Medicare Reimbursement for Palliative Care

August 23, 2016 by csuwpadmin

Guest Contributor: Kathy Brandt

I just finished a great interview with the head of a Medicaid nursing home diversion program as part of a community-based palliative care needs assessment. I love these calls because I learn so much about the range and scope of services offered in communities.

No matter whom I talk to, each person expresses support for community-based palliative care. And each call also includes a discussion about the reimbursement mechanism for palliative care. Everyone – physicians, caseworkers, administrators, and patient advocates – recognizes the value of palliative care and the challenge in delivering a service that relies on traditional fee-for-service billing.

Loading…

How is Community-Based Palliative Care Reimbursed via Medicare?

The short answer is that it isn’t. The long answer is that there are a few ways that palliative care providers can bill, but Medicare does not currently pay for interdisciplinary palliative care management.

Fee-for-service Medicare reimbursement for palliative care services:

- Physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants can submit bills based on time and intensity of services under fee-for-service Medicare.

- Physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants can also be reimbursed for advance care planning conversations .

- Clinicians can provide ongoing chronic care management — at least 20 minutes of clinical staff time directed by a physician.

- Transitional care management can be billed for up to 30-days to help a Medicare beneficiary transition from an inpatient hospital to their home or similar community setting.

What are the Requirements for Time and Intensity Billing?

Each of the above referenced fee-for-service billing opportunities has specific requirements related to who can bill, what constitutes a billable encounter, documentation, and coding. This blog cannot begin to cover all the information that you’ll need to bill for your palliative care services. Here are a few things to keep in mind:

“Incident to” Billing:

In order to bill for advance practice nurse or physician assistant services under the provider number for the physician:

- The services cannot be delivered in hospital or long-term care settings

- The physician must perform initial visit and initiate the plan of treatment

- The physician must be physically present (in the building) and participating in a direct supervisory role, regardless of the scope of practices of the practitioners – it is a billing rule

As a result of these requirements, incident to billing is perfect for palliative care clinic, adult day care, and similar settings.

Split/Shared Evaluation and Management Services

If a physician and non-physician provider from the same group practice share the evaluation and management, service may be billed under either’s National Provider Identifier if the following criteria are followed:

- Both the physician and nurse practitioner or physician assistant must each personally document and sign their encounter

- The physician cannot simply review the note and make a comment

- The physician can document something from at least one evaluation/management key component, such as medical decision making.

What Are the Key Concepts Related to Fee-for-Service Billing?

- Legibly document what you do and the length of time it takes to do it

- When making billing decisions, start with complexity when considering coding

- Know when and how to use extender codes

To learn more about fee-for-service billing register for the Billing for Palliative Care Services course today.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request Our Newsletter

333 S. Twin Oaks Valley Road San Marcos, CA, 92096 Call: (760) 750-4006

Palliative Care saved this hospital $2M in one year

The CSU Shiley Haynes Institute for Palliative Care has a proven track record. Read this case study to learn how an Institute course helped a strategic team from a South Carolina hospital make the business case for palliative care by showing their palliative care pilot program saved the hospital $2 million in its first year.

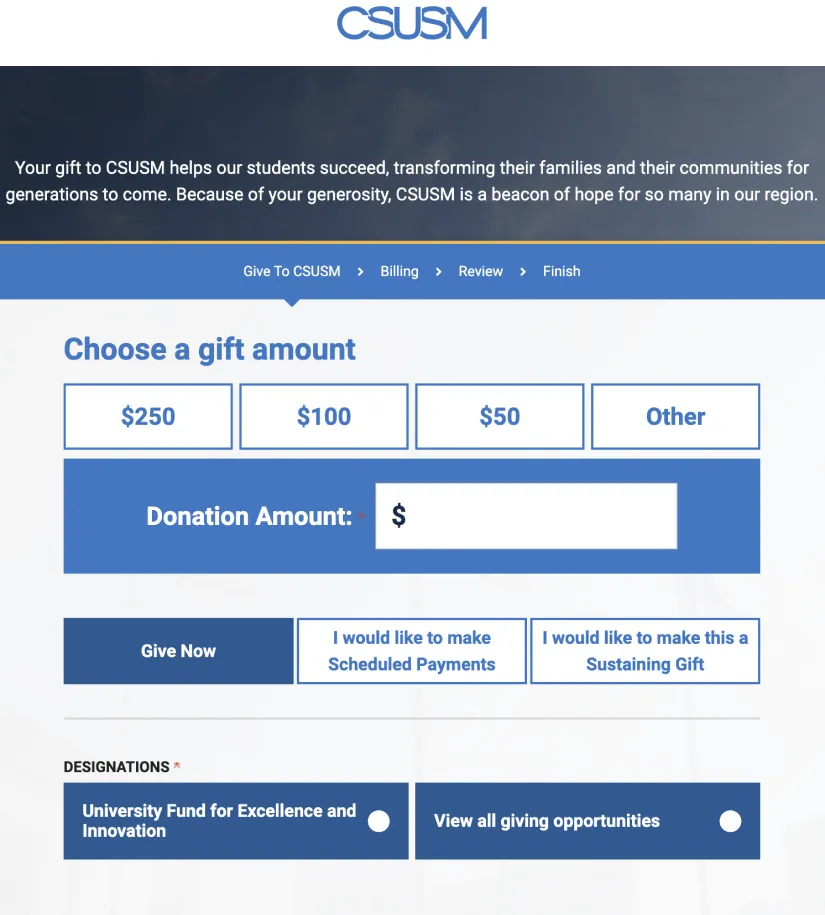

Giving the Gift of Palliative Care Education

The Institute offers scholarships to cover the full cost of tuition in any Institute course, funded by philanthropist Darlene Marcos Shiley to provide training that can enhance care for patients and families in the San Diego region. Join the interest list below.

Alumni: Guiding the Next Generation

If you’ve taken a palliative care course through the Institute, you are part of a movement to transform care for people with serious illnesses and their families. We are invested in your success! Stay connected with us for support, new practice strategies, special offers, and more.

Inspiring Exceptional Whole Person Care

Individuals and organizations committed to improving care and quality of life for people with serious illnesses have supported the CSU Shiley Haynes Institute for Palliative Care since its inception. Their generosity has helped the Institute further its mission and create new palliative care courses that address critical healthcare needs.

Training Your Team with Our Custom Solutions

Partnering with us couldn’t be easier. We collaborate closely with our corporate clients to understand their vision, assess their needs, deliver convenient and effective distance-learning solutions, and help measure results.

Sharing Resources: Request a Free Demo

Our online courses are packed with interactive exercises, evidence-based tools and resources, case studies, and other strategies designed to expertly engage adult learners and reinforce retention. Courses are tailored to help nurses, social workers, physicians, chaplains, and other busy health professionals make a measurable impact on care delivery.

Want to Learn More? Connect with us to get started…

Sharing resources, personally and professionally.

These free resources explore palliative care topics and strategies designed to inspire exceptional whole person care. Stay engaged with us to access new resources as they become available.

Join Our Mission

If you’re passionate about palliative care education and innovation, join our mission to advance and enhance palliative care by educating current and future healthcare professionals, we’d love to connect with you!

Sharing Experiences, Personally and Professionally

The Institute is a respected source of palliative care expertise. If you’re a media professional writing about palliative care, we’re glad to connect you with our staff, faculty, and/or subject matter experts to answer questions or provide a quote.

Contribute to the Discussion, Post or Share a Story Idea

If you’re a palliative care clinician interested in advancing serious illness care by contributing a blog post or suggesting a story idea, we want to hear from you!

Sharing Resources: Request a Faculty Toolkit

The Institute and its Campus Partners began work in 2018 on a pilot program for an online Faculty Toolkit to help college and university faculty integrate palliative care content into classes in multiple disciplines. The online modules include resources and interactive learning activities that focus on the basics of palliative care and health disparities in palliative care.

Disability Accommodations or Special Needs

It is requested that anyone who requires auxiliary aids such as sign language interpreters and alternative format materials notify the event sponsor at least seven business days in advance. Every reasonable effort will be made to provide reasonable accommodations.

Building Palliative Care Awareness at the Local Level

Campus partners build awareness of palliative care through programs for students, faculty, health professionals, and caregivers in their communities.

If you’re a CSU faculty member who is passionate about palliative care, we’d love to talk with you about creating a Campus Partner Institute on your campus. The Institute supports its Campus Partners in several ways, including identifying funders for research, helping with grantwriting, and sharing faculty resources.

Join Our Community of Contributors Passionate About Palliative Care

If you’re passionate about palliative care education and innovation and have specific skills that complement our mission to advance and enhance palliative care by educating current and future healthcare professionals, we’d love to connect with you!

The CSU Shiley Haynes Institute for Palliative Care is continuously seeking to expand our network of content contributors, and freelancers who are skilled in the following areas:

- Subject-matter experts in palliative care or case management

- Online instructors including physicians, clinical social workers, RNs, APRNs, and chaplains with experience in palliative care

- Content and curriculum developers

- Healthcare writers and editors

- Instructional designers

Thank you for your Support!

We are so grateful that you are helping support scholarships for healthcare professionals who need financial assistance to deepen their skills in caring for people with serious illnesses and their families.

Here are some helpful instructions:

Palliative Care Billing and Coding 101

The undefined, in-between stage of a new business forming its vision and roadmap can be challenging in any industry. In the highly regulated healthcare sector, this stage can confuse even the most established provider.

Palliative care currently has no conditions of participation that define its rules and restrictions and is limited in its Medicare-reimbursed services. It should come as no surprise that Medicare billing and coding for palliative care services was one of the greatest challenges to providers in 2020 .

Understanding the few billing and coding regulations in place will help care at home providers succeed in growing their palliative care program.

What Services Are Reimbursed in Palliative Care?

As it stands, there are two types of fee-for-service reimbursement benefits in palliative care: physician services and mental health services.

The physician services Medicare benefit covers physician visits, advance care planning, care management and other visits performed and billed by certain credentialed clinicians. These visits are often called Evaluation and Management (E/M) services.

The mental health services benefit covers clinical social work visits. Social work is not reimbursed under physician services so they cannot bill E/M codes. However, local coverage determinations (LCDs) are in place that define when social work can be reimbursed, typically seen as psychotherapy services.

Who Can Bill Palliative Care Visits?

Clinicians that can provide and bill E/M services are:

- Nurse practitioners

- Clinical nurse specialists

- Physician assistants (or non-physician practitioners)

Clinical social workers can perform and bill for mental health services, but this can be different for each Medicare Administrative Contractor (MAC) .

Chaplain, volunteer and other caregiving visits are typically not reimbursable under Medicare.

What Should Be Included in Palliative Care Documentation?

There are seven elements that must be included in palliative care documentation:

- Physical examination

- Medical decision-making

- Nature of the presenting problem

- Coordination of care

If the visit is medically necessary and performed by a qualified clinician per the benefit category, reimbursement is available. Keep in mind the medical necessity of care provided should be recorded at every visit.

Use these quick tips for acceptable palliative care documentation:

- Every encounter should be medically necessary at the time of the visit, with the medical reason clearly and extensively documented, being sure to include as many specifics as possible. Avoid copying and pasting previous documentation notes.

- All notes must be legible, completed and signed by the qualified clinician who performed the visit. An intuitive electronic medical record (EMR) can help with legibility.

- Document the problem, not the code.

- Reimbursable E/M visits must be justified in the notes through the level of service and the amount and type of documentation.

- Make sure to document the date of the service and the patient’s location; this will allow for more accurate coding.

The positive impact palliative care services has on patients has surpassed the frustration providers have with its billing and coding. Until the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services creates more thorough and inclusive reimbursement opportunities for palliative care, providers should coordinate E/M and mental health services visits for a stable income.

Axxess Hospice , a cloud-based hospice and palliative care software, was built by hospice professionals for hospice clinicians, and includes a palliative care workflow built in for accurate and easy documentation.

- Axxess (132)

- Clinical (142)

- Financial (71)

- Home Care (348)

- Home Health (338)

- Hospice (375)

- Operational (219)

- Palliative Care (127)

- Patient Engagement (68)

- Regulatory (191)

- Revenue Cycle Management (41)

- Staffing (45)

You're in Good Company

See why 9,000+ organizations trust Axxess.

Industry Insights

For healthcare at home.

Get the latest news and business insights affecting home health, hospice and home care providers.

Be the First to Know

Tell us which insights you want to help grow your business and make lives better.

By clicking the button above, you are agreeing to our Privacy Policy.

Thank You For Subscribing To Our Email List

Are You Happy With Your Practice Collections ?

Hit enter to search or esc to close.

Medical Billing for Palliative Care Services

Streamline legacy accounts receivable resolution.

Contact us today!

Helping Physician Groups to Stay Profitable

Don’t let your accounts receivables, stress you.

Contact our Account Receivables Specialist today!

Care delivery models have been evolving for many years and palliative care services is no exception. Palliative care can be provided in hospitals, nursing homes, outpatient palliative care clinics and certain other specialized clinics, or at home. Most often clinicians run into operational problems when billing for palliative care. These services are often closely aligned with hospice care if not documented properly creates the perfect opportunity for claim denial. Unlike critical care or observation care, palliative care doesn’t come with its own set of specific CPT or HCPCS codes, making it really difficult to get reimbursement.

Palliative Care vs Hospice

Most often hospice care and palliative care are considered synonymous terms. Unlike hospice, palliative care services do not focus on terminal illness and dying. Instead, palliative care focuses on meeting the physical, emotional, and spiritual needs of individuals and families facing serious, chronic, or life-threatening illness.

- Hospice care is defined as a comprehensive set of services identified and coordinated by an interdisciplinary group to provide for the physical, psychosocial, spiritual, and emotional needs of a terminally ill patient and/or family members, as delineated in a specific patient plan of care.

- Palliative care is defined as the patient- and family-centered care that optimizes quality of life by anticipating, preventing, and treating suffering. Palliative care throughout the continuum of illness involves addressing physical, intellectual, emotional, social, and spiritual needs and facilitates patient autonomy, access to information, and choice.

Generally, hospice care of terminally ill individuals involves palliative care (relief of pain and uncomfortable symptoms) and emphasizes maintaining the patient at home with family and friends as long as possible. Hospice services can be provided in a home, skilled nursing facility, or hospital setting. In contrast, palliative-care services can be provided during hospice care, or coincide with the care that is focused on a cure.

Billing Guidelines for Palliative Care

- Electing hospice: You have to verify whether the patient has elected for hospice before you refer a patient to palliative care or provide such services yourself. This directly affects services you can bill for and where you need to submit claims. If a patient has elected hospice and you are managing a condition unrelated to that patient’s terminal illness, Medicare requires to append a modifier to the service being reported.

- Clinician Credentialing: Before offering palliative care, you need to verify if you are appropriately credentialed in hospice and palliative medicine. Medicare has assigned a specialty code (17) for palliative care which is required while billing along with your NPI, and taxonomy code (for MD, DO or NPP).

- Place of Service: Make sure you report correct place of service codes that apply to the setting in which you’re providing palliative care. These services can be delivered in many different locations like acute care hospital, skilled nursing facility, nursing home or assisted living, outpatient office, or a patient’s home. Each location has its own set of CPT codes for reporting E/M services.

- Medical Necessity: If you are a palliative care consultant, make sure the attending physician or specialist makes a formal written request for you to evaluate the patient. This written request is not strictly necessary, but it will help support the medical necessity of your services.

- Diagnosis: Submit the diagnosis you are managing as the ‘primary’ diagnosis on the claim. Avoid duplicating clinical efforts or producing conflicting treatment plans. Each specialty involved in the care of a patient must make it very clear which condition(s) each is responsible for managing.

- Group Practice: Keep in mind that as per Medicare, physicians who are part of the same group and same specialty as one physician. If you provide palliative care services on the same day that as your colleague in the group makes a subsequent visit, billing both visits would result in one claim being denied. You could base the level of service your group decides to bill for that calendar day on the combined documentation from both visits.

- Documentation: You need to make sure your documentation in the medical record clearly supports the medical necessity for palliative care services. Because these services may be subject to payers’ pre- or post-payment reviews, the medical record needs to demonstrate not only the specific conditions you are managing for the patient, but why. Documentation is the keys to making sure you will be reimbursed for this important and valuable care.

Palliative care services can be quite costly, as they involve several team members and a substantial amount of time delivering these services. Capturing services appropriately and obtaining reimbursement to help continue program initiatives are significant issues. For getting accurate reimbursement for palliative care, you can connect with expert medical billing company like Medical Billers and Coders (MBC) . To know more about medical billing for palliative care you can contact us at 888-357-3226 / [email protected]

Looking for a Medical Billing Quote?

Are you looking for more than one billing quotes?

Are you looking for more than one billing quotes ?

Would You like to Increase Your Collections?

Request a Call Back

Updated: OHIP Billing Code Refresher – Palliative Care

- January 20, 2021

Providing important palliative care is good for your patients and can lead to a $5,000 bonus .

Palliative care is a service that provides specialized medical care to patients that are experiencing a serious illness. The primary physician in charge of the palliative care patient is required to develop a comprehensive care plan for the last year of life expectancy for the patient. With the focus on caring for the patient, it is often difficult for doctors to also spend time trying to understand and manage their billings. In response to these challenges, we have put together a summary of the palliative care codes in order to make the billing process easier and to help physicians save time in figuring out how to bill the codes to maximize their revenue.

The codes that we see at DoctorCare being billed often by primary care physicians include:

- K023 – Palliative Care Support (>20min) This time-based K code is recommended for services provided in the office or at home. If at home, there are rules and additional codes you need to bill (based on time and day). Please remember to document start and stop times.

- G511 – Telephone Management of Palliative Care This is the telephone support code you can bill if you provide support over the phone to the patient or family.

- G512 – Palliative Care Case Management Fee This is the case management code you can bill when you provide supervision of palliative care to the patient for a period of one week, starting at midnight on Sunday.

- B966 – Palliative Home Visit – Travel Premium This code is billed for travelling to a patient’s home for a visit. This code can be billed as many times as needed.

- B997/B998 – Palliative Home Visit – First Person Seen This code is only applied for the first person seen on that day during the home visit. This code can be billed as many times as needed.

Home Visits

Note, for home visits, you likely will be billing three codes for that one home visit (K023/A900 + B966 + B997/B998). As a best practice, we recommend billing the K023 when you spend more than 20 minutes providing care to a patient. The A900 (complex house call assessment) may be billed on patients that are frail and elderly or housebound when the visit is under 20 minutes.

Additional Related Codes

Other codes that you may bill for providing services relevant to palliative care include the following home care codes:

- K070 for home care application

- K071 for acute home care supervision (first 8 weeks)

- K072 for chronic home care supervision (after 8th week)

- K015 for counselling of relatives

Special Premium Bonus

There is also a special premium bonus for providing these services. In the fiscal year, if you bill K023, C882, A945, C945, W882, W872, B997 and B998 on any patient (rostered or non rostered), it will count for the palliative care special premium bonus.

- Ontario Medical Association (OMA) has excellent resources that contains even more codes for case conferences, special consultations, etc.

- Download our Quick Reference Guide for a quick one-page reference on palliative care codes.

- Request a complimentary FHO special premiums use analysis from us and see how you can maximize your billings.

Need assistance in billing your codes? We’re happy to help.

Related Content

DoctorCare Welcomes Trillium Medical Billing, Expanding Medical Billing Services and Solutions to Ontario Specialists

2023 DoctorCare Year in Review

Understanding and Correcting EH2 and VH9 OHIP Billing Errors

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Sign up for periodic emails on company news, blogs, events, product news, and marketing offers. We respect your inbox and you can unsubscribe at any time.

© 2022 DoctorCare. All rights reserved. |

Site Terms of Use and Privacy

Select Your Interests

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

How Can Palliative Care Help Me?

- 1 Department of Oncology, The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland

- 2 Division of Hematology, Oncology and Transplantation, Department of Medicine, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis

- 3 Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

- 4 Penn Center for Cancer Care Innovation, Abramson Cancer Center, Penn Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

What Is Palliative Care?

Palliative care is specialized medical care for people living with a serious illness. It focuses on providing relief from the symptoms and stress of the illness. The goal of palliative care is to improve quality of life for a patient and their family. Palliative care is provided by a specially trained team of doctors, nurses, and other specialists who work together with a patient’s other doctors to provide extra support. Palliative care is based on the needs of the patient, not on how long someone is expected to live. It is appropriate at any age and any stage of serious illness, and it can be provided alongside treatment for illness. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care. Hospice care is also focused on helping patients and their families feel better, but is specifically for patients who are in the last months of life.

Who Benefits From Palliative Care?

Palliative care can benefit people with any serious illness that affects quality of life. Some examples include people with cancer experiencing pain, nausea, or weight loss; people with lung disease or heart disease who feel short of breath; people with worsening neurologic diseases such as Alzheimer disease or Parkinson disease; or people experiencing difficulty with physical or cognitive functioning from any disease. Palliative care can also assist families and caregivers of people living with serious illness. Studies have shown that palliative care can substantially improve quality of life, symptoms, and satisfaction with care.

What Are the Benefits of Palliative Care?

Palliative care can improve your quality of life while getting treatment for a serious illness. Palliative care teams offer expert management of physical and emotional symptoms, including pain, depression, anxiety, fatigue, shortness of breath, constipation, loss of appetite, and difficulty sleeping.

Palliative care teams focus on what matters most to you in life. Palliative care teams help you clarify your goals, such as relief of pain or maintaining independence. They ensure that these values are communicated to your medical professionals so any treatments are in line with your goals.

Palliative care teams can help you make informed decisions. Treating serious illness often involves making difficult choices that affect your life and well-being in different ways. Palliative care physicians understand the risks and benefits of a treatment or exploring what would be most important toward the end of life.

Palliative care focuses on the whole person. Palliative care addresses a person’s physical needs and also places importance on the psychological, emotional, spiritual, cultural, and existential aspects of care.

When Is the Right Time to Consider Palliative Care?

Palliative care can be helpful at any stage of a serious illness. Patients are likely to benefit most when they connect with palliative care teams early in the course of a serious illness.

How Can I Access Palliative Care?

If you believe that you or a loved one would benefit from seeing a palliative care specialist, speak to your health care professional. They can likely refer you to a palliative care specialist in your area.

For More Information

Center to Advance Palliative Care https://www.capc.org/messaging-palliative-care/

Get Palliative Care Provider Directory https://getpalliativecare.org/provider-directory/

Published Online: September 11, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.4383

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Sources: Hui D, Hannon BL, Zimmermann C, Bruera E. Improving patient and caregiver outcomes in oncology: team-based, timely, and targeted palliative care. CA Cancer J Clin . 2018;68(5):356-376. doi:10.3322/caac.21490

Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA . 2016;316(20):2104-2114. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.16840

Warrier G , Gupta A , Sedhom R. How Can Palliative Care Help Me? JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(11):1284. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.4383

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Best of JAMA Network 2022

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Instructions for Authors

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 14, Issue e1

- Multidisciplinary team meetings in palliative care: an ethnographic study

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1009-2928 Erica Borgstrom 1 ,

- Simon Cohn 2 ,

- Annelieke Driessen 2 ,

- Jonathan Martin 3 , 4 and

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1645-642X Sarah Yardley 3 , 5

- 1 School of Health, Wellbeing and Social Care , The Open University , Milton Keynes , Buckinghamshire , UK

- 2 Department of Health Services Research and Policy , London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine , London , London , UK

- 3 Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust , London , UK

- 4 University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust , London , London , UK

- 5 Marie Curie Palliative Care Research Department , University College London , London , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Erica Borgstrom, School of Health, Wellbeing and Social Care, The Open University, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, Buckinghamshire, UK; erica.borgstrom{at}open.ac.uk

Objectives Multidisciplinary team meetings are a regular feature in the provision of palliative care, involving a range of professionals. Yet, their purpose and best format are not necessarily well understood or documented. This article describes how hospital and community-based palliative care multidisciplinary team meetings operate to elucidate some of their main values and offer an opportunity to share examples of good practice.

Methods Ethnographic observations of over 70 multidisciplinary team meetings between May 2018 and January 2020 in hospital and community palliative care settings in intercity London. These observations were part of a larger study examining palliative care processes. Fieldnotes were thematically analysed.

Results This article analyses how the meetings operated in terms of their setup, participants and general order of business. Meetings provided a space where patients, families and professionals could be cared for through regular discussions of service provision.

Conclusions Meetings served a variety of functions. Alongside discussing the more technical, clinical and practical aspects that are formally recognised aspects of the meetings, an additional core value was enabling affectual aspects of dealing with people who are dying to be acknowledged and processed collectively. Insight into how the meetings are structured and operate offer input for future practice.

- hospital care

- end of life care

- education and training

- communication

- clinical decisions

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-003267

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Key messages

What was already known.

Multidisciplinary team meetings are a recognised component of palliative care as well as in a range of other care settings (eg, cancer).

The meetings provide an opportunity to coordinate multiple clinical and social services that might be relevant for complex patient needs.

Multidisciplinary team meetings enable palliative care teams to report patient deaths and offer an opportunity to discuss matters that are currently unclear or unresolved.

What are the new findings?

While the many practical, clinical and social support elements that inform decision-making are formally recorded, the meetings also enable staff members to share and negotiate the negative affective dimensions of their work.

While these aspects are not formally documented, their acknowledgement helps support individual staff members and consolidate the team.

What is their significance?

Clinical: it may be tempting to undervalue the role of regular meetings, especially when no major new decisions are made, and when there are increasing resource pressures put on the team. However, recognising some of the less tangible aspects is crucial—not only for the ongoing welfare of staff but also indirectly as a means to protect and conserve the emotional dimensions of caring for people who are ill and/or dying.

Research: more thorough and detailed qualitative research into this topic is likely to reveal further related aspects of these meetings, including the dynamic nature of individual and collective decision-making and processes of sharing emotional burdens.

Introduction

Multidisciplinary team meetings (MDTMs) are a key component of palliative care practice in the UK. Yet, while MDTMs have been the gold standard in cancer care for over 30 years, 1 there is a lack of existing literature internationally that describes the structure and function of palliative care MDTMs. 2 MDTMs exist to ensure collaboration across professions (medical, nursing, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, social work and spiritual care) , 3 although the composition often varies. Meetings can include patient case discussions, decision-making, education and research. 4 Over the years, MDTMs within palliative care have evolved, as teams draw on them for different purposes while increasingly working under system constraints. Against this background, we describe and analyse the MDTMs of a hospital and a community-based palliative care team to provide insight into how the meetings are structured and operate, to offer input for future practice, and as the basis for future research into the topic.

Data were drawn from a larger ethnographic study of palliative and end-of-life care in the UK. 5 6 The study focused on two affiliated multidisciplinary palliative care teams in London, covering community and hospital care. Data for this paper were collected between May 2018 and January 2020 and comprise observations of over 70 MDTMs. Observations were primarily collected by AD, augmented by some made by EB and SC, all of whom are anthropologists trained in studying medical and health issues. Not being healthcare workers or specialists in palliative care ensured observations were made from an ‘outsider’s perspective’, which provides a critical detachment to the topic. 7 Each meeting was observed in full, with the presence of the researcher formally recorded and made known to everyone attending. Field notes were written both during and after each meeting in line with the restrictions imposed by the HRA ethics approval. All names, specific places and any identifying details of individual staff members and patients were redacted.

Field notes were typed up, imported into NVivo V.12 and analysed by the research team in two parallel operations. First, the pattern and format of each meeting were identified and compared with each other in order to generate a general summary of the structure of the MDT meetings. And second, specific aspects of the qualitative data were coded inductively and gradually grouped in order to create higher level categories. 8 These preliminary topics and themes were then shared with the palliative care teams both on an ad hoc basis and during a number of scheduled workshops in order to solicit feedback and help refine them. It is these main, higher-level themes that are reported here.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from all relevant parties: HRA (IRAS project ID: 239197), Research and Development of University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and the ethics committee at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Description of a typical meeting

At the time of the study, each team (community and hospital) had approximately 20 staff; hospital MDTMs were often complemented by people from collaborating services (specifically chaplaincy, bereavement services and/or pain team). The teams meet independently on the same day and time each week, on a day aligned with their joint teaching sessions. Meeting spaces varied depending on the availability of office space. At times, the rooms were too small for the teams, especially if the projector was used for electronic note sharing and taking.

General format followed in both settings

MDTMs were usually attended by all healthcare staff members, except the person covering triage and those part-time staff who prioritised time to directly see patients. The chair and note-taking functions rotated to promote equality and skill development; one person was charged with looking up any missing information (such as date of referral, diagnosis) via a laptop. In addition, they would confirm whether there was any documentation of a patient’s wishes via an electronic system. Use of other computers and phones was avoided to reduce distractions, although urgent calls were always accepted.

The meetings were nominally scheduled to last 90 min. The format followed a standard structure; introductions for any guests, brief discussion of recent deaths across the part of London they covered (allowing the bereavement officer to then leave), more in-depth discussion of individual complex cases, review of new referrals, an update on staff activities that day including joint visits and 1–1 meetings.

Discussion of complex cases was the core of MDTMs. Colleagues were encouraged to nominate cases prior to the meeting to facilitate record retrieval; however, urgent cases were added during the meeting. Each case presentation was led by one professional (often the keyworker), who would narratively describe the patient and their situation (known as the scenario), with those also familiar with the case contributing spontaneously. Discussion included overview of potential issues and areas staff felt required further support. Attendees would ask questions and offer suggestions, with the intention of reaching a consensus on next steps—such as coordinating a joint visit between different services. The amount of time complex case discussions took varied; occasionally the teams used discussion frameworks or timers to encourage concise descriptions, particularly when there were many cases to cover.

A summary of the case description and a list of action points were formally recorded. The use of a number of locally devised codes for record keeping—‘nature of complexity’, ‘safeguarding or other risks’, ‘rapidly changing condition’, ‘equipment’ and ‘social support’—enabled more time for collective discussion and reflection. In addition, Outcome Assessment and Complexity Collaborative measures were agreed and recorded to describe the stage of illness. 9

Key observations

The physical environment affected how meetings unfolded; being cramped into a space and not able to see everyone hampered discussion. A sense of collegiality was established by informal introductions, humour at the start or end of the meeting and simple actions such as sharing fruit and biscuits. While not all case discussions were immediately relevant to all staff present, contributions from anyone were always valued. Different disciplinary perspectives helped question assumptions and provide complementary expertise. New members of the team rapidly learnt how to present, and relate to, complex cases by attending and participating in MDTMs.

While all team members saw MDTMs as a central part of their work, it tended to be framed as a management and administrative task rather than a direct form of patient care. At times, staff expressed concerns that attending meetings reduced time available for interacting with patients and their families, an aspect of their work that they highly valued and was often pressurised due to workload volumes. But in addition to supporting clinical and practical concerns, such as treatment decisions, agreeing joint-visits or tracking patients as they moved been acute and community settings, we observed that MDTMs served several other functions. Staff were able to express their own emotional response to cases that were often complicated and frustrating to deal with. Although these affectual dimensions could not always be resolved, sharing them with the team shifted responsibility and burden from individual professionals to being acknowledged and taken on by the team. Our findings indicate that there can be a difference between what staff perceive the use of meeting to be, which may be more administrative, and the value of the meetings when considering how they influence patient care, staff well-being and collaborative working.

Standardised codes and team discussions established a shared understanding of what a complex case was. Often this related to instances when it is not clear what should happen next or who should take the lead for subsequent actions. Even when no new clinical decision arose, the opportunity to explore different possible ways to proceed had real value, cultivating individual and collective capacity to respond. Since many complex cases were discussed repeatedly at various MDTMs, a longitudinal perspective emerged that helped inform suggestions for how to proceed.

Research into MDTMs, and our own observations, indicates that they have several implicit and explicit functions. They are beneficial for teamwork and patient care 10 ; they provide attendees with the opportunity to gain awareness and appreciation of views central to different professions. 11 Professionals find them useful, providing a comprehensive approach to care viewed as integral to palliative care, 12 even though there is complexity in the communication during meeting 12 and meetings can be time-consuming. 13

Although the effectiveness of MDTMs is regularly considered, 14 rather than solely being opportunities to plan or make decisions about patient care, MDTMs provide support for individual professionals and are highly valuable for the solidarity and continuity of the team itself. While discussion of difficult cases is not intended to have therapeutic value for staff (they have other support systems for this), it nevertheless often helps individuals feel supported, release emotional burden and shift a case from being experienced as a personal burden to one the whole team takes responsibility for. Additionally, the regularity of meetings allows for the sharing and accumulation of expertise among members as well as informal training for rotating and new staff.

The MDTMs we observed differ from other MDTMS, such as those that follow cancer peer-review criteria to discuss all new referrals or other integrated community palliative care teams that are linked with hospices. Through the Forms of Care project, senior team members reflected on these elements, suggesting further work may be needed in terms of setting ground rules and articulating the major values of meetings.

There are several recommendations from our observations:

The space where a meeting is held often matters more than may be realised; this was noticed by the teams especially after doing online meetings (after data collection finished). Not only can it impact contributions and collegiality but also can impact the value accorded to the meetings.

An agreed format and prescribed timings help convey expectations while also ensuring that the meeting does not overrun; however, some flexibility is essential in order to respond to specific issues and concerns that can be raised during the course of discussion.

Documenting action plans during the meeting, rather than after, improves record keeping and ensures that staff are clear about what has been decided. Varying who fills in the documentation can share workload and build confidence with using clinical and/or administrative codes.

Ongoing discussion about the format, outcome and experience of meetings can help align meeting activities with team objectives and strengthen interprofessional relationships.

The total value of MDTMs can only be appreciated by recognising the wide range of additional aspects, beyond merely the clinical and social support decisions that are officially recorded.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not applicable.

- Hoinville L ,

- Pottle E , et al

- Anderson M , et al

- Glynne-Jones R , et al

- Lamprell K ,

- Arnolda G ,

- Delaney GP , et al

- Borgstrom E ,

- Driessen A ,

- Murtagh FEM ,

- de Wolf-Linder S

- Davidson T , et al

- Ashby M , et al

- Powazki RD ,

- Shrotriya S

- Alexandersson N ,

- Hagberg O , et al

X @ericaborgstrom

Contributors All of the authors meet the criteria set out by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals.

Funding This study was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ES/P002781/1).

Competing interests In terms of competing interests, the research team (EB, SC and AD) received funding from the UKRI-ESRC (ES/P002781/1). SY and JM are both employed by the clinical sites and provide leadership within the sites, which were involved in the study; they were not financially remunerated as part of the research project.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

What Hospice VBID’s Ending Means for Palliative Care

- --> --> -->