This story is over 5 years old.

So wait, who actually won all those tour de france titles.

ONE EMAIL. ONE STORY. EVERY WEEK. SIGN UP FOR THE VICE NEWSLETTER.

By signing up, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy & to receive electronic communications from Vice Media Group, which may include marketing promotions, advertisements and sponsored content.

2-FOR-1 GA TICKETS WITH OUTSIDE+

Don’t miss Thundercat, Fleet Foxes, and more at the Outside Festival.

GET TICKETS

BEST WEEK EVER

Try out unlimited access with 7 days of Outside+ for free.

Start Your Free Trial

The Top 10 Biggest Cycling Scandals in Tour de France History

Forget about Lance Armstrong. These ten scandals rocked cycling to its core.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! >","name":"in-content-cta","type":"link"}}'>Download the app .

While the 100th edition of the Tour de France has been blessedly free of scandal so far ( despite insinuations that Team Sky was suspiciously dominant on the mountain stages ), throughout its history La Grande Boucle has had more disgrace and drama than the Kardashians. Although it remains one of the world’s most beautiful sporting events—a grand showcase of athleticism, grit and courage—since its earliest days the Tour has been sullied by epic displays of cheating, stupidity, and generally bad behavior. With that fact in mind, we offer the following short tour of some of Le Tour’s lowest points.

The Biggest TdF Scandals: 1904—The Last Tour

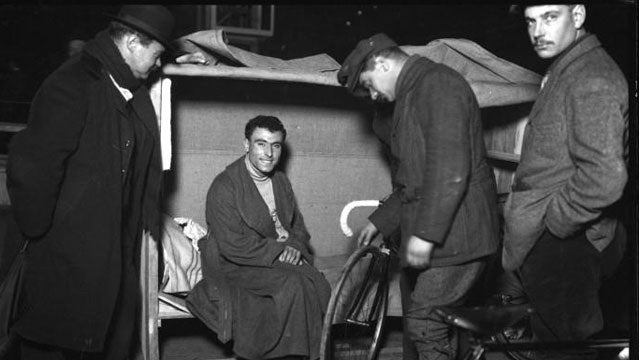

“The Tour de France is finished and I’m afraid its second edition has been the last.” So wrote race founder Henri Desgrange following the conclusion of the scandal-plagued 1904 Tour. During the race, nine riders were disqualified for hopping trains or taking rides in cars and trucks.

Along the route, overexcited fans showed their support for their favorite competitors by beating up their rivals. When the race finally reached Paris, it appeared that inaugural Tour winner Maurice Garin had triumphed again. But after ongoing complaints to the French Cycling Union about cheating, the top four finishers were all disqualified, making Garin the first Tour winner to be stripped of his title.

In the modern era, three cyclists have been stripped of their titles post-race: Americans Lance Armstrong and Floyd Landis, and Spaniard Alberto Contador. All had their victories revoked for doping violations.

The Biggest TdF Scandals: 1910—The Assassins

Today, a Tour de France without brutal climbs snaking over snow-capped peaks would be unthinkable. However, in 1910, when Tour organizers announced the race route would include the Pyrenees, more than two dozen cyclists withdrew from the starting list in protest of what the considered a dangerous stunt.

Stage 10 of that year’s Tour included ascents of the Tourmalet and the Col d’Aubisque. Only one rider, Gustave Garrigou, was able to conquer the Tourmalet without dismounting his bike (for which he received a prize of 100 francs). At the top of the Aubisque, eventual overall winner Octave Lapize shouted, “Assassins!” as he rode by race organizers, who’d driven to the top to watch the suffering cyclists from the safety of a car.

The Biggest TdF Scandals: 1966—The First Drug Tests

Widespread use of performance enhancing drugs was common since the first days of the Tour de France. In an effort to control drug use in sport, France passed a national anti-doping law in 1965 and introduced drug testing at the 1966 Tour. The first doping control was carried out following the eighth stage, with several riders being ordered to submit to testing.

Among those told to provide a urine sample and submit to an examination by doctors was French hero Raymond Poulidor. The following day, the entire peloton protested the tests by walking their bikes for the first part of the ninth stage in Bordeaux while shouting, “No to pissing in test tubes!”

The Biggest TdF Scandals: 1967—The Death of Tom Simpson

In 1962, Tom Simpson made history as the first British racer to don the yellow jersey as the Tour’s overall leader. He lost it the next day, but the feat signaled he was a rider to watch. Indeed, more success followed, including victory at the 1965 World Road Race Championships, stage wins at the Vuelta a Espana, and the overall at Paris-Nice.

In 1967, Simpson entered the Tour hoping for a podium finish and to wear yellow for a portion of the race. He started well but unfortunately got sick as the race passed through the Alps. By stage 13, weakened and unwell, Simpson was determined to fight on. That day’s route went over the infamous Mont Ventoux, the feared “Giant of Provence,” a hellish climb snaking over barren, moonscape-like slopes to a brutally exposed summit. Simpson hit the Ventoux with the leading group but then fell off the pace, slipping back though the shattered field of riders.

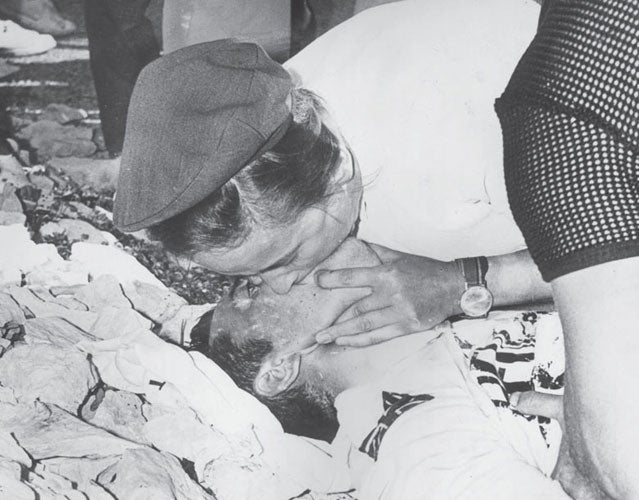

Soon he started zigzagging erratically across the narrow road. A kilometer from the summit, he toppled over. Helped back on his bike he road another few hundred meters before again nearly crashing. Caught and held upright by spectators, Simpson was now unconscious, still sitting on his bike gripping the handlebars. The Tour’s medical staff was unable to revive him and he was airlifted to a hospital in Avignon, where he was pronounced dead.

The official cause of death was heart failure due to dehydration and heat exhaustion. However, traces of amphetamine were found in Simpson’s body and medical officials said the drugs were a contributing factor to his death, as they likely allowed him to push his body too far. A memorial on the Ventoux near where Simpson collapsed is a popular pilgrimage site for cyclists from all over the world.

The Biggest TdF Scandals: 1986—Hinault vs. LeMond

After three weeks of torture, only one man stands on the top step of the podium in Paris as the overall winner of the Tour de France. But no one gets there without the help of teammates. In 1986, Greg LeMond was poised to become the first (and to this day the only official) American champion.

To accomplish that feat, LeMond was counting on the assistance of his French teammate Bernard Hinault, whom LeMond had helped to victory the previous year. Hinault, still a great rider and a five-time winner of the Tour, repeatedly pledged that he and the entire La Vie Claire team were on board to help LeMond. However, Hinault’s actions out on the roads seemed to indicate otherwise. Hinault repeatedly attacked LeMond, forcing the American into the awkward position of chasing down the aggressive Frenchman.

On stage 18 of the ’86 Tour, one of the most memorable stages in history, with LeMond already wearing the leader’s yellow jersey, the putative teammates went mano-a-mano up the switchbacks of the legendary climb to L’Alpe d’Huez. Hinault could not crack LeMond and the two men crossed the finish line side by side. Five days later, LeMond rode into Paris the overall winner. Hinault finished second and then retired from pro racing.

The Biggest TdF Scandals: 1998—The Festina Affair

Forget about the lance armstrong. these ten scandals rocked cycling to its core..

While doping had been an omnipresent seamy underside of the Tour since its first days, the tawdry ugliness of banned performance enhancing drugs exploded into the spotlight on a grand scale in 1998. The scandal known as the Festina Affair began when an employee of the Festina team, Willy Voet, was arrested by police three days before the Tour at the Belgian-French border.

A search of Voet’s car turned up EPO, banned steroids, syringes and other doping-related products and paraphernalia. Eventually, Festina’s team director, team doctor and nine of its riders were all arrested. Under questioning, the doctor, Bruno Roussel, admitted Festina operated a systematic doping operation. French police, suspecting doping wasn’t limited only to Festina, conducted raids on other teams throughout the Tour.

The raids incensed the racers, who felt they were being treated as criminals, and tensions reached a height on stage 17. First, the peloton held a sit-down strike at the start of the stage. Once on the road riders agreed not to race and dawdled along at a slow tempo. Stopping again, riders threatened to withdraw from the race en masse. Finally, they walked across the finish line in Aix-les-Bains and the day’s stage was nullified. By day’s end, French national champion Laurent Jalabert and all of the race’s Spanish teams had quit. Of the 189 starters, just 96 finished in Paris on August 2.

The Biggest TdF Scandals: 2006—Le Tour de Dope

Forget about the doping. these ten scandals rocked cycling to its core..

Seventeen years on from the Festina Affair, if anyone had hoped cycling had made progress regarding its problems with banned substances they were in for a rude awakening. The 2006 Tour de France was bookended with doping scandals.

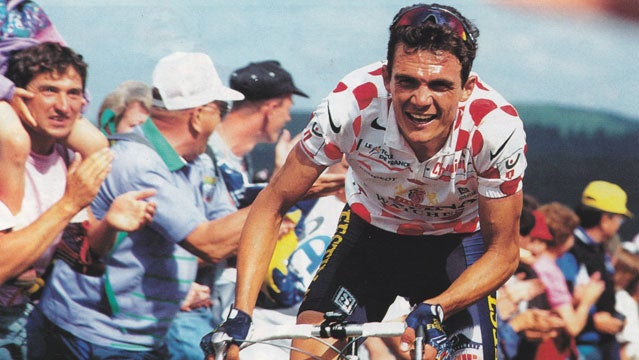

Beginning in May, a Spanish police investigation dubbed Operación Puerto uncovered an alleged massive doping ring involving several top cyclists. Due to the unfolding investigation, on the eve of the Tour’s start in Strasbourg, nine riders with ties to Puerto were kicked off the start list, including the 2005 edition’s 2nd through 5th place finishers: Ivan Basso, Jan Ullrich, Francisco Mancebo, and Alexandre Vinokourov (2005 “winner” Lance Armstrong had retired).

Once underway, the Tour was enthralling, with American Floyd Landis eking out a victory in an excruciatingly tight three-way battle with Spaniard Oscar Pereiro and German Andreas Kloden. Landis wore yellow into Paris, but his victory celebration was short, as four days after the Tour wrapped up it was announced that his urine sample following his epic win on stage 17 had tested positive for banned synthetic testosterone. Landis claimed innocence, but after exhausting the appeals process his title was stripped in September 2007.

The Biggest TdF Scandals: 2007—Firing Michael Rasmussen

Scandal continued to plague the Tour in 2007. During the race, three riders were expelled for doping violations and the entire teams of two of the three offenders left as a result. Then, after winning stage 16, race leader Michael Rasmussen, a Dane riding for the Dutch Rabobank squad, was sacked by his team management for violating team rules.

Rabobank claimed Rasmussen had lied about his whereabouts the month before the Tour started (teams must know where their riders are at all times in case anti-doping officials wish to conduct tests). Rasmussen said that he was training in Mexico, but was spotted by a former cycling pro on the road in Italy instead.

Rasmussen’s removal from the race was unprecedented. The only other Tour leader expelled mid-race—Belgian Michel Pollentier in 1978—was removed for trying to cheat a doping test. Rasmussen is the only leader to have been fired by his own team.

The Biggest TdF Scandals: 2010—Chaingate

On stage 15 of the 2010 Tour, Luxembourger Andy Schleck was riding in the yellow jersey when he attacked a group of his rivals near the summit of the Port de Balès, a high mountain pass in the central Pyrenees. But soon after Schleck darted up the road he came to a dead stop and hopped off his bike. He’d dropped his chain.

While he struggled to get it back on, Schleck’s closest competitor, Alberto Contador, who was trying to mark Schleck’s attack, rode past him in anger with two other riders. Contador looked back a few times to check on Schleck’s progress, but he did not slow down and wait for Schleck. A desperate Schleck tried to reconnect with Contador but failed, eventually losing the yellow jersey at day’s end and never regaining it.

The stage 15 incident will forever go down in history as “chaingate.” The reason for the controversy has to do with the unwritten rules of the road at the Tour de France—in this case the rule that the leader’s closest rivals should not attack him if he has a mechanical issue. The thinking goes that profiting from the leader’s bad luck is dishonorable, and that the battle for the lead should be held on an even playing field.

Never before has this “rule” been put to the test like it was in 2010. Footage of “chaingate” has been dissected as closely as any in history, and opinion remains split to this day on whether Contador should have waited for Schleck to fix the chain and rejoin the group, or since Schleck attacked first, whether Contador was “allowed” to drop him.

The Biggest TdF Scandals: 2011—TV Car Crashes Riders

Anywhere in the world, cars and cyclists can be a dangerous combination. But given that the Tour route is closed to traffic, it’s safe to say that few riders are worried about being toppled off their bikes by some distracted or dangerous driver. But that’s just what happened in 2011, when a car that was part of the official Tour caravan smashed into the day’s breakaway riders on stage 9.

Trying to pass on the left, a car from broadcaster France Télévisions inexplicably bumped rider Juan Antonio Flecha, knocking him violently to the pavement. Riding behind Flecha, Belgian Johnny Hoogerland was vaulted into the air and landed on a barbed wire fence marking a field alongside the road.

Amazingly, Flecha was OK—he remounted his bike and received treatment for a scraped and banged elbow by Tour medical staff. Even more amazingly, Hoogerland was able to finish the stage, despite sustaining deep cuts to his legs that required 33 stitches. Sadly Hoogerland’s bad luck with cars didn’t end there: in February 2013 he collided with a car while training in Spain, fracturing five ribs and injuring his liver and spine.

- Road Biking

Popular on Outside Online

Enjoy coverage of racing, history, food, culture, travel, and tech with access to unlimited digital content from Outside Network's iconic brands.

Healthy Living

- Clean Eating

- Vegetarian Times

- Yoga Journal

- Fly Fishing Film Tour

- National Park Trips

- Warren Miller

- Fastest Known Time

- Trail Runner

- Women's Running

- Bicycle Retailer & Industry News

- FinisherPix

- Outside Events Cycling Series

- Outside Shop

© 2024 Outside Interactive, Inc

If pro cycling is now clean, why do records set by dopers keep on getting broken?

Pro cyclists keep getting faster decade after decade. Can improvements in training and tech take all the credit? Joe Laverick compares past and present

- Sign up to our newsletter Newsletter

Under the microscope

Data driven, old hand, modern peloton, raised pace raises eyebrows, setting new boundaries, has cycling cleaned up its act.

When Jonas Vingegaard crossed the finish line on the Champs-Elysées this summer, he didn’t just take his first ever yellow jersey. He also took the crown for the fastest ever Tour de France. The 25-year old Dane had pedalled his way around France at an average speed of 42.03kph (26.1mph) – beating the record of that guy from Texas. How is it possible that the supposed clean generation are smashing records from the sport’s darkest era?

One side of the argument points to the countless developments of recent years, from aerodynamics to nutrition, training to recovery, hydration to heat control – all of which have made the peloton faster. Following the lead of Team Sky’s marginal gains approach, cycling shifted from settling for “it’s always been done that way” to questioning “why don’t we do it another way instead?” – from training guided by old wives’ tales to performance honed by science from F1 race teams.

The 2022 Tour de France was one of the hottest on record, but that didn’t stop the riders smashing records out of the park. While it is difficult to compare performances across the years, given that each Tour has differing parcours, looking at the outright records overall and on known segments still offers a decent level of comparison. Not only did we witness the fastest ever Tour de France from a GC perspective but the fall of some mythical climbing records too.

Stage 17 of the 2022 Tour de France saw UAE’s Brandon McNulty riding at approximately 6.58W/kg to break Marco Pantani’s 25-year-old record on the Col d’Azet by two and a half minutes. We saw the fastest Alpe d’Huez ascent since 2006, despite the leaders being two minutes down on Pantani’s 1995 record. On top of all that, on stage six to Longwy, the front-runners averaged 49.4kph, making it the fourth fastest road stage ever, and the fastest ever with more than 2,000m of climbing.

With records falling on all terrains, it’s impossible not to wonder how and why. There are of course variables such as temperature and wind – bear in mind Geraint Thomas ’s response when asked why this year’s Tour was so fast: “We’ve had a fair bit of tailwind, to be fair.” Maybe we’re witnessing incremental progress plus natural variations in weather. Then again, we can’t ignore that in the 1990s and early 2000s the peloton was riddled with performance-enhancing drugs. Is it really credible that today’s riders are beating the times of yesterday’s dopers without some secret ingredients of their own?

Over the past two decades, cycling has been placed under a microscope and developed in every way imaginable. There is no doubt that equipment has gone through revolutionary developments, meaning riders go faster without expending more energy. From clothing to bike design to tyre composition to helmet choice, teams with enough cash are buying into improvements that have cost millions in R&D. As for the poorer teams, they have to make do with older, cheaper tech.

“I think the culture in the UK has led the way in aerodynamic development over the past 15 years,” says Matt Bottrill, a former national 10-mile TT champion who works as an aero consultant for Lotto-Soudal . “It’s a lot easier to read data these days, which makes it easier to understand how to get faster.”

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Aside from aerodynamics, which tech improvements have made the biggest difference? “Tires are one of the craziest developments,” says Bottrill. “If I’d had today’s wheel and tire technology in the National 10 that I won [in 2014], I’d have been 30-40 seconds faster – and I won that race with a 17:40.” He explains how wider, tubeless tires run at lower pressures have proved to be a significant breakthrough. On the road bike side, Trek recently announced that its new Madone was 20W faster than the previous edition , let alone a pre-2010 edition.

An industry insider noted: “Early aero bikes handled poorly, but we don’t see that now. A surprising amount of the aerodynamic gains comes from the handlebars.” Some teams are studying the relationship between biomechanics and aerodynamics – how changes in position alter power and drag , to find the best compromise. For example, if dropping your saddle gains you more in aero enhancement than you lose in watts at the pedals, it’s worth doing. More and more, this involves the use of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) which allows teams to validate theories without hands-on testing in a wind tunnel or out in the field.

It’s not just equipment that has changed but training too. Frank Overton is the owner of FasCat Coaching and has coached pro athletes for over 20 years. The US coach believes that development of technology and cycling’s ever increasing professionalism holds the answer to why athletes are getting faster. “Physiologically we’re all human beings and we still improve in the same way; it’s the training methodologies and the use of data that has changed. In the past 10 years we’ve seen the mass adoption of power-based training.” Overton believes that the near-universal uptake of power meters between 2002 and 2012 effected a step change in training precision. “Once coaches began to quantify training load and collect race data, there was a greater understanding of racing’s demands, reflected in the sessions prescribed.”

Fifteen years ago Tyler Hamilton was getting laughed at for doing intervals. There was no structure back then, it was just the old-school methodology of 25-30 hours per week, and then using racing for the intensity,” says the former WorldTour star. “Now, everyone has highly structured and highly-personalised training plans. That increased specificity alone has led to improvements in Tour de France riders.”

The use of the best power meters is just one form of technological progress in cycling. Overton points to mass data collection as another big advance in training intelligence. “Ten years ago each team would have one coach. For example, at Liquigas, all the riders would get the training schedule individualised for Peter Sagan. Now, every rider has their own made-to-measure plan.” How would Overton slice the progress pie in terms of importance? “The reason the peloton has got faster is 70% power-based training, 15% bike technology and 15% cycling nutrition .”

Bahrain-Victorious’s Heinrich Haussler has seen it all: the 38-year-old has had first-hand experience of the past 18 years of progress, having turned pro in 2004. Why does he think the peloton is getting faster? “The sport is more developed than ever before,” he tells me. “There’s more resources, better training techniques and nutrition. The bike is getting more aerodynamic and lighter, and tires are getting faster.”

To anyone living a normal life outside of the pro ranks, the level of monitoring might seem excessive, possibly even intrusive. “These days, everything is completely controlled,” admits Haussler. “At home, I get on the scales every day and then it’s uploaded for someone to see. At a race, the weighing continues and a nutritionist helps make sure you have the exact quantities of carbs and protein you need .” For a pro at the top level, your schedule is never your own. “The number of training camps we do now is crazy,” continues Haussler. “We’re constantly away from home. These days it’s impossible to be competitive at a big race without having trained at altitude first.”

Before this year, the record for the fastest ever Tour de France belonged to Lance Armstrong for his victory in 2005 (since voided). The Texan averaged 41.65kph, while Vingegaard’s new record stands at 42.03kph. Looking at these figures and all of the other records that have been broken, it’s easy to see why this year’s Tour prompted some raised eyebrows.

The only WorldTour rider sanctioned for doping in the past two years was Nairo Quintana, disqualified from his sixth place at the Tour de France after testing positive for Tramado l. The trend would seem to be towards cleaner racing, with far fewer cases of doping compared to the early-2000s. Then again, to indulge in a more pessimistic view, it took a decade for Lance Armstrong’s house of cards to come crashing down.

Asked about doping at this year’s Tour de France, Wout van Aert responded: “We have to pass controls every moment of the year, not only at the Tour de France, also at our homes.”

Of course that’s true, but perhaps he should have been more aware of how such stock phrases can be heard as echoing Armstrong’s empty mantra, “I’ve never failed a test.” Looking back at cycling’s history, it is rare that dopers are caught red-handed. The big scandals – Festina Affair, Operación Puerto, Lance Armstrong and Operation Aderlass – were all exposed by police investigations or whistle-blowers, not anti-doping violations. Just this spring, raids on Portugal’s premier team W52-FC Porto saw 10 riders eventually banned, including last year’s Volta ao Algarve winner João Rodrigues. There is a fine line between hope and belief. It is impossible to know what is going on behind the scenes, and previous generations have shown that riders are often one step ahead of the testers. I for one hope the pro peloton is clean, for everyone’s sake.

It is rare that sport stands still. What once seemed impossible is now possible, as attested by countless examples through history: four minute mile, two hour marathon, or riding the Tour de France at 42kph. Each incremental technological advancement is a small step towards faster performances.

Amateurs simply cannot be expected to do what pros can, but there are many areas where copycatting the best has its benefits. Using modern training technology and data to inform training will make you a better athlete, just as riding a more aerodynamic bike will make you faster. “Amateurs don’t have the time available to recover like the pros can,” Overton reminds us, “but the trickle down technology can help – in fact, it was amateurs who led the way on power- based training first, adopting it before the pros!” It’s a tale as old as time. Every era thinks it’s at the peak of human and technological advancement and then someone or something comes along and redefines what’s possible – we look back and laugh at our naivety. For cycling, the past decade has seen a huge shift, and the sport is barely recognisable from 10-20 years ago.

So, is it believable that today’s generation are, through legal advancements only, smashing records from the sport’s darkest days? Yes, no, maybe. We’d be stupid to ignore the leaps and bounds in progress over the past 10-20 years, which, though difficult to accurately quantify, benefit the modern day racer to the tune of at least 20W in aero gains alone. Mix in the developments in training science and it’s reasonable to believe that today’s top guns are going faster by honest means. Yet we’ve been burnt by giving the benefit of the doubt too many times before.

"No" – Robin Parisotto

“I’m not optimistic that much has changed” A stem cell researcher and antidoping advocate, Parisotto helped to develop the early EPO tests and was one of the founding members of the UCI’s biological passport programme. He played a key part in the 2015 Sunday Times investigation against the IAAF concluding that hundreds of athletes had recorded suspicious results which were not followed up between 2001 and 2012.

“I’m not optimistic that much has changed regarding doping in sport. At best, the status quo has been maintained since the blood passport was introduced in 2008-9. My view on sport is quite jaundiced, and I make no apologies for that. I also fear that there has been a complete drop-off in all anti-doping programmes since the Covid outbreak.

“The resources that anti-doping programmes have are tiny in comparison to [the budgets behind] athletes and teams, so they will always face an uphill battle. I think most athletes who are blood doping are still using the old tried-andtested methods. To the best of my knowledge, there aren’t any new substances; if there are, they certainly can’t be tested for.

“I don’t think the worldwide antidoping effort has been sufficient. Each country has differing rules, loopholes and gaps in policy. We need to harmonise efforts to be able to have true belief. On current scant resources, they will never get on top.”

"Yes" – Dan Lloyd

“I don’t think anyone got into this sport thinking, ‘I can’t wait to shove a needle in my arm’” Professional rider for more than a decade until 2012, and now director of racing at GCN, Dan Lloyd has a positive outlook on the current state of play in the pro peloton.

“The doping question is an impossible one to answer, especially as I’m on the periphery of racing now. My opinion has always been that the sport came from a time where the vast majority of people were doping to some degree because it had become the norm. I’m sure there are still some people who are trying to cheat the system, but it’s not the norm anymore. Most people are doing it the right way, whereas before it was a system in which everyone played that [doping] game.

“I think because the fall-out from the Lance [Armstrong] years didn’t come until 2013, there has been a delayed reaction. Everything people thought they knew about pro cycling was swept away. There is now an assumption that if you see an amazing performance, it’s because of more than just bread, water, hard training and scientific advancements.

“I believe the shift away from doping was originally sponsorforced. We got to the point where the reputation of cycling was so bad, sponsors weren’t willing to take the risk. In the initial stages of change [riders were advised], ‘We can’t organise doping within the team anymore, it’s too risky, but you know what to do, so go ahead and do it alone in private.’ Then it felt like there was another marked shift in 2009-10 where bosses of teams said that we just can’t do this at all anymore. I get the sense now that the whole attitude to doping in the sport has changed. Riders don’t even have to make a choice like they used to.”

This full version of this article was published in the 24 November 2022 print edition of Cycling Weekly . Subscribe online and get the magazine delivered direct to your door every week.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Joe Laverick is a professional cyclist and freelance writer. Hailing from Grimsby but now living in Girona, Joe swapped his first love of football for two wheels in 2014 – the consequence of which has, he jokes, been spiralling out of control ever since. Proud of never having had a "proper job", Joe is aiming to keep it that way for as long as possible. He is also an unapologetic coffee snob.

The UAE Team Emirates rider took a dominant victory at La Doyenne with a decisive attack on La Redoute

By Joseph Lycett Published 21 April 24

The FDJ-SUEZ rider finally takes the victory at La Doyenne after finishing runner-up in 2020 and 2022

Useful links

- Tour de France

- Giro d'Italia

- Vuelta a España

Buyer's Guides

- Best road bikes

- Best gravel bikes

- Best smart turbo trainers

- Best cycling computers

- Editor's Choice

- Bike Reviews

- Component Reviews

- Clothing Reviews

- Contact Future's experts

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookies policy

- Advertise with us

Cycling Weekly is part of Future plc, an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate site . © Future Publishing Limited Quay House, The Ambury, Bath BA1 1UA. All rights reserved. England and Wales company registration number 2008885.

Tour de France’s doping history clouds a ‘cleaner’ sport

Senior Lecturer, University of Kent

Disclosure statement

James Hopker does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

With the start of the 101st Tour de France only one day away, the topic of doping in cycling will no doubt start to rear its ugly head. While the riders cover 3,664km in 21 stages over three weeks in an extraordinary feat of human endurance, the aftershocks of the Lance Armstrong affair continue to colour our approach to the event and its champions.

Armstrong was meant to be the saviour of modern day cycling as it sought to recover from the Festina scandal of 1998 . He was credited with an intense attention to detail and dedicated scientific approach to his preparation; his cycling team was revered for a scientific and systematic approach to training and racing. Both parties were seen as having “too much to lose” to be caught up in the doping scandals that surrounded the sport during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Unfortunately as we now know, this was not the case.

So where does this leave the current crop of cyclists as they push out on the start from the start line of this year’s Tour? Even the most cynical of us hope that the riders are clean, or at least cleaner than the previous decades. The anti-doping debate is also testament to the hope that people involved in the sport want change, and want to believe that professional cycling has cleaned up its act.

Media, sponsor and fan pressure is starting to force teams to take a “zero tolerance” stance on doping, and is undoubtedly behind the decision of Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) President, Brian Cookson, to create the Cycling Independent Reform Commission (CIRC) . Cookson’s actions have won many admirers including International Olympic Committee President, Thomas Bach, who said he was “impressed” with the UCI’s efforts to stamp out doping in the sport.

Change on the horizon?

But is the attitude towards doping in cycling actually changing in the peloton itself? It is difficult to say for certain. Thanks to the history of the sport there will always be scepticism about whether riders are clean. It is unfortunate, but inevitable, that riders and teams who carry the yellow jersey that has been stained by years of doping and cheating, will be questioned. It was no great surprise that many in the sport viewed Chris Froome and Team Sky’s dominance at last year’s Tour with a level of suspicion.

The introduction of the biological passport for athletes in 2008 appears to have had an effect on athlete behavior and attitudes towards doping in the sport. The biological passport monitors certain parameters of a cyclist’s blood over time, making it more difficult for them to dope without detection. The passport does not test for specific banned substances, rather for the manipulation of blood parameters that suggest doping has occurred. Encouragingly, the biological passport has stood up to legal challenges . But it will take more evidence to show that the biological passport provides a long-term deterrent to doping within the sport.

So, why is doping such a big issue in cycling and other endurance-based sports? Well it improves performance, quite significantly, and in some cases by as much as 6% according to research work by Yannis Pitsiladis. Therefore, assuming that professional cycling is cleaning up its act, the Tour should be significantly slower than the 1990s and 2000s. This can be tracked as the Tour often visits the same routes and mountains year on year, affording historical comparisons.

Sports scientists such as Ross Tucker from South Africa have performed these comparisons, which demonstrate that from 2009, the average performance speed and power outputs of top tour riders fell by 5-10%. This is apparent from the fact that the tour winners of 2010 to 2012 being barely able to make the top ten in tours from the 1990s and 2000s.

Cycling power output carries with it some important physiological implications because the cyclist/bicycle system is “closed”: physiological power can be directly measured as mechanical power by a power meter on the bike. Therefore it is possible to estimate, with a few assumptions, what kind of physiology determines a given output. The performances of some riders in the Armstrong era were such that it is hard to believe they were the result of the “normal” training processes, however gifted they were.

In time, technological, training and nutritional advances might slowly narrow the gap between recent performances and those of the 1990s and 2000s. Last year Chris Froome’s ascent of the main mountain stages (Ax-3-Domaines and Mont Ventoux) matched the level of performance seen in the Armstrong era.

Speculation and accusation

Unsurprisingly following Froome’s performance in the mountains fingers started to be pointed at both him and Team Sky. Following a period of concerted pressure from the media, Sky eventually released Froome’s power data for “expert” review. Dave Brailsford, Team Sky Principal, suggested that their reluctance to release Froome’s data was due to the actions of “pseudo scientists” who misinterpret power output data either inadvertently, or deliberately, to make it say more or less what they want.

In some respect Brailsford is absolutely correct, there are many things that influence performance which power output data alone fails to capture (weather, race tactics, equipment calibration), making definitive conclusions difficult. It would be a misapplication of science to accuse a rider of doping due to an unrealistic performance, even though many do.

But secrecy and refusal to openly discuss performances inevitably leads to the speculation about their veracity. What most people strive for is a cleaner sport: at times there appears to be a polarised approach, either look to the future and deny everything from the past, or examine every detail and challenge every performance which from time to time leads to unfair accusations. A balanced approach is probably somewhere in the middle.

At the weekend, all eyes will turn to Froome and Team Sky as Tour favourites. Their performances are currently seen as the benchmark for the rest of the peloton, as well as cycling fans who want to know what it takes to win the Tour.

- Tour de France

- Lance Armstrong

- Sports science

- Anti doping

- Chris Froome

Project Offier - Diversity & Inclusion

Senior Lecturer - Earth System Science

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

Banned blood booster a challenge for anti-doping authorities, expert says

- Medium Text

VINGEGAARD TARGETED

Sign up here.

Reporting by Julien Pretot; Editing by Toby Davis

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. New Tab , opens new tab

Sports Chevron

Trophy Trust reinstates Reggie Bush as 2005 Heisman winner

Due to an evolving landscape in college football, the Heisman Trust ran a reverse to reinstate 2005 winner Reggie Bush on Wednesday.

Crazy Stat Shows Just How Common Doping Was In Cycling When Lance Armstrong Was Winning The Tour de France

Even after Lance Armstrong finally came clean and was banned from cycling for life, many still defend the (unofficial) 7-time Tour de France champion.

The biggest argument for Armstrong is the belief that all riders were doping.

We have known for a while now that a lot of cyclists were doping. A recent breakdown of the extent of the "EPO Era" (named for the most common drug, Erythropoietin) shows the "everybody was doing it" defense may not be that far off.

Teddy Cutler of SportingIntelligence.com recently took a an excellent and detailed look at all the top cyclists from 1998 through 2013 and whether or not they have ever been linked to blood doping or have links to doping or a doctor linked to blood doping.

Related stories

During this 16-year period, 12 Tour de France races were won by cyclists who were confirmed dopers. In addition, of the 81 different riders who finished in the top-10 of the Tour de France during this period, 65% have been caught doping, admitted to blood doping, or have strong associations to doping and are suspected cheaters.

More importantly for Lance Armstrong, during the 7-year window when he won every Tour de France (1999-2005), 87% of the top-10 finishers (61 of 70) were confirmed dopers or suspected of doping.

Of those, 48 (69%) were confirmed, with 39 having been suspended at some point in their career.

None of that excuses Armstrong's behavior, especially outside of the races . But it is clear Armstrong wasn't alone. He was just better at it than anybody else.

- Main content

You are using an outdated and unsupported browser!

We recommend you upgrade your browser. Click here for more info.

You may continue to browse the site but certain functions such as video upload may not work as expected.

Road Cycling

Think lance armstrong was bad he’s got nothing on these crazy cheats from tour de france history, from condoms and cocaine to pains, trains and automobiles – it's incredible what tour de france riders thought they'd get away with....

The doping revelations surrounding Lance Armstrong are largely considered to be the biggest scandal in the history of the Tour de France – and rightly so, the guy got up to all sorts of seedy behaviour on his road through the history books before landing himself on the naughty list.

But although his pick and mix of drugs was one of the most effective ways to cheat on the Tour though, it certainly wasn’t the most imaginative.

Since the race kicked off in 1903 there have been enough strange scandals to make Lance look a saint. From hired hitmen to angry fans forcing riders to wear fake moustaches, it’s a strange old race at times…

1904: Pains, Trains and Automobiles

The second edition of the Tour de France had more unnecessary violence than your average Jason Statham film.

During the first stage, riders Maurice Garin and Lucien Pothier were attacked by four guys in a car who took offence at their early break away from the pack.

While there were no disqualifications because of the attack, two riders were sent packing for getting lifts in a car during the stage, and a 500 franc fine was slapped on a rider who spent the bulk of the stage in the slipstream of a car. Perhaps the same one that was transporting one of his competitors.

Fans chucked rocks, several riders were disqualified for jumping on trains, and piles of nails were dumped on the road. All pretty standard stuff.

During stage two, fans of hometown rider Antoine Faure spread nails and glass along the side of the road, providing an array of flat tyres, and race favourite Maurice Garin was again attacked near the end of the course. Quite the ego-hit for old Maurice.

The last three stages passed by with little impression – just a bunch of fans chucking rocks at the cyclists, several riders being disqualified for jumping on trains, and another classic pile of nails being dumped on the road in stage five. All pretty standard stuff.

Safe to say the security team behind the Tour that year didn’t get much repeat business though.

1911: Game of Groans

After four more riders were chucked for catching a train in 1906, any further attempts to bend the rules were going to have to be a bit stealthier.

Francois Lafourcade agreed and went Game of Thrones style on his rival, spiking the drink of Paul Duboc in stage ten, after the newcomer had won the previous two stages.

Lafourcade’s plan worked perfectly. Duboc was struck down halfway through a stage with food poisoning and left vomiting in the middle of the road.

Henri Pelissier once told a journalist that riders took “cocaine for our eyes and chloroform for our gums.” Nothing too heavy then.

With Tour rules bizarrely blocking the competitor from receiving treatment, Duboc’s competitors closed down the eight minute gap he had opened up, riding – presumably with much confusion – around the young rider as he lay emptying out his lunch in the middle of the road.

Not only did Lafourcade pull off this plan with impressive villainy, he also managed to avoid the blame. Instead, the finger was pointed at eventual winner Gustave Garrigou, who was given a bodyguard and a disguise reportedly consisting of a glued on moustache in order to keep him safe when the Tour reached Rouen, the hometown of Duboc.

It would seem the people of Rouen are very easy to confuse, as he got away with it. Perhaps when someone did recognise him he told them he simply must-dash….?

1924: Share a coke with… Henri

After 29 career victories, Henri Pelissier retired from riding in the Tour de France after 1925.

The rider had had a long standing feud with Henri Desgrange, the founder of the Tour. In one bizarre incident, Desgrange wouldn’t let Pelissier take off his jersey when the sun came up in 1924.

So when asked by the press about the race, the cyclist didn’t hold back.

Pelissier asked a journalist if he knew how the riders kept going during the race before producing a phial from his bag and stating: “That is cocaine for our eyes and chloroform for our gums.”

Nothing too heavy then.

1963: The legend’s switcheroo

Jacques Anquetil is the man when it comes to Tour history. He was the first guy to ever claim five Tour victories and still holds the joint record for the most Tour wins… not counting any EPO enthusiasts of course.

The legendary rider was not averse to a bit of rule bending himself though.

Back then, riders weren’t allowed to change their bike unless there was a mechanical issue. Anquetil had his team director cut his gear cable in the seventeenth stage. He claimed it had snapped and was able to change to a lighter bike, which saw his steam ahead to victory.

On top of this, Anquetil was also partial to the odd bit of morphine injected into the muscle. His reasoning? “You would have to be an imbecile to imagine a professional cyclist who races for 235 days a year can hold the pace without stimulants.” Elegantly said.

1978: The condom crusader

This example has to be categorised as both cheating and failing horribly. In order to pass a drug test, Belgian rider Michel Pollentier stuck a condom filled with another guy’s urine under his arm, connected a tube from his armpit to his shorts and pretended to provide the required urine sample by letting the tubing flow.

The only issue is that his stealthy device clearly wasn’t that stealthy, because the doctor asked him to lift the shirt and his contraption was revealed. That’s got to be awkward.

1998: These bikes are made for walking

Despite the seemingly bulletproof introduction of drug testing in the Tour as far back as 1966, the problem did not disappear. Shockingly.

The discovery that the Festina team were on a doping programme involving an Armstrong-esk range of goodies lead to the French police ambushing any other teams that they thought to be cheating in 1998.

Eight of the eventual top 10 finishers later went on to be either accused or convicted of using PEDs

The result? Not a lot of drug busts, but a whole bunch of angry cyclists. The riders protested first with a peloton sit-down on stage 17, next by agreeing to ride the stage but not race it – resulting in a session that moved at roughly the same pace as this writer on a hangover – and finally with the riders insisting on walking rather than cycling across the finish line at the end the day.

The stage was ruled void by officials, and by the end of the Tour, 93 riders had refused to finish from an original 189 starters.

Ironically, eight of the eventual top 10 finishers later went on to be either accused or convicted of using PEDs too, with US Postal’s Jean-Cyril Robin proving the highest finisher not in any way accused of doping. Those US Postal riders sure are straight-shooters.

2012: The record-breaker’s breakdown

It took a Federal investigation, and investigation from USADA, a whole lot of tears and denials and eventually Oprah Winfrey to get a confession out of him, but it turns out Lance Armstrong took a shitload of drugs.

The record cyclist won seven consecutive Tour de France titles under what the USADA dubbed “the most professionalized and successful doping program that sport has ever seen” – it is hard to deny that he wasn’t pretty good at cheating – and turned the sport he had done so much to promote into utter turmoil in the process.

He also brought the film Dodgeball into disrepute too. And for that we are yet to forgive him.

You may also like:

Blood, Sweat and Gears: The Greatest Rivalries in Tour de France History

This Insane Video Must be the Worst Case of Cheating Ever in a Bike Race

Is This Shark Bike The Coolest Ever In The Tour De France?

There have been some pretty sweet paint-jobs and a load of awesome retro bikes in the Tour de France through the ages. We've rounded them...

Tour De France 2014: Who Should You Bet On To Win?

We've got a few stats that might help you decide...

Privacy Overview

Newsletter terms & conditions.

Please enter your email so we can keep you updated with news, features and the latest offers. If you are not interested you can unsubscribe at any time. We will never sell your data and you'll only get messages from us and our partners whose products and services we think you'll enjoy.

Read our full Privacy Policy as well as Terms & Conditions .

Doping in sport: What is it and how is it being tackled?

- Published 20 August 2015

The issue of doping in sport has been a concern since the 1920s

The issue of doping in sport has been widely discussed in recent weeks, but what exactly is it?

BBC Sport explains what it means, why it has become a hot topic, what the types of doping are and what is being done to tackle it.

What is doping?

Doping means athletes taking illegal substances to improve their performances.

There are five classes of banned drugs, the most common of which are stimulants and hormones. There are health risks involved in taking them and they are banned by sports' governing bodies.

According to the UK Anti-Doping Agency, , external substances and methods are banned when they meet at least two of the three following criteria: they enhance performance, pose a threat to athlete health, or violate the spirit of sport.

Why is it an issue now? A brief history of doping

The use of stimulants and strength-building substances in sport is held to date back as far as Ancient Greece, but it was during the 1920s that restrictions about drug use in sport were first thought necessary. In 1928 the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) - athletics' world governing body - became the first international sports federation to ban doping.

The use of stimulating substances in sport has been around since the Ancient Greeks

In 1966, the world governing bodies for cycling and football were the first to introduce doping tests in their respective world championships, with the first Olympic testing coming in 1968, at the Winter Games in Grenoble and Summer Games in Mexico. By the 1970s, most international federations had introduced drug-testing.

A major drug scandal at the 1998 Tour de France , external underlined the need for an independent international agency to set standards in anti-doping work. The World Anti-Doping Agency (Wada) was established the following year.

In January 2013, the retired American cyclist Lance Armstrong admitted to doping in an interview with Oprah Winfrey, and was stripped of his seven Tour de France wins and banned from sport for life.

In December last year, a German TV documentary alleged as many as 99% of Russian athletes were guilty of doping, although the Russian Athletics Federation described the allegations as "lies".

Since then, there have been numerous further allegations of doping in athletics.

What drugs are people using?

The most commonly used substances are androgenic agents such as anabolic steroids. These allow athletes to train harder, recover more quickly and build more muscle, but they can lead to kidney damage and increased aggression.

Other side-effects include baldness and low sperm count for men, and increased facial hair and deepened voices for women.

Anabolic steroids are usually taken either in tablet form or injected into muscles. Some are applied to the skin in creams or gels.

Then there are stimulants, which make athletes more alert and can overcome the effects of fatigue by increasing heart-rate and blood flow. But they are addictive and, in extreme cases, can lead to heart failure.

Diuretics and masking agents are used to remove fluid from the body, which can hide other drug use or, in sports such as boxing and horse racing, help competitors "make the weight".

One type of doping is the use of erythropoietin (EPO), a hormone naturally produced by the kidneys

Narcotic analgesics and cannabinoids are used to mask the pain caused by injury or fatigue - but in practice can make injuries worse. They are also addictive. Products such as morphine and oxycodone are banned but the opiate-derived painkiller codeine is allowed.

Then there are peptide hormones. These are substances such as EPO (erythropoietin) - which increases bulk, strength and red blood cell count and gives athletes more energy - and HGH (human growth hormone), which builds muscle.

Less common is blood doping, where blood is removed from the body and injected back in later to boost oxygen levels. This practice, which can lead to kidney and heart failure, is banned.

Glucocorticoids mask serious injury because they are anti-inflammatories and affect the metabolism of carbohydrates, fat and proteins, and regulate glycogen and blood pressure levels.

Beta blockers, meanwhile, which may be prescribed for heart attack prevention and high blood pressure, are banned in sports such as archery and shooting because they keep the heart-rate low and reduce trembling in the hands.

A full list of banned substances in athletics can be found on the IAAF website. , external

How is doping detected?

Blood samples, urine samples or both are taken from athletes in an effort to detect doping

Most testing for doping products uses a long-established technique called mass spectrometry.

This involves firing a beam of electrons at urine samples to ionise them - turning the atoms into charged particles by adding or removing electrons.

Each substance the sample contains has a unique "fingerprint" and as the scientists already know the weight of many steroids, for example, they are able to rapidly detect doping.

But there are difficulties with the system.

Some by-products of doping substances are so small they may not produce a strong enough signal for detection.

Blood testing is capable of detecting EPO and synthetic oxygen carriers, but not blood transfusions.

One method introduced to aid the detection of such transfusions is the biological passport.

Brought in by Wada in 2009, the passport aims to reveal the effects of doping rather than detect the substance or method itself.

It is an electronic document about an athlete that contains certain markers from throughout their career. If these change dramatically, it alerts officials that the athlete might be doping.

Some scientists have questioned the passport's efficiency - especially when complicating factors such as training at altitude are factored in - but also its sensitivity to micro-dosing, a little-but-often approach to doping.

Famous doping cases

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Ben Johnson stripped of Olympic gold in Seoul 1988

Prior to Armstrong's confession, Ben Johnson was probably the world's highest-profile drugs cheat. The Canadian sprinter tested positive for anabolic steroids at the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul.

Johnson had won the 100m in a world record of 9.79 seconds but was stripped of his gold medal , external after the positive test and sent home in disgrace.

British sprinter Dwain Chambers was banned from competition for two years , external in 2004 after being found guilty of taking the anabolic steroid THG, while compatriot Linford Christie, a former sprint champion, was suspended from athletics , external in 1999 after failing a drugs test.

Other athletes to have been banned include US sprinters Justin Gatlin , external and Marion Jones. , external

What next in the fight against doping?

New IAAF president Lord Coe has spoken of his determination to prove athletics has "zero tolerance" of doping

Former Olympic 1500m champion Lord Coe was named the new president of the IAAF on Wednesday and says he is determined to prove athletics' world governing body is committed to ridding the sport of drug cheats.

Coe, who has been a strong defender of the IAAF's record, has pledged to set up an independent anti-doping agency for the sport, admitting there is a perception that in-house drug-testing creates "conflicts" and "loopholes".

"There is a zero tolerance to the abuse of doping in my sport and I will maintain that to the very highest level of vigilance," he said.

Meanwhile, the UCI - cycling's world governing body - introduced 24-hour testing earlier this year.

Previously there was no testing between 11pm and 6am, providing a potential window of opportunity for micro-dosing products, such as EPO, without being caught.

Stricter punishments approved by Wada came into effect in January, doubling bans for athletes found guilty of doping from two years to four.

Sir Craig Reedie, Wada's president, maintains more can be done, urging governments to criminalise doping and suggesting , external a blanket ban on countries whose athletes regularly dope could be introduced.

Ferrari retain Raikkonen for 2016

- Published 19 August 2015

Wiggs leads GB one-two at Worlds

Newcastle sign French winger Thauvin

Athletics coverage

- Published 10 September 2015

How to get into athletics

- Published 8 February 2019

Around the BBC

Athletics on the BBC

Catch-up with BBC iPlayer

Radio 5 live Track and Field

Related Internet Links

British Athletics

Union Cycliste Internationale

Anti-Doping: Testing Evolution in Sport

From pin-pricks to the Biological Passport

Judicial investigations and non-analytical evidence today compliment drug testing and are increasingly coming to the fore in the prosecution of doping cases. Testing, however, remains the key weapon in the anti-doping armoury, with a multi-million Euro budget set aside for it every year. Here Feargal McKay takes a look at the way the testing regime has evolved over the last half-century, particularly with a view to cycling.

Bordry prepared to hand over Armstrong's 1999 Tour de France samples

Lance Armstrong confesses to EPO and blood doping

A history on the use of blood transfusions in cycling

A history on blood transfusions in cycling, part 2

A history on blood transfusions in cycling, part 3

Report: Spanish criminal investigation of Armstrong

From pin-pricks to the Passport

Anti-doping tests in cycling began in 1964, at the Tokyo Olympics. Following the death of Knud Enemark Jensen at the previous Olympiad, Pierre Dumas (the Tour de France's doctor) and Maurice Herzog (the French minister for health) had lobbied the UCI and been granted permission to carry out 'health checks' ahead of the hundred kilometre time trial at the Olympics. While some urine samples were collected, Dumas and Herzog were principally concerned with checking riders' bodies for evidence of recent injections. If pin-pricks were found, the riders were simply asked what they had taken and who had administered it.

Over the next couple of years, the anti-doping landscape changed radically. The French and Belgian governments enacted legislation to ban the use of stimulants in sport and began to put some stick about. The Belgians carried out searches at Gent-Wevelgem in 1965, the French at the following year's Tour. These moves effectively forced sport in general to wake up and confront a problem international federations and the Olympic movement had, at best, merely been paying lip service to. Faced with the choice of introducing official, systematic testing of their own or ceding turf to national governments, sport decided to fight the good fight against doping.

Direct Testing

Initially, the only substances that were banned were those that could be tested for. This was principally substances like cocaine, strychnine and amphetamines (although in the case of the latter there were many individual amphetamine-based products that went without a test for several years). Whole classes of drugs – principally steroids – went unbanned until tests could be developed (the first steroid tests didn't arrive until the mid seventies). This attitude changed in the 1980s when the IOC were forced to ban blood transfusions without being able to test for them. Culturally, this is an important point to bear in mind insofar as it has helped inculcate a belief among some athletes and their entourage that if a substance can't be tested for then it isn't doping, a view that has survived in some through to the present day.

At first testing was about finding traces of banned substances in urine samples. Trace evidence of the use of most drugs leaves the system quickly, meaning that the testers generally have a pretty narrow window of opportunity to spot it. But the use of such direct testing methods became even more problematic once substances that were natural to the human body entered the doping armoury. In the early 1980s indirect testing entered the picture, as a way of catching the illegal use of testosterone.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Indirect Testing

Rather than proving the use of testosterone by testing directly for it, Manfred Donike et al (in their paper 'The detection of exogenous testosterone', 1983) proposed that testers should measure the level of testosterone compared to epitestosterone. The human body naturally produces the two in an easy to measure ratio – typically one-to-one – and dosing up on testosterone throws that ratio out of kilter. By setting population limits for what the T/E ratio should be the testers were indirectly able to identify the use of testosterone.

The use of population limits, however, is problematic. Trying to get experts to agree on a fair and equitable population limit is difficult. Initially the T/E ratio was set at 6/1. Over the years this was allowed rise to 10/1 before falling back to 6/1 and is now set at 4/1. We have also seen, with the haematocrit/haemoglobin tests introduced in the 1990s by the UCI and the FIS, that setting a population limit – eg in cycling that of 50% haematocrit for men, 47% for women – can effectively allow doping up to that level.

Indirect testing doesn't have to rely on population limits for its effectiveness. It can also look at the levels of individual biomarkers. In ordinary medicine biomarkers have long been a way of diagnosing disease: levels of cholesterol in blood are indicative of heart disease, for example. In 1987, Bo Berglund published a scientific paper – 'Detection of autologous blood-transfusions in cross-country skiers' – in which he proposed using the levels of the hormone EPO as a way of spotting the use of a blood transfusion. Extracting blood causes the body to increase the levels of EPO in an effort to ramp-up production of red blood cells and replace those extracted. Re-infusing blood causes the opposite to happen as fewer new red blood cells are needed. By measuring the levels of EPO between two tests, taken a week or so apart, Berglund figured that transfusions could easily be spotted.

Unfortunately for Berglund and his team, 1987 was the cusp of the era of EPO doping, effectively negating the value of any test based on measuring levels of EPO. The proposed test is nonetheless interesting, regardless of its applicability, for as well as using indirect testing, by comparing the differences between two samples Berglund was pushing open the door to longitudinal analysis. Berglund's test was also somewhat novel in that it relied on a mix of in-competition and out-of-competition testing.

Out-of-Competition Testing

OOC testing had been in use for a decade or so at that stage, with Norwegian authorities having begun carrying out OOC tests on their athletes in 1977. Before then all testing had been done in-competition, despite authorities being fully aware of the value of doping as a training aid as well as a competition aid. In 1982 FISA, rowing's governing body, became the first international federation to approve the use of out-of-competition testing on its members, introducing short-notice OOC testing. By the end of the 1980s the use of OOC testing was widespread across a range of sports.

The effectiveness of early OOC testing was limited by a number of factors. Even after international federations came on board, some national federations were more lacklustre than others in implementing the procedure. But, for OOC testing to work, it requires a degree of co-operation among national federations in order to carry out testing on each others athletes when they train abroad. To combat this problem, in 1990 the IAAF introduced an anti-doping flying-squad, who could go anywhere and test anyone. The effectiveness of OOC testing was also limited by advance warning been given of tests: it wasn't until the 1990s that unannounced OOC testing became the norm.

The biggest problem with OOC testing, though, was knowing where athletes were in order to test them. Up to the era of WADA and the advent of the wherabouts module of ADAMS – the online Anti-Doping Administration Management System – effective OOC testing was pretty much limited to off-days during national and world championships. For the rest of the year testers could turn up at training camps or at athletes' homes, but an athlete not being available to them didn't matter much. By the late 1990s the OOC testing system was so inefficient that testers were completing fewer than half of their testing missions because of athlete unavailability. In the early 2000s USADA were first to implement a proper wherabouts system and to introduce to the three-strikes rule, under which multiple missed tests resulted in a sanctionable offence. In cycling, this didn't happen until 2006, with dire consequences for Michael Rasmussen the following year.

Wherabouts information is key to carrying out OOC tests. But, in an age of data protection laws, the collection of such information is under threat. With the rise of social media European Union authorities are taking a hard look at existing data protection laws and some of the changes proposed may challenge the ability of sports federations to collect wherabouts information and transfer it between one and other. At a WADA Executive Committee meeting held last year Pat McQuaid likened the proposed legislative changes to criminals getting the support of the EU to close down Interpol. WADA President John Fahey agreed that, without amendment, the proposed EU legislation would destroy WADA's capacity to fight doping in Europe in any real sense.

Blood Testing

Another major change in the way anti-doping tests are conducted was the advent of blood testing. From the introduction of doping controls in the 1960s cheaters have found ways around urine-based controls, from secreting containers of urine about their person to injecting clean urine into their bladders. In 1988 the ski federation, FIS, led the way with blood testing with the IOC coming on board for the Lillehammer Winter Olympics in 1992. Cycling followed suit in 1994. But even when following orders from the IOC the UCI was somewhat reluctant to adopt blood testing. Speaking in January 1997 Hein Verbruggen noted that "It must be made clear that our anti-drug commission has always been against blood test controls because of ethical problems." Other federations, of course, have been even more reluctant to collect blood samples and simply don’t bother.

Retrospective Testing

Testing took another new turn in 1999 with the promise of retrospective re-testing of stored samples. The previous year, after a decade of trying to sweep the EPO problem under the carpet, cycling authorities were forced to confront the issue of blood doping. Fortunately, after years of searching and false promises, an EPO test was on the horizon and set to be rolled out at the Sydney Olympics in 2000. In response to persistent criticism in the media and from the likes of Gérard Dine and the ASO, the UCI promised to put all samples from the 1999 Tour on ice and re-analyse them once the EPO test had been validated. When, in 2001, cycling introduced the EPO test ahead of the Classics season, the UCI giddily proclaimed that "the monster has been vanquished. Success at last!" They then promptly forgot their promise to re-test the 1999 Tour's samples .

One reason for this may have been that the UCI thought they had legal issues with re-testing. Certainly the 2006 Vrijman report into the re-testing of stored samples from the 1999 Tour de France for research purposes challenged the use of retrospective testing. Vrijman noted that there were neither rules nor procedures for the conducting of such tests and pointed out that existing rules required that doping control forms be destroyed after two years (while the samples they identified could be stored for eight). He also questioned the reliability of tests on stored samples insofar as detection methods had been validated on samples collected only a short time before testing. According to Vrijman, it was "simply irresponsible" to suggest that disciplinary procedures could be initiated on the basis of such tests and "the spectre of meaningful retrospective testing that could yield lawful sanctions against athletes remains nothing more than an empty threat."

Retrospective testing had been used in the past, such as when the T/E test came in, but only to establish the scale of the problem and not to initiate disciplinary procedures against individuals. As a means of bringing charges, retrospective testing has – despite the concerns expressed by Vrijman – been used successfully in more recent years. Ahead of the London Olympics WADA turned the clock back to 2004 and decided to re-test a small number of the remaining stored samples, before the statute of limitation rules kicked in and they got flushed down the drain. That resulted in an additional five violations being identified. The IAAF recently completed retrospective testing of samples from 2005, resulting in six new violations being identified and five medals having to be reallocated. The IAAF also bumped three athletes from the London Games after re-testing samples from 2011 ahead of the Olympics.

The key issue surrounding retrospective testing appears to be inconsistencies on how long samples are stored for: some, from the Olympics or the Tour, might be stored for the full eight years of the statute of limitations, while others are flushed within months. Storage is an expensive proposition and the money simply isn’t there to store everything.

Probably the bigger issue though is authorities blowing hot and cold on the issue of retrospective testing: at the one moment trying to talk it up as a way of scaring people into refraining from doping while at the other too scared to really use it for fear of what it will reveal. Within cycling, as a means of picking off individuals the UCI seems happy to use retrospective testing in certain individual cases – as they did in the case of Thomas Dekker – but as a means of policing the entire peloton it is a tool the UCI appears unwilling to use.

Longitudinal Testing

In 1999, in response to the Festina scandal of the year before, French authorities – lead by Gérard Dine – introduced quarterly health checks as a way of combating the doping problem. Like the haemeatocrit/haemoglobin tests introduced a few years earlier, these were technically not doping tests and riders who failed them could only be 'rested' on health grounds. But by comparing data between one health check and another – longitudinally – the authorities were at least able to use the threat of temporary suspension to encourage French riders to reduce their doping. The problem, though, was that this was applicable only to French riders. And then not even all French riders: Laurent Jalabert and Richard Virenque simply moved abroad to avoid having to submit themselves to the health checks.

The idea of longitudinal testing had been around for some time at this stage – Bo Berglund, as we've seen, had tried using a version of it in 1987 – and interest in it grew rapidly through the early years of the new century. In 2003 Malcoveti et at published 'Hematologic passport for athletes competing in endurance sports: a feasibility study.' By 2007 Berglund and others in Sweden had come up with a Passport project while Peierre-Edourad Sottas and others at the Lausanne laboratory had begun working on a forensic approach to the interpretation of biomarkers (indirect testing) and using Bayesian statistics to interpret haematological values.

Initially the private sector was able to adapt to the new possibilities quicker than sports federations, with independent anti-doping programmes being offered to cycling teams by the likes of ACE and Rasmus Damsgaard. For various reasons these found a number of willing clients: by the end of 2006 Bjarne Riis, Bob Stapleton and Jonathan Vaughters were all using independent testing in their teams. Within a year the UCI announced the introduction of the Biological Passport .

The Athlete Biological Passport

In theory, the Athlete Biological Passport is the crowning glory of half a century of advances in drug testing. Individually, each of the components of the testing regime that have been developed over the last five decades have weaknesses which hamper their effectiveness. But taken collectively, in the form of the ABP, the impact of those weaknesses is lessened. Longitudinal indirect testing of blood and urine samples collected in- and out-of-competition allow profiles to be created for each individual athlete and from those profiles individual thresholds established. Profiles that fall outside of these individual limits get flagged as potential anti-doping violations. Other profiles can get flagged for ether retrospective testing of stored samples for particular substances, or individuals can be identified for targeted testing. The Passport thus becomes a means to collect all available information on one individual and, based on an analysis of that data, identify the most appropriate tool to use if doping is suspected.

That, at least, is the theory. Practice and theory differ somewhat, though. The most obvious difference is that the version of the Passport that exists today is incomplete. A complete Passport should be capable of spotting both steroid-based doping and oxygen vector doping. At present the ABP is capable only of spotting the latter: the steroid profile is still under development. FIFA – one of two federations to become recent high-profile adopters of the Passport principle – have promised to have the steroid profile up and running when they introduce the Passport in 2014. But the UCI have been promising the arrival of the steroid profile since 2007.

A fully-functioning ABP will still not be foolproof. Fifty years of history has shown that those who choose to dope adapt to their changing environment. As a minimum, though, a functioning ABP holds out the promise of being able to control the levels of doping and level the playing field somewhat for those who want to compete clean. And, implemented properly, the ABP does offer those federations that wish to really root out doping the opportunity to use the information it produces to target those most likely to have committed an offence. If the will is there to use it properly, the Passport can be a powerful weapon in the anti-doping armoury.

Thank you for reading 5 articles in the past 30 days*

Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read any 5 articles for free in each 30-day period, this automatically resets

After your trial you will be billed £4.99 $7.99 €5.99 per month, cancel anytime. Or sign up for one year for just £49 $79 €59

Try your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Tadej Pogačar can dominate the Giro d’Italia but nobody can control its chaos – Analysis

Best bike phone mounts 2024: Stylish and practical phone holders

Tour de Romandie: Godon and Vendrame go 1-2 for Decathlon AG2R on stage 1

Most Popular

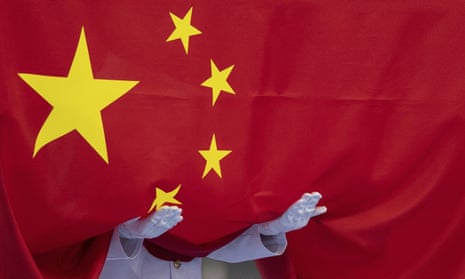

The Chinese swimming doping scandal: What we know about bombshell allegations and WADA's response

The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) is under fire this week after a pair of news outlets, including the New York Times , reported that 23 Chinese swimmers quietly tested positive for the same banned substance prior to the 2021 Tokyo Olympics.

WADA confirmed the substance of the news reports over the weekend , including the number of positive tests and the substance involved, trimetazidine. But it said it did not push for the swimmers to be punished at the time because it had accepted the findings of a Chinese investigation, which said the positive tests were caused by contamination at a hotel kitchen and the athletes were innocent.

WADA also said it did not have the power to disclose the positive tests, under current anti-doping rules, because China's anti-doping arm (CHINADA) ruled that no anti-doping violations were committed.

The scandal has sparked outrage in some corners of the anti-doping world, with U.S. Anti-Doping Agency chief Travis Tygart among those criticizing WADA and CHINADA for "(sweeping) these positives under the carpet)." It's also raised both new and old questions about the convoluted processes and guardrails of the global anti-doping system, with the next Summer Olympics in Paris now less than 100 days away .

So what's all the hubbub about exactly? Here's a breakdown of what happened, what the key players have said and why the Chinese swimming case has inflamed so many long-standing frustrations in the world of Olympic sports.

When did this scandal start?

In a virtual news conference Monday , WADA offered a detailed timeline of the events courtesy of general counsel Ross Wenzel, who worked on the case for WADA as an outside lawyer prior to assuming his current role in 2022.

According to Wenzel, Chinese anti-doping authorities collected 60 urine samples at a national swimming meet that ended January 3, 2021. More than two months later, on March 15, CHINADA informed WADA that it had recorded 28 positive tests. In April, CHINADA said it would investigate, with the help of public health authorities.

By the end of May, CHINADA relayed the preliminary findings of its investigation, which found trace amounts of the banned substance at a hotel where all 23 of the athletes were staying − specifically, in spice containers at the hotel's kitchen and drainage units in its hotel. It informed WADA on June 15 that it would not be charging the swimmers with anti-doping violations, officially ruling that the positive tests were caused by environmental/food contamination.

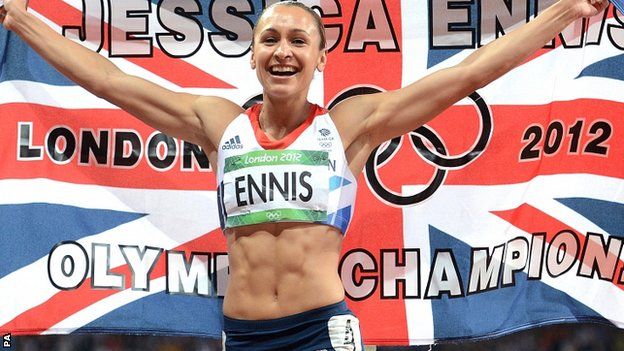

What is trimetazidine, or TMZ?