- The Contents

- The Making of

- Where Are They Now

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Q & A with Ed Stone

golden record

Where are they now.

- frequently asked questions

- Q&A with Ed Stone

News | September 12, 2013

How do we know when voyager reaches interstellar space.

Whether and when NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft, humankind's most distant object, broke through to interstellar space, the space between stars, has been a thorny issue. For the last year, claims have surfaced every few months that Voyager 1 has "left our solar system." Why has the Voyager team held off from saying the craft reached interstellar space until now?

"We have been cautious because we're dealing with one of the most important milestones in the history of exploration," said Voyager Project Scientist Ed Stone of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. "Only now do we have the data -- and the analysis -- we needed."

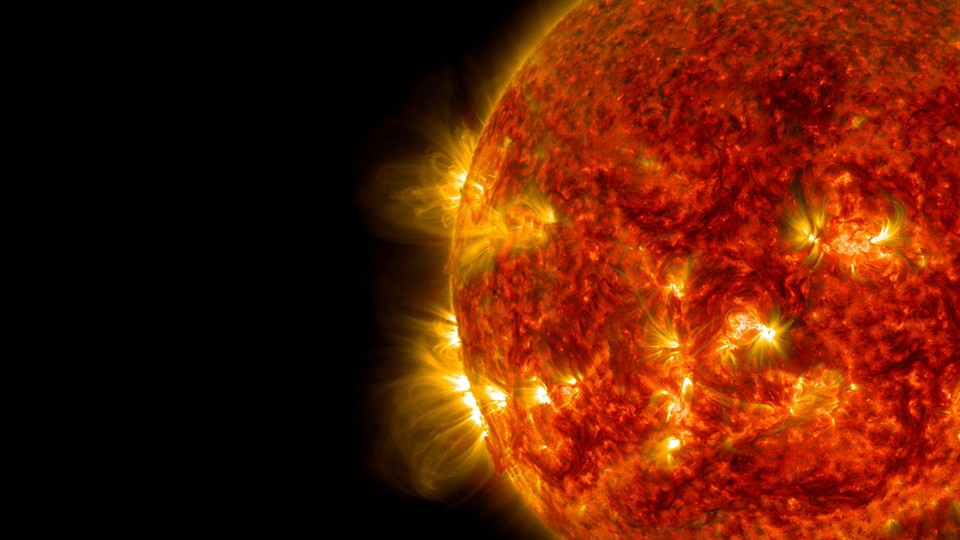

Basically, the team needed more data on plasma, which is ionized gas, the densest and slowest moving of charged particles in space. (The glow of neon in a storefront sign is an example of plasma.) Plasma is the most important marker that distinguishes whether Voyager 1 is inside the solar bubble, known as the heliosphere, which is inflated by plasma that streams outward from our sun, or in interstellar space and surrounded by material ejected by the explosion of nearby giant stars millions of years ago. Adding to the challenge: they didn't know how they'd be able to detect it.

"We looked for the signs predicted by the models that use the best available data, but until now we had no measurements of the plasma from Voyager 1," said Stone.

Scientific debates can take years, even decades to settle, especially when more data are needed. It took decades, for instance, for scientists to understand the idea of plate tectonics, the theory that explains the shape of Earth's continents and the structure of its sea floors. First introduced in the 1910s, continental drift and related ideas were controversial for years. A mature theory of plate tectonics didn't emerge until the 1950s and 1960s. Only after scientists gathered data showing that sea floors slowly spread out from mid-ocean ridges did they finally start accepting the theory. Most active geophysicists accepted plate tectonics by the late 1960s, though some never did.

Voyager 1 is exploring an even more unfamiliar place than our Earth's sea floors -- a place more than 11 billion miles (17 billion kilometers) away from our sun. It has been sending back so much unexpected data that the science team has been grappling with the question of how to explain all the information. None of the handful of models the Voyager team uses as blueprints have accounted for the observations about the transition between our heliosphere and the interstellar medium in detail. The team has known it might take months, or longer, to understand the data fully and draw their conclusions.

"No one has been to interstellar space before, and it's like traveling with guidebooks that are incomplete," said Stone. "Still, uncertainty is part of exploration. We wouldn't go exploring if we knew exactly what we'd find."

The two Voyager spacecraft were launched in 1977 and, between them, had visited Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune by 1989. Voyager 1's plasma instrument, which measures the density, temperature and speed of plasma, stopped working in 1980, right after its last planetary flyby. When Voyager 1 detected the pressure of interstellar space on our heliosphere in 2004, the science team didn't have the instrument that would provide the most direct measurements of plasma. Instead, they focused on the direction of the magnetic field as a proxy for source of the plasma. Since solar plasma carries the magnetic field lines emanating from the sun and interstellar plasma carries interstellar magnetic field lines, the directions of the solar and interstellar magnetic fields were expected to differ.

Most models told the Voyager science team to expect an abrupt change in the magnetic field direction as Voyager switched from the solar magnetic field lines inside our solar bubble to those in interstellar space. The models also said to expect the levels of charged particles originating from inside the heliosphere to drop and the levels of galactic cosmic rays, which originate outside the heliosphere, to jump.

In May 2012, the number of galactic cosmic rays made its first significant jump, while some of the inside particles made their first significant dip. The pace of change quickened dramatically on July 28, 2012. After five days, the intensities returned to what they had been. This was the first taste of a new region, and at the time Voyager scientists thought the spacecraft might have briefly touched the edge of interstellar space.

By Aug. 25, when, as we now know, Voyager 1 entered this new region for good, all the lower-energy particles from inside zipped away. Some inside particles dropped by more than a factor of 1,000 compared to 2004. The levels of galactic cosmic rays jumped to the highest of the entire mission. These would be the expected changes if Voyager 1 had crossed the heliopause, which is the boundary between the heliosphere and interstellar space. However, subsequent analysis of the magnetic field data revealed that even though the magnetic field strength jumped by 60 percent at the boundary, the direction changed less than 2 degrees. This suggested that Voyager 1 had not left the solar magnetic field and had only entered a new region, still inside our solar bubble, that had been depleted of inside particles.

Then, in April 2013, scientists got another piece of the puzzle by chance. For the first eight years of exploring the heliosheath, which is the outer layer of the heliosphere, Voyager's plasma wave instrument had heard nothing. But the plasma wave science team, led by Don Gurnett and Bill Kurth at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, had observed bursts of radio waves in 1983 to 1984 and again in 1992 to 1993. They deduced these bursts were produced by the interstellar plasma when a large outburst of solar material would plow into it and cause it to oscillate. It took about 400 days for such solar outbursts to reach interstellar space, leading to an estimated distance of 117 to 177 AU (117 to 177 times the distance from the sun to the Earth) to the heliopause. They knew, though, that they would be able to observe plasma oscillations directly once Voyager 1 was surrounded by interstellar plasma.

Then on April 9, 2013, it happened: Voyager 1's plasma wave instrument picked up local plasma oscillations. Scientists think they probably stemmed from a burst of solar activity from a year before, a burst that has become known as the St. Patrick's Day Solar Storms. The oscillations increased in pitch through May 22 and indicated that Voyager was moving into an increasingly dense region of plasma. This plasma had the signatures of interstellar plasma, with a density more than 40 times that observed by Voyager 2 in the heliosheath.

Gurnett and Kurth began going through the recent data and found a fainter, lower-frequency set of oscillations from Oct. 23 to Nov. 27, 2012. When they extrapolated back, they deduced that Voyager had first encountered this dense interstellar plasma in August 2012, consistent with the sharp boundaries in the charged particle and magnetic field data on August 25.

Stone called three meetings of the Voyager team. They had to decide how to define the boundary between our solar bubble and interstellar space and how to interpret all the data Voyager 1 had been sending back. There was general agreement Voyager 1 was seeing interstellar plasma, based on the results from Gurnett and Kurth, but the sun still had influence. One persisting sign of solar influence, for example, was the detection of outside particles hitting Voyager from some directions more than others. In interstellar space, these particles would be expected to hit Voyager uniformly from all directions.

"Now that we had actual measurements of the plasma environment - by way of an unexpected outburst from the sun - we had to reconsider why there was still solar influence on the magnetic field and plasma in interstellar space," Stone said. "The path to interstellar space has been a lot more complicated than we imagined."

Stone discussed with the Voyager science group whether they thought Voyager 1 had crossed the heliopause. What should they call the region were Voyager 1 is?

"In the end, there was general agreement that Voyager 1 was indeed outside in interstellar space," Stone said. "But that location comes with some disclaimers - we're in a mixed, transitional region of interstellar space. We don't know when we'll reach interstellar space free from the influence of our solar bubble."

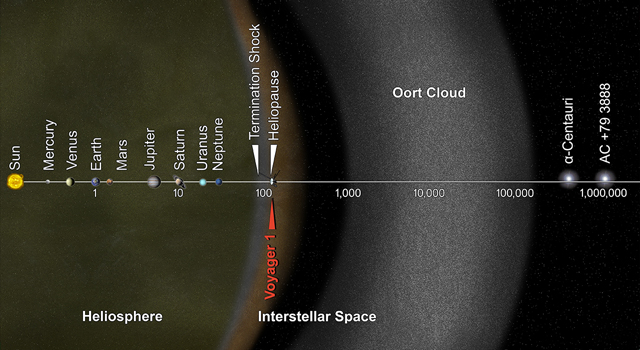

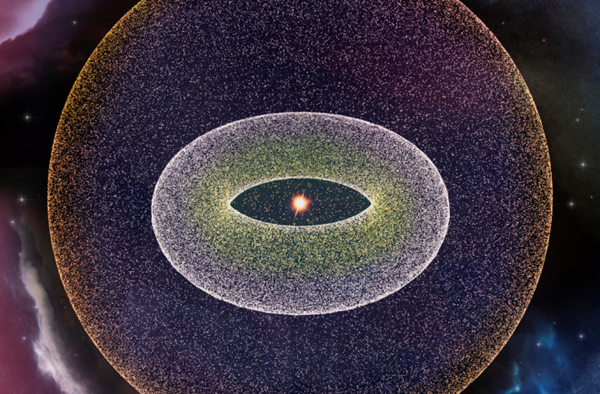

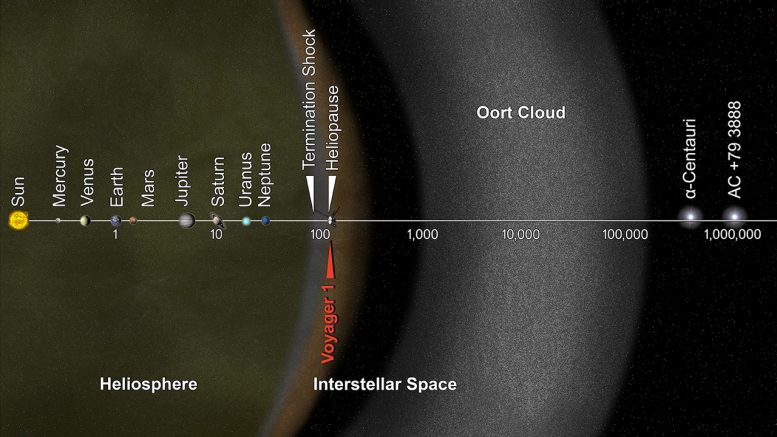

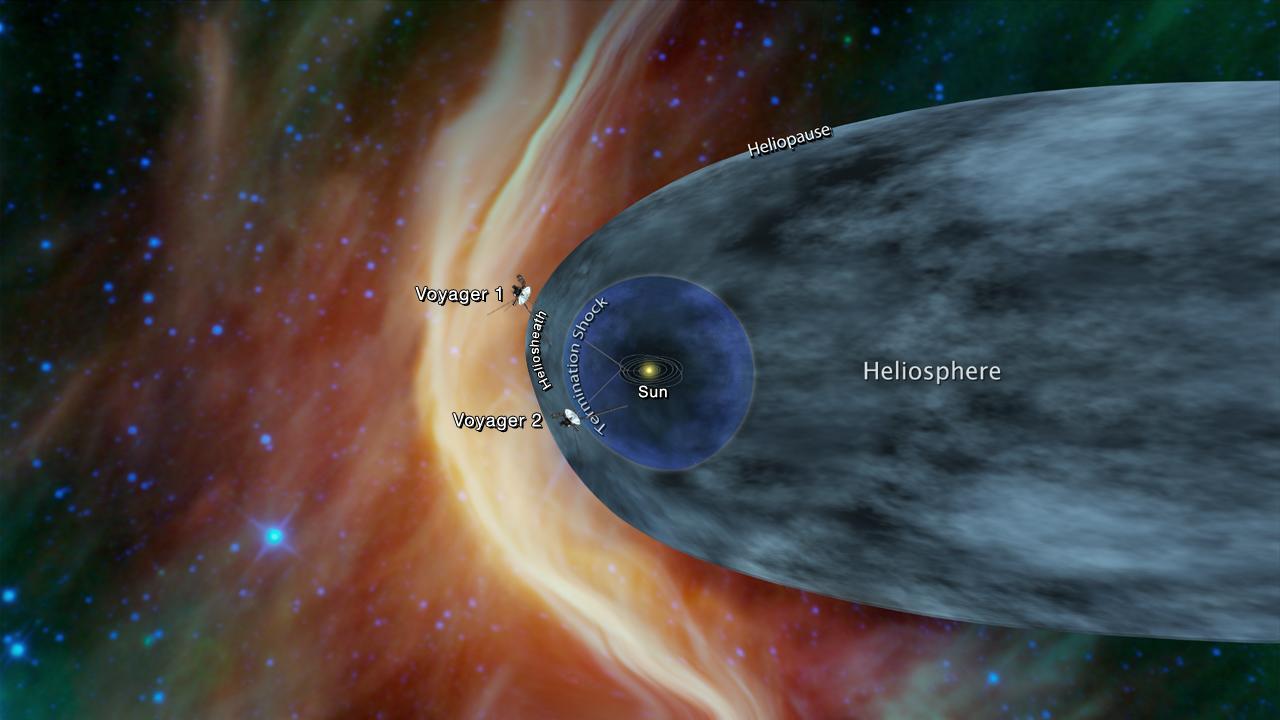

So, would the team say Voyager 1 has left the solar system? Not exactly - and that's part of the confusion. Since the 1960s, most scientists have defined our solar system as going out to the Oort Cloud, where the comets that swing by our sun on long timescales originate. That area is where the gravity of other stars begins to dominate that of the sun. It will take about 300 years for Voyager 1 to reach the inner edge of the Oort Cloud and possibly about 30,000 years to fly beyond it. Informally, of course, "solar system" typically means the planetary neighborhood around our sun. Because of this ambiguity, the Voyager team has lately favored talking about interstellar space, which is specifically the space between each star's realm of plasma influence.

"What we can say is Voyager 1 is bathed in matter from other stars," Stone said. "What we can't say is what exact discoveries await Voyager's continued journey. No one was able to predict all of the details that Voyager 1 has seen. So we expect more surprises."

Voyager 1, which is working with a finite power supply, has enough electrical power to keep operating the fields and particles science instruments through at least 2020, which will mark 43 years of continual operation. At that point, mission managers will have to start turning off these instruments one by one to conserve power, with the last one turning off around 2025.

Voyager 1 will continue sending engineering data for a few more years after the last science instrument is turned off, but after that it will be sailing on as a silent ambassador. In about 40,000 years, it will be closer to the star AC +79 3888 than our own sun. (AC +79 3888 is traveling toward us faster than we are traveling towards it, so while Alpha Centauri is the next closest star now, it won't be in 40,000 years.) And for the rest of time, Voyager 1 will continue orbiting around the heart of the Milky Way galaxy, with our sun but a tiny point of light among many.

The Voyager spacecraft were built and continue to be operated by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in Pasadena, Calif. Caltech manages JPL for NASA. The Voyager missions are a part of NASA's Heliophysics System Observatory, sponsored by the Heliophysics Division of the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington.

For more information about Voyager, visit: http://www.nasa.gov/voyager and https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov .

How the most distant object ever made by humans is spending its dying days

Voyager 1 continues to observe the farthest corners of the solar system—but it may not for long.

By Rahul Rao | Published Apr 28, 2021 4:00 PM EDT

The eyes of the world might be fixed upon Mars, where last week alone, the Ingenuity helicopter took flight and the Perseverance rover made oxygen . But farther—much farther—Voyager 1, one of the oldest space probes and the most distant human-made object from Earth, is still doing science.

The probe is well into the fourth decade of its mission, and it hasn’t come near a planet since it flew past Saturn in 1980. But even as it drifts farther and farther from a dimming sun, it’s still sending information back to Earth, as scientists recently reported in The Astrophysical Journal.

For decades, Voyager has been sailing away at around 11 miles (17 kilometers) every second. Each year, it travels another 3.5 AU (the distance between Earth and the sun) away from us. Now, it’s sending messages home even as it prepares to leave this solar system behind.

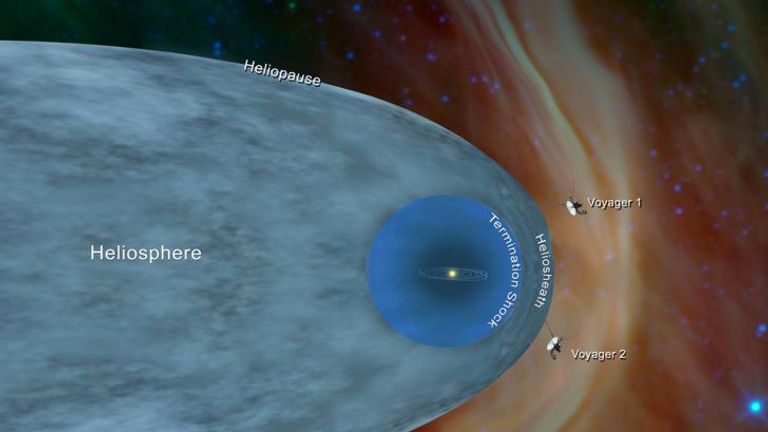

There are multiple ways to think about the “edge of the solar system.” One is a boundary region called the heliopause. That’s the frontier where the solar wind (the soup of charged particles continually thrown off by the sun) is too weak to hold off the interstellar medium—the plasma, dust, and radiation that fill the bulk of space.

When Voyager 1 left Earth in 1977, nobody was certain where the heliopause was, according to Bill Kurth , an astrophysicist at the University of Iowa who has been working with Voyager 1 since before it launched. Some scientists then even thought the heliopause was as close as 10 or even 5 AU—around the orbits of Jupiter, which Voyager 1 passed in 1979, or Saturn.

In reality, the heliopause is around 120 AU away. We know this partly because Voyager 1 crossed the heliopause in August 2012, a whole three and a half decades after it departed Earth. That puts the probe well and truly in interstellar space.

[Related: Voyager 2 can finally probe the rarified plasma surrounding our solar system ]

Out here, space is filled with interstellar medium—but you’ll not see very much of it. A cube of air at sea level on Earth contains more than a trillion times as many molecules as an equal-sized cube of even the interstellar medium’s densest parts. The region that Voyager 1 is traversing is sparser still. And for the most part, it’s quiet.

But every few years, as Voyager 1 records more data about the plasma and dust out here, it finds something . For instance, in 2012 and again in 2014, Voyager 1 felt a shock. According to Kurth, what Voyager 1 recorded was a magnetic spike, accompanied by a burst of energetic electrons that caused intense, oscillating electric fields. These shocks are the most distant effects of the sun, rippling outwards even past the heliopause.

What Voyager 1 encountered in 2020 was another jump in magnetic field strength, but without those intense electrical oscillations. Scientists instead think it’s a pressure front, a much more subtle disturbance moving out into the interstellar medium. Voyager 1 previously encountered something like it in 2017.

According to Jon Richardson , an astrophysicist at MIT who wasn’t an author on the paper, this latest finding shows that Voyager 1 is still capable of surprising scientists. Normally, he says, the probe would need to experience a shock in the surrounding plasma to measure its density. But with observations like this one, scientists have found a way to use Voyager 1 to continually monitor that density—over 13 billion miles away from us.

Richardson also says the findings show that Voyager 1 continues to feel the sun’s tendrils, billions of miles past the heliopause. “The sun is still having a major effect,” he says, “far outside the heliosphere.”

Meanwhile, Voyager 1 is still within the sun’s gravitational influence. In about 300 years, scientists expect, Voyager 1 will start to enter the inner edge of the Oort cloud, that shroud of comets which stretches as far as several light-years away.

We’ve never actually seen evidence of the Oort cloud, but sadly, Voyager 1 likely won’t be the one to reveal it. The probe is quite literally living on borrowed time. Plutonium-238, the radioisotope that powers the probe’s generator, has a half-life of about 88 years.

[Related: Ask Us Anything: What happens to your body when you die in space? ]

As a result, Voyager 1 is starting to lose fuel. Scientists are already having to make choices about which parts of the probe they should keep functional. By the mid-2020s, it’s likely that the probe won’t be able to power even a single instrument.

Still, scientists like Kurth hope they can eke the probe’s life out to 2027, the 50th anniversary of its launch. That, Kurth says, is a milestone that none of Voyager 1’s designers could ever have foreseen.

Rahul Rao is a former intern and contributing science writer for Popular Science since early 2021. He covers physics, space, technology, and their intersections with each other and everything else. Contact the author here.

Like science, tech, and DIY projects?

Sign up to receive Popular Science's emails and get the highlights.

It should take another 300 years for NASA's Voyager 1 probe to reach the most distant region of our solar system. Until then, it's cruising through the void between the stars.

- Voyagers 1 and 2 are exploring the mysterious region between stars called interstellar space.

- NASA launched the twin probes in 1977 for a five-year mission to trek across the solar system.

- Nearly 46 years later, the two spacecraft are still going and are the farthest man-made objects from Earth.

Some 14.8 billion miles from Earth, the Voyager 1 probe is cruising through the blackness of the interstellar medium — the unexplored space between stars. It's the farthest human-made object from our planet.

Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 launched in 1977 within 16 days of one another with a design lifetime of five years to study Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and their respective moons up close, according to NASA.

Nearly 46 years into their mission , they've each made history by boldly venturing beyond the boundary of our sun's influence, known as the heliopause.

Both plucky spacecraft continue to send data back from beyond the solar system. Even though they've had some brief interruptions — it seems their cosmic journeys are far from over.

In 300 years, Voyager 1 could see the Oort Cloud, and in 296,000 years, Voyager 2 could pass by Sirius

As part of an ongoing power-management effort that has ramped up in recent years, engineers have been powering down non-technical systems on board the Voyager probes, like their science-instruments heaters, hoping to keep the spacecraft going through 2030 .

After that, the probes will likely lose their ability to communicate with Earth.

Still, even after NASA shuts down their instruments and calls the Voyager mission to an end, the twin probes will continue to drift out in interstellar space.

Related stories

NASA said that about 300 years from now, Voyager 1 should enter the Oort Cloud, a spherical band far beyond Pluto's orbit that's full of billions of frozen comets. It should take another 30,000 years to reach the end of it.

The spacecraft are taking different paths as they head out into deep space. Voyager 2 is only about 12.3 billion miles away from Earth today.

It should take the Voyager 1 probe approximately 40,000 years to reach AC+79 3888, a star in the constellation Camelopardalis, according to NASA .

The agency added that in some 296,000 years, Voyager 2 should drift by Sirius, the brightest star in our night sky.

"The Voyagers are destined — perhaps eternally — to wander the Milky Way," NASA said.

'It's really remarkable that both spacecraft are still operating'

NASA designed the twin spacecraft to study the outer solar system. After completing their primary mission, the Voyagers kept chugging along, taking a grand tour of our galaxy and capturing breathtaking cosmic views.

On February 14, 1990, the Voyager 1 spacecraft captured the " Pale Blue Dot " image from almost 4 billion miles away. It's an iconic image of Earth within a scattered ray of sunlight, and it's the farthest view of Earth any spacecraft has captured.

For the last decade , Voyager 1 has been exploring interstellar space, which is full of gas, dust, and charged energetic particles. Voyager 2 reached interstellar space in 2018 , six years after its twin.

Their observations of the interstellar gas they're moving through has revolutionized astronomers' understanding of this unexplored space beyond our own cosmic backyard.

"It's really remarkable that both spacecraft are still operating and operating well — little glitches, but operating extremely well and still sending back this valuable data," Suzanne Dodd, the project manager for the Voyager mission at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, previously told Insider , adding, "They're still talking to us."

This post has been updated. This story was originally published in December 2022.

Watch: NASA is flying a $1.5 billion spacecraft into the sun — here's why

- Main content

NASA Voyager 1 Now Floating 14.6 Billion Miles Away From Earth, Might Be Going to Oort Cloud After Being Restored

NASA's Voyager 1 is a one-of-a-kind spacecraft as no other space probe has gone farther than it. The Voyager 1 was launched in 1977 to fly by Jupiter and Saturn and then cross into outer space in August 2012 to continue collecting data. Together with its sister, Voyager 2, the two spacecraft have been flying longer than any other spacecraft in history.

But like most machines, technical issues are inevitable, and fixing Voyager 1 while still in space was indeed a challenge. Science Times previously reported that NASA successfully fixed the spacecraft's AACS module and now continues with its mission.

Technical Issues on Voyager 1

The 45-year-old spacecraft was operating well and transmitting data back to Earth normally until mid-May when the board system of Voyager 1 responsible for keeping its antenna pointed at Earth known as the attitude articulation and control system (AACS) started sending jumbles of data, Inverse reported.

It is different from the usual reports about the health and status of the spacecraft. The data looked like it developed some electronic version of aphasia, which causes it to lose fluent speech. NASA explained in a statement that the data appeared to be randomly generated or does not reflect the good status of AACS.

Furthermore, Voyager 1 appeared to be in perfect shape despite its bizarre status report. The spacecraft's radio signal remained strong and steady and its science systems kept gathering and transmitting data. But what was wrong with the AACS is that it did not trip a fault protection system that should put Voyager 1 in a safe mood when a glitch happens.

Fortunately, NASA was able to diagnose the problem and revealed that the AACS had started sending data via an onboard computer that stopped operating a few years ago. Due to this, it corrupted outgoing data and NASA engineers had to send the command to the AAVS to use the correct computer when sending data back home.

ALSO READ: NASA To Shut Down 44-Year-Old Voyager Program Soon; Is The Spacecraft Dying?

Is Voyager 1 Going to the Oort Cloud?

Voyager 1 is currently more than 14.6 billion miles (23.5 billion kilometers) away from Earth. The 45-year-old spacecraft has been in the interstellar medium for several years after crossing the heliosphere where the collar winds meet the cold and dense interstellar medium, Oicanadian reports. The space probe has since sent valuable data back home, especially on how the heliosphere interacts with the interstellar winds.

The data led scientists to important discoveries, like the detection of a new type of electron burst in 2020. Nicola Fox, director of the heliophysics division at NASA headquarters, said that the information about the limit of the Sun's influence gives unprecedented insight into unchartered territory.

On the other hand, the space probe and its twin space probe Voyager 2 are still far from truly leaving the Solar System. The Oort cloud serves as the boundary between the Solar System and beyond where the Sun can no longer exert its gravitational influence.

Previous studies suggest that the Oort cloud is about 1,000 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun and extends to 100,000 AU. That means it could take 300 years for bother Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 to reach the inner edge of the asteroid cloud and another 30,000 years to cross it.

RELATED ARTICLE: How Did NASA Fix Voyager 1 Program Glitch? Engineers Explain Process

Check out more news and information on Space in Science Times.

Most Popular

1,029-Foot Asteroid To Make Close Approach Toward Earth at Breakneck Speed This Week

Human Jawbone Found in Kitchen Floor Tile Turns Out To Be Remains of Extinct Hominin Species

Eutrophication Explained: Here's What Happens When Bodies of Water Get Overly Enriched With Nutrients

Citizen Scientists Identify New Sample of Over 1,000 Hidden Asteroids in Hubble’s Archival Data

Dangerous Monkeypox Virus Strain Spreads Through Sex, Raises Fears of a Global Outbreak

Latest stories.

2-Year-Old Baby Orca Returns to Ocean a Month After Circling a Canadian Lagoon Where Its Mother Died

NASA’s TESS Mission Spots Its First Free-Floating Planet Using ‘Rogue-Hunting’ Concept From Einstein

4-Legged Robot Shows How Gait Transitions Occur in Animals

Distributed X-Chromosome Inactivation May Protect Girls From Autism Inherited From Their Father, Study Reveals

Wall Running Under Moon-Like Gravity Exerts Forces Similar to Those Experienced by Runners on Earth

Subscribe to the science times.

Sign up for our free newsletter for the Latest coverage!

Recommended Stories

‘Morbid’ Alien Theory: Extraterrestrials Haven’t Contacted Humans As They’re Destroyed by Gamma-Ray Bursts

Cosmic Monsters Create Intersections That Lead To Stellar-Mass Black Holes Collisions

Is Eating Dog Food Safe For Humans? What Happens When You Eat It?

- Science Notes Posts

- Contact Science Notes

- Todd Helmenstine Biography

- Anne Helmenstine Biography

- Free Printable Periodic Tables (PDF and PNG)

- Periodic Table Wallpapers

- Interactive Periodic Table

- Periodic Table Posters

- How to Grow Crystals

- Chemistry Projects

- Fire and Flames Projects

- Holiday Science

- Chemistry Problems With Answers

- Physics Problems

- Unit Conversion Example Problems

- Chemistry Worksheets

- Biology Worksheets

- Periodic Table Worksheets

- Physical Science Worksheets

- Science Lab Worksheets

- My Amazon Books

Oort Cloud Facts and Location

The Oort Cloud is a hypothetical shell of icy objects surrounding our solar system. Also known as the Öpik–Oort cloud, it’s named after Jan Oort and Ernst Öpik, the astronomers who first postulated its existence. The Oort Cloud is a part of our solar system that is still largely theoretical due to its extreme distance and the small size of its constituent objects. It is so far away that no spacecraft have explored it yet.

- The Oort Cloud forms a bubble of icy objects around the solar system.

- The Sun, planets, asteroid belt, and Kuiper Belt are all enclosed within the Oort Cloud.

- Like the asteroid belt and Kuiper Belt, the Oort Cloud contains remnants from the formation of the solar system.

- The cloud contains millions of comets and possibly some dwarf planets.

- Voyager 1 will be the first craft to reach the Oort Cloud, around 300 years from now.

Distance from the Sun and Earth

The Oort Cloud begins at a distance of approximately 2,000 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun and extends outwards to about 100,000-200,000 AU. For comparison, 1 AU is the average distance from the Sun to the Earth, approximately 93 million miles (150 million kilometers). Thus, the Oort Cloud is about 2000 to 100,000 times further away than the distance from the Earth to the Sun.

Discovery and Naming

The region was first postulated by Estonian astronomer Ernst Öpik in 1932. However, takes its name for Dutch astronomer Jan Oort, who independently proposed its existence in 1950. The proposal offered an explanation for the existence of long-period comets. These are comets with orbits that take them far beyond the known boundaries of the solar system.

Shape, Structure, and Composition

Researchers believe the Oort Cloud has a spherical or toroidal shape, extending in all directions from the Sun. This is quite distinct from the flat disk shape of the part of the solar system where the planets reside. Scientists generally agree that the Oort Cloud consists of two connected regions: the outer Oort Cloud and the inner Oort Cloud (sometimes called Hills Cloud or the Oort Hills cloud).

The inner Oort Cloud or Hills Cloud is disc-shaped and lies closer to the rest of the solar system. It starts at a distance of approximately 2,000 to 5,000 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun and extends up to 10,000 to 20,000 AU. The objects in this region feel the influence of the gravity of the gas giant planets.

The outer Oort Cloud is the larger spherical component and extends from the edge of the inner Oort Cloud out to at least 50,000 to 100,000 AU. The comets from this region approach the Sun from any direction, which is why scientists believe the outer cloud is spherical. The objects in the outer cloud are loosely bound to the Sun, and their orbits feel the gravity of nearby stars and the Milky Way galaxy itself.

The cloud likely consists mostly of icy planetesimals. These are small objects made from dust and ice, which are remnants from the formation of the solar system. These planetesimals are so far from the Sun that they react to perturbations from nearby stars or gas clouds.

Origin of the Oort Cloud

The Oort Cloud is probably a remnant of the original protoplanetary disk that formed around the Sun approximately 4.6 billion years ago. It’s believed that the planetesimals within the Oort Cloud started out closer to the Sun but were flung outwards by the gravitational interactions with young planets. As these planetesimals moved further from the Sun, they entered a region of space where the Sun’s gravitational influence is weak.

Comparing the Oort Cloud and the Kuiper Belt

The Oort Cloud and the Kuiper Belt are two separate regions of the solar system, each populated by small, icy bodies.

- Location and Structure: The Kuiper Belt is much closer to the Sun, extending from the orbit of Neptune (at 30 AU) to about 50 AU. Unlike the spherical Oort Cloud, the Kuiper Belt is a disk-shaped region in the plane of the solar system.

- Composition: Both the Oort Cloud and the Kuiper Belt contain small, icy bodies.

- Comets: Both regions are sources of the comets we see in our sky. Short-period comets (with orbits less than 200 years) originate from the Kuiper Belt, while long-period comets (with orbits longer than 200 years) come from the Oort Cloud.

Comets and Other Bodies in the Oort Cloud

The Oort Cloud contains billions or even trillions of comets. Other possible objects in the Oort Cloud might include dwarf planets , similar to Pluto. The existence of such bodies remains purely speculative at this point.

Studying the Oort Cloud

Studying the Oort Cloud provides valuable insight into the early solar system. As a primordial group of objects, the Oort Cloud offers clues to the processes of planet formation and the original properties of the protoplanetary disk.

Furthermore, studying the Oort Cloud helps scientists better understand the dynamics of comets and the risks they pose to Earth. As comets from the Oort Cloud have orbits that potentially intersect with the Earth’s, understanding their behavior is crucial for predicting potential comet impacts.

Reaching the Oort Cloud

Reaching the Oort Cloud with a spacecraft presents a formidable challenge. Even at the incredible speed of the Voyager spacecraft (traveling at more than 35,000 mph or about 56,000 kph), it takes over 300 years to reach the inner edge of the Oort Cloud and up to 30,000 years to pass through it.

- Emelyanenko, V. V.; Asher, D. J.; Bailey, M. E. (2007). “The fundamental role of the Oort Cloud in determining the flux of comets through the planetary system”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society . 381 (2): 779–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.12269.x

- Fernández, Julio A. (1997). “The Formation of the Oort Cloud and the Primitive Galactic Environment”. Icarus . 219 (1): 106–119. doi: 10.1006/icar.1997.5754

- Levison, Harold F.; Donnes, Luke (2007). “Comet Populations and Cometary Dynamics”. In Lucy Ann Adams McFadden; Lucy-Ann Adams; Paul Robert Weissman; Torrence V. Johnson (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Solar System (2nd ed.). Amsterdam; Boston: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-088589-3.

- Oort, Jan (1950). “The structure of the cloud of comets surrounding the Solar System and a hypothesis concerning its origin”. Bulletin of the Astronomical Institutes of the Netherlands . 11: 91–110.

- Öpik, Ernst Julius (1932). “Note on Stellar Perturbations of Nearby Parabolic Orbits”. Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences . 67 (6): 169–182. doi: 10.2307/20022899

Related Posts

We have completed maintenance on Astronomy.com and action may be required on your account. Learn More

- Login/Register

- Solar System

- Exotic Objects

- Upcoming Events

- Deep-Sky Objects

- Observing Basics

- Telescopes and Equipment

- Astrophotography

- Space Exploration

- Human Spaceflight

- Robotic Spaceflight

- The Magazine

Mysteries of the Oort cloud at the edge of our solar system

The Oort cloud represents the very edges of our solar system. The thinly dispersed collection of icy material starts roughly 200 times farther away from the sun than Pluto and stretches halfway to our sun’s nearest starry neighbor, Alpha Centauri. We know so little about it that its very existence is theoretical — the material that makes up this cloud has never been glimpsed by even our most powerful telescopes, except when some of it breaks free.

“For the foreseeable future, the bodies in the Oort cloud are too far away to be directly imaged,” says a spokesperson from NASA. “They are small, faint, and moving slowly.”

Aside from theoretical models, most of what we know about this mysterious area is told from the visitors that sometimes swing our way every 200 years or more — long period comets. “[The comets] have very important information about the origin of the solar system,” says Jorge Correa Otto, a planetary scientist the Argentina National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET).

A Faint Cloud, in Theory

The Oort cloud’s inner edge is believed to begin roughly 1,000 to 2,000 astronomical units from our sun. Since an astronomical unit is measured as the distance between the Earth and the sun, this means it’s at least a thousand times farther from the sun than we are. The outer edge is thought to go as far as 100,000 astronomical units away, which is halfway to Alpha Centauri. “Most of our knowledge about the structure of the Oort cloud comes from theoretical modeling of the formation and evolution of the solar system,” the NASA spokesperson says.

While there are many theories about its formation and existence, many believe that the Oort cloud was created when many of the planets in our solar system were formed roughly 4.6 billion years ago. Similar to the way the Asteroid Belt between Mars and Jupiter sprung to life, the Oort cloud likely represents material left over from the formation of giant planets like Jupiter, Neptune, Uranus and Saturn. The movements of these planets as they came to occupy their current positions pushed that material past Neptune’s orbit, Correa Otto says.

Another recent study holds that some of the material in the Oort cloud may be gathered as our sun “steals comets” orbiting other stars . Basically, the theory is that comets with extremely long distances around our neighboring stars get diverted when coming into closer range to our sun, at which point they stick around in the Oort cloud.

The composition of the icy objects that form the Oort cloud is thought to be similar to that of the Kuiper Belt, a flat, disk-shaped area beyond the orbit of Neptune we know more about. The Kuiper Belt also consists of icy objects leftover from planet formation in the early history of our solar system. Pluto is probably the most famous object in this area, though NASA’s New Horizons space probe flew by another double-lobed object in 2019 called Arrokoth — currently the most distant object in our solar system explored up close, according to NASA.

“Bodies in the Oort cloud, Kuiper belt, and the inner solar system are all believed to have formed together, and gravitational dynamics in the solar system kicked some of them out,” the NASA spokesperson says.

Visitors from the Edge of our Solar System

Estonian philosopher Ernst Öpik first theorized that long-period comets might come from an area at the edge of our solar system. Then, Dutch astronomer Jan Oort predicted the existence of his cloud in the 1950s to better understand the paradox of long-period comets.

Oort’s theory was that comets would eventually strike the sun or a planet, or get ejected from the solar system when coming into closer contact with the strong orbit of one of those large bodies. Furthermore, the tails that we see on comets are made of gasses burned off from the sun’s radiation. If they made too many passes close to the sun, this material would have burned off. So they must not have spent all their existence in their current orbits. “Occasionally, Oort cloud bodies will get kicked out of their orbits, probably due to gravitational interactions with other Oort cloud bodies, and come visit the inner solar system as comets,” the NASA spokesperson says.

Correa Otto says that the direction of comets also supports the Oort cloud’s spherical shape. If it was shaped more like a disk, similar to the Kuiper Belt, comets would follow a more predictable direction. But the comets that pass by us come from random directions. As such, it seems the Oort cloud is more of a shell or bubble around our solar system than a disk like the Kuiper Belt. These long-period comets include C/2013 A1 Siding Spring, which passed close to Mars in 2014 and won’t be seen again for another 740,000 years.

“No object has been observed in the distant Oort cloud itself, leaving it a theoretical concept for the time being. But it remains the most widely-accepted explanation for the origin of long-period comets,” NASA says .

The Oort cloud, if it indeed exists, likely isn’t unique to our own solar system. Correa Otto says that some astronomers believe these clouds exist around many solar systems. The trouble is, we can’t even yet see our own, let alone those of our neighboring systems. The Voyager 1 spacecraft is headed in that direction — it’s projected to reach the inner edge of our Oort cloud in roughly 300 years. Unfortunately, Voyager will have long since stopped working.

“Even if it did [still work], the Sun’s light is so faint, and the distances so vast, that it would be unlikely to fly close enough to something to image it,” the NASA spokesperson says. In other words, it would be difficult to tell you’re in the Oort cloud even if you were right inside it.

A collision with something the size of Arizona could have formed half of Pluto’s ‘heart’

Evidence grows that meteorites, comets could have brought essentials of life to early Earth

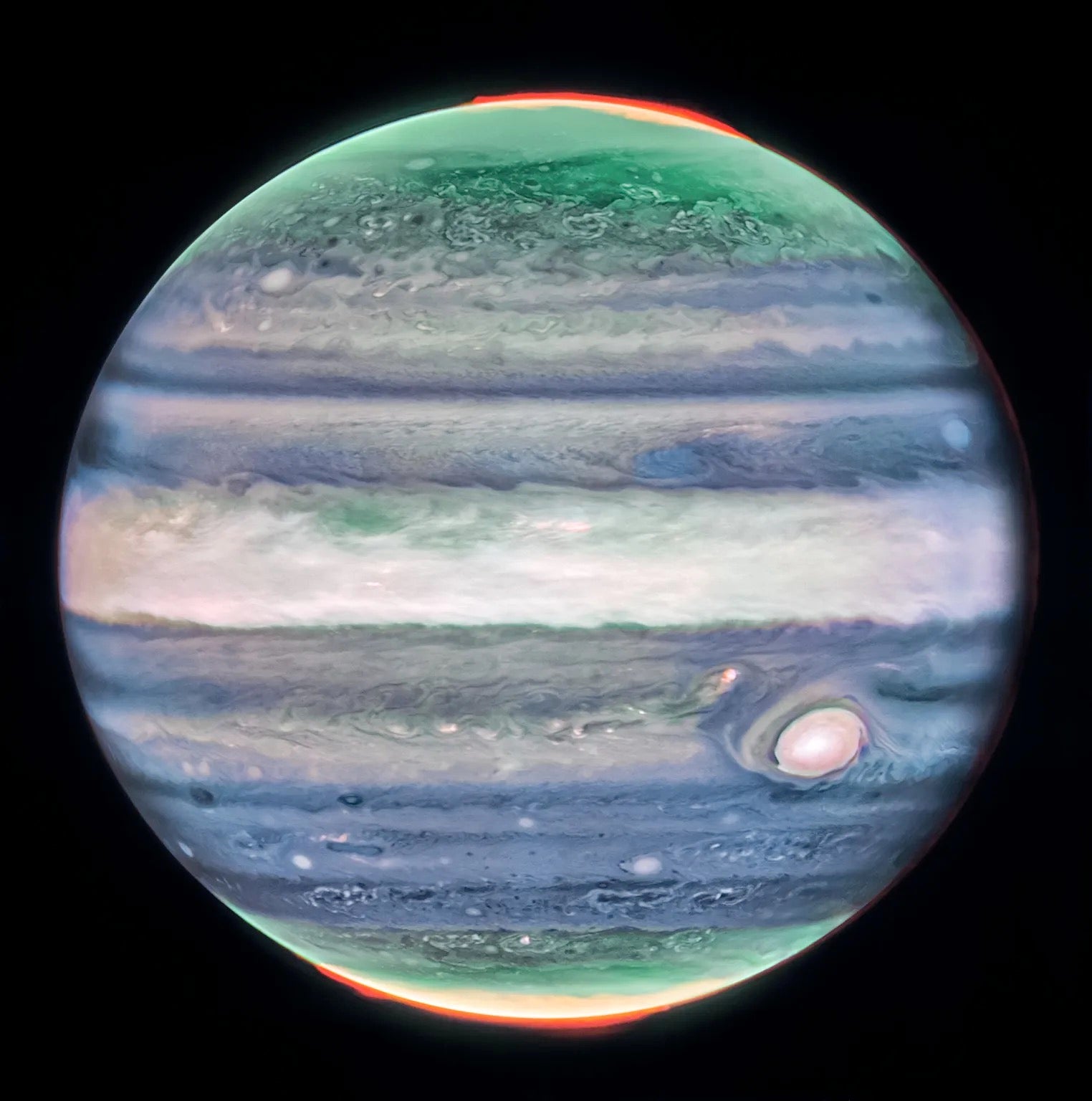

Jupiter: Size, distance from the Sun, orbit

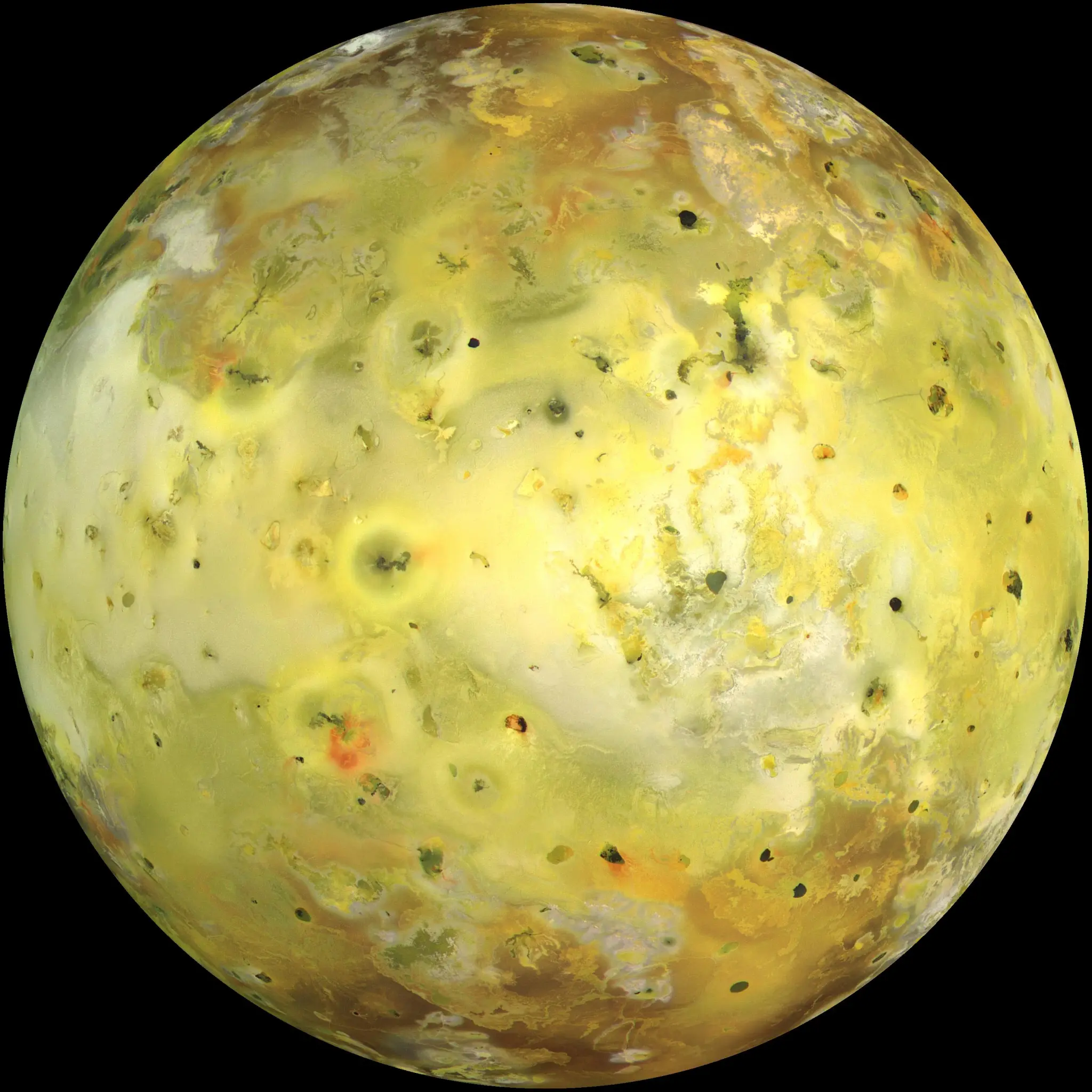

Jupiter’s moon Io has likely been active for our solar system’s entire history

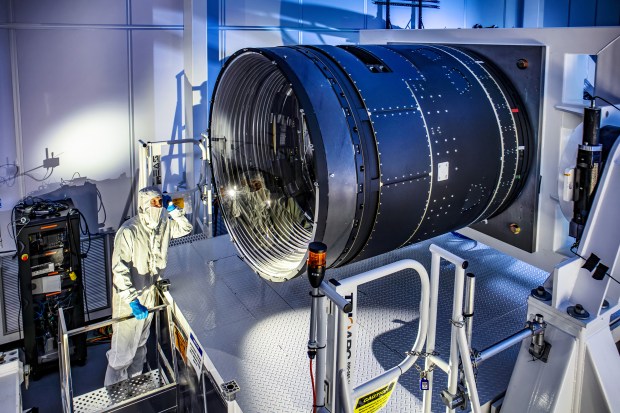

The largest digital camera ever made for astronomy is done

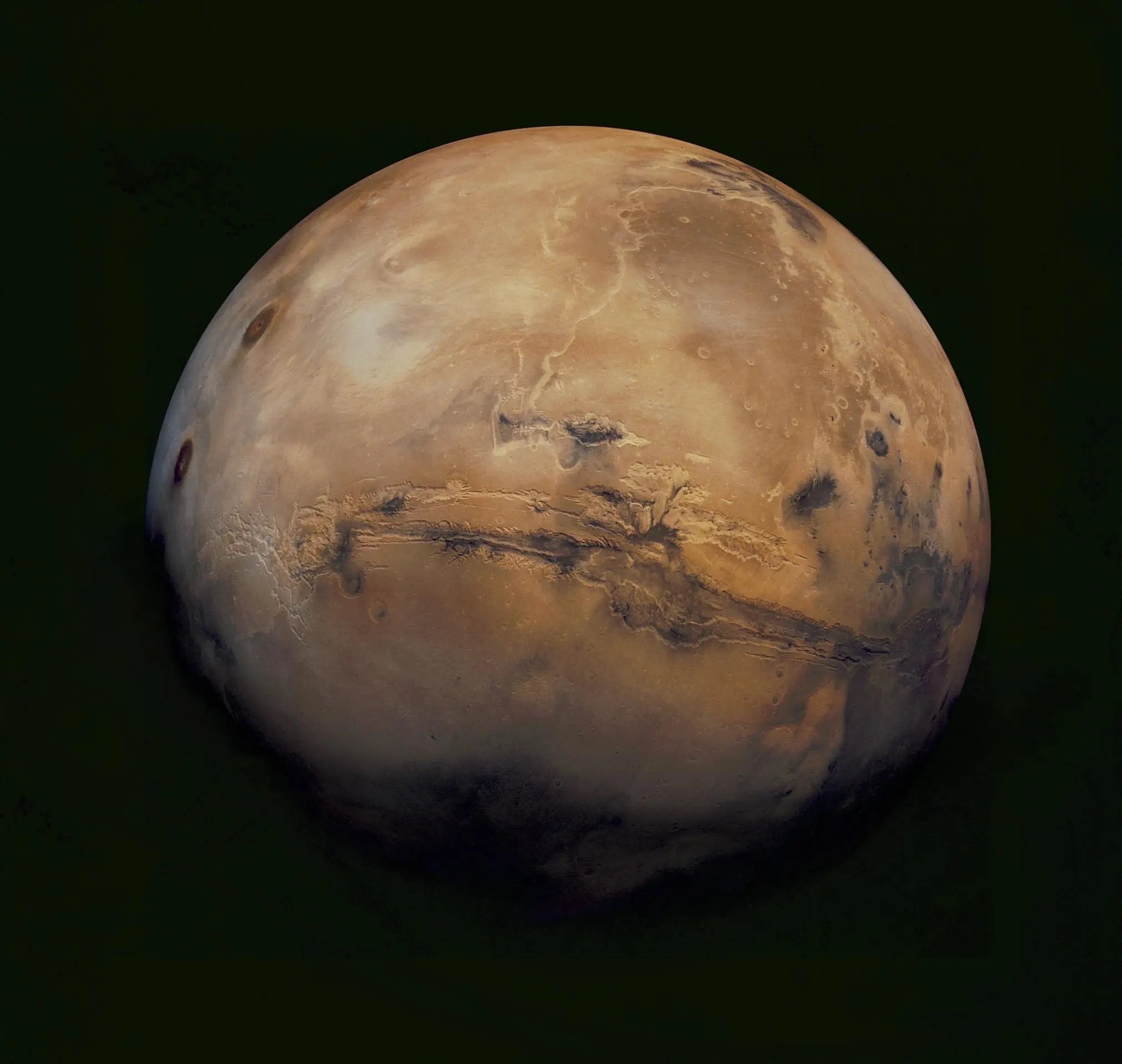

NASA seeks faster, cheaper options to return Mars samples to Earth

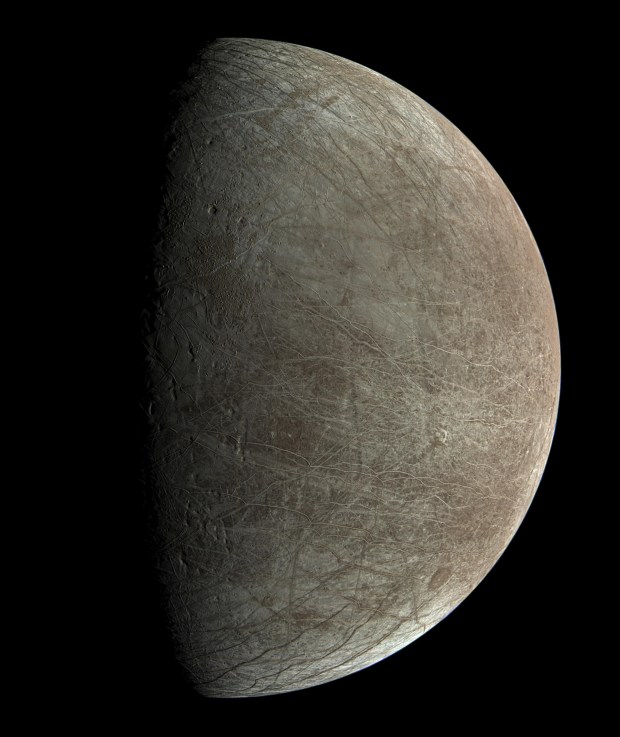

Circular patterns on Europa suggest how deep a lively ocean may be

When did we realize that Earth orbits the Sun?

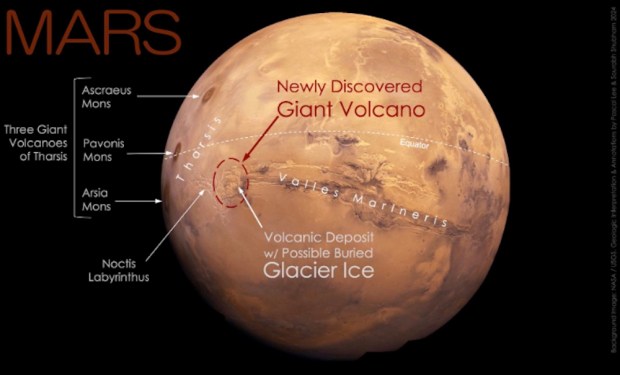

Scientists discover an ancient volcano near the martian equator

NASA’s Voyager 1 Resumes Sending Engineering Updates to Earth

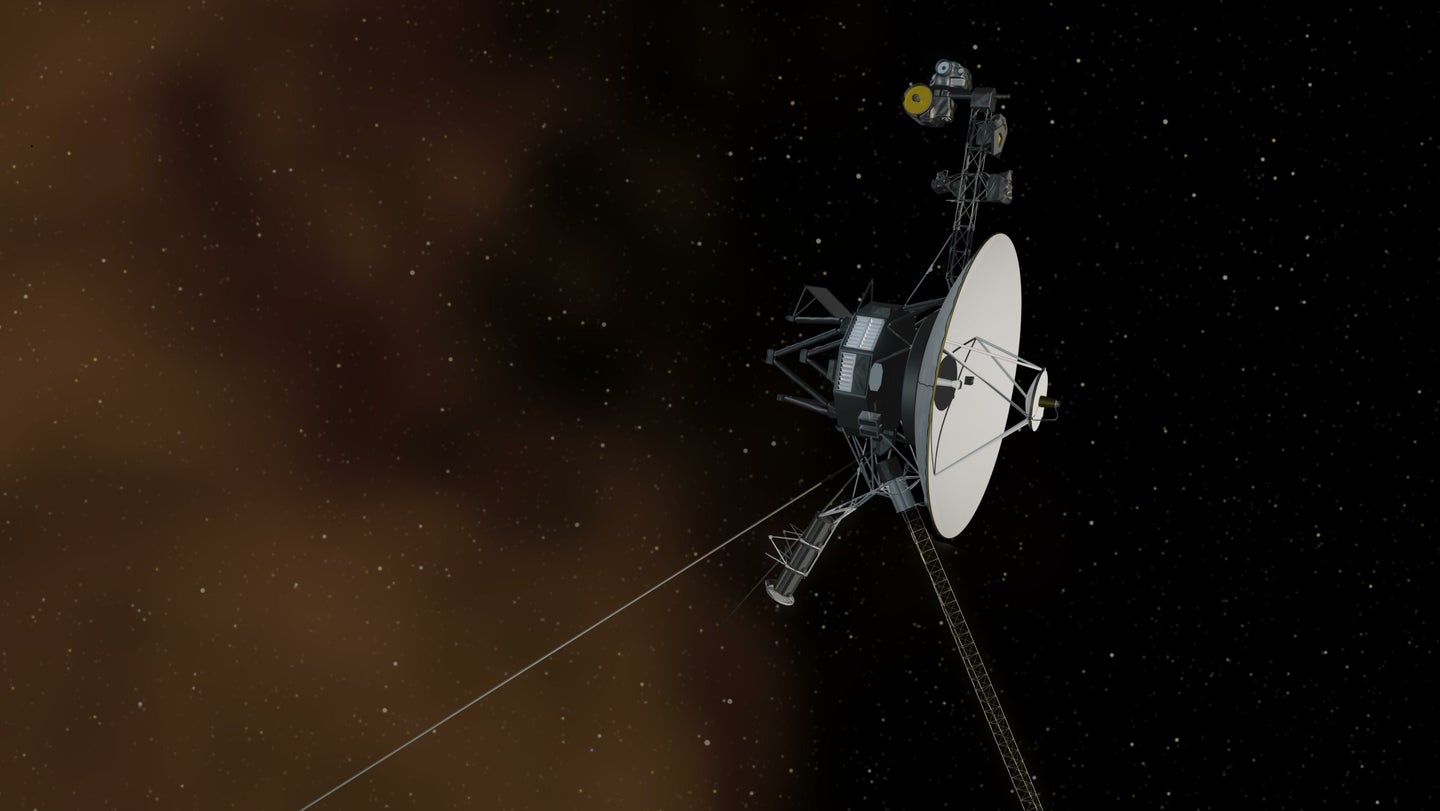

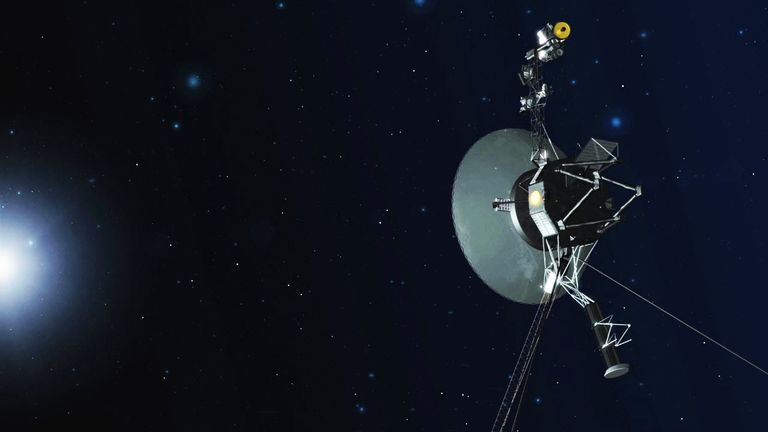

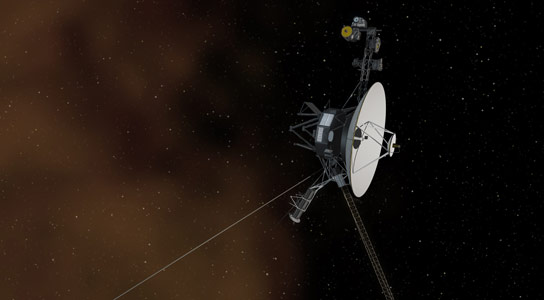

NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft is depicted in this artist’s concept traveling through interstellar space, or the space between stars, which it entered in 2012.

After some inventive sleuthing, the mission team can — for the first time in five months — check the health and status of the most distant human-made object in existence.

For the first time since November , NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft is returning usable data about the health and status of its onboard engineering systems. The next step is to enable the spacecraft to begin returning science data again. The probe and its twin, Voyager 2, are the only spacecraft to ever fly in interstellar space (the space between stars).

Voyager 1 stopped sending readable science and engineering data back to Earth on Nov. 14, 2023, even though mission controllers could tell the spacecraft was still receiving their commands and otherwise operating normally. In March, the Voyager engineering team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California confirmed that the issue was tied to one of the spacecraft’s three onboard computers, called the flight data subsystem (FDS). The FDS is responsible for packaging the science and engineering data before it’s sent to Earth.

After receiving data about the health and status of Voyager 1 for the first time in five months, members of the Voyager flight team celebrate in a conference room at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory on April 20.

The team discovered that a single chip responsible for storing a portion of the FDS memory — including some of the FDS computer’s software code — isn’t working. The loss of that code rendered the science and engineering data unusable. Unable to repair the chip, the team decided to place the affected code elsewhere in the FDS memory. But no single location is large enough to hold the section of code in its entirety.

So they devised a plan to divide the affected code into sections and store those sections in different places in the FDS. To make this plan work, they also needed to adjust those code sections to ensure, for example, that they all still function as a whole. Any references to the location of that code in other parts of the FDS memory needed to be updated as well.

The team started by singling out the code responsible for packaging the spacecraft’s engineering data. They sent it to its new location in the FDS memory on April 18. A radio signal takes about 22 ½ hours to reach Voyager 1, which is over 15 billion miles (24 billion kilometers) from Earth, and another 22 ½ hours for a signal to come back to Earth. When the mission flight team heard back from the spacecraft on April 20, they saw that the modification worked: For the first time in five months, they have been able to check the health and status of the spacecraft.

Get the Latest News from the Final Frontier

During the coming weeks, the team will relocate and adjust the other affected portions of the FDS software. These include the portions that will start returning science data.

Voyager 2 continues to operate normally. Launched over 46 years ago , the twin Voyager spacecraft are the longest-running and most distant spacecraft in history. Before the start of their interstellar exploration, both probes flew by Saturn and Jupiter, and Voyager 2 flew by Uranus and Neptune.

Caltech in Pasadena, California, manages JPL for NASA.

News Media Contact

Calla Cofield

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

626-808-2469

NASA prepares to power-down Voyager spacecraft after more than 44 years

It is certain that at some point the plutonium powering the probes will decay beyond what is capable of keeping them functional. Some estimate that could be as soon as 2025, while others hope it may be later.

Friday 17 June 2022 12:09, UK

After more than 44 years of travelling farther from Earth than any man-made objects have before, the Voyager spacecraft are entering their very final phase.

Both of the Voyagers were launched from Cape Canaveral in 1977 - with Voyager 2 actually the first to take off - taking advantage of a rare alignment (once every 176 years) of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune to shoot into interstellar space.

They were designed to last five years and study Jupiter and Saturn but remarkably both spacecraft are still functioning despite escaping beyond the hot plasma bubble known as the heliopause that defines the beginning of the edge of our solar system.

Speaking to the magazine Scientific American about powering down the probes, NASA physicist Ralph McNutt said: "We're at 44 and a half years, so we've done 10 times the warranty on the darn things."

Both of the spacecraft are powered by radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) - powered by the heat from decaying spheres of plutonium - although the output of these RTGs is decreasing by about four watts every year.

This means instruments are being turned off one by one.

As of today Voyager 1 only has four functioning instruments left, and Voyager 2 has five.

More on Nasa

Solar storms and Mars: Rare giant explosions on sun's surface could help NASA find out how to live on Red Planet

Voyager 1: NASA's longest-running spacecraft back in touch with Earth after five months of silence

Lyrid meteor shower: How UK stargazers can watch the oldest annual meteor shower

Related Topics:

It is certain that at some point the plutonium powering the spacecraft will decay beyond what is capable of keeping the probes functional. Some estimate that could be as soon as 2025, while others hope it may be later.

But they have surprised NASA's engineers so far, who had expected to start turning Voyager 2's instruments off first, one by one, starting in 2020. Instead, nothing has been switched off since 2008.

"If everything goes really well, maybe we can get the missions extended into the 2030s. It just depends on the power. That's the limiting point," said Linda Spilker, who started working on the Voyager missions before they launched, speaking to Scientific American.

Escaping the solar system

It took Voyager 1 around 36 years to breach the heliopause , and the data it has sent back since then suggests some fascinating qualities about the role of magnetic fields in the universe.

Voyager 2 then passed into interstellar space in 2018 - 41 years after it was launched - breaking through the outer boundary of the heliopause where the hot solar wind meets the cold space known as the interstellar medium.

But space is very, very big and neither of the probes are currently considered to be outside of the solar system. The final boundary is considered to be the Oort Cloud, a collection of small objects still under the influence of the Sun's gravity.

NASA says it will take about 300 years for Voyager 2 to reach the inner edge of the Oort Cloud, and possibly 30,000 years to fly beyond it.

Voyager 1 is currently 14.5 billion miles (23.3bn km) from Earth and it takes 20 light hours and 33 minutes to travel that distance, meaning it takes two days to send a message to the spacecraft and get a response.

Voyager 2 isn't quite so far, only 12 billion miles from the Earth, just under an 18 hours' light distance from us.

Both of the spacecraft carry a gold-plated disc containing multicultural greetings, songs and photographs, in case they one day meet intelligent life - although some astronomers have cautioned that humanity may regret making first contact.

Carl Sagan was a dismissive of this concern: "The fact is, for better or for worse, we have already announced our presence and location to the universe, and continue to do so every day.

"There is a sphere of radio transmission about thirty light years thick expanding outward at the speed of light, announcing to every star it envelops that the earth is full of people.

"Our television programs flood space with signals detectable at enormous distances by instruments not much greater than our own. It is a sobering thought that the first news of us may be the outcome of the Super Bowl," he wrote.

Mysterious data

As recently as last month NASA said its engineers were working on a solving a mystery affecting Voyager 1's telemetry data, although Voyager 2 is continuing to operate normally - albeit with some instruments now turned off for longevity.

The problem probe has an attitude articulation and control system (AACS) that is in charge of the spacecraft's orientation, including keeping its antenna pointed precisely at Earth so it can send data home.

This data is still arriving, suggesting the AACS continues working as intended, but the telemetry data itself is invalid according to NASA. It appears randomly generated or to be not reflecting any possible state the AACS could actually be in, the space agency explained.

"A mystery like this is sort of par for the course at this stage of the Voyager mission," said Suzanne Dodd, project manager for Voyager 1 and 2 at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California.

"The spacecraft are both almost 45 years old, which is far beyond what the mission planners anticipated. We're also in interstellar space – a high-radiation environment that no spacecraft have flown in before.

"So there are some big challenges for the engineering team. But I think if there's a way to solve this issue with the AACS, our team will find it," Ms Dodd added.

On 14 February 1990, as Voyager 1 passed Uranus, it turned back towards the Earth to take a picture of our planet as a tiny dot.

Four years later the astronomer Carl Sagan reflected on the significance of the photograph to an audience at Cornell University, famously coining its name as the "Pale Blue Dot", and giving one of the most widely published speeches of all time.

"Consider again that dot. That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives.

"The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilisation, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every 'superstar', every 'supreme leader', every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there - on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam."

We probably won't see its like again any time soon.

NASA said that while it is possible for the cameras to be turned back on, doing so isn't a priority for the interstellar mission.

The agency added that the picture likely wouldn't be anywhere near as good as the one captured in 1990 either: "It is very dark where the Voyagers are now. While you could still see some brighter stars and some of the planets with the cameras, you can actually see these stars and planets better with amateur telescopes on Earth."

For those who still have hope, NASA cautions that the attempt could be a waste of the probes' dwindling resources: "The computers on the ground that understand the software and analyse the images do not exist anymore.

"The cameras and their heaters have also been exposed for years to the very cold conditions at the deep reaches of our solar system.

"Even if mission managers recreated the computers on the ground, reloaded the software onto the spacecraft and were able to turn the cameras back on, it is not clear that they would work."

Related Topics

The Voyagers Found a Small Surprise in Interstellar Space

The spacecraft are still feeling the sun billions of miles from home.

The missions that humankind has sent farthest into space, a pair of NASA spacecraft called the Voyagers, are billions of miles from Earth. The last time one of them took a picture of its surroundings was in 1990 , after flying by Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune, and Uranus on its way to interstellar space, the mysterious expanse between stars. This far beyond the planets, there’s not much to see.

But there are some things to feel , in the sense that a spacefaring machine can feel something. Even this far out, the sun can still make its presence known.

A team of scientists has detected sudden bursts of cosmic rays around the Voyagers. The bursts, they report, are caused by shock waves emanating from solar eruptions that spew particles out at a million miles an hour. The shock waves take more than a year to reach the Voyagers, but when they do, they excite cosmic-ray electrons nearby. Scientists have observed similar phenomena closer to home, around Earth and our planetary neighbors, but never in interstellar space.

“We’re really discovering that what we thought would be this quiet, pristine interstellar medium is actually disturbed considerably” by the sun, Don Gurnett, a University of Iowa professor emeritus of physics and astronomy, who led the research, told me.

Read: The Voyager mission made the solar system a real place

More than 40 years ago, Gurnett designed and built one of the instruments on the Voyager mission that can sense such things. Voyager 1 crossed into interstellar space in 2012, and Voyager 2 followed in 2018. But the spacecraft actually haven’t left the solar system, despite many headlines over the years claiming that they have. This might seem, at first glance, a little contradictory—how can something exist in the space between stars and within the solar system at the same time? Aren’t those two different things?

From our perspective, interstellar space begins when sun particles can’t go any farther . The sun releases a steady current of high-energy particles in all directions, all the time, and this solar wind encompasses the planets, their moons, and other celestial bodies in a protective bubble called the heliosphere. Scientists had predicted that the breeze would stop where it met the cold particles of the interstellar medium, which is sprinkled with material left behind by supernovas, the deaths of other stars. But they didn’t know exactly where this sphere of the sun’s influence stopped until 2012, when Voyager 1 detected the beginning of a different cosmic environment. “It’s not impossible, but it’s very difficult for solar plasmas to cross that boundary,” Bill Kurth, a research scientist at the University of Iowa and Gurnett’s co-author on the new findings, told me.

Read: It’s easier to leave the solar system than to reach the sun

This is where the Voyagers are, beyond the heliosphere. Kurth once published a commentary in a science journal that said leaving the heliosphere was more or less the same as leaving the solar system. “I was soundly criticized,” he said, laughing. Because while the solar wind blows quite far—120 astronomical units, with a single unit equal to the distance between the Earth and the sun—our star’s influence extends even deeper. Not through warmth, but through gravity.

The sun’s gravity can keep objects in its orbit far beyond where the heliosphere ends. As the Voyagers continue on their journey, eventually they will enter the Oort cloud , a region of icy objects past Pluto. Because those objects are gravitationally bound to the sun, they still count as ours. This is where the solar system truly ends—past the far edge of the Oort cloud, which is somewhere between 10,000 and 100,000 astronomical units away. “Even though Voyager 1’s out and beyond 150 astronomical units, it’s got a long, long ways to go before it gets beyond the Oort cloud,” Kurth says. It will be another few hundred years before the Voyagers reach this region, and tens of thousands more before they pass through to the other side.

Read: When will the Voyagers stop calling home?

When the Voyagers launched in 1977, the notion of doing science so far from our own planet, out in interstellar space, was a distant thought. NASA was focused on swinging by our neighboring planets and moons to collect valuable data and beautiful pictures. After the grand tour, the spacecraft just kept going. In the years since, mission managers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory have turned off various components on the two spacecraft, from science instruments to heaters, rationing every watt of power to keep the machines going. Someday, engineers may be forced to turn off one of the elements that help the spacecraft communicate with Earth, a process that takes about 20 hours each way. It’s a risky move. “If it does work, then we gain two more watts,” Suzanne Dodd, the Voyager project manager, told me last year. “If it doesn’t, then we lose the mission."

For now, the Voyagers still call home with dispatches from the unknown. Engineers expect that the spacecraft will go silent sometime in the next decade. Even then, they will keep moving, unlikely to crash into something in the vastness of space. About 5 billion years from now, when our sun dies in a dramatic process that will engulf our entire planet, the Voyagers will probably still be coasting through the galaxy. “At some point in time, the Voyagers could be the only remaining evidence that Earth was around,” Kurth said.

When the Voyagers do finally leave the solar system, they will enter, for the first time, a stretch of space that does not play by the sun’s rules. There, the sun will become just another star in someone else’s night sky. Its warmth or gravity won’t register, but its glow will radiate for light-years.

- April 24, 2024 | Revolutionizing Renewable Energy: Innovative Salt Battery Efficiently Harvests Osmotic Power

- April 24, 2024 | 30 Times Clearer – Scientists Develop Improved Mid-Infrared Microscope

- April 24, 2024 | Shedding Pounds, Dodging Cancer: The Life-Saving Promise of Bariatric Surgery

- April 24, 2024 | Quantum Computing Meets Genomics: The Dawn of Hyper-Fast DNA Analysis

- April 24, 2024 | Scientists Turn to Venus in the Search for Alien Life

It’s Official – Voyager 1 Has Entered Interstellar Space

By Jia-Rui C. Cook/D.C. Agle, Jet Propulsion Laboratory September 13, 2013

This artist’s concept depicts NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft entering interstellar space, or the space between stars. Interstellar space is dominated by the plasma, or ionized gas, that was ejected by the death of nearby giant stars millions of years ago. The environment inside our solar bubble is dominated by the plasma exhausted by our sun, known as the solar wind. The interstellar plasma is shown with an orange glow similar to the color seen in visible-light images from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope that show stars in the Orion nebula traveling through interstellar space. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

A newly published study has confirmed that the 36-year-old NASA Voyager 1 spacecraft has left our solar system and has entered interstellar space.

NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft officially is the first human-made object to venture into interstellar space. The 36-year-old probe is about 12 billion miles (19 billion kilometers) from our sun.

New and unexpected data indicate Voyager 1 has been traveling for about one year through plasma , or ionized gas, present in the space between stars. Voyager is in a transitional region immediately outside the solar bubble, where some effects from our sun are still evident. A report on the analysis of this new data, an effort led by Don Gurnett and the plasma wave science team at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, is published in Thursday’s edition of the journal Science .

“Now that we have new, key data, we believe this is mankind’s historic leap into interstellar space,” said Ed Stone, Voyager project scientist based at the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena. “The Voyager team needed time to analyze those observations and make sense of them. But we can now answer the question we’ve all been asking — ‘Are we there yet?’ Yes, we are.”

Voyager 1 first detected the increased pressure of interstellar space on the heliosphere, the bubble of charged particles surrounding the sun that reaches far beyond the outer planets, in 2004. Scientists then ramped up their search for evidence of the spacecraft’s interstellar arrival, knowing the data analysis and interpretation could take months or years.

Voyager 1 does not have a working plasma sensor, so scientists needed a different way to measure the spacecraft’s plasma environment to make a definitive determination of its location. A coronal mass ejection, or a massive burst of solar wind and magnetic fields, that erupted from the sun in March 2012 provided scientists the data they needed. When this unexpected gift from the sun eventually arrived at Voyager 1’s location 13 months later, in April 2013, the plasma around the spacecraft began to vibrate like a violin string. On April 9, Voyager 1’s plasma wave instrument detected the movement. The pitch of the oscillations helped scientists determine the density of the plasma. The particular oscillations meant the spacecraft was bathed in plasma more than 40 times denser than what they had encountered in the outer layer of the heliosphere. Density of this sort is to be expected in interstellar space.

This artist’s concept puts solar system distances in perspective. The scale bar is in astronomical units, with each set distance beyond 1 AU representing 10 times the previous distance. One AU is the distance from the sun to the Earth, which is about 93 million miles or 150 million kilometers. Neptune, the most distant planet from the sun, is about 30 AU. Informally, the term “solar system” is often used to mean the space out to the last planet. Scientific consensus, however, says the solar system goes out to the Oort Cloud, the source of the comets that swing by our sun on long time scales. Beyond the outer edge of the Oort Cloud, the gravity of other stars begins to dominate that of the sun. The inner edge of the main part of the Oort Cloud could be as close as 1,000 AU from our sun. The outer edge is estimated to be around 100,000 AU. NASA’s Voyager 1, humankind’s most distant spacecraft, is around 125 AU. Scientists believe it entered interstellar space, or the space between stars, on August 25, 2012. Much of interstellar space is actually inside our solar system. It will take about 300 years for Voyager 1 to reach the inner edge of the Oort Cloud and possibly about 30,000 years to fly beyond it. Alpha Centauri is currently the closest star to our solar system. But, in 40,000 years, Voyager 1 will be closer to the star AC +79 3888 than to our own sun. AC +79 3888 is actually traveling faster toward Voyager 1 than the spacecraft is traveling toward it. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

The plasma wave science team reviewed its data and found an earlier, fainter set of oscillations in October and November 2012. Through extrapolation of measured plasma densities from both events, the team determined Voyager 1 first entered interstellar space in August 2012.

“We literally jumped out of our seats when we saw these oscillations in our data – they showed us the spacecraft was in an entirely new region, comparable to what was expected in interstellar space, and totally different than in the solar bubble,” Gurnett said. “Clearly we had passed through the heliopause, which is the long-hypothesized boundary between the solar plasma and the interstellar plasma.”

The new plasma data suggested a timeframe consistent with abrupt, durable changes in the density of energetic particles that were first detected on August 25, 2012. The Voyager team generally accepts this date as the date of interstellar arrival. The charged particle and plasma changes were what would have been expected during a crossing of the heliopause.

“The team’s hard work to build durable spacecraft and carefully manage the Voyager spacecraft’s limited resources paid off in another first for NASA and humanity,” said Suzanne Dodd, Voyager project manager, based at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California. “We expect the fields and particles science instruments on Voyager will continue to send back data through at least 2020. We can’t wait to see what the Voyager instruments show us next about deep space.”

Voyager 1 and its twin, Voyager 2, were launched 16 days apart in 1977. Both spacecraft flew by Jupiter and Saturn . Voyager 2 also flew by Uranus and Neptune . Voyager 2, launched before Voyager 1, is the longest continuously operated spacecraft. It is about 9.5 billion miles (15 billion kilometers) away from our sun.

Voyager mission controllers still talk to or receive data from Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 every day, though the emitted signals are currently very dim, at about 23 watts — the power of a refrigerator light bulb. By the time the signals get to Earth, they are a fraction of a billion-billionth of a watt. Data from Voyager 1’s instruments are transmitted to Earth typically at 160 bits per second, and captured by 34- and 70-meter NASA Deep Space Network stations. Traveling at the speed of light, a signal from Voyager 1 takes about 17 hours to travel to Earth. After the data are transmitted to JPL and processed by the science teams, Voyager data are made publicly available.

“Voyager has boldly gone where no probe has gone before, marking one of the most significant technological achievements in the annals of the history of science, and adding a new chapter in human scientific dreams and endeavors,” said John Grunsfeld, NASA’s associate administrator for science in Washington. “Perhaps some future deep space explorers will catch up with Voyager, our first interstellar envoy, and reflect on how this intrepid spacecraft helped enable their journey.”

Scientists do not know when Voyager 1 will reach the undisturbed part of interstellar space where there is no influence from our sun. They also are not certain when Voyager 2 is expected to cross into interstellar space, but they believe it is not very far behind.

JPL built and operates the twin Voyager spacecraft. The Voyagers Interstellar Mission is a part of NASA’s Heliophysics System Observatory, sponsored by the Heliophysics Division of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. NASA’s Deep Space Network, managed by JPL, is an international network of antennas that supports interplanetary spacecraft missions and radio and radar astronomy observations for the exploration of the solar system and the universe. The network also supports selected Earth-orbiting missions.

The cost of the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 missions – including launch, mission operations, and the spacecraft’s nuclear batteries, which were provided by the Department of Energy – is about $988 million through September.

For a sound file of the oscillations detected by Voyager in interstellar space, animations, and other information, visit: http://www.nasa.gov/voyager and http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/interstellarvoyager/ .

For an image of the radio signal from Voyager 1 on February 21 by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory’s Very Long Baseline Array, which links telescopes from Hawaii to St. Croix, visit: http://www.nrao.edu .

Reference: “In Situ Observations of Interstellar Plasma with Voyager 1” by D. A. Gurnett, W. S Kurth, L. F. Burlaga and N. F. Ness, 12 September 2013, Science . DOI: 10.1126/science.1241681

More on SciTechDaily

Megalodon – The Largest Shark That Ever Lived – Could Eat Prey the Size of Entire Killer Whales

NASA’s Terra Satellite Images California’s Kincade Fire Burn Scar From Space

Preliminary Data Suggests Mixing COVID-19 Vaccines Increases Frequency of Adverse Reactions

NASA’s OSIRIS-REx Spacecraft Discovers Water on Asteroid Bennu

Earth and Mars Were Formed From Collisions of Large Bodies Made of Inner Solar System Material

Astronomers create first full 3d model of eta carinae nebula.

Supercomputer Simulations Reveal the Violent Birth of Neutron Stars

São Tomé Island Has Two Species of Caecilians Found Nowhere Else on Earth

1 comment on "it’s official – voyager 1 has entered interstellar space".

you so much for this. I was into this issue and tired to tinker around to check if its possible but couldnt get it done. Now that i have seen the way you did it, thanks guys with regards

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Email address is optional. If provided, your email will not be published or shared.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Well, hello, Voyager 1! The venerable spacecraft is once again making sense

Nell Greenfieldboyce

Members of the Voyager team celebrate at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory after receiving data about the health and status of Voyager 1 for the first time in months. NASA/JPL-Caltech hide caption

Members of the Voyager team celebrate at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory after receiving data about the health and status of Voyager 1 for the first time in months.

NASA says it is once again able to get meaningful information back from the Voyager 1 probe, after months of troubleshooting a glitch that had this venerable spacecraft sending home messages that made no sense.

The Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 probes launched in 1977 on a mission to study Jupiter and Saturn but continued onward through the outer reaches of the solar system. In 2012, Voyager 1 became the first spacecraft to enter interstellar space, the previously unexplored region between the stars. (Its twin, traveling in a different direction, followed suit six years later.)

Voyager 1 had been faithfully sending back readings about this mysterious new environment for years — until November, when its messages suddenly became incoherent .

NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft is talking nonsense. Its friends on Earth are worried

It was a serious problem that had longtime Voyager scientists worried that this historic space mission wouldn't be able to recover. They'd hoped to be able to get precious readings from the spacecraft for at least a few more years, until its power ran out and its very last science instrument quit working.

For the last five months, a small team at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California has been working to fix it. The team finally pinpointed the problem to a memory chip and figured out how to restore some essential software code.

"When the mission flight team heard back from the spacecraft on April 20, they saw that the modification worked: For the first time in five months, they have been able to check the health and status of the spacecraft," NASA stated in an update.

The usable data being returned so far concerns the workings of the spacecraft's engineering systems. In the coming weeks, the team will do more of this software repair work so that Voyager 1 will also be able to send science data, letting researchers once again see what the probe encounters as it journeys through interstellar space.

After a 12.3 billion-mile 'shout,' NASA regains full contact with Voyager 2

- interstellar mission

Confirmed: Voyager 1 in Interstellar Space

New data collected by NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft have helped scientists confirm that the far-flung probe is indeed cruising through interstellar space, the researchers say.

Voyager 1 made headlines around the world last year when mission scientists announced that the probe had apparently left the heliosphere — the huge bubble of charged particles and magnetic fields surrounding the sun — in August 2012.

They came to this conclusion after analyzing measurements Voyager 1 made in the wake of a powerful solar eruption known as a coronal mass ejection, or CME. The shock wave from this CME caused the particles around Voyager 1 to vibrate substantially, allowing mission scientists to calculate the density of the probe's surroundings (because denser plasma oscillates faster.) [ Photo Timeline: Voyager 1's Trek to Interstellar Space ]

This density was much higher than that observed in the outer layers of the heliosphere, allowing team members to conclude that Voyager 1 had entered a new cosmic realm. ( Instellar space is emptier than areas near Earth, but the solar system thins out dramatically near the heliosphere's edge.)

The CME in question erupted in March 2012, and its shock wave reached Voyager 1 in April 2013. After these data came in, the team dug up another, much smaller CME-shock event from late 2012 that had initially gone unnoticed. By combining these separate measurements with knowledge of Voyager 1's cruising speed, the researchers were able to trace the probe's entry into interstellar space to August 2012.

And now mission scientists have confirmation, in the form of data from a third CME shock, which Voyager 1 observed in March of this year, NASA officials announced Monday (July 7).

"We're excited to analyze these new data," Don Gurnett of the University of Iowa, the principal investigator of Voyager 1's plasma wave instrument, said in a statement . "So far, we can say that it confirms we are in interstellar space."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Interstellar space begins where the heliosphere ends. But by some measures, Voyager 1 remains inside the solar system, which is surrounded by a shell of comets known as the Oort Cloud.

While it's unclear exactly how far away from Earth the Oort Cloud lies, Voyager 1 won't get there for quite a while. NASA scientists have estimated that Voyager 1 will emerge from the Oort Cloud in 14,000 to 28,000 years.

The craft launched in September 1977, about two weeks after its twin, Voyager 2. The probes embarked upon a "grand tour" of the outer solar system, giving the world some its first good looks at Jupiter , Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and the moons of these planets.

Like Voyager 1, Voyager 2 is still active and operational. It took a different route through the solar system and is expected to follow its twin into interstellar space a few years from now.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+ . Follow us @Spacedotcom , Facebook or Google+ . Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.

China to launch sample-return mission to the moon's far side on May 3

Mars exploration, new rockets and more: Interview with ESA chief Josef Aschbacher

Evidence for Planet 9 found in icy bodies sneaking past Neptune

Most Popular

- 2 NASA crew announced for simulated Mars mission next month

- 3 NASA's Viper moon rover gets its 'neck' and 'head' installed for mission later this year

- 4 China releases world's most detailed moon atlas (video)

- 5 What would happen if the moon disappeared?

April 22, 2024

After Months of Gibberish, Voyager 1 Is Communicating Well Again

NASA scientists spent months coaxing the 46-year-old Voyager 1 spacecraft back into healthy communication

By Meghan Bartels

NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft is depicted in this artist’s concept traveling through interstellar space, or the space between stars, which it entered in 2012.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

After months of nonsensical transmissions from humanity’s most distant emissary, NASA’s iconic Voyager 1 spacecraft is finally communicating intelligibly with Earth again.

Voyager 1 launched in 1977 , zipped past Jupiter and Saturn within just a few years and has been trekking farther from our sun ever since; the craft crossed into interstellar space in 2012. But in mid-November 2023 Voyager 1’s data transmissions became garbled , sending NASA engineers on a slow quest to troubleshoot the distant spacecraft. Finally, that work has paid off, and NASA has clear information on the probe’s health and status, the agency announced on April 22.

“It’s the most serious issue we’ve had since I’ve been the project manager, and it’s scary because you lose communication with the spacecraft,” said Suzanne Dodd, Voyager project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in an interview with Scientific American when the team was still tracking down the issue.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The Voyager 1 spacecraft is a scientific legend : It discovered that Jupiter’s moon Io, far from being a dead world like our own companion, is instead a supervolcanic world . The craft’s data suggested that Saturn’s moon Titan might have liquid on its surface. And for more than a decade, Voyager 1 has given scientists a glimpse at what space looks like beyond the influence of our sun.

Yet its long years in the harsh environment of space have done a number on the probe, which was designed to last just four years. In particular, degraded performance and low power supplies have forced NASA to turn off six of its 10 instruments, and its communication has gotten even spottier than can be explained by the fact that cosmic mechanics mean a signal takes nearly one Earth day to travel between humans and the probe.

When the latest communications glitch occurred last fall, scientists could still send signals to the distant probe, and they could tell that the spacecraft was operating. But all they got from Voyager 1 was gibberish—what NASA described in December 2023 as “a repeating pattern of ones and zeros.” The team was able to trace the issue back to a part of the spacecraft’s computer system called the flight data subsystem, or FDS, and identified that a particular chip within that system had failed.