- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Official Writing

- Report Writing

How to Write a Visit Report

Last Updated: March 30, 2024 References

This article was co-authored by Madison Boehm . Madison Boehm is a Business Advisor and the Co-Founder of Jaxson Maximus, a men’s salon and custom clothiers based in southern Florida. She specializes in business development, operations, and finance. Additionally, she has experience in the salon, clothing, and retail sectors. Madison holds a BBA in Entrepreneurship and Marketing from The University of Houston. This article has been viewed 653,380 times.

Whether you’re a student or a professional, a visit report helps you document the procedures and processes at an industrial or corporate location. These reports are fairly straightforward. Describe the site first and explain what you did while you were there. If required, reflect on what you learned during your visit. No additional research or information is needed.

Writing a Visit Report

Explain the site's purpose, operations, and what happened during the visit. Identify the site's strengths and weaknesses, along with your recommendations for improvement. Include relevant photos or diagrams to supplement your report.

Describing the Site

- Reports are usually only 2-3 pages long, but in some cases, these reports may be much longer.

- In some cases, you may be asked to give recommendations or opinions about the site. In other cases, you will be asked only to describe the site.

- Ask your boss or instructor for models of other visit reports. If you can't get a model, look up samples online.

- If you visited a factory, explain what it is producing and what equipment it uses.

- If you visited a construction site, describe what is being constructed and how far along the construction is. You should also describe the terrain of the site and the layout.

- If you’re visiting a business, describe what the business does. State which department or part of the business you visited.

- If you’re visiting a school, identify which grades they teach. Note how many students attend the school. Name the teachers whose classes you observed.

- Who did you talk to? What did they tell you?

- What did you see at the site?

- What events took place? Did you attend a seminar, Q&A session, or interview?

- Did you see any demonstrations of equipment or techniques?

- For example, at a car factory, describe whether the cars are made by robots or humans. Describe each step of the assembly line.

- If you're visiting a business, talk about different departments within the business. Describe their corporate structure and identify what programs they use to conduct their business.

Reflecting on Your Visit

- Is there something you didn’t realize before that you learned while at the site?

- Who at the site provided helpful information?

- What was your favorite part of the visit and why?

- For example, you might state that the factory uses the latest technology but point out that employees need more training to work with the new equipment.

- If there was anything important left out of the visit, state what it was. For example, maybe you were hoping to see the main factory floor or to talk to the manager.

- Tailor your recommendations to the organization or institution that owns the site. What is practical and reasonable for them to do to improve their site?

- Be specific. Don’t just say they need to improve infrastructure. State what type of equipment they need or give advice on how to improve employee morale.

Formatting Your Report

- If you are following a certain style guideline, like APA or Chicago style, make sure to format the title page according to the rules of the handbook.

- Don’t just say “the visit was interesting” or “I was bored.” Be specific when describing what you learned or saw.

Sample Visit Report

Community Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://services.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/471286/Site_Reports_for_Engineers_Update_051112.pdf

- ↑ https://www.examples.com/business/visit-report.html

- ↑ https://www.thepensters.com/blog/industrial-visit-report-writing/

- ↑ https://eclass.aueb.gr/modules/document/file.php/ME342/Report%20Drafting.pdf

About This Article

To write a visit report, start by including a general introduction that tells your audience where and when you visited, who your contact was, and how you got there. Once you have the introduction written out, take 1 to 2 paragraphs to describe the purpose of the site you visited, including details like the size and layout. If you visited a business, talk about what the business does and describe any specific departments you went to. Then, summarize what happened during your visit in chronological order. Make sure to include people you met and what they told you. Toward the end of your report, reflect on your visit by identifying any strengths and weaknesses in how the site operates and provide any recommendations for improvement. For more help, including how to format your report, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Betty Tarutia

Jul 9, 2020

Did this article help you?

Jayani Rathnayake

Aug 6, 2019

Jun 13, 2019

Atremedaki Phawa

Aug 19, 2019

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

REPORT WRITING ON STUDY VISITS FOR LIBRARY STUDENTS: AN EXAMPLE.

Related Papers

John Spurgeon

Ayodeji T . Oyekunle

This research work is being conducted to expose some of the inhibiting factors that are hindering the impact of ICT in Nigerian academic libraries considering OAU library as a case study. This study begins with an investigation on ICT literacy and its application for library services by students. The study examines the utility and ascertain the reasons for the use and non-use of internet resources at the library, OAU. The study also assess the purpose and relevance of the use of ICT in the Hezekiah Oluwasanmi Library, OAU. This study gathered information through questionnaires. The population of the study was made up of purposively selected 100 students. Data was analysed using univariate and bivariate analysis. The results for the analysis showed that respondents agreed that most of the ICT facilities are available and functional. It also revealed that ICT literacy is required to effectively utilize the ICT applications in the library. Based on the findings, it was recommended that individuals should be sensitized on the availability of ICT facilities and be encouraged to use them for their personal and library services. Students should constantly use computer system and the internet in order to attain ICT literacy proficiency, they should also be sponsored for ICT literacy training, library management software should be acquired and installed for efficient and effective library services; funds, ICT infrastructure and training opportunities should be provided by the government, NGOs and other stakeholders.

Sani M Ridwan

Internet has greater impact on education; particularly, higher education by creating and promoting virtual learning environments, Learners thus formulate their virtual communities and interact freely with each other they can exchange their learning experiences, research findings and academic opportunities. The Internet revolution is not just limited to finding information but also to fostering relationships that bring people together. Internet has many functions in higher education include storehouse of information, communication without boundaries, online interactive learning, electronic/online research, innovation in the new world, improve interest in learning, global education, and Information catalogues. This section has conducted survey on utilization of internet for academic purposes on Nuhu Bamalli Politechnic Library, Zaria Kaduna-Nigeria. The electronic resources offer ease of use, wider access, more rapid updating, cost saving over local maintenance and storage, the librarians are finding it difficult to define issues related to policy of collection development and archiving of electronic resources. The electronic resources require continuing management to a far greater degree than print resources do. However, the primary aim of the electronic information resources and services will be to support the institution’s learning, teaching, and research, which might change significantly with number of users. This section has conducted Assessment and utilization of Electronic Information Resources and Services in Kaduna State University Library, Kaduna- Nigeria. The tertiary education sector in Nigeria is made up of three categories of institutions these are Universities, Polytechnics/Colleges of Technology and Colleges of Education, the Federal Government of Nigeria evidently recognizes the important roles library play in education and research through provision of information services as recommended by the National Universities Commission (NUC), hence it recommends that a minimum of 10% of each institution’s recurrent budget be spent on the development of their libraries. This section has conducted survey on accessibility and policy of funding in acquisition of information resources in federal college of education, zaria, so that the research has revealed the actual sources of fund, Acquisition policy and adequate funding made available in provision to acquisition of information resources in federal college of education, zaria The application and diffusion of information and communication technology cannot be viewed in isolation from development in telecommunication technology. Innovation in computer and telecommunication technology have resulted in major changes in basic library operations as well as managing information in different offices and organization, such as circulatory reference services, cataloguing and classification, collection development (ordering and acquisition). However, the innovations have prompted many organizations to employ the use of ICT devices to further manage information and records of the organization. On this note, many organizations, now adopt the use of computer systems, database management systems, development of network systems to create, store, preserve, secure and use information for effective decision making in the organization. This section highlights the prospects and problems of I.C.T in Kashim Ibrahim Library ABU, zaria.

ramarothole celina

Personnel Issues in the 21st Century Librarianship

Chimezie Uzuegbu

Library Hi Tech News

Rexwhite Enakrire

Ifla Journal

Mahdi Mohammadi

Dalitso Mvula

This study was conducted with the aim to access the utilization of e-resources by natural science fourth year students at the university of Zambia great east road campus. However the objectives of the research included to investigate students awareness of e-resources provided by UNZA Library, to investigate the extent to which natural science students utilize the e-resources, to establish the frequency of using e-resources, to establish the purpose of using e-resources and to investigate the challenges natural science students face when accessing e-resource provided by UNZA Library. The study population consisted of 100 natural science fourth year students self-administered questionnaires were used, the 100 students were selected using systematic sampling and the findings of the study were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS). According to the findings, the majority of the respondents accounting for about 44.4% pointed out that they are not aware of e-journals and furthermore, 49.5% respondents was not aware of the e-books provided by UNZA Library. However, reason given regarding the non awareness of these e-resources were limited access to the internet, less routers within the school premises, lack of knowledge and poor orientation. However, it was recommended that the number of routers be increased within campus so as to allow internet access at convenient places such as hostels, library and lecture rooms, it was also recommended that more information should be made available through sensitization programmes on e-resources and also a good orientation about e-resources to the newly admitted students be conducted to create awareness.

Shuaib Olarongbe

Bolanle Alaba Akanbi Ademolake

RELATED PAPERS

Ogagaoghene U. IDHALAMA

ABIODUN ADEGBILE

NIGERIAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION

xa.yimg.com

Fehintola N Onifade

Fatima G Bawa

Syazwani Munajat

Oyintola Isiaka I Amusa

Alexander Decker

THE SCHOOL LIBRARY AS A LEARNING ENVIRONMENT

Samuel A B I O D U N Olaleye

Nigeria Journal of Educationand Technology FUTY, Vol. 12, Issue 1&2, September. PP. 38-44

ANDREW TEMBOGE

Proceedings of IPID Postgraduate Strand at ICTD …

kasina VRao

Library and Information Science: A Book of Readingss

fasanu idowu

Olatokunbo Christopher OKIKI

Associate Professor MILBURGA M A ATCERO

Tolough Martins

Chukwuemeka Chukwueke

Proceedings of IPID …

Jimena Ponce de León

Liceli Quilca

Oyintola Isiaka I Amusa , Abiodun Iyoro

Marion Walton

Fatimah Agbaje

sciepub.com SciEP

Ariel Fontecoba

Gbadamosi Bellau

Kolawole Aramide

USE OF ICT IN ADMINISTRATION OF NIGERIAN UNIVERSITIES: A STUDY OF BAYERO UNIVERSITY KANO

Adamu Garba

Francisco Javier Proenza

Laura Leon Kanashiro , Juan Bossio

Teresa Neely

MADU U Z O M A AUGUSTINE

The Electronic Library

Muta Tiamiyu

Bakare bunmi

Oyeronke Adebayo , Michael Fagbohun

Kudirat Abiola

Akorede Diyaolu

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Academic Skills

- Reading, writing and referencing

Site visit reports

Key stages of conducting a site visit and reporting your observations and findings.

When you visit a site, company, institution, plant or other location outside the university to observe how your field of study operates in practice, you are often required to write about what you saw. Whether you have to write a standalone report or record your observations for a larger piece of assessment, following the stages below will help you get the most out of your site visit.

Before your visit

Your visit might be the only chance you have to collect information about the site that is not available from other sources.

To prepare for your site visit:

- Review your subject material in the LMS and your notes, and brainstorm what you already know about the site.

- Do some preliminary research about the site in relevant library databases and online, so you know what information is already available in published sources.

- Make a list of the information you think you need to collect at the site.

- Prepare questions to ask staff at the site, if they will be available.

Collate the materials you will need to refer to at the site, e.g. your task brief, list of information to collect and questions, in a format you can access easily while on the move. Ensure that you have a reliable way to take notes, and that your phone has plenty of charge for taking photos.

A notebook or document with prepared headings makes it easy to record the information you need. You should also make sure you:

- Complete any forms or health and safety requirements for your subject.

- Know how to get to the site, and who to contact if you are delayed.

- Wear clothing that is appropriate to the site conditions and the weather.

During your visit

To maximise the information you gather:

- Take notes of any impressions or observations you have, of all aspects of the visit, under subheadings. Extra notes can help you recall important details you may not have realised were relevant at the time.

- Record voice messages or memos of insights as they happen to avoid having to rely on your memory.

- Take photos from different perspectives. If you need to include images in your assessment, you will be glad you have a range to choose from. You may not have a chance to return to the site to take more photos if you missed something important on the day.

- Ask questions when you have the opportunity. If you meet any staff at the site, they are likely to expect you to ask questions and are usually happy to answer.

Gathering as much information as possible during the site visit will give you a wider range of material to draw from when you are preparing your report or assessment, and you will be able to produce a more accurate and polished piece of work.

Sections of a site visit report

Site visit reports may vary from subject to subject, so you should always check the information you’ve been given in your assessment brief or in other subject material. If your site visit report contains the following features, these explanations may help you gain a sense of the purpose of various sections:

Include the title of the visit or project, name of the site, the date of the site visit, and your name and student number. You may also need to include your tutor’s name, your tutorial group, or your team members for group assignments.

An executive summary is a condensed version of the whole report. It typically contains a few sentences on the background and location of the site, the purpose of the report, a statement about what was observed, and a few sentences that offer a conclusion or recommendations.

The introduction of the report should set the context for the level of observation conducted on the site visit. Include the importance of what is being observed and what you can learn from those observations. This might be, for example, to address a problem or provide a solution in another location.

This section is highly dependent on your context. It may involve explaining procedures and processes, such as chemical processes, construction, or commercial operations of a plant, or how certain features of the site are arranged.

In the final section, you should sum up the key findings from the site visit and comment on the implications of these findings, and you may also give recommendations if that is appropriate to the task. If you are required to reflect on your experience, try and make connections between what you have observed at the site and what you have learned in your subject.

Provide references to literature and published sources if you are required to integrate these into your site visit report.

Write up your findings as soon as possible after your site visit. The sooner you write your report, the more you’ll remember.

Reflection / Observation

If you are asked to write a reflection of your visit, try to:

- Make links between theory and practice, i.e. what you’ve been doing in your subject, what you’ve read, any previous professional experience you have in the field and the practices you observed at the site.

- Demonstrate in your reflection that you understood the most important features of the site.

- Evaluate and discuss the relative strengths and weaknesses of the processes and procedures you observed (e.g. technology, efficiency).

A site visit is far more than an excursion or trip. It is an excellent opportunity to gain insights into how your area of study operates in practice, and if you adequately prepare to collect extensive information during your visit, you will be able to produce a higher quality report or assessment as well.

Looking for one-on-one advice?

Get tailored advice from an Academic Skills Adviser by booking an Individual appointment, or get quick feedback from one of our Academic Writing Mentors via email through our Writing advice service.

Go to Student appointments

How to Write a Library Report

Patricia harrelson.

College faculty often encourage students to become proficient, comfortable users of the library. In addition to requiring students to complete a research project, they also expect students to use the library to explore difficult or intriguing topics from a lecture or the course reading. According to Peter Suber, philosophy instructor at Earlham College, students should visit “the library routinely to find scholarship that clarifies difficult passages in the reading, answers background questions, or deepens . . . understanding of a fascinating idea.” Suber, like other college instructors, assigns a library report to assess students’ engagement with the library.

Maintain a record of you library visits in a notebook or on note cards.

Note the topics you explore and sources you consult.

Consult books, book chapters and journal articles in addition to web sites, dictionaries and encyclopedias. Also seek students and library staff with whom you can consult.

Write summaries and/or responses about the material you consider and the people with whom you speak. You may wish to write an in-depth analysis of one or two sources.

Organize your notes by visit, topic or alphabetically by source and then write a brief commentary about each entry. Commentary might include a summary of a pertinent resources, a description of two opposing views, clarification of a difficult topic, background information or analysis and exposition of a source.

Type the final report.

About the Author

Patricia Harrelson is a retired college English instructor who began writing in 1987. She writes about education, communication and theater in publications such as the "San Francisco Chronicle," "California English" and "Central Sierra Seasons." She specializes in Web content, including blogging for businesses. Harrelson has a Master of Science in speech pathology, and a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing from Antioch University.

Related Articles

Instructions for How to Write a Report

How to Study the King James Bible

True or False: Mars Edition

How to Teach Library Skills to Middle School Students

What is a Dissertation?

Questions to Ask While Writing a Research Paper

How to Prepare & Write an Informational Report

What Is a Scholarly Source?

How to Write a Thesis Statement for an Article Critique

How to Critique a Book for High School Students

How to Write a Suitable Objective Report

How to Gather Information for a Report

How to Write a Summary Paper in MLA Format

How to Write a Report for College Classes

The Advantages of an Annotated Bibliography

What Is the Difference Between AP English Literature...

How to Evaluate Research Articles

The Difference Between an Abstract & a Full-Text Article

How Can One Tell if Information Is Credible?

SQ3R Reading Technique for Elementary & High School...

Regardless of how old we are, we never stop learning. Classroom is the educational resource for people of all ages. Whether you’re studying times tables or applying to college, Classroom has the answers.

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright Policy

- Manage Preferences

© 2020 Leaf Group Ltd. / Leaf Group Media, All Rights Reserved. Based on the Word Net lexical database for the English Language. See disclaimer .

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

The purpose of a field report in the social sciences is to describe the deliberate observation of people, places, and/or events and to analyze what has been observed in order to identify and categorize common themes in relation to the research problem underpinning the study. The content represents the researcher's interpretation of meaning found in data that has been gathered during one or more observational events.

Flick, Uwe. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection . London: SAGE Publications, 2018; Lofland, John, David Snow, Leon Anderson, and Lyn H. Lofland. Analyzing Social Settings: A Guide to Qualitative Observation and Analysis. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, 2022; Baker, Lynda. "Observation: A Complex Research Method." Library Trends 55 (Summer 2006): 171-189.; Kellehear, Allan. The Unobtrusive Researcher: A Guide to Methods . New York: Routledge, 2020.

How to Approach Writing a Field Report

How to Begin

Field reports are most often assigned in disciplines of the applied social sciences [e.g., social work, anthropology, gerontology, criminal justice, education, law, the health care services] where it is important to build a bridge of relevancy between the theoretical concepts learned in the classroom and the practice of actually doing the work you are being taught to do. Field reports are also common in certain science disciplines [e.g., geology] but these reports are organized differently and serve a different purpose than what is described below.

Professors will assign a field report with the intention of improving your understanding of key theoretical concepts by applying methods of careful and structured observation of, and reflection about, people, places, or phenomena existing in their natural settings. Field reports facilitate the development of data collection techniques and observation skills and they help you to understand how theory applies to real world situations. Field reports are also an opportunity to obtain evidence through methods of observing professional practice that contribute to or challenge existing theories.

We are all observers of people, their interactions, places, and events; however, your responsibility when writing a field report is to conduct research based on data generated by the act of designing a specific study, deliberate observation, synthesis of key findings, and interpretation of their meaning.

When writing a field report you need to:

- Systematically observe and accurately record the varying aspects of a situation . Always approach your field study with a detailed protocol about what you will observe, where you should conduct your observations, and the method by which you will collect and record your data.

- Continuously analyze your observations . Always look for the meaning underlying the actions you observe. Ask yourself: What's going on here? What does this observed activity mean? What else does this relate to? Note that this is an on-going process of reflection and analysis taking place for the duration of your field research.

- Keep the report’s aims in mind while you are observing . Recording what you observe should not be done randomly or haphazardly; you must be focused and pay attention to details. Enter the observation site [i.e., "field"] with a clear plan about what you are intending to observe and record in relation to the research problem while, at the same time, being prepared to adapt to changing circumstances as they may arise.

- Consciously observe, record, and analyze what you hear and see in the context of a theoretical framework . This is what separates data gatherings from reporting. The theoretical framework guiding your field research should determine what, when, and how you observe and act as the foundation from which you interpret your findings in relation to the underlying assumptions embedded in the theoretical framework .

Techniques to Record Your Observations Although there is no limit to the type of data gathering techniques you can use, these are the most frequently used methods:

Note Taking This is the most common and easiest method of recording your observations. Tips for taking notes include: organizing some shorthand symbols beforehand so that recording basic or repeated actions does not impede your ability to observe, using many small paragraphs, which reflect changes in activities, who is talking, etc., and, leaving space on the page so you can write down additional thoughts and ideas about what’s being observed, any theoretical insights, and notes to yourself that are set aside for further investigation. See drop-down tab for additional information about note-taking.

Photography With the advent of smart phones, an almost unlimited number of high quality photographs can be taken of the objects, events, and people observed during a field study. Photographs can help capture an important moment in time as well as document details about the space where your observation takes place. Taking a photograph can save you time in documenting the details of a space that would otherwise require extensive note taking. However, be aware that flash photography could undermine your ability to observe unobtrusively so assess the lighting in your observation space; if it's too dark, you may need to rely on taking notes. Also, you should reject the idea that photographs represent some sort of "window into the world" because this assumption creates the risk of over-interpreting what they show. As with any product of data gathering, you are the sole instrument of interpretation and meaning-making, not the object itself. Video and Audio Recordings Video or audio recording your observations has the positive effect of giving you an unfiltered record of the observation event. It also facilitates repeated analysis of your observations. This can be particularly helpful as you gather additional information or insights during your research. However, these techniques have the negative effect of increasing how intrusive you are as an observer and will often not be practical or even allowed under certain circumstances [e.g., interaction between a doctor and a patient] and in certain organizational settings [e.g., a courtroom]. Illustrations/Drawings This does not refer to an artistic endeavor but, rather, refers to the possible need, for example, to draw a map of the observation setting or illustrating objects in relation to people's behavior. This can also take the form of rough tables, charts, or graphs documenting the frequency and type of activities observed. These can be subsequently placed in a more readable format when you write your field report. To save time, draft a table [i.e., columns and rows] on a separate piece of paper before an observation if you know you will be entering data in that way.

NOTE: You may consider using a laptop or other electronic device to record your notes as you observe, but keep in mind the possibility that the clicking of keys while you type or noises from your device can be obtrusive, whereas writing your notes on paper is relatively quiet and unobtrusive. Always assess your presence in the setting where you're gathering the data so as to minimize your impact on the subject or phenomenon being studied.

ANOTHER NOTE: Techniques of deliberate observation and data gathering are not innate skills; they are skills that must be learned and practiced in order to achieve proficiency. Before your first observation, practice the technique you plan to use in a setting similar to your study site [e.g., take notes about how people choose to enter checkout lines at a grocery store if your research involves examining the choice patterns of unrelated people forced to queue in busy social settings]. When the act of data gathering counts, you'll be glad you practiced beforehand.

YET ANOTHER NOTE: An issue rarely discussed in the literature about conducting field research is whether you should move around the study site while observing or remaining situated in one place. Moving around can be intrusive, but it facilitates observing people's behavior from multiple vectors. However, if you remain in one place throughout the observation [or during each observation], you will eventually blend into the background and diminish the chance of unintentionally influencing people's behavior. If the site has a complex set of interactions or interdependent activities [e.g., a play ground], consider moving around; if the study site is relatively fixed [e.g., a classroom], then consider staying in one place while observing.

Examples of Things to Document While Observing

- Physical setting . The characteristics of an occupied space and the human use of the place where the observation(s) are being conducted.

- Objects and material culture . This refers to the presence, placement, and arrangement of objects that impact the behavior or actions of those being observed. If applicable, describe the cultural artifacts representing the beliefs [i.e., the values, ideas, attitudes, and assumptions] of the individuals you are observing [e.g., the choice of particular types of clothing in the observation of family gatherings during culturally specific holidays].

- Use of language . Don't just observe but listen to what is being said, how is it being said, and the tone of conversations among participants.

- Behavior cycles . This refers to documenting when and who performs what behavior or task and how often they occur. Record at which stage this behavior is occurring within the setting.

- The order in which events unfold . Note sequential patterns of behavior or the moment when actions or events take place and their significance. Also, be prepared to note moments that diverge from these sequential patterns of behavior or actions.

- Physical characteristics of subjects. If relevant, document personal characteristics of individuals being observed. Note that, unless this data can be verified in interviews or from documentary evidence, you should only focus on characteristics that can be clearly observed [e.g., clothing, physical appearance, body language].

- Expressive body movements . This would include things like body posture or facial expressions. Note that it may be relevant to also assess whether expressive body movements support or contradict the language used in conversation [e.g., detecting sarcasm].

Brief notes about all of these examples contextualize your observations; however, your observation notes will be guided primarily by your theoretical framework, keeping in mind that your observations will feed into and potentially modify or alter these frameworks.

Sampling Techniques

Sampling refers to the process used to select a portion of the population for study . Qualitative research, of which observation is one method of data gathering, is generally based on non-probability and purposive sampling rather than probability or random approaches characteristic of quantitatively-driven studies. Sampling in observational research is flexible and often continues until no new themes emerge from the data, a point referred to as data saturation.

All sampling decisions are made for the explicit purpose of obtaining the richest possible source of information to answer the research questions. Decisions about sampling assumes you know what you want to observe, what behaviors are important to record, and what research problem you are addressing before you begin the study. These questions determine what sampling technique you should use, so be sure you have adequately answered them before selecting a sampling method.

Ways to sample when conducting an observation include:

- Ad Libitum Sampling -- this approach is not that different from what people do at the zoo; they observe whatever seems interesting at the moment. There is no organized system of recording the observations; you just note whatever seems relevant at the time. The advantage of this method is that you are often able to observe relatively rare or unusual behaviors that might be missed by more deliberately designed sampling methods. This method is also useful for obtaining preliminary observations that can be used to develop your final field study. Problems using this method include the possibility of inherent bias toward conspicuous behaviors or individuals, thereby missing mundane or repeated patterns of behavior, and that you may miss brief interactions in social settings.

- Behavior Sampling -- this involves watching the entire group of subjects and recording each occurrence of a specific behavior of interest and with reference to which individuals were involved. The method is useful in recording rare behaviors missed by other sampling methods and is often used in conjunction with focal or scan methods [see below]. However, sampling can be biased towards particular conspicuous behaviors.

- Continuous Recording -- provides a faithful record of behavior including frequencies, durations, and latencies [the time that elapses between a stimulus and the response to it]. This is a very demanding method because you are trying to record everything within the setting and, thus, measuring reliability may be sacrificed. In addition, durations and latencies are only reliable if subjects remain present throughout the collection of data. However, this method facilitates analyzing sequences of behaviors and ensures obtaining a wealth of data about the observation site and the people within it. The use of audio or video recording is most useful with this type of sampling.

- Focal Sampling -- this involves observing one individual for a specified amount of time and recording all instances of that individual's behavior. Usually you have a set of predetermined categories or types of behaviors that you are interested in observing [e.g., when a teacher walks around the classroom] and you keep track of the duration of those behaviors. This approach doesn't tend to bias one behavior over another and provides significant detail about a individual's behavior. However, with this method, you likely have to conduct a lot of focal samples before you have a good idea about how group members interact. It can also be difficult within certain settings to keep one individual in sight for the entire period of the observation without being intrusive.

- Instantaneous Sampling -- this is where observation sessions are divided into short intervals divided by sample points. At each sample point the observer records if predetermined behaviors of interest are taking place. This method is not effective for recording discrete events of short duration and, frequently, observers will want to record novel behaviors that occur slightly before or after the point of sampling, creating a sampling error. Though not exact, this method does give you an idea of durations and is relatively easy to do. It is also good for recording behavior patterns occurring at a specific instant, such as, movement or body positions.

- One-Zero Sampling -- this is very similar to instantaneous sampling, only the observer records if the behaviors of interest have occurred at any time during an interval instead of at the instant of the sampling point. The method is useful for capturing data on behavior patterns that start and stop repeatedly and rapidly, but that last only for a brief period of time. The disadvantage of this approach is that you get a dimensionless score for an entire recording session, so you only get one one data point for each recording session.

- Scan Sampling -- this method involves taking a census of the entire observed group at predetermined time periods and recording what each individual is doing at that moment. This is useful for obtaining group behavioral data and allows for data that are evenly representative across individuals and periods of time. On the other hand, this method may be biased towards more conspicuous behaviors and you may miss a lot of what is going on between observations, especially rare or unusual behaviors. It is also difficult to record more than a few individuals in a group setting without missing what each individual is doing at each predetermined moment in time [e.g., children sitting at a table during lunch at school]. The use of audio or video recording is useful with this type of sampling.

Alderks, Peter. Data Collection. Psychology 330 Course Documents. Animal Behavior Lab. University of Washington; Emerson, Robert M. Contemporary Field Research: Perspectives and Formulations . 2nd ed. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, 2001; Emerson, Robert M. et al. “Participant Observation and Fieldnotes.” In Handbook of Ethnography . Paul Atkinson et al., eds. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2001), 352-368; Emerson, Robert M. et al. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes . 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011; Ethnography, Observational Research, and Narrative Inquiry. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Hazel, Spencer. "The Paradox from Within: Research Participants Doing-Being-Observed." Qualitative Research 16 (August 2016): 446-457; Pace, Tonio. Writing Field Reports. Scribd Online Library; Presser, Jon and Dona Schwartz. “Photographs within the Sociological Research Process.” In Image-based Research: A Sourcebook for Qualitative Researchers . Jon Prosser, editor (London: Falmer Press, 1998), pp. 115-130; Pyrczak, Fred and Randall R. Bruce. Writing Empirical Research Reports: A Basic Guide for Students of the Social and Behavioral Sciences . 5th ed. Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Publishing, 2005; Report Writing. UniLearning. University of Wollongong, Australia; Wolfinger, Nicholas H. "On Writing Fieldnotes: Collection Strategies and Background Expectancies.” Qualitative Research 2 (April 2002): 85-95; Writing Reports. Anonymous. The Higher Education Academy.

Structure and Writing Style

How you choose to format your field report is determined by the research problem, the theoretical framework that is driving your analysis, the observations that you make, and/or specific guidelines established by your professor. Since field reports do not have a standard format, it is worthwhile to determine from your professor what the preferred structure and organization should be before you begin to write. Note that field reports should be written in the past tense. With this in mind, most field reports in the social sciences include the following elements:

I. Introduction The introduction should describe the research problem, the specific objectives of your research, and the important theories or concepts underpinning your field study. The introduction should describe the nature of the organization or setting where you are conducting the observation, what type of observations you have conducted, what your focus was, when you observed, and the methods you used for collecting the data. Collectively, this descriptive information should support reasons why you chose the observation site and the people or events within it. You should also include a review of pertinent literature related to the research problem, particularly if similar methods were used in prior studies. Conclude your introduction with a statement about how the rest of the paper is organized.

II. Description of Activities

Your readers only knowledge and understanding of what happened will come from the description section of your report because they were not witnesses to the situation, people, or events that you are writing about. Given this, it is crucial that you provide sufficient details to place the analysis that will follow into proper context; don't make the mistake of providing a description without context. The description section of a field report is similar to a well written piece of journalism. Therefore, a useful approach to systematically describing the varying aspects of an observed situation is to answer the "Five W’s of Investigative Reporting." As Dubbels notes [p. 19], these are:

- What -- describe what you observed. Note the temporal, physical, and social boundaries you imposed to limit the observations you made. What were your general impressions of the situation you were observing. For example, as a student teacher, what is your impression of the application of iPads as a learning device in a history class; as a cultural anthropologist, what is your impression of women's participation in a Native American religious ritual?

- Where -- provide background information about the setting of your observation and, if necessary, note important material objects that are present that help contextualize the observation [e.g., arrangement of computers in relation to student engagement with the teacher].

- When -- record factual data about the day and the beginning and ending time of each observation. Note that it may also be necessary to include background information or key events which impact upon the situation you were observing [e.g., observing the ability of teachers to re-engage students after coming back from an unannounced fire drill].

- Who -- note background and demographic information about the individuals being observed e.g., age, gender, ethnicity, and/or any other variables relevant to your study]. Record who is doing what and saying what, as well as, who is not doing or saying what. If relevant, be sure to record who was missing from the observation.

- Why -- why were you doing this? Describe the reasons for selecting particular situations to observe. Note why something happened. Also note why you may have included or excluded certain information.

III. Interpretation and Analysis

Always place the analysis and interpretations of your field observations within the larger context of the theoretical assumptions and issues you described in the introduction. Part of your responsibility in analyzing the data is to determine which observations are worthy of comment and interpretation, and which observations are more general in nature. It is your theoretical framework that allows you to make these decisions. You need to demonstrate to the reader that you are conducting the field work through the eyes of an informed viewer and from the perspective of a casual observer.

Here are some questions to ask yourself when analyzing your observations:

- What is the meaning of what you have observed?

- Why do you think what you observed happened? What evidence do you have for your reasoning?

- What events or behaviors were typical or widespread? If appropriate, what was unusual or out of the ordinary? How were they distributed among categories of people?

- Do you see any connections or patterns in what you observed?

- Why did the people you observed proceed with an action in the way that they did? What are the implications of this?

- Did the stated or implicit objectives of what you were observing match what was achieved?

- What were the relative merits of the behaviors you observed?

- What were the strengths and weaknesses of the observations you recorded?

- Do you see connections between what you observed and the findings of similar studies identified from your review of the literature?

- How do your observations fit into the larger context of professional practice? In what ways have your observations possibly changed or affirmed your perceptions of professional practice?

- Have you learned anything from what you observed?

NOTE: Only base your interpretations on what you have actually observed. Do not speculate or manipulate your observational data to fit into your study's theoretical framework.

IV. Conclusion and Recommendations

The conclusion should briefly recap of the entire study, reiterating the importance or significance of your observations. Avoid including any new information. You should also state any recommendations you may have based on the results of your study. Be sure to describe any unanticipated problems you encountered and note the limitations of your study. The conclusion should not be more than two or three paragraphs.

V. Appendix

This is where you would place information that is not essential to explaining your findings, but that supports your analysis [especially repetitive or lengthy information], that validates your conclusions, or that contextualizes a related point that helps the reader understand the overall report. Examples of information that could be included in an appendix are figures/tables/charts/graphs of results, statistics, pictures, maps, drawings, or, if applicable, transcripts of interviews. There is no limit to what can be included in the appendix or its format [e.g., a DVD recording of the observation site], provided that it is relevant to the study's purpose and reference is made to it in the report. If information is placed in more than one appendix ["appendices"], the order in which they are organized is dictated by the order they were first mentioned in the text of the report.

VI. References

List all sources that you consulted and obtained information from while writing your field report. Note that field reports generally do not include further readings or an extended bibliography. However, consult with your professor concerning what your list of sources should be included and be sure to write them in the preferred citation style of your discipline or is preferred by your professor [i.e., APA, Chicago, MLA, etc.].

Alderks, Peter. Data Collection. Psychology 330 Course Documents. Animal Behavior Lab. University of Washington; Dubbels, Brock R. Exploring the Cognitive, Social, Cultural, and Psychological Aspects of Gaming and Simulations . Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2018; Emerson, Robert M. Contemporary Field Research: Perspectives and Formulations . 2nd ed. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, 2001; Emerson, Robert M. et al. “Participant Observation and Fieldnotes.” In Handbook of Ethnography . Paul Atkinson et al., eds. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2001), 352-368; Emerson, Robert M. et al. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes . 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011; Ethnography, Observational Research, and Narrative Inquiry. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Pace, Tonio. Writing Field Reports. Scribd Online Library; Pyrczak, Fred and Randall R. Bruce. Writing Empirical Research Reports: A Basic Guide for Students of the Social and Behavioral Sciences . 5th ed. Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Publishing, 2005; Report Writing. UniLearning. University of Wollongong, Australia; Wolfinger, Nicholas H. "On Writing Fieldnotes: Collection Strategies and Background Expectancies.” Qualitative Research 2 (April 2002): 85-95; Writing Reports. Anonymous. The Higher Education Academy.

- << Previous: Writing a Case Study

- Next: About Informed Consent >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

How to Write a Library Report

Instructions

Make up your mind You need a positive mindset before going to the library. If you are doing it as a formality, it will not help you at all and the teachers won’t be inspired by your report. So, go with a purpose of gaining knowledge and the results will be good for you eventually.

Enlist the topics you wish to search There will be quite a few topics, which you will be looking to search. So, make a list of them all, and keep it with you when you enter the library.

Note your visiting frequency Another important thing is to keep record of the number of visits you are paying to the library. Moreover, mention the average time spent in the library as well.

Consult friends If you are new to the library, consult friends who visit regularly, as they will guide you how to search for relevant topics.

Type the report Once you have pointed out everything you do in the library, type it down and present the final report to your instructor.

- Print Article

People Who Read This Also Read:

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Prove You\'re Human * − 6 = two

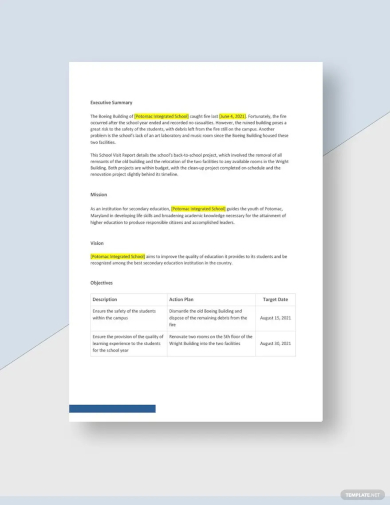

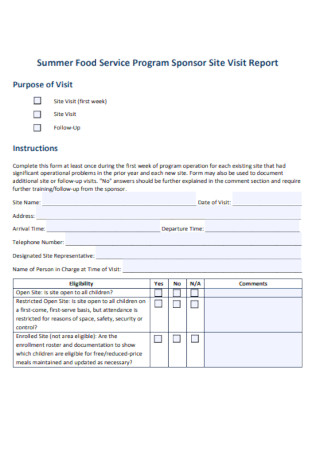

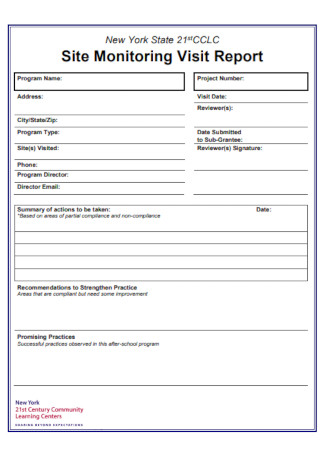

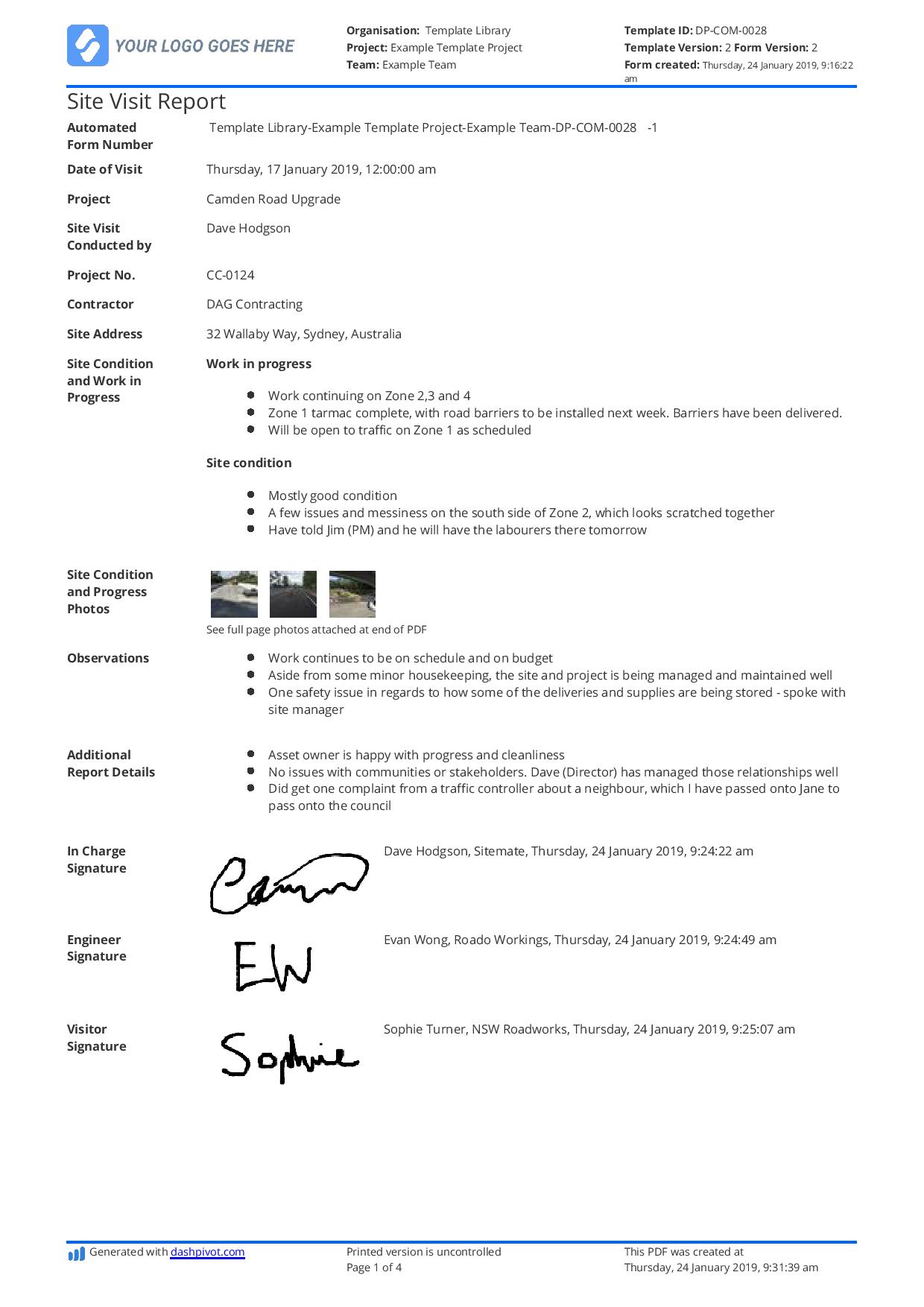

33+ SAMPLE Visit Report Templates in Google Docs | Pages | PDF | MS Word

Visit report templates in google docs | pages | pdf | ms word, 33+ sample visit report templates, what is a visit report, the basic format of a visit report, how to write a proper visit report, what are some examples of a visit report, how many pages does a visit report have, what is a trip report memo.

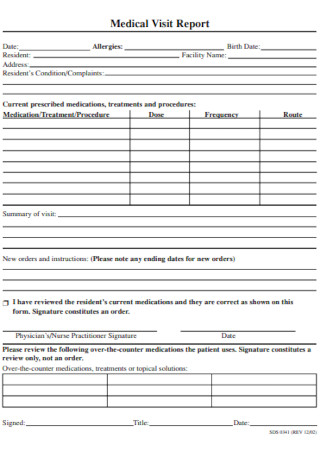

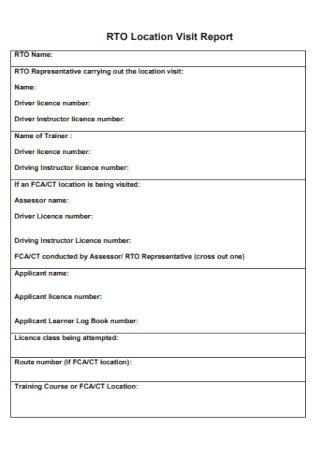

Visit Report Template

Sample School Visit Report

Customer Visit Report Template

Field Visit Report

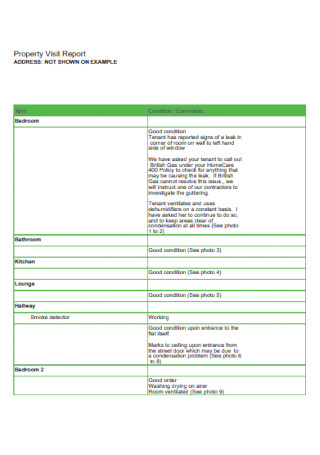

Sample Site Visit Report

Customer Visit Report Outline

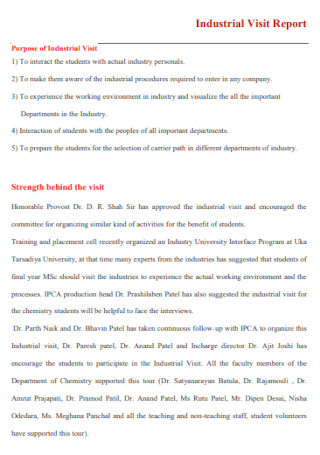

Sample Industry Visit Report

New Customer Visit Report Template

Construction Site Visit Report

Sample Customer Visit Report

Free School Visit Report Template

Sample Official Overseas Visit Report

Weekly Site Visit Report

Project Field Visit Report

Recommendation Study Visit Report

Observation Site Visit Reports for Engineers

Simple Industrial Visit Report

School Lab Visit Analysis Report

Building Construction Property Visit Report

Medical College Visit Report

Sample Location Visit Report

Monitoring Visit Report Summary

Marketing Team Site Visit Report

School Academic Visit Report Template

Chemical Exposure Visit Report

Business Renewal Site Visit Report

Management Conference Visit Report

Pre-Event Site Visit Report Example in PDF

Sample Parent Visit Report Format

Home Tour Visit Report Template

Report of Research Visit

Daily Food Sponsor Visit Report Example

Sample Civil Site Monitoring Visit Report

Why Are Visit Reports Important?

Step 1: determine your purpose, step 2: be observant and write what happened, step 3: reflect on your visit, step 4: download a template and insert the details, step 5: organize details according to the format.

- Site visit report

- Business visit report

- Field trip visit report

- Industrial visit report

- Monitoring visit report

Share This Post on Your Network

File formats, word templates, google docs templates, excel templates, powerpoint templates, google sheets templates, google slides templates, pdf templates, publisher templates, psd templates, indesign templates, illustrator templates, pages templates, keynote templates, numbers templates, outlook templates, you may also like these articles, 12+ sample construction daily report in ms word | pdf.

Introducing our comprehensive sample Construction Daily Report the cornerstone of effective project management in the construction industry. With this easy-to-use report, you'll gain valuable insights into daily activities report,…

25+ SAMPLE Food Safety Reports in PDF | MS Word

Proper food handling ensures that the food we intake is clean and safe. If not, then we expose ourselves to illnesses and food poisoning. Which is why a thorough…

browse by categories

- Questionnaire

- Description

- Reconciliation

- Certificate

- Spreadsheet

Information

- privacy policy

- Terms & Conditions

CC0006 Basics of Report Writing

- Structure of a report (Case study, Literature review or Survey)

- Structure of report (Site visit)

Structure of a report (Site visit)

- Citing Sources

- Tips and Resources

A site visit methodology may look like this: you visit a site for a limited period of time and gather information through your own experience or through the reported experiences of others in order to find the answer to your research question. In addition to observation, interviews can also be employed to gather information.

For example, a site visit to clean energy buildings and conduct an analysis of the associated technology / policy approaches. Add a section on the feasibility of more such buildings, compare it with other such buildings across the world, etc.

The report structure of a site visit based project is slightly different from that of a case study. literature review or survey.

Structure of a report for the site visit method is as follows.

- Table of Contents

- Summary / Abstract

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Information about the site(s)

- Field Observations

- Reflection of visit experience and Implication(s)

- Discussion and Limitation(s)

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- Appendix (if necessary/any)

Please access Structure of a report (Case study, Literature review or Survey) to know more about other sections.

- << Previous: Structure of a report (Case study, Literature review or Survey)

- Next: Citing Sources >>

- Last Updated: Jan 12, 2024 11:52 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ntu.edu.sg/report-writing

You are expected to comply with University policies and guidelines namely, Appropriate Use of Information Resources Policy , IT Usage Policy and Social Media Policy . Users will be personally liable for any infringement of Copyright and Licensing laws. Unless otherwise stated, all guide content is licensed by CC BY-NC 4.0 .

Organizing Academic Research Papers: Writing a Field Report

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Executive Summary

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tertiary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Annotated Bibliography

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- How to Manage Group Projects

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Essays

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Acknowledgements

Field reports require the researcher to combine theory and analysis learned in the classroom with methods of observation and practice applied outside of the classroom. The purpose of field reports is to describe an observed person, place, or event and to analyze that observation data in order to identify and categorize common themes in relation to the research problem(s) underpinning the study. The data is often in the form of notes taken during the observation but it can also include any form of data gathering, such as, photography, illustrations, or audio recordings.

How to Approach Writing a Field Report

How to Begin

Field reports are most often assigned in the applied social sciences [e.g., social work, anthropology, gerontology, criminal justice, education, law, the health care professions] where it is important to build a bridge of relevancy between the theoretical concepts learned in the classroom and the practice of actually doing the work you are being taught to do. Field reports are also common in certain science and technology disciplines [e.g., geology] but these reports are organized differently and for different purposes than what is described below.

Professors will assign a field report with the intention of improving your understanding of key theoretical concepts through a method of careful and structured observation of and reflection about real life practice. Field reports facilitate the development of data collection techniques and observation skills and allow you to understand how theory applies to real world situations. Field reports are also an opportunity to obtain evidence through methods of observing professional practice that challenge or refine existing theories.

We are all observers of people, their interactions, places, and events; however, your responsibility when writing a field report is to create a research study based on data generated by the act of observation, a synthesis of key findings, and an interpretation of their meaning. When writing a field report you need to:

- Systematically observe and accurately record the varying aspects of a situation . Always approach your field study with a detailed plan about what you will observe, where you should conduct your observations, and the method by which you will collect and record your data.

- Continuously analyze your observations . Always look for the meaning underlying the actions you observe. Ask yourself: What's going on here? What does this observed activity mean? What else does this relate to? Note that this is an on-going process of reflection and analysis taking place for the duration of your field research.

- Keep the report’s aims in mind while you are observing . Recording what you observe should not be done randomly or haphazardly; you must be focused and pay attention to details. Enter the field with a clear plan about what you are intending to observe and record while, at the same time, be prepared to adapt to changing circumstances as they may arise.

- Consciously observe, record, and analyze what you hear and see in the context of a theoretical framework . This is what separates data gatherings from simple reporting. The theoretical framework guiding your field research should determine what, when, and how you observe and act as the foundation from which you interpret your findings.

Techniques to Record Your Observations Note Taking This is the most commonly used and easiest method of recording your observations. Tips for taking notes include: organizing some shorthand symbols beforehand so that recording basic or repeated actions does not impede your ability to observe, using many small paragraphs, which reflect changes in activities, who is talking, etc., and, leaving space on the page so you can write down additional thoughts and ideas about what’s being observed, any theoretical insights, and notes to yourself about may require further investigation. See drop-down tab for additional information about note-taking. Video and Audio Recordings Video or audio recording your observations has the positive effect of giving you an unfiltered record of the observation event. It also facilitates repeated analysis of your observations. However, these techniques have the negative effect of increasing how intrusive you are as an observer and will often not be practical or even allowed under certain circumstances [e.g., interaction between a doctor and a patient] and in certain organizational settings [e.g., a courtroom]. Illustrations/Drawings This does not an artistic endeavor but, rather, refers to the possible need, for example, to draw a map of the observation setting or illustrating objects in relation to people's behavior. This can also take the form of rough tables or graphs documenting the frequency and type of activities observed. These can be subsequently placed in a more readable format when you write your field report.

Examples of Things to Document While Observing

- Physical setting . The characteristics of an occupied space and the human use of the place where the observation(s) are being conducted.

- Objects and material culture . The presence, placement, and arrangement of objects that impact the behavior or actions of those being observed. If applicable, describe the cultural artifacts representing the beliefs--values, ideas, attitudes, and assumptions--used by the individuals you are observing.

- Use of language . Don't just observe but listen to what is being said, how is it being said, and, the tone of conversation among participants.

- Behavior cycles . This refers to documenting when and who performs what behavior or task and how often they occur. Record at which stage is this behavior occurring within the setting.

- The order in which events unfold . Note sequential patterns of behavior or the moment when actions or events take place and their significance.

- Physical characteristics of subjects. If relevant, note age, gender, clothing, etc. of individuals.

- Expressive body movements . This would include things like body posture or facial expressions. Note that it may be relevant to also assess whether expressive body movements support or contradict the use of language.

Brief notes about all of these examples contextualize your observations; however, your observation notes will be guided primarily by your theoretical framework, keeping in mind that your observations will feed into and potentially modify or alter these frameworks.

Sampling Techniques

Sampling refers to the process used to select a portion of the population for study . Qualitative research, of which observation is one method, is generally based on non-probability and purposive sampling rather than probability or random approaches characteristic of quantitatively-driven studies. Sampling in observational research is flexible and often continues until no new themes emerge from the data, a point referred to as data saturation.

All sampling decisions are made for the explicit purpose of obtaining the richest possible source of information to answer the research questions. Decisions about sampling assumes you know what you want to observe, what behaviors are important to record, and what research problem you are addressing before you begin the study. These questions determine what sampling technique you should use, so be sure you have adequately answered them before selecting a sampling method.

Ways to sample when conducting an observation include:

Ad Libitum Sampling -- this approach is not that different from what people do at the zoo--observing whatever seems interesting at the moment. There is no organized system of recording the observations; you just note whatever seems relevant at the time. The advantage of this method is that you are often able to observe relatively rare or unusual behaviors that might be missed by more deliberate sampling methods. This method is also useful for obtaining preliminary observations that can be used to develop your final field study. Problems using this method include the possibility of inherent bias toward conspicuous behaviors or individuals and that you may miss brief interactions in social settings.

Behavior Sampling -- this involves watching the entire group of subjects and recording each occurance of a specific behavior of particular interest and with reference to which individuals were involved. The method is useful in recording rare behaviors missed by other sampling methods and is often used in conjunction with focal or scan methods. However, sampling can be biased towards particular conspicuous behaviors.

Continuous Recording -- provides a faithful record of behavior including frequencies, durations, and latencies [the time that elapses between a stimulus and the response to it]. This is a very demanding method because you are trying to record everything within the setting and, thus, measuring reliability may be sacrificed. In addition, durations and latencies are only reliable if subjects remain present throughout the collection of data. However, this method facilitates analyzing sequences of behaviors and ensures obtaining a wealth of data about the observation site and the people within it. The use of audio or video recording is most useful with this type of sampling.

Focal Sampling -- this involves observing one individual for a specified amount of time and recording all instances of that individual's behavior. Usually you have a set of predetermined categories or types of behaviors that you are interested in observing [e.g., when a teacher walks around the classroom] and you keep track of the duration of those behaviors. This approach doesn't tend to bias one behavior over another and provides significant detail about a individual's behavior. However, with this method, you likely have to conduct a lot of focal samples before you have a good idea about how group members interact. It can also be difficult within certain settings to keep one individual in sight for the entire period of the observation.

Instantaneous Sampling -- this is where observation sessions are divided into short intervals divided by sample points. At each sample point the observer records if predetermined behaviors of interest are taking place. This method is not effective for recording discrete events of short duration and, frequently, observers will want to record novel behaviors that occur slightly before or after the point of sampling, creating a sampling error. Though not exact, this method does give you an idea of durations and is relatively easy to do. It is also good for recording behavior patterns occurring at a specific instant, such as, movement or body positions.

One-Zero Sampling -- this is very similar to instantaneous sampling, only the observer records if the behaviors of interest have occurred at any time during an interval instead of at the instant of the sampling point. The method is useful for capturing data on behavior patterns that start and stop repeatedly and rapidly, but that last only for a brief period of time. The disadvantage of this approach is that you get a dimensionless score for an entire recording session, so you only get one one data point for each recording session.

Scan Sampling -- this method involves taking a census of the entire observed group at predetermined time periods and recording what each individual is doing at that moment. This is useful for obtaining group behavioral data and allows for data that are evenly representative across individuals and periods of time. On the other hand, this method may be biased towards more conspicuous behaviors and you may miss a lot of what is going on between observations, especially rare or unusual behaviors.

Alderks, Peter. Data Collection. Psychology 330 Course Documents. Animal Behavior Lab. University of Washington; Emerson, Robert M. Contemporary Field Research: Perspectives and Formulations. 2nd ed. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, 2001; Emerson, Robert M. et al. “Participant Observation and Fieldnotes.” In Handbook of Ethnography. Paul Atkinson et al., eds. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2001), 352-368; Emerson, Robert M. et al. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011; Ethnography, Observational Research, and Narrative Inquiry . Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Pace, Tonio. Writing Field Reports . Scribd Online Library; Pyrczak, Fred and Randall R. Bruce. Writing Empirical Research Reports: A Basic Guide for Students of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. 5th ed. Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Publishing, 2005; Report Writing . UniLearning. University of Wollongong, Australia; Wolfinger, Nicholas H. On Writing Fieldnotes: Collection Strategies and Background Expectancies.” Qualitative Research 2 (April 2002): 85-95; Writing Reports . Anonymous. The Higher Education Academy.

Structure and Writing Style

How you choose to format your field report is determined by the research problem, the theoretical perspective that is driving your analysis, the observations that you make, and/or specific guidelines established by your professor. Since field reports do not have a standard format, it is worthwhile to determine from your professor what the preferred organization should be before you begin to write. Note that field reports should be written in the past tense. With this in mind, most field reports in the social sciences include the following elements:

I. Introduction The introduction should describe the specific objective and important theories or concepts underpinning your field study. The introduction should also describe the nature of the organization or setting where you are conducting the observation, what type of observations you have conducted, what your focus was, when you observed, and the methods you used for collecting the data. You should also include a review of pertinent literature.

II. Description of Activities

Your readers only knowledge and understanding of what happened will come from the description section of your report because they have not been witness to the situation, people, or events that you are writing about. Given this, it is crucial that you provide sufficient details to place the analysis that will follow into proper context; don't make the mistake of providing a description without context. The description section of a field report is similar to a well written piece of journalism. Therefore, a helpful approach to systematically describing the varying aspects of an observed situation is to answer the "Five W’s of Investigative Reporting." These are:

- What -- describe what you observed. Note the temporal, physical, and social boundaries you imposed to limit the observations you made. What were your general impressions of the situation you were observing. For example, as a student teacher, what is your impression of the application of iPads as a learning device in a history class; as a cultural anthropologist, what is your impression of women participating in a Native American religious ritual?

- Where -- provide background information about the setting of your observation and, if necessary, note important material objects that are present that help contextualize the observation [e.g., arrangement of computers in relation to student engagement with the teacher].

- When -- record factual data about the day and the beginning and ending time of each observation. Note that it may also be necessary to include background information or key events which impact upon the situation you were observing [e.g., observing the ability of teachers to re-engage students after coming back from an unannounced fire drill].

- Who -- note the participants in the situation in terms of age, gender, ethnicity, and/or any other variables relevant to your study. Record who is doing what and saying what, as well as, who is not doing or saying what. If relevant, be sure to record who was missing from the observation.

- Why -- why were you doing this? Describe the reasons for selecting particular situations to observe. Note why something happened. Also note why you may have included or excluded certain information.

III. Interpretation and Analysis

Always place the analysis and interpretations of your field observations within the larger context of the theories and issues you described in the introduction. Part of your responsibility in analyzing the data is to determine which observations are worthy of comment and interpretation, and which observations are more general in nature. It is your theoretical framework that allows you to make these decisions. You need to demonstrate to the reader that you are looking at the situation through the eyes of an informed viewer, not as a lay person.

Here are some questions to ask yourself when analyzing your observations:

- What is the meaning of what you have observed?

- Why do you think what you observed happened? What evidence do you have for your reasoning?

- What events or behaviors were typical or widespread? If appropriate, what was unusual or out of ordinary? How were they distributed among categories of people?

- Do you see any connections or patterns in what you observed?

- Why did the people you observed proceed with an action in the way that they did? What are the implications of this?

- Did the stated or implicit objectives of what you were observing match what was achieved?

- What were the relative merits of the behaviors you observed?

- What were the strengths and weaknesses of the observations you recorded?

- Do you see connections between what you observed and the findings of similar studies identified from your review of the literature?

- How do your observations fit into the larger context of professional practice? In what ways have your observations possibly changed your perceptions of professional practice?

- Have you learned anything from what you observed?

NOTE: Only base your interpretations on what you have actually observed. Do not speculate or manipulate your observational data to fit into your study's theoretical framework.

IV. Conclusion and Recommendations