For All Pet Lovers

Do frogs travel in groups or individually?

Introduction: the curious case of frog travel patterns.

Frogs are fascinating amphibians that come in various shapes, sizes, and colors. They are known for their unique behaviors, such as vocalizations, courtship rituals, and migration. One of the questions that scientists have been curious about is whether or not frogs travel in groups or individually. Understanding frog social behavior is important for conservation efforts, as it can help us identify ways to protect their habitats and populations.

Research on Frog Social Behavior

Research on frog social behavior has revealed that some species do travel in groups, while others prefer to travel alone. Group travel can provide benefits such as increased mating opportunities, better foraging efficiency, and predator avoidance. However, it can also come with disadvantages, such as competition for resources and increased risk of disease transmission. Conversely, individual travel patterns may provide greater flexibility and independence, but can also result in greater vulnerability to predators and difficulty in finding mates.

Benefits of Group Travel for Frogs

For some frog species, group travel can be advantageous. For instance, group travel can help frogs find better foraging opportunities as they can cover more ground together. Additionally, group travel can increase the chances of finding suitable mating partners. This is particularly true for species that have complex courtship rituals where groups of males congregate at a particular location to attract females. Group travel can also provide greater protection from predators, as there are more eyes to spot potential threats.

Factors Influencing Frog Group Formation

The formation of frog groups is influenced by various factors, including the availability of resources, the presence of predators, and the mating season. When resources are scarce, frogs may be more likely to form groups to compete for access to food and water. Likewise, when predators are abundant, frogs may form groups to increase their chances of survival. During the mating season, some species may form groups to attract mates or defend territories.

The Role of Mating in Frog Grouping

Mating is a crucial factor in frog grouping behavior. Some species form temporary breeding aggregations where males congregate to attract females. These aggregations can range from a few individuals to thousands of individuals. The males use vocalizations and physical displays to attract females, and the females choose the most attractive males to mate with. Once mating is complete, the group disperses.

Food Availability and Frog Grouping

Food availability is another important factor that can influence frog grouping behavior. When food is scarce, frogs may form groups to compete for resources. This is particularly true for species that rely on specific food sources, such as insects or small fish. In some cases, groups of frogs may even cooperate to capture larger prey, such as rodents or birds.

Predator Avoidance and Frog Grouping

Predator avoidance is another factor that can influence frog grouping behavior. When predators are abundant, frogs may form groups to increase their chances of survival. This is because there are more eyes to spot potential threats, and groups can use collective defense strategies to deter predators. Some frog species may even mimic toxic or unpalatable species to deter predators.

Disadvantages of Group Travel for Frogs

Group travel is not always beneficial for frogs. For instance, competition for resources can lead to aggression and reduced food intake. Additionally, groups can be more vulnerable to disease transmission, as pathogens can spread more easily in crowded conditions. Furthermore, group travel can result in greater visibility to predators, making it easier for them to locate and attack the group.

Individual Travel Patterns in Frogs

While some frog species prefer to travel in groups, others prefer to travel alone. Individual travel patterns are more common in species that have access to abundant resources or those that are solitary by nature. For these species, individual travel can provide greater flexibility and independence.

Factors Influencing Individual Frog Travel

Factors that influence individual frog travel include habitat quality, resource availability, and reproductive status. For instance, frogs may travel longer distances to find suitable breeding locations or to escape unfavorable conditions. Additionally, individual travel can be more efficient when resources are abundant, as there is less competition for food and water.

Conclusion: The Complex Nature of Frog Travel

In conclusion, the social behavior of frogs is complex and varies among species. While some species prefer to travel in groups, others prefer to travel alone. Group travel can provide benefits such as increased mating opportunities, better foraging efficiency, and predator avoidance. However, it can also come with disadvantages, such as competition for resources and increased risk of disease transmission. Individual travel patterns can provide greater flexibility and independence, but can also result in greater vulnerability to predators and difficulty in finding mates.

Future Directions for Frog Social Behavior Research

Future research on frog social behavior should focus on understanding the mechanisms that influence group formation and individual travel patterns. This includes investigating the role of environmental factors, such as climate change and habitat fragmentation, on frog social behavior. Additionally, research should explore the potential impact of anthropogenic activities, such as habitat destruction and pollution, on frog populations. Understanding frog social behavior is crucial for developing effective conservation strategies to protect these fascinating amphibians.

Recommended

- What is the method by which frogs travel on land?

- Would Amazon frogs consume ants?

- With what do frogs hear?

- With such small lungs, how do frogs manage to survive?

- Will african dwarf frog jump out of tank?

Dr. Chyrle Bonk

Leave a comment cancel reply.

10 Fast Facts About Amphibians

The Evolutionary Link Between Living on Land or in Water

- Habitat Profiles

- Marine Life

- B.S., Cornell University

Amphibians are a class of animal that represents a crucial evolutionary step between water-dwelling fish and land-dwelling mammals and reptiles. They are among the most fascinating (and rapidly dwindling) animals on earth.

Unlike most animals, amphibians such as toads, frogs, newts, and salamanders finish up much of their final development as an organism after they are born, changing from marine-based to land-based lifestyles in the first few days of life. What else makes this group of creatures so fascinating?

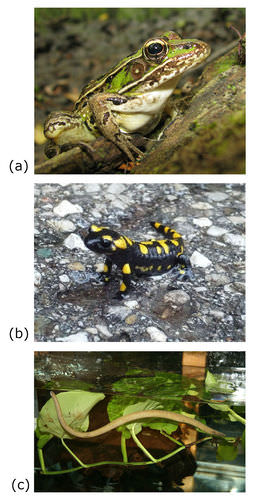

There Are Three Major Types of Amphibians

Robert Trevis-Smith / Getty Images

Naturalists divide amphibians into three main families: frogs and toads; salamanders and newts; and the strange, worm-like, limbless vertebrates called caecilians. There are currently about 6,000 species of frogs and toads around the world, but only one-tenth as many newts and salamanders and even fewer caecilians.

All of the living amphibians are technically classified as lissamphibians (smooth-skinned); but there are also two long-extinct amphibian families, lepospondyls, and temnospondyls, some of which attained astonishing sizes during the later Paleozoic Era .

Most Undergo Metamorphosis

Johner Images / Getty Images

True to their evolutionary position halfway between fish and fully terrestrial vertebrates, most amphibians hatch from eggs laid in water and briefly pursue a fully marine lifestyle, complete with external gills. These larvae then undergo a metamorphosis in which they lose their tails, shed their gills, grow sturdy legs, and develop primitive lungs, at which point they can scramble up onto dry land.

The most familiar larval stage is the tadpoles of frogs , but this metamorphic process also occurs (a bit less strikingly) in newts, salamanders, and caecilians.

Amphibians Must Live Near Water

Franklin Kappa / Getty Images

The word "amphibian" is Greek for "both kinds of life," and that pretty much sums up what makes these vertebrates special: they have to lay their eggs in the water and require a steady supply of moisture in order to survive.

To put it a bit more plainly, amphibians are perched midway on the evolutionary tree between fish, which lead a fully marine lifestyle, and reptiles and mammals, which are fully terrestrial and either lay their eggs on dry land or give birth to live young. Amphibians may be found in a variety of habitats near or in water or damp areas, such as streams, bogs, swamps, forests, meadows, and rainforests.

They Have Permeable Skin

Jasius / Getty Images

Part of the reason amphibians have to stay in or near bodies of water is that they have thin, water-permeable skin; if these animals ventured too far inland, they would literally dry up and die.

To help keep their skin moist, amphibians are constantly secreting mucous (hence the reputation of frogs and salamanders as "slimy" creatures), and their dermis is also studded with glands that produce noxious chemicals, meant to deter predators. In most species, these toxins are barely noticeable, but some frogs are sufficiently poisonous to kill a full-grown human being.

They Are Descended From Lobe-Finned Fish

Nobu Tamura / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.5

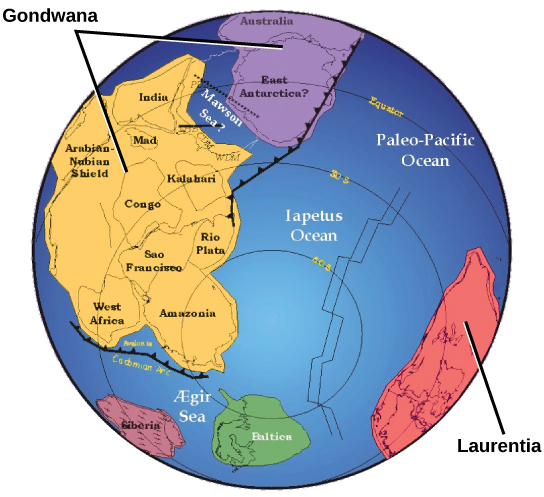

At some time during the Devonian period, about 400 million years ago, a brave lobe-finned fish ventured onto dry land—not a one-time event, as is often depicted in cartoons, but numerous individuals on numerous occasions, only one of which went on to produce descendants that are still alive today.

With their four limbs and five-toed feet, these ancestral tetrapods set the template for later vertebrate evolution, and various populations went on over the ensuing few million years to spawn the first primitive amphibians like Eucritta and Crassigyrinus.

Millions of Years Ago, Amphibians Ruled the Earth

Corey Ford / Stocktrek Images / Getty Images

For about 100 million years, from the early part of the Carboniferous period about 350 million years ago to the end of the Permian period about 250 million years ago, amphibians were the dominant terrestrial animals on earth. Then they lost pride of place to various families of reptiles that evolved from isolated amphibian populations, including archosaurs (which eventually evolved into dinosaurs) and therapsids (which eventually evolved into mammals).

A classic temnospondyl amphibian was the big-headed Eryops , which measured about six feet (about two meters) from head to tail and weighed in the neighborhood of 200 pounds (90 kilograms).

They Swallow Their Prey Whole

archerix / Getty Images

Unlike reptiles and mammals, amphibians don't have the ability to chew their food; they're also poorly equipped dentally, with only a few primitive "vomerine teeth" in the front upper part of the jaws that allow them to hold onto wriggling prey.

Somewhat making up for this deficit, though, most amphibians also possess long, sticky tongues, which they flick out at lightning speeds to snag their meals; some species also indulge in "inertial feeding," clumsily jerking their heads forward in order to slowly stuff prey toward the back of their mouths.

They Have Extremely Primitive Lungs

Photography by Mangiwau / Getty Images

Much of the progress in vertebrate evolution goes hand-in-hand (or alveolus-in-alveolus) with the efficiency of a given species' lungs. By this reckoning, amphibians are positioned near the bottom of the oxygen-breathing ladder: Their lungs have a relatively low internal volume, and can't process nearly as much air as the lungs of reptiles and mammals.

Fortunately, amphibians can also absorb limited amounts of oxygen through their moist, permeable skin, thus enabling them, just barely, to fulfill their metabolic needs.

Like Reptiles, Amphibians Are Cold-Blooded

Azureus70 / Getty Images

Warm-blooded metabolisms are usually associated with more "advanced" vertebrates, so it's no surprise that amphibians are strictly ectothermic—they heat up, and cool down according to the ambient temperature of the surrounding environment.

This is good news in that warm-blooded animals have to eat much more food to maintain their internal body temperature, but it's bad news in that amphibians are extremely limited in the ecosystems in which they can thrive in—a few degrees too hot, or a few degrees too cold, and they will immediately perish.

Amphibians Are Among the World's Most Endangered Animals

tarasue / Getty Images

With their small size, permeable skins and dependence on easily accessible bodies of water, amphibians are more vulnerable than most other animals to endangerment and extinction; it's believed that half of all the world's amphibian species are directly threatened by pollution, habitat destruction, invasive species, and even the erosion of the ozone layer.

Perhaps the greatest threat to frogs, salamanders, and caecilians is the chytrid fungus, which some experts maintain is linked to global warming and has been decimating amphibian species worldwide.

- The 3 Basic Amphibian Groups

- 10 Steps of Animal Evolution

- 300 Million Years of Amphibian Evolution

- Meet 12 Interesting Amphibians

- Reptile or Amphibian? An Identification Key

- Prehistoric Amphibian Pictures and Profiles

- 10 Extinct or Nearly Extinct Amphibians to Know More About

- Tetrapods: The Fish Out of Water

- The Basics of Vertebrate Evolution

- Tetrapods: the Four-By-Fours of the Vertebrate World

- 10 Facts About Reptiles

- 10 Missing Links in Vertebrate Evolution

- 6 Basic Animal Classes

- All About the Axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum)

- Top 10 Facts About Frogs

- The Carboniferous Period (350-300 Million Years Ago)

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

Leaping forward for reptiles and amphibians

Croaking Science: Amphibian Orientation and Migration

February 27, 2017 by admin

Spring is a time when pond-breeding amphibians within temperate areas return to breeding sites. Although amphibians do not migrate as far as birds and mammals, they often have to traverse difficult terrain, such as dense scrub or long grass and they may have few distinctive visual cues. Individual amphibians have been observed to return to the same breeding site year after year which demonstrates an ability to use external cues to navigate successfully back to their breeding ponds.

Within Europe, after leaving breeding ponds in the summer or autumn, amphibians will often travel considerable distances away from breeding ponds, which may take many months. For example the common toad may migrate between 50 m and 5 km from breeding sites. Research has shown that amphibians probably use a range of methods to navigate which may include: visual, olfactory, auditory, celestial, lunar and magnetic cues. However, not all species can use all techniques. For example, some species are able to use magnetic cues, while others are not.

Research on the smooth newt ( Lissotriton vulgaris ) and great crested newt ( Triturus cristatus ) suggests that individuals use predominantly olfactory cues (e.g. pond chemical cues) to navigate towards breeding ponds. If displaced outside their normal migratory range of a few hundred metres individuals are unable to return. These species seem unable to navigate using celestial or magnetic cues and suggests that individuals lack an internal spatial map. This is in contrast to the palmate newt ( L. helveticus ) and alpine newt ( Ichthyosaura alpestris ) which in addition to using olfactory cues, also use a geomagnetic compass to find their breeding ponds. Individual palmate newts can successfully navigate back to breeding ponds even if displaced up to 19 km outside their natural range.

Recent research suggests that auditory cues from calling anurans (frog and toads) may also play a role in orientation and navigation in newts. In a study on the palmate newt, individuals were able to orient towards breeding ponds based on the calls of the sympatric common toad ( Bufo bufo ), but not common frog ( Rana temporaria ). In addition, research on the great crested newt also indicates that adults are able to navigate using calls of the common toad but not the common frog, which is probably due to the non-overlapping breeding season of the common frog with great crested newts. Individuals also appear to avoid white noise and the ability to distinguish between the calls of different anurans may be learned.

Methods of orientation may not be the same within individuals of the same species. Male natterjack toads appear to use different methods of orientation compared to females. This species breeds in highly ephemeral water bodies, the location of which is not entirely predictable from year to year due to variations in rainfall over the winter. After the winter, males will start searching for ponds using predominantly visual cues; olfactory cues appear to be less important. Magnetic cues may be used if individuals are a considerable distance from a pond. Once at water bodies, males start calling for females. In contrast to males, the females do not employ visual, olfactory or magnetic cues but orient using the calls of the males. Ponds with louder calls attract more females.

There is increasing evidence that the moon may play a role in navigation as the large arrival and amplexus events and large spawning events of common frogs and toads are more frequent around full moon at a range of European sites.

Overall it appears that amphibians use a range of methods to correctly orientate towards breeding sites and the techniques employed vary depending on species, sex, breeding strategy and migratory behaviour. However we still have a lot to learn about how these, especially lunar cues, are used in many amphibian species and how increased artificial light levels or sound levels may negatively impact on their ability to correctly navigate back to breeding ponds in the spring.

Laurence Jarvis, Froglife Conservation Co-ordinator

Diego-Rasilla, F.J., Luengo, R.M. and Phillips, J.B. (2008) Use of a magnetic compass for nocturnal homing orientation in the palmate newt, Lissotriton helveticus . Ethology , 114 : 808-815.

Diego-Rasilla, F.J. and Luego, R.M. (2007) Acoustic orientation in the palmate newt Lissotriton helveticus . Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology , 61 (11): 1329-1335.

Grant, R. A., Chadwick, E. A. and Halliday, T. (2009) The lunar cycle: a cue for amphibian reproductive phenology? Animal Behaviour , 78 : 349-357.

Kovar, R., Brabec, M., Vita, R. and Bocek, R. (2009) Spring migration distances of some central European amphibian species. Amphibia-Reptilia , 30 : 367-378.

Maddon, N. and Jehle, R. (2017) Acoustic orientation in the great crested newt ( Triturus cristatus ). Amphibia-Reptilia , 38 (1): 57-65.

Sinsch, U., Schäfer, R. and Sinsch, A. (2006) The homing behaviour of displaced smooth newts Triturus vulgaris . In: M. Vences, J. Köhler, T. Ziegler, W. Böhme (eds): Herpetologia Bonnensis II.

Proceedings of the 13th Congress of the Societas Europaea Herpetologica . pp. 163-166.

Sinsch, U. (2010) Sex-biased site fidelity and orientation behavior in reproductive natterjack toad (Bufo calamita). Ethology, Ecology and Evolution , 4 : 15-32.

Sinsch, U. and Kirst, C. (2016) Homeward orientation of displaced newts ( Triturus cristatus , Lissitroton vulgaris ) is restricted to the range of routine movements. Ethology, Ecology and Evolution , 28 (3): 312-328.

- Info & advice

- What’s new

- Become a Friend

- Our supporters

- Privacy Information

Froglife (Head Office) Brightfield Business Hub Bakewell Road Peterborough PE2 6XU [email protected]

Please click "Accept" to use cookies on this website. More information Accept

The cookie settings on this website are set to "allow cookies" to give you the best browsing experience possible. If you continue to use this website without changing your cookie settings or you click "Accept" below then you are consenting to this.

- Science Notes Posts

- Contact Science Notes

- Todd Helmenstine Biography

- Anne Helmenstine Biography

- Free Printable Periodic Tables (PDF and PNG)

- Periodic Table Wallpapers

- Interactive Periodic Table

- Periodic Table Posters

- How to Grow Crystals

- Chemistry Projects

- Fire and Flames Projects

- Holiday Science

- Chemistry Problems With Answers

- Physics Problems

- Unit Conversion Example Problems

- Chemistry Worksheets

- Biology Worksheets

- Periodic Table Worksheets

- Physical Science Worksheets

- Science Lab Worksheets

- My Amazon Books

Amphibians – Definition, Examples, Characteristics

Amphibians are a fascinating and diverse group of animals that play a crucial role in many ecosystems. These creatures live both in water and on land. Let’s explore their characteristics, life cycle, evolutionary history, and classification.

What Is an Amphibian?

Amphibians are ectothermic (cold-blooded) vertebrates that belong to the Class Amphibia. A defining characteristics is their ability to live both in aquatic and terrestrial environments. The term “amphibian” is derived from the Greek words “amphi” (both) and “bios” (life), reflecting their dual lifestyle. They lack scales, instead having moist skin.

Characteristics of Amphibians

Amphibians share several characteristics that distinguish them from other animals:

- Dual Life Cycle: Most amphibians have a life cycle that includes both aquatic and terrestrial phases.

- Skin: Amphibians typically have moist, permeable skin that assists in respiration.

- Cold-blooded: Amphibians are ectothermic, meaning they regulate their body temperature through external sources.

- Reproduction: Amphibians usually lay eggs in water, and most have an aquatic larval stage (e.g., tadpoles in frogs).

- Respiration: Amphibians breathe through their skin, lungs, and gills at different life stages.

Characteristics Shared by Amphibians and Other Vertebrates

Amphibians, like other vertebrates, share a range of characteristics that define their biological classification. Here’s a list of key characteristics that amphibians share with other vertebrates:

- Vertebral Column: Amphibians have a spine or vertebral column, which is a defining characteristic of all vertebrates. This provides structural support and protection for the spinal cord.

- Endoskeleton: Amphibians have an internal skeleton (endoskeleton) made up of bone and cartilage. This structure provides support and facilitates movement.

- Brain Encased in a Skull: Their brains are encased in a hard skull, providing protection to this vital organ, a common feature among vertebrates.

- Bilateral Symmetry: They exhibit bilateral symmetry, meaning their body can be divided into two identical halves along a central axis.

- Complex Organ Systems: They possess complex organ systems, including a heart and circulatory system, lungs (in adult stages for most species), a digestive system, and a nervous system.

- Closed Circulatory System: Amphibians have a closed circulatory system with a heart that pumps blood through their body, which is a common feature in vertebrates.

- Sexual Reproduction: They generally reproduce sexually, with the male and female producing gametes (sperm and eggs, respectively).

- Development from Embryos: The development of amphibians, like other vertebrates, begins with embryos. Amphibians typically lay eggs, which is common in many vertebrate groups.

- Ectothermic Metabolism: Like reptiles and fish, amphibians are ectothermic, meaning they rely on external sources to regulate their body temperature.

Table Comparing Amphibians With Other Vertebrates

Here’s a comparative table that highlights key differences and similarities among amphibians and other major groups of vertebrates: mammals, reptiles, birds , and fish. Note that there are exceptions within each class.

Examples of Amphibians and Non-Amphibians

Examples of amphibians.

- Frogs and Toads (e.g., the American Bullfrog, the Common Toad)

- Salamanders (e.g., the Tiger Salamander, axolotls)

- Newts (e.g., the Eastern Newt)

Animals That Are Not Amphibians

- Reptiles (e.g., snakes, lizards)

- Mammals (e.g., humans, cats)

- Birds (e.g., eagles, sparrows)

- Fish (e.g., eels, sharks)

- Invertebrates (e.g., crabs, earthworms)

For examples, turtles, eels, lizards, and fish are not amphibians. Fish (which include eels) live in water, but they have scales and do not have lungs. Lizards resemble salamanders and newts, but they have scales and have lungs all their lives. Like lizards, turtles are reptiles.

Amphibian Life Cycle

The life cycle of amphibians has three stages:

- Egg Stage: Amphibians lay eggs, usually in water.

- Larval Stage: Larvae (e.g., tadpoles) live in water and breathe through gills. Most species undergo a metamorphosis into an adult form.

- Adult Stage: Adult amphibians typically live on land and breathe with lungs and through their skin. There are exceptions, like the axolotl, which has lungs, but lives in water and usually breathes through its gills.

Evolutionary History of Amphibians

Amphibians evolved from fish around 370 million years ago during the Devonian period. This transition from water to land was a significant evolutionary step, leading to the development of limbs and lungs. Amphibians were the first vertebrates to adapt to a terrestrial lifestyle, paving the way for reptiles, birds, and mammals.

Classification of Amphibians

The Class Amphibia has three main orders:

- Characteristics: Tailless, long hind legs for jumping, smooth or warty skin.

- Examples: American Bullfrog, Common Toad

- Characteristics: Elongated bodies, tails, and smooth, moist skin.

- Examples: Tiger Salamander, Japanese Giant Salamander

- Characteristics: Legless, worm-like, mostly burrowing.

- Example: Common Caecilian

Interesting Amphibian Facts

Here’s a collection of interesting and unusual facts about them:

- Amazing Regenerative Abilities: Some species of salamanders, like the axolotl, regenerate lost body parts, including limbs, tail, heart, and parts of their brain and spinal cord.

- Biofluorescence: Certain species of frogs and salamanders exhibit biofluorescence, where they absorb light and re-emit it as a different color. This phenomenon is especially visible under ultraviolet light .

- Diverse Communication: Beyond the well-known croaking of frogs, amphibians use various forms of communication, including visual signals, body postures, and chemical signals.

- Extreme Survival: The wood frog of North America can survive being frozen solid during winter. Its heart stops, and ice crystals form in its blood, yet it revives in the spring. Other amphibians living in cold climate experience brumation , which is a period of dormancy.

- Estivation: Meanwhile, some amphibians undergo estivation , a state of dormancy during hot and dry periods. They burrow underground and remain inactive to conserve moisture.

- Poisonous Species: The skin of some amphibians, like the poison dart frog, contains potent toxins. Indigenous tribes have used these toxins for centuries to poison the tips of their darts.

- Unique Breeding Strategies: For example, the Surinam toad carries its eggs on its back where they develop. Once the development is complete, the young toads emerge fully formed from pockets in the skin.

- Variation in Size: Amphibians vary greatly in size. The smallest, like the Paedophryne amauensis (a frog from Papua New Guinea), measures just 7.7 mm, while the largest, like the Chinese giant salamander, grows over 1.8 meters long.

- Sensory Perceptions: Some amphibians have highly developed sensory systems. For example, caecilians, which are mostly blind, have tentacles that help them detect chemicals in their environment.

- Respiration Variations: While many amphibians develop lungs, some retain gills throughout their lives. Others, like the lungless salamanders, rely entirely on skin and mouth lining for gas exchange.

- Longevity: Some amphibians have surprisingly long lifespans. For instance, the European common toad can live for more than 40 years.

- Color Changes: Many amphibians change their skin color for various reasons, including camouflage, temperature regulation, and mood expression.

- Dorit, R. L.; Walker, W. F.; Barnes, R. D. (1991). Zoology . Saunders College Publishing. ISBN 978-0-03-030504-7.

- Lamb, Jennifer Y.; Davis, Matthew P. (2020). “Salamanders and other amphibians are aglow with biofluorescence”. Scientific Reports . 10 (1): 2821. doi: 10.1038/S41598-020-59528-9

- San Mauro, Diego; Vences, Miguel; Alcobendas, Marina; Zardoya, Rafael; Meyer, Axel (2005). “Initial diversification of living amphibians predated the breakup of Pangaea”. The American Naturalist . 165 (5): 590–599. doi: 10.1086/429523

- Schoch, Rainer R. (2014). Amphibian Evolution: The Life of Early Land Vertebrates . John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118759134.

- Wells, Kentwood D. (2010). The Ecology and Behavior of Amphibians . University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226893334.

Related Posts

Parking will be extremely limited in the N1 lot adjacent to the Burke Thursday, May 2 and Saturday, May 4. Please see our Directions & Parking page for alternative parking and public transit options if you're visiting on these days. The Burke Museum will be closed Friday, May 3 for our annual spring fundraiser. We will open again at 10 a.m. on Saturday, May 4. Plan your visit .

Search Collections Databases

All about amphibians, where does the name amphibian come from .

The word amphibian is a Greek word. It is the combination of the world “amphi,” which means dual, or both kinds and the word “bio,” which means life. The translation would be ‘of both kinds of life’. This definition refers to the fact that most amphibians live their lives in two different stages in two different environments…water and land, first as tadpoles and then as terrestrial adult frogs.

This is true for many species, but there are a lot of amphibians that do not follow this life strategy. Some salamanders do not have an aquatic larval stage. Some amphibians are fully aquatic and do not go through metamorphosis into adults (axolotls).

Pacific Tree Frog.

How many amphibians are there in the world?

As of September 2012 , there are 7,037 known amphibian species. They are broken down as follows: Anurans (frogs and toads:) 6,027 in 53 families. Caudata (salamanders): 639 in 10 families. Gymnophiona (Caecilians): 191 in 10 families.

How do amphibians breathe?

Most amphibians breathe through lungs and their skin. Their skin has to stay wet in order for them to absorb oxygen so they secrete mucous to keep their skin moist (If they get too dry, they cannot breathe and will die). Oxygen absorbed through their skin will enter blood vessels right at the skin surface that will circulate the oxygen to the rest of the body. Sometimes more than a quarter of the oxygen they use is absorbed directly through their skin. Tadpoles and some aquatic amphibians have gills like fish that they use to breathe. There are a few amphibians that do not have lungs and only breathe through their skin.

Can amphibians smell?

Yes, amphibians can smell. They have tiny openings on the roof of their mouth called external nares that take in different scents directly into their mouths. The external nares also help them breathe, just like our noses do. In some species, like many salamanders, they rely on chemical cues called pheromones for mating.

Do amphibians have teeth?

Yes, a lot of amphibians have teeth. However, they do not have the same kind of teeth that we have. They have what are called vomerine teeth that are only located on the upper jaw and are only in the front part of the mouth. These teeth are used to hold onto prey and not used to actually chew or tear apart prey. Amphibians swallow their prey whole, so they do not need teeth for chewing. They are called vomerine because they are found in the facial bone called the vomer.

What do amphibians eat?

Amphibians will pretty much eat anything live that they can fit in their mouths! This includes bugs, slugs, snails, other frogs, spiders, worms, mice or even birds and bats (if the frog is big enough and the bird or bat small enough). A few species will eat only one particular food like some smaller frogs might specialize on ants or termites. Some particularly voracious frogs/toads like the cane toad have been known to eat non- live food such as dog or cat food! Aquatic amphibians will eat bugs, other amphibians including tadpoles, fish and small aquatic organisms. There is only one frog species known that is actually a vegetarian: The Brazilian Tree frog eats fruits and berries!

What do tadpoles eat?

Most tadpoles eat plants and algae in the water. They are important grazers in aquatic systems because they help with nutrient recycling and control algae populations, which help to maintain the health of freshwater ecosystems. Sometimes tadpoles will eat each other, especially if food resources are low. Some tadpoles eat insect larvae and tiny organisms that are found in the water.

Are amphibians only active at night?

Although many species are only active at night, there are some that are active during the day. Amphibians are usually active at night because they are harder to see and can avoid being eaten. It is also easier to avoid drying out when the sun isn’t shining down on them. Poisonous amphibians that are brightly colored are often active during the day. Bright colors on an animal will warn predators that they are poisonous, so they do not have to worry about predators. They avoid drying out by living in forests or undergrowth where it is damp and the sun isn’t able to dry them out.

Do amphibians hibernate? What do frogs/salamanders do in winter?

Yes, there are many amphibians that hibernate. Amphibians do not like extreme temperatures. During the cold winter months in non-tropic areas, most amphibians will either hibernate in the mud at the bottom of water or dig down into the ground to hibernate. Some amphibians stow away in cracks in logs or between rocks during the winter. They slow their metabolism and their heartbeats down and survive off stored body reserves throughout the winter. There are some frog species that can even survive freezing temperatures by maintaining a high level of glucose in their blood that acts like antifreeze. Some of the frog will actually freeze, like their bladder, but their blood and vital organs do not freeze. The heart can stop beating and the frog can stop breathing, but it when it thaws out, it will still be alive.

Are all amphibians poisonous?

No, only some species of amphibians are poisonous. Usually they are brightly colored to warn predators of their toxic nature. Most amphibians secrete chemicals from their skin to make them taste icky to predators or make it difficult to handle them. These secretions can be slippery or can be sticky and irritating to the skin.

Amphibians & Reptiles of Washington

Do you know where rattlesnakes live in our state? Or which salamander breathes through its skin? Explore the fascinating diversity of the 26 species of amphibians and 28 reptiles found in Washington state.

Become a member

Experience even more. A membership pays for itself in 3 visits!

Just want tickets?

Continue to general admission tickets page.

Buy tickets

Looking for a special event?

View calendar

Frogs: The largest group of amphibians

Fun facts and frequently asked questions about frogs, the largest and most diverse group of amphibians on Earth.

Frogs vs. toads

Types of frog.

- Hibernation

- Poisonous frogs

- Conservation status

Additional resources

Frogs and toads make up the largest group of amphibians. Species in this order, called Anura, substantially outnumber those in the two other living orders of amphibians — Caudata (salamanders) and Gymnophiona (caecilians). As of August 2022, Anura had 7,486 of the 8,478 known amphibian species, according to Amphibian Species of the World , a reference website from the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Frogs and toads are among the most diverse animal groups. Though they might be most famous for their croaking and jumping, these animals have a wide variety of unique traits and behaviors. Like many other animals, frogs and toads are suffering greatly from human-related threats, and many species face imminent extinction.

"Frog" and "toad" are common names that don't mean much from a scientific perspective. "Frog" can be thought of as the more encompassing word as it's the common name for the Anura order, and used in the common names of most of Anura's species. "Toad" is used more selectively in the common names of certain species or groups.

Amphibians with "toad" in their common names often have characteristics that are not typically thought of as frog-like. For example, "toads" usually live in drier habitats — and have drier, bumpier skin and shorter hindlimbs — than is typical for frogs, according to the Burke Museum in Seattle. However, all toads can be called frogs.

Related: What's the difference between a frog and a toad?

Frogs come in a variety of shapes, colors and sizes. The largest frogs are Goliath frogs ( Conraua goliath ) from Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea; they can grow to be more than 1.1 feet (34 centimeters) long and weigh 7.3 pounds (3.3 kilograms), according to a 2019 study published in the Journal of Natural History . Goliath frogs appear to use their great size to shift rocks weighing more than 4 pounds (2 kg) to build " nursery ponds " that they clean and guard, Live Science previously reported.

The world's smallest known frog is a tiny species called Paedophryne amauensis from Papua New Guinea. Described in a 2012 study published in the journal PLOS One , this frog grows to an average length of 0.3 inch (7.7 millimeters), making it the smallest known vertebrate on Earth , Live Science previously reported.

Frogs are famed for their fantastic jumping skills, but not all frogs hop. Waxy monkey tree frogs ( Phyllomedusa sauvagii ) walk along branches, gripping them like monkeys do. These South American frogs secrete a natural opioid called dermorphin, which is many times stronger than morphine and has been used to create an illegal performance-enhancing drug for racing horses , according to the World Wildlife Fund .

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Amphibia

Order: Anura

Source: ITIS

Many frogs utilize camouflage, whether it's to stay hidden from predators or blend into their environment so prey don't notice them. For example, Vietnamese mossy frogs ( Theloderma corticale ) from Vietnam resemble clumps of moss. Poison dart frogs are called the "jewels of the rainforest" because they come in various colors that warn predators they're toxic and shouldn't be eaten. However, even these bright colors can act as camouflage in a vibrant rainforest.

Glass frogs have translucent green skin that makes their internal organs, and even beating hearts, visible to the human eye. They've evolved for predators to look straight through them. A 2020 study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) found that these frogs aren't truly transparent, but their camouflage is flexible.

"The frogs are always green but appear to brighten and darken depending on the background," lead author James Barnett , a behavioral ecologist at McMaster University in Ontario, said in a statement at the time. "This change in brightness makes the frogs a closer match to their immediate surroundings, which are predominantly made up of green leaves."

While there are thousands of known frog species, there are likely many more that scientists haven't found yet. For example, researchers described six new species from Mexico in April 2022, and each can fit comfortably on a thumbnail . The researchers noted at the time that the frogs could represent the tip of a giant iceberg of unknown amphibians just in Mexico, Live Science previously reported.

Related: Adorable 'chocolate frog' discovered in crocodile-infested swamp

Where do frogs live?

Frogs are found on every continent except Antarctica . They need to be around water sources to reproduce, but their habitats are extremely varied otherwise. Poison dart frogs hop through the tropical rainforests of Central and South America, while northern leopard frogs ( Lithobates pipiens ) inhabit much of North America's marshlands, brushlands and other habitats, including farmland and golf courses, according to the University of Michigan's BioKids website.

Some species live in highly specialized environments. For example, Vietnamese mossy frogs live in mossy, flooded caves and the banks of rocky mountain streams around 2,300 to 3,300 feet (700 to 1,000 meters) above sea level, according to the Smithsonian's National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute in Washington, D.C. Meanwhile, desert rain frogs ( Breviceps macrops ) appear to live exclusively in the white sand dunes of Namibia and South Africa, burrowing into the sand during the day and feeding at night, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Frogs have lungs , but they can also breathe through their skin by absorbing oxygen from water. They can still drown if their lungs fill with water or there's not enough oxygen in the water they're swimming in, according to the Burke Museum.

What do frogs eat?

Frogs have a wide diet that includes insects, spiders, worms, slugs, larvae and small fish. These amphibians play a vital role in the world's ecosystems by helping to keep insect populations under control, according to the San Diego Zoo. They catch prey using their quick, sticky tongues. A 2017 study published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface found that frog tongues can catch insects in 0.07 second — five times faster than the blink of a human eye.

Related: Watch this frog light up after it swallows a firefly

Some frogs seek out much larger prey than flies and slugs. For example, cane toads ( Rhinella marina ), which typically grow to 9 inches (23 cm) in length, scarf down small birds, mammals and snakes with ease, as well as other amphibians and even table scraps and pet food, according to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission . Their native range stretches from the Amazon basin in South America up to southern Texas. But humans have introduced cane toads elsewhere, and their insatiable appetites can be a big problem for wildlife. They are an invasive species in areas such as Florida and Australia, where they compete with native amphibians and poison animals that try to feed on them, including pets and, in Australia's case, endangered species such as Tasmanian devils ( Sarcophilus harrisii ), according to the San Diego Zoo.

How do frogs reproduce?

Frogs have many mating strategies, and scientists are still learning about these animals' sex lives. For most species, mature males initiate the breeding process by calling loudly to tell females they are ready to mate, according to the Australian Museum in Sydney. Females filled with eggs approach calling males and choose one to mate with, usually in water. Fertilized eggs, or frog spawn, can incubate for anywhere between 48 hours and 23 days before hatching, depending on the species, according to the San Diego Zoo. Small, legless, fish-like tadpoles emerge from the eggs and begin life feeding on algae.

Tadpoles' transformation into mature frogs starts with the release of hormones from their thyroid glands, according to the book " Developmental Biology " (Sinauer Associates, 2000). Over time, tadpoles grow legs, lose their tails and emerge from the water capable of living on land. The word "amphibian" comes from the Greek words "amphi" and "bios," which translate to "both life," because they live in water and on land, according to the Oxford Learner's Dictionaries .

Related: 'Ancient death trap' preserved hundreds of fossilized frogs that drowned during sex

Do frogs hibernate?

Frogs are ectothermic, or "cold-blooded," like other amphibians, reptiles and snakes. This means they can't regulate their own body temperature internally like mammals do, and they rely on the external environment to stay warm, according to Froglife , a conservation charity based in the U.K. To survive winter in colder environments, frogs may go into a state of dormancy, called brumation, underwater or under log piles. Brumation is similar to hibernation, except frogs may occasionally emerge from their dormant state to eat.

Wood frogs ( Lithobates sylvaticus ) have an even more extreme winter survival strategy to survive in the northern forests of Alaska and Canada: They allow ice to fill their abdominal cavities and encase their internal organs. In this state, wood frogs' hearts stop beating and they appear to be frozen solid, but they're still alive in a state of suspended animation. The frogs survive because their livers produce glucose that prevents their cells from freezing. They begin to thaw out in spring , and at some point — though scientists aren't sure how — their hearts start beating again and they go on their way, according to the National Park Service .

Are frogs poisonous?

The bumps on amphibians' skin aren't warts, and people can't contract warts from handling these animals. The myth that people can get warts from frogs likely stems from the wart-like appearance of the bumps, according to the Burke Museum. However, many frogs produce poisonous secretions that can irritate human skin or cause serious harm if ingested. For example, the most toxic poison dart frogs in the genus Phyllobates produce batrachotoxin, which disrupts the human body 's nervous system and can cause paralysis, extreme pain and heart failure. As well as potential toxins, frogs can carry bacteria and parasites, according to the Burke Museum.

The secretions of frogs have played an important role in the development of human medicine; they're used, for example, to make painkillers and antibiotics . Furthermore, around 10% of physiology and medicine Nobel Prize winners used frogs as part of their research, according to Save the Frogs , an amphibian conservation charity based in California.

— Toxic cane toads are invading Taiwan. Conservationists race to contain warty amphibians.

— Massive great white shark Unama'ki spotted south of Miami

— Frogs, toads, lizards and bats ... were found in bagged salads

A few frogs are venomous as well as poisonous. Poison is harmful if ingested, but animals are venomous if they inject their toxins. A 2015 study published in the journal Current Biology found that two Brazilian frog species possessed bony spines on their skulls that they could use like venomous fangs. These frogs, called Bruno's casque-headed frogs ( Aparasphenodon brunoi ) and Greening's frogs ( Corythomantis greeningi ), headbutt potential predators to stab them with the spines and transfer toxins, according to the Natural History Museum in London.

Related: Frogs' skulls are more bizarre (and beautiful) than you ever imagined

Are frogs endangered?

Amphibians are the most threatened group of vertebrates on Earth; 40% of the amphibian species assessed by the IUCN are at risk of extinction. This means that many frog species are declining and need help from humans if they are to survive. According to the IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group , some of the main threats facing amphibians are habitat loss and degradation, pollution , disease, invasive species , trade and climate change .

Frog extinction has disturbing implications for humans. The amphibians are highly susceptible to environmental disturbances, making frog populations a good indicator of the health of an environment, according to Save the Frogs. Therefore, the sheer number of amphibians at risk of extinction can be viewed as a wake-up call for the environmental damage that humans are causing to the planet.

For more information about how venomous frogs headbutt potential predators, watch this short YouTube video from the Natural History Museum in London. For tips on how to help your local frogs, check out the National Wildlife Federation website. To learn more about different frog species, check out " Frogs and Toads of the World " (Princeton University Press, 2011).

This article was originally written by Live Science contributor Alina Bradford and has since been updated.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Patrick Pester is a freelance writer and previously a staff writer at Live Science. His background is in wildlife conservation and he has worked with endangered species around the world. Patrick holds a master's degree in international journalism from Cardiff University in the U.K.

Why is a mushroom growing on a frog? Scientists don't know, but it sure looks weird

Dinosaur-era frog found fossilized with belly full of eggs and was likely killed during mating

DARPA's autonomous 'Manta Ray' drone can glide through ocean depths undetected

Most Popular

- 2 James Webb telescope confirms there is something seriously wrong with our understanding of the universe

- 3 6G speeds hit 100 Gbps in new test — 500 times faster than average 5G cellphones

- 4 2 plants randomly mated up to 1 million years ago to give rise to one of the world's most popular drinks

- 5 Quantum computing breakthrough could happen with just hundreds, not millions, of qubits using new error-correction system

- 2 6G speeds hit 100 Gbps in new test — 500 times faster than average 5G cellphones

- 3 Deepest blue hole in the world discovered, with hidden caves and tunnels believed to be inside

- 5 Hundreds of black 'spiders' spotted in mysterious 'Inca City' on Mars in new satellite photos

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

12.1: Amphibian Structure and Function

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 13238

So how did vertebrates move from the water onto land?

There had to be some major modifications. Modifications in how the animal moves, how the animal breathes, and modifications in the animals skin.

Structure and Function in Amphibians

Amphibians are vertebrates that exist in two worlds: they divide their time between freshwater and terrestrial habitats. They share a number of features with air-breathing lungfish, but they also differ from lungfish in many ways. One way they differ is their appendages. Modern amphibians include frogs, salamanders, and caecilians, as shown Figure below.

Amphibians are the first true tetrapods , or vertebrates with four limbs. Amphibians have less variation in size than fish, ranging in length from 1 centimeter (2.5 inches) to 1.5 meters (about 5 feet). They generally have moist skin without scales. Their skin contains keratin , a tough, fibrous protein found in the skin, scales, feathers, hair, and nails of tetrapod vertebrates, from amphibians to humans. Some forms of keratin are tougher than others. The form in amphibian skin is not very tough, and it allows gases and water to pass through their skin.

Amphibian Ectothermy

Amphibians are ectothermic , so their internal body temperature is generally about the same as the temperature of their environment. When it’s cold outside, their body temperature drops, and they become very sluggish. When the outside temperature rises, so does their body temperature, and they are much more active. What do you think might be some of the pros and cons of ectothermy in amphibians?

Amphibian Organ Systems

All amphibians have digestive, excretory, and reproductive systems. All three systems share a body cavity called the cloaca. Wastes enter the cloaca from the digestive and excretory systems, and gametes enter the cloaca from the reproductive system. An opening in the cloaca allows the wastes and gametes to leave the body.

Amphibians have a relatively complex circulatory system with a three-chambered heart. Their nervous system is also rather complex, allowing them to interact with each other and their environment. Amphibians have sense organs to smell and taste chemicals. Other sense organs include eyes and ears. Of all amphibians, frogs generally have the best vision and hearing. Frogs also have a larynx , or voice box, to make sounds.

Most amphibians breathe with gills as larvae and with lungs as adults. Additional oxygen is absorbed through the skin in most species. The skin is kept moist by mucus, which is secreted by mucous glands. In some species, mucous glands also produce toxins, which help protect the amphibians from predators. The golden frog shown in Figure below is an example of a toxic amphibian.

- Amphibians are ectothermic vertebrates that divide their time between freshwater and terrestrial habitats.

- Amphibians are the first true tetrapods, or vertebrates with four limbs.

- Amphibians breathe with gills as larvae and with lungs as adults. They have a three-chambered heart and relatively complex nervous system.

- What is a tetrapod?

- How does the temperature of the environment affect the level of activity of an amphibian?

- What is the cloaca? What functions does it serve in amphibians?

- Describe the different ways that amphibians may obtain oxygen.

Amphibians: The Ultimate Guide – Pictures & Facts, What Makes an Amphibian an Amphibian, Types of Amphibian – A Complete Guide To Amphibia With FREE Question Sheet

Amphibians: The Ultimate Guide. On this page you’ll find out what an amphibian is, how amphibians evolved, and the different types of amphibian alive today. On the way you’ll meet some amazing amphibians, both extinct and living.

Amphibians: The Ultimate Guide

- Introduction

What Does ‘Amphibian’ Mean?

How many species of amphibian are there, what is an amphibian.

- Breathing With The Skin

- Amphibian Characteristics

People Who Study Amphibians

- Amphibian Life Cycle

Amphibian Reproduction & Parental Care

- Types Of Amphibian

Amphibian Evolution

What do amphibians eat, amphibian defensive strategies, other amphibian pages on active wild.

- You can see examples of different amphibians on this page: List Of Amphibians With Pictures & Facts

- You'll find awesome amphibian books in our Natural History Bookstore

Discover amphibians from all around the world...

- African Amphibians

- Asian Amphibians

- Australian Amphibians

- British Amphibians

- European Amphibians

- North American Amphibians

- South American Amphibians

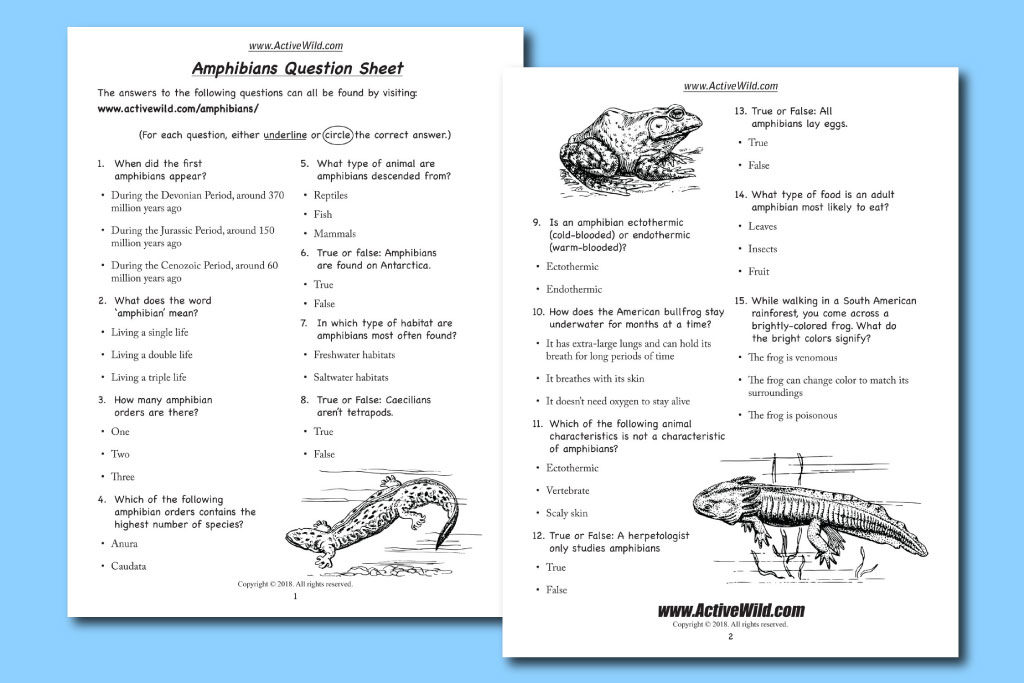

Free Printable Amphibians Question Sheet

Are you an amphibian expert? Download your FREE printable question sheet to find out! (All of the answers can be found on this page.) An answer sheet can be found here .

Amphibians: Introduction

Amphibians are animals that have adapted to living both in the water and on land. They appeared around 370 million years ago , during the Devonian Period .

Amphibians were the first vertebrates (animals with backbones) to be able to live out of water .

Amphibians lead amazing ‘ double lives ’. A typical amphibian begins life as an aquatic animal (i.e. it lives in water). Its body is equipped with gills (organs that allow it to 'breathe' underwater) and a finned tail for moving through the water.

The amphibian then undergoes a change called metamorphosis . During metamorphosis an amphibian's body changes from its larval form into its adult form. Its gills are absorbed back into its body and the amphibian develops lungs , which allow it to breathe air .

In its adult form, the amphibian is able to leave the water and live on land . It then returns to the water to breed.

The above describes a ‘typical’ amphibian. Some amphibians never leave the water, some retain their gills in adulthood, and others never grow lungs and instead ‘breathe’ through their skin!

The word ‘amphibian’ refers to the animals’ amazing double lives. It means ‘ two lives ’, or ‘both kinds of life’. The word is derived from the Greek words: amphi and bios , which mean ‘of both kinds’ and ‘life’ respectively.

The 3 Types Of Living Amphibian

- An 'order' is a group of related animals. You can find out more about orders here: Animal Classification

- You can find out more about the different types of amphibian further down the page .

All amphibians alive today are members of the subclass Lissamphibia .

There are around 6,771 species of amphibian .

There are around 5,966 species in Anura (frogs and toads), 619 species in Caudata (salamanders), and 186 species in Gymnophiona (caecilians).

An amphibian is a member of the animal class Amphibia . It is a vertebrate , which means that it has a backbone . Like all vertebrates, amphibians evolved from fish many millions of years ago.

Today, amphibians are found on every continent except Antarctica . They are freshwater animals , and very rarely found in saltwater habitats.

The crab-eating frog (Fejervarya cancrivora) of Southeast Asia is the only known amphibian able to tolerate seawater (and then only for short periods).

Four-Legged Ancestors

An amphibian is a tetrapod . As fish began to evolve into amphibians, a completely new type of animal body structure appeared. This new type of body had four limbs , and feet equipped with digits (toes / fingers).

Animals with this type of body (and animals whose ancestors had this style of body) are known as tetrapods . All amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals (including humans) are tetrapods.

You’re a tetrapod, and in the distant past your ancestors were fish. Sorry to break it to you like this!

Although they lack limbs, caecilians are tetrapods because they evolved from the same four-limbed animals as other amphibians.

Cold-Blooded Animals

Amphibians, like reptiles, are ‘ ectothermic ’, or ‘ cold-blooded ’. This means that – unlike endothermic, or warm-blooded, animals such as mammals – amphibians do not generate their own body heat .

An amphibian is unable to adjust its own body temperature, and is reliant on its environment to attain the correct body temperature.

Being ectothermic can be restricting, but it does have its advantages. Generating body heat requires a large amount of energy. Warm-blooded animals are therefore required to eat large amounts of food, and spend much of their lives foraging.

Without continuously having to look for food, ectotherms such as amphibians can spend more of their time just ‘chilling out’ (or, more precisely, warming up).

Living A ‘Double Life’ In Water & On Land

The lives of (most) amphibians are split into two separate stages: an aquatic larval stage , and a land-based adult stage .

In the aquatic stage of a typical amphibian’s life, it has gills and lives in water.

It will then go through a process called ‘ metamorphosis ’. During metamorphosis an amphibian’s body undergoes the changes that allow it to live on land.

The bodies of many adult amphibians look entirely different to their infant forms. Just think how different a tadpole is to an adult frog – it’s as if they’re two different animals rather than the same individual in different stages of its life!

Although most adult amphibians are able to live on land, they still require freshwater to reproduce. However, there are exceptions: some tropical frogs are able to reproduce without a source of water. Their young go through the tadpole stage of their development while still in the egg, and hatch in their adult form.

Several species of narrow-mouthed frog that inhabit Australia and New Guinea are examples of amphibians that hatch in their mature form.

Breathing Through The Skin

Amphibians are able to ‘breathe’ through their skin . Breathing through the skin is known as ‘ cutaneous respiration ’. Amphibian cutaneous respiration can take place both on the land and in the water. Some frogs – such as the American bullfrog – can spend the entire winter hibernating in the mud at the bottom of a pond.

Some amphibians are more reliant on cutaneous respiration than others. For example, many adult salamanders lack lungs entirely. In these species, gas exchange takes place through the skin and via tissue in the mouth and pharynx (the area behind the mouth).

A network of capillaries (very thin blood vessels) lies close to the surface of an amphibian’s skin. This allows gas to be exchanged between the amphibian’s blood and the air or water in which it lives. In order for this gas transfer to take place, an amphibian’s skin is damp and often slimy .

Although cutaneous respiration requires less energy than breathing via lungs or gills, it can only take place at a constant rate. Most amphibians have lungs to handle respiration at a greater rate when required.

An amphibian’s skin lacks scales, feathers or hair. It is thin and permeable to water.

Because an amphibian lacks the impermeable skin of an animal such as a reptile or a mammal, it is in constant danger of dehydration (drying out). Secretions from mucous glands in an amphibian’s skin help to keep it moist. An amphibian can also absorb water via its skin.

Because they have to stay moist, most amphibians are restricted to damp environments and are unable to survive in dry habitats.

Characteristics Of Amphibians

- Vertebrate (amphibians have backbones)

- Tetrapod (all amphibians – even those without legs – are descended from animals that had four legs)

- Ectothermic (amphibians do not generate their own body heat)

- Two Distinct Life Stages (the lives of most (but not all) amphibians are split into an aquatic larval stage and an air-breathing adult stage.)

- Lay Eggs in Fresh Water (most – but not all – amphibians need fresh water in which to lay their eggs.)

- Skin Breathing (an amphibian’s skin is rich with capillaries – thin blood vessels that allow gas exchange between the animal’s blood and the surrounding air or water.)

- Skin Without Scales, Feathers or Hair

- Digits Without Claws

- Usually Found In Damp Environments (amphibians can lose water through their thin, water permeable skin. To prevent drying out, they need to remain in damp environments.)

Other characteristics that separate amphibians from their fish ancestors include: a tongue , which allows food to be manipulated in the mouth; eyelids and tear ducts to protect and moisten the eyes; ears ; a sound-producing organ called the larynx ; and the Jacobson’s organ , which is situated in the nasal cavity and provides the senses of smell and taste.

Batrachology is the branch of zoology concerned with the study of amphibians.

Many people who study amphibians are also interested in reptiles. Herpetology is the branch of zoology concerned with the study of both amphibians and reptiles.

Typical Amphibian Life Cycle

Most amphibian eggs are surrounded by a clear jelly-like substance. They are laid either singly or in strands or clusters.

Most amphibians lay their eggs in body of fresh water . This can be a lake, a river or stream, a marshy area, a puddle, or even a pool of water formed inside the leaves of a plant that itself is growing in a tree.

As usual, there are exceptions. Some amphibians don't need a body of water in order to breed, instead laying their eggs underground on land. Not all amphibians lay eggs ; around three-quarters of caecilians give birth to live young , as do some frogs and salamanders.

Most amphibians go through an aquatic larval stage during which they live in water.

The larvae of salamanders resemble adults, but are smaller in size and have external gills.

Frog larvae are known as tadpoles . They are completely different in appearance to adult frogs, having tails and lacking limbs.

Although in their adult form most amphibians are able to survive away from water, they still need to remain in a damp environment in order to prevent drying out.

Several salamander species reach adulthood without going through metamorphosis . They retain their gills and are aquatic throughout their lives.

- Examples of amphibians that don’t metamorphose include the axolotl and the common mudpuppy .

Amphibians reproduce in a number of ways. Caecilians employ internal fertilization, with the male inserting a special organ into the female.

Salamanders also use internal fertilization, but in their case the male deposits sperm on the river / lake bed, which the female then takes inside of her.

Frogs employ external fertilization. This often involves the male holding onto the back of the female, and fertilizing the eggs as they are being laid.

Amphibian Parental Care

(Some) amphibians are surprisingly good parents! After laying their eggs, they will often stick around to guard their egg clutches from predators. Amphibians will also look after the eggs by keeping them aerated by fanning water over them, and removing any dead or infected eggs.

Amphibian parental care doesn’t stop once the eggs have hatched: some species of poison dart frog transport the newly hatched tadpoles to a suitable source of water by carrying them on their backs.

Types of Amphibian

As we’ve found, living amphibians can be split into three groups, or orders:

Anura (Frogs & Toads)

Caudata (salamanders & newts), gymnophiona (caecilians).

Anura – the amphibian order that includes all frogs and toads – is by far the biggest amphibian group . It contains around 6,000 species.

There is no real scientific definition between a frog and a toad; members of Anura that have drier, warty skin tend to be known as toads.

Adult frogs lack tails – in fact, the name ‘Anura’ comes from the Greek for ‘without tail’. Their well-developed hind legs and webbed hind feet assist in jumping and swimming. Many frogs live in trees, and some species lay their eggs in pools formed by the leaves of plants that themselves grow in the treetops.

Frog larvae are known as tadpoles . Newly-hatched tadpoles lack limbs and have tails. They breathe with internal gills.

As they develop, the tadpoles grow limbs and lose their tails, finally changing into miniature frogs that are able to leave the water. Whereas tadpoles are herbivorous, most adult frogs are carnivorous.

Most salamanders have long, lizard-like bodies, with two pairs of short legs.

Sirens and amphiumas are types of salamander that have lost their hind limbs and whose front legs are very small, giving them an eel-like appearance.

A salamander has a tail in both its larval and adult forms (unlike a frog). Salamander larvae usually have external gills which extend from either side of the back of the head and have a feathery appearance.

Salamanders are able to regenerate (grow back) lost limbs and other body parts!

The world’s two largest amphibians are both salamanders. They are the Chinese giant salamander and the closely-related Japanese giant salamander .

Newts are salamanders in the subfamily Pleurodelinae . Even as adults newts tend to be semi-aquatic, spending most of their lives in the water.

There are around 200 caecilian species. Most live underground , but some are aquatic. The eyes of caecilians are covered with skin, but are probably capable of discerning between lightness and darkness.

Most caecilians give birth to live young , but some species lay eggs. Caecilians are present in tropical regions in Asia, Africa and the Americas.

- You can find out more about caecilians here: Caecilian Facts

Amphibians are the earliest terrestrial (land-based) vertebrates . They appeared around 370 million years ago, during the Devonian Period.

Amphibians evolved from a group of fish called Sarcopterygii , or ‘ lobe-finned fish ’. The fins of these fish gradually evolved into limbs. The fish also evolved lungs, possibly as an adaptation for coping with dry periods.

The Sarcopterygii are the ancestors of the tetrapods – a group of four-legged animals that includes not just the amphibians, but also all reptiles, birds, and mammals (including humans).

Although most lobe-finned fish are now extinct, some, including the two marine coelacanths and the six freshwater lungfish species, survive to this day.

(As the descendants of the same species that gave rise to the tetrapods, the remaining lobe-finned fish are more closely-related to reptiles and mammals than they are to 99% of other fish.)

As the first vertebrates to adapt to life out of the water, the amphibians had a huge advantage over their water-based ancestors. With a whole new environment to expand into, and a wide range of early invertebrate prey, the early amphibians thrived.

Nearly all adult amphibians are carnivores . Most prey mainly on invertebrates, but some will also take small vertebrates such as other amphibians, fish, reptiles, and even mammals. Amphibians generally aren’t too fussy about what they eat, and will take any prey that is available and will fit in their mouths!

The larvae of most amphibians are herbivorous. However, plant matter forms a major part of the diet of only a very few adult amphibians.

Most amphibians hunt by sight, and often respond to the movement of their prey. Salamanders usually catch their prey using just their mouths, although some species also use their tongues. Most frogs capture their prey with their tongues, which can be extended and retrieved extremely quickly.

Amphibians usually swallow their prey whole.

Amphibians are important sources of food for many other animals. In order to avoid being preyed on by other predators, amphibians have evolved a number of defensive strategies.

The primary defensive mechanism of most amphibians is their moist, slimy skin, which tastes bad and is often toxic .

Many amphibians rely on their poisonous skin secretions to protect themselves from predators. The poison dart frogs of South America are among the world’s most poisonous animals. The golden poison dart frog can contain enough poison to kill up to 20 people!

Many salamanders are also highly toxic. The fire salamander is even able to spray poisonous liquid at a potential attacker.

Amphibians that are highly-toxic are often brightly-colored. This warning coloration tells any potential predators that the amphibian is poisonous and that eating it may be a bad idea!

Camouflage is also an important defensive strategy for amphibians. Many ground-dwelling species are dark brown or green in color in order to blend in with vegetation or muddy soil. Many tree frogs are bright green in color in order to blend in with the leaves of the tree canopy.

Some salamanders are able to shed their tails if attacked. The discarded tail will continue to wriggle, distracting the predator's attention and allowing the salamander to escape. The ability to discard a body part to evade predation is known as autotomy .

Amphibians: The Ultimate Guide: Related Pages

Now that you're an amphibian expert (or batrachologist), why not discover more amazing animals? Check out these awesome pages:

- Become an animal expert: Animals: The Ultimate Guide

- Become a reptile expert: Reptiles: The Ultimate Guide

- Become a bird expert: Birds: The Ultimate Guide

- Become a mammal expert: Mammals: The Ultimate Guide

- Become a bear expert: Bears: The Ultimate Guide

- Become a sea turtle expert: Sea Turtles: The Ultimate Guide

- Discover amazing animals from all around the world: A to Z Animals List With Pictures & Facts.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

SUBSCRIBE HERE

FREE Animal Fact Sheet!

Subscribe to the Active Wild newsletter for fascinating articles, news, offers, reviews and more. Sign up today and receive a FREE printable animal fact sheet with your welcome email.

Not an adult? Please ask your parent / guardian to sign up 🙂

We do not share your information, and you can unsubscribe at any time.

SUBSCRIBE TO ACTIVE WILD

Thank you for visiting Active Wild!

Stay in touch by subscribing to our newsletter!

- Improve your knowledge and appreciation of the natural world.

- Fascinating articles, plus news, special offers, reviews & more.

- FREE Animal Kingdom Fact Sheet (Arrives with your welcome email.)

- Educational Resources

- Wildlife Guide

Amphibians are a class of cold-blooded vertebrates made up of frogs, toads, salamanders, newts, and caecilians (wormlike animals with poorly developed eyes). All amphibians spend part of their lives in water and part on land, which is how they earned their name—“amphibian” comes from a Greek word meaning “double life.” These animals are born with gills, and while some outgrow them as they transform into adults, others retain them for their entire lives.

Amphibians are the most threatened class of animals in nature. They are extremely susceptible to environmental threats because of their porous eggs and semipermeable skin. Every major threat, from climate change to pollution to disease , affects amphibians and has put them at serious risk.

Frogs and Toads

Tailless amphibians with long hind limbs

Salamanders

Lizard-like amphibians with soft, moist skin

Get Involved

Donate Today

Sign a Petition

Donate Monthly

Nearby Events

Sign Up for Updates

What's Trending

UNNATURAL DISASTERS

A new storymap connects the dots between extreme weather and climate change and illustrates the harm these disasters inflict on communities and wildlife.

Come Clean for Earth

Take the Clean Earth Challenge and help make the planet a happier, healthier place.

Creating Safe Spaces

Promoting more-inclusive outdoor experiences for all

7 Reasons to Support the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act

A groundbreaking bipartisan bill aims to address the looming wildlife crisis before it's too late, while creating sorely needed jobs.

Where We Work

More than one-third of U.S. fish and wildlife species are at risk of extinction in the coming decades. We're on the ground in seven regions across the country, collaborating with 52 state and territory affiliates to reverse the crisis and ensure wildlife thrive.

- ACTION FUND

PO Box 1583, Merrifield, VA 22116-1583

800.822.9919

Join Ranger Rick

Inspire a lifelong connection with wildlife and wild places through our children's publications, products, and activities

- Terms & Disclosures

- Privacy Policy

- Community Commitment

National Wildlife Federation is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization

You are now leaving nwf.org

In 4 seconds , you'll be redirected to our Action Center at www.nwfactionfund.org.

- Search Menu

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

4 (page 72) p. 72 How amphibians move

- Published: July 2021

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

‘How amphibians move’ examines how amphibians move. The three kinds of living amphibians share the same basic biology and life history. However, the anatomy of the skeleton and muscles is very different amongst them. This reflects the different ways that the locomotion of the three respective ancestors evolved. The urodeles retained the most primitive way, with a long body and tail. Salamanders and newts use lateral undulation when swimming, but they also coupled it with limbs for walking on land. The anurans became far more modified by shortening the body, losing the tail altogether, and elongating the back legs. Meanwhile, the caecilians evolved a limbless burrowing mode.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.