Advertisement

Sustainable Tourism as a Driving force of the Tourism Industry in a Post-Covid-19 Scenario

- Original Research

- Published: 12 June 2021

- Volume 158 , pages 991–1011, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Beatriz Palacios-Florencio ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2789-7914 1 ,

- Luna Santos-Roldán 2 ,

- Juan Manuel Berbel-Pineda 1 &

- Ana María Castillo-Canalejo 2

17k Accesses

39 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The tourism industry is probably one of the most affected by the crisis caused by Covid-19. It is the responsibility of politicians, tourism professionals and researchers to look for solutions to revive this important industry. This article shows how the development of Sustainable Tourism can help in the sustenance of the tourism industry, since one of the premises on which Sustainable Tourism is based is the non-overcrowding of tourist destinations (essential factor in the current context). Considering this argument and the existing regulations on lockdown rules, social distancing and meet up, it is considered that the practices in Sustainable Tourism can become a potential solution to stimulate tourist movements and help the revival of the tourism industry. Therefore, more specifically, the main objective of this article is to know tourist´s perception among about Sustainable Tourism and to determine which factors help its development. In this sense, the use of structural equation models in a research of 308 tourists has determined how factors related to the tourists’ attitude, motivation and perceived benefits provided by the development of Sustainable Tourism increase the intention to consume this type of tourism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Sustainable Tourism in Europe from Tourists’ Perspectives

Sustainable Tourism and Degrowth: Searching for a Path to Societal Well-Being

Sustainable Tourism; Vector of the Social and Solidarity Economy: Case of Region Souss Massa, South of Morocco

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

It is widely accepted that one of the aspects considered by Sustainable Tourism is the fight against overcrowding in certain tourist destinations and avoid damages associated (eg. Jurowski & Gursoy, 2004 ; Santana-Jiménez & Hernández, 2011 ). In fact, Sustainable Tourism has been trying (for years) to place itself as a solution to the negative aspects that involve tourism in its development and to the criticism it frequently receives (Sharpley, 2020 ). And it is now, in this context, that this perception makes more sense than ever before.

The massification of tourist destinations and the damage this causes (both in cities and to natural environments), is one of the fiercest criticisms levelled at tourism. In this sense, Sustainable Tourism is based, among other things, on promoting and developing less massified tourist destinations or Sustainable Mass Tourism as the desired impending outcome for most destinations. In relation to this, the research of Weaver ( 2012 ) highlights the concept of Sustainable Mass Tourism as an emerging tourism state—something that can be convenient reconsidered in the current situation-. According to this author, this type of tourism is perceived as a desired outcome for destinations with a focus on sustainability and indicates three convergent developmental trajectories: organic, incremental and induced.

On the other hand, we would like to point out that, among the measures being taken to combat Covid-19, restrictions on meetings and social distancing measures stand out (World Health Organization, 2020 ). And, why are these measures being referred to here? The explanation is simple, as this paper takes as the basis the fight against overcrowding in tourist destinations; relating it to the measures adopted (nearly worldwide), due to the social distancing caused by Covid-19. In fact, this measure, together with the tourist's perception of fear of travelling, are the ingredients for preventing overcrowded destinations, and therefore strenght Sutainable Tourism.

Therefore, it can be stated that tourism industry is highly sensitive to significant shocks like the Covid-19 pandemic (Chang et al., 2020 ). In other words, tourism is particularly susceptible to measures to counter pandemics due to restricted mobility and social distancing. This leads to global travel restrictions (which are unprecedented) that, together with confinement, are causing the most severe disruption to the global economy in recent decades (Gössling et al., 2020 ). According to the declarations made by the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) on its website, on April, 96% of worldwide destinations have implemented travel restrictions. Around 40 destinations are experiencing a partial border closure, while 90 destinations have closed totally their borders. An unforeseen and, for the time being, unpredictable situation that urges survival measures for the sector.

Given this current scenario, Sustainable Tourism may find a great opportunity for its development (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020 ; Petrizzo, 2020 ). Indeed, this article focuses primarily on determining factors focuses on the tourist's perception for promoting Sustainable Tourism.

The UNWTO defined in 2005 the concept of Sustainable Tourism as “ one whose practices and principles can be applicable to all forms of tourism in all types of destinations, including mass tourism and the various niche tourism segments ”. Sustainability principles refer to the environmental, economic, and socio-cultural aspects of tourism development, and a suitable balance must be established between these three dimensions to guarantee its long-term sustainability (UNWTO, 2005 ). In addition to international organizations, we also find many authors who have defined the concept of Sustainable Tourism (Higgins-Desbiolles et al., 2019 ; Hussain, et al., 2015 ; Mohaidin, et al., 2017 ). Conversely, despite the fact that Sustainable Tourism has been recognized in business practice in many destinations, the volume of academic research has not been as large as it deserves (Ruhanen et al., 2015 ). From the start, the development of Sustainable Tourism is based on the preservation of the environment (Ciacci et al., 2021 ), the cultural authenticity and the democratic profitability of the tourist activity in destination (Crosby, 1996 ). It is only this tourism that recognizes the priority place of social return, as an index of well-being reversed on the visited destination; and also the exclusively economic return, that is, whether the tourist activity generates sufficient income for the local population, in terms of employment, wealth and available resources (Fernández, 2018 ).

The purpose of this study is to identify the factors that help the development of Sustainable Tourism (from a tourist's perception point of view), since a greater use of this type of tourism could help the revival of the tourism industry. In this sense, and considering the guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO), the different governments in all countries recommend avoiding large concentrations of people (which favors the development of this type of tourism).

However, in generic terms, tourism implies people concentration, and even more so in those destinations considered as “overcrowded”: large cities, charming cities, main beach locations, amusement parks, airports, etc. That is why, under the conditions exposed, it is necessary to combat the social, economic, financial and cultural consequences of a pandemic, which entails a challenge for the tourism sector, that requires a careful assessment of its impact dimensions, as well as a reconsideration of a new hitherto unknown approach. Thus, the development of tourism as it is currently known will change in the coming years, which will have serious repercussions on the profitability of tourism industry (Hancock, 2020 ).

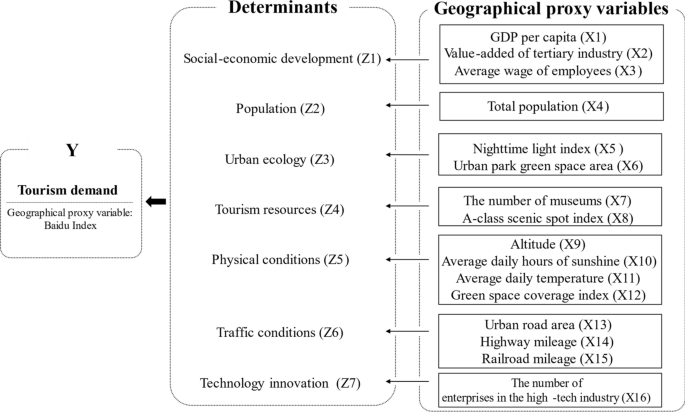

Henceforth, this study gives an assessment of Sustainable Tourism and the variables that enable accelerated development (which becomes more necessary in this crisis context in tourism industry). The theoretical frame study analyzes the factors of perceived quality, motivation, attitude, and satisfaction as attributes with a potential influence on the intention of choosing this kind of tourism. Consequently, the study is based on literature focused on consumer behavior based on their perception. However, the main contribution of this study is not theoretical (since there is a lot of literature based on this approach). The main contribution lies in extracting all the positive aspects that sustainable tourism brings to tourism development and highlighting its value in these times of crisis that this industry is going through.

2 Theorical Background

2.1 the relation between positive impacts and the attitude towards the development of sustainable tourism, the perception of service quality and motivation.

Most research conclude that the three basic categories of benefits and costs that affect to a community which receives tourists are economic, environmental, and social (Chi-Ming et al., 2017 ; Gee et al., 1989 ; Gunn, 1988 ; Gursoy et al., 2000 ; Gursoy et al., 2002 ; Murphy, 1985 ; Nunkoo & So, 2015 ; Palacios-Florencio et al., 2018 ; Vargas, 2007 ).

The economic benefits of tourism development are usually translated into employment opportunities (Belisle & Hoy, 1980 ; Davis et al., 1988 ; Ritchie, 1988 ; Tyrrell and Spaulding, 1984 ; Tosum, 2002 ; Var et al., 1985 ), income derivatives of the tourism sector (Davies et al., 1988 ; Lankford, 1994 ; Jurowski et al., 1997 ; Murphy, 1983 ; Tyrrel and Spaulding, 1984 ) and investment and business opportunities (Davis et al., 1988 ; Sethna & Richmond, 1978 ).

Regarding the social impact of tourism, it can be conceived as changes in the people lives residing in the communities that are part of the destination and related to tourism activity (Mathieson & Wall, 1982 ). Likewise, the social and cultural benefits (Besculides et al., 2002 ) translate into an increase in leisure activities (Keogh, 1990 ; Liu et al., 1987 ; Murphy, 1983 ; Pizam, 1978 ; Rothman, 1978 ; Sheldom and Var, 1984 ), the improvement of public services and infrastructures (Pizam, 1978 ; Sethna & Richmond, 1978 ) and the instigating effect on social change (Harrison, 1992 ). Between its benefits, tourism increases cultural identity and pride, the cohesion and the exchange of ideas, improves knowledge of the area culture (Esman, 1984 ), creates opportunities for cultural exchange, revitalizes local traditions, increases the quality of life and improves the image of the community (Besculides et al., 2002 ).

Similarly, in the environmental field, tourism may be the reason to protect natural resources and conserve homogeneous urban designs (Díaz & Gutiérrez, 2010 ), so that it can be possible to promote an ordered tourist development based on a model integrated in the environment. Miller et al., ( 2014 ) refer to the concept of pro-environmental behaviour, understood as the actions for protecting the environment, while tourists´ pro-environmental behaviour were connected to nature-based tourism and ecotourism. Ciacci et al., ( 2021 ) adds to the environmental factor, logistical and infrastructural dimension. While it is true that environmental quality can be composed by objective and subjective components, it has been widely accepted that a good link between environmental protection, logistic and infrastructural development is seen as fundamental for a successful Sustainable Tourism development strategy.

The notion of sustainable development is a relatively recent concept, first defined in 1987 in the Brundtland report by the UN. This report, also called “Our Common Future”, declares that sustainable development tries to “meet the needs of the present generation without the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (CMMAD, 1992 : 67).

Following the arrival of the concept of sustainable development in 1987 with the aforementioned Brundtland report, it was applied to the tourism field.

This type of tourism weights the importance of stakeholders and, although the key role of residents is recognized (Gursoy et al., 2018 ; Stylidis et al., 2014 ), it is also interesting to analyze the perspective of the tourists themselves. Indeed, knowing the attitudes of tourists towards the development of Sustainable Tourism and raising culture, environment and economy awareness of the communities visited are vital factors to protect tourist destinations and reduce negative impacts (Othman et al., 2010 ).

On the other hand, most studies report a positive relation between the attitude towards Sustainable Tourism development and the perception of its positive impacts (Andereck & Vogt, 2000 ; Byrd et al., 2009 ; Chi-Ming et al., 2017 ; Ekanayake & Long, 2012 ; Hussain, et al., 2015 ; Pavlić et al., 2017 ; Su & Chang, 2017 ). The provision of high quality and environmentally friendly services has been identified as an important factor for the success of a tourist destination (Miller et al., 2014 ).

Service quality is defined as the level of satisfaction an event or experience produces according to individual needs or expectations (Michael, 2013 ). Mukhles ( 2013 ) proposes five main components to analyze the quality of the tourist service: attractions and neighborhoods, facilities and services, accessibility, destination image, and pricing. The attractions and neighborhoods of the destination are elements that largely determine the choice of tourists and motivate the visit to this destination, include both natural and artificial attractions. The facilities and services include accommodation, restaurants, transportation, sports or other activities and tourist sale points. Accessibility includes elements related to transport and its infrastructure. The destination image is the subjective interpretation of reality by the tourist and, the fifth component, the price enables to measure the quality of the different services. On the other hand, Mohaidin et al. ( 2017 ) considers other attributes that should be taken into account: the environment safety and harmony and the ability to perform the promised service in a reliable and accurate way. Hence, the following model hypotheses are raised:

Tourism motivation is a driving force that motivates people to go on holiday or visit destinations. Beerli and Martin ( 2004 ) describe the motivation to travel as an internal need that drives an individual to act in a certain way to achieve his desired satisfaction. Yoon and Uysal ( 2005 ) found that motivation is the most important factor that increases satisfaction together with the services and the loyalty to a destination. In addition to being the most important factor in predicting tourism behavior, motivation to travel also significantly influences the understanding of the intentions of tourist visits (Li et al., 2010 ; Mohaidin, et al., 2017 ).

The motivation to travel to a destination will be higher whether the tourist is aware of the positive impacts that Sustainable Tourism can have on there (Crouch & Ritchie, 1999 ). From this information, the following hypothesis of this study is proposed:

2.2 The Relation Between the Attitude Towards the Development of Sustainable Tourism and the Intention to Choose a Sustainable Tourist Destination

Intention can be defined as a stated probability of engaging in a certain behavior (Oliver, 1997 ). Efforts to recognize and attract the right visitors are crucial in ensuring Sustainable Tourism. Behavioral intentions represent a vital issue in the field of tourism, since it is necessary to know and understand the tourist loyalty, i.e. the factors that influence positive intentions towards a destination (Mohaidin et al., 2017 ).

Ventakesh ( 2006 ) and Mohaidin, et al. ( 2017 ) point out that, among the psychological factors that affect tourists in their intention to select a sustainable tourist destination, a respectful attitude towards the environment has a positive effect. Luo and Deng ( 2008 ) verifies that people who show positive attitudes towards the environment during trips can transmit a greater desire for Sustainable Tourism experiences with nature.

Miller, et al. ( 2014 ) indicate that are several types of variables that are associated with pro-environmental behavior in the context of large mass tourism urban destinations, including individual background factors, habit, attitudes and external contextual factors. This study suggests that psychological factors such as attitudes may be more important than socio-demographic and contextual factors in determining pro-environmental behaviour in sustainable urban tourism destination.

From these statements, the following hypothesis is interpreted:

2.3 The Relation Between Motivation and Attitude Towards the Development of Sustainable Tourism

Along with satisfaction, knowing the motivations of tourists is the basis for understanding the following behavior trends (Jensen, 2015 ; Xu and Chan, 2016 ). For Wong et al. ( 2017 ), it is a two-phase process where internal and external factors converge. In this sense, the internal factors concern the desire to make the trip. Kim et al. ( 2007 ) incorporates psychological reasons such as disconnection and relaxation. For their part, external factors promote the destination choice, including cultural and unique features of the destination (Pesonen et al., 2011 ).

The tourist motivation has positive effects on their visit intention, as the commitment to the environment, nature care and conservation in the case of Sustainable Tourism development (Hunter, 2000 ). Huang and Liu ( 2017 ) apply these constructs to ecotourism to confirm that greater environment sensitivity of tourists is related to the motivation and the intention to repeat the visit. Similarly, Zhang and Lei ( 2012 ) argue that environmental knowledge and concern are directly related to the motivation and intention of a tourist visit.

2.4 The Relation Between the Perception of Service Quality and Satisfactory Experience

Understanding what factors influence tourist satisfaction is one of the most relevant research topics in the tourism sector, due to the impact it has on the success of any tourism product or service. The perceived quality is a measure that represents the quality obtained from product or service attributes and is related to the satisfaction of the customer’s needs and the product or service availability (ACSI, 2016 ).

It is widely recognized in the literature that the service quality perceived by the customer directly influences the tourist experience satisfaction (Castillo Canalejo & Jimber del Río, 2018 ; Hui et al., 2007; Mohaidin et al., 2017 ; Wu et al., 2016 ). Therefore, the following model hypothesis is formulated:

2.5 The Relation Between the Attitude Towards the Development of Sustainable Tourism and Satisfactory Experience

Experimental satisfaction goes beyond the concept of service satisfaction, taking into account it focuses on customers’ evaluations regarding their experiences once such service has been consumed (Wu et al., 2016 ). If this is applied to sustainable development in the aforementioned Brutland Report, the concept of satisfaction becomes vitally relevant. The development of Sustainable Tourism must satisfy the needs of tourists and residents at the same time that economic, socio-cultural and environmental need (UNWTO, 2005 ).

In the scientific literature, some authors (Chang & Fong, 2010 ; Kao et al., 2008 ; Wu et al., 2016 ) allude to green experiential satisfaction to refer to the clients’ general evaluations regarding their experience with respectful aspects of the environment and its expectations on the sustainable development of tourist destinations or services. From the study of these authors, the following hypothesis is based:

2.6 The Relation Between Satisfactory Experience and Intention to Choose a Sustainable Tourist Destination

Another widely recognized factor in the scientific literature that influences the intention to visit a place is satisfaction. According to Oliver ( 1980 ), it is considered as the balance of expectations and perceptions before and after the visit to a destination, whose importance lies in the ability to influence future behavior (Ohn & Supinit, 2016 ; Choo et al., 2016 ). In tourism studies, the satisfaction produced by the experience of tourist activities is especially important, as these are the most memorable and are conceived as a differentiating element from other visits (Walls et al., 2011 ).

There are numerous studies that prove the relation between tourist satisfaction and the intention of returning (Baker & Crompton, 2000 ; Beecho and Prentice 1997 ; Castillo Canalejo & Jimber del Río, 2018 ; Caneed, 2003 ; Dimitriades, 2006 ; Hallowell, 1996 ; Pizam, 1994 ; Sung, et al., 2016 ). Other authors, such as Jurdana and Frleta ( 2012 ) or Chin et al. ( 2018 ), focus on a specific type of tourism: rural tourism. From the reading of these authors, the following hypothesis is proposed:

2.7 The Relation Between Motivation and Intention to Choose a Sustainable Tourist Destination

Motivation is an individual internal factor that can affect the tourist behavior by influencing their trip valuation. This construct can be considered as a key factor in the process of selecting tourist destinations and the intention to visit (Chang et al., 2014 ; Hsu and Huang 2009 ).

In the bibliography, we find several examples of authors that demonstrate that motivation and satisfaction influence the tourist’s decision when choosing a destination (Chiu et al., 2016 ; Yoon & Uysal, 2005 ). In this sense, the study of Malaysia of Mohaidin et al. ( 2017 ) confirms that motivation positively influences the intention to choose a sustainable tourist destination, in line with the results offered by Beerli and Martin ( 2004 ), and Prebensen ( 2006 ). Based on this, the last hypothesis is proposed:

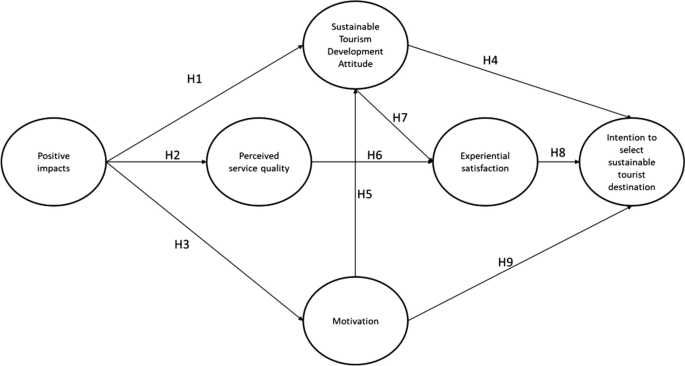

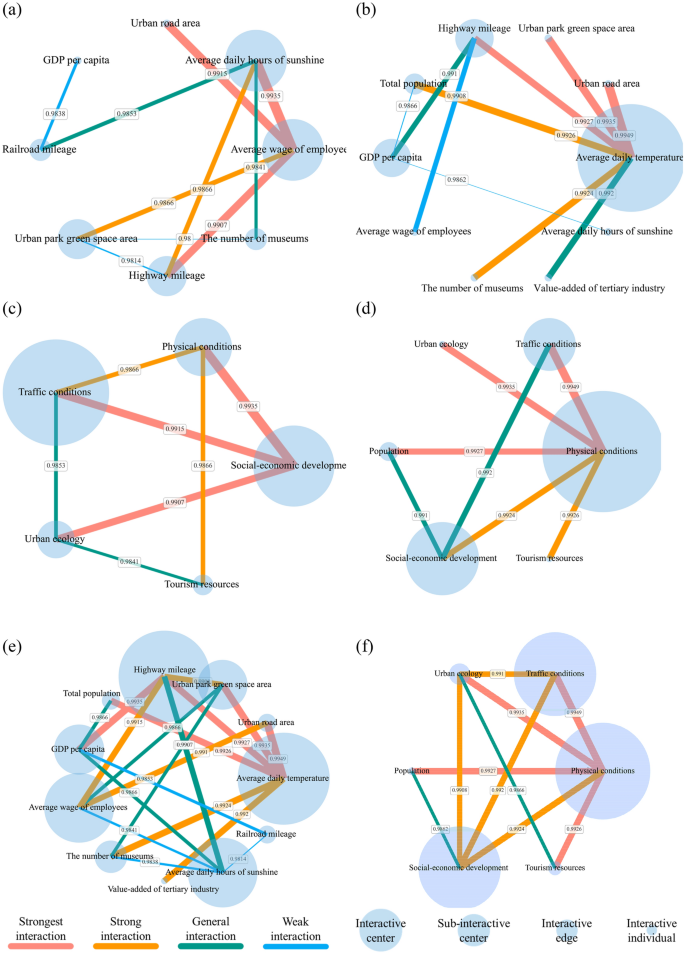

In summary, hereunder the conceptual model to be studied is shown in Fig. 1

Conceptual mode. Source Own elaboration

3 Data and Methodology

The data was collected from tourists who visited the city of Córdoba (Spain) between the months of October and November 2019. Córdoba (a World Heritage city) is one of the main cities receiving tourism (both national and international). This means that one of the main challenges that it faces is massification and the problems associated (Weaver, 2012 ). The sample included a total of 308 tourists, who received the questionnaires personally and on-site in the monumental area of the city. The questionnaires were handed out randomly to people visiting the monumental area, after requesting their collaboration and verifying that they were tourists and not simple passers-by. Despite its possible limitations, we considered this procedure to be the most appropriate for the objectives of this research. So, we have used a non-probabilistic sampling.

In relation to the instruments used, the original versions of the scales were translated with special attention into the linguistic characteristics of the population. All variables were measured on a Likert scale from 1 to 5. Where 1 = totally disagree and 5 = totally agree. The items in the questionnaire were translated and adapted for the different constructs. The items of positive socio-cultural, economic and environmental impacts were extracted and adapted from Pavlić et al. ( 2017 ), the items related to experiential satisfaction were obtained from the research carried out by Wu & Li ( 2015 ), the items of Sustainable Tourism Development Attitude were adapted from the study of Wei-San Su et al. ( 2017 ), and the constructs of “perceived service quality, intention to select sustainable tourist destination and motivation” were extracted and adapted from Mohaidin et al. ( 2017 ).

Table 1 shows the main aspects related to the respondents’ profile. It has to be emphasized that a relative equality is observed regarding the origin of the tourists surveyed. In general, these are tourists who come on holiday, own financing and, in a high percentage of cases, basing on their own decision. More than 60% of the travelers are 35 years old or more, have a stable partner (married and living as a couple), live in households based on 2 or more people and earn a monthly income of between 1000 and 2000 euros. Although the majority of the respondents stated that they were visiting this city for the first time (62.7%), a high percentage (close to 40%) repeated their destination. On average, the tourists who participated in the study stayed in the city for 2–3 days.

For the analysis of relations between the variables of the proposed model, structural equation modeling has been used, more specifically the Partial Least Squares (PLS) technique, based on variance (Roldán and Sánchez-Franco, 2012 ). We have specifically chosen this technique for the following reasons (Cepeda-Carrion and Roldan, 2004 ): (a) the better suitability of the technique for research in the social sciences (economics, business organization, marketing, etc.); (b) the absence of strict requirements on the distribution of the data; and (c) the possibility of using composite variables. The measurement model used in this study is composite and reflective (Mode A). This makes the use of traditional PLS viable (Sarstedt et al., 2016 ). We have used PLS SmartPLS 3.2.8 software (Ringle et al., 2015 ).

The use of a single questionnaire in a self-report format to obtain the data of the latent variables made it necessary to verify the existence of common variance between them. All the experts’ suggestions (Huber and Power, 1985 ; Podsakoff et al., 2003 ) on the procedural steps regarding the design of questionnaires have been followed. The different measures used were separated and, on the other hand, the anonymity of the respondents was guaranteed. The Harman test (1967) has been used to detect the existence of common influence in the responses. The results of the exploratory factor analysis show that the 40 elements of the questionnaire are grouped into a total of 12 factors, where the largest of them explains 17% of the variance. This allows us to confirm the absence of a common factor of influence between these items (Podsakoff and Organ, 1986).

The latent model perspective (MacKenzie & Royle, 2005 ; Real et al., 2006 ) was used when analyzing the relations between the different constructs of the model and its factors. And, as in any model of structural equations, both the measurement model and the structural model were validated (See table A in the appendix that includes the correlation matrix between the items of the model).

4 Results and Discussion

4.1 measurement model.

Table 2 collects both the mean and standard deviation of each element and the data necessary to begin with the validation of the measurement model: determine the reliability of the individual items. We have measured all latent variables (constructs) in mode A (reflective). It is observed that the factor loads of most of the items exceed the minimum criterion of 0.707 (Carmines and Zeller, 1979), only two elements with lower values have been maintained, although very close (0.68). These items have been taking into account after checking their level of significance via bootstrapping (5000 subsamples) and according to the suggestions made by Hair et al. ( 2017 ). 25 items of a total of 40 were removed from the original questionnaire.

The reliability of the constructs was evaluated using the composite reliability index (ρ c ) (Werts et al., 1974 ). In all cases, we observe the fulfillment of the minimum requirement: a composite reliability greater than 0.7 (Nunnally, 1978 ). Regarding convergent validity, as Table 1 illustrates, all latent variables exceed the minimum level of 0.5 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981 ) in the AVE.

The analysis of the discriminant validity of the various constructs (latent variables) has been performed based on the Fornell-Larcker criterion. The data is collected in Table 3 . The Fornell-Larcker criterion is strictly followed in all cases. This allows us to affirm the discriminant validity between the latent variables and their way of measuring them.

After validating the measurement model, the structural model can be validated.

4.2 Structural Model

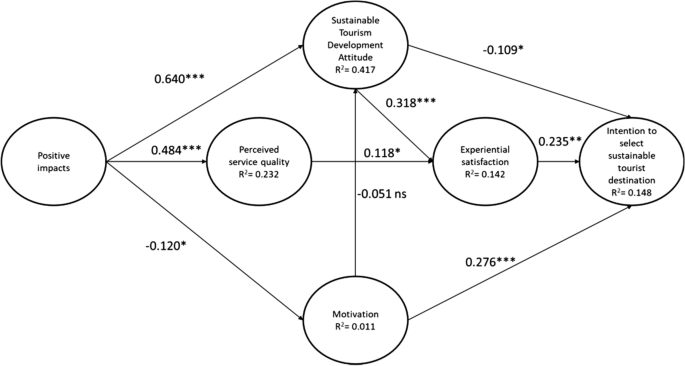

Following the indications of Roldán and Cepeda ( 2018 ), the study of the structural model must begin with the analysis of the sign, size and significance of the path coefficients, the R 2 values and the Q 2 test. According to Hair et al. ( 2017 ), we have used the bootstrapping technique with 5000 samples, to determine the t statistics and the confidence intervals and, in this way, obtain the significance of the relations. Table 4 offers the direct effects (path coefficients), the value of the t statistic, the corresponding confidence intervals and the verification of proposed hypotheses validity, along with the values of R 2 and Q 2 .

Not all direct effects are significant and positive and, therefore, the data do not indicate a widespread validity for the hypotheses proposed. 2 relations of a total of 3 are significant, but with an opposite sign to proposed one: the effect of the attitude towards the development of Sustainable Tourism on the intention to choose is negative, the same as the positive impact on the tourist motivation. Another invalid hypothesis regarding the effect of the attitude towards Sustainable Tourism on the tourist motivation is also contrary to the proposed one; although, in this case, it has no statistical significance.

The R 2 values only offer an appropriate predictive level for the variable attitude towards Sustainable Tourism development and a moderate level for the perceived service quality. The final variable intention to choose a sustainable tourist destination does not reach significant predictive levels. Besides, the Q 2 values indicate a certain level of predictive relevance of the model, since they all are greater than 0, although some of them are quite low.

In our model, we have also intended to verify whether there are mediation relations concerning the various endogenous variables included in the model. The results on mediation appear in Table 5 , where the values of all the indirect effects presented in the model are collected. The results indicate the presence of significant and positive indirect effects in total only in the case of the following relations: between the effect of the attitude towards the development of Sustainable Tourism and the intention to select a sustainable tourist destination, and between global positive impacts and the attitude towards the development of Sustainable Tourism. The model and its results are presented graphically in Fig. 2 .

Structural model: results and relations. Source Own elaboration

Once the reliability of the different items and the validity of the proposed models have been verified, we observe an absence of unanimity in the confirmation of the hypotheses proposed. Thus, in this case, the results do not match with the statements provided by some authors such as Crouch and Ritchie ( 1999 ), Lit et al. (2010) or Mohaidin et al. ( 2017 ), who confirm that the positive impacts provided by Sustainable Tourism could be a motivation for the destination. Similarly, nor does the study confirm that favorable attitudes towards the development of Sustainable Tourism positively influence on the intention to select sustainable tourist destinations, as authors such as Ventakesh ( 2006 ) or Mohaidin et al. ( 2017 ) concluded in their studys. On the other hand, although numerous studies consider the tourist motivation as a driver of their future behavior and as a positive effect trigger on the intention of visiting certain destinations, in addition to as a favorable attitude related to development of Sustainable Tourism (e.g. Huang & Liu, 2017 ), these theories are not also confirmed in this case.

The rest of the hypotheses raised in this study, related to perceived service quality, satisfaction or intention to choose sustainable tourist destinations, provide results that confirm previous studies on this topic and the relations proposed in this study.

5 Conclusions, Limitations and Future Research

5.1 conclusions.

Sustainable Tourism can become a solution to the crisis caused by COVID-19. This type of tourism promotes “greener” destinations, conceiving this term not only as ecological, but also as healthy. Therefore, the current mass many of the main tourist destinations face up today seems to stop happening soon or have to evolute to a sustainable mass tourism that combines the emergence of sustainability as a societal norm with the entrenched norm of support for growth (Weaver, 2012 ).

The different governments on spaces for coexistence not because of a greater environmental awareness instilled in tourists, but because of the obligations impose this fact and, on the other hand, because of the new requirements in terms of security tourists will impose on themselves when traveling and choosing a destination. Curiously, this crisis is going to force a change in Sustainable Tourism this summer 2020 in Spain. Once the confinement is finished, only internal tourism will be able to be developed. This adaptation will help overcome old problems: the exclusivity of “sun and sand” tourism will be faced to the fear of crowds, so that the occupation of inland destinations will increase, revitalizing unpopulated areas.

Therefore, the COVID-19 crisis should indirectly boost the long-awaited Sustainable Tourism, so necessary for environmental conservation and recovery. This type of tourism will finally have the long-expected opportunity (Petrizzo, 2020 ). This is the perfect time of the positioning of a sustainable Spanish tourism brand focused on its pre-existing competitive advantages. Furthermore, although the intention of many previous studies was demonstrating the importance of Sustainable Tourism (e. g. Chi-Ming et al., 2017 ; Ekanayake & Long, 2012 ; Fernández, 2018 ; Hussain, et al., 2015 ; Mohaidin et al., 2017 ; Vargas, 2007 ; Pavlić et al., 2017 ; Su & Chang, 2017 ), it does not succeed in establishing firmly in the tourist motivation, as this study reflects. However, the study confirms that tourists consider the Sustainable Tourism positive factors as important and manifest a favorable attitude towards its develop, particularly in the intention of selecting this destination type.

Based on the structural model proposed in this article and the results provided by its analysis, we see how the intention to select sustainable touristic destinations is supported by motivation (H9) and by the tourists’ satisfaction of developing favorable attitudes towards Sustainable Tourism (H8). Likewise, a positive and significant relationship of the tourist’s attitude towards the development of Sustainable Tourism is observed, fostered by the generic positive impact that it entails (H1). Respect to the tourist’ satisfaction experienced when consuming Sustainable Tourism, this is generated by the tourist’ attitude to develop Sustainable Tourism (H7) and by the service quality perceived on it (H6). This perceived service quality is caused by the generic positive impacts resulting from the development of Sustainable Tourism (H2). The rest of the relations established in the model (H3, H4 and H5) do not find statistical support in the results obtained.

Delving into the current approach of the Spanish tourism industry, the prospects noticed are dramatic, since this industry has a vital importance in the country, becoming the main axis of the national economic strength. Therefore, tourism experts and academics have the duty of find solutions to the crisis caused by the coronavirus. For this reason, we consider that promoting less crowded destinations and, ultimately, fostering Sustainable Tourism may be one of the solutions to this unprecedented crisis.

In summary, Sustainable Tourism can build on the momentum provided by this context of health crisis to increase a favorable attitude towards Sustainable Tourism development. Achieving this attitude will allow an increase in the tourist´s awareness, translated as the tourist´s perception of the positive impact and the satisfaction experienced with the consumption of this tourism type. The contributions that this work provides are several. In general, it highlights the convenience for Sustainable Tourism at present. It summarizes the constructs involved in the tourist's perception of Sustainable Tourism, contrary to other research focused on certain types of Sustainable Tourism. Specifically, our research model covers a total of 9 hypothesis with a new combination of constructs, in comparison to other publications with the same topic.

Public Institutions, in addition to managing the restrictions in the different territories, should also have the responsibility of developing policies for saving the tourism sector from the current crisis. Since Sustainable Tourism (as analyzed here) can help to promote tourist movements, it is the responsibility of Public Institutions to promote them. Therefore, it is important to determine the factors motivating tourists to engage in Sustainable Tourism, so that Public Institutions can also encourage its development, carrying out policies focused on the promotion and encouragement of this type of tourism.

The main contribution of this study is not theoretical (since there is a lot of literature based on this approach). The main contribution lies in extracting all the positive aspects that sustainable tourism brings to tourism development and highlighting its value in these times of crisis that this industry is going through.

5.2 Limitations

However, the main limitation we find in the present study is that the study was carried out prior to the crisis caused by COVID-19, therefore, aspects such as changes in attitudes, motivations and perceptions related to and caused by this new situation were not considered at any time. However, the study focused on analyzing the importance of Sustainable Tourism from a tourist perception approach. Without doubt, this relevance will be driven by this new situation. The second limitation derives from the non-probabilistic character of the sample, as the results obtained cannot be generalized; they do not guarantee a representation of the whole population, so that, it can be accepted a level of subjectivity.

In short, it is necessary to find formulas that boost the tourism industry. The development of Sustainable Tourism can help to mitigate the tourists’ perceived fear of visiting destinations with a large concentration of people. Therefore, can this crisis be the last great opportunity for the development of Sustainable Tourism?

5.3 Future Research

It would be very convenient to replicate this study in the future, when total mobility within the national territory begins to be allowed and the circulation of tourists is allowed internationally. Thus, for example, an aspect that was not supported in the present study is the importance of positive impacts a destination could have did not suppose a motivation for its choice. Thanks to the different government campaigns that are being recently launched with the aim of achieving positive impacts from visiting certain destinations, we think that this aspect could change due to the increased sensitivity perceived by the tourist.

ACSI (2016). www.theacsi.org/about-acsi/the-science-of-customer-satisfaction , last accessed (23/02/2017).

Andereck, K. L., & Vogt, C. A. (2000). The relationship between residents´attitudes toward tourism and tourism development options. Journal of Travel Research., 39 (1), 27–36.

Google Scholar

Baker, D. A., & Crompton, J. L. (2000). Quality satisfaction and behaviour intention. Annals of Tourism Research., 27 (3), 785–804.

Beeho, A. J., & Prentice, R. (1997). Conceptualizing the experiences of heritage tourists: a case study of new Lanark world heritage village. Tourism Management., 18 (2), 75–87.

Beerli, A., & Martin, J. D. (2004). Factors influencing destination image. Annals of Tourism Research., 31 (5), 657–681.

Belisle, F. J., & Hoy, D. R. (1980). The perceived impact of tourism by residents: a case study in Santa Marta. Columbia. Annals of Tourism Research., 7 , 83–101.

Besculides, A., Lee, M., & McCormick, P. (2002). Residents’ perceptions of the cultural benefits of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 29 , 303–319.

Byrd, E., Cardenan, D., & Dregallas, S. (2009). Differences in stakeholder attitudes of tourism development and the natural environment. E-Review of Tourism Research., 7 (2), 72–81.

Caneen, J. M. (2003). Cultural determinants of tourism intention to return. Tourism Analysis., 8 , 237–242.

Castillo Canalejo, A.M., & Jimber del Río, J.A., (2018). Quality, satisfaction and loyalty índices. Journal of Place Management and Development .

Chang, C. L., McAleer, M., & Ramos, V. (2020). A charter for sustainable tourism after COVID-19. Sustainability, 12 , 3671.

Chang, N. J., & Fong, C. M. (2010). Green product quality, green corporate image, green customer satisfaction and green customer loyalty. African Journal of Business Management., 4 (13), 2836–2844.

Chang, K.-C., Kuo, N. T., Hsu, C. L., & Cheng, Y.-S. (2014). The impact of website quality and perceived trust on customer purchase intention in the hotel sector: Website brand and perceived value as moderators. International Journal of Innovation, Management and Technology , 5 , 255–260.

Chien, C., Law, F., Lo, M., & Ramayah, T. (2018). The impact of accessibility quality and accommodation quality on tourists’ satisfaction and revisit intention to rural tourism destination in sarawak: the moderating role of local communities’ attitude. Global Business and Management Research., 10 (2), 115–127.

Chiu, W., Zeng, S., & Cheng, P. (2016). The influence of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: a case study of Chinese tourists in Korea. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research., 10 (2), 223–234.

Chi-Ming, H., Chang, H., & Sung Hee, P. A. (2017). study of two stakeholders’ attitudes toward sustainable tourism development: A comparison model of Penghu Island in Taiwan. Pacific Journal Business Research , 8 , 2–28.

Ciacci, A., Ivaldi, E., Mangano, S., & Ugolini, G. (2021). Environment, logistics and infrastructure: the three spheres of influence of Italian coastal tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism . https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1876715

Article Google Scholar

ComiSión Mundial Del Medio Ambiente Y Del Desarrollo (CMMAD) (1992): Nuestro futuro común, Madrid, Alianza Editorial.

Cotrell, S., Duim, R., Ankersmid, P., & Kelder, L. (2004). Measuring the sustainability of tourism in manuel antonio and texel: a tourist perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism., 12 (5), 409–431.

Crosby, A. (1996). Elementos básicos para un Turismo Sostenible en las áreas naturales . Centro Europeo de Formación Ambiental y Turística.

Crouch, G. I., & Ritchie, J. R. B. (1999). Tourism competitiveness, and societal prosperity. Journal of Business Research., 44 , 137–152.

Davis, D., Allen, J., & Cosenza, R. M. (1988). Segmenting local residents by their attitudes, interests, and opinions toward tourism. Journal of Travel Research., 27 , 2–8.

Díaz, R., & Gutiérrez, D. (2010). La actitud del residente en el destino turístico de Tenerife: Evaluación y tendencia. PASOS, Revista De Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 8 (4), 431–444.

Dimitriades, Z. S. (2006). Customer satisfaction loyalty and commitment in service organizations. Management Research News., 29 (12), 782–800.

Ekanayake, E., & Long, A. E. (2012). Tourism development and economic growth in developing countries. The International Journal of Business and Finance Research., 6 (1), 61–63.

Esman, M. (1984). Tourism as ethnic preservation: The Cajuns of Louisiana. Annals of Tourism Research., 11 , 451–467.

Fernández Poncela, A. M. (2018). Turismo, negocio o desarrollo: El caso de Huasca. México. PASOS, 16 (1), 233–251.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research , 18 (1), 39–50.

Gee, C. Y., Mackens, J. C., & Choy, D. J. (1989). The Travel Industry . Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, M. (2020). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism . https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

Gunn, C. A. (1988). Tourism Planning . Taylor and Francis.

Gursoy, D., & Jurowski, C., (2000). Resident attitudes in relation to distance from tourist attractions. Travel and Tourism Research Association, http://www.ttra.com

Gursoy, D., Jurowski, C., & Uysal, M. (2002). Resident attitudes: A structural modeling approach. Annals of Tourism Research., 29 (1), 79–105.

Gursoy, D., Ouyang, Z., Nunkoo, R., & Wei, W. (2018). Residents’ impact perceptions of and attitudes towards tourism development: a metaanalysis. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management , 28 , 1–28.

Hair, J. F., Hollingsworth, C. L., Randolph, A. B., & Chong, A. Y. L. (2017). An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Industrial Management & Data Systems , 117 (3), 442–458.

Hallowell, R. (1996). The relationship of customer satisfaction, customer loyalty, profitability: An empirical study. International Journal of Service Industry Management., 7 (4), 27–42.

Hancock, A. (2020). Grounded flights force Tui to cut staff hours and wages. Financial Times. Online. https://www.ft.com/content/85a8d648-6a07-11ea-800d-da70cff6e4d3 .

Harrison, D. (1992). Tourism to less developed countries: The social consequences in tourism and less developed countries . Bellhaven.

Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2020). Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after COVID-19. Tourism Geographies . https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1757748

Higgins-Desbiolles, F., Carnicelli, S., Krolikowski, C., Wijesinghe, G., & Boluk, K. (2019). Degrowing tourism: Rethinking tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism., 27 (12), 1926–1944. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1601732

Hsu, C., & Huang, S. (2009). Effects of travel motivation, past experience, perceived constraint, and attitude on revisit intention. Journal of Travel Research , 48 , 29–44.

Huang, Y., & Liu, C. S. (2017). Moderating and mediating roles of environmental concern and ecotourism experience for revisit intention. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management., 29 (7), 1854–1872.

Hunter, L. M. (2000). A comparison of the environmental attitudes, concern, and behaviors of native-born and foreign-born US residents. Population and Environment., 21 (6), 565–580.

Hussain, K., Ali, F., Ari Ragavan, N., & Singh Manhas, P. (2015). Sustainable Tourism and resident satisfaction at Jammu and Kashmir India. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes., 7 (5), 486–499.

INE (2019): https://www.ine.es/

Jensen, J. M. (2015). The relationships between socio-demographic variables, travel motivations and subsequent choice of vacation. Advances in Economics and Business., 3 (8), 322–328.

Jurdana, D.S., & Frleta, D.S. (2012). Sustainable rural tourism development – tourists´satisfaction with Istria as a rural holiday destination. Faculty of Tourism and Hospitality Management in Opatija.Biennial International Congress. Tourism and Hospitality Industry, pp. 51–59.

Jurowski, C., Uysal, M., & Williamd, R. D. (1997). A theoretical analysis of host community resident reactions to tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 36 (2), 3–11.

Jurowski, C., & Gursoy, D. (2004). Distance effects on residents’ attitudes toward tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 31 (2), 296–312.

Kao, Y. F., Huang, L. S., & Wu, C. H. (2008). Effects of theatrical elements on experiential quality and loyalty intentions for theme parks. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research., 13 (2), 163–174.

Keogh, B. (1990). Resident and recreationists’ perceptions and attitudes with respect to tourism development. Journal of Applied Recreation Research., 15 (2), 71–83.

Kim, K., Oh, I., & Jogaratnam, G. (2007). College student travel: A revised model of push motives. Journal of Vacation Marketing , 13 (1), 73–85.

Lankford, S. V., & Howard, D. R. (1994). Developing a tourism attitude impact scale. Annals of Tourism Research, 21 , 121–139.

Li, M., Cai, L. A., Lehto, X. Y., & Huang, J. (2010). A missing link in understanding revisit intention-the role of motivation and image. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing., 27 (4), 335–348.

Liu, J. C., Sheldon, P. J., & Var, T. (1987). Residents perceptions of the environmental impacts of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 14 , 17–37.

Luo, Y., & Deng, J. (2008). The new environmental paradigm and nature-based tourism motivation. Journal of Travel Research., 46 (4), 392–402.

MacKenzie, D., & Royle, A. (2005). Designing occupancy studies: general advice and allocating survey effort. Methodological Insights , 42 (6), 1105–1114.

Mathieson, A., & Wall, G. (1982). Tourism: Economic, Physical, and Social Impacts . Longman House.

Michael, J.M., (2013). Power Hand Tool customers´ Determination of Service Quality and Satisfaction in Repair/return Process. Dissertation at Campella University; Ann Arbor: PreQuest LLC.

Miller, D., Merrilees, B., & Coughlan, A. (2014). Sustainable urban tourism: Understanding and developing pro-environmental behaviours. Journal of Sustainable Tourism., 23 (1), 26–46.

Mohaidin, Z., Tze Wei, K., & Ali Murshi, M. (2017). Factors influencing the tourists´ intention to select Sustainable Tourism destination: A case study of Penang Malaysia. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 3 (4), 442–465.

Murphy, P. E. (1983). Community attitudes to tourism. Tourism Management, 2 , 189–195.

Murphy, P. E. (1985). Tourism: A Community Approach . Routledge.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Nunkoo, R., & So, K.K.F., (2015). Residents’ support for tourism: Testing alternative structural models. Journal of Travel Research .

Ohn, P., & Supinit, V. (2016). Factors influencing tourist loyalty of international graduate students: A study on tourist destination in Pattaya Thailand. International Journal of Thesis Projects and Dissertations, 4 (1), 45–55.

Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research., 17 (4), 460–469.

Oliver, R. L. (1997). Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer . New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc.

OMT. (2005). Indicadores de Desarrollo Sostenible para los destinos turísticos - Guía práctica . Organización Mundial del Turismo.

Othman, N., Anwar, N. A. M., & Kian, L. L. (2010). Sustainability analysis: Visitors impact on taman negara. Journal of Tourism, Hospitality and Culinary Arts, 2 (1), 67–79.

Palacios-Florencio, B., García del Junco, J., Castellanos-Verdugo, M., & Rosa-Díaz, I. M. (2018). Trust as mediator of corporate social responsibility, image and loyalty in the hotel sector. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26 (7), 1273–1289. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1447944

Pavlić, I., Portolan, A., & Puh, B. (2017). Supported current tourism development in UNESCO protected site: The case of old city of dubrovnik. Economies , 5 , 9.

Pesonen, J., Raija, K., Kronenberg, C., & Peters, M. (2011). Understanding the relationship between push and pull motivations in rural torurism. Tourism Review, 66 (3), 32–49.

Pizam, A. (1978). Tourism’s impacts: The social costs to the destination community as perceived by its residents. Journal of Travel Research, 16 (4), 8–12.

Pizam, A. (1994). Monitoring customer satisfaction. Food and Beverage Management: A selection of Readings, Bertrand, D. and Andrew L. (Eds). Butterworth-Heineman. Oxford, 231–247.

Podsakoff, P., MacKenzie, S., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology , 88 , 879–903.

Prebensen, N. K. (2006). Segmenting the group tourist heading for warmer weather—a Norwegian example. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 19 (4), 27–40.

Pretizzo Páez, M. A. (2020). El impacto de la COVID-19 en el sector turismo, academia.edu, 1–10-

Real, J. C., Leal, A., & Roldán, J. L. (2006). Information technology as a determinant of organizational learning and technological distinctive competencias. Industrial Marketing Management , 35 (4), 505–521.

Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J.-M. (2015). SmartPLS 3 . Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH.

Ritchie, J. R. B. (1988). Consensus policy formulation in tourism. Tourism Management, 9 , 199–216.

Roldán, J. L., & Cepeda, G. (2018). Curso sobre PLS-SEM, 6ª edición . Universidad de Sevilla.

Roldán, J. L., & Sanchez-Franco, M. J., (2012). Variance-based structural equation modeling. In M. Mora, et al. (Eds.), Research methodologies, innovations and philosophies in software systems engineering and information systems (pp. 193–221). USA: IGI Global.

Rothman, R. A. (1978). Residents and transients: community reaction to seasonal visitors. Journal of Travel Research, 16 (3), 8–13.

Ruhanen, L., Weiler, B., Moyle, B., & Moyle, C. (2015). Trends and patterns in sustainable tourism research: A 25-year bibliometric analysis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism , 23 , 517–535.

Santana-Jiménez, Y., & Hernández, J. M. (2011). Estimating the effect of overcrowding on tourist attraction: The case of Canary Islands. Tourism Management, 32 (2), 415–425.

Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., Thiele, K. O., & Gudergan, S. P. (2016). Estimation issues with PLS and CBSEM: Where the bias lies. Journal of Business Research , 69 (10), 3998–4010.

Sethna, R., & Richmond, B. (1978). US Virgin islanders’ perceptions of tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 17 (1), 30–37.

Sharpley, R. (2020). Tourism, sustainable development and the theoretical divide: 20 years on. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28 (11), 1932–1946.

Sheldon, P. J., & Var, T. (1984). Resident attitudes to tourism in north wales. Tourism Management, 5 , 40–47.

Stylidis, D., Biran, A., Sit, J., & Szivas, E. (2014). Residents' support for tourism development: The role of residents' place image and perceived tourism impacts. Tourism Management , 45 , 260–274.

Su, W.-S., & Chang, L.-F. (2017). Developing sustainable tourism attitude in Taiwanese residents. The International Journal of Organizational Innovation, 10 (1), 275–289.

Sung, Y.-H., Su, C.-S., & Chang, W.-C. (2016). The quality and value of Hualien´s harvest festival. Annals of Tourism Research, 56 , 128–163.

Tosun, C. (2002). Host perceptions of impacts: A comparative tourism study. Annals of Tourism Research, 29 , 231–245.

Tyrell, T. J., & Spaulding, I. A. (1984). A survey of attitudes toward tourism growth in Rhode Island. Hospitality Education and Research Journal, 8 (2), 22–33.

Var, T., Kendall, K. W., & Tarakcoglu, E. (1985). Residents attitudes toward tourists in a Turkish Resort Town. Annals of Tourism Research, 12 , 652–658.

Vargas, A. et. al., (2007). Desarrollo del turismo y percepción de la comunidad local: factores determinantes de su actitud hacia un mayor desarrollo turístico. XXI Congreso Anual AEDEM, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Madrid, 6,7, y 8 de junio de 2007/Vol.1, pág. 24, coord. por Carmelo Mercado Idoeta.

Venkatesh, U. (2006). Leisure meaning and impact on leisure travel behaviour. Journal of Service Research, 6 (1), 87–108.

Walls, A., Okumus, F., Wang, Y., & Kwun, D. J. (2011). Understanding the consumer experience: An exploratory study of luxury hotels. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 20 (2), 166–197.

Weaver, D. B. (2012). Organic, incremental and induced paths to sustainable mass tourism convergence. Tourism Management., 33 (5), 1030–1037.

Werts, C., Linn, R., & Joreskog, K. (1974). Intraclass reliability estimates: Testing structural assumptions. Educational and Psychological Measurement , 34 , 25–33.

Wong, B. K., Ghazali, M., & Azni, Z. T. (2017). Malaysia my second home: The influence of push and pull motivations on satisfaction. Tourism Management, 61 , 394–410.

World Travel and Tourism Council, (2019). https://wttc.org/en-gb/

World Health Organization (2020): https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public

Wu, H.-C., & Li, T. (2015). An empirical study of the effects of service quality, visitor satisfaction, and emotions on behavioral intentions of visitors to the museums of macau. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism , 16 (1), 80–102.

Wu, H.-C., Ai, C.-H., & Cheng, C.-C. (2016). Synthesizing the effects of green experiential quality, green equity, green image and green experiential satisfaction on green switching intention. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28 (9), 2080–2107.

Xu, J., & Shukman, C. (2016). A new nature-based tourism motivation model: Testing the moderating effects of the push motivation. Tourism Management Perspectives, 18 , 107–110.

Yoon, Y., & Uysal, M. (2005). An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A strucutural model. Tourism Management, 26 (1), 45–56.

Zhang, H., & Lei, S. L. (2012). A structural model of residents’ intention to participate in ecotourism: The case of a wetland community. Tourism Management, 33 (4), 916–925.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Business Organization and Marketing, Faculty of Business Studies, University of Pablo de Olavide, Carretera Utrera, Km.1, 41013, Seville, Spain

Beatriz Palacios-Florencio & Juan Manuel Berbel-Pineda

Department of Business Organization, Faculty of Law and Business, University of Córdoba, Puerta Nueva s.n., 14071, Córdoba, Spain

Luna Santos-Roldán & Ana María Castillo-Canalejo

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Beatriz Palacios-Florencio .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 18 KB)

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Palacios-Florencio, B., Santos-Roldán, L., Berbel-Pineda, J.M. et al. Sustainable Tourism as a Driving force of the Tourism Industry in a Post-Covid-19 Scenario. Soc Indic Res 158 , 991–1011 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02735-2

Download citation

Accepted : 04 June 2021

Published : 12 June 2021

Issue Date : December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02735-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Sustainable tourism

- Mass tourism

- Overcrowded destinations

- Tourism crisis

- Sustainable Tourism development

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

UN Tourism | Bringing the world closer

Share this content.

- Share this article on facebook

- Share this article on twitter

- Share this article on linkedin

Tourism in the 2030 Agenda

The year 2015 has been a milestone for global development as governments have adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, along with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The bold agenda sets out a global framework to end extreme poverty, fight inequality and injustice, and fix climate change until 2030. Building on the historic Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the ambitious set of 17 Sustainable Development Goals and 169 associated targets is people-centred, transformative, universal and integrated.

Harnessing tourism's benefits will be critical to achieving the sustainable development goals and implementing the post-2015 development agenda

Tourism has the potential to contribute, directly or indirectly, to all of the goals. In particular, it has been included as targets in Goals 8, 12 and 14 on inclusive and sustainable economic growth, sustainable consumption and production (SCP) and the sustainable use of oceans and marine resources, respectively.

Sustainable tourism is firmly positioned in the 2030 Agenda. Achieving this agenda, however, requires a clear implementation framework, adequate financing and investment in technology, infrastructure and human resources.

GOAL 1: NO POVERTY

GOAL 2: ZERO HUNGER

GOAL 3: GOOD HEALTH AND WELL-BEING

GOAL 4: QUALITY EDUCATION

GOAL 5: GENDER EQUALITY

GOAL 6: CLEAN WATER AND SANITATION

GOAL 7: AFFORDABLE AND CLEAN ENERGY

GOAL 8: DECENT WORK AND ECONOMIC GROWTH

GOAL 9: INDUSTRY, INNOVATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE

GOAL 10: REDUCED INEQUALITIES

GOAL 11: SUSTAINABLE CITIES AND COMMUNITIES

GOAL 12: RESPONSIBLE CONSUMPTION AND PRODUCTION

GOAL 13: CLIMATE ACTION

GOAL 14: LIFE BELOW WATER

GOAL 15: LIFE ON LAND

GOAL 16: PEACE AND JUSTICE

GOAL 17: PARTNERSHIPS FOR THE GOALS

The future of tourism: Bridging the labor gap, enhancing customer experience

As travel resumes and builds momentum, it’s becoming clear that tourism is resilient—there is an enduring desire to travel. Against all odds, international tourism rebounded in 2022: visitor numbers to Europe and the Middle East climbed to around 80 percent of 2019 levels, and the Americas recovered about 65 percent of prepandemic visitors 1 “Tourism set to return to pre-pandemic levels in some regions in 2023,” United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), January 17, 2023. —a number made more significant because it was reached without travelers from China, which had the world’s largest outbound travel market before the pandemic. 2 “ Outlook for China tourism 2023: Light at the end of the tunnel ,” McKinsey, May 9, 2023.

Recovery and growth are likely to continue. According to estimates from the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) for 2023, international tourist arrivals could reach 80 to 95 percent of prepandemic levels depending on the extent of the economic slowdown, travel recovery in Asia–Pacific, and geopolitical tensions, among other factors. 3 “Tourism set to return to pre-pandemic levels in some regions in 2023,” United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), January 17, 2023. Similarly, the World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC) forecasts that by the end of 2023, nearly half of the 185 countries in which the organization conducts research will have either recovered to prepandemic levels or be within 95 percent of full recovery. 4 “Global travel and tourism catapults into 2023 says WTTC,” World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC), April 26, 2023.

Longer-term forecasts also point to optimism for the decade ahead. Travel and tourism GDP is predicted to grow, on average, at 5.8 percent a year between 2022 and 2032, outpacing the growth of the overall economy at an expected 2.7 percent a year. 5 Travel & Tourism economic impact 2022 , WTTC, August 2022.

So, is it all systems go for travel and tourism? Not really. The industry continues to face a prolonged and widespread labor shortage. After losing 62 million travel and tourism jobs in 2020, labor supply and demand remain out of balance. 6 “WTTC research reveals Travel & Tourism’s slow recovery is hitting jobs and growth worldwide,” World Travel & Tourism Council, October 6, 2021. Today, in the European Union, 11 percent of tourism jobs are likely to go unfilled; in the United States, that figure is 7 percent. 7 Travel & Tourism economic impact 2022 : Staff shortages, WTTC, August 2022.

There has been an exodus of tourism staff, particularly from customer-facing roles, to other sectors, and there is no sign that the industry will be able to bring all these people back. 8 Travel & Tourism economic impact 2022 : Staff shortages, WTTC, August 2022. Hotels, restaurants, cruises, airports, and airlines face staff shortages that can translate into operational, reputational, and financial difficulties. If unaddressed, these shortages may constrain the industry’s growth trajectory.

The current labor shortage may have its roots in factors related to the nature of work in the industry. Chronic workplace challenges, coupled with the effects of COVID-19, have culminated in an industry struggling to rebuild its workforce. Generally, tourism-related jobs are largely informal, partly due to high seasonality and weak regulation. And conditions such as excessively long working hours, low wages, a high turnover rate, and a lack of social protection tend to be most pronounced in an informal economy. Additionally, shift work, night work, and temporary or part-time employment are common in tourism.

The industry may need to revisit some fundamentals to build a far more sustainable future: either make the industry more attractive to talent (and put conditions in place to retain staff for longer periods) or improve products, services, and processes so that they complement existing staffing needs or solve existing pain points.

One solution could be to build a workforce with the mix of digital and interpersonal skills needed to keep up with travelers’ fast-changing requirements. The industry could make the most of available technology to provide customers with a digitally enhanced experience, resolve staff shortages, and improve working conditions.

Would you like to learn more about our Travel, Logistics & Infrastructure Practice ?

Complementing concierges with chatbots.

The pace of technological change has redefined customer expectations. Technology-driven services are often at customers’ fingertips, with no queues or waiting times. By contrast, the airport and airline disruption widely reported in the press over the summer of 2022 points to customers not receiving this same level of digital innovation when traveling.

Imagine the following travel experience: it’s 2035 and you start your long-awaited honeymoon to a tropical island. A virtual tour operator and a destination travel specialist booked your trip for you; you connected via videoconference to make your plans. Your itinerary was chosen with the support of generative AI , which analyzed your preferences, recommended personalized travel packages, and made real-time adjustments based on your feedback.

Before leaving home, you check in online and QR code your luggage. You travel to the airport by self-driving cab. After dropping off your luggage at the self-service counter, you pass through security and the biometric check. You access the premier lounge with the QR code on the airline’s loyalty card and help yourself to a glass of wine and a sandwich. After your flight, a prebooked, self-driving cab takes you to the resort. No need to check in—that was completed online ahead of time (including picking your room and making sure that the hotel’s virtual concierge arranged for red roses and a bottle of champagne to be delivered).

While your luggage is brought to the room by a baggage robot, your personal digital concierge presents the honeymoon itinerary with all the requested bookings. For the romantic dinner on the first night, you order your food via the restaurant app on the table and settle the bill likewise. So far, you’ve had very little human interaction. But at dinner, the sommelier chats with you in person about the wine. The next day, your sightseeing is made easier by the hotel app and digital guide—and you don’t get lost! With the aid of holographic technology, the virtual tour guide brings historical figures to life and takes your sightseeing experience to a whole new level. Then, as arranged, a local citizen meets you and takes you to their home to enjoy a local family dinner. The trip is seamless, there are no holdups or snags.

This scenario features less human interaction than a traditional trip—but it flows smoothly due to the underlying technology. The human interactions that do take place are authentic, meaningful, and add a special touch to the experience. This may be a far-fetched example, but the essence of the scenario is clear: use technology to ease typical travel pain points such as queues, misunderstandings, or misinformation, and elevate the quality of human interaction.

Travel with less human interaction may be considered a disruptive idea, as many travelers rely on and enjoy the human connection, the “service with a smile.” This will always be the case, but perhaps the time is right to think about bringing a digital experience into the mix. The industry may not need to depend exclusively on human beings to serve its customers. Perhaps the future of travel is physical, but digitally enhanced (and with a smile!).

Digital solutions are on the rise and can help bridge the labor gap

Digital innovation is improving customer experience across multiple industries. Car-sharing apps have overcome service-counter waiting times and endless paperwork that travelers traditionally had to cope with when renting a car. The same applies to time-consuming hotel check-in, check-out, and payment processes that can annoy weary customers. These pain points can be removed. For instance, in China, the Huazhu Hotels Group installed self-check-in kiosks that enable guests to check in or out in under 30 seconds. 9 “Huazhu Group targets lifestyle market opportunities,” ChinaTravelNews, May 27, 2021.

Technology meets hospitality

In 2019, Alibaba opened its FlyZoo Hotel in Huangzhou, described as a “290-room ultra-modern boutique, where technology meets hospitality.” 1 “Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba has a hotel run almost entirely by robots that can serve food and fetch toiletries—take a look inside,” Business Insider, October 21, 2019; “FlyZoo Hotel: The hotel of the future or just more technology hype?,” Hotel Technology News, March 2019. The hotel was the first of its kind that instead of relying on traditional check-in and key card processes, allowed guests to manage reservations and make payments entirely from a mobile app, to check-in using self-service kiosks, and enter their rooms using facial-recognition technology.

The hotel is run almost entirely by robots that serve food and fetch toiletries and other sundries as needed. Each guest room has a voice-activated smart assistant to help guests with a variety of tasks, from adjusting the temperature, lights, curtains, and the TV to playing music and answering simple questions about the hotel and surroundings.

The hotel was developed by the company’s online travel platform, Fliggy, in tandem with Alibaba’s AI Labs and Alibaba Cloud technology with the goal of “leveraging cutting-edge tech to help transform the hospitality industry, one that keeps the sector current with the digital era we’re living in,” according to the company.

Adoption of some digitally enhanced services was accelerated during the pandemic in the quest for safer, contactless solutions. During the Winter Olympics in Beijing, a restaurant designed to keep physical contact to a minimum used a track system on the ceiling to deliver meals directly from the kitchen to the table. 10 “This Beijing Winter Games restaurant uses ceiling-based tracks,” Trendhunter, January 26, 2022. Customers around the world have become familiar with restaurants using apps to display menus, take orders, and accept payment, as well as hotels using robots to deliver luggage and room service (see sidebar “Technology meets hospitality”). Similarly, theme parks, cinemas, stadiums, and concert halls are deploying digital solutions such as facial recognition to optimize entrance control. Shanghai Disneyland, for example, offers annual pass holders the option to choose facial recognition to facilitate park entry. 11 “Facial recognition park entry,” Shanghai Disney Resort website.

Automation and digitization can also free up staff from attending to repetitive functions that could be handled more efficiently via an app and instead reserve the human touch for roles where staff can add the most value. For instance, technology can help customer-facing staff to provide a more personalized service. By accessing data analytics, frontline staff can have guests’ details and preferences at their fingertips. A trainee can become an experienced concierge in a short time, with the help of technology.

Apps and in-room tech: Unused market potential

According to Skift Research calculations, total revenue generated by guest apps and in-room technology in 2019 was approximately $293 million, including proprietary apps by hotel brands as well as third-party vendors. 1 “Hotel tech benchmark: Guest-facing technology 2022,” Skift Research, November 2022. The relatively low market penetration rate of this kind of tech points to around $2.4 billion in untapped revenue potential (exhibit).

Even though guest-facing technology is available—the kind that can facilitate contactless interactions and offer travelers convenience and personalized service—the industry is only beginning to explore its potential. A report by Skift Research shows that the hotel industry, in particular, has not tapped into tech’s potential. Only 11 percent of hotels and 25 percent of hotel rooms worldwide are supported by a hotel app or use in-room technology, and only 3 percent of hotels offer keyless entry. 12 “Hotel tech benchmark: Guest-facing technology 2022,” Skift Research, November 2022. Of the five types of technology examined (guest apps and in-room tech; virtual concierge; guest messaging and chatbots; digital check-in and kiosks; and keyless entry), all have relatively low market-penetration rates (see sidebar “Apps and in-room tech: Unused market potential”).

While apps, digitization, and new technology may be the answer to offering better customer experience, there is also the possibility that tourism may face competition from technological advances, particularly virtual experiences. Museums, attractions, and historical sites can be made interactive and, in some cases, more lifelike, through AR/VR technology that can enhance the physical travel experience by reconstructing historical places or events.

Up until now, tourism, arguably, was one of a few sectors that could not easily be replaced by tech. It was not possible to replicate the physical experience of traveling to another place. With the emerging metaverse , this might change. Travelers could potentially enjoy an event or experience from their sofa without any logistical snags, and without the commitment to traveling to another country for any length of time. For example, Google offers virtual tours of the Pyramids of Meroë in Sudan via an immersive online experience available in a range of languages. 13 Mariam Khaled Dabboussi, “Step into the Meroë pyramids with Google,” Google, May 17, 2022. And a crypto banking group, The BCB Group, has created a metaverse city that includes representations of some of the most visited destinations in the world, such as the Great Wall of China and the Statue of Liberty. According to BCB, the total cost of flights, transfers, and entry for all these landmarks would come to $7,600—while a virtual trip would cost just over $2. 14 “What impact can the Metaverse have on the travel industry?,” Middle East Economy, July 29, 2022.

The metaverse holds potential for business travel, too—the meeting, incentives, conferences, and exhibitions (MICE) sector in particular. Participants could take part in activities in the same immersive space while connecting from anywhere, dramatically reducing travel, venue, catering, and other costs. 15 “ Tourism in the metaverse: Can travel go virtual? ,” McKinsey, May 4, 2023.

The allure and convenience of such digital experiences make offering seamless, customer-centric travel and tourism in the real world all the more pressing.

Three innovations to solve hotel staffing shortages

Is the future contactless.

Given the advances in technology, and the many digital innovations and applications that already exist, there is potential for businesses across the travel and tourism spectrum to cope with labor shortages while improving customer experience. Process automation and digitization can also add to process efficiency. Taken together, a combination of outsourcing, remote work, and digital solutions can help to retain existing staff and reduce dependency on roles that employers are struggling to fill (exhibit).

Depending on the customer service approach and direct contact need, we estimate that the travel and tourism industry would be able to cope with a structural labor shortage of around 10 to 15 percent in the long run by operating more flexibly and increasing digital and automated efficiency—while offering the remaining staff an improved total work package.

Outsourcing and remote work could also help resolve the labor shortage

While COVID-19 pushed organizations in a wide variety of sectors to embrace remote work, there are many hospitality roles that rely on direct physical services that cannot be performed remotely, such as laundry, cleaning, maintenance, and facility management. If faced with staff shortages, these roles could be outsourced to third-party professional service providers, and existing staff could be reskilled to take up new positions.

In McKinsey’s experience, the total service cost of this type of work in a typical hotel can make up 10 percent of total operating costs. Most often, these roles are not guest facing. A professional and digital-based solution might become an integrated part of a third-party service for hotels looking to outsource this type of work.

One of the lessons learned in the aftermath of COVID-19 is that many tourism employees moved to similar positions in other sectors because they were disillusioned by working conditions in the industry . Specialist multisector companies have been able to shuffle their staff away from tourism to other sectors that offer steady employment or more regular working hours compared with the long hours and seasonal nature of work in tourism.