What is business tourism and why is it so big?

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

In 2017, the world travel and tourism industry contributed more than $10 trillion dollars to the global economy. Of this amount, business tourism contributed a significant proportion, with a total of $1.23 trillion dollars.

Modern society transportation and infrastructure systems continue to revolutionise and therefore business tourism has the means to provide greater economic power than it has previously.

In this post, I will focus on the growing tourism industry of ‘business tourism’. I will explain what business tourism is, why business tourism is part of the tourism industry and provide a few examples of where business tourism takes place.

What is business tourism?

Definitions of business tourism, why is business tourism important, international exhibitors, corporate hospitality events, conferences, leisure time activities, benefits of business tourism, top business tourism destinations, business tourism in hong kong, business tourism in london, business tourism in new york, business tourism in toronto, business tourism in san francisco, business tourism: a conclusion, further reading.

Business tourism, or business travel, is essentially a form of travel which involves undertaking business activities that are based away from home.

The United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) defines tourists as people ‘traveling to and staying in places outside their usual environment for not more than one consecutive year for leisure, business and other purposes’, thus making business an important and integral sector of the tourism economy.

Business tourism activities includes attending meetings, congresses, exhibitions, incentive travel and corporate hospitality.

Academically, there isn’t a huge amount of literature on the characterisation of ‘business tourism’ or ‘business travel’. However, to quote from Davidson (1994) ‘Business tourism is concerned with people travelling for purposes which are related to their work.’

Business tourism represents one of the oldest forms of tourism, man having travelled for the purpose of travel since very early times” (cited in Bathia, 2006, p.272). To elaborate, business tourism is a means of travel that takes place for the primarily importance of a work-related activity.

Often the term ‘business tourism’ is described as ‘business traveller/travellers’.

There is a strong and correlative relation amongst a country’s economy and business tourism.

Business travellers are less cost sensitive on their expenditure as they themselves generally devote only a fraction of the cost. Research has shown that business travellers spend up to four times more during their trip than any other types of tourists . In fact, early research by Davidson and Cope , discovered that the ratio of daily expenditure by business travellers to that of leisure is generally situated somewhat between 2:1 and 3:1.

Therefore, business tourism provides significant economic contributions to the local and global economy. Business tourism also promotes the development for advanced infrastructure and transportation systems which also benefits other forms of tourism as well as the local population .

Business tourism also supports the hospitality industry, i.e. hotel bookings and restaurant bookings. This form of tourism also supports leisure tourism as business travellers tend to combine both activities together. This is referred as ‘bleisure tourism’, the combination of ‘business’ and ‘leisure’.

Business tourism activities

There are many forms of business tourism activities. Here I have demonstrated four key examples.

Business travellers may travel for the purpose of attending an exhibition. Exhibitions offer opportunities for businesses to connect with the international industry community. The exhibition industry entices two groups of people: those with something to sell and those who attend with a view to making a purchase of getting information.

Exhibitions come in all shapes and sizes depending on a person’s area of interest or work. As I have an interest in tourism I have attended a number of relevant travel exhibitions in recent years including ITB in Berlin and The World Travel Market in the UK.

Throughout many business excursions, the business traveller will have some form of meeting to attend during the course of their trip. Meetings may be appointments with clients; a board meeting at the present company or interstate of international branches; or an orientation meeting with staff at a new branch. Meetings can take place face-to-face or electronically using means such as Skype or FaceTime.

Corporate hospitality is a form of business travel that takes place when a corporation invites their guests to attend an event or an organised activity at no extra charge.

Corporate hospitality is a valuable tool used by corporations to foster relations, both internal and external to the company or to brand in influential circles. The extent to which corporate hospitality can yield tangible and intangible benefits is covered really well in the bestselling business book from award-winning restauranteur Danny Meyer, of Union Square Cafe, Gramercy Tavern, and Shake Shack entitled Setting the Table: The Transforming Power of Hospitality in Business .

A conference is a formal meeting of people with a shared interest. Conferences may last a day or they may last several days.

Conferences are common across a number of industries. Having worked in academia for a number of years, I have attended and presented at many conferences such as the ICOT conference in Thailand in 2017 and the International Conference on Sustainable Tourism in Nepal in 2018. I even won the three minute thesis competition at a PhD conference that I attended at the University of Staffordshire!

There are also many conferences and get togethers for travel bloggers that I am interested, such as TBEX , Traverse and Travel Massive .

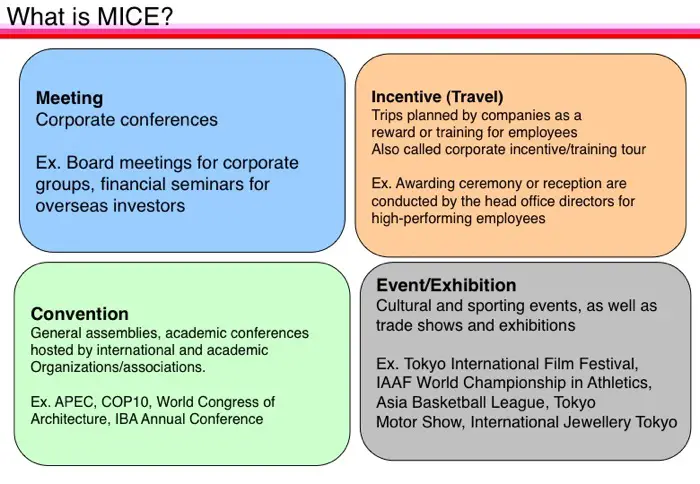

Often in the business tourism literature you will come across the term MICE. MICE is a reference for Meetings, Incentives, Conferences and Events. The term MICE has been recognised as ‘The Meeting Industry’ according to the United Nations World Tourism Organisation .

The MICE industry contributes significantly to the wider business tourism sector. It is becoming increasingly recognised as a prominent part of the industry and is beginning to receive growing attention amongst the academic community. You can read a detailed article about MICE tourism here.

Along with the examples demonstrated above, business travellers also participate in leisure activities outside of their business commitments. These activities could range from dining out, sightseeing and other recreational activities. When I attended a conference in Nepal in 2017, for example, I took my mother in law and daughter along for the conference gala dinner where we took part in traditional Nepalese evening celebrations!

There are many benefits of business tourism. Notably, it brings economic value to the wider tourism industry as well as the local economy, for example through hotel bookings or sales of business travel backpacks . What many people forget to mention, however, are the benefits that business tourism can also have for the tourist!

I have travelled many times for business, whether this as part of my former Cabin Crew career, for an academic conference or to undertake consultancy work. Travelling frequently for work can yield many benefits for the individual, such as;

- Collecting frequent flier miles and redeeming these for personal use

- Becoming a member of hotel loyalty programmes and receiving associated benefits during both work and personal trips

- Saving money on things such as food and drink when attending corporate hospitality events

- Enhanced networking opportunities that may otherwise be inaccessible

- Taking advantage of leisure opportunities that may be otherwise inaccessible

- Enjoying the use of facilities, such as gyms or swimming pools, that may not otherwise be available to you

Business tourism destinations

There are a variety of business tourism destinations all across the world. However, this type of tourism is predominantly situated in global north countries. This is mainly because global north countries are developed countries and have the means to provide well equipped resources and infrastructure to makes business tourism easily accessible and thus desirable choices among business travellers.

According to Egencia , the corporate travel group collected data from flight booking and reservations during the years 2014 and 2018. Their collection of data led them to discover the top 20 destinations for global business tourism.

Following the list above, I have listed a set of examples of business tourism that are listed within the top ten destinations for global business tourism/travel.

Hong Kong ranks 8 th in the world for global business tourism and has been deemed one of Asia’s top choice for business travel. According to CTM , Central and Tsim Sha Tsui are the most popular commercial areas for business travel, with several hotels and business headquarters.

Hong Kong is the perfect destination for MICE (meetings, incentives, conferences and events) and in 2014, this form of tourism accounted for 1.82 million visitors.

There are around 283 hotels in Hong Kong.

There are a variety of things to do in Hong Kong during a business trip of the traveller is wanting to blend business and leisure together. A list of things to do are:

- Victoria Peak

- Tian Tan Buddha

- Victoria Harbour The Peak Tram

London ranks 2 nd in the world for global business tourism. London is the financial capital of the world and with this status comes several high-profile companies and is thought to be one of the best places to network and seek new business opportunities. This is why so many business tourists visit London for conferences, meetings and exhibitions.

London has around 1500 hotels.

There are a variety of things to do in London during a business trip of the traveller is wanting to blend business and leisure together. A list of things to do are:

- Buckingham Palace

- Coco Cola London Eye

- The British Museum

- Palace of Westminster

In 2019, New York was named the world’s top destination for business tourism for the fourth consecutive year. At no surprise when business travel flight bookings increased by more than 120% between 2014 and 2018.

New York is also a popular destination for business tourism as it offers a great deal of leisure activities and promotes the idea of blending business with leisure travel.

There are a variety of things to do in New York during a business trip of the traveller is wanting to blend business and leisure together. A list of things to do are:

- Statue of Liberty National Monument

- Central Park

- Empire State Building

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Toronto has been ranked the 5 th destination for global business tourism, outranking major commercial centres in the U.S.

Toronto (pronounced as “Traw-no” by the locals), is the financial capital of Canada. And according to Business Events, Toronto is the top Canadian domestic travel destination and the most popular choice for U.S sponsored association meetings outside the U.S.

In Toronto there are over 170 hotels which collectively has around 36,000 hotel rooms.

There are a variety of things to do in Toronto during a business trip of the traveller is wanting to blend business and leisure together. A list of things to do are:

- Royal Ontario Museum Art Gallery of Ontario

San Francisco has been ranked 7 th in the world for global business tourism. According to The San Francisco Travel Association , San Francisco welcomed 18.9 million leisure visitors and 5.8 million business travellers in 2015.

According to Joe D’Alessandro, president and CEO of San Francisco Travel, San Francisco is “experiencing sustained growth in all market segments – domestic, international, leisure and business – as a result of our highly professional and sophisticated community of hotels, restaurants, cultural organizations and SFO, one of the finest airports in the world.”

There are a variety of things to do in San Francisco during a business trip of the traveller is wanting to blend business and leisure together. A list of things to do are:

- Fisherman’s Wharf

- Golden Gate Bridge

- Golden Gate Park

Where business exists, the demand for business travel follows. Business tourism is predominantly located where good transportation systems are allocated, i.e. airports, taxis, railways. The choices of hotels and restaurants also attracts business travel.

Do you travel for business? What things do you look out for on your business trip? Are you a lover of combining business and leisure activities? Leave a comment below.

Like this post? For more on different types of tourism, I’d suggest reading my tourism glossary !

- Setting the Table: The Transforming Power of Hospitality in Business – The bestselling business book from award-winning restauranteur Danny Meyer, of Union Square Cafe, Gramercy Tavern, and Shake Shack

- Event Planning: The Ultimate Guide To Successful Meetings, Corporate Events, Fundraising Galas, Conferences, Conventions, Incentives and Other Special Events – An academic text focussing on MICE in the events industry

- The Business of Tourism – A introductory text to the tourism industry

Liked this article? Click to share!

The future of tourism: Bridging the labor gap, enhancing customer experience

As travel resumes and builds momentum, it’s becoming clear that tourism is resilient—there is an enduring desire to travel. Against all odds, international tourism rebounded in 2022: visitor numbers to Europe and the Middle East climbed to around 80 percent of 2019 levels, and the Americas recovered about 65 percent of prepandemic visitors 1 “Tourism set to return to pre-pandemic levels in some regions in 2023,” United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), January 17, 2023. —a number made more significant because it was reached without travelers from China, which had the world’s largest outbound travel market before the pandemic. 2 “ Outlook for China tourism 2023: Light at the end of the tunnel ,” McKinsey, May 9, 2023.

Recovery and growth are likely to continue. According to estimates from the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) for 2023, international tourist arrivals could reach 80 to 95 percent of prepandemic levels depending on the extent of the economic slowdown, travel recovery in Asia–Pacific, and geopolitical tensions, among other factors. 3 “Tourism set to return to pre-pandemic levels in some regions in 2023,” United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), January 17, 2023. Similarly, the World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC) forecasts that by the end of 2023, nearly half of the 185 countries in which the organization conducts research will have either recovered to prepandemic levels or be within 95 percent of full recovery. 4 “Global travel and tourism catapults into 2023 says WTTC,” World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC), April 26, 2023.

Longer-term forecasts also point to optimism for the decade ahead. Travel and tourism GDP is predicted to grow, on average, at 5.8 percent a year between 2022 and 2032, outpacing the growth of the overall economy at an expected 2.7 percent a year. 5 Travel & Tourism economic impact 2022 , WTTC, August 2022.

So, is it all systems go for travel and tourism? Not really. The industry continues to face a prolonged and widespread labor shortage. After losing 62 million travel and tourism jobs in 2020, labor supply and demand remain out of balance. 6 “WTTC research reveals Travel & Tourism’s slow recovery is hitting jobs and growth worldwide,” World Travel & Tourism Council, October 6, 2021. Today, in the European Union, 11 percent of tourism jobs are likely to go unfilled; in the United States, that figure is 7 percent. 7 Travel & Tourism economic impact 2022 : Staff shortages, WTTC, August 2022.

There has been an exodus of tourism staff, particularly from customer-facing roles, to other sectors, and there is no sign that the industry will be able to bring all these people back. 8 Travel & Tourism economic impact 2022 : Staff shortages, WTTC, August 2022. Hotels, restaurants, cruises, airports, and airlines face staff shortages that can translate into operational, reputational, and financial difficulties. If unaddressed, these shortages may constrain the industry’s growth trajectory.

The current labor shortage may have its roots in factors related to the nature of work in the industry. Chronic workplace challenges, coupled with the effects of COVID-19, have culminated in an industry struggling to rebuild its workforce. Generally, tourism-related jobs are largely informal, partly due to high seasonality and weak regulation. And conditions such as excessively long working hours, low wages, a high turnover rate, and a lack of social protection tend to be most pronounced in an informal economy. Additionally, shift work, night work, and temporary or part-time employment are common in tourism.

The industry may need to revisit some fundamentals to build a far more sustainable future: either make the industry more attractive to talent (and put conditions in place to retain staff for longer periods) or improve products, services, and processes so that they complement existing staffing needs or solve existing pain points.

One solution could be to build a workforce with the mix of digital and interpersonal skills needed to keep up with travelers’ fast-changing requirements. The industry could make the most of available technology to provide customers with a digitally enhanced experience, resolve staff shortages, and improve working conditions.

Would you like to learn more about our Travel, Logistics & Infrastructure Practice ?

Complementing concierges with chatbots.

The pace of technological change has redefined customer expectations. Technology-driven services are often at customers’ fingertips, with no queues or waiting times. By contrast, the airport and airline disruption widely reported in the press over the summer of 2022 points to customers not receiving this same level of digital innovation when traveling.

Imagine the following travel experience: it’s 2035 and you start your long-awaited honeymoon to a tropical island. A virtual tour operator and a destination travel specialist booked your trip for you; you connected via videoconference to make your plans. Your itinerary was chosen with the support of generative AI , which analyzed your preferences, recommended personalized travel packages, and made real-time adjustments based on your feedback.

Before leaving home, you check in online and QR code your luggage. You travel to the airport by self-driving cab. After dropping off your luggage at the self-service counter, you pass through security and the biometric check. You access the premier lounge with the QR code on the airline’s loyalty card and help yourself to a glass of wine and a sandwich. After your flight, a prebooked, self-driving cab takes you to the resort. No need to check in—that was completed online ahead of time (including picking your room and making sure that the hotel’s virtual concierge arranged for red roses and a bottle of champagne to be delivered).

While your luggage is brought to the room by a baggage robot, your personal digital concierge presents the honeymoon itinerary with all the requested bookings. For the romantic dinner on the first night, you order your food via the restaurant app on the table and settle the bill likewise. So far, you’ve had very little human interaction. But at dinner, the sommelier chats with you in person about the wine. The next day, your sightseeing is made easier by the hotel app and digital guide—and you don’t get lost! With the aid of holographic technology, the virtual tour guide brings historical figures to life and takes your sightseeing experience to a whole new level. Then, as arranged, a local citizen meets you and takes you to their home to enjoy a local family dinner. The trip is seamless, there are no holdups or snags.

This scenario features less human interaction than a traditional trip—but it flows smoothly due to the underlying technology. The human interactions that do take place are authentic, meaningful, and add a special touch to the experience. This may be a far-fetched example, but the essence of the scenario is clear: use technology to ease typical travel pain points such as queues, misunderstandings, or misinformation, and elevate the quality of human interaction.

Travel with less human interaction may be considered a disruptive idea, as many travelers rely on and enjoy the human connection, the “service with a smile.” This will always be the case, but perhaps the time is right to think about bringing a digital experience into the mix. The industry may not need to depend exclusively on human beings to serve its customers. Perhaps the future of travel is physical, but digitally enhanced (and with a smile!).

Digital solutions are on the rise and can help bridge the labor gap

Digital innovation is improving customer experience across multiple industries. Car-sharing apps have overcome service-counter waiting times and endless paperwork that travelers traditionally had to cope with when renting a car. The same applies to time-consuming hotel check-in, check-out, and payment processes that can annoy weary customers. These pain points can be removed. For instance, in China, the Huazhu Hotels Group installed self-check-in kiosks that enable guests to check in or out in under 30 seconds. 9 “Huazhu Group targets lifestyle market opportunities,” ChinaTravelNews, May 27, 2021.

Technology meets hospitality

In 2019, Alibaba opened its FlyZoo Hotel in Huangzhou, described as a “290-room ultra-modern boutique, where technology meets hospitality.” 1 “Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba has a hotel run almost entirely by robots that can serve food and fetch toiletries—take a look inside,” Business Insider, October 21, 2019; “FlyZoo Hotel: The hotel of the future or just more technology hype?,” Hotel Technology News, March 2019. The hotel was the first of its kind that instead of relying on traditional check-in and key card processes, allowed guests to manage reservations and make payments entirely from a mobile app, to check-in using self-service kiosks, and enter their rooms using facial-recognition technology.

The hotel is run almost entirely by robots that serve food and fetch toiletries and other sundries as needed. Each guest room has a voice-activated smart assistant to help guests with a variety of tasks, from adjusting the temperature, lights, curtains, and the TV to playing music and answering simple questions about the hotel and surroundings.

The hotel was developed by the company’s online travel platform, Fliggy, in tandem with Alibaba’s AI Labs and Alibaba Cloud technology with the goal of “leveraging cutting-edge tech to help transform the hospitality industry, one that keeps the sector current with the digital era we’re living in,” according to the company.

Adoption of some digitally enhanced services was accelerated during the pandemic in the quest for safer, contactless solutions. During the Winter Olympics in Beijing, a restaurant designed to keep physical contact to a minimum used a track system on the ceiling to deliver meals directly from the kitchen to the table. 10 “This Beijing Winter Games restaurant uses ceiling-based tracks,” Trendhunter, January 26, 2022. Customers around the world have become familiar with restaurants using apps to display menus, take orders, and accept payment, as well as hotels using robots to deliver luggage and room service (see sidebar “Technology meets hospitality”). Similarly, theme parks, cinemas, stadiums, and concert halls are deploying digital solutions such as facial recognition to optimize entrance control. Shanghai Disneyland, for example, offers annual pass holders the option to choose facial recognition to facilitate park entry. 11 “Facial recognition park entry,” Shanghai Disney Resort website.

Automation and digitization can also free up staff from attending to repetitive functions that could be handled more efficiently via an app and instead reserve the human touch for roles where staff can add the most value. For instance, technology can help customer-facing staff to provide a more personalized service. By accessing data analytics, frontline staff can have guests’ details and preferences at their fingertips. A trainee can become an experienced concierge in a short time, with the help of technology.

Apps and in-room tech: Unused market potential

According to Skift Research calculations, total revenue generated by guest apps and in-room technology in 2019 was approximately $293 million, including proprietary apps by hotel brands as well as third-party vendors. 1 “Hotel tech benchmark: Guest-facing technology 2022,” Skift Research, November 2022. The relatively low market penetration rate of this kind of tech points to around $2.4 billion in untapped revenue potential (exhibit).

Even though guest-facing technology is available—the kind that can facilitate contactless interactions and offer travelers convenience and personalized service—the industry is only beginning to explore its potential. A report by Skift Research shows that the hotel industry, in particular, has not tapped into tech’s potential. Only 11 percent of hotels and 25 percent of hotel rooms worldwide are supported by a hotel app or use in-room technology, and only 3 percent of hotels offer keyless entry. 12 “Hotel tech benchmark: Guest-facing technology 2022,” Skift Research, November 2022. Of the five types of technology examined (guest apps and in-room tech; virtual concierge; guest messaging and chatbots; digital check-in and kiosks; and keyless entry), all have relatively low market-penetration rates (see sidebar “Apps and in-room tech: Unused market potential”).

While apps, digitization, and new technology may be the answer to offering better customer experience, there is also the possibility that tourism may face competition from technological advances, particularly virtual experiences. Museums, attractions, and historical sites can be made interactive and, in some cases, more lifelike, through AR/VR technology that can enhance the physical travel experience by reconstructing historical places or events.

Up until now, tourism, arguably, was one of a few sectors that could not easily be replaced by tech. It was not possible to replicate the physical experience of traveling to another place. With the emerging metaverse , this might change. Travelers could potentially enjoy an event or experience from their sofa without any logistical snags, and without the commitment to traveling to another country for any length of time. For example, Google offers virtual tours of the Pyramids of Meroë in Sudan via an immersive online experience available in a range of languages. 13 Mariam Khaled Dabboussi, “Step into the Meroë pyramids with Google,” Google, May 17, 2022. And a crypto banking group, The BCB Group, has created a metaverse city that includes representations of some of the most visited destinations in the world, such as the Great Wall of China and the Statue of Liberty. According to BCB, the total cost of flights, transfers, and entry for all these landmarks would come to $7,600—while a virtual trip would cost just over $2. 14 “What impact can the Metaverse have on the travel industry?,” Middle East Economy, July 29, 2022.

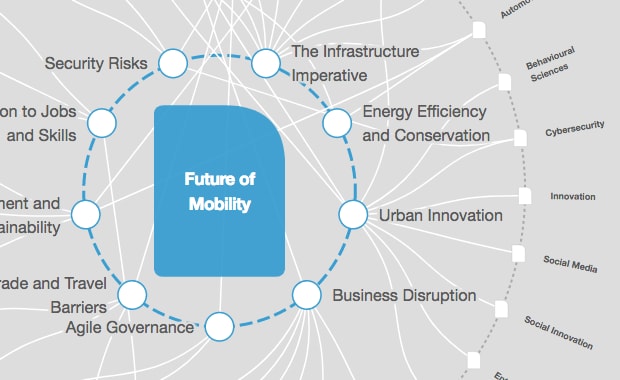

The metaverse holds potential for business travel, too—the meeting, incentives, conferences, and exhibitions (MICE) sector in particular. Participants could take part in activities in the same immersive space while connecting from anywhere, dramatically reducing travel, venue, catering, and other costs. 15 “ Tourism in the metaverse: Can travel go virtual? ,” McKinsey, May 4, 2023.

The allure and convenience of such digital experiences make offering seamless, customer-centric travel and tourism in the real world all the more pressing.

Three innovations to solve hotel staffing shortages

Is the future contactless.

Given the advances in technology, and the many digital innovations and applications that already exist, there is potential for businesses across the travel and tourism spectrum to cope with labor shortages while improving customer experience. Process automation and digitization can also add to process efficiency. Taken together, a combination of outsourcing, remote work, and digital solutions can help to retain existing staff and reduce dependency on roles that employers are struggling to fill (exhibit).

Depending on the customer service approach and direct contact need, we estimate that the travel and tourism industry would be able to cope with a structural labor shortage of around 10 to 15 percent in the long run by operating more flexibly and increasing digital and automated efficiency—while offering the remaining staff an improved total work package.

Outsourcing and remote work could also help resolve the labor shortage

While COVID-19 pushed organizations in a wide variety of sectors to embrace remote work, there are many hospitality roles that rely on direct physical services that cannot be performed remotely, such as laundry, cleaning, maintenance, and facility management. If faced with staff shortages, these roles could be outsourced to third-party professional service providers, and existing staff could be reskilled to take up new positions.

In McKinsey’s experience, the total service cost of this type of work in a typical hotel can make up 10 percent of total operating costs. Most often, these roles are not guest facing. A professional and digital-based solution might become an integrated part of a third-party service for hotels looking to outsource this type of work.

One of the lessons learned in the aftermath of COVID-19 is that many tourism employees moved to similar positions in other sectors because they were disillusioned by working conditions in the industry . Specialist multisector companies have been able to shuffle their staff away from tourism to other sectors that offer steady employment or more regular working hours compared with the long hours and seasonal nature of work in tourism.

The remaining travel and tourism staff may be looking for more flexibility or the option to work from home. This can be an effective solution for retaining employees. For example, a travel agent with specific destination expertise could work from home or be consulted on an needs basis.

In instances where remote work or outsourcing is not viable, there are other solutions that the hospitality industry can explore to improve operational effectiveness as well as employee satisfaction. A more agile staffing model can better match available labor with peaks and troughs in daily, or even hourly, demand. This could involve combining similar roles or cross-training staff so that they can switch roles. Redesigned roles could potentially improve employee satisfaction by empowering staff to explore new career paths within the hotel’s operations. Combined roles build skills across disciplines—for example, supporting a housekeeper to train and become proficient in other maintenance areas, or a front-desk associate to build managerial skills.

Where management or ownership is shared across properties, roles could be staffed to cover a network of sites, rather than individual hotels. By applying a combination of these approaches, hotels could reduce the number of staff hours needed to keep operations running at the same standard. 16 “ Three innovations to solve hotel staffing shortages ,” McKinsey, April 3, 2023.

Taken together, operational adjustments combined with greater use of technology could provide the tourism industry with a way of overcoming staffing challenges and giving customers the seamless digitally enhanced experiences they expect in other aspects of daily life.

In an industry facing a labor shortage, there are opportunities for tech innovations that can help travel and tourism businesses do more with less, while ensuring that remaining staff are engaged and motivated to stay in the industry. For travelers, this could mean fewer friendly faces, but more meaningful experiences and interactions.

Urs Binggeli is a senior expert in McKinsey’s Zurich office, Zi Chen is a capabilities and insights specialist in the Shanghai office, Steffen Köpke is a capabilities and insights expert in the Düsseldorf office, and Jackey Yu is a partner in the Hong Kong office.

Explore a career with us

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 05 November 2020

COVID-19 impact and survival strategy in business tourism market: the example of the UAE MICE industry

- Asad A. Aburumman 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 7 , Article number: 141 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

152k Accesses

52 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

Today the industry of meetings, incentives, conferences and exhibitions, commonly known under the name of MICE, contributes to economic diversification and actively stimulates the rational use of cultural-historical and natural recreational resources. As of 2019, the total contribution of the tourism sector to the GDP of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) equalled 11.5 per cent. More than 2.3 million visitors cited business as their main purpose of travel to Dubai in 2019, marking a two per cent increase compared to 2018. Thus, the UAE MICE industry was among the global leaders before the COVID-19 pandemic occurred. As a result of severe quarantine measures, the majority of destinations all over the world introduced COVID-19-related travel restrictions that were valid until May 2020. In the UAE, like in any other country, the coronavirus pandemic affected every industry, and especially the MICE one. Even though the consequences of COVID-19 have been multiply analysed by many UAE researchers, its global and local impact on the MICE industry, as well as the strategies for MICE companies’ survival, are described insufficiently. This study aimed to investigate the COVID-19 impact on both the global and the UAE MICE markets and identify a competitive survival strategy for tourism companies on the example of those operating in the UAE. The research revealed that under the conditions of harsh travel restrictions and closed borders, the UAE MICE industry is faced with a sharp reduction of demand. Emirati Airlines, hotels, and other tourism-related businesses have experienced significant material losses. In particular, the drop in scheduled departure flights comprised 82%. The multiplicative analysis performed in the course of the study identified the 5P marketing strategy and an outsourcing method as an optimal solution for MICE companies’ survival and recovery. The study results can be used by MICE businesses or researchers using specific company and market data for developing strategies aimed at overcoming COVID-related crisis and increasing the competitiveness of MICE companies in particular and the market as a whole.

Similar content being viewed by others

Improving microbial phylogeny with citizen science within a mass-market video game

The impact of Russia–Ukraine war on crude oil prices: an EMC framework

Infectious disease in an era of global change

Introduction.

The development of MICE industry (meetings, incentives, conferences and events) contributes to economic diversification, stimulates the rational use of cultural and natural-recreational resources, and enables a balanced growth of the whole tourism sector (Manzoor et al., 2019 ; Astakhova, 2019 ). For the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the tourism sector is especially important as a driver of national gross domestic product (GDP). As stated by the Dubai Annual Visitor Report 2019, at the end of 2019, tourism was responsible for contributing an impressive 11.5 per cent in GDP value. Furthermore, according to the World Travel and Tourism Council’s Cities Report, Dubai’s tourism sector was ranked one of ‘Top 10’ strongest economic share generators (Dubai’s Department of Tourism and Commerce Market, 2020 ).

More than 2.3 million visitors cited business as their main purpose of travel to Dubai in 2019, marking a two per cent increase compared to 2018 (Dubai Department of Tourism and Commerce Market, 2020 ). According to the Dubai Annual Visitor Report, in 2019, Dubai held 301 meetings, conferences and incentives organised by Dubai Business Events, thereby bidding for 595 events in 2020. In the year 2019, Dubai World Trade Center (DWTC) welcomed its record 3.57 million delegates, which declared the visitation growth of up to four per cent from the previous year. Such an increase was driven by 349 MICE and business events, 97 of which were large scale with over 2000 attendees. Since 2019, international participation in DWTC events grew by 15 per cent (equivalent to 1.2 million visitors), underlining the strong benefits the world businesses see in coming to Dubai with the aim of sharing knowledge, networking and accelerating their development (Dubai Department of Tourism and Commerce Market, 2020 ). Last year, the business tourism events accounted for 3.3% of GDP, which amounts to USD 3.57 billion (Dubai World Trade Centre, 2019 ). The business tourism was a key element in stimulating the national economic growth and in the nearest future was supposed to reach intense development, making the UAE among the central players in the global MICE industry (Rogerson, 2017 ; Dubai Tourism, 2020 ). However, the introduced quarantine ruined these plans.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to more than 4.3 million confirmed cases and more than 290.000 deaths worldwide. It raised fears of an impending economic crisis and recession. Social distancing, self-isolation, and travel restrictions have reduced the workforce in all sectors of the economy and have led to the loss of many jobs (Nicola et al., 2020 ; Tsindeliani, 2019 ).

Due to the lack of a vaccine and very limited treatment options, non-pharmaceutical interventions occurred to be the primary strategy to contain the pandemic. Unprecedented global travel restrictions and appeals to stay at home have caused the most critical disruptions of the global economy since World War II. Given the international travel bans that affect more than 90% of the global population and widespread restrictions on public gatherings and community mobility, tourism largely ceased in March 2020 (Gössling et al., 2020 ). Since the quarantine introduction, millions of jobs in the global tourism sector were lost due to flight, event and hotel cancellations (Siddiquei and Khan, 2020 ).

Given that international arrivals exceeded 1.5 billion for the first time only in 2019, the long-term evolution of tourism is proved to be greatly dependent on a decade of growth since the global financial crisis. Though, this last period of unhindered business tourism development has suddenly come to an end with the COVID-19 (Brouder, 2020 ).

Accompanied by quarantine in most countries and closed borders worldwide, COVID-19 pandemic heavily hit the MICE industry. The majority of domestic and international airlines were forced to cancel their flights due to severe quarantine measures and a lack of passengers, as people were frightened (Hoque et al., 2020 ).

The MICE industry was undermined by government efforts to contain and combat the pandemic. Borders were closed, trips banned, social and business events cancelled, and people were ordered to stay in their homes. By taking these actions, governments around the world sought to strike a balance between maintaining their economies and preventing dangerous levels of unemployment and deprivation. They tried to respond to public health imperatives to prevent the health systems’ collapse and mass deaths (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2020 ).

After months of unprecedented disruptions, the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) reported that the tourist sector begins to revive in some areas, especially in the Northern Hemisphere. At the same time, travel restrictions remained valid for most global destinations, and business tourism continued to be among the most affected sector of all (World Tourism Organization, 2020a ).

Although Dubai’s tourism sector announced reopening the city for international tourism on July 7, 2020, people worldwide were still afraid of travelling. Consequently, the numbers of international arrivals in Dubai were far from those before March 2020 (Dubai Tourism, 2020 ).

Today, as the COVID-19 pandemic continues and the second wave is forecasted by epidemiologists, political and business leaders are wondering if the recession in the markets and the economy truly signals a recession; how serious the COVID-19 recession will be; what will be the growth and recovery scenarios, and whether there will be any lasting structural impact from the unfolding crisis. However, all the forecasts and indices will not disclose the virus trajectory, the effectiveness of containment measures, and the reactions of consumers and companies. For now, there is no single figure that can reliably reflect or foresee COVID-19’s economic impact, especially on the MICE market dependent on international travel and public events (Carlsson-Szlezak et al., 2020 ). Even though the pandemic has been on the run for several months only, the global and market-related losses are huge. Nevertheless, now it is extremely difficult to assess them due to the lack of sufficient statistical data and unwillingness of some companies, industries and countries, especially the developing ones, to disclose the level of economic decline (Stock, 2020 ).

Despite the existence of numerous studies dedicated to COVID-19 and its estimated effect on economies and industries, poor attention was given to the global and local impact of coronavirus disease on the MICE industry and to strategies for MICE companies’ survival. The MICE industry of the UAE is chosen as a case study due to its leading position at the global MICE market before the pandemic-related crisis occurred.

The aim of the study is to investigate the global and local impact of COVID-19 on the MICE industry and identify a competitive survival strategy for MICE companies taking the UAE business sector as an example.

With the purpose of achieving the goals set, the following tasks were formulated:

Assess the effect of coronavirus pandemic on the global tourism market and MICE industry in the UAE;

Select indicators of economic efficiency to compute the profitability of MICE companies in the UAE;

Suggest a strategy for MICE business survival in the context of outsourcing in a globalised economy heavily influenced by COVID-19 (on the example of the UAE).

Literature review

Business trips and business tours are somewhat similar in terms of event tourism education (Holloway and Humphreys, 2019 ). The difference lies in the very essence of the event, but the mechanisms are generally the same. The fact that Abu Dhabi and Dubai are among the most important business centres of today increases the role of business tourism and its share in the country’s tour production (Zhamgaryan, 2017 ). Numerous conferences, business congresses, and diplomatic visits constitute the major drivers of business tourism (Sovet et al., 2016 ).

Literature on the use of tourism infrastructure and tourism management distinguishes the following principles that most countries rely upon:

Tourism and product topologies, territoriality research.

The presence of private and public travel companies and agencies.

Resources and recreational opportunities, tourist flows and service offers.

Independent choice of tourism agencies.

Communication with a client through outsourcing in business tourism creates an opportunity for world leaders in this industry to quickly grow and solve multiple problems, including the global ones caused by COVID-19 pandemic.

To survive, tourism agencies need to make efficient use of all reserves (Kuznetsov and Kizyan, 2017 ). Ensuring survival through competitiveness is a dynamic process aimed at long-term gain. The main goal of managing corporate competitiveness in the MICE industry is to create sustainable competitive advantages that can recover the position of MICE agencies and enable their financial performance in the post-pandemic environment (Nukusheva et al., 2020 ).

Existing studies on competitiveness in the tourism industry emphasise the importance of infrastructure and support services for environmental sustainability (Croes, 2010 ; Jovanović and Ilić, 2016 ; Kastenholz et al., 2012 ; Mihalicˇ, 2013 ; Reitsamer and Brunner‐Sperdin, 2017 ; Zehrer et al., 2016 ). Managing tourist behaviour also contributes to sector competitiveness (Reisinger et al., 2019 ). Previous researchers relied on a survey of tourism experts and key tourism stakeholders (Andrades and Dimanche, 2019 ). Some scholars made use of a mixed (quantitative-qualitative) method to measure competitiveness of a given industry in Iran (Boroomand et al., 2019 ). Others have developed their own industry competitiveness indices. For instance, some authors used data from the Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index produced by the World Economic Forum in a global analysis of industry competitiveness (Gómez-Vega and Picazo-Tadeo, 2019 ; Nazmfar et al., 2019 ), while others addressed alternative sources of information (Gu et al., 2019 ; Lopes et al., 2018 ).

Using structural equation modelling to the impact of tourism industry recovery and growth on environmental sustainability proves the presence of environmental degradation (Pulido-Fernández et al., 2019 ). The results of PROMETHEE and GAIA analysis from the competitiveness study of Portuguese tourist destinations revealed local competitors with their strengths and weaknesses. Among effective indicators are a sound tourism infrastructure and the potential of tourism destinations to grow through the adoption of public policies or private initiatives (Lopes et al., 2018 ).

The competitiveness of the MICE industry is considered with regard to subjective assumptions about competitiveness and significance of single indicators for sustainable development (Safarova, 2015 ). For example, Porter developed a universal model of micro-level competition. Poon’s framework for tourism competitiveness is built on innovative processes, quality, and privatisation. The WES model is a macroeconomic framework that takes into account tourism policies. In Dwyer’s model, the price component is recognised as a major component. The Crouch-Ritchie model integrates a whole range of tourism competitiveness factors, systematising global forces that pose challenges and open opportunities for tourism (Mazurek, 2014 ). The comparative study of Slovenia and Serbia tourism sectors using a modified IPA matrix identified the areas for improvement and actions for closing the gap between importance and performance of the MICE industry (these relate to the creation and adoption of innovative products) (Dwyer et al., 2016 ).

Materials and methods

With the purpose of analysing the impact of COVID-19 on global and the UAE MICE market, quantitative and qualitative analysis methods were used to evaluate the following data (in relative and absolute values):

World GDP growth rates for 2019, 2020 and 2021;

UAE GDP growth rates for 2019, 2020 and 2021;

International tourist arrivals for 2019 and 2020 (globally and by country);

Global international tourist arrivals from 2000 to 2020;

Global international tourist receipts from 2000 to 2020;

Employment loss in the travel, tourism and aviation industries in 2020;

Losses in travel, tourism and aviation industries in 2020;

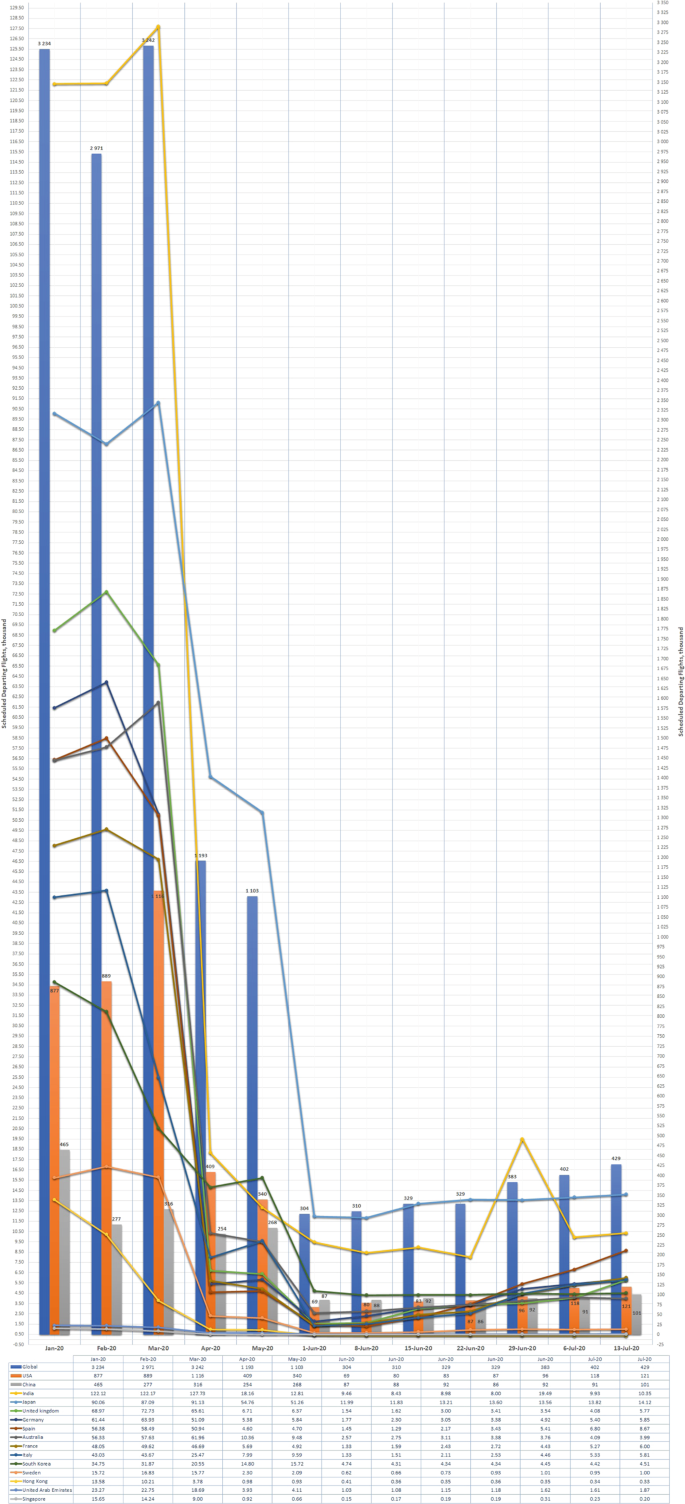

Scheduled departure flights in January–December 2019 and January–July 2020 (globally and by country).

The following sources were used to retrieve the above data:

Previous studies;

Reports of the World Bank;

Reports of the World Tourism Organization;

Reports of the World Travel and Tourism Council;

Reports of the OAG company;

Reports of Dubai Corporation of Tourism and Commerce Marketing;

Reports of Dubai Department of Tourism and Commerce Marketing;

Reports of Dubai World Trade Centre;

Statista Global Business Data Platform;

Official website of UAE-Consulting company;

Reports of the Oxford Analytica consulting firm.

The current analysis framework includes indicators that are interconnected to achieve a more accurate characterisation of the quality of decision-making. The DuPont System of Analysis is designed to compute the Return on Investment. This multiplicative model is frequently used by managers to assess the impact of quantity, price, and nomenclature on the revenue, as well as to analyse the structure of marginal profit, cost, and coefficient ratios (DuPont model, 2015 ). This study integrates the DuPont analysis model with the gross profit from the sale indicator to measure the profitability of MICE companies. The gross profit from the sale helps to assess the impact of the travel service cost on the company’s profitability, improving the overall result of economic analysis. The modified formula has the following form:

Where P MICE represents the MICE company’s profitability (in %);

NP represents the net profit from the sale, USD;

IS represents the income from the sale, USD;

GP represents the gross profit from the sale, USD;

NI represents the net income from the sale, USD.

The study applies a statistical method to collect data on the MICE industry competitiveness and behaviour of consumers (data to develop a forecast). With this method, managers can more efficiently make decisions on business recovery and competitiveness strategies. The dependence between the number of service offers and factors of the MICE industry is expressed via the production function model. This model is built around the number of people employed and the outsourcing strategy spending.

It should be noted that since no reliable data on the MICE industry recovery are available to date, some figures necessary for calculations were used from the pre-pandemic period. As soon as actual data are available, more accurate calculations can be made.

Results and discussion

Covid-19 impact on global and country tourism market.

According to the United Nations World Tourism Organization (World Tourism Organization, 2020 b), as of May 2020, 100% of destinations worldwide had travel restrictions associated with COVID-19. The pandemic has significantly impacted every sector of the travel and tourism industry: airlines, transportation, cruise lines, hotels, restaurants, attractions (such as national parks, protected areas and cultural heritage sites), travel agencies, tour operators and online travel organisations. Small and medium-sized enterprises and micro-firms, which include a large informal tourism sector, account for about 80 per cent of the tourism sector, and many of them may not survive the crisis without substantial support. This will lead to a domino effect in the entire tourism supply chain, affecting livelihoods in agriculture, fisheries, creative industries and other services. The loss of jobs in the MICE industry has a disproportionate effect on women, youth and the indigenous population. Women-owned and operated MICE companies are often smaller in size and have fewer financial resources to counter the crisis. Women hold such frontline positions in the tourism industry as housekeeping and front desk staff, which puts a particular risk to their health (Twining Ward and McComb, 2020 ).

According to the World Bank, the world GDP is expected to decline by 5.21% in 2020 (the decrease in 2019 comprised 2.38%) and grow by 4.16% in 2021. The dynamics of GDP of the United Arab Emirates will comprise −4.5% (compared to 1.7% growth in 2019), followed by the estimated increase by 1.4% in 2021 (World Bank, 2020 ).

In 2019, the direct, indirect and induced impact of travel and tourism industry accounted for 10.3% of the global GDP (USD 8.9 trillion) and 330 million jobs, or 1 in 10 jobs globally. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, in 2020, the global travel and tourism market is predicted to see a loss of 121 million jobs worldwide and USD 3,435 billion in global GDP (World Travel and Tourism Council, 2020 ).

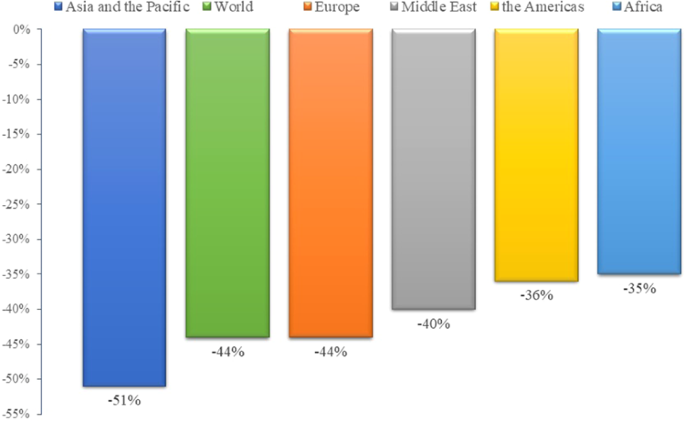

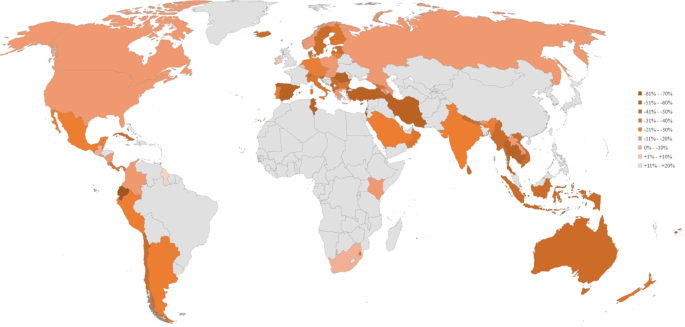

According to the data of the World Tourism Organization ( 2020a ), the United Nations agency taking charge of the promotion of responsible, sustainable and universally accessible tourism, as of June 22, 2020, the global fall in international tourist arrivals comprised 44% compared to 2019 (Fig. 1 ).

Source: developed by the authors based on data adapted from the World Tourism Organization ( 2020a ).

As shown in Fig. 1 , the most significant decrease in terms of international arrivals in January–April of 2020 experienced the Asia and the Pacific region (51%) followed by Europe (44%) and the Middle East (40%). The decline in international arrivals in the Americas and Africa equalled 36 and 35%, respectively (UNWTO, June 22, 2020).

In early May 2020, the UNWTO has outlined three possible scenarios for the MICE industry which indicate a potential decrease in the total number of international tourists from 58 to 78%, depending on when travel restrictions are lifted. Since mid-May, UNWTO has identified an increase in the number of destinations announcing measures to resume tourism. These include the introduction of enhanced safety and hygiene measures and policies aimed at developing domestic tourism (World Tourism Organization, 2020b ).

Geographically, the regions with the biggest relative drop in international tourist arrivals during January–April 2020 are Europe, Australia and New Zealand, and Western, Southern and Southeastern Asia (Fig. 2 ) Footnote 1 .

Source: developed by the authors based on data adapted from the World Tourism Organization ( 2020c ).

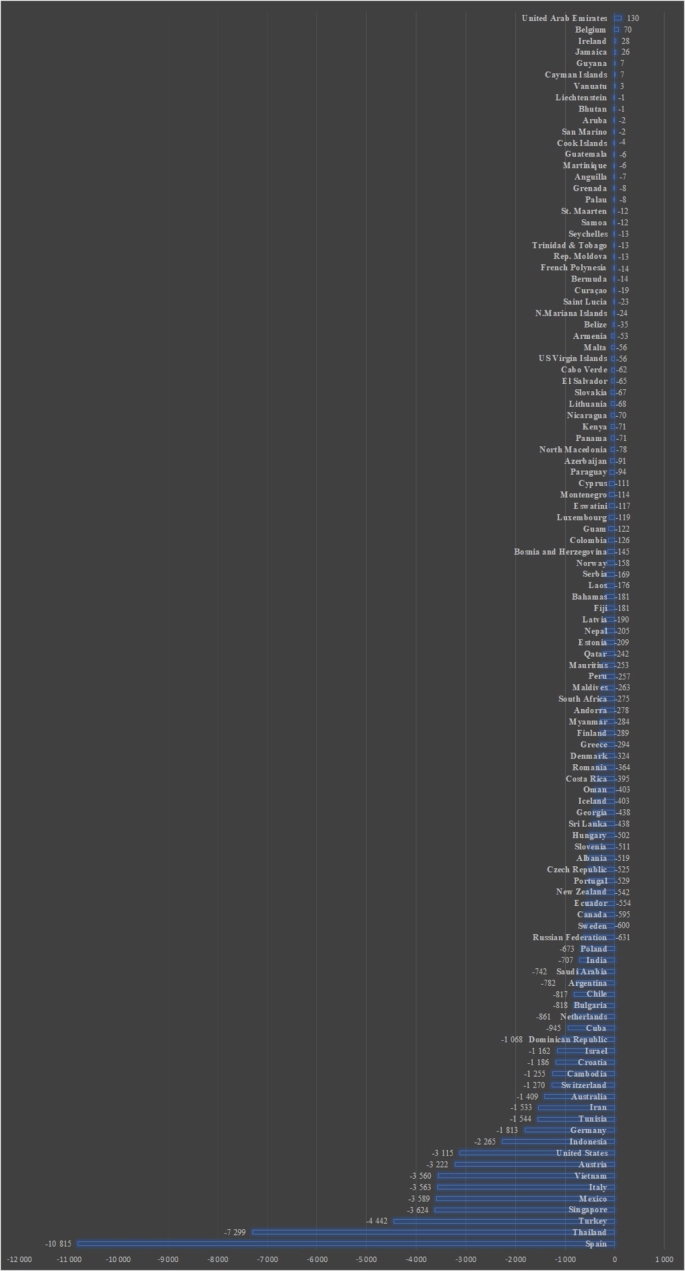

According to Fig. 3 , the largest absolute decrease in international tourist arrivals experienced Spain (10.8 million), followed by Thailand (7.3), Turkey (4.4), Singapore, Mexico, Italy, Vietnam (3.6 million each), Austria (3.2) and the United States (3.1) Footnote 2 Footnote 3 .

Despite several countries have positive values of international tourist arrivals (the United Arab Emirates, Belgium, Ireland, Jamaica, Guyana, Cayman Islands and Vanuatu), the data available in UNWTO report for them is for February 2020, when COVID-19-related travelling restrictions were not so severe. The same goes to a number of other countries with low decrease results (Aruba, Bhutan and Martinique).

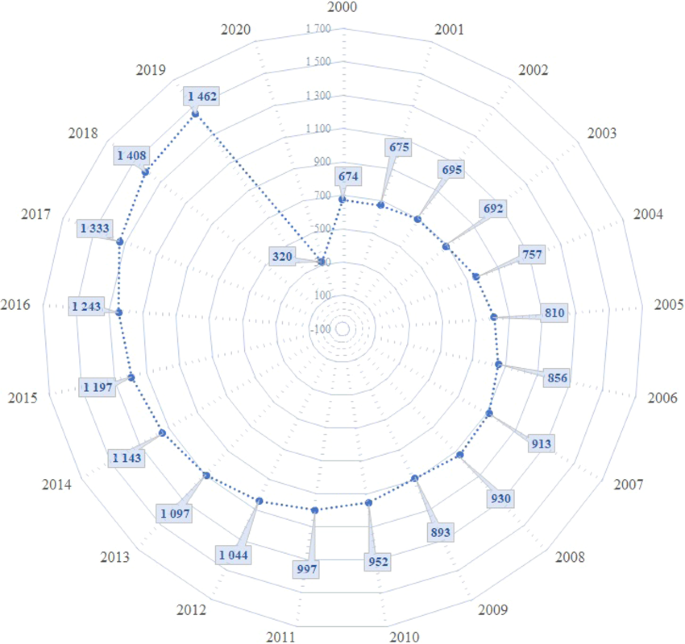

The international tourist arrivals worldwide showed stable growth in 2000–2019, except for some crisis years with a slight drop: 2003 (SARS pandemic, 3 million) and 2009 (global economic crisis, 37 million). According to the worst-case scenario of the UNWTO, the decrease in 2020 can reach 1.140 billion (Fig. 4 ).

Source: developed by the authors based on data adapted from the World Tourism Organization ( 2020b ).

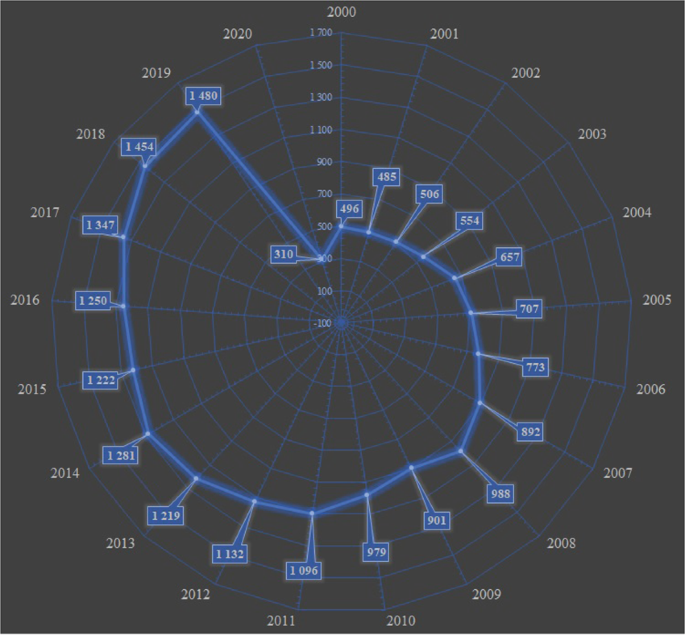

The global international tourism receipts also experienced constant growth in 2000–2019, with the exception of one year, 2009, when the drop was USD 88 billion (Fig. 5 ). In 2020 the decrease may reach USD 1.170 trillion as per the worst UNWTO scenario.

According to preliminary data, in the first quarter of 2020, the impact of aviation losses can reduce global GDP from 0.02 to 0.12%. Besides, if events develop according to the worst-case scenario, before the end of 2020, these aviation losses can be as high as 1.41–1.67%, with job losses about 25–30 million (Iacus et al., 2020 ).

Now, the UAE is at the forefront in terms of reducing demand for MICE services, as well as for global air travel. Emirati Airlines, hotels, and other travel and tourism-related businesses have experienced significant oversupply and must take decisive actions (Oxford Analytica, 2020 ). The Etihad Airways based in Abu Dhabi and Emirates Airline in Dubai have asked their employees to stay at home due to reduced number of flights thereby not excluding the possibility of layoffs (Siddiquei and Khan, 2020 ).

The global reduction of the scheduled departure flights comprised 2.8 million—from 3.234 million in January 2020 to 0.429 million on July 13, 2020. The anti-leaders in terms of the scheduled departure flights occurred to be the USA (−756 thousand flights), China (−363) and India (−112). For the same period, the UAE experienced a drop in 21 thousand flights, which is a comparatively small amount (Fig. 6 ).

Source: developed by the authors based on data adapted from OAG ( 2020 ).

As shown in Fig. 6 , starting from June, the situation with flights has begun to improve slightly. As to the UAE, the number of scheduled departure flights grew from 1.03 to 1.87 thousand weekly from June 1, 2020, to July 13, 2020.

In relative numbers, the deepest global fall of scheduled departure flights (compared to the same period of 2019) occurred in May 2020 and was 69% (Table 1 ). The countries with the biggest relative decrease were Singapore (97%, May), Spain (94%, April), Hong Kong (94%, April), Germany (93%, April), the United Kingdom (94%, June) and France (92%, May). The UAE had the most notable drop of 82% on June 1, 2020.

Today, more than 50 business events are scheduled for the fall of 2020 in Dubai, but they depend on the global and local epidemiological situation (Dubai Tourism, 2020 ).

Key performance indicators of the MICE industry

The computational results based on pre-pandemic data show that the long-term profitability of the MICE industry can be potentially stable and not influenced by investments in post-pandemic conditions. The rate of return on investment will decrease with a new tourism service. Competitiveness, however, has little relation to profitability ratio and hence is likely to increase.

The present findings are expected to facilitate marketing decision making. However, managers should decide on a strategy for competitiveness that will enable the reduction of MICE services cost, the increase of competitive services, and personnel training. An integrated multiplicative model of profitability that allows the assessment of the given strategy has the following form:

Where, N —cost of services provided, USD;

S —number of those employed in the MICE industry;

P —profit spent on outsourcing strategy development, USD;

i —number of new services.

The results prove the theoretical significance of the selected model (Fisher criterion is equal to 29.01; the coefficient of multiple determination amounts to 0.97; and the relative approximation error is 0.14). The correspondence between results is expressed using the criteria of truth and authenticity.

The elasticity of service provision corresponds to t 1 = 0.287 and t 2 = 0.128, assuming low efficiency. That is, with a per cent increase of profits or employees, the number of offers for MICE services can potentially grow either by 0.287 or by 0.128%, respectively. Consequently, personnel costs and working capital may have little impact on the competitiveness of the MICE industry in the UAE in post-pandemic conditions. These data were processed to develop three theoretical forecast scenarios for the sales of MICE services in post-pandemic conditions (Table 2 ).

The above forecasts based on pre-pandemic data suggest that MICE service sales can increase by 61.6% in 2020–2023. That is, the average annual number is predicted to increase by 25%, gaining USD 35 thousand in 2021. Hence, the economic growth model can serve as an effective tool for improving the tourism development strategy of travel agencies.

The calculations confirm that in pre-pandemic conditions (average tax about 39%; the minimum return 6.9%) when tourism companies used to spend 89% of their net earnings, the volume of tourism services could not be maintained and the gross value added was likely to drop by 3%. Therefore, to ensure better performance and a broader range of tourism services, the minimum rate of return in ideal conditions should be at least 12.9% and the grow value-added tax should not exceed 38.9%.

Strategy for MICE survival and competitiveness

A queuing model was proposed to optimise MICE companies in terms of performance in the post-pandemic market. The Kotler’s extended marketing mix model may serve as a framework of choice for hoteliers, providing a competitive advantage over the existing participants in the MICE market. This model allows evaluating MICE services from various segments of the market by the in-depth profitability and demand analyses.

The five Ps of the marketing mix model are:

Product—a hotel in which a business tourist stays and rests, where a business event is organised, etc.;

Price—pricing policy, discount, price-quality (varies depending on hotels and airlines, plus insurance, travel and event organisation), etc.;

Place—distribution channels, internet platforms, etc.;

Promotion—meetings, incentives, conventions, exhibitions (product launch), state summits, public relations and advertising, etc.;

People—loyal customers and VIP customers, staff, other customers, etc.

It can be argued that meetings and events in hotels that adhere to this marketing model will bring additional income to stakeholders and corporate business travel agencies and hence improve the image of MICE companies. The consequences of this 5P marketing mix model can also be the improvement of the tourism service quality.

Normally, large hotel corporations associate themselves with the image, rather than location. Therefore, when choosing strategies for gaining competitive advantage through outsourcing, the economic and marketing models were used. The underlying sustainable competitive advantages of MICE companies are innovation; service quality control; flexible, adaptive and strong organisational culture; intangible assets (image and business reputation); and consumer behaviour management. Hence, the competitiveness strategy should more focus on these variables. In cross-border tourism, the most promising strategies for competitiveness are those aimed at ensuring consumer loyalty, innovation and adaptation to the external environment like heightened health and safety measures. The MICE industry leaders are increasingly focused on current trends in outsourcing business processes, namely: expanding the boundaries of outsourcing; use of best practices, tools and technologies to ensure better management; the ability to integrate new features with existing systems; ensuring information confidentiality; the transition from individual services to service packages; and global coverage of existing and new markets.

Where there is the opportunity to survive in the pandemic and post-pandemic world and gain competitive advantages by reducing costs while increasing the efficiency of performance, business travel companies turn to outsourcing (It Pulse, 2019 ). Key Account Managers settle issues with the business travel organisation on the key client’s behalf (Suvorova, 2012 ). The main factors of competitiveness are the image and reliability of MICE companies. Competitiveness is achieved by improving the quality of services (Tymchyshyn-Chemerys and Pasternak, 2017 ). The previous studies highlighted the following important variables: total cost of business events; expenditures on restaurants and hotels, transportation, etc.; additional costs associated with increased demand; and value-added income.

The scientific novelty of this study is that it offers an optimal competitiveness strategy for the MICE industry offering to introduce outsourcing practices and the 5P marketing model.

Conclusions

The present research examined the impact of COVID-19 on global and UAE MICE market by way of quantitative and qualitative analysis. The study revealed that in the conditions of severe travel restrictions and closed borders, travel-dependant industries like MICE or passenger air services were significantly hit by the pandemic. In 2020, the COVID-19 quarantine measures are predicted to result in a global loss of 121 million jobs and USD 3,435 billion in GDP.

Now the UAE is at the forefront in terms of reducing demand for MICE services, as well as for global air travel. Emirati Airlines, hotels, and other travel and tourism-related businesses have experienced significant oversupply. Compared to the same period of 2019, the most considerable fall of scheduled departure flights in the UAE occurred on June 1, 2020, and equalled 82%. Despite the fact that the industry has started to recover after weakening anti-epidemic measures, this process can take some time (provided severe anti-pandemic measures will not be restored along with the new wave of COVID-2019).

The choice of survival and competitive strategy for the MICE industry is justified by the study of outsourcing business processes. Outsourcing enables the reduction of operating costs. In these circumstances, a MICE company needs to ‘keep the good work’ by employing competence, establishing a modern communication system, and promoting digitalisation.

The study used multiplicative analysis to evaluate the profitability of the MICE industry and the impact of operating costs on the competitiveness of MICE companies. The 5P marketing model was identified as an optimal choice for surviving and recovering MICE business companies through outsourcing. Since the major resource of organisations under consideration is people and the product, it is advisable to use the competitive marketing strategy when developing a management approach. However, because the product in the MICE industry is a result of multi-stage cooperation, the MICE service provider should simultaneously focus on the external environment.

The study findings can be used by travel agencies, MICE-related companies, or researchers, applying specific company and market data for developing strategies to overcome COVID-related crisis and increase the competitiveness of MICE business.

Due to the lack of reliable post-pandemic data, this research was limited to pre-pandemic information. As soon as actual data are available, more accurate calculations can be made, and theoretical research can be verified. Thus, there are enough opportunities for further research aimed at introducing the results obtained to certain post-pandemic MICE market conditions.

Data availability

Data used are available on request.

The aforementioned geographic regions correspond to the Standard Country or Area Codes for Statistics Use ( 1999 ) of the United Nations (M49 standard) .

The darker the colour in Fig. 1 is, the deeper is the decrease in international tourist arrivals.

There is no data on international arrivals for the markets of countries in grey in Fig. 1 .

Andrades L, Dimanche F (2019) Destination competitiveness in Russia: tourism professionals’ skills and competences. Int J Contemp Hospit Manag 31(2):910–930. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-11-2017-0769

Article Google Scholar

Astakhova LV (2019) The concept of student cognitive culture: definition and conditions for development. Educ Sci J 21(10):89–115. https://doi.org/10.17853/1994-5639-2019-10-89-115 . (In Russian)

Boroomand B, Kazemi A, Ranjbarian B (2019) Designing a model for competitiveness measurement of selected tourism destinations of Iran (the model and rankings). J Quality Assurance Hospit Tourism 20(4):491–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2018.1563015

Brouder P (2020) Reset redux: possible evolutionary pathways towards the transformation of tourism in a COVID-19 world. Tourism Geograph 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1760928

Carlsson-Szlezak P, Reeves M, Swartz P (2020) What coronavirus could mean for the global economy. Harvard Business Rev 3: 1–10

Croes R (2010) Measuring and explaining competitiveness in the context of small island destinations J Travel Res 50(4):431–442. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0047287510368139

Article ADS Google Scholar

Dubai Department of Tourism and Commerce Market (2020) Dubai Annual Visitor Report 2019. July, 2020. https://dubaitourism.getbynder.com/m/3e56c8625ed93ce0/original/DTCM-ANNUAL-REPORT-2019-EN.pdf . Last assessed: 17/07/2020

Dubai Tourism (2020) Dubai Corporation of Tourism and Commerce Marketing. http://www.visitdubai.com/en-us/department-of-tourism_new/about-dtcm/tourism-vision-2020

Dubai World Trade Centre (2019) DWTC drives record AED 13.1bn in net economic value and 3.3% impact to city’s GDP in 2018. Press Release. https://www.dwtc.com/en/press/dwtc-events-fuel-dubais-economy-2019

DuPont Model (2015) Calculation formula. 3 Modifications. Finance for Dummies (March 18, 2015). Date of treatment May 24, 2016

Dwyer L, Armenski T, Cvelbar LK, Dragićević V, Mihalic T (2016) Modified Importance–performance analysis for evaluating tourism businesses strategies: comparison of Slovenia and Serbia. Int J Tourism Res 18(4):327–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2052

Gómez-Vega M, Picazo-Tadeo AJ (2019) Ranking world tourist destinations with a composite indicator of competitiveness: to weigh or not to weigh? Tourism Manag 72:281–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.11.006

Gössling S, Scott D, Hall CM (2020) Pandemics, tourism and global change: a rapid assessment of COVID-19. J Sustain Tourism. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

Gu T, Ren P, Jin M, Wang H (2019) Tourism destination competitiveness evaluation in Sichuan province using TOPSIS model based on information entropy weights. Discrete Continuous Dynam Syst-S 12(4–5):771–782. https://doi.org/10.3934/dcdss.2019051

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Higgins-Desbiolles F (2020) Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after COVID-19. Tourism Geograph 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1757748

Holloway JC, Humphreys C (2019) The business of tourism. SAGE Publications Limited

Hoque A, Shikha FA, Hasanat MW, Arif I, Hamid ABA (2020) The effect of Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the tourism industry in China. Asian J Multidiscipl Stud 3(1):52–58

Google Scholar

Iacus SM, Natale F, Santamaria C, Spyratos S, Vespe M (2020) Estimating and projecting air passenger traffic during the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak and its socio-economic impact. Safety Sci 104791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104791

It Pulse (2019) What is outsourcing and what is it useful for business http://it-pulse.com.ua/chto-takoe-autsorsing-i-chem-on-polezen-dlya-biznesa.html

Jovanović S, Ilić I (2016) Infrastructure as important determinant of tourism development in the countries of Southeast Europe. Ecoforum 5(1):288–294

Kastenholz E, Eusebio C, Figueiredo E, Lima J (2012) Accessibility as competitive advantage of a tourism destination: the case of Lousã. In K Hyde, Ryan C, Woodside A (eds) Field guide to case study research in tourism, hospitality and leisure (Advances in Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research) (Vol. 6) Emerald Publishing Ltd, pp. 369–385

Kuznetsov YuV, Kizyan NG (2017) Features of the choice of competitiveness strategy at the enterprises of the tourism industry. Manag Consult 9(105):74–81. https://doi.org/10.22394/1726-1139-2017-9-74-81

Lopes APF, Muñoz MM, Alarcón-Urbistondo P (2018) Regional tourism competitiveness using the PROMETHEE approach. Ann Tourism Res 73:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.07.003

Manzoor F, Wei L, Asif M (2019) The contribution of sustainable tourism to economic growth and employment in Pakistan. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(19):3785. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193785

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mazurek M (2014) Competitiveness in tourism–models of tourism competitiveness and their applicability. Eur J Tourism Hospital Recreat 1:73–94

Mihalicˇ T (2013) Performance of environmental resources of a tourist destination: concept and application. J Travel Res 52(5):614–630. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513478505

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Nazmfar H, Eshghei A, Alavi S, Pourmoradian S (2019) Analysis of travel and tourism competitiveness index in middle-east countries. Asia Pacific J Tourism Res 24(6):501–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2019.1590428

Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, Agha M, Agha R (2020) The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): a review. Int J Surgery 78:185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018

Nukusheva A, Ilyassova G, Kudryavtseva L, Shayakhmetova Z, Jantassova A, Popova L (2020) Transnational corporations in private international law: do Kazakhstan and Russia have the potential to take the lead? Entrepre Sustain Issues 8(1):496–512

OAG. Flight Database & Statistics, Aviation Analytics (2020). Available at: www.oag.com . Last accessed: 16/07/2020

Oxford Analytica (2020) COVID-19 and oil shocks raise Gulf recession risks. Emerald Expert Briefings, (oxan-db)

Pulido-Fernández JI, Cárdenas-García PJ, Espinosa-Pulido JA (2019) Does environmental sustainability contribute to tourism growth? An analysis at the country level. J Cleaner Product 213:309–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.151

Reisinger Y, Michael N, Hayes JP (2019) Destination competitiveness from a tourist perspective: a case of the United Arab Emirates. Int J Tourism Res 21(2):259–279. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2259

Reitsamer B, Brunner‐Sperdin A (2017) Tourist destination perception and well‐being. J Vacation Market 23(1):55–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766715615914

Rogerson CM (2017) Tourism–a new economic driver for South Africa. In: Lemon A, Rogerson CM (eds) Geography and economy in South Africa and its neighbours. Routledge, pp. 95–110

Sable K, Roy A, Deshmukh R (2019) MICE Industry by Event Type (Meeting, Incentives, Conventions, and Exhibitions): Global Opportunity Analysis and Industry Forecast, 2018-2025. MICE Industry Outlook–2025. Allied Market Research. https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/MICE-industry-market

Safarova NN (2015) Analysis of national competitiveness of tourism and travel: conclusions for the CIS countries. Econ Analy 30(429):53–64

Siddiquei MI, Khan W (2020) Economic implications of coronavirus. J Public Affairs https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2169

Sovet K, Salima S, Altynay M (2016) Trends in the development of business tourism in the Republic of Kazakhstan. Probl Modern Sci Educ 40(82):1–9

Standard Country or Area Codes for Statistics Use (1999). The United Nations. Series: M, No. 49/Rev.4 (M49 standard). Online version. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/

Statista (2020) Global № 1 Business Data Platform. https://www.statista.com/statistics/734587/uae-domestic-expenditure-as-contribution-to-gdp/

Stock JH (2020) Reopening the Coronavirus-Closed Economy (Vol. 60). Technical Report. Hutchins Center Working Paper

Suvorova IN (2012) Corporate business tourism outsourcing. Russian Entrepre 12(210):161–166

Tsindeliani I (2019) Public financial law in digital economy. Informatologia 52(3–4):185–193

Twining Ward L, McComb JF (2020) COVID-19 and Tourism in South Asia: opportunities for sustainable regional outcomes. World Bank, Washington, DC

Book Google Scholar

Tymchyshyn-Chemerys JV, Pasternak OI (2017) Directly, the competitiveness of the tourism industry in Ukraine. Int Sci J Int Sci 7:165–171

World Bank (2020) Global Economic Prospects, June 2020. Washington, DC. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33748 . Last assessed: 10/07/2020

World Tourism Organization (2020a) New Data Shows Impact of COVID-19 on Tourism as UNWTO Calls for Responsible Restart of the Sector, June 22, 2020. https://www.unwto.org/news/new-data-shows-impact-of-covid-19-on-tourism . Last assessed: 10/07/2020

World Tourism Organization (2020b) UNWTO World Tourism Barometer May 2020. Special focus on the Impact of COVID-19 (Summary). Retrieved from: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2020-05/Barometer%20-%20May%202020%20-%20Short.pdf . Last assessed: 17/07/2020

World Tourism Organization (2020c) International Tourism and covid-19 UNWTO online resource. Retrieved from: https://www.unwto.org/international-tourism-and-covid-19 . Last assessed: 15/07/2020

World Travel and Tourism Council (2020) Guidelines for WTTC’s Safe and Seamless Traveler Journey - Testing, Tracing and Health Certificates, June 2020. https://www.prevuemeetings.com/coronavirus/wttc-travel-guidelines/ . Last assessed: 15/07/2020

Zehrer A, Smeral E, Hallmann K (2016) Destination competitiveness: a comparison of subjective and objective indicators for winter sports areas J Travel Res 56(1):55–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0047287515625129

Zhamgaryan GA (2017) History of Tourism Development in the Arabian Countries on the Example of Jordan and the UAE. St. Petersburg

Download references

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank reviewers for their valuable comments on this article.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Sharjah, Sharjah, UAE

Asad A. Aburumman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Asad A. Aburumman .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions