Find anything you save across the site in your account

This Is How Star Trek Invented Fandom

By Molly McArdle

In the desert in early August, the temperature nudges 100 degrees, even as the sun dips below the horizon. It’s the end of day three of the five-day Star Trek Las Vegas 50th Anniversary Convention, and I am outside, at a Star Trek wedding.

Rows of seats are full of people in costume: there’s Ambassador Soval from Enterprise , Lore from The Next Generation , a Trill wearing an Original Series uniform, a member of the Borg. By the makeshift altar, the groom stands in the dress uniform Picard wore to Riker and Troi’s wedding in Nemesis , flanked by two rosy-cheeked boys in gray suit-vests pinned with Next Generation -era combadges. For a moment it looks like the real thing: the crew of the starship Enterprise has landed on a strange new world, which also happens to be the emptied pool area of the Rio Hotel and Casino.

When it’s time, the sound system plays an orchestral version of “The Inner Light,” a melody Picard performs on his flute in a Next Generation episode of the same name. The officiant takes out an Original Series communicator and at the bride’s arrival flips it open—a familiar motion to anyone who owned a cell phone in the mid-aughts. “I was told to say, ‘Kirk to Enterprise, please beam up three of us.’” He laughs. “We gotta have fun right?”

Greg and Michelle Imeson, newly married, host a reception in their suite. Figurines of Riker and Troi crown the cake, and cupcakes are dotted with Starfleet insignia. Greg shows me his wedding band, a starboard-side view of the Enterprise engraved on the outside. At the clinking of plastic cups, Gage Leusink, one of the gray-vested boys at the altar and Michelle’s seven-year-old son, begins his toast. “May my mom and dad live long and…” He fumbles on prosper. One guest teases him, “Prospect like for gold?” But Gage recovers, ably. “Long live my mom and dad’s love.”

This is what Star Trek fandom looks like a half century out: dizzyingly diverse, good-willed, extraordinarily (if inadvertently) influential, equal parts goofy and moving. But conventions, like weddings, are expensive and labor-intensive events that paradoxically celebrate something freely and effortlessly given—affection. Star Trek Las Vegas is perhaps the largest meeting of pop culture’s most famous fandom and certainly its priciest. The questions hover above the convention like a cloud of Tachyon particles: to whom does Star Trek really belong? How much, exactly, is that worth?

With 50 years and just under 550 combined hours of television and film to reckon with, Star Trek, like the curvature of the earth, is a phenomenon almost too big to notice, much less to consider in full. The franchise created the template for fandom, transformed sleepy science fiction get-togethers into celebrity-driven media events, pioneered the licensed merchandising operations that make tentpole movies (from Star Wars to Spider-Man ) possible, and anticipated— even inspired —the creation of future technologies. Star Trek invented nerd culture as we know it today.

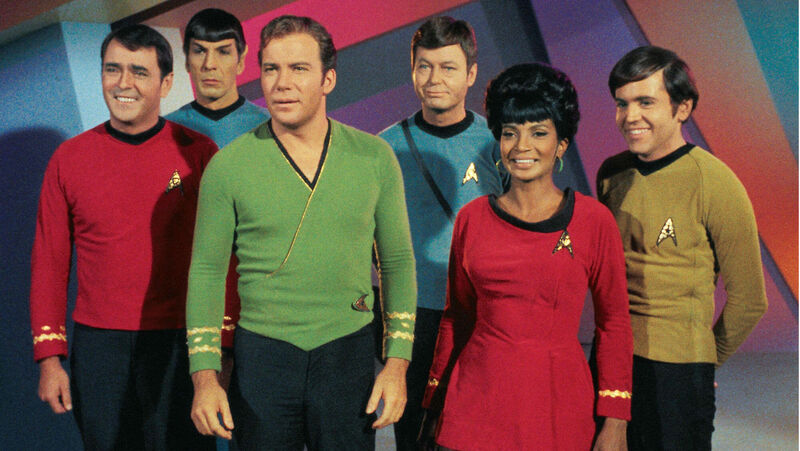

The first episode of Star Trek , what fans now call The Original Series (or simply TOS ), premiered on September 8, 1966 on NBC. Gene Roddenberry, the former Air Force pilot turned LAPD beat cop turned television writer, promised network executives a kind of space western. Kirk, Spock, and Bones were like gunslingers, albeit with a different guiding ethos, moving from planet to planet, solving each community’s problems in the span of a single episode. The connection was explicit and eminently quotable: “Space, the final frontier.”

But he also snuck in a cerebral, utopian bent. The show hired established sci-fi writers: Harlan Ellison went on to win a Hugo for his script for “The City on the Edge of Forever,” wherein Kirk must choose between a woman he loves and the rightful course of human history—arguably the greatest episode in franchise history. Star Trek also depicted a society absent of poverty, war, or inequality. The most visible proof of this was the crew itself: Roddenberry created an international—even intergalactic—cast of characters.

While that vision wasn’t a perfect microcosm of the world at large, now or in 1966, it was still a radical one. When Nichelle Nichols, who played Uhura, considered leaving TOS after the first season, Martin Luther King, Jr., who watched the show with his family, urged her to stay on. (“We don’t need you to march,” she says he told her, “You are marching. You are reflecting what we are fighting for. For the first time, we are being seen the world over as we should be seen.”) Star Trek touched a cultural and critical chord—Leonard Nimoy was nominated for an Emmy three years in a row; his ears, instant icons—but the show didn’t get the ratings it needed. NBC canceled it in 1969.

“We're pretty sure that the Trek community you see today would not have existed but for us,” Bjo Trimble says. “Not bragging.” Special guests at Star Trek Las Vegas (and a host of other 50th anniversary events), Bjo (pronounced “Bee-joe”) and her husband John are Star Trek’s ur-fans, the determined couple who saved the franchise.

They’re both in their eighties now: John wears red cap with a blue Vulcan salute on the front, Bjo has a streak of brilliant pink hair floating in her cloud of white. She’s the more loquacious of the two, but, she insists, “the whole Save Star Trek campaign was John’s fault.” They had heard the show was being cancelled in 1968, after its second season, during a visit to the studio lot. At John’s suggestion, the two launched a letter-writing campaign—all mimeographs and postal mail. It was the first ever to save a TV show, and the first time any fan community had flexed its collective muscle.

“NBC came on, in primetime, and made a voice-over announcement that Star Trek was not canceled, so please stop writing letters,” Bjo adds with pride.

TOS ’s third and final season premiered with “Spock’s Brain,” commonly held to be one of the worst episodes of all time. (“We’re responsible for there being a third season,” John admits, “we’re not responsible for the third season.”) But by the run’s end, with a grand total of 79 episodes—barely making the minimum threshold— Star Trek could enter syndication. It had earned a second life.

In the long winter between 1969, TOS’s cancellation, and 1979, the year Star Trek: The Motion Picture came out, fandom bloomed. The three syndicated seasons of TOS often aired daily and in order: fans could watch again and again. The Animated Series , which ran for two seasons and featured the voices of the original cast, won a Daytime Emmy. Jacqueline Lichtenberg founded the Star Trek Welcommittee, which introduced new fans to the growing community. Bjo Trimble published her encyclopedic Star Trek Concordance , a reference work she first printed and assembled in her basement. Hundreds if not thousands of zines were printed and shared. Writers—overwhelmingly women—told stories using TOS characters set in the Star Trek universe. And though intertextual literature has existed for as long as literature (see Homer), this was the first time a community of fans was writing for an audience of each other. From this body of work emerged the subgenre of slash, stories about a romantic and/or sexual relationship between Kirk and Spock, named after the punctuation in the abbreviated category title “K/S.” (Today, slash includes any fanfiction that pairs two characters of the same sex.) Fan clubs formed. Collectors collected. People constructed their own props and costumes. Narrated slideshows, collages of sound and discarded film stills—the progenitor of everything from formal fan films to casual YouTube fan videos—were shown at gatherings. And in 1976, following another write-in campaign orchestrated by the Trimbles, NASA unveiled its first space shuttle: the Enterprise .

Conventions sprouted up everywhere. The first took place on afternoon in 1969 at a branch of the Newark Public Library. There were no celebrities, and it was only locally advertised, but three hundred people showed up. “Star Trek Lives!”, in 1972, was the first gathering to feature guests. Manhattan’s Statler Hilton (now the Hotel Pennsylvania) hosted Gene Roddenberry, Majel Barret, Isaac Asimov, Hal Clement, and D.C. Fontana; a real NASA space suit; and never-before-seen blooper reels. The organizing committee expected 500 attendees: 3,000 arrived. The actors joined in the next year, and never left.

The sheer number of fans, and the high percentage of both women and young people among them, rubbed many older, maler sci-fi buffs the wrong way. Who were these people showing up at their club meetings, at their conventions? Why were they so excited? Had they ever even read a book? They nicknamed Star Trek fans Trekkies—after groupies. The comparison to contemporary music’s young, female, and so also hysterically obsessed fans was meant to be unflattering.

Joan Winston, who, with Jacqueline Lichtenberg, helped organize the 1972 Statler convention and co-authored Star Trek Lives , a 1975 book documenting the phenomenon of Star Trek fandom, elaborates on this in Trekkies 2 : “I would always say to people, ‘Trekkies are kids who run down the aisle screaming ‘Spock!’ I’m a Trekker. I walk down the aisle.’”

The brute force of fan enthusiasm (and, to be sure, the financial success of the first Star Wars ) resurrected the franchise. The movies, of which there are now thirteen, began in 1979. The Next Generation ( TNG ) premiered in 1987, and until 2005, when Enterprise ( ENT ) was cancelled, there was always at least one Star Trek show on television, if not two. For some fans who, between TOS ’s premiere in 1966 and TNG ’s 21 years later, studied the original 79 episodes like a holy text, there would be only one Star Trek. But for many others, the eighties and nineties were Star Trek’s high water mark. Critically acclaimed and financially successful, Star Trek was genuinely popular.

“In the early nineties, we were doing 120 conventions a year.” It’s Friday afternoon in Vegas and two lackadaisic, suited men—Gary Berman and Adam Malin—sit on the mainstage of the “Leonard Nimoy Theater” (the Rio’s biggest ballroom) for a “Special Panel with the Co-Owners of Creation Entertainment!” Malin and Berman founded the company, which puts on fan conventions, as young comic book fans in 1971. They got in on the Star Trek market in the 1980s, and have been licensed as the official Star Trek convention since 1991. The 50th anniversary convention in Las Vegas, potentially the largest Star Trek convention ever, is a Creation event. But the nineties was their heyday. “We were doing like four or five shows a week,” Malin says. They look, after so many years in the business, more like loan sharks than sci-fi fans.

“People weren’t doing it for profit,” Mark Altman says of Star Trek’s early conventions. “They were doing it for love.”

“I was there for that first Star Trek convention in ’72,” Edward Gross adds. Both he and Mark coauthored the exhaustive two-volume oral history of the franchise, The Fifty Year Mission . “What struck me about it and subsequent cons through the mid-1970s is that there was a ‘hand-made’ feel to them. I remember sitting in large rooms where episodes were projected on the screen, and the audience said the lines along with the actors. It was a pre- Rocky Horror experience.”

Starting in the 1980s, Creation began to offer special guests substantial amounts of money to appear at their for-profit events rather than at fan-run functions. In the early years, says Mark, the actors “would show up at the conventions because they were just so flattered people cared about the show.” But, according to the Trimbles—who ran their own local convention, Equicon, in the 1970s—Creation deliberately scheduled their star-studded events on the same dates as long-running fan conventions, effectively driving them out of existence.

“It’s much more commercial now,” Mark continues, referring to the practice of tiered seating as well as paid autograph and photograph sessions. It’s a business model Creation pioneered. Pricing for the 50th anniversary convention ranged from $50, for a single day of admission early in the week, to $879, for the “Gold Weekend Admission Package,” which they describe in Trumpian hyperbole as “THE VERY BEST MOST UPSCALE WAY TO ATTEND THE ENTIRE CONVENTION.”

At the exclusive dance party for Gold Package and Captain's Chair (the next most expensive ticket, at $689) attendees, a man asks after a piece of Star Trek jewelry I’m wearing. I confess I didn’t buy it. He sighs. “I don't have any money left to spend anyway,” he says, “I spent it all on getting here.” I nod in commiseration. “It’s a show about a society with no money!” he says. “I spent all my money on a show about a world without money!”

Ronald Aponte of Florida, dressed as the character Darmok.

Danielle Baker and Alex Diehl, hired models.

Cosplayers on day 5 of Creation Entertainment's Official Star Trek 50th Anniversary Convention

Star Trek dog sits in the Captain Chair

After five days without sunlight or fresh air, alongside a small army of uniforms and aliens and uniformed aliens, I wonder if this is what it’s like to live on a starship. In an area called Quark’s Bar, Data picks through a bean salad. Cell phones, when they go off, chirp like TOS communicators or intone the theme song to TNG . Klingons hold open doors. From behind, or even the side, employees on the casino floor—at both the Rio and my own hotel—start to look like Starfleet officers: their uniforms have the same solid color palette, the same black collars. And outside, in Vegas proper? It’s just one giant holodeck. Choose your program: Perhaps fin-de-siècle Paris? Maybe Venice during the Renaissance? How about ancient Egypt? I’m halfway between delirium and bliss.

The prevailing image of the Star Trek fan—aided by decades of SNL sketches, two documentaries, and a pretty good Tim Allen movie (yes, Galaxy Quest )—is of the young, minutia-obsessed, sexually- and otherwise socially-frustrated man. I meet this person, or versions of him, in Las Vegas, but he is one of many different kinds of people. (It’s strange, and ultimately misogynistic, that in a fandom notable for its many women contributors, men are still its public face.) In reality, Star Trek Las Vegas is one of the most heterogeneous spaces I’ve ever been in—period. The range, and relatively equal distribution, of ages, genders, sexualities, body sizes, abilities, ethnicities, geographic-origins, astounds me. It looks like some giant space hand shook up all the people on the planet like snowflakes in a globe and pulled out a random sample.

Over the course of five days, audience members and actors try hard for novelty. Both parties are here to meet each other: this is the point of conventions. But when you’ve been talking Trek for nearly 50 years, when do you run out of things to say? Some handle this better than others: Takei speaks about his recent musical, Allegiance , and what he sees as the pointless brevity of Beyond ’s depiction of Sulu and his husband. Shatner talks about how confusing black holes are and then rolls out a story about a bicycle Leonard Nimoy kept on the TOS set that’s been in circulation for almost as long at the show itself.

I see the same people get in line to ask actors questions. The man who always wears a tie but not a jacket. The boy in a TNG uniform with the big mop of curly blond hair. The Klingon who only ever wants to heckle the speakers about Klingons. At Takei’s panel, a man asks, “Has anyone ever approached you to market foils or swords?” (His character Sulu whips a blade around in the TOS episode, “The Naked Time.”) At a Voyager panel, a man haltingly reads to Jeri Ryan from a prepared statement: “I officially crown you queen of my Star Trek universe.”

At the front of the line, I often see a familiar face. Deborah has always been a Kirk. It was her husband, Barry, a fellow Star Trek fan, who took her last name when they got married. “It was an offer he couldn’t pass up,” explains their 26-year-old son, whom Deb will introduce every time she steps up to a microphone over the course of the weekend. “This is my son,” she says, and pauses after each name for emphasis, “Patrick. James. Tiberius. Kirk.” This is the big reveal, their familial shtick.

At actress Kate Mulgrew’s panel, Deb is the last to ask a question. She introduces her son again. ( “Patrick. James. Tiberius. Kirk.”)

“Your character, and your strength, on Voyager got me through his junior high school and high school years being autistic,” Deb says. “He’s a genius, he’s a savant. They treated him like dirt. I would come home and watch you and said, ‘She has the strength to get them home,”— Voyager ’s crew have been stranded a lifetime away from Earth—“‘I have the strength to get him through life.’”

“You may have been watching me,” Mulgrew says. “That boy was watching you.” That’s when I start to cry.

A Ford Aerostar designed by Robert Strever to look like a shuttlecraft.

Vic Mignogna is in his early fifties but looks, on purpose, younger than that. He likely has the best tan of the entire convention. While we talk, three people ask for his autograph. A prolific voice over actor (he dubbed Edward Elric’s character in the popular anime series Fullmetal Alchemist ), he’s most famous here for his live action work: the fan-created web series Star Trek Continues . The show recasts, and painstakingly recreates, TOS : its premise, and point, is to complete the Enterprise ’s unfinished five-year mission. Vic is the show’s driving force and its Kirk, and he estimates he’s spent about $150,000 of his own money on Continues . “Every dollar you will ever make will go to one of two things: paying bills or for joy,” Vic says. This is his joy.

Before we speak, I watch Creation’s Adam Malin shut down a question a fan had posed about Axanar , a controversial, unfinished fan film that’s been halted by litigation from CBS and Paramount, Star Trek’s owners. The brainchild of executive producer Alec Peters, Axanar raised over $1.2 million between July 2014 and August 2015 with the promise of being “the first fully professional, independent Star Trek film.” In December 2015, a whole year and a half after the project, and it’s anticipatory short “Prelude to Axanar,” launched to great excitement and acclaim, CBS and Paramount filed suit for copyright violations—a major shift in their longstanding policy towards fan productions.

Most of the criticisms voiced about Axanar have to do with money—they claim that Alec tried to make a profit using intellectual property he didn’t own. The culture surrounding fan-made products, whether they are film or fiction or phasers, strictly condemns capitalizing off of fan works. It’s likely for this reason that the Star Trek Continues team sought 501c3 nonprofit status—a process that took them a year and a half to accomplish. But Paramount and CBS, the owners of Star Trek, sued Axanar on grounds for which all fan films qualify: copyright infringement. “The people who own it know that there would be no Star Trek without the fans who saved the show,” Vic says. He says this like it will protect him.

Axanar ’s trajectory through the fan film world, which had previously existed in a state of benign neglect, profoundly changed the landscape for both its creator and the community at large. In an effort towards rapprochement with the fan community, Paramount and CBS issued guidelines on June 23 : ten rules fans can follow to avoid litigation. But many of the major fan productions, Continues among them, violate the new guidelines in fundamental ways. To reshape Continues to fit this new bill is to gut it.

Sitting in Quark’s Bar, Vic has nothing but contempt for Alec and Axanar . “It was an ego fest,” he says. “He ruined it for the rest of us.”

Picture a snake eating its own tail. For Vic to get new Star Trek, the property has to make money. For Star Trek to make money, Vic (and the fan community writ large) has to remain engaged. And that engagement often takes the form of fans manufacturing and freely exchanging products the business might’ve otherwise tried to sell. Alongside fan fiction, there are licensed novels. For every illicit phaser replica, there are thousands of licensed toy versions. For each Chris Pine-as-Kirk studio movie, there are two Vic-as-Kirk fan-made episodes. But this uneasy and self-cannibalizing state of affairs is actually a pretty static one: Star Trek has, after all, made it to decade number five. Exacting handmade replicas and child-safe toys can and do coexist. This year Roddenberry.com, a company owned by the Roddenberry family, has even teamed up with a group of fans, the online prop-making community Fleet Workshop, to design and manufacture replicas of the Vulcan "IDIC" symbol. (The acronym stands for “Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations,” the most important tenant in Vulcan philosophy and, subsequently, Star Trek fandom.) For Fleet Workshop member Ryan Norbauer, it represents something "truly collaborative—a fan-produced item that is officially licensed,” and a third path for fans and creators.

In some respects, 50 years out, it’s never been better to be a Star Trek fan. There’s a new, and entirely decent, movie in theaters with more slated to come. An admired TV auteur with unimpeachable Star Trek credentials, Bryan Fuller, is set to launch a new series, Star Trek: Discovery , in the new year. And yet this year’s convention is strangely, consistently, backward looking. No actors, writers, producers from the new films make appearances. The new series is an even more glaring absence. While many people speculate on its future, no one really knows—there isn’t a person working on the show there to talk about it. Some of this might have to do with licensing deals, some surely stems from there not being a new TV show yet. But the prevailing sense at Star Trek Las Vegas is that the franchise is past, not future.

“Can’t we all just get along?” It’s a rhetorical question, but Mark Altman is considering the matter of old versus new Trek. The franchise, he says, “is like a chameleon, it can keep reinventing itself.” And Star Trek already has—many times over—just to make it this far: from the candy-colored adventure of TOS to the solemn, Kubrick-ian Motion Picture to the lighthearted workplace comedy of The Voyage Home to the taupe, utopian diplomacy of TNG to the ambitious and often cynical arcs of Deep Space Nine to the scrappy missteps of ENT to the lens-flarey blockbusters of today. “The new movies are what they are. I don’t hate them,” Mark says. “As [ ENT writer] Chris Black says, ‘I hate the Nazis, I don’t hate the Enterprise theme song.’”

Star Trek fans have remade the world in their image. In the 1970s, John tells me, “we would never have told the people at the job we were working for that we were fans.” Though it took up much of their time and energy, he explains, “We never thought of ourselves as having a fannish lifestyle.” The template just didn’t exist yet—they were making it.

Today, Jarrah Hodge, cohost of the podcast Women at Warp , fills her Canadian Labor Congress office with Star Trek action figures. Dana Zircher, a trans software design engineer at Microsoft, marches with the company’s LGBT employee group in Boston’s Pride Parade in Data’s uniform and pale gold face paint. (She chose her name in part because of its similarly to the TNG character’s.) Brian Gardner, a member of the U.S.S. Las Vegas fan club (and a striking Patrick Stewart look-alike), thinks little of picking up groceries in his uniform after official events. Access Hollywood ’s Scott Mantz rips open his button-down shirt during a 2009 interview with Star Trek ’s Chris Pine and Zachary Quinto to reveal a vintage TOS t-shirt. “I’m that guy,” he announces, triumphant. In a culture shaped by 50 years of Star Trek, we’re all that guy. Or we can be, if we want to. That’s the whole point.

- More to Explore

- Series & Movies

Published Apr 26, 2011

Star Trek and the Culture of Fandom

StarTrek.com welcomes the newest addition to our blogging family, Daryl G. Frazetti, Professor of Anthropology and Sociology at CSU Channel Islands. Here, in the first piece, Professor Frazetti examines the topic of Star Trek and the Culture of Fandom.

Who are Star Trek fans? They are not simply teenage boys who live in their mother’s basements as the stereotype goes. They are not the glimpses of costumed characters the media airs when the Trekkies come to town. They are a diverse and vibrant cultural entity. Star Trek fans are educated, with as many, if not more, female fans as male fans, and come to fandom from a broad spectrum of age and demographic. This phenomenon of fandom stems from the fan attraction to the meanings in the mythos of Star Trek . Myths are value-laden discourse that focus on the examination or explanation of the human condition, therefore Star Trek is indeed a powerful myth that has acted as the basis for the formation of the fandom culture. S tar Trek represents modern/progressive myth, and as such it legitimizes fan participation in numerous activities. Myth explains the meaning which fans have assigned to both Star Trek and the archetype characters it has created. Star Trek acts as a secular myth for contemporary times by providing cultural symbols and meanings that serve as a model for the formation of a distinct culture.

Through the data of the fandom survey that was conducted in 2010, it can be said that the Trek myth is quite real to members of fandom, and like all myth, it is subject to continued reinterpretation on the individual level at varying points in time by the believers in the myth. There is certainly an incredible amount of individuality throughout the culture of fandom. Despite this, it is still possible to identify core meanings in Star Trek , meanings that bind the individuals together as a valid cultural entity. The utopian future, concept of IDIC (infinite diversity in infinite combinations), and the humanistic study of the humanity are ideals shared across fandom. Star Trek is a futuristic portal, allowing fans to learn from the past, make changes in the present, and strive for a Trek future. Fans have found compatibility between the messages of Trek and personal beliefs, incorporating the myth into their daily lives with ease. All of this and more became clear, as a better understanding of the fans surfaced through their participation in this survey.

This survey was not intended to be the final word on fandom, as it is still quite the task to gather data and find a way to best represent the vast diversity that is Star Trek fandom. This survey was intended to reach out as far and wide as it could through the internet and act as the best guide to date on fandom. The following represents a brief synopsis of the data, particularly of some of the more focused on areas showing up on a variety of discussion boards.

The original fandom survey began as a small scale project to collect data on fan culture for a chapter on this topic in my forthcoming text, “Anthropology of Star Trek .” In an attempt to explore stereotypes and simultaneously reach out to the population of fans that are not always the ones focused on by the media, what most would call the “armchair” or “average” fan, I had constructed a fairly comprehensive survey, oftentimes asking the same question in different ways, and reaching out to both the online and convention communities. The anonymous survey was conducted online and 5, 041 individuals participated. Fandom reaction to results has been interesting to say the least, with buzz about the ratio of female to male fans, how fans rate their participation, and the perceptions of costuming. For those not wishing to read an entire paper, this brief has been developed for the purposes of taking a bit more of a look at those target areas. As is the case with any culture, Star Trek fans are quite the diverse group, and the data from this survey certainly supports that in a very large way.

One of the most interesting aspects of this survey was seeing how so many fans paused to give thought to their definitions or perceptions of Star Trek , fandom, and themselves. Many times emails would come in asking if someone should take the survey as they watched the shows but did not attend conventions, yet may have collected merchandise or had been influenced in some way. They were asking because they were not certain if they were part of fandom culture, or if a friend or family member were part of fandom culture. In attempting to gain as detailed a perspective of this culture, it was hoped that the survey would reach out to folks exactly like this, and many responses indicated that indeed they were what would be referred to as “arm-chair” fans. It was also interesting to see how many took this survey after having made such inquiries with me, and perhaps even more interesting to see how some of the responses evolved. Fans may not have begun with a high rating of themselves in comparison to how they felt other fans were involved in fandom (per the media stereotypes), yet had quite a bit to say regarding how they may have been impacted or influenced in some way in their lives (educationally, professionally, personally, or with respect to community involvement) through Star Trek . This supports the notion of a much deeper, much more diverse, fandom than what is typically portrayed by the media, and even in many instances by other fan groups or fandom outlets.

When fans were asked to rate themselves on a scale of 1-5 (1 being the least active, 5 being the most active) and were offered the opportunity to explain their rating, this is what resulted:

- 13% identified themselves as professional fans (fans who are now professional and working in Trek) and considered to be highly involved.

- Overwhelmingly, 82% considered themselves to be average to below-average in terms of involvement.

- 18% went all out to go into elaborate detail about how extremely involved they were as fans.

This group reported such activities as attending more than 10 conventions a year, belonging to 2 or more groups/clubs, having careers influenced by Star Trek , taking on Trek-related personas and being involved in costuming, and being either raised on Star Trek values or currently teaching others the values of Trek, including raising their own children on Trek.

- Others reported such activities as being involved in convention organization (11%), and following Star Trek in some way online (73%). One final note, 3% responding mentioned being hardcore prop collectors and another 17% commented on how their involvement with Trek has declined as they have aged.

The end result is a portrait that looks as though many who participated in this survey were either “arm-chair” fans, or did not feel what they did to be a part of Trek actually counted since it did not compare in their eyes to what they see the perhaps more stereotypical fans doing. Many of the 82% stated that they did not regularly attend conventions, some never have attended a convention, some purchased some merchandise, and many did not. Some had Trek related clothing (t-shirts and such) and many did not. A good majority of fans perceived of themselves as having a very low level of involvement. Most followed the shows in syndication or on DVD, with some reporting they follow the comics, magazines, books, or online discussions. Fans responding in this group felt that someone else was far more active as a fan than they were. This meant that if a fan wore costumes, attended conventions more frequently, collected merchandise, or followed actors, then they were seen by their own cultural peers as more active.

Results such as these were not expected, but were also not surprising either. Most fans participating fell between the ages of 41-50, single, and held some higher educational degree, indicating that many were indeed “arm-chair” fans who were now focused on other areas of their lives such as careers perhaps. Some also indicated working more than one job or a return to school for further training/education. Many also had reported that if they had the income, and/or time, they would find themselves more involved with collecting or traveling. Going online, and therefore participating in such a survey, is how these fans remain connected with Star Trek . Such results indicated a greater diversity in fandom, a greater number of fans simply do not fit the media molds of what a fan is. All Trek fans are simply not all that much alike. Go to a convention and you will find even there that fans pocket off into clusters with like minded folks just as groups do in any mainstream culture, and just as those do who do not participate in a stereotypical way. All cultures need diversity in order to survive, grow, and thrive. Star Trek fandom is no different, and these results certainly support a greater deal of diversity than fandom has been given credit for.

Arising from Japanese origins, specifically anime, “cosplay” in the United States has now grown via science fiction and historical fantasy. Fans partake for a variety of reasons, many to emulate characters who have been most influential in their lives, or to take on personas based on a group or character they feel they most identify with ( Klingons , Vulcans , Spock , Kira ). It is not unusual to see many attending conventions, as such venues offer fans this opportunity to enter their personas and more fully participate in the myth, in the narrative that has become so personally meaningful to them. However, it is not a requirement to take on a persona or wear a costume of some sort in order to participate. Given how many do though, allows the media to focus in on this aspect, creating the stereotypes that still hold up today. Many fans did in fact feel that those participating in costuming or any type of role play at a convention often give off the impression that they are not fully in touch with reality, do not always see the actors as real people, and are not considered to be the majority of fans throughout the vastness of the fandom culture.

These same individuals have expressed concerns about the constant portrayal of fandom by the media as being all about folks dressing up and gathering by the thousands to collect merchandise and autographs. Not the case. Fans participate obviously in many ways, and most simply choose these other ways to take part in the myth. What was “normal” or what was “deviant” or “extreme” was asked of those taking this survey. Fans themselves were asked to describe and define these terms as they pertained to members of their own culture. Yes, the results did shatter the stereotypes, but were not unexpected, particularly given the amount of outreach for participants.

Some data of interest: When asked to define “normal” (comments were sorted and categorized, then sorted by number of participants per question):

- 67% stated that watching the shows, reading novels, or wearing a t-shirt and some merchandise collecting was normal.

- 59% stated in some way that wearing costumes and/or attending conventions was normal.

- 81% noted that community involvement or using their Trek interest in some positive way in life was normal.

- 79% stated that anything not obsessive in some way, living in the real world still, and being an all around good person, utilizing the values and ideals of Star Trek in some way constituted normal.

One fan simply stated that to them, normal was going on a Trek cruise and meeting other professionals that just enjoy Trek and have a normal mainstream life. To most this was the case as the data suggested, most fans are just leading average lives and enjoy watching the shows and occasionally enjoy connecting with other like-minded Trek fans.

So, what did fans say about what was “deviant” or “extreme”? (comments were sorted and categorized, then sorted by number of participants per question):

- 89% of respondents stated deviance could be defined as those who could not differentiate between reality and fantasy.

- 67% of respondents stated deviance could be defined as those who made Star Trek their entire world.

- 47% of respondents stated that deviance could be defined as those who dressed up.

- 39% of respondents stated that deviance could be defined as those who take on persona names or refer to themselves as any rank.

- 13% of respondents stated that fans producing fan films were considered to be deviant.

In part, responses demonstrated that many fans viewed those taking on personas, chasing actors, or costuming to the point of continuing such behaviors even outside of the convention arena were considered deviant or extreme. Meaning they did not appear to have social networks outside of Trek or have other interests outside of Trek. To those responding here, a good majority also felt that these sorts of actions, even dressing up, did not reflect what was felt to be the average Trek fan. Yes, this does debunk the stereotypes, but this is not a culture that can be pigeon-holed. It is a diverse and dynamic entity, well supported through the data in this survey. One quarter of those participating were from outside the United States, which perhaps also lent support to the shaping of the data for these questions. Star Trek fandom is a culture that is not only a brief moment in time, forming only when a convention is held, it is a dynamic and evolving entity with much diversity, just as meaningful as any other cultural entity one could study. This survey was circulated to dozens of sites via the internet, as well as several dozen conventions during 2010, and is a good reflection of sincere diversity that exists, supporting that there simply is no basis for the ever lingering media stereotypes.

Now onto women in fandom! Yes indeed, 57% that took this survey reported being female! That means 43% were males. That was not expected, but it was close. This data does support the history of Trek fandom, the current trends in fandom, and the rumors that have buzzed about since the 2009 film came out about how it brought in not only new fans, but more female fans. Women have held a strong presence in science fiction both as professionals and as fans for decades. Fanfic has been dominated by the female fan, and over the past several years, participation by women in fandom has been increasing. The data also demonstrated a correlation between age and sex, further supporting the idea that more women are entering Trek fandom due to the recent 2009 film. Of those females responding, 13 % were between 21-30, overall that age group accounted for 21% of respondents, the second highest age group following the 41-50 year olds, of which accounted for 34% of those responding to the survey in general, 19% were female. From Bjo Trimble and the original letter writing campaign to save the original series to Shirley Majewski (known fondly as the godmother of fandom), women have been a real driving force in Trek fandom. Various reports from the 1960’s and 1970’s rated female involvement in ranges between 17 and 80% at times, most especially in examining fanfic and clubs which were both female dominated areas in fandom and continue to be today.

Overall, the survey actually supports data from several others that have been conducted on smaller scales throughout the past two decades. Certainly it is not the number of participants, but also how they are selected that support a survey such as this. It was hoped that in designing a self- selecting survey with questions that asked fans to rate themselves, describe themselves, define terms, and define their activities, by asking similar questions in various ways, and by attempting to attract a wide range of participants, that a more balanced view of the Star Trek fandom culture would emerge. The data provided by this survey and the ways in which it supports past surveys of fandom suggests that this is a good indicator of much of the true nature of the culture and the overwhelming reports of the binding ideologies of IDIC (infinite diversity in infinite combinations) and Humanism. Yes, it would be more practical to select participants, a sample of the fandom, as self – selecting surveys can be biased. Given how supportive this data has been of other surveys is encouraging, and using this method has led to a more focused project that will be a full ethnographic study now, where a small and focused sample will be selected, making for a more scientific survey of fandom. In remaining unbiased, questions will again be designed in such a way as to not elicit specific responses. Additional methodologies will include observation/participant observation, and interviewing.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Click HERE for the full survey results paper.

Daryl G. Frazetti : www.academia.edu/darylfrazetti

Bio: Professor of Anthropology and Sociology at CSU Channel Islands, Camarillo, CA. Research areas include science fiction in higher education, the subculture of fandom, fan films, science fiction as mythos, using science fiction to explore fieldwork and human existence, and exploring various science fiction literature and pop media as both cultural mirrors and cultural teachers. Primary area of interest: Star Trek . Forthcoming text, Anthropology of Star Trek , is based on the course of the same name, created by Professor Frazetti. Professor Frazetti also speaks at various conventions and schools on the cultural and curricular significance of science fiction, fantasy, and comics.

Get Updates By Email

- Movies & TV

- Big on the Internet

- About Us & Contact

A Brief History of Fandom, Or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Being a Fan

In the beginning, I was not a fan. I liked stuff – Firefly , Star Trek , Lord of the Rings – but the tween who freaked over Bon Jovi and baseball grew up and moved out. I knew about fans; I married a classic Trekkie, who memorizes music cues and can name an episode by its first five seconds, and who first went to Comic-Con in 1972. But I thought, as so many do, that fandom was the domain of man-children with a less than firm grasp on reality.

Then I met the Doctor.

Suddenly, in my late thirties, I was binge-watching a television show. I was pining over fictional characters – and I was writing my own stories for them when the official versions ran out. I was making costumes and going to conventions. I was lit up, inspired, excited as I hadn’t been by anything since childhood.

I wanted to know what had happened to me. So I did what any true nerd would do: I began to read.

By very good fortune, I quickly stumbled across Henry Jenkins’ groundbreaking Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture (Routledge, 1992, reprinted 2009). The book is an ethnography of fandom by a media studies scholar who is also a fan, and it was among the first to see fans as complex, engaged humans rather than mindless obsessives. It showed me a glimpse of a startlingly creative world populated by people like me: women (mostly) who love things (like TV shows) for reasons they can’t always explain. More recently I discovered Anne Jamison’s Fic: Why Fanfiction is Taking Over the World (Smart Pop, 2013). This collection of essays on fic and its writers introduced fan motivations and perspectives I had never imagined. Reading these books I felt understood, but I also began to understand.

You Are Not Alone

It’s obvious now, but at the time it was a revelation. Grown-up adults get passionate about things that aren’t real. C. S. Lewis, author of the well-loved Narnia series, is famously quoted as saying, “When I became a man I put away childish things.” However, not as many people know the rest of the quote: “…including the fear of childishness and the desire to be very grown up.” Simon Pegg, John Green, and David Tennant have all spoken in public about being unashamed to love the things they love. Neil Gaiman has expounded at length on the value of fiction and fantasy. I find myself in very good company.

This Has All Happened Before

The Star Trek fandom is probably the first famous fandom. The letter campaigns that brought the original series back for a third season – and the cast back for a feature film – put TV fans on the map; when non-fans talk about fans, they’re often thinking of Trekkies. But Star Trek fans were not the first, as any Sherlock Holmes fan knows. Anne Jamison identifies the medieval romance The Knight of the Cart , written around 1171, as Arthur/Lancelot/Guinevere fic (Jamison, p. 27). Other fans have pointed out that artists as admired as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo produced fan art: The Last Supper and The Creation of Adam were, after all, based on someone else’s story.

More surprising, I learned from Jenkins (1992, p. 225):

Using home videotape recorders and inexpensive copy-cords, fan artists appropriate “found footage” from broadcast television and re-edit it to express their particular slant on the program, linking series images to music similarly appropriated from commercial culture.

YouTubers did not invent the fan vid. VCR-era fans made videos of their own, some with as many as 189 edits (Jenkins p. 229), with clunky analog tapes and editing machinery subject to slips and drifting: the technological equivalent of stone knives and bearskins.

Can’t Stop the Creativity

Something about being a fan drives people to make things. When they love something, they want to make more of it, to make different versions of it, to make it better. And they can’t be stopped. Sometimes the barriers are physical, like the technology those VCR vidders had to work with, or the continents and time zones separating members of the Doctor Who Fan Orchestra . But other barriers are falling as well. Author, lawyer, and fanboy Leslie S. Klinger recently sued to free Sherlock , demonstrating in court that the character belongs in the public domain. The Organization for Transformative Works protects access to fan works and fan creativity in the face of a legal culture that is often misunderstood.

It’s Not Just Us

I am finding fandom everywhere. Fantasy sports teams. Real-person fic about boy bands. Religious icons. The ‘reveurs’ of Erin Morgenstern’s The Night Circus (Anchor Books, 2011), for whom the circus is – like the media convention circuit – an opportunity to immerse oneself in a created world and spend time with like minds. People are fans of all kinds of things, and for all kinds of reasons. Some viewers reject the BBC’s Sherlock for its throwback masculinity; others use the characters to work out their own feelings of isolation and social inadequacy. Some decry Twilight as vapid juvenile romance not worth the paper it’s printed on, while others see an intriguing set of characters in search of a (frequently very adult) story – which they often then write themselves. Young men like Peter Berg (Jamison, p. 337) love My Little Pony – not for the creepy reasons that some of us (guilty) first assume, but for the show’s fantastic worldbuilding and opportunity for adventure.

It doesn’t matter what the merits of the property are if it has the power to inspire. It’s not all one thing, like science fiction or cult television; it’s a million things, all speaking to people in a million different ways.

The Continuing Mission

I’ve only scratched the surface. There are miles to go inside this world. Like the Doctor, I discover something new at every turning, and there’s always more to see.

Bring on the adventure.

Elisabeth Flaum began writing because of Doctor Who and hasn’t yet been able to stop. She lives with a man and two dogs in Portland, Oregon, where she works in accounting, races dragonboats, and writes poetry about the weather. Interested readers may follow her ramblings here .

Fandom Explained: Star Trek

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the birth of the Star Trek franchise. Not even creator Gene Roddenberry himself could have predicted its longevity, die-hard fan base, or the impact it would have — on both the sci-fi genre and on the world in general. From helping a long list of scientists and astronauts choose their career paths to influencing the development of real-world technologies, Star Trek has firmly cemented itself as a permanent fixture in the hearts and minds of millions of fans worldwide. As a testament to this, countless references , nods , and tributes to Star Trek can be found across virtually all entertainment and pop-culture mediums dating all the way back to the airing of the original series.

For such an iconic, billion-dollar franchise now spanning half a century, it’s hard to imagine that the original Star Trek TV series was initially viewed as a failure. From a ratings standpoint, the 1960s series was not a very successful venture, ending up cancelled after only two seasons. Only an outpouring of fan support by way of a letter-writing campaign (thank you, Bjo Trimble !) kept the show alive for another season.

What endeared this early fan base to the series? And why have the legion of Star Trek’s “Trekkie” fans grown exponentially since then? Let’s take a look at some of the things that make Star Trek so special, and what keeps fans coming back for more after all this time.

Setting the Standard for Sci-fi Television

Before the world was introduced to Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock in 1966, sci-fi television was viewed as a goofy genre that didn’t get much respect outside a narrow demographic of enthusiasts. Shows were generally low budget affairs, often with questionable writing and maybe a neat looking — if poorly executed — robot or space ship.

All that changed when Star Trek began its now-iconic run on network television. Although obviously crude by today’s standards, the set pieces, and visual effects were beyond comparison at the time. More importantly, the characters had backstories, and real thought had been put into the technology powering the fiction and how it might actually work in theory.

All of these elements provided the foundation for a spaceborne sci-fi show that viewers could actually take seriously and raised the bar for future space-themed television programming. Each new series that has been produced since the original has continued to push the special effects boundaries of its time, eventually moving from physical props to the computer generated graphics that the series itself had once predicted.

Cultural and Social Issues

Fans have always had a great love for Star Trek’s willingness to address controversial subjects relevant to current events. This was especially of the original series, which aired during the seismic social and cultural changes of the late 1960s. From the start, Gene Roddenberry set out to create a platform that would embrace his own idealistic vision of Earth’s future, in which the worst aspects of humanity — war, greed, poverty, and intolerance — had been widely eliminated.

His insistence on creating a racially and culturally diverse main cast was the most obvious first step in this direction, but the show also addressed major social issues of the day, including the Civil Rights movement and the U.S. involvement in Vietnam. These concepts became the blueprint for all future Star Trek series, with the subject matter evolving to fit social issues particularly relevant to the time in which they were produced.

Perhaps the most frequently cited example Star Trek’s socially progressive approach is an episode from the original series called “ Let That Be Your Last Battlefield .” In it, two factions of a species of (literally) half white, half black humanoids are determined to destroy each other. The catch is, the only discernible difference between the two sides is that their physical coloration is reversed. Black on the left and white on the right for one, the opposite for the other.

To the “enlightened” crew of the Enterprise , this level of senseless racial hatred is all but impossible to grasp. To the aliens, however, their seemingly minor and superficial differences are worth killing over — even after the entire population of their planet has mutually annihilated itself in a civil war.

Another prime example of this bold approach can be seen in how The Next Generation episode “ The Outcast ” deals with gender identity. In this story, Commander Riker becomes enamored with Soren , a member of an androgynous alien race called the J’naii . Riker is intrigued by this ambiguity, but he later comes to learn that some J’naii, including Soren, do in fact secretly identify as one gender or the other. Soren explains that they are forced to live a lie since displaying a specific gender is considered a criminal perversion. While this episode first aired in 1992, similar issues are still faced by members of the LGBT community nearly a quarter century later.

Fan Community

Part of what makes being a “ Trekkie ” such an enjoyable and rewarding experience is the vast fan base of like-minded people out there worldwide. There are numerous Star Trek fan groups on major social media platforms such as Facebook and Reddit, as well as a multitude of forums on a wide range of Trek-related topics. Conventions, cosplay, podcasts, and fan fiction are only a handful of the many activities available to fans who wish to share their love of Star Trek with others who can relate to their excitement and dedication.

And like the show, the Star Trek community is non-judgemental. Whether you’re a lifelong fan or a newcomer, and no matter if you embrace all things Trek or prefer only a specific corner of the franchise, you can celebrate your love Star Trek in your own way.

The breadth of the Star Trek universe at this point makes that easy: With five live-action series (and a sixth in production!), an animated series , thirteen films , numerous novels and video games , as well as some notable fan productions such as Star Trek: Phase II and Star Trek Continues , there really is something for everyone.

Want to know more about Star Trek ? Memory Alpha has answers to just about all Trek-related questions you could possibly have — and many more you never thought to ask! You can also join our Star Trek Discussions hosted by Trek Initiative , and don’t forget to check us out on Facebook and Twitter .

How Star Trek: The Original Series Created Modern Fandom

Nearly 60 years after Star Trek debuted, The Original Series fan community provided the blueprint for modern fandom culture in entertainment today.

In the entertainment industry today, franchises are the thing. Why make a TV show or movie when an entire universe of storytelling can be explored? Audiences, for the most part, enjoy this forming communities of fans from everything from Star Wars to SyFy's 12 Monkeys . Yet, modern fandom was created nearly 60 years ago, because of Star Trek: The Original Series . The space-fantasy with Vulcans, warp drive and the beautiful USS Enterprise captured the imaginations of kids and adults alike.

The brilliant actors and writers who bring these stories to life were forced to strike because studios refuse to pay them their fair share. So, the wait for Season 3 of Strange New Worlds , and the cliffhanger resolution, will take some time. Yet, it's remarkable that anyone would even care about the third season of the 12th Star Trek series nearly six decades after the show first debuted is remarkable. However, the influence goes beyond just their 12 series and 13 films in the franchise. Any fandom where people gather at conventions, cosplay, write fanfiction or even campaign to "save" a canceled series owes a debt to Star Trek: TOS . Almost 20 years before the internet was even invented, Trekkies (and Trekkers ) created modern fandom and kept Gene Roddenberry's universe alive until Paramount greenlit a movie 10 years after the show ended.

RELATED: How Star Trek's Federation Evolved From Just a United Earth

How Star Trek: The Original Series Went from Cult Hit to Fandom Juggernaut

When Star Trek: TOS debuted on NBC it wasn't a record-breaking hit, but it quickly found a passionate fanbase. By the time the first season ended, fanzines like Spockanalia had already appeared out in the wild. When ratings disappointed in Season 2, fanzines and early Star Trek conventions organized a massive letter-writing campaign to save the show . By Season 3, NBC buried the show in a Friday timeslot, and The Original Series was canceled. Yet, not five years later, Star Trek: The Animated Series debuted , continuing the voyages of the starship Enterprise. Yet, the truly impressive thing happened in the ten years between the TV series ending and Star Trek: The Motion Picture 's debut.

Star Trek: The Original Series quickly went into syndication where it became the highest-rated scripted syndication series. This lasted until the 1980s, according to The Center Seat: 55 Years of Star Trek . Not only that, Star Trek conventions took off. While they weren't the first conventions, science fiction conventions existed since the late 1930s, they were the first ones centered around a single property. William Shatner confessed he was befuddled by the phenomenon in an early 1970s interview with Geraldo Rivera , complete with an audience in full Star Trek cosplay.

Every year Star Trek: TOS was off-the-air, the fan interest only grew larger and stronger. In 1972, the Star Trek Lives! gathering featured Gene Roddenberry and others, but no actors. Still, 3000 people showed up when the venue expected no more than 500, according to GQ . Once the films and Star Trek: The Next Generation debuted, the franchise continued, in large part because fans like Ronald D. Moore and Enterprise 's final showrunner Manny Coto started making it. The power of fans' love for Star Trek didn't just keep the franchise going, it also gave a blueprint to other fandoms.

RELATED: Why Star Trek Ships' Maintenance Corridors Are Called Jefferies Tubes

From TOS to Strange New Worlds, Star Trek Is Still Influencing the Culture

Even TNG pre-dated mass adoption of the internet, but Star Trek: TOS predicted it, somewhat. Kirk's desk monitor computer looks like the computers of the 1980s, even though at the time real computers filled warehouse-sized spaces. The series foresaw instant video communication and the Starfleet "databanks" work very much like the internet today. By the mid-1990s when the internet was becoming more mainstream, it was Trekkies - -along with Star Wars and The X-Files fans - -who proved it was the new central hub for fandom-at-large.

One way the internet fuels fandom to this day is via fanfiction. People can write stories about their favorite characters, posting them online for other fans to find. Yet, the first time a community wrote fanfiction primarily for each other was in the Star Trek fanzines of the 1960s and 1970s. In fact, the popular category of "slash fiction," pairing two characters of the same gender romantically, got its name because of the early Spirk shippers . To denote a story about Kirk and Spock in love, they marked them with each's first initials separated by a slash: K/S.

Star Trek: The Original Series was the first time any storytellers even tried to achieve representation of any kind . It's no wonder that fans not explicitly represented still responded so strongly to the series. These passionate early fans aren't just responsible for keeping the Enterprise aloft these past 57 years. They're also responsible for creating the example modern fans use to build their communities. From massive franchises like the Marvel Cinematic Universe to smaller fandoms like those for Warrior Nun , they all owe a debt to the unlikely sci-fi series whose fans never let it disappear from the cultural diaspora.

Star Trek Timeline

A holistic view of the chronological timeline of events in the Star Trek universe(s).

This is a work in progress. Content is being added and refined. More features coming as well. (filtering, sorting, etc.) Content last updated on

Have a suggestion, addition, or correction? Send an email!

By Significance

- The Original Series

- The Animated Series

- The Next Generation

- Deep Space Nine

- Short Treks

- Lower Decks

- Strange New Worlds

This is a fan-created site dedicated to providing a holistic view of the chronological timeline of events in the Star Trek universe(s). Most material is sourced from the Memory Alpha fandom wiki site .

TrekTimeline.com is not endorsed, sponsored, or affiliated with CBS Studios Inc. or the "Star Trek" franchise. The Star Trek trademarks, logos, and related names are owned by CBS Studios Inc., and are used under "fair use" guidelines. The content of this site is released under the Creative Commons "Attribution-NonCommercial" license version 4.0.

Event Summary

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

8 Ways the Original ‘Star Trek’ Made History

By: Sarah Pruitt

Updated: November 2, 2021 | Original: September 8, 2016

When "Star Trek" premiered on NBC in the fall of 1966, it promised "To boldly go where no man has gone before." More than half a century later, it has done just that. The original "Star Trek"—which lasted for only three seasons—birthed some 20 spinoff series and films; a universe of games, toys, comics and conventions; and influenced decades of science-fiction. Here are eight ways the show broke new ground.

The Center Seat: 55 Years of Star Trek premieres Friday, November 5 at 10/9c on The HISTORY ® Channel

1. A veteran of World War II, Gene Roddenberry created a show about fighting another world war—this time in space.

After piloting a B-17 bomber in the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II , Roddenberry served in the Los Angeles Police Department before he began writing for TV. He created the short-lived series “The Lieutenant” before Desilu Studios (founded by Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz) picked up “Star Trek” in 1966. In an era before man set foot on the moon, the show introduced us to a 23rd-century world where interplanetary travel was an established fact: Captain Kirk and the crew of the starship Enterprise (named for the real-life ship that turned the tide toward the Allies in the Battle of Midway) roamed the galaxy, clashing with alien enemies like the Klingons, Excalbians and Romulans.

2. The show’s multicultural, multiracial cast put it well ahead of its time.

In addition to the half-Vulcan Spock, the crew of the Enterprise in “Star Trek”’s debut season included Lt. Nyota Uhura (played by the African American actress Nichelle Nichols) and Lt. Hikaru Sulu (played by the Japanese American actor George Takei). In an era of mounting racial tensions, “Star Trek” presented a positive image of people of different races, genders and cultures (not to mention aliens and humans!) working together cooperatively—a somewhat utopian vision, perhaps, but a heartening one. Nichols later said that she was reportedly thinking of leaving the show after the first season, but was convinced to stay on by none other than Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. , whom she met at a NAACP fundraiser. The civil rights leader, who admitted to being a devoted fan of the show, told Nichols that she was breaking new ground in the role of Uhura, and showing African Americans what was possible for them.

3. The original 'Star Trek' referred repeatedly to the ongoing, escalating conflict in Vietnam.

Though marketed as a classic adventure drama (Roddenberry based the character of Captain Kirk on Horatio Hornblower from C.S. Forester’s classic naval adventure series), “Star Trek” didn’t shy away from tackling moral and social issues such as war, racism and discrimination. The first season episode “Taste for Armageddon” was one of TV’s first allegories for the Vietnam War , an issue the show would return to most famously in the second season’s “A Private Little War.” In that episode, the Klingons are providing weapons to a primitive planet, and Capt. Kirk decides to do the same in order to preserve the “balance of power” on both sides. One of the most controversial plot lines of that season, the story was clearly analogous to the escalating nature of American involvement in Vietnam.

4. But it offered a positive vision for the future in the midst of Cold War tensions.

In the show’s second season, a new navigator named Pavel Andreievich Chekov showed up on the bridge of the starship Enterprise. As Roddenberry recounted in The Fifty-Year Mission , a two-volume oral history of “Star Trek” published in 2016, the character was added after the Russian newspaper Pravda pointed out that the show ignored the Soviet Union ’s pioneering contributions to space travel. But Walter Koenig, the actor who played Chekov, said the Pravda explanation was made up for publicity: The show’s producers wanted a character to appeal to a younger demographic, and just decided to make him Russian. Though a long-running theory held that the Klingons and the Federation represented the Soviet Union and the United States, two ideologically opposed superpowers, another interpretation argues that “Star Trek” functions as a critique of Cold War -era politics, by offering an optimistic vision of the future at a very uncertain moment in history.

5. It was the beneficiary of one of the most successful fan-organized letter-writing campaigns in TV history.

By late 1967, the original “Star Trek” series was struggling, and rumors flew that NBC was planning to cancel the series after only two seasons. Spurred into action, more than 100,000 fans—known as “Trekkers” or “Trekkies”—wrote letters in support of the show. In the largest of numerous protests on college campuses, 200 Caltech students marched to NBC’s Burbank, California studio wielding signs with slogans like “Draft Spock” and “Vulcan Power.” NBC eventually acknowledged the success of the fans’ campaign, announcing that the show would return for another season.

6. The show featured one of the first interracial kisses on TV.

After being “saved” by the fans, the third season of the original “Star Trek” largely bombed, but one particular moment stands out: In the episode “Plato’s Stepchildren,” Capt. Kirk kisses his communications officer, Lt. Uhura, in what is thought to be the first scripted interracial kiss on American television. Though NBC executives worried how the kiss would play on television in 1968 (especially in the South), they eventually decided to leave it in the episode, earning the show enduring fame for the barrier-breaking moment. (Though Kirk and Uhura’s liplock is often cited as the first interracial kiss on TV, a kiss between actors on the British soap opera “Emergency Ward 10” predated “Plato’s Stepchildren” by several years.)

7. It enjoyed record-breaking success in syndication post-cancellation.

Despite its cancellation after only three seasons (and 79 episodes), “Star Trek” gained new life through syndication, as the devotion of its growing fan base increased from the late 1960s and throughout the ‘70s. By 1986, nearly two decades after it entered syndication, A.C. Nielsen Co. listed “Star Trek: The Original Series” as the No. 1 syndicated show. That same year, Roddenberry launched a second TV series, “Star Trek: The Next Generation,” which was immediately syndicated and became a ratings hit. Meanwhile, “Star Trek: The Motion Picture” had grossed more than $80 million in 1979, leading to several more movies in the ‘80s and ‘90s, followed by a 21st-century “reboot” of the series starting in 2009. Trekkie enthusiasm fueled the success of comic books, cartoons, novels, action figures and other merchandise based on the series, as well as Star Trek-themed conventions attended by thousands at hotels and other venues around the world.

8. Thanks to 'Star Trek' fans, America’s first space shuttle orbiter was christened Enterprise.

In 1976, hundreds of thousands of Trekkies wrote impassioned letters to NASA arguing that the first space shuttle orbiter should be named after the starship Enterprise. Though he never mentioned the letter campaign, President Gerald R. Ford expressed his preference for the name “Enterprise,” with its hallowed Navy history, and the space administration’s officials ended up dropping their original choice, Constitution. Roddenberry and many original “Star Trek” cast members were on hand to greet the shuttle when it rolled out of the manufacturing facilities in Palmdale, California for its dedication ceremony in September 1976. Though Enterprise was used in a number of flight tests, it was never launched into space, and spent much of its life in storage.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- View history

Welcome to the STAR TREK Expanded Universe!

STEU is an encyclopedia and database, like Memory Alpha or Memory Beta , except for Star Trek fanworks instead of canon or licensed works. Fanworks include fan fiction , fan films , fan-created audio dramas , RPGs , and more, both past and present. We also chronicle the history of Star Trek fandom itself. If it's something fan-created, or a part of fanon lore, information about it belongs here. If you are interested in contributing and don't know where to start, see our most wanted pages , or view recent changes where you can see and assist in current efforts. Please enjoy the wiki!

STEU is not a storytelling venue or a host for fan fiction itself. All articles here must be sourced and properly attributed. If you are looking for a place to create your own stories, there are many fan fiction archives and other online hosts where you can post your work, and we look forward to seeing the fruits of your efforts!

Archives • Nominate a quote