Facts about groundhogs

Groundhogs, also called woodchucks, are large rodents. Traditionally, their shadows are used to predict when winter will end.

- Classification/taxonomy

- Conservation status

- Shadow facts

How much wood?

Additional resources.

Groundhogs ( Marmota monax ), also called woodchucks, are large rodents. They are also one of the 14 species of marmot, or ground squirrels. In fact, they are the largest members of the squirrel family. Most people probably know the groundhog as a weather prognosticator because of Groundhog Day. However, those predictions are typically not very good.

Groundhog size

From head to rump, groundhogs are 17.75 to 24 inches (45 to 61 centimeters) long, according to National Geographic . They weigh around 13 pounds (6 kilograms), which is about twice the average weight of a newborn human baby. Like other squirrels, groundhogs have long tails that grow around 7 to 9.75 in (18 to 25 cm) long.

These round creatures look like little bears when they stand up on their hind legs. Groundhogs also have sharp claws that they use to dig impressive burrows in the ground. During the warm months, a groundhog's incisors continue to grow each week to keep up with their frenzied eating schedule, according to the National Wildlife Federation. If they aren't worn down enough by chewing that can be fatal to the overgrown squirrels, according to the NWF .

Groundhog habitat

Groundhogs are found only in North America, from Canada down to the southern United States, according to AnimalDiversity.org . They like woodland areas that bump up against more open areas. They dig burrows that can be 6 feet (1.8 meters) deep, and 20 feet (6 m) wide. These underground homes can also have two to a dozen entrances, according to the National Wildlife Federation . Typically, they have a burrow in the woods for the winter and a burrow in grassy areas for the warmer months. Groundhogs keep their burrows tidy by changing out the nesting found inside from time to time.

Groundhog habits

Groundhogs are solitary creatures, and they spend their summers and falls stuffing themselves and taking naps in the sun.

In the winter, they hibernate. While hibernating, the groundhog's heartbeat slows from 80 beats per minute to 5 beat per minute; their respiration reduces from 16 breaths per minute to as few as 2 breaths per minute; and their body temperature drops from about 99 degrees Fahrenheit (37.2 degrees Celsius) to as low as 37 F (2.77 C), according to the National Wildlife Federation.

A groundhog typically sticks close to home. They usually don't wander farther than 50 to 150 feet (15 to 30 m) from their den during the daytime, according to the Internet Center for Wildlife Damage Management .

Groundhog diet

These rodents are herbivores, which means they eat vegetation. A groundhog's diet can include fruit, plants, tree bark and grasses. They are known for damaging crops and gardens and many consider them pests.

Groundhogs don't eat during hibernation. They use fat that they built up over the summer and winter month.

Groundhog offspring

In February, males will come out of hibernation and search for females' burrows. When he finds one, he heads on in. It is believed that males do this to introduce themselves to possible mates. In the spring, mating season progresses and the females give birth to two to six young after a gestation period of around 32 days.

The babies are blind and hairless, but quickly become mature in just three months or so. When they are mature, they typically leave their mother to dig their own homes. Groundhogs in the wild live around three to six years, according to PBS.org .

Groundhog classification/taxonomy

Here is the classification for groundhogs, according to the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS):

Kingdom : Animalia

Subkingdom : Bilateria

Infrakingdom : Deuterostomia

Phylum : Chordata

Subphylum : Vertebrata

Infraphylum : Gnathostomata

Superclass : Tetrapoda

Class : Mammalia

Subclass : Theria

Infraclass : Eutheria

Order : Rodentia

Suborder : Sciuromorpha

Family : Sciuridae

Subfamily : Xerinae

Tribe : Marmotini

Genus : Marmota

Subgenus : Marmota

Species : Marmota monax

Subspecies:

- Marmota monax bunkeri

- Marmota monax canadensis

- Marmota monax ignava

- Marmota monax johnsoni

- Marmota monax monax

- Marmota monax ochracea

- Marmota monax petrensis

- Marmota monax preblorum

- Marmota monax rufescens

Groundhog conservation status

Groundhogs are listed as least concern for extinction on the International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List of Threatened Species. They are widespread from central Alaska, across Canada and south through the United States to Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana and Arkansas.

Groundhog shadow facts

According to tradition, if the groundhog sees its shadow on Feb. 2, there will be six more weeks of winter. This idea gave rise to Groundhog Day. The tradition of relying on rodents as forecasters may date back to the early days of Christianity in Europe, when clear skies on Candlemas Day (Feb. 2) were said to herald cold weather ahead, according to the Old Farmer's Almanac . In Germany, the tradition morphed into a myth that if the sun came out on Candlemas, a hedgehog would cast its shadow, predicting snow all the way into May. When German immigrants settled in Pennsylvania, they transferred the tradition onto local fauna, replacing hedgehogs with groundhogs.

But how accurate is this method of weather prediction? The Punxsutawney Groundhog Club, of Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, has records from more than 100 years. On Groundhog Day, the club holds a "solemn" ceremony as a groundhog, named Phil, is pulled from a "burrow" in front of TV cameras and cheering crowds. The club says Phil has predicted 99 forecasts of more winter and 15 early springs. According to data from the Stormfax Almanac, Phil's predictions have been correct only 39% of the time in his hometown of Punxsutawney.

How much wood would a woodchuck chuck, if a woodchuck could chuck wood? About 700 pounds (317 kg), according to Cornell University.

Actually, the name woodchuck has nothing to do with wood, or chucking it, according to Animal Diversity Web . The word woodchuck comes from a Native American word, wuchak , which roughly translates as "digger." (Another name for this animal is whistle-pig, according to the National Museum of Natural History .)

Nevertheless, according to Cornell, a wildlife biologist sought to answer the tongue-twister's question. He measured the volume a woodchuck burrow and estimated that if the hole were filled with wood rather than dirt, the woodchuck would have chucked about 700 pounds (Woodchucks, however, typically do not chew wood.)

- The Official Site for Groundhogs Day

- Cornell: Groundhog Day Facts and Factoids

- The Humane Society of the United States: What to Do About Woodchucks

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Giant coyote killed in southern Michigan turns out to be a gray wolf — despite the species vanishing from region 100 years ago

A war of the rats was raging in North America decades before the Declaration of Independence

Low tides reveal Bronze Age fortress that likely defended against Irish mainland

Most Popular

By Anna Gora December 27, 2023

By Anna Gora December 26, 2023

By Anna Gora December 25, 2023

By Emily Cooke December 23, 2023

By Victoria Atkinson December 22, 2023

By Anna Gora December 16, 2023

By Anna Gora December 15, 2023

By Anna Gora November 09, 2023

By Donavyn Coffey November 06, 2023

By Anna Gora October 31, 2023

By Anna Gora October 26, 2023

- 2 James Webb telescope confirms there is something seriously wrong with our understanding of the universe

- 3 Cholesterol-gobbling gut bacteria could protect against heart disease

- 4 April 8 solar eclipse: What time does totality start in every state?

- 5 2024 solar eclipse map: Where to see the eclipse on April 8

- 4 2024 solar eclipse map: Where to see the eclipse on April 8

- 5 Decomposing globster washes ashore in Malaysia, drawing crowds

Secrets of the Groundhog Revealed

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/mb-head-8efe594c4cb4485b8a5605a4fe1d015d.jpg)

- Hunter College

- F.I.T., State University of New York

- Cornell University

Mary Ann McDonald / Getty Images

- Animal Rights

- Endangered Species

Behold the mysterious groundhog. We know them as prognosticators of spring and muses for cult movies, but these furry creatures from the pantheon of giant rodents have other secrets to reveal. Here we tell all.

1. Groundhogs Have Many Aliases

Closely related to squirrels, groundhogs are also known as woodchucks, whistle-pigs, forest marmots, and land beavers. The groundhog ( Marmota monax ) is one of 14 species of marmots, and while most marmots are gregarious and love company, groundhogs are loners.

Groundhogs are the most widespread of all marmots found in North America — their range includes the southeastern U.S. through northern Canada, with some found as far north as southern Alaska.

2. They Are True Hibernators

Groundhog hibernation can last for as long as five months. During this period, groundhogs go into a dormant state — they lose a quarter of their body weight, their body temperature decreases by 60 degrees Fahrenheit, and their heart rate slows to only five or 10 beats per minute. Not all groundhogs experience such a long hibernation, and those that live in the southernmost regions may stay active year-round.

After their months-long hibernation, groundhogs emerge just in time for mating season.

3. They Feast To Survive Winter

In order to prepare for hibernation, these diurnal feeders feast all summer long on plants. They’re particularly fond of the plants and vegetables found in gardens, and are often considered to be pests.

During their summer feast, groundhogs eat as much as one pound of food at a time. Along with vegetation, they also eat grubs, grasshoppers, insects, snails, other small animals, and bird eggs.

4. They’re Impressive Builders

A groundhog’s burrow can extend up to 50 feet long, with multiple levels, exits, and rooms. They even have separate bathrooms. Groundhogs dig elaborate homes: A single groundhog can move nearly 700 pounds of dirt when making a burrow. They also know how to prevent heat loss — they sometimes block the entrances to their burrows using vegetation.

Their burrows aren’t good for everyone. Groundhogs sometimes construct their burrows under building foundations, and they can cause damage to farm equipment that inadvertently crosses paths with a burrow.

5. Their Vacant Dens Are Reused

The elaborate dens built by groundhogs are important for other animals too; red foxes, gray foxes, coyotes, river otters, chipmunks, and weasels often take up residence in homes built by groundhogs.

Sometimes the other animals don’t have to wait until the burrow is vacant. Opossums, raccoons, cottontail rabbits, and skunks sometimes occupy portions of a borrow while the groundhog is hibernating.

6. They Can Climb Trees

While they may not appear particularly agile, groundhogs actually have impressive climbing skills and are quite active. If they can’t get to their burrow quickly enough, their sharp claws come in handy as they are able to climb trees to evade predators.

If they are being pursued and the need arises, groundhogs can also swim to safety, jumping in the water to avoid danger.

7. Their Burrow Led to an Important Discovery

In 1955 the founder of Meadowcroft Rockshelter, Albert Miller, discovered artifacts in a groundhog burrow. An unlikely find, Miller dug further, and kept his discovery under wraps for several years until he obtained the help of archeologist Dr. Jim Adovasio.

After excavating the site and sending materials to the Smithsonian, radiocarbon dating revealed that the artifacts were evidence that the site was inhabited by humans, most likely as a campsite, 19,000 years ago, making it North America’s oldest known location of human habitation.

8. They Have Their Own Holiday

The shadow of Punxsutawney Phil, the most famous rodent prognosticator, has been considered an informal predictor of weather since 1887. According to the NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, Phil’s predictions about extended winter or early spring have been accurate 40% of the time between 2010 and 2019.

As much as we’d like to believe that the reason groundhogs reveal themselves on February 2 is to predict the weather, there is actually a very different reason they emerge. Groundhogs exit their winter slumber for mating purposes. Male groundhogs, who want to get a head start on choosing a mate, are the first to exit the burrow. Timing is everything — groundhogs need to reproduce at the right time to give their offspring the best chance of survival.

" Marmota monax: Woodchuck ." Animal Diversity Web .

Silvestro, Roger. " 10 Things You May Not Know About Groundhogs ." National Wildlife Federation .

Harrington, Monica. " What a Woodchuck Could Chuck. " Lab Animal , vol. 43, no. 117, 2014, doi:10.1038/laban.516

Zervanos, Stam. M., and Carmen M. Salsbury. " Seasonal Body Temperature Fluctuations and Energetic Strategies in Free-Ranging Eastern Woodchucks (Marmota monax) ." Journal of Mammalogy . 2003.

" Marmota monax - Woodchuck ." University of Wisconsin Stevens Point .

" Five Things You Didn’t Know about Groundhogs ." Tufts University .

Swaminathan, Nikhil. " Meadowcroft Rockshelter ." Archaeology Magazine . 2014.

Scofield, David. " Meadowcroft’s Own Groundhog Day ." Senator John Heinz History Center . 2015.

" Groundhog Day Forecasts and Climate History ." National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association's National Centers for Environmental Information .

- 22 Things You May Not Know About Squirrels

- 24 Brilliant Burrowing Animals

- Surprising Ways Animals Stock Up for Winter

- 10 Things You Don't Know About Chipmunks

- 8 Surprising Facts About Badgers

- 17 Animals Amazingly Adapted to Thrive in Deserts

- 15 Baffling Cicada Facts

- Winning Photos From the Wildlife Photographer of the Year Competition

- 13 Interesting Facts About Flying Squirrels

- The Secret to Cooking Amazing Vegetables

- 20 Animals With Completely Ridiculous Names

- The Incredible Secret Lives of Sea Lilies and Feather Stars

- Secret and Old Spice Deodorants Go Zero Waste

- David Attenborough's Netflix Series Reveals 'Secret' Colors in Nature

- 8 Spectacular Caterpillars That Look Like Snakes

- 12 Animals With the Longest Gestation Period

Get the latest news and stories from Tufts delivered right to your inbox.

Most popular.

- Activism & Social Justice

- Animal Health & Medicine

- Arts & Humanities

- Business & Economics

- Campus Life

- Climate & Sustainability

- Food & Nutrition

- Global Affairs

- Points of View

- Politics & Voting

- Science & Technology

- Alzheimer’s Disease

- Artificial Intelligence

- Biomedical Science

- Cellular Agriculture

- Cognitive Science

- Computer Science

- Cybersecurity

- Entrepreneurship

- Farming & Agriculture

- Film & Media

- Health Care

- Heart Disease

- Humanitarian Aid

- Immigration

- Infectious Disease

- Life Science

- Lyme Disease

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Oral Health

- Performing Arts

- Public Health

- University News

- Urban Planning

- Visual Arts

- Youth Voting

- Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine

- Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy

- The Fletcher School

- Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences

- Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging

- Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life

- School of Arts and Sciences

- School of Dental Medicine

- School of Engineering

- School of Medicine

- School of the Museum of Fine Arts

- University College

- Australia & Oceania

- Canada, Mexico, & Caribbean

- Central & South America

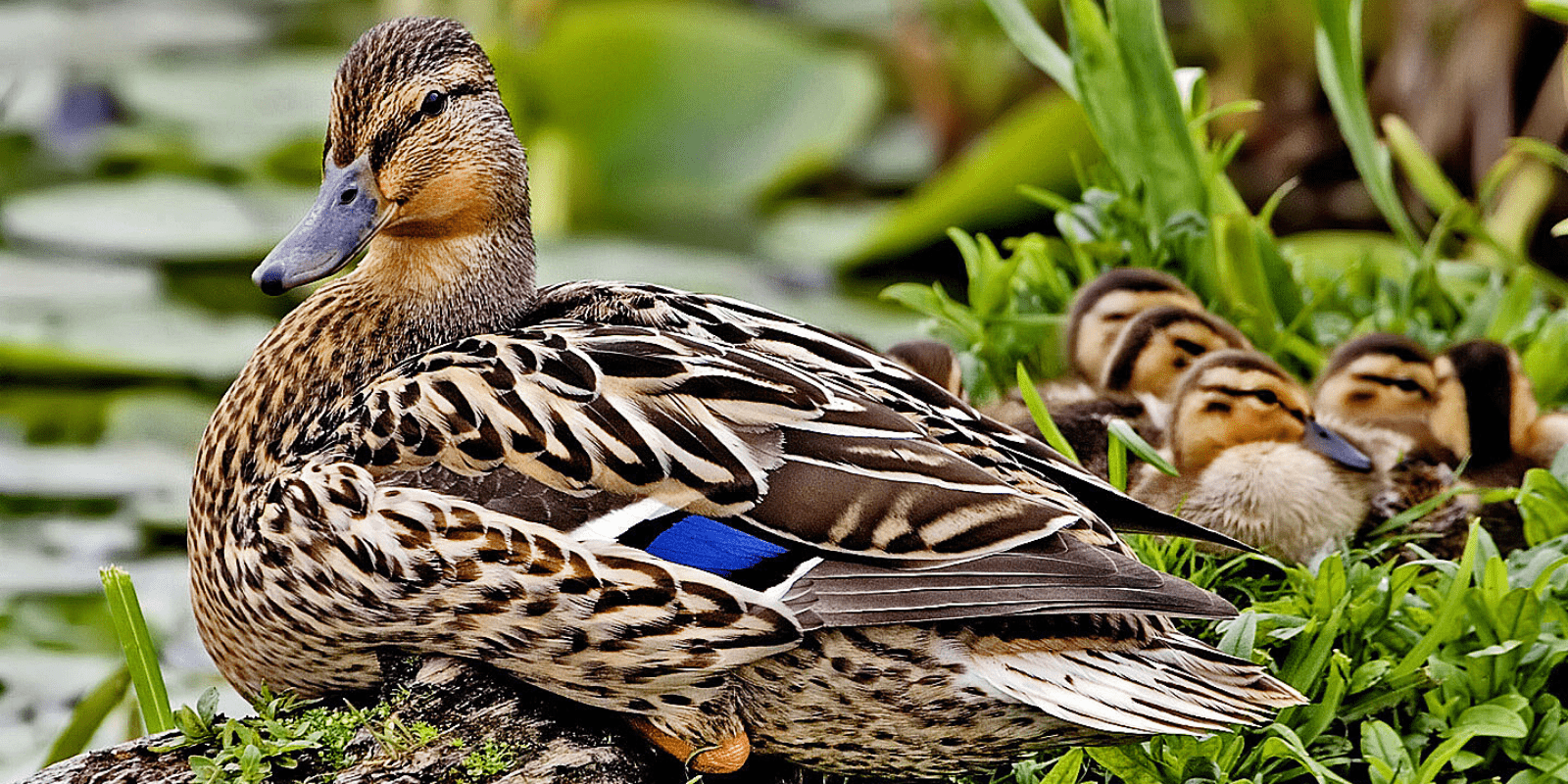

- Middle East

A wildlife camera captured this photo of a groundhog on the Grafton campus of Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University. Photo: Courtesy of Chris Whittier

Five Things You Didn’t Know about Groundhogs

Chris Whittier, assistant teaching professor at Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine, shares the dirt on these important enormous, whistling, burrowing squirrels

While many Americans would recognize famed Punxsutawney Phil as a groundhog, they may not know much else about the species. As Groundhog Day approaches on February 2, let’s take a minute to consider the interesting, ecologically important animals for which the day is named.

For starters, groundhog is a misnomer, said Chris Whittier , D.V.M., Ph.D., V97, assistant teaching professor of conservation medicine at Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University. They are actually in the same family as chipmunks and prairie dogs.

And even though they may be eating your vegetable garden in the summer, “remember that groundhogs are important native wildlife wherever they exist, said Whittier, who is also director of the school’s master’s program in conservation medicine . “If you happen to have conflicts with them in your yard, there are many resources to help, including these strategies from MassWildlife .”

Here are five takeaways from Whittier as we look forward to Groundhog Day:

1. Groundhogs are also known as woodchucks or “whistle-pigs.” The familiar name woodchuck actually has nothing to do with wood, and stems from the Native American names for them: wuchak, wejack , and possibly otchek , which is a name for fishers . The name whistle-pig, which is most common in Appalachia, stems from groundhogs’ habit of making a high-pitched whistling sound, usually as a warning to other groundhogs when they feel threatened. (The pig is similar to how we refer to woodchucks’ rodent-cousin the guinea pig.)

2. They are actually large squirrels. Capable of weighing up to 15 pounds, groundhogs are among the largest members of the squirrel family Sciuridae and within the taxonomic tribe of marmots or ground squirrels—a group that also includes chipmunks and prairie dogs. Like these relatives, groundhogs are powerful diggers that make large, complex underground burrows. These burrows are not only potentially helpful to soils for aeration and nutrient recycling, but they are often used by other burrowing animals such as foxes, opossums, raccoons, and skunks.

Whittier's wildlife camera captured this video of groundhogs on Cummings School's Grafton campus.

3. Groundhogs are important intermediaries in the food chain. Primarily herbivores, groundhogs eat a variety of plants, including from people’s gardens. But they also may eat things we consider pests, such as grubs, other insects, and snails. They are even reported to eat other small animals such as baby birds. Because of their relatively large adult size and burrowing—not to mention climbing and swimming abilities—groundhogs don’t have many predators aside from coyotes, foxes, domestic dogs, and, of course, humans. (However, baby groundhogs sometimes do fall prey to raptors such as hawks, owls, and eagles.)

4. Pregnancy goes by fast for them. Groundhog mating season is in the early spring and, after only a month-long pregnancy, mother groundhogs typically give birth to a litter of two to six blind, hairless babies. Young groundhogs are called kits, pups, or sometimes chucklings. Groundhog families disperse in the fall, and the young reach sexual maturity by two years. Groundhogs typically live three to six years in the wild, but have been reported to live for up to fourteen years in captivity.

5. Groundhogs are among the few species of true hibernators. This is the part of their behavior that has led to North American Groundhog Day tradition. After losing up to half their weight while hibernating, groundhogs usually emerge from their winter burrows in February—hence the date of this holiday. The shadow-observing lore has no scientific basis. It was actually imported from a German tradition that bases forecasting on the behavior of the European badger—a totally unrelated small mammal of the carnivore—as opposed to rodent—order, but one that does also burrow and undergo a less intense form of hibernation.

How Do Deer Survive Harsh Winter Weather?

Is scruffing the best way to handle an upset cat?

How Are Animals Added to the Endangered Species List?

- Get Involved

- Kids & Family

- Educational Resources

- Latest News

- Wildlife Facts

- Conservation

- Garden Habitats

- Students and Nature

- Environmental Justice

10 Things You May Not Know About Groundhogs

The groundhog, also known as the woodchuck or the mouse bear (because it looks like a miniature bear when sitting upright), first won its reputation as a weather prognosticator in 1886, when the editor of western Pennsylvania’s Punxsutawney Spirit newspaper, one Clymer Freas, published a report that local groundhogs had not seen their shadows that day, signaling an early spring.

This story begat Punxsutawney Phil , the legendary woodchuck weathercreature, which begat Ground Hog Day and the familiar idea that Phil (and his namesake successors down through the years) can predict the perpetuation of winter.

It is likely that the story of Phil is based on European beliefs that badgers and hedgehogs can provide signals about the future; lacking those species in his area, old Clymer substituted the local animal that most resembles a badger or a hedgehog.

But the groundhog is much more than a weather rodent. It’s also a real animal with a real life.

Here are 10 things you may not know about this roly-poly rodent:

- Groundhogs are among the few animals that are true hibernators , fattening up in the warm seasons and snoozing for most of three months during the chill times.

- While hibernating, a woodchuck’s body temperature can drop from about 99 degrees to as low as 37 (Humans go into mild hypothermia when their body temperature drops a mere 3 degrees, lose consciousness at 82 degrees and face death below 70 degrees).

- The heart rate of a hibernating woodchuck slows from about 80 beats per minute to 5 .

- Breathing slows from around 16 breaths per minute to as few as 2 .

- During hibernation—150 days without eating—a woodchuck will lose no more than a fourth of its body weight thanks to all the energy saved by the lower metabolism.

- During warm seasons, a groundhog may pack in more than a pound of vegetation at one sitting, which is much like a 150-pound man scarfing down a 15-pound steak.

- To accommodate its bodacious appetite, woodchucks grow upper and lower incisors that can withstand wear and tear because they grow about a sixteenth of an inch each week .

- If properly aligned, woodchuck upper and lower incisors grind away at each other with every bite, keeping suitably short; when not in good order, they may miss one another and just keep growing until they look like the tusks on a wild boar; if too long, a woodchuck’s upper incisors can impale the lower jaw , with fatal results.

- Woodchuck burrows, which the animals dig as much as 6 feet deep, can meander underground for 20 feet or more , usually with two entrances but in some cases with nearly a dozen.

- Burrows provide groundhogs with their chief means of evading enemies, because the rotund little guys (just before hibernation, a hefty woodchuck may tip the scales at 14 pounds) are too slow to escape most predators in a dead heat: the rodents have a top speed of only 8 mph , while a hungry fox may hit 25 mph.

Bonus Fact : Although groundhogs may not be the best weather predictors, they do in fact emerge from dens in early February. This is the practice of males as they rouse themselves to wander around their 2- to 3-acre territories in search of burrows belonging to females, which the males will enter and where they may spend the night. Research suggests that no mating takes place at this time; the visits probably just let the animals get to know one another so that they can get right down to the business of breeding when they emerge for good in March. Outside of the mating season, woodchucks are solitary, except for females with young, which usually are born in early April.

Share & Save

Recovering america’s wildlife act.

This Bill Saves Wildlife in Crisis. Urge Congress to Support It.

The Solar Eclipse and Wildlife

Wild Kingdom Grant Awardees

Charting the Way Forward on Climate

Bringing Offshore Wind to Onshore Communities

New Wetlands Report Shows Accelerating Losses

Girl Boss: Wildlife Edition

The Women’s Environmental Institute

The Importance of Environmental Monitoring

Tour of the Northern Rockies, Prairies, and Pacific Region through Local Authors

Recruiting the 2024 Cohort of Graduate Student Research Fellows

The Multidimensional Impacts of Eco-Green Gardens and Beyond

Plastics Reduction Partner Awardees

Survival of the Coolest

Climate Equity Collaborative’s Inaugural Youth Advisory Council

Would you love me if I was a worm?

Nature-Themed Reading for Black History Month

Earth Tomorrow’s “3’Peat” Service Learning Confluence

QUIZ: To Chill or Not to Chill

Year-Round Bird Feeding

Data-Driven Sustainability: Tracking Tools for K-12 Success

Thank you for protecting wildlife, people, and our planet..

We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Never Miss A Story

PO Box 1583, Merrifield, VA 22116-1583 The National Wildlife Federation is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

February 2, 2012

7 Things You Didn't Know About Groundhogs

By Jason G. Goldman

This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Happy Groundhog Day! Today is the day each year in which we look towards a giant rodent to find out how much more winter we'll have to endure. This year, we probably know the answer: winter hasn't been very wintery, even for Los Angeles. Which, well, isn't ever really wintery at all.

According to tradition, the groundhog ( Marmota monax ) peeks out of its burrow today, and checks to see if it has a shadow. If sunny enough for a shadow, the groundhog will return to the comfort of its burrow, and winter will continue for an additional six weeks.

In honor of the holiday, I've rounded up seven things about groundhogs that you probably didn't know. One for each extra week of winter we're going to have, plus one extra for good luck.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

1. A groundhog by any other name. Groundhogs are also variously referred to as woodchucks, whistle-pigs, or land-beavers. The name whistle-pig comes from the fact that, when alarmed, a groundhog will emit a high-pitched whistle as a warning to the rest of his or her colony. The name woodchuck has nothing to do with wood. Or chucking. It is derived from the Algonquian name for the critters, wuchak.

2. Home sweet home. Both male and female groundhogs tend to occupy the same territories year after year. For females, there is very little overlap between home ranges except for the late spring and early summer, as females try to expand their territories. During this time, their ranges may overlap by as much as ten percent. Males have non-overlapping territories as well, though any male territory coincides with one to three mature females' territories.

3. Baby groundhogs! Infants stick around home for only about two to three months after being born in mid-April, and then they disperse and leave mom's burrow. However, a significant proportion - thirty five percent - of females stick around longer, leaving home just after their first birthdays, right before mom's new litter arrives.

4. Family values. In general, groundhog social groups consist of one adult male and two adult females, each with an offspring from the previous breeding season (usually female), and the current litter of infants. Interactions within a female's group are generally friendly. But interactions between female groups - even when those groups are shared by the same adult male - are rare and aggressive. Even though daddy woodchuck doesn't live at home, from the breeding season through the first month of the infants' lives, he visits each of his female groups every day.

5. Medical models. Groundhogs happen to be a good animal model for the study of hepatitis B-induced liver cancer. In fact, if infected with Woodchuck Hepatitis B virus, the animal will always go on to develop liver cancer, making them useful for the study both of liver cancer and of hepatitis B.

6. Look up! Though they spend most of their time on or under the ground, groundhogs can also climb trees.

7. Eskimo kisses. Groundhogs greet each other with an odd variation of the eskimo kiss : one groundhog approaches and touches his or her nose to the mouth of the second groundhog. Or, as scientists call it, they make "naso-oral contact."

Meier, P. (1992). Social organization of woodchucks (Marmota monax) Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 31 (6) DOI: 10.1007/BF00170606

Photo: Wikimedia Commons /April King.

Facts about groundhogs and why it's hard to get rid of them

Following is a transcript of the video.

Narrator: If you only saw them on their big day every February, you might think that groundhogs are pretty shy animals. They're actually anything but.

Reporter 1: What started out as a funny sight turned a little bit scary for a man from Hampton.

Reporter 2: You see those teeth on that guy?

Narrator: Imagine finding this at your front door. They might be called ground...hogs, but they're not related to hogs at all. They're actually the largest species in the squirrel family, and they are equally ubiquitous.

You can find groundhogs all over the central and eastern US. In Arkansas, for example, there's an estimated 67,000. That's about one groundhog for every 45 humans.

And wherever they are, they make their presence known. Similar to beavers, groundhogs have rapidly growing incisors, which they keep from growing too long by chewing and gnawing on just about anything they can get their teeth on, including cables, hoses, and other rubbery materials. One groundhog reportedly chewed the wires inside of a car in Nebraska, costing $1,800 in damage repairs.

But they don't just wreak havoc aboveground. Groundhogs are burrowers by nature. They live, breed, and hibernate underground. But before they can do that, they have to dig, and dig, and dig, and dig, and dig, and dig. Their tunnels can be anywhere from half a meter deep to 1 1/2 meters deep, and they can be up to 18 meters long. That's about as long as a bowling lane.

Their burrows can harm crops, weaken foundations of buildings, and damage farm equipment that may fall in. In one case, it's been said they dug up bones in a cemetery. But even if you don't have a lot of land, your home could still be a target. Groundhogs like grassy open areas because they don't have big obstacles like tree roots and giant rocks. So that pretty little garden or that freshly mowed lawn, that is a free-for-all for groundhogs.

And a fence won't keep them out either because they could just burrow underneath it or climb over. Yeah, that's right, groundhogs can climb too. For example, during floods, they've been known to climb chain-link fences to escape rising water. And just about the only way to keep them out is an electric fence, which can cost between $100 and $350 depending on the size of your yard. And removing a groundhog from your property? Getting a wildlife control professional to help could cost about $400 per groundhog!

Worst comes to worst, you definitely don't want to try and handle them on your own since some groundhogs can be pretty aggressive animals. For example, in 2018, a groundhog chased a woman in the parking lot of her office building. Luckily, she made it to her car. But even then, when her coworkers came to help her, the groundhog forced them to retreat back inside. Even worse, groundhogs have been known to carry rabies, which can make them even more aggressive and dangerous. So maybe don't keep them near your face.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This video was originally published in May 2019.

More from Science

- Main content

The groundhog, or woodchuck, is one of 14 species of marmots, a subgroup of the squirrel family . One of the largest members, groundhogs live a feast-or-famine lifestyle: they gorge themselves all summer to build up plentiful reserves of fat, then retreat to their underground burrows to snooze through the winter while drawing their sustenance from body fat. During hibernation, the animal’s heart rate plunges , and its body temperature is not much warmer than the temperature inside its burrow.

Groundhog Day

Groundhog hibernation gave rise to the popular U.S. custom of Groundhog Day, held on February 2 every year. Tradition dictates that if a groundhog comes out of its burrow and sees its shadow, there will be six more weeks of winter. If not, spring will come early. A comprehensive study from 2021 showed the tradition is a matter of chance—groundhogs make correct predictions only 50 percent of the time.

Groundhogs are widely distributed across North America, ranging as far south as Alabama and as far north as Alaska. They build extensive burrows —anywhere from eight to 66 feet long—with multiple entrances and rooms, including bathrooms. Some groundhogs even have more than one burrow. But these mammals tend to keep to themselves , only seeking one another out when it’s time to mate.

Reproduction

After roughly three months of hibernation, evidence suggests that male groundhogs wake up early to prepare for the mating season. As early as February, they leave their burrows to scope out where females are hibernating. Then they go back to sleep for another month or so until it’s time to mate.

Mating season starts in early March, ideal timing as food becomes more abundant—and there’s just enough time to start packing on the body fat they’ll need for the winter ahead. Females welcome a litter of perhaps a half-dozen newborns, which stay with their mother for several months.

Behavior and diet

Though they are usually seen on the ground, groundhogs can climb trees and are also capable swimmers. These rodents frequent the areas where woodlands meet open spaces, like fields, roads, or streams. Here they eat grasses and plants as well as fruits and tree bark. Groundhogs are the bane of many a gardener as the animals can decimate a plot while voraciously feeding during the summer and fall seasons.

DID YOU KNOW?

- History & Culture

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Need pest help? Save $50 on your first recurring service today with code GET50

Groundhog Facts & Information

Protect your home or business from groundhogs by learning techniques for identification and control.

How to Prevent Groundhogs

What you can do.

To learn more about groundhogs and how to protect your yard from becoming their new home, call your Orkin Pro .

Behavior, Diet & Habits

Understanding groundhogs, what do groundhogs look like.

Groundhogs are large rodents with solid, chunky bodies covered in brownish-gray fur. Groundhogs have short tails and four legs. Their front feet have long, curved claws that are used for digging their burrows and they have four large, very obvious chisel-shaped incisors for chewing. A fully grown adult groundhog’s head and body combined can be up to about 2 feet long. A groundhog’s lifespan is about 6 years.

What's the Difference Between Groundhogs and Woodchucks?

There is no difference between a groundhog and a woodchuck, and the terms actually are interchangeable. Groundhogs got their name from the Algonquin tribe of Native Americans, who originally called them “wuchak.” English settlers, in trying to use that word, likely came up with the name “woodchuck.” Groundhogs are also called whistle pigs since they emit a shrill “whistling-like” sound when they are disturbed; they may also be called forest marmots and land beavers.

Groundhog Behavior and Habitat Facts

Groundhogs construct their homes by burrowing soil along roadsides, in fields and yards, at the base of trees and around building foundations. Burrows can be as deep as five feet, usually with more than one entrance. The burrow system is where they raise their young, are sheltered from predators and the elements, and where they hibernate during cold weather. Groundhogs usually stay close to their burrow and generally don’t travel more than 150 feet away from the burrow to feed. Although groundhogs prefer to burrow under sheds or other outdoor structures, they may burrow in crawlspaces under homes.

Groundhogs not only create unsightly burrows but will eat almost any kind of plant. Their digging to create burrows and feeding on various plants usually damages lawns and landscaping. Groundhogs are herbivores and prefer tender plants, like those that are usually found in home gardens. Gardeners should be especially concerned since groundhogs like to consume garden vegetables, especially tomatoes.

More Resources

Dig deeper on groundhogs.

Does Orkin Help With Raccoons, Rats, Varmints or Wildlife?

Rodent Infestation

Rodent Identification

How To Neutralize Dead Rodent Smells

Rodent Sounds

Connect with Us

Our customer care team is available for you 24 hours a day.

Find a Branch

Our local Pros are the pest experts in your area.

Get a Personalized Quote

We will help you find the right treatment plan for your home.

- Share full article

Groundhogs Emerge From the Scientific Shadows

New research aims to shed light on the social habits of the popular, but often misunderstood, animal.

Researchers hope that a deeper appreciation of groundhog sociality may help people become more sympathetic to them. Credit...

Supported by

By Brandon Keim

Photographs by Greta Rybus

- Published Feb. 1, 2022 Updated Feb. 3, 2022

FALMOUTH, Maine — Groundhog Day may be a tongue-in-cheek holiday, but it remains the one day earmarked in the United States for an animal: Marmota monax, the largest and most widely distributed of the marmot genus, found munching on flowering plants — or, at this time of year, snuggling underground — from Alabama to Alaska.

Yet, for all their cultural prominence, groundhogs remain, as it were, in a bit of a shadow. Relatively little is known about their social life. They are thought of as solitary, which is not precisely wrong, but neither is it entirely accurate.

“These guys are much more social than we thought,” said Christine Maher, a behavioral ecologist at the University of Southern Maine and one of the few scientists to study groundhog behavior.

Dr. Maher arrived in Maine in 1998 with a keen interest in animal sociality. Marmots, a genus spanning 15 species of varying sociality — including alpine marmots living in multigenerational family groups, semi-social yellow-bellied marmots and ostensibly antisocial groundhogs — were a natural subject.

She found an ideal study site at the Gilsland Farm Audubon Center, a 65-acre sanctuary of rolling meadows and forests on the coast of Falmouth, Maine. There, she has tagged no fewer than 513 groundhogs, following their fates and relationships in fine-grained detail.

The resulting family trees and territorial maps, along with the records of their interactions and daily activities, are singular. “Nobody had looked at them over time as individuals,” Dr. Maher said.

Gilsland’s groundhogs won’t emerge until late February, but one morning last summer, Dr. Maher was out setting peanut butter-baited live traps around a shrub-hidden burrow beside the visitor center. The peanut butter soon proved irresistible.

The trap afforded a rare up-close view of a groundhog: sleekly sturdy, with small, serious eyes, delicate whiskers and fur that shaded from auburn on her broad chest to a mélange of chestnut, straw and russet across the rest of her body. One round ear bore a tiny bronze tag inscribed with the number 580.

“This is Torch,” said Dr. Maher, who names each of her study subjects. Torch was a first-time mother. Dr. Maher deftly transferred her to a thick bag to allow for safe weighing. She also took a hair sample for later DNA analysis and measured how much Torch wriggled during several 30-second intervals — a simple test of personality .

After returning Torch, irritated but unharmed, to her burrow, Dr. Maher started a circuit of Gilsland. She checked several still-empty traps for Barnadette, who was raising her pups beneath an old barn. Near the barn was a sprawling community garden and the smorgasbord of their compost pile.

As anyone whose vegetable garden is visited by groundhogs can attest, the arrangement created a certain tension. Charles Kaufmann, one of the garden’s coordinators, acknowledged that conflicts with gardeners had occurred, but had been resolved peacefully. Among their peacekeeping tools are floppy fences that groundhogs struggle to climb.

“Audubon is for the preservation and appreciation of the natural world,” Mr. Kaufmann said. “We feel bound to live within that perspective and philosophy.” Also, “groundhog pups are just the cutest things in the world.”

A coterie of groundhogs

Along a freshly mowed path leading from the gardens into a meadow, Dr. Maher spotted a groundhog. Through her scope she identified Athos, a yearling and a sibling to Porthos and Aramis.

She named them after the Three Musketeers, which was a trick to help her remember them — but it was also fitting. A few days prior, she had observed them hanging out together at the burrow where they were born.

Such interactions belie the species’ solitary reputation, and conventional wisdom holds that juvenile groundhogs leave home to seek new territories just a few months after they are born. At Gilsland, Dr. Maher has found that roughly half the juveniles remain for a full year in the territory of their birth. When they finally depart, they often stay nearby.

“It depends on whether they can strike an agreement with their mother,” Dr. Maher said. “Some moms are willing to do that. Others are not.” Mothers may even bequeath territories to their daughters. Dr. Maher suspected that Athos’s mom had left Athos the family burrow.

As groundhogs mature, their interactions become less amicable — the Three Musketeers most likely would not lounge together for much longer — but neither are they entirely antagonistic. Dr. Maher has also found her groundhogs to be friendlier to relatives than to unrelated individuals.

The result is a community of related groundhogs whose territories overlap. Some individuals do venture farther afield or arrive from afar, which helps keep the gene pool fresh — but a kinship-based structure remains. Gilsland Farm’s groundhogs could be understood as living in something like a loose-knit clan, its members keeping their distance but still crossing paths and maintaining relations.

“You have these whole networks of sisters living together, aunts, cousins, extending outward,” Dr. Maher said. “This had been hinted at, but I don’t think people knew just to what extent it was happening.”

Daniel Blumstein, an evolutionary biologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, who leads a long-term study of yellow-bellied marmots at Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory, said that Dr. Maher’s data was “increasing our understanding of the benefits of having subtle social relationships.” He added, “She is allowing us to appreciate more the nuanced complexity of less in-your-face social relationships.”

An open question is whether the patterns Dr. Maher sees at Gilsland Farm are common in other groundhog populations. Their behaviors may vary depending on local circumstance, she said.

Gilsland Farm’s groundhogs live on what amounts to a habitat island; to the west is an impassable estuary, to the east is a dangerous highway. North and south are suburban neighborhoods rich in potential habitat but bristling with unwelcoming homeowners. “They’re seen as varmints,” Dr. Maher said of the groundhogs. “People don’t seem to give them much thought.”

An ancestral state

When young groundhogs do leave Gilsland Farm, they tend to end up run over or shot. So there are advantages to staying home, provided there is enough food. There are also mutual benefits to be shared: For example, a whistle of alarm occasioned by an approaching fox would be heard by all nearby.

From the bird’s-eye vantage of evolution, the genes of somewhat-social groundhogs spread more readily than more solitary ones, and Dr. Maher thinks that it actually represents a return to something like an ancestral state. Before European colonization, groundhogs would have lived in clearings — created by fires, storms, beaver activity and Indigenous practices — separated by inhospitable forests.

“They were forced to live closer together, so they were more tolerant of each other and more social,” she said. “When Europeans cleared all that forest, they actually increased the amount of habitat available for groundhogs. Perhaps they became less social because they could spread out.”

The neighborhoods don’t have to be dangerous, though. Dr. Maher hopes that a deeper appreciation of groundhog sociality may help people become more sympathetic to them and even graciously share the suburban landscape with them, the way the Gilsland Farm gardeners do.

Her work also intersects with some nonscientific efforts, such as the social media presence of Chunk the Groundhog — followed by more than 500,000 people on Instagram — and the amateur naturalists whose 15 years of backyard observations yielded the uniquely intimate accounts of Woodchuck Wonderland .

“People don’t usually have that insight into the way they live,” said John Griffin, director of Urban Wildlife Programs at the Humane Society of the United States. In his own work, Mr. Griffin often encounters a sense of groundhogs as intruders. He thinks that a lack of familiarity — for all their ubiquity, groundhogs are often glimpsed only along roadside verges or dashing for cover — leads to intolerance or an exaggerated sense of risk.

Appreciating that animals have social lives can change how they are perceived, Mr. Griffin said. “I don’t know how to quantify it, but I think it’s valuable,” he said. “Conflict resolution is all about perspective.”

Tolerance would benefit more than groundhogs. Their digging helps aerate and enrich soil, Dr. Maher said, and many other creatures use their burrows. Groundhog burrows may even create hot spots of local biodiversity .

Athos, at least, would be spared the suburban gauntlet. “The fact that she hasn’t left yet makes me think she’ll stick around,” Dr. Maher said.

Athos moved slowly along the path, eating the clover and dandelions that would sustain her through the coming winter. Every so often she stood on two legs and looked around. Dr. Maher noted her activities on a hand-held computer.

When an approaching pedestrian sent Athos scurrying into the tall grass, Dr. Maher explained how the system worked. “I just key in two-letter codes for their behavior,” she said. “Feed. Walk. Alert. Run. Groom. Dig, occasionally. They don’t have a huge repertoire.”

She sounded slightly self-conscious about this. Passers-by, she admitted, are sometimes amused that she spends so much time watching seemingly boring creatures.

With a rustle Athos returned to the path. “Oh, there she is!” Dr. Maher exclaimed, the enthusiasm in her voice suggesting that, after all these years, she still finds groundhogs quite interesting indeed.

Advertisement

Groundhogs are more than weather predictors: Here are some lesser known facts about them

Why do punxsutawney phil and other groundhogs really come out in february hint: not to see their shadows. here are some facts about the humble critters for groundhog day:.

This Friday, Punxsutawney Phil and other less-famous groundhogs across the nation will emerge from their dens to determine whether six more weeks of winter are in store.

The mammal's prognostications aren't likely to settle the question of our future weather *ahem* beyond a shadow of a doubt. But don't blame the groundhogs: Research indicates they emerge in February not to see their shadow, but to, well, get frisky.

If you didn't know that about the large squirrel , which is the most widespread North American marmot species , there's probably a lot you don't know about the humble groundhog.

Here are some facts about the stocky, solitary critters that you might not have heard before:

How accurate is Punxsutawney Phil? His Groundhog Day predictions aren't great, data shows.

Groundhogs are 'true hibernators' – unlike those bear imposters

While hibernation is common among many animals, groundhogs enter a level of winter dormancy that is more unusual.

Unlike, say, bears, groundhogs don’t just enter a light-sleep state characterized by inactivity. Rather, the creatures’ reduced metabolism, slower heart rate, and lowered body temperature make them what experts consider to be “true hibernators,” according to the National Park Service .

While hibernating, a groundhog's body temperature can drop from about 99 degrees Fahrenheit to as low as 37 degrees, a temperature cold enough to be fatal to humans, who lose consciousness at about 82 degrees. Similarly, the heart rate of a hibernating groundhog slows from about 80 beats per minute to just five, while breathing slows from around 16 breaths per minute to as few as two, according to the National Wildlife Federation .

After fattening up in the warmer seasons, groundhogs spend nearly three months – or 150 days – hibernating without eating a single thing. But their generous food stores mean the animals are unlikely to lose more than a fourth of their body weight, the NWF said.

The reason groundhogs actually emerge in February

Not to worry though: Woodchucks called upon for winter prognosticating duties on Groundhog Day aren't necessarily being unnaturally stirred.

Researchers have found that groundhogs do in fact emerge from their dens in early February, but not to determine whether they’ll see their shadow, according to the National Wildlife Federation . Rather, it’s believed that males will rouse themselves around this time to wander their territories in search of a potential mate, the National Wildlife Federations said.

Once they find a burrow belonging to a suitable female, the male will enter and spend the night. Before you raise your eyebrows, no funny business is taking place – yet. Research suggests that the visit is just to allow the animals time to get to know each other (think of it as a blind date, of sorts.)

That way, when they emerge from hibernating for good in March, they’re ready to get down to business.

What big, sharp teeth groundhogs have

With a voracious appetite, groundhogs are known to put away more than one pound of vegetation in one sitting. According to the NWF, that’s akin to a 150-pound human scarfing down a 15-pound steak.

Though the herbivores only feast on veggies, groundhogs still have formidable teeth.

Their upper and lower incisors can grow about a sixteenth of an inch each week. If not properly ground down while they gnaw away on their food, they grown to look like the tusks of a wild boar.

And if their incisors grow too long, the animals can fatally impale their lower jaw, the NWF said.

Intricate groundhog burrows provide protection from predators

Extensive burrow systems created by groundhogs are designed to serve as protection from predatory enemies.

The animals’ homes can be up to six feet deep with 20 feet of weaving chambers and tunnels leading to at least two exits – and sometimes nearly a dozen. The design provides a crucial advantage to a fleeing groundhog, which is otherwise relatively slow moving compared to invading animals like foxes who may see them as little more than a yummy dinner, the NWF said.

Human activity has shaped the animals’ natural habitat, which covers a wide geographic range and many ecosystems, from low elevation forests to small woodlots, fields and pastures. Forest-clearing, road-building and human agriculture have been a net good for groundhogs, increasing their access to food and providing them places to construct their dens, according to the Animal Diversity Web operated by the University of Michigan.

Humans, though, may not always see the mammals themselves as a benefit to have around. Groundhogs are known to destroy gardens, pastures, and agricultural crops, while their burrows have been known to injure livestock and damage farm equipment and building foundations.

Groundhogs like to be alone, and will hiss and bark to keep it that way

While groundhogs males are known to fraternize with multiple mates per season, that’s about as social as the species is known to be.

Even those interactions are limited purely to reproduction, as the male doesn’t stick around to rear his own offspring, according to the University of Michigan.

The older, more dominant male groundhogs tend to be territorial – aggressively lording over their dominions while the younger ones are left to be nomadic.

Though not known for their friendliness, groundhogs will sometimes great each other nose to nose.

More often, though, they react to unwelcome guests by arching their bodies, baring their teeth and raising their tails. According to the University of Michigan, they also hiss, growl, shriek, whistle, teeth-chatter, bark and even fight to ward off predators or establish social rank.

Eric Lagatta covers breaking and trending news for USA TODAY. Reach him at [email protected]

Squirrels at the Feeder

Learn About Chipmunks, Bats, Squirrels and Birds!

Where Groundhogs Live in the United States

May 13, 2023 By David

Groundhogs, also known as woodchucks, are intriguing creatures that have captured the curiosity of many. Their burrows and underground dwellings are often the subject of fascination, and people wonder where groundhogs live in the United States.

In this article, we will delve into the habitats of groundhogs and explore their distribution across different regions. So, let’s dig in and discover the hidden abodes of these furry residents!

Where do Groundhogs Live in the United States?

Groundhogs can be found throughout the eastern and central parts of the United States. Their range stretches from the Atlantic coast to the Great Plains region. Let’s take a closer look at the specific habitats and regions where groundhogs thrive:

1. Northeastern United States

The northeastern states, including Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Maryland, are home to a significant population of groundhogs.

The varied landscapes and abundant vegetation in these states provide ideal conditions for groundhog burrowing and foraging.

2. Midwestern United States

Moving westward, groundhogs also inhabit several states in the Midwest, such as Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota.

The fertile soils and expansive grasslands of this region offer ample opportunities for groundhogs to construct their burrows and create stable dwellings.

3. Central United States

Groundhogs have a presence in the central parts of the country as well. States like Iowa, Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma provide suitable habitats for these creatures.

The rolling plains and prairies of the central United States offer favorable conditions for groundhogs to establish their burrows and thrive in the grassy landscapes.

4. Southeastern United States

Although less common in this region, groundhogs can still be found in parts of the southeastern United States.

States like Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama have small populations of groundhogs. However, the warm and humid climate of the southeast may limit their distribution compared to other regions.

5. Southwestern United States

Groundhogs are not as prevalent in the southwestern United States, but some sightings have been reported in states like Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, and Oklahoma.

The drier climate and different vegetation types pose challenges for groundhogs, making their presence less common compared to other areas.

6. Western United States

Groundhogs are typically absent from the western United States, including states like Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Washington, Oregon, and California.

The arid conditions and rugged terrains of the western states are less favorable for groundhog populations.

Groundhog Habitats: Digging into the Details

Groundhogs are renowned for their impressive burrowing abilities, and their habitats revolve around these intricate underground dwellings. Let’s delve into the details of groundhog habitats and explore the unique features of their burrows:

1. Burrow Construction

Groundhogs are proficient excavators, capable of creating extensive burrow systems. Their burrows typically consist of multiple chambers, including a sleeping chamber, a nesting chamber for raising their young, and separate chambers for storing food and waste.

These burrows serve as their shelters, providing protection from predators and extreme weather conditions.

2. Soil Composition

Groundhogs prefer loose, well-drained soils for their burrow construction. Sandy or loamy soils are ideal, as they are easier to dig and maintain the stability of the burrow structure. These types of soil also allow for better drainage, preventing flooding within the burrow during heavy rains.

3. Burrow Entrances

Groundhogs usually have several entrances to their burrows, strategically positioned to provide multiple escape routes in case of danger. The entrances are often marked by mounds of soil, which are created during the digging process. These mounds serve as a visual indicator of groundhog activity and are commonly referred to as “groundhog holes.”

4. Vegetation Surroundings

Groundhogs prefer habitats with ample vegetation, as it provides them with a source of food and cover. They are commonly found in grassy fields, meadows, open woodlands, and the edges of forests. Groundhogs are herbivores and feed on a variety of plants , including grasses, clover, dandelions, and various other leafy greens.

5. Proximity to Water Sources

While groundhogs primarily inhabit dry land, they are known to establish their burrows near water sources. This proximity allows them easy access to water for drinking and helps regulate the humidity levels within their burrows. Groundhogs may dig their burrows near streams, ponds, or other bodies of water.

6. Sunning Areas

Groundhogs are diurnal creatures and enjoy basking in the sun. They often create open areas or clearings near their burrows, where they can sunbathe and warm themselves. These sunning areas are usually close to the burrow entrances and provide a comfortable spot for groundhogs to soak up the sun’s rays.

FAQs About Groundhog Habitats

Do groundhogs live in urban areas? Groundhogs can adapt to urban environments if suitable habitats are available. However, they are more commonly found in rural and suburban areas with open spaces and vegetation.

Can groundhogs share burrows? Groundhogs are generally solitary animals and prefer to have their own burrow systems. However, in some cases, multiple groundhogs may inhabit the same burrow if there is enough space and resources.

Are groundhogs territorial? Yes, groundhogs can be territorial and mark their burrows and surrounding areas with scent to ward off intruders.

How deep do groundhog burrows go? Groundhog burrows can extend several feet below the ground, with depths ranging from 2 to 6 feet (0.6 to 1.8 meters). Some burrows may even reach depths of up to 10 feet (3 meters).

Do groundhogs hibernate in their burrows? Yes, groundhogs are true hibernators . During the winter months, they retreat to their burrows and enter a state of deep sleep, known as hibernation. Their body temperature drops, and their metabolic rate significantly decreases to conserve energy.

How far do groundhogs venture from their burrows? A: Groundhogs have a limited range, typically staying within 150 to 300 feet (45 to 90 meters) of their burrows. They venture out to forage for food, but their burrows serve as a safe retreat where they spend the majority of their time.

Conclusion: Unveiling the Groundhog’s Hidden Habitat

Groundhogs, with their remarkable burrowing abilities, have adapted to a range of habitats across the United States. From the northeastern states to the central regions, these furry creatures have carved out their underground homes. While they prefer areas with loose soils, ample vegetation, and access to water sources, groundhogs have also managed to thrive in suburban and even urban environments.

Understanding where groundhogs live in the United States allows us to appreciate their remarkable adaptations and the ecological role they play. Their burrows provide shelter for other wildlife species and contribute to soil aeration and nutrient cycling. So, the next time you spot a groundhog or stumble upon a groundhog hole, take a moment to marvel at the intricate world beneath the surface.

Scrap the trap when evicting wildlife

Trapping animals and relocating them isn't the best option

A raccoon in the chimney, a groundhog under the shed, a skunk under the back porch … when confronted with wildlife living up-close in their own homes or backyards, well-meaning but harried homeowners often resort to what they see as the most humane solution—live-trapping the animal and then setting them free in a lush, leafy park or other far-away natural area.

It sounds like a good idea, but the sad truth is that live-trapping and relocation rarely ends well for wildlife, nor is it a permanent solution. Why isn’t this approach as humane and effective as it seems and what other options do caring people have when wildlife conflicts arise? Read on for the answers—and some solutions!

Wild nursery

Between March and August, raccoons, skunks, groundhogs and other animals may choose shelter in, around and under a home because they need a safe place to bear and rear their young. Well-adapted to urban life, they will opt to nest in safe, quiet and dark spaces—such as an uncapped chimney or under the back porch steps—if given the opportunity. You may only see one animal, but during this time, assume that any wild animal denning or nesting around a home is a mother with dependent babies.

Unintentional orphans

Not recognizing that dependent young may be present when live-trapping and relocating wildlife during the spring and summer often has tragic consequences. Wild animal babies are unintentionally orphaned and too often die of starvation, because their mother is trapped and removed.

The dangers of relocation

Although homeowners mean well, wild animals do not “settle in” quickly to new surroundings, no matter how inviting that habitat may seem to humans. In fact, the odds are heavily stacked against any animal who is dumped in a strange park, woodland or other natural area.

A 2004 study of grey squirrels who were live-trapped and relocated from suburban areas to a large forest showed that a staggering 97 % of the squirrels either soon died or disappeared from their release area. Take it from the animals' point of view:

- Suddenly in an unfamiliar place, they are disoriented and don’t know where to find shelter, food or water.

- They're in another animal’s territory and may be chased out or attacked.

- They don’t know where to go to escape from predators.

- They may desperately search for babies that they are now separated from.

In the meantime, their helpless young are slowly dying. Even if the orphaned young are discovered, rescued and taken to a wildlife rehabilitator to be reared, it remains a bleak situation for both mother and offspring; one that could have been easily prevented.

No matter how big or small your outdoor space, you can create a haven for local wildlife. By providing basic needs like water, food and shelter, you can make a difference in your own backyard.

Patience, it's a virtue

If you discover a wildlife family nesting in or around your home, the ideal response is patience.

If the animals are not causing damage or harm, you can be assured that once the young are big enough to be out and about, the birth den will have served its purpose. The denning and nesting season is short. Be tolerant and wait a few weeks until the family has vacated the premises and you’ll prevent orphaning of the young altogether. Then you can make repairs to prevent animals from moving in again.

If you can’t wait for the animals to leave on their own, the next best strategy is humane eviction—gently harassing the animals so they’ll move to an alternative location. Wild animals have a sophisticated knowledge of their home ranges (the area in which they spend almost their entire life). Alternative places of refuge are part of that knowledge or cognitive map. Litters can, and will, be moved if disturbed.

Try using a combination of unpleasant smells and sounds. The size of the denning space and the amount of ventilation will largely influence if such repellents will work. We recommend using rags soaked in a strong smelling substance such as cider vinegar ( not ammonia), lights and a blaring radio during nighttime hours to convert an attractive space (quiet, dark and protected) into one that is inhospitable.

Excluding unwanted guests

Repellents provide a temporary solution at best. To permanently prevent animals from using those same spots in the future, you’ll need to seal off any denning areas. Make sure all animals are out before sealing off any space. Remember, during the spring and summer months, it is extremely likely that the animal denning under your steps or elsewhere around your home is a female with dependent young. Make sure that mother and young are able to remain together to prevent any of them from dying cruel deaths.

If you can find the entry/exit holes, an easy way to determine if the den has been vacated is to loosely cover or fill it with a light material, such as newspaper or insulation. This way the occupant will have to push the obstruction aside to get out or come back in. If the block hasn’t moved for three to four days (and it’s not the dead of winter), the den has been vacated and it’s safe to make repairs.

These suggestions are general guidelines only. Recommended methods for resolving conflicts with wildlife may depend upon additional aspects of the situation and the species involved.

But what if ... ?

When the only other option is killing, we sometimes agree that relocation, which gives the wild animal at least a chance, is acceptable. Much depends on the species involved, the time of year, the area into which relocation occurs and other factors—too many to write a general prescription.

For example, relocating an opossum, an animal that tends to wander all its life and often has no fixed home range (and carries their babies with them), could be seen as more acceptable than relocating a squirrel in mid-winter. For squirrels, it is a death sentence, since they would no longer have access to their food cache on which they survive the winter. There are times and circumstances when relocation is surely a better alternative than certain death.

Every day, more and more wildlife habitats are lost to the spread of development. Your gift can help create more humane backyards to protect all animals.

How Groundhog Day came to the U.S. — and why we still celebrate it 138 years later

Updated February 2, 2024 at 8:19 AM ET

On Friday morning, thousands of early risers either tuned in or bundled up to watch Punxsutawney Phil emerge from a tree stump and predict the weather.

The groundhog — arguably the most famous member of his species and the most recognizable of all the country's animal prognosticators — did what he has done for the last 138 years: search for a sign of spring in front of a group of top hat-wearing handlers and adoring fans at Gobbler's Knob in Pennsylvania.

And happily, for the first time in four years , he did.

"What this weather did not provide is a shadow or reason to hide," a handler read off the scroll he said Phil had chosen. "Glad tidings on this Groundhog Day, an early spring is on the way!"

Tradition says that North America will get six more weeks of winter if Phil sees his shadow and an early spring if he does not. Statistics say not so much: Phil's accuracy rate is about 40% over the last decade.

Plus, human meteorologists have far more advanced methods for predicting the weather now than they did when Phil first got the gig in 1887.

Why, then, do we continue looking to creatures for answers on Feb. 2, year after year after year? (One could say it's almost like the 1993 comedy "Groundhog Day" ... or even exactly like that.)

There's still a lot we can learn from Groundhog Day, both about our climate and our culture, several experts told NPR.

Daniel Blumstein is a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UCLA who studies marmots , the group of 15 species of large ground squirrels that includes groundhogs. His department always has a Groundhog Day party, even in perennially-sunny Los Angeles — but he says you don't have to be a "marmot enthusiast" (as he describes himself) to get something out of the day.

"I hope that people have some greater appreciation of marmots and nature, and I hope that people have a chuckle over the idea that it's the middle of the winter and we're hoping that a rodent will tell us what the future is," says Blumstein.

Groundhog Day has its roots in ancient midwinter ceremonies

How did the U.S. end up celebrating Groundhog Day in the first place?

It dates back to ancient traditions — first pagan, then Christian — marking the halfway point between the winter solstice and spring equinox, says Troy Harman, a history professor at Penn State University who also works as a ranger at Gettysburg National Military Park.

The Celtic tradition of Imbolc , which involves lighting candles at the start of February, goes as far back as the 10th century A.D.

The Christian church later expanded this idea into the festival of Candlemas , which commemorates the moment when the Virgin Mary went to the Temple in Jerusalem 40 days after Jesus' birth to be purified and present him to God as her firstborn.

On that feast day , clergy would bless and distribute all the candles needed for winter — and over time the focus of the day became increasingly about predicting how long winter would last. As one English folk song put it: "If Candlemas be fair and bright / Come, Winter, have another flight; If Candlemas brings clouds and rain / Go Winter, and come not again."

Germany went a step further by making animals — specifically hedgehogs — part of the proceedings. If a hedgehog saw its shadow, there would be a "second winter" or six more weeks of bad weather, according to German lore.

That was one of several traditions that German settlers in Pennsylvania brought to the U.S., Harman says, along with Christmas trees and the Easter bunny. And because hedgehogs aren't native to the U.S., they turned to groundhogs (which were plentiful in Pennsylvania) instead.

"And the first celebration that we know of was in the 1880s," Harman says. "But the idea of watching animals and whether they see their shadow out of hibernation had been going on before that, it just hadn't turned into a public festival until later in the 19th century."

The "Punxsutawney Groundhog Club" was founded in 1886 by a group of groundhog hunters, one of whom was the editor of the town's newspaper and quickly published a proclamation about its local weather prognosticating groundhog (though Phil didn't get his name until 1961 ). The first Gobbler's Knob ceremony took place the next year, and the rest is history.

The club says Groundhog Day is the same today as when it first started — if the old-timey garb and scrolls are any sign — just with far more participants. That's thanks in large part to the popularity of the eponymous movie and the ability to live-stream the festivities.

And there are more furry forecasters out there too. Many parts of the U.S. and Canada now have their own beloved animal prognosticators, with some of Phil's better-known contemporaries including New York's " Staten Island Chuck " (aka Charles G. Hogg) and Ontario's " Wiarton Willie ."

"Any place that has a groundhog these days is trying to get some [cred] by it," Blumstein says.

It's not only groundhogs that are getting in on the fun. Take, for example: Pisgah Pete , a white squirrel in North Carolina, Connecticut's Scramble the Duck and a beaver at the Oregon Zoo named "Stumpton Fil."

There are things animals can teach us about the climate

There is some scientific basis for the Candlemas lore, according to Blumstein.

He says the thinking was that if there was a high-pressure system in early February, things likely weren't changing and it would probably continue to be cold, while a low-pressure system suggests the potential for better weather ahead. Plus, if it is sunny out, marmots are theoretically big enough to cast a shadow by standing up.

But that alone doesn't make them reliable forecasters.

"Whether or not there is a predictability of whether it's sunny on Groundhog Day and whether spring comes early or later, I don't know," Blumstein says, adding that Phil's predictions involve "him whispering into people who are wearing stovepipe hats and in front of a drunk crowd, so you can't really trust that."

Still, he says there's a lot humans can learn from groundhogs' behavior. He runs a long-term project that is about to begin its 62nd year of studying yellow-bellied marmots in Colorado, as a window into longevity and how flexible animals are in responding to a warming climate.

"Maybe it's a good thing for marmots in that you have a longer growing season, but then every day you're active, you also face some risk of predation," he explains. "And what we're finding is there's sort of an optimal period that you should be active. So there also could be evolutionary responses to this, and what we're really looking at is the evolutionary response to changes over time and the sort of within-generational plasticity, flexibility, if you will."

As part of that research, Blumstein spends time on skis, in the snow, waiting for the yellow-bellied marmots to come out from hibernation.

So he's able to confirm that while Groundhog Day is pegged to Candlemas, it also coincides with the time of year when groundhogs in the northeastern U.S. start to emerge. The males typically come out first and then begin looking for females with whom to mate.

"Groundhog Day is really a holiday about sex," he adds.

Blumstein says all animals, not just the prognosticators, deserve respect. While some people consider groundhogs a nuisance because they like to snack on garden produce, he thinks living with urban and suburban wildlife is a good thing as it brings people closer to nature.

"So I sort of see the ability to, if you're fortunate enough to have a groundhog living in your backyard, to sort of pay attention to it and enjoy it and learn from it and maybe give up some of your tomatoes or apples."

Technology improves, but people still look to Phil

Crowds as large as 30,000 have turned out to Punxsutawney for multi-day Groundhog Day festivities, which the state calls a significant tourism boost for the town of fewer than 6,000 people.

The ceremony itself — which returned to the stage in 2022 after a COVID-19 hiatus — features dancers, music, speeches and visitors from around the world.

"That many nationalities being together all in one place to remember something from the medieval past and from a premodern period, and to bring in the music and to bring in the foods and the culture — it's a real uplifting event," Harman says.