- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

'The Summit Is Never The Goal': Why Climbers Pursue The 7 Summits

Abigail Clukey

Alison Levine, a member of the Seven Summits Club, led an all-female expedition up Everest in 2002. Jake Norton/Courtesy of Alison Levine hide caption

Alison Levine, a member of the Seven Summits Club, led an all-female expedition up Everest in 2002.

At least 11 climbers died on Mount Everest last month, including two Americans in pursuit of joining the Seven Summits Club, a select group of roughly 500 people worldwide who have climbed the tallest peaks on every continent. Everest was the final summit for both Christopher Kulish and Donald Cash. Each died on his descent.

The deaths have sparked concern over Nepal's distribution of permits , dangerous conditions and overcrowding on the mountain.

But members of the Seven Summits Club who have experienced Everest firsthand say that this level of crowding isn't out of the ordinary.

"When you're going up to the summit and you look around and there's 250 other people, that's not a surprise," said Cason Crane, a 26-year-old mountaineer who summited Everest in 2013. "And especially if you actually read the reports from the mountain, people were fully aware it was crowded, and they made the choice to still climb."

As climbers like Crane have heard about the recent Everest casualties, they have reflected on their own experiences at the world's highest point, and why, despite the risks and intensive labor involved, they felt compelled to climb not just one major summit, but seven.

Cason Crane completed the seven summits in 2013 to raise awareness and funding for suicide prevention among LGBT youth. Courtesy of Cason Crane hide caption

The particular feat of climbing the seven summits took off after American businessman Richard Bass reportedly became the first mountaineer to do so in 1985. He popularized a version of the challenge that included Denali in North America, Aconcagua in South America, Kilimanjaro in Africa, Elbrus in Europe, Vinson Massif in Antarctica, Kosciuszko in Australia, and of course, Everest in Asia. Since then, the exact summit list has been a topic of debate. Today, a version called the Messner list, after Italian mountaineer Reinhold Messner, is considered the most legitimate in the climbing community. It takes into account Australia's surrounding islands when determining its highest point, swapping the 7,310 ft Kosciuszko from Bass's list for 16,024 ft Carstensz Pyramid in the Papua Province of Indonesia.

David Mauro didn't set out to climb all seven summits — a trait that is surprisingly common among mountaineers who have. He began climbing when his brother-in-law invited him on a trek up Denali in 2007 — a daunting expedition even for seasoned climbers. Having just gone through a divorce in his 40s and feeling like his life resembled a "big dumpster fire," Mauro thought there wasn't anything holding him back.

"If I hadn't been at such a low point in my life, I probably never would have become a mountaineer," Mauro said. "At some point it just occurred to me that I had nothing left to lose."

When Mauro got back from Denali, he got a tattoo of its profile to remember his adventure and decided to quit climbing. But three months later, he said he felt a calling to climb another mountain, and made plans to summit Kilimanjaro. In the seven years that it took him to climb the rest of the seven summits, Mauro said he backed away from the sport several times, but the emotional rejuvenation he experienced each climb always made him return.

"What happened was each time I did one of these mountain climbs, there would be this rich lesson that would come out of it that was immediately relevant," Mauro said. "It became this seven-year conversation between the mountains and my personal life."

David Mauro rappelling off Everest's south summit during his 2013 expedition. Courtesy of David Mauro hide caption

David Mauro rappelling off Everest's south summit during his 2013 expedition.

Stories of how mountaineering can foster intense personal growth, however, don't diminish the elements of extreme danger prevalent in the most common Everest narratives. Each spring brings climbing-related deaths as hundreds of people attempt to scale the nearly 30,000-foot peak.

Alison Levine, who has climbed all seven summits and led an all-female Everest expedition in 2002, said part of what makes climbing Everest so dangerous is that mountaineers can become consumed with blind desire to get to the top and will ignore crucial signs of exhaustion or hazardous conditions. In her 2002 trip up Everest, Levine and her team had to make an early descent only 275 feet from the top because of a turn in weather, a decision that prioritized safety over summiting.

"What you have to remember in the decision making process is that the summit is only the halfway point," Levine said. "The summit is never the goal. Ever. The number one goal is always to come back alive."

Crane says it's necessary to constantly analyze risks is when climbing peaks as severe as the seven summits, and that most people grapple with the possibility of death before they start an expedition. Each serious climb is made up of conscious choices that he believes aren't always acknowledged in stories about mountaineering, and Everest in particular.

"I do think that sometimes gets lost in the mix, when people just talk about the weather, they just talk about the crowding, but there are actually a lot more decisions in between those points and in addition to those factors that do contribute to the outcome," Crane said.

Amid Deadly Season On Everest, Nepal Has No Plans To Issue Fewer Permits

Though the perceived point of the Seven Summits Club is to reach the globe's highest peaks, those who have completed this challenge often don't cite summiting as the most formative experience. What stands out, according to Crane, Levine and Mauro, isn't the glory that comes with looking down from the top of the world. It was everything that led up to it.

When Levine returned to Everest eight years after her first attempt, she finally reached the summit — her last on the challenge's list. But, she says, she found the act of summiting itself somewhat underwhelming.

"When I did make it to the summit, what I realized is that standing on top of a mountain doesn't change you and doesn't change the world," Levine said. "It's really about the journey, the journey is the most important thing on any mountain."

As this deadly month on Everest has shown, extreme mountaineering, especially in the form of a Seven Summits bid, poses significant risk. It's the powerful inner voice, though, that sets climbers on paths up the precarious slopes anyway and takes them beyond cementing themselves in this elite club.

"Bragging rights ain't gonna get you to the top of any of those hills," Mauro said. "There's gotta be something much, much deeper inside of you that drives that quest."

Abigail Clukey is an intern on NPR's National Desk.

Premium Content

How an all-Nepali team pulled off one of the most dangerous climbs in history

Driven by national pride, 10 elite mountaineers united to make it the top of K2 in the dead of winter

Swallowed by the empty black night, Mingma Gyalje Sherpa tried to focus the shaky orb of his headlamp on his next few steps, but the cold overwhelmed his thoughts. Clad in a bulky down suit, with another down jacket underneath, plus two layers of long underwear and breathing bottled oxygen, he should have been OK. But in all the peaks he’d summited, all the blizzards and frigid gales he’d weathered, he’d never felt temperatures quite like this—a piercing, otherworldly cold.

He could sense his body shutting down. His left side bore the brunt of a stout wind, with each gust sending icy tendrils slicing through everything he wore. But his right foot was especially worrisome. It had tingled, then burned, and finally ebbed into numbness, a precursor to serious frostbite. That, he knew, was a sign his body was prioritizing blood flow to warm vital organs, sacrificing the extremities to preserve the core. And this was all happening before he’d even crossed into the so-called Death Zone—the region above 8,000 meters (26,247 feet)—where the lack of oxygen can cause climbers to hallucinate, retain fluid in their lungs, and lose their instinct for self-preservation.

Mingma G.—as he’s known—keyed his radio, his mind momentarily made up to turn around. “Dawa Tenjin? Dawa Tenjin?” he called, but only the whining wind answered. He could make out the dim lights of several teammates trudging in a broken line up the low-angle snow above him. Everyone must be too focused on the tasks at hand, or just too deep in their own suffering, to answer, he thought.

Even in the milder summer months, K2, the second highest peak on Earth at 28,251 feet, is among the world’s deadliest mountains. Though it’s more than two football fields shorter than Mount Everest, getting to its summit requires a much higher degree of climbing skill and almost no margin for mistakes. American climber George Bell, after failing to summit in 1953, declared, “It’s a savage mountain that tries to kill you.” The nickname has stuck, in part because for roughly every four climbers who make it to the top and back down, another one dies in the attempt.

But now, almost four weeks after the winter solstice, when the Northern Hemisphere tilts farthest away from the life-giving warmth of the sun, the conditions on the mountain are some of the harshest on the planet. The windchill temperature on its upper reaches can drop to minus 80 degrees Fahrenheit—roughly the same as the average temperature on Mars.

And yet, this was a moment Mingma G. had been dreaming about. Even as he laboriously kicked his numb right foot into a patch of ice in a desperate attempt to stave off frostbite, he knew some of his teammates were fixing sections of rope to the mountain using an array of ice screws, pitons, and snow pickets, building a secure trail to follow toward the summit.

For most experienced mountaineers, the thought of climbing K2 in winter was lunacy. Six serious expeditions had attempted the feat, but none had come close to the top. There seemed to be too many challenges to overcome: unpredictable hurricane-force gusts that could blow a string of roped climbers off in an instant; falling rock and ice that roared down like artillery; lung-starving, mind-muddling thin air; and the deep, unforgiving cold. Even the most resolute and experienced teams had withered under the brutal conditions, the pressures and dangers often causing them to implode with personal conflicts and leadership issues.

(Follow the all-Nepali team's winter route to the top of K2)

In the final months of 2020, some 60 climbers arrived at the foot of K2 on the remote Godwin Austen Glacier in Pakistan’s part of the Karakoram Range, all seeking the last remaining prize in high-altitude mountaineering—and arguably the toughest of them all. But for Mingma G. and his nine teammates, all Nepalis, the expedition offered more than just personal glory. It was a chance for them to prove that Nepal—a nation defined by some of the world’s biggest mountains—could achieve what many thought was impossible.

Now, as Mingma G. surveyed his situation, the path to K2’s elusive summit seemed tantalizingly within reach. But at what cost? He knew firsthand how a severe injury could forever alter his life. His father, also a mountain guide, had lost all but two of his fingers to frostbite when he’d removed his gloves to tie a foreign client’s bootlaces on Everest. What if one of his teammates lost a limb or was killed? Would the summit be worth it? For Mingma G. and the members of the expedition, even with a clear understanding of the risks and the deadly cold seeping into their bones, the answer was unanimous.

By 2020 the notion of groundbreaking mountaineering achievement seemed like an anachronism. Midway through the past century, all of the world’s highest summits—the 14 mountains that top 8,000 meters—had been climbed. First came Nepal’s Annapurna I in 1950, then Everest and Pakistan’s Nanga Parbat in 1953; the rest fell in succession until Tibet’s Xixabangma was claimed in 1964.

It was a fevered run of nationalistic efforts, and though all the mountains were in Asia, European teams claimed the majority of these prizes. And while virtually every expedition of this era relied on local ethnic groups, including the Sherpas, Tibetans, and Baltis who transported gear to the Base Camps and carried loads up the mountain, the true contributions of these indispensable partners rarely were acknowledged in the history books.

(In this episode of our podcast Overheard , Mingma Gyalje Sherpa tells the story of the epic journey on what experienced climbers call the Savage Mountain. Listen now on Apple Podcasts. )

With these landmark first ascents accomplished, Polish mountaineer Andrzej Zawada came up with a new challenge. All the eight-thousanders had been climbed in summer, during the most favorable conditions. More difficult, he reasoned, would be to climb them in winter, their harshest season. Zawada led an expedition that put two climbers on the summit of Everest in the winter of 1980 and set Poland on a historic string of winter firsts. One by one, the eight-thousanders fell, but Pakistan’s peaks stubbornly resisted winter mountaineers well into the 21st century. Located eight degrees of latitude north of the Nepali peaks, the Karakoram Range is notably colder and windier in winter. It took 31 attempts before Nanga Parbat finally was climbed in 2016, leaving only K2.

(How climbers faced down the ‘death zone’ on one of Earth’s tallest mountains)

Although overshadowed by Everest in the popular media, K2 is considered a far greater challenge by serious mountaineers, partly because of its extreme remoteness. When the British survey team recorded the first elevations in the Karakoram in 1856, they replaced their survey designations with local names. K1, for example, was known by the local name Masherbrum. But since K2 isn’t visible from the closest village, Askole, a week’s trek from the peak’s base, it hadn’t been named.

After four days’ hiking over rough terrain, K2 comes into view from the south, its iconic pyramidal form rising like an arrowhead pointed at the heavens. Climbers quickly note its steepness, especially near the top, which means that any mistake is magnified to near-fatal consequences. Trip over your crampons or clip into an unsecured line by mistake, and it’s unlikely you’ll stop falling before hitting the glacier thousands of feet below.

Because the margin for error is even further reduced in winter, success, or really survival, comes down to logistics—planning for the worst conditions and nightmarish scenarios. Colossal peaks, such as Everest and K2, are rarely climbed in a single linear push. Rather, teams generally move up and down the mountain, acclimatizing to higher altitudes while setting up a network of fixed ropes and camps stocked with critical gear, such as oxygen bottles, tents, and ropes. In recent years, the notion of a faster, lighter style of alpinism has prevailed, but K2 in winter calls for an old-school group effort: Individuals must haul several heavy loads over dangerous terrain. It demands old-fashioned teamwork.

Mingma G. stands five feet nine inches, tall for a Sherpa. He’s 33, broad-shouldered, and often wears his hair in a thick mop extending past his collar that is vaguely reminiscent of a 1970s rocker. He tends to look people in the eye when he speaks and has a way of cutting directly to the point that seems to add weight to his words.

He grew up in Rolwaling, a narrow valley west of Everest. It’s far from the bustling Khumbu Valley, yet Rolwaling has produced some of the most renowned Sherpa mountain guides. Mingma G. grew up listening to his father and uncles, all of whom worked as guides, tell tales of Mount Everest around the kitchen stove on cold winter nights. The stories they told weren’t so much about the foreign mountaineers who flooded Nepal each spring as they were about homegrown heroes such as Pasang Lhamu Sherpa, who in 1993 became the first Nepali woman to summit Everest and died on her way down, and his first cousin Lopsang Jangbu Sherpa, who assisted climbers during the 1996 disaster made famous by the book Into Thin Air and then tragically died four months later.

In 2006, when Mingma G. was 19, his uncle took him on his first expedition to Manaslu. The next year, Mingma G. summited Everest while working for a French outfitter, and by 2011, he was organizing and leading his own expeditions. Those were difficult years. From 2001 to 2008, Nepal was gripped by a violent Maoist insurrection, and many international mountaineers stayed away. Competition to guide the few who dared to come to Nepal was intense.

In the winter season of 2019-2020, Mingma G. cobbled together his own attempt to claim the first winter summit of K2 with three paying clients. Life at Base Camp—which at 16,272 feet sits nearly 1,800 feet higher than Mount Whitney, the highest point in the continental United States—was itself a severe trial. “If we washed our clothes, then it takes more than a week to get it dry unless we dry them on gas heater or stove,” he wrote to mountaineering journalist Alan Arnette.

After arriving at Base Camp, Mingma G. caught an upper respiratory infection and had to withdraw from the expedition. But it wasn’t long before he began thinking about trying again.

And then COVID-19 struck. Tens of thousands of guides, porters, and cooks were out of work across the Himalaya. Within weeks of returning from K2, Mingma G.’s entire year of guided climbs evaporated, leaving him with no income and a small business to support. He tried to talk a few friends into another attempt on K2, but nobody wanted to spend the $10,000 for a permit just to reach Base Camp, plus tens of thousands more to mount a no-frills effort.

Many Nepali mountaineers had been part of groundbreaking climbs, but no all-Nepali team had claimed a historic first ascent on its own.

Mingma G. considered dropping the idea, but something gnawed at him. Tenzing Norgay, a Sherpa, was one of the first two people to stand on top of Everest, and though he was a national hero with his photo proudly displayed in countless Nepali homes, he had shared the achievement with Edmund Hillary of New Zealand. Nepali climbers had been part of other groundbreaking climbs, but none had ever claimed a truly historic first ascent all on his or her own.

“When I went through Wikipedia, there was no Nepalese flag on the winter 8,000-meter list,” Mingma G. says. “I realized if we lose K2, we’re going to lose all the 8,000-meter peaks.”

He knew he’d have to spend the money, even if it meant mortgaging the piece of land he’d bought in Kathmandu, which represented most of his savings. He was able to recruit two brothers, Kilu Pemba and Dawa Tenjin Sherpa, both older than he, with wives, teenage children, and decades of high-altitude experience.

But their families had reservations. “It was very difficult for me to convince the wives of Kilu Pemba and Dawa Tenjin,” recalls Mingma G., who is unmarried. “They said, ‘If our husbands die, then we’re going to come stay in your home and you need to feed us.’ That made me a little crazy … and very worried.”

( Stunning photos capture Earth's highest peaks at their deadliest )

There was another problem. After years of back-to-back expeditions and the demands of running his own business, Mingma G. faced a startling realization for a Sherpa: He was out of shape. As he waited in Kathmandu for the pandemic to subside, a family member began coaxing him out for hikes and bike rides. “I lost many kilos and started feeling strong again,” he says.

Mingma G. wasn’t the only Sherpa with K2 in his sights. A trio of brothers—Mingma, Tashi Lakpa, and Chhang Dawa Sherpa, the principal owners of Seven Summit Treks—realized that Pakistan was one of the few mountaineering destinations still open in the high mountains of Asia.

By charging fees below those of Western outfitters, Seven Summit Treks had established itself as one of the most successful Sherpa-owned expedition companies and routinely fielded one of the largest groups on Everest each season. That March, contemplating its own disastrous year of cancellations, Seven Summit posted inquiries on social media to see if any clients might be interested in a winter K2 expedition. It quickly booked one in full, with climbers from Russia, Spain, Ireland, Turkey, and the United Kingdom.

On December 21, 2020, the first calendar day of winter, Mingma G. and his two teammates started up K2. Several days later, they were camped at 22,600 feet, below a section known as the Black Pyramid—a near-vertical mass of crumbling rock, the first major technical challenge. It would take a full day of precise climbing with heavy packs to reach Camp III, the launchpad for a serious attempt on the summit. But they had a problem: a shortage of rope.

Mingma G. knew that several teams were acclimatizing at the camps below them, including another Nepali team led by a flamboyant former special forces soldier turned climber named Nirmal “Nims” Purja. Mingma G. and Nims had met before, briefly. “We didn’t have any formal introductions,” Mingma G. says. “We just shook hands once, and I said, ‘I’m Mingma G.’ … It was not necessary for him to introduce himself.”

That was in 2019, when Nims was in the midst of a record-setting six-month, six-day blitz to climb all 14 of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks. The media had taken notice, and Nims went from relatively unknown to social media darling.

(Nepal climber makes history speed-climbing world's tallest peaks)

In truth, the two men couldn’t help but feel a bit of rivalry. Both were extremely capable leaders in their physical primes, who were experts in one of the world’s most dangerous pursuits. But they had very different styles: Mingma G. was reserved and no-nonsense; Nims was brash and funny and, true to form, had announced to his social media followers his objective to be the first on K2 in winter.

Nevertheless, Mingma G. figured he’d radio down and ask Nims if he had rope to spare. Even though Nims’s team had just arrived on the mountain and the men weren’t yet acclimatized, they volunteered to carry some up. The two teams chatted over tea the next morning at the camp just below the Black Pyramid and discovered that neither had brought foreign clients. They all wanted K2 for themselves.

The next day, everyone descended all the way down to Base Camp to recover. A gray sky seemed to filter all the color from the glacier, and a persistent wind raked streams of ice crystals among the flapping tents. It was December 31, and with a bad forecast in the offing, it was time to get some rest—if that was possible in such an inhospitable place.

That evening, Nims dropped by Mingma G.’s mess tent to invite the rival team to a New Year’s celebration. At first, Mingma G. wasn’t in the mood to go, but Nims sent two teammates to persuade him to join the festivities.

You May Also Like

Why Scotland should be your next ski destination

What it's like to visit the Swiss mountains in winter

There's a frozen labyrinth atop Mount Rainier. What secrets does it hold?

Stripped of his high-altitude gear, Nims cuts a youthful figure, his smooth cheeks and thin wisps of facial hair belying his 37 years. The former soldier prides himself on being prepared. “That’s one thing you learn in the army, mate,” he says, his speech peppered with the slang of an English pub. “Everything has a backup plan. My backup plans have backup plans, man.” When Mingma G.’s team arrived at the party, Nims promptly uncorked a bottle of whiskey.

“When we finished that one, we started feeling a little dizzy,” Mingma G. recalls. “Then Nims opened another one, and then another one, and then another one.” Soon everyone was dancing and discussing the weather and the plan.

Nims is not an ethnic Sherpa but a Magar—an indigenous ethnic group from the middle hills of Nepal. He grew up in Chitwan, a low-altitude district, more famous for elephants and tigers than snowy mountains. At 18 he enlisted in the Gurkhas, a British military regiment of Nepali soldiers that exists as a vestige of the British Empire. Along with becoming a mountain guide, joining the Gurkhas is one of the best professional opportunities available to ambitious Nepali men: Gurkhas receive pay on par with British soldiers and have the right to gain British citizenship.

After six years in the Gurkhas, Nims joined the Special Boat Service, a unit akin to the U.S. Navy SEALs. “We’ll just say I have been deployed in sensitive areas, that’s it,” he said in a 2019 interview. But he discusses his military experiences, including a firefight in which he was shot in the face, in more detail in his recent book.

“In the special forces, the things you are doing … you feel invincible,” Nims muses. “But then when I went to the mountain, it was very clear that nature has bigger things to say.” In 2019 he resigned from the military to become a professional mountaineer and pursue his dream project: climbing all 14 of the eight-thousanders in seven months. The idea had been bandied about before, but nobody seriously had undertaken the challenge.

Dubbing his effort Project Possible, Nims recruited a crack crew of Nepali guides to help prepare routes and climb with him, much like a Tour de France team deploys riders to pace their leader. After summiting one mountain, he headed straight to the next, sometimes via helicopter, which allowed him to maintain his acclimatization to higher altitudes. And he made ready use of bottled oxygen and in some places relied on ropes fixed by other teams, which purists argued cheapened the achievement.

Now, more than a year later, his K2 team included a core veteran of that group, Mingma David Sherpa, a sprightly 31-year-old guide who serves as Nims’s chief deputy. The old man of the new team was Pem Chhiri Sherpa, a 42-year-old Rolwaling Sherpa with 20 years of Everest experience. Nims also recruited Dawa Temba Sherpa and Mingma Tenzi Sherpa, both highly experienced mountaineers. The last team member was the youngest: Gelje Sherpa, a 28-year-old guide with an infectious sense of humor.

As Gelje told jokes and deejayed the New Year’s Eve party, an idea started to percolate between the two teams: Why not join forces? As Pem recalls, the benefits were obvious: “It sped up the work, and we started working together. It became easier because we all were Nepalese.”

As Gelje told jokes and deejayed the New Year’s Eve party, an idea started to percolate between the Nepali teams: Why not join forces?

Sherpas who work in mountaineering have a reputation for generally being easygoing, displaying a Buddhist sense of detachment toward life’s trials, but the profession takes a heavy toll. In addition to the physical pain—faces burned by frostnip, arthritic joints, and chronic back problems—they’d all lost friends and relatives to mountaineering. The past seven years had been particularly cruel. An avalanche in 2014 killed 16 of the most experienced Sherpas on Everest and brought the climbing season to a halt, and in 2015 an earthquake killed 19 people at Everest Base Camp and about 9,000 across the entire country. Now the pandemic had cost them another year’s work. They also knew the bitterness that comes with a thankless job. “Few foreign clients acknowledge our help, describing us merely as nameless high-altitude porters or pretending that we don’t exist,” Mingma G. says. “It’s like they think we don’t read their articles.”

And then there were the growing tensions, as Nepali outfitters wanted more of the lucrative guiding business that for years was dominated by foreign companies. “We are the local people, and we know more than the foreign guide services do,” Mingma G. says. He acknowledges that there is fierce competition among Nepali outfitters, but “90 percent of foreign climbers, they only trust foreign companies.”

Claiming the first K2 winter summit would serve notice that Nepalis were taking their rightful place not just as participants but also as leaders in the mountaineering world. “We wanted to have one for ourselves, for history,” Nims would explain later. “It was a no-brainer to team up.”

Mingma G. woke up on New Year’s Day with a foggy hangover. Despite the subzero temperatures, he had fallen asleep in his tent without crawling into his sleeping bag. Soon he heard Nims’s voice on the radio, inviting him back to his camp for tea. They had more plans to discuss.

Sherpas like to say that a mountain must allow a team of climbers to reach its summit and return unharmed. It’s the reason every Himalayan expedition performs a Puja ceremony: to ask the mountain deities for permission to climb and for safe passage. But during the first two weeks of 2021, it was abundantly clear that K2 was not ready to welcome any humans near its apex. Hundred-mile-an-hour winds scoured the mountain for days and plunged temperatures well below zero at Base Camp, forcing everyone to hunker down in their tents.

When the winds let up slightly, Nims’s team made a quick foray up to Camp II to check on their gear. “It was a wreckage sight,” Nims wrote on Instagram. Gear they’d left for the summit push—sleeping bags, battery-heated insoles for their boots, spare mittens, and goggles—had all blown away.

But weather reports predicted the winds would calm beginning on January 14. Back at Base Camp, more gear was quickly rounded up, and another Nepali, Sona Sherpa from Seven Summit Treks, joined the group to help bring it up. Meanwhile, Nims and Mingma G. reassessed their schedule for reaching the summit. Rather than spend a frigid night at Camp IV, the traditional high camp pitched at roughly 25,000 feet for a summit bid, the Nepalis planned to reach the top in a single day from Camp III. If everything went well—a huge if—they could summit on the 15th.

Later, some climbers at Base Camp would accuse the Nepalis of hiding their plans to maintain an all-Nepali summit team, an accusation Mingma G. doesn’t shy away from. “When there is a football World Cup, do you ever want your country to lose?” he explained in an interview with ExplorersWeb. “No, never. And the team and the coach always keep the strategy secret to make those wishes possible. We were the same on K2 this time.”

By the evening of the 13th, as the Nepalis reached around 23,000 feet, the secret was out and several parties started up the mountain after them. The next morning, while those teams rested at Camp II in a biting wind, the Nepalis pushed upward to just below Camp III. “The weather played a big game,” Mingma G. says. “Below Camp III, there was big wind, and above Camp III, there was no wind at all.”

On the 15th, Mingma G. and three others set out to fix ropes above Camp III, toward a section known as the Shoulder, but as they navigated their way up the seemingly endless snow slopes, a maze of crevasses—human-swallowing cracks in the glaciated terrain—blocked their way. Just short of reaching the traditional spot for Camp IV, they encountered a huge crevasse, forcing them to backtrack for hours to find a way around it. It was the type of exhausting, morale-breaking setback that often drives mountaineers to abandon an expedition, but Mingma G. and the others pushed on. After finding a section of hardpack—a snowbridge—across the crevasse field, they fixed lines all the way to the Shoulder.

They returned to Camp III and joined the rest of the team for a few hours of fitful rest. “It was a different kind of cold,” Gelje remembers. “It made you very thirsty. It was hard to digest the food you ate.”

Sometime after midnight on the 16th, the team began to gear up to leave Camp III. For the first time on the mountain, each man donned an oxygen mask for the summit push, all except one. Nims had decided to answer his critics by climbing the Savage Mountain in winter without oxygen, a landmark achievement on top of a landmark achievement—if he could pull it off. “I wasn’t fully acclimatized. I had frostnip on three fingers,” Nims says. “If you don’t really know your ability, your capacity, you could ruin it for everyone.”

In small groups, the mountaineers began following the route up the lines Mingma G. had laboriously fixed to the Shoulder. His hard-fought effort paid off. What took eight hours the previous day now took only three in the dark, but a vicious wind had kicked up.

Feeling alone and sensing the onset of frostbite, Mingma G. was on the verge of calling off his summit attempt. But when no one answered his radio call, he resorted to his last option: kicking his feet into the ice to keep them warm. “Amazingly, it worked,” he says.

At last, the first rays of dawn hit most of the mountaineers on the Shoulder, warming their bodies. The wind dropped, and despite the still arctic temperatures, it was a perfect day. Above loomed the final crux of the route, the Bottleneck—a frozen couloir beneath an overhanging wall of ice known as a serac. Beyond the couloir, the climbers would face easy slopes leading to the summit, but if a portion of the serac collapsed while one of them was in the Bottleneck, it likely would be fatal to anyone below it. As if to remind the climbers of the danger, ominous refrigerator-size ice blocks lay scattered in a field beneath the couloir.

Mingma Tenzi and Dawa Tenjin led the team through the treacherous passage, fixing lines behind for the others to follow. As they worked their way up, small rocks clattered down the couloir, occasionally striking someone’s helmet. There was little to do but carry on.

As the group neared the summit, neither Mingma G. nor Nims was in front. That job had fallen to Mingma Tenzi, a 36-year-old rope-fixing specialist with a cheerful smile and a gold tooth. He led the team for the last few hours and could have reached the top ahead of the others, but he stopped just below the summit.

One by one, the mountaineers steadily moved up to join him. Nims labored heavily in the frozen empty air, taking two or three breaths for every step. As the sun twinkled on the gentle crest of snow draped over the second highest point on the planet, the climbers coalesced into a single group.

Reaching the summit together had been Nims’s idea, and when all 10 had gathered, they linked arms and began trudging upward. Slowly, they found their voices, and as if in a dream, the words of the Nepali national anthem came to them:

Woven from hundreds of flowers ... A shawl of unending natural wealth ... A land of knowledge and peace, the plains, hills, and mountains tall ... Unscathed, this beloved land of ours, O motherland Nepal.

Author and mountain guide Freddie Wilkinson wrote about the National Geographic and Rolex Perpetual Planet Everest Expedition for the July 2020 issue.

This story appears in the February 2022 issue of National Geographic magazine.

To learn more about Nims Purja's journey from rural Nepal to joining the legendary Gurkhas to his record-setting mountaineering exploits, check out Beyond Possible: One Man, Fourteen Peaks, and the Mountaineering Achievement of a Lifetime

Related Topics

- MOUNTAIN CLIMBING

Where to stay in Denver, gateway to the Rockies

How does the future of ski resorts look in the face of climate change?

Sleeper trains, silent nights and wee drams on a wild walk in Scotland

What you need to know about volcano tourism in Iceland

Why Pays De Gex is perfect for an adventure beyond the ski slopes

- Environment

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

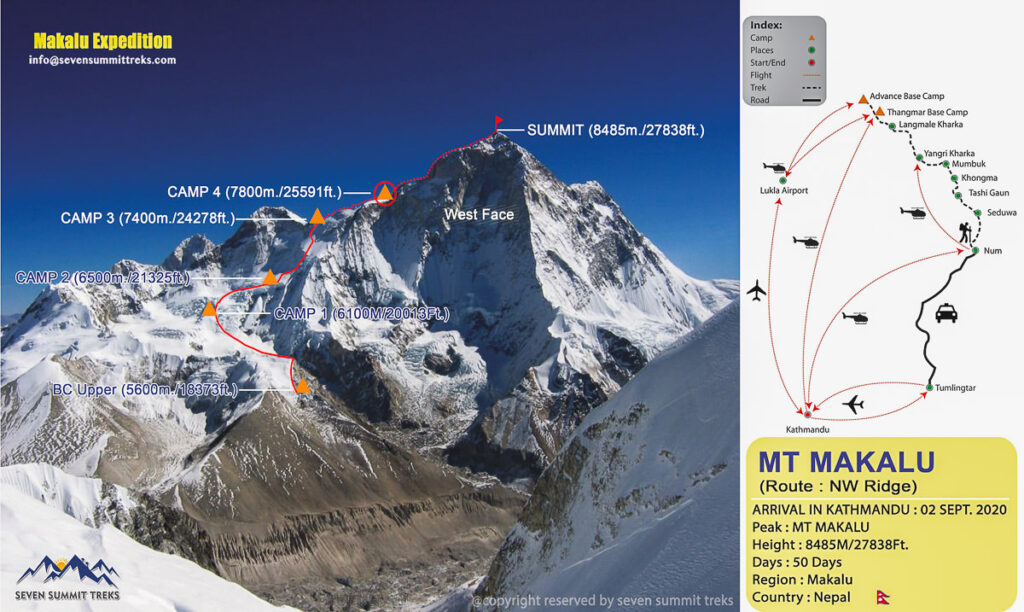

Climbing Mount Makalu (8,463m): A Complete Guide

Jackson Groves

Posted on Last updated: June 24, 2023

Categories NEPAL , HIKING

Mount Makalu, is the world’s fifth-highest mountain, reaching a lofty height of 8,463m. Located in the Mahalangur Himalayas on the border between Nepal and the Tibet Autonomous Region (China), it is situated twelve miles from Mount Everest. Makalu means ‘ Great Black One’, due to its dark rock formation although it is mostly covered in snow and ice.

Table of Contents

CLIMBING MOUNT MAKALU

I trekked into Makalu Advanced Base Camp and then successfully sumitted the peak in May of 2022. In this blog post, I will cover everything you need to know about the logistics of climbing Makalu Mountain. I’ll also share with you my stories and photos from the climb. This will give you an idea of what to expect and a great insight into the scenery you will find at each camp en route to the summit.

Before sharing my experience of the climb in the second section of this blog post, I will detail all of the information you need to know in this complete guide about climbing Manaslu Mountain.

MAKALU MOUNTAIN DETAILS

- Days required : 35-50 days

- Height of Makalu Summit : 8,463m

- Cost: $20,000

- Season to climb Manaslu : May

- Difficulty : Makalu is known as one of the more taxing 8000m peaks among the fourteen. While not extremely technical, the mountain is relentlessly steep. The advanced base camp is one of the highest in the world at 5,700m. This makes it tough to recover between rotations. As my second 8000er, I can only compare Makalu to Manaslu and it was much, much tougher. It’s important to note that I summitted with Sherpa assistance and with the use of oxygen. If you remove either or both of those factors, this climb will become significantly harder. Our summit push was base camp to base camp in 51 hours and we had favorable weather and conditions.

- Recommended prior climbs: While there are many climbs you can do to warm up for Makalu, some common options are Island Peak (6,189), Baruntse Peak (7,129m), Spantik Peak (7,030) and Himlung Himal (7,126m). In addition to these acclimatization peaks, I would recommend climbing at least one or two ‘easier’ 8000m peaks before attempting Makalu.

TRY THE 3 BEST TREKS IN NEPAL

Manaslu Circuit : My personal favorite 2-week trek through Tibetan villages and stunning scenery. Less crowded and more authentic.

Annapurna Circuit : The most beautiful & scenic 2-week trek in Nepal although can be crowded at times.

Everest Base Camp Trek : The most iconic 2-week route reaching the famous (EBC) Everest Base Camp at 5,300m.

GETTING TO AND FROM MAKALU BASECAMP

There are several different options for how to arrive and depart from Makalu Advanced Base Camp (5,700m). I’ve actually used both options listed below.

- Helicopter: These days many mountaineers can afford to fly into Advanced Base Camp via helicopter. The flight runs from Lukla. Most tour operators will organize this helicopter option as part of the package. Many in our group trekked in to acclimatize, but then flew out the day after their summit.

- Trekking in from Num: One of the most scenic ways to reach base camp is to trek on the established Makalu Base Camp Trek. This route guides you to the lower base camp and takes about 9-10 days. I did this trek with my group and wrote a comprehensive guide to Trekking to Makalu Base Camp . It’s much more remote than Everest Base Camp Trek or Langtang Valley Trek but very scenic and a chance to observe rural, mountain life in Nepal.

TOP 3 PLACES TO STAY IN KATHMANDU

- Ultimate Luxury: The Dwarika’s Hotel – Luxury, Spa-service, Pool

- Best Value : Aloft Kathmandu Thamel – Swimming Pool, Gym & Great Restuarant

- Budget Choice: Hotel Jampa is easily the top cheap hotel in Kathmandu

IS CLIMBING MAKALU MOUNTAIN DANGEROUS?

Whenever you climb to heights above 8000m, you are in the death zone. Lower oxygen, harsh weather conditions, unpredictable mountains, and tired bodies can often make for tragic circumstances.

During our expedition in 2022, there were no deaths but several serious injuries. According to statistics up until 2020, from 234 ascents there were 26 deaths making Makalu the 7th deadliest mountain with roughly a 10% death rate. This figure has dramatically improved in recent years with better conditions, equipment, and logistics provided to climbers.

WHICH COMPANY I CLIMBED WITH FOR MAKALU

I climbed Makalu with Seven Summit Treks , which is the top Nepali climbing company in the country. They offer expeditions to all of the 8000m peaks and many other climbs, treks, and logistical services. This was my fifth expedition in Nepal and Pakistan and definitely the best and most well-organized.

Seven Summit Treks were very detailed and had everything sorted. Their basecamp setup at Makalu was by far the most extensive with a dome tent for the mess hall, great food at mealtimes, and snacks always available.

MOUNT MAKALU HEIGHT

Mount Makalu is the fifth highest peak in the world at 8,463m or 27765.75ft. Below I’ve listed the different heights of each camp to give you an idea of what to expect.

- Lower Base Camp: 4,700m

- Advanced Base Camp: 5,700m

- Camp 1: 6,200m

- Camp 2: 6,600m

- Camp 3: 7,500m

- Camp 4: 7,600m

- Summit: 8,463m

MY EXPERIENCE CLIMBING MOUNT MAKALU

Makalu is known as one of the tougher 8000-meter climbs in the world but also one of the safest. It has relatively low avalanche risk and fewer crevasses than many of the other big mountains throughout the Himalayas and the Karakoram. It may have been a false sense of security, but it felt like the biggest challenge with this climb was going to be against my own body and the stress of the death zone. Time would tell.

GETTING TO THE TRAILHEAD

Our journey began in Kathmandu. We took a flight to Tumlingtar airport to begin our expedition. Unlike most climbs that transit via Lukla, the Makalu climb is much more remote. From Tumlingtar, a 6-hour jeep ride along muddy roads led us to the small village of Num. Here we rested for the night before beginning our trek to base camp the next day.

I’ve written an entire guide to the Makalu Base Camp Trek . In that article, you will find a day-by-day breakdown of the hike through to Makalu Base Camp. With more than 100 photos and descriptions of the route, it’s a handy guide to give you an idea of what to expect.

TREKKING TO THE BASE CAMP

The trek is quite an adventure. There’s usually just one tea-house in each village and very few shops or snack stores along the way. You could say it is much more ‘authentic’ than trekking in the Khumbu where you will find bakeries, bars, internet cafes, and plentiful restaurants along the route to Everest Base Camp. Along this undulating route, life is simple and most families are working the land.

The journey into base camp took us about 10 days, including a few rest/acclimatization days. The trek begins at an elevation of 1500m but actually drops down to 700m immediately. The Makalu Advanced Base Camp sits at 5700m so in altitude change you are grabbing more than 5000m. The actual incline is almost double that with lots of undulation along this trail so expect to work some hills.

LOWER MAKALU BASE CAMP

We arrived at Lower/Real Makalu Base Camp (4700m) and stayed for a few nights to rest and acclimatize. From this base camp, you can hike up to a ridge above the camp for an epic view of Everest and Lhotse down the far end of the glacier. The views of Makalu summit are also perfect on most mornings.

At the lower base camp, there’s a tea-house and some cabins but most outfitters bring their own tents as the capacity is limited. This will be the last time you sit around a yak-poop-powered heater and have a ‘stable’ home.

TREKKING TO UPPER MAKALU BASE CAMP

From Lower Base Camp to Upper Base Camp it’s a hard day of trekking. With 1000m of vertical gain reaching a height of 5,700m, it is quite a challenging day. To compound the elevation gain, the terrain is almost entirely comprised of unstable rocks and gravel.

The path is unclear, rockfall prone, and often finds itself blown through by dust storms. It seems to go on forever with a lot of the incline coming late in the day to reach the base camp. Prepare for a tough day and pack at least two liters of water to combat the lack of shade on this route.

MAKALU UPPER BASE CAMP

After 12 days of trekking, we finally reached our home base. Makalu Upper Base Camp, at an altitude of 5,700m would be our climbing pad for the next 30 days as we tried to make an ascent of Mount Makalu. Seven Summits Treks had set up an awesome little village with two rows of sleeping tents and a large, dome dining tent. It seemed like a relatively safe base camp with views of the glaciers and the summit (on clear days).

Now, the plan depends on how the climbers in the group feel and the weather conditions for rotations and the summit push. However, first things first. I’ll give you a little description of what to expect at base camp with Seven Summits Treks . Each person has a large, insulated, private tent, which is big enough to house your two duffels of gear and a thick mattress.

The toilet is basically a small tent with a bucket that is beneath the rocks and is emptied regularly. It’s basic but it works.

Each day we had breakfast, lunch and dinner served in a warm dome tent. The quality of the food was great overall and had a good mixture of western dishes and Nepali classics. Throughout the day, snacks and drinks were always ready and available to keep you nourished.

MAKALU PUJA CEREMONY

After a couple of acclimatization days at base camp, our bodies began adjusting to living at 5,700m. It was time for the Puja ceremony. The Puja Ceremony is a tradition where the mountains are honored and we pray for safe passage. Local Sherpa people consider these mighty peaks to be Gods, and so the Puja ceremony is held not only to ask for safe passage but forgiveness for climbing up to these holy places.

In this section of the blog post, I will explain what to expect in each section of the climb, and provide ample photos of each part of the route. Most of our group was climbing with oxygen and planned to sleep at Camp 2 for acclimatization and touch a little higher. Many opted for just one rotation before a summit push but others went for two.

SIDE NOTE: I actually had a bit of a crazy experience on this expedition and was evacuated by helicopter halfway through and flown back to base camp for my summit push 12 days later. I’ll add that personal story below at the end of the blog post if you are interested.

MAKALU UPPER BASE CAMP TO CAMP 1

This is a tricky little section as it appears to be quite short but it actually takes about four hours for many average-paced climbers. Camp 1 used to be on a lower plateau but an ‘Upper’ Camp 1 is now the standard position. It involves about an extra hour and now includes a steep climb underneath a massive cornice.

From 5,700m at Upper Base Camp, you will reach 6,300m at the ‘real’ Camp 1. The journey begins out of Upper Base Camp across the frozen lake. By the end of the expedition, several members were falling in here up to their knees so watch out for that fun!

Once across the lake, you follow the rocky path along the edge of the glacier. It’s a beautiful scene looking back across the glacier towards the camp, which slowly fades away into the distance.

After about forty minutes, you reach a steep rocky wall that requires the use of ropes for most people. You won’t need to clip in here but just use the ropes as safety as you clamber up the cliff face for twenty meters. One of our members fell here on the descent and cracked their skull open, nearly dying. It may look easy and dry but can still pose a danger.

Once atop the cliff wall, you now walk for another 25 minutes up the ridge to reach the crampon point. Here Seven Summit Treks had installed a tent where we could store our 8000m boots, harness, and crampons. There were a few heavenly snacks and drinks tucked away in there for summit day descents also!

Just after crampon point is a small lake, where more members of our team actually fell hip deep into the water. Don’t take these frozen lakes lightly. You now step onto the snow for the first time and make your way up the left-hand side of the glacier, hugging the rocky cliffside all the way up to the Lower Camp One plateau. This section can be brutally hot and exposed.

A wide-open space signals Lower Camp One, but nowadays you still need to head up the steep ice underneath the cornice to reach the official Camp One. This is the only time you will use your jumar on the way to Camp One and only for several pitches.

At the top of the climb, you will walk just another fifty meters to reach the tents. It sits on the edge of a huge plateau and we actually slept here one night, although most go directly to Camp Two as it is only another 1.5-2 hours to reach the next camp at 6,600m.

CAMP 1 TO CAMP 2

This is by far the shortest and easiest camp-to-camp journey on the whole route. It takes about 1.5 hours to reach Camp 2 from Camp 1.

You’ll find a couple of steep snowy slopes that can require the use of a jumar but otherwise, you are just clipped in for a few sections to be safe from drop-offs and crevasses. It’s about 300m of incline to the second camp, which sits at 6,600m. Most people skip Camp 1 and head straight from advanced base camp to Camp 2 on their rotations and during their summit push.

CAMP 2 TO CAMP 3

Aside from the summit push, this is the toughest part of the climb. It’s also very likely that you will climb this section without oxygen even if you are attempting to climb with oxygen. This makes it even more challenging as you will ascend from 6,600m to 7,500m to reach Camp 3 in very thin air. Those decisions are up to you, but no oxygen at 7,500m climbing steep slopes is starting to get intense.

The journey begins out of Camp 2 with a relentlessly steep slope up towards the rocky incline. Fixed ropes will lead you to the start of the rock and ice section. Once there, the terrain becomes quite challenging with a mixture of hard ice, rocks, and snow.

The route twists and turns and you could say this section requires some technical know-how. From maneuvering through the rocky terrain to selecting the correct ropes, it is physically and mentally draining to ascend through this part of the route.

Several times on the route from Camp 2 to Camp 3 you will reach a plateau, only to be thrown back into the same steep, rocky incline. For quick climbers, you can expect a 6-7 hour journey and for slower climbers, it will take closer to 9-10 hours.

Camp 3 sits on the Makalu La, which is the ridge you often look up to from an advanced base camp. Once you reach the ridge, the campsite is just a few minutes away in a small clearing.

CAMP 3 TO SUMMIT (SUMMIT PUSH)

There are many ways to do the summit push of Makalu and it all depends on the weather, your ability, and conditions. We decided to sleep for two hours once we reached Camp 3 and then set off at 8 pm on our summit push. It seems that very few people use Camp 4 as it is only a simple, one-hour traverse from Camp 3.

The journey from Camp 3 to the summit will take fast experienced climbers anywhere from 6-8 hours. For slower and more inexperienced climbers you could expect closer to 9-10 hours but of course, these are just estimates. On the day I summited it was just myself and my Sherpa and one other group of two, who were quite experienced climbers. It took me nine hours to reach the summit while they made it up there an hour earlier.

The route begins with the relatively flat traverse to Camp 4. Once we passed Camp 4, we navigate a blue ice section before the steep climbing begins. The incline on this day never seems to end and there were few plateaus or flat areas to rest. It was very steep all morning.

The route weaves in and out of the ridges with no rock or technical work until the final French Couloir. There were minimal crevasse fields and we had fixed ropes throughout the route to navigate any ominous areas. Basically, until the sun began to rise at the French Couloir, it was a slow slog up the steep, snowy slopes.

At the French Couloir, you need to switch on and direct your focus to the technical terrain. It’s a short climbing section with ten or more pitches on the ropes. The interesting part here is that you are tired and trying to focus on technical movements all while at 8,300 meters. This is a challenging part of the route but not vertical at any point and handholds are plentiful.

Once passing the French Couloir, the view opens up and you have reached the summit ridge. Everest and Lhotse appear and you have panoramic views. Once reaching this point it seems that you have ‘made it’.

However, when you look to the right, you may think you are looking at the final summit but it is the false summit. The true summit is hidden on the other side. Once you reach the summit ridge, you still have about 15-20 minutes of traversing to reach the actual summit.

The traverse along the summit ridge is at times very narrow. Quite literally it is a single step cut into the cliffside. With a rope for safety to clip in, it may feel safe but this is still a big drop. Many stories of people only reaching the false summit due to no fixed ropes had circulated before our climb.

Thankfully for our team, the Sherpa rope fixing team had fixed all the way to the false summit and then continued to the true summit, making it a much easier task for our team.

About an hour after sunrise, Tashi Sherpa and I arrived at the true summit to enjoy the experience with no crowd, in complete peace. The photo above is from Pema’s summit push with her group, which is why there is a crowd. We had seen the lights on Everest earlier and knew there were climbers on top of the world looking back at us also. We had made it to the top of the fifth highest peak in the world.

The journey down is quite long and we actually descended all the way back to base camp by 3 pm that day. It was a 51-hr summit push from base camp to base camp and one of the biggest mental and physical challenges of my life. Incredibly tough but incredibly rewarding.

MY EXPERIENCE TO REACH THE SUMMIT OF MAKALU

The summit of Makalu (8,463m) 🙏🏽 I almost didn’t make it but here I am. I had to leave the expedition in a heli-evacuation after 20 days, having slept at Camp 2 (6,600m) with the left side of my face numb. I couldn’t sleep and had constant headaches. I had no choice but to leave the expedition.

I landed back in Kathmandu and had MRI, X-ray, and multiple other scans. It turns out the pressure from altitude had exposed necrosis/infection in my gum from a previous motorbike crash 10 years ago.

I had surgery immediately and was taking a handful of drugs day and night. I was doubtful, but not ready to give up on my Makalu Expedition.

3 days later I flew back to Lukla (2,860m) and waited 9 long days for a helicopter back to the advanced base camp (5,700m). With just one solid weather window left, I didn’t have a good chance for another rotation before the summit push.

So on the 18th, I set off with Tashi Sherpa to Camp 2. On the 19th we climbed nine hours to reach Camp 3 (7500m). After a one-hour sleep at Camp 3, we set off on our summit push at 8 pm. Up the relentlessly steep slopes of Makalu, I battled mentally but knew I would never turn back.

Tired but defiant, we reached the empty summit just after sunrise to take in all of the incredible Himalayas. Behind me (end of the video) you can see Everest and Lhotse from our perch of 8,463m on top of the mighty Makalu Mountain 🏔

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Jackson Groves (@jackson.groves)

HAVE YOU READ MY OTHER NEPAL BLOGS?

I’ve been lucky enough to have many awesome adventures in Nepal, which you can check out below where I’ve listed some of my favorite blog poss from Nepal.

- The Most Iconic route: Everest Base Camp Trek

- The Most Scenic Route: Annapurna Circuit Trek

- My Favorite Trek in Nepal: Manaslu Circuit Trek

- An Easy Nepal Trek: Langtang Valley Trek

- A great beginner peak: Island Peak Climb (6,165m)

- My Favorite Climb in Nepal: Climbing Ama Dablam (6,812m)

- My first 8000er: Climbing Manaslu (8,163m)

- My toughest climb in Nepal: Climbing Makalu (8,463m)

- Where to stay: 16 Best Places to Stay in Kathmandu

Seven Summit Treks

- About the Seven Summits

- Everest (Asia)

- Vinson Massif (Antarctica)

- Aconcagua (South America)

- Elbrus (Europe)

- Mount Kilimanjaro (Africa)

- Denali (North America)

- Carstensz Pyramid (Oceania)

- Kosciuszko (Australia)

- Explorer’s Grand Slam

- Ecuador Volcanoes Expedition

- Australian Alpine Academy

- Mt. Baker (USA)

- Lhotse (Nepal)

- Manaslu (Nepal)

- Cho Oyu (Tibet)

- Ama Dablam (Nepal)

- Lobuche East (Nepal)

- 3 Peaks (Nepal)

- First Ascent (Nepal)

- Rugged Luxury Everest Base Camp Trek & Stay

- Everest Base Camp Trek (Nepal)

- North Pole Last Degree Ski (North Pole)

- South Pole Last Degree Ski (Antarctica)

- Orizaba Express Mexico Trek (Mexico)

- Mt. Rainier (USA)

- Mont Blanc (France)

- About Us / Why CTSS

- How to Apply to CTSS

- Employment Opportunities

- CTSS’ “No D*ckheads” Policy*

- Letter to your Loved Ones

- Success & Testimonials

- Marginal Gains Philosophy

- CTSS Guides & Team

- Mike Hamill

- Climbing Education

- Climbing Gear Advice

- Female Climber Considerations

- Trip Insurance

- Our Speed Ascents

Our Everest season is truly underway.

We have welcomed climbers and trekkers from all over the world to Kathmandu and our First Wave (Western Guided Team Climbers, Rugged Luxury Trekkers, 3 Peaks Climbers) have flown into the Khumbu valley on helicopters and trekked to the riverside town of Phakding.

Today they will launch up to Namche: 11,286 ft (3,440m) which will take them between 5-6 hours and they will gain +2,723ft (830m) in elevation. The trail starts by weaving its way through lush Rhododendron forest, along the river banks, up over some thrilling suspension bridges that span across the raging glacial-fed Dudh Khosi River before tackling the 2,000ft (610m) Hill that leads to Namche Bazaar.

The first of the treks’s challenging climbs, it’s best to take it slow and steady and make use of the well built stone terraces to stop, rest and enjoy the views. They are in no rush, and their bodies are beginning their acclimatization process so they can expect to be a bit breathless!

Terraced into the hill side in a C shape, Namche Bazaar is the Sherpa capital, a brilliant, vibrant town, filled with fun little shops, great bakeries and cafes and narrow winding pedestrian streets.

Meanwhile, The Crum Family are enjoying a custom itinerary with added acclimatization days in Lukla and they will fold into our second wave tomorrow and trek to Phakding.

In Kathmandu; our Second Wave (Our Private 1:1 Climbers & our EBC & Gokyo Trekkers) have settled in and today will do their gear checks and expedition briefing at the Hyatt, before readying themselves to fly into the Khumbu Valley by helicopter tomorrow.

All is well and happy in Nepal.

Cheers CTSS Team

File : Lit Tents of Seven Summit Treks seen at Everest Basecamp, background Nuptse mountain..jpg

File history, file usage on commons, file usage on other wikis.

Original file (1,280 × 854 pixels, file size: 498 KB, MIME type: image/jpeg )

Summary [ edit ]

Licensing [ edit ].

- to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work

- to remix – to adapt the work

- attribution – You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

- share alike – If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same or compatible license as the original.

Click on a date/time to view the file as it appeared at that time.

You cannot overwrite this file.

The following 2 pages use this file:

- ཇོ་མོ་གླང་མ

- User:Adeletron 3030/botgalleries/Sports/2020 September 4-6

The following other wikis use this file:

- Seven Summit Treks

This file contains additional information such as Exif metadata which may have been added by the digital camera, scanner, or software program used to create or digitize it. If the file has been modified from its original state, some details such as the timestamp may not fully reflect those of the original file. The timestamp is only as accurate as the clock in the camera, and it may be completely wrong.

Structured data

Items portrayed in this file, copyright status, copyrighted, copyright license, creative commons attribution-sharealike 4.0 international, captured with, source of file, original creation by uploader.

- Everest Base Camp - South (Nepal)

- Tents in Nepal

- Night in Nepal

- CC-BY-SA-4.0

- Self-published work

Navigation menu

Welcome to Seven Summit Treks & Tours

Seven Summit Treks and Tours (SSTTP) is operated by individuals for whom travel is not simply an interesting job, but an all consuming passion. SSTTP believes that travel should not simply be a business, but a way of exploring and understanding the world and the diverse cultures that inhabit our globe. Read More

Trekking in Pakistan:

Most popular treks in pakistan includes

K2 Base Camp Via Gondogoro La Trek

K2 Base Camp and Concordia Trek

Adventure In K2 Base Camp.

Nanga Parbat

K2 Expedition

Trekking in Pakistan

Most popular treks in pakistan includes K2 Base Camp Via Gondogoro La Trek, K2 Base Camp and Concordia Trek, Adventure In K2 Base Camp.

Fixed Departures

JOIN OUR FIXED DEPARTURE GROUPS 2022 IN PAKISTAN. TREKKING IN PAKISTAN.

Need to speak with a specific Adventure ?

Schedule a call

About Us: Today’s world adventure is becoming mainstream, and is increasingly losing the element that makes it so special – real adventure. Too often the promises made aren’t kept – how often have you read that you’ll get to ‘meet the locals’ and been disappointed in the brief encounter that’s delivered, or that you’ll stay in a ‘local home’ to discover it’s little more than a hotel? Read More

COMMENTS

Seven Summit Treks, is a commercial adventure operator, based in Kathmandu, Nepal. They are specialized in the Eight-thousanders of Nepal, China, and Pakistan. [1] It was established by four Sherpa brothers, [2] Mingma Sherpa, Chhang Dawa Sherpa, Tashi Lakpa Sherpa and Pasang Phurba Sherpa. Mingma and his brother Chhang Dawa are the first ...

The Seven Summits are the highest mountains on each of the seven traditional continents. Reaching the peak of these summits is considered a significant achievement amongst many mountaineers, alongside many other such goals and challenges in the mountaineering community. On 30 April 1985, Richard Bass became the first climber to reach the summit ...

On 27 July 2023, Harila and Tenjen Sherpa, a guide from Seven Summit Treks, established a new record summiting all 14 true geographic summits in just 92 days. [7] [14] [1] [15] [2] In the process, Kristin and Tenjen broke multiple records, including 26 eight-thousander summits in one year and three months and also the fastest Everest and Lhotse ...

ASIA. 8848m / 29,029 ft. Everest is often the final step in the progression of the Seven Summits. It is also quite common for people to leave Mt. Vinson until after climbing Everest, but we would recommend at a having climbed Kilimanjaro, Elbrus, Aconcagua, Carstensz Pyramid, Denali, and Vinson before taking on the highest of the Seven Summits.

Jake Norton/Courtesy of Alison Levine. At least 11 climbers died on Mount Everest last month, including two Americans in pursuit of joining the Seven Summits Club, a select group of roughly 500 ...

The Seven Summits are defined as Everest (Asia) 8,850m, Aconcagua (South America) 6,961m, Denali (North America) 6,194m, Kilimanjaro (Africa) 5,895m, Elbrus (Europe) 5,642m, Vinson (Antarctica) 4,892m, Carstensz Pyramid (Australasia) or Kosciuszko (Australia) 2,228m. Though several experienced mountaineers had reached the summit of five or six ...

A trio of brothers—Mingma, Tashi Lakpa, and Chhang Dawa Sherpa, the principal owners of Seven Summit Treks—realized that Pakistan was one of the few mountaineering destinations still open in ...

Seven Summit Treks, Kathmandu, Nepal. 49,905 likes · 1,634 talking about this · 234 were here. An official mountaineering company, based in Kathmandu, Nepal, organizes climbing expeditions over al

Mt Dhaulagiri Expedition. 5.0. Big Boss who wants we (members) summit. Good, very good and nice nepali staff. Last weather forecasts. Experiences shared from 14 = 8000meters summiteers. Immediate rescue operations. Marvelous surprises.

Seven Summit Treks were very detailed and had everything sorted. Their basecamp setup at Makalu was by far the most extensive with a dome tent for the mess hall, great food at mealtimes, and snacks always available. MOUNT MAKALU HEIGHT. Mount Makalu is the fifth highest peak in the world at 8,463m or 27765.75ft. Below I've listed the ...

Mt. Everest Base Camp Trek. Annually: April 3rd - April 22nd - $5,495 USD. The Everest base camp trek is widely heralded as the best trek in the world, and for good reason. This trek takes you from Kathmandu by plane to Lukla at the head of the Khumbu valley. From there you trek roughly 40 miles/70 km through the lush green pastures ...

Seven Summit Treks est un « opérateur d'expédition » commercial basé à Katmandou, au Népal.L'entreprise est spécialisée dans l'organisation d'ascension des sommets de plus de 8000 mètres du Népal, de la Chine et du Pakistan.Créée en 2010 [1] par quatre frères Sherpas, Mingma Sherpa, Chhang Dawa Sherpa (directeur), Pasang Phurba (le plus jeune) et Tashi Lakpa Sherpa (en).

Add Review Log In / Sign Up. Home /; seven summit treks /; 4.8 4 Reviews

Manaslu (/ m ə ˈ n ɑː s l uː /; Nepali: मनास्लु, also known as Kutang) is the eighth-highest mountain in the world at 8,163 metres (26,781 ft) above sea level.It is in the Mansiri Himal, part of the Nepalese Himalayas, in west-central Nepal.Manaslu means "mountain of the spirit" and the word is derived from the Sanskrit word manasa, meaning "intellect" or "soul".

5) Denali. North America. 6914m / 20,322 ft. Denali is probably the most strenuous of the Seven Summits. It requires that climbers know advanced glacier skills, rope team travel, and involves heavier load carries. The weather is more unstable than Everest and Vinson, making it a great challenge and incredible training for an Everest climb.

The trail starts by weaving its way through lush Rhododendron forest, along the river banks, up over some thrilling suspension bridges that span across the raging glacial-fed Dudh Khosi River before tackling the 2,000ft (610m) Hill that leads to Namche Bazaar. The first of the treks's challenging climbs, it's best to take it slow and steady ...

Mountain climbers that have summited all the Seven Summits peaks. Pages in category "Summiters of the Seven Summits" The following 75 pages are in this category, out of 75 total. This list may not reflect recent changes. A. Premlata Agrawal; Rick Agnew; Israfil Ashurly; Murad Ashurly ...

Usage on en.wikipedia.org Seven Summit Treks; Metadata. This file contains additional information such as Exif metadata which may have been added by the digital camera, scanner, or software program used to create or digitize it. If the file has been modified from its original state, some details such as the timestamp may not fully reflect those ...

Welcome to. Seven Summit Treks & Tours. Seven Summit Treks and Tours (SSTTP) is operated by individuals for whom travel is not simply an interesting job, but an all consuming passion. SSTTP believes that travel should not simply be a business, but a way of exploring and understanding the world and the diverse cultures that inhabit our globe.

Companies portal; This article is within the scope of WikiProject Companies, a collaborative effort to improve the coverage of companiesWikiProject Companies, a collaborative effort to improve the coverage of companies

140 likes, 2 comments - sevensummittreks on April 28, 2024: "• Sagarmatha (Everest) route update ! The team of Sherpas from Seven Summit Treks, under the management ...

From Kala Patthar, west of Everest looking the South West face primarily Mount Everest from Gokyo Ri, showing a little more of the North face Tashi and Nungshi were the first twins to summit Mount Everest together. This article lists different records related to Mount Everest.One of the most commonly sought after records is a "summit", to reach the highest elevation point on Mount Everest.

Kangchenjunga, also spelled Kanchenjunga, Kanchanjanghā and Khangchendzonga, is the third-highest mountain in the world.Its summit lies at 8,586 m (28,169 ft) in a section of the Himalayas, the Kangchenjunga Himal, which is bounded in the west by the Tamur River, in the north by the Lhonak River and Jongsang La, and in the east by the Teesta River.

The Seven Summits are the highest mountains in each of the seven continents Subcategories. This category has the following 8 subcategories, out of 8 total. Summiters of the Seven Summits (74 P). Seven Second Summits (2 C, 11 P) Seven Third Summits (10 P) Volcanic Seven ...