The 7 Basic Plots: Voyage and Return

by Liz Bureman | 25 comments

Free Book Planning Course! Sign up for our 3-part book planning course and make your book writing easy . It expires soon, though, so don’t wait. Sign up here before the deadline!

I recently re-read The Phantom Tollbooth , which was one of my favorite books in grade school, and still holds up fairly well ten-to-fifteen years later. If you haven't read it, I highly recommend it, but it largely centers around a boy named Milo who is convinced he lives this boring life and is content to just slump his way through it, until one day there is a mysterious package waiting for him when he gets home, which contains the titular tollbooth. Milo assembles the tollbooth, gets in a toy car, and suddenly is in a magical land of logic, numbers, words, ideas, and more puns than you can shake a stick at. He makes some friends, goes on a Quest, becomes a hero, and returns home a little more mentally stimulated and less bored.

This structure is the cousin of the Quest : the Voyage and Return.

Photo by Mike Baird

Want to learn more about plot types? Check out my new book, The Write Structure , on sale for $5.99 (for a limited time!). It helps writers like you make their plot better and write books readers love. Click to get the book .

The Voyage and Return is very common in children's literature because it generally involves a journey to a magical land that pops up out of nowhere. The magic element is pretty sunny and light to start with, and then the darkness shows up for the hero to conquer. Once it's vanquished, the hero leaves the magical land and returns home, probably having learned a valuable lesson, or having discovered something about themselves that they didn't know before.

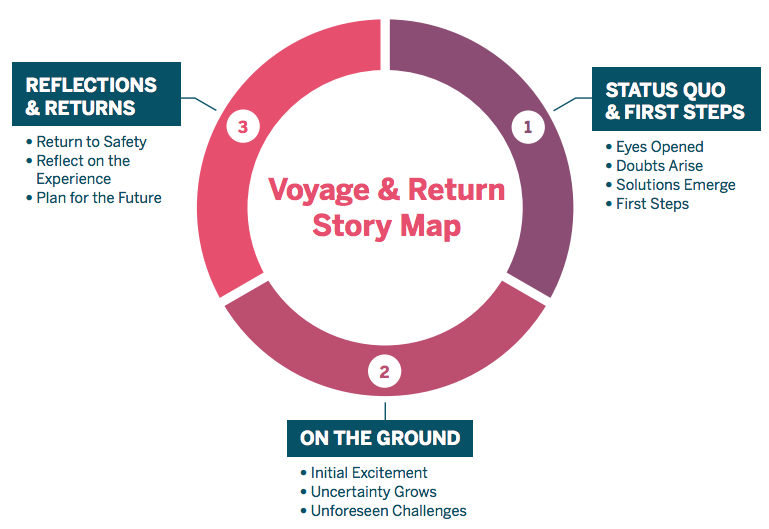

Here are the five stages of the Voyage and Return:

1. Anticipation Stage and “Fall” into the Other World

We see the protagonist in their dreary, dull, humdrum life, and then all of a sudden, something happens to escort them to the other world. This could be a rabbit hole, a wardrobe, or just a blow to the head, and the protagonist regains consciousness in the other world.

2. Initial Fascination or Dream Stage

Wow, the clouds are made of cotton candy! Or there's a talking rabbit! Or everything is suddenly colored in ways that it shouldn't be! Our hero is aware of the fact that they are no longer in Kansas, and they take the opportunity to explore their surroundings and the strange laws of physics that might be in this new place. However, no matter how awesome the new world is, Booker notes that the hero never feels completely at home there, foreshadowing their return.

3. Frustration Stage

This is where the dark magic starts to creep in. The hero starts feeling a little more uncomfortable, and the wonder of the world starts to feel a little more oppressive. In The Phantom Tollbooth , this is where Milo and his companions start heading towards the Castle in the Air, over the Mountains of Ignorance, and they start meeting the demons of the Lands Beyond. Chaos hasn't completely set in, but things are looking more sinister for our hero.

4. Nightmare Stage

The Queen of Hearts has unleashed her armies, Aslan has been killed on the Stone Table, and Dory is stuck in a net with a bunch of tuna. For the love of all that is good and holy, our hero better run for his life, because the shadowy element of the magical land is coming in full force.

5. Thrilling Escape and Return

We can all breathe a sigh of relief, because the cavalry has arrived! Our hero has escaped from doom and makes the return home, having learned a valuable lesson about their home or themselves.

In addition to The Phantom Tollbooth , other examples of Voyage and Return plots include Alice in Wonderland , Finding Nemo , and most of the Chronicles of Narnia series. It's usually a good idea to implement some character development in the protagonist over the course of the voyage, because otherwise, what was the point of the exercise?

Get The Write Structure – $9.99 $2.99 »

Write a story following the Voyage and Return structure.

Write for fifteen minutes. When you're time is up, post your practice in the comments section. And if you post, please be sure to give feedback to a few other writers.

Happy writing!

(Some of the links above are affiliate links and help support this community. Thanks!)

Liz Bureman

Liz Bureman has a more-than-healthy interest in proper grammatical structure, accurate spelling, and the underappreciated semicolon. When she's not diagramming sentences and reading blogs about how terribly written the Twilight series is, she edits for the Write Practice, causes trouble in Denver, and plays guitar very slowly and poorly. You can follow her on Twitter (@epbure), where she tweets more about music of the mid-90s than writing.

25 Comments

One of my favorite books with the Voyage and Return theme to it is “The Neverending Story” by Michael Ende. Possibly one of the most creative books I have ever read.

Great book!

I love that book too.

With all due respect, I want to raise my hand, as I was inclined to do in school, and yell, “Wait a minute, wait a minute!” Your Nightmare stage is misleading–it’s supposed to be a nightmare for the protagonist. You mention that so and so is killed and others trapped, and so the hero runs. (How un-heroic.) No, the nightmare is all about the hero’s very personal loss. He is somehow dying. Only by “dying” does he/she earn the authority to return home renewed, embodying a wider worldview, a higher cause. I’m not saying that some stories don’t unfold as your template suggests, but they’re inferior stories. I’m on a bit of a mission to make sure that this “dying” doesn’t go unnoticed. It’s what I call the heart of the story. Btw… my teachers never knew quite what to do with me and my interjections. But for every detention I earned, I had at least one student tell me afterwards, “Jeez, I’m glad you said something because I didn’t get it.”

I am glad you posted as your statements make us think. However, losing someone you love is harder than dying yourself especially if you were the cause of the death. I think the Aslan example was perfect.

I think you’re absolutely right. Losing someone could indeed be worse… which might be just the event that causes one’s psychic “death”. I think that happens all the time in real life… the death of a loved one jolts us into a new way of living our life. Thanks, Cat.

ew… as far as I can see you don’t even participate so why are you wasting space. I get that you’re published but any monkey can be “published” these days. Maybe it is you that needs the practice PJ Reece.

Belinda, I am revisiting the Write Practice, and was surprised to see your comment. PJ Reece has been on the Write Practice since way before me, and I first visited and participated about a year ago. I have recently been more involved in actual writing (rather than 15 minute practices) and in Joe’s Story Cartel, but come back every once in a while to my first love, the write practice :-).

During the time I was a regular participant, what I enjoyed about the course was the positive attitude and the courteousness of the participants. We are free to offer our opinions here, in fact, it’s encouraged, and not usually considered wasted space. We can all grow from hearing what others have to say.

And BTW, I have read some of PJ Reece’s writing, and he’s no monkey 🙂

I think “Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory” follows this plot type, too. The candy factory is a “magical land” in children’s eyes. When they disobey and try the experiments, you see the dark side of its magic.

Good point.

This took a bit longer than 15 minutes, and I’m not sure how well it fits the form. But I had fun 🙂

Yawn. Jack glanced at the clock. Only half way through World History, really? His teacher was droning on about the Renaissance something or other. He scanned the class and saw the usual kids in rapt attention near the front. Mrs. Riley usually had all her focus on that section, rarely glancing back to this corner with Jack and his few friends, and certainly not trying to get any of them to interact. She called this corner the “black hole”, because any knowledge that drifted back here would never be seen again.

Chin resting on his right hand, Jack looked over his doodles again. He’d have to start a new page soon. Today’s characters seemed more interesting than usual, though. There was a fire-breathing dragon giving the evil eye to a knight approaching on foot in the distance. Several bunnies were hopping away in terror, all but the one who was now a smoking ruin. The oak tree between dragon and knight couldn’t go anywhere and his expression said, “Firewood!”.

Jack started to draw a rain cloud for the tree, but for some reason the cloud looked more like a hole in the paper. He stared at whatever it was, a portal maybe, and it started to wiggle. Jack started to move also, feeling his weight shift up out of his chair. In a blur he was sucked into the portal. There was a moment of darkness then he landed hard on his back, arms and legs splayed out.

He looked up and saw a sky, sort of. It was an even white like cloud cover, but had blue lines running across in even intervals. He looked to his right and saw he was sprawled next to an oak tree, which twisted its trunk around and used a branch to help Jack rise to his feet. Just as he said, “Thanks”, a bunny hopped past and yelled “run for it!”.

Jack smelled smoke. He heard and felt a pounding that seemed to be heavy footsteps. Stepping around the tree, he saw a gigantic dragon coming straight for him. Now he was getting the evil eye and the dragon was taking a deep breath. He heard a clanking sound behind him and was knocked off his feet back behind the tree. A bunny hopped in close to him for shelter as he heard deadly sounds beyond the tree. Roaring, clanking, yelling, anguished cries, that sort of thing.

And then, silence, for a few moments. Jack heard the clanking again and a knight appeared around the tree.

“I say, are you all right?”, the knight said. He helped Jack stand up again.

“Yeah, I think so.” Jack looked at the dragon, now a smoking ruin himself. “Did you really kill that thing?”

“Yes I did. Got here just in time, did I not?”

“Yup, otherwise I would have been toast. Am I really where I seem to be?”, Jack said.

“Yes you are, young man, and it is time for you to go back. Come with me.”

The knight, with Jack following, walked over to a certain part of the field and looked up. Jack looked up too, seeing what appeared to be a hole in the sky.

The knight said, “That’s it, then. Good day to you.”

And he grabbed the back of Jack’s shirt with one arm and threw him up in the air, all the way through the hole.

Jack landed back in his seat. Mrs. Riley was still droning on. He looked at his page of doodles and saw a puff of smoke come out of the portal. Was he losing his mind? Did anyone see any of this?

There was no reaction from anyone else in the black hole, but they all appeared to be asleep anyway. Jack scanned the front of the class and saw Janice looking at him. She held up her pencil and wiggled it at him, then winked.

That was fun to read. “The Black Hole”–nice! I like how the knight just kinda tosses him back up. Good practice.

Thanks, Karl. I was trying to think of how to get Jack out of there, and finally just had the knight give him the heave-ho!

I was in a cute mood, for some reason. Hardly ever happens 🙂

Unbridled creativity. I love the reiteration of the drawing coming to life.

I want to read more!! Please!!!

This may not seem like it fits but when I started writing I planned to have my guy walk through the door of the place and fall into a void, and then land in another dimension so-to-speak. I just didn’t get that far 🙁

Jones the philosopher said, “A relationship is like a candle; one strong gust of wind will extinguish it.” I wish my relationship with R. were simple as a candle. I would rather liken our situation to a house fire; the stronger the wind blows, the bigger the flames get. Along with more destruction and flames engulfing more shit and yadda yadda yadda. I tried to end my relationship with R. I tried to burn the bridge between us and preferably with R. halfway across and me safe on the other side.

The neighborhood I found myself in bore resemblance to a mid-century industrial park. Rusty warehouses and empty lots and buildings with little paint remaining but bountiful in the broken window department. I trudged along, hoping to get through as soon as time would allow. Pack slung on my tired back and head down facing the littered pavement, a drawn and prolonged creak of rusty metal drew my attention up. A train rolled. It moved slow, as if the world knew I wanted nothing else than to keep moving forward and said, “Ha! M. is in a hurry. Quick, Jeeves, cue the delay train!” And Jeeves, whoever he is, closed his eyes, nodded and said, “Of course, sir. The train will be in M.’s way shortly.”

I watched rusty car by rusty car pass before my eyes. Between them I looked to the other side of the tracks out of curiosity, or perhaps boredom, either way the view was less than perfect. I did see a window alight with a yellow aura, the glow pallid in the dusk. I caught glimpse and of course waited so I could look through the space between the cars. The tracks which the train rolled curved beyond my vision and I couldn’t foretell the length. I dared not lie down, however, the atmosphere gave me a less than comfortable feeling. Somewhere between anxiety and fear, I would say.

With the train creaking before me; squeaking; clanking; my ears became sore. The train hurt my ears and painful as it was, I couldn’t bring myself to cover them with my hands or anything else. In light of the blighted streets I found myself passing, to take away my hearing seemed less than favorable. Had I covered my ears the world may have summoned Jeeves again. “Oh Jeeves! M. is covering his ears. Cue the crowbar-wielding mugger/rapist!” And Jeeves would close his eyes and say, “Of course, sir. Mugger/rapist on the way to trap M. between a crowbar and a train.” I hated the world. If I ever met Jeeves I resolved there, waiting for the train, that I might break his nose with a stone.

As I cringed, my pain threshold dangerously near to its breaking point, the last car of the train rolled by. Nothing stood between myself and the window alight with life among this lifeless—this almost forgotten world.

I really like the tone of this story. It’s clever, vivid, and fun.

The book Gulliver’s Travels would fit in this category, too.

Hi Liz.Thank you for your article. Thanks for reminding me of Jason and the Argonauts of Greek Mythology fame. He and his story is native to the story tellers art.

I don’t see how this is fundamentally distinct from the Quest.

I left. I went as far left as the Earth would take me. I left a long, long time ago. Now I sit, planning a return. A return to the right…is it the ‘right’ side of life, or just a ‘right’ turn in life? With each return there is this query.

There seems so much to do…so much to plan. The exhilaration causes sleepless nights. So many people, so little time. So many places. I want to see the creek where we caught crawdads, and scooped up tadpoles. I want to see him again too. Sadly they say he is semi immobile, and only comes out for certain events and/or people. Still, I remember when he came to Dad’s funeral. I stopped where I was. They helped him to a chair. I rushed to his side, kicked off my shoes and sat down straight on the floor at his feet. He was the King again, and I was his loyal subject.

We sat for hours, until unapproving eyes caught my attention. Bastards, what did they know of our bond…how insensitive for them not to notice my appreciation of the living. I have no room for mourning stiff bodies, it’s life I crave…life I’ve always craved. How different that set me apart.

Suddenly his companion recognizes the odd glances, and retrieves his ward. We have the typical exchange of goodbyes, even make plans for a lunch we all know might never happen. Still, we make these plans in detail absent any future contact information. It is not a formality, but something we all realize we can make happen with just a desire to do so.

The return has been implemented. The tickets purchased. The rental car reserved. Even the purchase of a laptop to make remote working a possibility…

“The cavalry has arrived” implies that the hero didn’t solve his/her problem but some outside force did. The hero has to learn his or her lesson in order to solve the problem. Solving the problem, usually, is proof that the hero learned something going through these fantastic events. Dorothy can’t go home until she learns there’s no place like home. If the Wizard did it for her the story would lose all it’s meaning. As the fairy said, “Silly girl you could go home whenever you wanted too. The witch, and wizard, and flying monkeys were only here to entertain movie goers. You just need to agree to never leave the breeding farm. Your agreement will be recorded and serve as a legally binding contract in the state of Kansas.”

Cyrus served his customer a kebab, like any other. But this was no ordinary customer.

“You are wicked, sir,” said the customer.

“Wicked in what way?”

“You have short-changed me.”

“Um … have I? Let’s-”

“ENOUGH! I have been warned of you – and now I see for myself it is not mere gossip. I have powers beyond your realm, beyond your wildest imagination.”

All of a sudden the kebab shop faded away. Shapes and malformed colors swirled back into focus, and their surroundings had formed into something new.

Piles of coins and skewers of meat adorned the landscape. This was clearly a place of interest to both Cyrus or any customer of his.

For a while he was happy. Both the Mysterious Customer and Cyrus ate and counted their money as though it were all that mattered. But the Mysterious Customer had unjustly taken Cyrus prisoner from his real home. And that made him sad.

“As much as I love this magical land, I swear I had no actual intention of short-changing you, even if I did do that.”

“IF you did? But you DID”.

“Okay, fine! ‘As much as I love this magical land, I swear I had no actual intention of short-changing you … AND I DID!”

The kebab shop reappeared and they were back where they were.

“The customer is always right.”

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

Story Empire

Exploring the world of writing, basic plots: voyage and return.

Today’s post covers the basic plot type Voyage and Return.

This plot sees the protagonist go to a strange land and face adversity on his way home. His travels are fraught with peril, but eventually he returns and is changed by the experiences he’s had and what he’s learned from them. One notable feature of his return is the emotional reaction. This plot type DOES NOT guarantee a happy ending; only a change in the character.

You may notice similarities to the Quest plot type. That’s because the two closely mirror each other. The main difference is that the Quest storyline ends when the object of the quest is attained (there is no return home).

Here is a list of common Voyage and Return stories.

- Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland/Through the Looking Glass

- The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

- The Chronicles of Narnia

- Goldilocks and the Three Bears

- Gone with the Wind

This is the basic template for writing a Voyage and Return story. I’ll use The Wonderful Wizard of Oz as my example.

- Anticipation Stage and “Fall” into Another World In this stage, we witness the protagonist in her dull, humdrum life. Then something happens to transport her somewhere else. It could be a portal, a walk in the woods, a fall, a cyclone… The mechanics don’t matter. In The Wonderful Wizard of Oz , Dorothy’s life in Kansas is gray and boring. The biggest excitement she faces is the argument with Almira Gulch. She runs away to protect her dog, then a cyclone comes. Whether you believe the cyclone carries her away or her journey is a mental one resulting from a head injury, this is when/how she enters another world.

- Initial Fascination or “Dream” Stage Initially, this stage is wonderful. The protagonist sees and experiences a life that’s beyond her expectations. While the reader is taken with the beauty or pageantry of what is experienced here, the main character—though enamored with what she is experiencing—has a small sense of unease. This can be quite subtle, but it needs to be there to foreshadow the protagonist’s journey and eventual return. Dorothy is delighted with the Munchkins in Munchkinland, and she even develops a bond with Glenda. But through it all, even before the threat from the Wicked Witch of the West, she is bewildered by where she is and what the world is like. She is an outsider; she doesn’t fit in. And that leaves her feeling uncomfortable, even among her new “friends.”

- Frustration In this stage, things take a turn for the worse. The protagonist is faced with one problem after another, and every time she overcomes an obstacle, she’s left with a bigger problem. Dorothy is making friends to help her on her journey, but she’s also encountering more than her share of problems. The Wicked Witch scares her in the forest and puts her to sleep in a poppy field. She finally reaches Oz only to initially be turned away then finally sent on an impossible mission.

- Nightmare This is the protagonist’s darkest hour. Escape seems unattainable and not only is her failure imminent, her life is on the line. Dorothy is captured by the Flying Monkeys and taken to the Wicked Witch. An hourglass counts down the remaining minutes of her life, and she is alone with no means of escape.

- Thrilling Escape and Return This is the payoff. What the readers have stuck around for. At this stage, the protagonist pulls off the impossible and escapes her doom. She learns a vital lesson, then returns home. Dorothy melts the Wicked Witch and takes her broomstick back to the Wizard so he’ll send her home. In a last heart-wrenching twist, she learns he doesn’t have the power to send her back, and she is devastated. Then Glenda appears and reveals Dorothy had the power to return all along—she just had to learn her lesson first. Reciting “There’s No Place Like Home” like a mantra, she’s transported back (or wakes from being unconscious) and has a new appreciation for her life.

In Dorothy’s case, the ending was happy. But remember, it doesn’t always have to be. Scarlett O’Hara is abandoned by everyone. Goldilocks had a close call with a bunch of bears. The important thing is that they learned something about themselves and are stronger for having gone through the experience.

Have you written a Voyage and Return story? Or do you have a favorite that you’ve read? Let’s discuss it.

Share this:

49 thoughts on “ basic plots: voyage and return ”.

Thank you for this excellent tutorial. I’m learning a lot about the different plot structures. Much appreciated. ❤

Like Liked by 1 person

Glad you’re finding it useful, Colleen.

You guys put out a lot of useful information. It’s much appreciated. ❤️

Knowing people find it useful is why we do it. Thanks for saying so.

Great information! Thank you for following my blog.

I’m glad you found the information useful.

Pingback: 7 Basic Plots: Voyage and Return – Island Bookworm Conversations

I typically don’t write voyage plots but may give it a try. Thanks for sharing.

Glad the post got you thinking, Michele.

Pingback: The Week In Review | Joan Hall (Blog)

Pingback: Author Inspiration and This Week’s Writing Links | Staci Troilo

Reblogged this on Anna Dobritt — Author .

Thanks for sharing, Anna!

I’ve not written a voyage and return plot. But I also thought about Tolkien and Lord of The Rings (as well as The Hobbit). Great series of posts, Staci!

Thanks, Joan!

Reblogged this on Author Don Massenzio and commented:

Check out this great post featuring the voyage and return basic plot from Staci Troilo on the Story Empire blog.

Thanks for reblogging, Don!

You’re welcome.

There are a lot of books that can be mentioned, one of which is The Count of Monte Cristo, though it might also have elements of rebirth in it. Alice in Wonderland is an excellent example. The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings are both top examples in fantasy.

Only you and Charles mentioned Tolkien. I figured people would be shouting it from the rooftops. The others you listed are great examples, too.

As I’ve prepared these posts, I’ve noticed many stories combine plot types, which I just love. I think it makes them rich and interesting. On the other hand, there’s something powerful about a pure plot type. I guess if a story is written well, I’m happy to read it whether it breaks or follows traditional norms.

You may be right on both counts.

Reblogged this on Archer's Aim and commented:

I have written this plot for The Bow of Hart Saga (it’s more than a quest). See what Staci Troilo share about the voyage and return plot on Story Empire today.

Thanks for sharing, P.H.

This is a great series of posts and so informative! I don’t think I’ve ever written a voyage and return. Way back in the day, I used to write fantasy, but those were quest plots. I like the way you break out the various stages with explanations. Excellent job, Staci!

Thanks, Mae. I rather like this plot type. I’m tempted to try to outline one and see what happens. If only I had the time…

The ever elusive phantom . . . 😉

This made me think of The Odyssey, too. Odysseus mostly went to Troy because his brother decided he should, though. They all expected to return rich, so I guess that was a motivation, too:)

Like Liked by 4 people

The Odyssey fits, for sure. I don’t think the motivation matters; only that the journey is undertaken. (And money is a great motivator!) 🙂

My series is a voyage and return type of series. It is nowhere near as epic as Narnia, LOTR, or Oz (LOL), but I think it still falls into that category. My main character, Sofia, is whisked away to another world where she needs to learn how to become the savior of the people of that world. Her life is turned upside down multiple times. Her faith and her belief in herself in challenged, and she has to make difficult choices. In the end, she (and the other characters) grow stronger and come to terms with their lives.

Like Liked by 3 people

That absolutely fits. Particularly the part about the character arc. That’s very important in this plot type.

Excellent, Staci. I’ve read stories where there has been a combination of two basic plots. Thanks for sharing!

I love mixing types, Jan. In everything. In fact, I think my novels are all genre mashups. I tend to find the combinations more interesting. 🙂

Like Liked by 2 people

I love this. I don’t think any of my stories fit the mold exactly. Yak Guy doesn’t return home, for instance. His might be more of a quest. My new one will involve a return home, but not like you’ve described. I always thought the classic version of this one was The Odyssey. It’s all about the return trip though, and not necessarily about the magical land they return from.

The Odyssey is the quintessential Voyage and Return. That’s why I didn’t include it; I figured it was a given. I think you’re right about Yak Guy—his story is a quest. And now you have me intrigued about your new story…

He’s going to return home with fire and cannons blazing. It will be a place he cannot stay.

Well, that’s kind of heartbreaking. I hope he finds a place on his travels that he’d like to call home. (I think my heart’s just a little tender today.)

I may just allude to it. I’m not fond of long denouements. The hard part is how he’s going to keep sailing after the big event. Hearth and home vs piracy.

That would be a conundrum for a family-oriented pirate.

Pressed This on: http://harmonykent.co.uk/basic-plots-voyage-and-return/

Thanks for sharing, Harmony.

I think that my first ever book, a classic fantasy, definitely also was a quest, and some of the characters did experience the voyage and return … not all of them, though! Thanks for another great and informative post, Staci! I’m loving this series and am off to check out Christopher Booker’s Seven Basic Plots 🙂

I love that you mixed a Quest with a Voyage and Return. That makes the character arcs quite intriguing. So glad you’re enjoying this series, Harmz.

My mind went right to The Hobbit for this one. I can’t say I’ve ever done this idea. Seems I rarely have my characters return home, so I only get the voyage part. What if they take their home with them like a vehicle they live out of?

Hmm… Interesting, Charles. Perhaps a twist on a quest? (Now all I can picture is the Big Fat Rolling Turd from the Robin Williams movie.)

Not sure I remember that movie. Definitely makes for an odd visual. It could be another version of the Quest since the two categories are so similar.

It was a cute movie. Not his best (by far), but it had some quotes and some visuals that my kids love. https://youtu.be/_QPNqxHbC8o

Reblogged this on anita dawes and jaye marie .

Thanks for sharing!

We'd love to know what you think. Comment below. Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Six Ideas for Teaching Point of View

Basic Plot Structure – Comedy

Basic Plot Structure – Voyage and Return

- By Gay Miller in Literacy

September 24, 2018

Click on the button below to follow this blog on Bloglovin’.

Clipart Credits

Caboose Designs

Teaching in the Tongass

Chirp Graphics

Sarah Pecorino Illustration

© 2024 Book Units Teacher.

Made with by Graphene Themes .

7 Types of Stories: Voyage & Return

Writing software you'll actually love

Outlining tools

Advanced goal setting

Project templates

Collaboration

Compare plans

The "Voyage and Return" plot is one of the classic story archetypes identified by Christopher Booker in his book The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories . "Voyage and Return" stories involve the protagonist embarking on a journey to an unfamiliar world. They face a series of trials throughout their journey before returning home, often changed or enlightened by their experiences.

This structure is seen in many classic and contemporary stories, ranging from ancient myths to modern fantasy and science fiction. The contrast between the protagonist's ordinary world and the new world they discover allows for exploration of themes like growth, the unknown, and the concept of 'home.'

Common tropes and elements

- The Anticipation Stage and 'Fall' into the Other World : The story begins with the protagonist's anticipation of something exciting or unusual happening. This is followed by a 'fall' or transition, sometimes literally, into another world.

- Initial Fascination or Dream Stage : Upon arrival in the new world, the protagonist is initially intrigued by the differences they encounter. This stage is often characterized by wonder and a lack of real danger.

- Frustration Stage : As the protagonist becomes more familiar with the new world, they encounter problems or challenges that create frustration or conflict. The novelty of the new world begins to wear off, and the reality of the challenges sets in.

- Nightmare Stage : The protagonist's problems intensify to a crisis point, often culminating in a life-or-death struggle. This is the climax of the story, where the protagonist must use all their wits and skills learned on their journey.

- The Thrilling Escape and Return : The protagonist escapes from the alternate world after their climactic ordeal, often chased by some threat from which they barely escape.

- Reflection and Realization : Back in the familiar world, the protagonist reflects on their journey and experiences. They often have a new understanding or appreciation for their home and life.

- Application of the Boon : If the story is to have a lasting significance, the protagonist must bring something back from their journey—knowledge, wisdom, happiness, or a physical token. This often results in a better life for the protagonist or those around them.

- A Changed World or a Changed Perceiver : Upon the protagonist's return, either the world has changed because of their journey, or they perceive it in a new way, armed with the knowledge and experiences they have gained.

Example stories to draw inspiration from

This type of story can be found across many genres.

- "The Chronicles of Narnia" by C.S. Lewis : The children in this series travel to the magical land of Narnia, where they face challenges and grow as individuals before returning to their own world.

- "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland" by Lewis Carroll : Alice travels down the rabbit hole to Wonderland, a place of nonsensical rules and characters, and after her adventures, she returns to her ordinary life.

- "The Hobbit" by J.R.R. Tolkien : Bilbo Baggins goes on a journey to recover treasure guarded by a dragon and returns to the Shire with a new sense of his capabilities and a treasure of his own.

- "Gulliver’s Travels" by Jonathan Swift : Lemuel Gulliver experiences various strange lands and societies, each providing a satirical commentary on English society, before returning home each time.

- "Peter Pan" by J.M. Barrie : Wendy and her brothers travel to Neverland with Peter Pan, have adventures with pirates and fairies, and eventually return home to London.

- "The Time Machine" by H.G. Wells : The Time Traveler ventures far into the future to see the fate of humanity and then returns to his own time to share the tale.

- "The Wizard of Oz" by L. Frank Baum : Dorothy is transported to the magical land of Oz and, after many adventures with her friends, finds her way back to Kansas.

- "Outlander" series by Diana Gabaldon : Claire Randall is transported back in time to 18th-century Scotland, becomes involved in the historical events of the time, and must navigate her way back to the 20th century.

Related posts

You should be writing, but since you're here why not read more articles on this topic?

7 Types of Stories: Rebirth

7 Types of Stories: Tragedy

7 Types of Stories: Comedy

The Seven Basic Plot Points

Stories tend to work for a reason. The structures of beloved stories breed a certain familiarity we’ve come to know and love. Whether it’s a romance, a mystery, or a pulse-pounding action adventure, there are specific archetypes that simply ring true for readers and feel just like that comfortable sweater you love snuggling into.

Penned by Christopher Book in 2004, The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories is a Jung-influenced analysis that offers a psychological assessment of stories and why they work. The seven basic plot points offer perhaps what is the most open-ended of the structure archetypes you’ll encounter. They are broad, high-level descriptions that you’ve seen in stories across many mediums many times already.

What are the seven basic story plots?

The basic tenet behind the seven plots is simple: Book (as in Christopher Book—what a fitting last name) posited that all stories conform to one of these seven types in some way. He also maintained each of the plot types could then be further broken down into five stages known as anticipation, dream, frustration, nightmare and triumph.

Below, we’ll discuss what the seven types of plots are, outline the five stages of each one, and give examples of stories that use each kind.

Overcoming The Monster

In this plot type, your hero is tasked with overcoming some type of (usually) evil entity that may or may not be a physical monster that threatens your hero’s home. You know how it goes. The shark is eating the locals. The blight is destroying the land. Only your hero can fix this. We can look at the overcoming the monster plot divided into these five stages:

- Anticipation—The hero learns about the existence of the monster and its powers to destroy their home. The hero accepts (after some hemming and hawing, of course) the call to defeat the monster.

- Dream—The hero thinks about and prepares to fight the monster. Cue Rocky training montage. While the threat is still a speck in the distance, that is about to change.

- Frustration—The monster has arrived and oop… it’s a doozy. How is that thing so huge, anyway? And where does it keep all those teeth? This hero is in way over their head.

- Nightmare—It doesn’t get much worse than this. Battered, bloody, and broken, your hero is basically toast. (But we all know that’s not really true.) It’s the moment when everything is about to turn around.

- Triumph—That monster is ding dong dead and your hero emerges victorious. Somehow, they’re much smarter and better looking, too, and of course, the person they had their eye on notices. (Okay, that last part isn’t a requirement, so go where the spirit moves you.)

Examples of stories that use the overcoming the monster plot type are: Star Wars, Beowulf, Dracula, The War of the Worlds, James Bond, Avatar, King King, and Jaws .

Rags To Riches

In this archetype, your wayward hero gains something they didn’t have before, be it money, power, fame, or something else (wink, wink). But lo-and-behold, then they lose it (this might be their fault, it might not) and must get it back again.

We can divide this plot style into the following stages:

- Anticipation—Your main character’s life sucks. They’re poor, they’re weak, they’re not that smart, or they live at the bottom of a well or equally wretched place. Basically no one wants to be them. Especially not them.

- Dream—Of course, just when they think they can’t get any lower, that’s when the call comes and they’re forced (or maybe they make the reluctant choice) to go out into the world. While things are looking up, this is going to be short-lived.

- Frustration—Very short-lived, because this is when something arrives to get in the way. Maybe it’s an evil entity or their own personal demons. Maybe they just have no luck when it comes to rolling the dice.

- Nightmare—That’s it, it’s all on your hero now. There is no one coming to help them. Fairy Godmothers aren’t real (or are currently indisposed) and only they can overcome the final hurdle to achieve their desire.

- Triumph—Success! They kiss. They gain fame and fortune and live happily ever after in far better conditions than when they started. (Hopefully they remember their roots and go back to visit that well from time to time, though.)

Examples of stories that use the rag-to-riches plot type are: Cinderella, Aladdin, Jane Eyre, Ready Player One, Red Queen, and Throne of Glass.

The quest plot style includes a hero who must obtain something, reach a location, or fulfill some other task while meeting with plenty of obstacles along the way. There’s a good chance they’ll have some friends along for the ride, as well.

This plot style is divided into the following stages:

- Anticipation—This is the call. The moment. The heralding of something big to come. Basically, this is your kickoff point or inciting incident.

- Dream—The journey has begun, and it’s not all smooth sailing because that would make for a very dull story, indeed. As the protagonists move towards their goals, things get in their way. Killer bees. Poisonous flowers. Wicked Witches. Whatever you’ve got, throw it at your hero (and their friends if they have friends along—the friends are not exempt from torture).

- Frustration—They’re so close they can taste it. Their quest is almost over. Except it isn’t. Something is going to get in the way and make it just that much harder. (They didn’t think it would be that easy, did they?)

- Nightmare—This is the ultimate test. They’re facing the horde. Dangling over the lava pit. About to slay the dragon. And the good news is they do. Obviously, or this would be a tragedy (more on that later).

- Triumph—Way to go, everyone. Quest achieved!

Examples of stories where you’ll find the quest plot type include: Lord of the Rings, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Finding Nemo, Watership Down, The DaVinci Code, Underground Railroad, and A Wrinkle in Time .

Voyage & Return

In this plot type, your hero ventures away from home and into a strange land. Here, they encounter many obstacles and eventually find their way back, having returned with new insights and information. They will be changed in irrevocable ways.

We can look at the voyage and return plot with these stages:

- Anticipation—Your main character is going about their humdrum life. It’s not bad, it’s not good, it just is. Don’t worry—all that is about to change because life has other plans. They step though the back of a wardrobe, fall down a rabbit hole, or their house gets picked up and dropped somewhere else during a tornado (stop me if you’ve heard of these before).

- Dream—Wow, this place is cool. There are golden brick roads and animals that talk. There are donuts raining from the sky and you’re suddenly way bigger than everything else. But… something doesn’t feel quite right about this place.

- Frustration—That weird feeling you had? It’s starting to get worse. Something strange is happening and darkness is creeping in. You are definitely not in Kansas anymore.

- Nightmare—Whatever magic force or oppressive ruler or other tangled situation your hero has landed themselves in has just gotten a whole lot worse. How can they possibly get out of this with their head still attached to their body?

- Triumph—Whew. Your hero has found their way through the darkness and finds their way home, all the wiser and better for it.

Examples of stories with the Voyage and Return plot style include: Lord of the Rings (sometimes stories can feature more than one plot type), Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the Chronicles of Narnia, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz , and Goldilocks and the Three Bears .

The comedy plot archetype follows a protagonist with an air of light and humor and results in a happy ending. Book (again, we’re talking about the author, Christopher) maintained that this type was about more than just being funny, but rather relies on the idea that things become more and more confusing before a single event finally clears everything up at the end.

We can divide the comedy plot type into the following:

- Anticipation—Here we’re introduced to your happy-go-lucky character. Since a lot of romantic comedy plots fall into this type, we might also meet their potential love interest.

- Dream—Things are going all right. They’ve got some hilarious friends to help keep the mood light. But trouble is coming.

- Frustration—Something gets in the way for your character. Perhaps they’re separated from their potential love interest either physically or mentally. At any rate, this is the stage where confusion, miscommunication, and frustration make themselves known.

- Nightmare—Everything is going wrong. Confusion reigns, building that tension and making everyone more than a little miserable.

- Triumph—Confusion is cleared. Miscommunications are… communicated. They kiss and live happily ever after. The bad guy goes down. You name it. Whatever it is, everything is good.

Examples of stories that rely on the Comedy archetype include: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Much Ado About Nothing, Bridget Jones’s Diary, and Four Weddings and Funeral .

On the flip side of comedy is tragedy. In this plot type, your hero possesses a major character flaw that ultimately proves their undoing. This type evokes pity for the hero. Be warned: there are no happy endings here.

Let’s break the tragedy plot into these points:

- Anticipation—Your angst-ridden hero needs or wants something, be it fame, fortune, or good old fashioned lust. This is their ultimate motivation for everything that’s about to go down.

- Dream—Your hero has finally found a way towards their goal. Things seem to be looking up as they reach a point from which they can’t turn back. Deal with the devil anyone? Now they’re in this for better or worse.

- Frustration—My friends, it’s about to get worse. Right now we’ve got a few obstacles getting their way, nothing they can’t handle. But as they feel that dream slipping away, they start to do things to hang on to it. Things their mother might not approve of.

- Nightmare—And then it gets much worse. Your hero is at their lowest, perhaps the very worst version of themselves. They might get a little crazy. After all, the end is coming and they’re about to lose everything.

- Triumph—Okay, in this case, the ending isn’t so triumphant because the result is usually death, often through violence and while that’s not a happy ending, it’s certainly an ending. Sometimes life doesn’t prevail. At least we had fun while it lasted. Didn’t we?

Stories that use the Tragedy archetype are many, but include many of Shakespeare’s works like Macbeth, Othello, Hamlet, and King Lear .

This plot type has its roots in religion, but more generally speaking, it’s simply about a main character who undergoes a transformation to become a better person. Often it centers around a villainous character who is shown the light towards becoming a better version of themselves. We can break the rebirth plot down further like this:

- Anticipation—We meet our protagonist. They aren’t very likeable. In some cases, they’re kind of a boor. They might be cheap or lazy or steal young women and lock them in their castles. You know the type. We all know the type.

- Dream—Your “hero” is humming along being their bad self. No one can challenge their rightful place as a jerk. They are untouchable. Invincible. Wear a cool black cape. Until… oops, they aren’t. Something is coming to challenge them.

- Frustration—That challenge has arrived and is here to throw into question your hero and everything they thought they believed. Your hero is not a fan. They resist. They fight. And are not changing for anyone.

- Nightmare—Okay, so things are looking pretty bleak. Maybe being the bad guy isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. They’re left broken and alone and, for the first time in their life, they actually care about that.

- Triumph—Your hero has seen the light. They’ve been saved. They understand that they now want to be a better person. Hurray! Champagne for everyone.

Examples of stories that use the Rebirth archetype include: A Christmas Carol, Beauty and the Beast, The Secret Garden, Groundhog Day, or The Frog Prince .

Using Dabble and the seven basic plot points

Since the seven basic plots are as the name suggests… basic, it’s easy to use Dabble to structure your novel. Once you’ve settled on your plot type, break it down using the five points discussed above.

Unlike some other structure types, the basic plot points don’t prescribe where each point should happen in your story. Because of that, you might want to start by using Notes to outline the five points. You can be as detailed or high level as you want with this.

Once that’s done, you can start writing. As you progress through your chapters, you can assign each of the points to each chapter, depending on where they fall in the story. This way you can ensure you’re meeting them all before you get to the end.

Pros and cons of the seven basic plot points

As with any type of plotting structure, there are going to be pros and cons. And with any style, those pros and cons will largely depend on the writer.

The pros of the seven basic plot points are that it’s fairly broad—though whether this is a pro might depend on who you ask. Pantsers might love this style of plotting, as the five sections within each plot allow for a lot of freedom in how you build your tale. This style is less prescriptive than some other methods you’ll encounter.

Plotters, on the other hand, might find this style doesn’t give them enough structure or guidance. Some people want to be told on which page or at which percentage each beat should happen, and this method doesn’t offer that.

As with any list of this type, it's reductive to suggest there are only seven types of stories in the entire world. While these seven points do represent a broad range of storytelling in the western tradition, that doesn’t mean they are the only plots out there. Different cultures tell stories in different ways, and your story may not actually fit one of these. That doesn’t mean it’s wrong.

What this method offers is a good starting point, especially for new writers, to think about some of the world’s most well-known stories and what makes them work. If you’re struggling to develop your plot, this framework gives you some good hints about what kinds of obstacles, turning points and tropes can help drive your story forward.

Wanna try Dabble with one of the seven basic plot types? Try the premium features here for 14 days. It’s totally free with no credit card required.

Nisha J Tuli is a YA and adult fantasy and romance author who specializes in glitter-strewn settings and angst-filled kissing scenes. Give her a feisty heroine, a windswept castle, and a dash of true love and she’ll be lost in the pages forever. When Nisha isn’t writing, it’s probably because one of her two kids needs something (but she loves them anyway). After they’re finally asleep, she can be found curled up with her Kobo or knitting sweaters and scarves, perfect for surviving a Canadian winter.

SHARE THIS:

TAKE A BREAK FROM WRITING...

Read. learn. create..

A thorough proofreading is an absolutely crucial step in the writing process, whether you plan to self-publish or publish traditionally. Here's everything you need to know about getting the job done well... and when it might be time to hire a professional.

What is copy editing? How is it different from all the other bajillion types of editing? Do you need to hire an editor or can you do it yourself? Find all those answers and more right here.

Eyeballing Squibler but still curious about the other writing programs out there? Here's everything you need to know about the top Squibler alternatives.

And the big paperback book

As writers, we've learned a lot. As publishers, we've seen a lot. As supporters of authors no matter what their publishing path, we want to share those experiences with you.

Wednesday, September 23, 2020

Plot archetypes: quests and voyage and return, let's keep in touch, no comments:, post a comment.

- Hand-Illustrated Explainer Videos

- Illustrated Conversation

- Infographics

- Strategy & Ideas

- Training Design & Development

- Event Communications

- Video Production

- Scripting & Script Assistance

- llustration

- Our Method: Scribology

- Our Process

- Our Guarantee

- What We Care About

- General Contact Info

- Book a Consult

- Book a Quote

- Schedule an Artist

How to Create a Script from 7 Major Storytelling Plots

Andrew Herkert

March 28th, 2019

Scriptwriting , Whiteboard Video

Storytelling for video marketing doesn’t have to be boring. We have learned that most stories fit into a basic plot line. Using these basic plots as starting points for your script can help create exciting, shareable content that connects with your audience.

Published in 2004, Christopher Booker’s “The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories” reportedly took him 34 years to write. A deep dive into the psychology behind how and why we tell stories, the book thoroughly details the seven different storytelling tropes, rooted in Jungian analysis. According to Booker, all the stories ever told can be divvied up across these seven categories:

1. Overcoming the Monster. 2. Rags to Riches. 3. The Quest. 4. Voyage and Return. 5. Comedy. 6. Tragedy. 7. Rebirth.

Is Booker right? It’s hard to say without knowing every story ever told since the dawn of time. While critical reactions to his theory were mixed, even a cursory examination of popular books, movies, and shows indicates that our natural instinct is to stick to a variation on one of these themes. Think about your favorite Oscar-nominated films- do they depend on one of the seven plots?

Let’s explore these archetypes and think about how we can use them when writing our video marketing content.

Overcoming the Monster

1. Overcoming the Monster

The first plot Christopher Booker covers in The Seven Basic Plots is Overcoming the Monster-perhaps the most basic plot of all, it’s also extremely effective. Familiar examples of this plot include Jurassic Park,Rocky, and Dracula. This plot features a hero/underdog up against an impossible evil, which can be either a figurative or literal monster. Booker lays it out in five stages, beginning with “Anticipation” (the hero beginning to understand the monster exists) and concluding with “Miraculous Escape” (the hero overcomes the monster with a combination of wit and bravery).

How can you write a video script using this plot?

Envision your topic as the“monster” you’re trying to defeat—maybe you’re grappling with organizational change or you need to roll out a new policy. Now think of yourself as the hero of your own video and plot out what happens between “Anticipation” and the “Miraculous Escape.”

After describing the monster in the Anticipation stage, write the “Dream” stage—where you encounter the monster and find yourself stronger than you ever dreamed you’d be. Next stage? “Frustration”—a conflict arises and you fail to overcome the monster. Just before the “Miraculous Escape,” you’ll have to navigate through the “Nightmare” stage, typically an epic battle where it seems all but inevitable that the monster will win. Yet you, the hero, will ultimately prevail.

This plot is perfect if you want your team to cheer you on or join with you to overcome your monster. It’s a timeless tale whether you’re talking about David and Goliath, or change management.

Rags to Riches

2. Rags to Riches

If hearing the term Rags to Riches prompts thoughts of glass slippers and midnight pumpkins, you’re not alone. Cinderella is by far the most common example of this basic plot. However, think outside the palace.

This plot serves to tell the story of anyone who has to work hard to overcome oppression or adversity, and is rewarded in the end. To apply this plot to a whiteboard video script, it’s key to think in metaphorical terms.

A Rags to Riches story begins with a protagonist in dire straits, and ends with them greatly enriched and empowered. There is usually an initial catalyst for change that drives the story towards its rewarding conclusion.

For the purposes of a video script, this plot is great for showing a journey from struggle to success. For example, maybe you’re selling an inexpensive, user-friendly home security software. You can describe the plight of someone who is dealing with the threat of theft, intrusion, and inconvenience. Then introduce your saves-the-day solution, and finally illustrate their newly empowered existence—all thanks to your software. Voila!

Your Rags to Riches story doesn’t have to be a fairy tale to end happily ever after.

3. The Quest

Star Wars. Homer’s Odyssey. The Princess Bride. Siddhartha. The Wizard of Oz. The Goonies. What do all of these stories have in common?

They’re all excellent examples of the third type of plot in Booker’s The Seven Basic Plots: The Quest.

Quest plots typically involve a hero or group of heroes who embark upon a journey propelled by some type of “holy grail” – whether it be true love, finding their way home, or bringing peace to the galaxy. Though they encounter obstacles and adversity along the way, and face tests of their character and strength, our heroes emerge victorious upon achieving their goal and finding their elusive holy grail.

How to apply this classic trope to your video script? The answer is simple, and if you’ve developed a marketing strategy, you’ve probably already thought of it.

Whatever you’re offering, whether it’s a service, a software, or a software as a service, write a script that shapes it into something highly valuable and sought after.

Describe the challenges your clients (the heroes of this script) might face as they travel towards your solution, and detail how, by the end of the quest, they’ll possess a powerful and mighty tool to combat future challenges.

This type of plot is all about building value into your topic, and knowing the pain points it can alleviate. So gather your value proposition, examine your clients’ needs, and be prepared for solution-seekers to journey your way. May the force be with you!

4. Voyage and Return

Voyage and Return

Ever fallen down a rabbit hole? Gotten into a hot tub and been transported back to high school? Stepped into a closet and wandered into a forest ruled by a mighty lion? These are plot points in famous examples of Booker’s fourth plot point, Voyage and Return (Alice in Wonderland, Hot Tub Time Machine, and The Chronicles of Narnia, respectively).

This type of plot is common in children’s tales as it leans heavily on allegory- fantastical events transpire as the protagonist travels (often magically) to a distant and different land, and returns a changed person, rich with experience and wiser about themselves and the world they actually inhabit, due to the lessons learned on their voyage.

This plot happens to be a perfect fit for a type of script we at TruScribe are quite familiar with- the metaphor.

It’s simple to write a video script in the voyage and return format if you can imagine a place, land, or even world designed solely to tell your story.

Talking wealth management? Maybe your hero topples into a bank vault, and wakes up surrounded by dollars come to life- there to take him on a trek through the dangerous Forest of Finance.

In HR? Perhaps your character falls asleep at their desk, only to dream of a magical office building where insults have come to life to teach him how to combat harassment. He returns a changed employee, ready to teach his colleagues. This type of plot is imaginative and powerfully memorable. Use it when you’re trying to communicate a broad or controversial topic that requires some finesse.

And if you find yourself sitting at a table with a bunch of talking animals, drinking tea and unsure of the way back to where you started (metaphorically speaking, of course) let us know- our scriptwriters would be happy to lend a hand.

Comedy as a plot isn’t about slipping on a banana peel or having a great punchline. It’s more about a series of confusing, awkward, or otherwise comical events within a lighthearted tale (often a romance) about people trying to triumph but having numerous laughable difficulties finding their way. Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing is a classic example of a comedy plot. As in many of the other basic plots, first the stage is set and the stakes are raised. In the comedy plot, next comes a period of confusion and/or isolation before the hero ultimately triumphs in the end. Think Bridget Jones’s Diary, Forgetting Sarah Marshall, Ocean’s Eleven, or Clerks.

The main thing to remember when trying to use comedy as your video plot is to keep it light hearted throughout. Try not to be gimmicky, but think of a fun way to showcase your product or service that will set up a couple obstacles between your audience and receiving it—obstacles that might be hilarious to watch someone overcome. People want to root for your main character, and a comedy always has a happy ending. So no matter what trials and tribulations you may throw into the story to introduce elements of confusion or isolation, be sure the ending results in a smile.

Booker’s sixth basic plot is likely the darkest out of all Seven Basic Plots. The Tragedy plot is, well, quite tragic, and the protagonist of this plot may be good, but they likely have nefarious characteristics—they may even be a full-fledged villain. Generally these traits emerge as a result of the first stage of the Tragedy plot, which surrounds temptations. The hero attempts to attain something forbidden or discouraged, which will lead the plot down a path of setbacks, a dramatic downward spiral, and finally the story comes to a sad conclusion, one which often includes tragic consequences for the hero. The most notorious example of this plot is Romeo and Juliet, but you might recognize the Tragedy plot in modern tales as well, like Goodfellas, Bonnie and Clyde, True Romance, and Breaking Bad.

You may not want to turn to the dark side in a whiteboard video, but if you can think of a fatal flaw that you’d like to expose, here’s a time where you can use your video script to illuminate a darker or very serious topic related to your goal.

For instance, if you are marketing an innovative treatment for a deadly disease, you can portray the disease itself as the protagonist of your tragedy. The mood tends to stay dark throughout a tragic video, and that often prompts deeper thought and contemplation—which can prompt your viewers to turn to your solution.

Much like spring, this plot is all about renewal, transformation, and new beginnings. The hero of a rebirth plot is often misguided, and changes for the better under the guidance of another, wiser character, or because they are inspired by love, family, or the greater good to become a better person. The rebirth plot is seen in The Lion King, The Grinch Who Stole Christmas, A Christmas Carol, Shawshank Redemption, Despicable Me, and The Secret Garden.

To rework this plot into a script, you’ll likely want to take the approach of the trusted guide. Explain the redeeming qualities that can transform your viewer’s world. Build trust through enumerating your solutions, and explain how they’ll lead your viewer away from a poor situation into a whole new world where they are freed from stress and can reinvent their business, their health, or themselves as a result. This plot provides a wonderful structure for illustrating change!

Now that you have a thorough understanding of the 7 Basic Plots, how will you tell your story?

And if you are looking for more guidance on writing your script, check out this post on Common Fears of Scriptwriting .

TruScribe visualizes words, ideas, and stories to change how people see, think, and act. If you have a project in mind or want to learn more, get in touch.

- Skip to navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

- Strategy Lay the foundation for strategic storytelling.

- Content Captivate your audiences and move them to action.

- Engagement Choose the best tools to create your stories.

- Evaluation Measure the effectiveness and impact of your work.

- Articles Explore how organizations are tackling storytelling challenges.

- Explore Explore how organizations are tackling storytelling challenges.

- What is Storytelling for Good?

The Voyage and Return: A Framework for Stories about Learning

An alternative story map for when obstacles are too great for the first pass.

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

- Email This Article

Also co-authored by Calvin Koon-Stack, Hattaway Communications.

The Social Impact Story Map used on Hatch for Good is based on a classical storytelling structure known as the Hero’s Journey. The Hero’s Journey is an archetype—a pattern so fundamental to the human experience that it describes successful stories across cultures, formats and time. From ancient mythology, to modern blockbuster cinema, the Hero’s Journey has remained central to human storytelling.

By definition, a Hero’s Journey is always a success story: it is a story where the protagonist goes out into the unknown, faces challenging obstacles, and overcomes them. But not every story is a success story. The social good sector must learn from failures, mistakes and miscalculations in order to make progress. And stories originating from these moments can be just as powerful and motivating as stories of triumph. Actors in the social good space want to hear that they are not alone in their struggles—and there is value in learning from one another.

When the obstacles are too great for the first pass, another model is needed. Enter “the Voyage and Return.”

Like the Hero’s Journey, the Voyage and Return is an archetype with a long tradition in storytelling. *The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe*, by C. S. Lewis, L. Frank Baum’s *The Wonderful Wizard of Oz*, the ancient Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, and the *Ramayana* all draw from this archetype, as do many others. What these stories have in common, despite their varying circumstances, is this: a protagonist who goes on a journey or a quest, and—regardless of success in their original goal—returns home with new knowledge. This knowledge is the crux of the Voyage and Return story.

The Voyage and Return model of storytelling is described by this general arc:

Just as in the Hero’s Journey, the protagonist ventures forth into the unknown, and at first, the world of the unknown is fascinating and exciting. The protagonist faces challenges, but is able to overcome them. But the longer the protagonist stays, the more difficult the experience becomes. Challenges turn to trials. The world becomes confusing, then frightening, and then—perhaps—threatening, before the protagonist is forced (or is able) to retreat back to the safety of home.

While this may seem demotivating at first, the real value of the Voyage and Return story comes at the end. Once the protagonist has returned to a place of safety, they are able to reflect on the experience. Though the protagonist may not have had success in their original endeavor, through reflection, they are able to think critically about what worked—and what didn’t—and to leverage those lessons learned to plan for the next attempt.

The Voyage and Return helps to communicate that there is value in failure. It provides a framework to share stories of learning. It says that it is okay to retreat from the unknown. It is okay to return home and not know immediately what are the next steps. But through reflection and contemplation, valuable lessons can be learned and shared.

Writing this kind of story requires taking a hard look at one’s experience. And then, the journey can start again: perhaps this time as the hero’s.

RELATED ON STORYTELLING FOR GOOD

- Content Toolkit

Related, on Storytelling for Good

Your ceo as master storyteller three types of stories leaders need to tell..

A Single Story Does Not Change the World Tell your audience stories that matter the most to them.

Bringing the Freedom to Marry for All to the National Level Making marriage equality a reality nationwide with storytelling campaigns.

What Are Archetypes and How Do I Use Them in Storytelling? Part II How to use different archetypes to appeal to your audience's aspirations

Make Video Part of Your Nonprofit Marketing Four strategies to enhance your video marketing.

The Science of Storytelling, Part 1: Help Your Audience Understand Cause and Effect Explore how stories help our brains process the complexity of the world around us.

Be the first to comment

- Terms of Service

- Supported By:

© 2024 The Communications Network . All Rights Reserved.

Types of stories: 7 story archetypes (and ways to use them)

Types of stories such as the seven story archetypes identified by Christopher Booker provide a starting point for writing something entirely your own

- Post author By Jordan

- 3 Comments on Types of stories: 7 story archetypes (and ways to use them)

Many types of stories recur across eras and cultures. Story archetypes such as ‘voyage and return’ are powerful in delivering drama, emotion, and satisfying change. Learn about the seven basic plots and ways to use familiar stories your own way:

What are story archetypes?

The word archetype refers to ‘an original that has been imitated’ ( Oxford ). For example, the archetype of ‘the fool’ in comedies. The wise-cracking jester (who often turns out to be the saddest person in the room) is an example of a character archetype .

Story archetypes: Form shaping content

Story archetypes are narrative forms without content that shape content choices.

For example, ‘the quest’ is an archetypal type of story. Each quest form is filled with its own content (events, characters, settings, surprises). The writer gives a quest story its own character (even if archetypal similarities to other quest stories remain).

Each story improvises on this archetypal material. The same way a jazz musician takes an old song, makes a new arrangement, and plays new melodies over old chords.

Archetypes and the work of Carl Jung

The term ‘archetype’ is also closely associated with the writings of Carl Jung.

Jung was a Swiss psychoanalyst and one of the major contributors to modern psychology.

Jung wrote extensively on the collective ideas and associations that are embedded in human thought and culture. He theorized about the stories we tell and the desires (conscious and unconscious) that drive them. He coined the term, collective unconscious, which refers to the unconscious mind and shared mental concepts.

Says Jung on archetypes:

There are as many archetypes as there are typical situations in life. Endless repetition has engraved these experiences into our psychic constitution, not in the form of images filled with content, but at first only as forms without content. Carl Jung, ‘The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious’, quoted by Academy of Ideas

What are the 7 main story types?

According to Christopher Booker’s book , The Seven Basic Plots: Why we tell stories (2004), the seven main types of story are:

- Overcoming the Monster . This is a story of a ‘terrifying, life-threatening, seemingly all-powerful monster who the hero must confront in a fight to the death’ (p. 22).

- Rags to Riches: A story of a ‘humble, disregarded little hero or heroine who is lifted out of the shadows to a glorious destiny’ (p. 53).

- The Quest: A story in which ‘a hero and his [ or her/their ] companions go through a succession of terrible, often near-fatal ordeals’. Often they receive ‘guidance from friendly helpers’ (p. 73).

- Voyage and Return : A story where an individual or group travels ‘out of their familiar, everyday, ‘normal’ surroundings into another world completely cut off from the first’ (p. 87).

- Comedy : Stories that (historically) revolved around confusions such as mistaken identities and precarious situations played for laughs, often involving a main character ‘who against all odds finally achieves the happy ending’ (p. 134).

- Tragedy : Stories that typically feature a protagonist ‘becoming more and more ensnared in their predicament’ (p. 176), often an ‘incomplete, egocentric figure who meets a lonely and violent end’ (p. 180) due to making the wrong choices.

- Rebirth : A story that ‘marks the move from one universal pole of existence to the other, from death to life’ (p. 205) in showing how a character moves from an imprisoned or trapped state to freedom and renewal.

Sharp-eyed critics might say that comedy and tragedy are not really plots. You could simplify the difference, as Booker does to an extent, to ‘comedy ends happily’ while ‘tragedy ends in misfortune’.

Nonetheless the story archetypes Booker discusses with examples in his 728-page study show that story archetypes do recur.

Societies have shared many spaces, religions, myths and conflicts, so it makes sense that there is plenty of overlap.

Develop your Story with a Mentor

Every quest needs an insightful mentor – find a writing guide.

Why story archetypes are helpful (plus their cons)

Story or common archetypes are helpful for your own writing process as they offer:

- Ideas and conceptual starting points for characters , narrative arcs and turning points

- Story structure around which to plan rising and falling action

- A means to recycle elements of popular myths and folktales that have proven great power to endure

The cons of using story archetypes in your planning or drafting process:

- Types may feel reductive or restrictive (if your story has the plot arcs of Cinderella but is set in space, critics might still describe it reductively as a ‘Cinderella story’).

- It’s easy to focus on what theories say a story typically does or should do rather than find a way that works for you that may buck trends and norms

How to use the seven story types to plot and find ideas

Story archetypes provide a tool to find ideas and develop characters . Ways to use them:

Use story archetypes to define limits

Use types as a story springboard, use plot types to plan important changes, find character archetypes within story types, borrow arcs to ensure payoffs, combine types to explore stories’ potential, subvert types of stories to make them your own.

Let’s explore these creative ways to use story patterns further:

Story archetypes are useful for establishing useful parameters.

Say you decide your story will be a ‘rags to riches’ story, for example.

This decision gives your story an inherent story arc : Someone will progress from relative poverty (whether spiritually or materially) to riches (real or metaphorical).

The very general form of the archetype gives a surprisingly large amount to work with.

You have a why and possibly who that arises from this. Why does your character’s fortune change? Who (or what) is responsible?

The second question is part of a major plot twist in Charles Dickens’ beloved classic Great Expectations , where the hero’s mysterious benefactor turns out not to be who the reader might assume it to be.

The rags to riches story type shows that simply having a dramatically different ‘before and after’ situation is all you need to build a story.

It is worth saying that story archetypes or the six basic story types, are often identified by critics after a work is written rather than a conscious part of the creative writing process. Yet thinking about them may help you give your story intentional shape .

Many story archetypes tend to go along with specific characters or character archetypes and even plot scenarios .

Take the first of Booker’s seven basic plot types: ‘Overcoming the Monster’. This is a staple of many a dystopian sci-fi or horror novel.

Booker writes of how we often encounter these types in the darker fairytales of childhood. Think ‘wolves who eat grannies and disguise themselves in their clothing’. Or cannibal witches with houses made of gingerbread.

Booker uses the Biblical story of David versus Goliath story arc as an example of an ‘Overcoming the Monster’ story where the monster is monstrous, but not necessarily tentacled or supernatural – merely gifted with extremely unfair-seeming advantage. The similarities between Goliath and a witch in a gingerbread house are:

- Being an almost unfairly powerful opponent or antagonist

- Working outside of the established norms or rules (a ‘fair’ opponent would be one’s own size, for example, unlike the giant Goliath, or would not have supernatural or magical powers if one did not)

These broad, general archetypal ideas supply a springboard for a story idea.

In a story of overcoming, how will your monster buck norms, break rules (think of how sirens and snakes tempt, lead astray).

What makes a monster dangerous, tempting, or both?

One thing a story archetype or form without content gives you is key moments of change .

In The Seven Basic Plots , Booker gives some examples of key moments in a typical quest story:

- The Call : An urgent compulsion to set out on an adventure and answer ‘the call’ or ‘the call to adventure’ (such as being saddled with a critical quest).

- Meeting with the hero’s companions: For example, how and where Frodo finds companions in his travels to Mordor to destroy the One Ring in The Lord of the Rings , or how Hazel in Watership Down , the leader of a fluffle (that’s the actual word) of rabbits, is accompanied by other rabbits with individual strengths.

- The journey: The portion of the quest during which characters go through ‘terrible, often near-fatal ordeals’ (Booker, p. 73).

- Temptations: The hero may be tempted while pursuing their quest to stray off course (Arthurian knights are tempted by crones disguised as beautiful women, for example, or Odysseus is tempted to leap overboard while at sea by the sirens’ song in Homer’s Odyssey ).

- Meeting helpers: Heroes in quests often encounter helpers who give them special and crucial aid. For example, in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe , the Pevensie children meet a talking faun and beavers who help them understand the land of Narnia and its dangers.