Travel, Tourism & Hospitality

Coronavirus: impact on the tourism industry worldwide - statistics & facts

The impact of covid-19 on global tourism industries, how has the tourism industry changed as a result of covid-19, key insights.

Detailed statistics

Global travel and tourism expenditure 2019-2022, by type

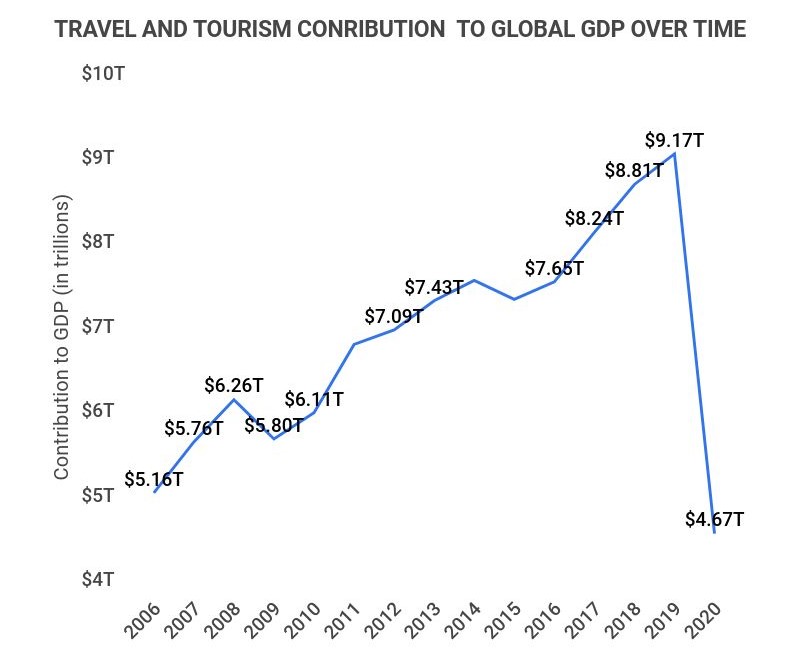

Travel and tourism: share of global GDP 2019-2033

COVID-19: job loss in travel and tourism worldwide 2020-2022, by region

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Current statistics on this topic.

COVID-19: global change in international tourist arrivals 2019-2023

COVID-19: job loss in travel and tourism worldwide 2020-2022, by country

Related topics

Recommended.

- Tourism worldwide

- Coronavirus COVID-19 in China

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) in Italy

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) in South Korea

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the U.S.

Recommended statistics

- Basic Statistic Travel and tourism: share of global GDP 2019-2033

- Basic Statistic Global travel and tourism expenditure 2019-2022, by type

- Premium Statistic Global international tourism receipts 2006-2022

- Basic Statistic COVID-19: job loss in travel and tourism worldwide 2020-2022, by region

- Basic Statistic COVID-19: job loss in travel and tourism worldwide 2020-2022, by country

Share of travel and tourism's total contribution to GDP worldwide in 2019 and 2022, with a forecast for 2023 and 2033

Total travel and tourism spending worldwide from 2019 to 2022, by type (in trillion U.S. dollars)

Global international tourism receipts 2006-2022

International tourism receipts worldwide from 2006 to 2022 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Employment loss in travel and tourism due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic worldwide from 2020 to 2022, by region (in millions)

Number of travel and tourism jobs lost due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in selected countries worldwide from 2020 to 2022 (in million)

International tourist arrivals

- Premium Statistic Number of international tourist arrivals worldwide 1950-2023

- Basic Statistic Number of international tourist arrivals worldwide 2005-2023, by region

- Premium Statistic International tourist arrivals worldwide 2019-2022, by subregion

- Premium Statistic Countries with the highest number of inbound tourist arrivals worldwide 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic Change in international tourist arrivals worldwide 2020-2023, by region

Number of international tourist arrivals worldwide 1950-2023

Number of international tourist arrivals worldwide from 1950 to 2023 (in millions)

Number of international tourist arrivals worldwide 2005-2023, by region

Number of international tourist arrivals worldwide from 2005 to 2023, by region (in millions)

International tourist arrivals worldwide 2019-2022, by subregion

Number of international tourist arrivals worldwide from 2019 to 2022, by subregion (in millions)

Countries with the highest number of inbound tourist arrivals worldwide 2019-2022

Countries with the highest number of international tourist arrivals worldwide from 2019 to 2022 (in millions)

Change in international tourist arrivals worldwide 2020-2023, by region

Percentage change in international tourist arrivals worldwide from 2020 to 2023, by region

Online travel companies

- Premium Statistic Revenue of leading OTAs worldwide 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic Change in revenue of leading OTAs worldwide 2020-2022

- Premium Statistic Total visits to travel and tourism website booking.com worldwide 2021-2024

- Premium Statistic Total visits to travel and tourism website tripadvisor.com worldwide 2020-2024

Revenue of leading OTAs worldwide 2019-2022

Leading online travel agencies (OTAs) worldwide from 2019 to 2022, by revenue (in million U.S. dollars)

Change in revenue of leading OTAs worldwide 2020-2022

Year-over-year percentage change in revenue of leading online travel agencies (OTAs) worldwide from 2020 to 2022

Total visits to travel and tourism website booking.com worldwide 2021-2024

Estimated total number of visits to the travel and tourism website booking.com worldwide from December 2021 to March 2024 (in millions)

Total visits to travel and tourism website tripadvisor.com worldwide 2020-2024

Estimated total number of visits to the travel and tourism website tripadvisor.com worldwide from August 2020 to March 2024 (in millions)

Accommodation

- Premium Statistic Monthly hotel occupancy rates worldwide 2020-2023, by region

- Premium Statistic Monthly change in rental bookings through OTAs due to COVID-19 2020-2022

- Premium Statistic Airbnb nights and experiences booked worldwide 2017-2023

- Premium Statistic Airbnb nights and experiences booked worldwide 2019-2023, by region

Monthly hotel occupancy rates worldwide 2020-2023, by region

Monthly hotel occupancy rates worldwide from 2020 to 2023, by region

Monthly change in rental bookings through OTAs due to COVID-19 2020-2022

Monthly change in short term rental bookings through selected leading online travel agencies (OTAs) worldwide from 2020 to 2022

Airbnb nights and experiences booked worldwide 2017-2023

Nights and experiences booked with Airbnb from 2017 to 2023 (in millions)

Airbnb nights and experiences booked worldwide 2019-2023, by region

Number of nights and experiences booked on Airbnb worldwide from 2019 to 2023 by region (in millions)

Food & drink services

- Premium Statistic Daily year-on-year impact of COVID-19 on global restaurant dining 2020-2022

- Premium Statistic Global quick service restaurant industry market size 2022-2023

- Premium Statistic Restaurant food delivery growth worldwide 2019-2020, by country

- Premium Statistic Online restaurant delivery growth worldwide 2019-2020, by country

Daily year-on-year impact of COVID-19 on global restaurant dining 2020-2022

Year-over-year daily change in seated restaurant diners due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic worldwide from February 24, 2020 to August 1, 2022

Global quick service restaurant industry market size 2022-2023

Market size of the quick service restaurant industry worldwide in 2022 and 2023 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Restaurant food delivery growth worldwide 2019-2020, by country

Restaurant food delivery growth in selected countries worldwide between 2019 and 2020

Online restaurant delivery growth worldwide 2019-2020, by country

Digital restaurant food delivery growth in selected countries worldwide between 2019 and 2020

Virtual tourism

- Premium Statistic Global virtual tourism market value 2021-2027

- Premium Statistic Guests interested in touring hotels using VR/metaverse technology worldwide 2022

- Basic Statistic VR tourist destination prices worldwide 2021

- Premium Statistic Comparison between digital and live exhibitions by visitors worldwide 2021

Global virtual tourism market value 2021-2027

Market size of the virtual tourism industry worldwide in 2021, with a forecast for 2027 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Guests interested in touring hotels using VR/metaverse technology worldwide 2022

Share of travelers that are interested in using a virtual reality/metaverse experience to tour a hotel before booking worldwide as of 2022

VR tourist destination prices worldwide 2021

Price of selected virtual reality travel experiences worldwide as of 2021 (in U.S. dollars)

Comparison between digital and live exhibitions by visitors worldwide 2021

Opinions on virtual versus in-person exhibitions and trade shows according to visitors worldwide as of 2021

Further reports Get the best reports to understand your industry

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

Advertisement

Hospitality Industry 4.0 and Climate Change

- Original Paper

- Published: 23 January 2022

- Volume 2 , pages 1043–1063, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Adel Ben Youssef 1 &

- Adelina Zeqiri 2

17k Accesses

20 Citations

18 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This paper investigates under which conditions implementation of Industry 4.0 in the hospitality sector could help to combat climate change. The paper takes the form of a systematic literature review to examine the main pillars of Industry 4.0 in the hospitality industry and discuss how these technologies could help combat climate change. We propose five conditions under which Industry 4.0 could help to combat climate change. First, in the hospitality industry, increased use of Industry 4.0 technologies induces an increase in energy efficiency and a reduction of GHG. Second, increased use of Industry 4.0 technologies induces a reduction in water consumption and an increase in water use efficiency. Third, increased use of Industry 4.0 technologies induces a reduction in food waste. Fourth, increased use of Industry 4.0 technologies can promote Circular Hospitality 4.0. Fifth, increased use of Industry 4.0 technologies helps to reduce transport and travel. Hospitality Industry 4.0 technologies offer new opportunities for enhancing sustainable development and reducing GHG emissions through the use of environmentally friendly approaches to achieve the Paris Agreement objectives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Toward a Circular Economy in the Copper Mining Industry

Circular Economy in Brazil Coupled with Industry 4.0

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Climate change is considered one of the most serious problems faced by humanity today. Climate change is increasing and is characterized by record-breaking weather events in the form of extreme heavy rainfall, floods, and global temperature shifts with 2010–2019 the hottest decade recorded so far [ 1 ]. According to NASA (2021), the highest temperatures so far were recorded in 2020 despite a large decrease in global emissions due to the COVID-19 crisis. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2021) report warns that in relation to climate change, the “worst is yet to come” and will include extreme heat waves, widespread hunger and drought, rising sea levels, and extinction and that although “Life on Earth can recover from a drastic climate shift by evolving into new species and creating new ecosystems. Humans cannot.”

Climate change is affecting all areas of our lives; land areas are decreasing due to rising sea levels [ 2 , 3 ], agricultural productivity is decreasing [ 3 , 4 , 5 ], and labor productivity and human health [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ] and the tourism and hospitality industries [ 3 , 10 ] are all being affected.

The new technological revolution (Industry 4.0) could help to combat climate change; how successful it will be is debatable. There is a stream of work investigating the extent to which Industry 4.0 can tackle climate change [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ]. However, the findings are inconclusive—some studies find a positive impact of Industry 4.0 on climate change, and others find a negative or no effect.

By definition, the tourism and hospitality industry is diverse and includes restaurants, hotels, casinos, airlines, and tourist attractions [ 16 ]. The hospitality industry includes accommodation [ 17 ], food and beverages [ 18 , 19 , 20 ], and tourism-related services [ 15 ]. “Tourism comprises the activities of persons travelling to and staying in places outside of their usual environment for not more than one consecutive year for leisure, business or other purposes” [ 20 ].

Debate over the relationship between tourism and climate change [ 21 ] has been ongoing for several years. There is a strand of work on the potential effects of climate change on tourism and hospitality and the contribution of tourism to climate change [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. According to Gössling [ 27 ], this sector is considered one of the main contributors to GHG emissions. Tourism contributes hugely to carbon emissions [ 28 , 29 ], which account for 5% of global carbon emissions which are due 75% to transport, 21% to accommodation, and 4% to other tourism activities [ 20 ].

The tourism and hospitality industry is one of the sectors that has been hit hardest by the COVID-19 pandemic. Part of the solution to both climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic is behavioral change [ 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, emissions were reduced and consumers’ behavior changed. Citizens were focused more on ecological and sustainability issues [ 34 ]. According to IEA [ 35 ], the biggest reduction in emissions was seen in the transport sector. Emissions from oil used for transport accounted for over 50% of the overall decrease in emissions in 2020. The restrictions imposed to reduce the spread of the virus resulted in about a 14% drop in the emissions from this sector compared to 2019, with the hardest hit being aviation where in 2020 emissions almost halved and fell to 1999 levels.

Another strand of work examines the links between the hospitality industry and Industry 4.0 [ 36 , 36 , 38 ], [ 39 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 43 ]. Most of these studies focus on reshaping the hospitality industry as a result of implementing Industry 4.0 technologies and providing personalized experiences and digitalized services. However, work on the direct link between Industry 4.0 and environmental and climate change issues in the hospitality sector is not well developed. A few studies [ 44 , 45 ] investigate environmentally friendly practices in the hospitality industry.

The aim of this paper is to investigate under what conditions implementation of Industry 4.0 in the hospitality sector could help to combat climate change. First , it examines the main pillars of Industry 4.0 in the hospitality industry and discusses how it is reshaping the sector. We consider cyber physical systems (CPS), the Internet of Things (IoT), virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), big data, artificial intelligence (AI), and robotics. Second , we explore the relationship between the hospitality industry and climate change by discussing the effects of climate change on tourism and the contribution of tourism to climate change. We consider adaptation and mitigation strategies to fight climate change. Third , we propose five conditions under which Industry 4.0 could help to combat climate change. Hospitality Industry 4.0 enables, first , increased energy efficiency, second , increased water use efficiency, third , reduced food waste, fourth , “circular hospitality,” and fifth , replacement of transport and travel by VR.

Research objectives include (1) a comprehensive literature review of hospitality Industry 4.0 and climate change, (2) five conditions under which Industry 4.0 could help to fight climate change, and (3) formulation of a future hospitality Industry 4.0 and climate change research agenda. We address the following research questions:

How can Industry 4.0 induce an increase in energy efficiency and a reduction in GHG emissions in the hospitality industry?

Can Industry 4.0 lead to reduced consumption of and more efficient use of water?

How can Industry 4.0 help to reduce food waste?

Can Industry 4.0 promote Circular Hospitality 4.0?

Will Industry 4.0 result in reduced transport and travel?

The paper is organized as follows: the “ Methodology ” section discusses the methodology, the “ Theoretical Background: Main Definitions and Concepts ” section provides the main concepts of hospitality Industry 4.0 and examines the relationship between climate change and tourism, the “ How Hospitality Industry 4.0 Could Help to Combat Climate Change: Five Proposed Conditions and the Future Research Agenda ” section shows how hospitality Industry 4.0 could contribute to reducing climate change, and the “ Concluding Remarks and Policy Implication ” section offers some conclusions and policy implications.

Methodology

The paper is based on a systematic literature review which enables five propositions for how Industry 4.0 could help to combat climate change. A literature review allows more choices compared to an empirical study. A literature review allows the researcher to address broader questions, and by the ability to focus on patterns and connections among many empirical findings, a literature review can address theoretical questions that are beyond the scope of a single empirical study. While empirical studies allow single conclusions, a literature review allows several [ 46 ].

The objective of a systematic review is to formulate a well-defined question and provide a quantitative and qualitative analysis of the relevant evidence, followed (or not) by a meta-analysis [ 47 ]. The strengths of a systematic literature review are that they allow a focus on a unique query, retrieval of articles for review, objective and quantitative summaries, and inferences based on evidence [ 48 ]. However, a literature review also has some limitations such as the heterogeneity in the studies selected, possible bias from single studies, and possible publication bias [ 49 ]

The literature on hospitality Industry 4.0 and climate change is very heterogeneous. We have tried to identify the most relevant studies and those most likely to avoid biased findings. We searched the literature using the keywords “climate change,” “hospitality,” “tourism,” “Industry 4.0,” “energy efficiency in hospitality,” “circular hospitality 4.0,” “water in hospitality,” “food waste in hospitality,” “travel and transport,” “Industry 4.0 technologies,” and “virtual tourism.”

The corpus of literature was based on the snowballing technique, i.e., identifying additional papers based on the papers identified—which is especially useful if identification of relevant publications is difficult. We used the reference lists in the initial (more than 2 papers) identified to identify other papers on the topic. As our search progressed, we refined the list of keywords. We identified a range of journal articles from different fields.

Wohlin [ 50 ] states that snowballing can be particularly useful for systematic literature reviews:

In particular, it should be noted that snowballing is particularly useful for extending a systematic literature study, since new studies almost certainly must cite at least one paper among the previously relevant studies or the systematic study already conducted in the area. Thus, snowballing is by deduction a better approach than a database search for extending systematic literature studies. The actual evidence for this assertion is left for further research.

Theoretical Background: Main Definitions and Concepts

What is hospitality industry 4.0.

Rapid technological developments and innovation result in paradigm shifts [ 51 ]. The most recent is the 4th industrial revolution which like previous industrial revolutions is characterized by its effects on industry. The first industrial revolution involved mechanization and the introduction of steam and water power,the second industrial revolution saw the introduction of mass production and assembly lines based on electrical power; the third industrial revolution involved automation of production and computers. The fourth industrial revolution is characterized by CPS and interconnection between the virtual and physical worlds. Frank et al. ([ 52 ], p. 343) define Industry 4.0 “as a new industrial maturity stage of product firms, based on the connectivity provided by the industrial Internet of things, where the companies’ products and process are interconnected and integrated to achieve higher value for both customers and the companies’ internal processes.”

The fourth industrial revolution is making it hard for humankind to distinguish between what is artificial and what is natural [ 53 ]. Industry 4.0 is affecting almost every sector of the economy, including the hospitality industry. Hospitality 4.0 is one of many sub-concepts (e.g., Tourism 4.0,Hospitality 4.0; Medicine 4.0, Agriculture 4.0, Travel 4.0, Energy 4.0) under the broader Industry 4.0 umbrella [ 53 , 54 ]. The aim of Hospitality 4.0 is to create more personalized and digitalized services for consumers and resolve problems related to massification, individual experiences, and sustainability. In this context, Tourism 4.0 allows a richer tourist experience [ 55 ].

Smart hospitality is envisaged as an interoperable and interconnected system enabling information sharing which will provide added value for the entire ecosystem of stakeholders via digital platforms [ 56 , 57 ]. Smart hospitality will allow information exchanges along the value chain and will put customers at the center of the process through the provision of personalized and contextualized services and experiences [ 57 ]. The new technologies have changed consumer behavior in terms of use of hospitality services [ 15 , 58 , 59 ]. Digitalization is allowing consumers to engage in various activities. Consumers are requiring more than basic facilities, and hospitality must change to satisfy their expectations.

The world has seen a massive increase in environmental pollution since the second industrial revolution. While existing studies link Industry 4.0 technologies to environmental management and climate change, the lack of a strong focus and positive actions are calling for better technological solutions to saving the environment and increasing sustainability, e.g., Industry 5.0. The concept of Hospitality 5.0 has already been advanced [ 60 ]. While Industry 4.0 is concerned mainly with automation, Industry 5.0 will focus on synergies between humans and autonomous machines [ 61 ].

Hospitality 4.0 Technologies

The fourth industrial revolution includes a set of technological developments such as CPS, the IoT, AR, VR, AI, robotics, big data, blockchain, and 3D printing. There is stream of work which examines the links between the hospitality industry and the various pillars of Industry 4.0 such as the IoT [ 36 , 43 , 62 , 63 ], VR [ 37 , 38 , 64 , 62 , 63 , 67 ], AR [ 37 , 40 , 68 ], big data [ 42 , 43 ], and AI and robotics [ 39 , 41 ]. Industry 4.0 technologies can be interconnected using horizontal, vertical, and end-to-end system integration tools along the value chain [ 11 ].

CPS are the main pillar of Industry 4.0. They are defined as integrated and interconnected physical and virtual arrangements based on computation, communication, and control systems [ 69 ]. Sensors, 3D scanners, cameras, and radio frequency identification (RFID) devices are used by CPS to collect data [ 70 ]. Embedded CPS enable the exchange of data in smart networks [ 71 ]. The IoT is based on the interconnection between CPS and the Internet [ 72 ]. According to Lee et al. [ 69 ], CPS involve interconnection of the physical and cyber worlds which enables access to real-time data and smart data management, analytics, and computational capability. CPS allow autonomous and decentralized production processes [ 73 ].

The IoT involves interconnectivity among physical devices such as sensors, actuators, RFID tags, laptops, and mobile phones, and their communication through networks or the Internet which enable integration of the physical and cyber worlds [ 74 ]. RFID enable the identification of objects or humans,wireless sensor networks can sense the environment and process data through large numbers of nodes which enable communication and computation; smart technology can transform objects into smart objects able to communicate with users in active or passive ways; and nanotechnology allows interconnection of nanoscale objects [ 75 ]. The IoT includes smart vehicles and smart homes to enable integration of services such as notifications, security, energy saving, automation, communication, computing, and entertainment [ 76 ]. In the context of the hospitality industry, the emergence of IoT technology is transforming hotels into smart hotels within smart cities [ 77 ]. Application of the IoT in the hospitality sector allows interactions with tourists and collection of real-time tourist data. It allows instant, personalized, and localized services and accurate evaluation of tourist behaviors and preferences [ 62 ].

Another pillar of Hospitality 4.0 is AR which involves the combination of real and virtual objects in a real environment, synchronization of real and virtual objects, and interaction in 3D and in real time [ 78 ]. There are several types of AR technologies [ 37 ]: marker-based AR enables the scanning of physical images through a camera and visual markers which can be sensed by readers; markerless AR or GPS-based AR provide data on precise location; projection-based AR allows projection of artificial light on the surface of the real world; and superimposition-based AR enables partial or complete replacement of the original object view by an augmented view. In recent years, AR has provided opportunities for hospitality businesses and tourists. It provides tourists with more personalized services and additional benefits such as navigation of selected locations and allows tourists to share and exchange information and opinions with other tourists in large networks [ 68 ].

While AR augments elements in the real environment, VR simulates reality [ 79 ]. According to Rajesh Desai et al. ([ 80 ], p. 175), VR is “a computer simulated (3D) environment that gives the user the experience of being present in that environment.” It provides people with opportunities for virtual travel [ 81 ]. It contributes to sustainable tourism by providing the opportunity for low cost and environmentally friendly travel [ 38 ]. VR allows people to visit difficult to access places, to travel across time, and to enter fantasy worlds [ 82 ] and allows people of all ages and those with reduced mobility to enjoy tourism and participate in online communities [ 38 ].

Big data analytics are related to recent technological developments which have increased the amount of data generated making traditional techniques insufficient to cope with their processing and analysis. The hospitality industry captures and generates huge volumes of data on consumer preferences and characteristics. In the hospitality sector, big data includes internal big data which are held in central databases and external big data which are collected from the Internet via sensors. Data can be classified based on their characteristics and type, and hospitality ecosystem actors can access and use these data to prepare strategic business plans and manage their operations in a dynamic way [ 57 ]. The hospitality industry needs to understand tourist preferences, behaviors, and locations in order to offer personalized services. This involves the collection, storage, and use of data in appropriate ways and their protection from threats. Computing resources help to enhance the security and interconnectivity of tourist networks with the hospitality industry [ 62 ]. However, secure data storage is a major problem.

AI and robots are used in the hospitality sector to create more personalized and unique experiences at low cost. Service robots in workplaces maintain contact with people in a shared non-industrial environment [ 83 ]. Robots can replace humans in R&D activities [ 84 ]. Robots are being used by airport management to substitute for traveler information centers and allow services that do not require human interaction. Hotels use robots to support both their employees and their consumers [ 39 ]. Continued development of advanced technology will make AI and intelligent robots more affordable and faster and more reliable than humans.

Tourism and Climate Change: Twofold Relationship

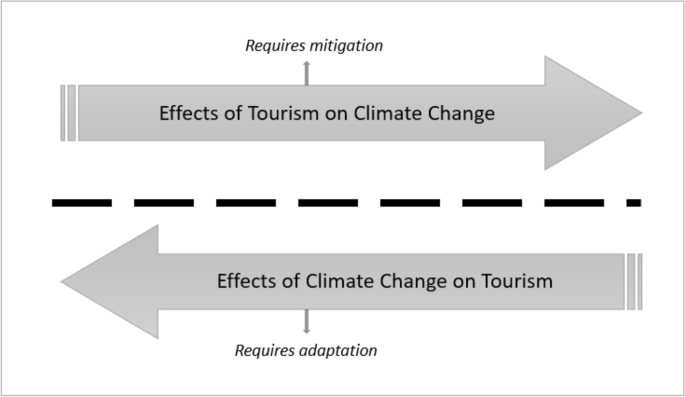

The relationship between climate change and tourism has been the topic of debate for many years (Fig. 1 ). The first international climate change conference in the context of tourism was held in 2003 in Djerba, Tunisia [ 85 ] when the importance of the tourism industry to the global economy and its vulnerability to the impacts of climate change were emphasized. It was agreed that there was a need to develop sustainable policies and reduce GHG emissions [ 85 ]. In 2007, the second International Conference on Climate Change and Tourism was held in Davos, Switzerland, and discussion on climate change and tourism continued in the framework of the United Nations Environment Programme, the World Meteorological Organization, and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), at the UN Climate Change summit in Bali. The conference theme “Tourism: responding to the challenge of climate change” was the centerpiece of the 2008 World Tourism Day [ 20 ]. UNWTO et al. ([ 20 ], p. 13) suggest that “climate is a key resource for tourism and the sector is highly sensitive to the impacts of climate change and global warming, many elements of which are already being felt.” Debate on the importance of climate change was reignited by the definition of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). SDG 13 was aimed at combating climate change [ 86 ] and led to the Paris Agreement on Climate Change [ 87 ]. In 2018, the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) and the UNFCCC agreed a common agenda for climate action related to travel and tourism to tackle climate change.

Two-way relationship between tourism and climate change. Source: Patterson, Bastianoni and Simpson [ 96 ]

Debate continues on the relationship between tourism and climate change [ 21 ] and its complexity [ 22 ]: tourism affects climate change and climate change affects tourism [ 24 ]. On the one hand, tourism and its associated activities contribute to climate change [ 88 ]. Tourism contributes to GHG emissions through transport, accommodation [ 89 ], food production and consumption [ 90 ], and other activities. In the case of transport, the largest contributor to carbon emissions is air travel, followed by car transport [ 89 ]. On the other hand, tourism is affected by climate change in the form of heat waves and rising sea levels. Other impacts include changes to arctic temperatures and ice, precipitation amounts, ocean salinity, and wind patterns, and more frequent occurrence of extreme weather events such as droughts and tropical cyclones [ 91 ]. These aspects affect coastlines and cause beach erosion, water shortages, forest fires, desertification, extinction of wildlife, and damage to heritage sites [ 90 ]. Furthermore, Hall et al. ([ 92 ], p. 2) suggest that climate change “is extremely significant for tourism because of its influences on the economic viability of tourism destinations and activities, tourist behavior, and its ramifications for the entire tourism system.” According to IPCC [ 93 ], tourism is already being affected by global warming, with increased risks of an additional 1.5 °C of warming in specific geographic regions which will affect beach and snow sports destinations. The link between tourism and climate is important for people planning holidays and other leisure travel. According to Zanni et al. [ 94 ], considerable numbers of people have changed their travel plans due to weather-related disruptions. The weather affects destination choices and tourist satisfaction [ 95 ].

Adaptation and Mitigation Strategies

There are two important climate change strategies in the tourism industry: adaptation and mitigation [ 20 , 96 ]. According to the findings of the 5th IPCC Assessment Report (AR5), summarized by Scott, Hall, and Gössling ([ 97 ], p. 15), it is suggested that “all tourism destinations will need to adapt to climate change, whether to minimize risks or to capitalize on new opportunities.” Adaptation involves means to moderate or curb the impact of climate change by institutions, governments, individuals, and corporations [ 24 ]. Adaptation efforts in the tourism sector differ across sectors, activities, and destinations. They include protection of coastlines and provision of artificial snow to allow continued tourism to ski resorts experiencing less snowfall during the skiing season [ 26 , 98 ]. The strategies employed depend on different social, economic, and environmental conditions [ 99 ].

Climate change mitigation includes efforts to reduce the effects of tourism [ 24 ] which can be achieved via use of Industry 4.0 technologies. Below, we discuss in more detail five proposed ways that Industry 4.0 technologies could allow the hospitality industry to reduce its carbon footprint.

How Hospitality Industry 4.0 Could Help to Combat Climate Change: Five Proposed Conditions and the Future Research Agenda

Ben Youssef [ 11 ] proposes four ways that Industry 4.0 could help combat climate change by promoting energy efficiency and achieving substantial energy gains, enabling the circular economy, achieving sustainable development through eco-innovation, and allowing significant technology transfer to the least developed countries (LDCs). The application of Industry 4.0 to combat climate change requires consideration of three main issues [ 11 ]: first, cloud computing providers need to shift to renewable energies and use less fossil fuel energy,second, economic and societal transformations will be needed to enable massive adoption of Industry 4.0; third, Industry 4.0 will require governance and agreements about ethical considerations.

We propose five conditions under which Industry 4.0 could help to combat climate change: first, increased use of Industry 4.0 technologies to induce increased energy efficiency and reduction of GHG from the hospitality industry; second, increased use of Industry 4.0 technologies to induce a reduction in water consumption and an increase in water use efficiency; third, increased use of Industry 4.0 technologies to induce a reduction in food waste; fourth, increased use of Industry 4.0 technologies in the hospitality industry to promote circular Hospitality 4.0; and fifth, increased use of Industry 4.0 technologies to reduce transport and travel. The motivation of the choice of these propositions comes from the literature review. The previous work treats these issues as separate topics; we suggest that they are crucial for reducing the carbon footprint of the hospitality industry.

Proposition 1: Increased Use of Industry 4.0 Technologies to Increase Energy Efficiency and Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Several studies [ 100 , 98 , 102 ] show that buildings consume 40% of the world’s energy which accounts for 30% of CO2 emissions. There should be an emphasis on green incentives, green programs, and modern heating, cooling, and water systems using digital technologies to record and report green efforts and use energy more efficiently to reduce carbon emissions. On average, some 30% of energy savings could be achieved through implementation of intelligent automation technologies in buildings [ 102 ]. According to Harish and Kumar [ 103 ], new buildings could achieve energy savings of between 20 and 50% through the incorporation of appropriate building, heating, ventilation, air conditioning (HVAC, 20–60%), lighting (20–50%), water heating (20–70%), refrigeration (20–70%), and electronics and other designs (10–20%).

New technologies could provide hotel staff with critical data and send alerts to help them manage energy consumption and increase sustainability. The IoT could contribute to more efficient energy use in the hospitality sector. The hospitality industry is making efforts to offer more personalized services and unique experiences while also trying to respond to calls for more sustainable travel. A sustainable travel report from Booking.com (2018) found that 87% of global travelers are keen to find ways of more sustainable travel.

The IoT will allow more efficient energy use based on smart devices and energy-saving systems. According to Eskerod et al. [ 44 ], the use of smart energy management systems could reduce hotel energy costs by between 20 and 25%. Many hotels are employing smart lighting, temperature control equipment, and devices such as compact fluorescent bulbs and LED lights to reduce energy use [ 62 ]. Use of heating and cooling technologies is temperature dependent,higher temperatures increase use of air conditioners and call for more efficient air conditioning technologies [ 104 ].

Smart HVAC systems would optimize energy consumption in particular for lighting. Use of sensors to monitor HVAC systems saves time and reduces maintenance requirements. A control center can provide information related to lighting including energy consumption per light fixture [ 44 ]. Industry 4.0 technologies enable automatic adjustment to room temperatures and automatic switching off of lights and TVs when guests leave their rooms.

As Industry 4.0 technologies become more ubiquitous, they are being employed in more places and for different purposes. Reducing energy consumption requires both implementation of these new technologies and training in how to use them to increase sustainability. Industry 4.0 technologies to increase energy efficiency will become imperative for hospitality businesses in the future. Cybersecurity, reliability, and workforce skills must be considered in the adoption of these technologies to increase energy efficiency.

While technology enables substantial improvements in terms of energy savings and energy efficiency, tourist behavior also matters and the possible “rebound effect” when improvements to energy efficiency do not translate into less demand for energy must also be considered [ 105 ]. The improvements enabled by technology can be reduced by the attitudes and behavior of tourists. However, we would suggest that the potential improvements enabled by technology will be greater than the potential negative effects of tourist behavior.

Proposition 2: Increased Use of Industry 4.0 Technologies to Reduce Water Consumption and Increase Water Use Efficiency

Water consumption is a major item in the hotel and accommodation sector and contributes significantly to carbon emissions. Tourist activities increase the sector’s carbon footprint and affect water resources. It is estimated that water consumption per tourist per day ranges between 84 and 2,000 l, or up to 3,423 l per room per day [ 106 ]. According to [ 107 ], showering is the biggest consumer of water,in apartments, hotels, and houses, around 25% of total monthly water consumption is due to showering. During the winter when temperatures are low, there is a dramatic increase in consumption of hot water [ 107 ]. Huge volumes of water are consumed by laundries which accounts for approximately 35% of their total energy consumption, 65% of which is related to drying and finishing.

Hotels are implementing innovative water-saving devices which allow collection and use of rainwater, separation of “gray” water for composting toilets, and water recycling. Hotel guests should be encouraged to reuse towels, and baths should be replaced by showers [ 108 ]. The IoT is offering new perspectives on smart buildings and more efficient use of resources [ 107 ]. IoT-enabled water meters can be used to monitor water use at low cost. Use of smart bathrooms equipped with smart showers, smart sinks, flow-controlled toilets, etc. helps to reduce water consumption in hotels,smart showers would result in more efficient use of water. A recycling shower developed by OrbSys saves 90% on water consumption and 80% on energy compared to a regular shower.

There are several examples of the benefits deriving from Industry 4.0 in terms of water use efficiency in the hospitality industry. Prasad et al. [ 109 ] propose a smart water quality monitoring system using the IoT and remote sensing technology to ensure water quality and provide real-time water monitoring. Saseendran and Nithya [ 110 ] describe an automated water usage monitoring system which uses the IoT to control domestic and industry water use and water waste via wireless sensor nodes. Ahemed and Amjad [ 111 ] discuss a water management system (WMS) which monitors water storage tanks and takes action if water levels become too high or too low. Pereira-Doel et al. [ 112 ] study a hotel in Spain that has smart technology installed in 20 individual rooms. Their findings indicate that real-time feedback induced 12.06% reduced guest shower times on average, equivalent to 40.91 s and 6.14 l of water.

However, water savings depend also on tourist behavior. Raising awareness about the fragility of our environment and the importance of protecting it is vital. Prompts in the areas most exposed to tourism remind tourists of the importance of careful use of water.

We would suggest that the potential offered by new technology is enough to overcome any rebound effects. As Industry 4.0 technologies evolve, their optimization will enable better environmental performance and better adaptation to water scarcity and water availability for the hospitality industry.

Proposition 3: Increased Use of Industry 4.0 Technologies to Reduce Food Waste

About 1.3 billion tonnes of food is wasted annually [ 113 ], and that waste food is responsible for about 8% of global GHG emissions [ 114 ]. How much food is wasted in the hospitality industry is debatable. In the UK, it is estimated that, annually, 920,000 tonnes of food is wasted at outlets, 75% of which is avoidable waste of still edible food [ 115 ]. In Sri Lanka, it is estimated that 79% of total hotel waste is food waste [ 116 ]. Large amounts of food are wasted every day, and much of it could be used to feed the world’s hungry people. Action is needed to reduce and prevent food waste.

Recent digital innovations could help reduce food waste in the hospitality sector by allowing more accurate forecasting of demand and supply. AI and big data, smartphones, and apps Footnote 1 can help to reduce food waste from kitchens. AI devices send notifications about the cost of the food being thrown away and record daily waste. This kind of information helps hotels, restaurants, etc. to reduce food waste and to better understand consumer preferences. Food waste includes the water, energy, and other resources used in its preparation; therefore, reducing food waste reduces both costs and environmental footprint.

Wen et al. [ 117 ] discuss an IoT-based food waste management system for restaurants, developed and implemented in Suzhou, China. It consists of RFID and sensor systems which provide real-time data on food waste to the catering companies involved, and a smart food waste collection truck equipped with RFID readers. Implementation of the system has had positive effects and resulted in better management of food waste across the value chain. Hong et al. [ 118 ] proposed an IoT-based smart garbage system which collects and analyzes information on food waste. The system was implemented as a 1-year pilot project in Seoul’s Gangnam district, and the results show average food waste reductions of 33%.

Based on the examples in the literature, we propose that Industry 4.0 technologies could reduce food waste. Most food waste ends up in landfill and increases GHG emissions. We need to collect data and information along the entire food chain. This information can be used to adapt future buying decisions, menus, food preparation techniques, and consumer preferences. Offering different portion sizes on online menus would allow consumers to choose the right sized portions which would avoid food waste.

However, application of Industry 4.0 technologies to reduce food waste can be difficult to implement in all hospitality businesses. Very small businesses may consider the investment required to be overly expensive and may decide not to invest. Large hospitality businesses may be unaware of the benefits to be derived from the use of these technologies. In addition to reducing food waste and pollution, Industry 4.0 technologies help to reduce the time and monetary costs involved in managing the necessary human resources.

Proposition 4: Increased Use of Industry 4.0 Technologies to Promote Circular Hospitality 4.0

The linear economy should be transformed into a circular economy to allow reuse and recirculation of resources. Larsson ([ 119 ], p. 12) defines the circular economy as “an economic system where production and distribution are organized to use and re-use the same resources over and over again”. It should be considered a new way of consumption linked to the move to a low carbon economy. According to Preston ([ 120 ], p.3), the circular economy “involves remodeling industrial systems along lines of ecosystems, recognizing the efficiency of resource cycling in the natural environment” and relies on three main principles [ 121 ]: maintaining and boosting natural resources through use of renewable rather than fossil fuel energy and use of other sustainable methods, optimizing resources efficiency by circulating products, components, and materials, and strengthening system effectiveness.

Application of circular economy principles in hospitality could result in more sustainable hospitality and tourism. Sustainability has for long focused mainly on energy use, water use, and recycling. The circular economy would promote sustainable tourism and travel, and water and energy savings, by replacing non-renewable resources with renewable resources which would help to reduce carbon emissions, and waste, and introduce zero km menus in restaurants [ 122 ]. According to Manniche et al. [ 123 ], circular hospitality includes building and construction, refurbishing and redecorating, operational services, practices related to accommodating managers and staff, and interactions with guests.

The more complex issues are those related to governance and behavior. Circular Hospitality 4.0 will contribute to making the hospitality industry more sustainable. Implementation of technologies in the hospitality industry will result in more efficient use of the resources which would contribute directly to sustainability.

However, the application of eco-innovation practices in hotels is not enough to achieve a circular business. Circularity must include the host–guest relationship. Hotels must involve their consumers in related environmental issues and actions. Consumers must be trained in more efficient use of resources and receive information to allow them to reduce their travel and tourism ecological footprint.

Proposition 5: Increased Use of Industry 4.0 Technologies to Reduce Transport and Travel

Tourism accounts for 5% of global carbon emissions [ 25 ]. The biggest contributor to carbon emissions from the tourism sub-sector is transport which accounts for 75% of carbon emissions in this sector [ 20 ]. Air travel is the main source of carbon emissions accounting for 40% of this 75% [ 124 ].

Reducing GHG emissions from travel and transport will require use of recent technological developments. The implementation of environmentally friendly tourism is needed to enable continuous improvements to the quality of the natural environment [ 125 ]. Increased use of Industry 4.0 technologies could result in less travel and transport. In this context, it has been suggested that VR could substitute for actual travel [ 82 , 126 ] and would contribute significantly to sustainability [ 127 ] by providing low cost and environmentally friendly ways of “traveling” [ 38 ]. Drones could be used to enable virtual tourism,video cameras attached to drones could record and capture pictures and aerial views of historical and natural sites in an environmentally friendly way [ 128 ].

The lockdowns imposed by many countries in 2020 to try to stem the spread of the COVID-19 virus have provided a unique setting to explore whether and to what extent virtual tourism can substitute for physical tourism. The collapse of tourism activities due to the COVID-19 pandemic increased interest in virtual tourism activities which can be expected to increase in the future (Ben [ 34 ].

The opportunity for virtual visits to various tourism destinations such as museums, castles, galleries, and exhibitions increased interest in shifting from physical tourism to virtual tourism during this period. Popular destinations are focusing on virtual experiences enabling people to visit various attractions worldwide from their homes. Tourism businesses will need to invest in technology since Industry 4.0 technologies will continue to be in demand even after the pandemic. The implementation of Hospitality 4.0 technologies would solve the problem of mass tourism and reduce degradation and overcrowding of heritage sites. They would contribute also to sustainability since Industry 4.0 technologies aim to be environmentally friendly.

This effect is not one-sided; Industry 4.0 will have an impact on tourism jobs, and the growth of VR and the reduction in physical travel will have negative social and economic impacts on reducing income and employment at destinations, especially in the global South. In these areas, operations respond to demand from the global North. Existing workforces will require retraining.

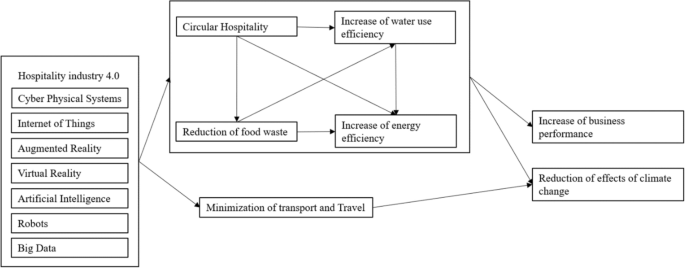

Proposed Research Agenda

Based on the literature review and the five propositions identified above to combat climate change, we propose a future research model (Fig. 2 ). Our choice of the model variables is based on previous evidence. We reviewed several works to identify the most important variables. We conducted a quantitative analysis to validate the proposed model and enable its application to different countries.

Proposed model

The first part of the model includes applications of Industry 4.0 technologies in the hospitality sector—CPS, the IoT, AR, VR, AI, robots, and big data. These technologies have been shown to have the potential to combat climate change in the hospitality sector. Industry 4.0 and climate change have several commonalities. They are systematic and complex and affect society. Since the technologies have the potential to increase energy and water use efficiency, reduce food waste, enable a circular model, and minimize travel and transport, we can assume that they will have a significant impact on efficient use of resources such as energy, water, food, and transport in the hospitality sector.

The second part of the model shows that energy efficiency, water use efficiency, food waste reduction, and circularity are linked. First , implementation of circular Hospitality 4.0 will have a significant effect on increasing energy and water use efficiency and reducing food waste. Circular hospitality will also reduce costs. Application of the new technologies is making it possible to reuse and recycle resources, which reduces waste and costs and increases efficiency. At the same time, Industry 4.0 technologies help to reduce carbon emissions and are less damaging to the environment. Second , reducing food waste will increase energy efficiency and water use. Food, energy, and water are linked, and the more food that is produced and prepared, the more energy and water is consumed. Use of technologies to reduce food waste would increase water and energy efficiency. Third , more efficient water use will have a significant influence on increasing energy efficiency.

Finally, all of these aspects will enhance business performance. The potential of Industry 4.0 technologies goes beyond combating climate change and enhances business performance by reducing energy, water, and food waste costs. In addition to circular Hospitality 4.0 and reduced travel and transport, this will reduce GHG emissions hugely.

Concluding Remarks and Policy Implication

This paper has examined the use of Industry 4.0 technologies in the hospitality sector to reduce climate change. While both adaptation and mitigation strategies are crucial, we focused on mitigation of climate change. We proposed a model for the potential effects of Industry 4.0 technologies in the hospitality sector aimed at reducing climate change.

We have shown the potential of these technologies in the hospitality industry to increase sustainability. The five applications focused on show that Industry 4.0 could have major implications for efficiency increases and a reduced carbon footprint. Integration of CPS, the IoT, AR, VR, AI, robotics, and big data in the hospitality sector would allow customized services for consumers and reduce costs. Implementation of Hospitality 4.0 technologies will enable increased energy efficiency, more efficient use of water resources, reduced food waste, circular Hospitality 4.0, and reduced travel and transport which currently contribute hugely to carbon emissions from the hospitality sector.

Ben Youssef [ 11 ] identifies three limitations to use of Industry 4.0 technologies. First, the world’s data centers emit as much CO2 as the global aviation industry and should focus on more use of renewable energies and less use of fossil energy. Second, the social effect of Industry 4.0 applications is not clear, and especially in a context of high unemployment. Industry 4.0 could cause significant economic and social transformations which need to be taken into account. Third, Industry 4.0 technologies require good governance to ensure they benefit everyone and contribute to inclusive and sustainable societies.

Main Contributions

The paper makes three main contributions.

First , it contributes to debate on the application of Industry 4.0 technologies in the hospitality industry and how these technologies are reshaping the sector. The literature examines the impact of different Industry 4.0 technologies in the hospitality industry, but the results are inconclusive. Some studies discuss how these technologies are disrupting the hospitality sector, and others explore their potential to combat climate change and reduce GHG emissions. Our paper contributes by analyzing how the application of these technologies in the hospitality industry could result in increased efficiency of use of resources and adoption of environmentally friendly practices.

Second , it suggests that Industry 4.0 could help combat climate change in the hospitality sector through increased energy efficiency, increased water use efficiency, reduced food waste, circular hospitality, and use of VR instead of actual transport and travel. These five conditions could be important mechanisms to increase the efficiency of the hospitality businesses and reduce its carbon footprint. These findings should be useful for stakeholders and policymakers in the hospitality industry.

Third, the paper contributes by proposing a future research agenda and directions for further quantitative research. The proposed model could be employed in future research.

Policy Implications

Industry 4.0 offers a sustainable solution for the hospitality industry with appropriate implementation of technologies. Given the potential of these technologies to mitigate climate change, we need policies to foster their adoption by the hospitality industry.

First , a set of technologies needs to be implemented; interconnected and interoperable technological systems will increase business opportunities and environmental performance. Their adoption must be part of a systemic change and deep organizational change in the hospitality industry.

Second , the hospitality ecosystem must be designed as a smart system which includes all stakeholders to provide added value along the entire chain. Current business models must be redesigned, and the business as usual model must be replaced by smart, sustainable, and environmentally friendly business models.

Third , policymakers must implement innovative energy and water efficiency policies and programs for the hospitality industry to reduce energy use. Renewable energies, smart grids, and other energy efficiency solutions should be introduced. Smart meters to increase water efficiency must be used in all parts of the hospitality sector to increase efficiency and reduce costs and carbon footprint.

Fourth , Circular Economy 4.0 should be at the heart of hospitality industry policy. Promotion of a circular economy in the hospitality industry would improve the use of resources, reduce transport of goods, and reduce waste and pollution.

Fifth , workforces should be retrained to meet the organizational changes which will follow application of Hospitality 4.0. Workers will need appropriate digital skills and training in how to fight climate change.

Limitations and Future Research

The paper has the following limitations.

First , it is based on a systematic literature review. Quantitative methods and surveys of hospitality businesses would provide more information on perceptions of Industry 4.0 technologies to combat climate change.

Second , the paper focuses mainly on the benefits of Industry 4.0 technologies in relation to combating climate change. Future research could consider the negative effects of the application of these technologies.

Third , we proposed five conditions allowing Industry 4.0 technologies to combat climate change. Future research could consider other factors, determinants, and strategies related to combating climate change and reducing the carbon emission from the hospitality sector.

Fourth , our future research agenda has not been validated. The proposed model requires the development of appropriate measures. The present study should be considered a preliminary qualitative exploration of the role of Industry 4.0 in the hospitality sector in relation to climate change. We plan to conduct quantitative analysis to validate our proposed model and apply it to different countries to allow its components to be analyzed in more depth.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

“Wise Up on Waste” was developed by Unilever Food Solutions to allow kitchen professionals to measure, monitor, and manage food waste and reduce costs. “Karma” # is an app which helps restaurants and cafes to reduce food waste by enabling them to sell what would otherwise be unsold food, at reduced prices. Consumers can order via the app and buy the food as a takeaway item. This reduces food waste in restaurants and allows consumers to buy food at reduced prices. Winnow Solution # has developed a smart tool involving a touchscreen which allows staff to identify what is being thrown away and when.

Conway D, Vincent K (Eds) (2021) Climate risk in Africa: adaptation and resilience. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan

IPCC (2014) Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York

Google Scholar

Roson R, Van der Mensbrugghe D (2012) Climate change and economic growth: impacts and interactions. Int J Sustain Econ 4:270–285. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSE.2012.047933

Article Google Scholar

Boonwichai S, Shrestha S, Babel MS, Weesakul S, Datta A (2018) Climate change impacts on irrigation water requirement, crop water productivity and rice yield in the Songkhram River Basin, Thailand. J Clean Prod 198:1157–1164. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2018.07.146

Cline WR (2008) Global warming and agriculture. Financial Development. March, 23–27

Kjellstrom T, Holmer I, Lemke B (2009) Workplace heat stress, health and productivity—an increasing challenge for low and middle-income countries during climate change. Glob Health Action 2:2047. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v2i0.2047

Kjellstrom T, Kovats RS, Lloyd SJ, Holt T, Tol RSJ (2009) The direct impact of climate change on regional labor productivity. Arch Environ Occup Health 64:217–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/19338240903352776

Leal Filho W, Bonecke J, Speilmann H, Azeiteiro UM, Alves F, Lopes de Carvalho M, Nagy GJ (2018) Climate change and health: an analysis of causal relations on the spread of vector-borne diseases in Brazil. J Clean Prod 177:589–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2017.12.144

Tawatsupa B, Yiengprugsawan V, Kjellstrom T, Berecki-Gisolf J, Seubsman S-A, Sleigh A (2013) Association between heat stress and occupational injury among Thai workers: findings of the Thai cohort study. Ind Health 51:34–46. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2012-0138

Hamilton JM, Maddison DJ, Tol RSJ (2005) Climate change and international tourism: a simulation study. Glob Environ Chang 15:253–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2004.12.009

Ben Youssef, A (2020) "How can Industry 4.0 contribute to combatting climate change?", Revue d'Economie Industrielle (French Industrial Economics Review), 169. 161–193. https://doi.org/10.4000/rei.8911

Ciarli T, Savona M (2019) Modelling the evolution of economic structure and climate change: a review. Ecol Econ 158:51–64

Fritzsche K, Niehoff S, Beier G (2018) Industry 4.0 and climate change—exploring the science-policy gap. Sustainability 10(12):4511. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124511

Stock T, Obenaus M, Kunz S, Kohl H (2018) Industry 4.0 as enabler for a sustainable development: a qualitative assessment of its ecological and social potential. Process Saf Environ Protect. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2018.06.026

Zeqiri A, Dahmani M, Ben Youssef A (2020) Digitalization of the tourism industry: what are the impacts of the new wave of technologies. Balkan Economic Review 2:63–82

Stafford M (2020) Connecting and communicating with the customer: advertising research for the hospitality industry. J Advert. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2020.1813663

Bello YO, Majebi EC (2018) Lodging quality index approach: exploring the relationship between service quality and customers satisfaction in hotel industry. J Tour Herit Stud 7(1):58–78

Böhm A, Follari M, Hewett A, Jones S, Kemp N, Meares D, Pearce D, Van Cauter K (2004) Vision 2020; forecasting international student mobility; a UK perspective. England: British Council Department

Jennifer B, Thea C (2013) Travel and tourism competitiveness report: reducing barriers to economic growth and job creation. World Economic Forum, Geneva

UNWTO, UNEP, and WMO (2008) Climate change and tourism – responding to global challenges. In Climate change and tourism – responding to global challenges. https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284412341

Hoogendoorn G, Fitchett JM (2016) Tourism and climate change: a review of threats and adaptation strategies for Africa. Curr Issue Tour 21(7):742–759. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1188893

Dubois G, Ceron JP, Gössling S, Hall CM (2016) Weather preferences of French tourists: lessons for climate change impact assessment. Clim Change. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1620-6

Gössling S, Hall CM (2006) Uncertainties in predicting tourist flows under scenarios of climate change. In Climatic Change. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-006-9081-y

Odimegwu F, Francis OC (2018) The interconnectedness between climate change and tourism. J Contemp Sociol Res 1(1):48–58

Peeters P, Dubois G (2010) Tourism travel under climate change mitigation constraints. J Transp Geogr 18(3):447–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2009.09.003

Scott D, Gössling S, Hall CM (2012) International tourism and climate change. In Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.165

Gössling S (2013) National emissions from tourism: an overlooked policy challenge? Energy Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.03.058

Adedoyin FF, Bekun FV (2020) Modelling the interaction between tourism, energy consumption, pollutant emissions and urbanization: renewed evidence from panel VAR. Environ Sci Pollut Res 27:38881–38900. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-09869-9

Article CAS Google Scholar

Gyamfi BA, Bein MA, Adedoyin FF, Bekun FV (2020) To what extent are pollutant emission intensified by international tourist arrivals? Starling evidence from G7 Countries. Environ Dev Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01765-7

Engler JO, Abson DJ, von Wehrden H (2019) Navigating cognition biases in the search of sustainability. Ambio. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-018-1100-5

Engler JO, Abson DJ, von Wehrden H (2021) The coronavirus pandemic as an analogy for future sustainability challenges. Sustain Sci 16:317–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00852-4

Fischer J, Dyball R, Fazey I, Gross C, Dovers S, Ehrlich PR, Brulle RJ, Christensen C, Borden RJ (2012) Human behavior and sustainability. Front Ecol Environ 10:153–160. https://doi.org/10.1890/110079

Ben Youssef A (2021) The Triple Climatic Dividend of COVID-19. In: Belaïd F, Cretì A (eds) Energy Transition, Climate Change, and COVID-19. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79713-3_6

Ben Youssef A, Zeqiri A, Dedaj B (2020) “Short and long run effects of COVID-19 on the hospitality industry and the potential effects on jet fuel markets”. IAEE Energy Forum / Covid-19 Issue 2020, pp. 121–124

IEA (2021) Global energy review: CO2 emissions in 2020, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/articles/global-energy-review-co2-emissions-in-2020

Car T, Stifanich LP, Simunic M (2019) Internet of things (IoT) in tourism and hospitality: opportunities and challenges. ToSEE - Tour South East Europe 5:163–175. https://doi.org/10.20867/tosee.05.42

Nayyar A, Mahapatra B, Le DN, Suseendran G (2018) Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) technologies for tourism and hospitality industry. Int J Eng Technol (UAE). https://doi.org/10.14419/ijet.v7i2.21.11858

Wiltshier P, Clarke A (2016) Virtual cultural tourism: six pillars of VCT using co-creation, value exchange and exchange value. Tour Hosp Res 17(4):372–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358415627301

Ivanov S, Webster C, Berezina K (2017) Adoption of robots and service automation by tourism and hospitality companies. Revista Turismo and Desenvolvimento, 1501–1517

Jung TH, tom Dieck MC, (2017) Augmented reality, virtual reality and 3D printing for the co-creation of value for the visitor experience at cultural heritage places. J Place Manag Dev 10(2):140–151. https://doi.org/10.1108/jpmd-07-2016-0045

Kuo CM, Chen LC, Tseng CY (2017) Investigating an innovative service with hospitality robots. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-08-2015-0414

Li J, Xu L, Tang L, Wang S, Li L (2018) Big data in tourism research: a literature review. Tour Manag 68:301–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.03.009

Nadkarni S, Kriechbaumer F, Rothenberger M, Christodoulidou N (2019) The path to the hotel of things: internet of things and big data converging in hospitality. J Hosp Tour Technol 11(1):93–107. https://doi.org/10.1108/jhtt-12-2018-0120

Eskerod P, Hollensen S, Morales-Contreras MF, Arteaga-Ortiz J (2019) Drivers for pursuing sustainability through IoT technology within high-end hotels-an exploratory study. Sustainability (Switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195372

Parida V, Sjödin D, Reim W (2019) Reviewing literature on digitalization, business model innovation, and sustainable industry: past achievements and future promises. In Sustainability (Switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020391

Baumeister RF, Leary MR (1997) Writing narrative literature reviews. Rev Gen Psychol 1(3):311

Ferrari R (2015) Writing narrative style literature reviews. Medical Writ 24(4):230–235

Yuan Y, Hunt HR (2009) Systematic reviews: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Am J Gastroenterol 104(1086–1092):9

Collins JA, Fauser CJMB (2005) Balancing the strengths of systematic and narrative reviews. Hum Reprod Update. 11(2):103–104. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmh058

Wohlin C (2014) Guidelines for snowballing in systematic literature studies and a replication in software engineering. In Proceedings 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, 321–330

Lasi H, Fettke P, Kemper H-G, Feld T, Hoffmann M (2014) Industry 4.0. Business and Information Systems Engineering

Frank AG, Mendes GHS, Ayala NF, Ghezzi A (2019) Servitization and Industry 4.0 convergence in the digital transformation of product firms: a business model innovation perspective. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 141:341–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.01.014

Bongomin O, Yemane A, Kembabazi B, Malanda C, Chikonkolo Mwape M, Sheron Mpofu N, Tigalana D (2020) Industry 40 disruption and its neologisms in major industrial sectors: a state of the art. J Eng 2020:8090521

Madsen DØ (2019) The emergence and rise of Industry 4.0 viewed through the lens of management fashion theory. Adm Sci 9(3):71. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9030071

Stankov U, Gretzel U (2020) Tourism 4.0 technologies and tourist experiences: a human-centered design perspective. Inf Technol Tour: 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-020-00186-y

Buhalis D, Amaranggana A (2015) Smart tourism destinations enhancing tourism experience through personalisation of services. In: Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2015. Springer International Publishing. pp 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14343-9_28

Buhalis D, Leung R (2018) Smart hospitality—interconnectivity and interoperability towards an ecosystem. Int J Hosp Manag 71(April):41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.11.011

Zeqiri A, Dahmani M, Ben Youssef A (2021) Determinants of the use of e-services in the hospitality industry in Kosovo. International Journal of Data and Network Science 369–382. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.ijdns.2021.5.006

Ben Youssef A, Dahmani M, Zeqiri A (2021) Do e-skills enhance use of e-services in the hospitality industry? A conditional mixed-process approach. International Journal of Data and Network Science 5(4):519–530. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.ijdns.2021.8.015

Pillai SG, Haldorai K, Seo WS, Kim WG (2021) COVID-19 and hospitality 5.0: redefining hospitality operations. Int J Hosp Manag 94(102869):102869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102869

Nahavandi S (2019) Industry 5.0—a human-centric solution. Sustainability. 11(16):4371. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164371

Kansakar P, Munir A, Shabani N (2019) Technology in the hospitality industry: prospects and challenges. IEEE Consumer Electronics Magazine. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCE.2019.2892245

Verma A, Shukla V (2019) Analyzing the influence of IoT in tourism industry. Proceedings of International Conference on Sustainable Computing in Science, Technology and Management (SUSCOM). SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3358168

Guttentag DA (2010) Virtual reality: applications and implications for tourism. Tour Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.07.003

Huang YC, Backman KF, Backman SJ, Chang LL (2016) Exploring the implications of virtual reality technology in tourism marketing: an integrated research framework. Int J Tour Res. 18(2):116–128. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2038

Ja Kim M, Lee C-K, Preis MW (2020) The impact of innovation and gratification on authentic experience, subjective well-being, and behavioral intention in tourism virtual reality: the moderating role of technology readiness. Telematics Inform. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101349

Kim MJ, Hall CM (2019) A hedonic motivation model in virtual reality tourism: comparing visitors and non-visitors. Int J Inf Manage. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.11.016

Kounavis CD, Kasimati AE, Zamani ED (2012) Enhancing the tourism experience through mobile augmented reality: challenges and prospects. Int J Eng Bus Manag. https://doi.org/10.5772/51644

Lee J, Bagheri B, Kao HA (2015) A cyber-physical systems architecture for Industry 4.0-based manufacturing systems. Manuf Lett. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mfglet.2014.12.001

Nagy J, Oláh J, Erdei E, Máté D, Popp J (2018) The role and impact of industry 4.0 and the internet of things on the business strategy of the value chain-the case of Hungary. Sustainability (Switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103491

Pereira AC, Romero F (2017) A review of the meanings and the implications of the Industry 4.0 concept. Procedia Manuf. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2017.09.032

Jazdi N (2014) Cyber physical systems in the context of Industry 4.0. Proceedings of 2014 IEEE International Conference on Automation, Quality and Testing, Robotics, AQTR 2014. https://doi.org/10.1109/AQTR.2014.6857843

Vaidya S, Ambad P, Bhosle S (2018) Industry 4.0 - a glimpse. Procedia Manuf. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2018.02.034

Munir A, Kansakar P, Khan SU (2017) IFCIoT: integrated fog cloud IoT: a novel architectural paradigm for the future internet of things. IEEE Consum Electron Mag 6(3):74–82. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCE.2017.2684981

Yun M, Yuxin B (2010) Research on the architecture and key technology of internet of things (IoT) applied on smart grid. In: 2010 International Conference on Advances in Energy Engineering. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICAEE.2010.5557611

Saranya C, Nitha KP (2015) Analysis of security methods in internet of things. Int J Recent Innov Trends Comput Commun 3(4):1970–1974

Mohanty SP, Choppali U, Kougianos E (2016) Everything you wanted to know about smart cities: the Internet of things is the backbone. IEEE Consum Electron Mag 5(3):60–70. https://doi.org/10.1109/mce.2016.2556879

van Krevelen DWF, Poelman R (2010) A survey of augmented reality technologies, applications and limitations. Int J Virtual Real

Tussyadiah IP, Wang D, Jung TH, tom Dieck MC (2018) Virtual reality, presence, and attitude change: empirical evidence from tourism. Tour Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.12.003

Rajesh Desai P, Nikhil Desai P, Deepak Ajmera K, Mehta K (2014) A review paper on oculus rift-a virtual reality headset. Int J Eng Trends Technol. https://doi.org/10.14445/22315381/ijett-v13p237

Mura P, Tavakoli R, Pahlevan Sharif S (2017) ‘Authentic but not too much’: exploring perceptions of authenticity of virtual tourism. Inf Technol Tour. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-016-0059-y

Cheong R (1995) The virtual threat to travel and tourism. Tour Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(95)00049-T

Tung VWS, Law R (2017) The potential for tourism and hospitality experience research in human-robot interactions. In International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2016-0520

Horváth D, Szabó RZ (2019) Driving forces and barriers of Industry 4.0: do multinational and small and medium-sized companies have equal opportunities? Technol Forecast Soc Chang. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.05.021

World Tourism Organization (2016) UNWTO world tourism barometer. Retrieved from Madrid: UNWTO: http://www.unwto.org/facts/eng/barometer.htm

United Nations (2015) Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform

UNFCCC (2015) Paris Agreement. In United Nations. Available from: https://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/convention/application/pdf/english_paris_agreement.pdf

Nicholls S (2006) Climate change, tourism and outdoor recreation in Europe. Manag Leis. https://doi.org/10.1080/13606710600715226

Scott D, Peeters P, Gössling S (2010) Can tourism deliver its “aspirational” greenhouse gas emission reduction targets? In Journal of Sustainable Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669581003653542

Sinclair-Maragh G (2016) Climate change and the hospitality and tourism industry in developing countries. In: Climate Change and the 2030 Corporate Agenda for Sustainable Development. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2051-503020160000019001

IPCC (2007) Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13163-011-0090-7

Hall CM, Amelung B, Cohen S, Eijgelaar E, Gössling S, Higham J, Leemans R, Peeters P, Ram Y, Scott D (2015) On climate change skepticism and denial in tourism. J Sustain Tour. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.953544

IPCC (2018) Global warming of 1.5°C. Ipcc.ch. Published 2018. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/06/SR15_Full_Report_High_Res.pdf . Accessed 22 Jul 2021

Zanni AM, Goulden M, Ryley T, Dingwall R (2017) Improving scenario methods in infrastructure planning: a case study of long-distance travel and mobility in the UK under extreme weather uncertainty and a changing climate. Technol Forecast Soc Chang. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.10.002

Coghlan A, Prideaux B (2009) Welcome to the wet tropics: the importance of weather in reef tourism resilience. Curr Issue Tour. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500802596367

Patterson T, Bastianoni S, Simpson M (2006) Tourism and climate change: two-way street, or vicious/virtuous circle? J Sustain Tour 14(4):339–348. https://doi.org/10.2167/jost605.0

Scott D, Hall CM, Gössling S (2016) A review of the IPCC Fifth Assessment and implications for tourism sector climate resilience and decarbonization. J Sustain Tour 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1062021

Dawson J, Scott D (2013) Managing for climate change in the alpine ski sector. Tour Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.07.009

Dogru T, Marchio EA, Bulut U, Suess C (2019) Climate change: vulnerability and resilience of tourism and the entire economy. Tour Manage. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.12.010

Ahmad MW, Mourshed M, Mundow D, Sisinni M, Rezgui Y (2016) Building energy metering and environmental monitoring - a state-of-the-art review and directions for future research. Energy Build 120:85–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2016.03.059

Costa A, Keane MM, Torrens JI, Corry E (2013) Building operation and energy performance: monitoring, analysis and optimisation toolkit. Appl Energy 101:310–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2011.10.037

Shaikh PH, Nor NBM, Nallagownden P, Elamvazuthi I, Ibrahim T (2014) A review on optimized control systems for building energy and comfort management of smart sustainable buildings. In Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.03.027

Harish VSKV, Kumar A (2016) A review on modeling and simulation of building energy systems. In Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.12.040

Auffhammer M, Baylis P, Hausman CH (2017) Climate change is projected to have severe impacts on the frequency and intensity of peak electricity demand across the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 14(8):1886-1891. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1613193114

Belaid F, Ben Youssef A, Lazaric N (2020) Scrutinizing the direct rebound effect for French households using quantile regression and data from an original survey. Ecol Econ 176(106755):106755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106755