Thanks for visiting! GoodRx is not available outside of the United States. If you are trying to access this site from the United States and believe you have received this message in error, please reach out to [email protected] and let us know.

- Open access

- Published: 19 April 2023

“But at home, with the midwife, you are a person”: experiences and impact of a new early postpartum home-based midwifery care model in the view of women in vulnerable family situations

- Bettina Schwind 1 , 2 ,

- Elisabeth Zemp 1 , 2 ,

- Kristen Jafflin 1 , 2 ,

- Anna Späth 1 , 2 ,

- Monika Barth 3 ,

- Karen Maigetter 1 , 2 ,

- Sonja Merten 1 , 2 &

- Elisabeth Kurth 1 , 2 , 3

BMC Health Services Research volume 23 , Article number: 375 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1949 Accesses

Metrics details

Postpartum home-based midwifery care is covered by basic health insurance in Switzerland for all families with newborns but must be self-organized. To ensure access for all, Familystart, a network of self-employed midwives, launched a new care model in 2012 by ensuring the transition from hospital to home through cooperation with maternity hospitals in the Basel area. It has particularly improved the access to follow-up care for families in vulnerable situations needing support beyond basic services. In 2018, the SORGSAM (Support at the Start of Life) project was initiated by Familystart to enhance parental resources for better postpartum health outcomes for mothers and children through offering improved assistance to psychosocially and economically disadvantaged families. First, midwives have access to first-line telephone support to discuss challenging situations and required actions. Second, the SORGSAM hardship fund provides financial compensation to midwives for services not covered by basic health insurance. Third, women receive financial emergency support from the hardship fund.

The aim was to explore how women living in vulnerable family situations experienced the new early postpartum home-based midwifery care model provided in the context of the SORGSAM project, and how they experienced its impact.

Findings are reported from the qualitative part of the mixed-methods evaluation of the SORGSAM project. They are based on the results of seven semi-structured interviews with women who, due to a vulnerable family postpartum situation at home, received the SORGSAM support. Data were analyzed following thematic analysis.

Interviewed women experienced the early postpartum care at home, as “relieving and strengthening” in that midwives coordinated patient care that opened up access to appropriate community-based support services. The mothers expressed that they felt a reduction in stress, an increase in resilience, enhanced mothering skills, and greater parental resources. These were attributed to familiar and trusting relationships with their midwives where participants acknowledged deep gratitude.

The findings show the high acceptance of the new early postpartum midwifery care model. These indicate how such a care model can improve the well-being of women in vulnerable family situations and may prevent early chronic stress in children.

Peer Review reports

Based on evidence that lifelong health and human development are strongly influenced by experiences during the first years of life, early childhood interventions are increasingly the focus of research and policies [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Interventions during this period are found to be more effective and less costly than later efforts [ 3 ], and especially children in vulnerable family situations seem to profit from early interventions. Studies show in particular, that early chronic stress and its long-term consequences can be mitigated [ 6 ]. Evidence suggests that parents, caregivers, and families need support for providing responsive, nurturing care and protection for young children so that they may achieve their developmental potential [ 3 , 7 ]. Programs designed to meet the needs of families in difficult circumstances lead to enhanced parental resources and thereby better outcomes for children [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ].

Positive effects on developmental outcomes have been documented for three types of family support and strengthening: quality services, support, and skills building [ 3 ]. However, studies [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ] have shown that especially psychosocially and economically disadvantaged families have limited access to postpartum care at home and use the available services less frequently. Midwives, due to their immediate access to vulnerable families, may therefore be key actors for early prevention, i.e. the early assessment and support of families with, or expecting an infant whose living situations are overstraining their capacities to cope [ 19 , 21 ].

Only a few, mostly Scandinavian, studies have addressed the perspective of parents receiving postpartum home-based care by midwives, and research on the impact of such care on infants and their families is still scarce. A Swedish study on first-time parents’ experiences of home-based postpartum care after early hospital discharge showed that midwives took a supporting role and strengthened parents’ self-confidence [ 21 ]. In a Norwegian study on women’s experiences of home visits by midwives in the early postpartum period, three central themes, relational continuity, postpartum talk, and vulnerability emerged [ 22 ]. Specifically, relational continuity with a midwife appeared as a crucial part of care, as expressed by a cited quote “postpartum care provided by a named midwife”. The importance of relational continuity in care was supported by a study from the UK that linked care across pregnancy, birth, and new motherhood with improved health outcomes for women and babies in socially disadvantaged and diverse communities [ 23 ]. An Australian home visit program for vulnerable families in disadvantaged areas also improved clients’ parenting skills and well-being, increased participation in community networks, and access to support services [ 24 ]. In Sweden, parents in vulnerable situations who received extended home visits reported improved parenting skills and confidence in discussing problems with professionals [ 25 ], especially fathers with migration histories who benefited equally through home visiting programs [ 26 ]. Furthermore, a German study applying a longitudinal mixed-method design investigated the effects of family midwives in 734 vulnerable families in Sachsen-Anhalt [ 27 ]. Results showed an increase in mothers’ skills in three areas: childcare, self-help/organization of family life, and searching for and accepting external help.

Because the literature so far has largely focused on the context of extended home visiting programs and outcomes for families in vulnerable situations [ 25 , 26 ] and was less concerned with experiences of families in vulnerable situations with very early home-based midwifery care and its impact, these issues were addressed in a Swiss study.

In Switzerland, early home-based postpartum care is mainly provided by independent midwives and family nurses [ 18 ]. Organizing postpartum care at home before birth is usually the responsibility of the pregnant woman and/or her relatives. Basic insurance covers 10–16 regular home visits by an independent midwife over 56 days. Little is known about the practices that go beyond standard care. Several local midwifery networks guarantee a seamless transition for all mothers and newborns from the hospital to the home setting [ 28 , 29 ]. These networks coordinate a postpartum care pathway in collaboration with maternity hospitals, independent midwives, and other maternal and child health care providers [ 30 , 31 , 32 ]. They assure that all women who give birth in the collaborating hospitals receive standardized care in that a midwife comes to their homes after hospital discharge and ensures further care. A first evaluation study in Switzerland suggested a great value of organized, guaranteed postpartum outpatient care by a midwifery network, especially for socially disadvantaged families [ 16 ]. It appeared that the accessibility and reliability of the midwives were crucial to women. The midwife network not only eased the burden on families and reduced stress, and for many women, the midwife evolved into an important reference person and was recognized as a cultural mediator by women with migration history.

In the Basel area, a Familystart network model has been running since 2012. Due to the guaranteed access to postpartum home care, midwives regularly visit disadvantaged families who may have fewer resources to organize postpartum care themselves, yet need support beyond services covered through basic health insurance. Set up in late 2018, the project “SORGSAM – Support at the start of life” aimed to offer vulnerable families improved assistance in dealing with complex postpartum situations [ 33 ]. The SORGSAM project supports independent midwife care activities for families in situations of stress and risk in three ways: first, midwives have access to first-line telephone support (7 days a week) to discuss challenging situations and required actions with a midwife specialized in psychosocial care [ 33 ]; second, the SORGSAM hardship fund provides financial compensation to midwives for services not covered by basic health insurance, e.g. for their time and costs in emergencies or for coordinating inter-professional services; and third, women may receive financial emergency support from a hardship fund.

We specifically aimed to investigate how women in vulnerable family situations experienced early postpartum home-based care by independent midwives provided in the context of the SORGSAM project, and how they viewed the impact of obtained care.

The study and this report were conducted following the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) [ 34 ]. The research team of the SORGSAM evaluation consisted of an interdisciplinary team dealing with society and health care in Switzerland anchored at the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, University of Basel [ 35 ]. Ethical approval by the Northwest Switzerland Ethics Committee was obtained before the start of the study (BASEC 2019–02030), and in an amendment during the COVID pandemic concerning the conduction of zoom interviews and directly contacting the families through the caring midwife.

Research design

This article reports findings from the qualitative part of the mixed-methods evaluation of the SORGSAM project in the area of Basel, Switzerland [ 35 ]. It is based on the results of semi-structured interviews with women in a vulnerable family situation in the postpartum period who experienced home based support from a Familystart midwife. The midwife made use of the SORGSAM support, including coaching/counseling by a specialized midwife and financial support from the SORGSAM hardship fund.

Open-ended, narrative-generating interview questions were developed in consultation with the research team and included three thematic blocks: (1) perception of the postpartum situation, (2) perception of the midwife’s care, and (3) perception of the current situation. Towards the end of the interview, participants could talk freely about topics that were not previously addressed but were important to them. An additional document shows the interview guide in detail (additional file 1). For the purpose of publication the guide was translated from (Swiss) German into English.

Sampling and recruitment

Criterion-based maximum variety sampling was used to select participants based on two available SORGSAM routine documentations, namely: (1) reports of the SORGSAM reimbursement from the hardship fund and, (2) reports of provision of first-line telephone support provided by a specialized midwife for colleagues encountering complex family situations. The criteria consisted of poverty, migrant history, single parent, health, and/or psychosocial stressors to maximize the diversity of complex family situations. Women were eligible to participate if they received care from a Familystart midwife who requested SORGSAM support in 2019. Individuals with severe mental illness, and/or receiving support from a midwife who were not Familystart members, and/or having language barriers were excluded. The selection based on the sampling criteria was documented, discussed, and validated by the team.

Eligible participants were approached by their midwives and informed about the study. When they were interested, the informed consent packages were sent via mail. They had sufficient time to read through the documents, clarify questions and consider whether they wanted to participate in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before the interview.

Among 55 eligible participants, nine agreed on a contact date for an interview, whereas 32 refused to participate or did not react; four persons showed insufficient language skills for interviewing, and 10 could not be reached. Two participants did not attend the agreed appointment due to the illness of a family member. As they were no longer reachable afterwards, this was considered as a withdrawal from participation. Once seven interviews were completed, recruitment had to be suspended due to the financial constraints of the project.

Data collection

Between February and July 2020, a senior researcher with a background in health and social sciences conducted seven interviews in the area of Basel in the German language. Each participant was free to choose the place of the interview. The first interview was conducted in February 2020, face-to-face in a café. Due to the increasingly tense pandemic situation, all subsequent interviews were conducted virtually via Zoom. The virtual approach appeared to be convenient for participants, as they did not have to find childcare for their children. All interviews were audio-recorded and lasted approximately one hour. The semi-structured interview method with open-ended questions allowed delving into participants’ perspectives so that women could talk freely about their experiences. Observations on the research process including the pandemic situation were noted in a reflexive diary by the interviewer.

Data analysis

After transcription of the interviews data were analyzed following Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis [ 36 , 37 ], a method designed for researching the views and experiences of research participants. The qualitative data analysis software package MAXQDA 2018 was used to support the analysis steps for coding following thematic analysis [ 36 , 37 ]. These included familiarization with the data (step 1), assignment of preliminary codes (step 2), search for preliminary themes (step 3), review and definition of themes (steps 4 and 5) and provide a written record (step 6). At a stakeholder workshop, consisting of 12 participants, the themes identified through the analysis were presented, revisited, discussed, and validated. No themes were corrected or determined to be missing. Based on the results of the analysis, a thematic model was jointly developed by the research team that formed the basis of the results section.

Participants

Of the seven participating women, five had a migration history (see Table 1 ). One participant was of Swiss nationality, and one woman was a cross-border commuter living in Germany. Their ages ranged from 23 to 44 years. Four women had a tertiary education and three had attended primary school. At the time of the interviews, only one woman was employed (100%), whereas two reported unemployment status and four reported not working and currently not seeking paid work. Four women were married; three were single or living alone. The partners of the four married women worked full-time.

Research findings

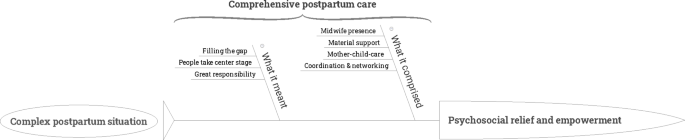

Three themes emerged from the analysis of the interviews, each containing several sub-themes and respective codes:

complex postpartum situation,

comprehensive postpartum care, and

psychosocial relief and empowerment.

The themes were grouped into a thematic model as shown in Fig. 1 , displaying midwife care and its perceived effects on women. They emerged from the accounts of the women, who found themselves in “complex postpartum situations” at home. Women described the “comprehensive postpartum care” by explaining “what it comprised” and “what it meant” to them. They indicated that the care received resulted in their “psychosocial relief and empowerment”. In the following, the three emergent themes are consecutively described:

Thematic model

Theme 1: complex postpartum situation

Women described challenging situations at home. Four sub-themes became apparent, including the aspects: “health situation”, “social situation”, “psychosocial situation” and “financial and material situations” (see Fig. 2 ).

Theme “Complex postpartum situation”

Specific to the present study, however, was that the postpartum situations were considered complex, due to the intersection of health challenges of mother and/or newborn, but also the precarious social and financial situation, partly with experience and/or fear of violence as the following example shows:

“At the beginning, it wasn’t easy,…after the birth I had problems with my leg, I could not walk properly…and I am overweight…and I am here alone, without family. I had problems with my boyfriend at that time and with my boyfriend’s father, yes, and I have another child…and she was kidnapped when she was one year old, and the problems plus my fear that my new child would also be kidnapped, that made my life quite difficult.“ (Interview 3).

Theme 2: “comprehensive postpartum care”

Women reported how they experienced the care provided by midwives as shown in Fig. 3 . Therewith, the sub-themes “what it comprised” and “what it meant” emerged from the data, each including different thematic aspects that added up to what was understood as “comprehensive postpartum care”.

Theme “Comprehensive postpartum care”

Sub-theme “what it comprised”

The sub-theme “what it comprised” is composed of the thematic aspects of “mother-child-care”, “midwife presence”, “coordination and networking”, and “material support”. “Mother-child-care” included ordinary aspects of midwifery care in the postpartum situation, such as bathing the newborn, checking wound sutures, breastfeeding support, assuring weight gain of the newborn, and checking for emotional distress and/or anxiety/depression. To focus on the three further thematic aspects that go beyond ordinary midwifery care, mother-child care was not elaborated on in more detail.

“Midwife presence” emerged as a very central element in the women’s narratives. Women described the feeling that midwives were always there for them and their families, and even in case of emergencies:

“She was always there when we needed her, always…” (Interview 1) . “When I need help, when I write, she always calls.“ (Interview 4) . “She really helped me and never minded, even if it was raining.“ (Interview 6) .

Thus, the reachability and availability of midwives appeared as a crucial aspect to ensure emotional, parental and material support to promote feelings of security - especially in case of uncertainties at home. This was the case for example, when women were worrying about how to deal with the newborn, how to feed the baby, or if there were no nappies due to financial constraints, but also if they were fearing violence. This kind of accessibility and reliability to medical, social, and emotional support appeared especially important for women who felt challenged having to navigate through the health system and therefore they were able to receive the help at the time they needed it:

“[Doctors] were often not available,…nobody came by…and I was…also not so well organized, but there was…a big gap…I somehow think that the midwifery care was a very personal, individual care.” (Interview 6) .

The low threshold of accessibility and reliability, e.g. to text midwives and receive an answer via SMS, appeared as a supportive cornerstone. However, it was not only the perceived reachability and availability of the midwife that was important for the women, but also that the midwife’s presence at home was felt to be without any apparent time pressure:

“I think it was important for us that she was simply there, that she always took her time, sometimes she was even there for two hours and didn’t look at the clock, … that she wasn’t in a hurry, but that she took her time and asked three more times, with, um, is it everything now, is there anything else?… Yes. That was good.“ (Interview 7) .

The quotes suggest that the women perceived an unconditionality in the midwifery care received, presumably creating feelings of trust and being taken seriously. The women also reported that the midwife was not only there as a contact and care person for them and the newborn, but also for the whole family, as evidenced in the next quote of a woman who experienced stillbirth:

“Yes, and I liked the fact that she looked after us as a family and not just after me as a woman, because there wasn’t much to control in terms of the baby…that the family was looked after, that the brother was looked after, asked how he was dealing with it, right? Things like that.“ (Interview 7) .

Furthermore, one woman described a situation of domestic violence, in which her midwife provided her with emergency help:

“Because once I was in a situation there, I couldn’t call the police or get help somehow, then I wrote to her and she got the police for me, you know?…I didn’t know what to do, I didn’t have a car, my baby was sick…so, or violence,…something happened to him,…I couldn’t go to the hospital right away, then she helped me, even though it wasn’t working time, or, so she came with her car, she helped me go to the hospital”. (Interview 6).

Overall, the thematic aspect of “midwife presence” indicates that the interviewed women appreciated the midwife’s accessibility, availability, and continuity of care without time pressure. They described midwives as “carers” for their families and as trusted confidants - especially for themselves, and who were called in during emergencies such as in cases of domestic violence.

Women interviewed reported on the different forms of “coordination and networking” functions of midwives. They described midwives’ work as mediating, organizing, and coordinating services and institutions to improve complex domestic situations. Midwives were reported to have organized parent-child counseling, breastfeeding counseling, social services, and home care services for domestic help (e.g. the Red Cross). Women also indicated that midwives contacted various doctors, police, and cantonal offices. The women interviewed described this central interface function:

“And, she gave me a lot of contacts…la Leche ligue, and now I’m a member and other mothers…that was very good.“ (Interview 1) . “So yes, so I was sad, so not good, since the birth and yes, the midwife, has found such a person…a therapist, and I had gone there with (child).“ (Interview 2) .

The range of this interface network function went from quick fixes to complex coordination activities as illustrated in the following example:

“At the beginning, she just put away the toys…and then afterward she…asked at Spitex [home care service for domestic help], can someone cook there? And, do a bit of housework and a bit of cleaning. And they said, no, they just do the flat a bit. And then she …first asked in Canton X because the children were born there and then,…but I live in Canton Y…then she had asked if she could organize someone from the Red Cross if they would take over something. Then they said, no, have to ask Canton Y. She called Canton Y, and then they understood my situation, then Canton Y just took over and also organized it further.“ (Interview 4) .

The midwifes’ networking activities included professional groups or organizations or institutions, and networking among mothers. Women with a migratory background who felt or were alone mentioned this positively and emphasized the important role of their home-country language in feeling understood:

“Because the [other mothers] speak Spanish and it was…my midwife was the midwife of this mother and my midwife, and [she said] I know other Spanish mothers - do you want their phone number? And she asked for the other mother too, and we made contact and we are friends.“ (Interview 1) .

Beyond midwife’s care and coordination support, women also described to have received material support, ranging from getting diapers to breast pumps to children’s clothes:

“If I need some clothes or something bed and things like that…if I need that…all the organizing…for cot or something, you know…I didn’t buy much and she also tried to get [this] organized. That was also…great, how do you say, yeah because everybody thinks only about one health side, the other side…she helped on both sides, yeah.“ (Interview 4) .

Women also received information and knowledge about where to obtain assistance in case of financial bottlenecks, e.g. where to get second-hand clothing and toys free.

Sub-theme “what it meant”

The sub-theme “what it meant” is composed of the thematic aspects of “filling the gap”, “people take center stage”, and “great responsibility”. The interviewed women described the overall postpartum care received not only as extensive, but also contrasted it with the care provided by medical doctors where they described midwives as “filling a gap” in the care system:

“With the doctors a bit like that…so, ‘I do that, that’s my problem…They don’t see a collective problem…and he just looks at the child. I find the medicine a bit separate…The midwife! it’s in the middle…she’s worked with both of us so far, so that’s so her job, she’s doing great.“ (Interview 2).

Women also described as being seen and treated by the midwife as a person, which also included much of their emotional situation.

“Because in hospital you are a patient with blood pressure, this and that and the values, but at home, with the midwife, you are a person with feelings and yes…that was a completely different approach. (Interview 7).

“I mean, it isn’t just the baby what the midwife works on…she helped me in other ways too.” (Interview 6).

Women also emphasized the great responsibility that this entails for the midwife:

“I felt that the midwife took more responsibility than she…had to.” (Interview 2) .

The quotes highlighted that women understood the care they received as comprehensive postpartum care that occurred at the interface between somatic and psychosocial care, and as interconnecting between professions and institutions. This meant for women that a gap in postpartum care was being filled, which they described as a great responsibility for midwives.

Theme 3: Psychosocial and emotional impact

The theme “psychosocial and emotional impact” developed from the data, covering the sub-themes “psychosocial relief”, “empowerment”, and “feeling grateful”, see Fig. 4 .

Theme “Psychosocial relief and empowerment”

Sub-theme “psychosocial relief”

What appeared as important for the interviewed women was that the received care was experienced as personal and emotional, and was labeled “human”. This aspect was particularly memorable for the interviewed women as they described the midwife’s care as supporting “physical, emotional recovery and relaxation” which helped them to relax:

“Helped me to relax a bit, because I was always very stressed and so (groans), and I…was breastfeeding (child),…so and she helped me to relax a little bit like that, and to breathe…and to get a little bit, yeah, calm, so that was…that was good”. (Interview 2).

“It all sounds like a commercial now…she couldn’t have done it better. She was also great interpersonally…That really supported me insanely.“ (Interview 4) .

The quotes indicated how women no longer felt alone due to the midwife’s presence and the interpersonal relationship, which supported women in dealing better with the new postpartum situation. They also stated how important it was for them to be able to “build and experience trust” with the midwife:

“I could trust her…that was important for me, that I could trust her, I could also talk so openly with her.” (Interview 6).

“She was actually my contact person number one and I think that was actually almost the most important thing.” (Interview 5).

The quotes underlined the importance of interpersonal closeness and trust so that women could open up and thereby feel relief and relaxation at the same time. They experienced a reduction of concerns and stress.

Sub-theme “empowerment”

From the different interview texts, it became manifest that the women not only felt relieved by the comprehensive midwifery care but that they also felt strengthened to survive the difficult life situations. The following quotes expressed how women felt to “become stronger and courageous”, also through “competence and knowledge enhancement” on where and how they could obtain help:

“That made me a bit strong,…um, I don’t know, is there this expression in Switzerland or German, that you can stand on your feet? [Yes. That was like that for me. So I know where, where I can go for help if anything happens…yeah…And that made it a bit easier, the situation made that, became a bit easier. It’s not easy, but it has become easier.“ (Interview 3).

“During the birth or after the birth a little bit so, just, like nice, so, just, so, just, um, agreeing with the situation or so a little bit braver, we can help, we can organize something, not worrying or so a little bit, yeah, so just with the others, just helping would be nice (laughs)” (Interview 4).

The midwifes’ presence provided security and confidence to better deal with and accept the current situation so that women described, “feeling good and safe”:

“So yeah, now it’s, um, now it’s really like, I hope, I don’t know, but like…right now I’m somewhere good with my baby” (Interview 6).”

Through these different forms of emotional and social self-empowerment, they described feeling “good and safe” again.

Sub-theme “feeling grateful”

Starting from the question about changes compared to the current situation, women made statements that indicated, in retrospect, a positive assessment and gratitude for the care and support they had received that still lasted at the time of the interview. This was exemplified in interview 6:

“She just…helped a lot, a lot, and I’m very grateful that she kind of saved my life, twice.“ (Interview 5) .

This gratitude was rooted in the comprehensive support, which was described as “coming from the heart”, as it was formulated in interview 5:

“She helped me in many ways, you know…in clothes, in healthy, in emotional, she was … a person…she did so many things with me, helped…she did it from the heart.“ (Interview 5) .

“She has been like a god when she asked like that and organized the help like that, that’s, yeah, that’s a big help, you know? I won’t forget that.“ (Interview 3) .

The quotes illustrated both the gratitude towards the midwife as well as her central role, possibly because the interviewed women have had little support in their vulnerable family situations.

Our study showed that women living in vulnerable family situations and who were cared for in the context of the SORGSAM project, evaluated the early postpartum home-based midwifery care as a relieving and strengthening experience. Midwives not only ensured the mother and child’s postpartum health but also coordinated further care and opened up access to appropriate community-based support services. Mothers described the received care as comprehensive, personal, and reliable, allowing them to better deal with complex family situations. They reported that it eased the burden of social isolation, made it easier to talk about challenges such as fears and violence, and led to de-escalation in situations of tension. They expressed how receiving care resulted in stress reduction, increased resilience, and empowerment and that it enhanced their mothering skills and parental resources.

Our study highlights that the benefits of early home-based midwifery care for women in precarious family situations are rooted in the close and trusting relationship with their midwife, resulting in deep gratitude for this experience. Participating women described their complex life situations and commented in detail on the supportive, comprehensive midwifery care they experienced. They reported that they felt strengthened by the continuous and easily accessible midwifery care during the uncertain phase of the early home transition, in terms of health, as well as social and emotional aspects.

”Midwife presence”, provided them with emotional and material equipment support, and supported them in accessing different community networks. This kind of supporting role by the midwife was described before, as in the study of Johansson in healthy families after early hospital discharge in Sweden [ 21 ], or in a recent Swedish study in families with low socioeconomic status, where the support of midwives was considered reassuring [ 25 ]. In our study, this aspect appeared to be very pronounced. Women expressed the impact of receiving midwifery care by memorable wordings such as “saved my life twice, somehow”, or “otherwise I would be dead”. Women included in the study used metaphors such as “angel” or even “God” to describe the midwives. Similar expressions by postpartum women have also been documented in a recent study in Zurich involving socially disadvantaged women [ 16 ]. These expressions may reflect, on the one hand, the hardships experienced in vulnerable situations and, on the other hand highlighted that support in such situations was perceived as particularly helpful. According to the Swiss study by Grylka-Baeschlin et al., midwives who provided postpartum care evolved into important support persons, and, among women with migration history, in that the midwives became cultural mediators [ 16 ]. Relational continuity has also been described as a crucial part of midwifery care in the review of Dahlberg [ 22 ], and it was linked to improved outcomes [ 23 ]. The high accessibility and reliability of the midwife appeared very central also in the other recent Swiss study [ 16 , 38 ]. The building of trust probably occurred fully only if midwives could be immediately present in the homes of new mothers, recognize situations of psychosocial and emotional emergency, and act as first professional responders. As the mothers in our study reported, bridging to further help systems was a further, crucial part of care, and networking helped prevent social isolation. These findings are in line with those of a Swedish and an Australian study, that reported an increased knowledge of societal and local resources for families [ 26 ], increased access to support services, and improved participation in community networks [ 24 ].

Our findings exemplify that stress in the very first phase of life can be mitigated by early midwifery home care even in very difficult social situations. Mothers described impacts on themselves in terms of calming down, de-escalation of situations, strain relief, and stress reduction. Grylka-Baeschlin et al. found that home-based postpartum care eased the burden on families and reduced stress [ 16 ]. This should, in turn, positively impact mothering skills, the mother-infant relationships, and the further development of the children, as it has been shown, that a high level of parenting stress is associated with a poor dyadic co-regulation between mother and child [ 39 ]. “Midwife presence” seems to be helpful for what is called a “co-regulation in therapeutic processes” resulting in mitigating high-stress levels in the mother [ 40 ], which can be seen as a key factor for preventing/decreasing early chronic stress in the child.

A key finding of our study relates as to how early midwifery home care strengthened self-confidence and resilience, including knowledge and assurance on access to further support services. Women described that they felt to be seen and treated as “a person”, how they became ‘stronger and more courageous’. They furthermore reported increased competencies and knowledge of where to get help, and impressively described increased resilience. These findings postpartum are in line with several studies reporting that home-based early midwifery care had positive effects on parenting and self-confidence [ 21 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 38 ]. The mothers in our study also reported to have more confidence in that they now knew where and how to get the help they needed. It may thus be understood as a prerequisite for the promotion and prevention of mother and child health, including mental health aspects.

Limitations and strengths

The positive picture given by postpartum women may be too optimistic due to a participation bias. Indeed, enormous efforts were needed for the recruitment of participants, and among the 55 eligible families, around half did not react to the study invitation or refused to participate. Ten women had no valid address, and four women had difficulty mastering the German language and this appeared to be too limited to participate in an interview. In particular, no woman could be recruited who was involved in a child welfare issue. Among the participants, six women had a migrant history, thus, migrant women were well represented.

Saturation is usually accepted as the criterion for the number of interviews conducted. Saturation is described to be reached - depending on the research questions and study population - at approximately 12 to 20 interviews, but the basic elements for a thematic ordination are reported to be already identified at six interviews [ 41 ]. Even though the sample was small by using a maximum variety sampling, we have succeeded in mapping the diversity and complexity of care for vulnerable postpartum family situations. The data collection was also quickly adapted to the pandemic measures and was carried out digitally. This actually was a simplified access for women in vulnerable family situations, as they were not burdened by the additionally needed childcare.

Furthermore, the information provided by the interviewed women was very congruent with the information in the midwives’ case documentation [ 35 ]. In these files, psychosocial problems were recorded in approximately 60% of cases, and midwives noted that they could contribute to a more stable situation, by lowering tension, exhaustion, and stress, and they notably documented a positive course in most of the cases. The thematic mapping was conducted by the research team and validated at the stakeholder workshop. Although there was no systematic assessment of the impact on children in our study, the findings suggested that SORGSAM care might influence favorably on children’s well-being as several of the interviewed mothers explicitly reported improved breastfeeding, and two out of the seven interviewed mothers mentioned a decrease in the crying of their children.

In conclusion, our findings are supportive of a potential beneficial effect of postpartum midwifery care for the improvement of resilience and well-being of women in vulnerable family situations. Midwives appear to be important players in early childhood interventions with a comprehensive biopsychosocial approach breaching the interface of medical and psychosocial care. To allow midwives to make full use of their potential, it is necessary to install programs such as SORGSAM, which reimburse midwives for their coordinative services and give them access to a hardship fund enabling them to provide short-term financial support to families in acute need. Investing in midwifery services may be understood as a direct investment in earliest childhood interventions as described by Magistretti Meier [ 42 ] to prevent early chronic stress at early onset. The findings are suggesting that midwifery home care was a “door opener” for interprofessional coordinated early childhood support, strengthened parenting skills and self-confidence, and might alleviate early adverse childhood experiences, potentially reducing health care disparities and improving health equity. However, more studies are needed to quantitatively assess associations of midwifery home care with positive outcomes in mothers, and in particular, to assess and quantify its longer-term effects on the well-being of families, women, and particularly the development of children.

Data Availability

The datasets produced and analyzed in this study are not publicly available due to the confidentiality of the information, especially in a small region like Basel, Switzerland, as this is the only way to ensure the non-identifiability of individuals. Upon reasonable request, the anonymized data are available from the authors.

Shonkoff JP, Garner AS. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):232–46.

Article Google Scholar

Aboud FE, Yousafzai AK. Global health and development in early childhood. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:433–57.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Britto PR, Lye SJ, Proulx K, Yousafzai AK, Matthews SG, Vaivada T, et al. Nurturing care: promoting early childhood development. The Lancet. 2017;389(10064):91–102.

Richter L, Black M, Britto P, Daelmans B, Desmond C, Devercelli A, et al. Early childhood development: an imperative for action and measurement at scale. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(Suppl 4):e001302.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

World Health Organization. Nurturing care for early childhood development: a framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

Google Scholar

Thompson RA, Haskins R. Early stress gets under the skin: promising initiatives to help children facing chronic ddversity. The Future of Children. Prinction Brookings; 2014.

Richter LM, Cappa C, Issa G, Lu C, Petrowski N, Naicker SN. Data for action on early childhood development. The Lancet. 2020;396(10265):1784–6.

Walker AM, Johnson R, Banner C, Delaney J, Farley R, Ford M, et al. Targeted home visiting intervention: the impact on mother-infant relationships. Community Pract. 2008;81(3):31–4.

PubMed Google Scholar

Knerr W, Gardner F, Cluver L. Improving positive parenting skills and reducing harsh and abusive parenting in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Prev Sci. 2013;14(4):352–63.

Gertler P, Heckman J, Pinto R, Zanolini A, Vermeersch C, Walker S, et al. Labor market returns to an early childhood stimulation intervention in Jamaica. Science. 2014;344(6187):998–1001.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gardini ES, Schaub S, Neuhauser A, Ramseier E, Villiger A, Ehlert U et al. Methylation of the glucocorticoid receptor promoter in children: Links with parents as teachers, early life stress, and behavior problems.Development and Psychopathology. 2020:1–13.

Morrison J, Pikhart H, Ruiz M, Goldblatt P. Systematic review of parenting interventions in european countries aiming to reduce social inequalities in children’s health and development. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1040.

Renner I, Scharmanski S, Paul M. Frühe Hilfen – Wirkungsforschung und weiterer Bedarf. Hebamme. 2018;31(02):119–27.

DiBari JN, Yu SM, Chao SM, Lu MC. Use of postpartum care: predictors and barriers. J Pregnancy. 2014;2014:530769.

Wilcox A, Levi EE, Garrett JM. Predictors of non-attendance to the postpartum follow-up visit. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(Suppl 1):22–7.

Grylka-Baeschlin S, Iglesias C, Erdin R, Pehlke-Milde J. Evaluation of a midwifery network to guarantee outpatient postpartum care: a mixed methods study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):565.

Ruderman RS, Dahl EC, Williams BR, Davis K, Feinglass JM, Grobman WA, et al. Provider perspectives on barriers and facilitators to postpartum care for low-income individuals. Womens Health Rep. 2021;2(1):254–62.

Erdin Springer R, Iljuschin I, Pehlke-Milde J. Postpartum midwifery care and familial psychosocial risk factors in Switzerland: a secondary data analysis.International Journal of Health Professions. 2017;4(1).

Sann A. Familienhebammen in den Frühen Hilfen: Formierung eines “hybriden” Tätigkeitsfeldes zwischen Gesundheitsförderung und Familienhilfe. Diskurs Kindheits- und Jugendforschung. 2014;9(2):227–32.

Meier Magistretti C, Walter-Laager C, Schraner M, Schwarz J. Angebote der Frühen Förderung in Schweizer Städten (AFFiS). Kohortenstudie zur Nutzung und zum Nutzen von Angeboten aus Elternsicht. Luzern, Graz: Hochschule Luzern – Soziale Arbeit, Karl-Franzens Universität Graz; 2019.

Johansson K, Aarts C, Darj E. First-time parents’ experiences of home-based postnatal care in Sweden. Ups J Med Sci. 2010;115(2):131–7.

Dahlberg U, Haugan G, Aune I. Women’s experiences of home visits by midwives in the early postnatal period. Midwifery. 2016;39:57–62.

Homer CS, Leap N, Edwards N, Sandall J. Midwifery continuity of carer in an area of high socio-economic disadvantage in London: a retrospective analysis of Albany Midwifery practice outcomes using routine data (1997–2009). Midwifery. 2017;48:1–10.

Stubbs JM, Achat HM. Sustained health home visiting can improve families’ social support and community connectedness. Contemp Nurse. 2016;52(2–3):286–99.

Bäckström C, Thorstensson S, Pihlblad J, Forsman AC, Larsson M. Parents’ experiences of receiving professional support through extended home visits during pregnancy and early childhood - a phenomenographic study. Front Public Health. 2021;9:578917.

Tiitinen Mekhail K, Lindberg L, Burström B, Marttila A. Strengthening resilience through an extended postnatal home visiting program in a multicultural suburb in Sweden: fathers striving for stability. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):102.

Ayerle GM, Frühstart. Familienhebammen im Netzwerk Frühe Hilfen. Bundesministerium für Familie S, Frauen und Jugend, editor. Köln:Nationales Zentrum Frühe Hilfen; 2012.

Familystart. Support before and after birth - Near basel 2022 [Available from: https://familystart.ch/en .

Familystart Zürich [Website], Zurich. Familystart Zurich; 2020 [Available from: https://www.familystart-zh.ch .

Kurth E. FamilyStart beider Basel – ein koordinierter Betreuungsservice für Familien nach der Geburt. Hebammech. 2013;7/8:35–7.

Frey P, Reber SM, Krähenbühl K, Putscher-Ulrich C, Iglesias C, Portmann U, et al. editors. Bedarfsanalyse zur postpartalen Betreuung zeigt Lücken auf - FamilyStart Zürich bietet Lösung 2015.

Zemp E, Signorell A, Kurth E, Reich O. Does coordinated postpartum care influence costs? Int J Integr care. 2017;17(1):7.

Kurth E, Barth M, Loosli B, Ruffieux A, Lüscher U, Späth A, et al. Das Pilotprojekt «Sorgsam – Support am Lebensstart» unterstützt Hebammenarbeit im Frühbereich. Obstetrica. 2019;6:47–8.

Booth A, Hannes K, Harden A, Noyes J, Harris J, Tong A. COREQ (Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies) In: Moher D, Altman D, Schulz K, Simera I, Wager E, editors. Guidelines for reporting health research: a user’s manual Wiley; 2014. p. 214 – 26.

Zemp E, Schwind B, Jafflin K. Evaluationsprojekt SORGSAM 2019/2020, Schlussbericht. 2020.

Braun V, Clarke V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int J Qualitative Stud Health Well-being. 2014;9(1):26152.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Ayerle GM, Makowsky K, Schucking BA. Key role in the prevention of child neglect and abuse in Germany: continuous care by qualified family midwives. Midwifery. 2012;28(4):E469–77.

Azhari A, Leck WQ, Gabrieli G, Bizzego A, Rigo P, Setoh P, et al. Parenting stress undermines mother-child brain-to-brain synchrony: a hyperscanning study. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):11407.

Sossin MK, Charone-Sossin J. Embedding: co-regulation within therapeutic process: lessons from development: response to “co-regulated interactions: implications for psychotherapy … paper by Stanley Greenspan. J Infant Child Adolesc Psychother. 2007;6(3):259–79.

Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82.

Meier Magistretti C, Villiger S, Luyben A, Varga I. Qualität und Lücken der nachgeburtlichen Betreuung. Lucerne: Lucerne University of Applied Sciences; 2014.

Download references

Acknowledgements

A thanks goes to Alessia Kiener for her valuable support in the realization of the evaluation. We would also like to thank the participants, especially for their trust despite their emotionally challenging and stressful family situations.

Open access funding provided by University of Basel.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland

Bettina Schwind, Elisabeth Zemp, Kristen Jafflin, Anna Späth, Karen Maigetter, Sonja Merten & Elisabeth Kurth

University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

Midwifery Network, Familystart beider Basel, Basel, Switzerland

Monika Barth & Elisabeth Kurth

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Study conception and design were done by EZ, EK, and BS. MB recruited the participants. BS conducted the qualitative part of the mixed-methods-based SORGSAM evaluation. The results of the thematic analysis were jointly discussed and finalized by BS and EZ through the development of the thematic map. BS and EZ contributed to the subsequent draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Bettina Schwind .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

EK has a part-time position as the managing director and MB is a part-time co-worker of the Midwifery Association “Familystart” located in Basel. The authors BS, EZ, KJ, AS, KM, and SM declare that they have no competing interests. The Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute was commissioned to evaluate the SORGSAM project.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval, including an amendment due to the COVID pandemic, was obtained by the Northwest Switzerland Ethics Committee (BASEC 2019–02030). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Evaluation SORGSAM

: Interview guide with women experiencing vulnerable family situation postpartum at home

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Schwind, B., Zemp, E., Jafflin, K. et al. “But at home, with the midwife, you are a person”: experiences and impact of a new early postpartum home-based midwifery care model in the view of women in vulnerable family situations. BMC Health Serv Res 23 , 375 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09352-4

Download citation

Received : 28 December 2022

Accepted : 30 March 2023

Published : 19 April 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09352-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Early postpartum care

- Home visits

- Women’s experiences

- Vulnerable family situations

- Empowerment

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Women's experiences of home visits by midwives in the early postnatal period

Affiliations.

- 1 St. Olavs University Hospital, Department of Women's Health, Olav Kyrres gt. 17, 7006 Trondheim, Norway. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Department of Nursing Science and Center for Health Promotion Research, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway.

- 3 Department of Nursing Science, Midwifery Education, Faculty of Health and Social Science, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway.

- PMID: 27321721

- DOI: 10.1016/j.midw.2016.05.003

Objective: The aim of the present study is to gain a deeper understanding of women's experiences of midwifery care in connection with home visits during the early postnatal period.

Research design/setting: A qualitative approach was chosen for data collection, and the data presented are based on six focus group interviews (n: 24). The women were both primiparous and multiparous, aged 22-37, and lived with their partners. All participants had given birth at a maternity unit responsible for about 4000 births a year. The transcribed interviews were analysed through systematic text condensation.

Findings: The findings are reflected in three main themes: 'The importance of relational continuity', 'The importance of a postpartum talk' and 'Vulnerability in the early postnatal period'. When the woman had a personal relationship with the midwife responsible for the home visit she experienced predictability, availability and confidence. The women wanted recognition and time to talk about their birth experience. They also felt vulnerable in their maternal role in the early postnatal period and the start of the breast-feeding process.

Conclusions: It is important to promote relational continuity models of midwifery care to address the emotional aspects of the postnatal period. Women generally wish to discuss their birth experience, preferably with the midwife who was present during the birth. Due to the short duration of postnatal care in hospitals, the visit from the midwife a few days after childbirth becomes all the more important.

Keywords: Continuity of care; Home visit; Postnatal care; Postpartum talk.

Copyright © 2016 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

- Focus Groups

- House Calls*

- Midwifery / standards*

- Mothers / psychology*

- Patient Satisfaction*

- Postnatal Care / standards*

- Qualitative Research

Birth how you want to

You want to dance? Sleep? Shower? Eat? Your choice.

Birth in the water? On your bed? In the hallway? Your choice.

Birth with whom you want to

Partner. Doula. Sister. Mother. Children.

Whomever you want by your side, it's your home, it's your choice.

Birth where you want to

A house in the suburbs? An apartment? A farmhouse? A motorhome?

Have your baby in the comfort of whatever you call home.

About Homebirth

Planned homebirth with skilled midwives is safe for low-risk pregnancies.

- High rate of completed home birth (89.1%)

- High rate of vaginal birth (93.6%)

- High rate of completed vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC; 87.0%)

- Cesarean section rate of 5.2%

MANA stats

Women have the right to choose their maternity care provider and the location of their birth. They have the right to informed consent - full knowledge of risks and benefits before making decisions.

Certified Professional Midwives may legally practice in South Carolina so long as they hold a current state license.

Women and babies experience a natural, mutually regulating, hormonally driven process of birth - from the onset of labor through birth of the baby and placenta, as well as the establishment of breastfeeding and the development of mother-baby attachment - with appropriate support and protection from external interference.

Milbank Report

Meet the Midwife - Angela Springer, LM, CPM

I have given birth three times and though each birth experience was vastly different, they have something in common - I will never forget them. I would love for every woman to have a special and meaningful childbirth experience. My experiences many years ago first led me to lactation peer counseling and postpartum support. My passion to serve and empower women led me to become a birth doula and eventually a midwife. I am certified as a Certified Professional Midwife through the North American Registry of Midwives and hold a Midwifery Bridge Certificate. I am a Licensed Midwife in the state of South Carolina. I am certified in Basic Life Support for healthcare workers (CPR for adults and children) and the Neonatal Resuscitation Program (CPR for newborns). I serve as Vice President of the Palmetto Association of Licensed Midwives.

Meet the Midwife - Chloe Clauser, LM, CPM

I have always been passionate about nurturing and caring for women during their journey to motherhood. Being a mother of four myself, I have learned firsthand just how sacred the journey is each and every time. It is a life-changing event that has the ability to leave you feeling empowered and confident as you start your new journey with your baby. As I follow my calling in midwifery, I find my passion to serve women only growing. I am certified as a Certified Professional Midwife through the North American Registry of Midwives . I am a Licensed Midwife in the state of South Carolina. I am certified in Basic Life Support for healthcare workers (CPR for adults and children) and the Neonatal Resuscitation Program (CPR for newborns).

The Midwifery Model of Care

- Relationship - develop a trusting relationship with your midwife at every appointment

- Informed consent - make informed decisions for you and your baby

- Woman-centered - caring for your physical, emotional, and social well-being

- Family-friendly - include your spouse, significant other, children, or other support people

- Evidence-based - receive the latest, proven, unbiased information and maternity care

- Natural birth - experience an unmedicated, low-intervention, normal physiological birth

- Trauma-informed - expect safety, sensitivity, and support

Homebirth is an answer to the current “perinatal paradox” of doing more and accomplishing less.

Conventional maternity care in the United States spends far more per capita for maternity care than any other nation, and yet has higher rates of perinatal, neonatal, and maternal mortality. Disproved practices are in wide use, while proven beneficial practices are underused. Although most childbearing women and newborns in the United States are healthy and at low risk for complications, essentially all women who give birth in hospitals experience high rates of interventions with risks of adverse effects. Cesarean section is the most common operating room procedure in the country, accounting for 32% of all pregnancies even though the WHO is trying to reduce this rate since there is no evidence that the mortality rate improves when C-section rates rise above 10% .

Let’s do less and accomplish more!

Before Birth

- Holistic prenatal care

- Nutritional counseling

- Pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding education

- Midwife visits in the office

- Routine laboratory tests

- Two physician consult visits

- Anatomy scan ultrasound

- Homevisit at 36 weeks

During Birth

- Labor support in your home

- Eat and drink as you desire

- Water birth option

- Intermittent heart tone monitoring

- Trained to handle emergencies

- Birth in the position and location of your choice

- Natural delayed cord clamping

After Birth

- Newborn exam

- Three postpartum home visits

- Newborn metabolic screening

- Newborn heart defect screening

- Newborn hearing screening

- Mother and baby care for 6 weeks

- Lactation support

- Birth certificate and SSN filing

- 6-week postpartum office visit

Empowering Women Through Education

For a current class schedule, please message us or follow us on social media.

Birth Story Circle

A community gathering where everyone can share, learn, grow, and heal. This is a safe space to share your birth experience, hear from others, ask questions, and form friendships.

This gathering is free.

Pregnancy 101

This class covers everything you need to know about pregnancy including nutrition, body mechanics, tests and procedures offered in pregnancy, and how to deal with common complaints in pregnancy.

This 2.5 hour class is $60.

An interactive and informative childbirth class covering the anatomy and physiology of labor, stages of labor, comfort measures, birth options, and immediate postpartum care of mother and baby.

This 3 hour class is $80.

Breastfeeding

A warm approach to education on the anatomy and physiology of breastfeeding, proper positioning and latch, supply and demand, feeding on demand, early feeding cues, pumping, and common problems.

This 2.5 hour class is $60.

Birth is about making mothers... strong, competent, capable mothers who trust themselves and know their inner strength.

Barbara Katz Rothman

Frequently Asked Questions

The midwifery package includes all prenatal visits, labor & delivery in your home, postpartum and newborn care in your home (3 home visits in the first week), and a six-week postpartum visit in the office for $5000. All education classes are free for clients. Labs and ultrasounds are not included and can be billed directly to your insurance.

We are considered out of network with most insurance companies. You will pay the full fee upfront and have the option to work with a biller to get a reimbursement.

We also accept some Medicaid plans, though not all homebirth expenses are covered by Medicaid.

Angela and Chloe take turns doing office visits and attending births. Having two midwives allows each of us to have family time and a healthy work-life balance. A partnership means there's always a well-rested midwife available for your birth. In the rare event that two women are in labor at the same time, each will have a midwife she already knows and trusts rather than a backup midwife.

We’d like to see you around 10 weeks for your initial visit. Then every 4 weeks until 30 weeks, every 2 weeks until 36 weeks, and then every week until you deliver. One visit, around 36 weeks, will be in your home. All other appointments will be at the office.

Appointments generally last one hour. This time is not spent in a waiting room or sitting alone in an empty exam room waiting for a doctor. We will spend the hour together chatting, getting to know one another, discussing any complaints or questions you may have, reviewing pregnancy and birth education, nutritional counseling, and assessing the health of you and your growing baby.

We will provide all of your prenatal care. SC regulations require that you see a physician for two visits during your pregnancy. There are several providers that we can coordinate these visits with and we will find the best fit for you based on location, insurance, and personal preference. An anatomy scan ultrasound will be performed at one of these visits. You do not need to see a doctor before starting care with us.

Midwives in South Carolina are legally licensed to carry equipment and medications to safely manage normal deliveries at home. This includes: Monitoring equipment for you and your baby; Instruments to clamp and cut the cord; Supplies for the newborn exam and any newborn procedures that you choose; Antihemorrhagic drugs to stop excessive postpartum bleeding; Resuscitation equipment for baby and mother, including oxygen.

Midwives are trained to handle complications and know when hospital transport may be necessary. I have had specific training in emergency skills and hold a NARM Midwifery Bridge Certificate . Through training and equipment, most complications can be handled safely at home. The most common reason for transporting a pregnant woman to the hospital is during a very long labor; either labor is stalled, the mother nears clinical exhaustion, or has decided she desires pain relief medications. In this case, the hospital can provide IV fluids, an epidural, and/or pitocin augmentation, which are tools we do not have in a home setting.

We will help you minimize any mess with instructions on how to set up for your birth. After the birth, we will clean up including washing the laundry and taking out the trash. Your home should feel back to normal with the exception of a new baby.

We have been manipulated to believe that the medical model is the safer option. And then when you start to look at the statistics you can see so clearly that it is not safer.

Dr. Stu and Midwife Blyss of Birthing Instincts #326

Testimonials

Angela, Chloe, and Amanda were amazing from the first phone call to our last office visit. They went above and beyond to care for me while pregnant, and then my daughter and me after delivery. The BEST part was having home visits after delivery.

We absolutely loved our experience having a home birth — and it was because of Angela and Chloe! We always looked forward to the appointments leading up to the birth and left feeling so excited and informed. The birth itself was the most amazing experience! We felt so prepared and safe. Even after we had our baby, whenever we had a question or concern we would text/call her and she always answered no matter the time! We cannot recommend her enough!!

Angela, Chloe, and Amanda provided excellent prenatal, birth, and postnatal care for me and my baby. I am so thankful for the powerful birthing experience they helped me have. I highly recommend them a million times over!!

I had Angela for my second child, first home birth, and it was an amazing experience! Especially after being at an OBGYN that made me feel so alone. Angela is very personable and is truthful and will answer any and all questions. I wouldn’t change anything about my birth experience!

Angela helped us with our second pregnancy and choosing her as our medical care this time around was the best decision hands down. She helped us get through a tough time in our pregnancy that could have landed us in preterm labor at MUSC. With her knowledge of homeopathic remedies we were able to get back to a healthy pregnancy and birth our son at home at 40 weeks and 4 days. Recovery has been amazing and after having our first in the hospital with an epidural and our second at home all natural I can tell you a natural birth at home is the way to go!

My at home water birth experience was amazing thanks to my amazing midwife Angela Springer. Best experience ever, you get to be in control and the atmosphere is so free spirited. For those who are thinking about at home water births please go for it.

I always knew I wanted a home birth, but I am a plus size woman, and was led to believe it wouldn’t be in the cards for me. I sought after it anyways and chose Angela as my provider. The care I received from her and her team was/is night and day to any care I have ever previously received. They carried me through my entire pregnancy, the home birth of my DREAMS and even postpartum continue to be here for me any time of any day. There is nothing like midwifery care, if you’re even considering going this route I highly suggest reaching out and meeting Angela, she is full of knowledge surrounding pregnancy, birth and babies and is eager and passionate about sharing it. We love her!

Angela was absolutely amazing in every aspect when providing care for me during my pregnancy and delivery, which was a totally different experience than I had received at my OBGYN office in which I experienced feeling rushed and not heard or understood, pushed to the side, and the use of scare tactics. Angela was very personal, understanding, and provided me with informed consent on any choices I made during my pregnancy and regarding the birth of my baby. I love building a relationship and even a friendship with the person I knew would be helping me bring my sweet babe earth side. She will always come highly recommended by me. We managed to deliver a 10lb 14oz healthy baby at home in a birth pool safely!!

Angela is amazing. I’m so happy I had her as my midwife! And I’m eternally grateful I was able to give birth at home. She provides excellent personal and professional care, resources, a water tub, an excellent team, education, and a great attitude. She obviously loves her work and takes great pride in serving her local community with her midwifery practice. She helped me deliver a super healthy boy last week, for my first time giving birth, and I felt extremely safe and secure in her care. Even with some minor complications, we were able to avoid a hospital birth, and she handled everything like a pro! We need more midwives, period, and more like her. I can’t recommend Angela enough!

Licensed Midwives providing prenatal, home birth and postpartum care.

Serving Horry, Georgetown, Williamsburg, Florence, Marion, Dillon, Marlboro, and Darlington counties of South Carolina.

Send Message

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Natural Birth at Home

Located in downtown Conway, SC

By appointment only

Copyright © 2022-2024 Natural Birth at Home, LLC - All Rights Reserved.

Photos courtesy of Triple M Photography by Savannah Messer.

Powered by GoDaddy

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 29 August 2018

Early postnatal home visits: a qualitative study of barriers and facilitators to achieving high coverage

- Yared Amare 1 ,

- Pauline Scheelbeek 2 ,

- Joanna Schellenberg 2 ,

- Della Berhanu 2 &

- Zelee Hill 3

BMC Public Health volume 18 , Article number: 1074 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

4817 Accesses

12 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Timely interventions in the postnatal period are important for reducing newborn mortality, and early home visits to provide postnatal care are recommended. There has been limited success in achieving timely visits, and a better understanding of the realities of programmes is needed if improvements are to be made.

We explored barriers and facilitators to timely postnatal visits through 20 qualitative interviews and 16 focus group discussions with families and Health Extension Workers in four Ethiopian sites.

All sites reported some inaccessible areas that did not receive visits, but, Health Extension Workers in the sites with more difficult terrain were reported to make more visits that those in the more accessible areas. This suggests that information and work issues can be more important than moderate physical issues. The sites where visits were common had functioning mechanisms for alerting workers to a birth; these were not related to postnatal visits but to families informing Health Extension Workers of labour so they could call an ambulance. In the other sites, families did not know they should alert workers about a delivery, and other alert mechanisms were not functioning well. Competing activities reducing Health Extension Worker availability for visits, but in some areas workers were more organized in their division of their work and this facilitated visits. The main difference between the areas where visits were reported as common or uncommon was the general activity level of the Health Extension Worker. In the sites where workers were active and connected to the community visits occurred more often.

Conclusions

If timely postnatal home visits are to occur, CHWs need realistic catchment areas that reflect their workload. Inaccessible areas may need their own CHW. Good notification systems are essential, families will notify CHWs if they have a clear reasons to do so, and more work is needed on how to ensure notification systems function. Work ethic was a clear influencer on whether home visits occur, studies to date have focused on understanding the motivation of CHWs as a group, more studies on understanding motivation at an individual level are needed.

Peer Review reports

Approximately 2.9 million neonates die every year, which accounts for 44% of deaths among children under five years of age. 73% of these deaths are in the first week of life, and 36% on the first day [ 1 , 2 ]. This highlights the importance of timely intervention in this vulnerable period [ 2 ]. Several life saving newborn behaviours can be promoted, and interventions delivered, through early postnatal care (PNC). These include an assessment of the baby and treatment or referral, and counselling on breastfeeding, thermal care, hygiene, cord care and on danger signs [ 3 , 4 ].

Evidence shows that home visits by community health workers (CHWs) can be an effective means of delivering postnatal care in high mortality settings, and can reduce mortality [ 5 , 6 ], and this strategy has been adopted by 59 of the 75 countries in the Countdown to 2015 report [ 7 ]. Observational data suggest that these visits need to occur within 2 days of delivery to be effective [ 8 ]. The World Health Organization recommends that those who deliver at home should receive a home visit within 24 h of delivery, and those who deliver in a facility should receive PNC in the facility for the first 24 h and home visits from day three [ 3 ].

There have been mixed results in achieving timely visits. Data from sub-Saharan Africa show modest coverage of postnatal care home visits by CHWs, even in study and pilot program settings. In Malawi only 11% of women received a PNC visit within 3 days of delivery, in Tanzania only 15% within 2 days, in Uganda 26% received a visit on day 1, and in Ghana 38% received a visit on day 1 or 2 (figures calculated from authors data) [ 6 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Data from government programmes show even lower coverage levels [ 7 ]. Given the timing of newborn deaths and the importance of early visits, the need for research in this area has been acknowledged [ 13 ]. We identified only three quantitative studies exploring factors affecting the coverage of postnatal care home visits. A meta-analysis of quantitative data from Bangladesh, Malawi and Nepal found that early visits were more likely if a mother had been visited in pregnancy, if they had notified the CHW about the birth, and if the birth had been at home. In Ethiopia attending ANC, having more than two family meetings in pregnancy with a CHW, delivering with a CHW or skilled attendant, and having the CHW’s phone number were associated with receiving early home visits [ 14 ]. No association with maternal socio-demographic characteristics were found in any of the studies [ 10 , 11 , 14 ]. A program review that conducted qualitative interviews with government policy makers and technical specialists identified the need for a functioning primary health care system, a feasible PNC visit schedule, community demand, a functioning system to notify CHWs of a birth, and a cadre of CHWs who are qualified, motivated, have adequate time, access and transport [ 7 ]. We identified no qualitative studies at community level. Such research could provide evidence on why visits may, or may not, occur based on the experiences of the providers and beneficiaries. This paper reports the findings of a study, conducted in Ethiopia, on factors affecting early postnatal home visits by CHWs - Health Extension Workers. This is particularly timely as a Community Based Newborn Care program is currently being rolled out across the country, which includes early postnatal contacts to identify and manage neonatal sepsis at community level, and to provide counselling to families on newborn care [ 15 ].

Program description

The Health Extension Program was introduced in 2003, and has provided one year of training to over 30,000 female Health Extension Workers (HEW). Two salaried workers, educated to at least grade 10, are selected by local councils to serve an area of around 5000 people. They are stationed in health posts and are supported by a network of community volunteers, called the Health Development Army (HDA). HEWs provide health promotion, and disease prevention and treatment, both in the community and at the Health Post [ 16 , 17 , 18 ]. In 2009 a program to equip HEWs with the skills to provide essential newborn care was introduced, which included early post natal visits [ 19 ], and Community Based Newborn Care (CBNC) was added in 2014 including the identification and treatment of sepsis at community level.

Study setting selection and characteristics