- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 6, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

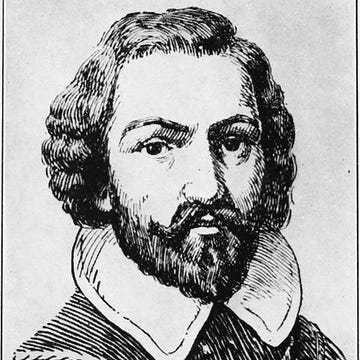

John Cabot (or Giovanni Caboto, as he was known in Italy) was an Italian explorer and navigator who was among the first to think of sailing westward to reach the riches of Asia. Though the details of his life and expeditions are subject to debate, by the late 1490s he was living in England, where he gained a commission from King Henry VII to make an expedition across the Atlantic. He set sail in May 1497 and made landfall in late June, probably in modern-day Canada. After returning to England to report his success, Cabot departed on a final expedition in 1498, but was allegedly never seen again.

Giovanni Caboto was born circa 1450 in Genoa, and moved to Venice around 1461; he became a Venetian citizen in 1476. Evidence suggests that he worked as a merchant in the spice trade of the Levant, or eastern Mediterranean, and may have traveled as far as Mecca, then an important trading center for Oriental and Western goods.

He studied navigation and map-making during this period, and read the stories of Marco Polo and his adventures in the fabulous cities of Asia. Similar to his countryman Christopher Columbus , Cabot appears to have become interested in the possibility of reaching the rich gold, silk, gem and spice markets of Asia by sailing in a westward direction.

Did you know? John Cabot's landing in 1497 is generally thought to be the first European encounter with the North American continent since Leif Eriksson and the Vikings explored the area they called Vinland in the 11th century.

For the next several decades, Cabot’s exact activities are unknown; he may have been forced to leave Venice because of outstanding debts. He then spent several years in Valencia and Seville, Spain, where he worked as a maritime engineer with varying degrees of success.

Cabot may have been in Valencia in 1493, when Columbus passed through the city on his way to report to the Spanish monarchs the results of his voyage (including his mistaken belief that he had in fact reached Asia).

By late 1495, Cabot had reached Bristol, England, a port city that had served as a starting point for several previous expeditions across the North Atlantic. From there, he worked to convince the British crown that England did not have to stand aside while Spain took the lead in exploration of the New World , and that it was possible to reach Asia on a more northerly route than the one Columbus had taken.

First and Second Voyages

In 1496, King Henry VII issued letters patent to Cabot and his son, which authorized them to make a voyage of discovery and to return with goods for sale on the English market. After a first, aborted attempt in 1496, Cabot sailed out of Bristol on the small ship Matthew in May 1497, with a crew of about 18 men.

Cabot’s most successful expedition made landfall in North America on June 24; the exact location is disputed, but may have been southern Labrador, the island of Newfoundland or Cape Breton Island. Reports about their exploration vary, but when Cabot and his men went ashore, he reportedly saw signs of habitation but few if any people. He took possession of the land for King Henry, but hoisted both the English and Venetian flags.

Grand Banks

Cabot explored the area and named various features of the region, including Cape Discovery, Island of St. John, St. George’s Cape, Trinity Islands and England’s Cape. These may correspond to modern-day places located around what became known as Cabot Strait, the 60-mile-wide channel running between southwestern Newfoundland and northern Cape Breton Island.

Like Columbus, Cabot believed that he had reached Asia’s northeast coast. He returned to Bristol in August 1497 with extremely favorable reports of the exploration. Among his discoveries was the rich fishing grounds of the Grand Banks off the coast of Canada, where his crew was allegedly able to fill baskets with cod by simply dropping the baskets into the water.

John Cabot’s Final Voyage

In London in late 1497, Cabot proposed to King Henry VII that he set out on another expedition across the north Atlantic. This time, he would continue westward from his first landfall until he reached the island of Cipangu ( Japan ). In February 1498, the king issued letters patent for the second voyage, and that May Cabot set off once again from Bristol, but this time with five ships and about 300 men.

The exact fate of the expedition has not been established, but by July one of the ships had been damaged and sought anchorage in Ireland. Reportedly the other four ships continued westward. It was believed that the ships had been caught in a severe storm, and by 1499, Cabot himself was presumed to have perished at sea.

Some evidence, however, suggests that Cabot and some members of his crew may have stayed in the New World; other documents suggest that he and his crew returned to England at some point. A Spanish map from 1500 includes the northern coast of North America with English place names and the notation “the sea discovered by the English.”

What Did John Cabot Discover?

In addition to laying the groundwork for British land claims in Canada, his expeditions proved the existence of a shorter route across the northern Atlantic Ocean, which would later facilitate the establishment of other British colonies in North America .

One of John Cabot's sons, Sebastian, was also an explorer who sailed under the flags of England and Spain.

John Cabot. Royal Museums Greenwich . Who Was John Cabot? John Cabot University . John Cabot. The Canadian Encyclopedia .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Explorer John Cabot made a British claim to land in Canada, mistaking it for Asia, during his 1497 voyage on the ship Matthew.

(1450-1500)

Who Was John Cabot?

John Cabot was a Venetian explorer and navigator known for his 1497 voyage to North America, where he claimed land in Canada for England. After setting sail in May 1498 for a return voyage to North America, he disappeared and Cabot's final days remain a mystery.

Cabot was born Giovanni Caboto around 1450 in Genoa, Italy. Cabot was the son of a spice merchant, Giulio Caboto. At age 11, the family moved from Genoa to Venice, where Cabot learned sailing and navigation from Italian seamen and merchants.

Discoveries

In 1497, Cabot traveled by sea from Bristol to Canada, which he mistook for Asia. Cabot made a claim to the North American land for King Henry VII of England , setting the course for England's rise to power in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Cabot’s Route

Like Columbus, Cabot believed that sailing west from Europe was the shorter route to Asia. Hearing of opportunities in England, Cabot traveled there and met with King Henry VII, who gave him a grant to "seeke out, discover, and finde" new lands for England. In early May of 1497, Cabot left Bristol, England, on the Matthew , a fast and able ship weighing 50 tons, with a crew of 18 men. Cabot and his crew sailed west and north, under Cabot's belief that the route to Asia would be shorter from northern Europe than Columbus's voyage along the trade winds. On June 24, 1497, 50 days into the voyage, Cabot landed on the east coast of North America.

The precise location of Cabot’s landing is subject to controversy. Some historians believe that Cabot landed at Cape Breton Island or mainland Nova Scotia. Others believe he may have landed at Newfoundland, Labrador or even Maine. Though the Matthew 's logs are incomplete, it is believed that Cabot went ashore with a small party and claimed the land for the King of England.

In July 1497, the ship sailed for England and arrived in Bristol on August 6, 1497. Cabot was soon rewarded with a pension of £20 and the gratitude of King Henry VII.

Wife and Kids

In 1474, Cabot married a young woman named Mattea. The couple had three sons: Ludovico, Sancto and Sebastiano. Sebastiano would later follow in his father’s footsteps, becoming an explorer in his own right.

Death and Legacy

It is believed Cabot died sometime in 1499 or 1500, but his fate remains a mystery. In February 1498, Cabot was given permission to make a new voyage to North America; in May of that year, he departed from Bristol, England, with five ships and a crew of 300 men. The ships carried ample provisions and small samplings of cloth, lace points and other "trifles," suggesting an expectation of fostering trade with Indigenous peoples. En route, one ship became disabled and sailed to Ireland, while the other four ships continued on. From this point, there is only speculation as to the fate of the voyage and Cabot.

For many years, it was believed that the ships were lost at sea. More recently, however, documents have emerged that place Cabot in England in 1500, laying speculation that he and his crew actually survived the voyage. Historians have also found evidence to suggest that Cabot's expedition explored the eastern Canadian coast, and that a priest accompanying the expedition might have established a Christian settlement in Newfoundland.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: John Cabot

- Birth Year: 1450

- Birth City: Genoa

- Birth Country: Italy

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Explorer John Cabot made a British claim to land in Canada, mistaking it for Asia, during his 1497 voyage on the ship Matthew.

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- John Cabot was inspired by the discoveries of Bartolomeu Dias and Christopher Columbus.

- Cabot's youngest son also became an explorer in his own right

- Death Year: 1500

- Sayled in this tracte so farre towarde the weste, that the Ilande of Cuba bee on my lefte hande, in manere in the same degree of longitude.

European Explorers

Christopher Columbus

10 Famous Explorers Who Connected the World

Sir Walter Raleigh

Ferdinand Magellan

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo

Leif Eriksson

Vasco da Gama

Bartolomeu Dias

Giovanni da Verrazzano

Jacques Marquette

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

3rd March, 2017

John Cabot and the first English expedition to America

During Tudor times Italian explorer John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto to give him his Italian name) led English ships on voyages of discovery and is credited with prompting transatlantic trade between England and the Americas. In an attempt to find a direct route to the markets of the orient, the Italian seafarer became the first early modern European to discover North America when he claimed Newfoundland for England, mistaking it for Asia.

Who was john cabot.

The son of a spice merchant, Giovanni Caboto (meaning either coastal seaman or ‘big head’, depending on who you ask) was probably born in Genoa in 1450, although he may have been from a Venetian family. At the age of 11, his family moved to Venice where Cabot became a respected member of the community and started learning sailing and navigation from the Italian seamen and merchants. He later married a girl named Mattea (the female version of Matthew) and eventually became the father of three sons: Ludovico, Sancto and Sebastiano. (Following in his father’s footsteps Sebastiano later became an explorer in his own right and went on to the Governor of The Muscovy Company).

In 1476 Cabot officially became a Venetian citizen and, now eligible to engage in maritime trade, began trading in the eastern Mediterranean. It is whilst working as merchant trader that Cabot may have developed the idea of sailing westward to reach the rich markets of Asia. Venetian sources also contain references to Cabot being involved in house building in the city around this time.

By the late 1480s, however, Cabot appears to have gotten into financial trouble and he left Venice as an insolvent debtor. Although little is known about Cabot’s exact activities over the next few years it is believed he travelled to Valencia, where he proposed plans for improvements to the harbour, and Seville, where he was contracted to build a stone bridge over the Guadalquivir river although the project was later abandoned.

Having continued his studies in map-making and navigation and, inspired by the discoveries of Bartolomeu Dias and Christopher Columbus, Cabot attempted and failed to persuade the royal courts of Europe to pay for a planned voyage west across the Atlantic. Still expecting to reach China, his idea was to depart to the west from a northerly latitude where the longitudes are much closer together on a shorter, alternative route.

After hearing of opportunities in England, Cabot and his family arrived there around 1495 to seek funding and political support for his planned voyage. Cabot immediately set about trying to persuade merchants in the major maritime centres of London and Bristol (the second-largest seaport in England and the only to have served as a point for previous English Atlantic expeditions) to help.

Cabot receives a royal commission

In Tudor times Cathay and Cipangu (China and Japan) were believed to be rich in silks, spices, gold and gems. If Cabot’s predictions about a new route were right and Asia was where Cabot thought it was, then the whole country stood to profit as it would have made England the greatest trading centre in the world for goods from the east. On 5 March 1496 Tudor King Henry VII issued letters patent to John Cabot and his sons, authorising them to explore unknown lands, with the following charge:

‘Be it known and made manifest that we have given and granted…to our beloved John Cabot, citizen of Venice…free authority, faculty and power to sail to all parts, regions and coasts of the eastern, western and northern sea, under our banners, flags and ensigns, with five ships or vessels of whatsoever burden and quality they may be, and with so many and with such mariners and men as they may wish to take with them in the said ships, at their own proper costs and charges, to find, discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of heathens and infidels, in whatsoever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians.’

After a first, aborted, attempt, Cabot sailed out of Bristol on a small 70-foot long ship named Matthew in May 1497 with a crew of 18 men, sailing past Ireland and across the Atlantic. On 24 June 1497 Cabot sighted land and called it ‘New-found-land’, believing it to be Asia and claiming it in the name of King Henry VII. Although the logs for Matthew are incomplete, it is believed that John Cabot went ashore with a small party. The exact location of the landfall has long been disputed, but most believe it to be one of the northern capes of modern-day Newfoundland off the coast of Canada. Only remaining on land long enough to claim the land and fetch some fresh water, the crew did not meet any natives during their brief visit but apparently they came across some tools, nets and the remnants of a fire and were able to catch huge numbers of cod just by lowering baskets into the seawater.

In the following weeks Cabot and his crew continued to explore and chart the Canadian coastline, before turning back and sailing for England in July.

Matthew and its crew arrived back in Bristol on 6 August 1497 to the welcome of church bells ringing out across the harbour. Cabot then rode to London to report to the King, where he was initially rewarded with the sum of £10 (equivalent to around two years’ pay for an ordinary labourer or craftsman) for discovering a new island off the coast of China – had Cabot brought back some spices then the king may have been more generous. At that point the king’s attention was increasingly being occupied by the Cornish Uprising led by Perkin Warbeck. Once his throne was secure, the king gave more thought to Cabot, who was already planning his next expedition. In September the King made an award of £2 to Cabot, followed by a pension of £20 a year in the December. The following February Cabot was given new letters patent for the voyage and to help him prepare for a second expedition.

In May 1498 Cabot set out with a fleet of four or five ships and 300 men aiming to discover Japan. Carrying ample provisions for a year’s worth of sailing, the fate of the expedition is uncertain as there is no further record of Cabot and his crews, except for one storm-damaged ship which is believed to have sought anchorage in Ireland. It is most widely thought that either the expedition perished at sea or that Cabot eventually reached North America but was unable to make the return voyage across the Atlantic.

You might also be interested in:

- What was Captain Cook looking for when he crossed the Antarctic Circle in 1773?

- Everest revealed

- The royal bed of Henry VII & Elizabeth of York

Books you might like

Young, Brave and Beautiful

Tania Szabó ,

Wherever the Firing Line Extends

Ronan McGreevy , President Mary McAleese (Foreword) ,

William and Mary

John van der Kiste ,

The Yorkshire Colouring Book: Past and Present

Where Madness Lies

Lyndsy Spence ,

Yorkshire in Old Photographs

Dave Randle ,

William John Wills

The War in the Peninsula and Recollections of the Storming of the Castle of Badajos

Lieutenant Robert Knowles , Captain MacCarthy , Ian Fletcher ,

To Complete the Jigsaw

Nicholas van der Bijl ,

Travels in the Interior of Africa

Mungo Park ,

War Hammers

Brian Belton ,

Vikings of the Irish Sea

David Griffiths ,

Voices of Dukinfield and Stalybridge

Derek J Southall ,

To the End, They Remain

Raymond Clark ,

Voices of Ashton Under Lyne

Victor Lustig

Christopher Sandford ,

Twenty-Thousand Miles in a Flying Boat

Sir Alan Cobham , Colin Cruddas ,

The Wagners of Brighton

Sir Anthony Wagner , Antony Dale ,

West Country Murders

Nicola Sly , John van der Kiste , Simon Dell MBE QCB (Foreword) ,

Spitfire’s Forgotten Designer

Mike Roussel , Captain Eric Brown CBE DSC AFC QCVSA RN (Foreword) ,

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up to our monthly newsletter for the latest updates on new titles, articles, special offers, events and giveaways.

© 2024 The History Press

Website by Bookswarm

Find out how Cabot helped kick-start England's transatlantic voyages of discovery

Italian explorer, John Cabot, is famed for discovering Newfoundland and was instrumental in the development of the transatlantic trade between England and the Americas.

Although not born in England, John Cabot led English ships on voyages of discovery in Tudor times. John Cabot (about 1450–98) was an experienced Italian seafarer who came to live in England during the reign of Henry VII. In 1497 he sailed west from Bristol hoping to find a shorter route to Asia, a land believed to be rich in gold, spices and other luxuries. After a month, he discovered a 'new found land', today known as Newfoundland in Canada. Cabot is credited for claiming North America for England and kick-starting a century of English transatlantic exploration.

Why did Cabot come to England?

Born in Genoa around 1450, Cabot's Italian name was Giovanni Caboto. He had read of fabulous Chinese cities in the writings of Marco Polo and wanted to see them for himself. He hoped to reach them by sailing west, across the Atlantic.

Like Christopher Columbus, Cabot found it very difficult to convince backers to pay for the ships he needed to test out his ideas about the world. After failing to persuade the royal courts of Europe, he arrived with his family in 1484, to try to persuade merchants in London and Bristol to pay for his planned voyage. Before he set off, Cabot heard that Columbus had sailed west across the Atlantic and reached land. At the time, everyone believed that this land was the Indies, or Spice Islands.

Why did King Henry VII agree to help to pay for Cabot's expedition?

If Cabot’s predictions about the new route were right, he wouldn’t be the only one to profit. King Henry VII would also take his share. Everybody believed that Cathay and Cipangu (China and Japan) were rich in gold, gems, spices and silks. If Asia had been where Cabot thought it was, it would have made England the greatest trading centre in the world for goods from the east.

What did Cabot find on his voyage?

John Cabot's ship, the Matthew , sailed from Bristol with a crew of 18 in 1497. After a month at sea, he landed and took the area in the name of King Henry VII. Cabot had reached one of the northern capes of Newfoundland. His sailors were able to catch huge numbers of cod simply by dipping baskets into the water. Cabot was rewarded with the sum of £10 by the king, for discovering a new island off the coast of China! The king would’ve been far more generous if Cabot had brought home spices.

What happened to Cabot?

In 1498, Cabot was given permission by Henry VII to take ships on a new expedition to continue west from Newfoundland. The aim was to discover Japan. Cabot set out from Bristol with 300 men in May 1498. The five ships carried supplies for a year's travelling. There is no further record of Cabot and his crews, though there is now some evidence he may have returned and died in England. His son, Sebastian (1474–1577), followed in his footsteps, exploring various parts of the world for England and Spain.

View a replica of John Cabot's ship, which is open to the public in Bristol

Gifts inspired by seafaring in the Tudor and Stuart eras

Learn more about the emergence of a maritime nation

World History Edu

- Famous Explorers

John Cabot: History and Major Accomplishment of the Renowned Italian Explorer

by World History Edu · February 6, 2024

John Cabot, born Giovanni Caboto around 1450 in Genoa, Italy, was an Italian explorer and navigator known for his voyages across the Atlantic Ocean under the commission of Henry VII of England. This exploration led to the European discovery of parts of North America, believed to be the earliest since the Norse visits to Vinland in the eleventh century.

John Cabot, for example, was an Italian explorer known for his 1497 voyage to North America, where, though mistaking the land for Asia, he reached Newfoundland. Cabot is thought to have died only a few years later, possibly on a similar voyage. Image: A painting of Cabot by Italian painter Giustino Menescardi.

This is the story of the famed Italian explorer.

Birth and Early Life

His exact birth date is uncertain, but he is thought to have been born to a spice merchant, Giulio Caboto, and his wife; this background likely instilled in Cabot a curiosity about foreign lands and the lucrative spice trade.

Cabot’s early life is shrouded in mystery, but it is believed that he received a decent education, likely in navigation and seamanship, given Genoa’s prominence as a maritime republic.

By the late 1470s, Cabot had moved to Venice, a leading maritime power with extensive trade networks, where he became a citizen in 1476. During his time in Venice, he likely engaged in trade in the Eastern Mediterranean, gaining invaluable experience and knowledge about the trade routes.

Who were the 10 Most Influential Explorers of the Age of Discovery?

Time in England

By the 1480s, Cabot had moved to Spain and later to England, where he settled in Bristol, a leading maritime center. Bristol merchants had been interested in finding a direct trade route to Asia by sailing westward, and Cabot proposed that by sailing across the North Atlantic, one could reach Asia quicker and more safely than by the traditional routes around Africa.

Newfoundland Arrival

In 1496, Cabot received a royal patent from King Henry VII, which authorized him to search for unknown lands to establish trade. This patent was a significant milestone, as it marked England’s entry into the era of transatlantic exploration. The following year, Cabot set sail with one ship, the Matthew, and a crew of about 20 men. The exact course of his 1497 voyage is the subject of much debate, but it is widely accepted that he landed on the coast of what is today known as Newfoundland or Cape Breton Island, claiming the land for the English crown.

Significance of Cabot’s voyage

Cabot’s 1497 voyage was significant for several reasons. Firstly, it is believed to have been the first European exploration of the North American mainland since the Norse. Secondly, it laid the groundwork for future English claims in North America, which would eventually lead to the establishment of English colonies in the New World.

Despite the historical significance of his 1497 voyage, details about Cabot’s life and subsequent expeditions remain scarce and sometimes contradictory. A second expedition is believed to have taken place in 1498, with Cabot commanding a larger fleet aimed at establishing a base in the New World and further exploring the coast. However, the fate of this expedition is unclear, with some accounts suggesting that Cabot and his fleet were lost at sea, while others propose that he returned to England but fell out of favor.

Did you know…?

- Giovanni Caboto, known as John Cabot in English, reflects a historical European practice of adapting names to local languages in documents, a tradition often embraced by individuals themselves, leading to variations like Zuan Caboto in Venetian and Jean Cabot in French.

- In Venice, Cabot used “Zuan Chabotto,” a local form of John. He maintained this version in England among Italians, while his Italian banker in London uniquely referred to him as “Giovanni” in contemporary documents.

- For the 500th anniversary of Cabot’s expedition, Cape Bonavista, Newfoundland was officially recognized by Canada and the UK as his first landing site, despite other proposed locations for his historic North American arrival.

Cabot’s legacy is complex; while he did not establish lasting European settlements in North America, his voyages opened the North Atlantic and contributed to the European understanding of the New World’s geography. His expeditions under the English flag were among the first steps in the long process that eventually led to the establishment of British North America.

In the centuries following Cabot’s voyages, his achievements were somewhat overshadowed by those of other explorers such as Christopher Columbus and Vasco da Gama .

However, the 19th and 20th centuries saw a resurgence of interest in Cabot as historians and scholars began to recognize his contributions to the Age of Discovery.

Today, John Cabot is celebrated as a pioneering figure in Atlantic exploration, with monuments, geographical locations, and institutions named in his honor, reflecting the enduring impact of his voyages on the history of exploration and the eventual shaping of the modern world.

Most Famous Explorers of All Time

Frequently Asked Questions about John Cabot and his Voyages

These FAQs aim to provide a brief overview of some of the most common questions related to John Cabot and his exploratory voyages to North America.

When was John Cabot born?

Cabot’s birth might predate the commonly cited year of 1450, suggesting an earlier timeline. His 1471 admission into Venice’s esteemed Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista indicates his early respect and standing within the community, reflecting his societal position.

Why was Vasco da Gama determined to open trade route to the east?

Who were john cabot’s parents.

Cabot, son of Giulio Caboto, with a brother named Piero, had his birthplace debated between Gaeta, Province of Latina, and Castiglione Chiavarese, Province of Genoa, Italy.

John Cabot, originally Giovanni Caboto, was an Italian navigator and explorer who is credited with the discovery of parts of North America under the commission of Henry VII of England in 1497.

What did John Cabot discover?

John Cabot is best known for his 1497 voyage across the Atlantic Ocean, where he reached what is believed to be the coast of Newfoundland, thus marking one of the earliest European explorations of the North American continent since the Norse.

Why did John Cabot explore?

Cabot was motivated by the desire to find a westward route to Asia to access its lucrative spice trade, bypassing the overland routes that were controlled by the Ottomans.

Was John Cabot the first to discover North America?

No, Cabot was not the first. The Norse, led by Leif Eriksson, had reached North America, specifically Vinland, which is thought to be modern-day Newfoundland, around the year 1000. However, Cabot’s voyage in 1497 is significant as it led to the European rediscovery of the continent.

Who was Barentsz and how significant was his exploration of the Arctic?

Did john cabot think he had found asia.

Yes, like many explorers of his time, Cabot believed that the lands he had found were the eastern outskirts of Asia. The concept of the “New World” as separate continents of North and South America was not widely recognized at the time.

What happened to John Cabot after his voyages?

The details surrounding Cabot’s fate after his voyages are unclear and subject to debate. He is believed to have embarked on a second voyage in 1498, from which he may not have returned, possibly dying during this expedition.

Cabot’s voyages were significant because they were among the first to suggest the existence of a northwestern route to Asia and they laid the groundwork for future European exploration and eventual colonization of the Americas. Image: Sculpture of Giovanni Caboto, crafted by Italian artits Augusto Benvenuti in 1881.

Did John Cabot have any interaction with indigenous peoples?

There is no conclusive evidence that Cabot directly interacted with indigenous peoples during his voyages. The records of his 1497 voyage are sparse, and if there were interactions, they were not well-documented.

What flag did John Cabot sail under?

John Cabot sailed under the flag of England, having been granted a royal patent by King Henry VII, which authorized him to explore “new lands” on behalf of the English crown.

Tags: 15th Century Explorers Age of Discovery Canada Henry VII of England Italian explorers John Cabot Newfoundland North America

You may also like...

Who was the Chinese Admiral Zheng He?

February 16, 2024

February 9, 2024

February 3, 2024

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Next story The birth of the Gorgons according to Hesiod’s Theogony

- Previous story What transpired at the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403?

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

History of Lee Kuan Yew and how he put Singapore on the path of rapid economic growth

What triggered the Hundred Years’ War?

History and Major Facts about London Wall

8 Major Cities Founded by the Romans

Why did the Greeks defeat Persia, but the Romans failed?

Greatest African Leaders of all Time

Queen Elizabeth II: 10 Major Achievements

Donald Trump’s Educational Background

Donald Trump: 10 Most Significant Achievements

8 Most Important Achievements of John F. Kennedy

Odin in Norse Mythology: Origin Story, Meaning and Symbols

Ragnar Lothbrok – History, Facts & Legendary Achievements

9 Great Achievements of Queen Victoria

12 Most Influential Presidents of the United States

Most Ruthless African Dictators of All Time

Kwame Nkrumah: History, Major Facts & 10 Memorable Achievements

Greek God Hermes: Myths, Powers and Early Portrayals

8 Major Achievements of Rosa Parks

How did Captain James Cook die?

10 Most Famous Pharaohs of Egypt

Kamala Harris: 10 Major Achievements

The Exact Relationship between Elizabeth II and Elizabeth I

Poseidon: Myths and Facts about the Greek God of the Sea

Nile River: Location, Importance & Major Facts

Importance and Major Facts about Magna Carta

- Adolf Hitler Alexander the Great American Civil War Ancient Egyptian gods Ancient Egyptian religion Aphrodite Apollo Athena Athens Black history Carthage China Civil Rights Movement Constantine the Great Constantinople Egypt England France Germany Ghana Hera Horus India Isis John Adams Julius Caesar Loki Military Generals Military History Nobel Peace Prize Odin Osiris Pan-Africanism Queen Elizabeth I Ra Ragnarök Religion Set (Seth) Soviet Union Thor Timeline Women’s History World War I World War II Zeus

- Inventors and Inventions

- Philosophers

- Film, TV, Theatre - Actors and Originators

- Playwrights

- Advertising

- Military History

- Politicians

- Publications

- Visual Arts

John Cabot - North American Trail-blazer

Contribution to British Heritage.

Legacy and Success

General information.

- John Cabot en.wikipedia.org

You might also like

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot)

Introduction, general overviews.

- Encyclopedia Entries

- Birth and Early Life

- The 1496 Voyage

- The 1497 Voyage

- The 1498 Voyage

- Funding of Voyages

- Sebastiano Caboto, Son (d. 1557)

- Maps and Cartography

- Early English Voyages (pre-Caboto)

- Later English Voyages (post-Caboto)

- Internet Resources

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Maps in the Atlantic World

- Pre-Columbian Transatlantic Voyages

- Tudor and Stuart Britain in the Wider World, 1485–1685

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- European Enslavement of Indigenous People in the Americas

- Nobility and Gentry in the Early Modern Atlantic World

- Phillis Wheatley

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot) by Francesco Guidi Bruscoli LAST MODIFIED: 29 November 2022 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199730414-0374

Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot, b. c. 1450–d. c . 1500) was an Italian navigator credited to be the first European to set foot in North America after the Norse, during an expedition of 1497 carried out under the English flag. Little is known about his origins, although he certainly took up Venetian citizenship, implying origin elsewhere. He was known as Zuan Chabotto in Venice, and he presented himself as a Venetian when he moved to England. As early as the late sixteenth/early seventeenth century, Richard Hakluyt and Samuel Purchas praised Caboto’s pioneering “discoveries” (despite some confusion between the role of Giovanni and that of his son). But it was especially from 1897 (the 400th anniversary of his landing) that—following new archival discoveries—his achievement as an explorer was celebrated. Until then his role had been overshadowed by that of his son Sebastian, who in part because of the influence of Sebastian’s own accounts, had been credited with being in charge of the voyages. It was in particular Henry Harrisse, in John Cabot, the Discoverer of North America, and Sebastian his Son: A Chapter of the Maritime History of England under the Tudors, 1496–1557 (London: Stevens, 1896), who revived the figure of Giovanni, while at the same time lambasting Sebastiano as an impostor. In the same period, more or less co-incident with the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s 1492 voyage, general interest in voyages of exploration revived also in Italy, although studies on Caboto mainly focused on his origin. In the 1940s new documentary discoveries threw some light on Caboto’s years both in Spain and in Venice. In the 1950s the discovery of John Day’s letter in the Simancas archive stimulated a new wave of studies, for the letter hints at a previously unknown voyage of 1496, provides many technical details concerning the 1497 voyage (thus opening debate on the latitude of the landing), and alludes to earlier discoveries. The most important study, still a crucial reference for studies on Caboto, is James A. Williamson’s The Cabot Voyages and Bristol Discovery under Henry VII (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press/Hakluyt Society, 2nd Series, vol. 120, 1962). For the 500th anniversary of the landing, in 1997, several conferences were organized, in many cases leading to the publication of proceedings. The most relevant recent advances, however, have been made within the framework of the Cabot Project, based at the University of Bristol. Following unpublished leads left behind by deceased scholar Alwyn Ruddock, Evan Jones and others have proposed new hypotheses, and uncovered the first known financiers of the 1497 voyage.

The volume of literature on Giovanni Caboto is overwhelming. New waves of publications coincided either with the celebration of anniversaries (especially in 1897 and 1997) or with the discovery of new documents, as summarized by Luzzana Caraci 1999 . In Italian the first analytical study of Caboto’s achievements was Almagià 1937 . In English the classic work (still seminal) is Williamson 1962 . Countless scholars and writers have published on Caboto’s voyages before and since. Among the most recent academic publications, Pope 1997 discusses at length the possible landfall of the 1497 voyage, still claimed by various Canadian regions, including Cape Bonavista (Newfoundland) and Cape Breton (Nova Scotia), whereas Jones 2008 sets the agenda for new streams of research to be undertaken in order to substantiate or rebut novel claims made by deceased historian Alwyn Ruddock (d. 2005). Recent popular literature includes Hunter 2011 , which takes a broader approach including Columbus’s voyages, and Jones and Condon 2016 , which summarizes current knowledge and is the prelude to a forthcoming academic publication.

Almagià, Roberto. Gli italiani primi scopritori dell’America . Rome: La Libreria dello Stato, 1937.

Voluminous (and rare) publication in Italian on Italian “first discoverers” of America. Starts from Columbus, and devotes several pages to Caboto. It also includes tables and maps. Critically discusses documents relating to the life and voyages of Caboto (and his son).

Hunter, Douglas. The Race to the New World: Christopher Columbus, John Cabot, and a Lost History of Discovery . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

A popular history book, aimed at comparing the figures, the careers, and the achievements of Christopher Columbus and Giovanni Caboto. Includes the hypothesis (not backed by any documentary evidence) that Caboto might have accompanied Columbus on his second voyage of 1493.

Jones, Evan T. “Alwyn Ruddock: ‘John Cabot and the Discovery of America.’” Historical Research 81 (2008): 224–254.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2281.2007.00422.x

Discusses claims made by late historian Alwyn Ruddock concerning new discoveries relating to Caboto’s voyages. This article originated new archival research aimed at substantiating or clarifying Ruddock’s claims. See also The Cabot Project , cited under Internet Resources .

Jones, Evan T., and M. Condon. Cabot and Bristol’s Age of Discovery: The Bristol Discovery Voyages 1480–1508 . Bristol, UK: University of Bristol, 2016.

Aimed at a general audience, this book presents an updated summary of what we currently know about Caboto and his voyages. It also discusses claims made by the late historian Alwyn Ruddock concerning the discovery of new documents. Also available online .

Luzzana Caraci, Ilaria. “Giovanni Caboto cinquecento anni dopo.” In Giovanni Caboto e le vie dell’Atlantico settentrionale . Atti del Convegno Internazionale (Roma, 29 settembre–1 ottobre 1997). Edited by Marcella Arca Petrucci and Simonetta Conti, 51–68. Rome: CISGE, 1999.

Useful and articulated—albeit brief—summary of the main advancement in the knowledge of Caboto’s life and voyages from the sixteenth century (until 1997).

Pope, Peter. The Many Landfalls of John Cabot . Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997.

DOI: 10.3138/9781442681699

Discusses the current knowledge about Caboto, but also the claims of his son Sebastiano (denying his participation in his father’s voyage). Much space is devoted to the possible landfalls of the 1497 voyage and to the celebrations of 1897 (400th anniversary of the landing), when “anglophone/francophone cultural tensions [and] competition between Canada and Newfoundland” (p. 8) sparked debate on the landfall itself.

Williamson, James A. The Cabot Voyages and Bristol Discovery under Henry VII . Hakluyt Society Works, 2nd Series, Vol. 120. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1962.

Albeit dated, it is still the fundamental reference for sources concerning the voyages of John Cabot, as well as his son Sebastian’s and other Bristol voyages. A long introduction summarizes and compares all the sources and offers a considered narrative. It also includes an Appendix by R.A. Skelton, “The Cartography of the Voyages.” The volume reworks, with new documents added, an earlier study of 1929.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Atlantic History »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abolition of Slavery

- Abolitionism and Africa

- Africa and the Atlantic World

- African American Religions

- African Religion and Culture

- African Retailers and Small Artisans in the Atlantic World

- Age of Atlantic Revolutions, The

- Alexander von Humboldt and Transatlantic Studies

- America, Pre-Contact

- American Revolution, The

- Anti-Catholicism and Anti-Popery

- Army, British

- Art and Artists

- Asia and the Americas and the Iberian Empires

- Atlantic Biographies

- Atlantic Creoles

- Atlantic History and Hemispheric History

- Atlantic Migration

- Atlantic New Orleans: 18th and 19th Centuries

- Atlantic Trade and the British Economy

- Atlantic Trade and the European Economy

- Bacon's Rebellion

- Barbados in the Atlantic World

- Barbary States

- Berbice in the Atlantic World

- Black Atlantic in the Age of Revolutions, The

- Bolívar, Simón

- Borderlands

- Bourbon Reforms in the Spanish Atlantic, The

- Brazil and Africa

- Brazilian Independence

- Britain and Empire, 1685-1730

- British Atlantic Architectures

- British Atlantic World

- Buenos Aires in the Atlantic World

- Cabato, Giovanni (John Cabot)

- Cannibalism

- Captain John Smith

- Captivity in Africa

- Captivity in North America

- Caribbean, The

- Cartier, Jacques

- Catholicism

- Cattle in the Atlantic World

- Central American Independence

- Central Europe and the Atlantic World

- Chartered Companies, British and Dutch

- Chinese Indentured Servitude in the Atlantic World

- Church and Slavery

- Cities and Urbanization in Portuguese America

- Citizenship in the Atlantic World

- Class and Social Structure

- Coastal/Coastwide Trade

- Cod in the Atlantic World

- Colonial Governance in Spanish America

- Colonial Governance in the Atlantic World

- Colonialism and Postcolonialism

- Colonization, Ideologies of

- Colonization of English America

- Communications in the Atlantic World

- Comparative Indigenous History of the Americas

- Confraternities

- Constitutions

- Continental America

- Cook, Captain James

- Cortes of Cádiz

- Cosmopolitanism

- Credit and Debt

- Creek Indians in the Atlantic World, The

- Creolization

- Criminal Transportation in the Atlantic World

- Crowds in the Atlantic World

- Death in the Atlantic World

- Demography of the Atlantic World

- Diaspora, Jewish

- Diaspora, The Acadian

- Disease in the Atlantic World

- Domestic Production and Consumption in the Atlantic World

- Domestic Slave Trades in the Americas

- Dreams and Dreaming

- Dutch Atlantic World

- Dutch Brazil

- Dutch Caribbean and Guianas, The

- Early Modern Amazonia

- Early Modern France

- Economy and Consumption in the Atlantic World

- Economy of British America, The

- Edwards, Jonathan

- Emancipation

- Empire and State Formation

- Enlightenment, The

- Environment and the Natural World

- Europe and Africa

- Europe and the Atlantic World, Northern

- Europe and the Atlantic World, Western

- European, Javanese and African and Indentured Servitude in...

- Evangelicalism and Conversion

- Female Slave Owners

- First Contact and Early Colonization of Brazil

- Fiscal-Military State

- Forts, Fortresses, and Fortifications

- Founding Myths of the Americas

- France and Empire

- France and its Empire in the Indian Ocean

- France and the British Isles from 1640 to 1789

- Free People of Color

- Free Ports in the Atlantic World

- French Army and the Atlantic World, The

- French Atlantic World

- French Emancipation

- French Revolution, The

- Gender in Iberian America

- Gender in North America

- Gender in the Atlantic World

- Gender in the Caribbean

- George Montagu Dunk, Second Earl of Halifax

- Georgia in the Atlantic World

- German Influences in America

- Germans in the Atlantic World

- Giovanni da Verrazzano, Explorer

- Glorious Revolution

- Godparents and Godparenting

- Great Awakening

- Green Atlantic: the Irish in the Atlantic World

- Guianas, The

- Haitian Revolution, The

- Hanoverian Britain

- Havana in the Atlantic World

- Hinterlands of the Atlantic World

- Histories and Historiographies of the Atlantic World

- Hunger and Food Shortages

- Iberian Atlantic World, 1600-1800

- Iberian Empires, 1600-1800

- Iberian Inquisitions

- Idea of Atlantic History, The

- Impact of the French Revolution on the Caribbean, The

- Indentured Servitude

- Indentured Servitude in the Atlantic World, Indian

- India, The Atlantic Ocean and

- Indigenous Knowledge

- Indigo in the Atlantic World

- Internal Slave Migrations in the Americas

- Interracial Marriage in the Atlantic World

- Ireland and the Atlantic World

- Iroquois (Haudenosaunee)

- Islam and the Atlantic World

- Itinerant Traders, Peddlers, and Hawkers

- Jamaica in the Atlantic World

- Jefferson, Thomas

- Jews and Blacks

- Labor Systems

- Land and Propert in the Atlantic World

- Language, State, and Empire

- Languages, Caribbean Creole

- Latin American Independence

- Law and Slavery

- Legal Culture

- Leisure in the British Atlantic World

- Letters and Letter Writing

- Literature and Culture

- Literature of the British Caribbean

- Literature, Slavery and Colonization

- Liverpool in The Atlantic World 1500-1833

- Louverture, Toussaint

- Manumission

- Maritime Atlantic in the Age of Revolutions, The

- Markets in the Atlantic World

- Maroons and Marronage

- Marriage and Family in the Atlantic World

- Material Culture in the Atlantic World

- Material Culture of Slavery in the British Atlantic

- Medicine in the Atlantic World

- Mental Disorder in the Atlantic World

- Mercantilism

- Merchants in the Atlantic World

- Merchants' Networks

- Migrations and Diasporas

- Minas Gerais

- Mining, Gold, and Silver

- Missionaries

- Missionaries, Native American

- Money and Banking in the Atlantic Economy

- Monroe, James

- Morris, Gouverneur

- Music and Music Making

- Napoléon Bonaparte and the Atlantic World

- Nation and Empire in Northern Atlantic History

- Nation, Nationhood, and Nationalism

- Native American Histories in North America

- Native American Networks

- Native American Religions

- Native Americans and Africans

- Native Americans and the American Revolution

- Native Americans and the Atlantic World

- Native Americans in Cities

- Native Americans in Europe

- Native North American Women

- Native Peoples of Brazil

- Natural History

- Networks for Migrations and Mobility

- Networks of Science and Scientists

- New England in the Atlantic World

- New France and Louisiana

- New York City

- Nineteenth-Century Atlantic World

- Nineteenth-Century France

- North Africa and the Atlantic World

- Northern New Spain

- Novel in the Age of Revolution, The

- Oceanic History

- Pacific, The

- Paine, Thomas

- Papacy and the Atlantic World

- People of African Descent in Early Modern Europe

- Pets and Domesticated Animals in the Atlantic World

- Philadelphia

- Philanthropy

- Plantations in the Atlantic World

- Poetry in the British Atlantic

- Political Participation in the Nineteenth Century Atlantic...

- Polygamy and Bigamy

- Port Cities, British

- Port Cities, British American

- Port Cities, French

- Port Cities, French American

- Port Cities, Iberian

- Ports, African

- Portugal and Brazile in the Age of Revolutions

- Portugal, Early Modern

- Portuguese Atlantic World

- Poverty in the Early Modern English Atlantic

- Pregnancy and Reproduction

- Print Culture in the British Atlantic

- Proprietary Colonies

- Protestantism

- Quebec and the Atlantic World, 1760–1867

- Race and Racism

- Race, The Idea of

- Reconstruction, Democracy, and United States Imperialism

- Red Atlantic

- Refugees, Saint-Domingue

- Religion and Colonization

- Religion in the British Civil Wars

- Religious Border-Crossing

- Religious Networks

- Representations of Slavery

- Republicanism

- Rice in the Atlantic World

- Rio de Janeiro

- Russia and North America

- Saint Domingue

- Saint-Louis, Senegal

- Salvador da Bahia

- Scandinavian Chartered Companies

- Science, History of

- Scotland and the Atlantic World

- Sea Creatures in the Atlantic World

- Second-Hand Trade

- Settlement and Region in British America, 1607-1763

- Seven Years' War, The

- Sex and Sexuality in the Atlantic World

- Shakespeare and the Atlantic World

- Ships and Shipping

- Slave Codes

- Slave Names and Naming in the Anglophone Atlantic

- Slave Owners In The British Atlantic

- Slave Rebellions

- Slave Resistance in the Atlantic World

- Slave Trade and Natural Science, The

- Slave Trade, The Atlantic

- Slavery and Empire

- Slavery and Fear

- Slavery and Gender

- Slavery and the Family

- Slavery, Atlantic

- Slavery, Health, and Medicine

- Slavery in Africa

- Slavery in Brazil

- Slavery in British America

- Slavery in British and American Literature

- Slavery in Danish America

- Slavery in Dutch America and the West Indies

- Slavery in New England

- Slavery in North America, The Growth and Decline of

- Slavery in the Cape Colony, South Africa

- Slavery in the French Atlantic World

- Slavery, Native American

- Slavery, Public Memory and Heritage of

- Slavery, The Origins of

- Slavery, Urban

- Sociability in the British Atlantic

- Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts...

- South Atlantic

- South Atlantic Creole Archipelagos

- South Carolina

- Sovereignty and the Law

- Spain, Early Modern

- Spanish America After Independence, 1825-1900

- Spanish American Port Cities

- Spanish Atlantic World

- Spanish Colonization to 1650

- Subjecthood in the Atlantic World

- Sugar in the Atlantic World

- Swedish Atlantic World, The

- Technology, Inventing, and Patenting

- Textiles in the Atlantic World

- Texts, Printing, and the Book

- The American West

- The French Lesser Antilles

- The Fur Trade

- The Spanish Caribbean

- Time(scapes) in the Atlantic World

- Toleration in the Atlantic World

- Transatlantic Political Economy

- Tudor and Stuart Britain in the Wider World, 1485-1685

- Universities

- USA and Empire in the 19th Century

- Venezuela and the Atlantic World

- Visual Art and Representation

- War and Trade

- War of 1812

- War of the Spanish Succession

- Warfare in Spanish America

- Warfare in 17th-Century North America

- Warfare, Medicine, and Disease in the Atlantic World

- West Indian Economic Decline

- Whitefield, George

- Whiteness in the Atlantic World

- William Blackstone

- William Shakespeare, The Tempest (1611)

- William Wilberforce

- Witchcraft in the Atlantic World

- Women and the Law

- Women Prophets

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.159]

- 81.177.182.159

Search The Canadian Encyclopedia

Enter your search term

Why sign up?

Signing up enhances your TCE experience with the ability to save items to your personal reading list, and access the interactive map.

- MLA 8TH EDITION

- Hunter, Douglas . "John Cabot". The Canadian Encyclopedia , 19 May 2017, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot. Accessed 14 April 2024.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , 19 May 2017, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot. Accessed 14 April 2024." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- APA 6TH EDITION

- Hunter, D. (2017). John Cabot. In The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- CHICAGO 17TH EDITION

- Hunter, Douglas . "John Cabot." The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published January 07, 2008; Last Edited May 19, 2017.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published January 07, 2008; Last Edited May 19, 2017." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- TURABIAN 8TH EDITION

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "John Cabot," by Douglas Hunter, Accessed April 14, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "John Cabot," by Douglas Hunter, Accessed April 14, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Article by Douglas Hunter

Published Online January 7, 2008

Last Edited May 19, 2017

Early Years in Venice

John Cabot had a complex and shadowy early life. He was probably born before 1450 in Italy and was awarded Venetian citizenship in 1476, which meant he had been living there for at least fifteen years. People often signed their names in different ways at this time, and Cabot was no exception. In one 1476 document he identified himself as Zuan Chabotto, which gives a clue to his origins. It combined Zuan, the Venetian form for Giovanni, with a family name that suggested an origin somewhere on the Italian peninsula, since a Venetian would have spelled it Caboto. He had a Venetian wife, Mattea, and three sons, one of whom, Sebastian, rose to the rank of pilot-major of Spain for the Indies trade. Cabot was a merchant; Venetian records identify him as a hide trader, and in 1483 he sold a female slave in Crete. He was also a property developer in Venice and nearby Chioggia.

Cabot in Spain

In 1488, Cabot fled Venice with his family because he owed prominent people money. Where the Cabot family initially went is unknown, but by 1490 John Cabot was in Valencia, Spain, which like Venice was a city of canals. In 1492, he partnered with a Basque merchant named Gaspar Rull in a proposal to build an artificial harbour for Valencia on its Mediterranean coast. In April 1492, the project captured the enthusiasm of Fernando (Ferdinand), king of Aragon and husband of Isabel, queen of Castille, who together ruled what is now a unified Spain. The royal couple had just agreed to send Christopher Columbus on his now-famous voyage to the Americas. In the autumn of 1492, Fernando encouraged the governor-general of Valencia to find a way to finance Cabot’s harbour scheme. However, in March 1493, the council of Valencia decided it could not fund Cabot’s plan. Despite Fernando’s attempt to move the project forward that April, the scheme collapsed.

Cabot disappeared from the historical record until June 1494, when he resurfaced in another marine engineering plan dear to the Spanish monarchs. He was hired to build a fixed bridge link in Seville to its maritime centre, the island of Triana in the Guadalquivir River, which otherwise was serviced by a troublesome floating one. Though Columbus had reached the Americas, he believed he had found land on the eastern edge of Asia, and Seville had been chosen as the headquarters of what Spain imagined was a lucrative transatlantic trade route. Cabot’s assignment thus was an important one, but something went wrong. In December 1494, a group of leading citizens of Seville gathered, unhappy with Cabot’s lack of progress, given the funds he had been provided. At least one of them thought he should be banished from the city. By then, Cabot probably had left town.

Cabot in England

Following the demise of Cabot’s Seville bridge project, the marine engineer again disappeared from the historical record. In March 1496 he resurfaced, this time as the commander of a proposed westward voyage under the flag of the King of England, Henry VII. Although there is no documentary proof, during Cabot’s absence from the historical record, between April 1493 and June 1494, he could have sailed with Columbus’s second voyage to the Caribbean. Most of the names of the over 1,000 people who accompanied Columbus weren’t recorded; however, Cabot could have been among the marine engineers on the voyage’s 17 ships who were expected to construct a harbour facility in what is now Haiti. Had Cabot been present on this journey, Henry VII would have had some basis to believe the would-be Venetian explorer could make a similar voyage to the far side of the Atlantic. It would help explain why Henry VII hired Cabot, a foreigner with a problematic résumé and no known nautical expertise, to make such a journey.

On 5 March 1496, Henry awarded Cabot and his three sons a generous letters patent, a document granting them the right to explore and exploit areas unknown to Christian monarchs. The Cabots were authorized to sail to “all parts of the eastern, western and northern sea, under our banners, flags and ensigns,” with as many as five ships, manned and equipped at their own expense. The Cabots were to “find, discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of heathens and infidels, in whatsoever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians.” The Cabots would serve as Henry’s “vassals, and governors lieutenants and deputies” in whatever lands met the criteria of the patent, and they were given the right to “conquer, occupy and possess whatsoever towns, castles, cities and islands by them discovered.” With the letters patent, the Cabots could secure financial backing. Two payments were made in April and May 1496 to John Cabot by the House of Bardi (a family of Florentine merchants) to fund his search for “the new land,” suggesting his investors thought he was looking for more than a northern trade route to Asia.

First Voyage (1496)

Cabot’s first voyage departed Bristol, England, in 1496. Sailing westward in the north Atlantic was no easy task. The prevailing weather patterns track from west to east, and ships of Cabot’s time could scarcely sail toward the wind. No first-hand accounts of Cabot’s first attempt to sail west survive. Historians only know that it was a failure, with Cabot apparently rebuffed by stormy weather.

Second Voyage (1497)

Cabot mounted a second attempt from Bristol in May 1497, using a ship called the Matthew . It may have been a happy coincidence that its name was the English version of Cabot’s wife’s name, Mattea. There are no records of the ship’s individual crewmembers, and all the accounts of the voyage are second-hand — a remarkable lack of documentation for a voyage that would be the foundation of England’s claim to North America.

Historians have long debated exactly where Cabot explored. The most authoritative report of his journey was a letter by a London merchant named Hugh Say. Written in the winter of 1497-98, but only discovered in Spanish archives in the mid-1950s, Say’s letter (written in Spanish) was addressed to a “great admiral” in Spain who may have been Columbus.

The rough latitudes Say provided suggest Cabot made landfall around southern Labrador and northernmost Newfoundland , then worked his way southeast along the coast until he reached the Avalon Peninsula , at which point he began the journey home. Cabot led a fearful crew, with reports suggesting they never ventured more than a crossbow’s shot into the land. They saw two running figures in the woods that might have been human or animal and brought back an unstrung bow “painted with brazil,” suggesting it was decorated with red ochre by the Beothuk of Newfoundland or the Innu of Labrador. He also brought back a snare for capturing game and a needle for making nets. Cabot thought (wrongly) there might be tilled lands, written in Say’s letter as tierras labradas , which may have been the source of the name for Labrador. Say also said it was certain the land Cabot coasted was Brasil, a fabled island thought to exist somewhere west of Ireland.

Others who heard about Cabot’s voyage suggested he saw two islands, a misconception possibly resulting from the deep indentations of Newfoundland’s Conception and Trinity Bays, and arrived at the coast of East Asia. Some believed he had reached another fabled island, the Isle of Seven Cities, thought to exist in the Atlantic.

There were also reports Cabot had found an enormous new fishery. In December 1497, the Milanese ambassador to England reported hearing Cabot assert the sea was “swarming with fish, which can be taken not only with the net, but in baskets let down with a stone.” The fish of course were cod , and their abundance on the Grand Banks later laid the foundation for Newfoundland’s fishing industry.

Third Voyage (1498)

Henry VII rewarded Cabot with a royal pension on December 1497 and a renewed letters patent in February 1498 that gave him additional rights to help mount the next voyage. The additional rights included the ability to charter up to six ships as large as 200 tons. The voyage was again supposed to be mounted at Cabot’s expense, although the king personally invested in one participating ship. Despite reports from the 1497 voyage of masses of fish, no preparations were made to harvest them.

A flotilla of probably five ships sailed in early May. What became of it remains a mystery. Historians long presumed, based on a flawed account by the chronicler Polydore Vergil, that all the ships were lost, but at least one must have returned. A map made by Spanish cartographer Juan de la Cosa in 1500 — one of the earliest European maps to incorporate the Americas — included details of the coastline with English place names, flags and the notation “the sea discovered by the English.” The map suggests Cabot’s voyage ventured perhaps as far south as modern New England and Long Island.

Cabot’s royal pension did continue to be paid until 1499, but if he was lost on the 1498 voyage, it may only have been collected in his absence by one of his sons, or his widow, Mattea.

Despite being so poorly documented, Cabot’s 1497 voyage became the basis of English claims to North America. At the time, the westward voyages of exploration out of Bristol between 1496 and about 1506, as well as one by Sebastian Cabot around 1508, were probably considered failures. Their purpose was to secure trade opportunities with Asia, not new fishing grounds, which not even Cabot was interested in, despite praising the teeming schools. Instead of trade with Asia, Cabot and his Bristol successors found an enormous land mass blocking the way and no obvious source of wealth.

- Newfoundland and Labrador

Further Reading

Douglas Hunter, The Race to the New World: Christopher Columbus, John Cabot and a Lost History of Discovery (2012).

External Links

Heritage Newfoundland and Labrador A biography of John Cabot from this site sponsored by Memorial University.

Dictionary of Canadian Biography An account of John Cabot’s life from the Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

Recommended

Giovanni da verrazzano, jacques cartier.

Sir Humphrey Gilbert: Elizabethan Explorer

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Native Americans

- Age of Exploration

- Revolutionary War

- Mexican-American War

- War of 1812

- World War 1

- World War 2

- Family Trees

- Explorers and Pirates

John Cabot Facts, Voyage, and Accomplishments

Published: Jul 25, 2016 · Modified: Nov 11, 2023 by Russell Yost · This post may contain affiliate links ·

John Cabot was a Genoese navigator and explorer whose 1497 discovery of parts of North America under the commission of Henry VII of England is commonly held to have been the first European exploration of the mainland of North America since the Norse Vikings' visits to Vinland in the eleventh century.

It would also be one of the last times, until Queen Elizabeth, that England would set foot in the New World.

John Cabot Facts: Early Life

John cabot facts: england and expeditions, john cabot facts: historical thoughts, online resources.

He may have been born slightly earlier than 1450, which is the approximate date most commonly given for his birth.

In 1471, Caboto was accepted into the religious confraternity of St John the Evangelist. Since this was one of the city's prestigious confraternities, his acceptance suggests that he was already a respected member of the community.

Following his gaining full Venetian citizenship in 1476, Caboto would have been eligible to engage in maritime trade, including the trade to the eastern Mediterranean that was the source of much of Venice's wealth.

A 1483 document refers to his selling a slave in Crete whom he had acquired while in the territories of the Sultan of Egypt, which then comprised most of what is now Palestine, Syria, and Lebanon.

Cabot is mentioned in many Venetian records of the 1480s. These indicate that by 1484, he was married to Mattea and already had at least two sons.

Cabot's sons are Ludovico, Sebastian, and Sancto. The Venetian sources contain references to Cabot's being involved in house building in the city. He may have relied on this experience when seeking work later in Spain as a civil engineer.

Cabot appears to have gotten into financial trouble in the late 1480s and left Venice as an insolvent debtor by 5 November 1488.

He moved to Valencia, Spain, where his creditors attempted to have him arrested. While in Valencia, John Cabot proposed plans for improvements to the harbor. These proposals were rejected.

Early in 1494, he moved on to Seville, where he proposed, was contracted to build, and, for five months, worked on the construction of a stone bridge over the Guadalquivir River. This project was abandoned following a decision of the City Council on 24 December 1494.

After this, Cabot appears to have sought support from the Iberian crowns of Seville and Lisbon for an Atlantic expedition before moving to London to seek funding and political support. He likely reached England in mid-1495.

Like other Italian explorers, including Christopher Columbus , Cabot led an expedition on commission to another European nation, in his case, England.

Cabot planned to depart to the west from a northerly latitude where the longitudes are much closer together and where, as a result, the voyage would be much shorter. He still had an expectation of finding an alternative route to China.

On 5 March 1496, Henry VII gave Cabot and his three sons letters patent with the following charge for exploration:

...free authority, faculty, and power to sail to all parts, regions, and coasts of the eastern, western, and northern sea, under our banners, flags, and ensigns, with five ships or vessels of whatsoever burden and quality they may be, and with so many and with such mariners and men as they may wish to take with them in the said ships, at their own proper costs and charges, to find, discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of heathens and infidels, in whatsoever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians.

Those who received such patents had the right to assign them to third parties for execution. His sons are believed to have still been under the age of 18

Cabot went to Bristol to arrange preparations for his voyage. Bristol was the second-largest seaport in England. From 1480 onward, it supplied several expeditions to look for Hy-Brazil. According to Celtic legend, this island lay somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean. There was a widespread belief among merchants in the port that Bristol men had discovered the island at an earlier date but then lost track of it.

Cabot's first voyage was little recorded. Winter 1497/98 letter from John Day (a Bristol merchant) to an addressee believed to be Christopher Columbus refers briefly to it but writes mostly about the second 1497 voyage. He notes, "Since your Lordship wants information relating to the first voyage, here is what happened: he went with one ship, his crew confused him, he was short of supplies and ran into bad weather, and he decided to turn back." Since Cabot received his royal patent in March 1496, it is believed that he made his first voyage that summer.

What is known as the "John Day letter" provides considerable information about Cabot's second voyage. It was written during the winter of 1497/8 by Bristol merchant John Day to a man who is likely Christopher Columbus . Day is believed to have been familiar with the key figures of the expedition and thus able to report on it.

If the lands Cabot had discovered lay west of the meridian laid down in the Treaty of Tordesillas, or if he intended to sail further west, Columbus would likely have believed that these voyages challenged his monopoly rights for westward exploration.

Leaving Bristol, the expedition sailed past Ireland and across the Atlantic, making landfall somewhere on the coast of North America on 24 June 1497. The exact location of the landfall has long been disputed, with different communities vying for the honor.

Cabot is reported to have landed only once during the expedition and did not advance "beyond the shooting distance of a crossbow." Pasqualigo and Day both state that the expedition made no contact with any native people; the crew found the remains of a fire, a human trail, nets, and a wooden tool.

The crew appeared to have remained on land just long enough to take on fresh water; they also raised the Venetian and Papal banners, claiming the land for the King of England and recognizing the religious authority of the Roman Catholic Church. After this landing, Cabot spent some weeks "discovering the coast," with most "discovered after turning back."

On return to Bristol, Cabot rode to London to report to the King.

On 10 August 1497, he was given a reward of £10 – equivalent to about two years' pay for an ordinary laborer or craftsman. The explorer was feted; Soncino wrote on 23 August that Cabot "is called the Great Admiral and vast honor is paid to him and he goes dressed in silk and these English run after him like mad."

Such adulation was short-lived, for over the next few months, the King's attention was occupied by the Second Cornish Uprising of 1497, led by Perkin Warbeck.

Once Henry's throne was secure, he gave more thought to Cabot. On 26 September, just a few days after the collapse of the revolt, the King made an award of £2 to Cabot. In December 1497, the explorer was awarded a pension of £20 per year, and in February 1498, he was given a patent to help him prepare a second expedition.

In March and April, the King also advanced a number of loans to Lancelot Thirkill of London, Thomas Bradley, and John Cair, who were to accompany Cabot's new expedition.

Cabot departed with a fleet of five ships from Bristol at the beginning of May 1498, one of which had been prepared by the King. Some of the ships were said to be carrying merchandise, including cloth, caps, lace points, and other "trifles."

This suggests that Cabot intended to engage in trade on this expedition. The Spanish envoy in London reported in July that one of the ships had been caught in a storm and been forced to land in Ireland but that Cabot and the other four ships had continued on.

For centuries, no other records were found (or at least published) that relate to this expedition; it was long believed that Cabot and his fleet were lost at sea. But at least one of the men scheduled to accompany the expedition, Lancelot Thirkill of London, is recorded as living in London in 1501.

The historian Alwyn Ruddock worked on Cabot and his era for 35 years. She had suggested that Cabot and his expedition successfully returned to England in the spring of 1500. She claimed their return followed an epic two-year exploration of the east coast of North America, south into the Chesapeake Bay area and perhaps as far as the Spanish territories in the Caribbean. Ruddock suggested Fr. Giovanni Antonio de Carbonariis and the other friars who accompanied the 1498 expedition had stayed in Newfoundland and founded a mission.

If Carbonariis founded a settlement in North America, it would have been the first Christian settlement on the continent and may have included a church, the only medieval church to have been built there.

The Cabot Project at the University of Bristol was organized in 2009 to search for the evidence on which Ruddock's claims rest, as well as to undertake related studies of Cabot and his expeditions.

The lead researchers on the project, Evan Jones and Margaret Condon, claim to have found further evidence to support aspects of Ruddock's case, particularly in relation to the successful return of the 1498 expedition to Bristol.

They have located documents that appear to place John Cabot in London by May 1500 but have yet to publish their documentation.

- John Cabot's Wikipedia Page

- Cabot Project

- Find a Grave: John Cabot Memorial

- John Cabot Study Guide

- The History Junkie's Guide to Famous Explorers

- The History Junkie's Guide to Colonial America

- By Time Period

- By Location

- Mission Statement

- Books and Documents

- Ask a NL Question

- How to Cite NL Heritage Website

- ____________

- Archival Mysteries

- Alien Enemies, 1914-1918

- Icefields Disaster

- Colony of Avalon

- Let's Teach About Women