- Request new password

- Create a new account

The Business of Tourism

Student resources, chapter 1: an introduction to tourism, question 1: why is it difficult to define tourism.

Answer Guide: Definitions are difficult because they need to encompass the many different types of tourists. For example, we can separate by domestic and international travel, reasons for travelling (e.g. business or leisure) and the length of time travelled (day trips or over-night). We also need to exclude those that travel but are not considered tourists (migrants, nomads, etc.) and those that use tourist facilities but are not tourists (e.g. academics visiting a historic attraction for research purposes).

Question 2: In this chapter, we note that tourism is influenced by characteristics such as intangibility, inseparability, heterogeneity and perishability. What are the implications of each of these characteristics for tourism managers?

Answer Guide: These characteristics mean that operations must be adapted accordingly:

Intangibility – this means that the product cannot be touched or tested before use. Consequently the way the product is marketed but be to give the buyer a good sense of what the product will be like. This might be through the use of videos that show the guest around or the use of famtrips for those selling holidays so they can better explain the experience to the tourist.

Inseparability – this means that the tourist and the service provider must come together for the service to take place. This interaction means that quality and consistency have to be ensured to maximise customer satisfaction. To achieve this extensive staff training may be required. It also needs to consider that multiple customers are using the product at the same time and can influence each other’s experience (i.e. a noisy group in a restaurant could affect the experience of a couple wanting to have a quiet meal together).

Heterogeneity – this means that the product is not always the same. For example, inclement weather, flight delays or the bad mood of service staff can make one person’s holiday experience very different from those travelling at a different time.

Perishability – this means that the product is time-limited. For example, once a plane departs, any seats on the flight that are not sold cannot be stored for sale at a later date. The same is true for a hotel bedroom. Tourism managers address this issue through yield management, pricing products to encourage early purchase as well as selling off remaining products last minute, if needed.

Question 3: How does the perception of available amenities and attractions influence a tourist’s choice of destination?

Answer Guide: Iconic attractions can be sufficient to attract visitors to select a particular destination. Other attractions may add to the appeal and encourage a longer stay. The availability of amenities (accommodation. restaurants, bars and shops, etc.) can make visits easier and more appealing, again extending the length of time a visitor stays at a destination.

Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > Tourism - Perspectives and Practices

Expectancy Models and Work Related Service Innovation and Service Quality Orientation as a Business Strategic Tool in the Tourism Sector

Submitted: 16 July 2018 Reviewed: 07 November 2018 Published: 06 November 2019

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.82442

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Edited Volume

Tourism - Perspectives and Practices

Edited by Şenay Sabah

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

1,333 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

Service innovation and service quality have become important aspects as business strategic tools and for leveraging economies of scale in emerging countries in the Southern African Development Community (SADC). They have become pivotal drivers of the global economic increase in the hospitality and tourism service sector and in shaping the industries towards successful business strategic tools. In the SADC countries, such as South Africa, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Namibia and Lesotho, service innovation and business performances in the tourism/hospitality sector contribute immensely to the economies and make a significant contribution to the increase in gross domestic product (GDP) of the countries. Additionally these concepts also provide the necessary integration of the service sector, economic theories of the industry as well as quality service innovations that adhere to quality standards in the tourism and hospitality sector. The tourism/hospitality sector forms the basis for tourist satisfaction which is a key driver in profit making, financial performances, tourist retention and tourism destination reputation regionally, and internationally.

- service innovation

- service quality

- strategic tool

- orientation

- business performances

- tourism sector

- hospitality sector

Author Information

Abigail chivandi *.

- University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

Michael Olorunjuwon Samuel

Mammo muchie.

- Tshwane University of Technology, South Africa

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected]

1. Introduction

In today’s world, the service industry has become an important player in the economies of countries in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) [ 1 ]. The service industry has become a critical driver of growth in the tourism/hospitality service business [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. The study gives an insight for determining the influence of service innovation orientation on alignment with business performances and strategic tools in the tourism/hotel sector. Provision is made for channelling and providing an in-depth knowledge in the service innovation orientation that would enhance the tourism/hospitality industry in addressing downturn specific opportunities that enable companies to flourish in downturns/turnaround strategies frequently and by also leveraging crises to reinvent themselves, proactively exploring new avenues for growth and new innovative ideas. The tourism and hospitality industry falls under the service industry and has been reviewed as a critical driver of growth in the SADC region [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. The sector, through the medium of the tourism and hospitality sector provides services, including among others, food and beverage, tourism attractions, events tourism, sports tourism, medicinal tourism innovations, entertainment and accommodation to both local and international tourists. While it is critical to ensure quality service delivery in all services provided by the tourism/hospitality sector, tourists to the holiday resorts need to be assured and have the right to expect the services they are provided with to be of high quality and increase business performance and also contribute to the enhancement of GDP [ 6 ]. Globally, tourism and hospitality service industries consistently and constantly review their operations in order to create service innovation, provide quality service and value creation by using models such as the Service business model and Business model Innovation [ 7 ]. While at regional level, SADC member states that are affiliated, based in the tourism and hospitality sector, pursue service business innovation and business model innovation, the literature provided in the manufacturing sector cannot help us understand the service business innovation orientation, strategic management and service quality processes in the tourism and hospitality service industry because of the tourism/hospitality service characteristics that are unique and complex. There is a lack of systematic research on the topic of the SBIO [ 8 ] at regional level within the tourism industry yet the tourism/hospitality business service contributes significantly to global economic growth [ 7 ]. The creation of value, redefining the products can be easily done and has been done using the service innovation and strategies in emerged and emerging countries by the manufacturing industry [ 9 ]. In the service industry, the service is characterised by services that are intangible and invisible; this is also evident in the separation of consumption of tourism/hospitality services vis a vis to its premises. The nature of the tourism/hospitality service offering is composed of high fixed cost, intangibility, perishability, heterogeneity, inseparability, simultaneous production, and high consumer involvement in co-production [ 10 ]. There is intense competition at international level under which tourism services and processes are conveyed and technological shifts that demand new competitive approaches. There is a dearth of information and knowledge on the innovation orientation, service quality, business establishment of service innovation in the tourism/hospitality services in SADC region.

In the SADC countries, service business innovation in the tourism/hospitality sector is crucial to the economy [ 2 ]. Service business innovation makes the strongest contribution to the rise and integration of the service sector through economic theories of the industry. Lovelock and Gummesson [ 11 ] argue that the characteristics of services are unique and require new managerial approaches. The importance of service today contributes the highest share of the gross domestic product (GDP) in emerging economies [ 8 ]. Due to the fast potential growth in tourism/hospitality, companies have to make a paradigm shift on their service offering from just “mere” service offering to innovation orientation whilst producing quality services [ 12 ]. Unlike in the manufacturing industries where the focus is on producing tangible products with little or no emphasis on innovation, trends have shown that there is a dire need for tourism/hospitality service providers to shift focus from producing services that are merely marketing oriented to services that are innovation (recreating and redesigning) oriented [ 12 ].

At both the regional and international level, service innovation in the tourism/hospitality industry sector has become the key driver in profit making, financial performances, customer retention, hotel reputation and the basis for customer satisfaction [ 8 , 12 ]. However, the global services are not only composed of the competitive market, but by the rapid change in destination marketing strategies [ 13 , 14 ]. Thus, amid global competition, service marketing organisations are looking at innovative ways to put their market in the best business strategic position in the tourism/hospitality sector [ 12 ]. Shifting tourism segments and the response to changes in preferences has led the tourism/hospitality sector to refocus on the changes in innovation in which the business operates as well as the socio-political and economic environment. There is a need for service business players in the tourism/hospitality sector to appreciate innovation, not only in the service commodities and its processes, but to realise the new changes in service and business performances as key drivers to achieving competitive advantage, market share and business opportunities arising from service innovation orientation [ 15 ]. Service business innovation (SBI) has many dimensions and many stages, inclusive of changes in business preferences and market/business strategies that improve the current business system and at the same time recreate new ways of doing business [ 16 ] ( Figure 1 ).

Map of the SADC member states that contribute to the tourism/hospitality industry regionally (source: sadcreview.com ).

Product and service innovation

Process innovation

Logistics innovation

Market innovation or institutional innovation

The study by Chivandi [ 6 ] interrogated the existing theoretical and empirical business innovation orientation literature and developed a sound theoretical framework for examining the influence of innovation orientation on service impact and business performance in the hotel sector, specifically to the unique and complex features of the tourism/hospitality service products. “The research constructs such as the learning philosophy, transfunctional acclimation, strategic direction, service innovation and customer retention, hotel reputation and financial performances were deemed the main players in the study”. The study focused and conducted its empirical and theoretical investigation into the tourism/hospitality industry in one of the SADC member states, as an emerging country in the SADC region, with the aim of providing an appealing context in exploring the study’s research problem and at filling the research gap in the service sector.

“It has been noted that for the period 2008–2009, globally the Tourism/Hospitality industry’s contribution to the global economy was negatively affected by the global credit crisis” [ 6 , 20 ]. The crisis resulted in a marked decrease in disposal incomes, consequently causing potential consumers of the industry’s services to cut on travelling and this impacted heavily towards tourism destinations in SADC member states. “According to the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC, 2010), the negative developmental trend was reversed by 2010 as witnessed by the industry’s estimated GDP of US$2 billion, a 0.7% increase compared to the preceding period”. “At the onset of the recovery, the tourism/hospitality industry’s revenue grew by 0.5% to US$5.8 billion [ 6 , 12 ].” From 2010, it has been projected that the recovery of the industry will be sustained on the backdrop of improved disposable incomes by both corporations and households, resulting in increased demand of the tourism/hospitality services [ 8 ]. Coupled to the increased service demand is the positive service innovation by the industry that is envisaged to have a pull factor on consumers of the tourism/hospitality services [ 8 ]. “The contribution of the global industry to employment creation is seen to be having an upward trend, with global trends forecasting an increase from 8 to 18.6 million jobs for the industry” [ 6 ].

The WTTC forecasts that the hospitality/hotel industry’s growth will lead it to be a global priority sector and that will contribute to employment creation [ 21 ]. “It is estimated that by 2020 industry’s contribution to GDP will amount to US$3.7 billion which represents a 4% increase in terms of annualised growth rate but with an overall Tourism/Hospitality GDP expected to be at US$104.7 billion by 2020” [ 21 ]. While recovery of the tourism/hospitality services sector commenced in 2010 post the global credit crisis, it has been forecast that the rate of recovery would be faster in the emerging countries in the SADC member states when compared to emerged countries [ 21 ], thus emerging countries, the Southern African region included, are forecast to become the major tourist destinations. “Despite the assertion that growth of the Tourism/Hospitality services in developed countries post 2009 is slower to that in emerging countries, the Imara report further contends that the increased focus by the developed countries on Tourism/Hospitality, service innovation will stimulate increased consumption of the industry’s services” [ 20 ]. Furthermore, the study is expected to improve the tourism/hospitality service offering as a whole using the best innovative strategic tools that are available during the times of economic hardship as well as competing and meeting standards at a global level. Finally, this study serves as a baseline for future innovation in the hospitality sector and knowledge in service innovation and business performances in emerging countries (SADC). Deducing from the above information, the study is grounded on the following research constructs and theories.

2. Literature review and theoretical grounding of the constructs

Tourism/hospitality theories can be stated as the following: social exchange theory, an expectancy theory of motivation, the Otus theory of demand and supply, rational exchange theory, practical theory of motivation, management theory, service marketing theory, and theory of innovation, learning theory and Marlow’s hierarchy of hotel expectations.

2.1 Service innovation orientation in tourism/hospitality

“Innovation orientation is viewed as a strategic orientation that influences organisational innovation in the hospitality/hotel sector and it has a diversity knowledge structure.” Hurley and Hult [ 22 ] describe innovation as the firm’s willingness to learn new ideas and capacity to change managerial systems. Innovation in the service concept is driven by the 6Vs: value service creation, value service manoeuvring, value service capture, value service quality, value service delivery and economic value [ 11 ]. Innovation in service provides an understanding of strategy execution, revenue and profit sources, and financial implications in the service industry [ 11 ]. “Innovation implies the new creation in service business that results in the improvement of commodities in favour of the customer and impacting positively on business performances”.

“Service innovation describes a unique way of presenting services in an ordinary manner, or the unique or better combination of the service production elements so as to attract customers and grow business in terms of profits and other benefits such as the customer value and customer attraction” [ 18 ]. “Tourism/Hospitality services are characterised by intangibility, inseparability, heterogeneity and perishability” [ 13 ]. “Service also involves processes and resources to benefit the customer and entails a co-creation model of value creation that represents an interaction between providers and customer”. The intangibility aspect of the service is that it cannot be physically touched, but can be felt and experienced. For instance, in a “hotel, a customer can experience a meal”. So there is a dire need for the service offering to have a different strategic tool and the business model innovation must be able to address the service characteristic using re-creation delivery and capturing according to Gordon [ 23 ]. “According to Gummerson (2007), perishability in service innovation means that services cannot be stored for later use, resold or returned.” “When customers are few, time can be spent on the maintenance of facilities and systems administration” as suggested by Bettencourt [ 24 ]. “Brinkley [ 25 ] contends that recreation, prepositioning and redeveloping and reading up of new developments relate to business model innovation processes and thus reinvention processes in relation to fixed cost.” Namasivayam et al. [ 26 ] alluded that in tourism/hospitality, guest rooms and tourism destination centres can be redesigned in such a manner that they stand out among the basics and overcome the challenges of perishability in the service industry. “Manufacturing has smaller perishability problems compared to the Tourism/Hospitality, for example, fresh products have a limited life span [ 27 ]. Chittium [ 28 ] describes heterogeneity as the standardisation of commodities that service quality can tightly control so that the consumer can derive all the benefits before purchase occurs. Karmarkar [ 29 ] contends that the standardisation of commodities, while it is a feature of service quality, it also true in manufacturing commodities. “Using the SBMI, services can be standardised depending on the service offering [ 30 ]. Kim and Mauborgne [ 31 ] state that even though it takes the firms to divert from their ways of service offering, a service innovation attribute goes beyond that. The service innovation encounter and interactivity is not limited to services. The generality of the inseparability property for services is limited [ 32 ]. Tourism/hospitality firms like the hotels, are ideal examples of a market which could benefit from the implementation of service innovation. Service innovation is the most crucial aspect since the service lacks a sense of ownership and business model innovation comes in to address this challenge [ 11 , 33 ] since the service encounter is characterised by the interaction between providers and customers. However, there are also the cases of no encounter and numerous variations and degrees of intensity in between the close encounter and the no encounter. To explain interactivity in the service encounter, the model by Gummerson [ 34 ] which portrays different roles and interactions that are critical in marketing but focusing on the customer is cited. The service encounter is not only about marketing. It is also about production, delivery, complaints, innovation and administration and the same employee often fulfils several of these functions ( Figure 2 ).

Illustration of interactivity in service encounter (source: Gummerson [ 34 ]).

Service innovation in the service industry becomes a crucial point because the hotel service offerings are the major contributors to the growth in the service sector and of the entire economy [ 2 ]. The capacity to innovate implies that there is potential in adoption and the use of innovation in the service sector is increasingly seen as a factor in determining competitiveness [ 35 ]. This capacity in the hospitality/hotel sector produces a positive relationship in alignment to the business model innovation concept in the service industry. However, there are factors that affect business model innovation in the tourism/hospitality industry. These are market factors and competition, firm (hotel) size, supplier driven logistics innovation, service innovation, and service delivery.

Durst et al. [ 36 ] argue that despite the increasing amount of literature on service innovation, there is a paucity of empirical research that interrogates the measurement of the impact of service innovation at firm level. The development of the capacity to monitor service innovation processes and the ability to evaluate the impact of service innovation is necessary prior to the implementation of service innovation strategies [ 36 ]. According to Pigner [ 37 ], a service innovation describes the value in what the firm gives to different consumers and it also portrays the capabilities needed in re-creating the service offering. It also aims at generating profitable and sustainable revenue and value. The service innovation gives a broad spectrum of the total benefits to a consumer. Chesbrough and Rosenbloom [ 38 ] posit that some of the service innovation elements are value proposition, value chain structure, revenue generation and profit margins and competitive strategy. The innovation orientation implies that service offering involves a turnaround strategy leading to service innovation [ 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 ]. The implementation of service innovation is used as an effective strategic tool to generate competitive advantage for the firm or to regenerate growth in saturated markets [ 42 ] since service innovation allows for creating excellence in the service offering and the development of more efficient cost structures, as well as delivery and technology systems [ 10 ].

2.2 Business model concept

The process of business model construction is a part of business strategy. The creation, delivery and capture of value by an organisation is indicative of the organisation’s business model innovation orientation [ 43 ]. Literature is loaded with diverse definitions and interpretations of a business model. Some define business models as “the design of organisational structures to enact a commercial opportunity” [ 44 ]. Others extend the “design logic” by emphasising mechanisms by which entrepreneurs create and sustain successful growth of firms [ 45 ]. The establishment of any business is premised on a particular business model that fits into its business units and gives a description of the architecture and capture mechanisms employed by the business enterprise [ 46 ]. Importantly, the business model describes the manner by which the business enterprise delivers value to customers, entices customers to pay for value, and converts those payments to profit [ 46 ]. Furthermore, the business model is utilised by management to hypothesise on customer wants, and how an enterprise can organise to best meet customer needs [ 46 ]. Chen [ 47 ] asserts that business models operate as recipes for strategic tools and creativity.

2.2.1 Business model components

The business model innovation (BMI) model is composed of six critical elements as depicted in Figure 3 . The BMI model is largely used by the manufacturing industry rather than the service industry.

BMI model (source: Teece [ 45 ]).

2.2.2 Business model innovation occurrence

The business model design incorporating themes of the design perspective and design content give rise to business model occurrence [ 14 ]. While design themes focus on the business’ principal value creation drivers; the design content interrogates the planned activities providing scaffolding and sequencing of the activities [ 14 ].

2.3 Tourism/hospitality theories

Hospitality is having a core which addresses the management of food, beverages, accommodation and entertainment [ 48 ]. It is also an act of welcoming kindness or offering towards a stranger in the form of food and entertainment [ 49 ]. Hospitality theories can be stated as the following: social exchange theory, an expectancy theory of motivation, the Otus theory of demand and supply, rational exchange theory, practical theory of motivation, management theory, service marketing theory, theory of innovation, learning theory and Marlow’s hierarchy of hotel expectations.

2.3.1 Social exchange theory

The theory is premised on the social behaviour through an exchange process and the exchange entails maximisation of benefits and minimisation of costs [ 50 ]. The theory states that an individual can predict the potential advantages and disadvantages of social relationships and when the disadvantages are more than the advantages, it becomes costly and portrays negatively in monetary value and time [ 50 ]. A benefit from the relationship comes in the form of fun, friendship, companionship and social support. However, Cook and Rice [ 51 ] contend that the theory hinges on the realisation that any form of interaction that elicits disapproval can be proven by computing the level of reward or punishment emanating from interaction. This observation is in agreement with Crossman’s [ 52 ] formula on the prediction of individual responses from given interactions. In the hospitality/hotel context, management can interact with potential customers as a way of building social relationships and at the end, gain profits and realise repeat purchases of the hotel services and products. Through social exchange theory, management of the hotels is also able to position services using possible strategies that can help in the financial performances and the hotel reputation.

2.3.2 Expectancy theory

Osteraker [ 53 ] argues that, in the tourism and hospitality industry, the theory focuses on processes that target employee motivation and the achievement thereof. Fundamentally, the theory facilitates, via a framework, the assessment and evaluation of employee knowledge, skills and attitudes [ 54 ]. Van Eerde [ 55 ] contend that the expectancy theory enables management to assess accrual of internal and external rewards to individual employees in alignment with performance. It is argued that more attitudinal as opposed to behavioural preferences have a stronger link with the expectancy theory due to biases associated with self-report measures [ 56 , 57 ]. In agreement with Van Eerde [ 55 ], Tien [ 58 ] points out that the expectancy theory facilitates the measurement of employee motivation. Sansone and Harackiewicz [ 59 ] contend that the expectancy theory is fundamentally a “process theory” as it deals with decision-making processes in the determination of the level of employee motivation and its (motivation) relationship with set productivity goals. Hotel employees need to have job knowledge, learning philosophy, time management and intelligence in executing their jobs and to possess certain skills that help during the processes in delivering the services. The theory applies specifically to the hotel employees rather than the hotel management. Without motivation, the hotel employees will not succeed in their career endeavours and this will also reflect on poor performance and the hotels’ reputation and financial performances.

2.3.3 The Otus theory

The Otus theory of hotel demand and supply is premised on the size and structure of the hotel in a specific period [ 60 ]. It stipulates that there is a positive relationship between the contribution of service business to GDP and the demand of domestic leisure for hotels [ 12 , 60 ]. Additionally, the theory states that the greater the hotel supply in terms of size and structure, the greater the concentration of hotel in brands [ 60 ]. Due to the changing environment and trends in the hospitality industry, the Otus theory, is helpful in that, in order for the hotels to operate and contribute to the GDP, there is a need to come up with a strategic direction that can address the changes. Service innovation can come into play as a solution. Knowles [ 61 ] states that the macro- and micro-environments of the tourism and hospitality industry experience tremendous changes that affect business performance and bring about challenges. In tandem with the observations of Knowles [ 61 ], Nicola [ 62 ] reports that the tourism and hospitality industry is experiencing transformation which has made life more globally oriented, uncertain and dynamic. The emergence of new markets, the interaction between emerging and emerged economies and the resultant extension and intensification of globalisation and market changes in business have increased competition at a global level [ 63 ]. The climatic changes and sustainability in the tourism and hospitality industry whereby “green argument” is introduced, forces new consumer behaviours that impact more on perspectives [ 64 ], thus impacting on consumer decisions on spending on hospitality/hotel industry services.

2.3.4 Management theory

Mahmood et al. [ 65 ] contend that management theories come in a variety of forms: classical, humanistic and situational management theories. The classical management theories are characterised by salient features that include chain of command [ 64 ], division of labour [ 66 ], unidirectional downward influence [ 66 ], autocratic leadership [ 66 ] and predictable behaviours [ 67 ]. Atkinson and Stiglitz [ 68 ] contend that the need to focus on authority and structure for employees gave rise to the management theory. The hierarchies in the theory are targeted to instill discipline, control planning, organising within the workplace [ 69 ]. The business purpose of the management theory is to measure work performance and acknowledge corporate culture [ 70 ]. Management theories in the tourism/hospitality sector are derived from the classical management theories and translate into service marketing theories which inform tourism/hospitality management practices [ 18 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 ]. With regard to planning, the theory advocates that management executes a consumer needs analysis for the purposes of satisfying the observed consumer needs. Management is tasked to ensure that their subordinates are customer service oriented and deliver quality service [ 77 , 78 ]. In a tourism/hospitality set up, labour is organised into specialised service units, for example, restaurant services, tourist attractions, housekeeping and accommodation and entertainment.

2.3.5 Maslow hierarchy of hotel expectations theory

Maslow hierarchy of hotel expectations theory expectancy theory is founded on Abraham Maslow’s 1943 ground-breaking research paper into his hierarchy of hotel expectation. According to Mogelonsky [ 79 ] the hotel expectancy theory describes consumer expectations, perceptions and reactions when not satisfied with the service provided. Beginning from the bottom to the top of Maslow’s hierarchy, the theory seeks to satisfy guests’ needs in accordance with the pyramid. At the base is the expectation to fulfil physiological needs exampled by availability of bedding and breakfast. This is followed by safety needs, which in a hotel set up, could be the expectation for the provision of healthy food, shelter and security. The next level of expectation would be the need to satisfy social needs, for example, respect of guests’ privacy. Following the satisfaction of social needs, in the hospitality/hotel set up, the next level would be to meet self-esteem needs, such as the building of reputation and importance. The last level would to be to meet the self-actualisation needs. According to Siguaw et al. [ 80 ], in tourism/hospitality, a learning philosophy denotes the acquisition and transfer of knowledge, skills and attitudes that facilitate the tourist destinations/hospitality to innovate. Practically, learning philosophies in tourist destinations/hospitality are concerned with judicious implementation and maintenance of operational standards that become embedded in all the employees of the tourism/hospitality [ 81 ]. Thus, a learning philosophy is reflective of the managerial behaviour and its genuine belief in the contribution of employees.

2.3.6 Theory of reasoned action

According to Buttle [ 82 ], the theory of reasoned action (TORA) is anchored on the understanding that humans make rational decisions based on the factual information available to them. The theory posits that human decision making is informed by the possible implications stemming from the execution of the decision. In tourism/hospitality, TORA could be used as a business/marketing strategic tool [ 83 ] as it could be used to assess the variance in the intention to consume tourism/hospitality services on the next business trip. Cedicci and Trehan [ 83 ] further assert that of the two predictors in the TORA, attitudes towards the act are the most significant contributor, thus it could be inferred that attitude rotates around service quality expectations and reflects the implications for business/marketing strategy [ 84 ].

2.4 Strategic direction in tourism/hospitality

Strategic direction can be defined as the extent to which innovation orientation takes up a turnaround strategy towards achieving service innovation in an organisational set up [ 21 ]. It also gives organisational direction in alignment with factors like planning and designing and recreating so that innovation takes place [ 85 ]. Strategies are directional vessels that reflect the existence of the hotel on a long and short term basis. They are more numerate and plans can also be viewed as an expression of strategic direction of the hotel to meet the needs in a particular market. Strategies may be made on how to compete and choose markets and decisions on advertising and people to employ in tourism/hospitality. Hurley and Hult [ 21 ] denote that service innovation entails redesigning and recreating strategies that provide for the best solution, especially in difficulty economic situations such as those of emerging countries. In order for tourism/hospitality to achieve service innovation, there is a dire need for innovation orientation strategies to be in alignment with the planning, designing and recreating and responding to all the service innovation factors [ 85 ], if planning, designing and recreating are considered in tourism/hospitality as measurements in attaining the service innovation and the output performance. Superior service may discourage, but not prevent, customer defections to competitors, hence the requirement for businesses to have an effective customer retention programme [ 86 ]. In tourism/hospitality retention: (T/HR) is a perpetual non-financial measure of the business’ (hotel’s) capability to maintain consumers of its products [ 86 ]. The goal of T/HR is to help companies retain as many TOURISTS as possible through customer loyalty and brand initiatives [ 42 ]. T/HR retention begins with the first contact a TOURIST has with a company and continues through the lifetime of the relationship [ 42 ]. T/HR involves processes and activities undertaken by the company to prevent the TOURIST defecting to competitors. When effectively practiced, TOURIST retention creates competitive advantage for the business by: increasing revenue inflows towards the service offering, lowering customer acquisition cost and increasing referrals to the business [ 87 ]. TOURIST retention builds on the percentage of customer relationships which, once established, are maintained on a long term basis in alignment with the service offering and tourism/hospitality reputation that stimulates RE-PURCHASE INTENTION rates that are important in volatile industries characterised by fluctuating prices and product values. These positive attributes of an effective CR scheme on business performance are especially true to the tourism/hospitality industry as proven by previous studies that have established a positive link in customer retention, BUSINESS performance and market performance [ 88 ] ( Figure 4 ).

Illustration of strategic direction and service innovation relationships in tourism and hospitality (source: Chivandi [ 6 ]).

2.4.1 Occupancy rate

Occupancy rate has a bearing on tourism/hospitality business performance. According to Fitzsimmons and Fitzsimmons [ 89 ], occupancy rate is the number of hotel rooms taken out in comparison to the total number of hotel rooms. For example, a hotel with a capacity of 100 rooms occupied would have an estimated 75% occupancy rate. Table 1 shows the global hotel occupancy rates in 2012 [ 90 ].

Global hotel monthly occupancy rates in 2012.

Source: Statistica USA [ 90 ].

2.5 Reputation in tourism/hospitality

Literature on corporate reputation centres on reputation as a construct [ 91 ]. Although there are several definitions of reputation [ 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 ], the common features of reputation as a concept revolve around the perception consumers have of the company, based on the company’s past performance in service delivery [ 95 , 96 , 97 ]. There is a perception that the company’s past performance in service delivery influences its future prospects, thus reputation impacts on the stakeholder and customer’s view of the company [ 94 , 95 , 96 ]. Fombrun [ 98 ] contends that reputation hinges on perception and trust about the company’s ability to maintain a currently acceptable service offering in the future. This ability is argued to influence the level of trust and appeal that the company has in comparison to its competitors. Reputation has a bearing on service quality, corporate image and governance, labour relations and business performances [ 99 , 100 ]. As an important aspect of organisational set up, reputation creates an environment that allows the organisation to establish a competitive advantage and lasting relationships with stakeholders [ 101 ]. Although deemed an intangible resource, a good reputation over and above enabling an organisation to maintain competitive advantage [ 99 , 100 ], capacitates the organisation to enjoy higher customer retention rates and an increase in sales [ 102 ]. A good reputation is a vital resource that provides the organisation with a basis for sustaining competitive advantage, given its (good reputation) valuable and hard to imitate characteristics [ 99 , 100 ]. In a hotel set up, a good reputation and an attractive environment are among the key drivers of repeat purchases and improved business performance. From a business perspective, reputation impacts on customers, investors, employees, business partners and the media. The impact that reputation has on business performance is central to the genesis of a positive corporate image, as illustrated in the schematic diagram below.

The empirical evidence is shown in the theory of hotel management where managers employ different strategies within an organisation in order to gain profits and rewards ( Figure 5 ).

Illustration of reputation and service innovation relationships in tourism and hospitality (source: Chivandi [ 6 ]).

Reputation refers to a matter of perception and trust about the company’s past actions and future prospect’s value that describe the firm’s overall appeal to all its key constituents when compared to leading rivals [ 98 ]. As an important aspect of organisational set up, reputation creates an environment that allows the organisation to establish a competitive advantage and lasting relationships with stakeholders [ 101 ] by positively impacting on service quality, corporate governance, employee relations, customer service, intellectual capital and financial performance [ 99 , 100 ]. In service innovation, a good reputation is identified as an intangible resource which may provide the organisation with a basis for sustaining competitive advantage, given its valuable and hard to imitate characteristics [ 99 , 100 ]. The benefits of a good reputation include higher customer retention rates and associated increased sales and product selling prices [ 102 ] ( Figure 6 ).

Illustration of financial performances and service innovation relationships in tourism and hospitality (source: Chivandi [ 6 ]).

Gupta and Zeitham [ 103 ] assert that measures into financial performance, inclusive of factors such as revenue, profit, stock prices, reputation, customer loyalty and satisfaction, constitute business performance. The financial measures can be further broken down into average occupancy rate, lodgings index, and market share index in hospitality/hotels [ 104 ].Customer retention and hotel reputation refer to perceptional measures [ 9 ]. Ottenbacher and Gnoth [ 105 ] contend that in the hospitality/hotel sector, financial performance strongly impacts on service innovation.

3. Conclusions

Technological superiority by itself is no longer a panacea for firms to sustain a leading edge in the marketplace. The development of service marketing as a service strategic tool in tandem with service innovation is critical to the development and sustenance of competitive advantage, although competitive advantage on profitability is also affected by the number of service divisions which are representatives of individual profit centres [ 105 ]. According to Davis [ 95 ], service can be expressed in qualities: search qualities, experience qualities and credence qualities. According to Schwaiger [ 91 ] suggested a pyramid model of service quality and delivery that includes the internal service marketing and interactive service marketing. Internal service marketing entails marketing efforts aimed at service firms in order to empower them to produce a better service offering [ 91 ]. The interactive service marketing describes the interrelations between the employee and the customer. Service innovation entails a better way of executing a service that (better way) hinges on the utilisation of unique and better combinations of the service production elements. Overall, this translates to increased customer attraction and retention thus contributing to business growth [ 18 ]. Innovation in services springs from managerial techniques and the introduction of innovation and service innovation. A workforce empowered with a set of creative and knowledge skills is a key element in service innovation. In terms of the additional workforce’s skills, many service firms depend on external expertise for innovation. Pigner [ 37 ] notes that the service business model depicts the value in hotel services that gives and portrays the capabilities needed in creating marketing innovation. The model also aims at generating profitable and sustainable revenue and value propositions. Over and above delivering improved service to the consumer, service business innovation improves business performance [ 38 ]. Value chain structure, revenue generation, market segments, value network, value proposition and competitive strategy constitutes business model innovation that has been used in the manufacturing sector as opposed to the services sector [ 38 ]. Service innovation and service quality orientation as a business strategic tool in the tourism/hospitality sector brings a positive relationship. The research constructs such as the strategic direction and service innovation relationships are positively significant and other factors such as quality performance and delivery also contribute towards service innovation in tourism and the hospitality industry, thus affecting the business strategic direction positively [ 6 ] and furthermore, the discussions in this study imply that players in the tourism and hospitality industry in emerging countries must take into consideration important decisions concerning certain practices and policies. Contribution to practice - another important expectancy is that a research must contribute to practice a relevant research quality measure, particularly if the investigation is mostly in the domain of applied research. This type of contribution acknowledges the need to provide relevant information to practitioners or policy makers, so that the research implications and inferences can assist them in decision making that relates to business or societal issues. As marketing management is applied research, applicability to practice necessitates a context-specific and robust classification during the theory building phase. In addition, application of service marketing to practice has been a common topic in marketing management research. Hence, recently it has become essential to connect theory with practice. Accordingly, this study contributes to practice by helping marketers and policy makers to devise appropriate service innovation marketing strategies and policies respectively. Due to the fact that this study provides fresh and contemporary evidence, service marketing practitioners and policy marketers in the tourism/hospitality industry are bound to make informed decisions, supported by reliable information. Managerial implications in this study imply that a good research project often helps in guiding important decisions on certain practices and policies and that also helps management and all the top team involved in making the best decisions, strategies, policies and planning. In a nutshell, the awareness of the harmful effects of the PESTEL environment and natural climate changes has created new opportunities and challenges for both policy makers and players in the tourism and hospitality sector regionally. These also help management and all the team members involved in making the best informed decisions, strategies, policies and plans.

- 1. Christie IT, Crompton DE. Tourism in Africa: Africa Region Working Paper Series, 12. Washington, DC, USA: World Bank; 2001

- 2. Wirts J, Ehret M. Creative construction, how business services drive economic evolution. European Business Review. 2009; 21 (4):380-394

- 3. Maswera T, Dawson R, Edwards J. E-commerce adoption of travel and tourism organisations in South Africa, Kenya, Zimbabwe and Uganda. Telematics and Informatics. 2008; 25 (3):187-200

- 4. Riquelme H. Do venture capitalists’ implicit theories on new business success/failure have empirical validity? International Small Business Journal. 2002; 20 (4):395-420

- 5. Burgess C. Evaluating the use of the web for tourism marketing: A case study from New Zealand. Tourism Management. 2000; 23 :557-561

- 6. Chivandi A. The influence of service innovation business performance in the hospitality sector [PhD thesis]. University of the Witwatersrand; 2016

- 7. Wisniewski M. Using SERVQUAL to assess customer satisfaction with public sector services. Managing Service Quality. 2001; 11 (6):380-388

- 8. Karambakuwa RT, Shonhiwa T, Murombo L, Mauchi FN, Gopo NR, Denhere W, et al. The impact of Zimbabwe tourism authority initiatives on tourist arrivals in Zimbabwe (2008-2009). Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa. 2011; 13 (6):22-32. ISSN: 1520-5509

- 9. Agarwal S, Erramilli MK, Chekitan SD. Market orientation and performance in service firms: Role of innovation. Journal of Services Marketing. 2003; 17 (1):68-82

- 10. Grönroos C. Service Management and Marketing. 3rded ed. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2007

- 11. Lovelock C, Gummesson E. Wither service marketing? In search of new paradigm and fresh perspectives. Journal of Service Research. 2004; 47 :9-20

- 12. Chivandi A, Chinomona R, Maziriri ET. Service innovation capabilities towards business performances in the hotel sector of Zimbabwe. African Journal of Hospitality Tourism and Leisure. 2017; 6 (2):16. ISSN: 2223-814X

- 13. Vargo SL, Lusch RF. Why “service”? Journal of the Academic and Marketing Science. 2008; 36 :25-38

- 14. Zott C, Amit R. The Business Model: Theoretical Roots, Recent Development and Future Research. Madrid, Spain: IESE Business School, University of Navara; 2009

- 15. Ekinci Y, Sirakaya E. An examination of the antecedents and consequences of customer satisfaction. In: Couch GI, Perdue RR, Timmermans HJP, Uysal M, editors. Consumer Psychology of Tourism, Hospitality and Leisure. Wallingford, United Kingdom: CABI Publishing; 2004. pp. 189-202

- 16. Chen J-S, Tsou H-T, Huang Y-H. Service delivery innovation: Antecedents and impact on firm performance. Journal of Service Research. 2009; 12 (1):36

- 17. Dincer OC. Ethnic diversity and trust. Contemporary Economic Policy. 2011; 29 (2):284-293

- 18. Wood RC, Brotherton B. The nature and meanings of ‘Hospitality’. Hospital Management. 2008; 37 :35-61

- 19. Alam I, Perry C. A customer-oriented new service development process. Journal of Services Marketing. 2002; 16 (6):515-534

- 20. Imara Report. World Tourism Travel Export. Imara: S.P. Reid (Pty) Ltd; 2011

- 21. WTTC. World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC) Report. 2010

- 22. Hurley R, Hult G. Innovation, market orientation, and organizational learning: An integration and empirical examination. Journal of Marketing. 1998; 62 (3):42-52

- 23. Gordon M. Understanding Moore’s Law: Four Decades of Innovation. New York, USA: Chemical Heritage Foundation; 2006. pp. 67-84

- 24. Bettencourt LMA, Lobo J, Strumsky D. Invention in the city: Increasing returns to patenting as a scaling function of metropolitan size. Research Policy. 2010; 36 :107-120

- 25. Brinkley. Wire storage racks, no box springs. Wall Street Journal. 2003:B1

- 26. Namasivayam K, Enz CA, Siguaw JA. How wired are we? Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly. 2000; 41 (6):40-48

- 27. Gummerson E. Implementing the marketing concept: From service and value to lean consumption. Marketing Theory. 2006; 6 (3):291-293

- 28. Chittium R. Budget hotels to get a makeover: In bid for business travellers; major chains plan boutiques, area rugs and glassed-in showers. Wall Street Journal. 2004; 15 (6):555-576

- 29. Karmarkar U. Will you survive the services revolution? Harvard Business Review. 2004; 82 (6):100-108

- 30. Schall M. Best practices in the assessment of hotel-guest attitudes. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly. 2003; 44 (2):51-65

- 31. Kim C, Mauborgne R. Value innovation: The strategic logic of high growth. Harvard Business Review. 2000; 75 (1):102-113

- 32. Olsen MD, Connolly DJ. Experience-based travel. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly. 2000; 41 (1):30-40

- 33. Maglio PP, Stephen L, Vargo NC, Jim S. The service system is the basic abstractionof service science. Information Systems and e-Business Management. 2006; 7 :395-340

- 34. Gummerson E. Relationship marketing: Its role in the service economy. In: Glynn WJ, Barnes JG, editors. Understanding Services Management. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. pp. 244-268

- 35. Eatwell L. The New Palgrave, a dictionary of economics. Economics. 1987; 15 (4):303-319

- 36. Durst S, Anne-Laure M, Petro P. Service Innovation and its Impact: What Do we Know about? Investigaciones Europas. 2015; 21 :65-72

- 37. Pierre B, James M, Leyland P. Innovation or customer orientation? An empirical investigation. European Journal of Marketing. 2004; 38 (9/10):1065-1090

- 38. Chesbrough H, Rosenbloom RS. The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: Evidence from Xerox Corporation’s technology spin-off companies. Industrial and Corporate Change. 2002; 11 (3):529-555

- 39. Hamel G. Leading the Revolution. USA: Harvard Business School Press; 2000

- 40. Rayport J, Jaworski B. E-commerce strategies as a tool of innovation. The Implementation of E-commerce Strategy Requires Four Critical Forces: Technology, Capital, Media, and Public Policy. 2nd ed. Boston, USA: McGraw-Hill; 2006:142

- 41. Afuah A, Tucci CL. Internet Business Models and Strategies. Boston, New York, USA: McGraw-Hill; 2003

- 42. Reinartz W, Ulaga W. How to sell services more profitably. Harvard Business Review. 2008; 86 (5):90

- 43. Osterwalder A, Pigneur Y, Clark T. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers. UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2010

- 44. George G, Bock AJ. The business model in practice and its implications for entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 2011; 35 (1):83-111

- 45. Teece DJ. Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Planning. 2010; 43 (2-3):172-194

- 46. Baden-Fuller C, Morgan M. Business Models, Business Strategy and Managing Business Models for Innovation. USA: Long Range Planning; 2010; 43 (2-3):172-194

- 47. Chen TF. Building a platform of Business Model 2.0 to creating real business value with Web 2.0 for web information services industry. International Journal of Electronic Business Management. 2009; 7 (3):168-180

- 48. Brotherton. Towards a definitive view of the nature of hospitality and hospitality management. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 1999; 11 (4):165-173

- 49. Oxford English Dictionary, London Press. 1970

- 50. Cherry AM. Technology and Innovation. USA: Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences; 2010

- 51. Cook KS, Rice E. Social exchange theory. American Sociological Review. 2003; 43 :721-739

- 52. Crossman A, Harris P. Job satisfaction of secondary school teachers. Educational Management Administration and Leadership. 2006; 34 :29-46

- 53. Osteraker MC. Employees values in motivation theories, it contributes greatly in the process of motivation increase. Serbian Journal of Management. 2010; 5 (1):59-76

- 54. Chen Y, Lou H. An expectancy theory model for hotel employee motivation: Examining the moderating role of communication satisfaction. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration. 2002; 9 (4):327-351

- 55. Van Eerde TH. Vroom’s expectancy models and work related criteria: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1996; 81 (5):575-586

- 56. Gollwitzer PM. Goal achievement: The role of intentions. European Review of Social Psychology. 1993; 4 (1):141-185. DOI: 10.1080/14792779343000059

- 57. Kanfer. Motivation theory and industrial/organizational psychology. In: Dunnette MD, Hough L, editors. Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. Vol. 1. CA, USA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1990

- 58. Tien R. Technology, Academic leadership of performing groups, individual creativity and group ability to utilize individual creative resources; a multilevel model. Academy of Management Journal. London: Imperial college Press. 2000; 45 :315-330

- 59. Sansone C, Harackiewicz JM. Looking Beyond Rewards: The Problem Promise of Intrinsic Motivation. UK: Academic Press; 2000

- 60. Slattery P. Otus theory of hotel demand and supply. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2008. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2008.06.005 (Paper series No. 12)

- 61. Knowles ES. Economic Theory Resistance and Persuasion. Mahwah, New Jersey, 2003. ISBN-13: 978-0805844870

- 62. Nicola C, Lolita L, Evangelos P. Implementation of quality management system with ISO 22000 in food Italian companies. Quality—Access to Success. 2010; 19 (165):125-131

- 63. Yeoman I. Luxury markets and premium pricing. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management. 2005; 4 (4):319-328

- 64. Taylor C. Perceived processing strategies of service. 2005. DOI: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2005.tb02228.x. In press

- 65. Mahmood Z, Basharat M, Bashir Z. Review of classical management theories. International Journal of Social Sciences and Education. 2012; 2 (1):512-555

- 66. Weijrich H, Koontz H. Management: A Global Perspective. 10th ed. New Delhi, India: McGraw; 1993

- 67. Shaik AH. Public Perception Towards Petroleum Museum And The Grand Old Lady Miri Howard Margie Anak Sidi 49714 Shaik Azahar Shaik Hussain. 2008. Doi: 10.13140/Rg.2.2.20861.67042. In press

- 68. Atkinson AB, Stiglitz CJE. A new view of technological change. The Economic Journal. 1969; 79 (15):573-578

- 69. Stoner JAF, Freeman RE, Daniel R. Business Management. 6th ed. New Delhi, India: Prentice Hall; 2003

- 70. Zikmund WG. Reliability and validity issues in research: Any remaining errors or omissions. South African Journal of Human Resources Management. 2003; 9 (1). DOI: 10.4102/sajhrm.v9i1.302

- 71. Caves RE. Industrial organisation, corporate strategy and structure. Journal of Economic Literature. 1980; 18 (1):182-264

- 72. Wernerfelt. Theoretical foundation: The resource-based view (RBV) of the firm…1984. Wiebaden: Springler Gambler Publisher. 1984; 5 :171-180. ISBN: 978-3-658-14857-7

- 73. Cohen W. Empirical studies of innovative activity. In: Stoneman P, editor. Handbook of the Economics of Innovation and Technological Change. USA: Blackwell; 1995

- 74. Gallouj F, Weinstein O. Innovation in services. Research Policy. 1997; 26 (4-5):537-556

- 75. Hollensen S. Marketing Management: A Relationship Approach. Harlow, UK: Prentice Hall; 2003. p. 787

- 76. Tseng C, Goo YJ. Intellectual capital and corporate value in an emerging economy: Empirical study of Taiwanese manufacturers. R&D Management. 2005; 35 :187-201

- 77. Baum JAC, Mezias JS. Localized competition and organisational failure in the Manhattan Hotel Industry. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1992; 37 (4):564-580

- 78. Chung W, Kalnins A. Agglomeration effects and performance: A test of the Texas lodging industry. Strategic Management Journal. 2001; 22 (10):969-988

- 79. Mogelonsky L. An equal opportunity recession. American Demographics. 1991; 13 (12):9

- 80. Siguaw JA, Simpson PM, Enz CA. Conceptualizing innovation orientation: A framework for study and integration of innovation research. Journal of Product Innovation Management. 2006; 23 (6):556-574

- 81. Medlik S. Dictionary of Travel, Tourism and Hospitality. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1996

- 82. Buttle F. SERVQUAL: Review, critique, research agenda. European Journal of Marketing. 1996; 30 (1):8-32

- 83. Cedicci T. The hospitality industry and its future in the US And Europe. Opinion Articles International Society of Hospitality. 2007. Available from: https://www.hospitalitynet.org

- 84. Bitner MJ, Booms BH, Tetreault MS. The service encounter: Diagnosing favourable and unfavourable incidents. Journal of Marketing. 1990; 54 :71-84

- 85. Zhou KZ, Gao GY, Yang Z, Zhou N. Developing strategic orientation in China: Antecedents and consequences of market and innovation orientations. Journal of Business Research. 2005; 58 (8):1049-1058

- 86. Schreiber T. Measuring information transfer. Physical Review Letters. 2000; 85 (2):461-464

- 87. Sandvik IL, Sandvik K. The impact of market orientation on product innovation and business performance. Journal of Product Innovation Management. 2003; 30 (3):599-611

- 88. Sin LYM, Alan CB, Tse V, Heung CS, Yim FHK. An analysis of the relationship between market orientation and business performance in the hotel industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2005; 24 (4):555-577

- 89. Fitzsimmons JA, Fitzsimmons MJ. Service Management: Operations, Strategy. In: Information Technology. Irwin: McGraw-Hill; 2010

- 90. Statistica USA. Travel and Tourism Industry in the U.S.—Statistics & Facts. USA: United States Statistica. 2015

- 91. Schwaiger M. Measuring the impact of corporate reputations on stakeholder behavior. In: Burke RJ, Martin G, Cooper CL, editors. Corporate Reputation: Managing Threats and Opportunities. New York, USA: Ashgate Publishing Limited; 2005. pp. 61-88

- 92. Saxton WO. Quantitative comparison of images and transforms. Journal of Microscopy. 1998; 190 (1-2):52-60

- 93. Gotsi M, Wilson MA. Corporate reputation: Seeking a definition. Corporate Communications: An International Journal. 2001; 6 (1):24-30

- 94. Balmer JMT. The nature of corporate identity: An explanatory study undertaken within BBC Scotland [PhD thesis]. Glasgow: Department of Marketing, University of Strathclyde; 2001

- 95. Davies G, Miles L. Reputation management: Theory versus practice. Corporate Reputation Review. 1998; 2 (1):16-27

- 96. Birkigt KK, Stadler MM. Corporate identity, Grundlagen, Functionen und Beispielen, Moderne Industrie, Landsbergan Lech. In: van Riel CBM, editor. Principles of Corporate Communication. London: Prentice-Hall; 2003. p. 1995

- 97. Brown TJ, Dacin A. The company and product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. Journal of Marketing. 1997; 61 :68-84

- 98. Fombrun CJ. Reputation: Realizing value from the corporate image. The Academy of Management Executive. 1996; 10 (1):99-101

- 99. Barney JB. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management. 1991; 17 :99-120

- 100. Hall PA. Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state: The case of economic policymaking in Britain. Comparative Politics. 1993; 25 (3):275

- 101. Boyd R, Richerson PJ. The Evolution of Reciprocity in Sizable Groups. USA; 2010. In press

- 102. Shaphiro SP. The social control of impersonal trust. American Journal of Sociology. 1993; 93 :623-658

- 103. Gupta S, Zeitham V. Customer metrics and their impact on financial performance. Marketing Science. 2006; 25 (6):718-739

- 104. Orfila-Sintes F, Mattsson J. Innovation behaviour in the hotel industry. The International Journal of Management Science. 2009; 37 (2):380-394

- 105. Ottenbacher M, Gnoth J. How to develop successful hospitality innovation. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly. 2005; 46 (2):205-222

© 2019 The Author(s). Licensee IntechOpen. This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Continue reading from the same book

Published: 06 November 2019

By Chun-Ho Wu, George To-Sum Ho, Danny Chi-Kuen Ho an...

1241 downloads

By Tish Taylor and Sue Geldenhuys

1553 downloads

By Şenay Sabah

1377 downloads

What Are the 5 Characteristics of Tourism Services?

By Alice Nichols

Tourism services refer to the various services provided to tourists during their trips, such as accommodation, transportation, food, and entertainment. In this article, we will explore the five key characteristics of tourism services.

1. Intangibility

One of the most significant characteristics of tourism services is their intangibility. Unlike tangible products like clothes or gadgets that you can touch and feel before buying, tourism services cannot be seen, touched, or stored. The intangible nature of tourism services makes it challenging for tourists to evaluate their quality before consumption.

Example: A traveler cannot touch or feel a hotel room before booking it. They have to rely on online reviews and ratings or word-of-mouth recommendations to judge its quality.

2. Perishability

Tourism services are perishable in nature, which means they cannot be stored for future use. Hotel rooms, airline tickets, and tour packages have a limited shelf life and must be consumed within a specific time frame. If not consumed in time, they become useless.

Example: A hotel room left unoccupied for a day or two cannot be sold again once the check-in date has passed.

3. Heterogeneity

Tourism services are highly heterogeneous because they are produced and consumed simultaneously by different people with varying expectations and preferences. Each tourist has unique needs and desires that must be met by the service provider.

Example: Two travelers staying in the same hotel room may have vastly different experiences based on their individual preferences for amenities like Wi-Fi access or room service.

4. Inseparability

Tourism services are inseparable from their providers because they are produced and consumed simultaneously. The service provider’s behavior and actions during service delivery can significantly impact the tourist’s experience.

Example: A rude hotel staff member can ruin a tourist’s stay, even if the room itself is of high quality.

5. Variability

Tourism services are highly variable due to their dependence on factors such as seasonality, weather, and customer demand. The same service may be of different quality and value at different times.

Example: A beach resort may offer different rates and experiences during peak season compared to off-season periods.

10 Related Question Answers Found

What are the characteristics of tourism services, what are the characteristics of tourism products and services, what are the service characteristics of tourism, what are the different tourism services, what are tourism services examples, what are tourism products and services, what are the 5 tourism sectors, what are examples of tourism services, what are the types of tourism services, what are the five elements of tourism products, backpacking - budget travel - business travel - cruise ship - vacation - tourism - resort - cruise - road trip - destination wedding - tourist destination - best places, london - madrid - paris - prague - dubai - barcelona - rome.

© 2024 LuxuryTraveldiva

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 8. Services Marketing

Ray Freeman and Kelley Glazer

Learning Objectives

- Explain the meaning of services marketing

- Describe the differences between marketing services and marketing products

- Describe the characteristics of a marketing orientation and its benefits

- Define key services marketing terminology

- Explain the PRICE concept of marketing

- Provide examples of the 8 Ps of services marketing

- Gain knowledge of key service marketing issues and trends

Marketing is a continuous, sequential process through which management plans, researches, implements, controls, and evaluates activities designed to satisfy the customers’ needs and wants, and meet the organization’s objectives. According to Morrison (2010), services marketing “is a concept based on a recognition of the uniqueness of all services; it is a branch of marketing that specifically applies to the service industries”(p. 767).

Marketing in the tourism and hospitality industry requires an understanding of the differences between marketing goods and marketing services. To be successful in tourism marketing, organizations need to understand the unique characteristics of their tourism experiences, the motivations and behaviours of travelling consumers, and the fundamental differences between marketing goods and services.

The Evolution of Marketing

Until the 1930s, the primary objective of businesses was manufacturing, with little thought given to sales or marketing. In the 1930s, a focus on sales became more important; technological advances meant that multiple companies could produce similar goods, creating increased competition. Even as companies began to understand the importance of sales, the needs and wants of the customer remained a secondary consideration (Morrison, 2010).

In 1944, the first television commercial, for Bulova watches, reached 4,000 sets (Davis, 2013). The decades that followed, the 1950s and 1960s, are known as an era when marketing began to truly take off, with the number of mediums expanding and TV ad spending going from 5% of total TV revenues in 1953 to 15% just one year later (Davis, 2013).

The era from approximately 1950 to around 1970 was known as a time of marketing orientation (Morrison, 2010). Customers had more choice in product, this required companies to shift focus to ensure that consumers knew how their products matched specific needs. This was also the time where quality of service and customer satisfaction became part of organizational strategy. We began to see companies develop internal marketing departments, and in the 1960s, the first full-service advertising agencies began to emerge.

Societal marketing emerged in the 1970s when organizations began to recognize their place in society and their responsibility to citizens (or at least the appearance thereof). This change is demonstrated, for example, by natural resource extraction companies supporting environmental management issues and implementing more transparent policies. This decade saw the emergence of media we are familiar with today (the first hand-held mobile phone was launched in 1973) and the decline of traditional marketing through vehicles such as print; the latter evidenced by the closure of LIFE Magazine in 1972 amid complaints that TV advertising was too difficult to compete with (Davis, 2013).

The mid-1990s ushered in the start of the online marketing era. E-commerce (electronic commerce) revolutionized every industry, perhaps impacting the travel industry most of all. Tourism and hospitality service providers began making use of this technology to optimize marketing to consumers; manage reservations; facilitate transactions; partner and package itineraries; provide (multiple) customer feedback channels; collect, mine, analyze, and sell data; and automate functions. The marketing opportunities of this era appear limitless. Table 8.1 summarizes the evolution of marketing over the last century.

Typically, the progression of marketing in tourism and hospitality has been 10 to 20 years behind other sectors. Some in the industry attribute this to the traditional career path in the tourism and hospitality industry where managers and executives worked their way up the ranks (e.g., from bellhop to general manager) rather than through a postsecondary business education. It was commonly believed that to be a leader in this industry one had to understand the operations inside-out, so training and development of managers was based on technical and functional capabilities, rather than marketing savvy. And, as we’ll learn next, marketing services and experiences is distinct and sometimes more challenging than marketing goods. For these reasons, most businesses in the industry have been developing marketing skills for only about 30 years (Morrison, 2010).

Differences Between Goods and Services

There are four key differences between goods and services. According to numerous scholars (Regan; Rathmell; Shostack; Zeithaml et al. in Wolak, Kalafatis, & Harris, 1998) services are:

- Heterogeneous

- Inseparable (simultaneously produced and consumed)

The rest of this section details what these concepts mean.

Intangibility

Tangible goods are ones the customer can see, feel, and/or taste ahead of payment. Intangible services, on the other hand, cannot be “touched” beforehand. An airplane flight is an example of an intangible service because a customer purchases it in advance and doesn’t “experience” or “consume” the product until he or she is on the plane.

Heterogeneity

While most goods may be replicated identically, services are never exactly the same; they are heterogeneous . Variability in experiences may be caused by location, time, topography, season, the environment, amenities, events, and service providers. Because human beings factor so largely in the provision of services, the quality and level of service may differ between vendors or may even be inconsistent within one provider. We will discuss quality and level of service further in Chapter 9.

Inseparability

A physical good may last for an extended period of time (in some cases for many years). In contrast, a service is produced and consumed at the same time. A service exists only at the moment or during the period in which a person is engaged and immersed in the experience.

Perishability

Services and experiences cannot be stored; they are highly perishable . In contrast, goods may be held in physical inventory in a lot, warehouse, or a store until purchased, then used and stored at a person’s home or place of work. If a service is not sold when available, it disappears forever. Using the airline example, once the airplane takes off, the opportunity to sell tickets on that flight is lost forever, and any empty seats represent revenue lost.

Planning for Services Marketing

To ensure effective services marketing, tourism marketers need to be strategic in their planning process. Using a tourism marketing system requires carefully evaluating multiple alternatives, choosing the right activities for specific markets, anticipating challenges, adapting to these challenges, and measuring success (Morrison, 2010). Tourism marketers can choose to follow a strategic management process called the PRICE concept , where they:

- P: plan (where are we now?)

- R: research (where would we like to be?)

- I: implement (how do we get there?)

- C: control (how do we make sure we get there?)

- E: evaluate (how do we know if we got there?)

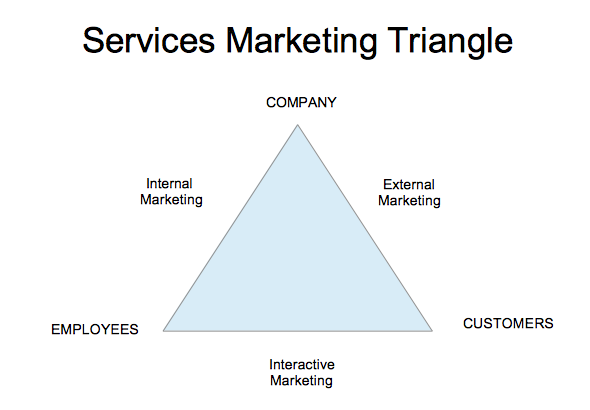

In this way, marketers can be more assured they are strategically satisfying both the customer’s needs and the organization’s objectives (Morrison, 2010). The relationship between company, employees, and customers in the services marketing context can be described as a services marketing triangle (Morrison, 2010), which is illustrated in Figure 8.5.

In traditional marketing, a business broadcasts messaging directly to the consumer. In contrast, in services marketing, employees play an integral component. The communications between the three groups can be summarized as follows (Morrison, 2010):

- External marketing: promotional efforts aimed at potential customers and guests (creating a promise between the organization and the guest)

- Internal marketing: training, culture, and internal communications (enabling employees to deliver on the promise)

- Interactive marketing: direct exchanges between employees and guests (delivering the promise)

The direct and indirect ways that a company or destination reaches its potential customers or guests can be grouped into eight concepts known as the 8 Ps of services marketing .

8 Ps of Services Marketing

The 8 Ps are best described as the specific components required to reach selected markets. In traditional marketing, there are four Ps: price, product, place, and promotion. In services marketing, the list expands to the following (Morrison, 2010):

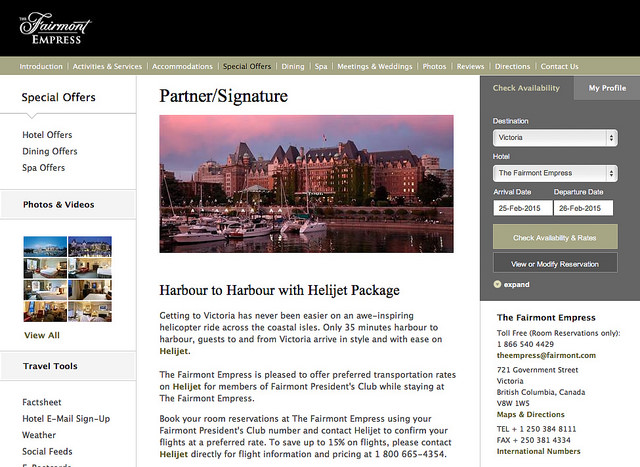

- Product: the range of product and service mix offered to customers

- Place: how the product will be made available to consumers in the market, selection of distribution channels, and partners

- Promotion: specific combination of marketing techniques (advertising, personal sales, public relations, etc.)

- Pricing: part of a comprehensive revenue management and pricing plan

- People: developing human resources plans and strategies to support positive interactions between hosts and guests

- Programming: customer-oriented activities (special events, festivals, or special activities) designed to increase customer spending or length of stay, or to add to the appeal of packages

- Partnership: also known as cooperative marketing, increasing the reach and impact of marketing efforts

- Physical evidence: ways in which businesses can demonstrate their marketing claims and customers can document their experience such as stories, reviews, blog posts, or in-location signage and components

It’s important that these components all work together in a seamless set of messages and activities known as integrated marketing communications, or IMC, to ensure the guests receive a clear message and an experience that meets their expectations.

Integrated Marketing Communications

Integrated marketing communications (IMC) involves planning and coordinating all the promotional mix elements (including online and social media components) to be as consistent and mutually supportive as possible. This approach is much superior to using each element separately and independently.

Tour operators, attractions, hotels, and destination marketing organizations will often break down marketing into separate departments, losing the opportunity to ensure each activity is aligned with a common goal. Sometimes a potential visitor or guest is bombarded with messaging about independent destinations within a region, or businesses within a city, rather than one consistent set of messages about the core attributes of that destination.