A Communal

Response to, pb&j walking tours.

Welcome regularly takes groups on walking tours to learn about homelessness and poverty. First, we make peanut butter and jelly sandwiches together while we get to know each other and learn about homelessness in San Francisco. Then, we walk through the neighborhood handing out sandwiches and talking to homeless and hungry individuals while we stop at locations that help participants learn more about the issues affecting local poverty. Walking tours occur in San Francisco's Polk Gulch, Tenderloin and Castro neighborhoods.

Groups interested in learning more about PB&J service projects should contact the Rev. Dr. Megan Rohrer: [email protected]

Your secure online donation will help us provide eye glasses, advocacy and support to the homeless in San Francisco.

Learn some tangible ways to make a real difference where you live. Replicate our projects, volunteer and find DIY guides.

Welcome seeks to provide a faithful response to poverty and to improve the quality of life for individuals in our community through hospitality; the arts; education; food; and referrals.

The ‘doom loop’ isn’t the whole story in San Francisco

San Francisco is undeniably having a moment.

Over the past year, headlines claiming the city is caught in a spiraling “doom loop” have become so prominent that a city commissioner decided to cash in on downtown San Francisco’s storefront vacancies, homelessness and opioid issues by anonymously advertising an hour-and-a-half long tour showcasing “doom and squalor.” For $30 a person, you could see the city’s “open-air drug markets” and “abandoned tech offices” first-hand.

However, just before it was scheduled to take place, the tour was canceled (and the commissioner ultimately resigned). Instead a more “positive” walk organized by a local nonprofit guided participants through the city’s Tenderloin, highlighting a neighborhood that’s long been a poster child for the city’s hardships.

While people sleeping on sidewalks and drug use were still visible, it focused on the community’s more positive attributes, including a rich history, art and a career center that’s working to get struggling San Franciscans back on their feet.

Still, for many would-be visitors, it’s San Francisco’s more discernible difficulties that are the real deterrents.

“My clients who’ve recently been to San Francisco have never said they felt unsafe,” says Alana Scalise Livingston, owner of Wander Spokane tours in Spokane, Washington (and a former San Francisco resident). “They just say it’s not as nice as it used to be, and there are many homeless people flooding the streets.”

Joshua Hirsch, owner of Sidewalk Food Tours SF , has received much of the same feedback. “According to our tour participants, the homeless people in cities like San Francisco and New York seemed to have become more brazen and outspoken since the pandemic,” he says. “They think it’s their neighborhood, and you don’t even have the right to be walking on the sidewalk.”

Additionally, there’s the city’s so-called “death spiral” or “doom loop” touted by news outlets (including the city’s own ) – in which remote work leads to empty real estate , resulting in less foot traffic and then shuttered restaurants and reduced public services. This in turn leads to more overt drug activity as well as unhoused individuals congregating in front of unoccupied spaces.

It’s not that the tales of downtown retail stores closing in bulk and vacant office buildings are untrue, nor are the stories of drugstore chains such as Walgreens locking up most everything in the store behind see-through cabinets, though the latter is occurring in other big cities nationwide .

San Francisco has also been experiencing a rash of car break-ins, including this SF Whole Foods garage break-in video that went viral in Indonesia , that many fear could have long-lasting effects on the city’s tourism.

This past June, the investment firm behind the Hilton San Francisco Union Square (at 1,921 rooms, it’s the city’s largest hotel) and the nearby Parc 55 hotels announced that it is stopping payments on a $725 million loan and surrendering the remaining debt to its lender. Tech companies such as Red Hat and the SF Bay Area’s own Meta have decided to cancel their 2024 conferences in San Francisco as well, citing ongoing concerns over safety and the cleanliness of downtown streets.

‘It felt vibrant and alive’

It seems like everywhere you turn, the news about San Francisco just keeps getting worse. Or is it just the news we’re reading?

“We definitely feel like there is a significant misconception of what is really happening on the ground,” says Dina Belon, chief operating officer at Staypineapple Hotels , which has a property in San Francisco’s Union Square district.

Yuki Hayashi, a Toronto-based marketing writer and editor who visited San Francisco in late July for the city’s annual marathon, agrees. “Based on what we saw on Reddit, my family and I thought the city had turned into some post-apocalyptic hell zone,” she says. “But instead it felt vibrant and alive.”

The San Francisco hoteliers and restaurateurs interviewed for this article acknowledge that a drop in the city’s tourism this summer has been evident. That’s the result of a combination of factors, they say. They include the negative headlines and fewer full-time office workers, “which has significantly reduced our business and corporate travel,” says Belon. There’s also the absence of Chinese tourists — which pre-pandemic was one of the city’s top international markets — because of Covid and flight restrictions.

But they also agree that many of the gloomy headlines have been misleading.

“Yes, there are parts of San Francisco that need work,” says Marc Zimmerman, owner and executive chef at Gozu , a modern Japanese eatery located in the city’s East Cut neighborhood. “I don’t think we should pretend that the city doesn’t have issues. But the whole idea that, you know, everybody’s just laying around every SF street with needles hanging out of their arms is definitely a stretch.”

Ben Parks, board chair for San Francisco City Guides , feels similarly.

“It’s like, if the negative media coverage is all you pay attention to,” he says, “you just really miss out on everything the city has to offer.”

His all-volunteer organization has been leading free walking tours citywide for nearly five decades and currently has 79 offerings. Parks says that these days, their attendance has actually been increasing, with what the organization suspects are more local residents interested in learning about the city’s neighborhoods, which in many cases are where San Francisco continues to impress.

“There are so many good things happening in many of our neighborhoods and communities,” Grace Horikiri, executive director of San Francisco’s Japantown Community Benefit District , “and it often gets overshadowed by all the non-positive news.”

Within the past year, Japantown has welcomed new restaurants such as Copra and Fermentation Lab , saw the opening of the Kimpton Hotel Enso in its former Buchanan Hotel space and watched the growth of its popular monthly Mini Art Market in the community’s Japantown mall.

New businesses, new life

The city is also seeing new life in some of its major tourism hubs.

This August, IKEA bucked the trend of major retailers moving out of downtown and opened a San Francisco store focusing on small-space living along Market Street (between Sixth and Fifth streets), while more than 15 local small businesses , including Devil’s Teeth bakery, Holy Stitch! apparel and The Mellow, are setting up pop-up shops in vacant downtown storefronts, beginning mid-September.

Over in Fisherman’s Wharf, San Francisco’s iconic Ghirardelli Chocolate Company hosted the grand reopening of its Original Ice Cream and Chocolate Shop in July after a six-month renovation. The city’s LUMA hotel , which opened in 2022 adjacent to the city’s Chase Center sports and entertainment area, even won Tripadvisor’s 2023 Travelers’ Choice Best of the Best award, despite San Francisco’s negative narrative.

Chinatown, a neighborhood especially hard-hit by the pandemic, is hosting a series of new festivals, including a Halloween Festival on October 28. In January, the community also saw the long-awaited opening of its Rose Pak Muni metro station , providing Muni light-rail riders direct access to the heart of Chinatown’s streets.

Whether it’s Golden Gate Park’s 1.5-mile stretch known as JFK Promenade, with its Adirondack chairs; street art and playable pianos, which became permanently vehicle-free during the pandemic; or city stalwarts such as Amoeba Records in the Haight-Ashbury (which Santa Cruz bookseller Liz Pollock says is still filled with people “flipping through LPs” every time she visits), the city is in many ways just going about its business.

‘We needed a kick, and we got it’

Homelessness has been an ongoing issue in San Francisco, with thousands of homeless people sleeping on the streets on any given night, and the effects of the pandemic have brought it even more to the city’s forefront. “The challenges that San Francisco has always had are just more visible,” says Belon.

However, when it comes to violent crimes in US cities, San Francisco’s numbers are comparatively low. Larceny , such as car thefts and break-ins, is what really drives up crimes figures in the city and at the same time drives away visitors.

“We can’t just act like nothing is wrong,” says Zimmerman, “but for whatever reason, that’s the direction we went. But I feel like we needed a kick, and we got it. This is a great and resilient city, and now we’re seeing a big push to bring it all back.”

To help curb auto break-ins, the San Francisco Police Department is beginning to deploy bait cars that can help identity and arrest thieves, notably in tourist areas such as the Palace of Fine Arts, Alamo Square and Fisherman’s Wharf.

Getting homeless people off the streets and into places where they can get viable help (mental and physical) isn’t so easy, but that’s not to say efforts aren’t being made. In December 2022, a federal judge effectively barred the city from breaking up or sweeping tent encampments until there are more shelter beds than individuals, but the issue isn’t so cut and dry .

While the San Francisco Homeless Outreach Team works collaboratively with the Department of Public Health’s Street Medicine team to address the medical and behavioral health needs of many of the city’s homeless residents and also to offer them volunteer overnight shelter, many would rather stay on the streets for reasons such as feeling unsafe in shelter and the inability to keep their belongings with them.

Still, says Zimmerman, “It’s a different experience for those of us who walk around San Francisco every day. Yes, there are parts of the city that need work. But just in the neighborhood of Gozu, you’ve got Salesforce Park that is beautiful. The ballpark is beautiful. This is the perfect opportunistic position for San Francisco to bounce back.”

While raising capital for his newest venture, Yokai, a new hi-fi listening bar with cocktails and food that’s scheduled to open just a short walk from Gozu in mid-September, Zimmerman first heard a term that he’s since adopted as his own: “SF long,” which investors and other long-term San Francisco residents have been using to show their commitment to the city.

“It means, ‘we’re weathering this out together, and we’re not going anywhere. We’re in it for the long haul,’ ” Zimmerman said.

For all of San Francisco’s perceived and more evident troubles, the city still has a lot going for it.

“We have the geography,” says Zimmerman, “the location — with both Napa and Sonoma both an hour north — the restaurant scene, some great museums, and this awesome cultural melting pot of people. The whole thing is very unique.”

Others such as Belon, Pollock and Livingston feel the same. “It’s the whole experience of it,” says Pollock, “and you can’t find it anywhere except San Francisco.”

Laura Kiniry is a freelance journalist and 28-year resident of San Francisco. She lives in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com

San Francisco's New 'Street to Home' Program Expedites Housing People and Reduces Vacancies in City Funded Homeless Housing

San Francisco, CA -- Mayor London N. Breed today announced that Street to Home, a new innovative initiative, is expediting the process of providing housing for people experiencing unsheltered homelessness in San Francisco and maximizing the use of existing vacant units in the City’s Homelessness Response System. The new program, in partnership with Delivering Innovation in Supportive Housing (DISH), is part of the City’s ongoing commitment to bring people inside and connect them to a wide range of existing services and placements.

San Francisco's Five-year Strategic Homeless Plan, Home By the Bay , sets a goal of cutting unsheltered homelessness in half over the next five years. This builds on the 15% reduction in unsheltered homelessness San Francisco has seen since 2019. The Mayor has directed the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing (HSH) to bring forward and implement new initiatives as part of these efforts. By leveraging vacant units within HSH’s portfolio, this program will streamline the process of transitioning individuals from the streets to permanent housing, ensuring a more efficient and compassionate approach.

“Street to Home is all about removing the barriers that slow us from making a real difference for our City and for people living on our streets,” said Mayor London Breed . “We have to be creative and not let barriers and bureaucracy get in the way of helping people. To build on the success of this pilot, we are advocating to relax federal rules so we can bring this program to more of our buildings across the City.”

HSH has recently piloted Street to Home in June, successfully placing 12 people over a three-week pilot period and in total 18 highly vulnerable people have been moved off the streets into long term housing.

The success of the pilot demonstrates that people living unsheltered are interested in long-term solutions to their homelessness, that housing placements can be expedited, and reducing the number of PSH vacancies in our community is possible by employing creative ideas and getting rid of bureaucracy in the housing placement process.

“We believe that everyone deserves a safe and stable place to call home,” said Shireen McSpadden San Francisco Director of Homelessness and Supportive Housing . “With Street to Home, we are taking a proactive approach to addressing street homelessness and creating a low barrier way to get people from the street into housing. This pilot program is a testament to our commitment to finding innovative solutions to the challenges our city faces.”

As part of Street to Home, the San Francisco Homeless Outreach Team (SFHOT) and the Housing Placement Team will first allocate units and then identify eligible individuals living on the streets. Those who are eligible will be shown a designated available room with the option to sign a lease and move in on the same day. In the interest of moving people more rapidly from the street, documentation will follow this process within 90 days of placement; there will no longer be a requirement to make the initial placement.

Currently Street to Home can only be implemented on locally funded projects due to requirements at the federal level that the City cannot waive. However, the Mayor has requested from HUD that these requirements be waived to allow direct placements into federal projects in order to extend the reach and impact of Street to Home.

“At DISH our number one priority is welcoming people home,” said Lauren Hall, executive director, Delivering Innovation in Supportive Housing (DiSH) . “We are thrilled to partner with the City to ensure that our supportive housing programs truly meet people where they are. With this pilot we can cut through processes that can unintentionally leave people on the streets and provide a true solution to being unhoused--a dignified safe place of their own.”

The Street to Home program will prioritize individuals who have been living on the street for an extended period and those who are most vulnerable. By providing direct placement into housing units, the program aims to reduce the trauma and instability associated with homelessness with a path toward stability.

In addition to Street to Home, HSH is engaging in process improvement and bureaucratic reforms to reduce the barriers to rapid housing placement by:

- Making significant budget investments in property management for quicker unit turnover and higher unit quality.

- Creating a Housing Placement team within HSH to improve the housing placement process for tenants and housing providers.

- Instituting updated protocols for unit refusals and participation, coupled with increase in referrals.

- Piloting a referral pipeline for clients who are “engaged” and have high level of documentation, including unsheltered people.

- Continuing to refine pre-referral review process, including Continuum of Care (CoC) eligibility.

- Establishing self-certification for placements as permitted under U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) regulations.

- Expanding document-readiness role of shelter case managers.

- Implementing monthly review of vacancies from provider reports to improve data quality and inform the work.

For more information on San Francisco’s five-year strategic strategy to address homelessness, visit https://hsh.sfgov.org/about/research-and-reports/home-by-the-bay /.

###

Departments

One day, one city, no relief 24 hours inside San Francisco’s homelessness crisis

24 hours inside San Francisco’s homeless crisis

Published July 31, 2019

About this project:

For the fourth year, The San Francisco Chronicle is leading the SF Homeless Project, a consortium of media organizations focusing on the seemingly intractable problem of homelessness. The Chronicle's ongoing coverage, including stories, videos and interactive graphics, can be found at SFChronicle.com/homelessness .

Supported by

San Francisco spends more than $300 million a year fighting homelessness. Yet it’s not working – at least not enough. Amid a housing shortage, rampant drug addiction and a failing mental health care system, the everyday crisis on our streets has intensified.

On June 18, 36 Chronicle journalists spread across the city to document a typical 24-hour period in this epidemic, witnessing an unrelenting cycle of striving and suffering, of some people finding their footing and others falling through.

The day started just before dawn, along the Embarcadero.

The waterfront and a wheelchair

The Embarcadero is silent before dawn except for the whoosh of street cleaners. The loose band of meth-addicted homeless people who live near the waterfront have scattered, waiting to return at morning light. The techies and bankers who fill the Financial District towers above haven’t yet arrived.

Alex “Shorty” Pierson lurches awake from his off-and-on slumber in front of a nearby 7-Eleven.

Floyd and A.J. lie on the sidewalk beside Shorty’s battered wheelchair. The young men are there, in part, to help: Afflicted with osteogenesis imperfecta since birth, 36-year-old Shorty can’t walk and has limited use of his arms, so he’s dependent upon a couple dozen homeless friends to roll him where he wants to go.

He’s been living outside for much of the last 20 years, since he left his mother’s home because he was “hard-headed.” Shorty is what officials consider chronically homeless, having slept on the street for more than a year. He lives in the wheelchair with supplies stuffed behind his back. He hasn’t showered in two weeks.

A.J. rolls him across the street to a shopping center with an outdoor outlet to charge their phones. Shorty’s was stolen a couple of days before, and the replacement he bought for $10 on the street came uncharged. As it lights up, he punches in YouTube and gets Nipsey Hussle rapping “Racks in the Middle” at top volume.

Shorty sings along: “You can't imagine this s—!”

BART opens with a blitz

The gates open with a clang at Civic Center Station. BART is in “blitz” mode.

Cops and yellow-vested employees watch the entrances. Since April, the agency has sent extra workers downtown every day to bust fare evaders and discourage transients from using trains as quasi-homes, a problem that’s frustrated riders for years and prompted some to shun the system. The effort, politically fraught, casts BART in a second role: social service provider.

The crackdown is working, at least for now: Speakers play classical music over a walkway that used to be a hangout for slumped-over drug users and now has an antiseptic sheen.

An hour later, two BART police officers snap cuffs on their first fare evader of the day — a man with a bag of stuff slung around a wrist and a syringe in his pocket. He speaks no English, has no ID.

“Hey, do we have anyone who speaks Cantonese?” an officer asks.

Twenty-five minutes later, the cops release him with a citation for fare evasion, though they know such fines are rarely collected. Flustered, he spills the contents of his bag: an empty takeout box, crumpled napkins, a few dollar bills.

“Sir, you have to move on,” Officer Rodney Barrera says, as the man shields his face with a forearm and whimpers.

“Sir, do you need medical attention?”

Charie Pittman walks over. The 45-year-old security guard for a nearby building grew up blocks away in the Tenderloin and was once homeless herself. The problem is cyclical in Pittman’s family: Her mother lives in a tent in Berkeley.

She bends over to reach the man on the floor.

“C’mon sweetheart, let’s go enjoy the sun.”

They shuffle up the stairs. A minute later, the man is gone and Pittman crosses Market Street alone, wiping away tears.

‘It’s hard to know what success means’

Jeff Kositsky drives down Evans Avenue in the Bayview district, toward the water, chasing a report of a surge of occupied RVs.

This is the kind of thing Kositsky, head of the city's Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, does on his way into the office. He likes to stay in touch with the street. And this tip is especially relevant. Since 2017, the number of people living in RVs, cars and other vehicles has jumped by 45% to 1,794 — a growing crisis tagged to rising rents that the city is struggling to address.

Kositsky slows and peers out the window. The seven RVs parked along the street look relatively clean. Still, he says, it’s not humane to allow people to sleep in their vehicles. But what is the city to do when there isn’t enough housing to offer these people?

“Is success that they leave and don’t come back?” he asks. “Or is it just that they drive around the corner and move somewhere else? It’s hard to know what success means.”

‘There is something magical about our city’

“Wake up. Come on, let’s go.”

On a bicycle, San Francisco police Officer Shante Williams is clearing SFO’s international terminal ahead of the coming crowds. That means rousing the homeless. He circles Stephanie Gant, 56, who’s asleep on a bench, her body bending around an armrest.

On the intercom, the voice of Mayor London Breed plays on loop: “Whether you’re here for work, play or a little of both, there is something magical about our city.”

Gant has lived in freeway encampments, but fears them. She worries about “spies” watching her. So she’s here.

“You’re one of my regulars,” the officer says.

“I’m not yours. I’m one of God’s.”

Homeless on and off for years, Gant arrived at the airport at 3:20 a.m. on a bus. She likes the safety and the cushioned benches of the airport. Police encounters with homeless visitors to the airport have tripled in two years.

Squeezed into food court booths or prone on benches, the homeless sleep among stranded passengers. Many could pass for inconvenienced tourists.

Gant takes an escalator downstairs and settles onto a bus stop bench. She stubs out a cigarette, pulls out an inhaler for her chronic lung disease and sucks back a couple breaths. Then she grabs a bus to San Mateo, planning to crash out in a park.

“I’m exhausted,” she says, tearing up.

College life in an Econoline

Back from a run up Mount Davidson and a shower in his college gym, Jimmie Wu pours a bowl of Cheerios as another day gets going in his Ford Econoline van. A modest meal in a modest existence.

He’s deep into a video on van maintenance when his phone vibrates with a reminder. Wu, 29, snaps to like an Army sergeant giving a salute.

“Food bank!”

He slips out of the vehicle, passes another parked van and two trucks housing military veterans like him, and hustles through the City College of San Francisco campus where they all are enrolled. He likes to have first choice of the free groceries offered on Tuesdays.

It’s all part of the cost-benefit analysis that Wu, an eight-year Army vet, did when he picked his hometown San Francisco for his education. Veterans attending college in the city get more money from the GI Bill than anywhere else in the country: $4,398 a month, because of the high cost of living. This can be the nation’s most expensive city — unless you skip rent.

Wu, who studies computer science, collects about $45,000 a year from the GI Bill, federal grants and military disability income from back injuries and post-traumatic stress. Although tuition at the community college is free, he has to pay for living expenses, books and incidental educational costs, which add up to about $18,000 a year.

By keeping things tight, he’s built up a savings fund in the six figures. No one knows how many people living in vehicles in the city have made a similar choice.

The idea of blowing his income on rent, Wu says, “is really crazy to me.”

Tents pop up, and complaints follow

A line and a puff to start the day

Shorty is hurting. Like every day about this time, he needs his first hit of meth. He hasn’t eaten anything since the afternoon before, but his guts are so tight from the need for that hit, his nerves so jumpy, that he can’t eat. He sits with his homeless friends in his wheelchair under a palm tree across from the Ferry Building and fidgets.

“Hey, Zito, I need you to take care of me,” he tells 45-year-old James Zito.

Zito pulls out a little box of dope, rolls up a dollar bill, taps a line of speed onto a lottery ticket and takes a snort. Then he lays out a new line on the ticket and hands it to Shorty.

“That’s a winner,” Zito jokes.

“It’s like medicine,” Shorty says, tipping back his head and grinning at the sky. “Now the day can get going.”

There’s little danger of cops busting him. In San Francisco, they focus on the big dealers, not the users.

The grin fades in moments. Shorty rolls a few feet away and lights up a pipe bowl of pot.

“The drugs, the addiction, are a damper on my life,” he says quietly, and Zito nods, overhearing. “You think we want to depend on this stuff? No. Deep down, we really want normal lives.”

A job, a shelter, a hope

“Bye, baby, I love you,” Derelle Foster says to his 18-month-old daughter, Ellarose.

“Bye,” the girl mutters back, waving a few tiny fingers.

Foster, 27, recently lost his job at a marijuana grow house. He and his family have been in a shelter for several weeks, after stints at another shelter, in motels and in a van. They lost their studio in Oakland in February. The landlord didn’t like how many people were living in the unit and, without a job, Foster didn’t have the money for a new place.

The room at the shelter operated by Hamilton Families is tight. Foster and his wife sleep in one bed, Ellarose and 8-month-old Sandra are in cribs, and 3-year-old Juston shares a bunk bed with the family’s German shepherd, Clicquot. A communal bathroom is down the hall.

But it’s better than the shelter’s dorm-style quarters that they were in before. And now Foster has a job again. He’s headed to work at the Coalition on Homelessness, the advocacy group in the Tenderloin, which just hired him at $15 per hour for an office job. It’s temporary, but he hopes this is the beginning of the resurrection of his life, a step toward renting a real home again soon.

“I’m tired of my kids asking, ‘When am I going to go back home?’ ”

A call from the mayor

Jeff Kositsky’s cell phone blares. It’s Mayor London Breed.

Two people at a Lower Haight intersection have spread their belongings along the sidewalk, she says. They look like they need help.

The city’s homeless chief not only knows who Breed is talking about, he knows their first names. The two have been in and out of the city’s shelters for years. Sounds like they’re back on the streets.

“Can you help them?” Breed asks.

“We’re on it. Thanks, boss.”

He calls the Homeless Outreach Team, the roving counselors who connect street people with shelters, treatment, case managers. It’s Kositsky’s first message from the mayor on this day. It won’t be the last.

‘We have to leave him here’

People like Adam (video above) represent one of the biggest challenges for the police team focused on homelessness. He’s not doing anything illegal. And he doesn’t meet California’s standard for an involuntary psychiatric hold, a 5150, which could bring rest and medication. He’d have to be deemed gravely disabled or a danger to himself or others.

Even if he was placed on a hold, the city is short of the facilities it needs to help him. The city spends nearly $400 million a year to supply 2,000 beds, 100 of which were added in the past year, but there are still scores of street people who appear as lost as Adam.

Forcing mentally ill people in need of help into treatment is a decades-old hot-button issue with no end in sight. New city and state laws to make conservatorship easier don’t come close to answering the problem, or the debate: Is it more humane to lock people into facilities, or wait for them to come to treatment voluntarily?

The veterans of Home Depot

Jimmie Wu parks in the rooftop lot of a Home Depot in Colma. Within minutes, a shiny blue van and a graffitied white truck rumble in, driven by three fellow veteran-students.

The friends, who study at City College of San Francisco, are getting together to work on their wheeled homes, sharing equipment and expertise and sometimes running into the store to buy a tool or use the bathroom.

Wu fires up an electric jigsaw and slices through plywood to build a cabinet to fit above his mattress. He expects to live in his Econoline for at least two more years while he completes his studies. His parents oppose his van life. But Wu is proud of his strategy.

One spot over, the graffitied white box truck belies the elegance within, including a queen-size Murphy bed built by the ex-combat medic who uses it. Mark Chopot, 47, is also proud, not only of his retrofits but of beating back the PTSD nightmares that had led him to sleep beneath bridges and try suicide in the past.

“This is where I want to be,” he says.

A married couple live in the third vehicle. Mariel, 28, has a bachelor’s degree in industrial design and sells jewelry and graphic art online. John, 27, is a vet studying business. Last year, he persuaded Mariel to live in a van with him — and now they’re able to send money to their families in the Philippines.

A job that hits home

Derelle Foster, the father of three living in a shelter, sits in the proudly rumpled office of the Coalition on Homelessness. One of the many posters on the wall reads, “Housekeys not handcuffs.” He’s new on the job.

The coalition’s Street Sheet, a bimonthly tabloid newspaper on homelessness in San Francisco, is freshly printed and stacked in piles near Foster’s desk. His task is to provide the papers to people on the streets so they can sell them for $2 a copy.

“Some need the money for a hotel room,” he says. “Some need it to feed themselves.”

One person comes in for 10 papers, another asks for 100. In between Street Sheet duties, Foster helps out any way he can by sweeping up, answering phones, greeting visitors, whatever. His colleagues say he’s good at the job. Without a home himself, he can relate to the people stopping by.

Destination of last resort

Andy Anduha, 57, is about to be released back onto the street, four hours after he brought himself to San Francisco General Hospital’s emergency room for a head wound, or painful urination, or both. He’s a little unclear.

The ER is a destination of last resort for homeless people. No insurance, no residence, yes, but for medical care they have this — the hospital that must take them in. It’s a steady clientele.

Now, Anduha waits for a nurse to bring clean underwear from the ER’s collection of donations. He’ll wander off to find housing for the night, likely without success. He typically sleeps on the street in the Mission District, not far from the hospital.

Anduha is a regular visitor to the ER, according to the staff. How do they define a regular? “Honestly,” one nurse says, “if they’re here more than me.”

Sweeping up, sweeping out

David Martinez (video above) has been on the streets for more than a decade. It’s one thing to be moved every time he tries to set up a camp, he says, but what’s worse is always being so vulnerable. Someone tried to set his tent on fire recently, he says, pointing to a burn mark on the sidewalk. “It’s the second time it’s happened to me,” he says.

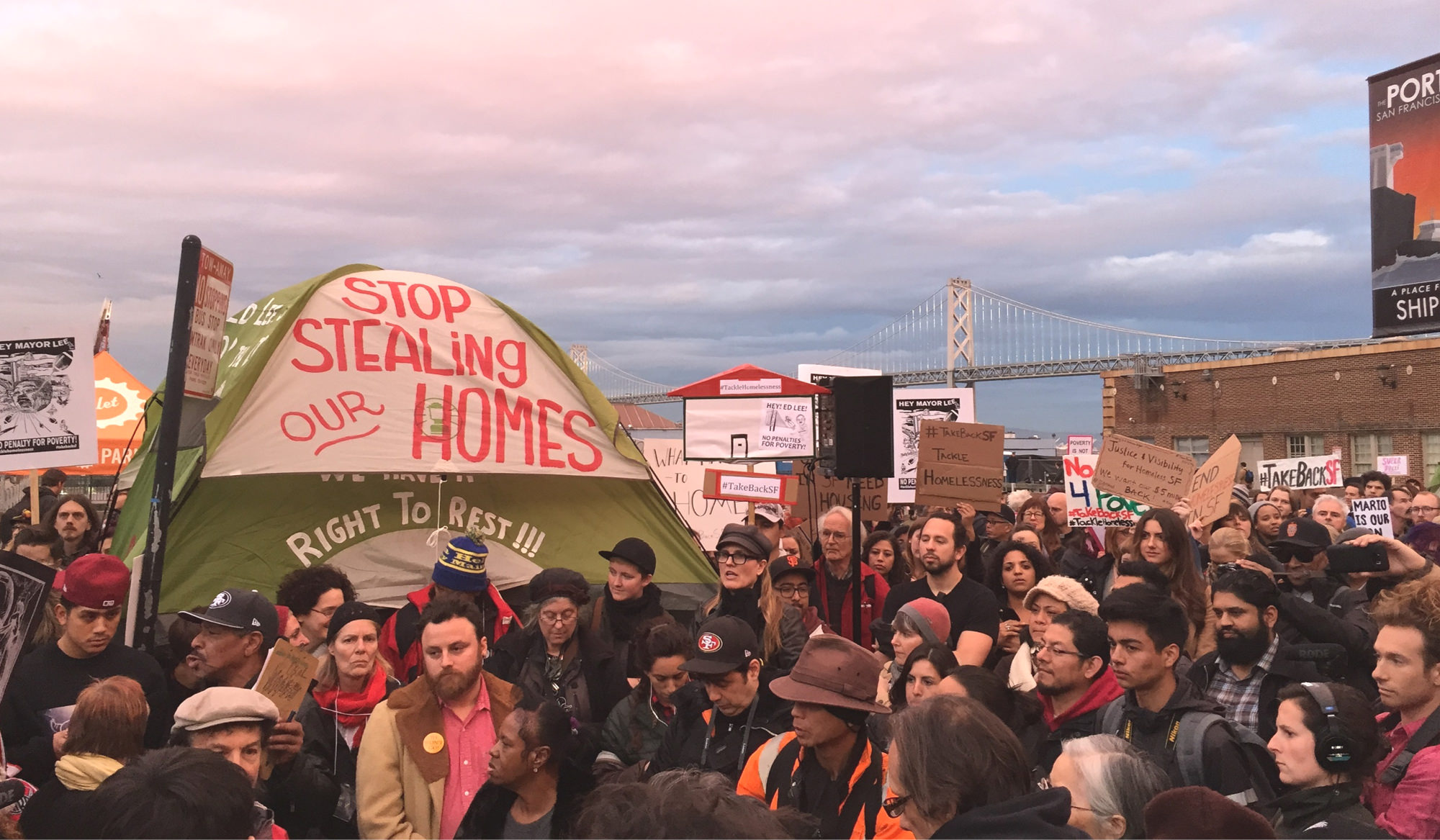

Concern over huge tent camps reached a peak when San Francisco hosted the 2016 Super Bowl and a shocked nation was introduced to the city’s biggest-ever sprawl — 350 people camped along Division Street. There’s been a crackdown ever since, and though city leaders say they’re mostly trying to move people indoors where it’s safer, advocates say trashing tents is cruel.

Martinez, 52, says he wants to move inside, but got kicked out of a Navigation Center after a counselor accused him of shooting heroin inside. He tells the cops clearing his camp he wants another chance, that he’s trying to stay clean.

781st in line for a bed

It’s like loading up for a hike. Filling plastic bags with toiletries, stocking up on energy bars. This is the morning ritual for Tommy Le and his fellow street counselors.

They’re on the San Francisco Homeless Outreach Team, or HOT team, and their job is to find as many street people as they can — dozens of them on a typical day — either taking them to shelters or chipping away at their reluctance, day after day, making them think about leaving the street.

Right away, they find Manuel Rochin on the stoop of a mint-colored Victorian in the Mission. A black backpack and a blue shopping bag stuffed with clothes are at his feet. This is where he feels safest.

“In this space, I don’t come across people who fight like in other places,” he tells the team in Spanish. “I don’t like violence.”

The 46-year-old Mexican immigrant became homeless less than two months earlier after leaving Bakersfield. He was picking pistachios there, but found he couldn’t get the kind of HIV treatment he’d been getting in San Francisco before he headed south for the job. So he came back.

Rochin is 781st in line for a 90-day bed at one of the city’s shelters. Bilingual outreach specialist Veronica Marin asks Rochin if he wants temporary shelter as he waits.

The team consults its housing coordinator, who scores Rochin a bed at the Multi-Service Center South shelter on Fifth Street. He is told to report to the shelter no later than 7 p.m. The team rolls on.

Unmoored, but tethered to GPS

As Faustina Alvarado Garcia walks downtown with her 11-year-old daughter, Madelin, she limps. Her GPS ankle monitor, issued by U.S. immigration agents, is tight and rubbing her skin red.

Garcia, 42, has just spent an hour sharing her circumstances with a case manager from Hamilton Families tasked with helping her find a home. She and Madelin, she says, fled Honduras in January after her brother was killed in a gang shooting and the killers told her family members they were next.

It took them two months to reach America on foot and by bus, through Mexico and across the border at a remote California crossing. Swiftly picked up by immigration authorities, the pair requested asylum and were released before making their way to San Francisco.

They lived briefly with Garcia’s sister before the landlord, citing occupancy limits, told them to leave. So now they are in an emergency shelter, sharing a bunk bed in a room with other families.

Homeless in a strange land, they are bombarded by contrasting images of wealth and despair — glitzy gowns in a department store window fronted by drug-addled, agitated vagrants on the sidewalk. Madelin stares at a woman carrying a box with a picture of an Apple monitor.

“Is that a television?” the girl asks. “Or is it a computer?”

Her mom doesn’t know. They debate what the item is as they trudge back to their shelter in the Tenderloin and another appointment with another case worker.

“I want one of those,” Madelin says.

“One day, when I can, I will buy you one.”

Feeding bodies, including pregnant ones

As lunch service begins at Glide Church, Curtis McGregor, 52, emerges from the kitchen and leans against a dining room pillar. Having supervised the prep, he’s now the maitre d’ for a meal in which roughly half the guests are homeless.

The room holds 60 and he must make sure diners in the first group have eaten and left before new folks take their place. If trouble breaks out, McGregor is often the first to spot it. He knows trouble because he was trouble when he first walked into Glide as a 14-year-old street tough from the Fillmore.

The Rev. Cecil Williams, Glide’s longtime pastor, told McGregor to come back when he was ready to accept a hand up — and that’s what he did, after he’d been to jail for selling crack.

“I could never have imagined in a million years that I would be down here working, giving back to the public,” he says.

Most people move on the second they are finished eating, but not Priscilla Rogers, 23. She is here, she says, “mainly because I’m pregnant.”

Rogers is not yet showing, but has gained 8 pounds because her doctor at San Francisco General told her to eat three meals a day. So she waits in line three times at Glide before lying down along Ellis Street. At 4 feet 11 and 111 pounds, Rogers can find a nook to curl up into, but she never gets more than three hours of sleep. Now, she’s heading off to the library to read books and listen to music until dinner time.

“I’m always moving,” she says.

A mother’s credo: ‘No me importa’

Eleven-year-old Madelin is hungry, but Faustina Alvarado Garcia has little money. So she and her daughter head to the Mexican restaurant next door to their family shelter.

“It’s cheap here,” the asylum-seeker from Honduras says, before ordering a carne asada taco for $2.99 and then counting nickels, dimes and quarters on a table, making sure she has bus fare to get to her sister’s home.

When the food comes, she yields a rare smile. “They gave us free chips,” she says.

They walk back into the shelter. They’re one day shy of the two-month limit for their emergency bed, and are supposed to leave tomorrow — a looming dilemma complicated by the fact that Madelin is a student, and studying is harder with less stability. But for today, they still have a roof. And now, lunch.

Madelin eats while Garcia charges her ICE ankle monitor, rubbing the sore spots under it. She sneaks a few chips, but otherwise doesn’t eat.

“No me importa,” she says. It doesn’t matter to me.

One way off the streets

There’s something up a tree on Willow Street, tucked among the leafy branches swaying in the breeze.

Sgt. Davin Cole peers up and is not surprised by what he sees: a homeless man who’s fashioned himself an unusual sleep situation, a hammock 15 feet up from the sidewalk in the alleyway.

“Hello?” Cole shouts repeatedly. Nothing. He shakes a branch. Nothing. The man in the white cocoon is either in a deep slumber or dead.

Cole pulls his SUV up and sounds the air horn. The man is so startled that he nearly leaps out of the hammock to flee.

“I’m just making sure you’re OK,” the officer tells him. “Don’t jump!”

Turns out, the perch is not only inventive but legal. But Cole likes to check on the man, named Jose Pacheco, from time to time, to make sure he’s OK.

“He’s not blocking the sidewalk. He’s not damaging the tree. He doesn’t have a structure,” he says. “Nothing about it is against the law.”

‘Down on my luck, please spare a buck’

An uneasy trip to Twitter HQ

“We got to go.”

Derelle Foster’s wife, Diana Cisnero, urges her family out of their shelter room and onto the Tenderloin streets, loading daughters Sandra and Ellarose into a double stroller and grabbing 3-year-old Juston by the hand.

Foster has taken the afternoon off work for an important appointment: an autism evaluation for Juston.

Cisnero, 22, steers her carriage past residential hotels, discarded needles, corner stores and what appears to be a bag of human feces. The family’s German shepherd helps carve a path through the crowds. Soon, they’re at the social services clinic — located in Twitter’s Market Street headquarters.

As people pass by with expensive cups of Blue Bottle coffee, the family heads up the elevator, hoping to get a grasp on at least one of the issues before them.

A bed and a new chance

There’s no booze here to drag Jacqueline Gonzalez down. No one waiting to beat her up on the sidewalk while she tries to sleep.

Unlike the usual spartan digs that come with an emergency bed, fountains bubble at the Bayshore Navigation Center, one of the city’s six multi-service shelters that offer intensive housing and counseling aid. Planters contain flowers as well as kale, mint, butter lettuce, radishes. Residents come and go 24-7, smoke and talk about life on the streets: shelters, rehab, case workers, doctor visits.

Mostly they talk about finding housing, and how this is one of the best places to get it. About half of the 4,500-plus people who have come through nav centers since 2015 have found a place to live.

Gonzales, 49, has been homeless on and off since her mom kicked her out of their Daly City home as a teen. But inside this place for the past two months, Gonzalez says, she is the best she has been in years. She goes to bed early, attends recovery meetings, scours the internet for housing. For the first time in years she is dealing with her health; a day earlier she went to the eye doctor.

“I want to stay here until I get my place,” she says. “I’m safe here. I sleep better here. I think better. I can take a shower. I can go to the dentist. I can look for a job. When I am out there on the street I start drinking, drinking, drinking. And my problems get real bad.”

‘Frequent flyers’

Lucinda Blue, 50, comes through the ER doors by ambulance. She forgot to take her insulin before going to bed, and when she got up in the middle of the night, she was woozy, stumbled and fell, breaking her shoulder. It’s her second fall this year; she broke her thumb in February.

Blue lives at Hope House, a transitional housing residence in the Bayview — crucial step-up housing between the street and a permanent apartment. She’s a “frequent flyer” in San Francisco’s network of emergency departments: someone who’s been to an ER somewhere in the city at least five times in the past 12 months.

But Blue says she doesn’t come as often as some. And she’s right. Just down the hall is a patient who’s been passed out in a bed for most of the day. He’d been to a San Francisco emergency room 43 times in the previous year.

Waiting for nothing

‘I don’t really feel like I have a home’

Ignacio “Navi” Vargas’ phone rings as he waits for a Muni train outside UCSF’s Parnassus campus. He answers and bursts into a smile.

“Yes, I’m free Tuesday,” he says.

Vargas had been waiting for this call since he arrived in San Francisco nearly two years ago. Finally, he has an appointment with a therapist.

“I really think I’m sad, mentally,” the 22-year-old says. “My person has been through a lot. I drank alone until I blacked out.”

When he was 17, his mother ordered him to leave their Sierra foothills home after she learned he is gay.

“If I come back from work and you’re still here, I’m calling the cops,” she said, in Vargas’ recollection.

His mother, a Mexican immigrant who works in the fields picking tomatoes and melons, had begun suspecting he was gay when Vargas joined his high school cheerleading squad and began experimenting with makeup.

After brief stays in Los Angeles, Seattle and Oregon, Vargas moved to LGBT-friendly San Francisco when he was 19. He lived in a homeless shelter for seven months before landing a transitional homeless housing unit at Larkin Street Youth Services two months ago.

“I still have my stuff packed up just in case anyone locks me out,” he says. “I don’t really feel like I have a home.”

A moment’s rest on the Mission bus

Bureaucracy and a bed check

Jeff Kositsky, the city’s homeless chief, takes a stroll outside to check on the HOT team’s Tenderloin operation, then heads back inside for a staff meeting about new policies coming from the Board of Supervisors.

Throughout the day, he’s been lamenting that the latest homeless count is up 17% since 2017. He’s frustrated that for every homeless person who gets housed, three more wind up in the street. But he sees hope in the city’s vast, and growing, supportive housing network, which keeps 9,500 people from falling into homelessness.

“It’s not like we’re not doing anything,” he says.

It’s a refrain he repeats over and over to those who say the city is falling short. And hanging with the HOT team, seeing its work, can offer a measure of relief compared with wrestling with thorny policy issues.

The contrast of street life and municipal bureaucracy can be jarring, but it’s at the heart of Kositsky’s job. The staff meeting drags on past 5:40 p.m., with people rubbing their eyes, when his phone lights up.

This time it’s not the mayor — who has by now contacted him a half-dozen times throughout the day with observations and requests. It’s a HOT team member who wants to know if there are any Navigation Center beds available for a homeless person he just met in the Tenderloin.

“Do we have any beds available?” Kositsky asks his staff.

Everyone in the room shakes a head. All of the Navigation Center beds in the city are full.

Revolving door at SF General

Charging up at Starbucks

‘I’m not asking for a mansion’

Larry Tolliver stands in line to get into the waiting area at the huge Multi-Service Center South shelter on Fifth Street. He and 69 others hope someone doesn’t show up to claim a bed, creating an opening for the night.

Tolliver is here because he had no home to return to after his shift as a maintenance worker at Clementina Towers, an affordable housing building. It’s been years since he lost the last home he had, an apartment in the Bayview, and he’s bounced around the city’s shelter system ever since.

He found an affordable single-room unit in Oakland early this year for $695 a month, but was turned away because of his bad credit.

“I just need a break,” he says. “I’m not asking for a mansion or anything. How about just a nice room, a place I can call home?”

Inside, Isabel Blanco has a bed, but also some bad luck. Her partner has been in the hospital since January, recovering from a car accident that broke her back and neck. Now strapped for cash after a series of misfortunes, Blanco is stuck in shelters while she waits for her partner to recover.

“I just lost all my savings, and that’s how I ended up here,” she says. “I’m out of money. Where do I go? Is there someone that can help me? What can I do with all my luggage? Am I really going to pull four suitcases over the street? So many questions.”

Inside, as she prepares to open the St. Vincent de Paul Society-run shelter, Director Lessie Benedith is clear-eyed about limitations. Not everyone who needs a bed will get one.

Northern California’s biggest shelter has 340 slots, but every night there is a citywide waiting list of more than 1,000 people. Benedith gestures to a sparsely furnished waiting area — dubbed “the chairs” — where up to 70 people at a time wait on a chance at a bed they may not get.

“It’s unfortunate that they have to remain in the chairs,” she says. But she adds: “We will not ask them to leave.”

Hungry, tired, but inside

For Derelle Foster, the plate of jambalaya over rice with green beans is a welcome way to end the day. He sits with his wife and three children in a booth in the dining room of their homeless shelter, their German shepherd waiting for scraps. The small cafeteria begins to fill up — couples and other families with kids.

“It’s like hot dogs,” Foster tells 3-year-old Juston, trying to get his son to eat chunks of sausage in the stew.

Foster is hungry and tired. And there is a lot on his mind. Will his son be diagnosed with autism? Will his family find a more permanent place to stay in three months, when they might have to leave the shelter? Will he make enough money to afford a move? None of that will be solved today.

“Let’s go,” his wife says. “Everyone needs to take a shower tonight.”

Anguish out in the open

‘How can you not give a guy like that some money?’

Shorty’s broke again. Time to panhandle. He needs to buy yet another cord for charging his phone, a cup of coffee and enough meth to get him through the night. The throngs of evening tourists coursing past the Ferry Building are a promising target.

A friend rolls Shorty in his wheelchair to the north edge of the building, and he starts his spiel — layering charm into the natural sympathy that comes from seeing a tiny, disabled person in a wheelchair.

Shorty calls out cheerily: “Hi!” Some stare straight ahead. Some shoot looks of revulsion. A few drop cash into the Starbucks cup he holds next to a cardboard sign reading, “Down on my luck, please spare a buck.” He’d considered “Need a hand up, I’m a little short,” but thought people wouldn’t get his grim humor.

Tourist Stu Allen, 33, of Denver, tosses $5 in the cup. “How can you not give a guy like that some money?” he says. He points at the skyscrapers across the street. “People who have utterly nothing when you’re standing around this? It’s one of the worst things in the country.”

In 45 minutes, Shorty has $17. He doesn’t like begging. “I was always taught to never let ‘em see you sweat, and that helps me stay positive out here,” he says. “And I need that. I’ve had guns put to my head out here, had my jaw broken because I wouldn’t give a guy $10, fell out of my chair and broke my leg earlier this year, but I always got a smile on my face.”

‘I don’t like it when people are afraid of me’

Chow time for the van vets.

Hot soup and thick Japanese noodles are the reward at the end of a long day for Jimmie Wu and his fellow vet-students. They’ve spent the day tinkering with their vans in a Home Depot parking lot, they’re hungry, and it’s time for their weekly dinner together.

Sometimes the group aims Wu’s film projector at Mark Chopot’s white truck — the side without graffiti — and enjoys a cheap night at the movies. But tonight, as a cold, wet fog blankets City College and the sun sinks, they’re opting for a nearby udon joint.

Nobody leaves the vans for the restaurant, though, until everyone has parked — no small feat. Street parking is tough until 9 p.m., when classes let out. And homeless students like Wu, Chopot and John aren’t allowed to park overnight in the college lots — a situation that could change if a bill in the Legislature, AB302, becomes law.

Wu pulls into a spot in front of CCSF. Soon, John and Mariel join him. They hear Chopot’s voice calling through the wind and fog, urging them to go eat without him. “I gotta park, dude!” Chopot eventually emerges from the darkness, and all head to the udon eatery.

Dinner chat is about their day-to-day: How it helps to be small when you live in a vehicle. How mold creeps in when you cook in your van. How they miss their friends, other homeless student veterans away on summer travels. And, of course, how the proposed homeless-student parking law would help.

“I understand why the school might not want it,” Wu shrugs. “But it’s good for us.”

Readying for bed at the family shelter

Warding off the night chill

High priority, still no roof

“Shorty’s the boss, and he’s still here, so we are too,” Elias Cook dePena says, pushing Shorty’s wheelchair to the center of the narrow Embarcadero Plaza.

Their homeless pals have shown up with Chinese food, baloney and more that they either bought with panhandled cash or accepted from kind passersby. They’re trying to chow down fast because soon the park police will come and start shooing them away for the street cleaners.

The health care aide who was supposed to fetch Shorty to take him for a shower the previous week never showed up, so he’s been picking at his itchy, sweaty body. His hands are crusted with grime. He eats with them, having no other choice.

City outreach workers have Shorty on a high-priority list for a permanent supportive housing room. But they say he can be hard to find for necessary appointments since he hasn’t gone into a shelter — he prefers the safety and familiarity of his Embarcadero band. It can take up to two years of steady engagement by counselors for many chronically homeless people like Shorty to finally get pulled inside.

“I’m stuck, but I’m really ready to go inside,” Shorty insists.

“Shorty is a doll, super nice,” Kristie Fairchild, head of the North Beach Citizens homeless aid center, says later. She’d been setting up aid and housing appointments for Shorty in conjunction with intensive efforts by the HOT team. “We had one place all set up last fall, but when the van showed up, one of his friends said, ‘Shorty, don’t go, we’ll take care of you.’ So he didn’t.”

Shorty gets a disability check of several hundred dollars a month, and some of his friends on the street exploit it to buy drugs. Overall, members of the group are caring, pushing him everywhere and keeping him safe — but street life is never really safe.

Fairchild sighs: “I’m just hoping everything gets aligned for him. He really needs to not be on the street.”

Desperation station

Methodically walking through each railcar, BART police Sgt. Nick Mavrakis and Officer Youn Seraypheap remind everyone aboard that this will be the end of the line — literally. The train is headed to San Francisco International Airport from Powell Street, with no train returning to the city.

The officers are looking for homeless people. They find one in DeShawn Evans, who is sprawled across the seats.

“You gotta get up, sir,” Mavrakis says. “You can’t take up two seats. Sit up, please.”

Evans, 24, slowly rises. When the cops leave, he slumps back down.

Seats all around him have been flipped over onto the floor of the train. As they are every night.

“People looking for stuff,” Evans explains. “People look for credit cards, money, dope. Anything. Anything anybody drops.”

Evans moved to San Francisco from Louisiana six years ago to take nursing classes at City College, he says, but lost his housing when he broke up with his girlfriend. He’s been homeless ever since. He hasn’t talked to family in almost that long. He rides BART most of the day.

“Nothing better to do,” he says. “It’s warm. And it’s safer. There’s people around. They’re not going to let somebody random just come up to you and start taking your s— and walk away.”

Last call on the Embarcadero

“OK, guys, sorry, but it’s time to go.”

That’s the order from a city park ranger who’s approached Shorty and his friends on the Embarcadero. Street cleaners are on their way.

“You need the HOT team, Shorty?” the ranger asks. Shorty shakes his head.

At the end of the plaza, one woman screeches, “F— you, pigs!” before stumbling away. Most pack up quietly.

“It’s all right, (the cleaners) gotta do what they gotta do,” Shorty tells the ranger, while Zito rolls him to a spot along the bay.

“We’re not sleepers anyway,” Zito says. “We’re nappers.”

Zito tucks a satin comforter around Shorty and fires up a “torch.” Cooking the residue in his meth pipe, he gives Shorty a hit. It doesn’t get either one high, just cuts the jitters.

Shorty tips his head back to face the blinking stars and closes his eyes.

The bus back to the beginning

“C’mon, it’s time to go, sir. C’mon now.”

The No. 292 SamTrans bus is at its last stop, in downtown San Francisco at the foot of the $1.1 billion Salesforce Tower. DeShawn Evans, who’d ridden BART’s last train to the airport, now lies across four seats in the last row of the bus, unresponsive to driver Kim Herbert’s pleas to leave. He’s been there since being shooed onto the bus by airport cops.

Herbert reaches behind her seat, pulls out a 12-inch-long piece of wood as thick as a chair leg, and starts banging on the bus’ metal poles. Evans doesn’t budge.

“OK,” Herbert says. “I’ve got to call the police.” She flags down officers on the street and they come on board.

“The bus driver asked you to get off,” one says, “so it’s time to get off.”

Evans sits up petulantly, stomps off the bus and walks a half block up Fremont Street, where he curls up in a doorway next to a parking garage for the Salesforce West building. Less than 10 minutes later, a flashlight is pointed his way.

Evans jabs his leg at the private security guard’s shin.

“Don’t you kick me!” the guard says, and calls the cops. Fifteen minutes later, two officers show up.

“Sir, it’s the Police Department. Wake up.” Nothing. “Sir, if you don’t sit up on your own we’re going to grab you.”

Suddenly, Evans begins demanding they call an ambulance. “Call the f— ambulance, what the f—?” he says.

He stands up, cursing the cops and spitting at them. He moves off toward Powell Street BART Station. He’ll wait for it to open at 5 a.m. so he can get on a train and go back to sleep.

The guard watches him leave. “It’s like this every night.”

‘Something to be proud of’

Washing away another day

Behind the Ferry Building in the near-silence just before dawn, Shorty snores. Tucked into his wheelchair beneath a blanket, a chilly breeze makes his face twitch as he sleeps.

Across the street, a city cleaning crew begins blasting the homeless colony’s palm-tree plaza with power washers. The mounds of garbage Shorty and his friends have left behind — paper plates, bottles, soggy clothing, a broken meth pipe and more — are blown into a giant truck vacuum cleaner, leaving the pavement shiny and clean.

“It’s like a Band-Aid,” says the worker manning the truck, sighing. “We try hard, but every morning it’s the same mess.”

As 5 a.m. ticks over, the crews finish. The truck rumbles off.

Shorty wakes up, rolls over to the palm trees with his pal Zito. They sit alone, waiting for their small society to filter back for hanging out, copping dope, eating, sleeping — their cycle of daily desperation.

The hosed pavement smells fresh. Like after a rain.

After Derelle Foster’s temporary job at the homeless coalition ended, he started a job-training program in hopes of finding long-term employment. He and his family remain in the shelter, and his son Juston’s autism evaluation is still not completed.

Faustina Alvarado Garcia was granted an extended stay in her family shelter. She’s still seeking asylum.

Shorty was placed in a supportive housing complex in late June by the HOT team, and he now uses a motorized wheelchair instead of the battered manual one he had on the street. He says he’s working to battle his addictions.

Bay Area homelessness: 89 answers to your questions

SF Homeless Project

Letter from the editor: Everything you need to know

Lead writer

Kevin Fagan

Kurtis Alexander Erin Allday Nanette Asimov J.K. Dineen Dominic Fracassa Matthias Gafni Joe Garofoli Justin Phillips Sarah Ravani Tatiana Sanchez Evan Sernoffsky Rachel Swan Otis Taylor Trisha Thadani Jill Tucker Sam Whiting

Demian Bulwa

Copy Editors

Geoff Link Warren Pederson

Data Editor

Emily Fancher

Todd Trumbull

Illustrations

John Blanchard

Music and Video Design

Daymond Gascon

Director of Photography

Nicole Frugé

Video and Multimedia Editor

Photography and Videography

Lacy Atkins Noah Berger Paul Chinn Jessica Christian Preston Gannaway Carlos Avila Gonzalez Liz Hafalia Yalonda M. James Stephen Lam Gabrielle Lurie Santiago Mejia Josie Norris Amy Osborne Nick Otto Scott Strazzante Lea Suzuki Manjula Varghese

Audio Producers

King Kaufman Libby Coleman

Art Director and Project Manager

Danielle Mollette-Parks

Executive Producer, Digital

Brittany Schell

Newsroom Developers

Audrey DeBruine Erica Yee Evan Wagstaff

Managing Editor, Enterprise

Michael Gray

Managing Editor, Digital

Tim O'Rourke

Editor In Chief

Audrey Cooper

Holo by Blue Dot Sessions

Data Sources

San Francisco Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, Veterans Administration, Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development, San Francisco Public Health Department, 2019 San Francisco Point in Time Count Report, San Francisco Mayor’s Budget, San Francisco Unified School District, Glide Church, Rent Jungle, San Francisco Healthy Streets Operation Center, Chronicle research

6 of San Francisco’s most common homelessness questions, answered: Ask The Standard

- Copy link to this article

Ask The Standard tackles the widely held questions about homelessness in San Francisco: What neighborhoods in San Francisco have the most homeless people?

The 2022 Point-in-Time Count found that more than 7,750 people were homeless in San Francisco and that nearly half—3,848—lived in the supervisorial district that contained the Tenderloin. (The boundaries of the supervisor districts changed last April, after the survey was done.)

The district with the second-most homeless people, with 1,115 unhoused residents, contained the Bayview, Potrero Hill and parts of the Outer Mission.

There are far fewer homeless people living in the city’s western neighborhoods. The districts that contained the Sunset, Richmond and Lake Merced neighborhoods had a total of 465 homeless people, just 6% of the city’s total.

How Much Money Does San Francisco Spend on Homelessness?

The city’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing had a budget of $672 million in fiscal year 2023, which ends June 30. More than 60% of the money pays for housing, while 20% goes to shelter and the rest is for prevention, outreach and staffing.

But those aren’t the only funds the city spends on homelessness. Other departments—including the Department of Emergency Management, the fire department, the police department, the Department of Public Health and the Human Services Agency—also put some of their resources into homeless services by responding to street crises, clearing encampments, doing street outreach and providing financial assistance.

Who Is Homeless in San Francisco?

Of the estimated 7,754 homeless people in the city, around 1,100 are under 18, and about 600 are veterans, according to the 2022 Point-in-Time Count . Around 35% of them have been homeless for at least a year or have repeatedly found themselves without housing.

Black people—who are only 6% of the city’s population—account for 38% of unhoused residents. By contrast, white people make up more than half of the general population but are only 43% of the city’s homeless population. Asian people account for 37% of San Francisco residents but are only 6% of homeless people. In a separate question on ethnicity, the survey found that nearly a third of homeless San Franciscans identified as Hispanic or Latino.

Most of the homeless population is male—62%—while 34% is female, 3% is transgender and 1% identify as gender nonconforming.

A substantial portion has found themselves without a home later in life. About a quarter of the city’s homeless population is over the age of 51, while around 20% are between 18 and 24.

Which Homeless People Get Housing in San Francisco?

In deciding who receives housing or other help, the city considers factors such as income or whether the person is caring for children, has a substance use disorder, criminal records or a history of trauma.

Unhoused individuals answer a survey about their histories, what barriers to housing they’ve faced and what might happen to them if they were left to live on the streets.

Some have criticized the process as confusing, slow and unreliable because it relies on self-reported data. The Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing is working on revising the process based on the recommendations of a working group.

Access to shelters can be similarly difficult, as people are usually only admitted through the city’s encampment resolution process , which responds to homeless encampments on an ad hoc basis—often due to complaints from neighbors—and ostensibly offers the occupants shelter.

How Many People Live in City-Owned Housing and Shelters?

The city currently provides 12,413 units of permanent supportive housing and housing vouchers for formerly homeless people, but 825 of those units sit vacant, according to the most recent report .

The city has struggled to move people into vacant rooms because the units are either in disrepair or because of issues with the San Francisco Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing’s prioritization system. The department says it is streamlining the process of moving people into available units.

Many of the city’s permanent supportive housing units, considered to be the city’s most dignified form of public housing, are located in the Tenderloin, SoMa and Lower Nob Hill neighborhoods. But many of the older permanent supportive-housing buildings have had their issues, with clients complaining about rodent infestations, broken elevators that sometimes trap people in their rooms and a lack of services to address widespread drug use and mental illness.

The city also owns 3,169 shelter beds that it keeps at 90% occupancy to make room for emergency admissions from hospitals and jails.

The types of shelter range from vehicle and tent sites to tiny homes and warehouse-style facilities with hundreds of beds within a relatively confined space.

Navigation centers, a special type of temporary shelter, are aimed at eventually transitioning guests into permanent housing.

Motivated by the pandemic, and under the promise of state and federal reimbursements, the city began leasing privately owned hotels to shelter those living on the streets in April 2020. At the peak of the program, the city provided 2,288 rooms in 25 hotels. But the program wound down, and it ultimately cost the city tens of millions of dollars in property damage claims. However, many advocates argued that the program was a success because it helped 1,667 people transition into permanent housing, and some groups are now urging the city to lease more hotels .

How Many People Are Homeless in San Francisco?

On any given night, about 3,400 people are sleeping in San Francisco’s homeless shelters, while about 4,400 sleep on the city’s streets, according to the city’s most recent one-night count conducted in February 2022. That's a total of nearly 7,800.

The data is collected every other year as part of the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing’s Point-in-Time Count , which is required in order for the department to receive funding from the federal government.

The count is conducted by a group of people who travel every block of the city on a single night counting those who appear to be homeless. The one-night tally is the primary source of data about the size of the city’s homeless population. The city later follows up with interviews to get a better idea of the demographic breakdown and backstories of homeless people in San Francisco.

According to the count, overall homelessness decreased by 3.5% since 2019, though it’s still 13% higher than it was in 2017. Historical data shows that the number of homeless people peaked in 2002, with about 8,600 people living on the city’s streets or in shelters, which is 11% higher than today’s numbers.

The city estimates that more than 20,000 individuals experience homelessness locally over the course of a year, many of them for brief periods.

David Sjostedt can be reached at [email protected]

Filed Under

Coalition on Homelessness

The Coalition on Homelessness organizes homeless people and front line service providers to create permanent solutions to homelessness, while working to protect the human rights of those forced to remain on the streets.

- Keeping thousands of San Franciscans housed and housing thousands of San Franciscans

- Halting the citing, arresting, and confiscation of property of people whose only crime was being too poor to afford a place to live

- Cultivating leadership and building community within the city’s homeless population

latest in US News

Virginia woman wins lottery jackpot with first-ever ticket...

WWII veteran, 100, finally receives college diploma nearly 60...

Florida teens face felony charges after being caught dumping...

Newly surfaced video shows moment Jets cornerback loses control...

US, Australian surfers were likely executed in vicious carjacking...

Man dead after crashing into White House security barrier: police

'SNL' takes aim at Columbia students squandering tuition by...

Utah receives 4,000 hoax complaints after new restrictive...

San francisco ‘doom loop’ canned, but even opposition group’s ‘positive walk’ can’t dodge open drug use, homeless.

- View Author Archive

- Get author RSS feed

Thanks for contacting us. We've received your submission.

The sold-out planned ‘‘doom loop” tour of drug-infested San Francisco was canceled , and community leaders tried to hold a “positive walk” instead — only to still stroll past addicts getting high and homeless camps.

Curious tourists and locals had shelled out $30 a pop on Eventbrite for a weekend tour promising an up-close-and-personal experience with San Francisco , “the model of urban decay” — complete with walks past its “open-air drug markets and vacant office and retail spaces.

But the tour’s guide, only listed as “SF Anonymous Insider,” failed to show at Saturday’s event, claiming he was afraid to carry it out because of all the controversy around it.

“Unfortunately, the substantial media interest means that it is not possible to preserve my anonymity while publicly posting the tour’s time and meeting location,” he wrote in a message to customers, according to the San Francisco Chronicle .

Community activist Del Seymour and others with the nonprofit Code Tenderloin — who had gathered at the tour’s designated starting point to protest the event — then led about 70 people on an nearly 2-mile “anti-doom loop tour” through areas such as City Hall, Union Square, Mid-Market and the Tenderloin District.

One of their stops, the Civic Center district, was eerily empty except for half-baked drug addicts bent over after taking a hit on fentanyl and other drugs.

As the tour group walked past shuttered stores such as the Whole Foods grocery store on Market Street, drug deals were happening in broad daylight.

A homeless man yelled at some in the group as they passed by the encampments.

As Seymour took the group to the Glide Memorial Church and a nightclub called the Power Exchange in the Tenderloin neighborhood, participants passed by rows of tents, many with homeless addicts passed out inside.

In the corners, men exchanged crumpled up money for balls of foil.

Some openly smoked fentanyl and other drugs as the tour group walked past them.

The stench of urine mixed with human and animal feces was at times overwhelming as Seymour quickly walked the group past the notorious corner of Hyde and Turk streets, where drug deals run rampant especially “once the sun goes down,” a local told The Post.

Some of the homeless men and women laying on the street corners looked up in confusion as the tour group walked past them.

Serena, a group member who brought snacks and water in her bag, stopped to give some of the homeless men and a woman some of her food.

The woman, who was passed out on the ground, was so high on drugs that she couldn’t even lift her head to say thank you.

Another man took a long deep breath out of a pipe and blew smoke into the air.

He grabbed one of the snacks Serena offered.

“It’s hard because housing here has turned into a crisis,” Serena told The Post. “It feels like City Hall isn’t listening to the community and this is the fall out of the broken systems that we are seeing.”

During the two-hour tour , Seymour talked about various programs available in the Tenderloin, including subsidized low-income housing where families pay only $400 for a three-bedroom apartment that normally would rent for $5,000 to $8,000 a month.

Seymour also pointed to the various services available to the homeless in the area, including free meals and housing, but also told The Post part of the struggle involves getting those who need help to recognize they need it.

“If I’m unhoused and have mental challenges, you can’t just spend 30 seconds and then walk away after I say no,” he said. “You need to sit down with me and talk to me in a gentlemanly manner. It might take an hour, it may take two, but you have to give me that time and build that trust with me so we can make some sort of compromise.”

As for the “doom loop” tour, the activist said, “I fell out of the chair laughing because of the meanness that people in San Francisco have to even suggest something like this.

“This is not healthy or helpful at all for our people,” he said. “We don’t want to live in the situation we are living in. We want to do something about it, but you can’t do something about it when people beat you down.”

Dany Vallerand said she initially wanted to take the advertised “doom loop” tour because she usually didn’t feel comfortable going through the area on her own.

“I just thought it would be very interesting, and I hoped the money would go to a good cause, like some charity,” she told The Post. “I was hoping to explore the Tenderloin in a way that I normally wouldn’t feel comfortable doing on my own and accompanied by other people with a different point of view.”

Vallerand said that while she was “perfectly happy” to take the anti-doom loop tour instead, she noted the economic downtown of San Francisco has affected many residents such as herself, as flagship businesses have left the area and property value going down.

Vallerand said she recently sold her condo $150,000 below her asking price.

“It is very hard to see it happening here,” she said.

More than 20 businesses, including Nordstrom, Whole Foods and Old Navy, have left the area since January 2022 .

While locals such as Vallerand decided to take the opposition tour, others who signed up for the original “doom loop” version were disappointed they didn’t get what they paid for and left.

But Serena said she decided to participate in the “positive” tour because the initial Eventbrite listing offended her.

“They wanted to showcase the doom of the Tenderloin, and to me, it sounded very f–ked up,” said Serena, who did not want to provide her last name. “I can’t believe it sold out.”

Share this article:

Advertisement

Gala Sponsorships Now Available!

Shop our essentials amazon wish list, executive leadership council, come tour our house.

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Homeless Residents Got One-Way Tickets Out of Town. Many Returned to the Streets.

As cities offer transportation passes to get homeless people to a more stable destination, some worry whether they are sending people to insecurity in a new place.

By Mike Baker

SEATTLE — The solution is cheap and simple: As cities see their homeless populations grow, many are buying one-way bus tickets to send people to a more promising destination, where family or friends can help get them back on their feet.

San Francisco’s “Homeward Bound” program, started more than a decade ago when Gov. Gavin Newsom of California was the city’s mayor, transports hundreds of people a year. Smaller cities around the country — Myrtle Beach, S.C., and Medford, Ore., among them — have recently committed funding to the idea.

And in Seattle this past week, a member of the King County Council proposed a major investment into the region’s busing efforts, fearing that the city was on the receiving end of homeless busing programs from too many other cities.

But do these transport programs actually help people find stable housing? For many of those offered a bus ticket, they do not.

In San Francisco, city officials checking on people in the month after busing them out of town found that while many had found a place to live, others were unreachable, missing, in jail or had already returned to homelessness. Within a year, the city found that one out of every eight bus ticket recipients had returned and sought services in San Francisco once again.