The Ages of Exploration

Pedro álvares cabral, age of discovery.

Quick Facts:

He was the first European to discover Brazil, and also established a successful sea route to India and a leader in trade there

Name : Pedro Álvares Cabral [pe-droo] [awl-vuh-ruh sh] [kuh-brawl]

Birth/Death : ca. 1467/68 - 1520

Nationality : Portuguese

Birthplace : Belmonte, Portugal

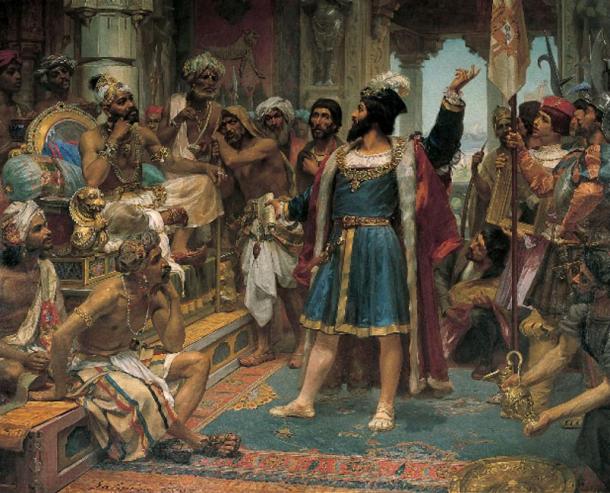

Detail of painting "Vaz de Caminha reads to Commander Cabral, Friar Henrique and Master João the letter that will be sent to King Dom Manuel I". It depicts Pedro Álvares Cabral, leader of the Portuguese expedition that discovered the land that would later be known as Brazil in 1500. {{PD-Art}}

Introduction Pedro Álvares Cabral was a Portuguese explorer who is credited with discovering Brazil in South America. He landed near present-day Bahia off the eastern coast of South America. Several years after Cabral, the Portuguese began colonizing the area. They found great profit by exporting lumber, specifically the brazilwood tree. This was a tropical tree that produces a bright red dye that became very popular. It was also a strong, sturdy wood that was used to make furniture and in ship-building. The name “Brazil” began to be popular in 1503, and was associated with this brazilwood tree. 1

Biography Early Life Pedro Álvares Cabral was born in Belmonte, Portugal in either 1467 or 1468. Although little is known of his early life, we know that he was the second son and came from a noble family. 2 His family was in service to the crown, so young Pedro received his education at the royal court. In 1497, the king of Portugal, King Manuel I, made him part of the king’s council. At this time, the Portuguese were searching for a route to Asia by trying to sail around Africa. Fellow explorer Bartolomeu Dias became the first European to sail around Africa’s southern tip in 1488 but failed to complete the journey to Asia. Nearly ten years later between 1497 and 1498, Portuguese explorer rounded Africa, and made it all the way to Asia, landing in Calicut, India. This accomplishment opened up a faster trade route for the Portuguese empire.

Three years after da Gama’s great journey, the king of Portugal wanted to establish trading ports for Portugal in Asia. He chose Pedro Cabral to head this expedition. It unsure why the king chose Cabral. It is believed that he had little to no sailing experience. 3 But he had connections to the king and was loyal to the crown, so this is possibly why he was chosen. In addition to setting up trading relations in India, Cabral was also tasked with spreading Catholicism. 4 Catholicism is a branch of the Christian religion, and was practiced throughout many European countries. Explorers throughout the ages believed that most native religions were wrong, so they would press Christianity upon the natives – sometimes by force. Not only was Cabral to follow the same route as da Gama, but he was also to sail farther west into the Atlantic ocean to see if any land was out there to be claimed by Portugal. 5 Cabral would indeed find a vast piece of land that would expand the Portuguese empire across the Atlantic.

Voyages Principal Voyage Pedro Cabral set sail from Lisbon, Portugal on March 9, 1500. He had a fleet of 13 vessels and 1200 men, including famed explorer Bartolomeu Dias. Dias was in command of one of the vessels. Cabral and his fleet sailed past the Canary Islands and Cape Verde Islands off the coast of Africa. Shortly after leaving, one of Cabral’s ships was missing, and believed to have sunk. Cabral was to follow the same route as da Gama around Africa to India. However, he accidentally sailed too far south west into the Atlantic Ocean. This accident brought him to the South American coast and to a new land unknown to the Europeans. Cabral realized that the land was not India. He and his fleet made achor, at Porto Seguro, on the coast of the present day state of Bahia. 6 They went ashore and erected a large wooden cross which he used to claim the land in the name of Portugal. He believed he had landed on an island so he. 7 We know this country today as Brazil.

Cabral sent a ship back to Portugal to tell the king of his news. He and the rest of his fleet stayed in Terra de Vera Cruz about 10 days. While here, he interacted with different native people. One account mentions that the natives were curious of the Portuguese’s religion. Several of the Portuguese sailors gave some of the Indians tin crucifixes (crosses) to wear around their necks. 8 Cabral was ready to continue his mission to India. Before leaving, he left two members of his crew – both convicts – to further investigate the land. 9

Subsequent Voyages Cabral and his fleet left South America and headed back southeast towards the Cape of Good Hope in Africa. Along the way, the fleet encountered bad storms. On May 24, 1500, the storm sank four of Cabral’s ships, including the one carrying Bartolomeu Dias. Dias and all men aboard the four ships drowned and died. With his remaining six ships, Cabral continued onward to India. They stopped at several African ports along the way including Sofala, Mozambique, and Kilwa. They did not have much luck trading, and often encountered unfriendly natives. So they soon headed onward. They finally reached Calicut, India (today called Kozhikode) on September 13, 1500. His time in Calicut was filled with challenges. Disputes between the Arab traders and the Portuguese were common. At one point, several Portuguese men were killed by the Arabs. Cabral got even by raiding the city and capturing ten Arab ships, and then executing their crew. 10 Cabral continued traveling to other Indian cities, selling and trading goods and spices into 1501 before heading back home. He reached Lisbon, Portugal on July 1501.

Later Years and Death Pedro Cabral’s return to Portugal had mixed reception. He discovered Brazil, and helped set up trade in India. However, relations in India with the Arab traders did not go well. Plus, Cabral lost more than half his fleet and crew along his journey. Still, the king of Portugal gave him command for another voyage to India. Cabral spent several months preparing, but he was replaced by Vasco da Gama shortly before they were to leave. 11 Cabral left the king’s court and retired. He eventually got married and had six children. He lived a quiet life until his death in 1520.

Legacy Pedro Álvares Cabral’s work in India often get overshadowed by Vasco da Gama’s. Also, explorers Amerigo Vespucci, Vincente Yánez Pinzón, and Diego de Lepe all sailed along the Coast of Brazil and went ashore before Cabral. But these trips were all part of a larger expedition, and none claimed the land for their king and country. So we still give Cabral credit for being the first European to discover Brazil. They still speak Portuguese in Brazil today. And with over 150 million people living in Brazil, it is the largest Portuguese speaking nation in the world. 12 Cabralia Bay in Brazil is named in honor the explorer.

- Boris Fausto, A Concise History of Brazil (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 9.

- James Stuart Olson, ed., Historical Dictionary of European Imperialism (New York: Greenwood Press, 1991), 104.

- Peter O. Koch, To the Ends of the Earth: The Age of the European Explorers (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2003), 149.

- DK, Explorers: Tales of Endurance and Exploration (New York: Tall Tree Ltd., 2010), 96.

- Koch, To the Ends of the Earth , 149.

- Fausto, A Concise History of Brazil, 6.

- Koch, To the Ends of the Earth , 150.

- Britannica Educational Publishing, Biographies of the New World: Leif Eriksson, Henry Hudson, Charles Darwin, and More, ed. Michael Anderson (New York: Britannica Educational Publishing, 2013), 28.

- Olson, Historical Dictionary of European Imperialism , 106-107.

- V. K. Subramanian, The Great Ones Vol. IV (New Delhi: Abhinav Publications, 2005), 105.

Bibliography

Britannica Educational Publishing. Biographies of the New World: Leif Eriksson, Henry Hudson, Charles Darwin, and More . edited by Michael Anderson. New York: Britannica Educational Publishing, 2013.

DK. Explorers: Tales of Endurance and Exploration . New York: Tall Tree Ltd., 2010.

Fausto, Boris. A Concise History of Brazil . New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Koch, Peter O. To the Ends of the Earth: The Age of the European Explorers . Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2003.

Olson, James Stuart, ed. Historical Dictionary of European Imperialism . New York: Greenwood Press, 1991.

Subramanian, V. K. The Great Ones Vol. IV . New Delhi: Abhinav Publications, 2005.

- Original "EXPLORATION through the AGES" site

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

- Documentary

- Entertainment

- Building Big

- How It’s Made

- Monarchs and Rulers

- Travel & Exploration

Pedro Álvares Cabral: The Discovery of Brazil

Pedro Álvares Cabral, a name etched in the annals of maritime exploration, is an enigmatic figure of enduring fascination and controversy. Most famous for his discovery of Brazil in 1500, he is - astonishingly - believed to be one of the first humans in history to have set foot on four continents - Europe, America, Africa and Asia.

The fifteenth century was the start of the Age of Discovery and some of the greatest maritime adventurers in history, including Vasco da Gama, Piri Reis, Zheng He, Christopher Columbus, Amerigo Vespucci and Bartolomeu Dias, sailed the world’s oceans searching for new and uncharted worlds. Among them was Pedro Cabral, the original accidental tourist.

Remarkably, the voyages of Cabral were largely forgotten for over three hundred years while the achievements of contemporary explorers such as Christopher Columbus and Vasco da Gama were widely lauded. Yet, the significance of his discovery cannot be overstated, as it led to the Portuguese colonisation of Brazil, which would go on to have profound implications for the indigenous populations and the future geopolitical landscape.

This is the remarkable story of the Cabral Expedition and the discovery of Brazil.

The Early Life of Pedro Álvares Cabral

Portrait of Pedro Alvares Cabral. (Credit: DeAgostini via Getty Images)

Unlike most of the well-known fifteenth and sixteenth century explorers whose life histories are often chronicled in intricate detail, very little is known about the early life of Pedro Álvares Cabral, sometimes written as Pedro Cabral or Pedro Alvares.

It’s believed he was born in the late 1460s, possibly 1467 or 1468, in the small central Portuguese town of Belmonte, around three hundred kilometres northeast of Lisbon. He was christened Pedro Álvares de Gouveia (his mother’s surname) and is said to have taken the name Cabral, the surname of his father, as late as 1503 when his elder brother died.

The family were considered members of the lower nobility and he would probably have received a well-rounded education, befitting someone of his social standing, which would have included training in navigation and military tactics. His upbringing in a nation at the forefront of maritime exploration undoubtedly set the stage for his future endeavours.

As the early stages of his career progressed, Pedro Cabral was in service at the court of King Manuel I. The King recognized his contributions by granting him a substantial yearly stipend of 30,000 reals. In addition, Cabral was bestowed with the prestigious title of Fidalgo, serving as a counsellor to the King. Further elevating his status, he was appointment as a Knight of the Order of Christ, an esteemed order that succeeded the legendary Knights Templar in Portugal.

The Voyages of Cabral

After da Gama successfully established a sea route to India, paving the path for Portugal’s expansive colonial empire across South America, Africa, parts of Asia, and numerous Atlantic islands, King Manuel I assigned Cabral the responsibility of commanding a second voyage to further this exploration.

Cabral was appointed Capitão-mor, or Major-Captain, of a thirteen-ship fleet comprising 1,500 men, designed to establish trade relations in India and to spread the word of Catholicism. The voyages of Cabral were to follow the same route da Gama took three years previously, and he was also asked to go further west into the Atlantic to see if there were lands there which could be claimed by the Portuguese crown.

The king spoke of the great confidence he had in Pedralvares de Gouveia (as Cabral’s name was often written), however it’s believed Cabral had very little sailing experience. Bizarrely, it was a long-standing Portuguese custom to appoint noblemen and those loyal to the king to naval commands, regardless of professional competence.

Captaining other ships in the fleet were experienced mariners including brothers Bartolomeu Dias and Diogo Dias, as well as Nicolau Coelho, but Pedro Alvares was in overall command.

The fleet left Lisbon at midday on March 9, 1500 destined for India, however they made a detour on the way.

The Route to Brazil: By Accident or Design?

Cabral arriving in Porto Seguro on the coast of Brazil (Credit: Pictures from History / Contributor via Getty Images)

After sailing down the North African coast, the Cabral Expedition passed Gran Canaria, the third-largest of Spain’s Canary Islands on March 14, and a week or so later on March 22, they landed at Cape Verde, around 400 miles off the coast of Dakar in Senegal.

Sailing southwest, the flotilla crossed the equator around April 9 and, as Cabral’s fleet navigated the Atlantic, they drifted westward, possibly due to navigational errors or the South Atlantic currents. This diversion from the planned route brought them to the northeastern coast of present-day Brazil on April 22, 1500.

But did the fleet end up there accidentally, or did they go there intentionally?

The circumstances surrounding Pedro Álvares Cabral’s arrival in Brazil in 1500 have been a subject of intense debate among maritime historians for centuries, with two prevailing theories. It was either an accidental discovery or an intentional landing based on prior, possibly secret, knowledge.

Accidental Discovery

The traditional and most widely accepted theory is that Cabral’s fleet stumbled upon Brazil by accident. This view suggests that Pedro Cabral, intending to follow Vasco da Gama’s sea route to India, was pushed off course by the prevailing winds and currents in the South Atlantic. These conditions could have driven the fleet westward, leading them to the coast of Brazil. This theory is supported by the fact that navigating the open ocean in the sixteenth century was fraught with uncertainties, and navigational errors were common.

Prior Knowledge

Another theory suggests that the Portuguese, before the voyages of Cabral, had secret knowledge of the existence of a landmass in the South Atlantic. Some historical maps, like the Cantino Planisphere, suggest that the Portuguese might have known about Brazil’s existence before Pedro Álvares Cabral’s official discovery. These maps show a fragmented Brazilian coastline that is too accurately depicted for a new discovery.

Did Portugal, engaged in a naval rivalry with Spain, keep this knowledge secret to secure its claims to new territories under the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, which divided newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Portuguese and the Spanish Empires?

While the accidental discovery theory remains the most widely accepted, the possibility of prior knowledge and a deliberate voyage to Brazil cannot be entirely discounted. The true nature of the Cabral Expedition to Brazil may lie somewhere between these two theories, reflecting the complex interplay of exploration, navigation, and geopolitics during the Age of Discovery.

The Original Mission

Cape Of Good Hope, South Africa. (Credit: Universal History Archive / Contributor via Getty Images)

After Pedro Álvares Cabral’s fleet mistakenly – or deliberately – landed in Brazil in 1500, they did not immediately return to Portugal. After claiming the land for the Portuguese crown and engaging briefly with the indigenous population, Cabral’s fleet sailed eastward across the Atlantic.

The fleet navigated around the southern tip of Africa, following the route pioneered by da Gama. After overcoming the challenges of the Cape of Good Hope, they reached the west coast of India, arriving at Calicut (present-day Kozhikode). Here, Cabral attempted to establish trade relations, one of the key goals of his voyage.

The journey back to Portugal was fraught with challenges, including conflicts with local rulers as well as severe storms. Despite these obstacles and the loss of several ships and crew, Pedro Cabral and the remainder of his fleet made their way back to Lisbon, arriving in dribs and drabs between June and July 1501.

One historian said that ‘few voyages to Brazil and India were so well executed as Cabral’s.’ It started a ‘Portuguese seagoing empire from Africa to the Far East’ and established a ‘land empire in Brazil.’

The Later Years of Pedro Álvares Cabral

A portrait of Pedro Alvares Cabral. (Credit: Pictures from History / Contributor via Getty Images)

Like his early life, little is known with any degree of certainty of the years after his monumental voyage.

It’s believed that King Manuel I gave Cabral a second command to return to India and preparations were made, however for reasons which have been lost to history, Cabral was relieved of his command in favour of da Gama. There may have been a falling out between Cabral and the king which it seems led to the former to leave the royal court for good, probably around late 1502.

It’s also thought that in 1503, Pedro Alvares married Lady Isabel de Castro, a descendent of fourteenth century Portuguese king Fernando I and niece of Afonso de Albuquerque, one of Portugal’s greatest statesmen and generals. They are said to have had at least four children – possibly six – and while he was still being paid his allowance of 30,000 reals (topped up by a further 2,437 reals after a promotion), he withdrew into obscurity in around 1509 to the town of Santarém, 40 miles northeast of Lisbon.

He died there, aged around 52 or 53, probably in 1520.

The Accidental Tourist: The Legacy of Pedro Álvares Cabral

Pedro Alvares Cabral landing at Terra da Vera Cruz, Brazil (Credit: Kean Collection via Getty Images)

The Cabral Expedition to Brazil stands as a pivotal moment in the annals of exploration, marking not just the discovery of a new land but also the beginning of a complex and transformative era.

Whether the discovery was a serendipitous accident or a result of secretive knowledge and strategic intent, Cabral’s journey significantly altered the course of history. His legacy, woven into the fabric of both Portuguese and Brazilian identities, encapsulates the spirit of the Age of Discovery – a time characterised by exploration, geopolitical rivalries, and the profound consequences of cultural and economic exchanges.

As historians continue to debate the intricacies of his voyage, Pedro Álvares Cabral remains an emblematic figure, symbolising the unforeseen impacts of exploration and the enduring intrigue of historical mysteries.

You May Also Like

Unraveling the secrets of the betz mystery sphere, the legend of aztlan: mythical origin of aztec civilisation, the beast of gevaudan: france’s legendary nightmare, the piltdown man hoax: unravelling a scientific scandal, explore more, adam’s calendar: humanity’s oldest timekeeper, olivier levasseur: the pirate’s code and buried treasure, skyquake: the mysterious sounds from the sky, who started april fools’ day, zosimos of panopolis: alchemy and the quest for knowledge, the mystery of costa rica spheres: ancient artifacts unveiled.

- Pedro Álvares Cabral

John Florens | Dec 26, 2023

Table of Content

Early years, discovery of brazil, trip to india, return to portugal, posthumous rehabilitation, hypothesis of intentional discovery.

Pedro Álvares Cabral (Belmonte, 1467 or 1468 - Santarém, c. 1520) was a Portuguese nobleman, military commander, navigator and explorer, credited as the discoverer of Brazil. He undertook significant exploration of the northeast coast of South America, claiming it for Portugal. Although details of Cabral's life are sparse, it is known that he came from a noble family placed in the interior province and received a good formal education.

He was appointed to lead an expedition to India in 1500, following the route newly opened by Vasco da Gama, bypassing Africa. The goal of this venture was to return with valuable spices and establish trade relations in India - circumventing the monopoly on the spice trade, then in the hands of Arab, Turkish, and Italian traders. There, his fleet of 13 ships moved far from the African coast, perhaps intentionally, landing on what he initially thought was a large island he named Vera Cruz (True Cross) and to which Pero Vaz de Caminha refers. He explored the coastline and realized that the large land mass was probably a continent, then dispatched a ship to notify King Manuel I of the discovery of the land. Since the new territory was within the Portuguese hemisphere according to the Treaty of Tordesillas, he claimed it for the Portuguese Crown. He had landed in South America, and the lands he had claimed for the Kingdom of Portugal would later constitute Brazil. The fleet refueled and continued eastward, in order to resume the voyage to India.

On that same expedition a storm in the South Atlantic caused the loss of seven ships; the remaining six vessels eventually found themselves in the Mozambique Channel before proceeding to Calicut, India. Cabral was initially successful in negotiating spice trading rights, but Arab traders saw the Portuguese business as a threat to their monopoly and provoked a Muslim and Hindu attack on the Portuguese entrepôt. The Portuguese suffered several casualties and their facilities were destroyed. Cabral took revenge for the attack by sacking and burning the Arab fleet, and then bombarded the city in retaliation for his ruler's inability to explain what had happened. From Calicut, the expedition headed for Cochin, another Indian city-state, where Cabral befriended its ruler and loaded his ships with coveted spices before returning to Europe. Despite the loss of life and ships, Cabral's voyage was considered a success after his return to Portugal. The extraordinary profits from the sale of the spices bolstered the finances of the Portuguese Crown and helped lay the foundation for a Portuguese Empire that would stretch from the Americas to the Far East.

Cabral was later passed over when a new fleet was assembled to establish a more robust presence in India, possibly as a result of a disagreement with Manuel I. Having lost the king's preference, he retired from public life, and there are few records of the latter part of his life. His accomplishments fell into oblivion for more than 300 years. A few decades after Brazil's independence from Portugal in the 19th century, Cabral's reputation began to be rehabilitated by Emperor Pedro II of Brazil. Since then, historians have debated whether Cabral was the discoverer of Brazil and whether the discovery was accidental or intentional. The first doubt has been resolved by the observation that the few superficial encounters made by explorers before him were barely noticed and contributed nothing to the future development and history of the land that would become Brazil, the only nation in the Americas where Portuguese is the official language. As to the second question, no definitive consensus has been formed and the hypothesis of intentional discovery lacks solid evidence. Nevertheless, although his prestige was overshadowed by the fame of other explorers of the time, Cabral is today considered one of the most important personalities of the Age of Discovery.

Born in Belmonte and raised as a member of the Portuguese nobility, Cabral was sent to the court of King Afonso V in 1479, when he was about 12 years old. He was educated in humanities and trained to fight and take up arms. He was about 17 years old on June 30, 1484, when he was made a moço fidalgo (a minor title usually given to young noblemen) by King João II.

Records of his actions before 1500 are extremely incomplete, but Cabral may have toured North Africa, as his ancestors had done and was commonly done by other young noblemen of his time. King Manuel I, who had ascended to the throne two years earlier, granted him an annual grant of 30,000 reals on April 12, 1497. At the same time, he received the title of nobleman of the King's Council and was made a Knight of the Order of Christ. There is no image or detailed physical description of Cabral contemporary to his time. It is known that he was strong and equaled his father in height (1.90 meters). Cabral's character has been described as cultured, courteous, generous, tolerant of enemies, and very concerned with the respect he felt his nobility and position demanded.

On February 15, 1500, Cabral was appointed Captain Major of an expedition to India. It was the custom of the time for the Portuguese Crown to appoint noblemen to command naval and military expeditions, regardless of their experience or professional competence. This was the case for the captains of the ships commanded by Cabral - most were noblemen like himself. This practice was risky, since authority could fall into the hands of highly incompetent and incapable people as it could also fall into the hands of talented leaders such as Afonso de Albuquerque or João de Castro.

Few details regarding the criteria used by the Portuguese government to choose Cabral as head of the expedition to India have survived the passage of time. In the royal decree that appointed him captain-major, the reasons given are "merits and services". Nothing else is known about these qualifications. According to historian William Greenlee, King Manuel I "undoubtedly knew him well at court." This, along with "the role of the Cabral family, their unquestioning loyalty to the Crown, Cabral's personal appearance, and the ability he had demonstrated at court and in council were important factors." Also in his favor may have been the influence of two of his brothers, who were on the king's council. Given the level of political intrigue present at court, Cabral may have been part of a faction that favored his appointment. Historian Malyn Newitt subscribes to the idea of some kind of hidden maneuvering, saying that Cabral's choice "was a deliberate attempt to balance the interests of rival factions of the noble families, for it appears that he had no other qualities for the recommendation and no experience in commanding great expeditions."

Cabral became the military head of the expedition, while more experienced navigators were assigned to the expedition to assist him in naval matters. The most important of these were Bartolomeu Dias, Diogo Dias and Nicolau Coelho. These navigators would command, together with the other captains, 13 ships. Of this contingent, 700 were soldiers, though most were common commoners who had no previous combat training or experience.

The fleet had two divisions. The first was composed of nine ships and two caravels and headed toward Calicut, India, with the objective of establishing trade relations and a trading post. The second division, consisting of one ship and one caravel, sailed from the port of Sofala, in present-day Mozambique. As a reward for leading the fleet, Cabral was entitled to 10 thousand cruzados (old Portuguese currency equivalent to approximately 35 kg of gold) and to buy 30 tons of pepper, at his own expense, to transport back to Europe. The pepper could then be resold to the Portuguese Crown, tax free. He was also allowed to import 10 boxes of any other type of spice, duty free. Although the journey was extremely dangerous, Cabral had the prospect of becoming a very rich man if he returned safely to Portugal with the shipment. Spices were rare in Europe at the time and in high demand.

An earlier fleet had been the first to reach India by circumventing Africa. This expedition was led by Vasco da Gama and returned to Portugal in 1499. For decades Portugal had sought an alternative route to the East that excluded the Mediterranean Sea, then under control of the Italian maritime republics and the Ottoman Empire. Portugal's expansionism would lead first to a route to India, and later to colonization all over the world. The desire to spread Catholic Christianity in pagan lands was another factor that motivated exploration. There was also a long tradition of warfare against the Muslims, derived from the fight against the Moors during Portuguese nation-building. The struggle expanded first to North Africa and eventually to the Indian subcontinent. An additional ambition motivating the explorers was the search for the mythical Preste João - a powerful Christian king with whom an alliance could be forged against Islam. Finally, the Portuguese Crown sought a share in the lucrative slave and gold trade in West Africa and in the spice trade from India.

The fleet, under the command of Cabral, then 32-33 years old, departed Lisbon on March 9, 1500 at noon. The previous day, the crew had received a public farewell that included a mass and celebrations attended by the king, the court, and a huge crowd. On the morning of March 14, the fleet passed Gran Canaria, the largest of the Canary Islands. It then set sail for Cape Verde, a Portuguese colony on the west coast of Africa, which was reached on March 22. The next day, a 150-man ship, commanded by Vasco de Ataíde, disappeared without trace. The fleet crossed the Equator on April 9 and sailed westward as far away from the African continent as possible, using a navigation technique known as the sea turn. The sailors spotted seaweed on April 21, which led them to believe they were close to the coast. They were proven right the afternoon of the next day, Wednesday, April 22, 1500, when the fleet anchored near what Cabral christened Mount Pascoal (since that was Easter week). The mount is located on what is now the northeastern coast of Brazil.

The Portuguese detected the presence of inhabitants on the coast, and the captains of all ships gathered aboard Cabral's ship on April 23. Cabral sent Nicolau Coelho, a captain who had traveled with Vasco da Gama to India, to disembark and establish contact. He set foot on land and exchanged gifts with the natives. After Coelho returned, Cabral ordered the fleet to head north, where, after a 65 km voyage, it anchored on April 24 at the place the Captain-Major called Porto Seguro. The place was a natural harbor, and Afonso Lopes (pilot of the main ship) brought two Indians on board to talk to Cabral.

Just as in the first contact, the encounter was friendly and Cabral offered the natives gifts. The inhabitants were hunter-gatherers from the stone age, whom Europeans would label generically as "Indians". The men gathered food by hunting and fishing, while the women engaged in small-scale agriculture. They were divided into numerous rival tribes. The tribe that Cabral encountered was the Tupiniquim. Some of them were nomadic and others were sedentary - having knowledge of fire, but not of metals. A few tribes practiced cannibalism. On April 26 (Easter Sunday), as more and more curious natives appeared, Cabral ordered his men to build an altar on land, where a Catholic mass was celebrated by Henrique de Coimbra - the first to be celebrated on the soil of what would later become Brazil.

The Indians were offered wine, but did not like it. Little did the Portuguese know that they were dealing with a people who had a vast knowledge of fermented alcoholic beverages, obtaining them from roots, tubers, barks, seeds and fruits, totaling more than eighty types.

The next few days were spent storing water, food, wood and other supplies. The Portuguese also built a huge wooden cross - perhaps seven meters high. Cabral found that the new land was east of the demarcation line between Portugal and Spain that had been established in the Treaty of Tordesillas. The territory was therefore within the hemisphere assigned to Portugal. To solemnize Portugal's claim to those lands, the wooden cross was erected and a second mass was celebrated on May 1. In honor of the cross, Cabral named the newly discovered land Ilha de Vera Cruz. The next day, a supply ship under the command of Gaspar de Lemos (there is a conflict between sources about who was sent), returned to Portugal to inform the king of the discovery, via the letter written by Pero Vaz de Caminha.

The fleet resumed its journey on May 2, 1500, sailing along the east coast of South America. In doing so, Cabral convinced himself that he had found an entire continent, rather than an island. Around May 5, the fleet turned eastward toward Africa. of May, the ships encountered a storm in the South Atlantic high pressure zone, resulting in the loss of four ships. The exact location of the disaster is unknown - speculation ranges from near the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of the African continent to a location "within sight of the South American coast." Three ships and the caravel commanded by Bartolomeu Dias - the first European to round the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 - sank, losing 380 men.

The remaining ships, hampered by bad weather and with their equipment damaged, separated. One of the ships that had broken up, commanded by Diogo Dias, drifted alone ahead, while the other six managed to regroup. They came together in two formations of three ships each, and Cabral's group sailed east, past the Cape of Good Hope. Having determined their position and sighted land, they turned north and landed somewhere in the archipelago of the First and Second Islands, off East Africa and north of Sofala. The main fleet remained near Sofala for ten days while it was repaired. The expedition then headed north, reaching Quíloa on May 26, where Cabral made an unsuccessful attempt to negotiate a trade treaty with the local king.

From Quíloa, the fleet sailed to Melinde, where it landed on August 2. Cabral met with the local king, with whom he established friendly relations and exchanged gifts. Also in Melinde, pilots were recruited for the last leg of the journey to India. Before their final destination, they disembarked at Angediva, an island where the ships on their way to Calicut were supplied. There, the ships were pulled ashore, caulked and painted. Final preparations were made for the meeting with the ruler of Calicut.

The fleet left Angediva and arrived in Calicut on September 13. Cabral succeeded in negotiations with the Samorim (title given to the ruler of Calicut) and obtained permission to set up a trading post and warehouse in the city-state. In the hope of further improving relations, Cabral dispatched his men on several military missions at the request of the Samorim. of December, the fiefdom came under surprise attack by some 300 (according to other accounts, perhaps even thousands) Muslim Arabs and Hindu Indians. Despite a desperate defense by the besteiros, more than 50 Portuguese were killed. The remaining defenders retreated to their ships, some swimming. Thinking that the attack was the result of unauthorized incitement by envious Arab traders, Cabral waited 24 hours to get an explanation from the ruler of Calicut, but no apology was forthcoming.

The Portuguese were outraged by the attack on the trading post and the death of their comrades and attacked 10 Arab merchant ships anchored in the port. They killed about 600 crew members and confiscated the cargo before setting the ships on fire. Cabral also ordered his ships to bombard Calicut for a full day in retaliation for the violation of the agreement. The massacre was attributed, in part, to Portuguese animosity toward Muslims, resulting from centuries of conflict with the Moors in the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa. In addition, the Portuguese were determined to dominate the spice trade and had no intention of allowing competition to flourish. The Arabs also had no interest in allowing the Portuguese to break their monopoly on spices. The Portuguese had begun by insisting that they be given preferential treatment in all aspects of trade. Manuel I's letter delivered by Cabral to the ruler of Calicut - translated by the latter's Arab interpreters - called for the exclusion of Arab traders. The Muslim merchants, believing they were about to lose their trading opportunities and livelihood, would have tried to turn the Hindu ruler against the Portuguese. Portuguese and Arabs were very suspicious of each other, in every action.

For historian William Greenlee, the Portuguese realized that "they were few in number and that those who would come to India in future fleets would also always be outnumbered; so this treachery should be punished so decisively that the Portuguese would be feared and respected in the future. It was their superior artillery that would enable them to accomplish this goal." Thus, the Portuguese set a precedent for the behavior of European explorers in Asia during the following centuries.

Notices in the accounts of Vasco da Gama's voyage to India led King Manuel I to inform Cabral of another port, south of Calicut, where trade relations could also be established. The city in question was Cochin, where the fleet landed on December 24. Cochin was nominally a vassal territory of Calicut, as was also dominated by other Indian city-states. The ruler of Cochin was eager to gain independence for the city, and the Portuguese were willing to exploit Indian disunity - as the British would also do 300 years later. The tactic would eventually secure Portuguese hegemony over the region. Cabral forged an alliance with the ruler of Cochin, and with leaders of other city-states, and was able to establish a trading post. Finally, laden with precious spices, the fleet headed to Cananor to trade once more before setting sail on its return voyage to Portugal on January 16, 1501.

The expedition headed for the east coast of Africa. One of the ships ran aground on a sandbank and began to sink. As there was no room in the other ships, the cargo was abandoned and Cabral ordered the ship to be set on fire. The fleet then proceeded to the Island of Mozambique (northeast of Sofala) to provide itself with supplies so that the ships would be ready for the rough passage around the Cape of Good Hope. A caravel was sent to Sofala - another of the expedition's objectives. A second caravel, considered the fastest ship in the fleet and captained by Nicolau Coelho, was sent ahead of the others to give the king advance notice of the successful journey. A third ship, commanded by Pedro de Ataíde, separated from the fleet after leaving Mozambique.

On May 22, the fleet - now reduced to only two ships - passed the Cape of Good Hope. They arrived in Bezeguiche (now the city of Dakar, located near Cape Verde), on June 2. There, they found not only Nicolau Coelho's caravel, but also the ship commanded by Diogo Dias - which had been lost for over a year after the disaster in the South Atlantic. The ship had been through several adventures and was in very poor condition, with only seven sick and malnourished men on board - one of whom was so weak that he died of happiness at seeing his companions again. Another Portuguese fleet was also found anchored in Bezeguiche. After King Manuel I was informed of the discovery of Brazil, he sent a smaller fleet to explore it. One of its navigators was Américo Vespúcio (an Italian explorer who would name America after him), who told Cabral details of his exploration, confirming to him that he had indeed landed on an entire continent and not just an island.

Nicolau Coelho's caravel sailed first from Bezeguiche and arrived in Portugal on June 23, 1501. Cabral's ship stayed behind, waiting for Pedro de Ataíde's missing ship and the caravel that had been sent to Sofala. Both ships eventually turned up and Cabral arrived in Portugal on July 21, 1501, with the other ships arriving during the following days. In all, two ships returned empty, five were fully loaded, and six were lost. However, the cargoes carried by the fleet generated profits of up to 800% for the Portuguese Crown. After the spices were sold, the revenues covered the costs of equipping the fleet and the ships that were lost, generating a profit that alone exceeded the total sum of those costs. "Undaunted by the unprecedented losses he had suffered, by the time he reached the coast of East Africa, Cabral pressed on with the accomplishment of his assigned task and was able to inspire the surviving officers and men with equal courage," says historian James McClymont. "Few voyages to Brazil and India were as well executed as Cabral's," said historian Bailey Diffie, for whom the voyage set a path between the immediate opening of "a Portuguese maritime empire from Africa to the Far East," and later to a "land empire in Brazil."

After Cabral's return, King Manuel I began to plan another fleet to make the voyage to India and to avenge the Portuguese losses in Calicut. Cabral was chosen to command this "Fleet of Vengeance", as it was called. For eight months Cabral made all the preparations for the voyage, but for reasons that remain uncertain, he was removed from command. Apparently, it had been proposed to give another navigator, Vicente Sodré, independent command over part of the fleet - and Cabral strongly opposed this. It is not known whether he was dismissed or asked to be released from his post, in any case, when the fleet sailed in March 1502, its commander was Vasco da Gama, a maternal nephew of Vicente Sodré, and not Cabral. It is known, however, that hostility arose between the factions supporting Vasco da Gama and Cabral. At some point, Cabral left the court permanently. The king was greatly angered by the quarrel, to the point that simply mentioning the matter in his presence could result in banishment from court, as occurred with one of Vasco da Gama's supporters.

Despite the loss of the king's favors, Cabral arranged an advantageous marriage in 1503 with D. Isabel de Castro, a wealthy noblewoman and descendant of King Fernando I. Her mother was the sister of Afonso de Albuquerque, one of Portugal's greatest military leaders during the Age of Discovery. The couple had at least four children: two boys (Fernão Álvares Cabral and António Cabral) and two girls (Catarina de Castro and Guiomar de Castro). They would also have had two other daughters, named Isabel and Leonor, according to other sources, which also say that Guiomar, Isabel, and Leonor were admitted into religious orders. Firstborn Ferdinand would have been the only one of Cabral's sons to give him heirs, since Antonio died in 1521 without marrying. Afonso de Albuquerque tried to intercede in Cabral's favor and, on December 2, 1514, asked Manuel I to pardon him and allow his return to court, but was unsuccessful.

Suffering from recurring fever and a tremor (possibly the result of malaria) since his voyage, Cabral retired to Santarem in 1509. He spent his last years there. Only sparse information is available about his activities during that time. According to a royal letter dated December 17, 1509, Cabral became a party to a dispute over a land transaction involving part of the property that belonged to him. Another letter from the same year reports that he was to receive certain privileges for undisclosed military service. In 1518, or perhaps earlier, he was elevated from nobleman to knighthood in the King's Council, and was entitled to a monthly allowance of 2,437 reals. This was in addition to the annual pension granted to him in 1497, which was still being paid. Cabral died of unspecified causes, probably in 1520, and was buried inside the Chapel of São João Evangelista in the Church of the Old Convent of Graça in Santarem.

The first permanent Portuguese settlement in the land that would become Brazil was São Vicente, established in 1532 by Martim Afonso de Sousa. As the years passed, the Portuguese slowly expanded the borders of their colony westward, conquering the lands of both Amerindians and Spaniards. Brazil had secured most of its current borders by 1750, and was considered by Portugal to be the most important part of its vast maritime empire. On September 7, 1822, the heir to King João VI, Prince Pedro, secured Brazil's independence from Portugal and became its first emperor.

Cabral's discoveries, and even the place where he was buried, had been forgotten for almost 300 years since his expedition. This situation began to change in the early 1840s, when Emperor Pedro II, successor and son of Pedro I, sponsored research and publications on Cabral's life and expedition through the Brazilian Historical and Geographical Institute. This was part of the Emperor's ambitious plan to encourage and reinforce a sense of nationalism in Brazil's diverse society - giving citizens a common identity and history as residents of the only Portuguese-speaking country in the Americas. The beginning of the resurgence of interest in Cabral had resulted from the discovery of his tomb by the Brazilian historian Francisco Adolfo de Varnhagen (later named Viscount of Porto Seguro) in 1839. The completely neglected state in which Cabral's tomb was found almost provoked a diplomatic crisis between Brazil and Portugal - the latter was then ruled by Pedro II's older sister, Maria II.

In 1871, the Brazilian emperor - then on an official visit to Europe - visited Cabral's tomb and proposed an exhumation for scientific purposes, which took place in 1882. In a second exhumation, in 1896, the removal of an urn containing soil and bone fragments was authorized. Although his remains are still in Portugal, the urn was eventually brought to the Old Cathedral of Rio de Janeiro on December 30, 1903. Since then, Cabral has become a national hero of Brazil. In Portugal, however, authors claim that his prestige is overshadowed by Vasco da Gama's fame. For historian William Greenlee, Cabral's voyage is important "not only because of its position in the history of geography, but because of its influence on the history and economy of the time." While this author acknowledges that few voyages "have been of greater importance to posterity," he also says that "few were less appreciated in their time." However, historian James McClymont stated that "Cabral's position in the history of Portuguese conquests and discoveries is impregnable despite the supremacy of greater or more fortunate men. According to him, Cabral "will always be remembered in history as the principal, if not the first, discoverer of Brazil.

A controversy that has occupied scholars for more than a century is whether Cabral's discovery was by chance or intentional. In the latter case, it would mean that the Portuguese had at least some inkling that there was a land to the west. The question was first raised by Emperor Pedro II in 1854 during a session of the Brazilian Historical and Geographical Institute when he asked researchers whether the discovery might have been intentional.

Until the 1854 conference, the widespread assumption was that the discovery had been an accident. Early works on the subject defended this view, such as História do Descobrimento e Conquista da Índia (published in 1541) by Fernão Lopes de Castanheda, Décadas da Ásia (1552) by João de Barros, Crônicas do Felicíssimo Rei D. Manuel (1558) by Damião de Góis, Lendas da Índia (1561) by Gaspar Correia, História do Brasil (1627) by Friar Vicente do Salvador and História da América Portuguesa (1730) by Sebastião da Rocha Pita.

The first work to defend the idea of intentional discovery was published in 1854 by Joaquim Noberto de Sousa e Silva, after D. Pedro II started the debate. Since then, several scholars have supported the idea, such as Francisco Adolfo de Varnhagen, Pedro Calmon, and Mário Barata. For historian Hélio Vianna, "although there are signs of the intentionality" of Cabral's discovery, "based mainly on previous knowledge or suspicions of the existence of lands on the edge of the South Atlantic," there is no irrefutable evidence to prove it. This opinion is also shared by historian Thomas Skidmore. The debate about whether the discovery was deliberate or not is considered "irrelevant" by historian Charles R. Boxer. For historian Anthony Smith, the conflicting claims "will probably never be resolved."

There is concrete evidence that two Spaniards, Vicente Yáñez Pinzón and Diego de Lepe, traveled along the northern coast of Brazil between January and March 1500. Pinzón went from Cabo de Santo Agostinho to the mouth of the Amazon River. There, he encountered another Spanish expedition, led by Lepe, which would reach the Oiapoque River in March. The reason Cabral is considered the discoverer of Brazil, rather than Pinzón, is due to the fact that the Spanish navigator's voyage was brief and had, according to Luso-Brazilian historians, no lasting impact. Francisco Adolfo de Varnhagen, Mário Barata agree that the Spanish expeditions did nothing to influence the development of what would become the only Portuguese-speaking nation in the Americas - with a unique history, culture and society, differentiating it from the Hispanic-American societies that dominate the rest of the continent.

Although it is notorious that the Portuguese did not know of the existence of Brazil before Pedro Álvares Cabral's arrival - since Cabral's squadron thought to have discovered an island -, there is a theory based on an interpretation of the book Esmeraldo de Situ Orbis (1505) that points Duarte Pacheco Pereira as the possible discoverer of Brazil, since he supposedly commanded a secret expedition that would have traveled along the Brazilian coast and the Caribbean Sea at the end of the 15th century. The trip aimed to identify the territories that belonged to Portugal or Castile according to the Treaty of Tordesillas of 1494 - Pacheco Pereira participated in the treaty negotiations. The possible existence of a policy of secrecy of the Portuguese monarchs was written about in the first half of the 20th century by historian Damião Peres, but it does not hold up, since it was common practice, in the absence of a treaty, to claim sovereignty of a land by publicizing its discovery.

Cabral is one of Brazil's national heroes, being honored annually on April 22. However, the date is not a national holiday. On April 22, 2000, a series of events promoted by the Brazilian government marked the celebrations of the 500th anniversary of the discovery of Brazil, which led to strong protests from the indigenous peoples and the request for the resignation of the then president of the National Indian Foundation, Carlos Frederico Marés de Souza Filho.

In 1900, as part of the celebrations of the 400th anniversary of Brazil's discovery, a monument by Rodolfo Bernardelli in honor of Cabral was inaugurated at the Glória square in Rio de Janeiro. Other Brazilian cities have also honored the explorer by naming public roads after him - the most notable of these is Avenida Álvares Cabral in Belo Horizonte. There are also several public schools and other private establishments that bear the name of Pedro Álvares Cabral.

In Lisbon, a monument in honor of Cabral was erected on the avenue named after the explorer in the parish of Santa Isabel. The statue, inaugurated in 1940, is a replica of Bernardelli's statue and was a gift from the Vargas government to the Portuguese people. Also inaugurated in 1940 (and rebuilt in 1960), the Padrão dos Descobrimentos in Belém, Lisbon, depicts Pedro Álvares Cabral among the notable figures of the Age of Discovery. Likewise, his hometown honored him with a statue, as did the city where he is buried.

The old Brazilian banknote of one thousand cruzeiros novos (1967-1970), had the effigy of Pedro Álvares Cabral, as well as the commemorative banknote of ten reais (2000) and the one centavo coin, which currently has limited circulation. In Portugal, the old 100 escudos banknote from the 1950s and the 1,000 escudos banknote from 1996 also had the portrait of Álvares Cabral, the first one accompanied by an image representing the discovery of Brazil.

Little is known for sure about the life of Pedro Alvares Cabral before or after the voyage that took him to Brazil. He is believed to have been born in 1467 or 1468 - the earlier year is more likely - in Belmonte, about 30 km away from the present-day city of Covilhã in central Portugal.

He was baptized as Pedro Álvares de Gouveia, and only years later, supposedly after the death of his older brother in 1503, he began to use his father's surname.

He was one of five sons and six daughters of:

According to family tradition, the Cabrals were descendants of Carano, the legendary first king of Macedonia. Carano was, in turn, a supposed seventh-generation descendant of the Greek demigod Hercules. Myths aside, historian James McClymont believes that another family tale may hold clues to the true origin of the Cabral family. According to this tradition, the Cabrals derive from a Castilian clan called Cabreiras that possessed a similar coat of arms. The Cabral family gained prominence during the 14th century. Álvaro Gil Cabral (Cabral's great-great-grandfather and a frontier military commander), was one of the few Portuguese nobles to remain loyal to King João I during the war against the king of Castile. As a reward, D. João I presented Álvaro Gil with the ownership of the hereditary fief of Belmonte.

His family coat of arms was elaborately designed with two purple goats on a silver field. Purple represents allegiance and the goats derive from the family name. However, only his older brother had the right to use the family coat of arms.

- a b c Bueno (1998), p. 35.

- a b c d Subrahmanyam (1997), p. 177.

- Newitt (2005), p. 64.

- Su nombre fue escrito durante su vida como «Pedro Álvarez Cabral», «Pero Álvares Cabral», «Pedr'Álvárez Cabral», «ortográficas siguen siendo utilizadas. Este artículo utiliza la grafía más común.[Mc. 1][1][2][3][G. 1]

- Los orígenes más remotos del Imperio portugués datan de la ascensión al trono de D. João I en 1385 y las posteriores guerras de conquista en África del Norte dirigidas por él y los envíos realizados por su hijo. La fundación del Imperio portugués, sin embargo, estaba muy relacionada con el descubrimiento de un territorio más importante que pasaría a convertirse en lo que hoy es Brasil y el establecimiento, de las relaciones comerciales en la India.[D. 1]

- ^ His name was spelled during his lifetime as "Pedro Álveres Cabral", "Pero Álvares Cabral", "Pedr'Álváres Cabral", "Pedrálvares Cabral", "Pedraluarez Cabral", among others. This article uses the most common spelling. See McClymont 1914, p. 1, Tomlinson 1970, p. 22, Calmon 1981, p. 44, Capistrano de Abreu 1976, p. 25, Greenlee 1995, p. 190.

- ^ The earliest origins of the Portuguese Empire can be traced back to the accession of King João I in 1385 and his subsequent wars of conquest in North Africa, as well as Prince Henry the Navigator's exploratory voyages. The foundation of the Portuguese Empire, however, were firmly laid with the more substantial claim to the territory that would later become Brazil and the establishment of a trading concession in India. See Diffie & Winius 1977, pp. 39, 46, 93, 113, 191.

- ^ "The name used in his appointment as chief commander of the fleet for India is also Pedralvares de Gouveia." —William Brooks Greenlee in Greenlee 1995, p. xl.

- ^ "According to a family tradition the Cabraes were descended from a certain Carano or Caranus, the first king of the Macedonians and the seventh in descent from Hercules. Carano had been instructed by the Delphic Oracle to place the metropolis of his new kingdom at the spot to which he would be guided by goats and when he assaulted Edissa his army followed in the wake of a flock of goats just as the Bulgarians drove cattle before them when they took Adrianople. The king accordingly chose two goats for his cognisance and two goats passant gules on a field argent subsequently became the arms of the Cabraes. Herodotus knows nothing of Carano and the goats." —James McClymont in McClymont 1914, p. 1.

- ^ Numele său era scris în perioada vieții sale „Pedro Álvares Cabral”, „Pero Álvares Cabral”, „Pedr'Álváres Cabral”, „Pedrálvares Cabral”, „Pedraluarez Cabral”, printre altele. Aceste variații de grafie continuă să fie și ele utilizate. Acest articol folosește grafia cea mai frecventă.[3][4][5][6][7]

- ^ Primele origini ale Imperiului Portughez pot fi trasate până la urcarea pe tron a regelui João I în 1385 și la războaiele sale de cucerire în Africa de Nord, precum și la călătoriile de explorare ale lui Henric Navigatorul. Bazele Imperiului Portughez, însă, au fost puse odată cu revendicările teritoriale mai substanțiale în Brazilia și cu înființarea concesiunii comerciale în India.[8]

- ^ „Numele utilizat la numirea sa drept comandant al flotei către India este Pedralvares de Gouveia.” —William Brooks Greenlee[13]

- ^ „Conform unei tradiții a familiei, Cabrais proveneau de la un anume Carano sau Caranus, primul rege al macedonenilor și al șaptelea urmaș al lui Hercule. Lui Carano îi spusese Oracolul din Delphi să-și pună metropola noului său regat acolo unde îl vor conduce caprele și când a atacat Edissa armata sa a urmărit o turmă de capre așa cum și bulgarii au mânat capre în fruntea lor când au cucerit Adrianopolul. Regele a ales, astfel, două capre drept însemn, și deci două capre roșii pe fond argintiu au devenit stema familiei Cabraes. Herodot nu știe nimic despre acest Carano și despre capre.” —James McClymont[3]

- ^ „Un anume fidalgo care era căpitan al unei cetăți la Belmonte era cu garnizoana supusă prin înfometare de forțele invadatoare. Două capre mai trăiau în cetate. Ele au fost ucise prin porunca comandantului, tăiate în patru și aruncate dușmanului, după care asediul a fost ridicat, deoarece dușmanul a considerat că nu are rost să încerce să înfometeze o cetate care își permite să irosească astfel proviziile. Legenda vorbește și despre fiul castelanului luat prizonier și ucis și că bărbile și coarnele caprelor heraldice sunt negre în semn de doliu.” —James McClymont

Would you like to send you a similar article every day?

We promise we will not spamm you!

Please Disable Ddblocker

We are sorry, but it looks like you have an dblocker enabled.

Our only way to maintain this website is by serving a minimum ammount of ads

Please disable your adblocker in order to continue.

Dafato needs your help!

Dafato is a non-profit website that aims to record and present historical events without bias.

The continuous and uninterrupted operation of the site relies on donations from generous readers like you.

Your donation, no matter the size will help to continue providing articles to readers like you.

Will you consider making a donation today?

Pedro Alvares Cabral: The Lucky Lost Navigator Who Made Brazil Portuguese

- Read Later

Pedro Alvares Cabral was a Portuguese explorer and navigator who lived between the 15th and 16th centuries. He is generally given credit for being the first person from Europe to have ‘discovered’ the area which is today the country of Brazil. Cabral’s discovery of this new land had a huge impact on the colonial history of Portugal, as the coffers of the empire were filled with its resources. But the amateur navigator had no intention of reaching this particular far off land.

His Family Roots

Pedro Alvares Cabral was born in 1467/1468 in Belmonte, Portugal, and was the second son of Fernao Cabral and Isabel de Gouveia. The Cabrals were a noble family whose members had been in the service of the Portuguese throne for many generations. Thanks to his family’s status, Cabral was educated at the royal court, and in 1497, was appointed as a member of King Manuel I’s council.

Pedro Álvares Cabral. ( Public Domain )

In July of the same year, another famous explorer, Vasco da Gama, left Lisbon with a small exploratory force of four ships and about 170 men. His mission was to verify if there was an ocean route that connected Europe to Asia, which he succeeded in doing, having rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and arriving in Calicut, India, in 1498.

- Did Early Transatlantic Explorers Drop This Mysterious Tablet in the Brazilian Jungle?

- Explorers That Found Ancient Lost City of the Monkey God Almost Lose Their Faces to Flesh-Eating Parasite

- Did This Ancient Explorer Make It to The Arctic In 325 BC?

‘Vasco da Gama before the Zamorin of Calicut’ by Veloso Salgado, Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa. ( Public Domain )

Taking Command

In 1500, the Portuguese king decided to follow up on da Gama’s voyage, and an expeditionary force of 13 ships and about 1200 men was assembled. This fleet was placed under the command of Cabral, who is believed to have had little to no sailing experience at that point of time. It has also been suggested that he was chosen due to his connection and loyalty to the king.

In any case, the fleet left Lisbon on the March 9, 1500. Cabral was in possession of navigational charts containing the information collected from the voyages of Christopher Columbus , Vasco da Gama, and Bartolomeu Dias (who, incidentally, was a captain on one of Cabral’s vessels), and was supposed to follow the route da Gama had taken in 1497. However, the fleet sailed too far southwest into the Atlantic by mistake.

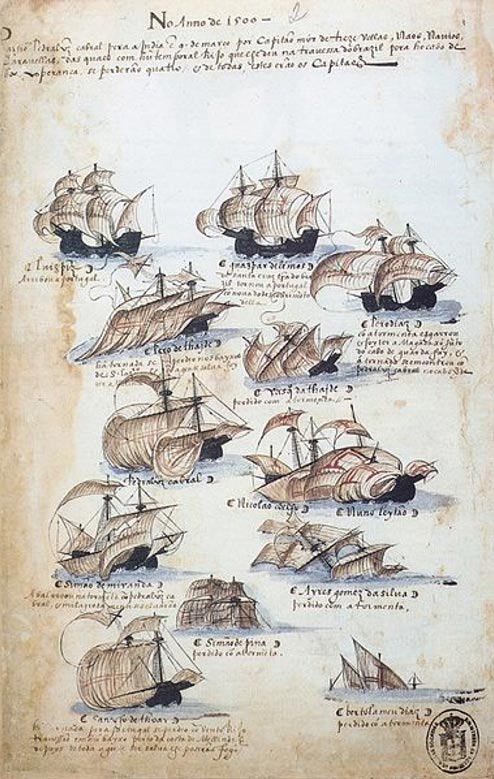

The fleet commanded by Pedro Álvares Cabral. ( Public Domain )

What Did Pedro Alvares Cabral Discover?

As a result of this error, Cabral arrived not in India, as initially planned, but in an area of the South American coast that was previously unknown. On April 22, Cabral sighted land, and his fleet made anchor at Porto Seguro, which is situated on the coast of the modern Brazilian state of Bahia.

As this area ‘belonged’ to the Portuguese, in accordance with the Treaty of Tordesillas , Cabral and men went ashore, erected a large wooden cross on the beach, and claimed it for Portugal. Believing that the land he had discovered was an island, Cabral named it the Island of the True Cross. Its name was subsequently changed to Holy Cross by King Manuel, and finally became Brazil, which is the name of a dyewood native to the country.

‘Landing of Pedro Álvares Cabral in Porto Seguro, in 1500’ (1922) by Oscar Pereira da Silva. ( Public Domain )

Cabral stayed in Brazil for 10 days, during which he met with the natives, and sent a ship back to Portugal to inform the king about his discovery. After that, Cabral continued his journey to India. The voyage went smoothly until they arrived at the Cape of Good Hope, where the fleet was caught in a terrible storm that sunk four of Cabral’s ships, including the one commanded by Dias. The survivors continued their voyage eastwards, during which the ship commanded by Diogo Dias was separated from the rest of the fleet due to bad weather and ended up discovering the island of Madagascar.

- Mystery of island visited by 15th Century Chinese Explorer Zheng He now solved

- The Calusa People: A Lost Tribe of Florida that Early Explorers Wrote Home About

- A Traveler Even After Death? The Two Tombs of Vasco da Gama

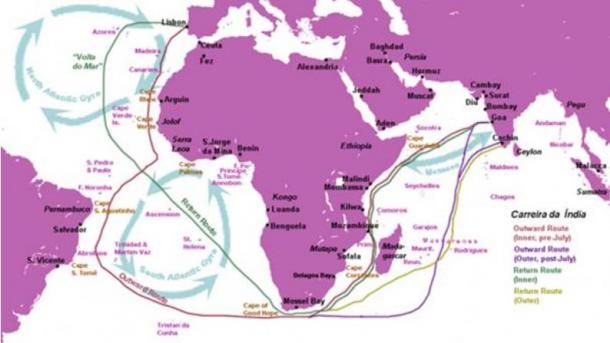

Map showing various outward and return voyages of the Portuguese 'Carreira da India' ('India Run') in the 16th century. (Walrasiad/ CC BY 3.0 )

The remaining ships in Cabral’s expeditionary force finally arrived in India in September 1500, where they were able to trade for spices. In January of the following year, Cabral’s six remaining ships were fully loaded, and began their journey back to Lisbon. In late June, the remaining ships (four, as two had foundered along the way) arrived in the Portuguese capital.

Pedro Cabral

The king was pleased with the outcome of this venture, despite the heavy losses. A new expedition to India was planned, and the king is said to have been inclined to appoint Cabral as its commander. In the end, however, it was da Gama who led this expedition. Cabral left the king’s court and retired to his estate in the province of Beira Baixa. He lived the remaining years of his life there peacefully and died in 1520.

Cabral's tomb in Santarém, Portugal. ( Public Domain )

Top Image: ‘Discovery of Brazil.’ Pedro Álvares Cabral sees the land that would later be known as Brazil for the first time. Source: Public Domain

Calmon, P., 2015. Pedro Álvares Cabral. [Online]

Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Pedro-Alvares-Cabral

Cavendish, R., 2000. Cabral Discovers Brazil. [Online]

Available at: https://www.historytoday.com/richard-cavendish/cabral-discovers-brazil

Siteseen Ltd, 2018. Pedro Alvares Cabral. [Online]

Available at: http://www.elizabethan-era.org.uk/pedro-alvares-cabral.htm

The Mariners' Museum & Park, 2018. Pedro Álvares Cabral. [Online]

Available at: https://exploration.marinersmuseum.org/subject/pedro-alvares-cabral/

www.famous-explorers.com , 2018. Pedro Álvares Cabral - Portuguese Explorer. [Online]

Available at: http://www.famous-explorers.com/famous-portuguese-explorers/pedro-alvares-cabral/

So Cabral thought that Brazil was an Island whenhe landed in the area known today as the state of Bahia, and named it “Holy Cross” These Europeans usually founded all of these INHABITED lands by mere accident, and always trying to go to India. No wonder they called the American natives Indians, and the name still stuck to the present day...

Charles Bowles

Wu Mingren (‘Dhwty’) has a Bachelor of Arts in Ancient History and Archaeology. Although his primary interest is in the ancient civilizations of the Near East, he is also interested in other geographical regions, as well as other time periods.... Read More

Related Articles on Ancient-Origins

AIR & SPACE MAGAZINE

Across the south atlantic in 1922.

On this day in 1922, a pair of Portuguese aviators, Sacadura Cabral and Gago Coutinho, set off on the first flight across the southern Atlantic

Tony Reichhardt

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

Tony Reichhardt | READ MORE

Tony Reichhardt is a senior editor at Air & Space .