clock This article was published more than 2 years ago

The Jewish travel guide that inspired the Green Book

Fearing that her land would be seized as World War I approached, Austrian-born Pessah “Pearl” Ravitz fled to New York City to start a new life. She had imagined New York as a place of promise, ripe with opportunity for a resourceful woman such as herself. The city was quick to disappoint. Ravitz was met with discrimination because of her Jewish identity, and life in the metropolis was stifling. In the summer, sweltering temperatures exacerbated the city’s stench.

“They came to this country looking for the streets paved with gold, but what they got was a lot of antisemitism,” said Alan Kook, her great-great-grandson.

Ravitz managed to buy land not far away in Pennsylvania and began to re-create the life she had enjoyed in Austria, where she had owned a successful farm and supplemented her income in the winter by taking in traveling circus troupes as boarders, according to Kook. In Pennsylvania, too, she put up boarders in the summer, welcoming friends and friends of friends looking for relief from the city heat. She would cook and entertain, styling the farm as a mountain getaway.

Ravitz was one of thousands of Jewish farmers who thrived with this hybrid farm-inn model in early 20th-century America. More than 1 million Jews had immigrated to the United States by 1924, with many clustering around New York City. Working-class Jews living in cramped tenement houses were keen to escape to the countryside in the summer, but many hotels explicitly forbade Jewish guests. This is how people like Ravitz — and many others, scattered around the Catskills, Connecticut and New Jersey — came to run thriving boarding businesses. Some would eventually give up farming to expand their hotels.

The Jewish Vacation Guide, first published around 1916, compiled these addresses, alongside a whole network of Jewish-owned or Jewish-friendly places where it was safe for Jews to eat, sleep and visit. This guide, and other travel advice like it published in the Yiddish press, served as a vital tool in navigating the potential danger of Jewish travel in early America. It even went on to inspire the “Green Book,” a widely used guide for Black travelers.

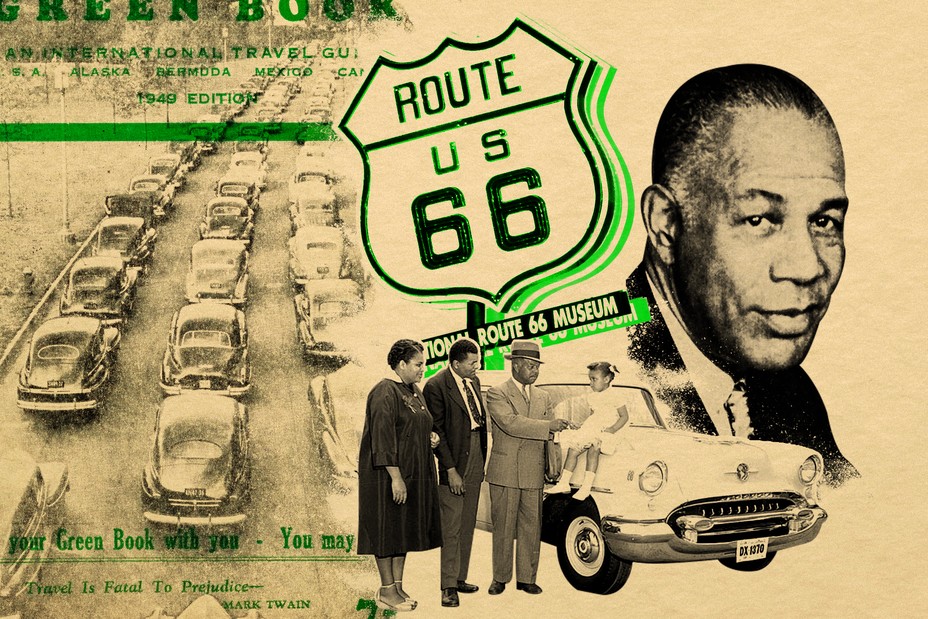

‘Life or death for black travelers’: How fear led to ‘The Negro Motorist Green-Book’

Antisemitism was widespread in 20th-century America. Membership in the Ku Klux Klan saw a major resurgence in the 1920s, with estimates ranging from 3 million to as many as 8 million members nationwide. While the KKK overwhelmingly targeted Black Americans, Jews also faced frequent discrimination. “No Hebrews or Consumptives Accepted” read many hotel advertisements in the first quarter of the 20th century. “Gentiles only” appeared in hospitality advertising, as did “Christian clientele only.” A study conducted by the Anti-Defamation League in 1957 found that virtually every state had hotels and resorts that barred Jews.

The Jewish Vacation Guide connected Jews to a network of places that did not just tolerate, but welcomed them. Dozens of the listings touted kosher meals, often made with farm-fresh butter and eggs. The conditions at some of the rented rooms were far from luxurious, but they made up for modest offerings in hospitality and affordability.

One farmhouse advertisement promised: “You will be made to feel at home.” The majority of the listings were written in Yiddish, given that many Jewish Americans were immigrants or the children of immigrants whose primary language was Yiddish.

A large number of the properties were concentrated in the Catskill Mountains. “This is the genesis of the Catskills as a Jewish vacation region. It really started as a grass-roots thing: people from the city who wanted to get out of the city during the summer,” said Eddy Portnoy, academic adviser at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. “When Jewish farmers realized this could be a lucrative prospect, they began re-creating their own houses as boardinghouses, or even building extra houses on their properties.” The vacation guide itself was published by the Federation of Jewish Farmers of America.

Madeleine Albright said she didn’t know she was Jewish until The Post told her

While many of the properties in the guide were mom-and-pop affairs, by 1917 some of the farmhouses had begun to transform into resorts. “The Grand Mountain House” in Sullivan County, N.Y., for instance, advertised itself as a “country summer home with all the up-to-date city conveniences,” including an orchestra, a casino, billiards, tennis, baseball and a professional chef.

The success of these hotels, thanks in part to the guide, soared in the following decades. The Catskills became a vacation hot spot. Grossinger’s Catskill Resort Hotel, for instance, which was one of the most successful resorts in the region for decades, began as a dilapidated barn in the 1910s. It transformed into a sprawling 1,200-acre, 35-building resort, complete with dancing, sports, lakes and even its own airstrip.

The guide contained not only hotel listings but everything one might need on a vacation: automobile repair, drugstores, grocers, tailors, cobblers and a Kodak photography studio. Traveling safely was about more than just finding a welcoming hotel. It meant preparing for many possible contingencies: No one wants to find himself with a broken-down car in the mountains, only to be refused service at a garage.

This type of scenario — refusal of service, or even violent reprisal — was a serious concern in Jim Crow-era America, and it inspired the postman Victor Hugo Green to write a similar guide for Black people. In the introduction to his “Negro Motorist Green Book,” Green credited Jewish guides for serving as a template for his book, noting that “the Jewish press” had “long printed information about places that are restricted.” First published in 1936, the Green Book similarly listed hotels, restaurants, mechanics, barbershops and nightclubs.

Putin says he’ll ‘denazify’ Ukraine. Its Jewish president lost family in the Holocaust.

Travel generally carried a much higher risk for Black people than for Jews. As the book’s cover warned: “Carry your Green Book with you … you may need it … ” Black motorists risked exclusion from “Whites only” spaces, police harassment, physical violence and even lynching. “While we might be inclined to make analogies between antisemitism and anti-Black racism, it’s important to identify where those analogies end,” said Eli Rosenblatt, an assistant professor of religious studies at Northwestern University. “Jews who were predominantly of European origin at the time availed themselves of spaces for Whites only.”

Both guides would eventually become obsolete. In 1967, three years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, the Green Book ceased publication. It’s not clear when the Jewish Vacation Guide stopped being published, but for Jewish travelers, the expansion of the Catskills into a sought-after travel destination in the mid-century meant that they had their pick of hotels much sooner.

When Black and Jewish Americans both faced frequent discrimination in accommodations, they sometimes opened their doors to one another. In the early 1950s, Grossinger’s invited Jackie Robinson, the first Black man to play major league baseball, to stay for the summer. Grossinger’s, which started off as a ramshackle farm offering relief from city stress and antisemitism, had grown into an oasis. The Grossinger family extended the feeling of “heimish” — what Portnoy described as a homey coziness — to a man battling constant discrimination and harassment.

“I doubt that she [Jennie Grossinger] knew or could have fully appreciated how important the invitation was to Jack and me in the early Fifties,” Robinson’s wife, Rachel, wrote in her memoir. For their family, there were few hotels “ to rival the Big G .”

An earlier version of this article stated incorrectly that Grossinger’s hosted Eddie Fisher and Elizabeth Taylor’s wedding. In fact, Fisher and actress Debbie Reynolds were married there. This version has been corrected.

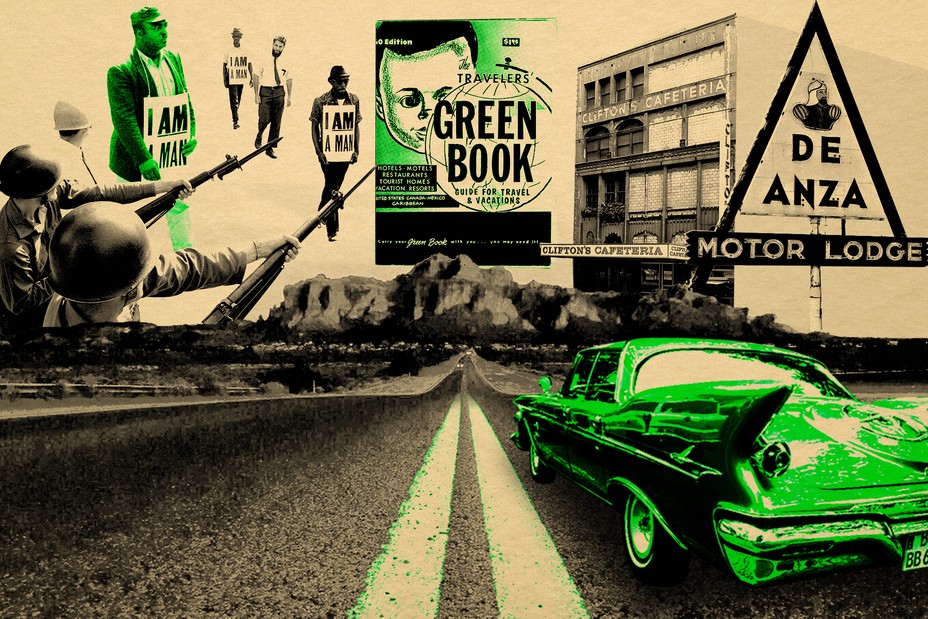

The Roots of Route 66

America’s favorite highway usually evokes kitschy nostalgia. But for black Americans, the Mother Road’s lonely expanses were rife with danger.

No other road has captured the imagination and the essence of the American Dream quite like Route 66. The idea behind the “Mother Road” was to connect urban and rural America from Chicago all the way to Los Angeles, crossing eight states and three time zones. With more hope than resources, Dust Bowl migrants and others escaping poverty caused by the Great Depression could motor west on Route 66 in search of a better life. This 2,440-mile “ Road of Dreams ” speckled with romantic and unconventional attractions symbolized a pathway to easier times. It was one of the few U.S. highways laid out diagonally, and it cut across the country like a shortcut to freedom.

But though that message went out to all Americans, it was really meant only for white Americans. Just one year before construction on Route 66 began, the Chicago Tribune suggested in an editorial on August 29, 1925, that black people avoid recreational sites altogether:

We should be doing no service to the Negroes if we did not point out that to a very large section of the white population the presence of a Negro, however well behaved, among white bathers is an irritation. This may be a regrettable fact to the Negroes, but it is nevertheless a fact, and must be reckoned with … [T]he Negroes could make a definite contribution to good race relationship by remaining away from beaches where their presence is resented.

Not only were they shut out of pools and beaches, black Americans also couldn’t eat, sleep, or even get gas at most white-owned businesses. To avoid the humiliation of being turned away, they often traveled with portable toilets, bedding, gas cans, and ice coolers. Even Coca-Cola machines had White Customers Only printed on them. In 1930, 44 out of the 89 counties that lined Route 66 were all-white communities known as “sundown towns”—places that banned black people from entering city limits after dark. Some posted signs that read, “Nigger, Don’t Let the Sun Set on You Here.”

Route 66 started out in Illinois, a state that itself had nearly 150 sundown towns. The road certainly did not mean freedom for everyone, and it bore witness to some of the nation’s worst acts of racial terrorism. Today, politicians and television anchors speak of “terrorism” as though it is a new phenomenon to the United States. Terrorism is not new, and to think so is a grievous slight to the nation’s native peoples, to its multitudes of immigrants, and to its legions of black Americans—all of whom have long been terrorized for calling America home. In fact, even before Route 66 was officially connected and enshrined, the roads that would come to form it linked one atrocity to the next.

Take, for example, one violent night in 1906 in Springfield, Missouri, which would soon become the birthplace of Route 66; though the road starts out in Chicago, the route was officially designated as “66” in Springfield. During a grisly lynching on Easter weekend, a vigilante white mob dragged Horace Duncan and Fred Coker to the town square, hanged them, burned their bodies while thousands watched, and then distributed their body parts among the crowd as keepsakes.

In 1921, the Tulsa Race Riot erupted in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma. It was one of the nation’s most devastating acts of terrorism against African Americans. Greenwood was an unusually vibrant community of successful black entrepreneurs, doctors, and lawyers. Booker T. Washington called it “Black Wall Street,” and it was arguably the wealthiest black neighborhood in the South. But, after a young black man was wrongfully accused of assaulting a white woman, an angry lynch mob broke out. Long-held jealousies over black prosperity and Greenwood’s wealth ignited a riot. A white mob set the neighborhood on fire. After 16 hours, at least 300 people had died, 35 blocks of the Greenwood District had burned to the ground, and more than 10,000 black residents had been left homeless.

Recommended Reading

To Be Both Midwestern and Hmong

Eight Books That Explain the South

Reading Too Much Political News Is Bad for Your Well-Being

On Route 66, every mile was a minefield. Businesses with three “K”s in the title, such as the Kozy Kottage Kamp or the Klean Kountry Kottages, were code for the Ku Klux Klan and served only white customers. Black motorists of course also had to avoid sundown towns such as Edmond, Oklahoma. In the 1940s, the Royce Café, located right on Route 66, proudly announced on its postcards that Edmond was “‘A Good Place to Live.’ 6,000 Live Citizens. No Negroes.” The humiliation of being shut out of not only public spaces but entire towns was bad enough, but for black people, there were always plenty of even bleaker fears—every stop was a potential existential danger. The threat of lynching was of particular concern when black people traveled through the Ozarks on Route 66. For instance, the Ku Klux Klan ran Fantastic Caverns, a popular tourist site near Springfield. They held their cross burnings inside.

For many, the vulnerability of the road meant always having a plan, a cover story, or even a disguise. One popular safety precaution? A chauffeur’s hat. Black motorists who drove nice cars were especially susceptible to regular harassment by law enforcement. In 1930, the black columnist George Schuyler wrote, “Blacks who drove expensive cars offended white sensibilities,” and some black people “kept to older models so as not to give the dangerous impression of being above themselves.”

In the 1950s, my stepfather, Ron, experienced this firsthand as a child. His father had a good job with the railroad and owned a nice car. After being stopped by a sheriff while on vacation with his family, the sheriff asked Ron’s dad where he got the car. Knowing better than to say it was his, Ron’s father pretended to be a chauffeur. When the sheriff asked about the other people in the car, Ron’s dad pretended they weren’t his family. He said the woman sitting next to him (his wife) was his employer’s maid, and he was taking her and her son (Ron) home. The sheriff asked, “Where’s your chauffeur hat?” Ron’s dad was ready; he had one in the car: “Hanging right up in the back, Officer.”

Despite all the dangers, millions of black vacationers, like Ron’s family, did explore the country—many relying on a unique travel guide, The Negro Motorist Green Book . Victor H. Green, a black postal worker from Harlem, New York, published his guide from 1936 until 1966. His Green Book featured barbershops, beauty salons, tailors, department stores, taverns, gas stations, garages, and even real-estate offices that were willing to serve black people. A page inside boasted, “Just What You Have Been Looking For!! NOW WE CAN TRAVEL WITHOUT EMBARRASSMENT.”

Green modeled his book after Jewish travel guides created for the Borsht Belt in the 1930s. Other black travelers’ guides existed— Hackley and Harrison’s Hotel and Apartment Guide for Colored Travelers (1930-1931), Travel Guide (1947-1963), and Grayson’s Guide : The Go Guide to Pleasant Motoring (1953-1959)—but the Green Book was published for the longest period of time and had the widest readership. It was promoted by word of mouth, and a national network of postal workers led by Green sought out advertisers. Esso Gas Stations (Standard Oil, which operates as Exxon today) sold the Green Book and hired two black marketing executives, James A. Jackson and Wendell P. Allston, to promote and distribute it. By 1962, the Green Book reached a circulation of 2 million people.

The Green Book covered the entire United States, but during the time it was in publication, Route 66 was easily the most popular road in America. And driving was the most popular pastime. Automobile travel symbolized freedom in America, and the Green Book was a resourceful, innovative solution to a horrific problem. People called it the “Bible of black travel” and “AAA for blacks,” but it was so much more. It was a powerful tool for blacks to persevere and literally move forward in the face of racism.

Although 6 million black people hit the road to escape the Jim Crow South, they quickly learned that Jim Crow had no borders. Segregation was in full force throughout the country. Out of the eight states that ran through Route 66 (Illinois, Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California), six had official segregation laws as far west as Arizona—and all had unofficial rules about race.

It was assumed the West was more liberated than the South, but thanks to the enormity of the American West’s expanses, it in some ways was even more dangerous. The farther west anyone traveled, the fewer services were available—for white people and especially for black people. Food and lodging were scattered over long distances, and there were also just fewer people living out West in general, and fewer black people in particular, which reduced the chances that black travelers could find trustworthy help in case they had car trouble or needed directions. In the Pulitzer Prize – winning The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration , the writer Isabel Wilkerson recounts Dr. Robert Foster’s harrowing journey in the West, where he would fall asleep at the wheel from exhaustion simply because he had been turned away from every motel he stopped at for being black.

Even once black travelers reached a multiracial city, such as Albuquerque, New Mexico, only 6 percent of the more than 100 motels along Albuquerque’s slice of Route 66 admitted them. And although there were no formal segregation laws on the books in California, both Glendale and Culver City were sundown towns and the sun-kissed beaches of Santa Monica were segregated. Route 66 epitomized Americana—for white people. For black folks, it meant encountering fresh violence and the ghosts of racial terrorism already haunting the Mother Road.

This is why the cover of the Green Book warned, “Always Carry Your Green Book With You—You May Need It.” In Chicago, for example, there were no Green Book businesses on Route 66 at all for nearly three decades. (There were Green Book businesses in other parts of Chicago—but not on the Road of Dreams.) After leaving Chicago on Route 66, the next Green Book sites were more than 180 miles away in Springfield, Illinois. But Springfield at least was helpful, with 26 listings: 13 tourist homes, four taverns, three beauty parlors, two service stations, and one restaurant, barbershop, drugstore, and hotel. If you were black and didn’t have this information, how would you know where to go? You could easily wind up in the wrong town after dark.

Of course Route 66 wasn’t any more racist than any other road in America at the time. What makes Route 66 different is that the open-road branding associated with it celebrated a time when black Americans had to navigate racial violence and the Jim Crow policies that shut them out of businesses and recreational sites. Plus, the desolation of Route 66’s stretches left black motorists particularly exposed. The American ideals associated with Route 66, then and now, have usurped the narrative, erasing the more harrowing aspects of the nation’s past. So when the United States promotes freedom and democracy, fights for those values abroad, and then fails to abide by them at home, the hypocrisy feels cruel.

During World War II, Route 66 played a major role in military efforts, becoming a primary route for shuttling military supplies across the country. It was used so heavily that a 200-mile stretch of asphalt was thickened so that it could better handle military convoys. At that time, American soldiers fought for human rights overseas, but the troops were still segregated at home. As a result, black soldiers made good use of the Mother Road. For black soldiers stationed at Fort Leonard Wood near Rolla, Missouri, for example, their best option for a little R&R was a full 80 miles away: Graham’s Rib Station in Springfield, Missouri, an integrated local landmark that opened in 1932 and was owned by an African American couple, James and Zelma Graham. The onsite motel court was built during the war specifically to offer lodgings to black soldiers—but Pearl Bailey and Little Richard stayed there as well. (Today, nothing remains of Graham’s, except a tourist cabin that an area law firm uses as its storage shed.)

The vast American landscape meant long, lonely stretches of perilously empty roads, and places like Graham’s and other Green Book properties were vital sources of refuge. Today, they still play a critical role in U.S. history, revealing the untold story of black travel. Many of the buildings along Route 66 are physical evidence of racial discrimination, providing a rich opportunity to reexamine America’s story of segregation, black migration, and the rise of the black leisure class. But the current passion for gentrification and suburban sprawl is expunging the past: Most Green Book properties have been razed and many more are slated for demolition. That’s why the National Park Service’s Route 66 Preservation Program approached me in 2014 to document Green Book sites on Route 66 and to produce a short video. I’ve estimated that nearly 75 percent of Green Book sites have been demolished or radically modified, and the majority that remain have fallen into disrepair, so it’s crucial to preserve whatever sites are left.

That means places such as the Threatt Filling Station, a one-story sandstone bungalow with a slightly pitched and gabled roof, wide eaves, and a wooden door. Alan Threatt Sr., a black man, owned the gas station and served black motorists from 1915 to the 1950s in Luther, Oklahoma. His family quarried the native sandstone on their homestead land to build the filling station, which bordered their property at the intersection of Route 66 and Pottawatomie Road. And, although it’s no longer open to the public, the building still stands. The National Park Service included the Threatt Filling Station on its National Register of Historic Places in 1995.

The De Anza Motor Lodge on Route 66 in Albuquerque was built in 1939 and run by a prominent Zuni Indian trader; the motor lodge served black folks on a stretch of road where there were few options available to them. The Spanish-Pueblo Revival style of the building features a conference room with seven 20-foot murals painted by a Zuni artist. The motor lodge was slated for demolition when the city purchased it in 2003. Still, the property sat empty for more than a decade after that purchase. (Although, the motor lodge did have a brief gig as the setting for a scene in Breaking Bad .) Now, the city has an $8.2 million plan to convert the property into a condo-hotel hybrid with shops and restaurants.

One Green Book business that did survive over the decades is Clifton’s, a quirky Depression-era cafeteria in downtown Los Angeles at the corner of 7th Street and South Broadway—the original terminus of Route 66. Clifton’s closed for a few years starting in 2011 to undergo a $10 million renovation before reopening last year. It’s now possibly the largest and most unusual cafeteria in the world—with five floors of history and taxidermy and a giant fake redwood tree rising up through the center. In the evenings, classic concoctions like absinthe are served at the bar, which features a 250-pound meteorite sitting on it. The original owner—a white man, a Christian, and the son of missionaries—Clifford Clinton, had traveled with his parents to China, where he witnessed that country’s brutal and abject poverty firsthand. He couldn’t understand how America, a country with so much wealth, could allow its citizens to go hungry. So he never turned away any customers—even those who couldn’t afford to pay. Clinton followed what he called the “Cafeteria Golden Rule.” His menu read, “Pay What You Wish” and “Dine Free Unless Delighted.”

One of the Green Book ’s most unusual Route 66 sites was Murray’s Dude Ranch. This lost gem was billed as “The Only Negro Dude Ranch in the World”—which it very likely was. The 40-acre ranch was situated on the edge of the Mojave Desert, with Joshua, yucca, and mesquite trees dotting the landscape. A black couple, Nolie and Lela Murray, owned the property and offered black people traveling on Route 66 much-needed lodging and some good old-fashioned Western recreation. All manner of black and white celebrities visited, from Lena Horne and Joe Louis to Hedda Hopper and Clara Bow. Pearl Bailey ultimately bought the property in 1955 but sold it in the mid-1960s. Sadly, today there’s no physical evidence that Murray’s Dude Ranch ever existed.

The colorful historic sites of Route 66 have been mostly lost to time and neglect. But when a site is nurtured, like Clifton’s, or commemorated, like the Threatt Filling Station, it can be an important connection to the past. In Tulsa, for example, travelers can now visit the Greenwood Cultural Center to learn about the Tulsa Race Riot. The Greenwood District—“Black Wall Street”—was eventually rebuilt; now the John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park offers a space for healing, with a 25-foot memorial and three 16-foot granite sculptures honoring the dead.

In 1978, at the age of 7, I was riding in the car with my mother in Houston, Texas, when I saw a prison chain gang; shackled men were working in a sugarcane field. I said, “Mom, isn’t slavery over?”

“Yes, honey,” she replied.

I said, “Why are all of these black men in chains working in a field?”

“Well, they’re prisoners.”

“Why are they all black ?”

She had no answer, or maybe she just didn’t know how to explain institutional racism to a 7-year-old. Either way, it was painfully obvious to me that there was a problem. I’ve been questioning the existence of racial equality ever since.

When I talk to people about the full history of Route 66 and the Green Book , they say, “Thank God we don’t need that anymore.” But while black people may not have to worry about KKK cross burnings at tourist sites, they still have to worry about being shot by the police. The spot where Michel Brown bled out in the street for four hours in Ferguson, Missouri, is just a couple of miles from the original Route 66.

In a country that desperately, fitfully, tries to be color-blind, even the first black president has not been able to stop the bleeding, let alone heal the old and deep wounds of white supremacy and systemic racism. Black veterans were once blocked from taking advantage of the GI Bill, missing out on valuable educational resources. The Federal Housing Association redlined neighborhoods and denied loans to black people, preventing them from accessing wealth-building opportunities freely given to white people. Since the 1970s, the black male prison population has skyrocketed by 700 percent, and Justice Department data now predicts that one in three black male babies born in America will be incarcerated in their lifetimes.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Green Book ceased publication right around the time the Civil Rights Act passed. Of course, the Civil Rights Act did not fix racism, and discrimination persisted. As the Equal Justice Initiative’s Bryan Stevenson points out: Civil rights in America is too often seen as a “three-day carnival: On day one, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus. On day two, Martin Luther King led a march on Washington. And on day three, we passed the Civil Rights Act and changed all the laws.” Problem solved.

Given this mass denial, it’s not surprising that Route 66 is weighted down with nostalgia, suffocating from an idealized past that never was. But Americans should not be so quick to pat themselves on the backs just because, nowadays, black people can drive U.S. highways mostly without incident. Not when a struggle for social mobility continues to take a debilitating toll on black Americans. And it is too early to celebrate the nation’s racial tolerance when ongoing racism and xenophobia is camouflaged under the banner of patriotism.

Today, Route 66 has surrendered to a series of bypasses, causeways, and highways, but the path it traced is still troubled: “American Owned” signs line the old Route 66; they are code for “Not Owned by Immigrants.” In Noel, Missouri, Somali immigrants say they are not welcome at Kathy’s Kountry Kitchen, where even now servers wear T-shirts reading, “I got caught eating at the KKK.” Stories like these are why the rosy hue of Route 66 nostalgia leaves a bitter chill in the souls of black people.

I only learned about the Green Book after being commissioned to write a Moon Series travel guide on Route 66. As I paged through all the kitschy advertising of postwar suburban white families in Airstream Trailers and chrome-finned Chevys getting their “kicks” at campy Americana landmarks, I wondered: Where are the black people? I discovered that more than 90 percent of those who have written about the Mother Road are white—and male. I may be the only black woman to have written a travel guide about Route 66. And after discovering the Green Book , I was never able to look at America’s favorite highway the same way again—the way those other tour guides seem to.

I wanted to share the real story of Route 66—its promise of freedom and its failure to live up to that promise. For black Americans who hit the road with a copy of the Green Book , a guide expressly created to keep them safe in a wildly perilous landscape, they surely already understood that the hopeful Mark Twain quote gracing almost every Green Book cover—“Travel is fatal to prejudice”—was purely aspirational.

Advertisement

How the Jewish Vacation Guide helped families travel safely to the Catskills

Copy the code below to embed the wbur audio player on your site.

<iframe width="100%" height="124" scrolling="no" frameborder="no" src="https://player.wbur.org/hereandnow/2022/04/19/jewish-vacation-guide-catskills"></iframe>

Editor's note: This segment was rebroadcast on July 14, 2023. Click here for that audio.

The Catskill Mountains became famous for Jewish resorts in the early to mid-20th Century. But such enclaves formed out of necessity — with antisemitism widespread and millions of Ku Klux Klan members nationwide.

It all started with a book: the Jewish Vacation Guide, which cataloged where Jews would be safe, well-fed and entertained. It also inspired the Green Book, a widely used guide for Black travelers.

Host Celeste Headlee speaks with Eddy Portnoy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

This segment aired on April 19, 2022.

More from Here & Now

- Donor Portal Sign In

- PBS Sign In

How the Jewish Vacation Guide helped families travel safely to the Catskills

The Catskill Mountains became famous for Jewish resorts in the early to mid-20th Century. But such enclaves formed out of necessity — with antisemitism widespread and millions of Ku Klux Klan members nationwide.

It all started with a book: the Jewish Vacation Guide, which cataloged where Jews would be safe, well-fed and entertained. It also inspired the Green Book, a widely used guide for Black travelers.

Host Celeste Headlee speaks with Eddy Portnoy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

This article was originally published on WBUR.org.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Reflecting on The Jewish Vacation Guide

Editor’s note: Click here for the original audio.

The Catskills became famous for its Jewish resorts, popular in the early to mid-20th century. But such enclaves formed out of necessity, with antisemitism widespread and millions of Ku Klux Klan members nationwide. And it all started with a book: the Jewish Vacation Guide, which cataloged where Jews would be safe, well-fed and entertained. It also inspired the Green Book, a widely used guide for Black travelers.

Host Celeste Headlee speaks with Eddy Portnoy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

This article was originally published on WBUR.org.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Reflecting on The Jewish Vacation Guide

Editor’s note: Click here for the original audio.

The Catskills became famous for its Jewish resorts, popular in the early to mid-20th century. But such enclaves formed out of necessity, with antisemitism widespread and millions of Ku Klux Klan members nationwide. And it all started with a book: the Jewish Vacation Guide, which cataloged where Jews would be safe, well-fed and entertained. It also inspired the Green Book, a widely used guide for Black travelers.

Host Celeste Headlee speaks with Eddy Portnoy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

This article was originally published on WBUR.org.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Reflecting on The Jewish Vacation Guide

Editor’s note: Click here for the original audio.

The Catskills became famous for its Jewish resorts, popular in the early to mid-20th century. But such enclaves formed out of necessity, with antisemitism widespread and millions of Ku Klux Klan members nationwide. And it all started with a book: the Jewish Vacation Guide, which cataloged where Jews would be safe, well-fed and entertained. It also inspired the Green Book, a widely used guide for Black travelers.

Host Celeste Headlee speaks with Eddy Portnoy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

This article was originally published on WBUR.org.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Exploring a 1930s Jewish reckoning with danger and helplessness

Kenneth Moss’ latest book, An Unchosen People , traces cultural and political creativity among Polish Jews born not out of possibility and agency, but from a hard confrontation with the rising danger of right-wing politics and the community’s powerlessness to overcome it

By Sarah Steimer

The fraught history of the three million Jews who lived in Poland before the Second World War is often written today as a story of creativity and resistance, of an unbowed community not only fighting to protect its rights but imbued with the conviction that it had in its hands the power to shape its own collective destiny. A new book by Kenneth Moss, the Harriet and Ulrich E. Meyer Professor of Jewish History and the College, tells a more complicated story of how, when facing rising ethnonationalism, fascism, and antisemitism across Europe in the 1930s, many Polish Jews began to recognize that that their community was in real danger and they had very little capacity to do much about it. At most, Jewish political efforts might help a small minority of the community win a reasonable chance at a decent future.

In An Unchosen People, to be published by Harvard University Press in December, Moss traces the transformation of interwar Polish Jewish thought about the political pathologies into which modern polities can fall quickly — about the weakness of liberalism; diaspora’s vulnerability and Zionism’s promise of an alternative; and about the need for minority communities to think not only in terms of ideals and hopes, but also in terms of danger, vulnerability, relative powerlessness, and hard choices.

“This became a book about people who in some ways realized they no longer have the luxury of thinking about the identity they want, the culture they want, the ideals they wish to realize in everyday life,” Moss says. “In fact, they have to begin their political thought anew from the recognition of their community’s incredibly limited capacities to determine its own future in the face of rising danger.”

Moss’ previous book, the prize-winning Jewish Renaissance in the Russian Revolution , examined bold visions of Yiddish and Hebrew cultural renaissance in the first years of the Russian Revolution. That previous book, he acknowledges, can be read as a study in Jewish optimism about cultural possibility and agency in the diaspora. Yet as Moss researched An Unchosen People — reading Yiddish, Hebrew, and Polish diaries by young people; works of sociology and investigative journalism; the impressions of visitors from Palestine and the U.S.; poetry and fiction; and private letters — he discovered a story not of cultural resistance, social adaptation, or undimmed ideological faith, but of political reckoning.

Moss says he was concerned that Jewish historians of the era have confused their desire for a usable past with the past itself, and was driven to think about moments and ways in which Jewish history has been defined by powerlessness.

“I do think we are obliged to think about the ways in which the Diaspora Jewish experience shouldn't just be celebrated in some sort of counter-historical way, but has to be reckoned with,” he says. “In a much more modest way, I wanted to get past the whole irresolveable debate we have today ad nauseum about ‘What could people have known before the Holocaust?’ and simply to show that there were people at the time reckoning with the question of: ‘Have we overestimated the possibility of creating a viable future for ourselves in the Diaspora? Have we overestimated our own capacities to define the terms of our life?’”

Because numerous Polish Jews ended up in this place of reckoning, it struck him as a good focus of study — “even if it seems unseasonable.”

Moss says An Unchosen People rethinks Polish Jewish history prior to the Holocaust in five ways. In part, it’s a grassroots history that shows how early and how often ordinary Polish Jews began to conclude that there was little prospect of a decent future for themselves and their children in Europe. It’s also an intellectual history of Jewish sociologists, political scientists, and political psychologists who reluctantly recognized that they had to put aside cherished progressive ideas about human rationality and progress and instead seek new tools to understand the horrifying speed and intensity with which a dangerous politics of hate and fear was reshaping the world around them.

An Unchosen People is also, Moss says, a new kind of history of Zionism. After reading letters from Zionist emissaries from Palestine to Poland, he discovered that while Zionist and anti-Zionist camps faced off in a battle of ideas, many Polish Jews grew interested in Zionist efforts on more practical grounds: They were curious to learn whether a new life in Palestine might really be different, better, and available to them as individuals.

Moss offers an equally unfamiliar history of Jewish Diasporism. Instead of telling the familiar stories of revolutionaries, he instead draws attention to Diasporist activists, scholars, and poets who were driven to think about the damage that the feelings of futurelessness were doing to people’s psyches — and to explore whether art and culture could counter the damage done.

Finally, An Unchosen People digs down into the intimate discussions of friends and families to reconstruct a history of Polish Jewish ethical debate about the competing claims of communal, individual, and familial need in the face of the impossibility of finding happy solutions for all, or even most.

Moss points to the writings of one 20-year-old who left a diary and a series of critical reflections that capture a deepening critical insight into Polish Jewry’s worsening situation and a recognition that, as the young man put it, “we're just not going to find any medicine that will suffice for the whole community.” Despite the young man’s own enthusiasm for diasporic Yiddish culture, he joined the Zionist youth pioneer movement in the hopes of getting one of the limited British certificates that allowed immigration to Palestine.

“To read that was wrenching,” Moss says. “But it clarified for me what the book was really about.”

For Moss, the most important legacy of this era in Jewish history is neither feel-good stories of idealism nor a story of mere despair. Rather, he says he hopes that An Unchosen People helps recover a different kind of history of political creativity. An Unchosen People rediscovers interwar Polish Jews as culturally and politically creative not out of ease, freedom, possibility, and agency, but out of desperation in the face of vulnerability, foreclosure, and limited resources.

This Website Uses Cookies.

This website uses cookies to improve user experience. By using our website you consent to all cookies in accordance with our Cookie Policy.

Trending Topics:

- Israel Independence Day is May 14

- Say Kaddish Daily

Jews in Hollywood, 1930-1950

American Jews and the making of the movie industry.

By Norman L. Friedman

Philip French’s The Movie Moguls and Nolan Zierold’s The Moguls give good overviews and collective/comparative portraits of the small group of top-level Jewish-born entrepreneurs who fashioned the [Hollywood] dream factories, Marcus Loew, Adolph Zukor, Sam Goldwyn, Carl Laemmle, the Selznicks, Jesse Lasky, William Fox, the Warner Brothers, Louis B. Mayer, B. P. Schulberg and Harry Cohn. Having either been born in America or come from Europe in their childhood or youth, most of the moguls could be classified as second-generation American Jews, from poor or modest-income families. They were exceptionally industrious and ambitious, and, interestingly, quite a few came to the motion picture industry from various retail trades, particularly the garment industry. Zukor and Loew, for example, began as furriers, Fox and Laemmle as clothing merchants, Goldwyn as a glove salesman. Control was enterprisingly gained over theaters and, later, over studios, linking distribution and production. Actor Lionel Barrymore celebrating his 61st birthday at MGM in August of 1939. Back, from left, Mickey Rooney, Robert Montgomery, Clark Gable, William Powell, Robert Taylor. Center-Louis B. Mayer. Front, from left-Norma Shearer, Barrymore and Rosalind Russell.(Dell Publications via Wikimedia Commons) The creation of the two industries was not utterly dissimilar. Both in clothing and motion pictures Jewish entrepreneurs, starting from a mass distribution base, created mass production industries for garments and entertainment. With daring and finesse, they organized innumerable individual skills (of sewing or photographing) for the vast market of voiceless consumers. The moguls, thus, brought to Hollywood certain business skills acquired in related retail trades and, by the 1930s, six of the eight major studios were Jewishly controlled and managed. In addition, persons of Jewish birth were prominent among the second and third level of business-oriented producers, managers, assistants, agents and lawyers. How Jewish Was Jewish Hollywood?

What was the shape of the formal or explicit religious Judaism and ethnic Jewishness practiced and expressed by Jewish Hollywood? During this period, almost no films were made about specifically Jewish settings, experiences, or characters. Though most of the moguls came from observant Jewish homes, and learned some Hebrew and/or had been bar mitzvahed, they tended, as adults, to live and think in a culturally assimilated lifestyle removed from the cultural content, activities or practices of the Jewish heritage, or of the affairs of the larger Los Angeles Jewish community. Theirs was a somewhat passive though unashamed Jewishness, comprised usually of the use of some Yiddish words, temple membership but infrequent attendance, and support for Jewish philanthropy. Screenwriter Ben Hecht has rather caustically characterized and explained the stance as follows:

He finds it convenient to forget his Jewishness in the high-class world into which he has vaulted. He is thus eager. to prove his Jewishness secretly by donations to Jews in distress. He will support a synagogue with large gifts for thirty years without ever entering it. The closest he comes to this secret Judaism to which he stubbornly lays claim is observing a few religious principles, such as not going to the races on Jewish holidays, or arranging for a rabbi to officiate (in English) at his funeral.

Louis Mayer, head of M-G-M, was probably fairly typical in this respect. Once away from the Orthodoxy of his Boston youth, he tended to treat his religion “rather casually;” he did belong to a temple, but rarely attended. Some, of course, were more disaffected. David Selznick, not wanting to be considered a Hollywood Jew, once told Hecht, “I’m an American and not a Jew.” Harry Cohn, of Columbia, avoided temples, and at his “nondenominational” funeral in 1958 no reference was made to his Jewish birth and origins. His biographer relates that:

One afternoon Louis B. Mayer spent an hour on the telephone before he was able to evoke a contribution from Cohn to Jewish Relief. Mayer used all his considerable powers of persuasion to appeal to Cohn’s loyalties as a Jew, but Cohn had none. After he committed himself to a sizable donation, Cohn complained to an aide, “Relief for the Jews! Somebody should start a fund for relief from the Jews. All the trouble in the world has been caused by Jews and Irishmen.”

While not very culturally Jewish, Jewish Hollywood was somewhat socially separate in structure, making up its own social circle (or circles, of various levels and roles in the pecking order) of Jewish friends and associates for job nepotism, art collecting, the country club, golf, gambling and even intra-colony marriage (such as that of Louis B. Mayer’s daughter to David Selznick).

The Importance of Being an Immigrant

If Jewish Hollywood had little explicit Judaism or Jewishness to contribute to those foundation years of sound films, what, then, was its motive power? Both Zierold and French more or less detect that there was something about its “immigrant-ness” that lay behind the achievements, strengths, and shortcomings.

First, their desire as immigrants or near-immigrants to be fully accepted as culturally assimilated “Americans,” “one hundred per cent Americans,” lent them an enthusiasm for the transmission, idealization, and creation of American popular culture. Through their movies, they presented to the world their own selective perception of aspects of American values and virtues.

Second, it has frequently been contended that, as immigrants becoming Americans, they had a special sense of, or “instinct” for, what the movie-goer wanted and liked, which was usually what they, as typical or, at least aspirant, mass Americans, wanted and liked. Cohn, for example, once ordered a three-syllable word to be taken out of a script because, “If I don’t know what it means, the average guy in a movie theater sure as hell won’t.” And he had a “foolproof” method to determine the quality of a film: “If my fanny squirms, it’s bad. If my fanny doesn’t squirm, it’s good. It’s as simple as that.” Goldwyn’s stomach was his guide. In retrospect, it appears that their intuitive judgments were correct more often than not.

This immigrant enthusiasm for American popular culture, and this understanding of mass American tastes, took different shapes and forms at the different “Jewish studios.” While M-G-M, for instance, under Mayer, turned out pictures that have been described as folksy, romantic, sentimental, glossy, “feminine” films for the middle class, the Warner Brothers, under Jack Lo Warner, produced “less ladylike” crime stories, melodramas, biographies, and “social conscience” films for and about the working class. Both sets of films were variations on themes of American popular culture, as seen through historical immigrants’ lenses.

Reprinted with permission from Judaism: A Quarterly Journal of Jewish Life and Thought.

Join Our Newsletter

Empower your Jewish discovery, daily

Discover More

American Jews

Black-Jewish Relations in America

Relations between African Americans and Jews have evolved through periods of indifference, partnership and estrangement.

Black Wedding: Marrying the Spanish Flu Away

This Jewish response to a devastating epidemic in the early 20th century drew on a mixture of Eastern European customs and inspired both fierce proponents and harsh critics.

Jewish Theater and Dance

Where To See Yiddish Theater Today

A guide to Yiddish performances and festivals around the world.

Jewish History

The Memory Map of the Jewish East End

A new digital resource allowing users to explore former sites of Jewish memory in East London went online this week. On it you will find audio interviews, photographs, and essays about more than 70 sites (we hope to include more in future) that consistently appear in people’s recollections of Jewish East London.

The memory map aims to create a lasting document of both the history and memory traces of the Jewish East End, and attempts to bring the stories and memories of this rapidly vanishing landscape to new audiences. The project is a collaboration between myself, Dr Duncan Hay, Professor Laura Vaughan, and Peter Guillery, from across four different research units based at the Bartlett School of Architecture (UCL): the Faculty for the Built Environment , the Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis , the Space Syntax Laboratory , and the Survey of London .

Without an expert guide it is almost impossible to get any sense of the vibrant Jewish past of East London. I became fascinated with this history after moving to the area in the 1990s, tracing the footsteps of my paternal grandparents Gedaliah and Malka Lichtenstein, who were Polish Jewish migrants who met and married in the Jewish East End in the 1920s. They were part of a later wave of Jewish refugees who settled in the area, after the East End had already become its own distinct Jewish quarter during the 1880s as tens of thousands of new arrivals came to London fleeing the pogroms and persecution in Russia and the Pale of Settlement. By 1900, over 95% of the population of Wentworth Street (the home of the world-famous Petticoat Lane market) were Jewish immigrants. From the Victorian era to the Second World War the Jewish East End thrived, street signs were written in Yiddish, over 100 synagogues and small steibels were established in the area, alongside a bustling commercial Jewish center with a complex network of self-supporting interconnected Jewish institutions. There was also a vibrant Jewish cultural life in the area with four dedicated Yiddish theatres, multiple Yiddish newspapers and journals, literary groups and societies, cinemas, dance halls and many active political groups including anarchists, Zionists and communists who met on street corners as well as place like the Workers Circle. Many of these disparate groups came together on the 4th October 1936, when Oswald Mosley, leader of the BUF (British Union of Fascists), tried to march his Blackshirts through the streets of East London. Thousands of Jewish migrants were joined by Irish dock workers and other left wing activists who blocked the march during the now legendary Battle of Cable Street.

The Second World War and its aftermath marked the beginning of the end of the Jewish East End. The place was so badly bombed during the war that most people who had been evacuated either did not want to come back or had nowhere to come back to. Whitechapel was filled with bombsites, abandoned buildings with boarded up windows, dusty and ruinous. The Jewish community was leaving in droves. Most that could left the East End, including my own grandparents who moved to Westcliff in Essex, or Whitechapel-on-sea as it was known back then due to the size of the Jewish community.

The glamour of the East End had long gone by the 1950s: the gigantic plush cinemas that could seat over a thousand people, the multiple theatres, Hollywood style photographic studios, European coffee houses and Jewish owned shops started to close down. By the 1960s the little synagogues were closing down. Around the same time a new group of migrants from Pakistan and Bangladesh were starting to establish themselves in the area. Former synagogues became clothing workshops. Kosher shops and restaurants started serving halal food. The East End of London was transforming itself once again.

In 1976 the building that had once been a Huguenot Chapel before it became the Spitalfields Great Synagogue (also known as the Machzike Hadath) was sold to the Bangladeshi community and became The Brick Lane Mosque. It holds up to 4,000 worshippers at a time and is now as packed on Ramadan as it once was on Yom Kippur. High on the wall, above the Fournier Street entrance, is the Latin inscription ‘Umbra Sumus’, which translates to ‘We are Shadows.’

Around this time a few individuals started to record the last remnants of the Jewish East End. David Jacobs, the British Jewish historian rescued many artefacts from abandoned synagogues in the area, which later formed the basis of the temporary Museum of the Jewish East End (which opened for a few years in the Sternberg Centre in North London and later merged with collections at the London Jewish Museum). Oral historian Alan Dein began collecting memories of former Jewish East Enders, which also became part of the first museum collection.

I moved to the area in the 1990s, searching for remnants of my own Jewish heritage, which led to books including Rodinskys Room (co-authored with Iain Sinclair, Granta 1999) and On Brick Lane (Penguin, 2008) inspired by the groundbreaking East End studies of Professor Bill Fishman, the first to put the story of Jewish East London on the map. Eventually I too became a tour guide of the Jewish East End. During all the years I spent walking around the place exploring the last remnants of Jewish East London I met many older Jewish residents who sometimes joined me for a walk around the area. They talked with great sadness and an acute sense of nostalgia about the Whitechapel of their youth, ‘The crowded Jewish centre of London’ a place bursting with life: ‘the stink and the wonderful smells’ of the lively markets. They remembered the Russian Vapour Baths where ‘the devout Hasidim with their sidelocks, long black coats and beards would wait to get into the steam baths before Friday night services.’ They described pre-war Whitechapel as one big working Jewish settlement.

When I first moved to the area thirty years ago there were other tangible remnants of former Jewish occupation in the area; the marks of a mezuzah on a doorpost, a faded name written in Yiddish above a boarded up shop, a traffic chocked star of David above a gentleman’s outfitters on the high street. There were even a few Jewish owned businesses and institutions still operating; some down at heel delicatessens, kosher eateries and bakeries, a smattering of functioning synagogues. Today only a few tangible traces remain, such as the facade of the former Jewish Soup Kitchen for the Jewish Poor, Nos. 17–19 Brune Street. Even the Jewish Memorial showroom in the area has recently closed down. Jewish Whitechapel has become a shadow realm, a theatre of memory invisible to the present-day visitor, impossible to navigate without an expert guide. Today only the faintest whispers of the rich Jewish past in the area remain, most are on the verge of disappearing or have disappeared completely.

This new interactive website brings together many recordings from my substantial archive of audio interviews with former and current Jewish residents of East London many of whom are sadly no longer with us, with testimony from the Sandys Row collection, new and archival photographs, original research produced collaboratively by the team, and essays from the Survey of London.

You can visit the map here: https://jewisheastendmemorymap.org

To start exploring just click on one of the coloured shapes, which have been placed on the location of sites of Jewish significance and colour coded into different themes, and information will automatically pop up about that site including audio clips, archival and contemporary photographs, historical data, excerpts from literature and historical essays.

Subject to further funding, we hope that this map will become a growing resource about the history of the Jewish East End. This project builds on the Survey of London Whitechapel project, with its emphasis on mapping buildings, architectural records, and people’s own contributed recollections and shows how mapping alongside recordings, historical photographs, written testimonies and formal historical records come together to build a richer picture of the past – mirroring the inter disciplinarity of our collaboration.

A Note on the Current Situation

In light of the Covid-19 pandemic, the team hope that the Memory Map will provide education and entertainment in this challenging time. Please share this resource widely, particularly with those who you think will find solace in the project.

If you have any queries about the project, please contact the team at [email protected].

15 Comments

My grandparents emigrated from Russia to the Brick Lane area before they finally moved to New York City in the early 1900s. I roamed around Whitechapel, trying to imagine what it was like for my grandmother’s family back then. Thanks for the vivid descriptions of the area. It helps me to understand what their lives were like then.

Hi not quite correct as to where people moved to. Very large numbers, including my parents, moved to Hackney. It’s been estimated that half the population in the 1950s in Hackney were Jewish.

I have just discovered this website. Thank you for this it’s fascinating. My great grandfather came to Blackfriars in 1865, we think he came from the USA after leaving Poland. He later moved to Ashwin Street in Dalston. My grandfather Benjamin was born in Blackfriars in 1866.i am researching my grandfather’s background, he became a theatre owner after experience in circus.

I want to correct an error. Wentworth Street is the CURRENT location of a very poor imitation of Petticoat Lane Market, which used to be just a SUNDAY market located along the length of Middlesex Street, which was renamed from Petticoat Lane in 1830. I remember it well from my childhood because my father was born just off “The Lane” and worked in the area all his life. When I was a child, my grandmother still lived in the flat where my Dad was born and whenever we visited on a Sunday, my face would be raw from all the affectionate cheek-grabbing by the stallholders who called out to my Dad as we passed, walking to the flat from Aldgate station.

Surprised you did not mention the pets market in Club row!

Is there a photo of the pharmacy that was at 58 we tworth Street in the 1990s

does anyone remember ziffs chicken abattoir in hassell st my brother in worked there in the sixties went there once with my dad the smell was something else

Can anyone please tell me if MURMAN STREET I think it came under Islington London was this a Jewish Area in the 30’s and BREWER STREET Islington N1. My maiden name is Harris and all relatives and my Mum and Dad are deceased so I can’t ask them. I trying to trace Family History. I know a bit.

My late dad Samuel was the son of Leah Rachel Ruebin nee Shapiro and Morris Ruebin originally Rock. My aunty Betty, dad’s sister told me the family house was bombed during world war 2. My grandparents married at Mile End synagogue. Aunty Betty told me that the Lyons coffee shop made my grandparents wedding reception. It is so sad they were poor. They were tailors and later went to live in Monmouthshire Wales. They had a boot making company. They later moved to Manchester where dad met my mum and they got married in the early 1960’s.

I would love to find out more information about any records which exist of my family when they lived in London. Dad was born in Stepney or Whitechapel . I had a relation in East London who was a Shapiro and he had a fruit shop. My aunty told me he called his wife Chilly. Dad also had Nyegate relations one of whom we met some years ago.

If anyone could give me any information where I can find more information about the time my family lived there I would be very grateful.

I am looking for information on my grandparents Leah Rachel nee Shapiro and Maurice Ruebin was Rog. My dad Sam was born in Hackney in Whitechapel in 1910. I think they lived on Burdet Street which was bombed during the blitz.

My parents were both born in the East End – my mother lived in Brick Lane and my father in Lucas Street. My mother’s father was Elijah Kominski who had a record shop under the bridge in Brick Lane and my father’s father, Herman Lament, was a tailor. Someone told me that Zeyde would put a gramophone out on the sidewalk on Sundays and the neighbours would come and dance.

My grandmother, Rosa Blank (nee Jacobs) also grew up in Lucas Street. Her father was a tailor. She married my grandfather, Joseph Blank / Blankleder who came from a family of musicians and had a music store.

My paternal grandparents, Rachel and Benjamin Mendes, lived at 18 Bell Lane.

60 years ago when l started working in London EC3 my lunch time was always spent a quick walk to Wentworth street, a Quick Look in the record shop, lunch the the nearby cafe, a short walk down Wentworth St and with about 20 mins left always walked back via Gaulston St making a stop at Barney’s (seafood) where the man always gave me some tail pieces of jellied eels free of charge. When my salary increase went in the same street towards Wentworth St. to visit a Jewish man who sold many different lengths of suit material that l had purchased and had suits made at his recommended trailers Fournier St who made amazing suits in less than a week from their tiny shop with no changing room, this included 1 or 2 fittings depending on when you delivered the material , great memories, am now 75 so possible these great people have since passed away , will always remember those great days and the people who l met on my journey,

I am searching for anyone who has any knowledge of my Father’s family from the EastEnd. My father’s name before he changed it by deed poll in the 1960s was Bobinsky. My Father Colin David Barnett had a sister Sonia. My grandparent’s names were Debby and Maurice. Other family members include Jack and Hetty. Dad was born in Whitechapel and grew up in Poplar. My Grandpa had a chip shop on Brick Lane, worked as a tailor and I believe a Policeman for a year. My father spent a year in a hospital in High Wickham where I understand his grandfather ran a synagogue. Dad was in the RAF based in Cardiff as an auxiliary nurse. My Nana Debbie was a seamstress. If anyone has any information please reach out to me at [email protected] . Other members of my family include Clive Rich (Simon Cowell’s lawyer). Thank you for your time.

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name and email address in this browser for the next time I comment.

Jewish Journal

Connect. inform. inspire., so long, democratic party.

- By Thane Rosenbaum

- Published May 12, 2024

Thane Rosenbaum

Not that my political affiliation is any of your business, but I thought I might share with you that after 46 years as a die-hard Democrat, I have alerted the New York State Board of Elections that I am now, officially, an Independent.

Honestly, I couldn’t take it anymore. My options, as a voter, are now more open than ever.

The past eight years have been one slow death march of the Democratic Party’s abandonment of its Jewish voting bloc. It coincided with a descent into an illiberal, ahistorical and morally misguided adherence to identity politics, intersectionality, CRT, DEI, anti-colonialism, and the social upheavals wrought by “political correctness.”

It has led to a wide assortment of pathologies, ranging from restrictions on free speech and open inquiry to the debasement of our immigration laws, the bedlam on our streets and college campuses, the desertion of foreign allies, the brainwashing of our youth, the wrecking of our economy, the upending of gender and sexual categories, and an appalling anti-Americanism that I surely have not seen in my lifetime.

Party leaders have taken for granted that Jewish Republicans are an anathema, and people like me, who identify with 19 th -century liberalism, have nowhere else to go. Believing that there is no risk of flight, they have consigned Jewish -Americans to a political party allied with those who would wipe Israel from the map (if these domestic haters could only find it on a map).

Those presumptions may turn out to be false. Jewish affiliation with Republican politics has already grown, and stands at 29%—even before some of the recent events that have alienated Jewish Democrats. And while there’s no actual party for Americans who eschew the two-party system altogether, I do not believe I will be alone this election as an unaffiliated voter.

To remain with the Democratic ticket would make me feel like a real donkey. I can live without an animal mascot representing independent voters (I suggest one that naturally stands apart from the herd). And I have reconciled myself to knowing that in 2022, New York banned any political party wishing to refer to itself as Independent.

Not being able to vote in the primaries is a small sacrifice. Standing on principle is more important, along with sending a message that the Democratic leadership already knows: it is no longer the party of FDR, JFK or LBJ. It has no affinity for Clintonian centrism, either. The Party has fast become a home for left-wing zealots for whom nothing matters more than pronoun usage, open borders, and emptying our prisons of overrepresented minorities.

The Democrats finally became the party that progressives and socialists wanted in electing Barack Obama. It was unfeasible for him, at the time, to implement the political transformation he had hoped his administration would bring. (Yes, I voted for him twice, even as I feared the generational damage it might inflict.)

Ironically, it was his politically more moderate vice president, Joe Biden, who would eventually accede to the Oval Office and take America in a direction that would make Bill Ayers, Pastor Jeremiah Wright and Reverend Louis Farrakhan proud.

For me, the breaking point came with Joe Biden’s shameful CNN interview where he made clear that the United States would not support Israel’s incursion into Rafah to route the remaining Hamas terrorists responsible for 10/7.

Let me get this straight: The United States devoted a decade to hunting down and assassinating Osama bin Laden, killing 250,000 Afghani and Iraqi civilians along the way. No condemning U.N. resolutions. No protests. No International Court of Justice proceedings. All throughout America’s War on Terror, Israel provided necessary intelligence and regional backup, and erected a 9/11 memorial—the only one outside the United States listing the names of all victims.

Yet, the Biden administration is withholding from Israel the necessary weaponry (already earmarked by Congress) with which to conduct its wholly justified military operations? Israel does not require Biden’s blessing. And the precision of the Rafah campaign will now be less precise.

Curiously, the president repeatedly acknowledged that 10/7 was an unprovoked attack for which Israel has a moral and legal right of self-defense, and that Hamas presents an existential threat that must be eradicated. Biden’s “ironclad” commitment to Israel has already gone limp. Apparently, unlike the United States, Israel must be denied its moral obligation to bring justice to its people and security to its borders. It can defend against missiles, but not dismantle them at the source.

Biden’s actions have given comfort to Hamas and its patron, Iran. Why should Hamas return hostages (some, Americans), if Biden is singularly focused on constraining Israeli military offenses?

Moreover, Biden just gave a shout-out to those ignorant college students and their Jew-hating, anti-American professors. Sorry, “Genocide Joe,” asserting your mojo and cultivating a youthful antisemitic constituency won’t help you come November.

For reasons only rabid progressives can explain, Palestinians, who are more like Hamas accomplices than true civilians, are more precious than the world’s other civilians. Is it because Jews aren’t permitted to win wars, especially against brown-skinned people? The Jewish state must always agree to ceasefires, perform humanitarian acts while fighting in self-defense, and sue for peace.

This betrayal has little to do with moral equivocation and everything to do with local politics. Biden will, apparently, do or say anything to woo the 600,000 Muslim voters of Michigan, and stay within the good graces of that dreadful Detroit Motown act, Bernie Sanders and the Squad.

Is it worth it, this backstabbing of Jewish-Americans, an important minority reliably loyal to the Democratic Party? Always true blue, as if the Party had nominated Moses as its standard bearer and Anne Frank as his running mate. The progressive perfidy is even more heartbreaking. Jews stood at the forefront of nearly every movement of social activism in the United States, from labor unions to civil liberties, feminism, civil rights, and gay rights.

Apparently, the reward for all those years of solidarity has been exclusion and antisemitism.

I am under no illusion that my departure from the Party will matter to anyone. After all, jettisoning Jewish white males is one of the objectives of its racial identity and rigid orthodoxy. Should moderates ever reclaim control from the Marxists and Islamists, give me a call.

In the end, Joe Biden picked the Muslims of Michigan over moral clarity, a coherent foreign policy, and love of country. Yes, he’s increasingly addled. But he well knows that Jewish-Americans, or Jewish-Israelis, are highly unlikely to ever burn an American flag and shout, “Death to America!”

Is there anything else he needs to know?

Thane Rosenbaum is a novelist, essayist, law professor and Distinguished University Professor at Touro University, where he directs the Forum on Life, Culture & Society. He is the legal analyst for CBS News Radio. His most recent book is titled “Saving Free Speech … From Itself,” and his forthcoming book is titled, “Beyond Proportionality: Is Israel Fighting a Just War in Gaza?”

Did you enjoy this article?

You'll love our roundtable., editor's picks.

Israel and the Internet Wars – A Professional Social Media Review

The Invisible Student: A Tale of Homelessness at UCLA and USC

What Ever Happened to the LA Times?

Who Are the Jews On Joe Biden’s Cabinet?

You’re Not a Bad Jewish Mom If Your Kid Wants Santa Claus to Come to Your House

No Labels: The Group Fighting for the Political Center

Latest articles.

Defiant, Soulful and Electrifying: Israel’s Eden Golan Shines at Eurovision with Song, “Hurricane”

Did Graduation Disruptors Move Seinfeld and Others Closer to Israel?

Is Anti-Zionism Antisemitic? It Doesn’t Matter

Israeli Singer Eden Golan Advances to Grand Final of Eurovision

Brave-ish wins Literary Titan Gold Book Award

From unexpected offer to cannes triumph: the jewish succession, food memories – and recipes – for mother’s day, a g-d squad and a perfect herby salmon.

Proud Jews, Despite Everything

History reminds us that we ignore antisemitism at our own risk.

ADL, Brandeis Center File Complaints Against Occidental, Pomona College Over Antisemitism

The atmosphere at both schools is so toxic, Jewish students are transferring out.

Beit Issie Shapiro’s Global Impact: Transforming Lives and Communities

The organization which is based in Israel provides innovative therapies and state-of-the-art services for children and adults.

Remembering Joe Lieberman

The shloshim (thirty-day) mourning period for Senator Joseph Lieberman was completed on April 27, but I miss him more than ever.

Let There Be Love – A poem for Parsha Kedoshim

Let love be love …

Spielberg Says Antisemitism Is “No Longer Lurking, But Standing Proud” Like 1930s Germany

Young Actress Juju Brener on Her “Hocus Pocus 2” Role

Behind the Scenes of “Jeopardy!” with Mayim Bialik

Chef Katie Chin: Heritage, Chinese Cooking and Chocolate-Raspberry Wontons

Chico Menashe: Asif: Culinary Institute of Israel, Cooking with Chutzpah and The Open Kitchen Project

More news and opinions than at a shabbat dinner, right in your inbox..

Window on world of Jews in 1930s Poland

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

Poland’s Jews were nearly wiped out in the Nazi Holocaust, then the communists who ruled the country for decades after World War II waged anti-Semitic campaigns and made Jewish history a taboo topic.

But a new documentary draws on a patchwork of amateur camera footage shot mostly by American Jews visiting relatives in the 1930s in Polish towns, providing a window into what once was.

It makes its debut in Canada, Germany and Ukraine in Polish this month, and an English version will be ready for the U.S. market later this year, Polish producer Miroslaw Bork said.

“Po-Lin, Slivers of Memory” was conceived by Polish camerawoman Jolanta Dylewska, who was inspired to make the 80-minute film after she came across one of the home movies in Jerusalem archives in 1996 while working on another project.

“That movie had an enormous emotional value for me,” Dylewska said. “People in it reacted with great warmth to the camera because it was in the hands of a family member, a close person. The camera transported that warmth onto me, watching the film 60 years later.”

The word “Po-lin” in the title is Hebrew for “You will rest here” or a “Place of safe refuge,” but it also means “Poland.” It was Poland where Jews expelled from other parts of Europe settled during the Middle Ages, making it indeed a place of refuge for 1,000 years.

But the specter of the Holocaust to come haunts the film. At one point, the narrator notes that the children in the movie have only 10 more years to live.

Only a few hundred thousand of Poland’s prewar population of 3.5 million survived the Nazi genocide.

“The message of loss is in the end stronger because we see what has been lost,” Bork said.

The $400,000 Polish-German co-production opened in Polish art-house cinemas in November.

Leaving a recent showing that she attended on her sister’s recommendation, 24-year-old Malgosia Kruczek said that as a non-Jew, she found the film “invaluable.”

“These are the people who lived here, who lived together with us -- exotic, but also very close,” the Warsaw University student said.

After finding the initial home movie, Dylewska found more footage in Israeli and American archives, and added commentary -- based on Jewish history books -- in Polish with English subtitles.

At the same time, she said she took great care to preserve the original atmosphere of the black-and-white films in hopes that “the viewers will carry these people in their memories.”

She also filmed the places from the home movies as they are today, and found witnesses to talk about their former Jewish neighbors and friends.

“It moves you to the core of your soul,” Israeli Embassy spokesman Michal Sobelman said. “And it fits into this trend in Poland’s culture now of searching for traces of former Polish citizens, the traces of Jews.”

More to Read

Review: With Robbie in pink and Gosling in mink, ‘Barbie’ (wink-wink) will make you think

July 18, 2023

Why ‘Downton Abbey’ had to say goodbye to that iconic character

May 26, 2022

Here’s the true story behind the unique bond of ‘The Silent Twins’

Oct. 2, 2022

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

Roger Corman, independent cinema pioneer and king of B movies, dead at 98

May 11, 2024

Company Town

Shari Redstone was poised to make Paramount a Hollywood comeback story. What happened?

Review: ‘Catching Fire: The Story of Anita Pallenberg’ supplies belated respect for a rock muse

May 10, 2024

Review: Coolly argued but driven by fury, ‘Power’ examines the history of American policing

Advertisement

Supported by

House Republicans Clash With Leaders of Public Schools Over Antisemitism Claims

Politicians said educators had not done enough. But the New York chancellor said members were trying to elicit “gotcha moments” rather than stop antisemitism.

- Share full article

By Dana Goldstein , Troy Closson and Michael Levenson

Dana Goldstein reported from the House committee hearing room.

A Republican-led House committee turned its attention to three of the most politically liberal school districts in the country on Wednesday, accusing them of tolerating antisemitism, but the district leaders pushed back forcefully, defending their schools.

The hearing was the third by House Republicans to expose what they see as a pro-Palestinian agenda gripping schools and college campuses since the start of the Israel-Hamas war.

During the contentious two-hour session, Republicans accused the district leaders — from New York City, Berkeley, Calif., and Montgomery County, Md. — of “turning a blind eye” to antisemitism.

Enikia Ford Morthel, the superintendent of Berkeley schools, acknowledged some incidents in her schools, but pointedly stated that “antisemitism is not pervasive in Berkeley Unified School District.”

And David C. Banks, the New York City schools chancellor, said the repeatedly hostile questions from the panel suggested it was trying to elicit “gotcha moments” rather than solve the problem of antisemitism.