An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Moderation analysis of exchange rate, tourism and economic growth in Asia

Bosede Ngozi Adeleye

1 Dept of Accountancy, Finance and Economics, University of Lincoln, Lincoln, United Kingdom

2 Lincoln International Business School, University of Lincoln, Lincoln, United Kingdom

Jimoh Sina Ogede

3 Dept of Economics, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, Nigeria

Mustafa Raza Rabbani

4 Dept of Accounting and Finance, British University of Bahrain, Sar, Kingdom of Bahrain

Lukman Shehu Adam

5 Dept of Economics and Development Studies, Kwara State University, Malete, Nigeria

Maria Mazhar

6 School of Economics, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan

Associated Data

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

This study brings novelty to the tourism literature by re-examining the role of exchange rate in the tourism-growth nexus. It differs from previous tourism-led growth narrative to probe whether tourism exerts a positive effect on economic growth when the exchange rate is accounted for. Using a moderation modelling framework, instrumental variables general method of moments (IV-GMM) and quantile regression techniques in addition to real per capita GDP, tourism receipts and exchange rate, the study engages data on 44 Asian countries from 2010 to 2019. Results from the IV-GMM show that: (1) tourism exerts a positive effect on growth; (2) exchange rate depreciation hampers growth; (3) the interaction effect is positive but statistically not significant; and (4) results from EAP and SA samples are mixed. For the most part, constructive evidence from the quantile regression techniques reveals that the impact of tourism and exchange is significant at lower quantiles of 0.25 and 0.50 while the interaction effect is negative and statistically significant only for the SA sample. These are new contributions to the literature and policy recommendations are discussed.

1. Introduction

The tourism and hospitality industry has experienced development and expansion making it one of the biggest and fastest-growing sectors [ 1 ]. Many countries and destinations have grown in popularity, resulting in an increase in the number of visitors and tourism receipts. The tourism sector has the potentials to make significant contributions to economic growth and development through a variety of channels. It is a “currency earning sector” that permits the use of human and physical capital stock to drive innovation and development. Simultaneously, the tourism sector is either directly or indirectly related to other sectors like transportation, accommodation, or retailing through trickledown effect [ 2 ]. It also influences spending, and expands trade and global competitiveness [ 3 ]. International tourism, in particular, is a source of foreign exchange generation which improves the balance of payment position [ 4 ] and eases the acquirement of advance technologies and capital goods that can be used in other manufacturing processes [ 5 , 6 ]. Furthermore, it plays an important role in stimulating investments in new infrastructure and enhancing competition thereby creating jobs and improving overall living standard [ 2 ].

Similarly, the exchange rate influences economic growth. In this paper, an improvement/increase in the exchange rate indicates the appreciation of a domestic currency against a foreign currency. It is a significant indicator of economic progress as it essentially mirrors the competitiveness between a domestic economy and the rest of world. The exchange rate reflects a standard exchange among purchasers and merchants of foreign currency in the foreign exchange market of a particular country. Particularly, non-oil trades, oil exporters, international tourist expenditures, and foreign remittances all drive inflow of foreign currency. According to Rapetti et al. [ 7 ] the growth effect of exchange rate specifically the real exchange rate (RER) is both growth-amplifying and growth-dwindling. The exchange rate can significantly affect a country’s balance of payments position particularly if the country’s reliance on imported goods is high. In these circumstances, a more competitive RER would aid in relieving foreign exchange bottlenecks that would otherwise stymie the development process.

The connection between tourism and the exchange rate is not far-fetched. International tourism receipts are significant sources of foreign exchange earnings and highly linked to the exchange rate. Changes in exchange rates greatly affect tourism demand in a destination as changes in the exchange rate will have an impact on the currency value of the country of origin. Any adjustments in the exchange rate will prompt an appreciation or depreciation of the tourist’s currency, affecting transportation costs and the tourist’s decisions to visit the country. Thus, the exchange rate has an impact on the number of tourists’ visits as well as tourism receipts [ 8 ]. Less flexible exchange rates are supposed to advance global exchange and tourism by lessening vulnerability in worldwide transactions, wiping out exchange costs, and expanding market transparency. Furthermore, the exchanges rate mimics the relative price differential (as it affects global economic environment, purchasing power and overall wealth of tourists), which tourists have insufficient information about since they make travel arrangements in their own currency in advance before leaving their country. In this way, low-uncertainty exchange rate regimes could promote international tourism flows [ 9 ] that in turn speed up the development process through foreign direct investment and globalization [ 10 ].

Tourism as a commodity is very susceptible to exchange rate shocks which affects tourists’ inclination to visit a foreign country. We, therefore, hypothesize that changes in the exchange rate will influence the impact of tourism on economic growth. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to empirically test this hypothesis. That is, does the exchange rate tilt the tourism-growth dynamics? To probe the discourse, an unbalanced panel data on 44 Asian economies from 2010 to 2019 comprising tourism receipts, per capita GDP (proxy for economic growth), official exchange rate and a set of control variables is used. To ensure the robustness of the results, a blend of econometrics techniques is deployed. To control for possible endogeneity of the tourism variable, the instrumental variable technique nested within the generalised method of moments (IV-GMM) is used [ 11 – 13 ]. Lastly, the quantile estimator [ 14 – 16 ] is used in the event that the dependent variable has a non-normal distribution. This empirical approach makes the study novel and holistic in ensuring a critical examination of its core arguments. The rest of the paper is structured as follows: section 2 discusses the literature; section 3 outlines the data and empirical model; section 4 discusses the results, and section 5 concludes.

2. Literature review

Tourism activities are considered as one of the most important sources of economic growth and foreign exchange earnings around the globe [ 2 , 6 , 17 ]. The literature on tourism development and its impact on exchange rate and economic growth has increased exponentially in the last three decades [ 18 , 19 ]. The studies on tourism and growth nexus have proliferated mainly due to the fact that international tourism has grown over the years despite some ephemeral shocks [ 20 ]. The tourism growth literature mainly focuses on the causal relationship between tourism and economic growth [ 19 , 21 – 23 ] whereas, tourism and exchange rate literature focus mainly on exchange rate volatility and tourist flows [ 24 – 26 ]. We divide our literature review into two parts; the first part consists of available literature on tourism and economic growth whereas, the second part consists of tourism and exchange rate.

2.1 Tourism and economic growth

This section discusses the literature on tourism economics focusing on economic growth and tourism nexus. From a theoretical perspective, Lanza and Pigliaru [ 27 ] were among the first to document the tourism-growth nexus. They find that countries with high tourism sectors experienced high economic growth. They developed a Lucas type-two sector model where tourism is taken as one of the sectors which depends on the endowments of natural resources such that countries with abundant natural resources have high growth potential and achieve a faster rate of growth. Perles-Ribes et al. [ 28 ] studied the tourism and economic growth nexus using autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) and Toda-Yamamoto model for the period 1957 to 2014 taking into consideration the economic crises. Their findings revealed a bi-directional relationship between economic growth and tourism development. There are many studies proposing the hypothesis that growth of tourism in the country is directly linked to economic prosperity [ 29 ]. The study reports that there is bidirectional causality between tourism and economic growth. Fuinhas et al. [ 22 ] report that in the long run, high frequency of tourist arrivals in the country leads to positive economic growth. In another study, Naseem [ 30 ] concludes that in the long run, tourism receipts, number of tourist arrivals, and total expenditure have a strong positive relationship with economic growth. The study empirically examined the data from Saudi Arabia and validated the popular hypothesis that tourism leads to economic growth in the country. Similar findings were obtained by [ 31 – 35 ], where they concluded that tourism has a positive impact on the economic growth of the country. The study by Sahni et al. [ 36 ] used a quantile regression approach and concluded that tourism growth has a more pronounced effect on economic growth below the threshold and above the threshold. The study further concluded that countries with lower economic growth have more benefits from tourism development. The study by Selvanathan et al. [ 37 ], applied ARDL, vector error correction model (VECM) and panel frameworks and concluded that in the long run tourism development positively contributes to growth. Tourism development is the significant predictor of the economic growth and financial development at frequency rather than the low frequency [ 38 ]. On the contrary, Croes et al. [ 39 ], revealed that tourism development has a very short term effect on economic development and a negative and indirect link to human development. Similar findings were obtained by Kyara et al. [ 23 ] where it was revealed that there is a unidirectional causality relationship between tourism development and economic growth.

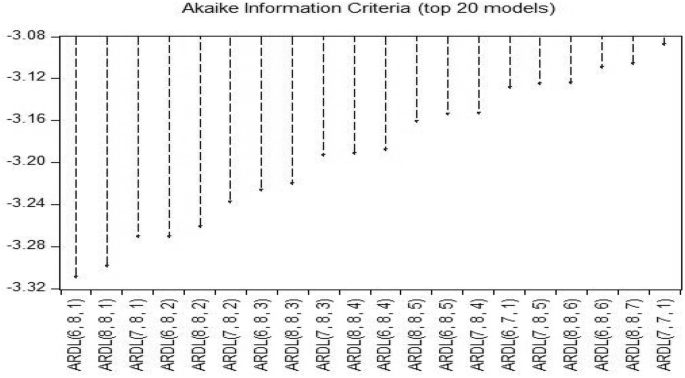

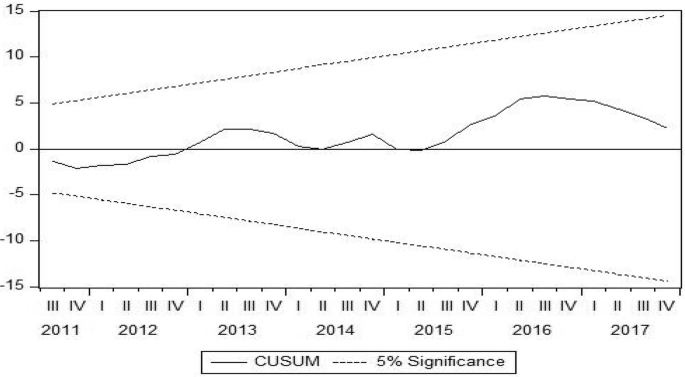

2.2 Tourism and exchange rate

The effects of exchange rate on tourism development can differ across the country, territory and within the tourism jurisdiction [ 38 ]. The real and nominal appreciation of the currency leads to a negative impact on the tourism development in the country [ 40 ]. Exchange rate has asymmetric impact on tourism on tourism development in developing countries such as, India, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Nepal in the short run [ 41 ]. Boskurt et al. [ 42 ] applied dynamic common correlated effects (DCCE) approach in their study on demand and exchange rate shocks on tourism development and concluded that effects of the exchange rate shocks are temporary on the tourism development. To examine the response of tourism demand to exchange rate fluctuation in South Korea, Chi [ 43 ] used ARDL model and concluded that tourists are sensitive to the appreciation of the Korean Won, whereas they are insensitive to its depreciation. The findings of the study imply that foreign visitors in Korea are loss averse and with increase or decrease in the exchange rate volatility tend to affect the tourism demand in an asymmetric manner. Dogru et al. [ 44 ] used ARDL approach to examine the trade balance and exchange rate taking evidence from tourism development. The study concluded that depreciation and appreciation of the US Dollar affects the bilateral tourism with Canada, Mexico, and the United Kingdom (UK). The study further concluded that in the long-run the appreciation of the US dollar negatively affects the tourism trade balance with Canada and the UK while it does not affect the tourism development with Mexico in the long-run. A study by Belloumi [ 45 ], examined tourism receipts and exchange rate nexus in Tunisia and concluded that there is a cointegrating relationship between tourism and economic growth. An increase in foreign direct investment (FDI) and appreciation of the exchange rate contracts the tourism demand of the country while in the long-run the depreciation of domestic currency and decrease in FDI inflow results in more tourist inflow [ 41 ]. Similar findings were obtained by [ 46 ] and [ 47 ] where they revealed that reduction in FDI inflow and depreciation of foreign exchange rate results in positive tourism development.

2.3 Tourism, exchange rate and economic growth

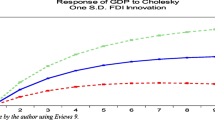

There are few studies that investigated the nexus of exchange rate, tourism development and economic growth [ 23 , 48 , 49 ]. Primayesa et al. [ 50 ] probed the dynamic relationship among real exchange rate, economic growth and tourism development in Indonesia using variance decomposition and impulse response function approach. The study revealed that in explaining the tourism shock in Indonesia, the real exchange rate is less important than the economic growth. The study further concluded that the shock of economic growth and real exchange rate has a positive effect on tourism activity in the short- and long-term. Harvey et al. [ 25 ] applied bounds testing approach to cointegration and error-correction modelling to examine whether tourism development and exchange rate promote the economic growth in Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines. The study revealed the Philippines is the only country that has the positive long-run and short-run impact from the tourism industry and exchange rate.

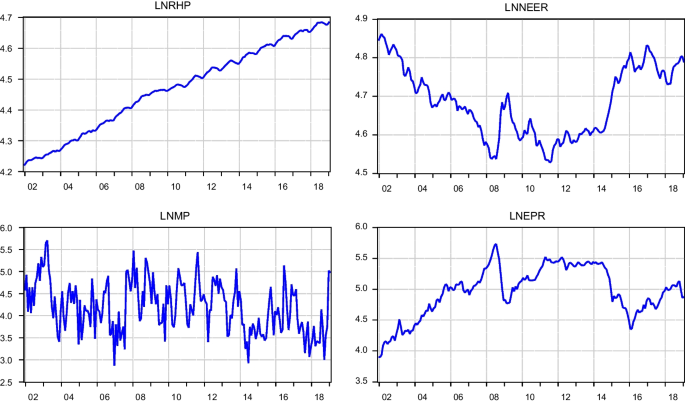

3. Data and methodology

This study uses data on nine variables sourced from World Development Indicators (WDI) for 44 countries located in East Asia and the Pacific (EAP) and South Asia (SA) from 2010 to 2019. Availability of sufficient data on the variables of interest–per capita GDP, tourism receipts, and official exchange rate—justify the inclusion of a country in the sample and to explore the heterogeneity of the sample countries, we disaggregate the full sample into EAP with 36 countries and SA having 8 countries. The countries are East Asia and the Pacific (36): American Samoa, Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, China, Fiji, French Polynesia, Guam, Hong Kong SAR, China, Indonesia, Japan, Kiribati, Korea, Dem. People’s Rep., Korea, Rep., Lao PDR, Macao SAR, China, Malaysia, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Fed. States, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nauru, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Samoa, Singapore, Solomon Islands, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Tonga, Vanuatu, Vietnam. South Asia (8): Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka.

3.1 Dependent variable

Real GDP per capita is the proxy for economic growth. Studies on tourism-growth nexus have widely used it [ 51 – 53 ] likewise, those on exchange rate-growth relationship [ 54 , 55 ].

3.2 Main explanatory variables

From World Development Indicators, International tourism, receipts (% of total exports) is defined as: expenditures by inbound visitors including payments to foreign carriers for international transport. In other words, this composite variable captures the spendings of inbound tourists to Asia and the Pacific, among others. In line with the literature [ 56 – 60 ], tourism receipts which is the first main explanatory variable is proxied by tourism receipts in current US dollars. Existing literature have found a positive relationship between different dimensions of tourism and economic growth [ 61 – 65 ]. The second key explanatory variable is exchange rate [ 42 , 66 – 68 ]. The exchange rate captures the competitiveness of a country in the international market [ 69 – 73 ]. Lastly, to address the study questions, an interaction term of tourism receipts with exchange rate (TRPT*XR) is included to determine if exchange rate moderates the impact of tourism on growth.

3.3 Control variables

The set of control variables align with those used in growth models: mobile phone subscription [ 5 , 74 , 75 ], individuals using the Internet [ 76 , 77 ], labour force participation [ 78 ] (Niebel, 2018), foreign direct investment net inflows [ 79 ], domestic credit to the private sector [ 80 – 83 ] and services trade [ 84 , 85 ]. We expect positive coefficients in line with existing literature. Table 1 details the variables used.

Source: Authors’ Compilation from World Bank [ 86 ] World Development Indicators (WDI)

3.4 Empirical model

We specify two baseline linear models that expresses economic growth as a function of tourism receipts, exchange rate and a set of control variables which satisfies the first objective:

Where, ln PC it = natural logarithm of per capita GDP; ln TRPT it = natural logarithm of tourism receipts; XR it = official exchange rate; Z ′ it and K ′ it = vector of control variables in natural logarithms; α i , γ i = parameters to be estimated; φ t , δ t = year dummies (which controls for common shocks such as the global financial crises of 2007–2009), and u it , e it = general error term. To satisfy the second objective, we add an interaction term ( TRPT*XR ) to Eq [ 1 ] and the model becomes:

Where, R ′ it = vector of control variables in natural logarithms; η i = parameters to be estimated; ω t = year dummies (which controls for common shocks such as the global financial crises of 2007–2009), and v it = general error term. From Eq [ 3 ], η 3 provides two information. First, the sign of the coefficient indicates if exchange rate exerts a significant moderation effect on economic growth. That is, whether the interaction of both variables intensifies or hinders growth. Secondly, the magnitude of the coefficient may sustain or sway the impact of tourism on growth which is derived as:

3.5 Estimation techniques and strategy

Specifically, our econometric strategy consists of a three-step procedure. First, we examine linear impact of tourism on economic growth. Next, we estimate the linear effect of exchange rate on economic growth. Lastly, we perform the moderation analysis to show the interaction effect on economic growth. We engage these analyses using two techniques: the instrumental variables-two-step generalised method of moments (IV-GMM) techniques and the quantile estimator [ 14 – 16 ]. Specifically, the IV-GMM technique is used to correct for cross-sectional dependence, endogeneity, autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity in the data [ 11 , 87 ]. It uniquely deploys the ivreg2 routine in Stata version 16 developed by Baum, Schaffer, and Stillman [ 12 , 13 ]. The routine performs several variants of single-equation linear regression models including the generalized method of moments (GMM). Hence, the GMM variant which implements the two-step feasible GMM estimation (that is, gmm2s option) is adopted to ensure that our results are devoid of endogeneity, heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation [ 12 ]. On the other hand, the quantile regression is deployed to examine the potentially differential effects of tourism and exchange rate at different levels of growth. The quantile regression model is a defined solution to minimize the equation for the θ th regression quantile, 0< θ <1 and expressed thus:

Where, y t is the dependent variable and x t is a k x 1 vector of explanatory variables.

4. Results and discussions

4.1 summary statistics and correlation analysis.

The upper panel of Table 2 contains the correlation matrix’s results, illustrating the relationship between the regressors and the outcome variables. Our findings indicate a negative correlation between per capita GDP and official exchange rate, implying that rising income will decrease the exchange rates in Asia. Likewise, individuals use the internet and the official exchange rate. Trade in services is negatively associated with tourism receipts, official exchange rate, FDI, and MOB. These findings suggest that increasing individuals using the internet and trade in services will impact the official exchange rate, tourism receipts, FDI, and MOB.

*** p<0.01

** p<0.05

* p<0.1

ln = Natural logarithm; PC = per capita GDP; TRPT = tourism receipts; XR = Official exchange rate; DC = Domestic credit to the private sector; LAB = labour force participation rate; FDI = foreign direct investment; MOB = mobile phone subscriptions; NET = individuals using the Internet; TRS = trade in services; 9.08E+09 = 9,080,000,000.00

Source: Authors’ Computations

The lower panel of Table 2 indicates the summary statistics for the variables from 2010 to 2019. The average of per capita GDP, tourism receipts, official exchange rate, domestic credit to the private sector, labour force participation, foreign direct investment, mobile phone subscriptions, internet users, and trade in services are 12398.47, 9080000, 1295.02, 71.42, 69.06, 1540000, 92490468, 38.86, and 30.269, respectively, from the entire sample. At the same time, the standard deviation provides information on the deviation from sample averages.

4.2 IV-GMM results

Table 3 displays results for the instrumental variables-two-step generalised method of moments (IV-GMM). Across the Full, EAP, and SA samples, tourism receipts and exchange rate are instrumented with their first difference and level terms. Limiting to the variables of interest, the summary of the linear models from the full sample shows tourism receipts as a significant positive predictor of economic growth. The findings indicate that a percentage change leads to 0.88% rise in economic growth, on average, ceteris paribus . We argue that a well-structured tourist sector together with investments in modern infrastructure will boost growth supporting Tugcu [ 88 ], Alfaro [ 89 ], Calero and Turner [ 90 ], Cheng and Zhang [ 91 ], and Scarlett [ 92 ] all of which argue in favour of tourism-driven growth. The exchange rate shows a significant negative effect on growth. According to the findings, a percentage-point change in the exchange rate results in a 0.00005% drop in economic growth. The reason for this is not far-fetched. Exchange rate fluctuations influence potential travellers’ decisions to alter their destination or shorten their vacation resulting in revenue loss for economies. This may result in adjustments to visitors’ travel plans while in a particular nation [ 93 ]. These findings corroborate those of Lin, Liu, and Song [ 94 ], Meo et al. [ 95 ], Sharma and Pal [ 96 ], Chi [ 43 ], and Seraj and Coskuner [ 97 ]. For EAP countries, tourism increases economic growth by 0.62%, on average, ceteris paribus . On the other hand, the coefficient of the exchange rate is negative and significant at 1 per cent, which supports the argument of Vieira et al. [ 98 ] and Seraj and Coskuner [ 97 ]. These studies contend that local currency appreciation will decrease the spending power of international tourists with consequent decline on tourism demand and economic growth. In South Asia, the effect of tourism on growth is positive but statistically not significant but exchange rate significantly boosts growth by 0.007%, on average, ceteris paribus . This finding contradicts Seraj and Coskuner [ 97 ] and suggests that currency appreciation is growth-enhancing. For the moderation models, columns [ 3 , 6 , 9 ] reveal that the interaction effect is positive but statistically not different from zero for the full and EAP samples while it decreases growth in South Asia which contradicts Sharma, Vashishat, and Rishad [ 99 ]. In other words, the conditional effect of tourism on growth reduces when exchange rate appreciates in South Asia.

t -statistics in (); -5.40e-05 = 0.0000540; ln = Natural logarithm; PC = real per capita GDP; TRPT = tourism receipts; XR = Official exchange rate; DC = Domestic credit to the private sector; LAB = labour force participation rate; FDI = foreign direct investment; MOB = mobile phone subscriptions; NET = individuals using the Internet; TRS = trade in services.

On the reliability of the instruments used to validate the robustness of our estimations, we controlled for identification and exclusion restrictions which are indispensable for robust GMM estimations [ 12 , 13 ]. Having used the IV-GMM estimation in ivreg2 , the appropriate test of overidentifying restrictions and testing the validity of instruments used is the Hansen J statistic: the GMM criterion function. From the lower panel of Table 3 , the p -value of the Hansen-J statistic across the six models ranges between 0.085 and 0.3874 which is clearly above 0.05. Hence, it fails to reject the null hypothesis of instruments validity indicating that the instruments used are valid and robust to our analysis.

4.3 Quantile regression results

Table 4 presents the quantile regression results across the 25th, 50th, and 75th quantiles of economic growth. The topmost panel displays the full sample results where tourism significantly improves growth at the 25 th and 50 th quantiles by 0.23% and 0.12%, respectively. Noticeably, the positive effect of tourism receipts declines along the distribution. On the other hand, exchange rate appreciation shows a reducing effect on growth at the 25 th and 50 th quantiles by -0.000051% and -0.000059%, respectively. This reducing effect is larger at the 50 th quantile indicating that economic growth vulnerable to exchange rate fluctuations. Following our findings, we hypothesise that variations in the official exchange rate affects tourist purchasing decisions and economic growth in the long-run [ 100 ]. On the interaction effect, we find no significant impact on growth corroborating the results shown in Table 3 .

I-statistics in (); ln = Natural logarithm; PC = per capita GDP; TRPT = tourism receipts; XR = Official exchange rate; DC = Domestic credit to the private sector; LAB = labour force participation rate; FDI = foreign direct investment; MOB = mobile phone subscriptions; NET = individuals using the Internet; TRS = trade in services.

The results of East Asia and the Pacific displayed in the middle panel indicate that tourism significantly increases growth at the 25 th and 50 th quantiles by 0.44% and 0.31%, respectively. A reducing positive effect is observed similar to that of the full sample. Also, exchange rate appreciation shows a reducing effect on growth at the 25 th and 50 th quantiles by -0.000061% and -0.000067%, respectively. Similar to the full sample, this reducing effect is larger at the 50 th quantile and we find no significant interaction effect on growth. From the lowest panel, the results from South Asia indicate that tourism significantly increases growth at the 50 th and 7 th quantiles by 0.17% and 0.19%, respectively. An increasing positive effect is observed contrary to the full and EAP samples. Likewise, exchange rate appreciation increases economic growth across all the quantiles, though with a declining trend from 0.0087% to 0.0075%. Contrary to the full and EAP samples, a significant negative interaction effect is observed across the quantiles supporting the results shown in Table 3 .

5. Conclusion and policy recommendation

This current study highlights the role of exchange rate in influencing the effect of tourism on economic growth in Asia. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that critically evaluates the influence of exchange rate on the tourism-growth nexus. That is, it gauges the nonlinear effect of tourism on economic growth when the exchange rate is accounted for. This position differs from other tourism-growth studies [ 22 , 27 – 30 , 101 , 102 ] that investigated the direct and linear effect of tourism on economic growth but aligns with Adeleye et al. [ 103 ] who examined a similar nexus on Sri Lanka. For the most part, these studies affirm that tourism exerts a direct and positive effect on economic growth. However, we expand the frontiers of knowledge having recognized that the exchange rate is an important macroeconomic policy instruments for promoting sustainable economic growth and encouraging tourism flows as it serves as an essential factor influencing the decision of tourists regarding tourism destinations. To this end, this paper examines the moderating effect of exchange rate and tourism receipts on economic growth in Asia from 2010 to 2019. From the full sample, findings from IV-GMM and quantile regressions techniques revealed that tourism significantly boosts economic growth, and the exchange rate indicates a negative effect. Deductively, we conclude that tourism is growth-enhancing which supports the tourism-led growth conjecture and that exchange rate appreciation is also growth-reducing. On the interaction effect, though the coefficient is positive but statistically insignificant it suggests that currency appreciation may possess inherent potentials in sustaining the positive effect of tourism on economic growth. Results from the East Asia and the Pacific and South Asia are diverse.

Based on the findings, the following recommendations are made for the government and stakeholders in Asia: (1) Provide a sound and efficient financial system which does not only provide adequate funding for promoting the tourism sector but also ensure easy accessibility to aid foreign tourist’s transaction. (2) Initiate investment incentive policies for the tourism sector which will reduce the operating cost, investment outlay and provide security for the investment of tourist investors. (3) Initiate a well-managed exchange rate system that supports tourism flows and economic growth. For further studies and subject to data availability, the role of government regulation, real exchange rate and competitiveness in relation to the tourism-growth dynamics may be undertaken.

Supporting information

Funding statement.

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Data Availability

- PLoS One. 2022; 17(12): e0279937.

Decision Letter 0

30 Aug 2022

PONE-D-22-18174Moderation analysis of exchange rate, tourism and economic growth in AsiaPLOS ONE

Dear Dr. Adeleye,

Thank you for submitting your manuscript to PLOS ONE. After careful consideration, we feel that it has merit but does not fully meet PLOS ONE’s publication criteria as it currently stands.

In view of the referees’ feedback and my own reading of your paper, we believe your paper is some way from being publishable. In particular, there are serious doubts about the underlying hypotheses on which the research is based, as well as about the methodology used.

While we consider the issues identified to be major in nature, we are willing to offer you a chance to rework the paper if you feel able to address them fully and robustly. Therefore, we invite you to submit a revised version of the manuscript that addresses the points raised during the review process.

Please submit your revised manuscript by Oct 14 2022 11:59PM. If you will need more time than this to complete your revisions, please reply to this message or contact the journal office at gro.solp@enosolp . When you're ready to submit your revision, log on to https://www.editorialmanager.com/pone/ and select the 'Submissions Needing Revision' folder to locate your manuscript file.

Please include the following items when submitting your revised manuscript:

- A rebuttal letter that responds to each point raised by the academic editor and reviewer(s). You should upload this letter as a separate file labeled 'Response to Reviewers'.

- A marked-up copy of your manuscript that highlights changes made to the original version. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Revised Manuscript with Track Changes'.

- An unmarked version of your revised paper without tracked changes. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Manuscript'.

If you would like to make changes to your financial disclosure, please include your updated statement in your cover letter. Guidelines for resubmitting your figure files are available below the reviewer comments at the end of this letter.

If applicable, we recommend that you deposit your laboratory protocols in protocols.io to enhance the reproducibility of your results. Protocols.io assigns your protocol its own identifier (DOI) so that it can be cited independently in the future. For instructions see: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/submission-guidelines#loc-laboratory-protocols . Additionally, PLOS ONE offers an option for publishing peer-reviewed Lab Protocol articles, which describe protocols hosted on protocols.io. Read more information on sharing protocols at https://plos.org/protocols?utm_medium=editorial-email&utm_source=authorletters&utm_campaign=protocols .

We look forward to receiving your revised manuscript.

Kind regards,

J E. Trinidad Segovia

Section Editor

Journal Requirements:

When submitting your revision, we need you to address these additional requirements.

1. Please ensure that your manuscript meets PLOS ONE's style requirements, including those for file naming. The PLOS ONE style templates can be found at

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/file?id=wjVg/PLOSOne_formatting_sample_main_body.pdf and

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/file?id=ba62/PLOSOne_formatting_sample_title_authors_affiliations.pdf

2. Please include captions for your Supporting Information files at the end of your manuscript, and update any in-text citations to match accordingly. Please see our Supporting Information guidelines for more information: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/supporting-information .

[Note: HTML markup is below. Please do not edit.]

Reviewers' comments:

Reviewer's Responses to Questions

Comments to the Author

1. Is the manuscript technically sound, and do the data support the conclusions?

The manuscript must describe a technically sound piece of scientific research with data that supports the conclusions. Experiments must have been conducted rigorously, with appropriate controls, replication, and sample sizes. The conclusions must be drawn appropriately based on the data presented.

Reviewer #1: Yes

Reviewer #2: Yes

Reviewer #3: Partly

2. Has the statistical analysis been performed appropriately and rigorously?

Reviewer #2: N/A

Reviewer #3: I Don't Know

3. Have the authors made all data underlying the findings in their manuscript fully available?

The PLOS Data policy requires authors to make all data underlying the findings described in their manuscript fully available without restriction, with rare exception (please refer to the Data Availability Statement in the manuscript PDF file). The data should be provided as part of the manuscript or its supporting information, or deposited to a public repository. For example, in addition to summary statistics, the data points behind means, medians and variance measures should be available. If there are restrictions on publicly sharing data—e.g. participant privacy or use of data from a third party—those must be specified.

Reviewer #3: No

4. Is the manuscript presented in an intelligible fashion and written in standard English?

PLOS ONE does not copyedit accepted manuscripts, so the language in submitted articles must be clear, correct, and unambiguous. Any typographical or grammatical errors should be corrected at revision, so please note any specific errors here.

Reviewer #1: No

Reviewer #3: Yes

5. Review Comments to the Author

Please use the space provided to explain your answers to the questions above. You may also include additional comments for the author, including concerns about dual publication, research ethics, or publication ethics. (Please upload your review as an attachment if it exceeds 20,000 characters)

Reviewer #1: Idea of the paper and statistical parts have been performed appropriately and rigorously. And there is no problem. But some formal parts have mistakes and errors. Some of them:

1- Abstract part should be improved.

2- Too many references. Can be reduced according to the journal index (Scopus, Sci, ssci etc.)

3- No need to citations in Data and Methodology parts. They must be in Literature Review part.

4- In text there are citation errors. For example more than 3 authors use et al. Some parts it is true but some parts wrong.

5- Some citations are missed in references especially in page 12.

6- Use "literature review" instead of "Review of literature".

7- At conclusion part comparisons with previous studies can be made.

Reviewer #2: The paper attempts to examine “moderation analysis of exchange rate, tourism and economic growth in Asia”. After reviewing, I find that this paper is interesting. The paper is readable ragarding the case of economic growth in Asian in the background of exchange rate, tourism and their interactive association.

See the attachment

Reviewer #3: The paper under consideration looks at the impact of tourism on GDP growth and the interactions of the impact with exchange rate. In my opinion this paper has important shortcomings that will prevent it from being published in the current form. My suggestion is rejection. The issues that lead to my decision are as follows:

1. The paper largely ignores the growth regression literature and certainly aims to be a part of it.

2. The value added generated in the tourism sector is in fact part of the overall value added of the economy. This is largely correlated with the international tourism. What sense does it have to regress GDP on a component of it? We can find out quite precisely what is the EXACT contribution of tourism to GDP and GDP growth.

3. The models are estimated by GMM. However, what are the instruments? The paper does not seems to use any sort of Arellano-Bond, Arellano Bower System-GMM. So the description is vague. And in particular, the panel System-GMM methods are mainly used to solve the endogeneity caused by the lagged dependent variable and not the inherent endogeneity of the economic problem posed here. So this part clearly needs clarification and justification. It does not suffice to write that „results are devoid of endogeneity, heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation.”

4. The measurement of both TRPT and GDP in USD should be discussed, i.e., the volume of tourist services may be positively related to depreciating exchange rate but its value in USD may not.

5. To what extend this is a different problem than analysis of any export-oriented sector? Why do we care?

6. How about controlling for real exchange rate, standard in BOP and competitiveness-related studies.

6. PLOS authors have the option to publish the peer review history of their article ( what does this mean? ). If published, this will include your full peer review and any attached files.

If you choose “no”, your identity will remain anonymous but your review may still be made public.

Do you want your identity to be public for this peer review? For information about this choice, including consent withdrawal, please see our Privacy Policy .

Reviewer #1: Yes: Volkan Dayan

Reviewer #2: No

[NOTE: If reviewer comments were submitted as an attachment file, they will be attached to this email and accessible via the submission site. Please log into your account, locate the manuscript record, and check for the action link "View Attachments". If this link does not appear, there are no attachment files.]

While revising your submission, please upload your figure files to the Preflight Analysis and Conversion Engine (PACE) digital diagnostic tool, https://pacev2.apexcovantage.com/ . PACE helps ensure that figures meet PLOS requirements. To use PACE, you must first register as a user. Registration is free. Then, login and navigate to the UPLOAD tab, where you will find detailed instructions on how to use the tool. If you encounter any issues or have any questions when using PACE, please email PLOS at gro.solp@serugif . Please note that Supporting Information files do not need this step.

Submitted filename: review.docx

Author response to Decision Letter 0

Dear Editor,

I have uploaded a Word file containing point-by-point responses to the Reviewers' comments.

Dr. Ngozi Adeleye

Submitted filename: Responses to Reviewers Comments_ExR-Tour-EG, Asia.docx

Decision Letter 1

14 Nov 2022

PONE-D-22-18174R1Moderation analysis of exchange rate, tourism and economic growth in AsiaPLOS ONE

Thank you for submitting your manuscript to PLOS ONE. After careful consideration, we feel that it has merit but does not fully meet PLOS ONE’s publication criteria as it currently stands. One of the reviewers consider that his/her comments have not been properly addressed. Please revise the previous comments and answer to the reviewer. Please submit your revised manuscript by Dec 29 2022 11:59PM. If you will need more time than this to complete your revisions, please reply to this message or contact the journal office at gro.solp@enosolp . When you're ready to submit your revision, log on to https://www.editorialmanager.com/pone/ and select the 'Submissions Needing Revision' folder to locate your manuscript file.

1. If the authors have adequately addressed your comments raised in a previous round of review and you feel that this manuscript is now acceptable for publication, you may indicate that here to bypass the “Comments to the Author” section, enter your conflict of interest statement in the “Confidential to Editor” section, and submit your "Accept" recommendation.

Reviewer #1: All comments have been addressed

Reviewer #2: (No Response)

Reviewer #3: (No Response)

2. Is the manuscript technically sound, and do the data support the conclusions?

3. Has the statistical analysis been performed appropriately and rigorously?

4. Have the authors made all data underlying the findings in their manuscript fully available?

5. Is the manuscript presented in an intelligible fashion and written in standard English?

6. Review Comments to the Author

Reviewer #1: This study brings novelty to the tourism literature by re-examining the role of exchange rate in the tourism-growth nexus. It differs from previous tourism-led growth narrative to probe whether tourism exerts a positive effect on economic growth when the exchange rate is accounted for. All corrections are enough for publishing.

Reviewer #2: Dear Authors,

I feel satisfied with this version and your replies on my comments. Therefore, I have decided the acceptance for this paper.

Reviewer #3: I do not believe that the authors have taken my comments seriously. It is not enough to say: "we are using GMM" because it is a large class of models. What are the instruments? What are the moment conditions? Authors say they do not use GMM based on lagged values (Arellano Bond, Arellano Bover) but another approach. So what exactly is it?

7. PLOS authors have the option to publish the peer review history of their article ( what does this mean? ). If published, this will include your full peer review and any attached files.

Author response to Decision Letter 1

15 Nov 2022

Uploaded a Word file containing the response to Reviewer's comments.

Dr. Ngozi ADELEYE

Submitted filename: 2nd_Responses to Reviewers Comments_ExR-Tour-EG, Asia.docx

Decision Letter 2

24 Nov 2022

PONE-D-22-18174R2Moderation analysis of exchange rate, tourism and economic growth in AsiaPLOS ONE

Dear Dr. ADELEYE,

Thank you for submitting your manuscript to PLOS ONE. After careful consideration, we feel that it has merit but does not fully meet PLOS ONE’s publication criteria as it currently stands.

I have to congratulate the authors for their efforts and the reviewers for their valuable comments. This latest version clearly shows a very substantial improvement on the manuscript.

However, there is still a minor issue to be resolved. In particular, the reviewer is asking for some probes on the robustness of the results.

Therefore, we invite you to submit a revised version of the manuscript that addresses the points raised during the review process. Please submit your revised manuscript by Jan 08 2023 11:59PM. If you will need more time than this to complete your revisions, please reply to this message or contact the journal office at gro.solp@enosolp . When you're ready to submit your revision, log on to https://www.editorialmanager.com/pone/ and select the 'Submissions Needing Revision' folder to locate your manuscript file.

Please review your reference list to ensure that it is complete and correct. If you have cited papers that have been retracted, please include the rationale for doing so in the manuscript text, or remove these references and replace them with relevant current references. Any changes to the reference list should be mentioned in the rebuttal letter that accompanies your revised manuscript. If you need to cite a retracted article, indicate the article’s retracted status in the References list and also include a citation and full reference for the retraction notice.

Reviewer #3: All comments have been addressed

Reviewer #3: Now with the paper specifying the actual method and the choice of instruments, the only thing that is lacking is providing test statistics to check for the validity of instruments, i.e., the J statistic or equivalent and the discussion on the validity of instruments. The authors seem to treat the IV-GMM technique as a solution to several econometric problems but they do not check whether the problems have been indeed solved.

Author response to Decision Letter 2

28 Nov 2022

I have uploaded a Word file containing responses to the comments of the Reviewer.

Submitted filename: 3rd_Responses to Reviewers Comments_ExR-Tour-EG, Asia.docx

Decision Letter 3

19 Dec 2022

PONE-D-22-18174R3

We’re pleased to inform you that your manuscript has been judged scientifically suitable for publication and will be formally accepted for publication once it meets all outstanding technical requirements.

Within one week, you’ll receive an e-mail detailing the required amendments. When these have been addressed, you’ll receive a formal acceptance letter and your manuscript will be scheduled for publication.

An invoice for payment will follow shortly after the formal acceptance. To ensure an efficient process, please log into Editorial Manager at http://www.editorialmanager.com/pone/ , click the 'Update My Information' link at the top of the page, and double check that your user information is up-to-date. If you have any billing related questions, please contact our Author Billing department directly at gro.solp@gnillibrohtua .

If your institution or institutions have a press office, please notify them about your upcoming paper to help maximize its impact. If they’ll be preparing press materials, please inform our press team as soon as possible -- no later than 48 hours after receiving the formal acceptance. Your manuscript will remain under strict press embargo until 2 pm Eastern Time on the date of publication. For more information, please contact gro.solp@sserpeno .

Additional Editor Comments (optional):

Reviewer #3: After the latest additions, I recommend the paper for publication. It seems that instruments pass the required tests.

Acceptance letter

21 Dec 2022

Dear Dr. ADELEYE:

I'm pleased to inform you that your manuscript has been deemed suitable for publication in PLOS ONE. Congratulations! Your manuscript is now with our production department.

If your institution or institutions have a press office, please let them know about your upcoming paper now to help maximize its impact. If they'll be preparing press materials, please inform our press team within the next 48 hours. Your manuscript will remain under strict press embargo until 2 pm Eastern Time on the date of publication. For more information please contact gro.solp@sserpeno .

If we can help with anything else, please email us at gro.solp@enosolp .

Thank you for submitting your work to PLOS ONE and supporting open access.

PLOS ONE Editorial Office Staff

on behalf of

Dr. J E. Trinidad Segovia

- Hospitality Industry

Exchange Rate trends, how do they impact hotel performance?

November 12, 2020 •

5 min reading

In this report we analyze how exchange rate fluctuations affect the hospitality industry. We consider the case of Switzerland, which is a small open economy located in the heart of the European monetary union.

Switzerland is a very special country because, thanks to its stability, it has always been considered a safe haven where international investors put their resources when there is economic turmoil and uncertainty in the rest of the world. The combination of these two features - a high degree of openness and a currency which has a tendency to appreciate - makes Switzerland a very interesting case study. Why? Because a strong currency reduces the ability of Switzerland to trade.

DOWNLOAD THE EXCHANGE RATE TRENDS REPORT NOW

In general, exchange rate fluctuations affect any generic sector exposed to trade with foreign countries, as follows:

In particular, Hospitality and Tourism industries fall into the category of export-oriented sectors because they export services. When we export goods, we physically move a good from the country where it has been produced to a foreign country where it is going to be consumed. In the case of services, instead, we export a service whenever the consumer (resident in a foreign country, the tourist) physically goes to the country of the producer, where he/she consumes the service. Consider for example a German resident going on holiday to the UK. Any night spent in a UK hotel is considered as an export from UK to Germany.

As explained in Table 1, a stronger Swiss franc not only reduces Germans’ incentives to go to Switzerland for their holidays, but also stimulates Swiss people to go to Germany for their vacation, given their relatively high purchasing power abroad.

Switzerland has historically been perceived as a “safe haven”. During turmoil, investors have a tendency to buy Swiss francs which produces the effect of strengthening the currency. In Figure , we show an index which represents the exchange rate between the Swiss franc and several other currencies. An increase in the index is an appreciation of the Swiss franc. As you can observe, we had strong appreciations during and after the 2008 Great Recession, as well as during the COVID-19, which was born as a health crisis, but soon turned into an economic crisis.

Figure 1: Nominal exchange rate between the Swiss franc and a set of other currencies

Figure 2: Exchange rate between CHF and Euro. How many CHF for 1 Euro.

If we focus more specifically on the exchange rate between the Swiss franc and euro and on the period between 2000 and 2018 (Figure 2), we can see that in 2000 the exchange rate between CHF and euro was 1.6 (1.6 CHF for 1 euro), while starting from the world financial crisis in 2008, we observe a progressive strengthening of the Swiss franc. During the crisis, Switzerland was perceived as a safe haven, which explains why investors started to strongly buy Swiss francs. Such a high demand increased the value of the Swiss franc, which almost reached parity with the euro (1 CHF = 1 euro) in 2011. This is why the Swiss National Bank (SNB) intervened in September 2011 introducing a limit to Swiss franc appreciations with respect to the euro. With this intervention, the SNB committed to acting on the forex market with the goal of preventing the exchange rate to go below 1.2 CHF for 1 euro. This intervention lasted until January 2015, when the SNB decided that it was time to let the exchange rate freely fluctuate. As you can see from the picture, that same day, the CHF strongly appreciated and reached parity with the euro (1 CHF for 1 euro).

Having observed the fluctuations in hotel demand and pricing, we study whether these fluctuations are associated to exchange rate movements.

- In order to do so, we classify hotels by geographic market , class (luxury, up upscale, upscale, up midscale, midscale and economy) and type of operation (independent, franchise and chain) and we analyze how the different categories of hotels respond to exchange rate appreciations.

- Additionally, we focus our attention on the intervention of the SNB and we study whether it affected the behaviors of hotels and clients between June 2011 and January 2015. Is it possible that pricing and consumption behaviors changed during the SNB intervention? Is it possible that agents (hotels and consumers) modified their behaviors knowing that the SNB was protecting them?

Hotel performance is surely related to local factors which go beyond hotel class and operation (business model). Northern areas of Switzerland seem to be more exposed to international competition and react more to exchange rate fluctuations. Southern and central areas are more touristic, but somehow seem more protected from international competition. One reason might be that their prices are relatively low with respect to the average Swiss hotel prices (central Switzerland) or another reason might be that their demand is quite rigid (Ticino for example has a relatively high average ADR and does not show any intention to reduce it because of exchange rate appreciations. Mountain regions have an average ADR but a relatively low occupancy).

Nevertheless, our results seem to suggest that chains and higher class hotels (luxury, upscale) have a better ability to insure themselves against exchange rate fluctuations. If necessary, independent hotels also limit their losses, but in a way that is different from chains. Independent hotels simply do not react to shocks at all, while chains are more prone to change prices in response to market forces.

Data suggest that over time the market is expanding in a stronger way in the regions that better react to exchange rate appreciations (Figure 3): Lake Geneva and Northern Switzerland. In fact, even if during the last decade hotels in this region had to face some negative shocks that implied some losses, we should always remember that, on average, their performance is well above the one of all the other parts of Switzerland.

Similarly, we observe in the last twenty years an important increase in luxury and upper scale hotels (Figure 4), and chains (Figure 5), which seems quite consistent with our results.

Figure 3: Evolution of hotels by region between 2000 and 2018

Figure 4: Evolution of hotels by class between 2000 and 2018

We also observe a larger increase in chains and franchises rather than in independent hotels, which still represent the vast majority of hotels in Switzerland.

Figure 5: Evolution of hotels by operation between 2000 and 2018

The present study was conducted before the COVID-19, using data between 2000 and 2018. Nevertheless, its main implications may apply also now. During the first months of this health crisis that soon turned into an economic crisis, the Swiss franc in fact showed a tendency to appreciate towards most of the currencies (Figure 1), replicating a situation similar to the one that we observed during the 2008 crisis. Future research will have to delve deeper into the analysis to understand whether the recent franc appreciations produced similar results on the hotel industry as the ones that we observed during and immediately after the Great Recession of 2008.

Associate Professor in Economics at EHL

Keep reading

Navigating challenges of AI and maximizing value in the service sector

Apr 16, 2024

11 essential hospitality skills for career success (& resume tips)

Apr 15, 2024

Unlocking AI in Hospitality SMEs: Q&A with Ian Millar

Apr 11, 2024

This is a title

This is a text

- Bachelor Degree in Hospitality

- Pre-University Courses

- Master’s Degrees & MBA Programs

- Executive Education

- Online Courses

- Swiss Professional Diplomas

- Culinary Certificates & Courses

- Fees & Scholarships

- Bachelor in Hospitality Admissions

- EHL Campus Lausanne

- EHL Campus (Singapore)

- EHL Campus Passugg

- Host an Event at EHL

- Contact our program advisors

- Join our Open Days

- Meet EHL Representatives Worldwide

- Chat with our students

- Why Study Hospitality?

- Careers in Hospitality

- Awards & Rankings

- EHL Network of Excellence

- Career Development Resources

- EHL Hospitality Business School

- Route de Berne 301 1000 Lausanne 25 Switzerland

- Accreditations & Memberships

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Terms

© 2024 EHL Holding SA, Switzerland. All rights reserved.

The consequences of exchange rate trends on international tourism demand: evidence from India

- Research Paper

- Published: 08 August 2019

- Volume 21 , pages 270–287, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Akhil Sharma 1 ,

- Tarun Vashishat 2 &

- Abdul Rishad ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1418-5619 1

1502 Accesses

5 Citations

Explore all metrics

Exchange rate is frequently considered as a key determinant in international tourism demand models. Tourism export is one of the major sources of India’s foreign exchange earnings. So understanding the dynamics of exchange rate and tourism is essential for planning and execution of tourism policies. This paper empirically investigates the extent to which exchange rate fluctuations affect India’s international tourism receipts. In order to achieve this goal, the paper employed quarterly data ranging from 2003Q1 to 2017Q4 within an Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) framework. Using Wald coefficients, the study found cointegration among the variables. It further discovered that variables are correcting the shock-induced disequilibrium at a high speed of 96%. Furthermore, the study established a significantly negative link between exchange rate and international tourism receipt. We also found that the overall impact of the exchange rate is time-invariant, i.e. having similar long-run and short-run impacts on international tourism demand, though the short-run magnitude is higher than the long-run one. The outcomes of this study help practitioners to frame suitable policies to manage their currency exposure. Based on findings, the study suggests better management of the exchange rate to protect the external competitiveness of rupee for attracting more foreign tourists. Moreover, development of innovative hedging instruments helps to reduce currency exposure of international tourists.

Similar content being viewed by others

How Corruption Mitigates the Effect of FDI on Economic Growth?

Ismahene Yahyaoui

Interest Rate Volatility and Economic Growth in Nigeria: New Insight from the Quantile Autoregressive Distributed Lag (QARDL) Model

Godwin Olasehinde-Williams, Ruth Omotosho & Festus Victor Bekun

Impact of Foreign Aid on Economic Growth in Ethiopia

Belay Asfaw Gebresilassie, Tibebu Legesse & Girma Gezimu Gebre

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the most recent decades, a remarkable growth has been witnessed by tourism across industrialised and emerging economies as one of the foremost drivers of socio-economic progress. The global tourism sector is now worth over US$ 1.6 trillion in terms of total export value, which is accounted for 10.4% to the global gross domestic product. Additionally, 7% of world exports are associated with tourism, which ranks third after chemicals and fuels (UNWTO Tourism Highlights 2018 ). Due to its growing importance, there is no surprise that multifarious studies have been conducted on different aspects of the tourism domain (De Vita 2014 ; Lee et al. 1996 ; Song and Li 2008 ; Prideaux 2005 ; De Vita and Kyaw 2013 ; Carey 1991 ; Garín-Muñoz 2006 ; Law et al. 2004 ; Lee 1996 ; Wang 2009 ; Chatziantoniou et al. 2013 ; Chao et al. 2013 ).

Broadly speaking, the variables in the international tourism studies are divided into qualitative and quantitative variables (Peng et al. 2012 ). Song and Turner ( 2006 ) pointed out that the latter is more prevalent in the empirical literature. Qualitative factors such as safety issues, cultural issues and socio-political instability play a significant role in influencing the tourist flow (Patsouratis et al. 2005 ). It is not easy to measure the impact of such qualitative factors, but their impact is clearly visible in the pattern of tourist flow. Apart from this, quantitative factors such as disposable income, transportation cost, cost of living and exchange rate fluctuations influence international tourism demand (Dwyer et al. 2002 ). Modelling these economic factors with suitable econometrics framework can help to explain the intensity of influence of these factors on tourist flow in an economy. Despite the above, other significant determinants which have been discussed in the literature include foreign direct investment flows (Abbott and De Vita 2011 ; Abbott et al. 2012 ), climate change (Lise and Tol 2002 ), destination promotion (Crouch et al. 1992 ; Law et al. 2004 ; Lee 1996 ), level of income distribution and inequality (Morley 1998 ), education level of tourist (Alegre and Pou 2004 ) and rate of unemployment (Cho 2001 ). However, earlier tourism demand studies focused on conceptualisation and identification of exogenous variables (Witt and Martin 1987 ; Martin and Witt 1988 ; Uysal and Crompton 1984 ), whereas recent studies are more inclined towards econometric modelling and forecasting techniques (Song and Li 2008 ; Shen et al. 2011 ; Dogru and Sirakaya-Turk 2016 ).

The growth of tourism in the last few decades has made a radical shift in the employment pattern and the sectoral contribution to the gross domestic product of Emerging Market Economies (EMEs) including India. With the adoption of a floating exchange rate regime to supplement new economic policy in 1991, India witnessed a remarkable growth in terms of foreign tourist earning. However, despite its potential as an exotic destination, India ranks at the 17th position globally in terms of international tourist arrivals with 27.3 US$ billion tourism export which accounts to 5.8% of the total export of India (UNWTO 2018 ; WTTC 2018 ). As tourism is the third highest contributor to India’s foreign exchange earnings (Kaur 2017 ), acceleration of tourism activities improves the non-debt portion of country’s reserve and helps in stabilising the exchange rate which further accelerates the trade and capital flow. Thereby, it is necessary to attract more foreign tourists towards India which in turn bring excess foreign currency that can help in reducing Balance of Payment (BoP) and boost the tourism export for the country.

In the last few years, exchange rate has emerged as one of the widely used indicators for measurement of the international tourism flows alongside other economic and social determinants (Patsouratis et al. 2005 ; Song and Li 2008 ; Zhang et al. 2009 ; Santana-Gallego et al. 2010 ; Kah and Lee 2013 ; De Vita 2014 ; Agiomirgianakis et al. 2015b ). The changes in exchange rate not only garner responses from the potential travellers, but also the absence of hedging market forces the business to be shifted from an economy with high exchange rate instability to an economy with low exchange rate instability having a more stable currency rate for managing economic exposure (Crouch 1994d ; Agiomirgianakis et al. 2015a ). Exchange rate fluctuation influences the potential travellers to change the destination or reduce the length of the holidays which results in revenue loss to the economies. This may cause changes in the travel itinerary of tourists while visiting a particular country (Webber 2001 ). Therefore, there is a need to monitor, track and predict these exchange rate fluctuations and formulate effective mechanisms (WTTC 2016 ). In the case of emerging Asian economies, the introduction of a more flexible exchange rate regime and devaluation of currency is attracting more foreign tourists (Chang and McAleer 2009 ). Such a radical shift in exchange rate regime brings countries to the list of international destinations. From the international trade point of view, countries keep their currency devalued for competitive advantages. But this competitive advantage on exchange rate elasticity in the case of tourist inflow depends on the risk-taking behaviour of the agents and the exchange rate of the destination country as well. For instance, the South East and South Asian currencies are relatively cheaper for tourists originating from Western countries. Therefore, small fluctuations in the exchange rate of these currencies may not be much influential in impacting the travel decision of the tourists.

For understanding such dynamic relationship between exchange rate and international tourist inflow, the previous studies have used the nominal exchange rate as a proxy for measuring potential risk in tourism demand model which may not be adequate as it neglects the relative price level at the destination. In order to rectify this issue, studies such as Kim and Lee ( 2017 ), Eilat and Einav ( 2004 ) and Edwards ( 1995 ) were given more emphasis on the relative price level in the destination countries. But including exchange rate and consumer price index simultaneously may cause multicollinearity in the model (Zhang et al. 2009 ).

Following the arguments of Chen ( 2008 ), this study fortifies that exchange rate is the key contributing factor of international tourism demand. By investigating in seclusioning the impact of exchange rate on global tourism inflow to India, the present study explains how this factor influences the international tourism demand. A unique combination of real effective exchange rate within an ARDL framework explicates elasticity of exchange rate in explaining the global tourism demand to ‘Incredible India’.

The next section of this paper provides an overview of the relevant empirical studies followed by the methodological aspects adopted in the study along with details of the data. There on, the outcomes of the empirical research are discussed. The penultimate portion concludes the research and lays down the policy recommendations.

Review of the related literature

The expansion of tourism as an industry has significantly contributed to the gross domestic product of nations and attracted more researchers and policymakers to investigate its various aspects. Both qualitative and quantitative factors were used as explanatory variables to estimate the tourism demand function in the second half of the twentieth century (Lim 1997 ). Later on, it was found that methodological and data-related constraints limited the scope of these studies (Narayan 2003 ). The development of econometric techniques and the availability of high-frequency data on different elements of tourism contributed to the development of an innovative methodological framework for the analysis to produce accurate and actionable results. Theoretical and empirical literature highlights four major determinants of cross-border tourist inflow in the recent scenario. It includes direct determinants such as the cost of transportation, exchange rate, the relative price level in origin and destination countries (Crouch 1994b ; Garin-Munoz and Amaral 2000 ; Li et al. 2005 ; Song and Li 2008 ). The previous researches have given more emphasis on the relative price level at the destination countries because tourism demand is highly price elastic (Crouch 1995 ; Patsouratis et al. 2005 ; Önder et al. 2009 ).

For computation of tourism price variable, the majority of studies have used Consumer Price Index (CPI), exchange rate and CPI-adjusted exchange rate as an alternative variable for the cost of destination (Li et al. 2005 ). There are contradictory arguments on the use of CPI as a proxy for relative price level in the host country. Earlier studies argue that CPI is a good proxy as it closely captures the price of travel and tourism (Martin and Witt 1987 ; Morley 1994 ; Uysal and Sherif El Roubi 1999 ; Culiuc 2014 ); however, certain issues were also identified in this approach. For instance, CPI represents the cost of a selected basket of goods and services consumed by an average household in a domestic country which is entirely different from the consumption pattern of the tourists (Chasapopoulos et al. 2014 ). To overcome this issue, studies such as Berkhout ( 2007 ) and Goral and Akgoz ( 2017 ) came up with a separate tourism price index for various countries after considering consumption patterns of tourists. However, the complexity and irregularity of its calculation limit the use of such indices in tourism models (Divisekera 2003 ; Rosselló et al. 2005 ). Using CPI with exchange rate may also cause multicollinearity in the model as the exchange rate indirectly absorbs the changes in CPI (Lim 1997 ; Zhang et al. 2009 ). Keeping this argument in mind, this study used the real effective exchange rate as an appropriate alternate for tourism price variable which replaces exchange rate as well as price level together.

The past studies have employed different variables for examining tourism demand. For instance, the amount of money spent by tourists, tourism receipts, imports and/or export of tourism are considered proxies for tourism demand in the monetary approach. In the non-monetary framework, number of tourist arrival/departure and number of nights/day spend, and the average length of stay per tourist in a particular destination is considered as a proxy for tourism demand (Crouch 1996 ; Lim 1997 ). However, obtaining reliable data on these variables is difficult. On the other hand, data on tourists arrival are easily accessible and more reliable, but their responses to the determinants are poor (Zhang et al. 2009 ). In order to avoid such issues, this study used the receipts from international tourism as a proxy for measuring the inbound tourism demand in India.

Moreover, including the gross domestic product of the host country in the model as a proxy for infrastructural development, the standard of living and economic condition helps to examine how these factors influence destination decisions of international tourists (Belloumi 2010 ). The connections between these variables are well explained by economic theories. This paper does not consider the income of origin countries as Patsouratis et al. ( 2005 ) argued that income of origin country could be ignored if the host countries’ currency is cheaper to the country of origin.

Gerakis ( 1965 ) made the first ever effort to measure the effects of exchange rate variations on the foreign tourist receipts while conducting a comparative study of Canada, Spain, France, Yugoslavia, Finland, Germany and Netherlands between 1954 and 1963. He found a remarkable increase in the tourist receipt of France, Spain and Yugoslavia and a modest increase in the case of Canada. But the currency revaluation of Finland, Germany and Netherlands negatively influenced the tourism receipts and significantly accelerated the receipt of main competitors. Similar findings were later reported by Gray ( 1966 ) and Chadeeand and Mieczkowski ( 1987 ) confirming that Canadian tourism imports were quite elastic to exchange rate. Subsequently, Artus ( 1970 ) assessed the effect of the revaluation of Deutsche Mark on the German receipts from foreign visitors, and it was found that the price sensitivity of the German receipts from foreign tourists was quite high. Lin and Sun ( 1983 ) in their research project on the tourism sector in Hong Kong found that international tourists’ flow was highly elastic to exchange rate. In addition, Garin-Munoz and Amaral ( 2000 ) studied the effects of exchange rates on demand for Spanish tourist services in the international markets. The resulting exchange rate elasticity of +0.50 showed that devaluation of the Peseta would boost the international tourist flows to Spain. Webber ( 2001 ) investigated the impacts of exchange rate volatility on Australia’s outbound leisure tourism demand with respect to nine countries in the long run. The results showed that exchange rate fluctuations were a significant determinant of tourism demand in the long run and tourists were likely to drop the plan of visiting a particular nation in 40% of the cases. Likewise, Dritsakis ( 2004 ) utilized the exchange rate as a factor to explain the long-run tourism demand for Greece by Germany and Great Britain. The analysis revealed that real exchange rate is inelastic for German tourists and elastic for Great Britain tourists. Patsouratis et al. ( 2005 ) established exchange rate as the predominant determinant of tourism demand of Greece with respect to alternate Mediterranean destinations such as Italy, Spain and Portugal offering the same product. The findings of Quadri and Zheng ( 2010 ) on Italian tourism demand showed that the exchange rate did not have any significance in 11 out of 19 country pairs. They further established that exchange rate volatility does not always affect international arrivals universally. Chang and McAleer ( 2009 ) examined daily and weekly tourist arrivals to Taiwan from different parts of the world including USA and Japan along with the world price, JPY/TWD and USD/TWD exchange rates, and their associated volatility. The analysis suggested that the exchange rate was having an expected negative impact, whereas volatility exerted either positive or negative effects on tourist arrivals to Taiwan. Yap ( 2012 ) studied the impact of the rising value of the Australian Dollar on its destination competitiveness as compared to the neighbouring countries. For nine countries of origin, the sensitivity to exchange rate volatility was examined, and it was inferred that sudden currency shocks would not have long-term implications for Australian tourism imports. More recently, researchers examined the relationship between tourist arrivals and exchange rate volatility for the UK and Sweden. The relationship turned out to be negative, indicating that the choice of travel destination is affected by exchange rate fluctuations (Agiomirgianakis et al. 2015a ).

Many academic studies in the past considered exchange rate as an independent variable as it is a theoretically strong proxy for relative price. Theoretical arguments justify its use for two reasons. Firstly, tourists are more aware of exchange rate than the prices of individual products and services in the host country (Artus 1970 ; Martin and Witt 1987 ; Crouch 1994a , b , c , e ; Webber 2001 ). Secondly, exchange rate fluctuation (especially the case of floating exchange regime) is directly linked to the cost of the trip and ultimately influences destination decisions (Lim 2006 ). Such a relationship is based on the idea that currency depreciation makes the destination cheap and increases the number of foreign tourists (Greenwood 2007 ). So, excluding the exchange rate from the international tourist demand model makes the model spurious. But the use of exchange rate exclusively as variables to measure the cost of living might be inaccurate. The benefit of a higher exchange rate scenario could be dampened by hyperinflation in the economy (Witt and Witt 1995 ).

All the above-mentioned studies highlight the fact that exchange rate variations influence the growth rate of international tourism across the globe. Understanding the impact of exchange rate fluctuation on tourist demand is highly useful for policymakers and academicians. There is a severe gap in research from developing economies, especially South Asian economies, which earn well from international tourism. There are a limited number of studies which have examined the tourism demand of India (Dhariwal 2005 ; Madhavan and Rastogi 2013 ). But these studies have not given proper attention to price level and exchange rate as key determinants of international tourist flow.

This study is an attempt to fill that gap and to contribute to an improved understanding of the relationship between exchange rate and international tourism demand. Using the ARDL model, the authors investigate how the exchange rate fluctuations have influenced international tourism receipt during the post-liberalisation period in India so as to facilitate relevant policy-making and academic pursuits.

Methodology and data

Theoretical framework.

International tourism can be considered as a form of international trade in services. However, specific models developed within the theoretical premises of international trade to understand tourism as a trade in services are absent. International tourism, as a trade, has unique characteristics. For instance, unlike many other trades, a customer in this case has to visit the exporting country to consume its products (Cheng et al. 2013 ). Moreover, its products are imperfectly substitutable due to the unique role played by multicultural and geographical factors. International trade theories postulate a negative relationship between price and demand of tourism products. Hence, this study adopted a theoretical model based on the assumptions of demand theory. As per the tenets of Neoclassical Consumer Demand Theory, international demand for tourism products depends on the relative price of all goods and services consumed by the tourists. An increase in the price of domestic goods and services reduces the demand for tourism export as it influences the purchasing power of money (as per the theory of Purchasing Power Parity).