What Native Hawaiians want you to know before your visit

Aug 5, 2022 • 10 min read

Women headed to the ocean to go surfing in Kailua, HI,

With the sharp rebound in tourism in Hawai'i, writer and Native Hawaiian Savannah Dagupion wrote for us about how Indigenous Hawaiians view the rebound in tourism and what they want tourists who visit the islands to know before arriving. At request, we've used native spellings in this article.

Hawaiʻi’s beauty, blissful weather, majestic mountains and inviting beaches are all what make the islands a popular tourist destination. But when the global pandemic halted tourism, residents saw the islands’ beauty in a new light.

Kapulani Antonio, a Hawaiian studies educator, was awed by her experiences of the islands just two years ago.

“[During the pandemic], the roads were not clogged with tourist cars,” she says. “Then you go to the beach, and it’s not crowded at all – and there’s no film on the water from all the sun tan lotion. It just seemed cleaner. It reminded me of when I was a kid. It was as if you could hear the elements speaking to you again.”

But that only lasted for a few months. Tourism rebounded strongly, and it did so in ways that many Native Hawaiians felt mirrored the colonial past of the islands. Now, they’re trying to raise awareness among travelers through social media and design a more authentic and sustainable future for the tourism industry.

The rebound of tourists to the islands

On October 15, 2020, Hawaiʻi launched the Safe Travels program, which allowed out-of-state visitors to bypass quarantine with a negative COVID-19 test. Tourists from the continent, unable to travel abroad, trickled into Hawaiʻi. The state saw a spike in COVID-19 cases.

Some used "work from home" as an opportunity to move to Hawaiʻi during the pandemic, which increased the cost of living and priced Native Hawaiians and locals out of their communities. According to real estate firm Locations Hawaii , the median sale price of a single-family home on Oʻahu was $1.1 million in June 2022. That's up from $835,000 just three years earlier .

Because 90% of Hawaiʻi’s goods are imported, many locals worried that the finite amount of resources wouldn’t sustain residents and the increasing number of tourists – especially during the pandemic. Local families grew frustrated that they had to watch their children’s soccer games from the car due to COVID-19 restrictions, while tourists lined the beaches to bask in the sun.

Photos and videos of vacations to Hawaiʻi flooded social media feeds . Tourists posted about traveling off the beaten path to “secret” locations, disturbing native environments and forcing rescue teams to be on high-alert. Last year, Honolulu Fire Department officials reported that they averaged two land or ocean rescues a day – a 63% increase over the same period in 2020, when most tourists stayed home.

How Hawai’i grew into a vacation destination

For Native Hawaiians, the behavior of tourists and the way the state handled the pandemic felt eerily familiar.

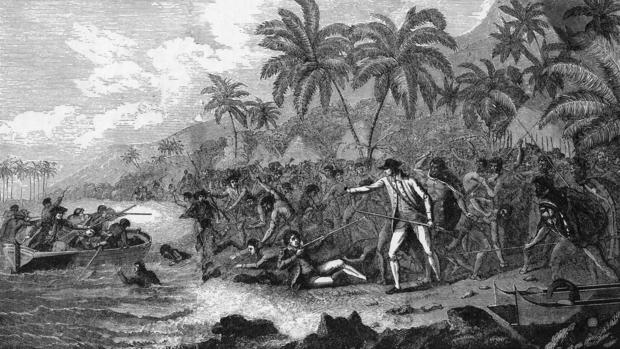

Antonio says it all started with the United States’ overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893, which led to the subsequent annexation of the nation in 1898. Hawaiians fought to maintain political control over their rightful lands; however, the United States couldn’t ignore Hawaiʻi’s strategic military location and fertile lands.

“The way Hawaiians see it is that we are still occupied – that we never gave up our inherent sovereignty and we’re a nation occupied by the United States,” Antonio says.

Hawaiʻi later became a territory in 1900, and then a state on August 21, 1959.

Native Hawaiians raise awareness through social media

Native Hawaiians pushed back on social media with posts about social justice and historical information – drawing attention to ways they saw tourism exploiting and profiting off Indigenous culture, as well as how the crescendo of visitors was hurting Hawaiʻi.

One of the groups that have been particularly active in reminding people about Hawaiʻi’s colonial past is ʻĀina Momona , a non-profit that focuses on land restoration, reclaiming and de-occupying Hawaiian lands and sustainable futures for Hawai’i. The organization has been notable for its Native Hawaiian social justice Instagram page.

According to Julie Au, Education, Research and Outreach director of ʻĀina Momona, when Hawaiian statehood came up for a vote in 1959, Native Hawaiians weren't the ones voting.

Records from the Library of Congress show that in 1893 Indigenous Hawaiians made up 97% of the islands’ population, but by 1923, their numbers dwindled to 16%.

“All of that is linked to tourism because at that time when we became a state, they really started marketing Hawai’i as this paradise vacation destination,” Au says. “So we’re not even a normal state. We’re America’s vacation state.

Why Native Hawaiians want you to arrive educated

Native Hawaiians and locals acknowledge that tourism is inevitable because people will always be drawn to the islands, which is why they have been speaking up about the importance of education and uplifting the lāhui (the Hawaiian nation).

Au says ʻĀina Momona requests that visitors come educated.

“Tourists need to know they are stepping into a place with a long history,” Antonio says. “They need to take kuleana (responsibility) when they come."

Antonio urges visitors to not treat Hawaiʻi as their playground, and see if they can contribute to this place instead of just taking.

"If, after they read up, [and] they decide that Hawaiʻi is not their place, it’s okay. If you come, just be a good steward of the land, have a nice time and then go home. We do have aloha, but you have to act properly," she says.

Native Hawaiians continue to see their percentage of the population – and thus their political voice – drop. Only about 10% of Hawaiʻi’s population is Native Hawaiian, making them a minority in their own home.

Also, with tourism comes development, which has led to the desecration of sacred sites – for example, in 1987, a collection of around 1200 ʻiwi kūpuna (ancestral bones) were exhumed in Honokahua during the excavation for a Ritz-Carlton resort. After an outpouring of Native Hawaiian activism , the resort was pushed further inland. The resort continues to work with those communities to this day.

But to Native Hawaiians, it is still upsetting that the sacred site was disrupted in the first place.

“It all goes back to the beginning when our political control was taken from us. Now we can’t even make decisions that are good for island people,” Antonio says. “[We] have no say in what happens to [our] ʻāina (land).”

Au urges visitors to really consider the ramifications of their vacation.

“People hop on a plane, come here and visit all these sites, drink all of our limited water, and fuel into this capitalist economy that’s building condos for them instead of housing for us and building resorts for them instead of agricultural land for us – and [they’re not seeing] the implications of that,” she says.

What to consider for your visit

If visitors decide it’s their dream to visit Hawaiʻi, Au says it is important to follow protocols. She points to a slogan on a sign in Molokaʻi: visit, spend, go home. She also advises that tourists regulate themselves and tread lightly.

“There’s lots of fun things to do here, but if we’re putting out things that say ‘don’t do this, don’t do that or don’t go here,’ we’d like people to respect that,” she says.

Read more: 'This behavior is unacceptable' - Hawaii visitors warned to stay away from monk seals

Along with obeying rules on the island and respecting locals’ concerns, make sure you practice the principles of Leave No Trace . Don’t take any rocks, sand or other pieces of nature from the islands.

Make sure to adequately plan and prepare for activities like hiking, and behave responsibly to avoid needing rescue crews to come get you. Also, avoid high-foot-traffic areas to prevent erosion and deterioration of trails.

Practice being a good steward of the land by preserving as much of the natural environment as you can. Wear reef-safe sunscreen, respect cultural sites and keep your distance from marine life.

Many scenic roads frequented by tourists are also used by locals. The Road to Hana is a narrow, winding 64.4-mile-long stretch on Maui. Residents have voiced concerns about visitors blocking roads or slowing down to sightsee. Consider taking a tour to limit the amount of vehicle traffic on the road. If you decide to drive the scenic routes, be sure to only pull over where appropriate, and pull over completely. Also, if you notice a local vehicle behind you, pull over and let them pass.

Read More: You'll have to prebook a trip to this Hawaiian state park

Consider giving back, too. Alexa Bader, ʻĀina Momona Communications Director who also runs their Instagram page, recommends that if visitors really care about Hawaiʻi and want to help make a difference, they should donate to Native Hawaiian non-profits .

“Try to research Native groups that are trying to help our islands survive,” she says. “Help all these grassroots.”

Antonio adds that it’s reasonable that Native Hawaiians are upset over the effects of tourism because they have a lot of cultural and historical trauma.

“People have that sense that the haole (foreigner) is bad and that the haole is coming to take from me again,” she says. “It’s up to haole to show us that they’re not here to hurt us. That they’re here to actually learn about our culture. To appreciate and to help. Be an ally to Hawaiians and Hawaiʻi.”

In Native Hawaiian culture, land has great significance, so to see their homeland devastated by development, tourism or the government, Antonio says it’s ʻeha (it hurts).

“Because we see the ʻāina as family, we’re gonna fight to protect it like we would fight to protect our own kūpuna (grandparents),” she says. “What is driving us is this sense that this is our homeland and we have become strangers in our own homeland. And we don’t like it.”

Partnering for a sustainable path forward for Hawaiʻi

Small signs of progress have been evident as a result of Native Hawaiian activism, and efforts to bridge the gap between Native Hawaiians and the tourism industry are being made.

On June 2, the Hawaii Tourism Authority – the group responsible for managing Hawaiʻi’s tourism industry – announced that they selected the Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement for a contract to take over brand management and support services in the US market.

The council is another Native Hawaiian non-profit group that aims to enhance the cultural, economic, political and community development of Native Hawaiians.

According to Oralani Koa, Manager of Hawaiian Programming at The Westin Maui, there are more Native Hawaiian cultural advisers in tourism and hospitality than there ever were 10 years ago.

“We are able to be the voice between our community and the resort,” she says. “That means we’re making progress, and progress is a good thing. It might not be as fast as we want it to be, but at least we’re seeing some kind of movement. Yes, there’s still lots of work to be done, but every little bit counts.”

As a cultural adviser, Koa helps facilitate authentic Native Hawaiian cultural experiences for guests through activities such as weaving, education on plants and their uses and learning oral history through moʻolelo (storytelling) and mele (songs). She also ensures that the resort accurately represents Hawaiian culture.

“It’s such an exciting time because what that means for us is that in this hospitality industry they see the value of culture,” Koa says.

According to Koa, resorts can’t put a number on cultural adviser positions and don’t fully know if the positions will bring in more money or a return on their investment. However, the fact that more resorts are opting for this position shows that cultural advisers are becoming more of a necessity.

“I love that because it opens more seats for our people to be at this place that we always should have been at,” she says.

Explore related stories

Local Voices

Nov 23, 2022 • 7 min read

Since Oʻahu and Maui both dazzle, it’s no easy task to decide which Hawaiian island to visit. We’ve asked two writers to make the case for each.

Feb 21, 2024 • 2 min read

Dec 9, 2023 • 10 min read

Nov 28, 2023 • 5 min read

Nov 17, 2023 • 10 min read

Nov 11, 2023 • 9 min read

Mar 7, 2023 • 6 min read

Jan 20, 2023 • 4 min read

Nov 15, 2022 • 6 min read

Jun 20, 2022 • 5 min read

- Out Traveler Newsletter

Search form

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use .

Tourism Takes A Toll on Native Hawaiians, But Here’s How You Can Help

Enlightened entrepreneurs and activists seek to make tourists more aware and responsible.

(CNN) -- The Hawaii most tourists see is one of azure waters and towering resorts, of “aloha” and “ohana,” and “hula.”

But as it exists now, the powerful tourism industry dictates the lives of Native Hawaiians, often for the worse, said Kyle Kajihiro, a lecturer at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa and activist for the rights of Native Hawaiians.

The tourism industry in Hawaii powers its state revenue, but that reliance on tourism has resulted in Native Hawaiians getting priced out of their homes, climate change wreaking havoc on the natural landscape, and a lack of respect for the 50th state that is also the ancestral land of more than half a million people.

“I think that it is too easy for people to visit places like Hawaii,” Kajihiro said. “It conditions visitors to feel entitled.”

The industry must change to improve the futures of Native Hawaiians, Kajihiro told CNN . He’s one of several residents who have worked to educate visitors and return some elements of Hawaiian culture to the people from whom it originated. If visitors to Hawaii decenter themselves and instead take with them respect and a willingness to learn -- or choose not to visit at all -- then Hawaii may be preserved for the people who have called it home for centuries, activists say.

For many residents, living in Hawaii is no vacation

Tourism is Hawaii’s largest single source of private capital, per the Hawaii Tourism Authority . Even amid the Covid-19 pandemic, it remains incredibly lucrative: In April alone, visitors to Hawaii spent over $1 billion in the islands, according to a state report marking the recovery of tourism since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic.

But what’s profitable for Hawaii’s economy can negatively impact the lives of Native Hawaiians and yearlong residents. To combat drought conditions, residents last year were asked to reduce their water consumption or face a fine while large resorts continued to use far more water. There are millions more annual visitors than there are permanent residents – in 2021, there were more than 6.7 million visitors compared to 1.4 million residents – which can cause carbon emissions to surge and overuse of its beaches, hiking trails, and other natural wonders. Hawaii has even been called the “ extinction capital of the world ” for the number of species who’ve gone extinct or are at high risk of dying out.

It also has the highest cost of living in the nation, partly due to the state having to import around 90 percent of its goods. Its housing market is one of the most expensive in the country, ProPublica and the Honolulu Star-Advertiser reported in 2020, and with a large demand for land and a limited amount of it, Native Hawaiians can spend decades waiting to reclaim ancestral land, leading some to move from the islands.

“Tourism normalizes and conceals the current dystopian reality experienced by many Kānaka Maoli and the poor immigrant communities in Hawaii,” Kajihiro told CNN . (Kānaka Maoli is the Hawaiian-language term for Native Hawaiians.)

To empower Native Hawaiians and return some of their rights, the tourism industry needs to change, beginning with its ethos, Kajihiro said.

‘DeTours’ show the real history of Hawaii beyond the beach

In an effort to reclaim the histories of Hawaii and educate residents and visitors about the impacts of colonization, militarization, and tourism, Kajihiro created the Hawai’i DeTour Project. The program, which he runs with lifelong activist Terrilee Kekoʻolani, aims to “interject a more critical historical account of Hawaii” in hopes that it’ll start conversations about social responsibility and create solidarity with social justice and environmental activist efforts in Hawaii.

Kajihiro leads DeTours to locations like downtown Honolulu to discuss Hawaii’s former sovereignty; to Iolani Palace, where the US supported a White settler-led coup against Queen Lili’uokalani; to military landmarks like the Pearl Harbor memorial to discuss American efforts to transform parts of Hawaii into military strongholds.

Though Kajihiro doesn’t advertise his services, visitors are increasingly seeking them out. While he prioritizes educational and political groups that can help create change locally, he has seen both residents and visitors on his tours, some of whom go on to become involved in the causes he highlights.

“I guess it could be seen as a good sign that people want to learn and be more responsible as travelers,” he said. “But there are also many people who simply want the novelty of a ‘reality’ tour or seek to assuage their guilt by doing a more ‘socially responsible’ tourism. I'm not interested in giving people permission to visit Hawaii guilt-free.”

One way to support Native Hawaiians is to not visit at all, some say

Two educators in Hawaii borrowed the name of Kajihiro’s operation for their book, which also shares his principles. Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai’i , co-edited by Vernadette Gonzalez and Hōkūlani Aikau, is no ordinary guidebook – it’s a call to action.

The book is designed to educate readers about Hawaii’s past and present and the negative impacts of colonization, militarization, and tourism. Even if readers never make it to Hawaii, the stories transport them to some of the sites Kajihiro leads his groups to. In the introduction to the book, Gonzalez and Aikau write that not all readers will be “invited or allowed to go to all of the places that are described,” and some locales were left out entirely because they’re “not meant for outsiders.”

Many tourists’ relationship to Hawaii is an extractive one, Gonzalez and Aikau write, and that relationship must shift to one of support if the Hawaii tourists know and the Hawaii its residents live in are to continue to exist. Even better, they write, would be choosing not to vacation in Hawaii at all.

“Sometimes the best way to support decolonization and Kanaka ‘Ōiwi (Native Hawaiian) resurgence is to not come as a tourist to our home,” the editors write.

Improving tourism begins with respect for the islands and Native Hawaiians

Of course, there will always be tourists in Hawaii as long as it remains the islands’ top industry, and as long as its beaches beckon to guests with deep pockets. The nonprofit Sustainable Tourism Association of Hawaii connects tourists with local attractions that emphasize cultural and environmental responsibility. The Coconut Traveler, a travel company created by Debbie Misajon, the granddaughter of Filipino immigrants who moved to Hawaii to work on sugarcane plantations, is aimed at wealthy guests and charges a responsible tourism fee, 100 percent of which goes to local organizations that work to sustain Hawaii’s natural beauty. Recentering the focus of a trip to Hawaii from the guest to the island and its residents might lighten the footprint a tourist leaves there, Misajon told CNN.

“I'm all for coming and enjoying the islands, but (I) encourage people to find ways to be part of the solution,” Misajon said. “It might be trite, but spend your money locally.”

Making fundamental changes to the tourism industry should begin with returning rights to Native Hawaiians and letting them decide how they want their culture to be shared and consumed, if at all, Kajihiro said. There’s already a model of this in New Zealand, where the Māori people have control over how their culture is represented and experienced by tourists, he said, with an emphasis on mutual respect.

“Let’s abolish the word ‘tourism,’” Kajihiro said. “The very term privileges the consumer, the act of consuming places, and the transactional relationship.”

Instead, he said, visitors should “rethink travel as entering someone else’s home.” Someone who’s a guest at someone else’s home may bring a gift with them or express their gratitude to their host in other ways, he said.

“As a visitor, you have the burden to learn, act responsibly, not be a burden and respect your hosts,” Kajihiro said.

The-CNN-Wire ™ & © 2022 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.

Want more breaking equality news & trending entertainment stories?

Check out our NEW 24/7 streaming service: the Advocate Channel!

Download the Advocate Channel App for your mobile phone and your favorite streaming device!

APPLE STORE - GOOGLE PLAY

ROKU - APPLE TV - FIRE TV - GOOGLE TV

From our Sponsors

Most popular.

Ron Amato Retrospective: 75 Gorgeous Images of Queer Men

Updated: here are the final 27 surviving lesbian bars in the u.s., turkish oil wrestling: male bonding at the kirkpinar festival, just in time for pride – the 15 gayest cities in the world in 2023, the 13 least visited national parks, onlyfans star reno gold on his new boyfriend and travel show, here are the best gay sex and male nudity scenes in 2022, get soaked with these 35+ steamy pool pics from this year’s white party, 12 years of intimate photos of same man - taken by his partner, slovakian jocks with nothing to hide, latest stories, ötzi, the world's sexiest world traveler mummy, reveals a thirsty secret.

Discover endless fun at The Pride Store: Games & electronics for all ages

Unlocking a new level of beauty with dr botanicals' ethical skincare line, unleash your wild side with the pride store’s beginner’s guide to kink, today's eclipse forecast: prime viewing weather ahead, celebrate 40 days of pride on west hollywood’s 40th anniversary, rare pre-stonewall ‘gay cookbook’ on sale in nyc this weekend, ugandan lgbtq+ activist stabbed, left for dead, escapes to canada, adult entertainment icons derek kage & cody silver lead fight for free speech, 'drag race's morphine declares miami a certified drag capital, spring into the pride store’s top new arrivals for april, the incredible ‘sacred’ waterfall you probably never knew existed, exclusive: lady bunny cuts ties, sues bianca del rio, equalpride's ceo on standing together this transgender day of visibility, 30 steamy pics of out celebrity stylist johnny wujek, go green with envy with 70 pics from sidetrack chicago's st. patrick's day party, here's everything you missed at beyond wonderland socal from a gay man's perspective, 35 burly & beautiful pics from bear troop 69's inaugural bear jamboree at gay disney , breaking boundaries in gender-free fashion with stuzo clothing, pete buttigieg commits federal resources to baltimore bridge collapse recovery, trending stories.

Why are mpox cases in the U.S. on the rise again?

Best tips to see today’s eclipse, according to this famed gay astrophotographer

Why most GOP women are standing by their man

How climate disasters hurt mental health in young people

Jan calls out disgraced 'Drag Race' queen Sherry Pie's attempts at making a comeback

Uganda used the U.S. Supreme Court's anti-abortion ruling to outlaw being LGBTQ+

Tia Kofi & Hannah Conda dish on 'DRUKvTW' secrets, rivalries & have us CACKLING

15 pre-Stonewall LGBTQ+ films you should definitely to watch

'Drag Race' star Q shares she's living with HIV

Gay gym culture has a deadly downside

Here's how to BEST see today’s eclipse, according to a gay astrophotographer

'Mary & George's Nicholas Galitzine loves his connection with LGBTQ+ fans

8 dating tips for gay men from a gay therapist

The trailer for this year’s coolest, queerest show is here and we’re already under its spell

Scarlet fever: exploring our fascination with blood

These are the most challenged library books in America — yes, most are LGBTQ+

France becomes world’s first country to enshrine abortion rights in constitution

University of South Carolina coach Dawn Staley says she supports transgender athletes in women's sports

A timeline of every winner of 'RuPaul's Drag Race' around the world

Orville Peck opens up about why he changed up his mask for the new 'Stampede' era

These 9 states have the chance to protect abortion this election — Here's what you can do

Nashville PD Must Pay HIV-Positive Man Denied a Job

All 6 rogue Mississippi cops got long prison sentences in 'Goon Squad' torture of 2 Black men

Joe Biden has tied the record for most LGBTQ+ judges confirmed in federal courts

19 LGBTQ+ movies & TV shows coming in April 2024 & where to watch them

Most recent.

The star is back! The new trailer for 'MaXXXine' just dropped & we have to stan

Is Tom Ripley evil? Andrew Scott doesn't think so

Amy Schneider's come-from-behind win puts her ahead in 'Jeopardy!' tournament

Small-college association bans all transgender women from women's sports

Happy national foreskin day!

Election season got you down? This crisis line is soothing LGBTQ+ mental health

Opinion: I'm a climate scientist. If you knew what I know, you'd be terrified too

Omar Apollo says he was kissing girls last weekend & we wish that was us

Bud Light boycott likely cost Anheuser-Busch InBev over $1 billion in lost sales

5 times celebrities clapped back at biphobia & read the haters to FILTH

The Advocate's Jake Shears cover: Go behind the scenes

Pope Francis can’t seem to decide whether the church should welcome or condemn trans people

10 Black queer country artists you should add to your playlist immediately

Federal judge grants Casa Ruby founder Ruby Corado pre-trial release from D.C. jail

Billie Eilish UNLEASHES on Rolling Stone over alleged leaked track list

Did JoJo Siwa steal her new song from another artist? Here's why fans think she did

16 Republican AGs threaten Maine over protections for trans care and abortion

LGBTQ+ patients twice as likely to face discrimination: survey

Recommended stories for you, scottie andrew.

What Native Hawaiians Want You to Know Before a Trip to Hawaii

By Taylor Weik

When Camille Leihulu Slagle applied for on-campus housing at Stanford University mid-pandemic, she was initially excited to leave her home of Oahu, Hawaii. Slagle, who is Native Hawaiian, was working two jobs while attending school remotely and was worried about not having time to focus on her studies, as well as potentially infecting her multigenerational household with COVID-19.

Though her grades have improved since living on the mainland, Slagle is now dealing with a different issue: seeing her classmates’ social media posts about traveling to Hawaii for vacation.

“It’s funny because throughout high school I’ve told people, ‘I’m leaving’ and ‘I want to get off this rock,’” the 19-year-old college freshman said. Now, Slagle says, “I’d give anything to go back. It’s frustrating to see people go into my home and do whatever they want in the middle of a pandemic. Part of the reason I moved up here was to not bring COVID home to my grandma.”

The recent surge of visitors to Hawaii is a concern among locals who are worried about an increase in COVID cases and the health and safety of their family members. Hawaii’s state travel data revealed that nearly 190,000 people visited the state between April 10 and April 17 alone, and with the summer months approaching, this number is expected to reach pre-pandemic tourism levels . Though Hawaii has a mask mandate requiring all people in the state to wear face coverings in public, local news has reported a number of tourists flouting the rules .

For young Native Hawaiians like Slagle, the pandemic has highlighted their community’s long-standing issues with settler colonialism and the state’s massive tourism industry, which threaten their livelihoods and futures on the land their families have inhabited for generations.

“The tourism industry makes money by exploiting Hawaiian culture,” Slagle said. “Hawaii has been portrayed as a paradise and an escape from reality for so long that of course people want to come here to forget their troubles. They’ll leave Hawaii with happy memories, but they won’t think about the harm they might have caused to the people who actually live here.”

Last year, the University of Hawaii reported that Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander communities have been hit the hardest by COVID, and the Hawaii Department of Health released new data showing that residents who identify as white or Asian are far more likely to have been vaccinated at this point in the pandemic than other groups, including Native Hawaiians. Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders make up a large percentage of essential workers on the islands and are more likely than other ethnic groups to have poorer economic and living conditions.

Slagle attended an all-Native Hawaiian school for 13 years and grew up with a deep understanding of her culture and history. Attending a more diverse educational institution in California has been an eye-opening experience, she said, and made her realize just how many non-Native people don’t know about Hawaii beyond its status as a vacation destination.

“I’ve been making TikToks explaining our history and responding to people who say they want to move to Hawaii in the pandemic,” Slagle said. “Some say we are ‘gatekeeping’ Hawaii, which makes no sense. We’re simply trying to reclaim what was ours in the first place.”

TikTok content

This content can also be viewed on the site it originates from.

Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua, a professor and chair of the department of political science at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, says much of the displacement and dispossession Native Hawaiians feel today can be traced to U.S. occupation and the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the 1890s .

“There was an illegal seizure of all of our national lands, followed by settlement over the next century that has displaced Hawaiians,” Goodyear-Kaʻōpua said. Today, Native Hawaiians comprise just around 10% of the state’s population. “And after statehood in 1959, there’s been nonstop housing development and hotels.”

In addition to worrying about their community’s health, some young Native Hawaiians have also expressed fear that they may one day be unable to buy their own homes. As of February , the median price of a single-family home on Oahu reached $920,000, up 20% from the same month last year, according to real estate firm Locations.

Connor Kalikoonāmaukūpuna Kalāhiki’s family moved to Nevada after he graduated high school because the cost of living was more affordable, and shortly after the pandemic broke out he joined them. Though the 20-year-old Native Hawaiian hopes to move back to Hawaii after graduating from college, he’s now unsure whether that’s a feasible possibility.

“At this rate, I might never be able to own my own house on my ancestral homeland,” he said. “Thinking long-term and sustainably, I’ve been asking myself, ‘How am I going to ensure I can move back home and have security?’ And I’m not sure, and that’s extremely troubling to think about.”

Goodyear-Kaʻōpua says understanding the frustration Native Hawaiians feel about not being able to afford homes in Hawaii requires an understanding of the deep ties they have to the islands.

“Native Hawaiians are genealogically connected to this place and understand ourselves as a network of family relationships that include the mountains, winds, and other manifestations of life,” she said. “We are one sibling among many in this family. To be separated from the land is to be assaulted at the very foundation and fiber of who we are as a people. That process of dispossession has been going on for well over a century now, and has always been a project of imperialism, settler colonialism and oftentimes for corporate, capitalist gain.”

Kalāhiki said one main reason for Hawaii’s affordable housing crisis is that there’s not enough homes to meet the demand . The housing market in Hawaii is competitive and filled not only with locals who wish to buy homes, but also out-of-state buyers who plan on using the homes for vacations or Airbnb short-term rentals .

“I don’t know if these owners realize it, but they’re contributing to this transient community of tourists coming in and out of Hawaii whenever they please,” he said.

By Angie Jaime

By Liv McConnell

Locals expressed outrage online after the recent news that Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan, purchased 600 acres of land on Kauai . The couple now reportedly own more than 1,300 acres of land in Hawaii. (The couple told Insider that they've “been working closely with a number of community partners to promote conservation” on their property and the surrounding area).

Though he’s not currently living in Hawaii, Kalāhiki hopes to continue supporting his community by transforming Helu Kanaka , the civic engagement organization he created in high school with two peers, into a Native Hawaiian youth rights activist group.

“The argument is always that we need tourism, but my counterargument is that we should shift away from tourism and invest in the community,” Kalāhiki said. “I hope our generation can be a strong force for Indigenous self-determination and liberation, but that’s not possible without a lot of work and investment in what we believe to be important.”

As for the tourists who have already purchased their plane tickets, Kalāhiki recommends being mindful of leaving Hawaii better than they found it.

“When you’re coming as a visitor, you don’t necessarily have to live up to that tourist role,” he said. “While you may be taking up space, you can help to offset that negative impact by volunteering at the local church or a food bank or donating to local nonprofits.”

“I’m not saying people can never come to Hawaii,” Slagle said. “I want people to experience the same love I have for this place, but there is a time and place to do so. I want people to do their research to learn why we’re so hesitant about people visiting.”

Want more from Teen Vogue ? Check this out: How White People Pushed Out Hawai'i's Monarchy

Stay up-to-date with the politics team. Sign up for the Teen Vogue Take!

By Alice Wong

By Maya Rupert

By Lydia McFarlane

By Lex McMenamin

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

How to Travel to Hawai‘i More Mindfully, According to 7 Native Hawaiians

By Annie Daly

If you’ve been following the news about Hawai‘i , you probably know that the state is in the midst of a great, pandemic-induced travel debate. In a nutshell, the travel restrictions imposed by COVID meant fewer visitors to the islands, which gave many Native Hawaiians and locals a glimpse of what life could be like if they had their home to themselves again: Hiking trails with room to roam. Roads without congestion. Beaches with less pollution.

Firework content

This content can also be viewed on the site it originates from.

And while overtourism was already a growing problem in the Aloha State before the pandemic, this glimpse of an untrampled Hawai‘i was so enticing that it pushed the issue into the spotlight more than ever before. Some Native Hawaiians and locals began to call for tourists to stop visiting entirely, but many others—including the state’s Hawai‘i Tourism Authority (HTA) and Hawai‘i Visitors & Convention Bureau (HVCB)—took a more nuanced approach. The answer, they felt, was to encourage travelers to visit in a more mindful way. In 2020, HVCB launched a tourism program called Mālama Hawai‘i, which is ultimately a way to give back on your trip (“mālama” means “to take care of” in Hawaiian). The idea is to encourage travelers to leave Hawai‘i better than it was when they found it, so they are helping to curb—not contribute to—the overtourism problem.

So what does this mean for your next trip to the islands? The Native Hawaiian and tourism executive Kainoa Daines, who was heavily involved in the Mālama Hawai‘i program—and with whom I co-wrote the book Island Wisdom: Hawaiian Traditions and Practices for a Meaningful Life —says that the solution is to be more mindful when you visit. Hawaiian culture has been overcommercialized and appropriated for many decades, and one way to show respect for its beauty is to treat both the land and the people with extra care.

To help you do just that, I asked seven of the Native Hawaiians featured in Island Wisdom —including Daines himself—for their advice on how to mālama Hawai‘i while you’re there. Follow these tips for a more conscious trip.

Remember that when you visit, you’re visiting someone’s home

When you travel anywhere in the world, including Hawai‘i, you’re a guest in someone else’s home, and it’s necessary to consider their values, traditions, and culture just as importantly as you would your own. Sadly, too many people travel with a sense of entitlement rather than one of humility, respect, and love. Here are a couple of ways to respect our culture while you’re here:

- Attend a festival or event. Doing so will introduce you to local culture, food, music, and the people you’re visiting. To find an event, bookmark this page when planning your trip.

- Park in marked stalls and follow all traffic signage. It’s shocking how many visitors don’t do this! Making your own parking space in someone’s yard or driveway so you can get to the beach easier is insensitive, illegal, and greatly inconveniences the resident.

- Heed all warning signs when you’re out exploring, from “kapu” (no trespassing) signs to strong current signs at the beach. Hawai‘i’s weather patterns can create dangerous conditions, and the signs are there for a reason: to keep you, the land, and the first responders safe. Cautionary signs also keep unwanted visitors from entering our sacred spaces that are meant only for those who truly understand their importance.

—Kainoa Daines, co-author of Island Wisdom and senior director of brand for the Hawai‘i Visitors & Convention Bureau

Embrace the traditional Hawaiian concept of pono

As Hawaiians, we’re taught many traditional values when we’re young, and we live by them for our whole lives. One that can be especially useful when you visit is pono. While this concept has many definitions, the one that aligns the most with tourism means righteousness, or doing the right thing to stay on track. But here’s the key: It’s not about doing the right thing for yourself based on your own standards or definitions; it’s about doing what is right for the other person and the situation at hand. And when you visit, that means doing the right thing for Hawai‘i at large.

In other words, embracing the concept of pono while you’re here means striving for the best possible outcome for Hawai‘i. This means taking the locals’ views and experiences into account rather than just your own. If there’s a “no trespassing” sign in front of a beautiful cliff, for example, resist the urge to go take a photo and think about it from the Hawaiian perspective: That sign is there for a reason. Do the right thing so you leave no harm. The additional beauty of this is that when you come to any situation with pono, you will likely be embracing other Hawaiian values, too, like aloha (connection and love) and ha‘aha‘a (humility) and hōʻihi (respect). And because Hawaiians believe that everything is reciprocal, especially the aloha spirit, acting this way means you will feel even more of that loving aloha yourself, too.

—Keoua Nelsen, O‘ahu-based master lauhala weaver and Hawaiian language advocate

Learn the deeper meaning behind your lei—and treat it with care

Lei are defined as garlands or wreaths typically made from elements of nature, such as flowers (plumeria, orchids, carnations, tuberose, and pikake [jasmine]), leaves, shells, nuts, seeds, feathers, and more. But the most important thing to know about them is that they are created with intention. As a lei maker myself, I love to pick some fresh flowers in the morning before the hot sun comes up, and then put some Hawaiian music on and think good thoughts about the person I’m making it for. I truly believe that you put your intention and your spirit into whatever you’re creating. Many of the flowers used in lei are even grown for their cultural association: Jasmine can be meant to honor Princess Ka‘iulani, crown flower honors Queen Lili‘uokalani, red roses honor Princess Pauahi… the list goes on.

That’s why, as a traveler, it’s so important to receive a lei with honor and take care of it after you do: because someone made it for you with love and intention. When the fresh flowers begin to fade, do as the locals do and set the lei gently on your nightstand to enjoy the remaining fragrance, rather than carelessly tossing it in the trash. We’ll often drape a lei on a framed photo of a loved one, or place multiple lei on the graves of our family and dear friends after an event. Sometimes we even return them to the forested areas from whence they came, or place them in the garden to return them to nature. At the end of your trip, you can find a nice garden to place your lei. No matter what you do, remember: Lei are always cherished, always intentional, and never discarded.

— Desiree Moana Cruz, Hilo-based lei maker and cultural advocate

Honor the sanctity of traditional Hawaiian foods

Before the cargo ships, air carriers, supermarkets, big box stores, and Amazon, ancient Hawaiians existed perfectly with both the natural resources that were available, and an intricate understanding of how to care for them. And that’s why, as a visitor, it’s especially important to know and understand the traditional, pre-contact foods like hāloanakalaukapalili (taro). Because these traditional foods sustained our ancestors for generations, they are considered sacred.

One of our ʻōlelo noʻeau, or traditional wise sayings, is “Huli ka lima i luna, make, huli ka lima i lalo, ola,” which translates to “Hands turned upwards, bring death; hands turned downwards, bring life.” Ultimately, this saying means that those who only hope to receive shall perish, while those who come with their hands to the soil shall live. If you would like to “taste” the traditional cuisine and culture of Hawai‘i, I recommend you come with your hands turned to the soil. There are some amazing Hawaiian organizations that are revitalizing these traditional values of food, cultivation, stewardship of the land that feeds us, and the traditional Hawaiian cultural beliefs that fuel it. Some of my favorites that you could connect with, volunteer for a service work day, or make a donation with include: Papahana Kuaola , Kākoʻo ‘Ōiwi , Paepae O Heʻeia , Hoʻokuaʻāina , Kōkua Kalihi Valley , and Ke Kula O SM Kamakau .

—Kealoha Domingo, Native Hawaiian chef, cultural practitioner, and owner of the Hawaiian catering company Nui Kealoha

To fully embrace Hawai‘i, let Hawai‘i embrace you

In Hawaiian culture, we believe that all of the elements around us—like the rain and the wind and the clouds—are speaking to us through hula. And that’s why I always tell our visitors: When you drive around Kaua‘i and you get to the canyon [Waimea Canyon], stop. Listen. Let Kaua‘i welcome you. Let Kaua‘i speak to you. We are so quick to pick up our technology and capture a picture, but why not capture it in your spirit first? Stop, take it in, and make that connection. It’s a feeling… you have to allow the island to speak to you, because it will. To fully embrace this place, you have to allow this place to embrace you.

Another way to make that connection is to stop and watch people dancing hula. (For example, I do a free hula show each week at the National Tropical Botanical Gardens in Kaua‘i.) In Hawaiian culture, hula is an extension of the land—so when you see people dancing hula, you’re connecting with our ʻāina (land). With our culture. Remember, the dancer you’re watching is an extension of this land, of our ancestors. That’s our kūpuna (ancestors) speaking. As a visitor, it’s important to understand the thoughts and intentions of the natives of that place, and embracing the wisdom of hula will help you do that.

—Leinā’ala Pavao Jardin, Kaua‘i-based Kumu Hula

Know that your energy has an impact on everyone and everything around you—so be sure to visit with an open mind

I lead interactive storytelling experiences called Mysteries of Hawai‘i , where I take a group of visitors around to some of the most sacred places in Honolulu, and I always tell everyone in my group: Your experience here in the group is a microcosm of how you should behave when you visit Hawai‘i overall. Everyone is involved in the process in one way or another, from learning each others’ names to finding out what each person does for a living. That’s what you should do when you visit, too: Get involved. Ask questions. Be open. And remember that you are now part of a community, part of something bigger.

I always tell people in my groups that their own energies, feelings, thoughts, and spiritual beliefs will determine how the course of the experience (tour) will go for the evening, and they are often enlightened. This is a very Hawaiian concept, the idea that your energy has an impact on the greater collective. And when you remember that when you visit—when you remember that your actions and energies impact those around you, including the locals—everyone will be better for it.

—Lopaka Kapanui, Honolulu-based Master Storyteller and Kumu Hula

Treat the water with respect

The Hawaiians Islands are totally dependent on rainfall for all fresh water. In Hawaiian culture, the importance of fresh water can even be found in our language. The Hawaiian word for fresh water is wai, and something valuable—a treasure—is waiwai. Water is truly a treasure. And yet we face challenges to provide sufficient water resources due to extended drought periods, climate change, and, most recently, contamination issues.

That means that, when you’re here as a traveler, it’s important to treat all of our water—including the ocean, freshwater streams and rivers, and watersheds—with care. Our saying for this is “e mālama i ka wai,” which translates to “cherish water.” The simple guiding message is to use what you need, but please don’t waste it. We Hawaiians need to take care of the land, the ocean, and waters, which means that travelers need to take care when visiting, too. What we all do today will affect our children and the generations that follow.

— Arthur Aiu, O‘ahu-based water specialist and high chief of the Royal Order of Kamehameha

More Great Living Stories From Vogue

The Best Places in the World for Solo Travel

Candice Bergen on What It Was Really Like to Attend Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball

The Curious Case of Kate Middleton’s “Disappearance”

Sofia Richie Grainge Is Pregnant! And It’s a….

Never miss a Vogue moment and get unlimited digital access for just $2 $1 per month.

Vogue Daily

By signing up you agree to our User Agreement (including the class action waiver and arbitration provisions ), our Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement and to receive marketing and account-related emails from Architectural Digest.. You can unsubscribe at any time. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

The fight to take back Hawaii: How native Hawaiians are reclaiming their culture, language and land

For over a century, the destiny of this island paradise has been in the hands of outsiders. Now native Hawaiians are reclaiming their culture, language and land.

It's known as the Seven Mile Miracle. The famed North Shore of Oahu, Hawaii, is home to some of the world's most iconic surf breaks.

Every year, the North Shore plays centre stage for an epic battle between the world's best surfers for the sport's most coveted crown, the Pipeline Pro.

But just beyond these fabled sands, another battle is being waged. It's a fight to keep Hawaii Hawaiian.

Under swaying palm trees in the quiet streets behind Sunset Beach — Paumalū to the locals — Pomai Hoapili is holding on to a slice of paradise that has been in his family for generations.

Pomai grew up here in a small home, set between the roaring ocean and the green Hawaiian hills, with Pipeline and Sunset on his doorstep.

"I live in the middle of these two super famous waves that people make pilgrimages out to, to come and catch a few waves," he says.

"They pay millions of dollars to come here where I live. I'm blessed to grow up here."

But Pomai is an increasing rarity on Hawaii's North Shore — a native Hawaiian.

As property prices soar, many native Hawaiians — or Kānaka Maoli — are being squeezed out, unable to keep pace with crippling property taxes and skyrocketing rents.

The pandemic has only made the problem worse, pushing prices to record highs as mainlanders from the US look to Hawaii for an island bolthole.

Just down the road, the so-called "Quiksilver house" on the beachfront at Pipeline sold last year for $US5 million, more than double the price it last changed hands for, in 2009.

For Pomai, who works as a lifeguard for the famous Hawaiian Water Patrol, staying on the North Shore is about more than holding on to the family home.

It's about maintaining a connection to Hawaiian culture, which has revolved around surfing and the ocean since Hawaiians took to the waves on wooden boards hundreds of years ago.

"I want to be a Hawaiian on Hawaiian land," he says.

"We're lucky to be able to pull it off, you know. But it's definitely not easy. Living in Hawaii, staying in Hawaii, you gotta hustle. It's not an easy thing."

Like many Hawaiians, Pomai feels a sense of pride that these islands gave surfing to the world and continues to produce world champions like Carissa Moore.

But the growth of surfing into a multi-billion-dollar global industry has also helped transform the sleepy North Shore into one of the most desirable postcodes on the planet.

"It's pretty well overrun," he says. "Surfing's taken up a huge chunk of housing and resources on the North Shore, as well as waves."

Many of the original homes have been flattened to make way for modern mansions.

Locals who sell up often end up buying on the US mainland, where properties are more affordable and they can live in relative comfort.

Los Angeles County is now home to more native Hawaiians than the island of Maui.

Pomai has seen others sell up, but once they leave, he says, "it's hard to come back".

"Somebody's going to take your spot, guaranteed. People are fighting outside the door," he says. "But this is home, so we're going to stay, hold it down. There's no other option."

'Premeditated theft'

For the Kānaka Maoli, the struggle to retain control of their land is a constant. It dates back over a century to when the Kingdom of Hawaii was illegally overthrown.

"We are our own country," says Pomai. "There is no annexation treaty [with the US]. We are actually our own sovereign nation illegally occupied by the United States of America."

On January 17, 1893, a group of American fruit and sugar plantation oligarchs launched a coup against Queen Liliuokalani, putting her under house arrest inside Iolani palace.

At first, the United States of America didn't endorse the coup, but in 1898 it annexed the Kingdom of Hawaii and administered it as a US territory until 1959, when Hawaii became the 50th US state.

"This is a theft — premeditated, systematised theft," says Kalehua Krug, a Hawaiian charter school principal and community leader.

"They took it from our chiefs. They took it from the royalty. They took it from all of our families."

Kalehua is among a generation of Hawaiians committed to the rebirth of native Hawaiian culture.

His school teaches the Hawaiian native language – which nearly went extinct after generations were discouraged from speaking it – as well as traditional hula dancing, alongside the mainstream school curriculum.

"When you give the culture and ceremony and language to them at a young age, they don't have to feel the loss like we did," Kalehua says of his students.

"You know, they don't have to take that punch in the gut that we had to take."

Land seizure has been central to the US's effort to control Hawaii, he says, "because land, you know, builds generational wealth, and they could control the resources".

"They could lock up the water, they could lock up the food, they could lock up the ability of Hawaii to self-sustain."

The land is no longer sustaining native Hawaiians, Kalehua says. People have been forced to turn to new ways to get by.

Soon after the US made Hawaii a state, a new kind of visitor followed – tourists.

A Time magazine article published in 1966 called it a "jet rush", as the number of visitors arriving to the islands had doubled in recent years.

That jet rush never ended.

The Waikiki mirage

On Oahu's South Shore, Waikiki is a bucket list destination for millions of tourists lured by its white sands and postcard-perfect sunsets.

But for many native Hawaiians living and working in the capital, Honolulu, the tourism idyll is little more than a mirage.

Peeling back Waikiki's layers is Honolulu local Chris Kahunahana, a filmmaker who has lived here for much of his life.

Chris is one of an emerging group of indigenous artists challenging the postcard cliches about Hawaii on the big screen.

"Initially in the film industry, Hawaii was seen as Hollywood's backdrop," he says.

"It served as a beautiful location for a Caucasian hero. But the stories weren't from here, they were just using here as an exotic location, one that's prettier than Detroit, right?

"The world is starting to understand the value of authentic stories. They're tired of the same old shit."

Chris sees it as an artist's job to "hold up a mirror to society and say, 'Hey, look at this ugly picture'". His acclaimed feature film, Waikiki – the first directed by a native Hawaiian – does just that.

Through its main character Kea – a woman living out of her car while balancing multiple jobs in the tourism industry – the film explores how hard it is for indigenous Hawaiians to get by in contemporary Hawaii.

Many of the issues the film raises stem from the separation of Hawaiians from their land, Chris says, which has cut off many from economic opportunities.

"Hawaii is being sold to the global elite," he says. "Anyone around the world who has any kind of resources wants a piece of paradise.

"And it's because of this tourism industry – they've been selling this lie of Hawaii as a paradise."

The demand for a piece of Hawaii is pushing some out. "Without Hawaiians, is it really Hawaii? It's not," says Chris. "The powers that be, they don’t give a shit."

In 2019, more than 10 million visitors flocked to Hawaii, with most rubbing their toes on the sands of Waikiki.

Tourism is Hawaii's biggest economic driver and accounts for 21 per cent of jobs in the state, but hospitality staff are among the islands' worst paid workers.

Like the protagonist in Chris's film, some live a precarious existence on on the edge of poverty, unable to secure stable housing.

Hawaii, he says, regularly tops the list of the US's most expensive places to live, ahead of New York and California.

"At least in San Francisco, you have the tech industry; in New York, you have media – it's f***ing New York!" he says.

"Unfortunately, the only jobs that they provide for people in Hawaii are tourism jobs.

"They are like servant jobs – you are providing them a service, entertainment, an experience – a cultural experience, right?

"They are not really interested in the real culture. They are interested in experiencing it as entertainment. It's not back and forth, it's not give and take – it's just take, take, take, take."

The result has been an epidemic of homelessness, a problem that disproportionately affects native Hawaiians.

Hawaii now has the third-highest homeless rate in the USA.

Half of the state's homeless are native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, despite only making up 20 per cent of the population.

According to Chris, they're not really homeless, but "houseless".

"The fact they can't afford to purchase a house – [Hawaii] is still their home," he says. "This is their home. They just don't have a house."

The west side divide

On Oahu's west side, Makaha Beach is famed as the birthplace of big wave surfing, where waterfront apartments take in views of waves peeling around the point.

But Oahu's fiercely beautiful west side is also where Hawaii's homelessness crisis is most apparent.

All along the ribbon of the Farrington Highway, which skirts the coast on Oahu's western shore, native Hawaiian flags flap upside down in the breeze, on porches and in shop windows.

It's a sign of distress.

Also dotting the foreshore are makeshift homeless camps, where individuals and families live in makeshift shelters, trapped between two worlds.

Many have jobs, their children go to local schools, and life continues – they are indeed "houseless".

With limited support from the state, one community is tackling the issue themselves and establishing a more permanent solution.

Houseless Hawaiians are living on the beaches of Oahu's west side.

Foreign Correspondent: Matt Davis

Not far from the rolling waves of Makaha, behind rows of gleaming yachts in the Wai'anae Boat Harbour, is Pu'uhonua O Wai'anae, a permanent homeless camp.

Pu'uhonua means "place of refuge". That's what the camp's founder and matriarch, Twinkle Borge, intends for people to find here when they fall on hard times.

Pu'uhonua O Wai'anae has existed beside the boat harbour for almost 20 years since Twinkle, herself homeless, set up camp on the beach.

"At the time there were about seven of us sleeping on the beachfront," she says.

"As people started coming, I would just give away my camp – because I didn't want to see kids stressing, I didn't want to see them sleeping on the ground."

Since establishing the camp in 2004, Twinkle has transformed it into a more permanent home for around 250 people.

All members of the village are required to do community service – both inside the camp and in the surrounding public space – to keep the areas clean and safe.

John Isaac, 22, moved here four years ago, joining his parents who were already living in the camp.

"I was living on my own already," he says. "But the house I was living in was getting evicted."

John's mother is full of praise for Twinkle, calling her "the head of the spear".

"I'm not saying we are 100 per cent the solution," Twinkle says. "But we are part of the solution."

In her air-conditioned bedroom in the camp, Twinkle explains the daily challenges the community faces living here.

There is no running water, so water must be collected from public showers in the boat harbour. The camp is bathed in the constant whirr of generators to keep a limited supply of power on.

"We don't have that privilege of going in and turning on our lights, flicking that pipe to turn on our water," she says. "Yeah, here we bring in our own waters. We have generators."

But Twinkle and her inner circle have hatched a plan to change this – a plan for a slice of land to live on.

Taking back the land

In the long, green valley that stretches inland from the boat harbour, Twinkle is beaming with pride.

"For the last five years I kept telling people, 'This is going to be our home'," she says. "Five years I passed this gate and said, 'that is our home'.

"Well, this is our home. We are here."

Through a mix of donations and grants, Twinkle has bought a 8-hectare plot, which she has named Pu'uhonua Mauka.

It will be a permanent home for many displaced in their own land.

"It is amazing. I never thought I would be doing the things that I am doing today. I am able to help my family, you know, to be a little bit more productive," she says.

"The plan is building out our homes, bringing up people home, try to work towards being self-sustaining. And guess what, they all going to get running water!"

For Twinkle, her reward is seeing the next generation break the cycle of dispossession.

“My pay day is when my kids bring me home their diplomas,” she says.

“It might be a big sacrifice for me, but at the end it will be a reward – to see the accomplishment, to see the cycle that they are breaking, for their family. Yeah, yeah, that’s pay day.”

A cultural rebirth

For Pomai Hoapili, life is best lived in a state where "everything seems like surfing, or like flowing. That is the ultimate goal," he says,.

At his home on the North Shore, he's also focused on nurturing the next generation.

His 10-year-old daughter Wela is enrolled in a school that teaches the Hawaiian language. Pomai is also taking classes so they can speak to each other in Hawaiian as much as possible.

It's already bridging the generational divide. When Wela first spoke Hawaiian to her great grandmother, the old woman wept with joy.

"My grandma starts crying, sits down and cries a little bit," Pomai says.

"They took it away in three generations. We're going to get it back in one. Whatever it takes."

He believes Hawaiians are in the midst a cultural renaissance, if only those still calling the islands home can withstand the pressures forcing them out.

“Be Hawaiian, speak Hawaiian, live Hawaiian,” he says.

“The longer you stay alive, the longer people remember we're here. But if we stop down the line, people stop talking about us, we disappear. So, we got to keep practising."

Watch 'Keep Hawaii Hawaiian' on iview and YouTube .

- Photography, video and reporting: Matt Davis

- Additional drone: Allen Murabayashi @oahusurf

- Digital production: Matt Henry

- X (formerly Twitter)

- Indigenous (Other Peoples)

- Tourism and Leisure Industry

Our mission is to define, introduce, grow and sustain American Indian, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian tourism that honors traditions and values

Aianta newsfeed, american indian alaska native tourism association ceo appointed to u.s. travel association board of directors.

American Indian Alaska Native Tourism Association CEO Appointed to U.S. Travel Association Board of Directors The leading voice of the $15.7 billion Indigenous hospitality sector of travel and tourism in the U.S. continues to have a seat at the national tourism...

The Office of Indian Economic Development and American Indian Alaska Native Tourism Association Award Recipients for FY24 NATIVE Act Capacity Building Grants

The Office of Indian Economic Development and American Indian Alaska Native Tourism Association Award Recipients for FY24 NATIVE Act Capacity Building Grants Five recipients across the U.S. will receive funding for capacity building support to enhance and expand...

Adventures Through Careers in the Outdoors

Adventures Through Careers in the OutdoorsAdventures Through Careers in the Outdoors March 26, 2024; 10 a.m. (Mountain) Are you interested in sharing your Native cultural knowledge with the public? Are you passionate about the outdoors, conservation and learning new...

The U.S. Forest Service and AIANTA Select Recipients for FY 23 NATIVE Act Grants

The U.S. Forest Service and American Indian Alaska Native Tourism Association Select Recipients for FY 23 NATIVE Act Grants Six recipients across the U.S. will receive funding for tourism infrastructure and capacity building in Native American communities ALBUQUERQUE,...

AIANTA/ASU SustainableTourism Partnership: Information Session on Sustainable Tourism

AIANTA/ASU Sustainable Tourism Partnership: Information Session on Sustainable Tourism for Native Nations and Communities, Certificate ProgramWebinar: AIANTA/ASU Sustainable Tourism Partnership January 23, 2024; 10:00 A.M. (MT) In partnership with Arizona State...

Journey to Success: Navigating Indigenous Tourism Excellence through Self-Assessment

Journey to Success: Navigating Indigenous Tourism Excellence through Self-AssessmentJourney to Success: Navigating Indigenous Tourism Excellence through Self-Assessment January 16, 2024; 10 a.m. (Mountain) Designed for Indigenous tourism operators and leaders, the...

Introduction to Working With Mt. Rainier Concessions

Introduction to Working With Mt. Rainier ConcessionsIntroduction to Working With Mt. Rainier Concessions January 30, 2024; 10 a.m. (Mountain) The National Park Service works with concessioners to offer goods and services to park visitors. The concessionaires operate...

FY 2024 OIED/AIANTA NATIVE Act Capacity Building Grants Request for Proposals (RFP)

FY 2024 OIED/AIANTA NATIVE Act Tourism Capacity Building Grants Request for Proposals (RFP) DEADLINE EXTENDED NOW DUE JANUARY 16, 2024 Company NameAmerican Indian Alaska Native Tourism Association, Inc. (AIANTA) Address6000 Uptown Blvd. NE Ste. 150Albuquerque, NM...

15 Cultural Protocols to Know Before You Visit Native Homelands in the U.S.

Kicking off National Native American Heritage Month in November, the American Indian Alaska Native Tourism Association (AIANTA), the only national organization dedicated to advancing cultural heritage tourism in Native Nations and communities across the United States,...

View the AIANTA Blog now.

Invite Us to Speak at Your Event

Members of the AIANTA staff and Board of Directors are excited to speak at your industry event..

Please take a moment to complete our Speaker Request Form , so we can learn more about your needs.

Bureau of Indian Affairs

Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail

Native American Agriculture Fund

Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail

Bureau of Land Management

National Endowment of the Arts

National Park Service

United States Forest Service

Ready to be a part of the AIANTA story?

- About AIANTA

- Support AIANTA

How To Visit Hawaii Ethically And Responsibly

Save money on your next flight

Skyscanner is the world’s leading flight search engine, helping you find the cheapest flights to destinations all over the world.

With its beautiful beaches, lush rainforests, and vibrant culture, Hawaii is on many people’s bucket list of places to visit. However, its popularity as a tourist destination raises questions around sustainability and cultural sensitivity for those wanting an ethical vacation.

If you’re short on time, here’s a quick answer to visiting Hawaii ethically: Respect native Hawaiian culture by learning about it in advance, choose eco-friendly accommodation and tours, spend money at locally-owned businesses, avoid damaging environments like coral reefs, and educate yourself on issues locals face .

In this guide to an ethical Hawaii trip, we will cover choosing responsible tourism options, respecting native Hawaiian culture, supporting local communities economically, treading lightly environmentally, and taking historical issues into consideration.

Opt for Responsible Tourism in Hawaii

Book tours and activities from sustainable companies.

When planning your Hawaiian vacation, consider booking tours, activities, and experiences through companies that prioritize sustainability, support local communities, and protect Hawaii’s natural landscapes.

According to the Hawaiʻi Tourism Authority , over 10.4 million visitors came to the islands in 2019, putting strain on natural resources and cultural sites.

Seeking out responsible tourism operators is one way visitors can enjoy the islands while directly supporting conservation. For example, Holoholo Charters runs snorkeling tours utilizing strict eco-friendly guidelines to protect coral reef ecosystems.

The company’s captains educate guests on reducing environmental impact during ocean activities. Responsible companies like Holoholo also tend to hire local guides, providing economic benefits to Hawaiians.

In addition to protecting ecosystems, opting for sustainable tour providers promotes the preservation of native Hawaiian culture. Operators like Hawaiian Paddle Sports incorporate authentic cultural history into their tours.

Their guides share ancient traditions surrounding sports like outrigger canoeing, allowing visitors to engage respectfully with long-standing island practices.

Select eco-friendly and culturally sensitive lodging

Choosing the right hotel or vacation rental is another key element in sustainable Hawaiian travel. Seek out eco-certified accommodations dedicated to protecting the islands through renewable energy usage, waste reduction initiatives, locally-sourced foods, and employment of Native Hawaiians.

For example, the Four Seasons Resort Hualalai on the Big Island operates an onsite ray and shark aquarium providing research benefits. Their cultural center area offers classes like lei making, hula lessons, and ukulele playing.

Revenues generated go towards cultural education and sustainability projects benefitting island communities.

Vacation rentals can also promote ethical tourism through culturally sensitive offerings. The rental company Hawaiian Beach Vacation partners with the nonprofit Hui Aloha ʻĀina Momona to facilitate voluntourism opportunities for guests, such as beach cleanups, native species protection programs, and loʻi restoration work days to preserve ancient Hawaiin taro fields.

By consciously selecting responsible tourism providers for activities, lodging, and more, visitors play a direct role in sustaining Hawaii’s natural resources and native communities for generations to come.

Respect Native Hawaiian Culture and Traditions

Learn about the history and cultural customs.

Native Hawaiians have a rich culture spanning centuries with unique traditions, beliefs, and practices. Before visiting Hawaii, spend time reading about Native Hawaiian history, cultural stories, customs around greetings and protocols, and the spiritual significance of natural sites.

This knowledge will allow you to be more respectful and appreciate sites and experiences more fully during your trip.

Participate in experiences authentically

While in Hawaii, seek opportunities to genuinely engage with and learn from Native Hawaiian people, culture, and land. Consider attending cultural events hosted by Hawaiians, taking educational tours focused on Hawaiian heritage, shopping at stores supporting local Hawaiian artisans, or dining at restaurants serving traditional cuisine.

Participate mindfully by following proper etiquette and protocols. Avoid treating traditions like hula as spectator entertainment without context. The more visitors educate themselves and participate respectfully, the more Hawaiian culture will thrive.

Ask permission before visiting sacred sites

Hawaii’s islands contain many historic and sacred places of spiritual significance to Native Hawaiians. Visiting these unique natural sites without permission can be extremely offensive .

Places like temples, burial grounds, and geographic formations tied to Hawaiian gods may have strict guidelines around access, photography, and behavior.

Before going to sensitive areas, always consult proper local authorities to ask permission, learn protocols, get access, and receive a guided tour if possible for context. Acting as a respectful steward helps preserve Hawaiian culture and heritage.

Support Local Hawaiian People and Businesses

When visiting Hawaii, it’s important to ensure your tourism dollars go back into the local economy. Here are some tips for supporting Hawaiian-owned businesses and providing economic benefits to native communities:

Spend Money at Locally-Owned Shops and Restaurants

Seek out restaurants, cafes, shops and markets that are Hawaiian-owned. This infusion of money directly helps local families and preserves small businesses integral to communities.

A 2021 study found visitor spending at local establishments generated 2.5 times more income for Hawaii’s economy compared to non-locally owned tourism corporations.

Buy from Hawaiian Makers and Artisans

Purchase traditional Hawaiian arts, crafts and products directly from native creators and artisans. Attend cultural festivals, local craft fairs and farmers markets to meet producers.

This provides income and helps Hawaiian cultural practitioners preserve ancestral knowledge and livelihoods passed down generations. Look for the “Made in Hawaii” sticker.

Choose Tour Companies Owned by Hawaiians

When booking luaus, boat tours, hikes and other excursions, purposefully choose those owned by Hawaiians. This gives local people more authority over how their heritage is represented and means revenue goes back into the community.

Hawaiian-guided experiences also provide more authentic and educational encounters with the islands’ history and culture.

Making mindful decisions to economically support Hawaiian people and enterprises ensures Hawaii residents equitably share in tourism profits. It enables communities to thrive and have agency in how their home is portrayed and impacts them.

Tread Lightly and Avoid Environmental Harm

Don’t litter or damage ecosystems like coral reefs.

It’s critical that visitors respect Hawaii’s sensitive natural habitats. Trash like plastic bags, bottles, and straws can choke marine animals or leach chemicals into soils and waterways. Over 8 million pounds of debris wash up on Hawaii’s coasts annually!

Be exceedingly careful not to touch or break coral, which grows slowly—only 0.2 to 2 inches a year. Stand up paddleboarding and kayaking should be done in designated areas to avoid accidentally harming coral colonies with paddles.

Also read: Can You Take Coral From Hawaii?

Reduce plastic waste from your trip

Plastic waste is a huge problem across the islands. Visitors should aim to avoid single-use plastics like bottled water, plastic bags, straws, and to-go containers. Bring reusable bags and bottles. Choose tours, hotels, and restaurants that reduce plastic waste.

For example , Trilogy eco tours serves food buffet-style rather than using single-use dishware.

The state has strict laws banning common pollutants like plastic bags at grocery checkouts and plastic straws at restaurants and bars. Mahalo for supporting Hawaii’s sustainability efforts by following these regulations during your stay!

Choose reef-safe sunscreen

Many typical sunscreens contain ingredients that bleach and kill coral reefs , which provide invaluable coastal protection, among other ecological services. Hawaii has banned products with oxybenzone and octinoxate, which are frequent culprits. Use mineral or non-nano zinc sunscreens instead.

Brands like Badger and Stream2Sea make great reef-safe options.

By taking care to tread lightly, we can preserve Hawaii’s unparalleled natural majesty. Follow leave no trace principles and avoid harming ecosystems and wildlife . Consider offsetting flights’ environmental impact by donating to conservation groups like Mauna Kea Watershed Alliance that protect endangered native species.

Understand Complex History and Land Issues

Learn about the overthrow of the hawaiian monarchy.

In 1893, a group of American businessmen and plantation owners, with the support of the U.S. military, overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy . Queen Lili’uokalani was deposed, ending the Hawaiian Kingdom. This complex history has lasting impacts today.

When visiting Hawaii, take time to learn about the overthrow and its long-term implications for native Hawaiians.

Also read: What Happened To The Hawaiian Royal Family?

Consider indigenous land rights in your activities

Many attractions and hotels in Hawaii sit on land that originally belonged to native peoples. As you plan your vacation, research who owns the properties you’ll be visiting and consider how they have impacted native communities . Seek out indigenous-owned businesses to support where possible.

- Nearly 1.4 million acres in Hawaii could potentially be reclaimed as native Hawaiian lands , according to a state-commissioned study in 2022.

- Organizations like the Hawaiian Community Assets nonprofit work to help native Hawaiians reclaim ancestral lands.

Be respectful discussing sensitive topics

Certain parts of Hawaiian history, like the overthrow, annexation, and cultural losses, are very sensitive subjects. Be thoughtful discussing them . Recognize and respect the intergenerational trauma faced by many locals . Consider:

- How would I feel if outsiders took over my homeland?

- What losses would my family and community experience?

Let this perspective guide you as you seek to understand Hawaii’s culture and people. An open, learning mindset goes a long way.

Also read: How To Visit Hawaii Without Being A Colonizer

By being thoughtful in choosing tourism businesses, respecting native culture, supporting local economies, protecting fragile ecosystems, and educating yourself on complex Hawaiian history, you can ensure your trip aligns with ethics around sustainability and social responsibility.

An ethical Hawaii vacation allows you to fully appreciate all the islands have to offer, while making positive impacts on Hawaiian people and lands that will preserve them for future generations. With some mindful planning using these tips, you can check Hawaii off your bucket list the right way.

Sharing is caring!