- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : July 24

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

Lance Armstrong wins seventh Tour de France

On July 24, 2005, American cyclist Lance Armstrong wins a record-setting seventh consecutive Tour de France and retires from the sport. After Armstrong survived testicular cancer, his rise to cycling greatness inspired cancer patients and fans around the world and significantly boosted his sport’s popularity in the United States. However, in 2012, in a dramatic fall from grace, the onetime global cycling icon was stripped of his seven Tour titles after being charged with the systematic use of performance-enhancing drugs.

Born on September 18, 1971, in Plano, Texas , Armstrong started his sports career as a triathlete, competing professionally by the time he was 16. Biking proved to be his strongest event, and at age 17 he was invited to train with the U.S. Olympic cycling developmental team in Colorado . He won the U.S. amateur cycling championship two years later, in 1991, then finished 14th in the road race competition at the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona, Spain. He turned pro later that year but finished last in the Classico San Sebastian, his first race as a professional. In 1993 he bounced back to win 10 titles, including his first major race, the World Road Championships. That same year, he also competed in his first Tour de France, the grueling three-week race that attracts the world’s top cyclists, and won the eighth stage. In 1995 he again won a stage of the Tour de France, as well as the Tour DuPont, a major U.S. cycling event.

Armstrong began 1996 as the number-one-ranked cyclist in the world, but he chose not to race the Tour de France and performed poorly at that year’s Olympics. After experiencing intense pain during a training ride, he was diagnosed in October 1996 with Stage 3 testicular cancer, which had spread to his lungs and brain. He underwent surgery and chemotherapy, then began training again in early 1997. Later that year, he signed with the U.S. Postal Service team. After he quit in the middle of one of his first races back, many thought his career was over. However, after taking some time off from competition, Armstrong came back to finish in the top five at both the Tour of Spain and the World Championships in 1998.

In 1999, to the amazement of the cycling community, Armstrong won his first-ever Tour de France and went on to win the race for the next six consecutive years. In addition to his seven overall wins (a record for both total and consecutive wins), he won 22 individual stages and 11 individual time trials, and led his team to victories in three team time trials between 1999 and 2005. After retiring in 2005, Armstrong made a comeback to pro cycling in 2009, finishing third in that year’s Tour and 23rd in the 2010 Tour. He retired for good from the sport in 2011 at age 39.

Over the years, Armstrong’s intense training regimen and his famed dominance in the difficult and treacherous mountain stages of the Tour de France inspired awe among both fans and opponents. His cycling cadence, which averaged 95 to 100 rotations per minute (rpm) but reached as high as 120 rpm, was considered remarkable, particularly during climbs. In addition to being an exceptionally talented climber, Armstrong performed extremely well in time trials.

Throughout his career, Armstrong, like many other top cyclists of his era, was dogged by accusations of performance-boosting drug use, but he repeatedly and vigorously denied all allegations against him and claimed to have passed hundreds of drug tests. In June 2012 the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA), following a two-year investigation, charged the cycling superstar with engaging in doping violations from at least August 1998, and with participating in a conspiracy to cover up his misconduct. After losing a federal appeal to have the USADA charges against him dropped, Armstrong, while continuing to maintain he had done nothing wrong, announced on August 23 that he would stop fighting the charges. The next day, USADA banned Armstrong for life from competitive cycling and disqualified all his competitive results from August 1, 1998, through the present.

On October 10, 2012, USADA released hundreds of pages of evidence, including sworn testimony from 11 of Armstrong’s former teammates, that the agency said demonstrated Armstrong and the U.S. Postal Service team had been involved in the most sophisticated and successful doping program in the history of cycling. A week after the USADA report was made public, Armstrong stepped down as chairman of his Livestrong cancer awareness foundation, and also was fired from many of his endorsement deals. On October 22, Union Cycliste Internationale, the cycling’s world governing body, announced that it accepted the findings of the USADA investigation and officially was erasing Armstrong’s name from the Tour de France record books and upholding his lifetime ban from the sport.

After years of denials, Armstrong finally admitted publicly, in a televised interview with Oprah Winfrey that aired on January 17, 2013, he had doped for much of his cycling career, beginning in the mid-1990s through his Tour de France victory in 2005. He admitted to using a performance-enhancing drug regimen that included testosterone, human growth hormone, the blood booster EPO and cortisone.

READ MORE: 9 Doping Scandals That Changed Sports

Also on This Day in History July | 24

This Day in History Video: What Happened on July 24

Religious pioneers settle salt lake valley, “eye of the tiger” from “rocky iii” tops the u.s. pop charts, mary queen of scots deposed, apollo 11 safely returns to earth, american archeologist encounters machu picchu ruins.

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Short story writer O. Henry is released from prison

“saving private ryan” opens in theaters, hundreds drown in eastland disaster, a 9-year-old’s murder puts an innocent man in jail, richard nixon and nikita khrushchev have a “kitchen debate”, john hancock scolds major general philip schuyler, operation gomorrah is launched.

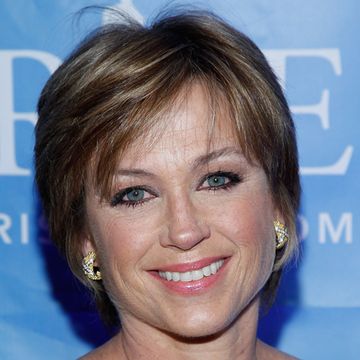

Lance Armstrong

Who Is Lance Armstrong?

Lance Armstrong became a triathlete before turning to professional cycling. His career was halted by testicular cancer, but Armstrong returned to win a record seven consecutive Tour de France races beginning in 1999. Stripped of those titles in 2012 due to evidence of performance-enhancing drug use, Armstrong in 2013 admitted to doping throughout his cycling career, following years of denials.

Early Career

Born on September 18, 1971, in Plano, Texas, Armstrong was raised by his mother, Linda, in the suburbs of Dallas, Texas. Armstrong was athletic from an early age. He began running and swimming at 10 years old, and took up competitive cycling and triathlons at 13. At 16, Armstrong became a professional triathlete—he was the national sprint-course triathlon champion in 1989 and 1990.

Soon after, Armstrong chose to focus on cycling, his strongest event as well as his favorite. During his senior year of high school, the U.S. Olympic development team invited him to train in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Armstrong left high school temporarily to do so, but later took private classes and received his high school diploma in 1989.

The following summer, he qualified for the 1990 junior world team and placed 11th in the World Championship Road Race, with the best time of any American since 1976. That same year, he became the U.S. national amateur champion and beat out many professional cyclists to win two major races, the First Union Grand Prix and the Thrift Drug Classic.

International Cycling Star

In 1991, Armstrong competed in his first Tour DuPont, a long and difficult 12-stage race, covering 1,085 miles over 11 days. Though he finished in the middle of the pack, his performance announced a promising newcomer to the world of international cycling. He went on to win a stage at Italy's Settimana Bergamasca race later that summer.

After finishing second in the U.S. Olympic time trials in 1992, Armstrong was favored to win the road race in Barcelona, Spain. With a surprisingly sluggish performance, however, he came in only 14th. Undeterred, Armstrong turned professional immediately after the Olympics, joining the Motorola cycling team for a respectable yearly salary. Though he came in dead last in his first professional event, the day-long San Sebastian Classic in Spain, he rebounded in two weeks and finished second in a World Cup race in Zurich, Switzerland.

Armstrong had a strong year in 1993, winning cycling's "Triple Crown"—the Thrift Drug Classic, the Kmart West Virginia Classic and the CoreStates Race (the U.S. Professional Championship). That same year, he came in second at the Tour DuPont. He started off well in his first-ever Tour de France, a 21-stage race that is widely considered cycling's most prestigious event. Though he won the eighth stage of the race, he later fell to 62nd place and eventually pulled out.

In August 1993, the 21-year-old Armstrong won his most important race yet: the World Road Race Championship in Oslo, Norway, a one-day event covering 161 miles. As the leader of the Motorola team, he overcame difficult conditions—pouring rain made the roads slick and caused him to crash twice during the race—to become the youngest person and only the second American ever to win that contest.

The following year, he was again the runner-up at the Tour DuPont. Frustrated by his near miss, he trained with a vengeance for the next year's event and went on to finish two minutes ahead of rival Viatcheslav Ekimov of Russia for the win. At the Tour DuPont in 1996, he set several event records, including the largest margin of victory (three minutes, 15 seconds) and the fastest average speed in a time trial (32.9 miles per hour).

Also in 1996, Armstrong rode again for the Olympic team in Atlanta, Georgia. Looking uncharacteristically fatigued, he finished sixth in the time trials and 12th in the road race. Earlier that summer, he had been unable to finish the Tour de France, as he was sick with bronchitis. Despite such setbacks, Armstrong was still riding high by the fall of 1996. Then the seventh-ranked cyclist in the world, he signed a lucrative contract with a new team, France's Team Cofidis.

Battling Testicular Cancer

In October 1996, however, came the shocking announcement that Armstrong had been diagnosed with testicular cancer. Well advanced, the tumors had spread to his abdomen, lungs and lymph nodes. After having a testicle removed, drastically modifying his eating habits and beginning aggressive chemotherapy, Armstrong was given a 65 to 85 percent chance of survival. When doctors found tumors on his brain, however, his odds of survival dropped to 50-50, and then to 40 percent. Fortunately, a subsequent surgery to remove his brain tumors was declared successful, and after more rounds of chemotherapy, Armstrong was declared cancer-free in February 1997.

Throughout his terrifying struggle with the disease, Armstrong continued to maintain that he was going to race competitively again. No one else seemed to believe in him, however, and Cofidis pulled the plug on his contract and $600,000 annual salary. As a free agent, he had a good deal of trouble finding a sponsor, finally signing on to a $200,000-per-year position with the United States Postal Service team.

Tour de France Dominance

At the 1998 Tour of Luxembourg, his first international race since returning from cancer, Armstrong showed he was up for the challenge by winning the opening stage. A little over a year later, he capped his comeback in grand style by becoming the second American, after Greg LeMond, to win the Tour de France. He repeated that feat in July 2000 and followed with a bronze medal at the Summer Olympic Games.

Armstrong bolstered his legacy as his generation's dominant rider by handily winning the Tour in 2001 and 2002. However, notching a fifth victory, tying the record held by Jacques Anquetil, Eddy Merckx, Bernard Hinault and Miguel Indurain, proved his most difficult accomplishment. Stricken by illness before the start of the race, Armstrong fell at one point after snagging a spectator's bag, and barely avoided another crash by swerving across a field. He finished one minute and one second ahead of Germany's Jan Ullrich, the closest of his Tour triumphs.

Armstrong was back in top form to claim his record-breaking sixth Tour win in 2004. He won five individual stages, finishing a comfortable six minutes and 19 seconds ahead of Germany's Andreas Kloden. After capping his astounding run with a seventh consecutive Tour victory in 2005, he retired from racing.

Return to Competition

On September 9, 2008, Armstrong announced that he planned to return to competition and the Tour de France in 2009. A member of Team Astana, he placed third in the race, behind teammate Alberto Contador and Saxo Bank team member Andy Schleck.

After the race, Armstrong told reporters that he intended to compete again in 2010, with a new team endorsed by RadioShack. Slowed by multiple crashes, Armstrong finished 23rd overall in what would be his final Tour de France, and he announced he was retiring for good in February 2011.

Drug Controversy

Despite the inspiring narrative of Armstrong's triumph over cancer, not everyone was convinced it was valid. Irish sportswriter David Walsh, for one, became suspicious of Armstrong's behavior and sought to shed light on the rumors of drug use in the sport. In 2001, he wrote a story linking Armstrong to Italian doctor Michele Ferrari, who was being investigated for supplying performance enhancers to cyclists. Walsh later secured a confession from Armstrong's masseuse, Emma O'Reilly, and laid out his case against the American champion as co-writer of the 2004 book L.A. Confidential.

The plot thickened in 2010, when former U.S. Postal rider Floyd Landis, who had been stripped of his 2006 Tour de France win for drug use, admitted to doping and accused his celebrated teammate of doing the same. That prompted a federal investigation, and in June 2012 the U.S Anti-Doping Agency brought formal charges against Armstrong. The case heated up in July 2012, when some media outlets reported that five of Armstrong's former teammates, George Hincapie, Levi Leipheimer, David Zabriskie and Christian Vande Velde—all of whom participated in the 2012 Tour de France—were planning to testify against Armstrong.

The cycling champion vehemently denied using illegal drugs to boost his performance, and the 2012 USADA charges were no exception: He disparaged the new allegations, calling them "baseless." On August 23, 2012, Armstrong publicly announced that he was giving up his fight with the USADA's recent charges and that he had declined to enter arbitration with the agency because he was tired of dealing with the case, along with the stress the case created for his family.

"There comes a point in every man's life when he has to say, 'Enough is enough.' For me, that time is now," Armstrong said in an online statement around that time. "I have been dealing with claims that I cheated and had an unfair advantage in winning my seven Tours since 1999. The toll this has taken on my family and my work for our foundation and on me leads me to where I am today—finished with this nonsense."

Banned From Cycling

The following day, on August 24, 2012, the USADA announced that Armstrong would be stripped of his seven Tour titles—as well as other honors he received from 1999 to 2005—and banned from cycling for life. The agency concluded in its report that Armstrong had used banned performance-enhancing substances. On October 10, 2012, the USADA released its evidence against Armstrong, which included documents such as laboratory tests, emails and monetary payments. "The evidence shows beyond any doubt that the U.S. Postal Service Pro Cycling Team ran the most sophisticated, professionalized and successful doping program that the sport had ever seen," Travis Tygart, chief executive of the USADA, said in a statement.

The USADA evidence against Armstrong also contained testimony from 26 people. Several former members of Armstrong's cycling team were among those who claimed that Armstrong used performance-enhancing drugs and served as a type of a ringleader for the team's doping efforts. According to The New York Times , one teammate told the agency that "Lance called the shots on the team" and "what Lance said went."

Armstrong disputed the USADA's findings. His attorney, Tim Herman, called the USADA's case "a one-sided hatchet job" featuring "old, disproved, unreliable allegations based largely on axe-grinders, serial perjurers, coerced testimony, sweetheart deals and threat-induced stories," according to USA Today .

Shortly after the release of the USADA findings, the International Cycling Union (cycling's governing body) supported the USADA's decision and officially stripped Armstrong of his seven Tour de France victories. The union also banned Armstrong from the sport for life. ICU president Pat McQuaid said in a statement that "Lance Armstrong has no place in cycling."

Admission and Later Events

Of the interview, Winfrey said in a statement, "He did not come clean in the manner I expected. It was surprising to me. I would say that, for myself, my team, all of us in the room, we were mesmerized by some of his answers. I felt he was thorough. He was serious. He certainly prepared himself for this moment. I would say he met the moment. At the end of it, we both were pretty exhausted."

Around the same time that the interview was conducted, it was reported that the U.S. Department of Justice would join a lawsuit already in place against the cyclist, over his alleged fraud against the government. Armstrong's attempts to have the lawsuit dismissed were rejected, and in early 2017 the case was allowed to proceed to trial.

Fraud Settlement

In spring 2018, two weeks before his trial was scheduled to begin, Armstrong agreed to pay the U.S. Postal Service $5 million to settle their claims of being defrauded. According to his legal team, the settlement ended "all litigation against Armstrong related to his 2013 admission" of using performance-enhancing drugs.

"I am particularly glad to have made peace with the Postal Service," said Armstrong said in a statement. "While I believe that their lawsuit against me was without merit and unfair, I have since 2013 tried to take full responsibility for my mistakes, and make amends wherever possible. I rode my heart out for the Postal cycling team, and was always especially proud to wear the red, white and blue eagle on my chest when competing in the Tour de France."

Landis, the whistle-blower in the case, stood to receive $1.1 million of the amount paid to the government. Additionally, Armstrong agreed to shell out $1.65 million to cover his old teammate's legal expenses.

Movie and Documentaries

In 2015, the Armstrong biopic The Program , with Ben Foster portraying the fallen cyclist, premiered at the Toronto Film Festival. Armstrong had little to say about the film, other than criticizing its star for taking performance-enhancing drugs to prepare for the role.

Armstrong was far more receptive to the release of Icarus , a Netflix documentary in which amateur cyclist Bryan Fogel also pumps up on PEDs before uncovering a Russian state-sponsored system created to mask its athletes' use of such drugs. In late 2017, Armstrong tweeted: "After being asked roughly a 1000 times if I’ve seen @IcarusNetflix yet, I finally sat down to check it out. Holy hell. It’s hard to imagine that I could be blown away by much in that realm but I was. Incredible work @bryanfogel!"

It was subsequently announced that on January 6, 2018, the day after Academy Award voters could begin submitting their ballots, Armstrong would co-host a screening and reception for Icarus in New York.

The cyclist returned to the spotlight with the Marina Zenovich-directed documentary Lance , which premiered at the January 2020 Sundance Film Festival before airing on ESPN that May. Along with examining the formative influences that drove him to become such a ruthless competitor, the doc showcased Armstrong's attempts to adapt to public life in the years after he had fallen from his pedestal as one of the world's most admired athletes.

Charity, Personal Life and Children

Armstrong has lived in Austin, Texas, since 1990. In 1996, he founded the Lance Armstrong Foundation for Cancer, now called LiveStrong, and the Lance Armstrong Junior Race Series to help promote cycling and racing among America's youth. He is the author of two best-selling autobiographies, It's Not About the Bike: My Journey Back to Life (2000) and Every Second Counts (2003).

In 2006, Armstrong ran the New York City Marathon, raising $600,000 for his LiveStrong campaign. He stepped down from LiveStrong in October 2012 following the USADA report about his use of performance-enhancing drugs.

Armstrong married Kristin Richard, a public relations executive he met through his cancer foundation, in 1998. The couple had a son, Luke, in October 1999, using sperm frozen before Armstrong began chemotherapy. Twin daughters, Isabelle and Grace, were born in 2001. The couple filed for divorce in 2003. Afterward, he dated rocker Sheryl Crow , fashion designer Tory Burch and actresses Kate Hudson and Ashley Olsen .

In December 2008, Armstrong announced that his girlfriend, Anna Hansen, was pregnant with his child. The couple had been dating since July after meeting through Armstrong's charity work. The baby boy, Maxwell Edward, was born on June 4, 2009. A daughter, Olivia Marie, followed on October 18, 2010.

In July 2013, Armstrong made headlines again when it was reported that he would be competing in The Des Moines Register 's Annual Great Bicycle Ride Across Iowa, a statewide cycling race sponsored by the newspaper.

"I'm well aware my presence is not an easy topic, and so I encourage people if they want to give a high-five, great," Armstrong stated shortly after the news broke, according to the Daily Mail . "If you want to shoot me the bird, that's OK too. I'm a big boy, and so I made the bed, I get to sleep in it."

In 2015, Armstrong returned to the Tour de France course to ride in a leukemia charity event one day before the start of the race.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Lance Armstrong

- Birth Year: 1971

- Birth date: September 18, 1971

- Birth State: Texas

- Birth City: Plano

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Lance Armstrong is a cancer survivor and former professional cyclist who was stripped of his seven Tour de France wins due to evidence of performance-enhancing drug use.

- Astrological Sign: Virgo

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Lance Armstrong Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/athletes/lance-armstrong

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: April 23, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- There comes a point in every man's life when he has to say, 'Enough is enough.' For me, that time is now.

- My ruthless desire to win at all costs served me well on the bike but the level it went to, for whatever reason, is a flaw. That desire, that attitude, that arrogance.

- The biggest challenge of the rest of my life is to not slip up again and not lose sight of what I have to do. I had it but things got too big and too crazy.

- If you're trying to hide something, you wouldn't keep getting away with it for 10 years. Nobody is that clever.

- I know the truth. The truth isn't what was out there. The truth isn't what I said, and now it's gone—this story was so perfect for so long.

- There was more happiness in the process, in the build, in the preparation. The winning was almost phoned in.

- If you're asking me if I want to compete again, the answer is hell yes, I'm a competitor.

- I learned a lesson that day. No more gifts."[On giving Marco Pantani a stage win in the 2000 Tour de France]

- The Look was just one part of a great battle with the Telekom team all day.

- Nobody believed I was able to do that after the crash. But I was a desperate man, and I knew that was my last chance to win the Tour de France.

- I'm well aware my presence is not an easy topic, and so I encourage people if they want to give a high-five, great. If you want to shoot me the bird, that's OK too. I'm a big boy, and so I made the bed, I get to sleep in it.

- I am deeply flawed ... and I'm paying the price for it, and I think that's okay. I deserve this."[On being stripped of his seven Tour de France titles for doping as a pro cyclist.]

- Two things scare me: The first is getting hurt. But that's not nearly as scary as the second, which is losing.

- Pain is temporary. It may last a minute, or an hour, or a day, or a year, but eventually it will subside and something else will take its place. If I quit, however, it lasts forever.

Famous Athletes

Jesse Owens

Alice Coachman

Wilma Rudolph

Tiger Woods

The Final Four Is Personal for Caitlin Clark

Sha’Carri Richardson

Aaron Rodgers

Florence Joyner

Lionel Messi

10 Things You Might Not Know About Travis Kelce

Every Black Quarterback to Play in the Super Bowl

Lance Armstrong's Greatest Tour de France Moments

1993: a glimpse into the future.

1999: Making a Statement

- Tour de France Home

1999: Sealing the Victory

2003: le train bleu, 2005: a historic end, .css-1t6om3g:before{width:1.75rem;height:1.75rem;margin:0 0.625rem -0.125rem 0;content:'';display:inline-block;-webkit-background-size:1.25rem;background-size:1.25rem;background-color:#f8d811;color:#000;background-repeat:no-repeat;-webkit-background-position:center;background-position:center;}.loaded .css-1t6om3g:before{background-image:url(/_assets/design-tokens/bicycling/static/images/chevron-design-element.c42d609.svg);} tour de france.

Challengers of the 2024 Giro d'Italia and TdF

2024 Tour de France May Start Using Drones

The 2024 Tour de France Can’t Miss Stages

Riders Weigh In on the Tour de France Routes

2024 Tour de France Femmes Can't-Miss Stages

How Much Money Do Top Tour de France Teams Make?

2024 Tour de France/ Tour de France Femmes Routes

How Much Did Tour de France Femmes Riders Earn?

5 Takeaways from the Tour de France Femmes

Who Won the 2023 Tour de France Femmes?

Results From the 2023 Tour de France Femmes

Lance Armstrong wins seventh consecutive and last Tour de France

Lance Armstrong closed out his amazing career with a seventh consecutive Tour de France victory today — and did it a little earlier than expected.

Share story

PARIS — Lance Armstrong closed out his amazing career with a seventh consecutive Tour de France victory today — and did it a little earlier than expected. Because of wet conditions, race organizers stopped the clock as Armstrong and the main pack entered Paris. Although riders were still racing, with eight laps of the Champs-Elysees to complete, organizers said that Armstrong had officially won. The stage started as it has done for the past six years — with Armstrong celebrating and wearing the race leader’s yellow jersey. One hand on his handlebars, the other holding a flute of champagne, Armstrong toasted his teammates as he pedaled into Paris to collect his crown. He held up seven fingers — one for each win — and a piece of paper with the number 7 on it. When it was over, Armstrong saluted the race he’s made his own. “Vive le Tour, forever,” he said. Armstrong choked up on the victory podium as he stood next to his twin 3-year-old daughters — dressed in bright yellow dresses, appropriately — and his son. His rock star girlfriend Sheryl Crow, wearing a yellow halter top, cried during the ceremony. “This is the way he wanted to finish his career, so it’s very emotional,” she said. Looking gaunt, his cheeks hollow after riding 2,232.7 miles across France and its mountains for three weeks, Armstrong still could smile at the end. He said President Bush called to congratulate him. Armstrong’s new record of seven wins confirmed him as one of the greatest cyclists ever, and capped a career where he came back from cancer to dominate cycling’s most prestigious and taxing race. Standing on the podium, against the backdrop of the Arc de Triomphe, Armstrong managed a rare feat in sports — going out on the top of his game. He previously said that his decision was final and that he was walking away with “absolutely no regrets.” Armstrong mentioned Tiger Woods, Wayne Gretzky, Michael Jordan and Andre Agassi as personal inspirations. “Those are guys that you look up to you, guys that have been at the top of their game for a long time,” he said. As for his accomplishments, he said, “I can’t be in charge of dictating what it says or how you remember it.” “In five, 10, 15, 20 years, we’ll see what the legacy is. But I think we did come along and revolutionize the cycling part, the training part, the equipment part. We’re fanatics.” Alexandre Vinokourov of Kazakhstan eventually won the final stage, with Armstrong finishing safely in the pack to win the Tour by more than 4 minutes, 40 seconds over Ivan Basso of Italy. The 1997 Tour winner, Jan Ullrich, was third, 6:21 back. “It’s up to you guys,” Armstrong said, forecasting the Tour future. Armstrong’s sixth win last year already set a record, putting Armstrong ahead of four other riders — Frenchmen Jacques Anquetil and Bernard Hinault, Belgian Eddy Merckx and Spaniard Miguel Indurain — who all won five Tours. Along the way, he brought unprecedented attention to the sport, and won over many who had dismissed it. “Finally, the last thing I’ll say for the people who don’t believe in cycling — the cynics, the skeptics — I’m sorry for you,” Armstrong said. “I’m sorry you can’t dream big and I’m sorry you don’t believe in miracles. But this is one hell of a race, this is a great sporting event and you should stand around and believe.” Armstrong’s last ride as a professional — the closing 89.8-mile 21st stage into Paris from Corbeil-Essonnes south of the capital — was not without incident. Three of his teammates slipped and crashed on the rain-slicked pavement coming around a bend just before they crossed the River Seine. Armstrong, right behind them, braked and skidded into the fallen riders. Armstrong used his right foot to steady himself, and was able to stay on the bike. His teammates, wearing special shirts with a band of yellow on right shoulder, recovered and led him up the Champs-Elysees at the front of the pack. Organizers then announced that they had stopped the clock because of the slippery conditions with more than 10 miles to go. Vinokourov surged ahead of the main pack to win the last stage. He had been touted as one of Armstrong’s main rivals at the start of the Tour on July 2, but like others was overwhelmed by the 33-year-old Texan. Armstrong’s departure begins a new era for the 102-year-old Tour, with no clear successor. His riding and his inspiring defeat of cancer attracted new fans — especially in the United States — to the race, as much a part of French summers as sun cream, forest fires and traffic jams down to the Cote d’Azur. Millions turned out each year, cheering, picnicking and sipping wine by the side of the road, to watch him flash past in the race leader’s yellow jersey, the famed “maillot jaune.” Cancer survivors, autograph hunters and enamored admirers pushed, shove, and yelled “Lance! Lance!” outside his bus in the mornings for a smile, a signature, or a word from the champion. He had bodyguards to keep the crowds at bay — ruffling feathers of cycling purists who sniffed at his “American” ways. Some spectators would shout obscenities or “dope!” — doper. To some, his comeback from cancer and his uphill bursts of speed that left rivals gasping in the Alps and Pyrenees were too good to be true. Armstrong insisted that he simply trained, worked and prepared harder than anyone. He was drug-tested hundreds of times, in and out of competition, but never found to have committed any infractions. Armstrong came into this Tour saying he had a dual objective — winning the race and the hearts of French fans. He was more relaxed, forthcoming and talkative than last year, when the pressure to be the first six-time winner was on. Some fans hung the Stars and Stripes on barriers that lined the Champs-Elysees on Sunday. Around France, some also urged Armstrong to go for an eighth win next year— holding up placards and daubing their appeals in paint on the road. Armstrong, however, wanted to go out on top — and not let advancing age get the better of him. “At some point you turn 34, or you turn 35, the others make a big step up, and when your age catches up, you take a big step down,” he said Saturday after he won the final time trial. “So next could be the year if I continued that I lose that five minutes. We are never going to know.”

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

From cancer to cycling superman: is this the greatest story in modern sport?

Seven years after completing treatment for cancer so virulent that he was given only a 40% chance of survival, the American cyclist Lance Armstrong yesterday became the first man to win the Tour de France, the world's most gruelling sporting challenge, on six occasions.

After spending 83 hours 36 minutes and two seconds in the saddle since the race began three weeks ago, Armstrong pedalled over the cobbles of the sunlit Champs-Elysées to claim a victory that some believe sets the seal on the greatest story in modern sport.

The 32-year-old Texan's tale has already been the subject of two best-selling volumes of autobiography, and his battle against the disease has inspired the foundation of a hugely successful cancer charity.

Brought up in a small town by a teenage single mother, Armstrong showed an early talent for running and swimming. At 16, having saved his pocket money, he bought his first bicycle and took up the triathlon. A professional cyclist at 20, he entered the Tour de France for the first time a year later and, as a brash unknown, became the youngest man to win a stage in the race since the second world war.

"Even as a child," his mother said, "he knew what he wanted," and his career was going nicely when, in the autumn of 1996, he noticed specks of blood appearing when he coughed. At St David's hospital in Austin, Texas, he was told that testicular cancer had spread to his lungs and his brain. A two-hour operation the next day was followed by three months of intensive chemotherapy in Indianapolis.

"If I wasn't in pain, I was vomiting," he wrote in the award-winning book It's Not About The Bike, "and if I wasn't vomiting I was thinking about what I had. Chemo was a burning in my veins, a matter of being slowly eaten from the inside out by a destroying river of pollutants." Nevertheless, only 518 days later he was back in the saddle, competing in a race.

Yesterday many of his fellow riders were wearing the yellow bracelet that has been sold, for a dollar or a euro, all the way along the 2,000 miles of the Tour's route. More than $5m (£2.8m) will be raised by this means for Armstrong's foundation, whose motto is "Live strong".

His triumph has been shadowed, however, by persistent claims concerning his association with an Italian doctor, Michele Ferrari, who is under investigation for allegedly supplying EPO, a synthetic human growth hormone, to riders. At the beginning of this year's Tour the publication in French of a book entitled LA Confidentiel, featuring claims that his team had systematically used EPO, provoked an angry response from Armstrong. After failing in a legal attempt to force the publishers to include his own statement in every copy, he has promised to sue the authors for libel.

The American's success has come at a time when the phenomenon of widespread drug-taking within the sport is receiving greater publicity than ever before, thanks to the aggressive action of the French police and a handful of investigative journalists.

Several prominent cyclists, most recently the British rider David Millar, have been banned from competition. Marco Pantani, an Italian who became the last man to win the Tour before Armstrong began his run of victories, died this year from an overdose of heroin and cocaine, his career ruined by a series of positive dope tests.

Armstrong, however, has tested positive only once, in 1999, when minute traces of a synthetic cortocosteroid were discovered in a urine sample. The authorities accepted his explanation that it had been part of a proprietary skin cream used to treat saddle boils, an inescapable feature of the cycle racer's arduous life.

The public's divergent views on the nature of his success were evident last week on the climb up to l'Alpe d'Huez, one of the Tour's most famous features, where fans paint messages of support on the steeply winding roadway. As he raced along, Armstrong's eyes passed over a series of messages ranging in tone from "RIP THEIR BALLS OFF, LANCE" to "EPO ARMSTRONG". A few days earlier he was said to have been spat on by spectators.

Most cycling fans, however, accept that the use of illegal performance-enhancing substances goes back as far as the origins of the 101-year-old Tour.

When Jacques Anquetil, one of the quartet of five-times winners, was once asked about doping, he responded in exasperation: "Do they expect us to ride up these mountains on mineral water?" Until concrete evidence is produced against Armstrong, the majority appear content to welcome him to a unique place in the pantheon.

For the sixth year in succession the Star-Spangled Banner sounded on the Champs-Elysées as he ascended the podium to accept the trophy and don the yellow jersey under the eye of his girlfriend Sheryl Crow, the rock singer, who not only followed him around the race but accompanied him on the weeks of training runs with which he reconnoitred the course in the spring. His friend Robin Williams, the actor, was also at hand.

Although Armstrong, who lives most of the year in Spain, has pointedly expressed his disapproval of George Bush's foreign policy, the president, a fellow Texan, yesterday called him to congratulate him on behalf of the nation. "You're awesome," he told him.

The minute thoroughness of Armstrong's preparation, and the collective strength of his US Postal Service team, are among the factors contributing to the success that has made him a multimillionaire.

What is less easy to define is the origin of a ferocious competitive spirit that burned even more fiercely this year as he reduced his rivals to shattered wrecks.

Calling it revenge on the disease that tried to take his life is too glib. Armstrong was a fighter from the start. But cancer certainly gave him the experience of confronting and beating a bigger opponent than any he has faced on a bike.

- Tour de France 2004

- Tour de France

- Lance Armstrong

- Testicular cancer

Most viewed

- Brentley Romine ,

Trending Teams

Lance armstrong timeline: cancer, tour de france, doping admission.

- OlympicTalk ,

- OlympicTalk

MONTAIGU, FRANCE - JULY 04: TOUR DE FRANCE 1999, 1.Etappe, MONTAIGU - CHALLANS; Lance ARMSTRONG/USA - GELBES TRIKOT - (Photo by Andreas Rentz/Bongarts/Getty Images)

Bongarts/Getty Images

A look at the rise and fall of Lance Armstrong , who beat testicular cancer to win a record seven Tour de France titles, then was found guilty of and admitted to doping for the majority of his career ...

Aug. 2, 1992: Armstrong, then a 20-year-old amateur cyclist who had left triathlon because it wasn’t an Olympic sport, makes his Olympic debut at the Barcelona Games. He finishes 14th in the road race as the top American, missing a late breakaway. “I don’t think it was one of my better days, unfortunately,” Armstrong said on NBC. “Last couple weeks, everything has been perfect, but today, I just didn’t have what it took.” A week later, Armstrong finished last of 111 riders in his pro debut.

Aug. 29, 1993: Wins the world championships road race, becoming the second U.S. man to win a senior road cycling world title after three-time Tour de France winner Greg LeMond . Armstrong prevails by 19 seconds over Spain’s Miguel Indurain , who won five straight Tours de France from 1991-95. “I’m not sure I’m cut out to be a Tour racer,” Armstrong said, according to the Chicago Tribune . “I love the Tour de France; it’s my favorite bike race, but I’m not fool enough to sit here and say I’m going to win it. For the time being, I’m a one-day rider.”

Aug. 3, 1996: After failing to finish three of his first four Tour de France appearances (and placing 36th in the other), is sixth in the Atlanta Olympic time trial. “This was a big goal and something that I wanted to do well in and wanted the American people to see success,” Armstrong said on NBC. “The legs just weren’t there to win or to medal. I have to move forward and look to the next thing.”

Oct. 2, 1996: Diagnosed with testicular cancer. A day later, he undergoes surgery to have the malignant right testicle removed. Five days later, he begins chemotherapy. Six days later, Armstrong holds a press conference to announce it publicly, saying the cancer spread to his abdomen (and, later, his brain). He described it as “between moderate and advanced” and that his oncologist told him the cure rate was between 65 and 85 percent. “I will win,” Armstrong says. “I intend to beat this disease, and further, I intend to ride again as a professional cyclist.”

Oct. 27, 1996: Betsy Andreu later testifies that, on this date, Armstrong told a doctor at Indiana University Hospital that he had taken performance-enhancing drugs; EPO, testosterone, growth hormone, cortisone and steroids. Andreu said she and others were in a room to hear this. Her husband, Frankie Andreu , an Armstrong cycling teammate, confirmed her recollection to the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA). Armstrong, in admitting to doping in 2013, declined to address what became known as “the hospital room confession.”

January 1997: Establishes the Lance Armstrong Foundation, later called Livestrong, to support cancer awareness and research. Is later declared cancer-free.

Feb. 15, 1998: Returns to racing. Later in September, finishes fourth in his Grand Tour return at the Vuelta a Espana, one of the three Grand Tours after the Giro d’Italia and Tour de France.

1999 Tour de France: Achieves global fame by winning cycling’s most prestigious event in his first Tour de France start since his cancer diagnosis. Armstrong was not a pre-event favorite, but he won the opening 4.2-mile prologue to set the tone. He won all three time trials and, by the end, distanced second-place Alex Zulle by 7 minutes, 37 seconds in a Tour that lacked the previous two winners -- Jan Ullrich and Marco Pantani . Armstrong faced doping questions during the three-week Tour. An Armstrong urine sample revealed a small amount of a corticosteroid, after which Armstrong produced a prescription for a cream to treat saddle sores to justify it. “There’s no secrets here,” Armstrong said after Stage 14. “We have the oldest secret in the book: hard work.”

2000 Tour de France: With Ullrich and Pantani in the field, Armstrong crushed them on Stage 10, taking the yellow jersey by four minutes. He ends up winning the Tour by 6:02 over Ullrich, who over the years became the closest thing Armstrong had to a rival. In a Nike commercial that debuted in January that year , Armstrong again attacked his critics, saying, “Everybody wants to know what I’m on. What am I on? I’m on my bike, busting my ass six hours a day. What are you on?”

Sept. 30, 2000: Takes bronze in the Sydney Olympic time trial, behind Russian Viatcheslav Ekimov (a teammate on Armstrong’s Tour de France teams) and Ullrich. Armstrong would be stripped of the bronze medal 12 years later for doping. “I came to win the gold medal,” he said on NBC. “When you prepare for an event and you come and you do your best, and you don’t win, you have to say, I didn’t deserve to win.”

2001 Tour de France: Third straight Tour title. In Stage 10 on the iconic Alpe d’Huez, Armstrong gave what came to be known as “The Look,” turning back to stare in sunglasses at Ullrich, then accelerating away to win the stage by 1:59 over the German. “I decided to give a look, see how he was, then give a little surge and see what happened,” Armstrong said after the stage. Also that year, LeMond gives a famous quote to journalist David Walsh on Armstrong: “If it is true, it is the greatest comeback in the history of sport. If it is not, it is the greatest fraud.”

2002 Tour de France: Fourth title in a row -- by 7:17 over Joseba Beloki sans Ullirch and Pantani -- with few notable highlights. Maybe the most memorable, French fans yelling “Dope!” as he chased Richard Virenque (another disgraced doper) up the esteemed Mont Ventoux. Armstrong would be named Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year.

2003 Tour de France: By far the closest of the Tour wins -- by 1:01 over Ullrich -- with two very close calls. In Stage 9, Armstrong detoured through a field to avoid a crashing Beloki, who broke his right femur and never contended at a Grand Tour again. In Stage 15, Armstrong’s handlebars caught a spectator’s yellow bag . He crashed to the pavement, remounted and won the stage, upping his lead from 15 seconds to 1:07 over Ullrich.

2004 Tour de France: Record-breaking sixth Tour de France title. Jacques Anquetil , Eddy Merckx , Bernard Hinault and Indurain shared the record of five, and now share the record again after Armstrong’s titles were stripped. Earlier in 2004, the Livestrong yellow bracelet/wristband is introduced. Tens of millions would be sold. He skips the 2004 Athens Olympics, which began three weeks after the Tour ended.

April 18, 2005: Announces he will retire after the 2005 Tour de France. “My children are my biggest supporters, but at the same time, they are the ones who told me it’s time to come home,” Armstrong says. On the same day, former teammate and 2004 Olympic time trial champion Tyler Hamilton is banned two years for blood doping.

2005 Tour de France: Finishes career with seventh Tour de France title. Armstrong remains defiant until the end. In his victory speech atop a podium on the Champs-Elysees, he says with girlfriend Sheryl Crow looking on, “The last thing I’ll say, for the people that don’t believe in cycling, the cynics and the skeptics, I"m sorry for you. I’m sorry you can’t dream big. And I’m sorry you don’t believe in miracles.” A month later, French sports daily newspaper L’Equipe publishes a front-page article headlined, “Le Mensonge Armstrong” or “The Armstrong Lie.” It reports that six Armstrong doping samples at the 1999 Tour de France showed the presence of the banned EPO.

Sept. 9, 2008: Announces comeback, the reason being “to launch an international cancer strategy,” in a video on his foundation’s website . In his 2013 doping confession, Armstrong says he regrets the comeback. “We wouldn’t be sitting here if I didn’t come back,” he tells Oprah Winfrey on primetime TV.

2009 Tour de France: Finishes third, 5:24 behind rival Astana teammate and Spanish winner Alberto Contador . “I can’t complain,” Armstrong said on Versus after the penultimate stage finishing atop Mont Ventoux. “For an old fart, coming in here, getting on the podium with these young guys, not so bad.” USADA later reported that scientific data showed Armstrong used EPO or blood transfusions during that Tour, which Armstrong denied in 2013 when admitting to doping earlier in his career.

2010 Tour de France: Finishes 23rd in his last Tour de France. Armstrong races after former teammate Floyd Landis admits to doping and accuses Armstrong and other former teammates of doping during the Tour de France wins. “At some point, people have to tell their kids that Santa Claus isn’t real,” Landis says in a “Nightline” interview that aired the final weekend of the Tour.

Feb. 16, 2011: Announces retirement, citing tiredness (in multiple respects) at age 39. “I can’t say I have any regrets. It’s been an excellent ride. I really thought I was going to win another Tour,” Armstrong said, according to The Associated Press. “Then I lined up like everybody else and wound up third.”

Aug. 24, 2012: USADA announces Armstrong is banned for life , and all of his results dating to Aug. 1, 1998, annulled, including all seven Tour de France titles. Armstrong chose not to contest the charges, which were first sent to him in a June letter, though he did not publicly admit to cheating. USADA releases details of the investigation in October. The International Cycling Union chooses not to contest USADA’s ruling, formally stripping him of the Tour de France titles. “Lance Armstrong has no place in cycling,” UCI President Pat McQuaid says. In November, a defiant Armstrong tweets an image of him lying on a couch in a room with seven framed Tour de France yellow jerseys on the walls.

Jan. 17, 2013: Admits to doping during all of his Tour de France victories in the Oprah confession that airs on primetime TV. “I viewed this situation as one big lie that I repeated a lot of times,” Armstrong says in a pre-recorded interview. “It’s just this mythic, perfect story, and it wasn’t true.” Armstrong said he did not view it as cheating while he was taking PEDs because others did, too. On the same day, the International Olympic Committee strips Armstrong of his 2000 Olympic bronze medal.

MORE: Giro, Vuelta overlap in new cycling schedule

OlympicTalk is on Apple News . Favorite us!

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Dark Turn in the Tale of a First Title

By Jeré Longman

- Oct. 10, 2012

Just before the 1999 Tour de France, a teammate pointed out that Lance Armstrong had a bruise on his upper arm caused by a syringe.

According to a doping investigation, Armstrong cursed and said, “That’s not good.”

A public weigh-in of the riders was to be attended by the news media. A team masseuse found some makeup, and Armstrong’s bruise, and the doping that investigators assert caused it, was ultimately concealed.

The 1999 Tour was supposed to be one of renewal after a doping scandal engulfed the 1998 race. Instead, Armstrong won his first of his seven Tours by using the prohibited blood-boosting agent EPO and the steroid hormone testosterone, according to a 200-page report released Wednesday by the United States Anti-Doping Agency.

While Armstrong has long protested his innocence, retroactive testing found EPO in six of Armstrong’s urine samples from the 1999 race, according to the report. In addition, the report said, five fellow riders on Armstrong’s 1999 United States Postal Service team — George Hincapie, Frankie Andreu, Tyler Hamilton, Jonathan Vaughters and Christian Vande Velde — provided affidavits testifying to firsthand knowledge that Armstrong violated antidoping rules, the report said.

The evidence that Armstrong used EPO in the 1999 race was overwhelming, the report said, adding, “No other conclusion is even plausible.”

The tale behind Armstrong’s first Tour triumph, an achievement that made him an instant celebrity, is laid out in the investigative report in almost novelistic fashion. It involves a man on a motorcycle who delivered drugs to Armstrong’s team, an Italian doctor who was famous for helping riders dope, a training regimen designed to avoid drug testing, and the active complicity of the team masseuse.

The 1999 racing season began, the report said, with an unlikely goal for Armstrong, a cancer survivor: to win the Tour de France. He would skip many of the buildup races to concentrate on his sport’s major event. And for fuel, the report said, he would rely on banned substances.

A new team director, Johan Bruyneel, and team doctor, Luis Garcia del Moral, were hired that year for the Postal Service team. Armstrong called the team the Bad News Bears. He wanted a new team, according to the affidavit by Vaughters, his teammate, because the outgoing doctor, Pedro Celaya, “had not been aggressive enough for Armstrong in providing banned products.”

Bruyneel and del Moral, on the other hand, had formerly been associated with a racing team widely known, the report said, for “its organized team doping.”

Cyclists who wanted to dope had two main advantages in 1999, the report noted. Cycling’s international governing body had no organized out-of-competition drug testing program — considered the only effective way to catch those using banned substances. The governing body also did not require riders to make their whereabouts known during training so that they could be screened.

Much of Armstrong’s pre-Tour training in 1999 was spent along remote mountain roads of the Alps and the Pyrenees. Two teammates — Hamilton and Kevin Livingston — assisted him with arduous climbing, the report said. A regular attendee at these training camps, the report said, was an Italian sports doctor named Michele Ferrari, who would later be accused by American doping officials of trafficking in banned substances.

Hamilton was first injected with EPO in 1999 by Ferrari during training at Sestriere, an Italian ski village that would be a mountaintop finish during the Tour, the report said. Andreu said in an affidavit that he received EPO injections at races that year from del Moral, the Postal Service team doctor.

Pepe Marti, the Postal Service team trainer, also provided EPO to riders in 1999, the report said. At a late dinner in Nice, France, Betsy Andreu, Frankie’s wife, said that Marti arrived to provide what she was told was EPO to Armstrong. The dinner was held late, she said, because Marti was traveling from Spain and considered it “safer to cross the border at night.”

Armstrong took a brown paper bag from Marti, held it up and, according to Andreu, called it “liquid gold.”

In May 1999, Emma O’Reilly, the team masseuse, made an 18-hour round-trip drive from Nice to Spain to deliver a bottle of pills to Armstrong that, according to the report, “she understood to be banned drugs.”

That same month, Hamilton was at Armstrong’s villa in Nice, and received a vial of EPO from Armstrong that had been stored in Armstrong’s refrigerator, the report said.

On June 10, 1999, less than a month before the Tour began, Armstrong’s hematocrit level — the percentage by volume of oxygen-carrying red blood cells in whole blood — hovered at 41 percent, below the allowable race limit of 50 percent, the report said.

When O’Reilly, the masseuse, asked Armstrong how he would optimize his performance, the report said that he responded, “What everybody does.” O’Reilly understood this to mean Armstrong would use EPO, the report said.

The Tour de France opened July 3, 1999, and ran through July 25. Armstrong won the prologue, but a few days later, he received notice of a positive test for a corticosteroid, a chemical that helps regulate inflammation, metabolism and electrolyte levels.

Because Armstrong did not have medical authorization to use corticosteroids, the report said, a story was fabricated to backdate a prescription for cortisone cream and claim that the medication had been prescribed to treat a saddle sore, the report said.

According to the report, Armstrong told O’Reilly, the masseuse, “Now, Emma, you know enough to bring me down.”

During the first two weeks of the Tour, Armstrong, Hamilton and Livingston used EPO every third or fourth day in their camper or hotel rooms, the report said. Armstrong, Hamilton and Livingston traveled in a newer, bigger camper during that Tour, while other Postal Service riders shoehorned into a smaller, older vehicle. Hamilton and Livingston also shared a hotel room so they could speak openly with Armstrong about doping, the report said.

The three riders would “inject quickly and then put the syringes in a bag or Coke can and Dr. del Moral would get the syringe out of the camper as quickly as possible,” the report said.

Because security was tight, the EPO was smuggled to the Postal Service team by a personal assistant and handyman for Armstrong, the report said. He was a motorcycle enthusiast who followed the Tour on his motorcycle, and the riders who knew his purpose gave him the nickname Motoman.

Armstrong also used testosterone, which builds muscle and aids recovery from exertion, during the 1999 Tour, the report said. He mixed it with olive oil in a concoction that was taken orally. After one stage, the report said, Armstrong squirted the “oil” in Hamilton’s mouth.

After relinquishing the yellow jersey, Armstrong reclaimed first place in a time trial, then rode to a dominant mountaintop finish in Sestriere, the Italian ski village. He was not then known as a great climber, and Christophe Bassons, a French rider, noted in a newspaper column that the peloton had been “shocked” by Armstrong’s ride up to Sestriere.

At the race’s end, however, Armstrong proclaimed his innocence. He won the Tour six more times.

Cycling Around the Globe

The cycling world can be intimidating. but with the right mind-set and gear you can make the most of human-powered transportation..

Are you new to urban biking? These tips will help you make sure you are ready to get on the saddle .

Whether you’re mountain biking down a forested path or hitting the local rail trail, you’ll need the right gear . Wirecutter has plenty of recommendations , from which bike to buy to the best bike locks .

Do you get nervous at the thought of cycling in the city? Here are some ways to get comfortable with traffic .

Learn how to store your bike properly and give it the maintenance it needs in the colder weather.

Not ready for mountain biking just yet? Try gravel biking instead . Here are five places in the United States to explore on two wheels.

Lance Armstrong: I'd have won the Tour de France if everyone was clean

'We did what we had to do to win'

Lance Armstrong says he and his teams would have won the Tour de France multiple times if the entire peloton was riding clean during his now-stripped reign of seven victories from 1999 through 2005.

Lance Armstrong: Uber investment 'saved' my family

Lance Armstrong to feature in ESPN film series

Lance Armstrong's $1 million Tour Down Under start money confirmed

Lance Armstrong: I wouldn't change a thing

In a wide-ranging interview with NBC Sports as part of the network’s 2019 Tour de France coverage, journalist Mike Tirico interviewed the 47-year-old whose seven Tour de France victories were taken away after the US Anti-Doping Agency's investigation and 2012 "Reasoned Decision" detailing Armstrong’s guilt.

Although Armstrong told Tirico his decision to dope was a mistake, he also said he wouldn't change a thing in his career, and he was proud of the efforts he and his teams put into the Tour preparation outside of their use of performance enhancing drugs.

"What I wish would have happened, I wish kids from Plano and Glenwood Springs, Colorado, and Brooklyn and Montana, as young Americans, if we'd have gone to Europe and everybody was fighting with their fists, we still win," he said. "I promise you that.

"What did we say? We said we worked the hardest, had the best tactics, best team composition, best director, best equipment, best technology, recon the courses. All the things we said, we did. We left out a part, but we did all that stuff. Because now this one thing is part of the story doesn't erase all that. All that happened," Armstrong said. "If you just had this one thing and did none of that, you get last."

When Tirico asked Armstrong to recall why he and many of his US cohorts decided to use performance enhancing drugs, the Texan said it was their belief that they needed to dope to compete in Europe.

"That wasn't just a feeling, that was a fact," he said. "I don't want to make excuses for myself that everybody did it or we never could have won without it. Those are all true, but the buck stops with me. I'm the one who made the decision to do what I did, and it was ... I didn't want to go home, man. I was gonna stay.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"I told you earlier, I don't lay down. And it was the wrong decision, but laying down would have been giving up, going home.

"I knew there were going to be knives at this fight, not just fists. I knew there would be knives. I had knives, and then one day, people start showing up with guns. That's when you say, 'Do I either fly back to Plano, Texas, and not know what you're going to do? Or do you walk over to the gun store?' I walked to the gun store. I didn't want to go home.

Armstrong pushed back against claims that he was the ring leader who cajoled others into doping.

"There are a few things that are just not true about the story," he said. "I mean, there's a lot true, but this idea that myself or anybody forced or mandated or encouraged anybody else to cross that line, just isn't true. It's not true. Absolutely not true.

"We did what we had to do to win. It wasn’t legal. It probably wasn't the best decision, but look, we wouldn't have won had we not. But I wouldn't change a thing. I've said that three times. I would not change a thing," Armstrong said, pausing briefly between each word for emphasis.

"Most of my memories, my fondest memories – yeah, I could pick a few race highlights – but boy, I can tell you about the eight-hour day in the Pyrenees previewing Haute de Com in the pouring rain – pffft – the best," he said, tearing up as he spoke.

Armstrong also revealed his first encounters with performance enhancing drugs, a line he said he first crossed in 1991.

"I think I do," Armstrong said when Tirico asked if he remembered his first experience. "There are gateway drugs that maybe they weren’t banned, certainly weren’t detectable or tested for. The easiest way to think about it is, if you think it's going to help you, even if it's not detectable or banned, then you've crossed the line.

"It was probably '91, maybe, at an Italian stage race. And again, it's hard to differentiate, because I believe we weren't given anything banned, but the doctor walked in – and I was in the lead of the race, and I wanted to win the race – and he walked in and I said, 'Give me everything in the bag.' And he just laughed.

"But it was just probably some form of cortizone or, Armstrong said and then trailed off, failing to finish his through. "But the first time I took a legitimately banned substance was '93."

Thank you for reading 5 articles in the past 30 days*

Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read any 5 articles for free in each 30-day period, this automatically resets

After your trial you will be billed £4.99 $7.99 €5.99 per month, cancel anytime. Or sign up for one year for just £49 $79 €59

Try your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Eight-hour live broadcast for Sunny King Crit races on tap Saturday - North American Roundup

Lotte Kopecky to ride Giro d'Italia Women ahead of Paris Olympics

'I think it's possible' - Benoît Cosnefroy believes Mathieu van der Poel is beatable at Amstel Gold Race

Most Popular

By Laura Weislo April 08, 2024

By Barry Ryan April 08, 2024

By Jackie Tyson April 08, 2024

By Josh Croxton April 08, 2024

By Tom Wieckowski April 08, 2024

By Stephen Farrand April 07, 2024

By Dani Ostanek April 07, 2024

By Kirsten Frattini April 07, 2024

- Athlete Index

How Many Tour de France Races Did Lance Armstrong Win?

Lance Armstrong is the most famous cyclist in the history of the sport — but not exclusively for positive reasons. Fans originally loved him for his cycling dominance , most notably the Tour de France. But as time went on, Armstrong’s legacy took a major hit.

He became embroiled in a doping scandal that called into question all of the Tour de France titles he won — and there were a lot of them. So exactly how many times did Armstrong win the Tour de France? Let’s find out.

Lance Armstrong’s early cycling career

History.com recalls that Armstrong’s athletic career began as a triathlete, and he started competing professionally at age 16. Biking was his strongest of the three events and he started training with the U.S. Olympic cycling developmental team a year later.

In 1991, he won the U.S. amateur cycling championship and finished 14th in the road race at the Summer Olympics in Barcelona in 1992. The next year, he won 10 championships, including the World Road Championships — his first major race. That year was also when Armstrong competed in his first Tour de France, the sport’s premier race, and won Stage 8. It would still be several years before he would win his first Tour de France , however.

Lance Armstrong’s Tour de France dominance

Armstrong earned his first Tour de France title in 1999, and that would be the start of a dominant stretch for him at the iconic cycling race. He would go on to win the event for each of the next six years, as well, giving him seven straight championships in France from 1999 through 2005.

Those seven titles is a record for consecutive wins , in addition to total Tour victories for any individual cyclist. Some of the notable achievements he had during that seven-year stretch include:

- winning 22 individual stages

- winning 11 individual time trials

- leading his team to wins in three-team time trials

Armstrong retired after the 2005 race, but he returned to the sport professionally in 2009, when he finished third in the Tour. The following year, he finished 23rd, and he retired for good in 2011, as a 39-year-old.

Armstrong’s doping scandal

Lance Armstrong’s stepfather says he pushed the disgraced cyclist to be his best. “I drove him like an animal. That’s the only thing I feel bad about,” Terry said. https://t.co/5ZuBJ5mQeG — New York Daily News (@NYDailyNews) May 25, 2020

Like many athletes at the top of their sport, Armstrong faced accusations of using performance-enhancing drugs during the peak of his career. He always denied allegations and claimed to have passed hundreds of drug tests.

The situation changed in June 2012, however, when the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) charged Armstrong with doping up as early as at least August 1998. The two-year investigation uncovered that he was also part of a conspiracy to cover up his misconduct.

Armstrong continued to maintain his innocence, but he lost a federal appeal to have the charges dropped. That led to USADA banning the superstar from competitive cycling for life. The agency also disqualified all of his competitive results from Aug. 1, 1998 — essentially wiping out all 11 of his Tour de France titles.

A tarnished legacy

The doping scandal tarnished what was a positive legacy that Armstrong had established, not only in cycling but also for all of the charitable work he did through his Livestrong cancer awareness foundation.

The scandal caused Armstrong to step down as chairman of the charity. The Union Cycliste Internationale, the sport’s governing body, accepted USADA’s findings, and it officially erased Armstrong’s name from the Tour de France record books and upheld his lifetime ban.

After spending years denying that he had used performance-enhancing drugs, Armstrong came clean on Jan. 17, 2013, admitting in a televised interview with Oprah Winfrey that he had doped starting in the mid-’90s and extended all the way through his final Tour de France win in 2005.

Liverpool Coach Jurgen Klopp’s Approaching Departure Unsettling Players

IOC Takes Aim At ‘Friendship Games’ Russia Plans To Hold After 2024 Olympics

More Than 200,000 Condoms Will Be Handed Out At The 2024 Olympic Village

Scott Jenkins

Scott Jenkins has contributed content with a focus on Sportscasting. He also occasionally contributes content to MotorBiscuit like how to pronounce Audi and other riveting automotive topics.

Scott centers most of his writing for Sportscasting on the MLB and NFL, both of which he follows closely. (He’s even got fantasy teams for both leagues each year.) He’s more than halfway toward his goal of seeing a baseball game at all 30 MLB stadiums, and also checked off a bucket list item by attending a Texans-Packers matchup at Lambeau Field in 2016. (It was even complete with snowfall during the game, which was the icing on the cake.)

Timeline of Lance Armstrong's career successes, doping allegations and final collapse

ESPN's 30 for 30 "LANCE" directed by Marina Zenovich

Part 1: 9 p.m. ET Sunday on ESPN Part 2: 9 p.m. ET May 31 on ESPN Streaming: ESPN+ and ESPN Player (where available)

Lance Armstrong, a former American road-racing cyclist, helped elevate cycling to global popularity. His seven consecutive Tour de France victories, from 1999 to 2005, and his status as a cancer survivor made him one of the most iconic and revered athletes outside of the professional sports world.

Yet, throughout his career, he consistently faced allegations of doping -- particularly after he faced cancer and won the Tour de France a few years later.

His pro career began after winning a U.S. amateur national championship in 1991, but he placed last in his debut race -- the Clásica de San Sebastian in Spain. He won his first professional race the next year and entered his first Tour de France. He won a stage but dropped out and did not finish the race. He won the Thrift Drug Triple Crown in 1993, and his fame took off shortly thereafter.

Here's the timeline of Armstrong's career:

1996: Armstrong becomes the first American to win the La Flèche Wallonne, and he wins a second Tour DuPont. Despite being a part of only five days of the Tour de France, he goes on to participate in the 1996 Olympic Games, finishing sixth in the time trial and 12th in the road race. In October 1996, he is diagnosed with advanced testicular cancer that had also spread to his lymph nodes, lungs, brain and abdomen.

"I intend to beat this disease, and further I intend to ride again as a professional cyclist," he says when announcing his diagnosis. He undergoes his final chemotherapy treatment in December 1996.

1997: He establishes the Lance Armstrong Foundation (later renamed Livestrong) to support cancer patients and research. Armstrong also signs with the U.S. Postal Service's cycling team, which would later be rebranded under a different sponsor, Discovery Channel. The ubiquitous, yellow "Livestrong" bracelets from Armstrong's foundation would become a symbol for cancer patients and survivors everywhere.

1999: At age 27, after returning to professional cycling in 1997, Armstrong wins his first Tour de France.

"I hope it sends out a fantastic message to all survivors around the world," Armstrong says at the finish line in Paris. "We can return to what we were before -- and even better."

He is immediately peppered with questions about doping, denying all accusations. Despite testing positive for a corticosteroid, he shows a backdated prescription to avoid sanctions. The questions don't seem to matter; the comeback story and victory launches Armstrong to global stardom.

2000: Armstrong wins his second Tour de France, as well as a bronze medal in the time trial event at the Sydney Olympic Games. German Jan Ullrich, a chief rival of Armstrong's, wins the gold medal in the road race and silver in the time trials.

In Armstrong's autobiography "It's Not About the Bike ," he provides what becomes a famous quote: "Pain is temporary. It may last a minute, or an hour, or a day, or a year, but eventually it will subside and something else will take its place. If I quit, however, it lasts forever."

2001: Armstrong wins his third consecutive Tour de France. His rivalry with Ullrich is at its peak. Ullrich never defeats Armstrong in the Tour de France. He has more second-place finishes than any other racer.

2002: Armstrong wins his fourth consecutive Tour de France. French authorities simultaneously conclude a two-year investigation into the U.S. Postal Service team, but the investigation finds no use of performance-enhancing drugs.

2003: He wins the Tour de France again, for the fifth time. "This was my hardest win -- we dodged some bullets. It was a rough year at the Tour and I don't plan to make the same mistakes twice. But my win feels more satisfying, more than the others because of that. The crashes and near-crashes take it out of you," Armstrong says at the finish.

More: How to watch 'LANCE'

2004: Armstrong wins a record-setting sixth Tour de France.

2005: At age 33, after winning a seventh Tour de France, Armstrong retires to spend more time with his family. French newspaper L'Equipe reports blood samples retested from a 1999 race show evidence of blood doping that year, but Armstrong again denies the allegations.

"If you consider my situation: a guy who comes back from arguably, you know, a death sentence, why would I then enter into a sport and dope myself up and risk my life again? That's crazy," Armstrong tells CNN. "I would never do that. No. No way.

2009: After announcing his return to cycling, saying he hoped to "raise awareness of the global cancer burden," Armstrong finishes third in the Tour de France, his first race back from retirement. He also joins the RadioShack team, with intentions to again compete in the 2010 Tour de France.

2010: At the Tour Down Under, Armstrong makes his 2010 race debut, finishing 25th out of 127. At the Vuelta a Murcia in Europe, he finishes in seventh place overall, before pulling out of a handful of other races due to bouts with gastroenteritis. After a crash in the Tour de California, he places second in the Tour of Switzerland and third in the Tour of Luxembourg. In the 2010 Tour De France, which he had said would be his final, he finishes in 23rd place. However, Team RadioShack wins the team competition thanks to Armstrong's contributions.

At the same time, American cyclist Floyd Landis, who was Armstrong's teammate for two years and won the 2006 Tour De France, admits he used performance-enhancing drugs. In emails to U.S. and European cycling officials, Landis says he began doping in 2002 -- his first year alongside Armstrong, who again denies the allegations against him, saying in May: "It's our word against his word. I like our word. We like our credibility. Floyd lost his credibility a long time ago."

Landis also accuses other U.S. Postal Service teammates of doping, in addition to Armstrong, and agrees to cooperate with federal officials investigating the allegations.

2011: Armstrong again announces his retirement from competitive cycling in February, at age 39, to focus on family and his cancer foundation. But the walls obscuring his past use of performance-enhancing drugs are cracking. Two other U.S. Postal team members come forward acknowledging their own PED use and further implicating Armstrong.

2012: Federal prosecutors drop their criminal investigation against Armstrong and the U.S. Postal Service team in February, with no charges filed. However, the United States Anti-Doping Agency accuses Armstrong of doping and trafficking of drugs in June. In October, the USADA formally charges him with using, possessing and trafficking banned substances and recommends a lifetime ban. In choosing not to appeal the findings, Armstrong is stripped of all of his achievements from August 1998 onward, including his seven Tour de France titles. Armstrong still publicly denies the use of performance-enhancing drugs.

2013: In a January interview with Oprah Winfrey , Armstrong finally admits to doping during each Tour de France win from 1999 to 2005.

"This story was so perfect for so long. It's this myth, this perfect story, and it wasn't true," Armstrong tells Winfrey.

"I viewed this situation as one big lie that I repeated a lot of times, and as you said, it wasn't as if I just said no and I moved off it."

The Associated Press contributed to this story.

Crazy Stat Shows Just How Common Doping Was In Cycling When Lance Armstrong Was Winning The Tour de France

Even after Lance Armstrong finally came clean and was banned from cycling for life, many still defend the (unofficial) 7-time Tour de France champion.

The biggest argument for Armstrong is the belief that all riders were doping.

We have known for a while now that a lot of cyclists were doping. A recent breakdown of the extent of the "EPO Era" (named for the most common drug, Erythropoietin) shows the "everybody was doing it" defense may not be that far off.

Teddy Cutler of SportingIntelligence.com recently took a an excellent and detailed look at all the top cyclists from 1998 through 2013 and whether or not they have ever been linked to blood doping or have links to doping or a doctor linked to blood doping.

Related stories