Premium Content

- HISTORY MAGAZINE

China’s greatest naval explorer sailed his treasure fleets as far as East Africa

Spreading Chinese goods and prestige, Zheng He commanded seven voyages that established China as Asia's strongest naval power in the 1400s.

Perhaps it is odd that China’s greatest seafarer was raised in the mountains. The future admiral Zheng He was born around 1371 to a family of prosperous Muslims. Then known as Ma He, he spent his childhood in Mongol-controlled, landlocked Yunnan Province, located several months’ journey from the closest port. When Ma He was about 10 years old, Chinese forces invaded and overthrew the Mongols ; his father was killed, and Ma He was taken prisoner. It marked the beginning of a remarkable journey of shifting identities that this remarkable man would navigate.

Many young boys taken from the province were ritually castrated and then brought to serve in the court of Zhu Di, the future Ming emperor or Yongle. Over the next decade, Ma He would distinguish himself in the prince’s service and rise to become one of his most trusted advisers. Skilled in the arts of war, strategy, and diplomacy, the young man cut an imposing figure: Some described him as seven feet tall with a deep, booming voice. Ma He burnished his reputation as a military commander with his feats at the battle of Zhenglunba, near Beijing. After Zhu Di became the Yongle emperor in 1402, Ma He was renamed Zheng He in honor of that battle. He continued to serve alongside the emperor and became the commander of China’s most important asset: its great naval fleet, which he would command seven times.

China on the high seas

Zheng He’s voyages followed in the wake of many centuries of Chinese seamanship. Chinese ships had set sail from the ports near present-day Shanghai, crossing the East China Sea, bound for Japan. The vessels’ cargo included material goods, such as rice, tea, and bronze, as well as intellectual ones: a writing system, the art of calligraphy, Confucianism , and Buddhism.

As far back as the 11th century, multi-sailed Chinese junks boasted fixed rudders and watertight compartments—an innovation that allowed partially damaged ships to be repaired at sea. Chinese sailors were using compasses to navigate their way across the South China Sea. Setting off from the coast of eastern China with colossal cargoes, they soon ventured farther afield, crossing the Strait of Malacca while seeking to rival the Arab ships that dominated the trade routes in luxury goods across the Indian Ocean—or the Western Ocean, as the Chinese called it.

While a well-equipped navy had been built up during the early years of the Song dynasty (960- 1279), it was in the 12th century that the Chinese became a truly formidable naval power. The Song lost control of northern China in 1127, and with it, access to the Silk Road and the wealth of Persia and the Islamic world. The forced withdrawal to the south prompted a new capital to be established at Hangzhou, a port strategically situated at the mouth of the Qiantang River, and which Marco Polo described in the course of his famous adventures in the 1200s. ( See pictures from along Marco Polo's journey through Asia. )

For centuries, the Song had been embroiled in battles along inland waterways and had become indisputable masters of river navigation. Now, they applied their experience to building up a naval fleet. Alas, the Song’s newfound naval mastery was not enough to withstand the invasion of the mighty Mongol emperor Kublai Khan. ( Kublai Khan achieved what Genghis could not: conquering China .)

Kublai Khan kamikazed

Kublai Khan built an empire for the Mongols in the 13th century, conquering China in 1279. He also had his sights set on Japan and tried to invade, not once, but twice: first in 1274 and again in 1281. Chroniclers of the time report that he sent thousands of Chinese and Korean ships and as many as 140,000 men to seize the islands of Japan. Twice his massive forces sailed across the Korea Strait, and twice his fleet was turned away; legend says that two kamikazes, massive typhoons whose name means “divine wind,” were summoned by the Japanese emperor to sink the invading vessels. Historians believed the stories to be legendary, but recent archaeological finds support the story of giant storms saving Japan.

The Mongols and the Ming

Having toppled the Song and ascended to the Chinese imperial throne in 1279, Kublai built up a truly fearsome naval force. Millions of trees were planted and new shipyards created. Soon, Kublai commanded a force numbering thousands of ships, which he deployed to attack Japan, Vietnam, and Java. And while these naval offensives failed to gain territory, China did win control over the sea-lanes from Japan to Southeast Asia. The Mongols gave a new preeminence to merchants, and maritime trade flourished as never before.

On land, however, they failed to establish a settled form of government and win the allegiance of the peoples they had conquered. In 1368, after decades of internal rebellion throughout China, the Mongol dynasty fell and was replaced by the Ming (meaning “bright”) dynasty. Its first emperor, Hongwu, was as determined as the Mongol and Song emperors before him to maintain China as a naval power. However, the new emperor limited overseas contact to naval ambassadors who were charged with securing tribute from an increasingly long list of China’s vassal states, among them, Brunei, Cambodia, Korea, Vietnam, and the Philippines, thus ensuring that lucrative profits did not fall into private hands. Hongwu also decreed that no oceangoing vessels could have more than three masts, a dictate punishable by death. ( The Ming Dynasty built the Great Wall. Find out if it worked. )

Yongle was the third Ming emperor, and he took this restrictive maritime policy even further, banning private trade while pushing hard for Chinese control of the southern seas and the Indian Ocean. The beginning of his reign saw the conquest of Vietnam and the foundation of Malacca as a new sultanate controlling the entry point to the Indian Ocean, a supremely strategic location for China to control. In order to dominate the trade routes that united China with Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean, the emperor decided to assemble an impressive fleet, whose huge treasure ships could have as many masts as necessary. The man he chose as its commander was Zheng He.

Epic voyages

Although he is often described as an explorer, Zheng He did not set out primarily on voyages of discovery. During the Song dynasty, the Chinese had already reached as far as India, the Persian Gulf, and Africa. Rather, his voyages were designed as a display of Chinese might, as well as a way of rekindling trade with vassal states and guaranteeing the flow of vital provisions, including medicines, pepper, sulfur, tin, and horses.

The fleets that Zheng He commanded on his seven great expeditions between 1405 and 1433 were suitably ostentatious. On the first voyage, the fleet numbered 255 ships, 62 of which were vast treasure ships, or baochuan. There were also mid-size ships such as the machuan, used for transporting horses, and a multitude of other vessels carrying soldiers, sailors, and assorted personnel. Some 600 officials made the voyage, among them doctors, astrologers, and cartographers.

The ships left Nanjing (Nanking), Hangzhou, and other major ports, from there veering south to Fujian, where they swelled their crews with expert sailors. They then made a show of force by anchoring in Quy Nhon, Vietnam , which China had recently conquered. None of the seven expeditions headed north; most made their way to Java and Sumatra, resting for a spell in Malacca, where they waited for the winter monsoon winds that blow toward the west.

You May Also Like

She was Genghis Khan’s wife—and made the Mongol Empire possible

Meet 5 of history's most elite fighting forces

Kublai Khan did what Genghis could not—conquer China

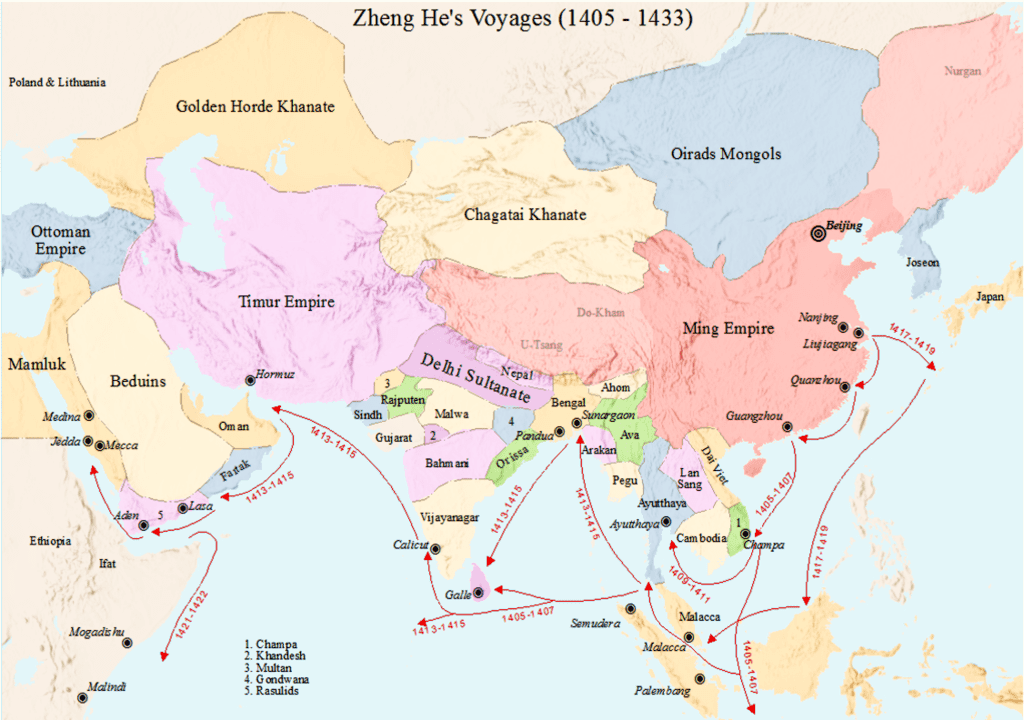

They then proceeded to Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka) and Calicut in southern India, where the first three expeditions terminated. The fourth expedition reached Hormuz in the Persian Gulf, and the final voyages expanded westward, entering the waters of the Red Sea, then turning and sailing as far as Kenya, and perhaps farther still. A caption on a copy of the Fra Mauro map —the original, now lost, was completed in Venice in 1459, more than 25 years after Zheng He’s final voyage—implies that Chinese ships rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1420 before being forced to turn back for lack of wind.

Treasure ships were the largest vessels in Zheng He’s fleet. A description of them appears in adventure novel by Luo Maodeng, The Three-Treasure Eunuch’s Travels to the Western Ocean (1597). The author writes that the ships had nine masts and measured 460 feet long and 180 feet wide. It is hard to believe that the ships would have been quite so vast. Authorities on Zheng He’s maritime expeditions believe the vessels more likely had five or six masts and measured 250 to 300 feet long.

Chinese ships had always been noted for their size. More than a century before Zheng He, explorer Marco Polo described their awesome dimensions: Between four and six masts, a crew of up to 300 sailors, 60 cabins, and a deck for the merchants. Chinese vessels with five masts are shown on the 14th-century “Catalan Atlas” from the island of Mallorca. Still, claims in a 1597 adventure tale that Zheng He’s treasure ships reached 460 feet long do sound exaggerated. Most marine archaeological finds suggest that Chinese ships of the 14th and 15th centuries usually were not longer than 100 feet. Even so, a recent discovery by archaeologists of a 36-foot-long rudder raises the possibility that some ships may have been as large as claimed. (A 1,200-year-old shipwreck reveals how the world traded with China.)

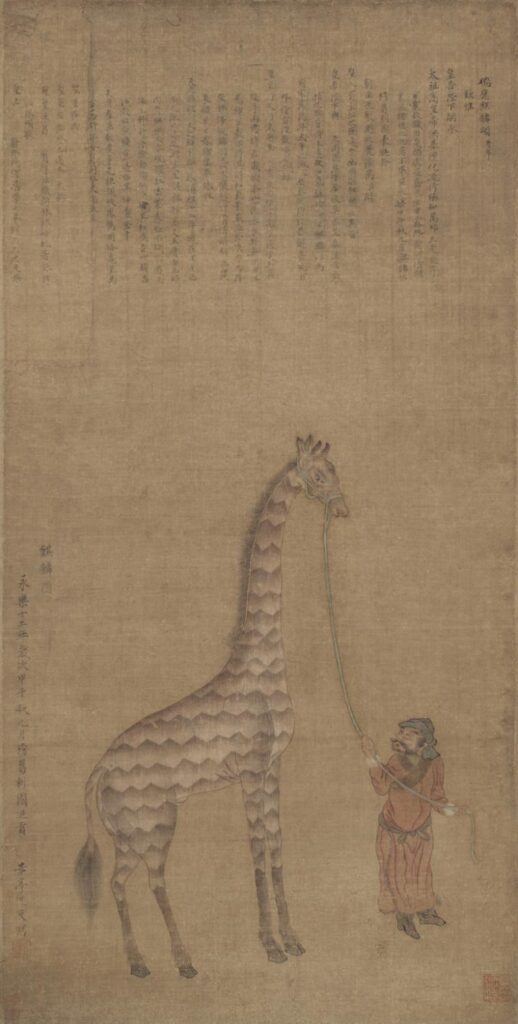

Ma Huan's true tall tales

Of the three chroniclers who recorded Zheng He’s voyages, Ma Huan was perhaps the most reliable. Of humble origins, Ma Huan converted to Islam as a young man and studied Arabic and Persian. At age 23 he served as an interpreter for the fourth expedition. He served on the sixth and seventh voyages as well. In East Africa Ma Huan first saw what he called a qilin —the Chinese word for a unicorn-like creature—evidently a giraffe: ”The head is carried on a long neck over 16 feet long,” he noted, with some exaggeration. “On its head it has two fleshy horns. It has the tail of an ox and the body of a deer...and it eats unhusked rice, beans and flour cakes.”

End of an odyssey

Zheng He’s voyages ended abruptly in 1433 on the command of Emperor Xuande. Historians have long speculated as to why the Ming would have abandoned the naval power that China had nurtured since the Song. The problems were certainly not economic: China was collecting enormous tax revenues, and the voyages likely cost a fraction of that income.

The problem, it seems, was political. The Ming victory over the Mongols caused the empire’s focus to shift from the ports of the south to deal with tensions in the north. The voyages were also viewed with suspicion by the very powerful bureaucratic class, who worried about the influence of the military. This fear had reared its head before: In 1424, between the sixth and seventh voyages, the expedition program was briefly suspended, and Zheng He was temporarily appointed defender of the co-capital Nanjing, where he oversaw construction of the famous Bao’en Pagoda, built with porcelain bricks.

The great admiral died either during, or shortly after, the seventh and last of the historic expeditions, and with the great mariner’s death his fleet was largely dismantled. China’s naval power would recede until the 21st century. With the nation’s current resurgence, it is no surprise that the figure of Zheng He stands once again at the center of China’s maritime ambitions. Today the country’s highly disputed “nine-dash line”— which China claims demarcates its control of the South China Sea—almost exactly maps the route taken six centuries ago by Zheng He and his remarkable fleet.

Related Topics

- IMPERIAL CHINA

The Great Wall of China's long legacy

Why Lunar New Year prompts the world’s largest annual migration

Was Manhattan really sold to the Dutch for just $24?

Go inside China's Forbidden City—domain of the emperor and his court for nearly 500 years

These 5 secret societies changed the world—from behind closed doors

- Environment

- Perpetual Planet

- History & Culture

History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

The Ages of Exploration

Age of discovery.

Quick Facts:

Chinese explorer who commanded several treasure fleets – Chinese ships that explored and traded across Asia and Africa. His expeditions greatly expanded China’s trade.

Name : Zheng He [jung] [ha]

Birth/Death : 1371 - 1433

Nationality : Chinese

Birthplace : China

Zheng He Statue

General Zheng He - statue in Sam Po Kong temple, Semarang, Indonesia. (Credit: en.wiki 22Kartika)

Introduction Zheng He was a Chinese explorer who lead seven great voyages on behalf of the Chinese emperor. These voyages traveled through the South China Sea, Indian Ocean, Arabian Sea, Red Sea, and along the east coast of Africa. His seven total voyages were diplomatic, military, and trading ventures, and lasted from 1405 – 1433. However, most historians agree their main purpose was to promote the glory of Ming dynasty China. 1

Biography Early Life Zheng He was born to a noble family in 1371 in the Yunnan Province of China. His father was named Haji Ma, and his mother’s maiden name was “Wen”. Ma He had one older brother, and four sisters. 2 His family was Muslim, so when he was born, he was originally named “Ma He.” Ma is the Chinese version of Mohammed, who was the great prophet of the Islamic faith. 3 His father and grandfather were highly respected in their community. Young Ma He was educated as a child, often reading books from great scholars such as Confucius and Mencius. 4 Ma He was curious about the world from a young age. In Islam, Muslim believers are supposed to make a pilgrimage, called a hajj in Arabic, to the Muslim holy city of Mecca (in present day Saudi Arabia). Ma He’s father and grandfather had both made this hajj, so Ma He often them questions of their journey, along with the people and places they encountered. In 1381, when Ma He was about 11 years old, Yunnan was attacked and conquered by soldiers from the Ming army, who were under the rule of Emperor Hong Wu. Ma He, like many children, were taken captive and brought to serve as a eunuch in the Ming Court.

While serving in the royal court, the Emperor had noticed that Ma He was a hardworking boy. Ma He received military training, and soon became a trusted assistant and adviser to the emperor. He also served as a bodyguard protecting the prince Zhu Di during many battles against the Mongols. Shortly after, Zhu Di became emperor of the Ming Dynasty. Having served in the court for many years, Ma He was eventually promoted to Grand Eunuch.This was the highest rank a eunuch could be promoted to. Because of his new and higher position, the Emperor gave Ma He the new name “Zheng” He. 5 With his new title came additional duties Zheng He would be responsible for. He would be in charge of palace construction and repairs, learned more about weapons, and became more knowledgeable in ship construction. 6 His understanding of ships would become very important to his future. In 1403, Zhu Di, ordered the construction of the Treasure Fleet – a fleet of trading ships, warships and support vessels. This fleet was to travel across the South China Sea and Indian Ocean areas. The Emperor chose Zheng He to command this fleet. He would be the official ambassador of the imperial court to foreign countries. This would begin Zheng He’s maritime career, and some of the most impressive exploration journeys in history.

Voyages Principal Voyage Zheng He’s first voyage (1405-1407) began in July 1405. They set sail from Liujiagan Port in Taicang of Jiangsu Province and headed westward. The fleet had about 208 vessels total, including 62 Treasure Ships, and more than 27,800 crewman. 7 They traveled to present day Vietnam. Here, they met with the king and presented him with gifts. The King was pleased with Zheng He and the emperor’s kind gesture, and the visit was a friendly one. After leaving, the fleet traveled to Java, Sumatra; Malacca (the Spice Islands); crossed the Indian Ocean and sailed west to Cochin and Calicut, India. The many stops included trading of spices and other goods, plus visiting royal courts and building relations on behalf of the Chinese emperor. He also saw several new animals, which he told the emperor about upon his return. Zheng He’s first voyage ended when he returned to China in 1407.

Zheng He’s second (1408-1409) and third (1409-1411) voyages followed a similar route to his first. Once again he stopped in places like Java, Sumatra; and visited ports on the coast of Siam (today called Thailand) and the Malay Peninsula. 8 Zheng He’s fourth voyage (1413-1415) would be his most impressive yet. The Chinese Emperor really wanted to display the wealth and power China had to offer. With 63 large ships, and a crew of over 27,000 men, Zheng He set sail. Once more he sailed to the Malay Peninsula, to Sri Lanka, and on to Calicut in India. Instead of staying at Calicut as he had on previous voyages, Zheng He and his fleet also sailed to the Maldive and Laccadive Islands to the Hormuz on the Persian Gulf. 9 Along the way, they traded goods like silk and spices with rulers of other countries. He returned to Nanjing in 1415. He also brought back with him several envoys or representatives of various countries for the emperor to meet with and learn from.

Subsequent Voyages By 1417, the Yongle Emperor ordered Zheng He to return the envoys home. Once more back on the seas, Zheng He and his large fleet set sail for his fifth expedition (1417-1419). He stopped in many of the same places, including Java, Sumatra, and also brought letters and riches to the different rulers Zheng He met. On this trip, Zheng He sailed into new waters, to the Somali coast and down to Kenya, both in Africa. He returned back to China in 1419. Zheng He’s sixth voyage (1421-1422) was his shortest of them all. He was authorized to return the remaining envoy’s to their home countries. Not only did he revist many of the ports he’d been to many times, but also went back to the Mogadishu region of Somalia. He also visited Thailand, before making his way back to China in September 1422. By the time he returned, the emperor had died. The new emperor suspended all expeditions. Zheng He remained in the royal court working for the new emperor, helping with the construction of a large temple. But would be almost another 10 years before Zheng He went on his seventh and final voyage.

Later Years and Death It was not until 1431 that Zheng He found himself in command of the large Treasure Fleet for his seventh voyage (1431-1433). They sailed to Java, Sumatra and several other Asian ports before arriving in Calicut, India. During this trip, Zheng He temporarily split from the fleet and made his hajj to the Muslim holy city of Mecca. 10 At some point, Zheng He fell ill, and died in 1433. It is not known whether or not he made it back to China, or died on his final great voyage.

Legacy Zheng He’s voyages to western oceans expanded China’s political influence in the world. He was able to expand new, friendly ties with other nations, while developing relations between the east-west trade opportunities. Unfortunately, the official imperial records of his voyages were destroyed. The exact purpose of his voyages, the routes taken, and the size of his fleets are heavily debated because of their unique nature. 11 Nonetheless, his leadership and principles have remained known over the centuries in Chinese history. July 11 is celebrated as China’s National Maritime Day commemorating his first voyage.

- Leo Suryadinata, ed., Admiral Zheng He & Southeast China (Pasir Panjang, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2005), 44.

- Hum Sin Hoon, Zheng He’s Art of Collaboration: Understanding the Legendary Chinese Admiral from a Management Perspective (Pasir Panjang, Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, 2012), 6.

- Hoon, Zheng He’s Art of Collaboration, 6.

- Hoon, Zheng He’s Art of Collaboration, 7.

- Information Office of the People’s Government of Fujian Province, Zheng He’s Voyages Down the Western Seas (China: China Intercontinental Press, 2005), 8.

- Shih-shan Henry Tsai, The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 157.

- Information Office of the People’s Government of Fujian Province, Zheng He’s Voyages Down the Western Seas, 22.

- Brian Fagan, Beyond the Blue Horizon: How the Earliest Mariners Unlocked the Secrets of the Oceans (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2012), 157.

- Fagan, Beyond the Blue Horizon, 158.

- Fagan, Beyond the Blue Horizon, 162.

- Richard E. Bohlander, ed., World Explorers and Discoverers (New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1992), 466.

Bibliography

Bohlander, Richard E., ed. World Explorers and Discoverers. New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1992.

Fagan, Brian. Beyond the Blue Horizon: How the Earliest Mariners Unlocked the Secrets of the Oceans. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2012.

Hoon, Hum Sin. Zheng He’s Art of Collaboration: Understanding the Legendary Chinese Admiral from a Management Perspective. Pasir Panjang, Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, 2012.

Information Office of the People’s Government of Fujian Province, Zheng He’s Voyages Down the Western Seas. China: China Intercontinental Press, 2005.

Suryadinata, Leo ed. Admiral Zheng He & Southeast China. Pasir Panjang, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2005.

Tsai, Shih-shan Henry. The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996.

- Original "EXPLORATION through the AGES" site

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

This site uses cookies to improve user experience. By continuing to browse, you accept the use of cookies and other technologies.

The Ming Treasure Voyages Projected Chinese Wealth and Influence in the 15th Century

These sea voyages had lofty goals.

- Photo Credit: Wikipedia

Beginning in 1403, China’s Yongle Emperor issued a decree that prompted the construction of a massive new fleet. Historians are unsure just how many new ships were constructed as part of this immense undertaking, and how many were repurposed from existing vessels—the Yongle Emperor had already inherited a powerful maritime fleet when he usurped the Ming throne at the end of the Jingnan rebellion.

What we know about this growing “treasure fleet” is how it was used. Under the command of Admiral Zheng He, the fleet engaged in seven major “treasure voyages” that traveled all over the South China Sea, throughout the Indian Ocean, and beyond. Expeditions reached as far as the Persian Gulf and East Africa. While the voyages were named for the massive treasure ships, which carried riches showcasing China’s wealth and prestige, they were also heavily militarized, and their voyages, while not overtly combative, helped to establish Chinese control over an extensive maritime network that was one of the largest in the world at that time.

Explore China's Rich History with These Books

As with the size of the fleet itself, the precise goals of these treasure voyages are a matter of some debate among historians. The official name of the treasure fleet, which roughly translates to “foreign expeditionary armada,” gives some clue of its intended function. It's clear that these voyages were of substantial importance to the Yongle Emperor, who gave Zheng He blank scrolls stamped with the imperial seal, so that he could issue orders at sea with all the strength of the emperor behind them.

The result was the establishment of a Chinese hegemony across maritime trade throughout much of the region, with numerous nations declaring themselves tributaries of the empire and sending foreign ambassadors to the emperor’s court, which led to a massive growth in cultural exports, as well as wealth and goods.

Though modern Chinese celebrations of the Ming Treasure Voyages portray them as primarily peaceful enterprises, they succeeded in establishing China’s naval dominance over the entire region, extending throughout the Indian Ocean—a feat never before accomplished by any single nation. They did this not by seizing territory but by exerting political and economic inducements to the countries that the treasure fleets visited.

Dust off exclusive book deals and tales from the past when you join The Archive 's newsletter.

The fleets were not above using military force, however, and in the course of their seven voyages they also destroyed the pirate fleet of Chen Zuyi at the Battle of Palembang in 1407, and fought a brief war with the Sinhalese Kotte kingdom in southern Sri Lanka, which ultimately resulted in the overthrow of King Alakeshvara. Primarily, however, the function of the treasure voyages seems to have been what Robert Finlay described in the Journal of the Historical Society as “a deployment of state power to bring into line the reality of seaborne commerce with an expansive conception of Chinese hegemony.”

That is to say, the Ming Treasure Voyages expanded Chinese power and influence not, primarily, through conquest or even political maneuvering, but by impressing those countries visited with China’s wealth and power, so that their geographic neighbors would voluntarily enter into a tributary relationship with the empire.

A Brief History of Opium

Because the treasure fleets neither sought exclusive trade nor attempted to impose Chinese rule, they were often welcomed by the nations they visited. Furthermore, the treasure ships themselves, which were the largest vessels in the fleet, acted as “an emporium offering a wealth of products,” according to Finlay, which allowed access to commodities and valuables that many of the people at their destinations had never had the opportunity to trade for in the past. And because the presence of the treasure fleets made potential trade routes more stable, they were often welcomed by other traders.

In fact, these voyages were so successful as drivers of trade that the booming Ming economy began trading and exporting commodities that were not originally Chinese in origin. Nor did the trade flow only one way. The expeditions brought back numerous goods to China that frequently had transformative effects upon the local economy and industry. Black pepper, once a costly rarity, became commonplace, while cobalt oxide imported from Persia helped to define the porcelain industry that became synonymous with the Ming dynasty.

Portrait of the Yongle Emperor, who sponsored the Ming Treasure Voyages.

As these voyages solidified a Chinese hegemony throughout the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean, other results began to manifest, as well. Along with commodities, cultural exports began to spread throughout the trade avenues opened by the Ming Treasure Voyages, while the Chinese control of the waterways led to the development of cosmopolitan spaces where representatives from numerous different countries mingled.

These flourishing trade partnerships and budding cultural exchanges continued long after the last of the treasure voyages ended in 1433, but an era had certainly drawn to a close when the treasure fleet returned to port from its seventh voyage. The precise reason for their cessation remains a mystery, with historians pointing to various possible causes, from cost to political infighting to a growth of private, rather than state-run, commerce.

The Taiping Rebellion and Hong Xiuquan, Self-Proclaimed Younger Brother of Jesus

Whatever the ultimate reasons for the cessation of the treasure voyages, their legacy would live on both within mainland China and well beyond. Today, China celebrates the Ming Treasure Voyages on National Maritime Day, which takes place every year on July 11. The voyages also loom large in modern Chinese political narratives, which posit them as blueprints for a growing China to continue to establish itself as a maritime and trading power in the contemporary global marketplace.

Nor is China the only place where the voyages left their mark. Throughout the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean, the visits of the treasure fleets changed the nations where they stopped, introducing new trade goods and new ideas, and bringing together representatives from disparate countries, opening up a climate of trade that other nations would continue to build upon. When Portuguese explorer Vasco de Gama arrived on the shores of East Africa more than half a century later, his men were even mistaken for Chinese, as the Chinese were the last strangers that the people of the East African coast remembered arriving in large wooden ships.

Sources: Weatherhead East Asia Institute of Columbia University

Get historic book deals and news delivered to your inbox

© 2024 OPEN ROAD MEDIA

- We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

- Corrections

Admiral Zheng He: China’s Forgotten Master of the High Seas

Zheng He was a Chinese admiral who made seven epic voyages between 1405 and 1433. Under his command, the grand fleet included the largest wooden ships of all time.

Eighty years before Vasco da Gama reached India and kickstarted the Age of Exploration, another great seafarer, admiral Zheng He, commanded a grand navy to spread the influence and prestige of Ming China. Under his leadership, the Chinese fleet embarked on seven voyages to establish and facilitate peaceful diplomatic and trade relationships with foreign countries, sailing from Southeast Asia to India, and from the Persian Gulf to East Africa. The so-called “Treasure Fleet” was a sight to behold, numbering over 300 vessels.

Besides the giant “treasure ships,” over 120 meters long, the armada consisted of many supply vessels, warships, water tankers, and patrol boats, carrying over 28,000 men. The Treasure Fleet fulfilled its mission, increasing the prestige of China and its emperor overseas, but it failed to take the next logical step. Following Zheng He’s death, the voyages abruptly ceased. The fleet was dismantled, and China closed its borders to the world, leaving supremacy over the high seas to the emerging European colonial powers.

Zheng He, an Unlikely Admiral

Considering Zheng He’s background, it is odd that he became one of the greatest admirals and seafarers in the history of China and the world. Born in 1371 CE to a prominent Muslim family, Zheng He, initially known as Ma He, spent his childhood in the landlocked Yunnan province controlled by the last remnants of the Mongol Yuan dynasty .

The future admiral would probably never have seen the sea if fate did not intervene. When he was ten years old, Chinese forces invaded the region and overthrew the Mongols. His father perished in the fighting, and Ma He was taken as a prisoner. A disaster to some, for Ma He, this was an opportunity, the beginning of a truly remarkable journey that would take him far from home and far from China to places that existed only in a young boy’s imagination.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

After a ritual castration (a common practice at the time) Ma He entered the Ming court as a eunuch. Here he caught the eye of Zhu Di, one of the emperor’s sons, who took him into his service. Over the next decade, Ma He would distinguish himself and rise to become one of the young prince’s most trusted advisers. When Zhu Di rebelled against his late father’s successor, Ma He joined the cause, leading the prince’s forces at the battle of Zhenglunba (near Beijing).

Skilled in the art of war and strategy , he defeated the imperial troops and claimed the throne for his friend. Zhu Di did not forget this, and after becoming “the Yongle Emperor” in 1402, Ma He was renamed Zheng He in honor of this battle. He also became the second most powerful man in China, the emperor’s trusted confidante, and an ideal choice for the grand plan to bring the Empire back to the world’s stage.

A Match Made in Heaven

Zhu Di’s father founded and consolidated the Ming dynasty, fighting brutal battles against the Mongols. Now, after both external and internal circumstances had stabilized, the Yongle emperor could begin preparations for his grand plan: to demonstrate Ming power to the world and to revive the golden eras of the Han and Tang dynasties . Instead of using force, the new emperor wanted to increase China’s influence and prestige through soft power and diplomacy. This ambitious plan required an intelligent and capable leader who could be the emperor’s trustworthy ambassador in far-flung lands. Unsurprisingly, the choice was simple — Zhu Di’s close friend and associate, Zheng He.

The plan involved using a large navy, which would sail to distant lands to “convince” foreign rulers to recognize China as their superior and its emperor as lord of “all under Heaven”. In return for gifts of tribute, China would establish and maintain trade and diplomatic connections. By that time, China was already a naval power. Both the Song and Yuan dynasties had kept large navies and controlled the South China Sea. Under Kublai Khan, the Mongols had built a fearsome naval force consisting of thousands of ships and deployed it during the failed invasion of Japan . Thus, the Ming inherited a formidable navy. But the emperor’s plan was more ambitious. The existing ships would serve as the core for a more impressive and massive grand fleet commanded by Zheng He.

The Largest Fleet the World Has Ever Seen

To realize his grand plan, the emperor put all the resources of his vast Empire at Zheng He’s disposal. All the shipyards along China’s coast had one job — to build a great fleet. Under Zheng’s oversight, workers cut down trees, processed lumber, and created new shipyards to fulfill this mammoth task.

Scores of new vessels were built, but the highlight of the fleet was undoubtedly the famed “treasure ships” or baochuan . These vessels were giants in every sense of the word, 122-meter-long (over five times the size of Columbus’ caravels), hosting nine huge masts, a crew of up to 300 sailors, 60 cabins, and four decks filled with soldiers, merchants, diplomats, doctors, cartographers, and other officials. Historians still debate their exact size, but a recent discovery of an 11-meter-long rudder suggests that the ships may have been as large as claimed.

Besides their mind-boggling size, the ships also used an innovative design. The “treasure ships” and the support vessels — five-masted warships, six-masted troop transports, and six-to-seven-masted transports carrying grain, horses, and water — featured divided hulls with several watertight compartments. Advanced engineering allowed Zheng He to take unprecedented amounts of drinking water on long voyages while also adding much-needed ballast, balance, and stability, essential for smooth sailing over the open seas.

The Treasure Fleet was designed to “show the flag,” to both impress and cow regional rulers. For this reason, the vessels were elaborately decorated, the rigging decorated with yellow flags, sails dyed red with henna, hulls painted with huge elaborate birds, and large eyes painted on the bow. One could only imagine the impression Zheng He’s 300-vessel-armada would leave upon arriving in a foreign port. Indeed, the very sight of the majestic fleet fulfilled its primary aim, to display the glory and might of Ming China and its emperor.

It was also gunboat diplomacy at its finest. Although the Treasure Fleet’s chief purpose was diplomacy, Zheng He’s enormous ships were heavily armed, their huge decks brimming with cannons, one of the greatest Chinese inventions .

The Voyages

The first of seven voyages began in July 1405. Zheng He’s fleet comprised around 255 vessels, 62 of them being enormous “treasure ships” and carrying nearly 28, 000 men. Their first stop was Vietnam, recently conquered by the Ming. After resting in Malacca, waiting for the winter monsoon to sail west across the Indian Ocean, the fleet visited Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka) and Calicut on the southwestern coast of India.

The Malabar coast, the center of Indian Ocean trade , was also the terminus of the first three expeditions. The fourth expedition reached Hormuz in the Persian Gulf, while the later voyages advanced further west, entering the Red Sea and sailing to the East African coast. Scholars are still debating if the Treasure Flee rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1420 before turning back due to the lack of wind.

At every stop, Zheng He would establish diplomatic and trade relations with the locals, visit royal courts and collect tribute, including spices, frankincense, ivory, precious gems, and even exotic animals. Most famously, the fourth expedition brought back to China a giraffe, described by a contemporary as qilin — a unicorn-like creature whose head rested on a long neck, over five meters long (evidently an exaggeration). The fourth voyage was also the most impressive, consisting of around 300 ships.

Besides the various goods and animals, the fleet brought to China numerous envoys and representatives of various countries for the audience with the emperor. It was also an effective way for Zhu Di to show Ming China’s power and influence without spending vast sums of money and manpower on costly military campaigns. Zheng He, however, did not shrink from violence when he considered it necessary. He ruthlessly suppressed pirates who had long plagued Chinese and Southeast Asian waters and waged mini-wars with the local rulers unwilling to cooperate.

The Last Voyage

After decades of travel and trade, the cost of keeping the floating metropolis was becoming too prohibitive, even for the ambitious Yongle emperor. His influential courtiers’ complaints about these expensive far-flung cruises were compounded by the renewed Mongol threat on the northern border, forcing the emperor to move the capital from Beijing. Constructing and supplying giant ships became a significant burden to the imperial finances. For this reason, Zheng He’s sixth expedition mainly focused on returning foreign envoys to their homelands.

Then, in 1424, Zhu Di died, and the new emperor who replaced him had different priorities. Zheng He lost his position. His main opponents were more conservative Confucian courtiers, and they now had the emperor’s ear. China was gradually shifting its focus inward to the Mongols and the construction and expansion of the Great Wall .

New military expenditures directly competed with the funds required to continue naval expeditions. Zheng He, however, continued to cooperate with the new emperor, playing a role in the completion of a majestic pagoda and surrounding temple, destroyed centuries later during the Taiping rebellion . He performed his task admirably, as in 1431, and the emperor approved the seventh voyage.

Zheng He’s Legacy

Zheng He’s seventh voyage was to be his last. The 62-year-old admiral died on the return journey in 1433. He was buried at sea, and the fleet turned back to China. Soon after, the emperor, supported by Confucian officials , ordered the ships to be burned and outlawed most maritime trade. In what was a purely political move, all official records of the voyages were systematically destroyed. During the following decades, any suggestion of returning to the high seas was firmly rejected, while China closed its doors to the world.

Despite the attempts of his opponents to erase Zheng He and the Treasure Fleet from history, his legacy remained. For instance, Malacca on the Malayan peninsula, which played an essential role in supplying the grand fleet, became a great port and the hub of a trade network that extended across Southeast Asia up to China.

Furthermore, Zheng He’s voyages had a lasting impact on Asia, setting up migration routes and cultural exchanges that reshaped China and the region . After the Empire abandoned virtually all maritime trade, coastal communities took over, with many residents turning to smuggling and piracy. Further, many of Zheng He’s sailors never returned to China, building their homes and storehouses in ports in Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam. Chinese communities have remained in those regions until the present day.

Zheng He and his seven expeditions brought China to the brink of becoming the main power on the high seas. Then, in a cruel twist of fate, the admiral died, and the Ming emperors reversed their policy a few decades before Europe’s explorers embarked on their own voyages, ushering the old continent into the Age of Exploration and colonialism. When China finally emerged from its long isolation, it encountered a much different world, where the ruler of “all under Heaven” was inferior and foreign fleets ruled the high seas.

The Seven Voyages of Zheng He: When China Ruled the Seas

By Vedran Bileta MA in Late Antique, Byzantine, and Early Modern History, BA in History Vedran is a doctoral researcher, based in Budapest. His main interest is Ancient History, in particular the Late Roman period. When not spending time with the military elites of the Late Roman West, he is sharing his passion for history with those willing to listen. In his free time, Vedran is wargaming and discussing Star Trek.

Frequently Read Together

Qin Shi Huangdi: The Man Who Gave His Name to China

The Mongol Empire Versus China: The Way of War

Sun Tzu: The Man Who Defined Chinese Warfare

- The Journal of Military History

Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405-1433 (review)

- David Andrew Graff

- Society for Military History

- Volume 71, Number 1, January 2007

- pp. 213-214

- 10.1353/jmh.2007.0029

- View Citation

Additional Information

Project MUSE Mission

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

When China ruled the oceans: the Ming treasure voyages

Between the fifteenth and eighteenth century, European explorers and colonizers sailed the oceans, expanding from their continent to the entire world during the so-called Age of Discovery. However, decades before the Spanish ships crossed the Atlantic Ocean to reach the Americas, the Chinese Empire, ruled by the Ming dynasty, saw its own age of exploration. From 1405 to 1433, seven maritime expeditions known as the “treasure voyages” sailed around the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean, reaching Southeast Asia, India, the Arabian Peninsula, and Africa. These voyages were carried out by huge fleets, with very large and heavily-armed ships that carried treasures and riches, projecting the diplomatic and military power of the Ming Empire throughout the region, bringing many countries into the Chinese sphere of influence, sometimes by force. The history of the Ming treasure voyages is closely related to the internal affairs of China and the life of the admiral who led the expeditions: Zheng He, a Muslim eunuch and former slave.

Zheng He and the Yongle Emperor

Zheng He was born as Ma He in 1371 from a Muslim family living in the modern-day province of Yunnan, China. At the time, Yunnan was ruled by loyalists of the fallen Mongol Yuan dynasty, which was deposed by the Ming in 1368. Zheng He himself was a descendant of a Mongol governor of Yunnan named Ajall Shams al-Din Omar. The Ming forces attacked the Yuan remnants in Yunnan in 1381, and Zheng He was captured and later castrated, becoming a eunuch servant of Zhu Di, Prince of Yan. Zhu Di was at the time the ruler of Beijing, near the northern frontier, and often launched military campaigns against the Mongols. Zheng He took part in the expeditions as a soldier and, over the years, became a trusted confidant of the prince, and received a formal education.

Due to his growing power, Zhu Di was considered as a rival by the ruling Jianwen Emperor, who ordered his arrest in 1399. The Prince of Yan responded by leading a rebellion against the imperial court, which evolved into a three-year-long civil war known as the Jingnan campaign. Througout the war, Zheng He assisted his master as one of his military commanders and, after the successful rebellion, Zhu Di was crowned as the Yongle Emperor in 1402. The new emperor promoted his favorite eunuch, still called Ma He, to Grand Director of the Directorate of Palace Servants, and gave him the new surname Zheng in 1404, a reference to his victory against the enemy forces at Zhenglunba, the city reservoir of Beijing, during the Jingnan campaign five years earlier.

Statue of Zheng He in Nanjing, China (left) ( Vmenkov, Wikimedia Commons , CC BY-SA 3.0 ) and a portrait of the Yongle Emperor (right).

Projecting power: the first three treasure voyages

The Yongle Emperor wanted to expand the power of China and one of his primary objectives was to establish imperial control over the Indian Ocean trade, while also extending the tributary system of the Empire. He ordered the construction of a huge fleet, which included warships as well as trading and support ships, and placed Zheng He in command. However, according to the historical text History of Ming , the heavily-armed first expedition might have instead been ordered just to find the Jianwen Emperor, the deposed predecessor of the Yongle Emperor, who was believed to have fled to Southeast Asia.

Whatever the reason behind it, the first voyage departed from the imperial capital Nanjing on July 11, 1405, after offering sacrifices and prayers to Tianfei, the tutelary deity of seafarers, to which Zheng He was devoted in his unique syncretism between Islam and Chinese folk religion. The first expedition brought gifts and imperial letters in its 62 treasure ships, while 255 vessels took part in the voyage. It is not clear if these 255 are all the ships or just the support vessels, the second case would raise the total number of ships taking part in the voyage to 317. The ships were crewed by almost 28,000 men.

The fleet reached Champa, in modern-day Vietnam, and continued south in 1406 to Malacca and then Java, before returning to the north and crossing the Strait of Malacca. The expedition visited northern Sumatra and the Andaman Islands, and then sailed the Indian Ocean to Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, where the local king Alakeshvara was unfriendly to the fleet. After departing Ceylon, the voyage reached its final destination of Calicut, on the southwestern coast of India. The fleet may have stayed for a few months in Calicut before their return trip in 1407, during which Zheng He defeated the pirates led by Chen Zuyi who were occupying Palembang, on the island of Sumatra. After the capture and execution of Chen Zuyi, the Ming sent trusted civil servant Shi Jinqing to rule Palembang, gaining access to a strategic port on the Strait of Malacca. The expedition returned to Nanjing on October 2, 1407, and immediately a second voyage was ordered by the Yongle Emperor, departing in late 1407 or early 1408 with 249 ships.

The second voyage followed a similar path as the first one, stopping in Champa, Siam, Java, Malacca, and Sumatra, but the expedition avoided Ceylon before reaching Calicut. There, the Ming established a friendly relationship with the local king, while there was some tension between China and the Majapahit Empire of Java after the Javanese killed some members of a Chinese embassy. The dispute was settled when Majapahit apologized and sent gold to the Ming as compensation, restoring diplomatic relations.

The second expedition returned to Nanjing in the summer of 1409, but a third one had already been ordered a few months earlier, so Zheng He again departed with his fleet that October. After following the usual route, the Ming expedition landed in Ceylon either in 1410 or 1411, and deposed with military force the ruler of the local Kingdom of Kotte, Alakeshvara, who opposed the Chinese presence years earlier. The Ming fleet, counting over 27,000 men, defeated the larger Sinhalese army of 50,000 troops, and put their ally Parakramabahu VI on the throne of Kotte. The third voyage ended in July 1411, with the fleet returning to Nanjing.

Model of a treasure ship in the National Museum of China in Beijing ( Gary Todd, Wikimedia Commons , CC0 1.0 ).

China dominates the Indian Ocean trade

The fourth expedition departed from Nanjing in the autumn of 1413, with interpreters and translators in order to facilitate trade with the Muslim countries. The fleet followed the familiar route to Calicut before sailing beyond India to reach the Maldives and Lakshadweep Islands, and then Hormuz, in modern-day Iran. After trading with the locals, the expedition stopped in Sumatra during their return trip. There, the Ming troops attacked and deposed Sekandar, usurper of the rightful ruler of the Samudera Pasai Sultanate. After once again affirming the Chinese influence in the Strait of Malacca, the fleet returned to Nanjing in August 1415.

During the time of the fourth expedition, the Yongle Emperor was fighting the Mongols on the northern border, and only returned to the capital in late 1416. Upon its return, a great ceremony was held and the emperor received the ambassadors of eighteen countries, each one bringing gifts to him. The Yongle Emperor immediately announced a fifth voyage to escort home the ambassadors and send gifts to their countries.

The fifth voyage went even further than the fourth one. Departing in the autumn of 1417, the fleet again reached Hormuz before continuing to Aden, on the Arabian Peninsula, Mogadishu and Barawa, now both in Somalia, and finally arriving in Malindi, in modern-day Kenya. The stop at Aden in 1419 is well documented in local records, and describes splendid and rich “dragon ships”, filled with treasures. The sultan of the Rasulid dynasty, that ruled Yemen at the time, sent back gifts and tributes and submitted to the Ming in exchange with protection against the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt. When the fleet returned to China in August 1419, it brought many exotic animals such as lions and cheetas from Yemen, giraffes from Somalia, and also camels, zebras, rhinoceroses, ostriches, antelopes, and leopards.

In 1421 an order was issued for the sixth voyage which, similarly to the previous one, was aimed at returning the foreign ambassadors home with more gifts, mostly silk products. Departing in November 1421, this expedition arrived in Ceylon and then split into smaller groups, with each reaching different destinations they previously visited in India, the Maldives, Hormuz, various Arabian states, and the Eastern African coast. After getting the whole fleet back together, the expedition stopped in Siam before returning to China in September 1422.

Depiction of a giraffe gifted by Bengali envoys to the Yongle Emperor.

The last treasure voyage

The voyages were temporarily halted after the sixth one, as funding was diverted to the ongoing campaigns against the Mongols in the North. In 1424, Zheng He sailed to Palembang on a short diplomatic mission, but when he came back he found out that the Yongle Emperor had died and was succeeded by his son, the Hongxi Emperor. The new emperor opposed the treasure voyages and officially cancelled any plan for future expeditions. Zheng He was nominated Defender of Nanjing and kept his fleet, but only as part of the capital’s garrison. However, the Hongxi Emperor died in May 1425 and was succeeded by his son, the Xuande Emperor. Under the new ruler Zheng He initially kept his position in the capital, even supervising the restoration of the Great Bao’en Temple in the city, and was then ordered to lead a seventh voyage to the Indian Ocean in 1430.

The seventh, and last, treasure voyage departed from Nanjing on January 19, 1431, with the goal of demanding tributes and submission from foreign countries. After following the coast of China, the fleet reached Vietnam, before continuing towards Surabaya, Palembang, and Malacca. The expedition stopped in Semudera, in northern Sumatra, where the fleet was divided in two. While the main group crossed the ocean to reach Ceylon and Calicut, a smaller squadron visited Chittagong, Sonargaon, and Gaur in Bengal, before reuniting with the other ships in Calicut.

The itinerary of the expedition is not clear after Calicut, some sources report only a visit to Hormuz, while others suggest that at least some of the ships may have sailed to East Africa and the Arabian coast, even reaching Mecca. Nevertheless, the fleet returned to China in September 1433. Sources are conflicting also on the death of Zheng He, that might have occurred either during the seventh voyage or shortly afterwards, in 1435. This marked the end of the Ming treasure voyages. Why exactly no more expeditions were ever ordered is not clear, but it might have been caused by bureaucrats, traders, and other powerful individuals that wanted to protect their own economic interests in China, opposing a total control of the government over foreign trade.

Map of the voyages of the treasure fleet of Zheng He ( SY, Wikimedia Commons , CC BY-SA 4.0 ).

The decline of the Ming Empire

After the treasure voyages, the Ming Empire, the most powerful naval power in Asia, gradually declined as the tributary system broke down and the government lost his maritime monopoly. The Indian Ocean and South China Sea trade flourished for some time even after the voyages stopped, but then the Ming started turning from foreign to local commerce, leaving the seas. In the following decades, the voyages were described by civil officials as wasteful, costly, exaggerated, and even contrary to Confucian principles. The absence of the Chinese influence in the Indian Ocean left a power vacuum in the region for decades, until the European explorers started taking control of the trade in the area at the end of the fifteenth century. However, the memory of the Ming treasure voyages remained in the regions they visited for much longer.

It is interesting to wonder what could have happened if the Ming expeditions continued and traveled further. Maybe Chinese fleets could have crossed the Cape of Good Hope into the Atlantic Ocean. Maybe they could have reached and even colonized Australia centuries before the Europeans. What if they decided to sail east across the Pacific Ocean, setting foot on the western coast of America? Could there have been a war between the Ming Empire and the Western powers for control over the Indian Ocean, or even global, trade? We will never know, but this possibility remains one of the most fascinating what-ifs in world history.

Why Did Ming China Stop Sending out the Treasure Fleet?

Gwydion M. Williams/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

- Figures & Events

- Southeast Asia

- Middle East

- Central Asia

- Asian Wars and Battles

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- Ph.D., History, Boston University

- J.D., University of Washington School of Law

- B.A., History, Western Washington University

Between 1405 and 1433, Ming China sent out seven gigantic naval expeditions under the command of Zheng He the great eunuch admiral. These expeditions traveled along the Indian Ocean trade routes as far as Arabia and the coast of East Africa, but in 1433, the government suddenly called them off.

What Prompted the End of the Treasure Fleet?

In part, the sense of surprise and even bewilderment that the Ming government's decision elicits in western observers arises from a misunderstanding about the original purpose of Zheng He's voyages. Less than a century later, in 1497, the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama traveled to some of the same places from the west; he also called in at the ports of East Africa, and then headed to India , the reverse of the Chinese itinerary. Da Gama went in search of adventure and trade, so many westerners assume that the same motives inspired Zheng He's trips.

However, the Ming admiral and his treasure fleet were not engaged in a voyage of exploration, for one simple reason: the Chinese already knew about the ports and countries around the Indian Ocean. Indeed, both Zheng He's father and grandfather used the honorific hajji , an indication that they had performed their ritual pilgrimage to Mecca, on the Arabian Peninsula. Zheng He was not sailing off into the unknown.

Likewise, the Ming admiral was not sailing out in search of trade. For one thing, in the fifteenth century, all the world coveted Chinese silks and porcelain; China had no need to seek out customers — China's customers came to them. For another, in the Confucian world order, merchants were considered to be among the lowliest members of society. Confucius saw merchants and other middlemen as parasites, profiting on the work of the farmers and artisans who actually produced trade goods. An imperial fleet would not sully itself with such a lowly matter as trade.

If not trade or new horizons, then, what was Zheng He seeking? The seven voyages of the Treasure Fleet were meant to display Chinese might to all the kingdoms and trade ports of the Indian Ocean world and to bring back exotic toys and novelties for the emperor. In other words, Zheng He's enormous junks were intended to shock and awe other Asian principalities into offering tribute to the Ming.

So then, why did the Ming halt these voyages in 1433, and either burn the great fleet in its moorings or allow it to rot (depending upon the source)?

Ming Reasoning

There were three principal reasons for this decision. First, the Yongle Emperor who sponsored Zheng He's first six voyages died in 1424. His son, the Hongxi Emperor, was much more conservative and Confucianist in his thought, so he ordered the voyages stopped. (There was one last voyage under Yongle's grandson, Xuande, in 1430-33.)

In addition to political motivation, the new emperor had financial motivation. The treasure fleet voyages cost Ming China enormous amounts of money; since they were not trade excursions, the government recovered little of the cost. The Hongxi Emperor inherited a treasury that was much emptier than it might have been, if not for his father's Indian Ocean adventures. China was self-sufficient; it didn't need anything from the Indian Ocean world, so why send out these huge fleets?

Finally, during the reigns of the Hongxi and Xuande Emperors, Ming China faced a growing threat to its land borders in the west. The Mongols and other Central Asian peoples made increasingly bold raids on western China, forcing the Ming rulers to concentrate their attention and their resources on securing the country's inland borders.

For all of these reasons, Ming China stopped sending out the magnificent Treasure Fleet. However, it is still tempting to muse on the "what if" questions. What if the Chinese had continued to patrol the Indian Ocean? What if Vasco da Gama's four little Portuguese caravels had run into a stupendous fleet of more than 250 Chinese junks of various sizes, but all of them larger than the Portuguese flagship? How would world history have been different, if Ming China had ruled the waves in 1497-98?

- The Seven Voyages of the Treasure Fleet

- Biography of Zheng He, Chinese Admiral

- Timeline: Zheng He and the Treasure Fleet

- Biography of Explorer Cheng Ho

- Zheng He's Treasure Ships

- Biography of Zhu Di, China's Yongle Emperor

- Emperors of the Ming Dynasty

- Indian Ocean Trade Routes

- How Did Portugal Get Macau?

- A Brief History of the Age of Exploration

- Was Sinbad the Sailor Real?

- Origins of the Trans-Atlantic Trade of Enslaved People

- Kilwa Kisiwani: Medieval Trade Center on Africa's Swahili Coast

- Comparative Colonization in Asia

- The First and Second Opium Wars

- Country Profile: Malaysia Facts and History

- Children's Books

- Geography & Cultures

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the authors

Seven Voyages: How China's Treasure Fleet Conquered the Sea Hardcover – January 19, 2021

From New York Times bestselling author Laurence Bergreen and author Sara Fray comes this immaculately researched history for young readers detailing the life of Zheng He, his complex and enduring friendship with his emperor, and the epic Seven Voyages he led that would establish China as a global power. 1405. The central coast of China. At nearly seven feet tall, Admiral Zheng He looked out at the sea before him. For the next three decades, the oceans would be his home, as he would command over 1,500 ships and thousands of sailors in seven journeys that would predate the heart of the European Age of Exploration. Over his seven epic journeys, Zheng He explored the Northern Pacific and Indian Oceans, traveling as far as the east coast of Africa, expanding Chinese power globally, warring with pirates, and capturing enemies along the way in the name of his emperor, Zhu Di. But this giant figure was not always at the helm of a ship.

- Reading age 10 - 14 years

- Print length 176 pages

- Language English

- Grade level 4 - 6

- Dimensions 6.27 x 0.79 x 9.34 inches

- Publisher Roaring Brook Press

- Publication date January 19, 2021

- ISBN-10 162672122X

- ISBN-13 978-1626721227

- See all details

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Editorial Reviews

From school library journal, about the author, product details.

- Publisher : Roaring Brook Press (January 19, 2021)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 176 pages

- ISBN-10 : 162672122X

- ISBN-13 : 978-1626721227

- Reading age : 10 - 14 years

- Grade level : 4 - 6

- Item Weight : 12.9 ounces

- Dimensions : 6.27 x 0.79 x 9.34 inches

- #164 in Children's Exploration Books

- #232 in Children's Boats & Ships Books (Books)

- #377 in Children's Asia Books

About the authors

Laurence bergreen.

Laurence Bergreen is the author of four biographies, each considered the definitive work on its subject: Louis Armstrong: An Extravagant Life, Capone: The Man and the Era, As Thousands Cheer: The Life of Irving Berlin, and Voyage to Mars: NASA's Search for Life Beyond Earth. A graduate of Harvard University, he lives in New York City.

Sara Fray is an American author. Her Middle Grade nonfiction Seven Voyages was a 2021 Junior Library Guild Gold Standard Selection and received a Booklist starred review. Her Young Adult adaptation of Bergreen’s Magellan was a Junior Library Guild Selection in the fall of 2017. A lifelong bibliophile and graduate of Columbia University, she was an A&R executive before she became a historical researcher and contributing editor of a New York Times Editors’ Choice. Sara lives in New York with her husband, daughter and Great Danes and is a member of The Authors Guild and SCBWI. To connect with Sara Fray, visit https://sarafray.com

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

New Evidence Ancient Chinese Explorers Landed in America Excites Experts

- Read Later

By Tara MacIsaac , Epoch Times

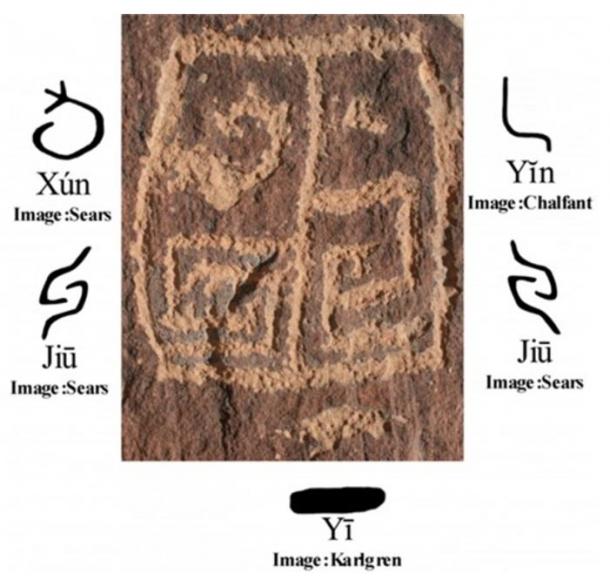

John A. Ruskamp Jr., Ed.D., reports that he has identified an outstanding, history-changing treasure hidden in plain sight. High above a walking path in Albuquerque’s Petroglyph National Monument, Ruskamp spotted petroglyphs that struck him as unusual. After consulting with experts on Native American rock writing and ancient Chinese scripts to corroborate his analysis, he has concluded that the readable message preserved by these petroglyphs was likely inscribed by a group of Chinese explorers thousands of years ago.

On the fringe of archaeology have long been claims that the Chinese reached North America long before Europeans. With some renowned experts taking interest in Ruskamp’s discovery, those claims may be working their way from the fringe to the core.

It doesn’t mean our history textbooks will change tomorrow. Anything short of discovering an undisturbed early Asiatic relic or village in the Americas may fail to convince those archaeologists who have dogmatically rejected evidence of an ancient Chinese presence in the New World, said Ruskamp.

But, the disparate and widespread symbols he has found show many indications of authenticity. They have the potential to inspire a more serious investigation into early trans-Pacific interaction. To date, Ruskamp has identified over 82 petroglyphs matching unique ancient Chinese scripts not only at multiple sites in Albuquerque, New Mexico, but also nearby in Arizona, as well as in Utah, Nevada, California, Oklahoma, and Ontario. Collectively, he believes that most of these artifacts were created by an early Chinese exploratory expedition, although some appear to be reproductions made by Native people for their own purposes.

- Did China discover America 70 years before Columbus?

- Ancient Bronze Artifacts in Alaska Reveals Trade with Asia Before Columbus Arrival

- Sea-Farers from the Levant the first to set foot in the Americas: proto-Sinaitic inscriptions found along the coast of Uruguay

One of Ruskamp’s staunchest supporters has been David N. Keightley, Ph.D., a MacArthur Foundation Genius Award recipient who is considered by many to be the leading analyst in America of early Chinese oracle-bone writings. Keightley has helped Ruskamp decipher the scripts he has identified. One ancient message, preserved by three Arizona cartouche petroglyphs, translates as: “Set apart (for) 10 years together; declaring (to) return, (the) journey completed, (to the) house of the Sun; (the) journey completed together.” At the end of this text is an unidentified character that may be the author’s signature.

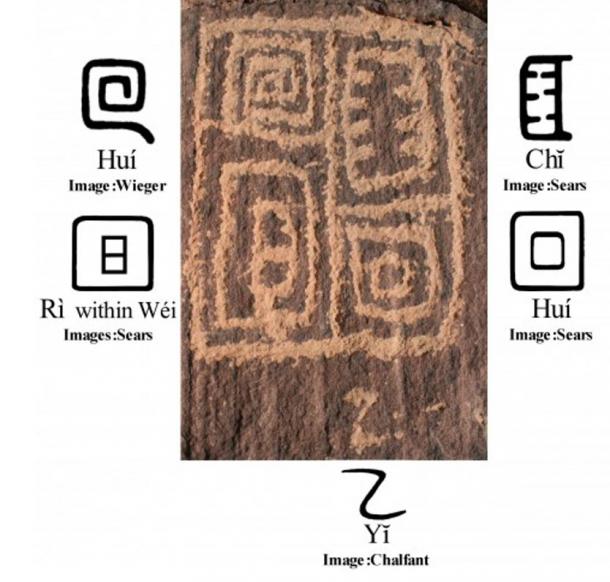

Cartouche 1, which reads “Set apart (for) 10 years together.”(Courtesy of John Ruskamp)

Cartouche 2, which reads, “Declaring (to) return, (the) journey completed, (to the) house of the Sun.” (Courtesy of John Ruskamp)

Cartouche 3, which reads, “(The) journey completed together.” (Courtesy of John Ruskamp)

The Arizona glyph site on what has always been, and still is, very private ranch property located miles from any public access or road. (Courtesy of John Ruskamp)

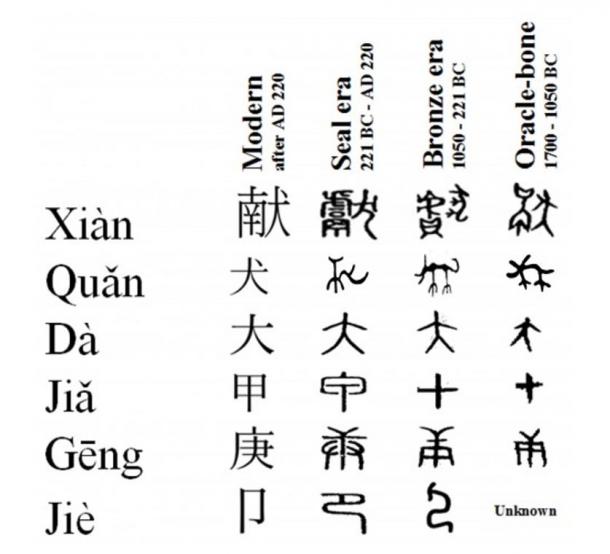

The oracle-bone style of writing employed for creating a number of these ancient petroglyph scripts disappeared by royal decree from mankind’s memory around 1046 B.C., following the fall of the Shang Dynasty. It remained an unknown and totally forgotten form of writing until it was rediscovered in A.D. 1899 at Anyang, China. Ruskamp thus concluded that the mixed styles of Chinese scripts found in these Arizona petroglyphs indicates that they were made during a transitional period of writing in China, not long after 1046 B.C.

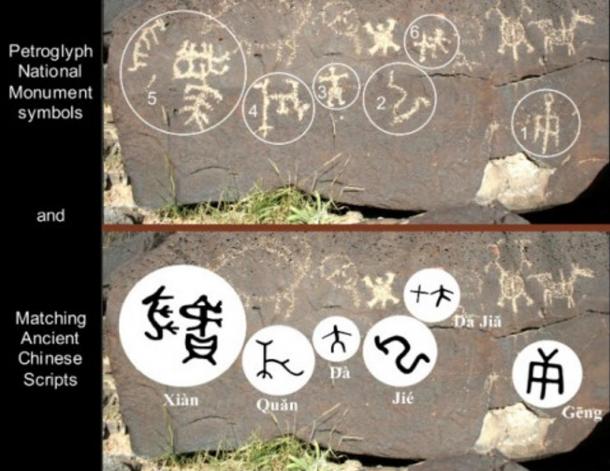

Ruskamp gives the following translation for the Albuquerque petroglyphs: “Gēng (a date; the seventh Chinese Heavenly Stem); Jié (to kneel down in reverence); Da (great—referring to a superior); Quăn (dog—the sacrificial animal); Xiàn (offering worship to deceased ancestors); and Dà Jiă (the name of the third king of the Shang dynasty).”

Albuquerque petroglyphs (Courtesy of John Ruskamp)

The Albuquerque petroglyphs use both Seal era and Bronze era Chinese scripts, suggesting they were also written during a transitional period in Chinese calligraphy, likely between 1046 B.C. and 475 B.C. The use of the title “Da” before the name “Jiă,” suggests a date close to the end of the Shang Dynasty in 1046 B.C., as this appellation emerged during that time period and was replaced shortly thereafter.

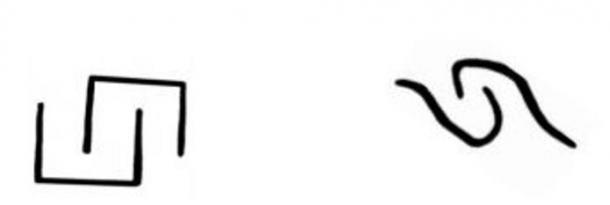

A comparison of scripts over time. (Courtesy of John Ruskamp)

Michael F. Medrano, Ph.D., chief of the Division of Resource Management for Petroglyph National Monument, studied the petroglyphs at that location upon Ruskamp’s request. He said that, based on his more than 25 years of experience with local Native cultures, “These images do not readily appear to be associated with local tribal entities,” and “based on repatination appear to have antiquity to them.”

It is difficult to physically date petroglyphs with absolute certainty, notes Ruskamp. Yet the syntax and mix of Chinese scripts found at these two locations correspond to what experts would expect explorers from China to use some 2,500 years ago.

For example, the Arizona ranch petroglyphs are divided into three sections each enclosed in a square known as a cartouche. Two of the cartouches are numbered; one with the Chinese script for “one” placed beneath it and in a similar manner the second cartouche has the ancient Chinese script meaning “second” inscribed beneath it. Together these numeric figures indicate the order in which these images should be read. Importantly, the cartouches are thus shown to be read in the traditional Chinese manner, from right to left.

The first two cartouches are rotated 90 degrees to the left of vertical and the third is rotated 90 degrees to the right. “The deliberate rotation of these writings, both to the left and right of vertical by an equal number of degrees, endorses their authenticity, for the rotation of individual scripts by Chinese calligraphers is well-documented,” wrote Ruskamp.

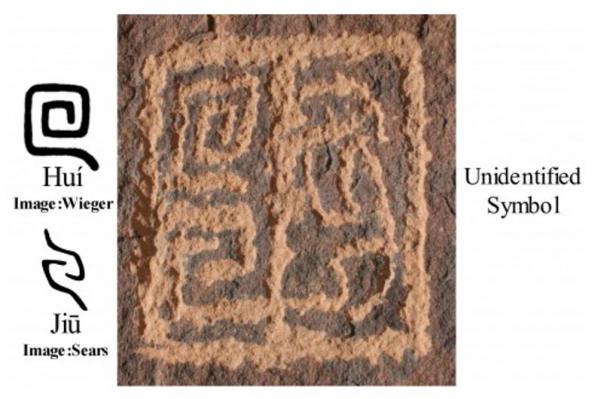

Some of the symbols found in the petroglyphs are common to both Chinese script and ancient Native American writing. For instance, “The Chinese petroglyph figure of Jiu conveys the idea of “togetherness,” in much the same manner as the Nakwach symbol is now, and has been in the past, understood by the Hopi,” wrote Ruskamp.

Left: Hopi Nakwách symbol. Right: Chinese petroglyph figure of Jiu. (Sears; Courtesy of John Ruskamp)

Another similarity is the use of a rectilinear spiral to convey the concept of a “round-trip journey.”

A rectilinear spiral similarly used by the Chinese and the Hopi to convey the concept of a “round-trip journey.”(Wieger; Courtesy of John Ruskamp)

Though these similarities could be conceived as supporting a Native American origin for Ruskamp’s petroglyphs, Ruskamp stated: “The extensive Chinese vocabulary evidenced at each location advocates against the authorship of the figures evaluated in this study being credited to Native Americans. None of the more complex Chinese figures identified in this report are known to have any Native tribal affiliation.”

The conclusion of his paper titled “Ancient Chinese Rock Writings Confirm Early Trans-Pacific Interaction,” reads: “In contrast to any previous historical uncertainty, the comparative evidence presented in this report, which is supported by both analytical evaluation and expert opinion, documenting the presence of readable sequences of old Chinese scripts located upon the rocks of North America, establishes that prior to the extinction of oracle-bone script from human memory, approximately 2,500 years ago, trans-Pacific exchanges of epigraphic intellectual property took place between Chinese and North American populations.”

He published the paper on his website, Asiaticechoes.org, in April and it is currently under peer review. Last October, he began presenting his findings in speaking engagements, including most recently to the Association of American Geographers in Chicago. He will next present at a meeting of the Little Colorado River Chapter of the Arizona Archaeology Society in Springerville, Arizona, on May 18. The editors of the journal Pre-Columbiana have confirmed they will soon publish Ruskamp’s article. The journal is edited by Professor Emeritus Stephen C. Jett, Ph.D., University of California–Davis, with the assistance of an editorial board of distinguished professional scholars, and is dedicated to exploring Pre-Columbian transoceanic contact.

A retired educator, statistician, and analytical chemist, Ruskamp pursued his study of petroglyphs as a hobby—little expecting to find what may lead to a great shift in how we view both American and Chinese history.

Featured image: Arizona cartouche petroglyphs. (Courtesy of John Ruskamp)

The article ‘ New Evidence Ancient Chinese Explorers Landed in America Excites Experts ’ was originally published on The Epoch Times and has been republished with permission.

It is known that Kwan Ying, Goddess of Mercy was an actual princess-queen. She held the West Coast region of Central America as a Chinese-Japanese ruler of an extended colony of Asia here ... in the times of Jesus. Such Chinese and Japanese migrations and colonies along the West Coast would be nothing new. Even Japanese colonists continue in the Peru area ... and up into modern times.

Having any number of inland colonies up and down the West Coast, using ancient Chinese writing would be considered natural. Colonies expand and explore the interior of islands and continents. And in ancient times, such frontier locations could have easily moved from the West Coast of Central America) into AZ and NM, having their rock inscriptions.

It is also readily known that many of the modern branches of Amerindians were actual refugees from the Spanish conquest of Central America in 1492 and later. Miwoks (San Francisco), Mohawks (northeast), Mohicans, Michigan, Mihouicans were all Mayans. Cherokee, Chirichuahua, Iriquois, Crow, Cree were from the city-state of Quiragua Mexico. Apache and so many others are modern migrations from Central America. All these came from the South and moved north along ancient trails as old as 400s and earlier. They didn't need to walk up the Pacific shoreline first, and then go inland.

In the times of King David, 1000s BC, his other concubine sons ... other than Bathsheba's sons Solomon and Nathan ... were moved from the Mideast into the America's West Coast line. Many of the noted West Coast Indian tribal names come from these sons. Nogah (Inca), Aleut, Inuit, Hopi, Navaho, and many more. Albeit they are considered Israelites, their mothers could be any racial ancestry. It is now more correctly known that "Bath Sheba" princess-queen daughter of Xbalba was Mayan Mihouican. So Israelite King David and Mexican wife had their bi-racial sons Solomon and Nathan, who stayed in the Mideast. So there is no problem for these concubine sons having pan-Asian ancestry, and they would provide the Asian appearance to these Pacific Northwest Indian tribes. And with Solomon having all of the international princesses, queens, and other high royal and noble females procreating a planetary dynasty of children for those regions - the Solomonic Fleet traversing the Indian and Pacific Oceans 1000s BC could have translocated and bred up any number of future royal dynasties on site - but also be moved into other areas for residency.