History of Now

The Intergalactic Battle of Ancient Rome

Hundreds of years before audiences fell in love with Star Wars, one writer dreamt of battles in space

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

Lorraine Boissoneault

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/aa/41/aa4163fc-5858-4be8-8023-ded44b977eb8/spiders-in-space-wr.jpg)

A long time ago, in a world not so far away, a young man who longed for adventure was swept up in a galactic war. Forced to choose between two sides in the deadly battle, he befriended a group of scrappy fighters who captained… three-headed vultures, giant fleas and space spiders?

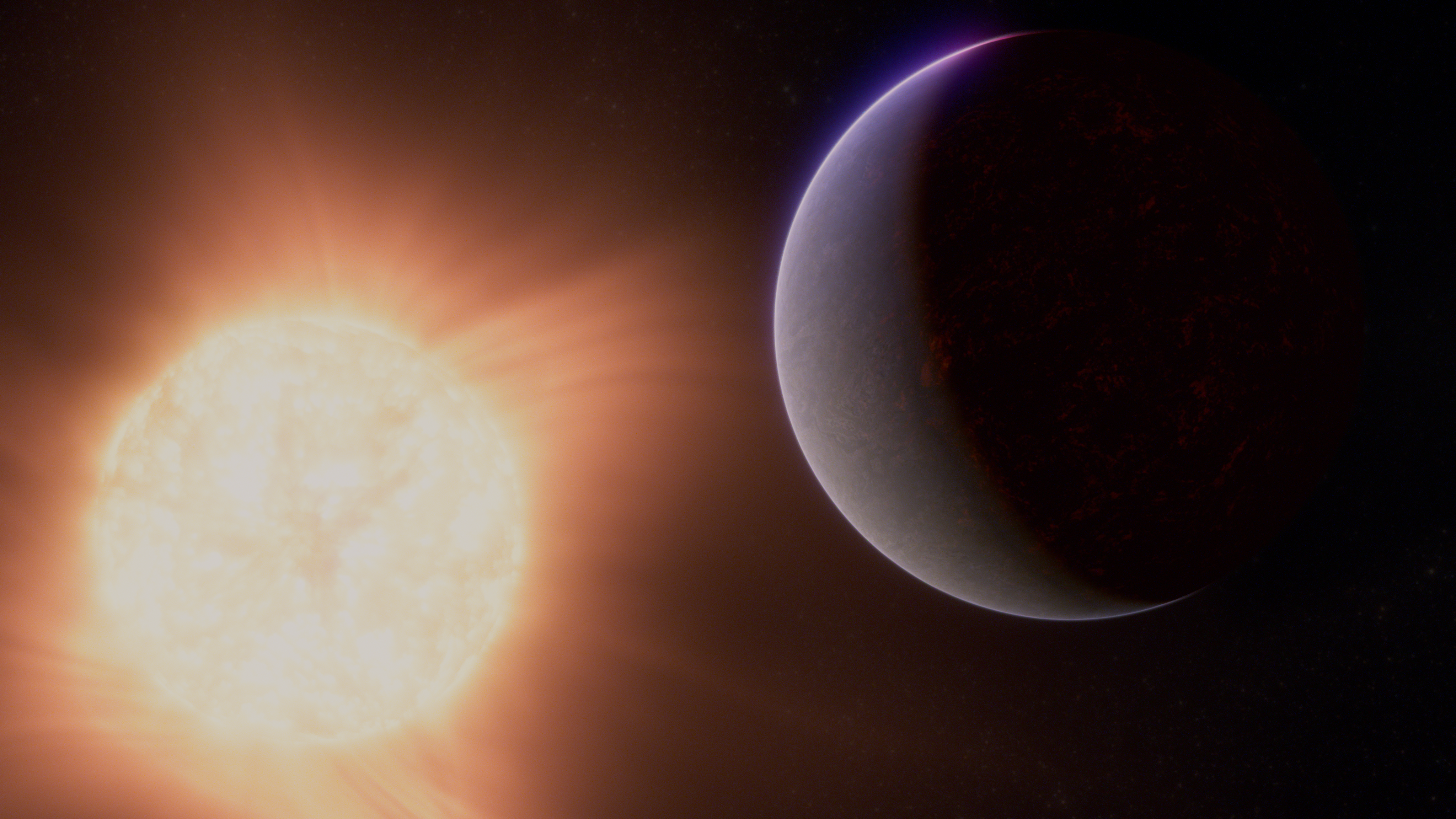

Nearly 2,000 years before George Lucas created his epic space opera Star Wars , Lucian of Samosata (a province in modern-day Turkey) wrote the world’s first novel featuring space travel and interplanetary battles. True History was published around 175 CE during the height of the Roman Empire. Lucian’s space adventure features a group of travelers who leave Earth when their ship is thrown into the sky by a ferocious whirlwind. After seven days of sailing through the air they arrive on the Moon, only to learn its inhabitants are at war with the people of the Sun. Both parties are fighting for control of a colony on the Morning Star (the planet we today call Venus). The warriors for the Sun and Moon armies travel through space on winged acorns and giant gnats and horses as big as ships, armed with outlandish weapons like slingshots that used enormous turnips as ammunition. Thousands die during the battle, and blood “[falls] upon the clouds, which made them look of a red color; as sometimes they appear to us about sun-setting,” Lucian wrote .

After the war’s conclusion, Lucian and his friends continue traveling through space, learning about the Moon’s odd inhabitants (an all-male society, whose anatomy included a single toe instead of a whole foot and children cut from their calves) before moving on to visit the Morning Star and other space cities.

Lucian was more of a satirist than a novelist; True History was written as a critique of philosophers and historians, and their ways of thinking about new discoveries. As scholar Roy Arthur Swanson writes , Lucian’s work provided “the perennially necessary reminder that thinking and believing are different and distinct kinds of mental activity and that it is best not to confuse them.”

But being a work of satire doesn’t preclude True History from joining the ranks of science fiction. In addition to showing first contact, wars in space, and a flight to the moon, the work’s satirical nature is actually yet another thing it has in common with the genre’s modern form.

“One of the consistent themes of sci-fi is satire, and making fun of the way humans live and run the world,” says Aaron Parrett, professor of English at University of Great Falls in Montana. “That is one reason why Lucian is so important. He did that very thing.”

Lucian was also likely aware of major scientific and philosophical research of his time, including Plutarch’s “ On the Face in the Orb of the Moon ,” and Ptolemy’s last recorded observation of the planets , which occurred 14 years prior to Lucian’s publication. Still, the astronomical telescope wasn’t invented until 1610, and Lucian’s narrative doesn’t feature scientifically sound space travel. Does that mean it doesn’t count as an early form of the genre?

It depends who you ask. Douglas Dunlop, who works as a metadata librarian at Smithsonian Libraries, sees parallels between Lucian’s writing and that of the later science fiction writers like Jules Verne and H.G. Wells.

“Just because it doesn’t have what we would call ‘modern science’ doesn’t take away from the fact that [philosophy and natural sciences] influenced the writing,” Dunlop says. “There was a theory called Plurality of Worlds that goes back to Greek Antiquity, which was the concept of life existing in space. So who’s to say what they were doing in their philosophy and observation wasn’t informing their understanding of the world around them?”

Other literary scholars have posited the world of science fiction starts with the Epic of Gilgamesh (2100 B.C.), Frankenstein (1818), or the works of Jules Verne (1850s). For famous American astronomer Carl Sagan , sci-fi starts with Johannes Kepler’s novel Somnium (1634), which describes a trip to the moon and the view of Earth seen from far away. But Kepler, as it turns out, was partially inspired by Lucian. He picked up True History in the original Greek to master the language. (While Latin was the vernacular of ancient Rome, Greek was the language used by the educated elite.) He wrote that his studies were improved by his enjoyment of the adventure, and it seems to have sent his imagination spinning as well. “These were my first traces of a trip to the moon, which was my aspiration at later times,” Kepler wrote .

Genre requirements aside, both True History and Star Wars offer ways of understanding and exploring the human world, even though the stories take place in the stars.

“One of the great things that science fiction does as a way of changing people’s worldview is show what the world might be like,” Parrett says. “It’s remarkable that people dreamed up things long before there was any possibility that they could do it. This is true not just of flying to the moon, but of flying in general.”

Lucian may never have believed humans would achieve flight to the moon—but he imagined it. And the path he laid for intergalactic stories continues to send writers, scientists and movie-goers dreaming of what might be out there, just beyond our reach.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

Lorraine Boissoneault | | READ MORE

Lorraine Boissoneault is a contributing writer to SmithsonianMag.com covering history and archaeology. She has previously written for The Atlantic, Salon, Nautilus and others. She is also the author of The Last Voyageurs: Retracing La Salle's Journey Across America. Website: http://www.lboissoneault.com/

In 1968, Apollo 8 realised the 2, 000-year -old dream of a Roman philosopher

Professor of Natural Philosophy in the Department of Physics, University of York

Disclosure statement

Tom McLeish receives funding from EPSRC, BBSRC, the National Formulation Centre and the Templeton World Charities Foundation.

University of York provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Half a century of Christmases ago, the NASA space mission Apollo 8 became the first manned craft to leave low Earth orbit, atop the unprecedentedly powerful Saturn V rocket, and head out to circumnavigate another celestial body, making 11 orbits of the moon before its return. The mission is often cast in a supporting role – a sort of warm up for the first moon landing. Yet for me, the voyage of Borman, Lovell and Anders six months before Neil Armstrong’s “small step for a man” will always be the great leap for humankind.

Apollo 8 is the space mission for the humanities, if ever there was one: this was the moment that humanity realised a dream conceived in our cultural imagination over two millennia ago. And like that first imagined journey into space, Apollo 8 also changed our moral perspective on the world forever.

In the first century BC, Roman statesman and philosopher Marcus Tullius Cicero penned a fictional dream attributed to the Roman general Scipio Aemilianus. The soldier is taken up into the sphere of distant stars to gaze back towards the Earth from the furthest reaches of the cosmos:

And as I surveyed them from this point, all the other heavenly bodies appeared to be glorious and wonderful — now the stars were such as we have never seen from this earth; and such was the magnitude of them all as we have never dreamed; and the least of them all was that planet, which farthest from the heavenly sphere and nearest to our earth, was shining with borrowed light, but the spheres of the stars easily surpassed the earth in magnitude — already the earth itself appeared to me so small, that it grieved me to think of our empire, with which we cover but a point, as it were, of its surface.

Earth-centric

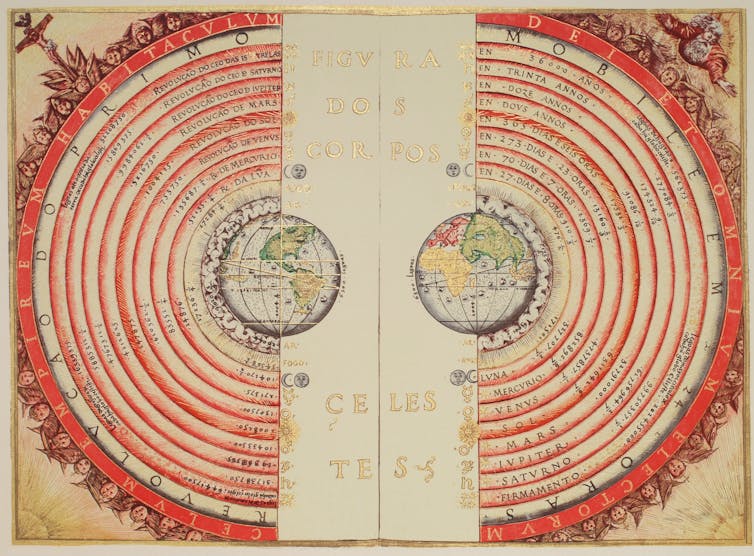

Even for those of us who are familiar with the ancient and medieval Earth-centred cosmology, with its concentric celestial spheres of sun, moon, planets and finally the stars wheeling around us in splendid eternal rotation, this comes as a shock. For the diagrams that illustrate pre-modern accounts of cosmology invariably show the Earth occupying a fair fraction of the entire universe.

Cicero’s text informs us right away that these illustrations are merely schematic, bearing as much relation to the actual imagined scale of the universe as today’s London Tube map does to the real geography of its tunnels. And his Dream of Scipio was by no means an arcane musing lost to history – becoming a major part of the canon for succeeding centuries. The fourth century Roman provincial scholar Macrobius built one of the great and compendious “commentaries” of late antiquity around it, ensuring its place in learning throughout the first millennium AD.

Cicero, and Macrobius after him, make two intrinsically-linked deductions. Today we would say that the first belongs to science, the second to the humanities, but, for ancient writers, knowledge was not so artificially fragmented. In Cicero’s text, Scipio first observes that the Earth recedes from this distance to a small sphere hardly distinguishable from a point. Second, he reflects that what we please to call great power is, on the scale of the cosmos, insignificant. Scipio’s companion remarks:

I see, that you are even now regarding the abode and habitation of mankind. And if this appears to you as insignificant as it really is, you will always look up to these celestial things and you won’t worry about those of men. For what renown among men, or what glory worth the seeking, can you acquire?

The vision of the Earth, hanging small and lowly in the vastness of space, generated an inversion of values for Cicero; a human humility. This also occurred in the case of the three astronauts of Apollo 8.

A change in perspective

There is a vast difference between lunar and Earth orbit – the destination of all earlier space missions. “Space” is not far away. The international space station orbits, as most manned missions, a mere 250 miles above our heads. We could drive that distance in half a day. The Earth fills half the sky from there, as it does for us on the ground.

But the moon is 250,000 miles distant. And so Apollo 8, in one firing of the S4B third stage engine to leave Earth orbit, increased the distance from Earth attained by a human being by not one order of magnitude, but three. From the moon, the Earth is a small glistening coin of blue, white and brown in the distant black sky.

So it was that, as their spacecraft emerged from the far side of its satellite, and they saw the Earth slowly rise over the bleak and barren horizon, the crew grabbed all cameras to hand and shot the now iconic “Earthrise” pictures that are arguably the great cultural legacy of the Apollo program. Intoning the first verses from the Book of Genesis as their Christmas message to Earth – “… and the Earth was without form, and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep…” – was their way of sharing the new questions that this perspective urges. As Lovell put it in an interview this year:

But suddenly, when you get out there and see the Earth as it really is, and when you realise that the Earth is only one of nine planets and it’s a mere speck in the Milky Way galaxy, and it’s lost to oblivion in the universe — I mean, we’re a nothing as far as the universe goes, or even our galaxy. So, you have to say, ‘Gee, how did I get here? Why am I here?’

The 20th century realisation of Scipio’s first century BC vision also energised the early stirrings of the environmental movement. When we have seen the fragility and unique compactness of our home in the universe, we know that we have one duty of care, and just one chance.

Space is the destiny of our imagination, and always has been, but Earth is our precious dwelling place. Cicero’s Dream, as well as its realisation in 1968, remind the world, fresh from the Poland climate talks, that what we do with our dreams today will affect generations to come.

- History of science

- Interdisciplinarity

Events and Communications Coordinator

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Space traveller venerated by the Romans (7)

I believe the answer is:

' space traveller ' is the definition. The definition and answer can be both people as well as being singular nouns. Maybe there's a link between them I don't understand? I don't understand how the rest of the clue works.

Can you help me to learn more ?

(Other definitions for jupiter that I've seen before include "Largest planet in our solar system" , "A planet; Trollope's all-powerful newspaper" , "Fifth planet from sun" , "Piece of Holst" , "Heavenly body" .)

Roman Astronomy: History of Science

Without any doubt, Ancient Rome had an immense impact on the world. Although it’s been thousands of years since the Roman Empire flourished, we can still feel its traces in our daily life, art, science, law, architecture, technology, and language. From bridges to names of planets, the Romans left their mark on our world. Although Roman astronomy was not as highly developed as other sciences, and although often wrong with their suggestions, Roman astronomers still left a legacy that matters. Go on reading to learn about some interesting facts about the Ancient Rome astronomy .

Ancient Roman Astronomy: the Highlights

Roman gods and planets.

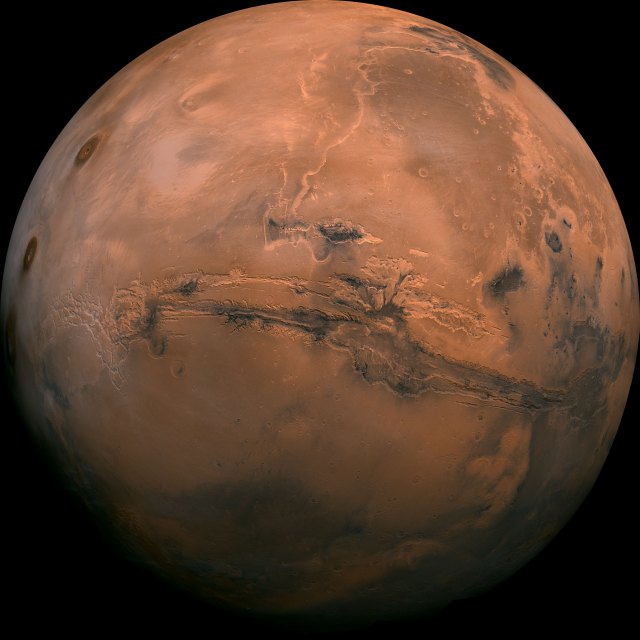

Ancient Romans distinguished seven planets, ordered but Ptolemy in the following way: the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Interestingly, it were the Greeks who first gave names of the Greek gods to planets, but when the Romans studied Greek astronomy, they gave the planets their own gods' names: Mercurius (for Hermes), Venus (Aphrodite), Mars (Ares), Iuppiter (Zeus) and Saturnus (Cronus).

- Mercury was named after Mercurius, one of the major gods in Roman mythology, the god of commerce, eloquence, communication, and travelers. The planet inherited this name because it appears to move fast.

- Venus got its name from the Roman goddess of love because of its bright light and since it’s the most beautiful planet (often perceived as a star) in the night sky.

- Mars was named by the Romans for their god of war because of its red color, associated with blood.

- Jupiter is the largest and most massive of the planets, and that is why it was named after the chief deity, the god of the sky and thunder, and king of the gods in Ancient Roman mythology.

- In Roman mythology, Saturn is the father of Jupiter. Being the seventh planet in Ptolemy’s model, Saturn was actually called after the seventh day of the week Saturday, Sāturni diēs, which means ‘Saturn's Day’.

When other planets were discovered in the 18th and 19th centuries, the naming practice was retained with Neptune, named after the Roman god of the sea. However, Uranus is unique as it was named for a Greek deity, a god personifying the sky.

You might wonder why Earth is the only planet that didn’t get its name from Greco-Roman mythology. The answer is simple: Earth was accepted as a planet much later.

Roman Calendar

The prehistoric Roman calendar is considered to have been an observational lunar calendar whose months began from the first signs of a new crescent moon. Since a lunar cycle is about 29.5 days long, its months would have varied between 29 and 30 days.

The 7th century BC calendar, which is believed to be drawn up by Romulus, one of the founders of Rome, is the ancestor of the calendar most of the world is using today. However, March was the first month of the year, and the year consisted of 10 months, six of 30 days and four of 31 days. But this is just 304 days, you may think. Right you are: the Roman year ended in December and was followed by an uncounted winter gap. Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome, added two months, January and February, and increased the total number of days by 50, making 354, so the calendar was still imperfect. The dates were counted forward to the next of three principal days: the first day of the month (the kalends), a day shortly before the middle of the month (the ides), and eight days before this (the nones). This calendar was based on an observational lunar one. In particular, the kalends, nones, and ides seem to have derived from the first sighting of the crescent moon, the first-quarter moon, and the full moon respectively.

The improved version of the calendar was proposed by Julius Caesar, a Roman statesman, in 46 BC. It counted 12 months, however, at that time each month had the same number of days. Every three (and later every four) years February was given a leap day. This calendar was used until the pope Gregory XIII introduced his calendar in the 16th century, making a couple of changes to the Julian calendar.

Ptolemy's Model of the Solar System

You know that Earth goes around the Sun together with other planets, and you aren’t surprised at the fact that the Sun is actually a star. However, things were pretty different two thousand years ago. Without robust telescopes and accurate equipment, the ancients would see the universe in a different way.

One of the most influential astronomers of his time, Claudius Ptolemaeus, also known as Ptolemy, was born in Egypt in around 90 AD, which was part of the Roman Empire at that time.

Ptolemy’s most significant contribution was a precise representation of the solar system that could predict the position of any of the known planets for any date and time.

In his most famous work called the Almagest, Ptolemy described the motions of the stars and planetary paths. Ptolemy argued that Earth was a sphere in the centre of the universe, based on the straightforward observation that half the stars were above the horizon and half were below the horizon.

According to Ptolemy's model of the solar system, Earth was stationary while the Moon, the Sun, the stars and other planets orbited it. Amazingly, even though Ptolemy’s cosmological model was too far from accurate, with minor adjustments, it endured more than a millenium, until the time of Copernicus who “made” Earth move from the centre.

The publication of Copernicus' model in his book “On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres” is considered to be a major event in the history of science.

- Call Us: +1 (332) 900 6321

Quality & Customer Support

Check our customers Reviews

Follow Us on Social Media

Share your experience Get Discount

Secured & Verified payment

Worldwide shipping

Track Your Order

To Track a Lost Package Contact Us

On the 22nd of July 2022 SIA “OCR” has signed an agreement Nr. SKV-L-2022/322 with Investment and Development Agency of Latvia (LIAA) for the project “International competitiveness promotion”, which is co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

Travel in the Roman World

Dartmouth College

- Published: 07 March 2016

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This article examines Roman travel. It seeks to show how deeply travel was woven into the fabric of the ancient world and how many aspects of the Roman experience relate to it. Rather than pretend to total coverage, this article, which is divided into four sections, offers some ways of thinking about travel and its place in the Roman world, exploring the practice, ideology, and imagination of travel. Moving from a top-down perspective on Roman infrastructure and the role of travel in the practice of Roman power, the article turns to a bottom-up view of the experiences of individuals when traveling, concluding with a survey of the imaginative representation of travel in the literature of the Roman world.

Introduction

I see you know that I arrived in Tusculum on November 14th. Dionysius was there waiting for me. I want to be in Rome on the 18th. I say “want,” but really I have to be there—it’s Milo’s wedding. (Cic. ad Att. 4.13.1 = no. 87 SB; trans. Shackleton Bailey)

So Cicero writes to Atticus in the middle of November 55 BCE, asking for an update on the political situation in the capital. His tongue-in-cheek tone—he has ( cogimur ) to be in town for a wedding—belies both his urgent request for information and the complex network of roads and technologies of travel on which his upcoming trip depends. Neither Cicero’s letter nor his mini-break away from the city are out of place in his correspondence from the mid-50s. On Shackleton Bailey’s dating, twenty-nine letters survive from the years 56 and 55; nearly half were written outside Rome. We learn from those letters that Cicero traveled to Tusculum, Cumae, Napes, Pompeii, and Antium. In other years he ventured even farther afield. When he was reluctantly made governor of Cilicia in 51, he recounted his journey there in a series of plaintive missives to Atticus, griping, for instance, about “waiting for a passage” after being held up for twelve days in Brundisium by an “indisposition” ( ad Att. 5.8.1 = 101 SB; trans. Shackleton Bailey). The only thing worse than waiting for a ship was being a passenger on one; a month later he grumbles from Delos: “Travelling by sea is no light matter, even in July…. You know these Rhodian open ships—nothing makes heavier weather” ( ad Att. 5.12.1 = 105 SB; trans. Shackleton Bailey).

As detailed as Cicero’s correspondence is, it reveals just one individual’s experience of travel in the late Republic. For all the frustrations of his journey to Cilicia or the panic of his flight into exile—narrated in another series of letters from 58 ( ad Att. 3.1–8 = 46–53 SB)—he had much less to complain about than those who died in shipwrecks (e.g., CIL III 1899 = CLE 00826 = ILS 8516 [Blaška Voda; 201–300 CE], CIL XIII 2718 [Autun; second or third century CE]) or in pirate attacks (e.g., AE 1982.512 [La Muela; 71–130 CE]; CIL III 1559 = III 8009 [Slatina; 118–138 CE]). Indeed, Cicero can hardly be said to have lived an average life, even for an elite Roman; nevertheless, his Letters show how deeply travel was woven into the texture of the ancient world and how many aspects of the Roman experience relate to it. Rather than pretend to total coverage of the topic, in this chapter I offer some ways of thinking about travel and its place in the Roman world, exploring the practice, ideology, and imagination of travel from many different directions. Moving from a top-down perspective on Roman infrastructure and the role of travel in the practice of Roman power, I turn to a bottom-up view of the experiences of individuals traveling, concluding with a survey of the imaginative representation of travel in the literature of the Roman world.

Getting Connected: Roman Infrastructure and Roman Connectivity

Cicero might complain about Rhodian ships, but his Letters take for granted the roads, harbors, and organization that make his travels possible. The effect that this infrastructure had on the ability of information, people, and goods to travel through the Roman world might best be described in terms of the concept of “connectivity.” Originating in the fields of graph theory and network analysis, connectivity expresses the relationship between places in terms of the costs and time required to move between them rather than their geographical distance. The wide-spread adoption of the term in the study of the ancient Mediterranean is due in large part to the pioneering work of Horden and Purcell (2000 , 123–72, 562–71; many responses by, e.g., Harris 2005 and Knapp 2008 ; see further Pettegrew 2013 ). Connectivity also informs Walter Scheidel’s and Elijah Meeks’s Stanford ORBIS project ( http://orbis.stanford.edu ), which uses interactive geospatial modeling to plot land, sea, and fluvial routes between major centers in the Mediterranean in terms of the average temporal and monetary costs for each route. By expressing travel as a function of connectivity, the ORBIS model redraws our map of the Roman world and highlights the effects that infrastructure has on shaping its accessibility ( Scheidel 2014 ). Physical infrastructure is just one aspect of a region’s connectivity; in order to be used, it has to be known to and understood by individual travelers. A second aspect of infrastructure is what might be called its “legibility.” This concept, which originates in Urban Studies, applies the metaphor of reading to the experience of navigating a city or, in this case, the world (see, e.g., Lynch 1960 , 2–3). Linking these two approaches to understanding space, I construe connectivity more broadly to include all the intellectual and cultural processes involved in making infrastructure legible and comprehensible to travelers. While such processes of collecting, ordering, mapping, and communicating knowledge to the Roman traveler are harder to capture through mathematical models, such as ORBIS, they are no less important for understanding how the world is connected.

All Roads Lead to Rome, Part I: Physical Infrastructure

Roman connectivity was enabled in the first instance by a highly sophisticated and extensive transport network that consisted of roads as well as maritime and fluvial routes. Roads, which are still visible throughout much of the Roman world, could be traversed on foot; on the backs of horses, donkeys, or camels; and by a variety of vehicles powered by human beings and draught animals ( Chevallier 1976 , 178–81; Bagnall 1985 ; Laurence 1999 , esp. 78–94; Kolb 2000 , 308–32; Adams 2001 ; Matthews 2006 ; Adams 2007 ; Adams 2012 , 229–31; Bekker-Nielsen 2013 ; Owens 2012 ; see also Land Transport, Part 1 and Land Transport, Part 2 ). Built by Appius Claudius Caecus in 312 BCE (cf. CIL XI 1827 = ILS 54 [Arezzo; copy of CIL VI 31606 from the Forum Augusti]) the Via Appia, which Statius called the “queen of long roads” ( Silvae 2.2.11), was the first long-distance link in the Roman transportation network. Due to the Roman practice of extramural burial, the Via Appia, like many roads, was lined with tombs; visitors to Rome, for instance, would be greeted first and foremost by its dead (see Coarelli 2014 , 365–400). As Rome’s power grew, so did its road system; Romans either constructed new roads, as they did in many of the western provinces, or improved upon already existing ones, as in the eastern provinces. Roads’ importance to Roman travel lay in their support of Roman troop movements, in making inland territory easily legible and accessible in the wider network of the Roman state, and in enabling economic activity.

Travel by road was assisted by a secondary infrastructure of private hostels and state-sponsored stopping places to house emperors and Roman officials (Lat. mansio ), which developed during the Roman imperial period, gradually replacing the older practice of requisitioning room and board for official travels ( Casson 1974 , 197–218; Mitchell 1976 ; Millar 1977 , 32–33; Adams 2001 , 142–45). Information, goods, and services could also be transported along Roman roads by the cursus publicus , an express imperial messenger service founded by Augustus ( Ramsay 1925 ; Stoffel 1994 ; Kolb 2000 ). Although there is far less archaeological evidence for roads in Egypt, there too land transport played a central role in the movement of people and goods throughout the province. In addition to archaeologically attested routes that connected the Nile Valley to the Western Desert and the Red Sea coast, Colin Adams collects evidence for a wider network of more temporary roads closer to the Nile, long since destroyed by the river’s annual flooding, which ran from the Mediterranean coast to as far as Syene (Western Desert— Darnell 2002 ; cf. Adams 2007 , 30–33; Western Oases ; Red Sea— Sidebotham and Wendrich 2001–2002 ; Gates 2005 ; Adams 2007 , 33–42; Sidebotham 2011 , 125–74; cf. Strabo 17.1.45; Pliny NH 6.33.165; IGR I 1142 = OGIS 701 = SEG 51 2123 [Antinooupolis, modern Sheikh ‘Ibāda; 137 CE]; The Eastern Desert and the Red Sea Ports ; Nile— Adams 2007 , 22–29; cf. P.Oxy. LX 4087, 4088 [first half of the fourth century CE] on way stations in Tacona and Oxyrhynchus).

Roads were by far the costliest means of transporting goods and traveling; according to calculations made by applying the ORBIS model to data from Diocletian’s Edict on Maximum Prices of 301 CE, transportation by wagon cost between five and fifty-two times more than travel by boat for equivalent distances ( Scheidel 2014 , 9–10). Although the Edict has proven notoriously difficult to interpret, Scheidel’s predictions about the extremely high costs of travel by road are broadly consistent with data from early eighteenth-century England, where transport by land was between five and twenty-three times more expensive than that by boat ( Scheidel 2014 , 9–10). According to these calculations, land transport would have been so costly as to be prohibitively expensive for moving many inexpensive, bulky goods, yet archaeological and documentary evidence attests to roads as an important mode of transport in the Roman world. In response to this apparent paradox, Adams (2001 , 2007 , 2012 ) has suggested that travelers and traders could employ alternative strategies that undercut the prices implied by the Edict . For instance, farmers might transport goods (and people) by using their own animals or rent them out less expensively when they were not needed elsewhere. Even these mitigatory strategies had their limitations, however, and they would not be effective for long-distance travel and transport. For these journeys, boats were an indispensible link.

While roads have left the most enduring mark on the archaeological record, maritime and fluvial routes were equally if not more important for the connectivity of the Roman world. Mariners traversed both short coastal journeys and longer sea lanes ( Arnaud 1992 , 2005 ; Sea Transport, Part 1 ). Sea travel was highly seasonal, and it is therefore likely that temporal and monetary costs varied throughout the year (cf. Casson 1995 ; Veg. Mil. 4.39; Cod. Theod. 13.9.3), but despite the variability in speed, cost, and route, maritime travel was on average the most efficient mode of transportation for goods and people available in antiquity, especially over long distances (as calculated by ORBIS “Sea Transport” according to wind speed; for historically reported sailing times, see Ramsay 1904 , 379; Braudel 1995 , 358–63; Casson 1995 , 282–88; Arnaud 2005 , 102; on the cost of maritime transport, see Arnaud 2007 and Scheidel 2013 , who argue that freight charges in Edict on Maximum Prices correlate closely to average sailing time).

At the interface between land and sea was an extensive network of ports and harbors. Roman quays, which usually reached to the shore, were ordinarily backed by large warehouses, most typically a horrea for grain storage. Their basic form has long been well known from Vitruvius ( De arch. 5.12; cf. Cass. Dio 40.11.1–5), as well as from visual depictions, which are especially well represented at Herculaneum and Pompeii. In addition, Roman harbors are an active area of research; an increasing number of these sites have been excavated thanks to advances in underwater archaeology, which has added substantially to our knowledge about the details of their construction (see further the gazetteer of sites in Sea Transport, Part 2 ).

In addition to sea lanes, many larger rivers were also navigable, but there is no comprehensive treatment of fluvial routes in the Roman world (the best overview is by Campbell 2012 , esp. 200–245). In Egypt, where documentary papyri offer a fuller picture of economic activity, the Nile was a particularly important route ( Adams 2001 ; Cooper 2011 ). Contracts cover every detail of the journey, mandating at which harbors the captain could moor (only the safest), the hours during which he could sail (the proper ones, presumably only during the day), and what to do in case of foul weather (see, e.g., P.Hib. II 198 (third century BCE), with Bagnall 1979 ; P.Ross.Georg. II 18 [140 CE]). These fluvial cargo ships also carried passengers: a letter from 7 BCE, for instance, records one Athenodorus’s efforts to secure passage for his sister (BGU XVI 2604). Even if a captain managed to land in the right harbors, sail at the right time, and avoid foul weather and pirates, travel by river was not always smooth sailing. On the Nile, the swift rapids of the cataracts required particular care and navigational skill. Ships had to be offloaded, and their passengers and cargo were transported overland to the east of the river, while the boat was guided down with cables from the shore (cf. Pomp. 1.9.51; Jaritz and Rodziewicz 1993 ; Between Egypt and Meroitic Nubia: The Southern Frontier Region ). Such challenging waters also invited daredevils. According to several sources, some locals took advantage of the swift currents at the first cataract to put on displays of their water rafting prowess (Strabo 17.1.19; Seneca Nat. 4A2.6–7). Visitors were also known to try their hands at the rapids; the Greek intellectual Aelius Aristides, for instance, proudly claimed to have taken part in such extreme watersports (Aristid. Or. 36.47–51 [Egyptian Discourse]).

Elsewhere in the Roman world, the role of the Tiber in transporting bulk goods to Rome, especially grain, is particularly well attested (cf. Strabo 5.2.5; see further Tuck 2013 , 237–44). After the fire of Rome, Nero used grain ships to transport debris away from the city to the marshes of Ostia (Tac. Ann. 15.43). Bridges built over the river presumably restricted the size of vessels that could reach the capital, but large, wide-bodied ships could still travel upriver to Rome, as depicted in a variety of reliefs, including the so-called Tiber sarcophagus and sections of Trajan’s column ( Tuck 2013 , 238). As a result of all this mercantile activity, the river was often thick with smaller boats (Lat. lintres, lembi, lenuculi , and lusoriae ), which helped to guide larger ships and to ferry goods to shore. This activity was such a central feature of Roman life that it was reflected by Propertius, who used the Tiber’s congestion as a metaphor for his love for Cynthia in his first books of poems (1.14.3-4). A century or so later, Pliny the Elder was more direct, calling the river the “merchant of all things produced in the whole world” ( HN 3.54). Together with the Nile, the Tiber attests to the importance of rivers for transporting goods and people in the Roman world.

All Roads Lead to Rome, Part II: Ordering Geographic Knowledge

In order to be properly used, the physical infrastructure for travel in the Roman world had to be made legible to Roman officials, merchants, and private travelers. In this section I examine some of the means through which this legibility was achieved: namely, labeling roads, collecting route itineraries, describing journeys, and making maps. These processes of ordering, collecting, and presenting information in textual or graphic form were at once functional and ideologically charged. Although this chapter’s focus is on the organization of knowledge related to travel, the intellectual and cultural processes involved can be understood as related to the practices of ordering and presenting other categories of knowledge throughout the Roman empire (see König and Whitmarsh 2007 , esp. 3–39; and König, Oikonomopoulou, and Woolf 2013 on libraries).

Roads were regularly marked with milestones (Lat. miliarium ), which recorded the distance from each terminus and the name of the magistrate or emperor who supervised their construction ( Chevallier 1976 , 39–34; Kolb 2004 ; cf. CIL I 2 21 [Pontinia; 253 BCE]). In this way, roads themselves expressed their place in the wider Roman transportation network. At least some roads also displayed longer and more detailed epigraphic itineraries, such as the fragmentary example from Augustodunum listing routes in northern Italy and southern Gaul ( CIL XIII 2681a, b [= ILS 5838], c = CIL XVII 2 490a–c [before 200 CE]; see also Chevallier 1976 , 52–53, and below). These markers served twin functions, simultaneously orienting travelers and expressing space as Roman; the process of building a road and linking it to the road network of the empire represented a significant centralized intervention in the landscape. The ideological function implicit in all milestones takes precedence in the Miliarium Aureum (Golden Milestone), which Augustus set up in the Roman forum in 20 BCE. By listing the principal cities of the empire and the distances to them as measured from the Severan Wall, the monumental mile marker both established the city as the center of the vast imperial road system and commemorated Augustus’s role in overseeing the Roman transporation network (Pliny HN 3.66; Suet. Otho 6.2; Cass. Dio 54.8.4; LTUR 3 [1996], 250–51; Brodersen 1995 , 254–60). In this sense, the Miliarium Aureum can be seen as an expression of the extent of Roman power and the connection between Roman roads and Roman control. Similarly, the Stadiasmus Provinciae Lyciae , a large monumental pillar from Patara, Lycia, dedicated to the emperor Claudius in 45/46 CE, records distances along Lycian roads ( SEG 44 1205 = SEG 60 1550; first publication: Şahın 1994 ; editio princeps : Işık, İşkan, and Çevik 1998/1999 ). The Stadiasmus , which was originally topped by an architrave and probably an imperial statue, provides a further link between the measurement of the Roman world and ideological expressions of Roman power and administration. Given that the Stadiamus was completed only a few years after the annexation of Lycia in 43 CE, it is likely that it did not reflect Roman improvements to the road network in Lycia, but rather that it reappropriated Lycian roads as Roman ones. Both the Stadiasmus and the Golden Milestone, therefore, serve an ideological function of expressing imperial control through infrastructures of knowledge, even if they only functioned as signposts in “a very extended sense” ( Jones 2001 , 168; see further Lebreton 2010 , esp. 67–76).

In addition to epigraphic routes, ancient geographic knowledge was also expressed through the rich tradition of textual itineraries (see Elter 1908 ; Kubitschek 1916 ; Dilke 1985 , 112–29; Elsner 2001 ; Salway 2001 , 2012 ). These texts make few pretenses to literature—they are usually little more than lists of places and the distances between them, although sometimes they added more colorful material directed at the tourist, pilgrim, or merchant—but they represent one way of making Rome’s network of land and sea routes legible and functional for their readers (thus Veg. Mil. 3.6 recommends using interaria for traveling; see further Adams 2001 ; Brodersen 2001 ). Some, such as the Itinerarium Burdigalense (see Elsner 2001 ), recorded actual routes; others are almost certainly compilations, such as the third-century CE Antonine Itineraries , which begin with the Pillars of Hercules and continue counterclockwise around the Roman empire. The sources from which they were compiled are unknown, but they may derive from epigraphic itineraries, such as the Augustodunum fragment discussed above. As functional as these texts seem, they also express a viewpoint about the world, its connections, and its center(s). In his analysis of the Itinerarium Burdigalense , for instance, Jaś Elsner shows that it was “the first Roman Christian text to present Jerusalem as the centre of the world” (2001, 195). The recognition that itineraries reflect ideologies is particularly significant because of their wide influence on historical and geographic works, such as Strabo’s Geography and Pliny’s Natural History (see Clarke 1999 , 197–210); larger monumental representations of space, such as the so-called Map of Agrippa; and more personal objects, such as the Dura Europos shield, a third-century CE parchment fragment, which graphically represents cities on the coast of the Black Sea and their distances ( Cumont 1925 , 1–15, 1926 , 323–37; Dilke 1985 , 121–23). Itineraries and their ideologies lay at the heart of Roman conceptualizations of their world.

Itineraries are only capable of encoding a single journey at a time. Maps, which graphically represent physical geography and routes in a two-dimensional space, have a greater density of information, and a single map could, in principle, express every possible path through the Roman world. Strict cartographic constructionists, such as Brodersen (1995 , 2001 ), take a consistent concept of scale as a key element of mapping, and they emphasize the differences between modern maps and Greek and Roman representations of geographical space. If we allow for a slightly broader definition of a map, which places more emphasis on perspective than on adherence to a consistent scale, however, it is possible to identify at least two distinct Roman cartographic genres: monumental maps, whose function is closely linked with their context, and smaller maps, usually on papyrus. Like itineraries, even these apparently very functional objects express strong views about the shape of the world and the meaning of travel through it.

Although there is evidence for several monumental maps in the Roman world (see Talbert 2012 ), only two survive, and both are fragmentary: the Forma Urbis Romae , an early third-century CE marble plan of the city of Rome, originally displayed in the Temple of Peace (extant fragments available in an online edition: http://formaurbis.stanford.edu ), and the cadastral plan of Roman centuriation, which was executed in 77 CE in Arausio (modern Orange) under the auspices of Vespasian (edict of Vespasian: AE 1952.44 = AE 1963.197 = AE 1999.1023; see further Piganiol 1962 ; Dilke 1973 ; Jung 2009 ). While the cadastral plan of Arausio imposes Roman order on territory appropriated by the state, it seems unlikely that the Forma Urbis Romae served a similarly practical purpose. In its original context, it was mounted more than four meters above the ground on an interior wall of the Temple of Peace; it would have been impossible for a viewer to get close enough to appreciate its detailed depiction of the layout of the city of Rome ( Trimble 2007 , 369–70). Even though much of it would have been illegible to an ancient viewer, the marble plan served an important ideological purpose by monumentalizing the meticulously ordered cartographic knowledge that it represented (see further Trimble 2007 ). If the connection between cartographic representation and state control is implicit in the Orange Cadasters and the Forma Urbis Romae , both of which depict space from the top-down perspective of Roman power (see further Nicolet 1991 , 95–122; Laurence 1998 ), it appears to have been explicit in another monument to imperial space, which does not survive, Agrippa’s “map” of the world. According to Pliny the Elder, Agrippa commissioned a “representation of the whole world for the city to look upon” ( HN 3.17) in the Porticus Vipsania, which Augustus completed after Agrippa’s death in 12 BCE (Plin. HN 3.17; Cass. Dio 55.8.3–4; Arnaud 2007–2008 ; Talbert 2010 , 136–37, 2012; see further GLM , 1–8 for testimony and LTUR 4 [1999], 151–53 on the Porticus Vipsania). The details of the map remain murky, but it is clear that whether it was a graphical representation of the world or a monumental inscription, like Augustus’s own Res Gestae , it connected the traversibility of the Roman empire with the princeps and his power.

These monumental maps were highly localized and tied to specific archaeological contexts; neither could have aided the traveler on the road. A second genre of maps, which either survive on papyrus or are shaped to resemble a papyrus roll, suggests the possibility of more portable maps that contained detailed route information. Two such maps are extant, although both seem too luxurious to have been used as a road atlas. An incomplete map, produced in the first century BCE or CE, appears on the front of the Artemidorus Papyrus, alongside a geographical text and highly skilled sketches of human faces, feet, and hands (MP 3 168.02; editio princeps : Gallazzi, Kramer, and Settis 2008 ; the reordering of the fragments first proposed by Nisbet 2009 and supported by D’Alessio 2009 , 36–41 has now been accepted by most scholars). A second, the so-called Peutinger Map, a medieval copy of what is likely a fourth-century CE original, survives as eleven parchment segments, which can be joined together to form a long and thin map that closely corresponds to the dimensions of a papyrus roll (cf. Talbert 2010 , 143; average dimensions of papyrus rolls are calculated by Johnson 2004 ). Although the Peutinger’s routes, distances, and place names show a clear dependence on itineraries—in some cases the map retains a place name’s oblique case, as if copying directly from an itinerary—this information was either out of date, inaccurate, or otherwise insufficient to be of practical value to the traveler in the fourth century ( Talbert 2010 , 108–17).

While neither of these maps seems likely to have been used to enable travel, both appear to share a set of cartographic conventions for depicting settlements, waterways, and land routes, and both seem to have distorted their dimensions in order to fit within the constraints of their medium (see Gallazzi, Kramer, and Settis 2008 , 275–308). The maps’ shared representational language suggests that there was a genre of cartography on papyrus that potentially could have extended to portable guides for travelers, even though neither the Artemidorus Papyrus nor the Peutinger Map was likely to have been used for this purpose. What, then, were these two maps used for? It is possible that both of these deluxe maps, like the Forma Urbis Romae , represented space and routes purely for intellectual and/or ideological purposes. For instance, Richard Talbert has persuasively argued that the Peutinger map does much more than represent land routes; in particular, he shows that the outlines of the land were drawn before roads, that Rome is positioned to occupy the map’s center, and that the map uses a variable scale that focuses attention on Italy ( Talbert 2010 , 2012 ). All these details suggest that the map’s composition does more than simply graphically represent information from itineraries. Rather, it reflects Romans’ knowledge about the connectedness of their world and how they imagined the shape of their empire.

Travel and Roman Power

In this section I turn from the physical and intellectual infrastructure of the Roman world to show how travel was integral to the construction, maintenance, and regulation of Roman power in both political and economic terms. Rome sat at the notional and, roughly, the geographic center of an enormous empire, which at its height occupied almost the entirety of the oikoumenē (inhabitable world). In both practical and ideological terms, the physical and intellectual infrastructure I have described in the preceding section defined the extent of the Roman world and enabled Rome to exercise centralized control over it: by transforming the landscape of the Mediterranean, it made even the farthest reaches of the empire accessible to agents of the state, to the army, and to individuals for personal and economic purposes; it marked that landscape as Roman through buildings and inscriptions; and by communicating and disseminating such information, it enabled Romans to make use of this infrastructure to move through their world.

If You Build It, They Will Come: Roman Infrastructure and Roman Military and Economic Power

A high proportion of travel in the Roman world can be attributed to either military or commercial interests; the needs of the Roman army and the desire for economic opportunities contributed to motivating and financing the infrastructure on which other forms of travel depended (see further Roman Army and Roman Economy ). The Roman road system, for instance, was essential to the movements of the army, whose maritime activities appear to have been limited to the transportation of supplies ( Roth 1999 , 189–95; see Bremer 2001 on the use of rivers to supply military camps). It is often argued that roads were constructed primarily to support military activities, and that commercial activities were only an indirect benefit ( Schlippschuh 1974 , 87; Kissel 1995 , 54–77; Roth 1999 , 214–17). While this may be an overstatement, it is clear that the construction of roads contributed to Rome’s economic and military hegemony throughout the Mediterranean in several ways ( Laurence 1999 , 11–26). As Ray Laurence’s analysis of the construction of the Via Appia shows, not only did the road serve a strategic function against the Samnites, but as a large public works project, it employed as laborers Roman citizens and their allies ( Lopes Penga 1950 ; Coarelli 1988 , 42; see Humm 1996 and Laurence 1999 , 15–16, on the construction of the Via Appia).

The same infrastructure that enabled the movement of the Roman army also enabled travel for economic purposes. Literary and documentary sources, especially papyri from Egypt; goods recovered from ancient shipwrecks; and the distribution of finds of specialized products such as Italian wine and snails attest to the quantity and variety of merchandise exchanged throughout the Roman world ( Scheidel 2011a ; Wilson 2011a , 2011b , 2012 , 287–88; see Tchernia 1983 , 1986 ; Panella and Tchernia 1994 on Italian wines; Marzano 2011 discusses the winter snail trade in Roman Egypt; traders themselves often formed associations; see P.Mich. 5 245 [47 CE], CIL III 14165 [Beirut; third century CE], Dig. 50.6.5.3–6, discussed by Meijer and van Nijf 1992 , 75–78). The degree to which trade was central to the Roman economy, however, remains a subject of debate ( Scheidel 2012a , 7–10, offers a concise summary). Economic formalists argue that the Roman Empire was governed by a market-based economy that integrated local economies on an empire-wide scale (argued for in detail by Temin 2013 ; Temin 2012 provides an overview; see Erdkamp 2013 and Manning 2014 for important limitations in our evidence for ancient economic activity). Economic substantivists, on the other hand, focus on the role of the state government in price-setting, requisitioning, and distributing goods; in Keith Hopkins’s “tax and trade model,” governmental and elite demands for taxes and rent drove market forces, creating reciprocal flows of taxable resources (1980 , 1995/1996 , 2009 ; Silver 2008 ). While these models differ in the degree to which the wider Roman market and, therefore, trade and infrastructure were important for influencing local prices and production, both models predict significant amounts of commerce, which would entail corresponding travel by merchants (for examples, see Meijer and van Nijf 1992 ).

Private individuals also traveled for education and employment, as the fourth-century CE curriculum vitae of a certain Conon discovered in modern Ayasofya in Eastern Pamphylia attests: he studied Latin and Roman law in Beirut, got his first job in Palestine, then moved to Antioch and later to Nicomedia; he died while abroad in Egypt, and his father retrieved his body ( SEG 26.1456 = 57.2120; Bean and Mitford 1970 , no. 49; see Gilliam 1974 on the date). Conon spent his life on the move; travel had penetrated the conditions and values by which he lived his life.

Slaves represent a final group of individuals whose travel can be attributed to the exercise of Roman economic and political power. It is a sobering fact that they likely represent the largest group of economic travelers. A central principle of slavery is the abnegation of basic elements of human agency, such as freedom of movement. Because many slaves were captured in war or by pirates, the sale of slaves often involved their transport (on the “Roman slave supply,” see Bradley 1994 , 31–56; Schumacher 2001 , 34–43; Scheidel 2005 , 2011b ; see Matthews 1984 on the importation of slaves to Palmyra). When slaves traveled, it was almost always at the behest of their owners (cf. Bradley 2000 , 118). It is very difficult to estimate the ratio of free persons to slaves in the Roman world, but it is safe to say that at many times and in many places in Rome’s history it was a slave society, and that the slave trade was a significant part of the Roman economy ( for an overview of Roman slavery, see Bradley, Freedom and Slavery; Hopkins 1978 ; Bradley 1994 ; Schumacher 2001 ; Scheidel 2012b ).

Marking Movement: Arrival and Departure Rituals

Travel by officeholders and the emperor himself helped to articulate the contours of Roman power, playing an important role in governing and maintaining a geographically, culturally, and ethnically diverse territory. Because movement by Roman state officials was only experienced by those on the road, profectio (departure) and adventus (arrival) rituals played a central role in making their travel manifest to a wider public. Taken together, these rites constitute a form of Roman spatial religion. Making entrance into and exit from a city at crucially marked moments, they made the populace of each city fellow participants in officials’ movements. Both adventus and profectio rituals were highly choreographed, transactional performances between the governing and the governed. Through ritual practice the conceptual geography of the Roman world was temporarily inverted: the center was invited to imagine travel to the periphery, and the periphery was made into a temporary center. Like many formal characteristics of Roman religious and civic life, rites of arrival and departure had their origins in the Roman republic and were continued in the Roman imperial period, but the use of rituals to demarcate official movement is in fact part of a much wider Mediterranean phenomenon. They were an important feature of Seleucid kingship ( Kosmin 2014 , 142–80) and of their Achaemenid predecessors ( Briant 1988 ; Tuplin 1998 ).