- Mobile Site

- Staff Directory

- Advertise with Ars

Filter by topic

- Biz & IT

- Gaming & Culture

Front page layout

22.5 light hours —

Recoding voyager 1—nasa’s interstellar explorer is finally making sense again, "we're pretty much seeing everything we had hoped for, and that's always good news.”.

Stephen Clark - Apr 23, 2024 5:56 pm UTC

Engineers have partially restored a 1970s-era computer on NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft after five months of long-distance troubleshooting, building confidence that humanity's first interstellar probe can eventually resume normal operations.

Several dozen scientists and engineers gathered Saturday in a conference room at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, or connected virtually, to wait for a new signal from Voyager 1. The ground team sent a command up to Voyager 1 on Thursday to recode part of the memory of the spacecraft's Flight Data Subsystem (FDS) , one of the probe's three computers.

“In the minutes leading up to when we were going to see a signal, you could have heard a pin drop in the room," said Linda Spilker, project scientist for NASA's two Voyager spacecraft at JPL. "It was quiet. People were looking very serious. They were looking at their computer screens. Each of the subsystem (engineers) had pages up that they were looking at, to watch as they would be populated."

Finally, a breakthrough

Launched nearly 47 years ago, Voyager 1 is flying on an outbound trajectory more than 15 billion miles (24 billion kilometers) from Earth, and it takes 22-and-a-half hours for a radio signal to cover that distance at the speed of light. This means it takes nearly two days for engineers to uplink a command to Voyager 1 and get a response.

In November, Voyager 1 suddenly stopped transmitting its usual stream of data containing information about the spacecraft's health and measurements from its scientific instruments. Instead, the spacecraft's data stream was entirely unintelligible. Because the telemetry was unreadable, experts on the ground could not easily tell what went wrong. They hypothesized the source of the problem might be in the memory bank of the FDS.

There was a breakthrough last month when engineers sent up a novel command to "poke" Voyager 1's FDS to send back a readout of its memory. This readout allowed engineers to pinpoint the location of the problem in the FDS memory . The FDS is responsible for packaging engineering and scientific data for transmission to Earth.

After a few weeks, NASA was ready to uplink a solution to get the FDS to resume packing engineering data. This data stream includes information on the status of the spacecraft—things like power levels and temperature measurements. This command went up to Voyager 1 through one of NASA's large Deep Space Network antennas Thursday.

Then, the wait for a response. Spilker, who started working on Voyager right out of college in 1977, was in the room when Voyager 1's signal reached Earth Saturday.

"When the time came to get the signal, we could clearly see all of a sudden, boom, we had data, and there were tears and smiles and high fives," she told Ars. "Everyone was very happy and very excited to see that, hey, we're back in communication again with Voyager 1. We're going to see the status of the spacecraft, the health of the spacecraft, for the first time in five months."

Throughout the five months of troubleshooting, Voyager's ground team continued to receive signals indicating the spacecraft was still alive. But until Saturday, they lacked insight into specific details about the status of Voyager 1.

“It’s pretty much just the way we left it," Spilker said. "We're still in the initial phases of analyzing all of the channels and looking at their trends. Some of the temperatures went down a little bit with this period of time that's gone on, but we're pretty much seeing everything we had hoped for. And that's always good news.”

Relocating code

Through their investigation, Voyager's ground team discovered a single chip responsible for storing a portion of the FDS memory stopped working, probably due to either a cosmic ray hit or a failure of aging hardware. This affected some of the computer's software code.

"That took out a section of memory," Spilker said. "What they have to do is relocate that code into a different portion of the memory, and then make sure that anything that uses those codes, those subroutines, know to go to the new location of memory, for access and to run it."

Only about 3 percent of the FDS memory was corrupted by the bad chip, so engineers needed to transplant that code into another part of the memory bank. But no single location is large enough to hold the section of code in its entirety, NASA said.

So the Voyager team divided the code into sections for storage in different places in the FDS. This wasn't just a copy-and-paste job. Engineers needed to modify some of the code to make sure it will all work together. "Any references to the location of that code in other parts of the FDS memory needed to be updated as well," NASA said in a statement.

reader comments

Channel ars technica.

Inside NASA's 5-month fight to save the Voyager 1 mission in interstellar space

After working for five months to re-establish communication with the farthest-flung human-made object in existence, NASA announced this week that the Voyager 1 probe had finally phoned home.

For the engineers and scientists who work on NASA’s longest-operating mission in space, it was a moment of joy and intense relief.

“That Saturday morning, we all came in, we’re sitting around boxes of doughnuts and waiting for the data to come back from Voyager,” said Linda Spilker, the project scientist for the Voyager 1 mission at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “We knew exactly what time it was going to happen, and it got really quiet and everybody just sat there and they’re looking at the screen.”

When at long last the spacecraft returned the agency’s call, Spilker said the room erupted in celebration.

“There were cheers, people raising their hands,” she said. “And a sense of relief, too — that OK, after all this hard work and going from barely being able to have a signal coming from Voyager to being in communication again, that was a tremendous relief and a great feeling.”

The problem with Voyager 1 was first detected in November . At the time, NASA said it was still in contact with the spacecraft and could see that it was receiving signals from Earth. But what was being relayed back to mission controllers — including science data and information about the health of the probe and its various systems — was garbled and unreadable.

That kicked off a monthslong push to identify what had gone wrong and try to save the Voyager 1 mission.

Spilker said she and her colleagues stayed hopeful and optimistic, but the team faced enormous challenges. For one, engineers were trying to troubleshoot a spacecraft traveling in interstellar space , more than 15 billion miles away — the ultimate long-distance call.

“With Voyager 1, it takes 22 1/2 hours to get the signal up and 22 1/2 hours to get the signal back, so we’d get the commands ready, send them up, and then like two days later, you’d get the answer if it had worked or not,” Spilker said.

The team eventually determined that the issue stemmed from one of the spacecraft’s three onboard computers. Spilker said a hardware failure, perhaps as a result of age or because it was hit by radiation, likely messed up a small section of code in the memory of the computer. The glitch meant Voyager 1 was unable to send coherent updates about its health and science observations.

NASA engineers determined that they would not be able to repair the chip where the mangled software is stored. And the bad code was also too large for Voyager 1's computer to store both it and any newly uploaded instructions. Because the technology aboard Voyager 1 dates back to the 1960s and 1970s, the computer’s memory pales in comparison to any modern smartphone. Spilker said it’s roughly equivalent to the amount of memory in an electronic car key.

The team found a workaround, however: They could divide up the code into smaller parts and store them in different areas of the computer’s memory. Then, they could reprogram the section that needed fixing while ensuring that the entire system still worked cohesively.

That was a feat, because the longevity of the Voyager mission means there are no working test beds or simulators here on Earth to test the new bits of code before they are sent to the spacecraft.

“There were three different people looking through line by line of the patch of the code we were going to send up, looking for anything that they had missed,” Spilker said. “And so it was sort of an eyes-only check of the software that we sent up.”

The hard work paid off.

NASA reported the happy development Monday, writing in a post on X : “Sounding a little more like yourself, #Voyager1.” The spacecraft’s own social media account responded , saying, “Hi, it’s me.”

So far, the team has determined that Voyager 1 is healthy and operating normally. Spilker said the probe’s scientific instruments are on and appear to be working, but it will take some time for Voyager 1 to resume sending back science data.

Voyager 1 and its twin, the Voyager 2 probe, each launched in 1977 on missions to study the outer solar system. As it sped through the cosmos, Voyager 1 flew by Jupiter and Saturn, studying the planets’ moons up close and snapping images along the way.

Voyager 2, which is 12.6 billion miles away, had close encounters with Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune and continues to operate as normal.

In 2012, Voyager 1 ventured beyond the solar system , becoming the first human-made object to enter interstellar space, or the space between stars. Voyager 2 followed suit in 2018.

Spilker, who first began working on the Voyager missions when she graduated college in 1977, said the missions could last into the 2030s. Eventually, though, the probes will run out of power or their components will simply be too old to continue operating.

Spilker said it will be tough to finally close out the missions someday, but Voyager 1 and 2 will live on as “our silent ambassadors.”

Both probes carry time capsules with them — messages on gold-plated copper disks that are collectively known as The Golden Record . The disks contain images and sounds that represent life on Earth and humanity’s culture, including snippets of music, animal sounds, laughter and recorded greetings in different languages. The idea is for the probes to carry the messages until they are possibly found by spacefarers in the distant future.

“Maybe in 40,000 years or so, they will be getting relatively close to another star,” Spilker said, “and they could be found at that point.”

Denise Chow is a reporter for NBC News Science focused on general science and climate change.

Subscribe or renew today

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

‘humanity’s spacecraft’ voyager 1 is back online and still exploring.

After five months of glitching, the spacecraft is talking to Earth again from interstellar space

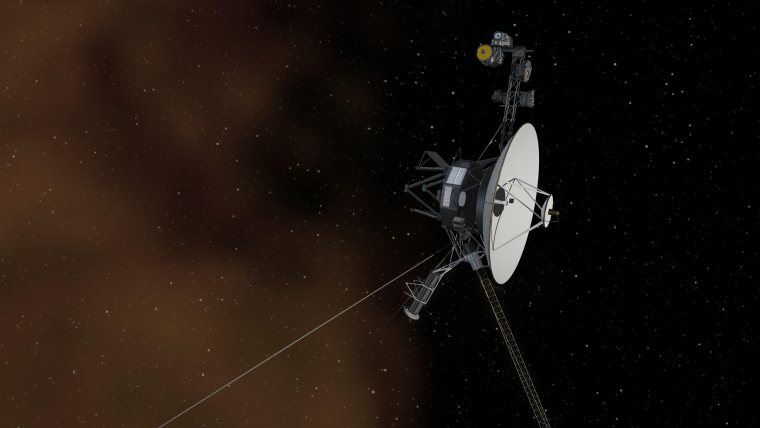

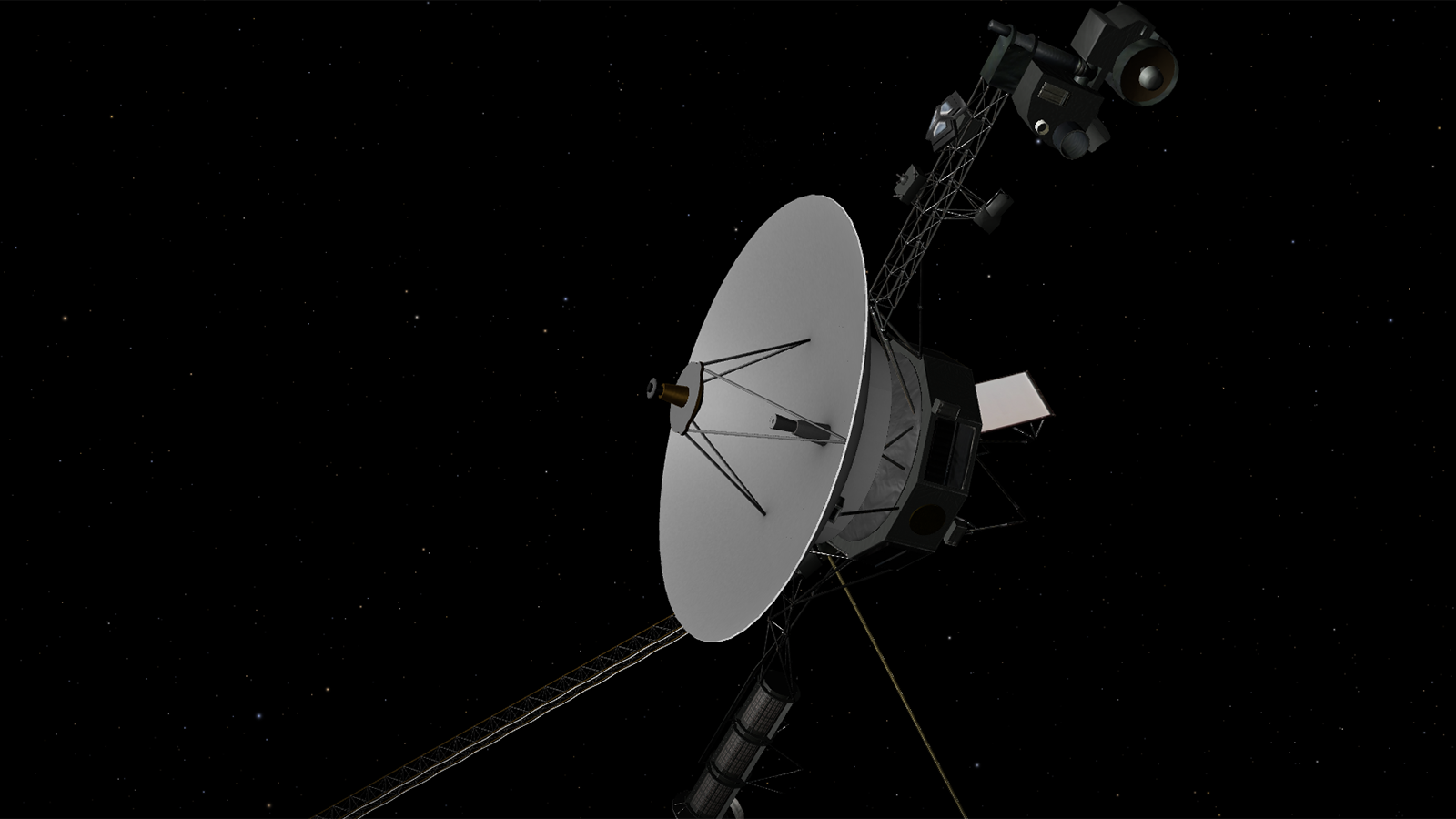

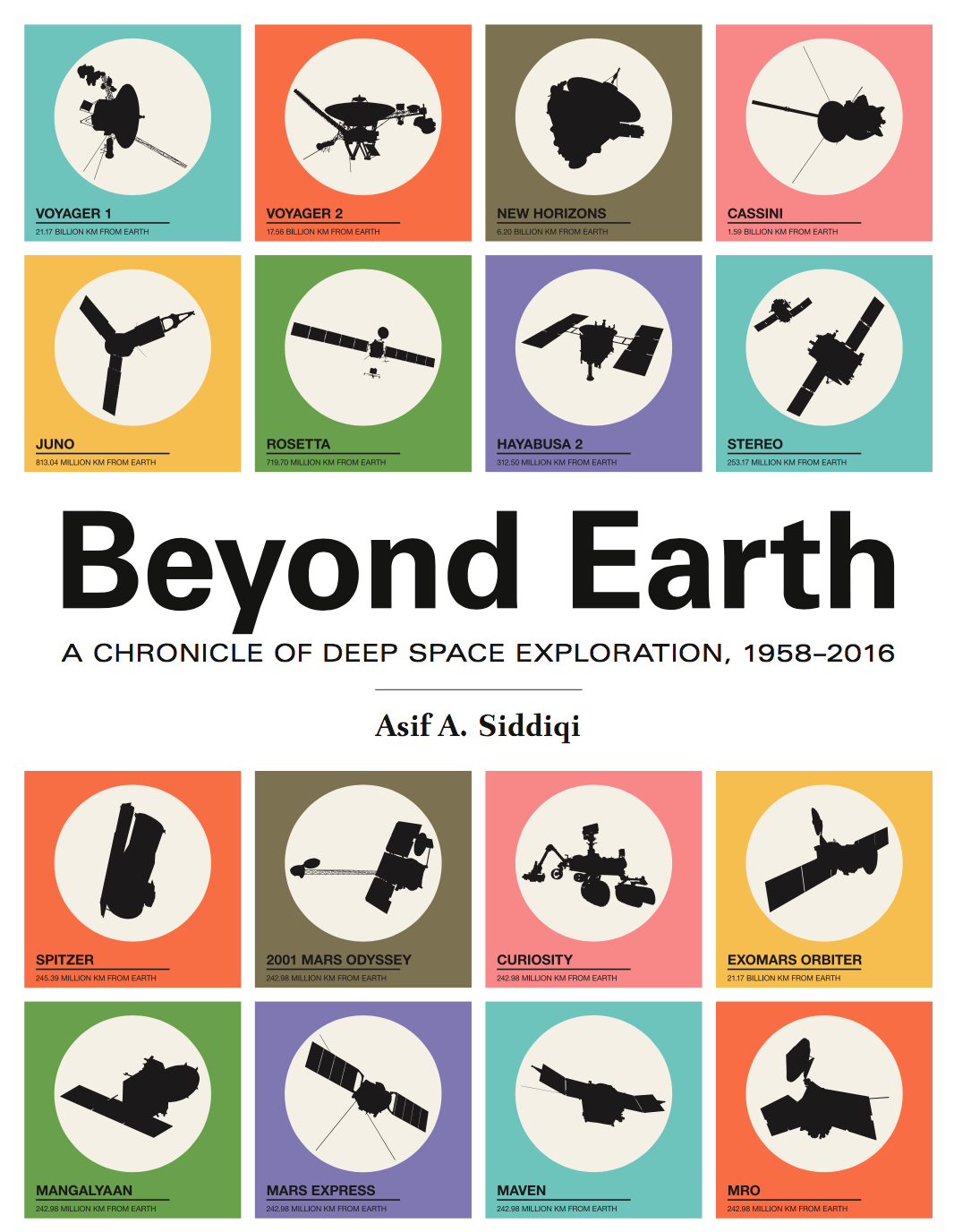

The Voyager 1 spacecraft (illustrated) is back online after a few months of transmitting garbled data. It’s now poised to continue its exploration of interstellar space.

JPL-Caltech/NASA

Share this:

By Ramin Skibba

April 26, 2024 at 11:45 am

After months of challenging trouble-shooting and suspenseful waiting, Voyager 1 is once again talking to Earth.

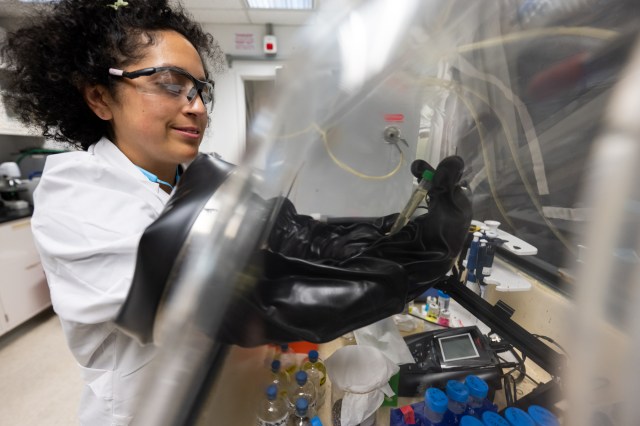

The aging NASA spacecraft, about 24 billion kilometers from home, began transmitting garbled data in November. On April 20, NASA scientists got the probe back online after uploading new flight software to work around a chunk of onboard computer memory that had failed. They’re now receiving data about the spacecraft’s health and hope to hear from its science instruments again in a few weeks, says Suzanne Dodd, the mission’s project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

That means the iconic craft could be on a path to recovery — and to continue its exploration of interstellar space.

Launched in 1977, Voyager 1 briefly visited Jupiter and Saturn before eventually departing the solar system. It and its twin, Voyager 2, are the longest-operating space probes, now tasked with studying far-flung solar particles and cosmic rays. In particular, the probes have been monitoring the changing of the sun’s magnetic field and the density of plasma beyond the solar system, yielding information about the farthest reaches of the sun’s influence .

“The spacecraft is really remarkable in its longevity. It’s incredible,” Dodd says. “We want to keep Voyager going as long as possible so we have this time record of these changes.”

Voyager 1 and 2, cruising along diverging paths, made history by crossing the heliopause in 2012 and 2018 , respectively ( SN: 9/12/13; SN: 12/10/18 ). At nearly 18 billion kilometers from the sun, that’s long been considered the outer extent of our star’s magnetic field and the solar wind, the boundary before interstellar space.

Since then, Dodd says, the science team has made some surprising findings ( SN: 11/4/19 ). For one, they’ve determined that the heliosphere, the huge bubble of space dominated by the solar wind, might not be spherical but have one or two tails, making it shaped like a comet or a croissant.

And thanks to Voyager, scientists now know that, despite expectations otherwise, the sun’s magnetic field and charged particles actually remain significant even beyond the heliopause, says David McComas, a Princeton University astrophysicist not involved in the mission.

Some theories predicted a serene environment in the distant oceans of interstellar space, but the Voyagers keep passing through waves of charged particles, indicating that the solar magnetic field still holds some sway there. What’s more, the probes’ data have shown how ripples in the field form bubbles at the edge of the solar system, which is more frothy and dynamic than expected.

Other missions have begun building on Voyager’s solar physics research. These include NASA’s Interstellar Boundary Explorer, or IBEX, and the Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe, or IMAP, which is set to launch next year. Earth-orbiting IBEX has been measuring high-energy particles to map the heliosphere for 15 years, whereas IMAP will orbit between the sun and Earth, giving it an uninterrupted view of the sun as it monitors the galactic cosmic rays that manage to filter through the heliosphere.

“There’s a huge synergy between the Voyagers and both IBEX and IMAP,” says McComas, principal investigator of the latter two missions. “We were all really scared when Voyager 1 stopped phoning home.”

It will be decades until another mission could accomplish what the Voyagers have done. NASA’s New Horizons soared by Pluto in 2015 and kept going ( SN:8/9/18 ). It’s heading toward the edge of the solar system, but it’s cruising slowly and will run out of power before it can collect data beyond the heliopause.

The Voyagers can fly forever, but power for their instruments is waning. Over the next few years, NASA will shut some down to conserve energy for the rest.

That means Voyager 1’s days of collecting science data are numbered. “It’s a very beloved mission,” Dodd says. “It’s humanity’s spacecraft, and we need to take care of it.”

More Stories from Science News on Space

Separating science fact from fiction in Netflix’s ‘3 Body Problem’

Pluto’s heart-shaped basin might not hide an ocean after all

Our picture of habitability on Europa, a top contender for hosting life, is changing

Jupiter’s moon Io may have been volcanically active ever since it was born

50 years ago, scientists found a lunar rock nearly as old as the moon

How a sugar acid crucial for life could have formed in interstellar clouds

What Science News saw during the solar eclipse

During the awe of totality, scientists studied our planet’s reactions

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Well, hello, Voyager 1! The venerable spacecraft is once again making sense

Nell Greenfieldboyce

Members of the Voyager team celebrate at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory after receiving data about the health and status of Voyager 1 for the first time in months. NASA/JPL-Caltech hide caption

Members of the Voyager team celebrate at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory after receiving data about the health and status of Voyager 1 for the first time in months.

NASA says it is once again able to get meaningful information back from the Voyager 1 probe, after months of troubleshooting a glitch that had this venerable spacecraft sending home messages that made no sense.

The Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 probes launched in 1977 on a mission to study Jupiter and Saturn but continued onward through the outer reaches of the solar system. In 2012, Voyager 1 became the first spacecraft to enter interstellar space, the previously unexplored region between the stars. (Its twin, traveling in a different direction, followed suit six years later.)

Voyager 1 had been faithfully sending back readings about this mysterious new environment for years — until November, when its messages suddenly became incoherent .

NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft is talking nonsense. Its friends on Earth are worried

It was a serious problem that had longtime Voyager scientists worried that this historic space mission wouldn't be able to recover. They'd hoped to be able to get precious readings from the spacecraft for at least a few more years, until its power ran out and its very last science instrument quit working.

For the last five months, a small team at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California has been working to fix it. The team finally pinpointed the problem to a memory chip and figured out how to restore some essential software code.

"When the mission flight team heard back from the spacecraft on April 20, they saw that the modification worked: For the first time in five months, they have been able to check the health and status of the spacecraft," NASA stated in an update.

The usable data being returned so far concerns the workings of the spacecraft's engineering systems. In the coming weeks, the team will do more of this software repair work so that Voyager 1 will also be able to send science data, letting researchers once again see what the probe encounters as it journeys through interstellar space.

After a 12.3 billion-mile 'shout,' NASA regains full contact with Voyager 2

- interstellar mission

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Voyager 1 transmitting data again after Nasa remotely fixes 46-year-old probe

Engineers spent months working to repair link with Earth’s most distant spacecraft, says space agency

Earth’s most distant spacecraft, Voyager 1, has started communicating properly again with Nasa after engineers worked for months to remotely fix the 46-year-old probe.

Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), which makes and operates the agency’s robotic spacecraft, said in December that the probe – more than 15bn miles (24bn kilometres) away – was sending gibberish code back to Earth.

In an update released on Monday , JPL announced the mission team had managed “after some inventive sleuthing” to receive usable data about the health and status of Voyager 1’s engineering systems. “The next step is to enable the spacecraft to begin returning science data again,” JPL said. Despite the fault, Voyager 1 had operated normally throughout, it added.

Launched in 1977, Voyager 1 was designed with the primary goal of conducting close-up studies of Jupiter and Saturn in a five-year mission. However, its journey continued and the spacecraft is now approaching a half-century in operation.

Voyager 1 crossed into interstellar space in August 2012, making it the first human-made object to venture out of the solar system. It is currently travelling at 37,800mph (60,821km/h).

Hi, it's me. - V1 https://t.co/jgGFBfxIOe — NASA Voyager (@NASAVoyager) April 22, 2024

The recent problem was related to one of the spacecraft’s three onboard computers, which are responsible for packaging the science and engineering data before it is sent to Earth. Unable to repair a broken chip, the JPL team decided to move the corrupted code elsewhere, a tricky job considering the old technology.

The computers on Voyager 1 and its sister probe, Voyager 2, have less than 70 kilobytes of memory in total – the equivalent of a low-resolution computer image. They use old-fashioned digital tape to record data.

The fix was transmitted from Earth on 18 April but it took two days to assess if it had been successful as a radio signal takes about 22 and a half hours to reach Voyager 1 and another 22 and a half hours for a response to come back to Earth. “When the mission flight team heard back from the spacecraft on 20 April, they saw that the modification worked,” JPL said.

Alongside its announcement, JPL posted a photo of members of the Voyager flight team cheering and clapping in a conference room after receiving usable data again, with laptops, notebooks and doughnuts on the table in front of them.

The Retired Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield, who flew two space shuttle missions and acted as commander of the International Space Station, compared the JPL mission to long-distance maintenance on a vintage car.

“Imagine a computer chip fails in your 1977 vehicle. Now imagine it’s in interstellar space, 15bn miles away,” Hadfield wrote on X . “Nasa’s Voyager probe just got fixed by this team of brilliant software mechanics.

Voyager 1 and 2 have made numerous scientific discoveries , including taking detailed recordings of Saturn and revealing that Jupiter also has rings, as well as active volcanism on one of its moons, Io. The probes later discovered 23 new moons around the outer planets.

As their trajectory takes them so far from the sun, the Voyager probes are unable to use solar panels, instead converting the heat produced from the natural radioactive decay of plutonium into electricity to power the spacecraft’s systems.

Nasa hopes to continue to collect data from the two Voyager spacecraft for several more years but engineers expect the probes will be too far out of range to communicate in about a decade, depending on how much power they can generate. Voyager 2 is slightly behind its twin and is moving slightly slower.

In roughly 40,000 years, the probes will pass relatively close, in astronomical terms, to two stars. Voyager 1 will come within 1.7 light years of a star in the constellation Ursa Minor, while Voyager 2 will come within a similar distance of a star called Ross 248 in the constellation of Andromeda.

Cosmic cleaners: the scientists scouring English cathedral roofs for space dust

Russia acknowledges continuing air leak from its segment of space station

Uncontrolled European satellite falls to Earth after 30 years in orbit

Cosmonaut Oleg Kononenko sets world record for most time spent in space

‘Old smokers’: astronomers discover giant ancient stars in Milky Way

Nasa postpones plans to send humans to moon

What happened to the Peregrine lander and what does it mean for moon missions?

Peregrine 1 has ‘no chance’ of landing on moon due to fuel leak

Most viewed.

Suggested Searches

- Climate Change

- Expedition 64

- Mars perseverance

- SpaceX Crew-2

- International Space Station

- View All Topics A-Z

Humans in Space

Earth & climate, the solar system, the universe, aeronautics, learning resources, news & events.

NASA-Led Study Provides New Global Accounting of Earth’s Rivers

NASA’s Hubble Pauses Science Due to Gyro Issue

NASA’s Optical Comms Demo Transmits Data Over 140 Million Miles

- Search All NASA Missions

- A to Z List of Missions

- Upcoming Launches and Landings

- Spaceships and Rockets

- Communicating with Missions

- James Webb Space Telescope

- Hubble Space Telescope

- Why Go to Space

- Astronauts Home

- Commercial Space

- Destinations

- Living in Space

- Explore Earth Science

- Earth, Our Planet

- Earth Science in Action

- Earth Multimedia

- Earth Science Researchers

- Pluto & Dwarf Planets

- Asteroids, Comets & Meteors

- The Kuiper Belt

- The Oort Cloud

- Skywatching

- The Search for Life in the Universe

- Black Holes

- The Big Bang

- Dark Energy & Dark Matter

- Earth Science

- Planetary Science

- Astrophysics & Space Science

- The Sun & Heliophysics

- Biological & Physical Sciences

- Lunar Science

- Citizen Science

- Astromaterials

- Aeronautics Research

- Human Space Travel Research

- Science in the Air

- NASA Aircraft

- Flight Innovation

- Supersonic Flight

- Air Traffic Solutions

- Green Aviation Tech

- Drones & You

- Technology Transfer & Spinoffs

- Space Travel Technology

- Technology Living in Space

- Manufacturing and Materials

- Science Instruments

- For Kids and Students

- For Educators

- For Colleges and Universities

- For Professionals

- Science for Everyone

- Requests for Exhibits, Artifacts, or Speakers

- STEM Engagement at NASA

- NASA's Impacts

- Centers and Facilities

- Directorates

- Organizations

- People of NASA

- Internships

- Our History

- Doing Business with NASA

- Get Involved

- Aeronáutica

- Ciencias Terrestres

- Sistema Solar

- All NASA News

- Video Series on NASA+

- Newsletters

- Social Media

- Media Resources

- Upcoming Launches & Landings

- Virtual Events

- Sounds and Ringtones

- Interactives

- STEM Multimedia

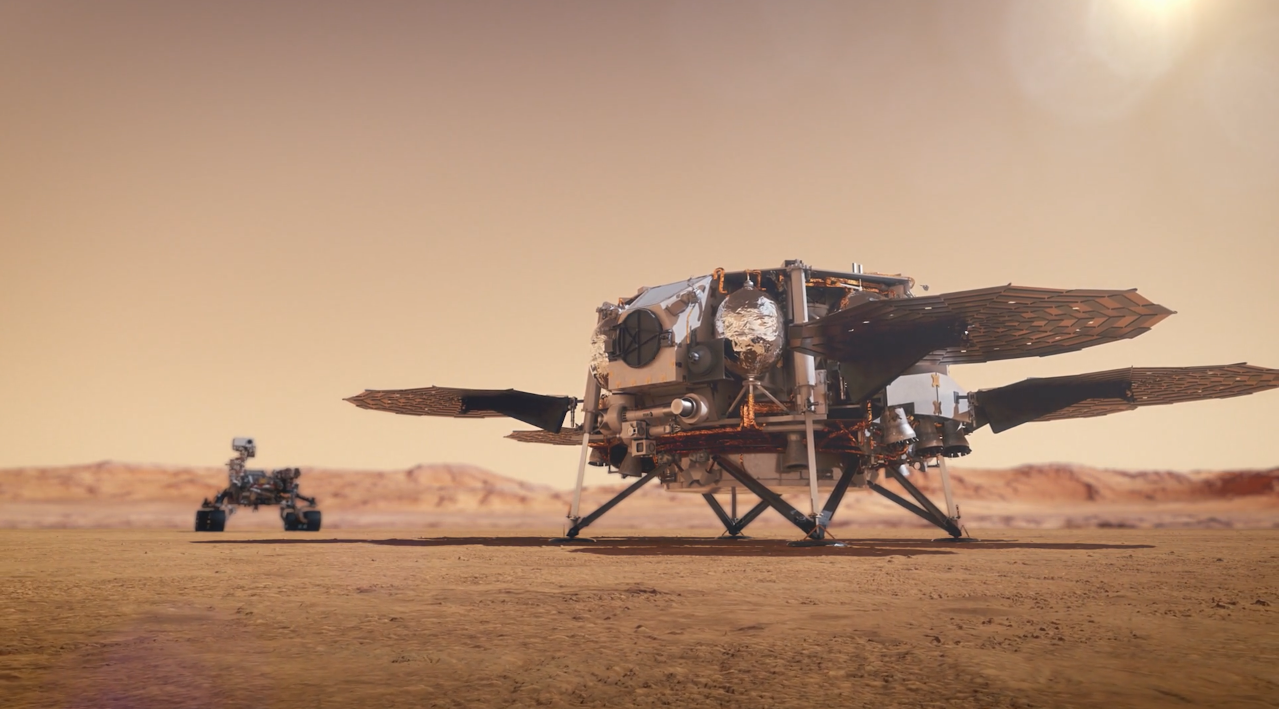

Correction and Clarification of C.26 Rapid Mission Design Studies for Mars Sample Return

NASA’s Commercial Partners Deliver Cargo, Crew for Station Science

NASA Shares Lessons of Human Systems Integration with Industry

Work Underway on Large Cargo Landers for NASA’s Artemis Moon Missions

NASA’s ORCA, AirHARP Projects Paved Way for PACE to Reach Space

Amendment 11: Physical Oceanography not solicited in ROSES-2024

Why is Methane Seeping on Mars? NASA Scientists Have New Ideas

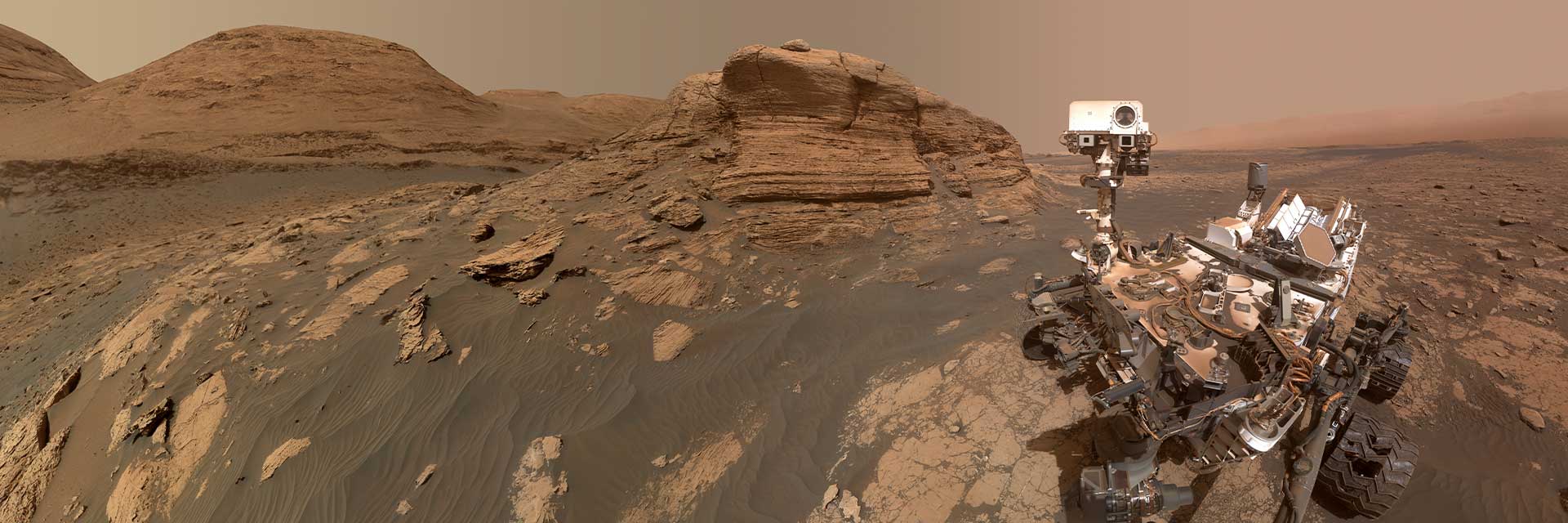

Mars Science Laboratory: Curiosity Rover

Hubble Spots a Magnificent Barred Galaxy

NASA’s Chandra Releases Doubleheader of Blockbuster Hits

Explore the Universe with the First E-Book from NASA’s Fermi

NASA Grant Brings Students at Underserved Institutions to the Stars

NASA Photographer Honored for Thrilling Inverted In-Flight Image

NASA’s Ingenuity Mars Helicopter Team Says Goodbye … for Now

NASA Langley Team to Study Weather During Eclipse Using Uncrewed Vehicles

NASA Data Helps Beavers Build Back Streams

NASA’s Near Space Network Enables PACE Climate Mission to ‘Phone Home’

Washington State High Schooler Wins 2024 NASA Student Art Contest

NASA STEM Artemis Moon Trees

Kiyun Kim: From Intern to Accessibility Advocate

Diez maneras en que los estudiantes pueden prepararse para ser astronautas

Astronauta de la NASA Marcos Berríos

Resultados científicos revolucionarios en la estación espacial de 2023

Nasa’s voyager 2 probe enters interstellar space.

For the second time in history, a human-made object has reached the space between the stars. NASA’s Voyager 2 probe now has exited the heliosphere – the protective bubble of particles and magnetic fields created by the Sun.

Members of NASA’s Voyager team will discuss the findings at a news conference at 11 a.m. EST (8 a.m. PST) today at the meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) in Washington. The news conference will stream live on the agency’s website .

Comparing data from different instruments aboard the trailblazing spacecraft, mission scientists determined the probe crossed the outer edge of the heliosphere on Nov. 5. This boundary, called the heliopause, is where the tenuous, hot solar wind meets the cold, dense interstellar medium. Its twin, Voyager 1 , crossed this boundary in 2012, but Voyager 2 carries a working instrument that will provide first-of-its-kind observations of the nature of this gateway into interstellar space.

Voyager 2 now is slightly more than 11 billion miles (18 billion kilometers) from Earth. Mission operators still can communicate with Voyager 2 as it enters this new phase of its journey, but information – moving at the speed of light – takes about 16.5 hours to travel from the spacecraft to Earth. By comparison, light traveling from the Sun takes about eight minutes to reach Earth.

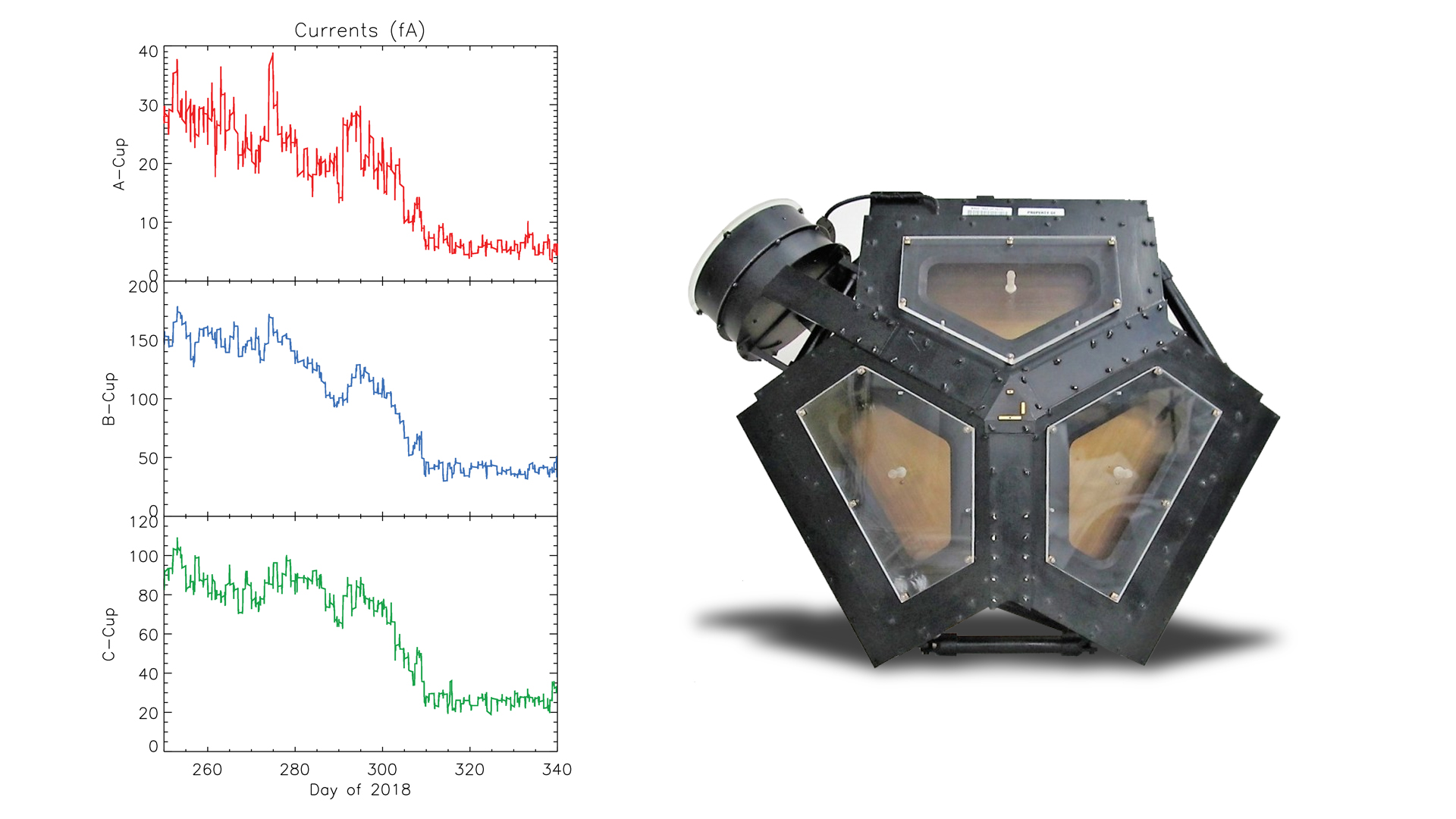

The most compelling evidence of Voyager 2’s exit from the heliosphere came from its onboard Plasma Science Experiment ( PLS ), an instrument that stopped working on Voyager 1 in 1980, long before that probe crossed the heliopause. Until recently, the space surrounding Voyager 2 was filled predominantly with plasma flowing out from our Sun. This outflow, called the solar wind, creates a bubble – the heliosphere – that envelopes the planets in our solar system. The PLS uses the electrical current of the plasma to detect the speed, density, temperature, pressure and flux of the solar wind. The PLS aboard Voyager 2 observed a steep decline in the speed of the solar wind particles on Nov. 5. Since that date, the plasma instrument has observed no solar wind flow in the environment around Voyager 2, which makes mission scientists confident the probe has left the heliosphere.

In addition to the plasma data, Voyager’s science team members have seen evidence from three other onboard instruments – the cosmic ray subsystem, the low energy charged particle instrument and the magnetometer – that is consistent with the conclusion that Voyager 2 has crossed the heliopause. Voyager’s team members are eager to continue to study the data from these other onboard instruments to get a clearer picture of the environment through which Voyager 2 is traveling.

“There is still a lot to learn about the region of interstellar space immediately beyond the heliopause,” said Ed Stone, Voyager project scientist based at Caltech in Pasadena, California.

Together, the two Voyagers provide a detailed glimpse of how our heliosphere interacts with the constant interstellar wind flowing from beyond. Their observations complement data from NASA’s Interstellar Boundary Explorer ( IBEX ), a mission that is remotely sensing that boundary. NASA also is preparing an additional mission – the upcoming Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe ( IMAP ), due to launch in 2024 – to capitalize on the Voyagers’ observations.

“Voyager has a very special place for us in our heliophysics fleet,” said Nicola Fox, director of the Heliophysics Division at NASA Headquarters. “Our studies start at the Sun and extend out to everything the solar wind touches. To have the Voyagers sending back information about the edge of the Sun’s influence gives us an unprecedented glimpse of truly uncharted territory.”

While the probes have left the heliosphere, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 have not yet left the solar system, and won’t be leaving anytime soon. The boundary of the solar system is considered to be beyond the outer edge of the Oort Cloud , a collection of small objects that are still under the influence of the Sun’s gravity. The width of the Oort Cloud is not known precisely, but it is estimated to begin at about 1,000 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun and to extend to about 100,000 AU. One AU is the distance from the Sun to Earth. It will take about 300 years for Voyager 2 to reach the inner edge of the Oort Cloud and possibly 30,000 years to fly beyond it.

The Voyager probes are powered using heat from the decay of radioactive material, contained in a device called a radioisotope thermal generator ( RTG ). The power output of the RTGs diminishes by about four watts per year, which means that various parts of the Voyagers, including the cameras on both spacecraft, have been turned off over time to manage power.

“I think we’re all happy and relieved that the Voyager probes have both operated long enough to make it past this milestone,” said Suzanne Dodd, Voyager project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. “This is what we’ve all been waiting for. Now we’re looking forward to what we’ll be able to learn from having both probes outside the heliopause.”

Voyager 2 launched in 1977, 16 days before Voyager 1, and both have traveled well beyond their original destinations. The spacecraft were built to last five years and conduct close-up studies of Jupiter and Saturn. However, as the mission continued, additional flybys of the two outermost giant planets, Uranus and Neptune, proved possible. As the spacecraft flew across the solar system, remote-control reprogramming was used to endow the Voyagers with greater capabilities than they possessed when they left Earth. Their two-planet mission became a four-planet mission. Their five-year lifespans have stretched to 41 years, making Voyager 2 NASA’s longest running mission.

The Voyager story has impacted not only generations of current and future scientists and engineers, but also Earth’s culture, including film, art and music. Each spacecraft carries a Golden Record of Earth sounds, pictures and messages. Since the spacecraft could last billions of years, these circular time capsules could one day be the only traces of human civilization.

Voyager’s mission controllers communicate with the probes using NASA’s Deep Space Network ( DSN ), a global system for communicating with interplanetary spacecraft. The DSN consists of three clusters of antennas in Goldstone, California; Madrid, Spain; and Canberra, Australia.

The Voyager Interstellar Mission is a part of NASA’s Heliophysics System Observatory, sponsored by the Heliophysics Division of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. JPL built and operates the twin Voyager spacecraft. NASA’s DSN, managed by JPL, is an international network of antennas that supports interplanetary spacecraft missions and radio and radar astronomy observations for the exploration of the solar system and the universe. The network also supports selected Earth-orbiting missions. The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Australia’s national science agency, operates both the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex, part of the DSN, and the Parkes Observatory, which NASA has been using to downlink data from Voyager 2 since Nov. 8.

For more information about the Voyager mission, visit:

More information about NASA’s Heliophysics missions is available online at:

Dwayne Brown / Karen Fox Headquarters, Washington 202-358-1726 / 301-286-6284 [email protected] / [email protected] Calla Cofield Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. 626-808-2469 [email protected]

NASA's interstellar Voyager 1 spacecraft isn't doing so well — here's what we know

Since late 2023, engineers have been trying to get the Voyager spacecraft back online.

On Dec. 12, 2023, NASA shared some worrisome news about Voyager 1, the first probe to walk away from our solar system 's gravitational party and enter the isolation of interstellar space . Surrounded by darkness, Voyager 1 seems to be glitching.

It has been out there for more than 45 years, having supplied us with a bounty of treasure like the discovery of two new moons of Jupiter, another incredible ring of Saturn and the warm feeling that comes from knowing pieces of our lives will drift across the cosmos even after we're gone. (See: The Golden Record .) But now, Voyager 1 's fate seems to be uncertain.

As of Feb. 6, NASA said the team remains working on bringing the spacecraft back to proper health. "Engineers are still working to resolve a data issue on Voyager 1," NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory said in a post on X (formerly Twitter). "We can talk to the spacecraft, and it can hear us, but it's a slow process given the spacecraft's incredible distance from Earth."

Related: NASA's interstellar Voyager probes get software updates beamed from 12 billion miles away

So, on the bright side, even though Voyager 1 sits so utterly far away from us, ground control can actually communicate with it. In fact, last year, scientists beamed some software updates to the spacecraft as well as its counterpart, Voyager 2 , from billions of miles away. Though on the dimmer side, due to that distance, a single back-and-forth communication between Voyager 1 and anyone on Earth takes a total of 45 hours. If NASA finds a solution, it won't be for some time .

The issue, engineers realized, has to do with one of Voyager 1's onboard computers known as the Flight Data System, or FDS. (The backup FDS stopped working in 1981.)

"The FDS is not communicating properly with one of the probe's subsystems, called the telemetry modulation unit (TMU)," NASA said in a blog post. "As a result, no science or engineering data is being sent back to Earth." This is of course despite the fact that ground control can indeed send information to Voyager 1, which, at the time of writing this article , sits about 162 AU's from our planet. One AU is equal to the distance between the Earth and the sun , or 149,597,870.7 kilometers (92,955,807.3 miles).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

From the beginning

Voyager 1's FDS dilemma was first noticed last year , after the probe's TMU stopped sending back clear data and started procuring a bunch of rubbish.

As NASA explains in the blog post, one of the FDS' core jobs is to collect information about the spacecraft itself, in terms of its health and general status. "It then combines that information into a single data 'package' to be sent back to Earth by the TMU," the post says. "The data is in the form of ones and zeros, or binary code."

However, the TMU seemed to be shuffling back a non-intelligible version of binary code recently. Or, as the team puts it, it seems like the system is "stuck." Yes, the engineers tried turning it off and on again.

That didn't work.

— SpaceX's Starship to launch 'Starlab' private space station in late 2020s

— Wonder what it's like to fall into Uranus? These scientists do, too

— Scientists' predictions for the long-term future of the Voyager Golden Records will blow your mind

Then, in early February, Suzanne Dodd, Voyager project manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, told Ars Technica that the team might have pinpointed what's going on with the FDS at last. The theory is that the problem lies somewhere with the FDS' memory; there might be a computer bit that got corrupted. Unfortunately, though, because the FDS and TMU work together to relay information about the spacecraft's health, engineers are having a hard time figuring out where exactly the possible corruption may exist. The messenger is the one that needs a messenger.

They do know, however, that the spacecraft must be alive because they are receiving what's known as a "carrier tone." Carrier tone wavelengths don't carry information, but they are signals nonetheless, akin to a heartbeat. It's also worth considering that Voyager 1 has experienced problems before, such as in 2022 when the probe's "attitude articulation and control system" exhibited some blips that were ultimately patched up. Something similar happened to Voyager 2 during the summer of 2023, when Voyager 1's twin suffered some antenna complications before coming right back online again.

Still, Dodd says this situation has been the most serious since she began working on the historic Voyager mission.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Monisha Ravisetti is Space.com's Astronomy Editor. She covers black holes, star explosions, gravitational waves, exoplanet discoveries and other enigmas hidden across the fabric of space and time. Previously, she was a science writer at CNET, and before that, reported for The Academic Times. Prior to becoming a writer, she was an immunology researcher at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. She graduated from New York University in 2018 with a B.A. in philosophy, physics and chemistry. She spends too much time playing online chess. Her favorite planet is Earth.

NASA's Voyager 1 glitch has scientists sad yet hopeful: 'Voyager 2 is still going strong'

NASA's Voyager 1 probe in interstellar space can't phone home (again) due to glitch

Russia vetoes UN resolution against nuclear weapons in space

- Classical Motion There must be more to this story. Let me see if I have this right. They can receive a carrier. But the modulator gives them junk. Or possibly the processor's memory. And they can send new software. New instructions. So, why not simply use the packet data, to key the carrier on and off. OOK On and Off Keying. Telegraphy. Reply

Admin said: NASA's Voyager 1 deep space probe started glitching last year, and scientists aren't sure they can fix it. NASA's interstellar Voyager 1 spacecraft isn't doing so well — here's what we know : Read more

- Classical Motion I wish something would kick one of them back to us. I would love to see an analysis of every cubic cm of it. Reply

- billslugg Modulating the carrier wave would do no good unless the carrier knew what information to send us. The unit that failed takes the raw data and then tells the carrier what to say. Without the modulation unit there is no data to send. Reply

Classical Motion said: I wish something would kick one of them back to us. I would love to see an analysis of every cubic cm of it.

- Classical Motion I read that they were not sure if it was the modulator or the packet memory. The packet buffer. If they can send patch, it's easy to relocate that buffer into another section of memory. This can be done at several different memory locations to verify if it is a memory problem. If that works, then the modulator is ok. If the modulator fails with all those buffers, then it's the modulator. Turn off modulator. Just enable the carrier for a certain duration for a 1 bit. And turn it off for that certain duration for a 0 bit. One simply rotates that buffer string thru the accumulator at the duration rate, and use status flags to key the transmitter. Very simple and very short code. The packet is nothing more that a 128 BYTE or multiple size string of 1s and 0s. OOK is a very common wireless modulation. That's why I commented on more must be going on. And I would like to see what 30 years naked in space does to man molded matter. Reply

Classical Motion said: I read that they were not sure if it was the modulator or the packet memory. The packet buffer. If they can send patch, it's easy to relocate that buffer into another section of memory. This can be done at several different memory locations to verify if it is a memory problem. If that works, then the modulator is ok. If the modulator fails with all those buffers, then it's the modulator. Turn off modulator. Just enable the carrier for a certain duration for a 1 bit. And turn it off for that certain duration for a 0 bit. One simply rotates that buffer string thru the accumulator at the duration rate, and use status flags to key the transmitter. Very simple and very short code. The packet is nothing more that a 128 BYTE or multiple size string of 1s and 0s. OOK is a very common wireless modulation. That's why I commented on more must be going on. And I would like to see what 30 years naked in space does to man molded matter.

- damienassurre I think they should make another space craft and have it pick up voyager 1 and bring it back the info it went through would very valuable to stellar travel Reply

damienassurre said: I think they should make another space craft and have it pick up voyager 1 and bring it back the info it went through would very valuable to stellar travel

- billslugg The newer forms of memory can't be used easily in outer space as their feature size is too small and too easily corrupted by a cosmic ray. Very large, bulky features keep spacecraft memory far smaller than what earthbound computers can enjoy. As far as returning one of the Voyagers to Earth, it would take several thousand years using available technology. Better to wait for more advanced propulsion technologies. Reply

- View All 20 Comments

Most Popular

- 2 Beavers are helping fight climate change, satellite data shows

- 3 Astronomers just discovered a comet that could be brighter than most stars when we see it next year. Or will it?

- 4 This Week In Space podcast: Episode 108 — Starliner: Better Late Than Never?

- 5 Boeing's Starliner spacecraft will not fly private missions yet, officials say

Contact restored with NASA’s Voyager 1 space probe

Contact restored.

That was the message relieved NASA officials shared after the agency regained full contact with the Voyager 1 space probe, the most distant human-made object in the universe, scientists have announced.

For the first time since November, the spacecraft is returning usable data about the health and status of its onboard engineering systems, NASA said in a news release Monday.

The 46-year-old pioneering probe, now 15.1 billion miles from Earth, has continually defied expectations for its life span as it ventures farther into the uncharted territory of the cosmos .

More: Voyager 1 is 15 billion miles from home and broken. Here's how NASA is trying to fix it.

Computer experts to the rescue

It wasn't as easy as hitting Control-Alt-Delete, but top experts at NASA and CalTech were able to fix the balky, ancient computer on board the probe that was causing the communication breakdown – at least for now.

A computer problem aboard Voyager 1 on Nov. 14, 2023, corrupted the stream of science and engineering data the craft sent to Earth, making it unreadable .

Although the radio signal from the spacecraft had never ceased its connection to ground control operators on Earth, that signal had not carried any usable data since November, NASA said. After some serious sleuthing to fix the onboard computer, that changed on April 20, when NASA finally received usable data.

In interstellar space

The probe and its twin, Voyager 2, are the only spacecraft to ever fly in interstellar space (the space between the stars).

Voyager 2 continues to operate normally, NASA reports. Launched more than 46 years ago , the twin spacecraft are standouts on two fronts: they've operated the longest and traveled the farthest of any spacecraft ever.

Before the start of their interstellar exploration, both probes flew by Saturn and Jupiter, and Voyager 2 flew by Uranus and Neptune.

More: NASA gave Voyager 1 a 'poke' amid communication woes. Here's why the response was encouraging.

They were designed to last five years but have become the longest-operating spacecraft in history. Both carry gold-plated copper discs containing sounds and images from Earth, content that was chosen by a team headed by celebrity astronomer Carl Sagan .

For perspective, it was the summer of 1977 when the Voyager probes left Earth. "Star Wars" was No. 1 at the box office, Jimmy Carter was in the first year of his presidency, and Elvis Presley had just died.

Contributing: Eric Lagatta and George Petras

Voyager 1 and 2: The Interstellar Mission

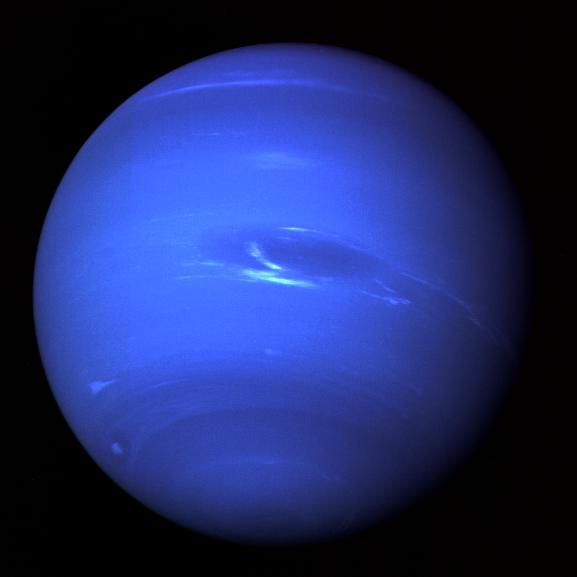

An image of Neptune taken by the Voyager 2 spacecraft. Image credit: NASA

NASA has beautiful photos of every planet in our solar system. We even have images of faraway Neptune , as you can see in the photo above.

Neptune is much too distant for an astronaut to travel there with a camera. So, how do we have pictures from distant locations in our solar system? Our photographers were two spacecraft, called Voyager 1 and Voyager 2!

An artist’s rendering of one of the Voyager spacecraft. Image credit: NASA

The Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft launched from Earth in 1977. Their mission was to explore Jupiter and Saturn —and beyond to the outer planets of our solar system. This was a big task. No human-made object had ever attempted a journey like that before.

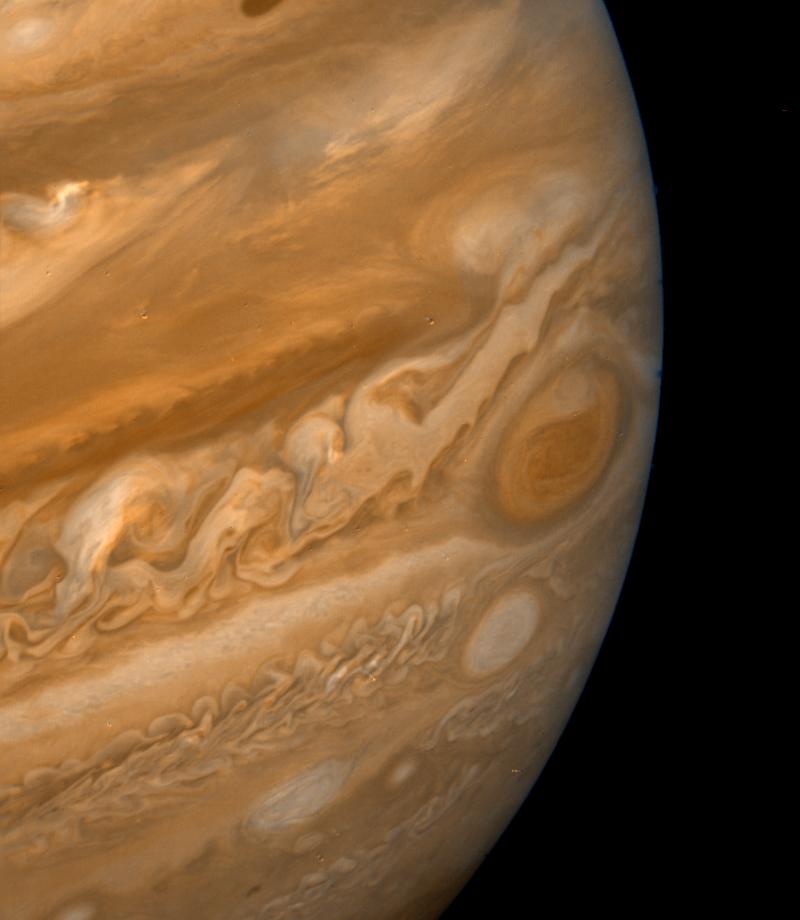

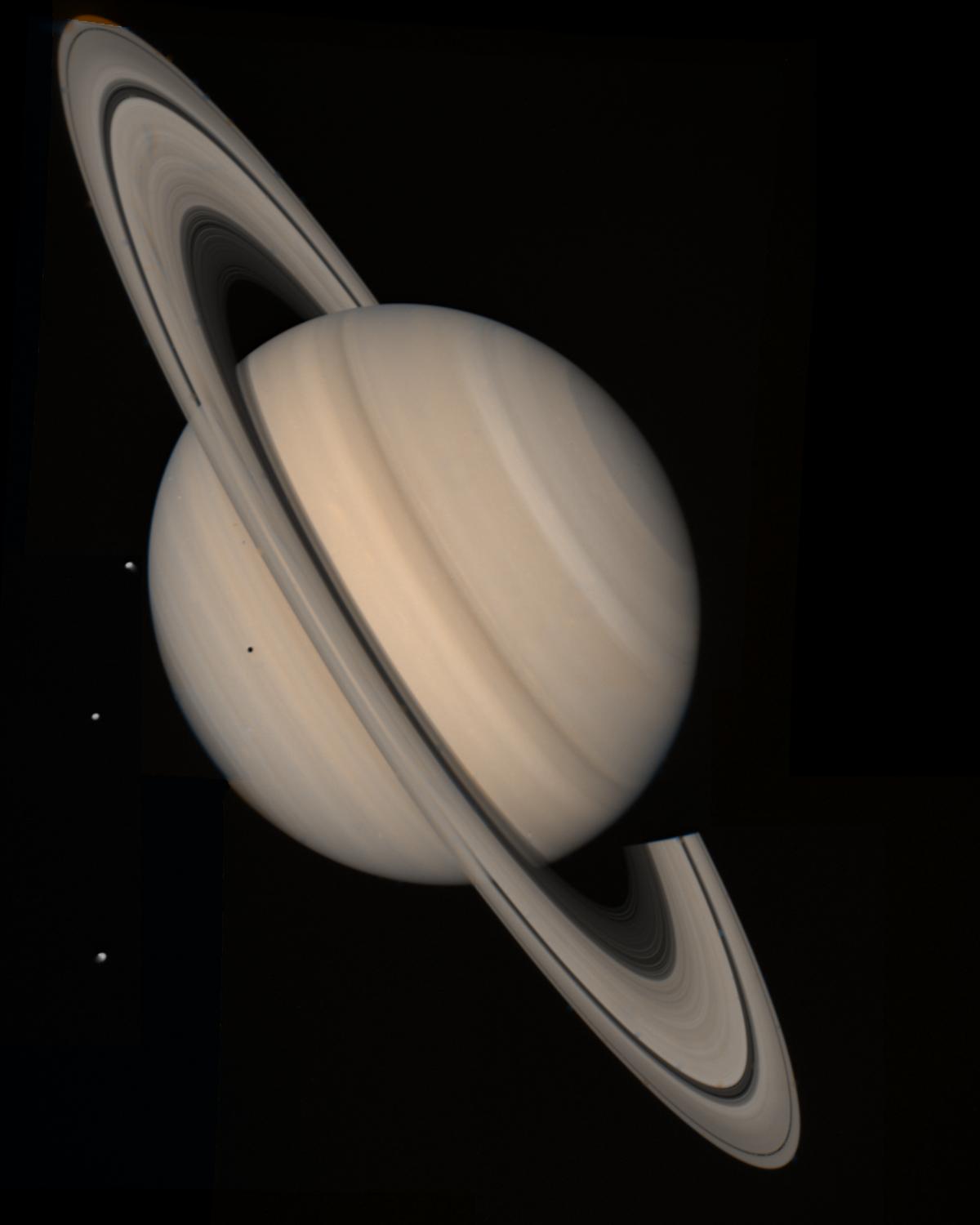

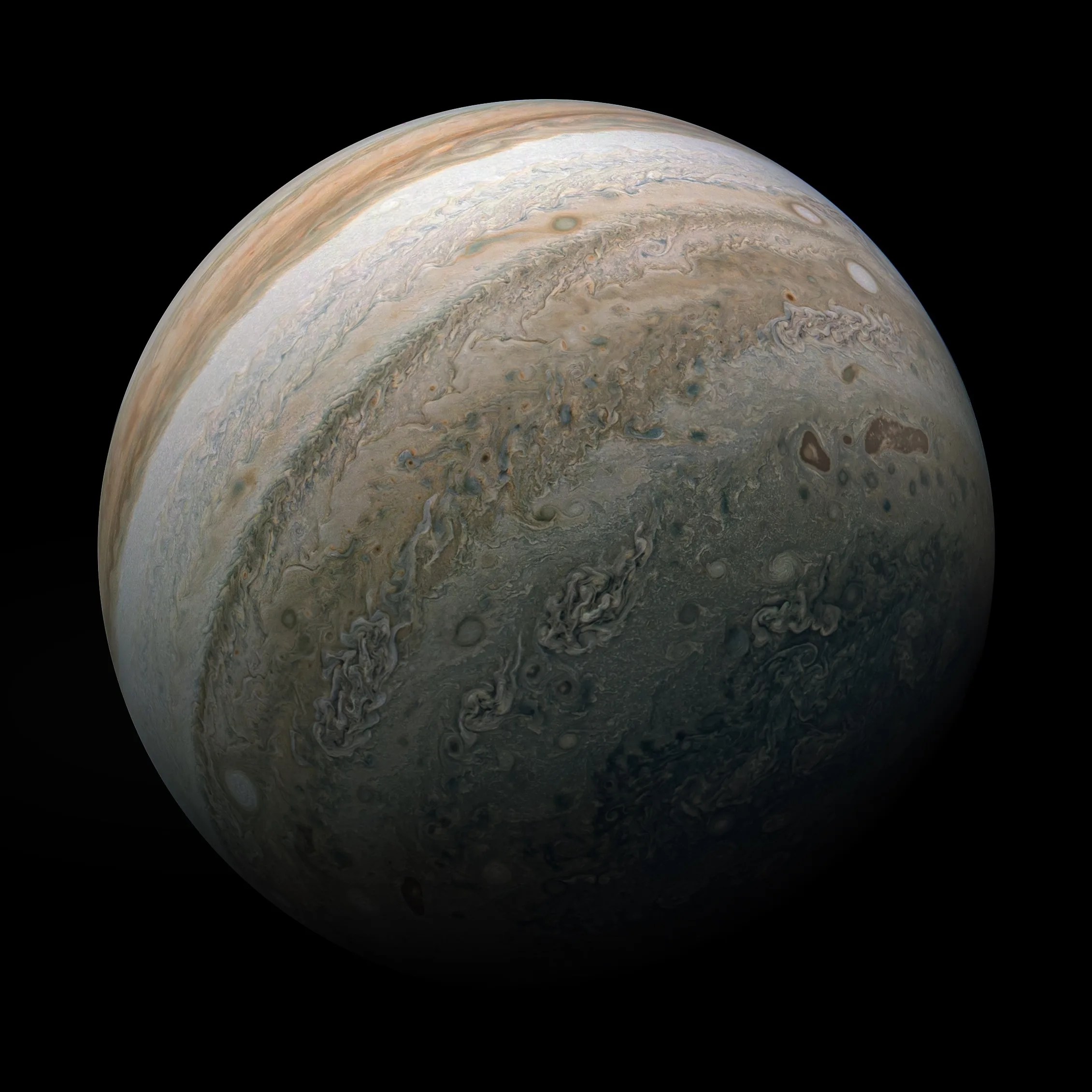

The two spacecraft took tens of thousands of pictures of Jupiter and Saturn and their moons. The pictures from Voyager 1 and 2 allowed us to see lots of things for the first time. For example, they captured detailed photos of Jupiter's clouds and storms, and the structure of Saturn's rings .

Image of storms on Jupiter taken by the Voyager 1 spacecraft. Image credit: NASA

Voyager 1 and 2 also discovered active volcanoes on Jupiter's moon Io , and much more. Voyager 2 also took pictures of Uranus and Neptune. Together, the Voyager missions discovered 22 moons.

Since then, these spacecraft have continued to travel farther away from us. Voyager 1 and 2 are now so far away that they are in interstellar space —the region between the stars. No other spacecraft have ever flown this far away.

Where will Voyager go next?

Watch this video to find out what's beyond our solar system!

Both spacecraft are still sending information back to Earth. This data will help us learn about conditions in the distant solar system and interstellar space.

The Voyagers have enough fuel and power to operate until 2025 and beyond. Sometime after this they will not be able to communicate with Earth anymore. Unless something stops them, they will continue to travel on and on, passing other stars after many thousands of years.

Each Voyager spacecraft also carries a message. Both spacecraft carry a golden record with scenes and sounds from Earth. The records also contain music and greetings in different languages. So, if intelligent life ever find these spacecraft, they may learn something about Earth and us as well!

A photo of the golden record that was sent into space on both Voyager 1 and Voyager 2. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

More about our universe!

Where does interstellar space begin?

Searching for other planets like ours

Play Galactic Explorer!

If you liked this, you may like:

How Do We Know When Voyager Reaches Interstellar Space?

Why the debate about if and when Voyager 1 reached interstellar space is so complicated.

"We have been cautious because we're dealing with one of the most important milestones in the history of exploration," said Voyager Project Scientist Ed Stone of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. "Only now do we have the data -- and the analysis -- we needed."

Basically, the team needed more data on plasma, which is ionized gas, the densest and slowest moving of charged particles in space. (The glow of neon in a storefront sign is an example of plasma.) Plasma is the most important marker that distinguishes whether Voyager 1 is inside the solar bubble, known as the heliosphere, which is inflated by plasma that streams outward from our sun, or in interstellar space and surrounded by material ejected by the explosion of nearby giant stars millions of years ago. Adding to the challenge: they didn't know how they'd be able to detect it.

"We looked for the signs predicted by the models that use the best available data, but until now we had no measurements of the plasma from Voyager 1," said Stone. Scientific debates can take years, even decades to settle, especially when more data are needed. It took decades, for instance, for scientists to understand the idea of plate tectonics, the theory that explains the shape of Earth's continents and the structure of its sea floors. First introduced in the 1910s, continental drift and related ideas were controversial for years. A mature theory of plate tectonics didn't emerge until the 1950s and 1960s. Only after scientists gathered data showing that sea floors slowly spread out from mid-ocean ridges did they finally start accepting the theory. Most active geophysicists accepted plate tectonics by the late 1960s, though some never did. Voyager 1 is exploring an even more unfamiliar place than our Earth's sea floors -- a place more than 11 billion miles (17 billion kilometers) away from our sun. It has been sending back so much unexpected data that the science team has been grappling with the question of how to explain all the information. None of the handful of models the Voyager team uses as blueprints have accounted for the observations about the transition between our heliosphere and the interstellar medium in detail. The team has known it might take months, or longer, to understand the data fully and draw their conclusions. "No one has been to interstellar space before, and it's like traveling with guidebooks that are incomplete," said Stone. "Still, uncertainty is part of exploration. We wouldn't go exploring if we knew exactly what we'd find." The two Voyager spacecraft were launched in 1977 and, between them, had visited Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune by 1989. Voyager 1's plasma instrument, which measures the density, temperature and speed of plasma, stopped working in 1980, right after its last planetary flyby. When Voyager 1 detected the pressure of interstellar space on our heliosphere in 2004, the science team didn't have the instrument that would provide the most direct measurements of plasma. Instead, they focused on the direction of the magnetic field as a proxy for source of the plasma. Since solar plasma carries the magnetic field lines emanating from the sun and interstellar plasma carries interstellar magnetic field lines, the directions of the solar and interstellar magnetic fields were expected to differ. Most models told the Voyager science team to expect an abrupt change in the magnetic field direction as Voyager switched from the solar magnetic field lines inside our solar bubble to those in interstellar space. The models also said to expect the levels of charged particles originating from inside the heliosphere to drop and the levels of galactic cosmic rays, which originate outside the heliosphere, to jump. In May 2012, the number of galactic cosmic rays made its first significant jump, while some of the inside particles made their first significant dip. The pace of change quickened dramatically on July 28, 2012. After five days, the intensities returned to what they had been. This was the first taste of a new region, and at the time Voyager scientists thought the spacecraft might have briefly touched the edge of interstellar space. By Aug. 25, when, as we now know, Voyager 1 entered this new region for good, all the lower-energy particles from inside zipped away. Some inside particles dropped by more than a factor of 1,000 compared to 2004. The levels of galactic cosmic rays jumped to the highest of the entire mission. These would be the expected changes if Voyager 1 had crossed the heliopause, which is the boundary between the heliosphere and interstellar space. However, subsequent analysis of the magnetic field data revealed that even though the magnetic field strength jumped by 60 percent at the boundary, the direction changed less than 2 degrees. This suggested that Voyager 1 had not left the solar magnetic field and had only entered a new region, still inside our solar bubble, that had been depleted of inside particles. Then, in April 2013, scientists got another piece of the puzzle by chance. For the first eight years of exploring the heliosheath, which is the outer layer of the heliosphere, Voyager's plasma wave instrument had heard nothing. But the plasma wave science team, led by Don Gurnett and Bill Kurth at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, had observed bursts of radio waves in 1983 to 1984 and again in 1992 to 1993. They deduced these bursts were produced by the interstellar plasma when a large outburst of solar material would plow into it and cause it to oscillate. It took about 400 days for such solar outbursts to reach interstellar space, leading to an estimated distance of 117 to 177 AU (117 to 177 times the distance from the sun to the Earth) to the heliopause. They knew, though, that they would be able to observe plasma oscillations directly once Voyager 1 was surrounded by interstellar plasma. Then on April 9, 2013, it happened: Voyager 1's plasma wave instrument picked up local plasma oscillations. Scientists think they probably stemmed from a burst of solar activity from a year before, a burst that has become known as the St. Patrick's Day Solar Storms. The oscillations increased in pitch through May 22 and indicated that Voyager was moving into an increasingly dense region of plasma. This plasma had the signatures of interstellar plasma, with a density more than 40 times that observed by Voyager 2 in the heliosheath. Gurnett and Kurth began going through the recent data and found a fainter, lower-frequency set of oscillations from Oct. 23 to Nov. 27, 2012. When they extrapolated back, they deduced that Voyager had first encountered this dense interstellar plasma in August 2012, consistent with the sharp boundaries in the charged particle and magnetic field data on August 25. Stone called three meetings of the Voyager team. They had to decide how to define the boundary between our solar bubble and interstellar space and how to interpret all the data Voyager 1 had been sending back. There was general agreement Voyager 1 was seeing interstellar plasma, based on the results from Gurnett and Kurth, but the sun still had influence. One persisting sign of solar influence, for example, was the detection of outside particles hitting Voyager from some directions more than others. In interstellar space, these particles would be expected to hit Voyager uniformly from all directions. "Now that we had actual measurements of the plasma environment - by way of an unexpected outburst from the sun - we had to reconsider why there was still solar influence on the magnetic field and plasma in interstellar space," Stone said. "The path to interstellar space has been a lot more complicated than we imagined." Stone discussed with the Voyager science group whether they thought Voyager 1 had crossed the heliopause. What should they call the region were Voyager 1 is? "In the end, there was general agreement that Voyager 1 was indeed outside in interstellar space," Stone said. "But that location comes with some disclaimers - we're in a mixed, transitional region of interstellar space. We don't know when we'll reach interstellar space free from the influence of our solar bubble." So, would the team say Voyager 1 has left the solar system? Not exactly - and that's part of the confusion. Since the 1960s, most scientists have defined our solar system as going out to the Oort Cloud, where the comets that swing by our sun on long timescales originate. That area is where the gravity of other stars begins to dominate that of the sun. It will take about 300 years for Voyager 1 to reach the inner edge of the Oort Cloud and possibly about 30,000 years to fly beyond it. Informally, of course, "solar system" typically means the planetary neighborhood around our sun. Because of this ambiguity, the Voyager team has lately favored talking about interstellar space, which is specifically the space between each star's realm of plasma influence. "What we can say is Voyager 1 is bathed in matter from other stars," Stone said. "What we can't say is what exact discoveries await Voyager's continued journey. No one was able to predict all of the details that Voyager 1 has seen. So we expect more surprises." Voyager 1, which is working with a finite power supply, has enough electrical power to keep operating the fields and particles science instruments through at least 2020, which will mark 43 years of continual operation. At that point, mission managers will have to start turning off these instruments one by one to conserve power, with the last one turning off around 2025. Voyager 1 will continue sending engineering data for a few more years after the last science instrument is turned off, but after that it will be sailing on as a silent ambassador. In about 40,000 years, it will be closer to the star AC +79 3888 than our own sun. (AC +79 3888 is traveling toward us faster than we are traveling towards it, so while Alpha Centauri is the next closest star now, it won't be in 40,000 years.) And for the rest of time, Voyager 1 will continue orbiting around the heart of the Milky Way galaxy, with our sun but a tiny point of light among many. The Voyager spacecraft were built and continue to be operated by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in Pasadena, Calif. Caltech manages JPL for NASA. The Voyager missions are a part of NASA's Heliophysics System Observatory, sponsored by the Heliophysics Division of the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. For more information about Voyager, visit: http://www.nasa.gov/voyager and http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov .

News Media Contact

Jia-Rui Cook

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-354-0724

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Voyager 1, First Craft in Interstellar Space, May Have Gone Dark

The 46-year-old probe, which flew by Jupiter and Saturn in its youth and inspired earthlings with images of the planet as a “Pale Blue Dot,” hasn’t sent usable data from interstellar space in months.

By Orlando Mayorquin

When Voyager 1 launched in 1977, scientists hoped it could do what it was built to do and take up-close images of Jupiter and Saturn. It did that — and much more.

Voyager 1 discovered active volcanoes, moons and planetary rings, proving along the way that Earth and all of humanity could be squished into a single pixel in a photograph, a “ pale blue dot, ” as the astronomer Carl Sagan called it. It stretched a four-year mission into the present day, embarking on the deepest journey ever into space.

Now, it may have bid its final farewell to that faraway dot.

Voyager 1 , the farthest man-made object in space, hasn’t sent coherent data to Earth since November. NASA has been trying to diagnose what the Voyager mission’s project manager, Suzanne Dodd, called the “most serious issue” the robotic probe has faced since she took the job in 2010.

The spacecraft encountered a glitch in one of its computers that has eliminated its ability to send engineering and science data back to Earth.

The loss of Voyager 1 would cap decades of scientific breakthroughs and signal the beginning of the end for a mission that has given shape to humanity’s most distant ambition and inspired generations to look to the skies.

“Scientifically, it’s a big loss,” Ms. Dodd said. “I think — emotionally — it’s maybe even a bigger loss.”

Voyager 1 is one half of the Voyager mission. It has a twin spacecraft, Voyager 2.

Launched in 1977, they were primarily built for a four-year trip to Jupiter and Saturn , expanding on earlier flybys by the Pioneer 10 and 11 probes.

The Voyager mission capitalized on a rare alignment of the outer planets — once every 175 years — allowing the probes to visit all four.

Using the gravity of each planet, the Voyager spacecraft could swing onto the next, according to NASA .

The mission to Jupiter and Saturn was a success.

The 1980s flybys yielded several new discoveries, including new insights about the so-called great red spot on Jupiter, the rings around Saturn and the many moons of each planet.

Voyager 2 also explored Uranus and Neptune , becoming in 1989 the only spacecraft to explore all four outer planets.

Voyager 1, meanwhile, had set a course for deep space, using its camera to photograph the planets it was leaving behind along the way. Voyager 2 would later begin its own trek into deep space.

“Anybody who is interested in space is interested in the things Voyager discovered about the outer planets and their moons,” said Kate Howells, the public education specialist at the Planetary Society, an organization co-founded by Dr. Sagan to promote space exploration.

“But I think the pale blue dot was one of those things that was sort of more poetic and touching,” she added.

On Valentine’s Day 1990, Voyager 1, darting 3.7 billion miles away from the sun toward the outer reaches of the solar system, turned around and snapped a photo of Earth that Dr. Sagan and others understood to be a humbling self-portrait of humanity.

“It’s known the world over, and it does connect humanity to the stars,” Ms. Dodd said of the mission.

She added: “I’ve had many, many many people come up to me and say: ‘Wow, I love Voyager. It’s what got me excited about space. It’s what got me thinking about our place here on Earth and what that means.’”

Ms. Howells, 35, counts herself among those people.

About 10 years ago, to celebrate the beginning of her space career, Ms. Howells spent her first paycheck from the Planetary Society to get a Voyager tattoo.

Though spacecraft “all kind of look the same,” she said, more people recognize the tattoo than she anticipated.

“I think that speaks to how famous Voyager is,” she said.

The Voyagers made their mark on popular culture , inspiring a highly intelligent “Voyager 6” in “Star Trek: The Motion Picture” and references on “The X Files” and “The West Wing.”

Even as more advanced probes were launched from Earth, Voyager 1 continued to reliably enrich our understanding of space.

In 2012, it became the first man-made object to exit the heliosphere, the space around the solar system directly influenced by the sun. There is a technical debate among scientists around whether Voyager 1 has actually left the solar system, but, nonetheless, it became interstellar — traversing the space between stars.

That charted a new path for heliophysics, which looks at how the sun influences the space around it. In 2018, Voyager 2 followed its twin between the stars.

Before Voyager 1, scientific data on the sun’s gases and material came only from within the heliosphere’s confines, according to Dr. Jamie Rankin, Voyager’s deputy project scientist.

“And so now we can for the first time kind of connect the inside-out view from the outside-in,” Dr. Rankin said, “That’s a big part of it,” she added. “But the other half is simply that a lot of this material can’t be measured any other way than sending a spacecraft out there.”

Voyager 1 and 2 are the only such spacecraft. Before it went offline, Voyager 1 had been studying an anomalous disturbance in the magnetic field and plasma particles in interstellar space.

“Nothing else is getting launched to go out there,” Ms. Dodd said. “So that’s why we’re spending the time and being careful about trying to recover this spacecraft — because the science is so valuable.”

But recovery means getting under the hood of an aging spacecraft more than 15 billion miles away, equipped with the technology of yesteryear. It takes 45 hours to exchange information with the craft.

It has been repeated over the years that a smartphone has hundreds of thousands of times Voyager 1’s memory — and that the radio transmitter emits as many watts as a refrigerator lightbulb.

“There was one analogy given that is it’s like trying to figure out where your cursor is on your laptop screen when your laptop screen doesn’t work,” Ms. Dodd said.

Her team is still holding out hope, she said, especially as the tantalizing 50th launch anniversary in 2027 approaches. Voyager 1 has survived glitches before, though none as serious.

Voyager 2 is still operational, but aging. It has faced its own technical difficulties too.

NASA had already estimated that the nuclear-powered generators of both spacecrafts would likely die around 2025.

Even if the Voyager interstellar mission is near its end, the voyage still has far to go.

Voyager 1 and its twin, each 40,000 years away from the next closest star, will arguably remain on an indefinite mission.

“If Voyager should sometime in its distant future encounter beings from some other civilization in space, it bears a message,” Dr. Sagan said in a 1980 interview .

Each spacecraft carries a gold-plated phonograph record loaded with an array of sound recordings and images representing humanity’s richness, its diverse cultures and life on Earth.

“A gift across the cosmic ocean from one island of civilization to another,” Dr. Sagan said.

Orlando Mayorquin is a general assignment and breaking news reporter based in New York. More about Orlando Mayorquin

What’s Up in Space and Astronomy

Keep track of things going on in our solar system and all around the universe..

Never miss an eclipse, a meteor shower, a rocket launch or any other 2024 event that’s out of this world with our space and astronomy calendar .

Scientists may have discovered a major flaw in their understanding of dark energy, a mysterious cosmic force . That could be good news for the fate of the universe.

A new set of computer simulations, which take into account the effects of stars moving past our solar system, has effectively made it harder to predict Earth’s future and reconstruct its past.

Dante Lauretta, the planetary scientist who led the OSIRIS-REx mission to retrieve a handful of space dust , discusses his next final frontier.

A nova named T Coronae Borealis lit up the night about 80 years ago. Astronomers say it’s expected to put on another show in the coming months.

Is Pluto a planet? And what is a planet, anyway? Test your knowledge here .

An illustration shows the position of NASA's Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 probes outside of the heliosphere, a protective bubble created by the sun that extends well past the orbit of Pluto.

Interstellar space even weirder than expected, NASA probe reveals

The spacecraft is just the second ever to venture beyond the boundary that separates us from the rest of the galaxy.

In the blackness of space billions of miles from home, NASA’s Voyager 2 marked a milestone of exploration, becoming just the second spacecraft ever to enter interstellar space in November 2018. Now, a day before the anniversary of that celestial exit, scientists have revealed what Voyager 2 saw as it crossed the threshold—and it’s giving humans new insight into some of the big mysteries of our solar system.

The findings, spread across five studies published today in Nature Astronomy , mark the first time that a spacecraft has directly sampled the electrically charged hazes, or plasmas, that fill both interstellar space and the solar system’s farthest outskirts. It’s another first for the spacecraft, which was launched in 1977 and performed the first—and only—flybys of the ice giant planets Uranus and Neptune. ( Find out more about the Voyager probes’ “grand tour”—and why it almost didn’t happen .)

See pictures from Voyager 2's solar system tour

Voyager 2’s charge into interstellar space follows that of sibling Voyager 1, which accomplished the same feat in 2012. The two spacecrafts’ data have many features in common, such as the overall density of the particles they’ve encountered in interstellar space. But intriguingly, the twin craft also saw some key differences on their way out—raising new questions about our sun’s movement through the galaxy.

“This has really been a wonderful journey,” Voyager project scientist Ed Stone , a physicist at Caltech, said in a press briefing last week.

“It’s just really exciting that humankind is interstellar,” adds physicist Jamie Rankin , a postdoctoral researcher at Princeton University who wasn’t involved with the studies. “We have been interstellar travelers since Voyager 1 crossed, but now, Voyager 2’s cross is even more exciting, because we can now compare two very different locations ... in the interstellar medium.”

Inside the bubble

To make sense of Voyager 2’s latest findings, it helps to know that the sun isn’t a quietly burning ball of light. Our star is a raging nuclear furnace hurtling through the galaxy at about 450,000 miles an hour as it orbits the galactic center.

FREE BONUS ISSUE

The sun is also rent through with twisted, braided magnetic fields and, as a result, its surface constantly throws off a breeze of electrically charged particles called the solar wind. This gust rushes out in all directions, carrying the sun’s magnetic field with it. Eventually, the solar wind smashes into the interstellar medium, the debris from ancient stellar explosions that lurks in the spaces between stars.

Like oil and water, the solar wind and the interstellar medium don’t perfectly mix, so the solar wind forms a bubble within the interstellar medium called the heliosphere. Based on Voyager data, this bubble extends about 11 billion miles from the sun at its leading edge, surrounding the sun, all eight planets, and much of the outer objects orbiting our star. Good thing, too: The protective heliosphere shields everything inside it, including our fragile DNA, from most of the galaxy’s highest-energy radiation.

The heliosphere’s outermost edge, called the heliopause, marks the start of interstellar space. Understanding this threshold has implications for our picture of the sun’s journey through the galaxy, which in turn can tell us more about the situations of other stars scattered across the cosmos.

“We are trying to understand the nature of that boundary, where these two winds collide and mix,” Stone said during the briefing. “How do they mix, and how much spillage is there from inside to outside the bubble, and from outside the bubble to inside?”

Scientists got their first good look at the heliopause on August 25, 2012, when Voyager 1 first entered interstellar space. What they began to see left them scratching their heads. For instance, researchers now know that the interstellar magnetic field is about two to three times stronger than expected, which means, in turn, that interstellar particles exert up to ten times as much pressure on our heliosphere than previously thought.

“It is our first platform to actually experience the interstellar medium, so it is quite literally a pathfinder for us,” says heliophysicist Patrick Koehn , a program scientist at NASA headquarters.

You May Also Like

A supersonic jet chased a solar eclipse across Africa—for science

2024 may bring the best auroras in 20 years

Inflammation isn't always bad. Here's how we can use it to heal.

Leaky boundary.

But for all that Voyager 1 upended expectations, its revelations were incomplete. Back in 1980, its instrument that measured the temperature of plasmas stopped working. Voyager 2’s plasma instrument is still working just fine, though, so when it crossed the heliopause on November 5, 2018, scientists could get a much better look at this border.

For the first time, researchers could see that as an object gets within 140 million miles of the heliopause, the plasma surrounding it slows, heats up, and gets more dense. And on the other side of the boundary, the interstellar medium is at least 54,000 degrees Fahrenheit, which is hotter than expected. However, this plasma is so thin and diffuse, the average temperature around the Voyager probes remains extremely cold.

In addition, Voyager 2 confirmed that the heliopause is one leaky border—and the leaks go both ways. Before Voyager 1 passed through the heliopause, it zoomed through tendrils of interstellar particles that had punched into the heliopause like tree roots through rock. Voyager 2, however, saw a trickle of low-energy particles that extended more than a hundred million miles beyond the heliopause.

Another mystery appeared as Voyager 1 came within 800 million miles of the heliopause, where it entered a limbo-like area in which the outbound solar wind slowed to a crawl. Before it crossed the heliopause, Voyager 2 saw the solar wind form an altogether different kind of layer that, oddly, was nearly the same width as the stagnant one seen by Voyager 1.

“That is very, very weird,” Koehn says. “It really shows us that we need more data.”

Interstellar sequel?

Solving these puzzles will require a better view of the heliosphere as a whole. Voyager 1 exited near the heliosphere’s leading edge, where it collides with the interstellar medium, and Voyager 2 exited along its left flank. We have no data on the heliosphere’s wake, so its overall shape remains a mystery. The interstellar medium’s pressure might keep the heliosphere roughly spherical, but it’s also possible that it has a tail like a comet—or that it is shaped like a croissant .

But while other spacecraft are currently outward bound, they won’t be able to return data from the heliopause. NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft is zooming out of the solar system at more than 31,000 miles an hour , and when it runs out of power in the 2030s, it’ll fall silent more than a billion miles short of the heliosphere’s outer edge. That’s why Voyager scientists and others are calling for a follow-up interstellar probe . The goal: a 50-year, multi-generation mission that explores the outer solar system on its way into unexplored regions beyond the solar wind.

“Here's an entire bubble, [and] we only crossed it with two points,” study coauthor Stamatios Krimigis , the emeritus head of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory's space department, said at the briefing. “Two examples are not enough.”

A new generation of scientists is eager to run with the baton—including Rankin, who did her Ph.D. at Caltech with Voyager 1’s interstellar data with Stone as her adviser.

“It was amazing to work on this cutting-edge data from spacecraft that were launched before I was born and still doing amazing science,” she says. “I’m just really thankful for all the people who have spent so much time on Voyager.”

Related Topics

- SPACE EXPLORATION

U.S. returns to the moon as NASA's Odysseus successfully touches down

Why go back to the moon? NASA’s Artemis program has even bigger ambitions