Cruise Ship Pollution: Background, Laws and Regulations, and Key Issues

July 2, 2004 – December 15, 2010 RL32450

The cruise industry is a significant and growing contributor to the U.S. economy, providing more than $32 billion in benefits annually and generating more than 330,000 U.S. jobs, but also making the environmental impacts of its activities an issue to many. Although cruise ships represent a small fraction of the entire shipping industry worldwide, public attention to their environmental impacts comes in part from the fact that cruise ships are highly visible and in part because of the industry’s desire to promote a positive image.

Cruise ships carrying several thousand passengers and crew have been compared to “floating cities,” and the volume of wastes that they produce is comparably large, consisting of sewage; wastewater from sinks, showers, and galleys (graywater); hazardous wastes; solid waste; oily bilge water; ballast water; and air pollution. The waste streams generated by cruise ships are governed by a number of international protocols (especially MARPOL) and U.S. domestic laws (including the Clean Water Act and the Act to Prevent Pollution from Ships), regulations, and standards, but there is no single law or rule. Some cruise ship waste streams appear to be well regulated, such as solid wastes (garbage and plastics) and bilge water. But there is overlap of some areas, and there are gaps in others. Some, such as graywater and ballast water, are not regulated (except in the Great Lakes), and concern is increasing about the impacts of these discharges on public health and the environment. In other areas, regulations apply, but critics argue that they are not stringent enough to address the problem—for example, with respect to standards for sewage discharges. Environmental advocates have raised concerns about the adequacy of existing laws for managing these wastes, and they contend that enforcement is weak.

In 2000, Congress enacted legislation restricting cruise ship discharges in U.S. navigable waters within the state of Alaska. California, Alaska, and Maine have enacted state-specific laws concerning cruise ship pollution, and a few other states have entered into voluntary agreements with industry to address management of cruise ship discharges. Meanwhile, the cruise industry has voluntarily undertaken initiatives to improve pollution prevention, by adopting waste management guidelines and procedures and researching new technologies. Concerns about cruise ship pollution raise issues for Congress in three broad areas: adequacy of laws and regulations, research needs, and oversight and enforcement of existing requirements. Legislation to regulate cruise ship discharges of sewage, graywater, and bilge water nationally was introduced in the 111th Congress (H.R. 3888 and S. 1820), but no legislative activity occurred on either bill.

This report describes the several types of waste streams that cruise ships may discharge and emit. It identifies the complex body of international and domestic laws that address pollution from cruise ships. It then describes federal and state legislative activity concerning cruise ships in Alaskan waters and activities in a few other states, as well as current industry initiatives to manage cruise ship pollution. Issues for Congress are discussed.

Topic areas

Economic Policy

Introduction

Cruise ship waste streams, applicable laws and regulations, international legal regime, domestic laws and regulations, solid waste, hazardous waste, bilge water, ballast water, air pollution, considerations of geographic jurisdiction, alaskan activities, federal legislation, alaska state legislation and initiatives, other state activities, industry initiatives, issues for congress, laws and regulations, oversight and enforcement.

The cruise industry is a significant and growing contributor to the U.S. economy, providing more than $32 billion in benefits annually and generating more than 330,000 U.S. jobs, but also making the environmental impacts of its activities an issue to many. Although cruise ships represent a small fraction of the entire shipping industry worldwide, public attention to their environmental impacts comes in part from the fact that cruise ships are highly visible and in part because of the industry's desire to promote a positive image.

Cruise ships carrying several thousand passengers and crew have been compared to "floating cities," and the volume of wastes that they produce is comparably large, consisting of sewage; wastewater from sinks, showers, and galleys (graywater); hazardous wastes; solid waste; oily bilge water; ballast water; and air pollution. The waste streams generated by cruise ships are governed by a number of international protocols (especially MARPOL) and U.S. domestic laws (including the Clean Water Act and the Act to Prevent Pollution from Ships), regulations, and standards, but there is no single law or rule. Some cruise ship waste streams appear to be well regulated, such as solid wastes (garbage and plastics) and bilge water. But there is overlap of some areas, and there are gaps in others. Some, such as graywater and ballast water, are not regulated (except in the Great Lakes), and concern is increasing about the impacts of these discharges on public health and the environment. In other areas, regulations apply, but critics argue that they are not stringent enough to address the problem—for example, with respect to standards for sewage discharges. Environmental advocates have raised concerns about the adequacy of existing laws for managing these wastes, and they contend that enforcement is weak.

In 2000, Congress enacted legislation restricting cruise ship discharges in U.S. navigable waters within the state of Alaska. California, Alaska, and Maine have enacted state-specific laws concerning cruise ship pollution, and a few other states have entered into voluntary agreements with industry to address management of cruise ship discharges. Meanwhile, the cruise industry has voluntarily undertaken initiatives to improve pollution prevention, by adopting waste management guidelines and procedures and researching new technologies. Concerns about cruise ship pollution raise issues for Congress in three broad areas: adequacy of laws and regulations, research needs, and oversight and enforcement of existing requirements. Legislation to regulate cruise ship discharges of sewage, graywater, and bilge water nationally was introduced in the 111 th Congress ( H.R. 3888 and S. 1820 ), but no legislative activity occurred on either bill.

More than 53,000 commercial vessels—tankers, bulk carriers, container ships, barges, and passenger ships—travel the oceans and other waters of the world, carrying cargo and passengers for commerce, transport, and recreation. Their activities are regulated and scrutinized in a number of respects by international protocols and U.S. domestic laws, including those designed to protect against discharges of pollutants that could harm marine resources, other parts of the ambient environment, and human health. However, there are overlaps of some requirements, gaps in other areas, geographic differences in jurisdiction based on differing definitions, and questions about the adequacy of enforcement.

Public attention to the environmental impacts of the maritime industry has been especially focused on the cruise industry, in part because its ships are highly visible and in part because of the industry's desire to promote a positive image. It represents a relatively small fraction of the entire shipping industry worldwide. As of October 2010, passenger ships (which include cruise ships and ferries) composed about 13% of the world shipping fleet. 1 The cruise industry is a significant and growing contributor to the U.S. economy, providing $40 billion in total benefits in 2009 and generating more than 357,000 U.S. jobs, 2 but also making the environmental impacts of its activities an issue to many. Since 1990, the average annual growth rate in the number of cruise passengers worldwide has been 7.4%, and in 2010, cruises hosted an estimated 14.3 million passengers. The worldwide cruise ship fleet consists of more than 230 ships, and the majority are foreign-flagged, with Liberia and Panama being the most popular flag countries. 3 Foreign-flag cruise vessels owned by six companies account for nearly 95% of passenger ships operating in U.S. waters. Each year, the industry adds new ships to the total fleet, vessels that are bigger, more elaborate and luxurious, and that carry larger numbers of passengers and crew. Over the past two decades, the average ship size has been increasing at the rate of roughly 90 feet every five years. The average ship entering the market from 2008 to 2011 will be more than 1,050 feet long and will weigh more than 130,000 tons. 4

To the cruise ship industry, a key issue is demonstrating to the public that cruising is safe and healthy for passengers and the tourist communities that are visited by their ships. Cruise ships carrying several thousand passengers and crew have been compared to "floating cities," in part because the volume of wastes produced and requiring disposal is greater than that of many small cities on land. During a typical one-week voyage, a large cruise ship (with 3,000 passengers and crew) is estimated to generate 210,000 gallons of sewage; 1 million gallons of graywater (wastewater from sinks, showers, and laundries); more than 130 gallons of hazardous wastes; 8 tons of solid waste; and 25,000 gallons of oily bilge water. 5 Those wastes, if not properly treated and disposed of, can pose risks to human health, welfare, and the environment. Environmental advocates have raised concerns about the adequacy of existing laws for managing these wastes, and suggest that enforcement of existing laws is weak.

A 2000 General Accounting Office (GAO) report focused attention on problems of cruise vessel compliance with environmental requirements. 6 GAO found that between 1993 and 1998, foreign-flag cruise ships were involved in 87 confirmed illegal discharge cases in U.S. waters. A few of the cases included multiple illegal discharge incidents occurring over the six-year period. GAO reviewed three major waste streams (solids, hazardous chemicals, and oily bilge water) and concluded that 83% of the cases involved discharges of oil or oil-based products, the volumes of which ranged from a few drops to hundreds of gallons. The balance of the cases involved discharges of plastic or garbage. GAO judged that 72% of the illegal discharges were accidental, 15% were intentional, and 13% could not be determined. The 87 cruise ship cases represented 4% of the 2,400 illegal discharge cases by foreign-flag ships (including tankers, cargo ships and other commercial vessels, as well as cruise ships) confirmed during the six years studied by GAO. Although cruise ships operating in U.S. waters have been involved in a relatively small number of pollution cases, GAO said, several have been widely publicized and have led to criminal prosecutions and multimillion-dollar fines.

In 2000, a coalition of 53 environmental advocacy groups petitioned the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to take regulatory action to address pollution by cruise ships. 7 The petition called for an investigation of wastewater, oil, and solid waste discharges from cruise ships. In response, EPA agreed to study cruise ship discharges and waste management approaches. As part of that effort, in 2000 EPA issued a background document with preliminary information and recommendations for further assessment through data collection and public information hearings. 8 Subsequently, in December 2008, the agency released a cruise ship discharge assessment report as part of its response to the petition. This report summarized information on cruise ship waste streams and findings of recent data collection activities (especially from cruise ships operating in Alaskan waters). It also identified options to address ship discharges. 9

This report presents information on issues related to cruise ship pollution. It begins by describing the several types of waste streams and contaminants that cruise ships may generate and release. It identifies the complex body of international and domestic laws that address pollution from cruise ships, as there is no single law in this area. Some wastes are covered by international standards, some are subject to U.S. law, and for some there are gaps in law, regulation, or possibly both. The report then describes federal and state legislative activity concerning cruise ships in Alaskan waters and activities in a few other states. Cruise ship companies have taken a number of steps to prevent illegal waste discharges and have adopted waste management plans and practices to improve their environmental operations. Environmental critics acknowledge these initiatives, even as they have petitioned the federal government to strengthen existing regulation of cruise ship wastes. Environmental groups endorsed legislation in the 109 th and 110 th Congresses (the Clean Cruise Ship Act) that would require stricter standards to control wastewater and other discharges from cruise ships. Similar legislation was introduced in the 111 th Congress (the Clean Cruise Ship Act, H.R. 3888 and S. 1820 ), but no legislative action occurred.

Cruise ships generate a number of waste streams that can result in discharges to the marine environment, including sewage, graywater, hazardous wastes, oily bilge water, ballast water, and solid waste. They also emit air pollutants to the air and water. These wastes, if not properly treated and disposed of, can be a significant source of pathogens, nutrients, and toxic substances with the potential to threaten human health and damage aquatic life. It is important, however, to keep these discharges in some perspective, because cruise ships represent a small—although highly visible—portion of the entire international shipping industry, and the waste streams described here are not unique to cruise ships. However, particular types of wastes, such as sewage, graywater, and solid waste, may be of greater concern for cruise ships relative to other seagoing vessels, because of the large numbers of passengers and crew that cruise ships carry and the large volumes of wastes that they produce. Further, because cruise ships tend to concentrate their activities in specific coastal areas and visit the same ports repeatedly (especially Florida, California, New York, Galveston, Seattle, and the waters of Alaska), their cumulative impact on a local scale could be significant, as can impacts of individual large-volume releases (either accidental or intentional).

Blackwater is sewage, wastewater from toilets and medical facilities, which can contain harmful bacteria, pathogens, diseases, viruses, intestinal parasites, and harmful nutrients. Discharges of untreated or inadequately treated sewage can cause bacterial and viral contamination of fisheries and shellfish beds, producing risks to public health. Nutrients in sewage, such as nitrogen and phosphorous, promote excessive algal growth, which consumes oxygen in the water and can lead to fish kills and destruction of other aquatic life. Cruise ships generate, on average, 8.4 gallons/day/person of sewage, and a large cruise ship (3,000 passengers and crew) can generate an estimated 15,000 to 30,000 gallons per day of sewage. 10

Graywater is wastewater from the sinks, showers, galleys, laundry, and cleaning activities aboard a ship. It can contain a variety of pollutant substances, including fecal coliform bacteria, detergents, oil and grease, metals, organics, petroleum hydrocarbons, nutrients, food waste, and medical and dental waste. Sampling done by EPA and the state of Alaska found that untreated graywater from cruise ships can contain pollutants at variable strengths, and that it can contain levels of fecal coliform bacteria one to three times greater than is typically found in untreated domestic wastewater. Cruise ships generate, on average, 67 gallons/day/person of graywater (or, approximately 200,000 gallons per day for a 3,000-person cruise ship); by comparison, residential graywater generation is estimated to be 51 gallons/person/day. 11 Graywater has potential to cause adverse environmental effects because of concentrations of nutrients and other oxygen-demanding materials, in particular. Graywater is typically the largest source of liquid waste generated by cruise ships (90%-95% of the total).

Solid waste generated on a ship includes glass, paper, cardboard, aluminum and steel cans, and plastics. It can be either non-hazardous or hazardous in nature. Solid waste that enters the ocean may become marine debris, and it can then pose a threat to marine organisms, humans, coastal communities, and industries that utilize marine waters. Cruise ships typically manage solid waste by a combination of source reduction, waste minimization, and recycling. However, as much as 75% of solid waste is incinerated on board, and the ash typically is discharged at sea, although some is landed ashore for disposal or recycling. Marine mammals, fish, sea turtles, and birds can be injured or killed from entanglement with plastics and other solid waste that may be released or disposed off of cruise ships. On average, each cruise ship passenger generates at least two pounds of non-hazardous solid waste per day and disposes of two bottles and two cans. 12 With large cruise ships carrying several thousand passengers, the amount of waste generated in a day can be massive. For a large cruise ship, about 8 tons of solid waste are generated during a one-week cruise. 13 It has been estimated that 24% of the solid waste generated by vessels worldwide (by weight) comes from cruise ships. 14 Most cruise ship garbage is treated on board (incinerated, pulped, or ground up) for discharge overboard. When garbage must be off-loaded (for example, because glass and aluminum cannot be incinerated), cruise ships can put a strain on port reception facilities, which are rarely adequate to the task of serving a large passenger vessel (especially at non-North American ports). 15

Cruise ships produce hazardous wastes from a number of on-board activities and processes, including photo processing, dry-cleaning, and equipment cleaning. Types of waste include discarded and expired chemicals, medical waste, batteries, fluorescent lights, and spent paints and thinners, among others. These materials contain a wide range of substances such as hydrocarbons, chlorinated hydrocarbons, heavy metals, paint waste, solvents, fluorescent and mercury vapor light bulbs, various types of batteries, and unused or outdated pharmaceuticals. Although the quantities of hazardous waste generated on cruise ships are relatively small, their toxicity to sensitive marine organisms can be significant. Without careful management, these wastes can find their way into graywater, bilge water, or the solid waste stream.

On a ship, oil often leaks from engine and machinery spaces or from engine maintenance activities and mixes with water in the bilge, the lowest part of the hull of the ship. Oil, gasoline, and byproducts from the biological breakdown of petroleum products can harm fish and wildlife and pose threats to human health if ingested. Oil in even minute concentrations can kill fish or have various sub-lethal chronic effects. Bilge water also may contain solid wastes and pollutants containing high amounts of oxygen-demanding material, oil, and other chemicals, as well as soaps, detergents, and degreasers used to clean the engine room. These chemicals can be highly toxic, causing mortality to marine organisms if the chemicals are discharged. Amounts vary, depending on the size of the ship, but large vessels often have additional waste streams that contain sludge or waste oil and oily water mixtures that can inadvertently get into the bilge. A typical large cruise ship will generate an average of eight metric tons of oily bilge water for each 24 hours of operation. 16 To maintain ship stability and eliminate potentially hazardous conditions from oil vapors in these areas, the bilge spaces need to be flushed and periodically pumped dry. However, before a bilge can be cleared out and the water discharged, the oil that has been accumulated needs to be extracted from the bilge water, after which the extracted oil can be reused, incinerated, and/or off-loaded in port. If a separator, which is normally used to extract the oil, is faulty or is deliberately bypassed, untreated oily bilge water could be discharged directly into the ocean, where it can damage marine life. According to EPA, bilge water is the most common source of oil pollution from cruise ships. 17 A number of cruise lines have been charged with environmental violations related to this issue in recent years.

Cruise ships, large tankers, and bulk cargo carriers use a tremendous amount of ballast water to stabilize the vessel during transport. Ballast water is often taken on in the coastal waters in one region after ships discharge wastewater or unload cargo, and discharged at the next port of call, wherever more cargo is loaded, which reduces the need for compensating ballast. Thus, it is essential to the proper functioning of ships (especially cargo ships), because the water that is taken in compensates for changes in the ship's weight as cargo is loaded or unloaded, and as fuel and supplies are consumed. However, ballast water discharge typically contains a variety of biological materials, including plants, animals, viruses, and bacteria. These materials often include non-native, nuisance, exotic species that can cause extensive ecological and economic damage to aquatic ecosystems. Ballast water discharges are believed to be the leading source of invasive species in U.S. marine waters, thus posing public health and environmental risks, as well as significant economic cost to industries such as water and power utilities, commercial and recreational fisheries, agriculture, and tourism. 18 Studies suggest that the economic cost just from introduction of pest mollusks (zebra mussels, the Asian clam, and shipworms) to U.S. aquatic ecosystems is about $2.2 billion per year. 19 These problems are not limited to cruise ships, and there is little cruise-industry specific data on the issue. Further study is needed to determine the role of cruise ships in the overall problem of introduction of non-native species by vessels.

Air pollution from cruise ships is generated by diesel engines that burn high sulfur content fuel, producing sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxide, and particulate matter, in addition to carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and hydrocarbons. Diesel exhaust has been classified by EPA as a likely human carcinogen. EPA recognizes that emissions from marine diesel engines contribute to unhealthy air and failure to meet air quality standards, as well as visibility degradation, haze, acid deposition, and eutrophication and nitrification of water. 20 EPA estimates that ocean-going vessels account for about 10% of mobile source nitrogen oxide emissions, 24% of mobile source particulate emissions, and 80% of mobile source sulfur dioxide emissions in the United States in 2009. These percentages are expected to increase as other sources of these pollutants are controlled. Emissions from marine diesel engines can be higher on a port-specific basis. Ships are also an important source of greenhouse gas (GHG) pollutants. The International Maritime Organization estimates that international shipping contributed 2.7% of global carbon dioxide emissions in 2007. 21 Vessels also emit significant amounts of black carbon and nitrogen oxides, which contribute to climate change.

One source of environmental pressures on maritime vessels recently has come from states and localities, as they assess the contribution of commercial marine vessels to regional air quality problems when ships are docked in port. A significant portion of vessel emissions occur at sea, but they can impact areas far inland and regions without large commercial ports, according to EPA. Again, there is little cruise-industry specific data on this issue. They comprise only a small fraction of the world shipping fleet, but cruise ship emissions may exert significant impacts on a local scale in specific coastal areas that are visited repeatedly. Shipboard incinerators also burn large volumes of garbage, plastics, and other waste, producing ash that must be disposed of. Incinerators may release toxic emissions as well.

The several waste streams generated by cruise ships are governed by a number of international protocols and U.S. domestic laws, regulations and standards, which are described in this section, but there is no single law or regulation. Moreover, there are overlaps in some areas of coverage, gaps in other areas, and differences in geographic jurisdiction, based on applicable terms and definitions.

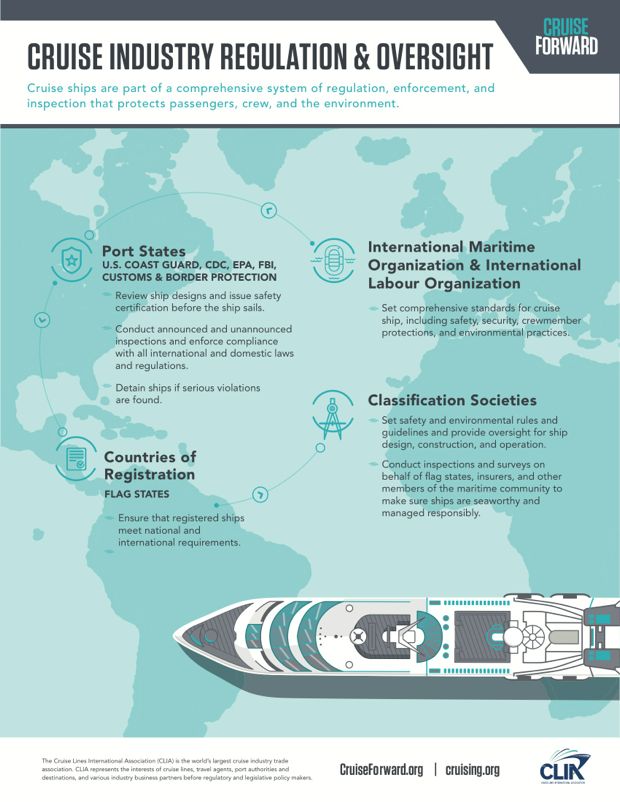

The International Maritime Organization (IMO), a body of the United Nations, sets international maritime vessel safety and marine pollution standards. It consists of representatives from 152 major maritime nations, including the United States. The IMO implements the 1973 International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, as modified by the Protocol of 1978, known as MARPOL 73/78. Cruise ships flagged under countries that are signatories to MARPOL are subject to its requirements, regardless of where they sail, and member nations are responsible for vessels registered under their respective nationalities. 22 Six Annexes of the Convention cover the various sources of pollution from ships and provide an overarching framework for international objectives, but they are not sufficient alone to protect the marine environment from waste discharges, without ratification and implementation by sovereign states.

- Annex I deals with regulations for the prevention of pollution by oil.

- Annex II details the discharge criteria and measures for the control of pollution by noxious liquid substances carried in bulk.

- Annex III contains general requirements for issuing standards on packing, marking, labeling, and notifications for preventing pollution by harmful substances.

- Annex IV contains requirements to control pollution of the sea by sewage.

- Annex V deals with different types of garbage, including plastics, and specifies the distances from land and the manner in which they may be disposed of.

- Annex VI sets limits on sulfur oxide, nitrogen oxide, and other emissions from marine vessel operations and prohibits deliberate emissions of ozone-depleting substances.

Compliance with the Annexes is voluntary. In order for IMO standards to be binding, they must first be ratified by a total number of member countries whose combined gross tonnage represents at least 50% of the world's gross tonnage, a process that can be lengthy. Parties/countries that have ratified an Annex may propose amendments; MARPOL specifies procedures and timelines for parties to adopt amendments and for amendments to take effect. All six Annexes have been ratified by the requisite number of nations; the most recent is Annex VI, which took effect in May 2005. The United States has ratified Annexes I, II, III, V, and VI, but has taken no action regarding Annex IV. The country where a ship is registered (flag state) is responsible for certifying the ship's compliance with MARPOL's pollution prevention standards. IMO also has established a large number of other conventions, addressing issues such as ballast water management, and the International Safety Management Code, with guidelines for passenger safety and pollution prevention.

Each signatory nation is responsible for enacting domestic laws to implement the convention and effectively pledges to comply with the convention, annexes, and related laws of other nations. In the United States, the Act to Prevent Pollution from Ships (APPS, 33 U.S.C. §§1905-1915, and regulations at 33 CFR Subchapter O—Pollution) implements the provisions of MARPOL and the annexes to which the United States is a party. The most recent U.S. action concerning MARPOL occurred in April 2006, when the Senate acceded to ratification of Annex VI, which regulates air pollution (Treaty Doc. 108-7, Exec. Rept. 109-13). Following that approval, in July 2008, Congress approved legislation to implement the standards in Annex VI, through regulations to be promulgated by EPA in consultation with the U.S. Coast Guard ( P.L. 110-280 ). Even before enactment of this legislation, the United Stated participated in international negotiations to strengthen MARPOL Annex VI , which resulted in amendments to Annex VI in October 2008 (see discussion of " Air Pollution ," below). 23

APPS applies to all U.S.-flagged ships anywhere in the world and to all foreign-flagged vessels operating in navigable waters of the United States or while at port under U.S. jurisdiction. The Coast Guard has primary responsibility to prescribe and enforce regulations necessary to implement APPS in these waters. The regulatory mechanism established in APPS to implement MARPOL is separate and distinct from the Clean Water Act and other federal environmental laws.

One of the difficulties in implementing MARPOL arises from the very international nature of maritime shipping. The country that the ship visits can conduct its own examination to verify a ship's compliance with international standards and can detain the ship if it finds significant noncompliance. Under the provisions of the Convention, the United States can take direct enforcement action under U.S. laws against foreign-flagged ships when pollution discharge incidents occur within U.S. jurisdiction. When incidents occur outside U.S. jurisdiction or jurisdiction cannot be determined, the United States refers cases to flag states, in accordance with MARPOL. The 2000 GAO report documented that these procedures require substantial coordination between the Coast Guard, the State Department, and other flag states and that, even when referrals have been made, the response rate from flag states has been poor. 24

In the United States, several federal agencies have some jurisdiction over cruise ships in U.S. waters, but no one agency is responsible for or coordinates all of the relevant government functions. The U.S. Coast Guard and EPA have principal regulatory and standard-setting responsibilities, and the Department of Justice prosecutes violations of federal laws. In addition, the Department of State represents the United States at meetings of the IMO and in international treaty negotiations and is responsible for pursuing foreign-flag violations. Other federal agencies have limited roles and responsibilities. For example, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA, Department of Commerce) works with the Coast Guard and EPA to report on the effects of marine debris. The Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) is responsible for ensuring quarantine inspection and disposal of food-contaminated garbage (these APHIS responsibilities are part of the Department of Homeland Security). In some cases, states and localities have responsibilities as well. This section describes U.S. laws and regulations that apply to cruise ship discharges.

The Federal Water Pollution Control Act, or Clean Water Act (CWA), is the principal U.S. law concerned with limiting polluting activity in the nation's streams, lakes, estuaries, and coastal waters. The act's primary mechanism for controlling pollutant discharges is the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) program, authorized in Section 402. In accordance with the NPDES program, pollutant discharges from point sources—a term that includes vessels—are prohibited unless a permit has been obtained. While sewage is defined as a pollutant under the act, sewage discharges from cruise ships and other vessels are statutorily exempt from this definition and are therefore exempt from the requirement to obtain an NPDES permit.

Marine Sanitation Devices

Section 312 of the Clean Water Act seeks to address this gap by prohibiting the dumping of untreated or inadequately treated sewage from vessels into the navigable waters of the United States (defined in the act as within 3 miles of shore). Cruise ships are subject to this prohibition. It is implemented jointly by EPA and the Coast Guard. Under Section 312, commercial and recreational vessels with installed toilets are required to have marine sanitation devices (MSDs), which are designed to prevent the discharge of untreated sewage. EPA is responsible for developing performance standards for MSDs, and the Coast Guard is responsible for MSD design and operation regulations and for certifying MSD compliance with the EPA rules. MSDs are designed either to hold sewage for shore-based disposal or to treat sewage prior to discharge. Beyond 3 miles, raw sewage can be discharged.

The Coast Guard regulations cover three types of MSDs (33 CFR Part 159). Large vessels, including cruise ships, use either Type II or Type III MSDs. In Type II MSDs, the waste is either chemically or biologically treated prior to discharge and must meet limits of no more than 200 fecal coliform per 100 milliliters and no more than 150 milligrams per liter of suspended solids. Type III MSDs store wastes and do not treat them; the waste is pumped out later and treated in an onshore system or discharged outside U.S. waters. Type I MSDs use chemicals to disinfect the raw sewage prior to discharge and must meet a performance standard for fecal coliform bacteria of not greater than 1,000 per 100 milliliters and no visible floating solids. Type I MSDs are generally only found on recreational vessels or others under 65 feet in length. The regulations, which have not been revised since 1976, do not require ship operators to sample, monitor, or report on their effluent discharges.

Critics point out deficiencies with this regulatory structure as it affects cruise ships and other large vessels. First, the MSD regulations only cover discharges of bacterial contaminants and suspended solids, while the NPDES permit program for other point sources typically regulates many more pollutants such as chemicals, pesticides, heavy metals, oil, and grease that may be released by cruise ships as well as land-based sources. Second, sources subject to NPDES permits must comply with sampling, monitoring, recordkeeping, and reporting requirements, which do not exist in the MSD rules.

In addition, the Coast Guard, responsible for inspecting cruise ships and other vessels for compliance with the MSD rules, has been heavily criticized for poor enforcement of Section 312 requirements. In its 2000 report, the GAO said that Coast Guard inspectors "rarely have time during scheduled ship examinations to inspect sewage treatment equipment or filter systems to see if they are working properly and filtering out potentially harmful contaminants." GAO reported that a number of factors limit the ability of Coast Guard inspectors to detect violations of environmental law and rules, including the inspectors' focus on safety, the large size of a cruise ship, limited time and staff for inspections, and the lack of an element of surprise concerning inspections. 25 The Coast Guard carries out a wide range of responsibilities that encompass both homeland security (ports, waterways, and coastal security, defense readiness, drug and migrant interdiction) and non-homeland security (search and rescue, marine environmental protection, fisheries enforcement, aids to navigation). Since the September 11 terrorist attacks on the United States, the Coast Guard has focused more of its resources on homeland security activities. 26 One likely result is that less of the Coast Guard's time and resources are available for vessel inspections for MSD or other environmental compliance.

Annex IV of MARPOL was drafted to regulate sewage discharges from vessels. It generally requires that ships be equipped with either a sewage treatment plant, sewage comminuting (i.e., to grind or macerate solids) and disinfecting system, or a sewage holding tank. It has entered into force internationally and would apply to cruise ships that are flagged in ratifying countries, but because the United States has not ratified Annex IV, it is not mandatory that ships follow it when in U.S. waters. However, its requirements are minimal, even compared with U.S. rules for MSDs. Annex IV requires that vessels be equipped with a certified sewage treatment system or holding tank, but it prescribes no specific performance standards. Within three miles of shore, Annex IV requires that sewage discharges be treated by a certified MSD prior to discharge. Between three and 12 miles from shore, sewage discharges must be treated by no less than maceration or chlorination; sewage discharges beyond 12 miles from shore are unrestricted. Vessels are permitted to meet alternative, less stringent requirements when they are in the jurisdiction of countries where less stringent requirements apply. In U.S. waters, cruise ships and other vessels must comply with the regulations implementing Section 312 of the Clean Water Act.

On some cruise ships, especially many of those that travel in Alaskan waters, sewage is treated using Advanced Wastewater Treatment (AWT) systems that generally provide improved screening, treatment, disinfection, and sludge processing as compared with traditional Type II MSDs. AWTs are believed to be very effective in removing pathogens, oxygen demanding substances, suspended solids, oil and grease, and particulate metals from sewage, but only moderately effective in removing dissolved metals and nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorous). 27

No Discharge Zones

Section 312 has another means of addressing sewage discharges, through establishment of no-discharge zones (NDZs) for vessel sewage. A state may completely prohibit the discharge of both treated and untreated sewage from all vessels with installed toilets into some or all waters over which it has jurisdiction (up to 3 miles from land). To create a no-discharge zone to protect waters from sewage discharges by cruise ships and other vessels, the state must apply to EPA under one of three categories.

- NDZ based on the need for greater environmental protection, and the state demonstrates that adequate pumpout facilities for safe and sanitary removal and treatment of sewage from all vessels are reasonably available. As of 2009, this category of designation has been used for waters representing part or all of the waters of 26 states, including a number of inland states.

- NDZ for special waters found to have a particular environmental importance (e.g., to protect environmentally sensitive areas such as shellfish beds or coral reefs); it is not necessary for the state to show pumpout availability. This category of designation has been used twice (state waters within the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and the Boundary Waters Canoe area of Minnesota).

- NDZ to prohibit the discharge of sewage into waters that are drinking water intake zones; it is not necessary for the state to show pumpout availability. This category of designation has been used to protect part of the Hudson River in New York.

In the 2008 Discharge Assessment Report, EPA identified several possible options to address sewage from cruise ships, such as revising standards for the discharge of treated sewage effluent, restricting discharge of treated or untreated sewage effluent (e.g., no discharge out to 3 miles from shore), requiring sampling and testing of wastewater treatment equipment to ensure that its meets applicable standards, requiring certain reports by cruise ship operators, or imposing uniform requirements on all ships as a condition of port entry and within U.S. waters. 28

Under current federal law, graywater is not defined as a pollutant, nor is it generally considered to be sewage. There are no separate federal effluent standards for graywater discharges. The Clean Water Act only includes graywater in its definition of sewage for the express purpose of regulating commercial vessels in the Great Lakes, under the Section 312 MSD requirements. However, those rules prescribe limits only for bacterial contaminant content and total suspended solids in graywater. Pursuant to a state law in Alaska, graywater must be treated prior to discharge into that state's waters (see " Alaskan Activities ," below). In addition, in 2008, EPA issued a CWA general permit applicable to large commercial vessels, including cruise ships, that contains restrictions on graywater discharges similar to those that apply in Alaskan waters (see " EPA's Response: General Permits for Vessels ," below).

The National Marine Sanctuaries Act (16 USC § 1431 et seq.) authorizes NOAA to designate National Marine Sanctuaries where certain discharges, including graywater, may be restricted to protect sensitive ecosystems or fragile habitat, such as coral. NOAA regulations do restrict such discharges from cruise ships and other vessels in areas such as the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary and the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

In the 2008 Discharge Assessment Report, EPA identified several options or alternatives for addressing graywater discharges, such as establishing and/or revising standards for graywater discharges, placing geographic restrictions on graywater discharges, requiring monitoring and reporting, or imposing penalties for failure to meet graywater standards. 29

Cruise ship discharges of solid waste are governed by two laws. Title I of the Marine Protection, Research and Sanctuaries Act (MPRSA, 33 U.S.C. §§ 1402-1421) applies to cruise ships and other vessels and makes it illegal to transport garbage from the United States for the purpose of dumping it into ocean waters without a permit or to dump any material transported from a location outside the United States into U.S. territorial seas or the contiguous zone (within 12 nautical miles from shore) or ocean waters. EPA is responsible for issuing permits that regulate the disposal of materials at sea (except for dredged material disposal, for which the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is responsible). Beyond waters that are under U.S. jurisdiction, no MPRSA permit is required for a cruise ship to discharge solid waste. The routine discharge of effluent incidental to the propulsion of vessels is explicitly exempted from the definition of dumping in the MPRSA. 30

The Act to Prevent Pollution from Ships (APPS, 33 U.S.C. §§ 1901-1915) and its regulations, which implement U.S.-ratified provisions of MARPOL Annex V, also apply to cruise ships. APPS prohibits the discharge of all garbage within 3 nautical miles of shore, certain types of garbage within 12 nautical miles offshore, and plastic anywhere. As described above, it applies to all vessels, whether seagoing or not, regardless of flag, operating in U.S. navigable waters and the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). It is administered by the Coast Guard which carries out inspection programs to insure the adequacy of port facilities to receive offloaded solid waste. According to EPA, there have been discharges of solid waste and plastic from cruise ships. 31 The IMO also is reportedly evaluating the need to amend Annex V of MARPOL.

In the 2008 Discharge Assessment Report, EPA identified several possible options to address solid waste from cruise ships, such as increasing the use and range of on-board garbage handling and treatment technologies (e.g., compactors and incinerators); initiating a rulemaking to provide stronger waste management plans than the current voluntary cruise industry practices; prohibiting discharge of incinerator ash from cruise ships into U.S. waters; expanding port reception facilities to accept solid waste; or ensuring that there is no discharge of solid waste into the marine environment through monitoring and sanctions. 32

The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA, 42 U.S.C. §§ 6901-6991k) is the primary federal law that governs hazardous waste management through a "cradle-to-grave" program that controls hazardous waste from the point of generation until ultimate disposal. The act imposes management requirements on generators, transporters, and persons who treat or dispose of hazardous waste. Under this act, a waste is hazardous if it is ignitable, corrosive, reactive, or toxic, or appears on a list of about 100 industrial process waste streams and more than 500 discarded commercial products and chemicals. Treatment, storage, and disposal facilities are required to have permits and comply with operating standards and other EPA regulations.

The owner or operator of a cruise ship may be a generator and/or a transporter of hazardous waste, and thus subject to RCRA rules. Issues that the cruise ship industry may face relating to RCRA include ensuring that hazardous waste is identified at the point at which it is considered generated; ensuring that parties are properly identified as generators, storers, treaters, or disposers; and determining the applicability of RCRA requirements to each. Hazardous wastes generated onboard cruise ships are stored onboard until the wastes can be offloaded for recycling or disposal in accordance with RCRA. 33

A range of activities on board cruise ships generate hazardous wastes and toxic substances that would ordinarily be presumed to be subject to RCRA—for example, for use of chemicals in cleaning and painting, or in passenger services such as beauty parlors and photo labs. Cruise ships are potentially subject to RCRA requirements to the extent that chemicals used for operations such as ship maintenance and passenger services result in the generation of hazardous wastes. However, it is not entirely clear what regulations apply to the management and disposal of these wastes. 34 RCRA rules that cover small-quantity generators (those that generate more than 100 kilograms but less than 1,000 kilograms of hazardous waste per month) are less stringent than those for large-quantity generators (generating more than 1,000 kilograms per month), and it is unclear whether cruise ships are classified as large or small generators of hazardous waste. Moreover, some cruise companies argue that they generate less than 100 kilograms per month and therefore should be classified in a third category, as "conditionally exempt small-quantity generators," a categorization that allows for less rigorous requirements for notification, recordkeeping, and the like. 35

A release of hazardous substances by a cruise ship or other vessel could also theoretically trigger the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA, or Superfund, 42 U.S.C. §§ 9601-9675), but it does not appear to have been used in response to cruise ship releases. CERCLA requires that any person in charge of a vessel shall immediately notify the National Response Center of any release of a hazardous substance in amounts above regulatory thresholds (other than discharges in compliance with a federal permit under the Clean Water Act or other environmental law, as these discharges are exempted) into waters of the United States or the contiguous zone. Notification is required for releases in amounts determined by EPA that may present substantial danger to the public health, welfare, or the environment. EPA has identified 500 wastes as hazardous substances under these provisions and issued rules on quantities that are reportable, covering releases as small as 1 pound of some substances (40 CFR Part 302). CERCLA authorizes the President (acting through the Coast Guard in coastal waters) to remove and provide for remedial action relating to the release.

In addition to RCRA, hazardous waste discharges from cruise ships are subject to Section 311 of the Clean Water Act, which prohibits the discharge of hazardous substances in harmful quantities into or upon the navigable waters of the United States, adjoining shorelines, or into or upon the waters of the contiguous zone.

In the 2008 Discharge Assessment Report, EPA identified several possible options for addressing hazardous wastes, such as establishing standards of BMPs to decrease contaminants in hazardous wastes or the volume of hazardous waste on cruise ships; beginning a rulemaking to prohibit the discharge of hazardous materials into U.S. waters out to the 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone; increasing inspections on cruise ships; or increasing inspections of authorized facilities that receive cruise ship hazardous wastes. 36

Section 311 of the Clean Water Act, as amended by the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (33 U.S.C. §§ 2701-2720), applies to cruise ships and prohibits discharge of oil or hazardous substances in harmful quantities into or upon U.S. navigable waters, or into or upon the waters of the contiguous zone, or which may affect natural resources in the U.S. EEZ (extending 200 miles offshore). Coast Guard regulations (33 CFR §151.10) prohibit discharge of oil within 12 miles from shore, unless passed through a 15-ppm oil water separator, and unless the discharge does not cause a visible sheen. Beyond 12 miles, oil or oily mixtures can be discharged while a vessel is proceeding en route and if the oil content without dilution is less than 100 ppm. Vessels are required to maintain an Oil Record Book to record disposal of oily residues and discharges overboard or disposal of bilge water.

In addition to Section 311 requirements, the Act to Prevent Pollution from Ships (APPS) implements MARPOL Annex I concerning oil pollution. APPS applies to all U.S. flagged ships anywhere in the world and to all foreign flagged vessels operating in the navigable waters of the United States, or while at a port under U.S. jurisdiction. To implement APPS, the Coast Guard has promulgated regulations prohibiting the discharge of oil or oily mixtures into the sea within 12 nautical miles of the nearest land, except under limited conditions. However, because most cruise lines are foreign registered and because APPS only applies to foreign ships within U.S. navigable waters, the APPS regulations have limited applicability to cruise ship operations. In addition, most cruise lines have adopted policies that restrict discharges of machinery space waste within three miles from shore.

In the 2008 Discharge Assessment Report, EPA identified several possible options for addressing oily bilge water from cruise ships, such as establishing standards; conducting research on alternative lubricants; treating effluents from oily bilge water to meet specified standards and establishing penalties for failure to meet standards; banning discharge of bilge water into U.S. waters; or revising inspection practices to more aggressively identify noncompliant equipment. 37

Since the 1970s, Clean Water Act regulations had exempted ballast water and other discharges incidental to the normal operation of cruise ships and other vessels from NPDES permit requirements. Because of the growing problem of introduction of invasive species into U.S. waters via ballast water (see discussion, page 5 ), in January 1999, a number of conservation organizations, fishing groups, Native American tribes, and water agencies petitioned EPA to repeal its 1973 regulation exempting ballast water discharge, arguing that ballast water should be regulated as the "discharge of a pollutant" under the Clean Water Act's Section 402 permit program. EPA rejected the petition in September 2003, saying that the "normal operation" exclusion is long-standing agency policy, to which Congress has acquiesced twice (in 1979 and 1996) when it considered the issue of aquatic nuisance species in ballast water and did not alter EPA's CWA interpretation. 38 Further, EPA said that other ongoing federal activities related to control of invasive species in ballast water are likely to be more effective than changing the NPDES rules. 39 Until 2004, these efforts to limit ballast water discharges by cruise ships and other vessels were primarily voluntary, except in the Great Lakes. Since then, all vessels equipped with ballast water tanks must have a ballast water management plan. 40

After the denial of their administrative petition, the environmental groups filed a lawsuit seeking to force EPA to rescind the regulation that exempts ballast water discharges from CWA permitting. In 2005, a federal district court ruled in favor of the groups, and in 2006, the court remanded the matter to EPA with an order that the challenged regulation be set aside by September 30, 2008. The ruling was upheld on appeal in July 2008. 41

EPA's Response: General Permits for Vessels

Significantly, while the focus of the environmental groups' challenge was principally to EPA's permitting exemption for ballast water discharges, the court's ruling—and its mandate to EPA to rescind the exemption in 40 CFR § 122.3(a)—applies fully to other types of vessel discharges that were covered by the long-standing regulatory exemption for "discharges incidental to the normal operation of vessels," including graywater and bilge water. In response to the court's order, in December 2008, EPA issued a Clean Water Act general permit, 42 the Vessel General Permit (VGP), applicable to an estimated 69,000 large recreational and commercial vessels, including tankers, freighters, barges, and approximately 175 U.S. and foreign flagged cruise ships that carry and provide overnight accommodations for more than 100 passengers. 43

The VGP applies to pollutant discharges incidental to the normal operation from non-recreational vessels that are 79 feet or more in length, and to ballast water discharges from commercial vessels of less than 79 feet and commercial fishing vessels of any length. Geographically, it applies to discharges into waters of the United States in all states and territories, extending to the reach of the 3-mile territorial limit.

In the permit, EPA identified 26 types of waste streams from the normal operation of covered vessels (some are not applicable to all vessel types). The types of pollutant discharges subject to the permit include aquatic nuisance species, nutrients, pathogens, oil and grease, metals, and pollutants with toxic effects. Most of the categories of waste streams from the normal operations of these vessels would be controlled by best management practices (BMPs) that are described in the permit, many of which are already practiced or are required by existing regulations. To control ballast water discharges, the VGP primarily relies on existing Coast Guard requirements (at 33 CFR Part 151, Subparts C and D), plus certain flushing and ballast exchange practices, especially for vessels in Pacific nearshore areas. To control discharges of bilge water, the draft VGP provides for BMPs, which EPA indicates are consistent with current rules and industry practice. Monitoring, recordkeeping, and reporting requirements apply.

The VGP does not include sewage discharges from vessels, which are already regulated under CWA Section 312, as discussed previously in this report. Likewise, discharges of wastes associated with passenger services on cruise ships, such as photo developing and dry cleaning, that are toxic to the environment are not authorized by the permit.

Under the VGP, cruise ships are subject to more detailed requirements for certain discharges, such as graywater and pool and spa water, and additional monitoring and reporting. It includes BMPs as well as numeric effluent limits for fecal coliform and residual chlorine in cruise ship discharges of graywater that are based on U.S. Coast Guard rules for discharge of treated sewage or graywater in Alaska (see discussion below, page 19 ). It also includes operational limits on cruise ship graywater discharges in nutrient-impaired waters, such as Chesapeake Bay or Puget Sound.

The 110 th Congress considered ballast water discharge issues, specifically legislation to provide a uniform national approach for addressing aquatic nuisance species from ballast water under a program administered by the Coast Guard ( S. 1578 , ordered reported by the Senate Commerce Committee on September 27, 2007; and H.R. 2830 , passed by the House April 28, 2008). Some groups opposed S. 1578 and H.R. 2830 , because the legislation would preempt states from enacting ballast water management programs more stringent than Coast Guard requirements, while the CWA does allow states to adopt requirements more stringent than in federal rules. Also, while the CWA permits citizen suits to enforce the law, the legislation included no citizen suit provisions. There was no further action on this legislation.

The Clean Air Act (42 U.S.C. 7401 et seq.) is the principal federal law that addresses air quality concerns. It requires EPA to set health-based standards for ambient air quality, sets standards for the achievement of those standards, and sets national emission standards for large and ubiquitous sources of air pollution, including mobile sources. Cruise ships emissions were not regulated until February 2003. At that time, EPA promulgated emission standards for new marine diesel engines on large vessels (called Category 3 marine engines) such as container ships, tankers, bulk carriers, and cruise ships flagged or registered in the United States. 44 The 2003 rule resulted from settlement of litigation brought by the environmental group Bluewater Network after it had petitioned EPA to issue stringent emission standards for large vessels and cruise ships. Standards in the rule are equivalent to internationally negotiated standards set in Annex VI of the MARPOL protocol for nitrogen oxides, which engine manufacturers currently meet, according to EPA. 45 Emissions from these large, primarily ocean-going vessels (including container ships, tankers, bulk carriers, as well as cruise ships) had not previously been subject to EPA regulation. The rule is one of several EPA regulations establishing emissions standards for nonroad engines and vehicles, under Section 213(a) of the Clean Air Act. Smaller marine diesel engines are regulated under rules issued in 1996 and 1999.

In the 2003 rule, EPA announced that it would continue to review issues and technology related to emissions from large marine vessel engines in order to promulgate additional, more stringent emission standards for very large marine engines and vessels later. Addressing long-term standards in a future rulemaking, EPA said, could facilitate international efforts through the IMO (since the majority of ships used in international commerce are flagged in other nations), while also permitting the United States to proceed, if international standards are not adopted in a timely manner. Environmental groups criticized EPA for excluding foreign-flagged vessels that enter U.S. ports from the marine diesel engine rules and challenged the 2003 rules in federal court. The rules were upheld in June 2004. 46 EPA said that it would consider including foreign vessels in the future rulemaking to consider more stringent standards.

As noted previously, the 110 th Congress enacted legislation to implement MARPOL Annex VI, concerning standards to control air pollution from vessels. Soon after that U.S. action, in October 2008, the IMO adopted amendments to Annex VI that to establish stringent new global nitrogen oxide standards beginning in 2011, new global fuel sulfur standards beginning in 2012, plus more stringent emission controls that will apply in designated Emission Control Areas (ECAs). The United States supported the amendments during IMO negotiations. Complementing the IMO revisions, in December 2009, EPA promulgated changes to the 2003 CAA rules for Category 3 marine engines that essentially adopt the amended IMO requirements. 47 The EPA rule also establishes emissions standards for hydrocarbons and carbon monoxide. Like the new Annex VI requirements, the EPA rule applies to newly built engines (not existing) and only to U.S.-flagged or registered vessels. On the latter point, EPA said that engines on foreign vessels are subject to the nitrogen oxide limits in MARPOL Annex VI, which the United States can enforce through the Act to Prevent Pollution from Ships (APPS).

Related to these actions, in October 2010, the IMO approved a U.S. request to designate waters in the U.S. Caribbean (around Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands) as an ECA. A treaty amendment to Annex VI will be circulated among IMO members, and if approved by July 2011, ships operating in the designated area would be subject to more stringent emission limitations for sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter beginning in 2014.

The various laws and regulations described here apply to different geographic areas, depending on the terminology used. For example, the Clean Water Act treats navigable waters, the contiguous zone, and the ocean as distinct entities. The term "navigable waters" is defined to mean the waters of the United States, including the territorial seas (33 U.S.C. §1362(7)). In turn, the territorial seas are defined in that act as extending a distance of 3 miles seaward from the baseline (33 U.S.C. §1362(8)); the baseline generally means the land or shore. In 1988, President Reagan signed a proclamation (Proc. No. 5928, December 27, 1988, 54 Federal Register 777) providing that the territorial sea of the United States extends to 12 nautical miles from the U.S. baseline. However, that proclamation had no effect on the geographic reach of the Clean Water Act.

The contiguous zone is defined in the CWA to mean the entire zone established by the United States under Article 24 of the Convention of the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone (33 U.S.C. §1362(9)). That convention defines "contiguous zone" as extending from the baseline from which the territorial sea is measured to not beyond 12 miles. In 1999, President Clinton signed a proclamation (Proc. No. 7219 of August 2, 1999, 64 Federal Register 48701) giving U.S. authorities the right to enforce customs, immigration, or sanitary laws at sea within 24 nautical miles from the baseline, doubling the traditional 12-mile width of the contiguous zone. As with the 1988 presidential proclamation, this proclamation did not amend any statutory definitions (as a general matter, a presidential proclamation cannot amend a statute). Thus, for purposes of the Clean Water Act, the territorial sea remains 3 miles wide, and the contiguous zone extends from 3 to 12 miles. Under CERCLA, "navigable waters" means waters of the United States, including the territorial seas (42 U.S.C. §9601(15)), and that law incorporates the Clean Water Act's definitions of "territorial seas" and "contiguous zone" (42 U.S.C. §9601(30)).

The CWA defines the "ocean" as any portion of the high seas beyond the contiguous zone (33 U.S.C. §1362(10)). In contrast, the MPRSA defines "ocean waters" as the open seas lying seaward beyond the baseline from which the territorial sea is measured, as provided for in the Convention of the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone (33 U.S.C. §1402(b)).

Limits of jurisdiction are important because they define the areas where specific laws and rules apply. For example, the Clean Water Act MSD standards apply to sewage discharges from vessels into or upon the navigable waters, and Section 402 NPDES permits are required for point source discharges (excluding vessels) into the navigable waters. Section 311 of the CWA, as amended by the Oil Pollution Act, addresses discharges of oil or hazardous substances into or upon the navigable waters of the United States or the waters of the contiguous zone. Provisions of the Act to Prevent Pollution from Ships (APPS, 33 U.S.C. §§1901-1915) concerning discharges of oil and noxious substances apply to navigable waters. Other provisions of that same act concerning garbage and plastics apply to navigable waters or the EEZ, but the term "navigable waters" is not defined in APPS. The MPRSA regulates ocean dumping within the area extending 12 nautical miles seaward from the baseline and regulates transport of material by U.S.-flagged vessels for dumping into ocean waters.

Further complicating jurisdictional considerations is the fact that the Clean Water Act refers to these distances from shore in terms of miles, without other qualification, which is generally interpreted to mean an international mile or statute mile. APPS, the MPRSA, and the two presidential proclamations refer to distances in terms of nautical miles from the baseline. These two measures are not identical: a nautical mile is a unit of distance used primarily at sea and in aviation; it equals 6,080 feet and is 15% longer than an international or statute mile. 48

In Alaska, where tourism and commercial fisheries are key contributors to the economy, cruise ship pollution has received significant attention. After the state experienced a three-fold increase in the number of cruise ship passengers visits during the 1990s, 49 concern by Alaska Natives and other groups over impacts of cruise ship pollution on marine resources began to increase. In one prominent example of environmental violations, in July 1999, Royal Caribbean Cruise Lines entered a federal criminal plea agreement involving total penalties of $6.5 million for violations in Alaska, including knowingly discharging oil and hazardous substances (including dry-cleaning and photo processing chemicals). The company admitted to a fleet-wide practice of discharging oil-contaminated bilge water. The Alaska penalties were part of a larger $18 million total federal plea agreement involving environmental violations in multiple locations, including Florida, New York, and California.

Public concern about the Royal Caribbean violations led the state to initiate a program in December 1999 to identify cruise ship waste streams. Voluntary sampling of large cruise ships in 2000 indicated that waste treatment systems on most ships did not function well and discharges greatly exceeded applicable U.S. Coast Guard standards for Type II MSDs. Fecal coliform levels sampled during that period averaged 12.8 million colonies per 100 milliliters in blackwater and 1.2 million in graywater, far in excess of the Coast Guard standard of 200 fecal coliforms per 100 milliliters.

Concurrent with growing regional interest in these problems, attention to the Alaska issues led to passage of federal legislation in December 2000 (Certain Alaskan Cruise Ship Operations, Division B, Title XIV of the Miscellaneous Appropriations Bill, H.R. 5666 , in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2001 ( P.L. 106-554 ); 33 U.S.C. § 1901 Note). This law established standards for vessels with 500 or more overnight passengers and generally prohibited discharge of untreated sewage and graywater in navigable waters of the United States within the state of Alaska. It authorized EPA to promulgate standards for sewage and graywater discharges from cruise ships in these waters. Until such time as EPA issues regulations, cruise ships may discharge treated sewage wastes in Alaska waters only while traveling at least 6 knots and while at least 1 nautical mile from shore, provided that the discharge contains no more than 200 fecal coliforms per 100 ml and no more than 150 mg/l total suspended solids (the same limits prescribed in federal regulations for Type II MSDs).

The law also allows for discharges of treated sewage and graywater inside of one mile from shore and at speeds less than 6 knots (thus including stationary discharges while a ship is at anchor) for vessels with systems that can treat sewage and graywater to a much stricter standard. Such vessels must meet these minimum effluent standards: no more than 20 fecal coliforms per 100 ml, no more than 30 mg/l of total suspended solids, and total residual chlorine concentrations not to exceed 10 mg/l. The legislation requires sampling, data collection, and recordkeeping by vessel operators to facilitate Coast Guard oversight and enforcement. The Coast Guard issued regulations to implement the federal law in 2001; the rules became effective immediately upon publication. 50 The regulations stipulate minimum sampling and testing procedures and provide for administrative and criminal penalties for violations of the law, as provided in the legislation.

Pursuant to Title IV, EPA has carried out a multi-year project to evaluate the performance of various treatment systems and to determine whether revised and/or additional standards for sewage and graywater discharges from large cruise ships operating in Alaska are warranted. In particular, EPA sampled wastewater from four cruise ships that operated in Alaska during the summers of 2004 and 2005 to characterize graywater and sewage generated onboard and to evaluate the performance of various treatment systems. 51 Much of the information collected through this effort is summarized in the 2008 Cruise Ship Discharge Assessment Report. Also in 2004, EPA distributed a survey questionnaire on the effectiveness, costs, and impacts of sewage and graywater treatment devices for large cruise vessels in Alaska. EPA has collaborated with the state of Alaska on a cruise ship plume tracking survey (in 2001) and a study in Skagway Harbor to estimate the near-field dilution of treated sewage and graywater discharges from docked cruise ships (in 2008). These sampling efforts generally show that advanced wastewater treatment systems are effective in treating pathogens, oxygen-demanding materials, suspended solids, oil and grease, and particulate matter, and are moderately effective in treating metals, volatile chemicals, and nutrients.

Building on the federal legislation enacted in 2000, the state of Alaska enacted its own law in 2001 (AS 46.03.460-AS 46.03.490). The state law sets standards and sampling requirements for the underway discharge of blackwater in Alaska that are identical to the blackwater/sewage standards in the federal law. However, because of the high fecal coliform counts detected in graywater in 2000, the state law also extends the effluent standards to discharges of graywater. Sampling requirements for all ships took effect in 2001, as did effluent standards for blackwater discharges by large cruise ships (defined as providing overnight accommodations to 250 or more). Effluent standards for graywater discharges by large vessels took effect in 2003. Small ships (defined as providing overnight accommodations for 50 to 249 passengers) were allowed three years to come into compliance with all effluent standards. The law also established a scientific advisory panel to evaluate the effectiveness of the law's implementation and to advise the state on scientific matters related to cruise ship impacts on the Alaskan environment and public health.

According to the state, the federal and state standards have prompted large ships to either install advanced wastewater treatment systems that meet the effluent standards or to manage wastes by holding all of their wastewater for discharge outside of Alaskan waters (beyond 3 miles from shore). 52 As of 2006, 23 of 28 large cruise ships that operated in Alaskan waters had installed advanced wastewater treatment systems, and the quality of wastewater discharged from large ships has improved dramatically, according to the state.

Small ships, however, have not installed new wastewater treatment systems, and the effluent quality has remained relatively constant, with discharge levels for several pollutants regularly exceeding state water quality standards. In particular, test results indicated that concentrations of free chlorine, fecal coliform, copper, and zinc from stationary smaller vessels pose some risk to aquatic life and also to human health in areas where aquatic life is harvested for raw consumption.

In addition to the state's 2001 action, in August 2006 Alaska voters approved a citizen initiative requiring cruise lines to pay the state a $50 head tax for each passenger and a corporate income tax, increasing fines for wastewater violations, and mandating new environmental regulations for cruise ships (such as a state permit for all discharges of treated wastewater). Revenues from the taxes will go to local communities affected by tourism and into public services and facilities used by cruise ships. Supporters of the initiative contend that the cruise industry does not pay enough in taxes to compensate for its environmental harm to the state and for the services it uses. Opponents argued that the initiative would hurt Alaska's competitiveness for tourism, and have filed a legal challenge to the tax in federal court. At least two cruise ship lines (Norwegian Cruise and Royal Caribbean) have reportedly stopped operating cruise ships in Alaskan waters because of the citizen initiative. In 2009, Alaska enacted legislation (HB 134) giving the Department of Environmental Conservation more time to implement the stringent wastewater treatment standards and creating a scientific review board to assess whether the standards can be achieved.

Activity to regulate or prohibit cruise ship discharges also has occurred in several other states.

In April 2004, the state of Maine enacted legislation governing discharges of graywater or mixed blackwater/graywater into coastal waters of the state (Maine LD. 1158). The legislation applies to large cruise ships (with overnight accommodations for 250 or more passengers) and allows such vessels into state waters after January 1, 2006, only if the ships have advanced wastewater treatment systems, comply with discharge and recordkeeping requirements under the federal Alaska cruise ship law, and get a permit from the state Department of Environmental Protection. Under the law, prior to 2006, graywater dischargers were allowed if the ship operated a treatment system conforming to requirements for continuous discharge systems under the Alaska federal and state laws. In addition, the legislation required the state to apply to EPA for designation of up to 50 No Discharge Zones, in order that Maine may gain federal authorization to prohibit blackwater discharges into state waters. EPA approved the state's NDZ request for Casco Bay in June 2006.

California enacted three bills in 2004. One bars cruise ships from discharging treated wastewater while in the state's waters (Calif. A.B. 2672). Another prohibits vessels from releasing graywater (Calif. A.B. 2093), and the third measure prevents cruise ships from operating waste incinerators (Calif. A.B. 471). Additionally, in 2003 California enacted a law that bans passenger ships from discharging sewage sludge and oil bilge water (Calif. A.B. 121), as well as a bill that prohibits vessels from discharging hazardous wastes from photo-processing and dry cleaning operations into state waters (Calif. A.B. 906). Another measure was enacted in 2006: California S.B. 497 requires the state to adopt ballast water performance standards by January 2008 and set specific deadlines for the removal of different types of species from ballast water, mandating that ship operators remove invasive species (including bacteria) by the year 2020.

Several states, including Florida, Washington, and Hawaii, have entered into memoranda of agreement with the industry (through the Cruise Lines International Association and related organizations) providing that cruise ships will adhere to certain practices concerning waste minimization, waste reuse and recycling, and waste management. For example, under a 2001 agreement between industry and the state of Florida, cruise lines must eliminate wastewater discharges in state waters within 4 nautical miles off the coast of Florida, report hazardous waste off-loaded in the United States by each vessel on an annual basis, and submit to environmental inspections by the U.S. Coast Guard.

Similarly, in April 2004 the Washington Department of Ecology, Northwest Cruise Ship Association, and Port of Seattle signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) that would allow cruise ships to discharge wastewater treated with advanced wastewater treatment systems into state waters and would prohibit the discharge of untreated wastewater and sludge. The MOU has been amended several times and now covers other ports, as well. Environmental advocates are generally critical of such voluntary agreements, because they lack enforcement and penalty provisions. States respond that while the Clean Water Act limits a state's ability to control cruise ship discharges, federal law does not bar states from entering into voluntary agreements that have more rigorous requirements. 53 In June 2009, the Department of Ecology reported that cruise ships visiting the state during the 2008 sailing season mostly complied with the MOU to stop discharging untreated wastewater, and found that wastewater treatment systems generally produce high quality effluent that is as good or better than on-land plants. Although enforcement of what is essentially a voluntary agreement is difficult, the state argues that having something in place to protect water quality is beneficial and enables the state to obtain data on vessels and waste treatment equipment. 54

Pressure from environmental advocates, coupled with the industry's strong desire to promote a positive image, have led the cruise ship industry to respond with several initiatives. Members of the Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA), which represents 25 of the world's largest cruise lines, have adopted a set of waste management practices and procedures for their worldwide operations building on regulations of the IMO and U.S. EPA. The guidelines generally require graywater and blackwater to be discharged only while a ship is underway and at least 4 miles from shore and require that hazardous wastes be recycled or disposed of in accordance with applicable laws and regulations. 55

CLIA's cruise line companies also have implemented Safety Management System (SMS) plans for developing enhanced wastewater systems and increased auditing oversight. These SMS plans are certified in accordance with the IMO's International Safety Management Code. The industry also is working with equipment manufacturers and regulators to develop and test technologies in areas such as lower emission turbine engines and ballast water management for elimination of non-native species. Environmental groups commend industry for voluntarily adopting improved management practices but also believe that enforceable standards are preferable to voluntary standards, no matter how well intentioned. 56