FOLASHADE S. OMOLE, MD, CHARLES M. SOW, MD, MSCR, EDITH FRESH, PhD, DOLAPO BABALOLA, MD, AND HARRY STROTHERS, III, MD, MMM

Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(7):780-784

Patient information: See related handout for family members at office visits , written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations to disclose.

The physician-patient relationship is part of the patient's larger social system and is influenced by the patient's family. A patient's family member can be a valuable source of health information and can collaborate in making an accurate diagnosis and planning a treatment strategy during the office visit. However, it is important for the physician to keep an appropriate balance when addressing concerns to maintain the alliance formed among physician, patient, and family member. The patient-centered medical home, a patient care concept that helps address this dynamic, often involves a robust partnership among the physician, the patient, and the patient's family. During the office visit, this partnership may be influenced by the ethnicity, cultural values, beliefs about illness, and religion of the patient and his or her family. Physicians should recognize abnormal family dynamics during the office visit and attempt to stay neutral by avoiding triangulation. The only time neutrality should be disrupted is if the physician suspects abuse or neglect. It is important that the patient has time to communicate privately with the physician at some point during the visit.

The physician-patient relationship is part of the patient's larger social system and is influenced by members of the patient's family. 1 There are several relationship dynamics involved in this context, such as those between the physician and the patient, the patient and his or her family, the physician and the patient's family, and the patient and society. 2 Patients often believe that the presence of a family member leads to an atmosphere of greater empathy and compassion from the professional health care team. 3 , 4 The purpose of this article is to identify and understand each person's role during an office visit when the patient is accompanied by a family member.

Definition of Family

Considering the growing cultural diversity with traditional and nontraditional families, the term “family” could be defined as any group of persons who are related biologically, emotionally, or legally. 1 , 5 Examples of nontraditional families are blended families, unmarried couples, and gay and lesbian couples or families. 1 , 6 , 7 Family members who may accompany a patient to an office visit include children, siblings, parents, spouses or significant others, hired caregivers, interpreters, neighbors, friends, and clergy or church members.

Managing the Office Visit

Family members are present about one-third of the time in the examination room, 8 and their presence usually prolongs the visit by only a few minutes. 9 Those more likely to have a family member present include patients with a low level of health literacy, patients with a chronic disease, older patients, women, gay or lesbian patients, non–English-speaking patients, and children. 6 , 7

The background of the patient's family (e.g., ethnicity, cultural values, religion, attitudes and beliefs about illness) is ever-present during the office visit, and this plays a role in the patient's decision making. 1 The patient and his or her family member mutually influence each other and the patient-physician relationship, creating a therapeutic triangle. 10

THE FAMILY MEMBER'S ROLE

There are a variety of reasons why a family member may accompany a patient to an office visit. It is common for a family member to be there to offer support during visits that may involve receiving bad news about the patient's health. Other common reasons include if the patient needs help communicating with the physician (e.g., language barrier, hearing or vision impairment) or if the patient has a physical or mental impairment or disability. For some patients, it may be a part of their family's habits or culture, or the age of the patient may be a factor, such as with older patients or children. Family members are the most central and enduring influence in the lives of children, whose health and well-being are linked to their parents' physical, emotional, and social health; social circumstances; and child-rearing practices. 11

Whatever the reasons for their presence, family members can be a valuable part of the health care team ( Table 1 12 – 14 ) . Family members help patients manage and cope with illness. 15 They also can be valuable sources of health information and can act as collaborators in making an accurate diagnosis and planning a treatment strategy. 4 , 12 , 13 , 16 , 17 However, there must be a balance in the concerns addressed during the visit to maintain the alliance formed among patient, physician, and family member. 16 , 18

THE PHYSICIAN'S ROLE

The presence of a family member during a patient encounter introduces unique considerations that require an expanded interviewing skill set from the physician 5 ( Table 2 19 , 20 ) . It is important to recognize and encourage the family member as a source of valuable information and support. 12 , 13 , 21 The degree to which the family member feels supported by the physician may influence the family member's burden, attitude, and emotional health status. 15

The office visit should involve asking the patient and his or her family member about the nature of their relationship, the family member's role in the care of the patient, and the reason for the presence of the family member. 5 , 21 It is important for physicians to maintain their relationship with the patient and be observant of the patient's role in the family member's presence. Physicians should always remember to whom they are primarily responsible. Any additional concerns of the family member should be addressed only after taking care of the patient's issues and concerns.

The Patient-Centered Medical Home . There is compelling evidence that patient-centered communication improves clinical outcomes. 17 , 22 The role of a family physician is enhanced within the concept of the patient-centered medical home, an approach to health care that recognizes the role of patients and their families in providing medical care ( Table 3 6 , 15 ) . This approach encourages collaboration among the patient, family, and health care clinicians, respecting individual and family strengths, cultures, traditions, and expertise. The patient-centered medical home performs these functions well by emphasizing the following principles: care is being provided for a person, not a condition; the patient is best understood in the context of his or her family, culture, values, and goals; and honoring that context will result in better health care, safety, and patient satisfaction. 23 Additional information and resources about the patient-centered medical home are available online from the American Academy of Family Physicians at https://www.aafp.org/online/en/home/membership/initiatives/pcmh/aafpleads/aafppcmh.html .

Although the patient-centered medical home approach recognizes the role of the family in providing medical care, the family member's presence also may add challenges to the visit.

PATIENT SAFETY

Patients may be vulnerable to abuses of power within their families. 24 Although the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against routine family and intimate partner violence screening, 25 patients should be given a chance to express their concerns in private if there is any suspicion of neglect or physical, emotional, and/or financial abuse ( Table 4 26 , 27 ) . A private discussion time between the patient and physician should be set aside in most encounters, especially initially, so the physician can address concerns about whether a family member is acting in the patient's best interest and whether the patient feels safe and well cared for. The physical examination may present an opportunity to request time alone with the patient. 5 , 21 The physician can use this time to elicit fears or concerns; obtain the names of other family caregivers the patient might want the physician to contact; and determine whether the patient requires legal or social services. 15 Physicians need to be familiar with specific state reporting statutes and the implications of reporting patient neglect, abuse, or exploitation. 15

PATIENT CONFIDENTIALITY

The physician must exercise care to avoid a potential breach of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), which states that health professionals may share relevant health care information with the family member only if the patient agrees to, or does not object to, the disclosure. 5 , 15 A cross-sectional survey of family physician respondents found that 95 percent provided private health information to a patient's family member, but only 56 percent asked their patients for permission to share this private health information. 28 However, HIPAA should not be viewed as a barrier to communication. 15 Maintaining and respecting confidentiality is of utmost importance, and priority should always be given to the patient's right to privacy and confidentiality. 5 This is why it is imperative that the patient has time to communicate privately with the physician at some point during the visit.

FAMILY DYNAMICS AND TRIANGULATION

Physicians should recognize abnormal family dynamics during the office visit and attempt to stay neutral by avoiding triangulation (i.e., when two persons are in conflict, each will try to align with a third). 5 , 12 , 21 , 29 To achieve maximum neutrality, physicians should not take the side of the family member or the patient. The only time neutrality should be violated is if physicians suspect abuse or neglect. 29 Any other family conflict that remains unresolved may be referred to a family therapist, particularly if there is a chance that these issues might interfere with the patient's health care planning. 5

Illustrative Case

A 56-year-old man is evaluated and diagnosed with depression during an office visit that includes his wife. His physician recommends beginning treatment with an anti-depressant. The patient is undecided about taking the medication, but his wife insists that he begin treatment with the medication. She also requests refills for her own medications.

Interpretation : The presence of the patient's wife brings potential benefits, including the provision of a more complete history of diagnosis, such as duration of symptoms and impact on well-being. Although the wife's values could be imparted into the decision making, her presence also constitutes a liability. The physician can best navigate the demands of this encounter by maintaining a primary focus on the patient's needs. If the patient's wife interferes with this focus, the physician should know when to excuse her and talk to the patient in private. From a legal perspective, the physician should avoid making the wife the sole decision maker if the patient is competent. Regarding the wife's request for refills, the physician should limit curbside consultations and encourage her to make a separate appointment for herself.

Hahn SR, Feldman MD. Families. In: Feldman MD, Christensen JF, eds. Behavioral Medicine: A Guide for Clinical Practice . 3rd ed. New York, NY: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill Medical Pub. Division; 2008:55–70.

Dokken D, Ahmann E. The many roles of family members in “family-centered care”—part I. Pediatr Nurs. 2006;32(6):562-565.

Axelsson ÅB, Zettergren M, Axelsson C. Good and bad experiences of family presence during acute care and resuscitation. What makes the difference?. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005;4(2):161-169.

Labrecque MS, Blanchard CG, Ruckdeschel JC, Blanchard EB. The impact of family presence on the physician-cancer patient interaction. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33(11):1253-1261.

Lang F, Marvel K, Sanders D, et al. Interviewing when family members are present. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65(7):1351-1354.

Scholle SH. Engaging patients and families in the medical home. Rockville, Md.: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010.

Brady DW, Schneider J, White JC. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, & transgender (LGBT) patients. In: Feldman MD, Christensen JF, eds. Behavioral Medicine: A Guide for Clinical Practice . 3rd ed. New York, NY: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill Medical Pub. Division; 2008:121–129.

Medalie JH, Zyzanski SJ, Langa D, Stange KC. The family in family practice: is it a reality?. J Fam Pract. 1998;46(5):390-396.

Cole-Kelly K, Yanoshik MK, Campbell J, Flynn SP. Integrating the family into routine patient care: a qualitative study. J Fam Pract. 1998;47(6):440-445.

Doherty WJ, Baird MA, Becker L. Family medicine and the biopsychosocial model: the road toward integration. In: Doherty WJ, ed. Family Medicine: The Maturing of a Discipline . New York, NY: Haworth Press; 1987:51–70.

Schor EL. American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on the Family. Family pediatrics: report of the Task Force on the Family. Pediatrics. 2003;111(6 pt 2):1541-1571.

Brown JB, Brett P, Stewart M, Marshall JN. Roles and influence of people who accompany patients on visits to the doctor. Can Fam Physician. 1998;44:1644-1650.

Clayman ML, Roter D, Wissow LS, Bandeen-Roche K. Autonomy-related behaviors of patient companions and their effect on decision-making activity in geriatric primary care visits. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(7):1583-1591.

Schilling LM, Scatena L, Steiner JF, et al. The third person in the room: frequency, role, and influence of companions during primary care medical encounters. J Fam Pract. 2002;51(8):685-690.

Mitnick S, Leffler C, Hood VL American College of Physicians Ethics, Professionalism and Human Rights Committee. Family caregivers, patients and physicians: ethical guidance to optimize relationships. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(3):255-260.

Main DS, Holcomb S, Dickinson P, Crabtree BF. The effect of families on the process of outpatient visits in family practice. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(10):888.

Street RL, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(3):295-301.

McBride JL. Managing family dynamics. Fam Pract Manag. 2004;11(7):70.

Campbell TL, McDaniel SH, Cole-Kelly K. Family issues in health care. In: Taylor RB, ed. Family Medicine: Principles and Practice . 6th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2003:24–32.

World Organization of National Colleges, Academies and Academic Associations of General Practitioners/Family Physicians (WONCA). The role of the general practitioner/family physician in health care systems: a statement from WONCA, 1991. http://www.globalfamilydoctor.com/publications/Role_GP.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2011.

Greene MG, Majerovitz SD, Adelman RD, Rizzo C. The effects of the presence of a third person on the physician-older patient medical interview. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42(4):413-419.

Levinson W, Lesser CS, Epstein RM. Developing physician communication skills for patient-centered care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(7):1310-1318.

O'Malley PJ, Brown K, Krug SE Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Patient- and family-centered care of children in the emergency department. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):e511-521.

Candib LM, Gelberg L. How will family physicians care for the patient in the context of family and community?. Fam Med. 2001;33(4):298-310.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for family and intimate partner violence: recommendation statement. March 2004. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/3rduspstf/famviolence/famviolrs.htm . Accessed June 8, 2011.

Kennedy RD. Elder abuse and neglect: the experience, knowledge, and attitudes of primary care physicians. Fam Med. 2005;37(7):481-485.

Robinson L, de Benedictis T, Segal J. Helpguide.org. Elder abuse and neglect. Warning signs, risk factors, prevention, and help. http://www.helpguide.org/mental/elder_abuse_physical_emotional_sexual_neglect.htm . Accessed February 20, 2011.

Pérez-Cárceles MD, Pereñiguez JE, Osuna E, Luna A. Balancing confidentiality and the information provided to families of patients in primary care. J Med Ethics. 2005;31(9):531-535.

Gottlieb MC, Lasser J, Simpson GL. Legal and ethical issues in couple therapy. In: Gurman AS, ed. Clinical Handbook of Couple Therapy . 4th ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008:698–716.

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2011 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

What Is Informed Consent?

- Implied Consent

- When It Is Required

Informed consent is an important communication process that takes place between patients and their healthcare providers. It is a key part of the healthcare decision-making process.

During the informed consent process, your healthcare provider makes sure you understand your diagnosis, treatment options, and the benefits and risks of those treatment options. Depending on your treatment plan, you may be asked to sign an informed consent document that gives your healthcare provider permission to do certain tests or procedures.

This article outlines what you should know about the consent process, including the difference between informed consent and implied consent, and steps you can take to ensure you're taking an active role in your medical care.

The consent process gives patients the ability to decide what happens to their bodies and enables them to be active participants in their medical care. In short, no one should perform medical tests, procedures, or research on you without first making sure you understand the risks and benefits, and then getting your permission to proceed.

Informed consent includes:

- Information about your diagnosis

- The benefits and risks of treatments (or no treatment)

- How and by whom procedures will be carried out

For instance, if you are receiving care at a teaching hospital, you must be told if a medical trainee will be involved in your care or will be performing a specific procedure.

Your healthcare provider will let you know what they are doing and why, whether they're performing a physical exam, prescribing a medication, or developing a more complex treatment plan that requires additional tests or procedures. The other providers on your care team will do the same. If you need additional procedures or tests, you'll provide additional consent as needed.

Your healthcare provider is required to ensure you fully understand the information you've been given. They may provide information during a conversation, or use patient education materials like brochures, fact sheets, or videos. You should have the opportunity to ask questions and have them answered.

Your healthcare provider must be able to prove that you authorized tests, treatments, or interventions, so your agreement or refusal of a treatment plan will be documented in your medical record.

Elements of Informed Consent

Healthcare providers must follow four central elements of the informed consent process.

Decision-Making Ability

You must be able to make the decision. That means you can understand the options available to you and the consequences of the proposed treatments (or of not being treated). Children and patients who are unconscious lack decision-making ability and would not be able to participate in the informed consent process.

Who Can Provide Informed Consent for You?

In the United States, you must be 18 years or older to give informed consent. For minors who are 17 or younger, a parent or legal guardian makes all medical decisions.

A surrogate, or legal representative, can also give informed consent (and sign an informed consent document) if the patient is:

- Unable to understand the medical information provided

- Cannot assess the possible outcomes of treatment

- Unable to make decisions due to incapacitation or mental illness

Information Sharing

Your healthcare provider must disclose information on your diagnosis and their proposed treatments. This includes information on the effectiveness of the treatments, the benefits, and the risks. It should also include the risks and benefits of refusing treatment. Your healthcare provider must provide a full picture of what you can expect.

Understanding

One of the most important elements of informed consent is your understanding of the information. Ask questions to make sure that you fully comprehend what's being presented before you agree to treatments.

Voluntary Agreement

No one should pressure or force you to provide informed consent. Your agreement should never be given under duress.

Informed Consent vs. Consent to Treat

Most medical offices include a Consent to Treat form with its standard patient paperwork. When you sign this form, you're giving the healthcare provider permission to provide care and for the practice to bill your insurance. This form clearly states your right to discuss all procedures or treatments or to refuse them.

Implied Consent vs. Informed Consent

Implied consent takes place in situations where a more formal consent is not needed. For instance, if you make an appointment to have a blood sample drawn and roll up your sleeve, your consent is implied.

When Is Informed Consent Required?

Except under specific circumstances, informed consent—whether written or implied—is required for any treatment or medical procedure and for any research study where there is more than minimal risk to the subjects. In the majority of situations, the informed consent process happens before a test or treatment is performed.

You'll be given the opportunity to provide consent—informed (written or verbal) or implied—for everything you're asked to do. Your provider will note your consent in your record and, in some cases, document it with a signed form.

You Have the Right to Change Your Mind

You can change your mind about your treatment or other health care decisions even after you've signed an informed consent form. You always have the right to stop or switch treatments.

You won't need to provide written consent for some things, like a prescription for medication. The act of having your prescription filled implies your consent to taking the medicine.

Types of Procedures

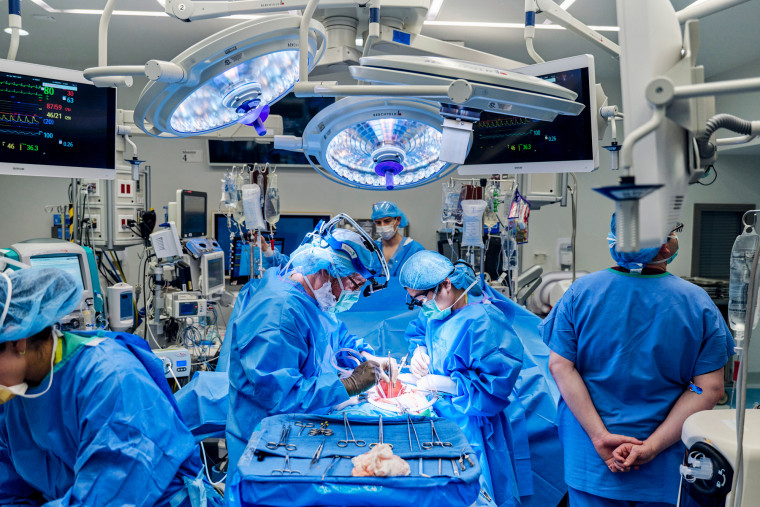

For some procedures, you may be asked to sign an informed consent document. Written informed consent is required for medical procedures such as:

- Surgeries (both inpatient and outpatient)

- Invasive medical procedures, such as colonoscopies or biopsies

- Placement of a medical device, such as an intrauterine device (IUD)

- Chemotherapy

- Radiation therapy

Some laboratory tests, like an HIV blood test, require written consent, but not all do.

Emergency Situations

In an emergency situation, a healthcare provider may not be able to get consent from you or your representative. In these situations, treatment can be started without consent. Your healthcare provider should get official permission from you as soon as possible. Full consent must be given for any further or ongoing treatment.

Tips for Providing Informed Consent

If you are asked to sign an informed consent document, there are some steps you can take to make sure you're fully engaged in the process. Some guidelines are listed below.

Listen and Learn

Understand that signing the form tells your healthcare providers that they have permission to go forward with recommended treatments, tests, or procedures. Before you agree with this, be sure you understand:

- What your other options are: Could something else be done instead?

- What could happen during the process

- What could happen as a result of the treatment

- What could happen without the treatment

Ask For Time to Review

There's no rule that says you must sign the form as soon as it's handed to you. Sometimes, the informed consent form is mixed with other documents that must be signed before you see a healthcare provider.

Confirm with your provider's office what needs to be signed immediately and what you can take home to review before signing.

Confirm Your Understanding

When your healthcare provider describes the tests, procedures, benefits, and risks to you, take the time to repeat them back to be sure you understand them. That will give your healthcare provider a chance to clarify any information you may not fully understand.

Know the Limits

Recognize that your signature on the form provides no guarantees that the treatment will relieve your health problem or cure you. Unfortunately, medical treatment can never provide a guarantee.

However, understanding why you need the test or treatment, how it will happen, and what the risks and alternatives are, could improve the chances it will be successful.

It is also important to remember that you can, at any time, change your mind.

Informed consent is when your healthcare provider makes sure you understand your diagnosis and the risks and benefits of any tests, medical procedures, or other treatments they recommend to treat your condition. Informed consent is at the core of the shared-decision making process between a patient and their healthcare provider.

Informed consent also means that your healthcare provider will help you understand alternative treatments as well as the risks and benefits of refusing treatment. Before you provide consent, be sure all of your questions are answered and that you understand the information. Don't forget that you can change your mind about your treatment plan even after you provide informed consent.

Association of American Medical Colleges. What "informed consent" really means.

Hein IM, De Vries MC, Troost PW, Meynen G, Van Goudoever JB, Lindauer RJL. Informed consent instead of assent is appropriate in children from the age of twelve: Policy implications of new findings on children’s competence to consent to clinical research . BMC Medical Ethics . 2015;16(1):76. doi:10.1186%2Fs12910-015-0067-z

American Medical Association. Informed consent .

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Health Literacy Universal Toolkit. Consent to treat form .

American Cancer Society. What is informed consent?

Kakar H, Gambhir RS, Singh S, Kaur A, Nanda T. Informed consent: Corner stone in ethical medical and dental practice. J Family Med Prim Care . 2014;3(1):68-71. doi:10.4103/2249-4863.130284

By Trisha Torrey Trisha Torrey is a patient empowerment and advocacy consultant. She has written several books about patient advocacy and how to best navigate the healthcare system.

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Mind & Body Articles & More

How doctors can communicate better with patients, two new books suggest that we can improve communication and care in medicine with more mindfulness and presence..

No doubt about it: Doctors are stressed out. Surveys show that physician burnout is on the rise, with the percentage of physicians in the United States reporting symptoms of burnout rising from 45 percent in 2011 to 54 percent in 2014.

If you ask doctors why they’re so stressed, many mention heavy patient loads, endless patient charts to fill out, the looming possibility of litigation, and back-and-forth communication with health insurance companies. These constant distracters can lead to the erosion of patient-clinician interactions, miscommunication, clinical errors, or worse.

Now, two new books— Attending: Medicine, Mindfulness, and Humanity , by Dr. Ronald Epstein, and What Patients Say, What Doctors Hear , by Dr. Danielle Ofri—candidly unpack the factors that contribute to physician-patient communication breakdowns and medical errors. They reveal the challenges that doctors and patients face in communicating and provide optimistic insights on how to improve health care.

Four mindfulness skills for doctors

Epstein, a professor of medicine at Rochester University and a practicing physician, is a leader of the mindfulness movement in medicine. Drawing from his own groundbreaking paper , he explains how mindful self-reflection and self-regulation are key to masterful clinical care, enabling physicians to listen attentively, make good judgments, and act compassionately.

“Medicine and meditation, etymologically, come from the same root: to consider, advise, reflect, to take appropriate measures,” he writes, suggesting that the two are closely related. This explains why doctors should consider using mindfulness in their medical practice.

Using anecdotes, Zen Buddhist stories, and thoroughly cited research, Epstein explores how the four mindfulness skills of attention, curiosity, beginner’s mind, and presence mirror those physicians need to provide quality care:

- Attention. Because of everything they have on their minds, physicians may not be fully attentive in the exam room. Doctors often rely on automatic, fast thinking when interacting with patients. But practicing mindful attention can help them slow down enough to use deliberate, more conscious thinking when patients present signs of something serious.

- Curiosity. Developing a sense of curiosity can inspire physicians to ask more questions and dig deeper with patients, as well as foster empathy and understanding for patients’ unique needs, values, and circumstances. It also helps doctors recognize when something is off with a patient so they can then “tune in.” Epstein notes that while genetics partly contributes to curiosity , supportive environments can also foster it—particularly those that allow physicians to feel comfortable freely sharing their doubts, discoveries, and mishaps.

- Beginner’s mind. Inspired by a book written by Shunryu Suzuki, Epstein advises physicians to “hold expertise lightly” and be aware that their understanding of a patient’s case, while based on expertise, may be provisional and incomplete. He warns that self-confidence can get in the way of good care , if physicians don’t recognize that there are things they may not fully know. Luckily, beginner’s mind can be taught: At least one randomized controlled study found that practicing mindfulness meditation helped people to not be “blinded by experience” from novel or obvious solutions to problems.

- Presence. Listening deeply, without judgment, interruption, or preconceptions, can be tough for physicians who have a myriad of other things to worry about. However, a physician’s presence can help a patient feel understood and acknowledged, and decrease chances of miscommunication and error. To be present, one must “quiet the mind”—a skill that can be honed through reflective, contemplative practices.

Why doctors should train in mindfulness

Epstein makes a case that almost any physician can practice mindfulness to improve patient care, and the science supports that contention.

In a study of primary care physicians, Epstein found that a year-long mindfulness practice program increased their resilience (improved mood, lower burnout), quality of care (safer and more timely, accessible, effective, and patient-centered), and patient interactions (more empathetic, compassionate, and responsive). Patients of clinicians practicing mindfulness are more likely to disclose personal (and potentially critical) information and comply better with treatments. Epstein highlights other important aspects of patient care that can benefit from mindfulness. Making good decisions involves becoming aware of one’s biases and engaging strategies to correct them, and mindfulness has been shown to support that. Also, being more mindful can help physicians be attuned to the suffering of their patients without becoming overwhelmed. While Epstein acknowledges that being with suffering can be draining, studies have found that training in compassion , self-compassion , or loving-kindness meditation can mitigate physicians’ emotional distress and increase their resilience. How can mindfulness in medicine be sustained? It starts in medical school, where compassion and listening skills could be taught and emphasized as much as anatomy or biochemistry.

Support from colleagues and medical institutions is also important, writes Epstein. Doctors are held to high standards, and they are not inclined to share their mistakes with colleagues. However, sharing stories with each other can be very therapeutic , as can being in a place that encourages doctors to admit to difficulties they are experiencing.

Epstein cites the success of a “confessions” project led by colleague Dr. Suzanne Karan, to encourage doctors to share medical errors. Intended to identify causes and prevent future errors, the program also addresses clinicians’ psychological and educational needs. Initiatives like this can help the culture of medicine become more nurturing and supportive of its healers.

How physician-patient communication breaks down

Ofri, a professor of medicine at New York University and hospital internist, shares many of Epstein’s concerns about physician-patient interactions in her book What Patients Say, What Doctors Hear . But while Epstein focuses on the benefits of mindfulness, Ofri hones in on listening and communication skills as powerful tools for exceptional patient care.

There are many barriers to effective communication between physicians and patients, according to Ofri. Doctors may be distracted by millions of other things as they try to listen to patients. Sometimes, patients don’t know their true underlying problem or what to reveal to the doctor. Meaning and intent can get lost. Although the healing professions seek to be nonjudgmental, Ofri points out that doctors’ implicit biases can prevent them from giving equal care to all patients. Studies have shown that doctors show less respect to patients with obesity, for example. African-American patients tend to get less patient-centered care, experience more verbal dominance from doctors, and receive fewer and less-aggressive treatments. (However, the flip side of implicit bias also exists; patients tend to feel more comfortable seeing doctors who are similar in race.)

The medicine of good communication

Ofri suggests that to improve communication, doctors should spend more time listening effectively during the appointment. On average, doctors interrupt patients within 12 seconds of them first speaking during primary care visits and throughout the appointment—often, before they have finished explaining an issue. One study shows that inattentive listening can distract the speaker from telling their own stories effectively, suggesting that speakers and listeners have a shared responsibility.

Doctors can help patients communicate their problems better and feel more understood by acknowledging what they’re saying and encouraging them to continue, and even removing physical barriers between the two of them (i.e., not talking from behind a computer).

Ofri also advises that doctors ask their patients, “Is there anything else?” She acknowledges that this can be daunting for doctors because it opens a Pandora’s box of dialogue that may cut into other patients’ appointment times.

However, understanding the patient as much as possible from the start can save a lot of time in subsequent visits. For example, Ofri once had a patient with a long history of trouble adhering to his numerous medication protocols (despite repeated efforts to explain them to him). It took a year of visits with her for the patient to reveal that he was illiterate and couldn’t read the bottles. She suggests that if she’d taken more care initially, she could have discovered this sooner.

Clear communication from doctors may have a healing effect. Studies on pain perception find that, similar to the placebo effect, thoughtfully walking a patient through a procedure that is being administered, or one that will occur in the future, can make them less anxious and more optimistic, leading to less pain.

Better communication can also lead to less litigation . Whereas patients may feel that doctors are indifferent toward medical errors, in reality those errors haunt doctors for years. Better understanding between parties—and a doctor’s willingness to admit to errors, show concern, and apologize —can help prevent patients from seeking retribution through lawsuits.

Amid the pressure and fast pace of medicine, doctors and other health care providers can still learn to slow down and cultivate better listening and understanding. Doing so gives patients a chance to communicate more effectively, which saves more time and more lives in the long run. Both of these books can help doctors and patients—and, really, anyone in any professional or personal partnership—to work together toward better communication and connection.

About the Author

Deborah Yip

Deborah Yip is a medical student at the University of California, San Francisco, a former GGSC research assistant, and a contributor to Greater Good .

You May Also Enjoy

This article — and everything on this site — is funded by readers like you.

Become a subscribing member today. Help us continue to bring “the science of a meaningful life” to you and to millions around the globe.

Republish This Story

Virtual or In Person: Which Kind of Doctor’s Visit Is Better, and When It Matters

When the covid-19 pandemic swept the country in early 2020 and emptied doctors’ offices nationwide, telemedicine was suddenly thrust into the spotlight. Patients and their physicians turned to virtual visits by video or phone rather than risk meeting face-to-face.

During the early months of the pandemic, telehealth visits for care exploded .

“It was a dramatic shift in one or two weeks that we would expect to happen in a decade,” said Dr. Ateev Mehrotra , a professor at Harvard Medical School whose research focuses on telemedicine and other health care delivery innovations. “It’s great that we served patients, but we did not accumulate the norms and [research] papers that we would normally accumulate so that we can know what works and what doesn’t work.”

Now, three years after the start of the pandemic, we’re still figuring that out. Although telehealth use has moderated, it has found a role in many physician practices, and it is popular with patients.

More than any other field, behavioral health has embraced telehealth. Mental health conditions accounted for just under two-thirds of telehealth claims in November 2022, according to FairHealth , a nonprofit that manages a large database of private and Medicare insurance claims.

Telehealth appeals to a variety of patients because it allows them to simply log on to their computer and avoid the time and expense of driving, parking, and arranging child care that an in-person visit often requires.

But how do you gauge when to opt for a telehealth visit versus seeing your doctor in person? There are no hard-and-fast rules, but here’s some guidance about when it may make more sense to choose one or the other.

Email Sign-Up

Subscribe to KFF Health News' free Weekly Edition.

If It’s Your First Visit

“As a patient, you’re trying to evaluate the physician, to see if you can talk to them and trust them,” said Dr. Russell Kohl , a family physician and board member of the American Academy of Family Physicians. “It’s hard to do that on a telemedicine visit.”

Maybe your insurance has changed and you need a new primary care doctor or OB-GYN. Or perhaps you have a chronic condition and your doctor has suggested adding a specialist to the team. A face-to-face visit can help you feel comfortable and confident with their participation.

Sometimes an in-person first visit can help doctors evaluate their patients in nontangible ways, too. After a cancer diagnosis, for example, an oncologist might want to examine the site of a biopsy. But just as important, he might want to assess a patient’s emotional state.

“A diagnosis of cancer is an emotional event; it’s a life-changing moment, and a doctor wants to respond to that,” said Dr. Arif Kamal , an oncologist and the chief patient officer at the American Cancer Society. “There are things you can miss unless you’re sitting a foot or two away from the person.”

Once it’s clearer how the patient is coping and responding to treatment, that’s a good time to discuss incorporating telemedicine visits.

If a Physical Exam Seems Necessary

This may seem like a no-brainer, but there are nuances. Increasingly, monitoring equipment that people can keep at home — a blood pressure cuff, a digital glucometer or stethoscope, a pulse oximeter to measure blood oxygen, or a Doppler monitor that checks a fetus’s heartbeat — may give doctors the information they need, reducing the number of in-person visits required.

Someone’s overall physical health may help tip the scales on whether an in-person exam is needed. A 25-year-old in generally good health is usually a better candidate for telehealth than a 75-year-old with multiple chronic conditions.

But some health complaints typically require an in-person examination, doctors said, such as abdominal pain, severe musculoskeletal pain, or problems related to the eyes and ears.

Abdominal pain could signal trouble with the gallbladder, liver, or appendix, among many other things.

“We wouldn’t know how to evaluate it without an exam,” said Dr. Ryan Mire , an internist who is president of the American College of Physicians.

Unless a doctor does a physical exam, too often children with ear infections receive prescriptions for antibiotics, said Mehrotra, pointing to a study he co-authored comparing prescribing differences between telemedicine visits, urgent care, and primary care visits.

In obstetrics, the pandemic accelerated a gradual shift to fewer in-person prenatal visits. Typically, pregnancy involves 14 in-person visits. Some models now recommend eight or fewer, said Dr. Nathaniel DeNicola, chair of telehealth for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. A study found no significant differences in rates of cesarean deliveries, preterm birth, birth weight, or admissions to the neonatal intensive care unit between women who received up to a dozen prenatal visits in person and those who received a mix of in-person and virtual visits.

Contraception is another area where less may be more, DeNicola said. Patients can discuss the pros and cons of different options virtually and may need to schedule a visit only if they want an IUD inserted.

If Something Is New, or Changes

When a new symptom crops up, patients should generally schedule an in-person visit. Even if the patient has a chronic condition like diabetes or heart disease that is under control and care is managed by a familiar physician, sometimes things change. That usually calls for a face-to-face meeting too.

“I tell my patients, ‘If it’s new symptoms or a worsening of existing symptoms, that probably warrants an in-person visit,’” said Dr. David Cho , a cardiologist who chairs the American College of Cardiology’s Health Care Innovation Council. Changes could include chest pain, losing consciousness, shortness of breath, or swollen legs.

When patients are sitting in front of him in the exam room, Cho can listen to their hearts and lungs and do an EKG if someone has chest pain or palpitations. He’ll check their blood pressure, examine their feet to see if they’re retaining fluid, and look at their neck veins to see if they are bulging .

But all that may not be necessary for a patient with heart failure, for example, whose condition is stable, he said. They can check their own weight and blood pressure at home, and a periodic video visit to check in may suffice.

Video check-ins are effective for many people whose chronic conditions are under control, experts said.

When someone is undergoing treatment for cancer, certain pivotal moments will require a face-to-face meeting, said Kamal, of the American Cancer Society.

“The cancer has changed or the treatment has changed,” he said. “If they’re going to stop chemotherapy, they need to be there in person.”

And one clear recommendation holds for almost all situations: Even if a physician or office scheduler suggests a virtual visit, you don’t have to agree to it.

“As a consumer, you should do what you feel comfortable doing,” said Dr. Joe Kvedar , a professor at Harvard Medical School and immediate past board chairman of the American Telemedicine Association . “And if you really want to be seen in the office, you should make that case.”

Related Topics

- Mental Health

- Telemedicine

Copy And Paste To Republish This Story

By Michelle Andrews March 6, 2023

When the covid-19 pandemic swept the country in early 2020 and emptied doctors’ offices nationwide, telemedicine was suddenly thrust into the spotlight. Patients and their physicians turned to virtual visits by video or phone rather than risk meeting face-to-face.

“It was a dramatic shift in one or two weeks that we would expect to happen in a decade,” said Dr. Ateev Mehrotra , a professor at Harvard Medical School whose research focuses on telemedicine and other health care delivery innovations. “It’s great that we served patients, but we did not accumulate the norms and [research] papers that we would normally accumulate so that we can know what works and what doesn’t work.”

Now, three years after the start of the pandemic, we’re still figuring that out. Although telehealth use has moderated, it has found a role in many physician practices, and it is popular with patients.

But how do you gauge when to opt for a telehealth visit versus seeing your doctor in person? There are no hard-and-fast rules, but here’s some guidance about when it may make more sense to choose one or the other.

If It’s Your First Visit

“As a patient, you’re trying to evaluate the physician, to see if you can talk to them and trust them,” said Dr. Russell Kohl , a family physician and board member of the American Academy of Family Physicians. “It’s hard to do that on a telemedicine visit.”

Sometimes an in-person first visit can help doctors evaluate their patients in nontangible ways, too. After a cancer diagnosis, for example, an oncologist might want to examine the site of a biopsy. But just as important, he might want to assess a patient’s emotional state.

“A diagnosis of cancer is an emotional event; it’s a life-changing moment, and a doctor wants to respond to that,” said Dr. Arif Kamal , an oncologist and the chief patient officer at the American Cancer Society. “There are things you can miss unless you’re sitting a foot or two away from the person.”

Once it’s clearer how the patient is coping and responding to treatment, that’s a good time to discuss incorporating telemedicine visits.

This may seem like a no-brainer, but there are nuances. Increasingly, monitoring equipment that people can keep at home — a blood pressure cuff, a digital glucometer or stethoscope, a pulse oximeter to measure blood oxygen, or a Doppler monitor that checks a fetus’s heartbeat — may give doctors the information they need, reducing the number of in-person visits required.

Someone’s overall physical health may help tip the scales on whether an in-person exam is needed. A 25-year-old in generally good health is usually a better candidate for telehealth than a 75-year-old with multiple chronic conditions.

“We wouldn’t know how to evaluate it without an exam,” said Dr. Ryan Mire , an internist who is president of the American College of Physicians.

“I tell my patients, ‘If it’s new symptoms or a worsening of existing symptoms, that probably warrants an in-person visit,’” said Dr. David Cho , a cardiologist who chairs the American College of Cardiology’s Health Care Innovation Council. Changes could include chest pain, losing consciousness, shortness of breath, or swollen legs.

When patients are sitting in front of him in the exam room, Cho can listen to their hearts and lungs and do an EKG if someone has chest pain or palpitations. He’ll check their blood pressure, examine their feet to see if they’re retaining fluid, and look at their neck veins to see if they are bulging .

“The cancer has changed or the treatment has changed,” he said. “If they’re going to stop chemotherapy, they need to be there in person.”

And one clear recommendation holds for almost all situations: Even if a physician or office scheduler suggests a virtual visit, you don’t have to agree to it.

“As a consumer, you should do what you feel comfortable doing,” said Dr. Joe Kvedar , a professor at Harvard Medical School and immediate past board chairman of the American Telemedicine Association . “And if you really want to be seen in the office, you should make that case.”

We encourage organizations to republish our content, free of charge. Here’s what we ask:

You must credit us as the original publisher, with a hyperlink to our kffhealthnews.org site. If possible, please include the original author(s) and KFF Health News” in the byline. Please preserve the hyperlinks in the story.

It’s important to note, not everything on kffhealthnews.org is available for republishing. If a story is labeled “All Rights Reserved,” we cannot grant permission to republish that item.

Have questions? Let us know at KHNHelp@kff.org

More From KFF Health News

Bird Flu Is Bad for Poultry and Dairy Cows. It’s Not a Dire Threat for Most of Us — Yet.

Oh, Dear! Baby Gear! Why Are the Manuals So Unclear?

California Floats Extending Health Insurance Subsidies to All Adult Immigrants

DIY Gel Manicures May Harm Your Health

Thank you for your interest in supporting Kaiser Health News (KHN), the nation’s leading nonprofit newsroom focused on health and health policy. We distribute our journalism for free and without advertising through media partners of all sizes and in communities large and small. We appreciate all forms of engagement from our readers and listeners, and welcome your support.

KHN is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). You can support KHN by making a contribution to KFF, a non-profit charitable organization that is not associated with Kaiser Permanente.

Click the button below to go to KFF’s donation page which will provide more information and FAQs. Thank you!

Latest Issue

Psychiatry’s new frontiers

Hope amid crisis

Recent Issues

- AI explodes Taking the pulse of artificial intelligence in medicine

- Health on a planet in crisis

- Real-world health How social factors make or break us

- Molecules of life Understanding the world within us

- The most mysterious organ Unlocking the secrets of the brain

- All Articles

- The spice sellers’ secret

- ‘And yet, you try’

- Making sense of smell

- Before I go

- My favorite molecule

- View all Editors’ Picks

- Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

- Infectious Diseases

- View All Articles

Are you listening?

Modern medicine challenges the crucial bond between doctors and patients

By Patricia Hannon

Photography by Max Aguilera-Hellweg

A conversation with her oncology team helped Kimberly Allison embrace her treatment plan after a devastating diagnosis.

Kimberly Allison, MD, was 33 when her diagnosis came. She was a couple weeks into a job directing the breast cancer pathology lab at the University of Washington Medical Center and happily settling into a new routine with her husband, a preschool daughter and an infant son.

The discovery that she had the disease she devotes her career to studying was “like Alice in Wonderland, falling down the rabbit hole.”

She couldn’t protect herself from what the scientist in her knew: Young women tend to get more deadly forms of cancer. And her cancer was ugly and big, likely having spread, undetected, during her pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Related reading

One patient who struggled with being overweight for much of her life says she finally found success because of the trusting relationship she has with her doctor.

Allison , now a professor of pathology at Stanford’s School of Medicine, recalls her deep depression after the diagnosis 10 years ago, when her mind went to the “darkest places” as she scoured the internet for answers.

“Every study I looked up had a horrible outcome. I thought this was going to be a death sentence for me,” she says. “What if you only have two years left? You go there right away.” What should she do with that time? Sadness about her children overwhelmed her. Should she quit work and spend her time with them and her husband? Should she do something soul-fulfilling like writing or painting? Or keep working in a career she loves?

She wouldn’t be able to settle those thoughts until she saw her oncology team.

At the first meeting with her surgeon and two oncologists, Allison willed emotion away. She didn’t want to “be a total mess” in front of the physicians gathered around the conference room table with her and her husband. She wanted her colleagues to see her as professional and still capable of doing her job.

They discussed the characteristics of her cancer and her treatment options in a matter-of-fact way and created a plan: six months of chemotherapy, followed by surgery, then radiation. They could start right away.

But Allison was uneasy. “OK, but I’ve seen the pathology,” she told the team. “This looks really bad to me.” That’s when her surgeon, Kristine Calhoun, MD, saw through Allison’s tough facade to the fear she was struggling to keep at bay. Calhoun told her: “I know you’ve looked up your prognosis. But there are new, targeted therapies that are changing that outcome. That data is so new it’s not in the older papers about pregnancy-associated cancers.

“This is a new ballgame,” Calhoun said. “We’re talking about seeing the grandkids.”

Allison finally had hope: “That basically reset me like, ‘OK, I’m not dying. I’m not dying right now.’”

Calhoun, who is still at the University of Washington School of Medicine, says there’s a delicate balance in giving patients hope without giving them false hope, but it was important that Allison see a positive path forward.

“People who lose hope kind of will themselves into a certain pathway,” she says. Though it was sometimes difficult to treat a friend, Calhoun says she learned a lot from how Allison handled the experience.

“It taught me to have even more empathy,” she says. “It helped me learn to not just look at patients as patients but as people, and to see that it really does change their story.”

The connection between Allison and Calhoun, which grew stronger as Allison’s treatment progressed, is what Stanford physician and author Abraham Verghese , MD, calls the “most poignant of human experiences” — one of suffering and the care of people who are suffering.

“The relationship between a care provider and a patient is vitally important in determining the health and well‑being of the patient and the outcome of treatments,” says School of Medicine Dean Lloyd Minor , MD.

He notes that, historically, the most a physician could do for suffering patients was to offer comfort by being an empathetic and understanding listener. A relatively recent explosion in biomedical knowledge and therapeutic options changed that and vastly improved care. But he says it also created a “separation between the science of medicine and the humanism and compassion of medicine” that must be addressed to nurture the ability of physicians to better understand and treat their patients.

“Each patient comes with a different history, with a different social, cultural and behavioral background,” says Minor. “Those factors are going to play heavily in determining the effectiveness of whatever scientifically based therapeutics you seek to offer.”

Listening is crucial to good health care

Clinicians across the board say the current climate of medicine cuts into the time they can spend really listening to patients, which makes it difficult to form meaningful connections, says Donna Zulman , MD, assistant professor of medicine and co-director of Stanford Presence 5 , an initiative to change clinical encounters to improve overall health care. The initiative was launched by the Stanford Presence Center — founded in 2015 by Verghese to develop methods of tearing down communication barriers created by technology.

Not listening can have negative consequences downstream, such as misdiagnosis, unnecessary or unwanted treatment, patients not following through, fragmented patient care and physician burnout, Zulman says.

She is one of many people — at Stanford and elsewhere — who are working to enhance the doctor-patient relationship by creating communication skills training for clinicians; addressing physician burnout; and developing ideas for better ways to manage care, design exam rooms and improve health record interfaces.

Zulman points to two main time-robbing culprits: reimbursement models that have resulted in appointment times across the nation being set at about 15 minutes; and electronic health records that have clinicians spending more time outside of the appointments entering, reviewing and sharing patient information.

Such demands on physicians take them far from the reasons they got into medicine.

Kelley Skeff , MD, PhD, professor of medicine, who co-directs the Stanford Faculty Development Center for Medical Teachers, says doctors came to the field “to learn and apply science for the benefit of patients.”

“But their connections to science and to the patient are commonly impeded by the requirements of the system,” he says. “And those who are the most empathetic may, in fact, burn out faster as their self-care is neglected.

“We’re asking them to do the relatively superhuman tasks of keeping humanness and empathy together for others. They’re drawn to respond to the needs of both the health care system and the patient, but their own refueling process isn’t always happening.”

“We’re asking them to do the relatively superhuman tasks of keeping humanness and empathy together for others. … but their own refueling process isn’t always happening.”

Physician burnout is at an all-time high; 54 percent of physicians across the nation reported having at least one symptom of burnout, according to national research overseen in 2014 by Tait Shanafelt , MD, the chief wellness officer and director of the Stanford Medicine WellMD Center. That was up from 46 percent in 2011. A physician wellness survey the center conducted at Stanford in 2016 showed that 34 percent of physicians surveyed that year reported having at least one burnout symptom. That was up from 25 percent in 2013.

Caring for the caregiver has been neglected for years, says Minor, but change is coming. “We have to get real about this,” he says. “I think we’re starting to recognize that our physical and mental well‑being are just as important as our knowledge base and technical skills when it comes to being effective physicians.”

One key challenge, says Minor, is to better integrate technology with medicine. For example, it’s important that electronic health records be better designed and easier to use so health care professionals and patients can access and share the information — and communicate about it — in real time.

“The care-delivery experience should not be driven and determined by the technology, it should be enabled by the technology. Listening to patients and being empathetic with patients should be the priority,” he says.

Improving how we talk to each other

Good communication, Zulman says, starts with clinicians really absorbing what patients say — about themselves, their pain, values, challenges and care goals — and being empathetic.

“Now, because of pervasive technology and other distractions in the clinical setting, we’re having to be more explicit about taking time and taking actions that will help us have meaningful interactions with patients,” she says.

Still, superb communication skills don’t come naturally to everyone, even the most experienced clinicians, says Stephanie Harman , MD, clinical associate professor of medicine. Like other aspects of medicine, being a good communicator takes practice.

“Learning how to build strong patient relationships is equally as important in medicine as learning technical or procedural skills,” says Harman, a master facilitator for Advancing Communication Excellence at Stanford , a workshop designed to help clinicians enhance communication skills that are “really at the heart of how we care for patients and their families.”

Workshop participants role-play patient interactions so patient priorities are at the center of every discussion. A total of 310 clinicians have participated in the program as of April 1 and 310 more are registered to participate between now and August. Harman says they’re encouraged to suspend the impulse to rush through patient conversations and instead listen, so that amid the “all-consuming fracas” of information and tasks they manage, clinicians can “answer the most important question in the world: What does the patient need?”

“Learning how to build strong patient relationships is equally as important in medicine as learning technical or procedural skills.”

To gain a better understanding of effective doctor-patient dynamics, Presence 5 researchers are sitting in on patient interactions with primary care providers at Stanford and in primary care clinics in the Alameda Health System, Ravenswood Family Health Center in East Palo Alto and the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System.

If patients agree, researchers use video or audio devices to record the encounters. The data also will include survey feedback from the patients and physicians involved in the approximately 40 visits that are being observed. Researchers will eventually synthesize the information to help establish best practices for interacting with patients.

They’re watching, Zulman says, for moments when patients reveal valuable information about themselves, their symptoms or their social histories that can inform clinical decisions. “What happens in the minutes preceding that? What did the doctor do or say, how were they positioned, that helped the patient open up in that way?”

Learning what patients need most

John Kugler , MD, a clinical associate professor of medicine who launched Stanford Medicine 25 with Verghese nine years ago to promote bedside exam skills, emphasizes the importance of those personal interactions for both diagnostics and for building trust between the physician and patient.

When a trainee seeks Kugler’s advice about a patient, “My first answer is, ‘We can’t make that decision now. We need to see the patient first.’

“You learn so much stuff that’s between the lines. How much distress are they really in? Can they really not breathe? Can they talk to me in full sentences? How weak are they? I’m really trying to get a sense of the person,” he says. “That’s when the decision-making just gels a lot better. To me, so much of it is that initial laying eyes on someone.”

Verghese, the Linda R. Meier and John F. Lane Provostial Professor and a leading advocate for returning to the “timeless human-to-human ritual” of bedside exams, says he takes note of what’s in a hospital room before even approaching a patient.

“They’re totally out of their context,” he says. “So anything that they’ve brought from the outside world is enormously helpful.” One person might be in shackles, another might be reading a book or Bible. Or a hospital room might be filled with greeting cards and family photos. Such observations can reveal a lot about people, he says, including values, cultural backgrounds, cognitive abilities and support networks.

“So often we walk into a room and, because of what the chart says or what we notice, within moments we know what’s going on,” he says. “But the patient doesn’t know what we know. If you jump in and say, ‘Well, I know what’s going on,’ it just seems so rude. And they wonder, ‘What do you already know? I haven’t really finished telling you.’”

Letting them tell their stories in a way that shows respect for them as individuals also invites patients to be partners in their care.

When Allison was fighting stage-3 HER2-positive breast cancer, she wanted to keep working and keep normal routines for her kids. During the first six months, she had chemotherapy once a week. In between, she diagnosed patients and presented pathology to physician groups working on other cases. The schedule, she says, helped her “feel balanced and like I was still engaged in my life. And I found it actually quite nice to go to work and not be focusing on illness all day at home.”

But she also needed emotional support. That, she says, especially came from the wider team of oncology nurses and staff. Memories of their kindness still evoke tears of gratitude. “You’re sitting there for hours, sometimes for a whole day, and those are the people who come and sit next to you, hold your hand, bring you a warm blanket or food, and really get to know you as a person,” she says.

“The hope you gave or the care you gave where you made it personal makes a huge difference.”

Comfort also came from conversations with a hospital chaplain who visited the infusion ward. “Just having somebody to talk to who could bring up some big questions for you to ask yourself, about values and to reflect, was a growing experience without even going through cancer treatment,” Allison says. “It was like therapy.”

Now she meets with patients who want their pathology lab results explained, which is unusual for a pathologist, and speaks with patient groups, encouraging patients to do what they can, such as get a second opinion or learn more about treatments, so they trust and are comfortable with their care team and treatment plans.

She also speaks to physicians, challenging them to see patients quickly after a diagnosis — because “the worst time is that fearful time” of waiting — and to treat them as individuals.

“The hope you gave or the care you gave where you made it personal makes a huge difference,” she tells them. “I knew that I was getting the best treatments. But it was the personal interaction and support that I got as a patient that made a difference for me every day.”

Finding a model that works

Minor, who taught an undergraduate seminar this winter on literature, medicine and empathy, says the sense that the whole team is on your side is crucial for a patient’s motivation and healing and contributes greatly to the wellness of care providers. “Being a physician is a calling,” he says, “partly because of the enormous privilege of interacting with people in a way that establishes deep personal relationships that are unique to health care.”

Alan Glaseroff , MD, adjunct professor of medicine, is working with Arnold Milstein , MD, professor of medicine and director of Stanford’s Clinical Excellence Research Center, to develop new models of care that build on that kind of trust.

Glaseroff and his wife, Ann Lindsay , MD, left Humboldt County in 2011 to create the Stanford Coordinated Care program , basing it on their longtime family practice in Arcata, California, and on ideas gleaned from their more than 15 years of working with the Institute of Healthcare Improvement and other pioneers in the national movement to redesign primary care.

The coordinated care program is designed to cut costs for Stanford’s self-funded insurance plan by treating the 5 percent of employees and their dependents whose care represents 50 percent of the plan’s cost. The approach is meant to keep chronically ill patients from having repeated setbacks and hospital visits by making them partners in their own wellness. Every team member knows the patients well and focuses on goals the patients identify.

The core principle is to engage people, to just sit and talk with them, and show them respect, Glaseroff says. “And the way to engage with them is listening, and it’s focusing on what they care about, even if it seemed trivial compared with what we care about,” he says. “But I don’t think it is trivial. It turns out to be of critical importance.”

Glaseroff believes the practice can apply in all areas of medicine where there’s continuity. “It isn’t just come in, get something done and never see you again,” he says.

“What we figured out is that, if everybody was trained in this approach and we were really consistent with it, we got incredible efforts out of the patients.”

Zulman says she’s intrigued by the potential to address the challenges that get in the way of such successes by taking something that seems “vast and fairly abstract” and designing and implementing concrete interventions that make a difference for clinicians.

That could result in rituals that foster human connection during patient history-taking and exams or could lead to new care models where physicians spend less time interacting with electronic health records and have more autonomy to determine how much time they spend with individual patients.

“It’s actually a really challenging problem,” Zulman says. “If there were a simple solution, and all you have to do is make eye contact and we’re done, we would have figured that out already.”

Online extra:

Patricia Hannon

Patricia Hannon is the associate editor of Stanford Medicine magazine in the Office of Communications. Email her at [email protected] .

Email the author

customer experience

Understanding the whole patient, a model for holistic patient care.

Working in healthcare, I consistently encounter processes and care offerings that are very rigid and don’t match up with the individual needs and values that patients have. Commonly, I hear stories about patients not feeling heard or respected by clinicians because what is recommended to them doesn’t align with who they are and what they believe. A lot of these issues stem from the fact that, in medicine, people are traditionally triaged and cataloged by medical condition and/or need.

While identifying and understanding the medical needs of an individual is obviously crucial in effectively treating a collection of conditions, it is rather limiting as a means of capturing who a patient is as a person. A whole patient understanding is crucial. Quite simply, people don’t perceive themselves as a collection of conditions. Health is personal, intertwined with people’s individual perceptions and mindsets, with the environments in which they live and work and the people with whom they interact. While the notion of understanding people as people perhaps appears obvious, health systems still struggle to identify what information should be captured to understand a patient holistically, and how best to engage a patient in a conversation that uncovers this information. This gap leads to misalignment between the patient and care provider, which in turn leads to poor clinical outcomes and negative patient experiences.

With discussion in the industry about patient experience and the surrounding reimbursement challenges , it’s worth thinking about how healthcare might consider the whole person to deliver a better experience, geared toward positive outcomes.

What is a “whole person understanding” of a patient?

To succeed in providing health services centered around a patient, providers must meet patients where they are: functionally, emotionally, and socially. They must understand the values their patients hold, based on their makeup as a whole.

When we talk to people about how they perceive their health, they commonly describe it as a whole, inclusive of their mental state, family, and beliefs.

I was part of work completed at the Mayo Clinic's Center for Innovation which supports these findings that a holistic understanding of a patient is made up of many layers.

Graphic from Patient Type Research, completed by Meredith Dezutter, Mathew Jordan, and Kate Dudgeon on behalf of Mayo Clinic’s Center for Innovation.

At the core of every patient is his or her medical condition or need : heart disease, pregnancy, stage 3 breast cancer, or maybe weight loss. What’s important to note here is that if an individual has a number of health issues, he or she perceives their medical needs as a whole and interconnected. The individual is not focused on singular diseases, as perhaps a specialized clinician might be. From minor to major, the medical or health-related need is what defines the care request and clinical interaction. One of the individuals we spoke to as part of this work had suffered a debilitating fall, which left her with multiple medical and neurological issues. She felt that none of the physicians would take the time to sit down with her and come up with a holistic strategy. Her health issues were looked at “as one-offs, not as a whole person,” which led to disjointed and disconnected care.

Psychosocial:

Layered atop the medical is the psychosocial state : the mental and emotional state, social system, and functional capabilities of a patient. Does this person suffer from anxiety? Is he or she depressed? Does this person’s social support network and environment foster a positive psychosocial state?

One’s psychosocial state ties closely to what many refer to as the social determinants of one’s health . This layer is crucial to understand because it can either inhibit or enable a person’s ability to actively take part in caring for him or herself. For example, many people find themselves in a deep depression following a diagnosis, after realizing that their once-normal state is no longer. This was very true of another individual we spoke to as part of this work, who was suffering from Crohn’s disease and decided to see a psychiatrist who “helped me see and treat certain aspects of my condition that are not addressed medically.”

Attitudes and Beliefs:

Another component of a whole patient is one’s attitudes and beliefs , which break into two parts. First are the beliefs or perceptions one has formed over time regarding one’s health and care. These beliefs are often based on the individual’s own experiences or those of family and friends. People will often share about an overly positive or negative experience receiving care. For example, someone might recount waiting five hours at a certain emergency department (ED), or how his mother died after a failed regiment of a certain type of cancer treatment. Frequently, these negative experiences transform into vows to never return to a particular facility, or to never have a certain treatment, despite the fact that the facility may be widely regarded in a positive light or the treatment may be the best option for the patient.

The second part is the attitudinal category one falls into, which depends largely on how much involvement the individual has in his or her own health and care. A minimalist might be someone who denies a health condition or does the bare minimum recommended by a health care provider. A maximalist, on the other hand, might be someone who proactively seeks health information and is engaged in her own care planning. The attitudinal category one falls into is linked to an individual’s personal experiences or those of family and friends. This category will inevitably change over time, as one is exposed to new such experiences.

One proactive individual I met while conducting research for a past project had strong beliefs and perspectives against the use of blood transfusions. After giving birth to her premature baby, who was in critical condition, a number of physicians recommended a blood transfusion for her daughter. “I felt backed up against a wall,” she explained. “The doctors wouldn’t listen to me.” She eventually found a doctor that she felt would listen to her and she was able to discuss and land on a treatment option that didn’t require a transfusion. Her takeaway: “I learned that when I feel strongly about something, [doctors] have to explore it enough until you prove me otherwise. I like doctors that are willing to work with me [and] will work with me through my ignorance.”

Information and Communication Preferences:

The last component that makes up a whole patient is information and communication preferences : how someone learns, when someone is open to learning, how someone seeks out information, and how someone prefers to exchange information with a care team. For example, we have found a growing preference among people to email or message their doctor when they encounter a health question rather than initially scheduling an appointment, as it provides a quick and convenient response to their discrete need. Some will go as far as seeking out care teams that offer email or messaging services, or other communication methods that they value and use.