Oleg [V.] Kotov and Fyodor [N.] Yurchikhin. Maybe I underestimated again the enormity of the feeling that I was going to have. When L.A. left, I was like, “Oh my, I am the only American up here at this time. Maybe I’d better watch my language and I’d better be nice.” I have big shoes to fill. But it felt good. It didn’t feel overwhelming, but it was a little bit surprising to me how significant that felt. With the delay of STS-117, it allowed a little bit more time to do some science, and I could really appreciate the Space Station for its ability to do some really neat science, including fluid experiments. I’m trying to think of other things that we were doing on 14—I’m getting a little mixed up with [Expedition] 32—biological experiments, food experiments, fluids experiments, growing plants experiments. The Space Station was just starting to do science type of stuff, so it gave me a real good appreciation of that, and how flexible, also, the flight control teams and the investigators can be to really make the most of this amazing Space Station and laboratory in the sky. At the end of that, my good buddy Clay [Clayton C.] Anderson came up; he came up on 117. They were somehow able to move a lot of stuff around so that they could add one more crew member, so they added Clay to it, and they brought me home. We weren’t going to switch out until STS-118, but they were able to make it all happen. Another hats off to the guys in the program office who were able to reallocate priorities and get me home in 195 days, which was a little bit longer than anybody had expected. As a relatively young guy, that was important because it was eating up my radiation. So if I was going to ever get to fly again, I needed to come home at some point in time, and there were a lot of good folks, Chris Hadfield being one of the ISS ops guy, looking out for all of us who were up there, making sure that we actually would have the opportunity fly again. That was good for me, and it allowed Clay to get up there and jump into his Expedition, do a couple of great spacewalks with his Russian counterparts, and then get ready for 118, who was the group that he was training with. So a lot of good friendly faces for him to meet up with.

Ross-Nazzal: Talk about Expedition 32/33. You mentioned that 14 and 15 were really focused on the construction of ISS; now the Station was built, you weren’t flying up on a Shuttle, you were flying on a Soyuz. There have got to be a lot of differences, plus you got to command an Expedition.

Williams: Yes, 32-33 was pretty special, really awesome. [Expedition] 14/15, like I was mentioning, the first time is always the first, but 32-33 I felt like now I really knew what I was getting into. It wasn’t going to be as much of a surprise, except for the fact that we’re launching on a whole different vehicle from halfway around the world, so that was all exciting and challenging. I had great crew members, not Americans, one Japanese and one Russian, Aki [Akihido] Hoshide, Yuri [I.] Malenchenko, who I got to fly with in the Soyuz, and then got to see two other groups of folks on the Space Station: 32, Joe [Joseph M.] Acaba, Gennady [I.] Padalka, Sergei [N.] Revin—one of the most experienced guys, Gennady. Then on the back side, Kevin [A.] Ford and two Russian rookies, Evgeny [I.] Tarelkin and Oleg [V. Novitskiy]. It was totally the major gamut. The training for that flight was pretty cool, too. We backed up somebody from every single agency, which was pretty neat—European and American and Russian. We were the backup to them, and then the backup to us was a Canadian, an American, and a Russian, and we had a Japanese guy onboard. It was really neat to see all the different cultures play together, work together, understand really what the backup concept is. Of course we had that with the Shuttle, but it was only one person switching out for the Expedition. Here it was a whole different crew, and it’s nice to be a backup so you could understand and see all the launch preparations and also understand all the Russian traditions that are associated with a launching on a Soyuz, and going down to Baikonur and hearing the history of Yuri Gagarin and Sergei [P.] Korolev and how all of that happened. Really getting to know all that was, I think, a huge part of that Expedition. I think it goes back to the very beginning of when I was in AsCan and getting my first job. I think the important part of the International Space Station is understanding all these different cultures and really trusting them when you are going to go launch on their spacecraft, and really becoming really good friends with not only the cosmonauts, but also the trainers and the search-and-rescue people and the Russian management, who are signing their name on the dotted line to put you in that rocket and launch you. It was a great experience, and again, you get to drag your family and friends into it, which is fun. I think my husband was pretty surprised at how different Baikonur is from Kennedy [Space Center, Florida], to say the least. But they serve the same purposes, they’re places where not a lot of people live, because you’re launching dangerous rockets and downstream you’ve got to worry about what’s going on with the rockets. I think there was a lot of good appreciation, and it’s nice to actually have brought all that tradition back to your friends and family, who probably, for no other reason, would’ve never learned anything about the Russian space program. So I think a great time in our history to have shared all of that commonality with people back here in the United States. This was an Expedition that was planned to do mostly science. The going-in plan was this is a laboratory. The Space Station is built; let’s get up there and just do as much science as possible. We’ve got the Japanese laboratory, the European laboratory, U.S., Russian, the Canadian arm; we’ve got an external platform, we’ve got an external airlock for payloads, we’ve got lots of things going on, and get up there and do science. Just like my last Expedition, it’s looking one way, but it turns a little bit the other way. We did a whole lot of science: inside, outside. AMS [Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer] was up there as well. We had experiments going on outside, doing things that I’m nowhere near smart enough to understand, collecting radiation and understanding things about our universe, as well as doing the biological experiments, the nutrition experiments, the physical fitness experiments, the fluid dynamics, flammable materials, entropy, how all microgravity works with all that stuff. So it’s huge amounts of experiments. In one day you’d be doing experiments all over the laboratory. Our Expedition also turned out to have a couple of spacewalks. We ended up doing three spacewalks during our time up there, partially planned. We had a big circuit breaker box on the outside of the Space Station, it’s called a multi-bus switching unit (MBSU), that we knew we were going to change out. Pretty important, it essentially routes one-quarter of the power of the Space Station from the solar arrays all around to the rest of the Space Station. When you take that out and change it, you have to bypass all that power, so it decreases the redundancy for a lot of the equipment on the inside. So we had to set that all up, and then we were getting ready to go out and do the spacewalk and replace this box. We ended up having a little bit of a problem. I take this back to the things that Beamer and L.A. taught me. That’s not a surprise; some of this stuff’s been up in space for a number of years. It’s been through a lot of heating and cooling cycles. It’s been in vacuum, so things aren’t going to work as planned. Like I said, I learned that from my first Expedition. We didn’t necessarily even get our hands on this equipment before it launched to space, because it was part of the assembly sequence. At that time we had no idea that we’d be doing an Expedition that would be changing this thing out. Yes, we’ve practiced this in the pool with things that worked ideally. Then you get into space, and then people find out, “Oh, well, you know what? We forgot to tell you about this, this, this, and maybe that might not work.” We had a hard time getting that box out, but we did, the old one. We started to put the new one in, and the bolts actually started to cross-thread a little bit and jam up, so we had to be a little bit careful, because we had to leave the box in a particular position such that electrical power wouldn’t be jumping across the circuits. We tried a couple of times, and then we ended up doing a pretty long spacewalk of about eight hours, Aki and myself, with Joe Acaba driving the robotic arm. We ended up having to do what I think everybody hates to do, just leave it as is and come back in and reassess with the ground team. Take a couple of days, take a breather, and leave the Space Station in that little precarious power situation, knowing we’re all going to have to live like that for a couple of days. If we had another failure, things would’ve been a little bit more sticky. Just have to deal with that and let the ground teams understand the problem and then come up with a solution. About four days later, we went back out again and had a plan of how we were going to tap and die and bolt, clean it all off, regrease it up, and put it back in. Everything actually worked as planned as the Boeing engineers and the folks on the ground had worked out. So a lot of hats off to a lot of people who did a lot of work to get us ready to go, including coming up with some homemade tools, with a toothbrush and some other little duct-taping things together, essentially, to take out there, because you don’t have Home Depot or Ace Hardware up there, so you’ve got to make your own tools sometimes and take apart other boxes to make a tap and die system. But we ended up getting it all done, and that was just a normal spacewalk of about six and a half hours, so that was good. Then more experiments for while we were up there. We switched out, and Joe went home. Kevin came up and had the opportunity to get him onboard just in time for us to go out and try and fix a radiator leak. Aki and I again went back outside; poor Kevin had only been onboard a couple of days, and he was the single guy to suit us all up and get us out the door. Hundreds of steps in that procedure, and you really can’t screw it up, because you’re essentially putting your buddy into a spacesuit and opening the hatch and putting them out into vacuum. Kevin did an outstanding job, for having been on Space Station only maybe two days before that happened. Poor guy, I think he had his Soyuz socks on for about a whole week because he never had time to actually change his clothes and find all his new clothes up there. We drove him a little crazy with getting stuff ready to go to get us outside, to hopefully fix that radiator leak. We fixed it for a little while, but it wasn’t the prime cause of the radiator leak. So later, on another Expedition, they ended up doing a further-on step to fix the radiator leak. Pretty interesting how normal, whatever, mundane Expeditions are going to turn into pretty crazy procedures and things that you’re going to do on the fly. I think everybody’s trained and ready for that, set for that, and happy to do as much as we can to make sure the Space Station is going to keep flying for a long time,

Ross-Nazzal: Would you talk about how Station has changed or evolved since you first became involved, and any contributions or ideas that you came up with that resulted in some changes?

Williams: Oh, boy. Me alone, I don’t know, I’m not that smart. So many people worked on this amazing project.

Ross-Nazzal: Or your involvement in the changes, I guess.

Williams: You know, one of the things that I think is most impressive, and I could pretty much recount every flight of the Space Station, because our class got here, like I mentioned, right in the beginning. Now it’s full up and going and a huge laboratory. I think one of the most interesting things is, I never thought, as we were getting trained for it, that all these things were going to actually happen. I’m like, “Eh, we’ll see when that happens.” I guess maybe it goes back to even just launching into space, but I’ve become a believer. If you watch the assembly sequence in rapid succession on a computer program or watch the different flights of how the Space Station morphed, I call it Mr. Potato Head, because we had to put things in a certain way in the beginning as temporary power and temporary heating and cooling, for example, and then switch it around as we were building one piece after another onto itself, onto the Space Station. I think it’s pretty incredible to see this thing. We’ve lived in it through all these changes, and for those Expeditions, all the way up to assembly complete, we had to learn a bunch of different power configurations of the Space Station. During this flight it’s going to be like this, during that flight it’s going to be like this, and this time it’s going to be like this. It was hard to wrap your head around that, and I think one of the amazing things are the people who wrote all the procedures. I was part of the procedure validation team in the beginning, and then luckily part of the group that did a lot of the procedures as we trekked along through the assembly sequence. For those guys that continually crank out the procedures, working hand-in-hand with the controllers, who understood how the technical parts of the Space Station were changing and when and how those are important to the emergency procedures, for example, and in periods of loss of communication, how the crew was going to handle any types of malfunctions, those guys must have had to pull their hair out. They were working night and day to update those procedures, get them onboard, get them printed, get pieces that had to be placarded, make sure folks understood what the egress paths were with different spacecraft, Soyuz and Space Shuttle, and where they were docking, because the docking ports were changing at the time, too. That was a mountain of work and pretty incredible. I think hand-in-hand with that was the EVA guys. We had a pretty big, good plan about how we were going to do all of these—or that there were going to be a lot of spacewalks to put these pieces and parts together, but actually to execute them and have all those procedures done and tested out in the NBL [Neutral Buoyancy Lab] and thinking to the nth degree the things that can go wrong, and trying to solve all those things—we call it an EVAD [phonetic]—before they actually even launch the crew into space, is pretty incredible. I’d say the teams that went behind all of that assembly are pretty awesome. Lastly, I would say the faith of the investigators, because it was a construction project for a decade, and some of the investigators hung it out through that whole time and sent up small parts of their experiments or at least got them working and put them in a shape and a form so that they could be launched in an MPLM [Multi-Purpose Logistics Module], in a Shuttle, in a Soyuz, or however the pieces and parts were going to go up there. That faith that they’re actually get up there and then we were going to do the science, I think their persistence and their tenacity for hanging in there has opened up the Space Station to so many other people now that it’s complete. You’ve got universities, school kids, scientists all over the world interested in doing science on the Space Station, and I think it’s a tribute to those initial guys who really said, “Oh, we can handle this, we can do this.” A lot of different people have been a huge part of this program.

Ross-Nazzal: What do you think are some of the decisions that you believe greatly impacted the Space Station, policy or budget or what have you?

Williams: Interesting. I think its legacy is the trust with the partner agencies, and I think sometimes we were forced into that. Sometimes we worked so hard to make it happen by setting up procedures. “This is how all the procedures are going to be written,” and the arguments that ensue about that, and the waivers that have to happen because somebody can’t do that. We’re working hard to try to make that work. Then something major happens, like the Columbia accident, and you go from rotating crews on the Shuttle to rotating crews on the Soyuz, and you have to really take a leap of faith, of trust, in good faith your partner’s going to come and take up the slack for you and help your program get back on its feet. I think those things happen throughout the history of the Space Station program that have made us all a little bit closer, have gotten us to the next step of trying to trust each other. I think those are some of the things that you try to force at some point in time, and then they just happen. I think those are the most significant. So when people ask me about the International Space Station, yes, of course I say the science is really important, but I think the relationships, the trust from one agency to the next, the transparency that we have with each other, I think that’s the most significant parts of the International Space Station.

Ross-Nazzal: So you think Columbia had a tremendous impact on International Space Station?

Williams: Yes, I do. I think when they were launching—I had my head down, trying to get ready for my Expedition with 12A.1—I didn’t understand all of the experiments that they had onboard. On my second flight, when I really was onboard the Space Station as a science laboratory, a lot of those things were like, “Oh yes, this was initially tested on 107, and this was part of 107, dah dah dah.” And I was like, “Wow, they were really”—that flight was a long flight with a, not a SPACEHAB.

Ross-Nazzal: I think it was a SPACEHAB.

Williams: It was a SPACEHAB onboard? We had a SPACEHAB, but that was filled with cargo. So they had a SPACEHAB as a laboratory. With the SPACEHAB and all the experiments there to really ramp up and prove out some of these processes and theories that they thought we were going to use for the Space Station, and obviously they did. So pivotal as a way that forced all of us in the space industry to turn around and take a look at what we were doing and trust ourselves, as well as use what they did during their flight to turn around and take those experiments and put them on the International Space Station. I guess I’m the glass half-full type of guy, right? You’ve got to look at things in a positive light, and I think they really contributed to the Space Station.

Ross-Nazzal: Can you share with me any sort of organizational or technical lessons learned from Space Station?

Williams: Let me think about that for a second. I’m thinking of something that will pop out in my head.

Ross-Nazzal: To me, that’s the more difficult kind of question to think about on the fly.

Williams: Well, you know, I think one of the interesting things about the Space Station is it looks all shiny and pretty and new, but it’s a little bit of a kluge. Hate to say that for a history project, but it is, because it’s a lot of different partners and their ideas put it together. I think one of the cool things was, we were able to at least share with each other the technical information of how these things work together, how do they communicate, how does the guidance navigation control system on one end of the Space Station communicate with the other, how does the communication system of all these different countries actually work together. Technically, everything does work, but it’s not ideal. I think everybody who’s gone up and lived on the Space Station cracks up, like why is it called a light in here, and here it’s called some illuminating event or something like that. I’m making it up a little bit, but there’s different nomenclature for the same darn thing in one module and the other, you want to pull your hair out and scream a little bit. I think one of the coolest and in-your-face examples is every module to module is like that, and every spacesuit to spacesuit, like from the Sokol suit to the ACES [Advanced Crew Escape] suit, to the Orlan suit to the EMU [Extravehicular Mobility Unit], they’re all different. I think the International Space Station allows all of us on the ground, as well as in space, to look at all these different ways of solving a problem and pick out the good parts of it, pick out the bad parts too, and then hopefully design the next generation of spacecraft or spacesuit a little smarter, a little better, a little more comfortable, a little more user-friendly, whatever it is. I think that is another really key aspect of the Space Station. I think we were actually, another happenstance, lucky not to convince each other to do exactly the same thing. We’re actually lucky to put up all these different ways of doing things, so every partner gets the ability to take an evaluation and come out of that with a way that they might want to do something a little bit better next time. Because we’re not going to have the Space Station forever, it’s only a stepping-stone to help us build the next space program, space project, and I think we’ll do it better for our next generation of explorers.

Ross-Nazzal: Were there any things that you pointed out coming back from your Expeditions that you know got changed as a result?

Williams: Well, we have not landed in a capsule in a United States spacecraft for quite some time, and I think we have forgotten some of those hard as you hit the ground lessons to learn about that. Or maybe it’s just been a little while. Now, coming into the suit-seat design of the new spacecraft, commercial spacecraft, that are coming out, Boeing and SpaceX, as well as Orion, I look at that stuff a little bit more closely, having lived through a landing in a capsule under a parachute. It’s significant. It’s different than landing on a runway in a pseudo-glider airplane of the Space Shuttle. How we design that protective equipment in light of this, we’re in the twenty-first century here, where we can actually design things better and smarter. So the fact that there’s another group of people, the Russians, who are landing on the ground under a parachute, and how they design their suit and their seat mixture, and then how we’re going to do it in the future with new technologies, I think there’s a lot to be learned, to be passed around, and discussed, and talked about, and remind ourselves that we can actually do it a lot better than we used to do it in the Mercury-Apollo-Gemini time frame. I think we’re in a state right now that we’re able to take advantage of all those lessons learned. That’s just an example. That’s just a launch and landing suit. We’ve learned a lot with the EMU capabilities of how we’ve brought things back home to Earth and fixed them and changed them, and then sent them back to space. Well, if we’re going to actually have people live in space for a long period of time, they’re going to have to have spacesuits that they’re going to have to be able to repair or make modifications to up there, or easily plug and play—along with that easily plug-and-play type of equipment, how to make things advanced easier in the future, not one-time spacecraft. You’re going to have to design a spacecraft that’s going to be able to be upgradable, like computers nowadays. We’re really taking advantage of technologies that have happened over the last thirty to forty years as changing the mission that we’re going to be doing, and we can use the Space Station to help us make these things better and smarter, I think, and safer.

Ross-Nazzal: What are some of your more memorable memories from Space Station?

Williams: I think some of the best times up on the Space Station are having to do with just interacting with the people onboard. Spacewalks, of course, are pretty awesome, and that makes you stop and think, but it’s actually the part of coming back in that, to me, always left an impression. I’m like the horse going back to the barn a little bit. Getting suited up, getting ready for a spacewalk, it’s all fun and you’re excited and you’re ready to go, but coming back in, I was sort of tick-tock. I want to make sure all the Ts are crossed; all the Is are dotted. We have to make sure everything’s back in. [It’s] serious now. After getting in, closing the hatch, and getting out of your spacesuit, then you can relax again, seeing the faces all around you of the people that are there to support you. On our long spacewalk, for example, Yuri and Gennady, who really had no real role in getting us out of the spacesuits or getting us back inside, were there because they knew it was a long spacewalk. They’ve done that. They’ve been part of history in creating their parts of the Space Station, so they were ready to say, “Here, you want a hot cup of tea?” when [we came] in. I think those types of things are really special. I remember when Misha and L.A. came in from, I think it was Misha’s first spacewalk or second spacewalk, he was really tired, and to just sit down and have dinner with those guys and reflect about where you are and what we all just did out there, and what we’re doing up there, I think is pretty special. I think the dinner table is key, and it revolves around some of the highlights of the mission, things that are spectacular, and it brings you back. Sort of like here at work, you’re like, “Ah, it’s just another day at the office.” And then something amazing happens and it makes you just stop for a minute and sit down with your friends in the cafeteria and go, “My god, I got to put a spacesuit on today. That’s pretty neat. I got to fly the Boeing CST-100 in a rendezvous sim, that’s pretty cool.” But it’s not every day. It takes those highlight things and then it brings you back, and you just go, “We’re just a bunch of knuckleheads. How did we get to do that? That’s pretty neat.” And in space, it happens, it really happens. We launched these Japanese satellites, these micro-satellites, nano-sats, and Aki was the man. He was putting them all together, and we made him show us everything that was going on. It was just me and him and Yuri at the time. He was pressing the button, which meant, unfortunately for him, he wasn’t in the window watching it. Me and Yuri were in the window, and we had the cameras poised and ready. We’re sitting there, and you can imagine what this is going to be like. Then these things come shooting out of the end of the robotic arm, and we’re like [makes camera clicking noises] trying to take pictures as fast as we can. And we’re like, “That was cool! We just launched little satellites.” It just so happened that; I think it was on the fiftieth anniversary of Sputnik, it was in October, and it was like, “That is pretty neat. Where are we in time, that’s pretty cool.” I don’t know, those neat things that you get to do, then you get to reflect on them while you’re up there. Those things are fun.

Ross-Nazzal: What do you think are some of your more significant challenges that you faced?

Williams: Broken toilets.

Ross-Nazzal: That doesn’t sound very fun, especially up there.

Williams: Well, you know, and I’m joking around by saying that, but I think the biggest challenge for me, particularly now that I’m reflecting on it, is we have things that break and we don’t know as much about them potentially as we should. We spend a lot of time discussing with the ground what the problem will be. A lot of things are very complicated. Even the toilet system is complicated, and there’s a lot of analysis that goes on, and that trickles down into logistics: how many parts are up there, how many times you can trade things out, and let’s trade space, whether or not this is a good idea, a bad idea, how many toilets do we have, blah blah blah. Anyway, I think the challenge is we spend a lot of time relying on the ground. I think when we’re taking that next step and hopefully the Space Station will allow us to, now as a laboratory, start taking those steps, getting a little bit more divorced from the ground and coming up with systems and processes like water reclamation or changing drinking water, making drinking water again. All of that has to be able to be solved up in space. It goes hand-in-hand with, like I was saying, future suits, future equipment. I think we have to start divorcing ourselves a little bit from relying on the ground if we’re going to take those bigger steps, make a space station on the Moon, take a trip to an asteroid, take a trip to Mars. I think the Space Station is a great place to do that, and it’s a little bit frustrating up there about how reliant we are on the ground, but the Space Station is a pretty complicated piece of equipment.

Ross-Nazzal: You mentioned how many toilets do we have, so I have to ask you, just because [I’m] curious, how many toilets are there on Space Station? Do you have backups?

Williams: There’s two, one on the Russian end and one on the U.S. end. When I was up there for my first flight there was only one. We added the second one when we got six people. That was one of the criteria. When we were up there for my first flight, we had direct handovers, so two Soyuz there together, six people. It was quite a line at the toilet when you’re waiting for the morning rush to get there with only one toilet. For example, right now we have nine people onboard with only two toilets. It is a little bit of a waiting game, who’s going to go where, and things like that, and if we’re using the urine to get reclaimed into water again. So when one toilet goes down and you have to take the long trip down the other end of the Space Station to the other toilet, it’s a little bit of a pain. But we all sort of compensate somehow.

Ross-Nazzal: That’s interesting. I never really thought about toilets before, until you mentioned it. So what do you think has been your most significant contribution to Station?

Williams: I think probably my most significant contribution is being not a real scientist. I say that because I really don’t have a lot of preconceived notions about how things are going to happen. It’s a unique environment, because there’s a lot of people who can hypothesize how things are going to work in microgravity, but it may or may not come true. I think one of the greatest contributions that anybody has is to be an open-minded observer. So when you’re doing an experiment, or even when you’re working on a piece of equipment, just putting something together, as we call it, IFM, in-flight maintenance, something may or may not work like the people on the ground had expected. Rather than force things to happen the way the people on the ground planned, if it doesn’t happen that way, I was very open to this to say, “Hey, that doesn’t work,” and question myself: is it me, or is it maybe the way the experiment is set up? Ask that question to the ground, and take note of it, and you might stumble onto something that nobody’d ever thought about. That happened with capillary flow. On one of the experiments there, they had never predicted a wicking angle of such-and-such, I don’t remember exactly what it was, but as soon as we got it wedged to a certain degree, the fluid took off and went somewhere. I was like, “Oh no, I did something wrong.” I called them back and I said, “Hey, can I reverse this? Because this looked like I did something wrong here.” They’re like, “No, wait a minute, wait a minute. Let us look at the video and see what happened.” Lo and behold, they had never planned on that happening, and that shaped some new math equations that they were going to do to pass on. I think for myself, that’s the best way to go about things, just be an open observer of things that are happening. Because you have to remember, you’re in a really unique environment, and nobody really knows how space works until you get up there and try it.

Ross-Nazzal: Wasn’t that the point of science, was just to be an observer and document it?

Williams: Yes, exactly.

Ross-Nazzal: We have a couple more minutes, so I thought I would ask—you’re a runner, and you did the marathon in space, and you also did a triathlon in space, which I thought was interesting. So where did those ideas come from, to do that on the Station?