- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 6, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

John Cabot (or Giovanni Caboto, as he was known in Italy) was an Italian explorer and navigator who was among the first to think of sailing westward to reach the riches of Asia. Though the details of his life and expeditions are subject to debate, by the late 1490s he was living in England, where he gained a commission from King Henry VII to make an expedition across the Atlantic. He set sail in May 1497 and made landfall in late June, probably in modern-day Canada. After returning to England to report his success, Cabot departed on a final expedition in 1498, but was allegedly never seen again.

Giovanni Caboto was born circa 1450 in Genoa, and moved to Venice around 1461; he became a Venetian citizen in 1476. Evidence suggests that he worked as a merchant in the spice trade of the Levant, or eastern Mediterranean, and may have traveled as far as Mecca, then an important trading center for Oriental and Western goods.

He studied navigation and map-making during this period, and read the stories of Marco Polo and his adventures in the fabulous cities of Asia. Similar to his countryman Christopher Columbus , Cabot appears to have become interested in the possibility of reaching the rich gold, silk, gem and spice markets of Asia by sailing in a westward direction.

Did you know? John Cabot's landing in 1497 is generally thought to be the first European encounter with the North American continent since Leif Eriksson and the Vikings explored the area they called Vinland in the 11th century.

For the next several decades, Cabot’s exact activities are unknown; he may have been forced to leave Venice because of outstanding debts. He then spent several years in Valencia and Seville, Spain, where he worked as a maritime engineer with varying degrees of success.

Cabot may have been in Valencia in 1493, when Columbus passed through the city on his way to report to the Spanish monarchs the results of his voyage (including his mistaken belief that he had in fact reached Asia).

By late 1495, Cabot had reached Bristol, England, a port city that had served as a starting point for several previous expeditions across the North Atlantic. From there, he worked to convince the British crown that England did not have to stand aside while Spain took the lead in exploration of the New World , and that it was possible to reach Asia on a more northerly route than the one Columbus had taken.

First and Second Voyages

In 1496, King Henry VII issued letters patent to Cabot and his son, which authorized them to make a voyage of discovery and to return with goods for sale on the English market. After a first, aborted attempt in 1496, Cabot sailed out of Bristol on the small ship Matthew in May 1497, with a crew of about 18 men.

Cabot’s most successful expedition made landfall in North America on June 24; the exact location is disputed, but may have been southern Labrador, the island of Newfoundland or Cape Breton Island. Reports about their exploration vary, but when Cabot and his men went ashore, he reportedly saw signs of habitation but few if any people. He took possession of the land for King Henry, but hoisted both the English and Venetian flags.

Grand Banks

Cabot explored the area and named various features of the region, including Cape Discovery, Island of St. John, St. George’s Cape, Trinity Islands and England’s Cape. These may correspond to modern-day places located around what became known as Cabot Strait, the 60-mile-wide channel running between southwestern Newfoundland and northern Cape Breton Island.

Like Columbus, Cabot believed that he had reached Asia’s northeast coast. He returned to Bristol in August 1497 with extremely favorable reports of the exploration. Among his discoveries was the rich fishing grounds of the Grand Banks off the coast of Canada, where his crew was allegedly able to fill baskets with cod by simply dropping the baskets into the water.

John Cabot’s Final Voyage

In London in late 1497, Cabot proposed to King Henry VII that he set out on another expedition across the north Atlantic. This time, he would continue westward from his first landfall until he reached the island of Cipangu ( Japan ). In February 1498, the king issued letters patent for the second voyage, and that May Cabot set off once again from Bristol, but this time with five ships and about 300 men.

The exact fate of the expedition has not been established, but by July one of the ships had been damaged and sought anchorage in Ireland. Reportedly the other four ships continued westward. It was believed that the ships had been caught in a severe storm, and by 1499, Cabot himself was presumed to have perished at sea.

Some evidence, however, suggests that Cabot and some members of his crew may have stayed in the New World; other documents suggest that he and his crew returned to England at some point. A Spanish map from 1500 includes the northern coast of North America with English place names and the notation “the sea discovered by the English.”

What Did John Cabot Discover?

In addition to laying the groundwork for British land claims in Canada, his expeditions proved the existence of a shorter route across the northern Atlantic Ocean, which would later facilitate the establishment of other British colonies in North America .

One of John Cabot's sons, Sebastian, was also an explorer who sailed under the flags of England and Spain.

John Cabot. Royal Museums Greenwich . Who Was John Cabot? John Cabot University . John Cabot. The Canadian Encyclopedia .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Native Americans

- Age of Exploration

- Revolutionary War

- Mexican-American War

- War of 1812

- World War 1

- World War 2

- Family Trees

- Explorers and Pirates

John Cabot Facts, Voyage, and Accomplishments

Published: Jul 25, 2016 · Modified: Nov 11, 2023 by Russell Yost · This post may contain affiliate links ·

John Cabot was a Genoese navigator and explorer whose 1497 discovery of parts of North America under the commission of Henry VII of England is commonly held to have been the first European exploration of the mainland of North America since the Norse Vikings' visits to Vinland in the eleventh century.

It would also be one of the last times, until Queen Elizabeth, that England would set foot in the New World.

John Cabot Facts: Early Life

John cabot facts: england and expeditions, john cabot facts: historical thoughts, online resources.

He may have been born slightly earlier than 1450, which is the approximate date most commonly given for his birth.

In 1471, Caboto was accepted into the religious confraternity of St John the Evangelist. Since this was one of the city's prestigious confraternities, his acceptance suggests that he was already a respected member of the community.

Following his gaining full Venetian citizenship in 1476, Caboto would have been eligible to engage in maritime trade, including the trade to the eastern Mediterranean that was the source of much of Venice's wealth.

A 1483 document refers to his selling a slave in Crete whom he had acquired while in the territories of the Sultan of Egypt, which then comprised most of what is now Palestine, Syria, and Lebanon.

Cabot is mentioned in many Venetian records of the 1480s. These indicate that by 1484, he was married to Mattea and already had at least two sons.

Cabot's sons are Ludovico, Sebastian, and Sancto. The Venetian sources contain references to Cabot's being involved in house building in the city. He may have relied on this experience when seeking work later in Spain as a civil engineer.

Cabot appears to have gotten into financial trouble in the late 1480s and left Venice as an insolvent debtor by 5 November 1488.

He moved to Valencia, Spain, where his creditors attempted to have him arrested. While in Valencia, John Cabot proposed plans for improvements to the harbor. These proposals were rejected.

Early in 1494, he moved on to Seville, where he proposed, was contracted to build, and, for five months, worked on the construction of a stone bridge over the Guadalquivir River. This project was abandoned following a decision of the City Council on 24 December 1494.

After this, Cabot appears to have sought support from the Iberian crowns of Seville and Lisbon for an Atlantic expedition before moving to London to seek funding and political support. He likely reached England in mid-1495.

Like other Italian explorers, including Christopher Columbus , Cabot led an expedition on commission to another European nation, in his case, England.

Cabot planned to depart to the west from a northerly latitude where the longitudes are much closer together and where, as a result, the voyage would be much shorter. He still had an expectation of finding an alternative route to China.

On 5 March 1496, Henry VII gave Cabot and his three sons letters patent with the following charge for exploration:

...free authority, faculty, and power to sail to all parts, regions, and coasts of the eastern, western, and northern sea, under our banners, flags, and ensigns, with five ships or vessels of whatsoever burden and quality they may be, and with so many and with such mariners and men as they may wish to take with them in the said ships, at their own proper costs and charges, to find, discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of heathens and infidels, in whatsoever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians.

Those who received such patents had the right to assign them to third parties for execution. His sons are believed to have still been under the age of 18

Cabot went to Bristol to arrange preparations for his voyage. Bristol was the second-largest seaport in England. From 1480 onward, it supplied several expeditions to look for Hy-Brazil. According to Celtic legend, this island lay somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean. There was a widespread belief among merchants in the port that Bristol men had discovered the island at an earlier date but then lost track of it.

Cabot's first voyage was little recorded. Winter 1497/98 letter from John Day (a Bristol merchant) to an addressee believed to be Christopher Columbus refers briefly to it but writes mostly about the second 1497 voyage. He notes, "Since your Lordship wants information relating to the first voyage, here is what happened: he went with one ship, his crew confused him, he was short of supplies and ran into bad weather, and he decided to turn back." Since Cabot received his royal patent in March 1496, it is believed that he made his first voyage that summer.

What is known as the "John Day letter" provides considerable information about Cabot's second voyage. It was written during the winter of 1497/8 by Bristol merchant John Day to a man who is likely Christopher Columbus . Day is believed to have been familiar with the key figures of the expedition and thus able to report on it.

If the lands Cabot had discovered lay west of the meridian laid down in the Treaty of Tordesillas, or if he intended to sail further west, Columbus would likely have believed that these voyages challenged his monopoly rights for westward exploration.

Leaving Bristol, the expedition sailed past Ireland and across the Atlantic, making landfall somewhere on the coast of North America on 24 June 1497. The exact location of the landfall has long been disputed, with different communities vying for the honor.

Cabot is reported to have landed only once during the expedition and did not advance "beyond the shooting distance of a crossbow." Pasqualigo and Day both state that the expedition made no contact with any native people; the crew found the remains of a fire, a human trail, nets, and a wooden tool.

The crew appeared to have remained on land just long enough to take on fresh water; they also raised the Venetian and Papal banners, claiming the land for the King of England and recognizing the religious authority of the Roman Catholic Church. After this landing, Cabot spent some weeks "discovering the coast," with most "discovered after turning back."

On return to Bristol, Cabot rode to London to report to the King.

On 10 August 1497, he was given a reward of £10 – equivalent to about two years' pay for an ordinary laborer or craftsman. The explorer was feted; Soncino wrote on 23 August that Cabot "is called the Great Admiral and vast honor is paid to him and he goes dressed in silk and these English run after him like mad."

Such adulation was short-lived, for over the next few months, the King's attention was occupied by the Second Cornish Uprising of 1497, led by Perkin Warbeck.

Once Henry's throne was secure, he gave more thought to Cabot. On 26 September, just a few days after the collapse of the revolt, the King made an award of £2 to Cabot. In December 1497, the explorer was awarded a pension of £20 per year, and in February 1498, he was given a patent to help him prepare a second expedition.

In March and April, the King also advanced a number of loans to Lancelot Thirkill of London, Thomas Bradley, and John Cair, who were to accompany Cabot's new expedition.

Cabot departed with a fleet of five ships from Bristol at the beginning of May 1498, one of which had been prepared by the King. Some of the ships were said to be carrying merchandise, including cloth, caps, lace points, and other "trifles."

This suggests that Cabot intended to engage in trade on this expedition. The Spanish envoy in London reported in July that one of the ships had been caught in a storm and been forced to land in Ireland but that Cabot and the other four ships had continued on.

For centuries, no other records were found (or at least published) that relate to this expedition; it was long believed that Cabot and his fleet were lost at sea. But at least one of the men scheduled to accompany the expedition, Lancelot Thirkill of London, is recorded as living in London in 1501.

The historian Alwyn Ruddock worked on Cabot and his era for 35 years. She had suggested that Cabot and his expedition successfully returned to England in the spring of 1500. She claimed their return followed an epic two-year exploration of the east coast of North America, south into the Chesapeake Bay area and perhaps as far as the Spanish territories in the Caribbean. Ruddock suggested Fr. Giovanni Antonio de Carbonariis and the other friars who accompanied the 1498 expedition had stayed in Newfoundland and founded a mission.

If Carbonariis founded a settlement in North America, it would have been the first Christian settlement on the continent and may have included a church, the only medieval church to have been built there.

The Cabot Project at the University of Bristol was organized in 2009 to search for the evidence on which Ruddock's claims rest, as well as to undertake related studies of Cabot and his expeditions.

The lead researchers on the project, Evan Jones and Margaret Condon, claim to have found further evidence to support aspects of Ruddock's case, particularly in relation to the successful return of the 1498 expedition to Bristol.

They have located documents that appear to place John Cabot in London by May 1500 but have yet to publish their documentation.

- John Cabot's Wikipedia Page

- Cabot Project

- Find a Grave: John Cabot Memorial

- John Cabot Study Guide

- The History Junkie's Guide to Famous Explorers

- The History Junkie's Guide to Colonial America

Explorer John Cabot made a British claim to land in Canada, mistaking it for Asia, during his 1497 voyage on the ship Matthew.

(1450-1500)

Who Was John Cabot?

John Cabot was a Venetian explorer and navigator known for his 1497 voyage to North America, where he claimed land in Canada for England. After setting sail in May 1498 for a return voyage to North America, he disappeared and Cabot's final days remain a mystery.

Cabot was born Giovanni Caboto around 1450 in Genoa, Italy. Cabot was the son of a spice merchant, Giulio Caboto. At age 11, the family moved from Genoa to Venice, where Cabot learned sailing and navigation from Italian seamen and merchants.

Discoveries

In 1497, Cabot traveled by sea from Bristol to Canada, which he mistook for Asia. Cabot made a claim to the North American land for King Henry VII of England , setting the course for England's rise to power in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Cabot’s Route

Like Columbus, Cabot believed that sailing west from Europe was the shorter route to Asia. Hearing of opportunities in England, Cabot traveled there and met with King Henry VII, who gave him a grant to "seeke out, discover, and finde" new lands for England. In early May of 1497, Cabot left Bristol, England, on the Matthew , a fast and able ship weighing 50 tons, with a crew of 18 men. Cabot and his crew sailed west and north, under Cabot's belief that the route to Asia would be shorter from northern Europe than Columbus's voyage along the trade winds. On June 24, 1497, 50 days into the voyage, Cabot landed on the east coast of North America.

The precise location of Cabot’s landing is subject to controversy. Some historians believe that Cabot landed at Cape Breton Island or mainland Nova Scotia. Others believe he may have landed at Newfoundland, Labrador or even Maine. Though the Matthew 's logs are incomplete, it is believed that Cabot went ashore with a small party and claimed the land for the King of England.

In July 1497, the ship sailed for England and arrived in Bristol on August 6, 1497. Cabot was soon rewarded with a pension of £20 and the gratitude of King Henry VII.

Wife and Kids

In 1474, Cabot married a young woman named Mattea. The couple had three sons: Ludovico, Sancto and Sebastiano. Sebastiano would later follow in his father’s footsteps, becoming an explorer in his own right.

Death and Legacy

It is believed Cabot died sometime in 1499 or 1500, but his fate remains a mystery. In February 1498, Cabot was given permission to make a new voyage to North America; in May of that year, he departed from Bristol, England, with five ships and a crew of 300 men. The ships carried ample provisions and small samplings of cloth, lace points and other "trifles," suggesting an expectation of fostering trade with Indigenous peoples. En route, one ship became disabled and sailed to Ireland, while the other four ships continued on. From this point, there is only speculation as to the fate of the voyage and Cabot.

For many years, it was believed that the ships were lost at sea. More recently, however, documents have emerged that place Cabot in England in 1500, laying speculation that he and his crew actually survived the voyage. Historians have also found evidence to suggest that Cabot's expedition explored the eastern Canadian coast, and that a priest accompanying the expedition might have established a Christian settlement in Newfoundland.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: John Cabot

- Birth Year: 1450

- Birth City: Genoa

- Birth Country: Italy

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Explorer John Cabot made a British claim to land in Canada, mistaking it for Asia, during his 1497 voyage on the ship Matthew.

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- John Cabot was inspired by the discoveries of Bartolomeu Dias and Christopher Columbus.

- Cabot's youngest son also became an explorer in his own right

- Death Year: 1500

- Sayled in this tracte so farre towarde the weste, that the Ilande of Cuba bee on my lefte hande, in manere in the same degree of longitude.

European Explorers

Christopher Columbus

10 Famous Explorers Who Connected the World

Sir Walter Raleigh

Ferdinand Magellan

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo

Leif Eriksson

Vasco da Gama

Bartolomeu Dias

Giovanni da Verrazzano

Jacques Marquette

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

Search The Canadian Encyclopedia

Enter your search term

Why sign up?

Signing up enhances your TCE experience with the ability to save items to your personal reading list, and access the interactive map.

- MLA 8TH EDITION

- Hunter, Douglas . "John Cabot". The Canadian Encyclopedia , 19 May 2017, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot. Accessed 24 April 2024.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , 19 May 2017, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot. Accessed 24 April 2024." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- APA 6TH EDITION

- Hunter, D. (2017). John Cabot. In The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- CHICAGO 17TH EDITION

- Hunter, Douglas . "John Cabot." The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published January 07, 2008; Last Edited May 19, 2017.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published January 07, 2008; Last Edited May 19, 2017." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- TURABIAN 8TH EDITION

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "John Cabot," by Douglas Hunter, Accessed April 24, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "John Cabot," by Douglas Hunter, Accessed April 24, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-cabot" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Article by Douglas Hunter

Published Online January 7, 2008

Last Edited May 19, 2017

Early Years in Venice

John Cabot had a complex and shadowy early life. He was probably born before 1450 in Italy and was awarded Venetian citizenship in 1476, which meant he had been living there for at least fifteen years. People often signed their names in different ways at this time, and Cabot was no exception. In one 1476 document he identified himself as Zuan Chabotto, which gives a clue to his origins. It combined Zuan, the Venetian form for Giovanni, with a family name that suggested an origin somewhere on the Italian peninsula, since a Venetian would have spelled it Caboto. He had a Venetian wife, Mattea, and three sons, one of whom, Sebastian, rose to the rank of pilot-major of Spain for the Indies trade. Cabot was a merchant; Venetian records identify him as a hide trader, and in 1483 he sold a female slave in Crete. He was also a property developer in Venice and nearby Chioggia.

Cabot in Spain

In 1488, Cabot fled Venice with his family because he owed prominent people money. Where the Cabot family initially went is unknown, but by 1490 John Cabot was in Valencia, Spain, which like Venice was a city of canals. In 1492, he partnered with a Basque merchant named Gaspar Rull in a proposal to build an artificial harbour for Valencia on its Mediterranean coast. In April 1492, the project captured the enthusiasm of Fernando (Ferdinand), king of Aragon and husband of Isabel, queen of Castille, who together ruled what is now a unified Spain. The royal couple had just agreed to send Christopher Columbus on his now-famous voyage to the Americas. In the autumn of 1492, Fernando encouraged the governor-general of Valencia to find a way to finance Cabot’s harbour scheme. However, in March 1493, the council of Valencia decided it could not fund Cabot’s plan. Despite Fernando’s attempt to move the project forward that April, the scheme collapsed.

Cabot disappeared from the historical record until June 1494, when he resurfaced in another marine engineering plan dear to the Spanish monarchs. He was hired to build a fixed bridge link in Seville to its maritime centre, the island of Triana in the Guadalquivir River, which otherwise was serviced by a troublesome floating one. Though Columbus had reached the Americas, he believed he had found land on the eastern edge of Asia, and Seville had been chosen as the headquarters of what Spain imagined was a lucrative transatlantic trade route. Cabot’s assignment thus was an important one, but something went wrong. In December 1494, a group of leading citizens of Seville gathered, unhappy with Cabot’s lack of progress, given the funds he had been provided. At least one of them thought he should be banished from the city. By then, Cabot probably had left town.

Cabot in England

Following the demise of Cabot’s Seville bridge project, the marine engineer again disappeared from the historical record. In March 1496 he resurfaced, this time as the commander of a proposed westward voyage under the flag of the King of England, Henry VII. Although there is no documentary proof, during Cabot’s absence from the historical record, between April 1493 and June 1494, he could have sailed with Columbus’s second voyage to the Caribbean. Most of the names of the over 1,000 people who accompanied Columbus weren’t recorded; however, Cabot could have been among the marine engineers on the voyage’s 17 ships who were expected to construct a harbour facility in what is now Haiti. Had Cabot been present on this journey, Henry VII would have had some basis to believe the would-be Venetian explorer could make a similar voyage to the far side of the Atlantic. It would help explain why Henry VII hired Cabot, a foreigner with a problematic résumé and no known nautical expertise, to make such a journey.

On 5 March 1496, Henry awarded Cabot and his three sons a generous letters patent, a document granting them the right to explore and exploit areas unknown to Christian monarchs. The Cabots were authorized to sail to “all parts of the eastern, western and northern sea, under our banners, flags and ensigns,” with as many as five ships, manned and equipped at their own expense. The Cabots were to “find, discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of heathens and infidels, in whatsoever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians.” The Cabots would serve as Henry’s “vassals, and governors lieutenants and deputies” in whatever lands met the criteria of the patent, and they were given the right to “conquer, occupy and possess whatsoever towns, castles, cities and islands by them discovered.” With the letters patent, the Cabots could secure financial backing. Two payments were made in April and May 1496 to John Cabot by the House of Bardi (a family of Florentine merchants) to fund his search for “the new land,” suggesting his investors thought he was looking for more than a northern trade route to Asia.

First Voyage (1496)

Cabot’s first voyage departed Bristol, England, in 1496. Sailing westward in the north Atlantic was no easy task. The prevailing weather patterns track from west to east, and ships of Cabot’s time could scarcely sail toward the wind. No first-hand accounts of Cabot’s first attempt to sail west survive. Historians only know that it was a failure, with Cabot apparently rebuffed by stormy weather.

Second Voyage (1497)

Cabot mounted a second attempt from Bristol in May 1497, using a ship called the Matthew . It may have been a happy coincidence that its name was the English version of Cabot’s wife’s name, Mattea. There are no records of the ship’s individual crewmembers, and all the accounts of the voyage are second-hand — a remarkable lack of documentation for a voyage that would be the foundation of England’s claim to North America.

Historians have long debated exactly where Cabot explored. The most authoritative report of his journey was a letter by a London merchant named Hugh Say. Written in the winter of 1497-98, but only discovered in Spanish archives in the mid-1950s, Say’s letter (written in Spanish) was addressed to a “great admiral” in Spain who may have been Columbus.

The rough latitudes Say provided suggest Cabot made landfall around southern Labrador and northernmost Newfoundland , then worked his way southeast along the coast until he reached the Avalon Peninsula , at which point he began the journey home. Cabot led a fearful crew, with reports suggesting they never ventured more than a crossbow’s shot into the land. They saw two running figures in the woods that might have been human or animal and brought back an unstrung bow “painted with brazil,” suggesting it was decorated with red ochre by the Beothuk of Newfoundland or the Innu of Labrador. He also brought back a snare for capturing game and a needle for making nets. Cabot thought (wrongly) there might be tilled lands, written in Say’s letter as tierras labradas , which may have been the source of the name for Labrador. Say also said it was certain the land Cabot coasted was Brasil, a fabled island thought to exist somewhere west of Ireland.

Others who heard about Cabot’s voyage suggested he saw two islands, a misconception possibly resulting from the deep indentations of Newfoundland’s Conception and Trinity Bays, and arrived at the coast of East Asia. Some believed he had reached another fabled island, the Isle of Seven Cities, thought to exist in the Atlantic.

There were also reports Cabot had found an enormous new fishery. In December 1497, the Milanese ambassador to England reported hearing Cabot assert the sea was “swarming with fish, which can be taken not only with the net, but in baskets let down with a stone.” The fish of course were cod , and their abundance on the Grand Banks later laid the foundation for Newfoundland’s fishing industry.

Third Voyage (1498)

Henry VII rewarded Cabot with a royal pension on December 1497 and a renewed letters patent in February 1498 that gave him additional rights to help mount the next voyage. The additional rights included the ability to charter up to six ships as large as 200 tons. The voyage was again supposed to be mounted at Cabot’s expense, although the king personally invested in one participating ship. Despite reports from the 1497 voyage of masses of fish, no preparations were made to harvest them.

A flotilla of probably five ships sailed in early May. What became of it remains a mystery. Historians long presumed, based on a flawed account by the chronicler Polydore Vergil, that all the ships were lost, but at least one must have returned. A map made by Spanish cartographer Juan de la Cosa in 1500 — one of the earliest European maps to incorporate the Americas — included details of the coastline with English place names, flags and the notation “the sea discovered by the English.” The map suggests Cabot’s voyage ventured perhaps as far south as modern New England and Long Island.

Cabot’s royal pension did continue to be paid until 1499, but if he was lost on the 1498 voyage, it may only have been collected in his absence by one of his sons, or his widow, Mattea.

Despite being so poorly documented, Cabot’s 1497 voyage became the basis of English claims to North America. At the time, the westward voyages of exploration out of Bristol between 1496 and about 1506, as well as one by Sebastian Cabot around 1508, were probably considered failures. Their purpose was to secure trade opportunities with Asia, not new fishing grounds, which not even Cabot was interested in, despite praising the teeming schools. Instead of trade with Asia, Cabot and his Bristol successors found an enormous land mass blocking the way and no obvious source of wealth.

- Newfoundland and Labrador

Further Reading

Douglas Hunter, The Race to the New World: Christopher Columbus, John Cabot and a Lost History of Discovery (2012).

External Links

Heritage Newfoundland and Labrador A biography of John Cabot from this site sponsored by Memorial University.

Dictionary of Canadian Biography An account of John Cabot’s life from the Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

Recommended

Giovanni da verrazzano, jacques cartier.

Sir Humphrey Gilbert: Elizabethan Explorer

Find out how Cabot helped kick-start England's transatlantic voyages of discovery

Italian explorer, John Cabot, is famed for discovering Newfoundland and was instrumental in the development of the transatlantic trade between England and the Americas.

Although not born in England, John Cabot led English ships on voyages of discovery in Tudor times. John Cabot (about 1450–98) was an experienced Italian seafarer who came to live in England during the reign of Henry VII. In 1497 he sailed west from Bristol hoping to find a shorter route to Asia, a land believed to be rich in gold, spices and other luxuries. After a month, he discovered a 'new found land', today known as Newfoundland in Canada. Cabot is credited for claiming North America for England and kick-starting a century of English transatlantic exploration.

Why did Cabot come to England?

Born in Genoa around 1450, Cabot's Italian name was Giovanni Caboto. He had read of fabulous Chinese cities in the writings of Marco Polo and wanted to see them for himself. He hoped to reach them by sailing west, across the Atlantic.

Like Christopher Columbus, Cabot found it very difficult to convince backers to pay for the ships he needed to test out his ideas about the world. After failing to persuade the royal courts of Europe, he arrived with his family in 1484, to try to persuade merchants in London and Bristol to pay for his planned voyage. Before he set off, Cabot heard that Columbus had sailed west across the Atlantic and reached land. At the time, everyone believed that this land was the Indies, or Spice Islands.

Why did King Henry VII agree to help to pay for Cabot's expedition?

If Cabot’s predictions about the new route were right, he wouldn’t be the only one to profit. King Henry VII would also take his share. Everybody believed that Cathay and Cipangu (China and Japan) were rich in gold, gems, spices and silks. If Asia had been where Cabot thought it was, it would have made England the greatest trading centre in the world for goods from the east.

What did Cabot find on his voyage?

John Cabot's ship, the Matthew , sailed from Bristol with a crew of 18 in 1497. After a month at sea, he landed and took the area in the name of King Henry VII. Cabot had reached one of the northern capes of Newfoundland. His sailors were able to catch huge numbers of cod simply by dipping baskets into the water. Cabot was rewarded with the sum of £10 by the king, for discovering a new island off the coast of China! The king would’ve been far more generous if Cabot had brought home spices.

What happened to Cabot?

In 1498, Cabot was given permission by Henry VII to take ships on a new expedition to continue west from Newfoundland. The aim was to discover Japan. Cabot set out from Bristol with 300 men in May 1498. The five ships carried supplies for a year's travelling. There is no further record of Cabot and his crews, though there is now some evidence he may have returned and died in England. His son, Sebastian (1474–1577), followed in his footsteps, exploring various parts of the world for England and Spain.

View a replica of John Cabot's ship, which is open to the public in Bristol

Gifts inspired by seafaring in the Tudor and Stuart eras

Learn more about the emergence of a maritime nation

The UK National Charity for History

Password Sign In

Become a Member | Register for free

The Voyages of John and Sebastian Cabot

Classic Pamphlet

- Add to My HA Add to folder Default Folder [New Folder] Add

Discovering North America

Historians have debated the voyages of John and Sebastian Cabot who first discovered North America under the reign of Henry VII. The primary question was who [John or Sebastian] was responsible for the successful discovery . A 1516 account stated Sebastian Cabot sailed from Bristol to Cathay, in the service of Henry VII; environmental hardships had compelled Sebastian to travel to lower latitudes that led to the subsequent discovery of eastern North America. Still, early writers did not provide sufficient details of the expedition creating a number of discrepancies that undermine its validity.

In 1582, Richard Hakluyt printed letters that were granted on March 5, 1496 on behalf of King Henry VII to John Cabot that asked him to discover unknown lands in an effort to annex them for the Crown and monopolize English trade. This account, in contrast, indicated that John Cabot actually led the journey with his son Sebastian as his subordinate. Despite these opposing sources, it was not until the 19th century that historians began rejecting Sebastian as the primary discoverer of North America largely due to Richard Biddle who had published a Memoir of Sebastian Cabot in 1831. This memoir collated the sixteenth century writers with documents asserting Sebastian’s father, John Cabot, was merely a sleeping partner and an elderly merchant who did not go to sea—rendering Sebastian as the leader of the journey. Eventually, important documents emerged from unexamined archives of European states that almost irrefutably debunked Sebastian as the captain...

This resource is FREE for Student HA Members .

Non HA Members can get instant access for £3.49

Add to Basket Join the HA

3rd March, 2017

John Cabot and the first English expedition to America

During Tudor times Italian explorer John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto to give him his Italian name) led English ships on voyages of discovery and is credited with prompting transatlantic trade between England and the Americas. In an attempt to find a direct route to the markets of the orient, the Italian seafarer became the first early modern European to discover North America when he claimed Newfoundland for England, mistaking it for Asia.

Who was john cabot.

The son of a spice merchant, Giovanni Caboto (meaning either coastal seaman or ‘big head’, depending on who you ask) was probably born in Genoa in 1450, although he may have been from a Venetian family. At the age of 11, his family moved to Venice where Cabot became a respected member of the community and started learning sailing and navigation from the Italian seamen and merchants. He later married a girl named Mattea (the female version of Matthew) and eventually became the father of three sons: Ludovico, Sancto and Sebastiano. (Following in his father’s footsteps Sebastiano later became an explorer in his own right and went on to the Governor of The Muscovy Company).

In 1476 Cabot officially became a Venetian citizen and, now eligible to engage in maritime trade, began trading in the eastern Mediterranean. It is whilst working as merchant trader that Cabot may have developed the idea of sailing westward to reach the rich markets of Asia. Venetian sources also contain references to Cabot being involved in house building in the city around this time.

By the late 1480s, however, Cabot appears to have gotten into financial trouble and he left Venice as an insolvent debtor. Although little is known about Cabot’s exact activities over the next few years it is believed he travelled to Valencia, where he proposed plans for improvements to the harbour, and Seville, where he was contracted to build a stone bridge over the Guadalquivir river although the project was later abandoned.

Having continued his studies in map-making and navigation and, inspired by the discoveries of Bartolomeu Dias and Christopher Columbus, Cabot attempted and failed to persuade the royal courts of Europe to pay for a planned voyage west across the Atlantic. Still expecting to reach China, his idea was to depart to the west from a northerly latitude where the longitudes are much closer together on a shorter, alternative route.

After hearing of opportunities in England, Cabot and his family arrived there around 1495 to seek funding and political support for his planned voyage. Cabot immediately set about trying to persuade merchants in the major maritime centres of London and Bristol (the second-largest seaport in England and the only to have served as a point for previous English Atlantic expeditions) to help.

Cabot receives a royal commission

In Tudor times Cathay and Cipangu (China and Japan) were believed to be rich in silks, spices, gold and gems. If Cabot’s predictions about a new route were right and Asia was where Cabot thought it was, then the whole country stood to profit as it would have made England the greatest trading centre in the world for goods from the east. On 5 March 1496 Tudor King Henry VII issued letters patent to John Cabot and his sons, authorising them to explore unknown lands, with the following charge:

‘Be it known and made manifest that we have given and granted…to our beloved John Cabot, citizen of Venice…free authority, faculty and power to sail to all parts, regions and coasts of the eastern, western and northern sea, under our banners, flags and ensigns, with five ships or vessels of whatsoever burden and quality they may be, and with so many and with such mariners and men as they may wish to take with them in the said ships, at their own proper costs and charges, to find, discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of heathens and infidels, in whatsoever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians.’

After a first, aborted, attempt, Cabot sailed out of Bristol on a small 70-foot long ship named Matthew in May 1497 with a crew of 18 men, sailing past Ireland and across the Atlantic. On 24 June 1497 Cabot sighted land and called it ‘New-found-land’, believing it to be Asia and claiming it in the name of King Henry VII. Although the logs for Matthew are incomplete, it is believed that John Cabot went ashore with a small party. The exact location of the landfall has long been disputed, but most believe it to be one of the northern capes of modern-day Newfoundland off the coast of Canada. Only remaining on land long enough to claim the land and fetch some fresh water, the crew did not meet any natives during their brief visit but apparently they came across some tools, nets and the remnants of a fire and were able to catch huge numbers of cod just by lowering baskets into the seawater.

In the following weeks Cabot and his crew continued to explore and chart the Canadian coastline, before turning back and sailing for England in July.

Matthew and its crew arrived back in Bristol on 6 August 1497 to the welcome of church bells ringing out across the harbour. Cabot then rode to London to report to the King, where he was initially rewarded with the sum of £10 (equivalent to around two years’ pay for an ordinary labourer or craftsman) for discovering a new island off the coast of China – had Cabot brought back some spices then the king may have been more generous. At that point the king’s attention was increasingly being occupied by the Cornish Uprising led by Perkin Warbeck. Once his throne was secure, the king gave more thought to Cabot, who was already planning his next expedition. In September the King made an award of £2 to Cabot, followed by a pension of £20 a year in the December. The following February Cabot was given new letters patent for the voyage and to help him prepare for a second expedition.

In May 1498 Cabot set out with a fleet of four or five ships and 300 men aiming to discover Japan. Carrying ample provisions for a year’s worth of sailing, the fate of the expedition is uncertain as there is no further record of Cabot and his crews, except for one storm-damaged ship which is believed to have sought anchorage in Ireland. It is most widely thought that either the expedition perished at sea or that Cabot eventually reached North America but was unable to make the return voyage across the Atlantic.

You might also be interested in:

- What was Captain Cook looking for when he crossed the Antarctic Circle in 1773?

- Everest revealed

- The royal bed of Henry VII & Elizabeth of York

Books you might like

River Folk Tales of Britain and Ireland

Lisa Schneidau ,

Norfolk Folk Tales

Hugh Lupton ,

Scottish Folk Tales of Coast and Sea

English Folk Tales of Coast and Sea

Folk Tales from the Garden

Donald Smith , Annalisa Salis (Illustrator) ,

Folk Tales of Rock and Stone

Jenny Moon ,

Glamorgan Folk Tales for Children

Cath Little ,

Danish Folk Tales

Svend-Erik Engh , Tea Bendix (Illustrator) ,

Folk Tales for Bold Girls

Fiona Collins , Ed Fisher (Illustrator) ,

Crypto Confidential

Jake Donoghue ,

A Hell of a Bomb

Stephen Flower ,

Folk Tales of the Cosmos

Janet Dowling ,

Folk Tales of Song and Dance

Pete Castle ,

How I Didn’t Become A Beatle

Brian J Hudson ,

Shrewsbury in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s

David Trumper ,

The Secret Diary of Sarah Thomas

June Lewis-Jones ,

A History of Bury St Edmunds

Frank Meeres ,

The Man Who Didn’t Shoot Hitler

David Johnson ,

Inquisition

John Edwards ,

London – Life in the Post-War Years

Douglas Whitworth ,

Sign up to our newsletter

Sign up to our monthly newsletter for the latest updates on new titles, articles, special offers, events and giveaways.

© 2024 The History Press

Website by Bookswarm

- Hide Sidebar

- First Paragraph

- Bibliography

- Find Out More

- How to cite

- Back to top

DCB/DBC News

New biographies, minor corrections, biography of the day.

d. 24 April 1891 in Fredericton

Confederation

Responsible government, sir john a. macdonald, from the red river settlement to manitoba (1812–70), sir wilfrid laurier, sir george-étienne cartier, the fenians, women in the dcb/dbc.

Winning the Right to Vote

The Charlottetown and Quebec Conferences of 1864

Introductory essays of the dcb/dbc, the acadians, for educators.

Exploring the Explorers

The War of 1812

Canada’s wartime prime ministers, the first world war.

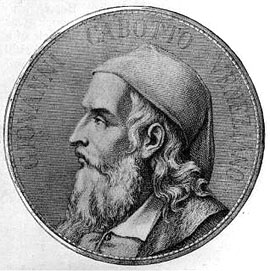

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

CABOT (Caboto), JOHN (Giovanni) , Italian explorer, leader of voyages of discovery from Bristol to North America in 1497 and 1498; d. 1498?

Neither the place nor the date of birth of Giovanni Caboto (also known as Zuan Chabotto, Juan Cabotto, and other variants), commonly called John Cabot, is known. His birth is now often given as c. 1450 although there is no firm evidence. The earliest historical document which refers to him records his naturalization as a Venetian citizen in 1476, under a procedure by which this privilege was granted to aliens who had resided continuously in Venice for 15 years or more. The resolution of the Venetian Senate, dated 28 March 1476, reads (in translation): “That a privilege of citizenship, both internal and external [ quae intus et extra ], be made out for Ioani Caboto , on account of fifteen years’ residence, as usual.” This decision, possibly confirming an earlier grant made between November 1471 and July 1473, implies that Cabot had been in Venice at least since March 1461, perhaps longer. When in London in 1497–98, Cabot was variously spoken of as a Venetian and as “another Genoese like Columbus,” and some 60 years later he was believed by English writers, probably on the authority of his son Sebastian , to be of Genoese origin. The surname Caboto, while absent from 15th-century records of Genoa, is found from the 12th century in those of Gaeta, where a Giovanni Caboto is named as late as 1431; and the family may have left Gaeta for Venice following Aragonese proscriptions after 1443, or an earthquake of 1456. Suggestions made by some modern writers that John Cabot was of Venetian, English, or Catalan origin have not been proven.

Documents in the Venetian archives, of dates between 27 Sept. 1482 and 13 Jan. 1485 (printed in R. Gallo, 1945) disclose that Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot), a merchant, was the son of Giulio Caboto deceased and had a brother Piero; that his wife Mattea was Venetian; and that by December 1484 he had two or more sons. These documents relate to property transactions in Chioggia and three other parishes; and as late as 1551 Sebastian Cabot was in communication with the Council of Ten about his patrimony in Venice. In the royal patent granted to John Cabot in England in 1496, his three sons are named, doubtless in order of seniority, as Lewis (i.e., Ludovico), Sebastian, and Sancio; and if they are the “sons” cited but not named in the Venetian record, the first two at least must have been born before 11 Dec. 1484.

From 1461, or earlier, until 13 Jan. 1485 John Cabot’s residence in Venice is attested. On his employment during the next 11 years, in which he must have formulated his project for a westward voyage to the Indies, the evidence is indirect and equivocal. Italians who spoke with him in London in 1497 learned that he had been engaged in the spice trade of the Levant, claiming even to have reached Mecca; they noted that he was “a most expert mariner” and a maker of maps and globes; and their reports of his conversation reveal that he was familiar with Marco Polo’s account of the Far East and with the new discoveries made for the crowns of Portugal and Spain. Documents in the Valencia archives (Epist. vol. 496) show that a Venetian named John Cabot Montecalunya (“ johan caboto montecalunya venesia ”) was resident in Valencia from the middle of 1490 until, probably, February 1493, and that he prepared plans for harbour improvements which he expounded to King Ferdinand in two interviews. Although the epithet “montecalunya” has defied interpretation, the identification of this man with John Cabot the explorer is very probable, while not positively established. Acceptance of it may carry the implication that he was present in Valencia when, in April 1493, Christopher Columbus passed through the city on his way to Barcelona, there to report to the Spanish sovereigns the triumphant issue of his western voyage. According to Pedro de Ayala, the associate Spanish envoy in London, writing on 25 July 1498, Cabot had, before coming to England, sought support for his own project in Lisbon and Seville (Archivo General en Simancas, Estado, Tratados con Inglaterra, leg.2, f.196; an English summary is in PRO, CSP, Spanish, 1485–1509 , no. 210). We do not know whether these applications were made before or after Columbus’ voyage; their want of success may be explained by the Portuguese rejection and the Spanish approval of Columbus’ proposals and claims. But if John Cabot in fact witnessed the return of Columbus in the spring of 1493, his reading of Marco Polo may well have led him to discredit Columbus’ belief that he had reached Cathay, and to suppose that the western sea route to Asia remained to be discovered.

At some date before the end of 1495 John Cabot arrived in England with a plan for reaching Cathay by a westward voyage in higher latitudes, and so by a shorter route, than those of the trade-wind zone in which Columbus had made his crossing. To Cabot’s objectives and the means by which he proposed to reach them, and to the experience and reasoning by which he formulated his project, we have only indirect testimony, since no writing from his hand or of his composition survives on these matters. Converging evidence of various kinds points to hypothetical conclusions which are logically related to one another and to the various projects for Atlantic exploration in the last two decades of the 15th century. These conclusions, although subject to the reservation that they may be modified by new evidence, enable us to reconstruct Cabot’s motives and to account for his movements.

The discovery of land by any of the Portuguese expeditions which, during the 15th century, sought islands in the western Atlantic is unauthenticated. From 1480 or earlier, by a more northerly route, English venturers from Bristol [for example, Croft and Jay ] set forth regular voyages in search of the “Island of Brasil,” shown on contemporary charts to the west of Ireland; and at some date before 1494 their search was crowned by the discovery of a mainland, with which Cabot’s crew were to identify the North American landfall made on his first voyage in 1497. The Bristol men were interested in fishing grounds, not in a trade route to East Asia; but, if Cabot had, at some time before the end of 1495, received news in Spain or Portugal about the Bristol discovery, perhaps by a “leakage” through trade channels, his move to England in expectation of official support and a base for his voyage can be explained. Bristol, the westernmost port of England, could provide seamen who had mastered the winds and navigation for a westward passage in these latitudes. The land which they had found might turn out to be at worst an island which would serve as a station on the voyage to Cathay, at best the northeast point of Asia which could be coasted in a southwesterly direction to the lands of the Great Khan in tropical latitudes, far to the west of Columbus’ discovery. Thus the pattern of land and water which probably ruled Cabot’s thought when he went to England in or before 1495, and certainly did so after his return from his voyage of 1497, having “discovered . . . the country of the Grand Khan” and coasted it for 300 leagues from west to east, must have corresponded to that illustrated in the later world maps of Contarini-Rosselli (1506) and Ruysch (1508).

On 21 Jan. 1496 Gonsalez de Puebla, the Spanish ambassador in London, wrote a report (not now extant) to his sovereigns, who replied on 28 March, referring to what he had said “of the arrival there of one like Columbus for the purpose of inducing the King of England to enter upon another undertaking like that of the Indies” (A.G.S., Estado, Tratados con Inglaterra, leg.2, f.16). On 5 March 1496, Cabot received letters patent from King Henry VII for a voyage of discovery from Bristol; and the lengthy process by which agreement on the terms of the patent was reached must have been set on foot some time earlier, although its initiation cannot much have antedated Puebla’s letter. The argument that Cabot had conducted or inspired earlier voyages from Bristol, perhaps going back to 1491, rests on three documents. In his letter of July 1498 Pedro de Ayala recorded that “for the last seven years” the men of Bristol had sent ships to seek the island of Brazil and the Seven Cities “according to the fancy [or reckoning] of this Genoese” (“ con la fantasia desto Genoves ”); if John Cabot were in Valencia in 1490–93, Ayala’s phrase must be taken to indicate merely Cabot’s later interpretation of the objectives of the Bristol voyages, and not his direct association in or with them. Sebastian Cabot’s world map of 1544 (now in BN, Paris) is accompanied by printed legends, the eighth of which ascribes the landfall made by John and Sebastian Cabot in the Cape Breton area to the year 1494; although the map and its legends doubtless incorporate information from Sebastian, his father, while in London in 1497–98, referred to his landfall of 1497 as a new discovery and made no allusion to any earlier successful voyage by him. The date in the legend of the 1544 map is in all probability a misprint for “1497,” the last four digits, written in Roman numerals, having been misread by the printer (IIII for VII). Finally, John Dee in 1580 attached the date “Circa An. 1494” to his note on the discovery of “the New Found Lands” by Robert Thorne and Hugh Eliot , merchants of Bristol (BM, Cotton MS Augustus I. i.1). As a record of a successful Bristol voyage before Cabot’s, this may be authentic, for Dee took his information from the papers of Thorne’s son; but the extant copies of these papers do not ascribe to the discovery any year-date, which must be taken to be a gloss by Dee, perhaps derived from Sebastian Cabot’s map, and without earlier authority. The balance of evidence suggests that John Cabot made no westward voyage before the grant of his patent in March 1496. Moreover, this patent makes no mention of any earlier discovery by Cabot, although his later patent, granted in 1498, cites the successful voyage of 1497 which had preceded it.

The petition for letters patent was presented to King Henry VII on 5 March 1496 by “John Cabotto, Citezen of Venice” and his three sons (PRO, P.S.O. 2, 146). The letters patent, under the same date, authorized Cabot, his sons, their heirs, and their deputies to sail with five ships “to all parts, countries and seas of the East, of the West, and of the North,” thus excluding them from the region of the Spanish discoveries in the Caribbean. They were however empowered to “discover and find whatsoever isles, countries, regions or provinces of heathens and infidels, in whatsoever part of the world they be, which before this time were unknown to all Christians”; if Cabot found new land in the zone to which he was restricted by the preceding clause, he was therefore permitted to follow its coast into the latitudes of discoveries by other nations. The patentees were to hold newly found lands under the king and received other privileges; no other subjects of the king might frequent lands discovered by the patentees without their licence.

In 1496, under the authority of his letters patent, John Cabot made an abortive voyage from Bristol with one ship, turning back because of disagreement with his crew, shortage of food, and bad weather. The evidence for this is an undated letter written late in 1497 or early in 1498 by the English merchant John Day and addressed to a correspondent in Spain whom he styles “Almirante Mayor” and whom there are good grounds for identifying with Christopher Columbus. Day’s letter is also the only document which establishes the earlier discovery of “Brasil” by the Bristol men; and it gives a detailed narrative of Cabot’s voyage of 1497. The other evidence for the course of this voyage comprises three contemporary letters written by foreigners in London (23 Aug. 1497, Lorenzo Pasqualigo to his brothers in Venice; 24 Aug. 1497, an anonymous Milanese correspondent to the Duke of Milan; 18 Dec. 1497, Raimondo de Soncino to the Duke of Milan), a passage in a Bristol chronicle written by Maurice Toby (in or after 1565), and the world maps of Juan de la Cosa (1500) and Sebastian Cabot (1544). From their data, in spite of a few discrepancies, it is possible to construct a coherent narrative of the voyage.

John Cabot sailed from Bristol on 2 May (Toby’s date; “towards the end of May,” Day; about the middle of May, Pasqualigo) in a small ship named the Matthew (Toby), with a ship’s company of 20 (Day; 18, Soncino), including a crew of Bristol seamen, two or more Bristol merchants (Toby, who ascribes the discovery to them and does not name Cabot), a Burgundian and a Genoese barber, both companions of Cabot. Sailing past southern Ireland he made a passage of 700 leagues (Pasqualigo; 400 leagues, anonymous Milanese), in 35 days with ene winds before sighting land (Day); two or three days earlier he had run into a storm and noted a compass declination of two points (22½°) west. The landfall was made on 24 June, St. John the Baptist’s Day (Toby and the 1544 map); a reckoning of 35 days back would give 20 May as the date of departure. In the wooded country near his landfall Cabot went ashore, seeing no people but signs of habitation, and made a ceremonial act of possession. This was his only landing; after a coasting voyage of 300 leagues (Pasqualigo) from west to east, lasting one month, he made his departure from the “cape of the mainland nearest to Ireland” and 1,800 miles west of Dursey Head (Day). A return voyage of 15 days brought him with a fair wind to Brittany (Day) and so to Bristol on 6 August (Toby). He reported to Henry VII in London before 10 or 11 August, when the king’s daybooks record a payment of £10 “to hym that founde the new Isle.” By 23 August, when Pasqualigo wrote, Cabot was back “with his Venetian wife and his sons at Bristol,” where he rented a house in St. Nicholas Street on St. James’s Back.

The claims made by Cabot for his discovery and the impression which they made at the English court are attested by the contemporary reports. The mainland found was “the country of the Grand Khan” (Pasqualigo), “far beyond the land of the Tanais” (Soncino); it is also identified with the Island of the Seven Cities (anonymous Milanese; Day); it produced brazil-wood and silk, and the sea swarmed with cod-fish (Soncino; Day). Cabot “is called the Great Admiral, and vast honour is paid to him, and he goes dressed in silk, and these English run after him like mad” (Pasqualigo). He had made a world map and a globe showing where he had been (Soncino); by the beginning of 1498 John Day had a transcript of the map in his possession and had sent to the “Almirante Mayor,” in Spain, “a copy of the land which has been found” (presumably a chart of the coasts discovered), naming “the capes of the mainland and the islands”; and another version of Cabot’s world map was by July 1498 in the hands of Ayala, who supposed the Spanish government to have received a copy.

The identification of the point at which the landfall was made on 24 June 1497 and of the coasts traversed by Cabot in the ensuing 30 days has been much debated. La Cosa’s world map undoubtedly incorporates, in its representation of North America, information from Cabot’s first voyage in 1497 and possibly also (with much less certainty) from his second voyage, in 1498. The channels by which this material could have come into La Cosa’s hands are illustrated in the letters of Day and Ayala. By the middle of 1498 a copy or copies of Cabot’s world map had reached Spain, together with “the copy of the land” sent by Day, perhaps a sketch-chart with a list of places and distances. All these originals are now lost, and some caution is necessary in trying to reconstruct Cabot’s geography from the map of La Cosa. The map constitutes two distinct sections; the New World is drawn, on a larger scale than the Old World, from recent disjunct discoveries, completed by conjectural or theoretical interpolation. Since the scale is not uniform, it is impossible to correlate latitudes on the two sides of the Atlantic or the distances on the map with those reported to have been logged by Cabot. La Cosa’s outlines, like the originals from which they were compiled, are drawn by compass bearings; and, to bring this part of the map into true orientation, it must be rotated anti-clockwise through some 22 degrees. The surviving example of the map appears to be a copy, with resultant generalization of outlines and considerable corruption of the place-names, some of which in the course of time have become wholly or partly illegible. The map is in one hand throughout; and, in spite of attempts to assign it to a later date, its content is consistent with a compilation date of 1500 or a little earlier.

It is generally agreed that, in this map, the section of North American coast trending E-W and marked by five English flags reflects John Cabot’s coasting voyage in June-July 1497, although it may also include information from that of 1498. Of the 22 named features, the easternmost cape is styled Cauo de ynglaterra , one further west C ° de lisarte (Lizard?), and a gulf to the west of the named features mar descubierto por inglese . Widely divergent identifications of the coast so delineated have been made (most of them before John Day’s detailed report of the voyage came to light in 1956). It has been variously held to represent the north shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence; the south coast of Newfoundland; the east coasts of Newfoundland and Labrador; Nova Scotia and Newfoundland; or even the west coast of Greenland.

The basic statement made by La Cosa’s map is that Cabot traversed a coastline facing generally SSE across open sea; this seems to exclude the closed waters of Belle Isle strait or the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Day confirms that the coasting was from west to east, and his “cape nearest to Ireland” may be identified with La Cosa’s Cauo de ynglaterra . The length of the coastal traverse – 900 miles (Pasqualigo) in a month (Day) – is therefore to be measured back from the point of departure, at Cauo de ynglaterra , to Cabot’s first sight of the land called by Day (also by the anonymous Milanese) the Island of the Seven Cities and located by him about latitude 45½ºN. Pasqualigo and the anonymous Milanese refer to two islands seen by Cabot on the way back to England; and Day identifies the cape of departure as the “Brasil” discovered by the Bristol men, referring to the wealth of fish, and places it about latitude 51½ºN, i.e., that of Cape Bauld. This latitude is irreconcilable with the duration of the coastal voyage from a landfall in 45½ºN and with La Cosa’s delineation.

These details indicate either Cape Race or Cape Breton as Cabot’s point of departure for home. Cape Race is more easily reconcilable with the Bristol discovery and with La Cosa’s delineation (in spite of the y: verde which he draws, perhaps after a cartographic tradition, in the ocean east of Cauo de ynglaterra ). Cape Breton would admit the two islands sighted on the homeward voyage; but this cape is marked as the point of landfall ( Prima tierra vista ) on the world map of 1544, the authority of which may be suspect. Even if the 900 miles of coasting be substantially reduced, in view of Cabot’s need to keep in sight of land, a long shore voyage which ended at Cape Race must have begun on the Coast of Maine, and one which ended at Cape Breton still farther to the southwest. If the testimony of La Cosa’s map be taken in conjunction with the documentary evidence, there are fewest difficulties in supposing the coasting voyage to have extended from a landfall in Maine or southern Nova Scotia to Cape Race. This hypothesis must be qualified by uncertainty about the reliability and precision of the several sources. It is nevertheless consistent with the geographical ideas which nourished both the plan for John Cabot’s first voyage of reconnaissance and his proposals for further exploration of the route to Cathay, founded on his interpretation of his discovery as “a part of Asia.”

In December 1497 Cabot expounded these proposals to the king in London. Soncino records the enthusiasm of the Bristol seamen about the rich fishing grounds revealed; but Cabot, he adds, “has his mind set upon even greater things, because he proposes to keep along the coast from the place at which he touched, more and more towards the east [i.e., westward towards East Asia], until he reaches an island which he calls Cipango, situated in the equinoctial region, where he believes all the spices of the world to have their origin, as well as the jewels.” This terminology plainly echoes Marco Polo’s description of Cipangu and the eastern archipelago; and the association of ideas is strengthened by the wording of Day’s letter, written about the same time, with which he sent to his correspondent “the other book of Marco Polo and the copy of the land which has been found.” Similarly Ayala, after inspecting the records of the voyage of 1497, reported to his sovereigns that “what they have discovered or are in search of [i.e., on the voyage of 1498] is possessed by Your Highnesses because it is at the cape which fell to Your Highnesses by the convention with Portugal” – an allusion doubtless to Cuba, taken by Columbus to be a cape or peninsula of Cathay.

Cabot’s purpose therefore was to follow the coast in a southwesterly direction from his first landfall until he came to the realm of the Great Khan. The preparations for his new expedition also suggest the intention to establish a “colony” or trading-post, either on the coast of Cathay or at an intermediate station on the route; this was to be manned by “malefactors” or prisoners supplied by the king, and some Italian friars were also to go with the expedition. On 3 Feb. 1498 royal letters patent authorized “John Kaboto, Venician,” to impress six English ships of 200 tons or smaller burden, to conduct them “to the londe and Iles of late founde by the seid John,” and to take with him out of the realm any of the king’s subjects who would go on the voyage. The composition of the fleet is disclosed by a London chronicle of which variant versions, derived from a lost original composed in 1509 or later, survive from the 16th century. There were five ships; one was equipped by the king and perhaps hired from the London merchants Lancelot Thirkill and Thomas Bradley , who seem to have sailed in her, while the other four ships were from Bristol and were fitted out by merchants of Bristol and London, whose names are unknown. Of Cabot’s other companions only three names are recorded: John Cair “going to the newe Ile” (a payment in the Household books, 8–11 April 1498), Messer Giovanni Antonio de Carbonariis , a Milanese cleric (letter of Agostino de Spinula to the Duke of Milan, 20 June), and “another Friar Buil” (Ayala’s letter, 25 July). The ships were provisioned for one year and carried cargoes of merchandise. Cabot’s favour with the king is attested by the grant of an annual pension of £20, to be paid from the Bristol customs and subsidies (13 Dec. 1497), and by a “reward” of 66 s . 8 d . (8–12 Jan. 1498); the warrant for the first payment of the pension was issued on 22 Feb. 1498.

No narrative record of Cabot’s second voyage is extant, and the train of events can only be inferred from scattered allusions. The ships sailed from Bristol at the beginning of May, according to the London chronicler; by 25 July Ayala had heard that one ship, damaged in a storm, had put into an Irish port. That this ship may have been Cabot’s and have subsequently resumed the voyage is suggested by a passage of Polydore Vergil (written 1512–13): “John [Cabot] set out in this same year and sailed first to Ireland. Then he set sail towards the west. In the event he is believed to have found the new lands nowhere but on the very bottom of the ocean, to which he is thought to have descended together with his boat . . . since after that voyage he was never seen again anywhere” ( The Anglica Historia of Polydore Vergil, A . D . 1485–1537 , trans. D. Hay (Royal Hist. Soc., Camden ser., LXXIV, 1950), 116–17). Although Cabot’s pension was paid, not necessarily to him in person, in each of the two years 1497–98 and 1498–99 (Michaelmas to Michaelmas), it may be taken that he never returned to England, where his fate remained unknown.

By mid-September 1498 no more news of the expedition had reached London; but it is very probable that, if Cabot was lost, one or more of its other ships survived the voyage and that reports of it came back to England and Spain. The evidence for this, positive and negative, is slight but cumulatively significant. In the summer of 1501 the Portuguese crew of one of Gaspar Corte-Real ’s ships obtained from natives, probably on the Newfoundland coast, “a piece of broken gilt sword” of Italian workmanship and two silver Venetian earrings; of the previous expeditions recorded to have visited these coasts, namely those of the Bristol men, before 1494, of Cabot in 1497 (when he encountered no inhabitants), and of Cabot in 1498, the last-named seems the most probable source for the objects. Some news of the course of Cabot’s ships evidently reached the Spanish government before 8 June 1501. On that date the sovereigns issued letters patent to Alonso de Ojeda for a voyage of exploration along the mainland coasts of the Caribbean, from south to north, commencing at Cabo de la Vela, in Colombia, which Ojeda, in company with La Cosa and Vespucci, had reached on a westerly traverse from Trinidad in 1499. He was now instructed to “follow that coast which you have discovered, which runs east and west, as it appears, because it goes towards the region where it has been learned that the English were making discoveries; and that you go setting up marks with the arms of their Majesties . . . so that you may stop the exploration of the English in that direction. “ In July 1498 Ayala, “having seen the course they are steering and the length of the voyage,” had warned his government of Cabot’s intention to follow the coast in a southwesterly direction into the tropics; and Ojeda’s patent suggests that one or more of the English ships advanced either into the Caribbean or far enough to the south, along the North American coast, to alarm the Spaniards. How far this penetration extended cannot be positively affirmed. If any cartographic evidence of it exists, it is to be sought only in the coastline drawn by La Cosa from the mar descubierto por inglese , at the western limit of his “English coast,” in a general WSW direction down to the latitude of Cuba. The conventional appearance of the drawing may be due to generalization by the copyist, and the absence of place names does not exclude the possibility that the design is a record of experience. Many students have in fact associated this delineation with the voyage of 1498, identifying certain details of it with real geographical features (Cape Cod, the Hudson River, the Delaware, Florida). The most that can be said is that, if La Cosa here records the results of an expedition of discovery, that expedition is more likely to be Cabot’s of 1498 than any other.

During the 16th century John Cabot’s reputation was eclipsed by that of his son Sebastian, to whom the discovery of North America made by his father came to be generally attributed. This misapprehension, which Sebastian did nothing to remove before his death in 1557, arose in part from confusion between John Cabot’s expedition of 1498 and the later westward voyage made by Sebastian under the English flag, in part from ambiguity in some of the early records (including those derived from Sebastian) relating to the Cabot voyages, and in part from ignorance of other records. Thus the passage in the London chronicle describing the expedition of 1498 referred to its leader simply as “a Venetian,” whom John Stow, in The chronicles of England from Brute unto this present yeare of Christ, 1580 (London, 1580) and Richard Hakluyt, in Divers voyages touching the discoverie of America (London, 1582), identified as Sebastian Cabot, although Hakluyt printed, also in his Divers voyages , the letters patent issued to John Cabot and his sons in March 1496. Until the second quarter of the 19th century historians could still credit Sebastian with the conduct of his father’s two expeditions, identifying that of 1498 with the voyage into high arctic latitudes made by Sebastian and described by him to Peter Martyr between 1512 and 1515 and to Ramusio in 1551. The Spanish, Venetian, Milanese, and English documents which came to light during the 19th century enabled Henry Harrisse (1882 and 1896) to restore to John Cabot the credit for the ventures of 1497 and 1498, and G. P. Winship (1900) to review the chronology and to isolate the aims and course of Sebastian’s independent voyage, which he assigned to the years 1508–9.

Although some 20th-century historians associated Sebastian’s statements about his own voyage with that of 1498, Winship’s views, as adopted and developed by J. A. Williamson and R. Almagià, have commanded fairly general consent. They establish indeed a coherent and progressive relationship between the geographical concepts and objectives of the three voyages. As the scanty records place beyond doubt, John Cabot sailed in 1498 with the intention of running southwest from his discovery of 1497 along the coast which he supposed to be that of East Asia. If, as seems probable, either he or his companions executed this design, they found neither Cathay nor any westward sea passage. That this “intellectual discovery of America” may have resulted directly from the 1498 voyage is suggested by the fact that (as Williamson has pointed out) the records of subsequent English voyages to the west contain “no more talk of Asia as lying on the other side of the ocean.” By 1508 Sebastian Cabot was seeking a northern passage round the continent which lay across the seaway to Cathay.

No contemporary portrait of John Cabot is known to exist; an ideal representation of him and his three sons was painted by Giustino Menescardi in 1762 on the wall of the Sala dello Scudo in the Palazzo Ducale, Venice. The memorials erected in England and Canada to celebrate the quatercentenary of his discovery, in 1897, include the Cabot Memorial Tower at Bristol.

R. A. Skelton

The primary or manuscript sources are extremely numerous, but they are gathered together in the various works cited below, in chronological order. The best general collections of documents on both the Cabots are those of Biggar (1911) and Williamson and on Sebastian Cabot, that of Toribio Medina. Significant documents, or groups of documents, are those published by Ballesteros-Gaibrois, Gallo, Vigneras, and Pulido Rubio.