- Search Please fill out this field.

- Manage Your Subscription

- Give a Gift Subscription

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

- Travel Tips

What Travel Looked Like Through the Decades

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/maya-kachroo-levine-author-pic-1-2000-1209fcfd315444719a7906644a920183.jpg)

Getting from point A to point B has not always been as easy as online booking, Global Entry , and Uber. It was a surprisingly recent event when the average American traded in the old horse-and-carriage look for a car, plane, or even private jet .

What was it like to travel at the turn of the century? If you were heading out for a trans-Atlantic trip at the very beginning of the 20th century, there was one option: boat. Travelers planning a cross-country trip had something akin to options: carriage, car (for those who could afford one), rail, or electric trolley lines — especially as people moved from rural areas to cities.

At the beginning of the 1900s, leisure travel in general was something experienced exclusively by the wealthy and elite population. In the early-to-mid-20th century, trains were steadily a popular way to get around, as were cars. The debut regional airlines welcomed their first passengers in the 1920s, but the airline business didn't see its boom until several decades later. During the '50s, a huge portion of the American population purchased a set of wheels, giving them the opportunity to hit the open road and live the American dream.

Come 1960, airports had expanded globally to provide both international and domestic flights to passengers. Air travel became a luxury industry, and a transcontinental trip soon became nothing but a short journey.

So, what's next? The leisure travel industry has quite a legacy to fulfill — fancy a trip up to Mars , anyone? Here, we've outlined how travel (and specifically, transportation) has evolved over every decade of the 20th and 21st centuries.

The 1900s was all about that horse-and-carriage travel life. Horse-drawn carriages were the most popular mode of transport, as it was before cars came onto the scene. In fact, roadways were not plentiful in the 1900s, so most travelers would follow the waterways (primarily rivers) to reach their destinations. The 1900s is the last decade before the canals, roads, and railway plans really took hold in the U.S., and as such, it represents a much slower and antiquated form of travel than the traditions we associate with the rest of the 20th century.

Cross-continental travel became more prevalent in the 1910s as ocean liners surged in popularity. In the '10s, sailing via steam ship was the only way to get to Europe. The most famous ocean liner of this decade, of course, was the Titanic. The largest ship in service at the time of its 1912 sailing, the Titanic departed Southampton, England on April 10 (for its maiden voyage) and was due to arrive in New York City on April 17. At 11:40 p.m. on the evening of April 14, it collided with an iceberg and sank beneath the North Atlantic three hours later. Still, when the Titanic was constructed, it was the largest human-made moving object on the planet and the pinnacle of '10s travel.

The roaring '20s really opened our eyes up to the romance and excitement of travel. Railroads in the U.S. were expanded in World War II, and travelers were encouraged to hop on the train to visit out-of-state resorts. It was also a decade of prosperity and economic growth, and the first time middle-class families could afford one of the most crucial travel luxuries: a car. In Europe, luxury trains were having a '20s moment coming off the design glamour of La Belle Epoque, even though high-end train travel dates back to the mid-1800s when George Pullman introduced the concept of private train cars.

Finally, ocean liners bounced back after the challenges of 1912 with such popularity that the Suez Canal had to be expanded. Most notably, travelers would cruise to destinations like Jamaica and the Bahamas.

Cue "Jet Airliner" because we've made it to the '30s, which is when planes showed up on the mainstream travel scene. While the airplane was invented in 1903 by the Wright brothers, and commercial air travel was possible in the '20s, flying was quite a cramped, turbulent experience, and reserved only for the richest members of society. Flying in the 1930s (while still only for elite, business travelers) was slightly more comfortable. Flight cabins got bigger — and seats were plush, sometimes resembling living room furniture.

In 1935, the invention of the Douglas DC-3 changed the game — it was a commercial airliner that was larger, more comfortable, and faster than anything travelers had seen previously. Use of the Douglas DC-3 was picked up by Delta, TWA, American, and United. The '30s was also the first decade that saw trans-Atlantic flights. Pan American Airways led the charge on flying passengers across the Atlantic, beginning commercial flights across the pond in 1939.

1940s & 1950s

Road trip heyday was in full swing in the '40s, as cars got better and better. From convertibles to well-made family station wagons, cars were getting bigger, higher-tech, and more luxurious. Increased comfort in the car allowed for longer road trips, so it was only fitting that the 1950s brought a major expansion in U.S. highway opportunities.

The 1950s brought the Interstate system, introduced by President Eisenhower. Prior to the origination of the "I" routes, road trippers could take only the Lincoln Highway across the country (it ran all the way from NYC to San Francisco). But the Lincoln Highway wasn't exactly a smooth ride — parts of it were unpaved — and that's one of the reasons the Interstate system came to be. President Eisenhower felt great pressure from his constituents to improve the roadways, and he obliged in the '50s, paving the way for smoother road trips and commutes.

The '60s is the Concorde plane era. Enthusiasm for supersonic flight surged in the '60s when France and Britain banded together and announced that they would attempt to make the first supersonic aircraft, which they called Concorde. The Concorde was iconic because of what it represented, forging a path into the future of aviation with supersonic capabilities. France and Britain began building a supersonic jetliner in 1962, it was presented to the public in 1967, and it took its maiden voyage in 1969. However, because of noise complaints from the public, enthusiasm for the Concorde was quickly curbed. Only 20 were made, and only 14 were used for commercial airline purposes on Air France and British Airways. While they were retired in 2003, there is still fervent interest in supersonic jets nearly 20 years later.

Amtrak incorporated in 1971 and much of this decade was spent solidifying its brand and its place within American travel. Amtrak initially serviced 43 states (and Washington D.C.) with 21 routes. In the early '70s, Amtrak established railway stations and expanded to Canada. The Amtrak was meant to dissuade car usage, especially when commuting. But it wasn't until 1975, when Amtrak introduced a fleet of Pullman-Standard Company Superliner cars, that it was regarded as a long-distance travel option. The 235 new cars — which cost $313 million — featured overnight cabins, and dining and lounge cars.

The '80s are when long-distance travel via flight unequivocally became the norm. While the '60s and '70s saw the friendly skies become mainstream, to a certain extent, there was still a portion of the population that saw it as a risk or a luxury to be a high-flyer. Jetsetting became commonplace later than you might think, but by the '80s, it was the long-haul go-to mode of transportation.

1990s & 2000s

Plans for getting hybrid vehicles on the road began to take shape in the '90s. The Toyota Prius (a gas-electric hybrid) was introduced to the streets of Japan in 1997 and took hold outside Japan in 2001. Toyota had sold 1 million Priuses around the world by 2007. The hybrid trend that we saw from '97 to '07 paved the way for the success of Teslas, chargeable BMWs, and the electric car adoption we've now seen around the world. It's been impactful not only for the road trippers but for the average American commuter.

If we're still cueing songs up here, let's go ahead and throw on "Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous," because the 2010s are when air travel became positively over-the-top. Qatar Airways rolled out their lavish Qsuites in 2017. Business class-only airlines like La Compagnie (founded in 2013) showed up on the scene. The '10s taught the luxury traveler that private jets weren't the only way to fly in exceptional style.

Of course, we can't really say what the 2020 transportation fixation will be — but the stage has certainly been set for this to be the decade of commercial space travel. With Elon Musk building an elaborate SpaceX rocket ship and making big plans to venture to Mars, and of course, the world's first space hotel set to open in 2027 , it certainly seems like commercialized space travel is where we're headed next.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Ellie-Nan-Storck-00d7064c4ef24a22a8900f0416c31833.jpeg)

Related Articles

The History of Transportation

Aaron Foster / Getty Images

- Invention Timelines

- Famous Inventions

- Famous Inventors

- Patents & Trademarks

- Computers & The Internet

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

Whether by land or by sea, humans have always sought to traverse the earth and move to new locations. The evolution of transportation has brought us from simple canoes to space travel, and there's no telling where we could go next and how we will get there. The following is a brief history of transportation, dating from the first vehicles 900,000 years ago to modern-day times.

Early Boats

The first mode of transportation was created in the effort to traverse water: boats. Those who colonized Australia roughly 60,000–40,000 years ago have been credited as the first people to cross the sea, though there is some evidence that seafaring trips were carried out as far back as 900,000 years ago.

The earliest known boats were simple logboats, also referred to as dugouts, which were made by hollowing out a tree trunk. Evidence for these floating vehicles comes from artifacts that date back to around 10,000–7,000 years ago. The Pesse canoe—a logboat—is the oldest boat unearthed and dates as far back as 7600 BCE. Rafts have been around nearly as long, with artifacts showing them in use for at least 8,000 years.

Horses and Wheeled Vehicles

Next, came horses. While it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly when humans first began domesticating them as a means of getting around and transporting goods, experts generally go by the emergence of certain human biological and cultural markers that indicate when such practices started to take place.

Based on changes in teeth records, butchering activities, shifts in settlement patterns, and historic depictions, experts believe that domestication took place around 4000 BCE. Genetic evidence from horses, including changes in musculature and cognitive function, support this.

It was also roughly around this period that the wheel was invented. Archaeological records show that the first wheeled vehicles were in use around 3500 BCE, with evidence of the existence of such contraptions found in Mesopotamia, the Northern Caucuses, and Central Europe. The earliest well-dated artifact from that time period is the "Bronocice pot," a ceramic vase that depicts a four-wheeled wagon that featured two axles. It was unearthed in southern Poland.

Steam Engines

In 1769, the Watt steam engine changed everything. Boats were among the first to take advantage of steam-generated power; in 1783, a French inventor by the name of Claude de Jouffroy built the "Pyroscaphe," the world’s first steamship . But despite successfully making trips up and down the river and carrying passengers as part of a demonstration, there wasn’t enough interest to fund further development.

While other inventors tried to make steamships that were practical enough for mass transport, it was American Robert Fulton who furthered the technology to where it was commercially viable. In 1807, the Clermont completed a 150-mile trip from New York City to Albany that took 32 hours, with the average speed clocking in at about five miles per hour. Within a few years, Fulton and company would offer regular passenger and freight service between New Orleans, Louisiana, and Natchez, Mississippi.

Back in 1769, another Frenchman named Nicolas Joseph Cugnot attempted to adapt steam engine technology to a road vehicle—the result was the invention of the first automobile . However, the heavy engine added so much weight to the vehicle that it wasn't practical. It had a top speed of 2.5 miles per hour.

Another effort to repurpose the steam engine for a different means of personal transport resulted in the "Roper Steam Velocipede." Developed in 1867, the two-wheeled steam-powered bicycle is considered by many historians to be the world’s first motorcycle .

Locomotives

One mode of land transport powered by a steam engine that did go mainstream was the locomotive. In 1801, British inventor Richard Trevithick unveiled the world’s first road locomotive—called the “Puffing Devil”—and used it to give six passengers a ride to a nearby village. It was three years later that Trevithick first demonstrated a locomotive that ran on rails, and another one that hauled 10 tons of iron to the community of Penydarren, Wales, to a small village called Abercynon.

It took a fellow Brit—a civil and mechanical engineer named George Stephenson—to turn locomotives into a form of mass transport. In 1812, Matthew Murray of Holbeck designed and built the first commercially successful steam locomotive, “The Salamanca,” and Stephenson wanted to take the technology a step further. So in 1814, Stephenson designed the "Blücher," an eight-wagon locomotive capable of hauling 30 tons of coal uphill at a speed of four miles per hour.

By 1824, Stephenson improved the efficiency of his locomotive designs to where he was commissioned by the Stockton and Darlington Railway to build the first steam locomotive to carry passengers on a public rail line, the aptly named "Locomotion No. 1." Six years later, he opened the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, the first public inter-city railway line serviced by steam locomotives. His notable accomplishments also include establishing the standard for rail spacing for most of the railways in use today. No wonder he’s been hailed as " Father of Railways ."

Technically speaking, the first navigable submarine was invented in 1620 by Dutchman Cornelis Drebbel. Built for the English Royal Navy, Drebbel’s submarine could stay submerged for up to three hours and was propelled by oars. However, the submarine was never used in combat, and it wasn’t until the turn of the 20th century that designs leading to practical and widely used submersible vehicles were realized.

Along the way, there were important milestones such as the launch of the hand-powered, egg-shaped "Turtle " in 1776, the first military submarine used in combat. There was also the French Navy submarine "Plongeur," the first mechanically powered submarine.

Finally, in 1888, the Spanish Navy launched the "Peral," the first electric, battery-powered submarine, which also so happened to be the first fully capable military submarine. Built by a Spanish engineer and sailor named Isaac Peral, it was equipped with a torpedo tube, two torpedoes, an air regeneration system, and the first fully reliable underwater navigation system, and it posted an underwater speed of 3.5 miles per hour.

The start of the twentieth century was truly the dawn of a new era in the history of transportation as two American brothers, Orville and Wilbur Wright, pulled off the first official powered flight in 1903. In essence, they invented the world’s first airplane. Transport via aircraft took off from there with airplanes being put into service within a few short years during World War I. In 1919, British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Brown completed the first transatlantic flight, crossing from Canada to Ireland. The same year, passengers were able to fly internationally for the first time.

Around the same time that the Wright brothers were taking flight, French inventor Paul Cornu started developing a rotorcraft. And on November 13, 1907, his "Cornu" helicopter, made of little more than some tubing, an engine, and rotary wings, achieved a lift height of about one foot while staying airborne for about 20 seconds. With that, Cornu would lay claim to having piloted the first helicopter flight .

Spacecraft and the Space Race

It didn’t take long after air travel took off for humans to start seriously considering the possibility of going further up and toward the heavens. The Soviet Union surprised much of the western world in 1957 with its successful launch of Sputnik, the first satellite to reach outer space. Four years later, the Russians followed that by sending the first human, pilot Yuri Gagaran, into outer space aboard the Vostok 1.

These achievements would spark a “space race” between the Soviet Union and the United States that culminated in the Americans taking what was perhaps the biggest victory lap among national rivals. On July 20, 1969, the lunar module of the Apollo spacecraft, carrying astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, touched down on the surface of the moon.

The event, which was broadcast on live TV to the rest of the world, allowed millions to witness the moment Armstrong became the first man to ever step foot on the moon, a moment he heralded as “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

- The History of Railroad Technology

- The History of Steamboats

- The History of Steam-Powered Cars

- George Stephenson and the Invention of the Steam Locomotive Engine

- 19th Century Locomotive History

- Biography of Robert Fulton, Inventor of the Steamboat

- How Do Steam Engines Work?

- The Origins of the Term, 'Horsepower'

- The Railways in the Industrial Revolution

- Great Father-Son Inventor Duos

- The History of the Tom Thumb Steam Engine and Peter Cooper

- Trains Coloring Book

- A History of the Automobile

- The Most Impactful Inventions of the Last 300 Years

- The Most Important Inventions of the 19th Century

- The History of Electric Vehicles Began in 1830

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

Tourism and Transport

Jessica Lynne Pearson is associate professor of history at Macalester College in Saint Paul, Minnesota. She is the author of The Colonial Politics of Global Health (Harvard, 2018) and the co-editor of The United Nations and Decolonization (Routledge, 2020).

- Published: 18 August 2022

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Transportation for tourists is inextricably linked to broader power structures in modern global society. Histories of empire building, nationalism, and decolonization overlap with histories of sea, highway, rail, and air travel, demonstrating the roles that transport has played in building and dismantling systems of inequality on a global scale. Tourism plays a key role in forging collective identities, but leisure travel, historically, was beyond the reach of all but the most privileged groups. Revolutions in transportation—in step with broader political and social shifts—have contributed to the slow but ongoing democratization of travel. Tourist transport in the second half of the twentieth century became a key site in the battle for desegregation and served as a platform for recently decolonized nations to pursue political independence and economic autonomy from their former colonizers.

In 1984, Society Expeditions—a Seattle-based tour company—invited travelers to “experience European travel at its grandest” by embarking on a ten-day journey aboard the “Nostalgic Istanbul Orient Express.” Reintroduced in 1982, the train comprised “beautifully restored and sumptuously appointed antique cars,” and would follow the famed train’s historic route. According to the company’s promotional brochure, the original Orient Express, “following its maiden journey in 1883 … carried diplomats, royalty, smugglers and spies across Europe—from sophisticated Paris to Istanbul, the very portal of the Orient.” Tourists who traveled in the 1980s on the reimagined Orient Express would have the opportunity to “both relive and to create history on the world’s most fabulous train.” 1

The Orient Express—made famous by Agatha Christie, James Bond, and Dracula —looms large in the popular imagination of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century train travel. 2 While the Orient Express did not make its final trans-European journey until 1977, the train had long since lost its reputation as Europe’s most luxurious form of tourist transport. 3 In a pithy 1969 New York Times headline, Drew Middleton reported: “ORIENT EXPRESS: NOBODY VANISHES. Now-Seedy Train a Setting of Many Suspense Novels.” While Agatha Christie’s protagonists sipped champagne and brandished daggers, Middleton’s journey was charmingly mundane: “Car No. 6 was labeled Orient Express. A snowstorm blurred the lights at the Gare de Lyon in Paris. But no dark, exotic beauty with a tiny, pearl-handled pistol … appeared out of the night. … Only a plump Frenchwoman in Compartment 80 complaining loudly that a zipper was stuck and that her husband, who was trying to get it unstuck, was little short of a fool.” 4

Transportation, at the most basic level, facilitates tourism by allowing people to move from one place to another. Yet whether that journey is as action-packed as that of Hercule Poirot—Christie’s detective—or as humdrum as Middleton’s, a tourist’s experience is indelibly marked by the type (or types) of transportation they use. Tourist transport, however, does more than shape individual travel experiences. Deeply embedded in intersecting networks of power, it has also been wielded as both a weapon of domination and as a tool of resistance. The expanding fields of transport history, tourism history, and mobility studies unpack the intersections between modes of transportation, leisure travel, and a broad range of power dynamics. 5 Collectively, this work engages a set of interconnected questions: How did technological innovation fundamentally alter tourist trajectories as travelers made their way through the world via new forms of transportation? In what ways did different modes of transportation facilitate different travel experiences for people from a diverse range of identities and backgrounds? And finally, how were those modes of travel bound up in colonial conquest, nation-building, and the global battle against imperialism, racism, and economic oppression?

Rather than understanding transport as simply a means to get from point A to point B, historians have sought to interrogate the ways that humans have experienced mobility and its connections to broader historical processes. Physical movement facilitated empire building, the imagining of national communities, and, most recently, anticolonial and antiracist movements. 6 Leisure-as-mobility played a critical role in each of these phenomena. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, for example, European colonizers used transportation networks to “civilize” their colonial territories, opening up those spaces to white tourists by allowing them to stake their own claim over lands and cultures that belonged to other people. 7 In the era of decolonization, the creation of new roads, train lines, and national airlines became a hallmark of political and economic independence from those colonizers. 8 While leisure tourism was once limited to wealthy white travelers, the expanding range of transportation options played a critical role in democratizing travel and opening up touring opportunities to the middle and working classes from all backgrounds. Despite the considerable progress made in democratizing, desegregating, and “decolonizing” the airways, railways, and highways, however, inequality still governs tourist transport in powerful ways. These dynamics illuminate the role that tourism played in forging collective identities and they demonstrate how the movement of tourists fueled both the creation and dismantling of power structures in the last two centuries.

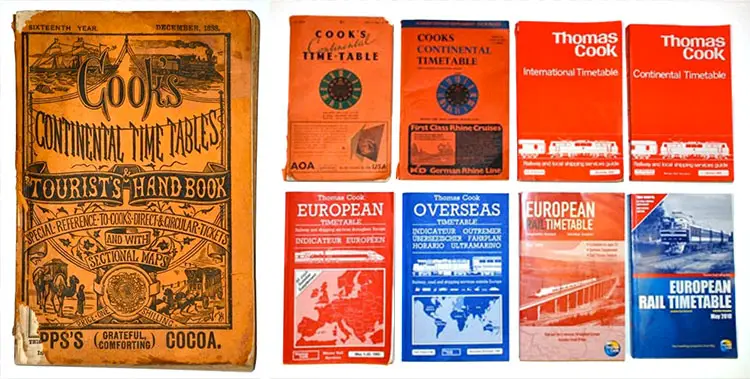

Tourists Test the Waters

Before the age of the railway, the automobile, or the jet, travel by boat was one of the few transportation options available to travelers hoping to make a long-distance journey. Indeed, the first “modern” tourists, according to historians of travel, were young Englishmen who crossed the channel in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. 9 Steam technology in the early 1800s fueled tourists across lakes and down rivers, and the growing popularity of destinations such as Egypt, New Orleans, Niagara Falls, and Margate, England reflected the impact of this technological advancement. 10 The Nile steamship tour quickly became a cornerstone of Thomas Cook and Son’s offerings in the 1890s. 11 By the early twentieth century the company encouraged steamship travel for tourists from the United States, Canada, and South America who wished to tour Japan. 12 While historians tend to attribute the birth of mass tourism to the invention of the railway, John Armstrong and David M. Williams have shown that we can, in fact, thank steamships for the emergence of popular overseas leisure travel, beginning with service on the Clyde in 1812. 13

As other modes of transport (train, automobile, airplane) evolved and became more accessible in the first half of the twentieth century, travel by sea or river became a leisure activity in and of itself. No longer the quickest or most efficient means of seeing the world, steamship companies and cruise lines emphasized the unique experience of travel by boat. 14 In 1951, for example, Cook’s World Travel Service published a brochure hailing the return of leisure at sea: “It is good to have the comforting feel of a white deck beneath your feet … to look out over a sun-lit blue water, to experience that thrill of anticipation when, in the sudden silence of quieted engines, your ship slides smoothly into the next port of call.” Rather than promoting a new mode of transport, Cook’s brochure proposed a return to a simpler era, which would be “welcome especially to those who knew its delights in pre-war days.” Sea travel, it argued, responded to the “ageless appeal of roving the world,” but, unlike in earlier eras, the possible destinations were limitless. 15

The nostalgic allure of steam travel persists. As recently as the 2000s and 2010s, the reinvigoration of steamboat tourism on the Mississippi, for example, has signaled both a literal and a metaphorical recovery from the ravages Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. In 2019, the New Orleans Steamboat Company relaunched its riverboat tours, indicating a kind of return to normalcy for one of the US South’s most important tourist destinations. One newspaper article explained that “few experiences capture old New Orleans and the Mississippi River quite like a paddlewheel riverboat coming round the muddy bend with its tooting whistle horn, towering smoke stacks and water-churning propeller.” The rehabilitation of the Natchez speaks to a broader process of rebuilding and represents, for many travelers, the ability to reconnect with simpler times. 16

Yet the marketing of maritime tourism as a more carefree mode of vacation travel belies the often-unpredictable nature of water transport. It also obscures the opportunities that this mode of transit historically offered as a space to challenge existing social norms and political structures. As Kris Alexanderson shows in the case of maritime travel within the Dutch empire, for example, transoceanic mobility allowed Indonesians to subvert European hierarchies and build anticolonial networks. Although passenger liners for tourists were designed to function as “colonial classrooms,” Dutch officials found that hierarchies that were enforceable on land frequently proved difficult to maintain in the more flexible space of the sea. 17

While maritime travel enjoyed an initial popularity as the default mode of international transportation, in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries steamers and cruise lines pivoted to promoting travel by river or sea as a form of luxury or nostalgia tourism as more travel options became available. Yet while this form of travel has reified both class and racial hierarchies and furthered cement existing narratives (such as those associated with steamboat travel on the Mississippi), a closer examination of the history of water travel also reveals the potential for subversion and resistance, as Alexanderson demonstrates in the case of the Dutch mails.

Inequality on the Railways

While the invention of the steamship drastically reduced travel times for vacationers making their way by water, the railway revolutionized previously held notions of both time and space on land for those who were able to access this form of travel. Prior to the invention of the train, remarks historian Christian Wolmar, “no-one had ever gone faster than a horse could gallop.” Trains transformed the way people understood the most central facets of everyday life: work, marriage, housing, even their sense of national identity. 18 The expansion of railway networks also fundamentally changed how people conceived of leisure by connecting them to previously unreachable destinations while simultaneously offering a new way of viewing the world. 19 The first railway, the Liverpool and Manchester Line, launched its services in 1830. Railway networks expanded first in Western Europe, Russia, and the United States, and developed later in Asia, South America, and Africa. In each of these locations, railway construction played a critical role in both empire- and nation-building, drawing invariably on the labor of Black people, Indigenous people, and people of color, often in conjunction with the forced acquisition of Indigenous lands. 20

Although it was reserved for those travelers who enjoyed at least a degree of white or colonial privilege, early rail travel was, by and large, a fairly uncomfortable endeavor. 21 For the wealthiest first-class passengers, however, train travel could be a particularly luxurious means of getting from place to place, as well as a tourist experience in itself. Travelers aboard a Pullman Company train, for example, experienced “perfected passenger service,” according to a 1931 Pullman brochure. The pamphlet recounted the travel experience of “Mr. Brown,” who travels from Yuma, Arizona, to Portland, Maine, with stopovers in Washington and New York. En route, Mr. Brown relishes the range of comforts available on board: “good meals, bed, morning bath, clothes pressed at night; shaved by the train barber.” He “enjoys the scenery from the observation car by day, spends the evening reading in the club car.” The Pullman train, in other words, was a first-class “hotel on wheels.” 22

For travelers of color throughout much of the world, train transport remained deeply enmeshed in broader networks of racial inequality. In South Africa, for example, railway segregation had a long and sordid history that predates the official government policy of apartheid by several decades. 23 In many parts of the world, moreover, railway construction spearheaded by European companies relied heavily on undercompensated (or uncompensated) labor of local workers, including many who lived under colonial rule. 24 The history of Indigenous labor exploitation in the construction of the Dakar-Niger railway line, for example, was memorialized by Senegalese writer and filmmaker Ousmane Sembène in his 1960 novel God’s Bits of Wood . 25

Ultimately, these sites of inequality came to serve as critical nodes of resistance to racism and colonialism. Railway worker strikes, campaigns to desegregate rail travel, and efforts to promote heritage train travel to tourists of color all constituted acts of resistance against racism and other forms of discrimination. 26 As Tammy S. Gordon shows, for example, Amtrak encouraged African American travelers in the 1970s to “Take Amtrak to Black History” and promoted their racially integrated train service through advertisements in African American magazines. By traveling the company’s rail lines, Amtrak claimed, African Americans could experience a range of key landmarks in Black history, from Frederick Douglass’s home in Washington, DC, to the New York Public Library in Albany, where a preliminary draft of the Emancipation Proclamation was on public display. Amtrak’s embrace of African American heritage tourists, Gordon argues, reflected a moment when African Americans were increasingly able to “[assert] their power as consumers of travel,” defying the notion that touring was an activity open only to white travelers. 27 As a result of their intimate relationship to myriad forms of inequality, railways have often served as sites of mobilization against social, political, and economic injustice.

Individualism on the Road

Whereas steamships, riverboats, and trains allowed tourists to travel to new destinations en masse, cars enabled travelers to cultivate a sense of individuality as they sketched their own itineraries and set their own timetables. The rise of automobile tourism, according to Orvar Löfgren, afforded these travelers both “freedom and speed.” The trip itself could be an “adventure,” Löfgren argues, “just hitting the road, exploring new settings.” 28 Car camping added a further layer of excitement to these journeys, becoming immensely popular first in the United States in the 1920s and 1930s and then in Europe in the 1950s and 1960s. 29 While some automobile tourists opted to spend the night in tents, others sought accommodation at the growing range of affordable highway motels. 30 By opening up travel to a wider range of budgets, automobiles played an important role in the slow and uneven democratization of vacationing while still preserving other hierarchies connected to race, class, gender, and geography.

Tourist travel by car also expanded the number of destinations that some travelers were able to visit. Small towns, rural areas, parks, and nature preserves saw an opportunity to market themselves as new destinations for travelers. The Wyoming Travel Commission, for example, issued a series of brochures aimed specifically at automobile tourists. Touting an “infinite medley of scenic attractions, historic sites and amazing geological formations,” the brochures encouraged travelers to visit not only Yellowstone National Park, but also sites associated with the state’s cattle and mining industries or with the history of the Oregon Trail. 31 Efforts to promote automobile tourism, of course, were not limited to the United States. In 1969, Hertz Rent-A-Car teamed up with Air France and Gourmet Magazine to offer a series of “Gourmet Holidays: Wine Tours of France by Rented Car.” Glossing over the dangers of combining self-guided automobile travel with twenty-one back-to-back days of wine tasting, Hertz’s guidebook assured would-be tourists that automobile travel would give them unparalleled access to France’s most prized wines and picturesque sites, including those not reachable by train or airplane. “In your Hertz car you explore the France missed by most tourists,” the guide boasted, “yours to leisurely explore are quaint medieval villages, vineyards as old as France itself, Renaissance cities, historic churches and cathedrals and museums crammed with treasures.” 32 The automobile, in other words, offered a kind of unfettered access that could not be achieved by any other mode of transport.

Throughout the late nineteenth and the twentieth centuries, the construction of highways and scenic roads in the United States and US territories played an important role in generating tourist traffic. The expanding tourism industry, in turn, produced an ongoing demand for well-maintained infrastructure and better road access. In some locales, the construction of scenic byways even predated the invention of the motorcar. In late nineteenth-century Hawaii—a decade prior to its formal annexation by the United States—Hawaiian Kingdom minister of the interior Lorrin A. Thurston embarked on a massive road-building program. The initial plan aimed to transform horse trails into paths that would be accessible for carriages and wagons, and Thurston’s successors would further transform them into roads that could be traveled by motor vehicles. These roads, historian Dawn Duensing explains, were specifically intended to attract wealthy tourists, with the goal of boosting the local economy. 33

While some projects were undertaken on a more local level, in other contexts national governments played a critical role in promoting automobile tourism through road building. 34 In the interwar United States, argues historian Christopher Wells, the National Parks Service “remade the national parks into recreational wonderlands designed first and foremost to be engaged from the seats of automobiles.” 35 While new highways opened up tourism opportunities for more privileged travelers, for others they meant the decimation of local communities and livelihoods. The Rondo neighborhood, in Saint Paul, Minnesota, to give one example, was one of many African American communities displaced by the construction of new roadways. 36

Although many automobile tourism initiatives focused on encouraging travelers to get to know a particular country, this mode of travel was, in fact, not limited by national frontiers. Indeed, many highway-building projects worked to foster cross-border exchange alongside new guidebooks that encouraged travelers to visit new nations simply by hitting the road. In 1953, for example, the American Automobile Association published a guidebook entitled Motoring in Central and South America , which provided advice for travelers hoping to navigate the Pan-American Highway, still under construction at the time. 37 Today, the only break in this nineteen-thousand-mile network of highways is at the Darién Gap, where dense rainforest makes passage by car impossible. 38 In 1953, the journey would have been remarkably more perilous. Beyond the “four distinct breaks in the highway system” that necessitated sending one’s automobile on by steamer, the guide also noted that while the route was used frequently by locals in South America, because of the steep inclines and abrupt changes in elevation, “it is not yet to be considered in the realm of carefree tourist travel as we know it.” For those wishing to take the highway beyond Mexico, the guide recommended “time, funds, a good sound car (and spare parts), a knowledge of Spanish, a sense of humor, and a definite spirit of adventure.” 39 For some travelers, however, it would take more than a sense of adventure to make car travel a safe and accessible form of vacationing, and guidebooks like this one often obfuscated the ongoing inequalities that governed the road.

The Green Book : Combating Racism en Route

Although expanding road networks and the growing affordability of cars democratized travel significantly, automobile tourism was not equally open to all travelers. Indeed, automobility was conditioned by inequalities and violence connected to hierarchies of class, race, and gender, and was also deeply implicated in systems of settler colonialism. Car travel, for example, opened up a wide range of tourist experiences that appropriated Native American history and culture, explains historian Katrina Phillips. 40 But when Native Americans themselves took to the road, argues Philip Deloria, non-Natives reacted with disbelief or even suspicion. 41 In the American South, Jim Crow laws prevented African Americans traveling by car from seeking meals or accommodations in many roadside establishments.

Victor Hugo Green’s Negro Motorist Green Book , often simply referred to as the Green Book , worked to make travel safer and more accessible for African Americans by helping them identify hotels, restaurants, service stations, shops, and theaters where they would be welcome. 42 First published in 1936, the Green Book began as a guide for automobile travelers in Green’s home state of New York. Over the course of three decades, its coverage expanded to encompass not only the continental United States, but also destinations in Africa, Canada, the Caribbean, Europe, and Latin America. While some places were more open to travelers of diverse identities, in other locations vacationers of color confronted many of the same discriminatory practices that they encountered in the United States. Bermuda, for example, was a particularly unwelcoming destination for tourists of color since Bermudian hotels and restaurants that discriminated against nonwhite travelers were protected by a law entitled “The Hotel Keepers’ Protection Act,” passed in 1930. 43

Green’s efforts to open up automobile tourism to African Americans in the United States helped them to take part in a “nationalist enterprise,” contends historian Myra B. Young Armstead, by facilitating their participation “in the growing national preoccupation with motoring for pleasure.” 44 Drawing on the work of historian Lizabeth Cohen, Young Armstead argues that for African Americans after World War II, tourism was a highly politicized form of consumption, a means of defying racist assumptions about who had the right to participate in leisure and who could access public spaces. 45 Indeed, Green’s guide was not just a listing of safe places for Black travelers to stop en route. It was also a manifesto about the right to mobility. In 1948, the guide’s expanded introduction stated that “there will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go wherever we please.” 46

Green, unfortunately, did not live to see the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The guidebook he created, however, celebrated this monumental accomplishment. According to the Green Book ’s final edition, published in 1966, “Most people who ‘go on holiday’ … are seeking someplace that offers them rest, relaxation and a refuge from the cares and worries of the work-a-day world. The Negro traveler … is no exception. He, too, is looking for ‘Vacation without Aggravation.’” This edition’s preface, entitled “Civil Rights: Facts vs. Fiction,” stated clearly and succinctly that all travelers were now entitled to the right to such a vacation: “Effective at once, every hotel, restaurant, theater or other facility catering to the general public must do exactly that.” 47

Despite the monumental gains made by the 1964 Civil Rights Act, automobility in the United States remains limited by ongoing racism, evidenced by a 2020 New York Times headline that bluntly stated: “2020 Is the Summer of the Road Trip. Unless You’re Black.” 48 And while in some sense these contours, nuances, and legacies of the “Jim Crow” system make it a specifically American phenomenon, racism on the road was (and is) also not limited to the United States. As Megan Brown, for example, shows in the case of the Rallye Méditerranée-le Cap, participants in this transcontinental car race across the African continent were predominantly white Europeans, while Africans were relegated to the position of onlookers or support staff. 49 In postcolonial Africa, automobility has been a source of liberation that continues to be circumscribed by state instability and global economic inequality, as Jennifer Hart demonstrates in her study of car travel in twentieth- and twenty-first-century Ghana. 50 Automobiles, like other forms of tourist transport, remain caught between their revolutionary potential and the role they have played in keeping traditional hierarchies anchored firmly in place.

Leisure in the Air

As some travelers were motoring across the Sahara or winding their way through Yellowstone National Park in the family station wagon, others were taking to the skies using aerial routes that were—like their terrestrial counterparts—intimately linked to global systems of class and race privilege. In the interwar period, the United States dominated foreign competitors in the air travel industry. By the late 1920s, the number of travelers using US airlines was higher than the collective passenger count of their French, British, Dutch, and Italian competitors combined. As historian Jenifer Van Vleck argues, “American ascendancy” in the air was attributable to a range of factors, including the relative strength of the post–World War I American economy, government investment in national airlines, and the accomplishments of American aviators like Charles Lindbergh. 51 By the 1930s and early 1940s, international air travel aboard one of Pan Am’s “Clippers” had become the quintessence of luxurious lifestyle. 52 Although the ability to travel by flight remained limited to an elite class of tourists and business travelers, what historian Gordon Pirie calls “airmindedness,” or the “mass public awareness of powered flight” gripped the popular imagination. 53

Air travel pioneers made significant technological advancements in the first decades of the twentieth century, but it would not be until the late 1940s and 1950s that air travel would become a relatively accessible mode of tourist transport. 54 In the age of jet travel, beginning in the 1950s, far-flung destinations that had once required several weeks of travel by sea could now be reached within a matter of hours. During this period, the United States saw growing competition from French, British, and Soviet airlines. In 1922, for example, the French airline companies that would eventually rally under the banner of “Air France” collectively transported only 9,502 passengers. Twenty-five years later, in 1947, the annual passenger count of Air France had reached 422,845. In 1963, nearly 3.5 million passengers made a journey on one of Air France’s flights. 55 For European empires, the expansion of commercial air travel would play a critical role in linking the metropole to colonial spaces across the globe. Airplanes facilitated not only the growth of the colonial tourism industry, but other economic exchanges as well. 56

The Cold War and the emergence of the military-industrial complex in the United States prompted further developments in both aircraft technology and fare structures, putting international air travel within the reach of the upper middle class for the first time in history and cementing American hegemony in the air. In the 1950s, US airlines began to enthusiastically promote vacations in Western Europe. France, especially, became a favorite Cold War travel destination. 57 According to Air France’s in-flight magazine, France’s growing popularity was thanks not only to the world renown of la qualité française (French quality), but also to France’s position as a “jumping off point” for vacations in nearby countries, where even an “impenetrable curtain” had failed to stop the flow of “tourist curiosity.” 58

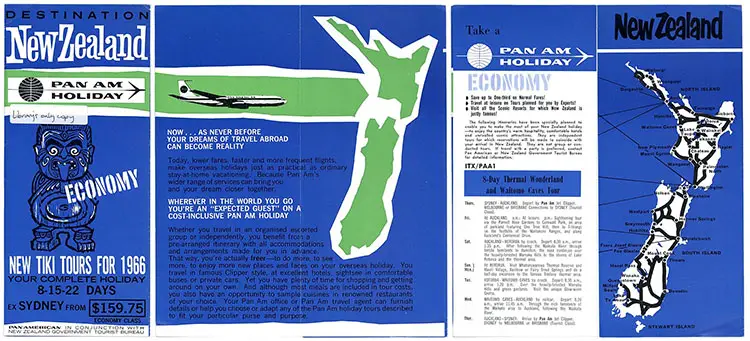

New jet technology cut flying time drastically. In the early 1950s, Britain’s de Havilland, Vickers, and Britannia led the way in commercial jet production, surpassed by Boeing only in the latter half of the 1950s. 59 On the other side of the Iron Curtain, commercial air travel was taking off under the leadership of Nikita Khrushchev, who aimed to expand Aeroflot’s reach outside of the Soviet bloc. 60 Throughout this period, Western European, Soviet, and American airlines worked to extend their global networks, making destinations in Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, and the Middle East more accessible for leisure travelers. Latin America also saw a boom in commercial aviation in the 1950s, thanks in no small part to infrastructure that had been developed in conjunction with the United States’ wartime lend-lease program. 61

Although international air travel may have most captivated the global imagination, not all journeys in the sky were long-haul. Domestic air travel also grew rapidly in the decades that followed World War II, and national and regional carriers encouraged tourists to take advantage of short flights to extend their holiday fun. A 1946 advertisement for Western Airlines, for example, announced to readers that they, too, could lead a dual existence of work and pleasure, just like “Jack,” the ad’s protagonist. “Jack’s double life,” the ad explained, “is a happy solution that combines work and play. He flies Western Air Lines so he can sandwich in quick ‘flight-seeing’ sidetrips away from business … [to] keep from going stale on the job.” The ad appeared in a “San Francisco Airways Traveler” brochure and encouraged visitors to fly Western Airlines for a brief sojourn in Yellowstone, Las Vegas, or the dude ranches of the Colorado Rockies. 62

Whether tourists were jetting across the Atlantic Ocean or jumping a short flight from San Francisco to Zion National Park, reduced travel time was only one component of air travel’s appeal. The act of flying, of enjoying a birds-eye view of the world while sipping a cocktail or flipping through the pages of the latest in-flight magazine, was itself part of the journey. 63 Airlines strived to give travelers an “authentic” experience, paying careful attention to details such as flight attendants’ uniforms, or the type of meals served to passengers. Some airlines went as far as to offer an in-flight experience that could bridge cultural (and in some cases, colonial) divides. By flying Air Afrique—francophone Africa’s multinational airline—passengers could enjoy a glass of (presumably French) champagne with their choice of “international” entrée or “African specialty.” After all, explained the airline’s in-flight magazine, “cuisine is just one more way to discover Africa!” 64 Founded shortly after African independence in the early 1960s, Air Afrique offered tourists a chance to participate in the cultural rapprochement between France and its former colonies simply by enjoying a meal on board their flight. The relationship between transportation networks and colonial power structures would prove very durable, however, in many cases withstanding the transition to political independence.

Empire on the Move

While one of the primary goals of inter-African airlines such as Air Afrique was to facilitate tourist traffic between newly independent African states, ultimately their route maps differed little from those of their colonial predecessors. Instead of making it easier for Africans to move within the continent, they largely catered to the needs of European business and leisure travelers—with direct flights to all of Europe’s major capitals. Moreover, many of these airlines stayed afloat financially thanks to ongoing investment from the former metropole, support that reinforced many of the unequal relationships that had been cast in the colonial period. 65

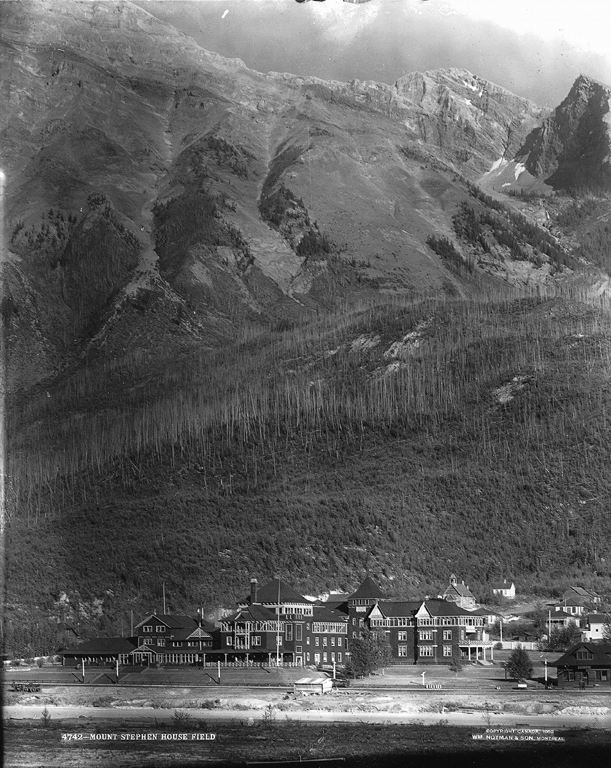

In the decades—and in some cases centuries—that preceded decolonization, transportation infrastructure opened colonized territories for economic exploitation and cemented imperial domination over these spaces. It allowed European governments and corporations to promote their imperial endeavors to a global audience and to justify colonial conquest under the guise of the “civilizing mission.” 66 Ports, roads, and railways also made these spaces accessible to holidaymakers from Europe, the United States, and Canada. Prior to the development of commercial air travel, vacations in the empire generally entailed long voyages by sea, often combined with train and automobile travel. In an epic, nearly five-month “escorted cruise-tour” in 1928, for example, British tour company Thomas Cook & Son transported nine travelers from “Cairo to the Cape” using all three modes of transportation. The tour started with a sea voyage from New York to Cairo aboard the luxury steamer, the SS Franconia . This was followed by a journey over land from Cairo to Cape Town, which took travelers through the core of Britain’s African empire by rail and automobile. The final leg of the journey was a return sea voyage to New York, with stops in Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, and Martinique. According to the tour’s guidebook, it was thanks primarily to new transportation infrastructure that the African continent was now accessible to foreign travelers: “Train, steamer, and motor-car have so penetrated the very heart of the erstwhile ‘Dark Continent’ that journeys which less than five-and-twenty years ago were fraught with hardship and peril and were confined to the explorer may now be undertaken with safety and comparative comfort by the traveler for pleasure.” 67

Not all would-be tourists, of course, had five months of vacation time or $5,000 to spare. The expansion of the commercial air travel industry in the 1930s and 1940s, however, would make shorter trips to Africa, Asia, and the Middle East more accessible for a wider range of travelers. By the 1930s, Air France routes connected Paris to the other key nodes in the French empire, from Dakar to Algiers to Saigon, making these destinations reachable within a matter of hours, or, in the case of Indochina, a few days. 68 In March of 1948, Air France’s monthly bulletin, Echoes of the Air , encouraged travelers to consider Algeria, Morocco, or Tunisia for their spring vacations. Taking off from Paris’s Le Bourget airport at one in the morning, travelers could awaken just hours later and tour the Kasbah of Algiers, the ruins of Carthage, or Marrakech’s main market square, Djemma El Fna. 69

Planes, trains, ships, and cars made colonial empires more accessible for white tourists, but travelers of color met with myriad challenges as they made their way through the world using these modes of transport. Some of these travelers met with discrimination on board, while others struggled to find lodging when weather or engine trouble forced them to spend the night in an unfamiliar place. 70 Although airlines like the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) worked to combat discrimination against transit passengers on the ground, they were often reluctant to take a stand against what they perceived as popular opinion in support of the “colour bar.” In response to mounting demands in the 1950s that the airline confront racism on the ground in the British Caribbean, one BOAC official noted, “to take an airline to task for a matter which is related to public conscience is as unfair as to suggest that airlines must stop the atomic bomb.” 71 While some airlines did attempt to mitigate the effects of racism on transit passengers, most stopped short of embracing travelers of color as tourists in their own right. 72