- Understanding Poverty

- Competitiveness

Tourism and Competitiveness

- Publications

The tourism sector provides opportunities for developing countries to create productive and inclusive jobs, grow innovative firms, finance the conservation of natural and cultural assets, and increase economic empowerment, especially for women, who comprise the majority of the tourism sector’s workforce. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism was the world’s largest service sector—providing one in ten jobs worldwide, almost seven percent of all international trade and 25 percent of the world’s service exports —a critical foreign exchange generator. In 2019 the sector was valued at more than US$9 trillion and accounted for 10.4 percent of global GDP.

Tourism offers opportunities for economic diversification and market-creation. When effectively managed, its deep local value chains can expand demand for existing and new products and services that directly and positively impact the poor and rural/isolated communities. The sector can also be a force for biodiversity conservation, heritage protection, and climate-friendly livelihoods, making up a key pillar of the blue/green economy. This potential is also associated with social and environmental risks, which need to be managed and mitigated to maximize the sector’s net-positive benefits.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been devastating for tourism service providers, with a loss of 20 percent of all tourism jobs (62 million), and US$1.3 trillion in export revenue, leading to a reduction of 50 percent of its contribution to GDP in 2020 alone. The collapse of demand has severely impacted the livelihoods of tourism-dependent communities, small businesses and women-run enterprises. It has also reduced government tax revenues and constrained the availability of resources for destination management and site conservation.

Naturalist local guide with group of tourist in Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve Ecuador. Photo: Ammit Jack/Shutterstock

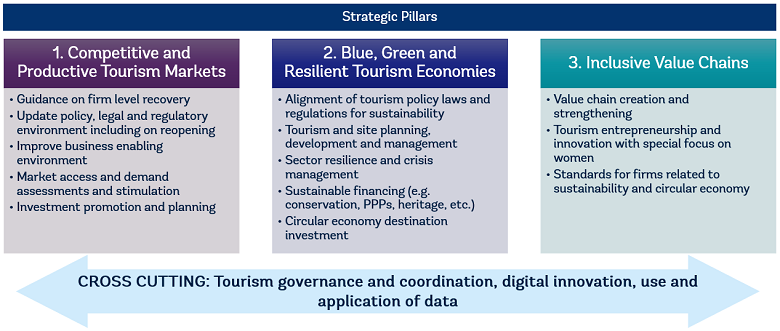

Tourism and Competitiveness Strategic Pillars

Our solutions are integrated across the following areas:

- Competitive and Productive Tourism Markets. We work with government and private sector stakeholders to foster competitive tourism markets that create productive jobs, improve visitor expenditure and impact, and are supportive of high-growth, innovative firms. To do so we offer guidance on firm and destination level recovery, policy and regulatory reforms, demand diversification, investment promotion and market access.

- Blue, Green and Resilient Tourism Economies. We support economic diversification to sustain natural capital and tourism assets, prepare for external and climate-related shocks, and be sustainably managed through strong policy, coordination, and governance improvements. To do so we offer support to align the tourism enabling and policy environment towards sustainability, while improving tourism destination and site planning, development, and management. We work with governments to enhance the sector’s resilience and to foster the development of innovative sustainable financing instruments.

- Inclusive Value Chains. We work with client governments and intermediaries to support Small and Medium sized Enterprises (SMEs), and strengthen value chains that provide equitable livelihoods for communities, women, youth, minorities, and local businesses.

The successful design and implementation of reforms in the tourism space requires the combined effort of diverse line ministries and agencies, and an understanding of the impact of digital technologies in the industry. Accordingly, our teams support cross-cutting issues of tourism governance and coordination, digital innovation and the use and application of data throughout the three focus areas of work.

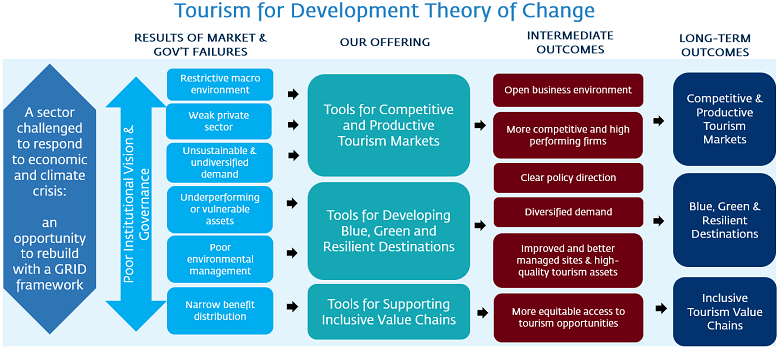

Tourism and Competitiveness Theory of Change

Examples of our projects:

- In Indonesia , a US$955m loan is supporting the Government’s Integrated Infrastructure Development for National Tourism Strategic Areas Project. This project is designed to improve the quality of, and access to, tourism-relevant basic infrastructure and services, strengthen local economy linkages to tourism, and attract private investment in selected tourism destinations. In its initial phases, the project has supported detailed market and demand analyses needed to justify significant public investment, mobilized integrated tourism destination masterplans for each new destination and established essential coordination mechanisms at the national level and at all seventeen of the Project’s participating districts and cities.

- In Madagascar , a series of projects totaling US$450m in lending and IFC Technical Assistance have contributed to the sustainable growth of the tourism sector by enhancing access to enabling infrastructure and services in target regions. Activities under the project focused on providing support to SMEs, capacity building to institutions, and promoting investment and enabling environment reforms. They resulted in the creation of more than 10,000 jobs and the registration of more than 30,000 businesses. As a result of COVID-19, the project provided emergency support both to government institutions (i.e., Ministry of Tourism) and other organizations such as the National Tourism Promotion Board to plan, strategize and implement initiatives to address effects of the pandemic and support the sector’s gradual relaunch, as well as to directly support tourism companies and workers groups most affected by the crisis.

- In Sierra Leone , an Economic Diversification Project has a strong focus on sustainable tourism development. The project is contributing significantly to the COVID-19 recovery, with its focus on the creation of six new tourism destinations, attracting new private investment, and building the capacity of government ministries to successfully manage and market their tourism assets. This project aims to contribute to the development of more circular economy tourism business models, and support the growth of women- run tourism businesses.

- Through the Rebuilding Tourism Competitiveness: Tourism Response, Recovery and Resilience to the COVID-19 Crisis initiative and the Tourism for Development Learning Series , we held webinars, published insights and guidance notes as well as formed new partnerships with Organization of Eastern Caribbean States, United Nations Environment Program, United Nations World Tourism Organization, and World Travel and Tourism Council to exchange knowledge on managing tourism throughout the pandemic, planning for recovery and building back better. The initiative’s key Policy Note has been downloaded more than 20,000 times and has been used to inform recovery initiatives in over 30 countries across 6 regions.

- The Global Aviation Dashboard is a platform that visualizes real-time changes in global flight movements, allowing users to generate 2D & 3D visualizations, charts, graphs, and tables; and ranking animations for: flight volume, seat volume, and available seat kilometers. Data is available for domestic, intra-regional, and inter-regional routes across all regions, countries, airports, and airlines on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis from January 2020 until today. The dashboard has been used to track the status and recovery of global travel and inform policy and operational actions.

Traditional Samburu women in Kenya. Photo: hecke61/Shutterstock.

Featured Data

We-Fi WeTour Women in Tourism Enterprise Surveys (2019)

- Sierra Leone | Ghana

Featured Reports

- Destination Management Handbook: A Guide to the Planning and Implementation of Destination Management (2023)

- Blue Tourism in Islands and Small Tourism-Dependent Coastal States : Tools and Recovery Strategies (2022)

- Resilient Tourism: Competitiveness in the Face of Disasters (2020)

- Tourism and the Sharing Economy: Policy and Potential of Sustainable Peer-to-Peer Accommodation (2018)

- Supporting Sustainable Livelihoods through Wildlife Tourism (2018)

- The Voice of Travelers: Leveraging User-Generated Content for Tourism Development (2018)

- Women and Tourism: Designing for Inclusion (2017)

- Twenty Reasons Sustainable Tourism Counts for Development (2017)

- An introduction to tourism concessioning:14 characteristics of successful programs. The World Bank, 2016)

- Getting financed: 9 tips for community joint ventures in tourism . World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and World Bank, (2015)

- Global investment promotion best practices: Winning tourism investment” Investment Climate (2013)

Country-Specific

- COVID-19 and Tourism in South Asia: Opportunities for Sustainable Regional Outcomes (2020)

- Demand Analysis for Tourism in African Local Communities (2018)

- Tourism in Africa: Harnessing Tourism for Growth and Improved Livelihoods . Africa Development Forum (2014)

COVID-19 Response

- Expecting the Unexpected : Tools and Policy Considerations to Support the Recovery and Resilience of the Tourism Sector (2022)

- Rebuilding Tourism Competitiveness. Tourism response, recovery and resilience to the COVID-19 crisis (2020)

- COVID-19 and Tourism in South Asia Opportunities for Sustainable Regional Outcomes (2020)

- WBG support for tourism clients and destinations during the COVID-19 crisis (2020)

- Tourism for Development: Tourism Diagnostic Toolkit (2019)

- Tourism Theory of Change (2018)

Country -Specific

- COVID Impact Mitigation Survey Results (South Africa) (2020)

- COVID Preparedness for Reopening Survey Results (South Africa) (2020)

- COVID Study (Fiji) (2020) with IFC

Featured Blogs

- Fiona Stewart, Samantha Power & Shaun Mann , Harnessing the power of capital markets to conserve and restore global biodiversity through “Natural Asset Companies” | October 12 th 2021

- Mari Elka Pangestu , Tourism in the post-COVID world: Three steps to build better forward | April 30 th 2021

- Hartwig Schafer , Regional collaboration can help South Asian nations rebuild and strengthen tourism industry | July 23 rd 2020

- Caroline Freund , We can’t travel, but we can take measures to preserve jobs in the tourism industry | March 20 th 2020

Featured Webinars

- Destination Management for Resilient Growth . This webinar looks at emerging destinations at the local level to examine the opportunities, examples, and best tools available. Destination Management Handbook

- Launch of the Future of Pacific Tourism. This webinar goes through the results of the new Future of Pacific Tourism report. It was launched by FCI Regional and Global Managers with Discussants from the Asian Development Bank and Intrepid Group.

- Circular Economy and Tourism . This webinar discusses how new and circular business models are needed to change the way tourism operates and enable businesses and destinations to be sustainable.

- Closing the Gap: Gender in Projects and Analytics . The purpose of this webinar is to raise awareness on integrating gender considerations into projects and provide guidelines for future project design in various sectoral areas.

- WTO Tourism Resilience: Building forward Better. High-level panelists from Sri Lanka, Costa Rica, Jordan and Kenya discuss how donors, governments and the private sector can work together most effectively to rebuild the tourism industry and improve its resilience for the future.

- Tourism Watch

- [email protected]

Launch of Blue Tourism Resource Portal

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

An analysis of the competitiveness of the tourism industry in a context of economic recovery following the COVID19 pandemic

José antonio salinas fernández.

a Dpt. of International and Spanish Economy, Universidad de Granada, c/ Paseo de Cartuja, 7, 18011 Granada Spain

José Manuel Guaita Martínez

b Department of Economics and Social Sciences, Universitat Politècnica de València, c/ Camino de Vera s/n, 46022 Valencia Spain

José María Martín Martín

Business activities within the tourism industry are especially suffering from the consequences of the COVID19 pandemic. Those countries whose economy depends largely on tourism will experience a troublesome situation for years to come. Their return to a normal situation will be conditioned by the competitiveness of their tourism sector. The study begins by pinpointing the countries that have been more hardly stricken by the pandemic and in which tourism accounts for a greater share of the GDP. A comparative analysis of the competitiveness of these countries with that of world-leading countries will be carried out so as to conclude which will face the recovery period in a more vulnerable situation. The measurement of tourism competitiveness will be supported by the creation of a synthetic indicator based on the P 2 distance method. A group of 13 countries has been identified as the most vulnerable, and it is advisable to act urgently in the following areas: the promotion of cultural elements and the historical and artistic heritage, the protection of natural areas, the availability of information and communication technologies, the international openness of the destination, and the availability of transportation infrastructures and tourist services.

1. Introduction

COVID-19 was officially declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 12, 2020. This pandemic has had significant impacts on the global economy, as a result of the containment measures adopted ( Sigala, 2020 ). One of the most affected sectors has been tourism, at the end of December 2020 it was confirmed that international tourist arrivals fell by 72% in the first ten months of 2020 ( UNWTO, 2020 ). The tourism industry has traditionally been highly sensitive to socio-economic, political and environmental risks, yet it is also a very resilient industry ( Novelli, Gussing, Jones and Ritchie, 2018 ; Jiménez, Martín and Montero, 2014 ). It is true that, in recent decades, the tourism industry has faced several crises —terrorism, earthquakes, Ebola, SARS, Zika— but it is understood to some extent that the current crisis is not comparable to those mentioned. The reason behind this is that, in previous pandemics, mass tourism was not developed in the way it is today and it was not until the 1960s that it became a global phenomenon ( Menegaki, 2020 ). Additionally, a number of health crises that have affected the tourism industry in recent years, such as SARS, did not develop into a pandemic ( Chen, Jang and Kim, 2007 ; Henderson and Ng, 2004 ). The unfolding events make us think that this crisis, besides being different from the previous ones, can bring about deep long-term changes in tourism ( Sigala, 2020 ). Some researchers have pointed out that a crisis like this may lead to the emergence of nationalist sentiments or a rejection of foreigners ( Donthu and Gustafsson, 2020 ), even fear associated with the transmission of pathogens by tourists ( Hall, 2020 ; Seong and Hong, 2021 ). In this regard, media broadcasting can influence the behavior of tourists and citizens’ attitudes during the recovery process. ( Kantar, 2020 ).

Based on the scientific production on the impact of Covid-19 on economic activities, three main lines of research can be defined: "Changes in society's consumption habits", "Impact on the public health management model" and "Economic effects of Covid-19 on business organisations" ( Carracero et al., 2021 ). The far-reaching changes that the tourism industry is undergoing and the expected long -term repercussions point towards a major economic impact. The decrease in tourism activity is expected to be the most intense in history, seven times greater than that resulting from the September 9 th terrorist attacks ( UNWTO, 2020 ). This impact, although unpredictable, derives from the great importance of tourism as an economic activity for many countries, given that it is a great source of employment and wealth: 1 out of every 10 jobs are directly or indirectly related to tourism ( UNWTO, 2020 ) and responsible for 10.3% of the world's GDP ( WTTC, 2020 ). This figure is much higher in the countries that have turned this activity into the center of their development strategy, which has resulted in a great dependence upon such an activity ( Martín, Salinas, Rodríguez and Ostos, 2020 ; Martín and Guaita, 2019 ). The strong growth of tourism at an international level ( Gómez-Vega and Picazo-Tadeo, 2019 ), has made this activity surpass economic sectors that had traditionally been the economic backbone of some countries ( Mendola and Volo, 2017 ). In fact, tourism plays a central role in the development strategies of many developing countries ( Joshi, Poudyal and Larson, 2017 ; Martín, Guaita and Burgos-Mascarrell, 2019 ). As such, the collapse of tourism as a result of the pandemic and its consequences in the medium and long term will strongly impact the economies that are highly dependent on tourism.

The competitiveness of the tourism sector in each country determines the strength of this activity, its capacity to attract flows of visitors, and, ultimately, its ability to generate wealth ( Guaita, Martín and Salinas, 2020 ). Therefore and, now more than ever, the degree of competitiveness of the different countries will be key for the recovery of the tourism industry. The pandemic has increased the gap between countries and it is expected that those with a better competitiveness will be facing the outcome of the pandemic with greater guarantees ( Sigala, 2020 ). This paper focuses on this issue, as it aims to identify which countries are the most vulnerable in view of the crisis in the tourism industry and the expected recovery. To this end, we will use three separate datasets: the weight of tourism in the country's economy, the impact of COVID19 in the country, and the degree of competitiveness of its tourism industry. This analysis will make it possible to point out the main weaknesses of the countries in terms of tourism competitiveness, but it also proposes to identify the dimensions of competitiveness on which the most vulnerable tourism destinations should focus their efforts in order to improve their position. This analysis, not carried out so far, offers a valuable contribution to the academic literature as well as contributing to the improvement of the knowledge needed for the recovery phase. In relation to previous academic literature, this analysis provides the first assessment of tourist destinations by comparing the data on competitiveness, the weight that tourism has on their GDP and the impact of the pandemic. This study identifies the specific areas that need strengthening in order to improve the situation of the most vulnerable countries. This is an entirely new contribution to the literature, as well as the way in which this analysis is carried out. In particular, it is based on a synthetic DP2 indicator designed to measure tourism competitiveness. This study provides both a framework for future analysis and an opportunity to monitor the situation. It also offers a clear contribution to the academic literature on the vulnerability of tourist destinations and their recovery after crisis situations. This can be of great use in defining public policies to strengthen the situation of the most vulnerable destinations, even ahead of crisis situations.

Measuring tourism competitiveness is a controversial and complex issue ( Abreu-Novais, Ruhanen and Arcodia, 2018 ; Salinas, Serdeira, Martín and Rodríguez, 2020 ). Several proposals have been made without a clear consensus ( Mazanec and Ring, 2011 ). In this work, we have chosen to measure tourism competitiveness based on the pillars indicated by the Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index (TTCI) ( World Economic Forum, 2017 ). Although the final model for aggregating information is based on the P 2 Distance (DP2) method defined by Pena (1977) . This method allows for the creation of a synthetic indicator that overcomes many of the problems associated with this kind of procedure ( Rodríguez, Martín and Jiménez, 2018 ) and has been used in several studies related to the tourism industry (Rodríguez, Aguilera, Martín and Fernández, 2018 ). Based on this proposal, two research questions are posed. RQ1: Which countries are the most vulnerable in a context of crisis in the tourism industry? RQ2: In what dimensions of competitiveness should they work to improve such a situation? This will help to bridge the research gap identified in the academic literature, which advises to conduct studies that include proposals to manage this crisis ( Sigala, 2020 ). Academic research should provide useful information on the necessary transformations to be made in the tourism sector so as to address the sanitary crisis ( Lew, 2020 ).

The paper is structured as follows: first, after outlining the research gap and the research questions in the introduction, a review of the academic literature on the role of competitiveness in the tourism industry is provided. Next, we describe in detail the methodology used to create the synthetic indicator and the procedure to determine which variables offer the greatest discriminatory power. In the following section, we report on the results obtained in accordance with the initial objectives. Finally, the conclusions section presents the implications of the results of the study, its limitations, recommendations, and future lines of research.

2. Competitiveness as a vaccine for the crisis of the tourism industry

Once acknowledged the historical crisis that the tourism industry is and will continue to experience, some authors point it out as a transformative opportunity ( Mair, 2020 ). As seen in other sectors, tourism should be re-imagined and reshaped for the new normal ( McKinsey and Company, 2020 ). Crises can be a trigger for change, but no crisis has meant to date a significant transitional event for tourism ( Hall, Scott and Gössling, 2020 ). It is estimated that the tourism industry has lost 2.7 trillion USD in 2020. The most affected region is Asia-Pacific, with 63.4 million jobs lost. In Europe, job losses are estimated at 13 million ( European Data Portal, 2020 ). We can expect the pandemic to have a more lasting effect on international tourism, while other sectors will recover more quickly. Things will be especially sensitive in the countries whose economies are highly dependent on tourism, where it is crucial to monitor the situation closely and implement measures to protect this industry and mitigate the impact of the crisis ( European Data Portal, 2020 ). Therefore, it is important to generate helpful knowledge in order to promote transformations that strengthen the tourism sector and make it more competitive, otherwise it will simply be hit by successive crises ( Lew, 2020 ; Sigala, 2020 ). The crisis derived from this pandemic is highlighting weaknesses and bad practices in the tourism industry; indeed, the way in which its effects are felt could be associated with the characteristics of the growth model itself ( Ötsch, 2020 ). The chain of events that has occurred since the beginning of the crisis can be traced back to processes of large-scale urbanization, changes in the environment, and a highly interconnected world, among others (Allen, Murray, Zambrana-Torrelio, Morse, Rondinini, Di Marco, Breit, Olival, and Daszak, 2017 ). The future of the tourism industry is uncertain, given that the real impact of the pandemic in the medium and long run has yet to be determined. It is possible that a feeling of rejection towards tourism and the tourists themselves may arise from sanitary concerns. ( Donthu and Gustafsson, 2020 ; Hall, 2020 ; Seong and Hong, 2021 ). Hence the importance of planning adequate and effective recovery policies that address aspects related to the very nature of this pandemic, which is different from previous crises in the sector ( Strielkowski, 2020 ; Lew, 2020 ). In fact, one of the main lines of research that has gained momentum in the context of the pandemic focuses on the study of its economic impact ( Carracero et al., 2021 ). Therefore, at this point in time, the revival of the tourist activity is highly conditioned by the attitude of citizens and tourists ( Sigala, 2020 ; Seong and Hong, 2021 ). This differs from what has been observed in other periods of recovery, when tourist activity was linked only to economic recovery. Current forecasts point to the beginning of the recovery in the second half of 2021 ( UNWTO, 2020 ), as conditioned by the speed of vaccination and the effects of potential variants of the virus. The duration of the crisis may require profound changes in the sector, improvements in sanitation protocols and a strengthening of communication ( Chang et al., 2020 ), something for which the most competitive destinations will be better prepared. In fact, this paper's initial hypothesis assumes that: destinations that are more competitive will face the recovery in better conditions.

Bearing in mind the above, the years marked by the pandemic and the coming years after the start of mass vaccination campaigns will be extremely negative for the tourism sector. Such years will put the competitiveness of the countries to test, as it will have much to say in the race for recovery among countries. In order to progress on improving competitiveness, this concept must be correctly understood. Although it is a widely analyzed concept, there is a great deal of controversy surrounding its definition ( Mazanec, Wöber and Zins, 2007 ). The fact that there are numerous factors influencing the competitiveness of a destination makes it difficult to come up with a definition ( Gooroochurn and Sugiyarto, 2005 ; Croes and Kubickova, 2013 ). The different definitions proposed have focused on a number of aspects associated with the competitiveness of a destination. Thus, a destination will be more or less competitive depending on its ability to generate long-term benefits ( Buhalis, 2000 ), to maintain a favorable market position ( Hassan, 2000 ) and increase the economic welfare of the population ( Crouch and Ritchie, 1999 ). An updated perspective of competitiveness, which serves as a reference for this study, identifies tourism competitiveness as the optimization of the destination's resources, allowing for its development in a way that is compatible with the well-being of the locals and the preservation of resources ( Dupeyras and MacCallum, 2013 ; Martín, Guaita, Molina and Sartal, 2019 ). These same authors identify competitiveness with the optimization of the destination attractiveness, so as to gain market share. Based on this perspective, this paper analyzes the best optimization of resources for an appropriate development of tourism.

The analysis of tourism competitiveness, and therefore the assessment of the countries' situation, should consider the following dimensions: attractiveness and satisfaction with the destination, economic dimensions, dimensions associated with the well-being of the local population and sustainability ( Abreu-Novais et al ., 2018 ). In a context where it is key to reflect on the most appropriate strategies to gain in competitiveness, it is necessary to identify the factors that foster it ( De Castro, Fernández, Guaita and Martín, 2020 ; De Castro, Pérez-Rodríguez, Martín and Azevedo, 2019 ). The academic literature has described numerous factors that influence competitiveness, such as the following: basic resources and attractions, culture and the historical-artistic heritage, geography, climate or the planning of cultural or leisure events, tourism destination accessibility, transport and accommodation infrastructures, services for tourists, the willingness of the political authorities to implement a tourism-developing strategy, strategic management of the destination, human resources, service quality, marketing policies, investment-seeking, research and data treatment, international image, the level of security and safety, its location and proximity to other destinations, the cost-benefit relation, the carrying capacity, healthcare, political stability, socioeconomic relations with markets, cultural and religious matters, language, hospitality of the local residents, service excellence, quality experiences, the participation and involvement of all public and private agents in an efficient manner, the existence of continuous and transparent channels of communication, the balance between involvement and benefits for stakeholders, information management, tracking and monitoring competitiveness indexes, sustainable development policies, global strategic and marketing management, resources created by men, private competitiveness, government support, tourism demand-awareness, perception and preferences, among others (Ritchie and Crouch, 2003, 2010 ; Crouch and Ritchie, 2005 ; Heath, 2003 ; Dwyer and Kim, 2003 ). Although a long list of factors have been identified as influencing tourism competitiveness, there is no general consensus as to which are the most important ( Crouch, 2011 ).

If the definition of tourism competitiveness is not a simple task, even less so is its analysis. In the context of a crisis in the tourism industry —and subsequent recovery— it seems important to measure the level of competitiveness. At the same time, it is important to analyze which elements contribute to increasing the overall level of competitiveness, so that recovery policies take these factors into account and optimize resources ( Barbosa, Oliveira and Rezende, 2010 ). The problem of this type of analysis lies in the large number of variables that must be handled, some qualitative and others quantitative ( Kozak and Rimmington,1999 ; Guaita, de Castro, Pérez-Rodríguez and Martín, 2019 ). Usually, measuring tourism competitiveness has been based on the construction of synthetic indicators, which integrate the information of the variables with which we work ( Croes and Kubickova, 2013 ). The problems in this respect are related to the selection of the variables to be included and how they are aggregated, the availability of data, and the weighting of each variable. One of the most widespread proposals for analysis was issued by the World Economic Forum, which calculates the Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index every year (TTCI). This synthetic indicator is made up of 90 variables organized in 14 pillars. One of the shortcomings of this methodology is that it assigns the same weight to all variables, regardless of their importance or impact. In addition, this methodology does not reveal which factors have the strongest influence on the improvement of competitiveness, something that this work aims to accomplish. In this sense, several authors have noted the importance and usefulness of highlighting the factors that drive competitiveness ( Abreu-Novais et al ., 2018 ).

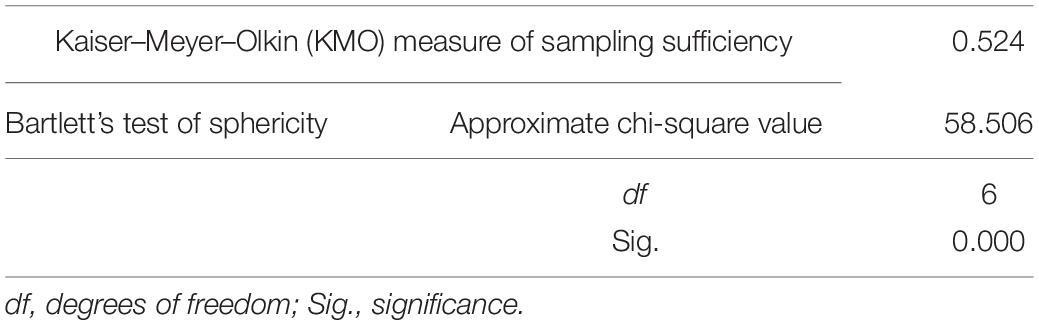

3. Methodology

Three data sets were used. First, the data needed to construct the synthetic indicator of tourism competitiveness (TTCI), provided by the World Economic Forum (WEF) in the 2019 edition. It provides 90 variables in total, all of which have been used for this study. The second data set refers to the impact of COVID19 in each country. The official data from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, up-to-date at the time of writing, were used for this purpose. These data reflect the cumulative incidence of the number of infected persons in relation to the country's population. The last set of data refers to the weight of the tourism industry in each country's GDP. Again, the data have been obtained from the WEF, and indicate the weight of tourism and transportation services in the total GDP of each country.

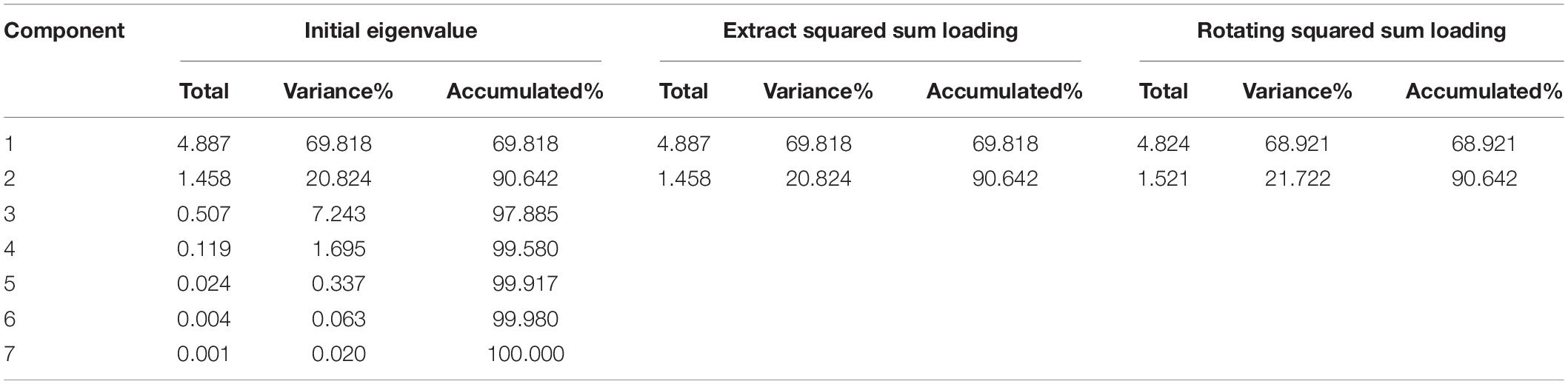

3.1. The DP 2 synthetic indicator

In this paper, Pena's P 2 distance method ( 1977 ) will be used to build a synthetic indicator of tourism competitiveness. In doing so, we will be able to classify a group of 80 countries whose tourism industry has a relevant presence in their economy. This indicator will identify the countries with the greatest vulnerability in the short and medium term, as a result of a higher number of cases of COVID-19 and for registering low levels of tourism competitiveness. The DP2 synthetic indicator —based on Ivanovic's (1974) distance— was developed by Pena (1977) by modifying the weighting of simple variables. To do so, the correlation coefficient was replaced by the determination coefficient, which operates as a corrective factor. As Somarriba and Pena (2009) point out the main advantages of the DP 2 synthetic indicator, compared to other aggregation methods such as Principal Components Analysis (PCA) or Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA), are: it eliminates the redundant information that simple variables incorporate when integrated into a synthetic indicator, it also avoids the arbitrary assignment of weights to simple variables, and solves problems related to the addition of variables expressed in different units ( Ribeiro-Navarrete, Marqués-Palacios, Martín and Guita, 2021 ). This methodology can be consulted in detail in Pena's ( 1977 ; 2009 ), Zarzosa's (1996 ; 2005 ) and Somarriba's ( 2008 ) publications and has been used by many researchers since then. Among the extensive collection of works that have used the P 2 distance method to construct synthetic indicators, those focused on welfare, quality of life, and economic and social development are the most relevant. However, in recent years, new applications have emerged in other fields or subjects, including tourism, mainly applied to the measurement of seasonality, sustainability, and competitiveness of tourist destinations. Among these works we find those of Pérez et al. (2009) , Lozano-Oyola et al. (2012) , Martín et al. (2017 , 2019 , 2020 ), Guaita et al. (2019) and Salinas et al (2020) .

Since one of the aims of our work is to measure the competitiveness of tourist destinations, the DP 2 synthetic indicator is best suited to determine the differences at a country level, since the deviation to a minimum is used as distance. This means that each country will be compared with a hypothetical baseline reference; that is, an imaginary country that shows the minimum value for all the variables —or simple indicators— thus yielding a value of zero on the DP 2 synthetic indicator. To solve the problem of variables expressed in different units of measurement, the standard deviation is used, converting them into abstract units ( Somarriba and Zarzosa, 2016 ).

According to Pena (1977) , the DP 2 indicator for a j th country is as follows:

- X ij is the value of i th variable in the j th country .

- d ij = ࣦ x ij – x i* ࣦ is the difference between the value taken by i th variable in the j th country and the minimum of the i th variable in the whole set of countries.

- n is the number of variables.

- σ i is the standard deviation of i th variable.

- R i , i −1, i−2, ……, 1 2 , is the determination coefficient in the regression of variable x i over x i -1, x i-2 , ….., x 1 already included, where R 1 2 = 0.

By using the determination coefficient ( R i , i − 1 . i − 2 , … 1 2 ) , we are measuring the proportion of the total variance of the variable x i explained by the linear regression with respect to the variables x i-1 , x i-2 ,…., x 1 , which are previously integrated in the synthetic indicator. As a result, Pena (1977) defined the "correction factor" as ( 1 − R i , i − 1 . i − 2 , … 1 2 ) , with the purpose of eliminating the duplicated information produced by the simple variables when they enter the synthetic indicator with respect to the preceding variables, due to the existing correlation between them. As Somarriba, Zarzosa and Pena (2015) report, the DP 2 indicator only includes the new information provided by each variable or simple indicator, eliminating that which is redundant. Therefore, the correcting factors act as weights for the variables, avoiding the need to assign weights arbitrarily. If there were no correlation between the variables, the weighting of these within the synthetic indicator DP 2 would be identical. Pena's works in 1977 and 2009 show that the DP 2 synthetic indicator verifies all the mathematical properties demanded by aggregation methods. For these properties to be fulfilled, all the simple variables must progress in the same direction, so that an increase in their value always means an improvement in the objective they intend to measure, in our case, tourism competitiveness. For this purpose, the variables whose increase implies a worsening of competitiveness must be multiplied by -1 before being incorporated into the synthetic indicator. The calculation of the DP 2 indicator follows an iterative process, whereby the entry of variables or partial indicators is ordered according to the amount of information they provide with respect to the phenomenon to be measured. To do this, the absolute correlation coefficient of each variable is used in relation to the constructed synthetic indicator, ordering the variables from highest to lowest correlation, following a series of iterations until a convergence is reached in the values of the DP 2 synthetic indicator, as described by Zarzosa (1996 and 2005 ).

3.2. Discrimination power of the variables and amount of individual relative information provided to the DP2 synthetic indicator

In addition to measuring the level of competitiveness of a group of tourist destinations, another important contribution of this methodology is the possibility of identifying the variables that provide greater individual relative information to the DP2 synthetic indicator. In so doing, it is possible to identify which dimensions of competitiveness are more decisive for explaining the variability of the indicator between the countries analyzed and, consequently, implement specific policies to make the tourist destination more competitive ( Rodríguez, Martín and Salinas, 2019 ). In order to calculate the amount of individual relative information provided by the variables, it is necessary to previously determine their discrimination power. For this purpose, we will use Ivanovic's Discrimination Coefficient (1974) , which expresses the degree of inequality in the distribution of the values of each simple variable for the 80 selected countries. It is defined as follows:

m is the number of countries in the set P

x ji is the value of the variable X i in country j and x li is the minimum value taken by variable X i in country l

m ji is the number of countries where the value of X i is x ji

X ¯ i is the average of X i

k i is the number of different values that X i takes in the set P.

The "Ivanovic-Pena Global Information Coefficient" is then calculated, combining the Ivanovic Discrimination Coefficient ( 1974 ) and the Pena correction factor ( 1977 ). With this coefficient, it is possible to know the global information provided by the simple variables to the synthetic indicator DP2, defined as

where n is the total number of variables —or partial indicators— DCi is Ivanovic's discriminant coefficient and (1- R i , i − 1 , i − 2 , . . . . . . , 1 2 ) is Pena's correction factor.

Finally, in accordance with Zarzosa (1996) , we define the “individual relative information coefficient” as:

This coefficient measures the relative weight of each simple variable included in the DP 2 synthetic indicator, considering both the useful information provided by each variable and its discrimination power. The values range from 0 to 1, allowing the identification of the variables that contribute most to explaining the differences between countries in the measurement of a pre-established objective ( Rodríguez, Jiménez, Salinas and Martín, 2016 ).

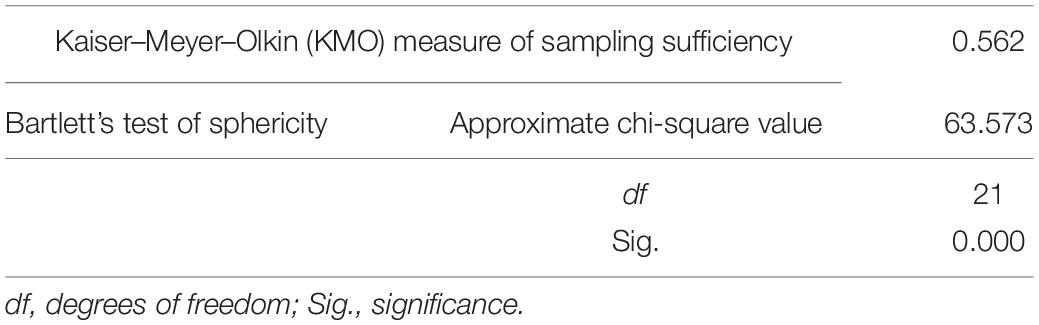

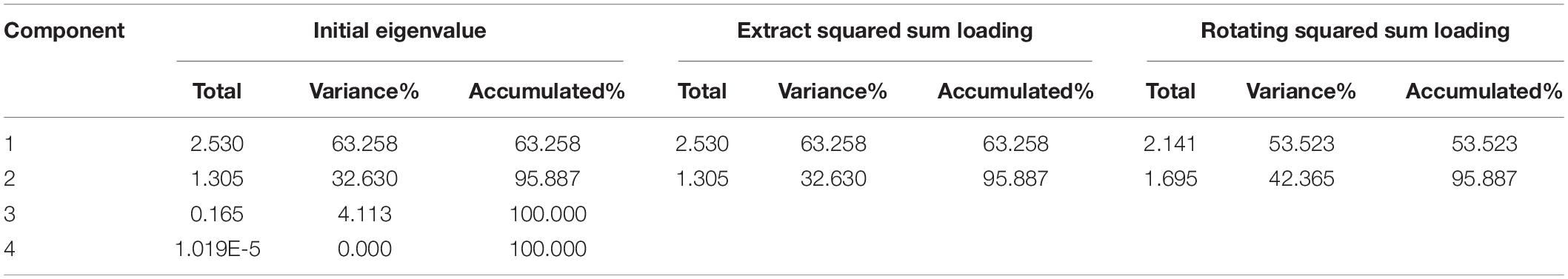

3.3. The process of construction of the TTCI according to the P 2 distance method

The synthetic indicator of tourism competitiveness proposed in this study follows a two-step construction process, as described in Salinas et al . (2020) . The goal is to integrate every useful piece of information provided by the 90 variables that make up the Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index, featured in the last report published by the World Economic Forum in 2019. The data have been downloaded from the website of this organization; whose link can be found in the bibliography ( World Economic Forum, 2019 ).

In a first stage, we have developed the partial synthetic indicators corresponding to each of the 14 pillars that make up the TTCI by taking into account all the simple variables and in accordance with the P 2 distance methodology. In a second stage, a synthetic global indicator of tourism competitiveness has been constructed, named Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index - DP 2 (TTCI-DP2), which integrates the 14 pillars previously calculated with the same methodology. Likewise, we calculated the coefficients of individual relative information for all the variables that comprise both the partial synthetic indicators of the 14 pillars and the global synthetic index of tourism competitiveness TTCI-DP 2 . This has allowed for the identification of the key variables of competitiveness, which will have to be emphasized so as to improve the competitive situation of tourist destinations.

4. Results and discussion

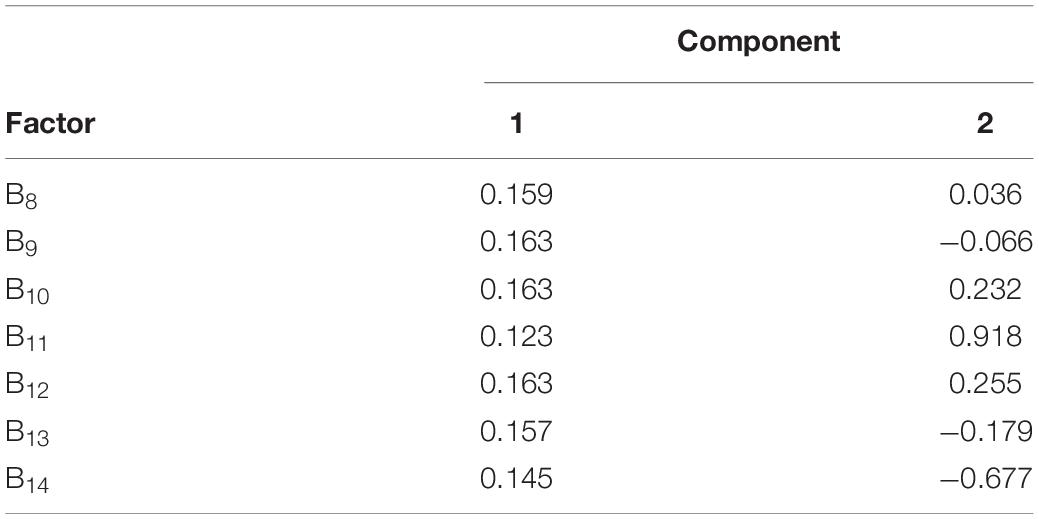

Following the methodology described above, a synthetic indicator of tourism competitiveness (TTCI-DP 2 ) has been calculated for a total of 80 countries, all of which hold top positions in the international ranking. Therefore, tourism and traveling have a relevant impact on their GDP. The advantages of the indicator created in comparison with WEF's TTCI reside in the greater precision in measuring the level of competitiveness of tourism destinations, as it only takes in the non-redundant information of the simple variables and avoids the arbitrary weighting of the same. Table 1 shows the pillars or dimensions of tourism competitiveness, which represent the variables forming part of the synthetic indicator. These variables follow an entry order that is determined by the values of the absolute correlation coefficients, ordered from highest to lowest. Likewise, Table 1 also shows the corrective factors, which reveal the new, non-redundant information provided by the variables when entering the synthetic indicator with respect to previous ones. As can be seen, pillar 5 "ICT readiness" enters first into the synthetic index with the highest correlation coefficient, which means that 100% of the information provided by this variable is incorporated into the TTCI-DP2. The rest of the variables contribute less information to the synthetic indicator, although in no case is their contribution less than 30%. The pillars that contribute more new information when entering the synthetic indicator are "P7. International openness" (72.24%) and "P2. Safety and security" (63.52%), while in last place is "P1. Business environment" (30.97%).

Structure of the Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index - DP 2

Source: own elaboration

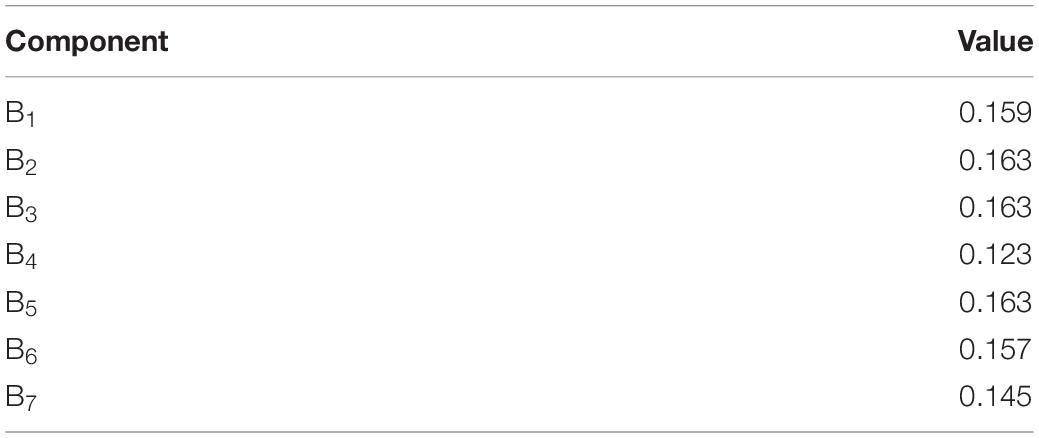

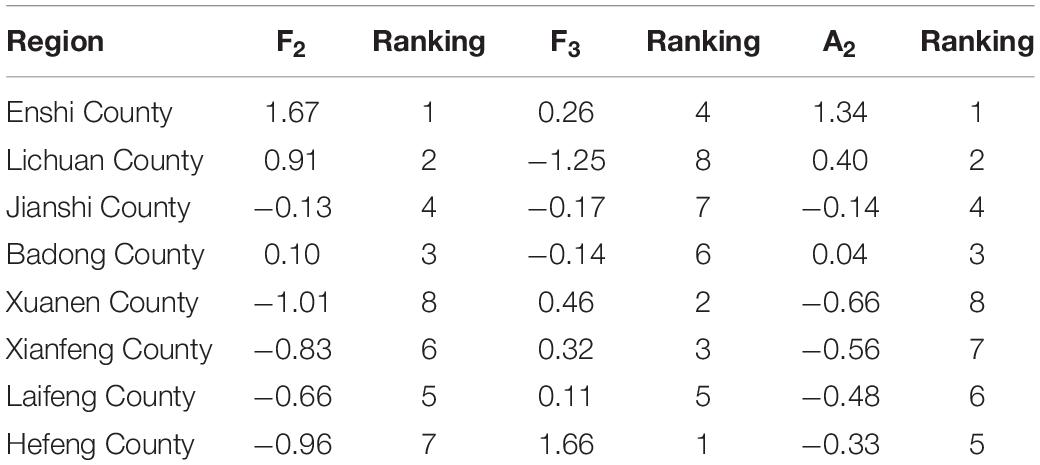

Once the structure of the TTCI-DP 2 indicator has been examined, the following step is to determine which are the pillars or dimensions that explain, to a greater extent, the differences in tourism competitiveness of the countries. For this purpose, the Individual Relative Information Coefficient (α), defined by Zarzosa (1996) , will be calculated. This coefficient combines the useful information provided by each variable —through corrective factors— to the synthetic indicator with their discrimination power, as calculated by Ivanovic's Discrimination Coefficient. Table 2 shows the values of the Individual Relative Information Coefficient for each of the 14 pillars of competitiveness analyzed. Such a coefficient determines the importance of each pillar in the TTCI-DP2. As can be seen, the first seven pillars contribute a total of 75.6% of individual relative information to the synthetic indicator, while the remaining seven only contribute 24.4%. Therefore, the differences in competitiveness of the countries whose tourism sector accounts for the largest share of GDP are explained, to a greater extent, by the first seven dimensions. Consequently, these dimensions are key factors in the design of policies, strategies and measures to improve the competitiveness of tourism destinations.

Coefficient of individual relative information contributed by each pillar to the TTCI-DP 2 .

Source: own elaboration.

The two most relevant pillars are related to the supply of cultural (pillar 14) and natural resources (pillar 13) available at the destination. Table 3 shows in detail which variables make the greatest individual relative contribution to each pillar. Regarding Pillar 14, it is important for tourist destinations to have "Oral and intangible cultural heritage" and a high number of "World Heritage cultural sites", while in Pillar 13, the presence of "World Heritage natural sites" and protected natural areas is fundamental.

Contribution of information by variable to the key pillars of competitiveness in the TTCI-DP 2 indicator.

The next pillars that best explain the variability of the synthetic indicator TTCI-DP 2 are related to the availability of information and communication technologies (ICT), to the international openness of the destination and to the supply of transportation infrastructure and tourist services. In Pillar 5 "ICT readiness", the variables "Individuals using Internet", "Active mobile broadband Internet subscriptions" and "Fixed broadband Internet subscriptions" are decisive, which together explain more than 70% of the differences between the countries analyzed. In "P7. International openness", the "number of regional trade agreements in force" is key, as this variable contributes almost 50% of the information related to the synthetic indicator of this pillar. The territorial differences in "P12. Tourist service infrastructure" are mainly explained by the variables "Presence of major car rental companies" and "Hotel rooms", which together contribute slightly over 60% of the total information of this pillar. Then, there are two pillars related to land and port (pillar 11) and air transportation infrastructures (pillar 10). The determining variables in Pillar 11 have to do with rail network density and the efficiency of land transportation. In Pillar 10 stand out those related to the capacity of airlines to transport passengers, both domestically and internationally, and to the number of aircraft departures. The information provided in Tables 2 and and3 3 allows for the identification of the pillars or dimensions that most influence the level of tourism competitiveness of destinations, as well as the particular variables to be addressed to help countries climb up the international rankings and become more competitive.

The analysis will now focus on identifying which countries are more vulnerable in the short and medium term, as they have suffered more intensely the effects of COVID-19 and have a more tourism-dependent economy. To this end, we took into account at the same time the virus incidence —in terms of cumulative number of cases per million inhabitants up to December 31 st , 2020— with the relevance of tourism in the economy of the country and with the degree of tourism competitiveness, as measured by the synthetic indicator TTCI-DP 2 . Countries whose economies are more tourism-dependent, have suffered a greater impact from COVID-19 and have a medium or low level of competitiveness will find it more difficult to return to their previous growth and employment rates in the coming years, which places them in a more vulnerable position.

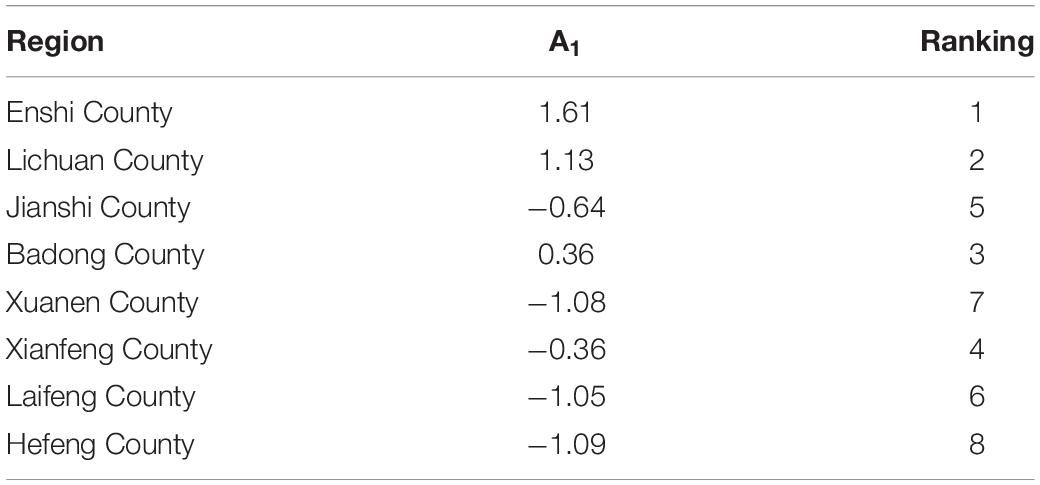

The impact of the pandemic on the countries analyzed has been measured by setting a threshold of 10,000 cases per million inhabitants; above this level, the incidence is considered high. As for tourism, it is considered that its contribution to the economy is medium-high when its weight exceeds 5% of GDP. Finally, in order to classify countries according to their level of tourism competitiveness, the average of the synthetic indicator TTCI-DP 2 has been taken as a reference value, namely 21.01 points, so that those countries above that figure will be the most competitive. Based on these criteria, Table 4 has been created. It shows 8 groups of countries according to their degree of vulnerability. Similarly, Table 5 in the Annex shows the complete ranking of the 80 countries selected, according to their level of tourism competitiveness and the vulnerability group in which they fall. These 80 countries account for 95% of the industry production out of a total of 140 countries included in the latest edition of the Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report, as well as hosting 91% of international tourist arrivals ( World Economic Forum, 2019 ). As shown in Table 4 , 13 countries with very high vulnerability and 31 countries with medium-high vulnerability have been identified. The rest of the countries are in a more favorable position with regard to the recovery of tourism activity, as their degree of vulnerability is relatively low.

Criteria for classifying countries according to their degree of vulnerability when facing the recovery of the tourism industry

Classification of countries in Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index - DP 2 and degree of vulnerability to recover tourism activity

Source: World Economic Forum – TTCI Report 2019 (T&T share of GDP). European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (COVID-19 cases). The authors.

Among the 13 most vulnerable countries are Mexico and Morocco, two of the tourist destinations that receive the most international travelers (around 40 and 11.5 million per year, respectively), and whose tourism sector accounts for more than 8% of their GDP. The tourism industry of three other countries has a significant presence in their economy, such as Cape Verde (18.39% of GDP) and Montenegro and Georgia, where tourism accounts for more than 10% of their GDP. Tunisia and the Dominican Republic, which receive 6-7 million international travelers every year, are also worth mentioning. The remaining six countries with the greatest vulnerability (Albania, Bahrain, Honduras, Jordan, Lebanon and Panama) receive less than 5 million international travelers per year, although the weight of tourism in their GDP ranges between 5 and 10%. In the medium-high vulnerable countries, there are some of the world's main tourist destinations in terms of the number of international arrivals and, although they occupy the top positions in the world ranking of competitiveness, their vulnerability is due to the fact that they have been strongly affected by the pandemic. Given that the tourism industry also has a significant weight in the GDP of these countries, they are expected to experience a slow recovery due to the mobility restrictions imposed to control the spread of the coronavirus. It is worth mentioning in this group the European Mediterranean countries (Spain, Italy, Greece, Portugal, Croatia and Malta), as well as Austria and the United Arab Emirates. Other relevant tourist destinations, which stand out in terms of number of international arrivals and exhibit medium-high vulnerability, are Egypt, the Russian Federation, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Turkey, Vietnam, Seychelles, Cambodia, Philippines, and Jamaica should also be mentioned for the considerable weight of their tourism sector in GDP.

In addition to identifying the countries that show the greatest vulnerability to recover economic activity derived from tourism in the short and medium term, it is essential to examine toward which pillars or dimensions of tourism competitiveness these countries should devote the greatest efforts in order to become more competitive at the international level. Undoubtedly, only those destinations that reinforce their competitiveness will be able to face the difficult recovery of the tourism industry in the coming years. Figure 1 shows the degree of competitiveness of the most vulnerable countries for each of the 14 pillars included in the ITPGR-DP 2 .

Degree of competitiveness, by pillar, of the most vulnerable countries (Percentage reached with respect to the maximum value recorded for each pillar).

For each pillar, the average value of the most vulnerable countries has been calculated, divided by the maximum value recorded in each pillar and expressed as a percentage. As the data reveal, the most vulnerable countries perform worse in the key pillars of competitiveness, as shown in Table 2 , most of them scoring below 60%. The greatest distance from the maximum value is found in the pillars "P14. Cultural resources and business travel" (15.1%); "P10. Air transport infrastructure" (29.3%), and "P13. Natural resources" (40.6%). Therefore, these countries should focus on developing policies aimed at improving the worst aspects of the pillars that have the greatest impact on the competitiveness of tourism destinations. To do so, countries should prioritize improving the indicators shown in Table 3 , since they are the ones that explain the greatest territorial differences in each pillar.

5. Conclusions

As a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, the tourism industry has been significantly affected. This crisis situation is expected to continue in the medium and long term, so those countries where tourism is one of the main sources of income will take longer to recover. The impact on economies will depend partially on the competitiveness of each country's tourism sector. The most competitive destinations will be in a better position to face the recovery process and will even be more robust in withstanding the crisis. This situation can generate an opportunity, as long as tourist destinations opt for improving their competitiveness and move towards a transformation that will make them stronger. Thus, identifying the most vulnerable countries and the variables that explain their vulnerability is a very interesting contribution to support crisis response policies. This study focuses on such an objective. Basically, it seeks to identify the most vulnerable countries as regards their tourism industry in the context of a pandemic. This pioneering contribution to the academic literature will make it possible to understand the character of these countries' vulnerability and thus facilitate the development of public policies to promote tourism. Therefore, this research, in addition to being innovative, is of great social utility.

The proposed study has grouped countries according to their vulnerability. Said vulnerability is determined by combining several characteristics: low competitiveness, a high incidence of COVID19 and a high weight of tourism in its economy. As a result, we have identified the 13 most vulnerable countries, namely: Panama, Georgia, Bahrain, Morocco, Montenegro, Albania, Mexico, Dominican Republic, Jordan, Tunisia, Cape Verde, Honduras, and Lebanon. This answers RQ1: Which countries are the most vulnerable in the context of the crisis in the tourism sector? It should be borne in mind that maximum vulnerability is reached when the country is highly dependent on tourism activity, has poor levels of competitiveness and a high incidence of the pandemic. The countries mentioned above comply with these criteria, so that the most effective action in the short term would be to control the incidence of the pandemic and improve tourism competitiveness, since diversification policies would take longer to be effective.

These countries show a very negative situation in the pillars or dimensions that have been identified as key to tourism competitiveness, most of them being below 60% with respect to the value achieved by the best positioned country. The pillars with the greatest distance in relation to the maximum value are "P14. Cultural resources and business travel" (15.1%); "P10. Air transport infrastructure" (29.3%), and "P13. Natural resources" (40.6%). Thus, the most vulnerable countries should define policies to improve their situation in these competitive factors, since, in addition to having been identified as key elements, they are the weakest in these areas. Specifically, the determining elements of competitiveness on which it is possible to work more effectively in the short/medium term would be those related to the enhancement of cultural elements and historical-artistic heritage; the protection of natural areas; the availability and improvement of information and communication technologies; the international opening of the destination, which, in turn, would promote regional trade agreements; and the increase in the supply of transport infrastructure, especially rail and air transport, as well as tourist services. This would answer RQ2: In which dimensions of competitiveness should they work to improve this situation? The above outlines three strategic elements for improving competitiveness. The first focuses on the management and protection of tourism resources, both cultural and natural. The second involves improving transportation and telecommunications infrastructures. And third, improving the country's external openness. The most vulnerable countries should design strategies focused on these lines, or at least on those on which they can work more effectively in the short term.

This research contributes, in the first place, to identifying the countries with the worst departing point in the process of recovery after the peak of the pandemic. Secondly, it sets out a roadmap of factors on which the countries should focus in order to improve the competitiveness of tourist destinations. It would be interesting to continue this research by carrying out a follow-up study during the recovery period, the recovery period, related to the evolution of arrivals to each of the destinations defined as vulnerable. It would also be very interesting and useful to compare the nature of the policies adopted by the countries to support their tourism sector with the factors on which intervention has been recommended.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Biographies.

Jose Antonio Salinas Fernández is a senior lecturer at the University of Granada, Spain, Department of Spanish and International Economics. The interests of his research focus on tourism management, economic impact, social and economic indicators. He holds a Ph.D. in Economics and Business and a MA in Economy of the European Union. He has worked as an economic analyst and consulting projects director for various companies and financial institutions.

José Manuel Guaita Martinez has been the Director of the master's degree in Business Administration at the Valencian International University since 2014 until 2020. He received a PhD in Economics after completing a degree in Business Administration and Contemporary History. He has also been the head of the international financial markets department at several banking institutions. He conducts basic research into financial markets, sport, entrepreneurship, innovation, sustainability, and tourism economics. He has guest edited special issues in Journal of Business Research and Technological Forecasting and Social Change. He belongs to the editorial review board of top journals such as Journal of Business Research, Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, and International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research. He is currently a senior lecturer at Universitat Politècnica de València

Jose María Martín Martín is a senior lecturer at University of Granada, Spain, Department of Spanish and International Economics. The interests of his research focus on tourism economics, economic and social sustainability, seasonality and sustainable development. He holds a Ph.D. in Economics and Business and a MA in International Business. He has worked as an economic analyst and consulting projects director for various companies and financial institutions. He has collaborated with the Spanish government in the development of public policies in the tourism sector. He has also led the Business Area for the International University of La Rioja.

- Abreu-Novais M., Ruhanen L., Arcodia C. Destination competitiveness: A phenomenographic study. Tourism Management. 2018; 64 :324–334. [ Google Scholar ]

- Allen T., Murray K.A., Zambrana-Torrelio C., Morse S.S., Rondinini C., Di Marco M., Breit N., Olival K.J., Daszak P. Global hotspots and correlates of emerging zoonotic diseases. Nature Communications. 2017; 8 (1) doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00923-8. Available atAccessed on 1 st December 2020. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barbosa L.G.M., Oliveira C.T.F.D., Rezende C. Competitiveness of tourist destinations: the study of 65 key destinations for the development of regional tourism. Revista de Administração Pública. 2010; 44 (5):1067–1095. [ Google Scholar ]

- Buhalis D. Marketing the competitive destination in the future. Tourism Management. 2000; 21 (1):97–116. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carracedo P., Puertas R., Marti L. Research lines on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on business. A text mining analysis. Journal of Business Research. 2021; 132 :586–593. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chang C.L.L., McAleer M., Ramos V. A Charter for Sustainable Tourism after COVID-19. Sustainability. 2020; 12 (9):3671. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen M.H., Jang S.C., Kim W.G. The impact of the SARS outbreak on Taiwanese hotel stock performance: An event-study approach. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2007; 26 (1):200–212. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Croes R., Kubickova M. From potential to ability to Compete: Towards a performance-based tourism competitiveness index. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management. 2013; 2 (3):146–154. [ Google Scholar ]

- Crouch G.I. Destination Competitiveness: An Analysis of Determinant Attributes. Journal of Travel Research. 2011; 50 (1):27–45. [ Google Scholar ]

- Crouch G.I., Ritchie J.B. Tourism, Competitiveness, and Societal Prosperity. Journal of Business Research. 1999; 44 :137–152. [ Google Scholar ]

- Crouch G.I., Ritchie J.B. Application of the Analytic Hierarchy Process to Tourism Choice and Decision Making: A Review and Illustration Applied to Destination Competitiveness. Tourism Analysis. 2005; 10 (1):17–25. [ Google Scholar ]

- De Castro M., Pérez-Rodríguez F., Martín J.M., Azevedo J.C. Modelling stakeholders’ preferences to pinpoint conflicts in the planning of transboundary protected areas. Land Use Policy. 2019; 89 [ Google Scholar ]

- De Castro M., Fernández P., Guaita J.M., Martín J.M. Modelling Natural Capital: A Proposal for a Mixed Multi-criteria Approach to Assign Management Priorities to Ecosystem Services. Contemporary Economics. 2020; 14 (1):22–37. [ Google Scholar ]

- Donthum N., Gustafsson A. Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. Journal of Business Research. 2020; 117 :284–289. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dupeyras A., MacCallum N. OECD Publishing; Paris: 2013. Indicators for Measuring Competitiveness in Tourism: A Guidance Document. OECD Tourism Papers, 2013/02. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- European Data Portal, 2020. The Impact of COVID-19 on the International Tourism Industry. Available at: https://www.europeandataportal.eu/en/impact-studies/covid-19/impact-covid-19-international-tourism-industry Accessed on 1st December 2020.

- Gómez-Vega M., Picazo-Tadeo A. Ranking world tourist destinations with a composite indicator of competitiveness: To weigh or not to weigh? Tourism Management. 2019; 72 :281–291. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gooroochurn N., Sugiyarto G. Competitiveness indicators in the travel and tourism industry. Tourism Economics. 2005; 11 (1):25–43. [ Google Scholar ]

- Guaita J.M., de Castro M., Pérez-Rodríguez F., Martín J.M. Innovation and Multi-Level Knowledge Transfer Using a MultiCriteria Decision Making Method for the Planning of Protected Areas. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge. 2019; 4 (4):256–261. [ Google Scholar ]

- Guaita J.M., Martín J.M., Salinas J.A. Analyzing the Relationship Between Innovation, Value Creation, and Entrepreneurship (Galindo-Martín. IGI Global; 2020. Innovation in the Measurement of Tourism Competitiveness; pp. 268–288. M.A., Mendez-Picazo, M.T., Castaño-Martínez, M.S. Eds. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dwyer L., Kim C. Destination Competitiveness. Determinants and Indicators. Current Issues in Tourism. 2003; 6 (5):369–414. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hall C.M. In: Handbook of globalisation and tourism. Timothy D., editor. Edward Elgar; 2020. Biological invasion, biosecurity, tourism, and globalisation; pp. 114–125. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hall C.M., Scott D., Gössling S. Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tourism Geographies. 2020; 22 (3):577–598. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hassan S. Determinants of market competitiveness in an environmentally sustainable tourism industry. Journal of Travel Research. 2000; 38 (3):239–245. [ Google Scholar ]

- Heath E. Towards a model to enhance destination competitiveness: A southern african perspective. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research. 2003; 10 (2):124–141. [ Google Scholar ]

- Henderson J.C., Ng A. Responding to crisis: severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and hotels in Singapore. International Journal of Tourism Research. 2004; 6 (6):411–419. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ivanovic B. Comment établir une liste des indicateurs de dévelopement. Revue de Statistique Appliquée. 1974; 22 (2):37–50. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jiménez J.D., Martín J.M., Montero R. Felicidad, desempleo y crisis económica en Andalucía. Algunas evidencias. Revista de Estudios Regionales. 2014; 99 :183–207. [ Google Scholar ]

- Joshi O., Poudyal Larson, L.C. The influence of sociopolitical, natural, and cultural factors on international tourism growth: A cross-country panel analysis. Environment, Development and Sustainability. 2017; 19 (3):825–838. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kantar, 2020. Global study of 25,000 consumers gives brands clearest direction on how to stay connected in a pandemic world. Press Release. http://www.millwardbrown.com/global-navigation/news/press-releases/full- release/2020/03/25/global-study-of-25000-consumers-gives-brands-clearest-direction-on-how-to-stay-connected- in-a-pandemic-world.

- Kozak M., Rimmington M. Measuring tourist destination competitiveness: conceptual considerations and empirical findings. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 1999; 18 (3):273–283. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lew, A., 2020. How to Create a Better Post-COVID-19 World. Available at: https://medium.com/@alanalew/creating-a-better-post-covid-19-world-36b2b3e8a7ae Accessed on 1st December 2020.

- Lozano-Oyola M., Blancas F.J., González M., Caballero R. Sustainable tourism indicators as planning tools in cultural destinations. Ecological Indicators. 2012; 18 :659–675. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mair, S., 2020. What will the world be like after coronavirus? Four possiblefutures. The Conversation. Available at: https://theconversation.com/what-will-the-world-be-like-after...d=IwAR2wr9pzssSdBSxjaHaWba9iHSF3flYgZBVI1jAx_Y4YlXVAImcJcNdjM Accessed on 30th March 2020.

- Martín J.M., Guaita J.M. Entrepreneurs’ attitudes toward seasonality in the tourism sector. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research. 2019; 26 (3):432–448. doi: 10.1108/IJEBR-06-2019-0393. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Martín J.M., Guaita J.M., Burgos-Mascarrell A. Promotion and Economic Impact of Foreign Tourism. Journal of Promotion Management. 2019; 25 (5):722–737. [ Google Scholar ]

- Martín J.M., Salinas J.A., Rodríguez J.A. Comprehensive evaluation of the tourism seasonality using a synthetic DP2 indicator. Tourism Geographies. 2019; 21 (2):284–305. [ Google Scholar ]

- Martín J.M., Guaita J.M., Molina V., Sartal A. An Analysis of the Tourist Mobility in the Island of Lanzarote: Car Rental Versus More Sustainable Transportation Alternatives. Sustainability. 2019; 11 (3):739. doi: 10.3390/su11030739. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Martín J.M., Salinas J.A., Rodríguez J.A., Jiménez JdD. Assessment of the tourism's potential as a sustainable development instrument in terms of annual stability: Application to Spanish rural destinations in process of consolidation. Sustainability. 2017; 9 :1692. [ Google Scholar ]

- Martín J.M., Salinas J.A., Rodríguez J.A., Ostos M.S. Analysis of Tourism Seasonality as a Factor Limiting the Sustainable Development of Rural Areas. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research. 2020; 44 (1):45–75. [ Google Scholar ]

- McKinsey & Company. (2020). Beyond coronavirus: The path to the next normal. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/_/media/McKinsey/Industries/Healthcare%20Systems%20and %20Services/Our%20Insights/Beyond%20coronavirus%20The%20path%20to %20the%20next%20normal/Beyondcoronavirus-The-path-to-the-next-normal.ashx. Accessed on 1st December 2020.

- Mazanec J.A., Ring A. Tourism destination competitiveness: Second thoughts on the world economic forum reports. Tourism Economics. 2011; 17 (4):725–751. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mazanec J.A., Wöber K., Zins A.H. Tourism Destination Competitiveness: From Definition to Explanation? Journal of Travel Research. 2007; 46 :86–95. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mendola D., Volo S. Building composite indicators in tourism studies: Measurements and applications in tourism destination competitiveness. Tourism Management. 2017; 59 :541–553. [ Google Scholar ]

- Menegaki, A.N., 2020. Hedging Feasibility Perspectives against the COVID-19 for the International Tourism Sector. Available at: https://doi.org/10.20944/PREPRINTS202004.0536.V1.

- Novelli M., Gussing L., Jones A., Ritchie B.W. ‘No Ebola...still doomed’ – The Ebola-induced tourism crisis. Annals of Tourism Research. 2018; 70 :76–87. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ötsch, W., 2020. What type of crisis is this? The coronavirus crisis is a crisis of the economized society. Lecture at the topical lecture series of Cusanus Hochchule für Gesellschaftsgstaltung, 9 April 2020.

- Pena J.B. INE; Madrid: 1977. Problemas de la medición del bienestar y conceptos afines (una aplicación del caso español) [ Google Scholar ]

- Pena J.B. La medición del bienestar social: una revisión crítica. Estudios de Economía Aplicada. 2009; 27 (2):299–324. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pérez V., Blancas F.J., González M., Guerrero F.M., Lozano M., Pérez F., Caballero R. Evaluación de la sostenibilidad del turismo rural mediante indicadores sintéticos. Investigación Operacional. 2009; 30 (1):40–51. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ribeiro-Navarrete S., Palacios-Marqués D., Martín J.M., Guaita J.M. A synthetic indicator of market leaders in the crowdlending sector. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research. 2021 doi: 10.1108/IJEBR-05-2021-0348. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ritchie J.B., Crouch G. A model of destination competitiveness/sustainability: Brazilian perspectives. Revista de Administración Pública. 2010; 44 (5):1049–1066. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodríguez J.A., Jiménez J.D., Salinas J.A., Martín J.M. Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5: Progress in the Least Developed Countries of Asia. Social Indicators Research. 2016; 129 :489–504. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodríguez J.A., Martín J.M., Jiménez J.D. A Synthetic Indicator of Progress Towards the Millennium Development Goals 2, 3 and 4 in the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) of Asia. Applied Research in Quality of Life. 2018; 13 :1–19. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodríguez J.A., Martín J.M., Salinas J.A. Assessing MDG 6 In Sub-Saharan Africa: a Territorial Analysis Using a Synthetic Indicator. Revista de Economía Mundial. 2019; 53 :203–221. [ Google Scholar ]

- Salinas J.A., Serdeira P., Martín J.M., Rodríguez J.A. Determinants of tourism destination competitiveness in the countries most visited by international tourists: Proposal of a synthetic index. Tourism Management Perspectives. 2020; 33 [ Google Scholar ]

- Seong B.H., Hong C.Y. Does Risk Awareness of COVID-19 Affect Visits to National Parks? Analyzing the Tourist Decision-Making Process Using the Theory of Planned Behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18 :5081. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sigala M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. Journal of Business Research. 2020; 117 :312–321. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Somarriba N. Universidad de Valladolid; 2008. Aproximación a la medición de la calidad de vida social e individual en la Europa Comunitaria (Tesis doctoral) [ Google Scholar ]

- Somarriba N., Pena B. Synthetic indicators of quality of life in Europe. Social Indicators Research. 2009; 96 :115–133. [ Google Scholar ]

- Somarriba N., Zarzosa P., Pena B. The economic crisis and its effects on the quality of life in the European Union. Social Indicators Research. 2015; 120 :323–343. [ Google Scholar ]

- Somarriba N., Zarzosa P. Vol. 62. Social Indicators Research Series; 2016. Quality of Life in Latin America. A Proposal for a Synthetic Indicator. (Indicators of Quality of Life in Latin America). 10.1007/978-3-319-28842-0_2. [ Google Scholar ]

- Strielkowski, W., 2020. International Tourism and COVID-19: Recovery Strategies for Tourism Organisations. https://doi.org/10.20944/PREPRINTS202003.0445.V1.

- UNWTO . Vol. 18. UNWTO; Madrid, Spain: 2020. (UNWTO World Tourism Barometer). 2. [ Google Scholar ]

- World Economic Forum . World Economic Forum; Geneva: 2017. The travel & tourism competitiveness report 2017: Paving the way for a more sustainable and inclusive future. [ Google Scholar ]

- World Economic Forum, 2019. The travel & tourism competitiveness report 2019. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/reports?year=2019#filter Accessed on 1st December 2020.

- WTTC, 2020. Travel & Tourism's direct, indirect and induced impact. Available at: https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact . Accessed on 1st December 2020.

- Zarzosa P. Secretariado de Publicaciones; Valladolid: 1996. Aproximación a la medición del Bienestar Social. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zarzosa P. Diputación Provincial; Valladolid: 2005. La calidad de vida en los municipios de la provincia de Valladolid. [ Google Scholar ]

Competitive Advantage in Tourism

- Living reference work entry

- Latest version View entry history

- First Online: 22 April 2023

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Basak Denizci Guillet 3

14 Accesses

Competitive advantage has a long history of application in industrial studies relating to competition and competitiveness at the company or firm level. Its introduction to tourism and destination management started after the publication of The Competitive Advantage of Nations (Porter 1990 ). At the industry level, competitive advantage is used to describe a firm’s ability to create more economic value (the difference between the perceived benefits by a customer who purchases a firm’s products or services and their full economic cost) than its rival firms (Barney 2007 :17).

At the global level, competitive advantage depends on the country’s ability to innovatively achieve, or maintain, an advantageous position in its key industries over others. In relation to tourism management, competitive advantage deals with the ability to use a destination’s resources efficiently and effectively over the long term (Crouch and Ritchie 1999 ). A number of researchers have provided inputs into the...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Barney, J. 2007. Gaining and Sustaining Competitive Advantage . Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Google Scholar

Cronjé, D., and E. du Plessis. 2020. A Review on Tourism Destination Competitiveness. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 45: 256–265.

Article Google Scholar

Crouch, G., and J. Ritchie. 1999. Tourism, Competitiveness, and Societal Prosperity. Journal of Business Research 44: 137–152.

Porter, M. 1990. The Competitive Advantage of Nations . New York: Macmillan.

Book Google Scholar

Tsai, H., H. Song, and K. Wong. 2009. Tourism and Hotel Competitiveness Research. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 26: 522–546.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, SAR, China

Basak Denizci Guillet

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Basak Denizci Guillet .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Hospitality Leadership, University of Wisconsin-Stout, Menomonie, WI, USA

Jafar Jafari

School of Hotel and Tourism Management, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Honggen Xiao

Section Editor information

Makerere University Business School, Kampala, Uganda

Peter U. C. Dieke

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Guillet, B.D. (2023). Competitive Advantage in Tourism. In: Jafari, J., Xiao, H. (eds) Encyclopedia of Tourism. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01669-6_33-2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01669-6_33-2

Received : 21 October 2021

Accepted : 22 October 2022

Published : 22 April 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-01669-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-01669-6

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Business and Management Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

Chapter history

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01669-6_33-2

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01669-6_33-1

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Reimagining the $9 trillion tourism economy—what will it take?