About Search

Jimmy Carter

Voyager spacecraft statement by the president..

This Voyager spacecraft was constructed by the United States of America. We are a community of 240 million human beings among the more than 4 billion who inhabit the planet Earth. We human beings are still divided into nation states, but these states are rapidly becoming a single global civilization.

We cast this message into the cosmos. It is likely to survive a billion years into our future, when our civilization is profoundly altered and the surface of the Earth may be vastly changed. Of the 200 billion stars in the Milky Way galaxy, some--perhaps many--may have inhabited planets and spacefaring civilizations. If one such civilization intercepts Voyager and can understand these recorded contents, here is our message:

This is a present from a small distant world, a token of our sounds, our science, our images, our music, our thoughts, and our feelings. We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours. We hope someday, having solved the problems we face, to join a community of galactic civilizations. This record represents our hope and our determination, and our good will in a vast and awesome universe.

Note: The statement has been placed in a National Aeronautics and Space Administration Voyager spacecraft which is scheduled to be launched August 20. The statement is recorded in electronic impulses which can be converted into printed words.

Jimmy Carter, Voyager Spacecraft Statement by the President. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/243563

Filed Under

Simple search of our archives, report a typo.

TwistedSifter

The best of the visual web, sifted, sorted and summarized.

- NATURE/SPACE

- ARCHITECTURE

- PICTURE OF THE DAY

- SHIRK REPORT

- INFORMATIVE

In 1977 Jimmy Carter Put This Note on the Voyager Spacecraft

by twistedsifter

On September 5, 1977 the Voyager 1 space probe launched from Earth. Nearly 40 years and some 20.5 billion km travelled later (and counting!), the Voyager 1 remains the farthest ever spacecraft from Earth as well as the farthest ever man-made object.

In the event the probe is ever found by intelligent life forms from other planetary systems, a Golden Record containing sounds and images (selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth) can be found on board. You can learn all about the Golden Record here .

In addition, then US President Jimmy Carter penned the following note and placed it in the Voyager 1 space probe to accompany the Golden Record. It remains the only letter in history to reach extrasolar space.

Here’s to galactic civilizations far and wide 🙂

Jimmy Carter’s Voyager 1 Letter

This Voyager spacecraft was constructed by the United States of America. We are a community of 240 million human beings among the more than 4 billion who inhabit the planet Earth. We human beings are still divided into nation states, but these states are rapidly becoming a single global civilization. We cast this message into the cosmos. It is likely to survive a billion years into our future, when our civilization is profoundly altered and the surface of the Earth may be vastly changed. Of the 200 billion stars in the Milky Way galaxy, some–perhaps many–may have inhabited planets and spacefaring civilizations. If one such civilization intercepts Voyager and can understand these recorded contents, here is our message: This is a present from a small distant world, a token of our sounds, our science, our images, our music, our thoughts, and our feelings. We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours. We hope someday, having solved the problems we face, to join a community of galactic civilizations. This record represents our hope and our determination, and our good will in a vast and awesome universe.

The Golden Record

Categories: BEST OF , HISTORY , SCI/TECH , STORIES Tags: · cosmos , farthest , language , letter , NASA , space , top , us president , world record

Trending on TwistedSifter

Parents Emotionally Manipulated Grandparent Into Babysitting For 5 Days, So They Took The Kids To Disney Without The Parents

Middle Child With Special Needs Siblings Was Overlooked His Whole Life, And Family Won’t Let Him Have One Dinner He Enjoys… Even On His Birthday

One Boss Told Him He Couldn’t Take More Vacation Time, But Another Employee Helped Him Game The System

Would you like some more?

Sign up for our daily email and receive the Sifter's newest posts!

- PRIVACY POLICY

- Write For Us

- AFFILIATE DISCLOSURE

NASA Recovers Space Debris That Landed In A Florida Home

Terrible Stepmother Tried to Take Credit for Kids That Weren’t Actually Hers, So They Put Her In Her Place In Front Of People

His Mother Got Upset When His Wife Brings Crochet To Family Events, But He Threw Her Out When She Brought Her Messy Hobby To Their House

Woman Bought A Used Car And Later Found Out It Was Stolen. Now The Police Have Taken It And She’s Out $30k. – ‘It had a clean CARFAX report.’

Her Father-In-Law Acted Like A Spoiled Brat, So She Gave Him A Juice Box. Now Her Mother-In-Law Thinks She’s Rude.

Her Father-In-Law Excluded Her Son At A Holiday, So She’s Cutting Him Out Of Their Lives Completely

Copyright © 2024 · All Rights Reserved · TwistedSifter

Powered by WordPress VIP · RSS Feed · Log in

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

Dear Space Aliens: Hello! Love, Jimmy Carter

The Vault is Slate ’s history blog. Like us on Facebook , follow us on Twitter @slatevault , and find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here .

On a cold evening in 1969, a peanut farmer was standing outside a Georgia restaurant when he noticed a mysterious pulsating light in the western sky. “It was the darndest thing I’ve ever seen,” he recalled seven years later, during his successful presidential campaign. “One thing’s for sure, I’ll never make fun of people who say they’ve seen unidentified objects in the sky. If I become President, I’ll make every piece of information this country has about UFO sightings available to the public.” Indeed, Carter filed his own report of the incident with the International UFO Bureau in Oklahoma City (read it here ).

Even though Carter later came to believe that what he called “space people” hadn’t paid Earth a visit, there’s still a possibility that his words might visit them. In the summer of 1977, he penned a three-paragraph letter to accompany the Voyager spacecraft. Today, that letter is travelling beyond our Solar System at speeds of eleven miles a second. It is the first letter in history to reach extrasolar space.

Carter was not the only human to send a message on Voyager —the “ Golden Record ” stowed onboard contained greetings in languages ranging from Sumerian to Welsh, as well as short speeches from UN delegates interwoven with whale sounds. (“My dear friends in outer space,” one delegate intones over a collage of cetacean murmurs, “as you probably know, my country is situated on the west coast of the continent of Africa, a land mass more or less in the shape of a question mark.”)

Yet Carter’s letter was the longest message sent by any earthling, and the one that most fully evoked the utopian mission of Voyager . “We are a community of 240 million human beings among the more than 4 billion who inhabit the planet Earth,” he wrote. “We hope someday, having solved the problems we face, to join a community of galactic civilizations.” As I wrote recently on the new history website The Appendix , Carter was quite possibly inspired to this flight of fancy by the theatrical release of Star Wars three weeks earlier. But perhaps he was simply waxing idealistic, touched by the thought of writing the first interstellar letter in human history.

To read more histories of people and artifacts who go off the map, check out the newest issue of The Appendix.

Suggested Searches

- Climate Change

- Expedition 64

- Mars perseverance

- SpaceX Crew-2

- International Space Station

- View All Topics A-Z

Humans in Space

Earth & climate, the solar system, the universe, aeronautics, learning resources, news & events.

NASA Wins 6 Webby Awards, 8 Webby People’s Voice Awards

NASA’s CloudSat Ends Mission Peering Into the Heart of Clouds

Hubble Celebrates 34th Anniversary with a Look at the Little Dumbbell Nebula

- Search All NASA Missions

- A to Z List of Missions

- Upcoming Launches and Landings

- Spaceships and Rockets

- Communicating with Missions

- James Webb Space Telescope

- Hubble Space Telescope

- Why Go to Space

- Astronauts Home

- Commercial Space

- Destinations

- Living in Space

- Explore Earth Science

- Earth, Our Planet

- Earth Science in Action

- Earth Multimedia

- Earth Science Researchers

- Pluto & Dwarf Planets

- Asteroids, Comets & Meteors

- The Kuiper Belt

- The Oort Cloud

- Skywatching

- The Search for Life in the Universe

- Black Holes

- The Big Bang

- Dark Energy & Dark Matter

- Earth Science

- Planetary Science

- Astrophysics & Space Science

- The Sun & Heliophysics

- Biological & Physical Sciences

- Lunar Science

- Citizen Science

- Astromaterials

- Aeronautics Research

- Human Space Travel Research

- Science in the Air

- NASA Aircraft

- Flight Innovation

- Supersonic Flight

- Air Traffic Solutions

- Green Aviation Tech

- Drones & You

- Technology Transfer & Spinoffs

- Space Travel Technology

- Technology Living in Space

- Manufacturing and Materials

- Science Instruments

- For Kids and Students

- For Educators

- For Colleges and Universities

- For Professionals

- Science for Everyone

- Requests for Exhibits, Artifacts, or Speakers

- STEM Engagement at NASA

- NASA's Impacts

- Centers and Facilities

- Directorates

- Organizations

- People of NASA

- Internships

- Our History

- Doing Business with NASA

- Get Involved

- Aeronáutica

- Ciencias Terrestres

- Sistema Solar

- All NASA News

- Video Series on NASA+

- Newsletters

- Social Media

- Media Resources

- Upcoming Launches & Landings

- Virtual Events

- Sounds and Ringtones

- Interactives

- STEM Multimedia

John Bahcall

Dr. Douglas Hudgins

Sols 4164-4165: What’s Around the Ridge-bend?

Work Underway on Large Cargo Landers for NASA’s Artemis Moon Missions

NASA Open Science Initiative Expands OpenET Across Amazon Basin

NASA Motion Sickness Study Volunteers Needed!

Amendment 11: Physical Oceanography not solicited in ROSES-2024

NASA Data Helps Beavers Build Back Streams

Sols 4161-4163: Double Contact Science

Why is Methane Seeping on Mars? NASA Scientists Have New Ideas

Explore the Universe with the First E-Book from NASA’s Fermi

Hubble Captures a Bright Galactic and Stellar Duo

NASA Photographer Honored for Thrilling Inverted In-Flight Image

NASA’s Ingenuity Mars Helicopter Team Says Goodbye … for Now

NASA Langley Team to Study Weather During Eclipse Using Uncrewed Vehicles

NASA’s Near Space Network Enables PACE Climate Mission to ‘Phone Home’

Amendment 10: B.9 Heliophysics Low-Cost Access to Space Final Text and Proposal Due Date.

Students Celebrate Rockets, Environment at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center

My NASA Data Milestones: Eclipsed by the Eclipse!

Earth Day 2024: Posters and Virtual Backgrounds

First NASA Mars Analog Crew Nears End of Mission

Diez maneras en que los estudiantes pueden prepararse para ser astronautas

Astronauta de la NASA Marcos Berríos

Resultados científicos revolucionarios en la estación espacial de 2023

Voyager, nasa’s longest-lived mission, logs 45 years in space, jet propulsion laboratory, beyond expectations, the long journey, more about the mission.

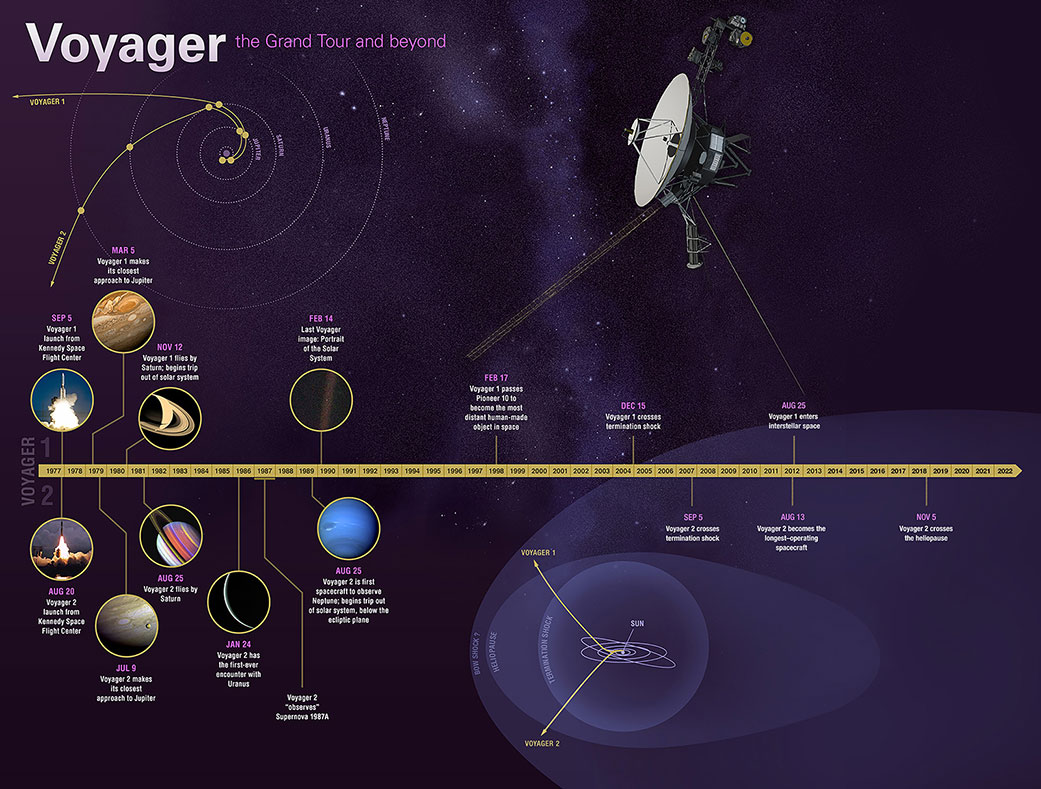

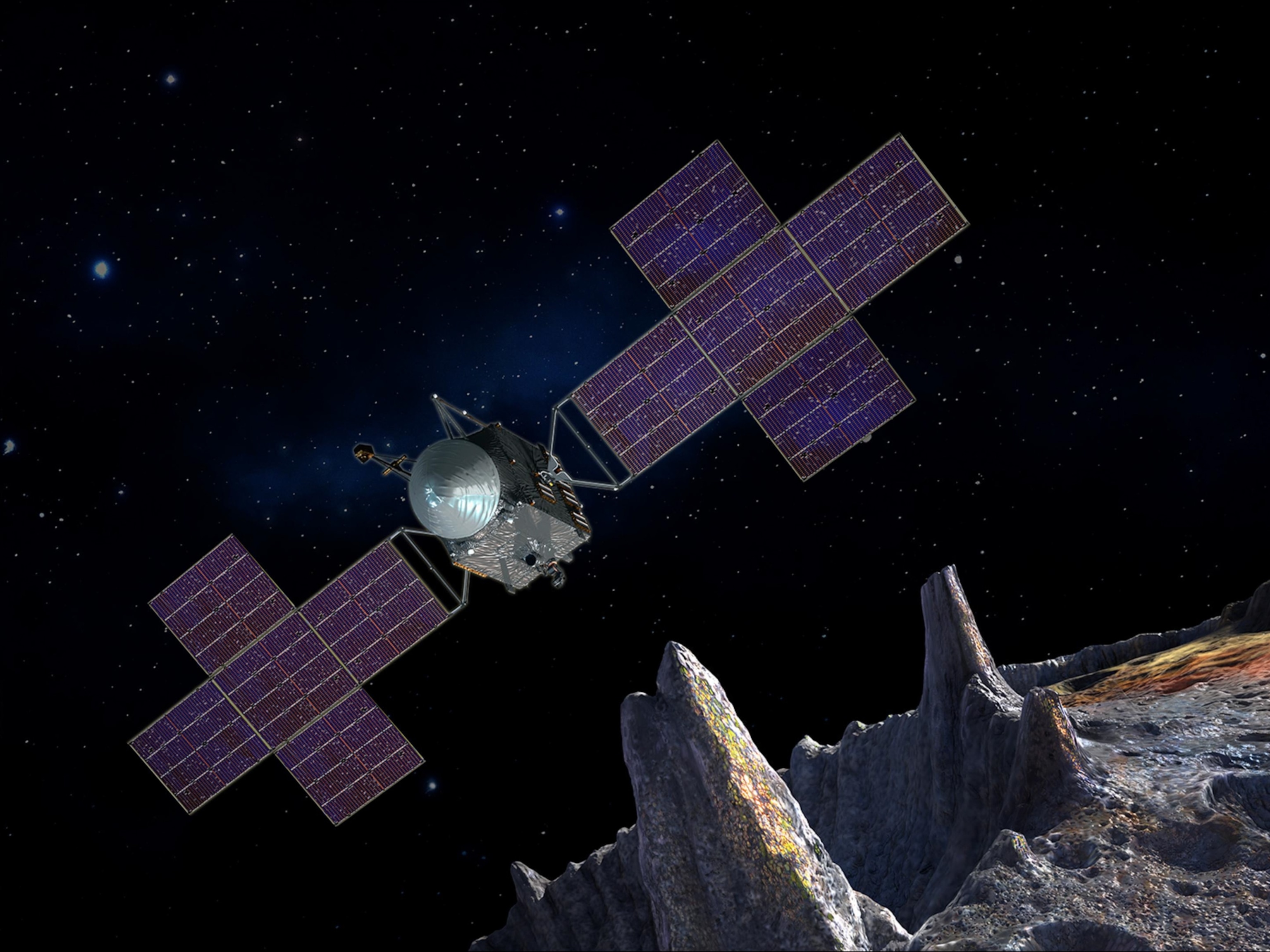

Launched in 1977, the twin Voyager probes are NASA’s longest-operating mission and the only spacecraft ever to explore interstellar space.

NASA’s twin Voyager probes have become, in some ways, time capsules of their era: They each carry an eight-track tape player for recording data, they have about 3 million times less memory than modern cellphones, and they transmit data about 38,000 times slower than a 5G internet connection.

Yet the Voyagers remain on the cutting edge of space exploration. Managed and operated by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, they are the only probes to ever explore interstellar space – the galactic ocean that our Sun and its planets travel through.

The Sun and the planets reside in the heliosphere, a protective bubble created by the Sun’s magnetic field and the outward flow of solar wind (charged particles from the Sun). Researchers – some of them younger than the two distant spacecraft – are combining Voyager’s observations with data from newer missions to get a more complete picture of our Sun and how the heliosphere interacts with interstellar space.

“The heliophysics mission fleet provides invaluable insights into our Sun, from understanding the corona or the outermost part of the Sun’s atmosphere, to examining the Sun’s impacts throughout the solar system, including here on Earth, in our atmosphere, and on into interstellar space,” said Nicola Fox, director of the Heliophysics Division at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “Over the last 45 years, the Voyager missions have been integral in providing this knowledge and have helped change our understanding of the Sun and its influence in ways no other spacecraft can.”

NASA’s Solar System Interactive lets users see where the Voyagers are right now relative to the planets, the Sun, and other spacecraft. Eyes on the Solar System . Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

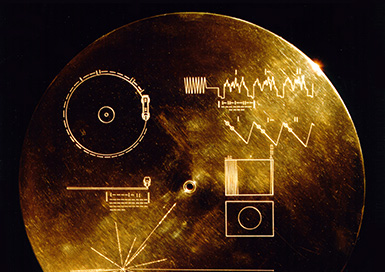

The Voyagers are also ambassadors, each carrying a golden record containing images of life on Earth, diagrams of basic scientific principles, and audio that includes sounds from nature, greetings in multiple languages, and music. The gold-coated records serve as a cosmic “message in a bottle” for anyone who might encounter the space probes. At the rate gold decays in space and is eroded by cosmic radiation, the records will last more than a billion years.

Voyager 2 launched on Aug. 20, 1977, quickly followed by Voyager 1 on Sept. 5. Both probes traveled to Jupiter and Saturn, with Voyager 1 moving faster and reaching them first. Together, the probes unveiled much about the solar system’s two largest planets and their moons. Voyager 2 also became the first and only spacecraft to fly close to Uranus (in 1986) and Neptune (in 1989), offering humanity remarkable views of – and insights into – these distant worlds.

While Voyager 2 was conducting these flybys, Voyager 1 headed toward the boundary of the heliosphere. Upon exiting it in 2012 , Voyager 1 discovered that the heliosphere blocks 70% of cosmic rays, or energetic particles created by exploding stars. Voyager 2, after completing its planetary explorations, continued to the heliosphere boundary, exiting in 2018 . The twin spacecraft’s combined data from this region has challenged previous theories about the exact shape of the heliosphere.

“Today, as both Voyagers explore interstellar space, they are providing humanity with observations of uncharted territory,” said Linda Spilker, Voyager’s deputy project scientist at JPL. “This is the first time we’ve been able to directly study how a star, our Sun, interacts with the particles and magnetic fields outside our heliosphere, helping scientists understand the local neighborhood between the stars, upending some of the theories about this region, and providing key information for future missions.”

Over the years, the Voyager team has grown accustomed to surmounting challenges that come with operating such mature spacecraft, sometimes calling upon retired colleagues for their expertise or digging through documents written decades ago.

Each Voyager is powered by a radioisotope thermoelectric generator containing plutonium, which gives off heat that is converted to electricity. As the plutonium decays, the heat output decreases and the Voyagers lose electricity. To compensate , the team turned off all nonessential systems and some once considered essential, including heaters that protect the still-operating instruments from the frigid temperatures of space. All five of the instruments that have had their heaters turned off since 2019 are still working, despite being well below the lowest temperatures they were ever tested at.

Recently, Voyager 1 began experiencing an issue that caused status information about one of its onboard systems to become garbled. Despite this, the system and spacecraft otherwise continue to operate normally, suggesting the problem is with the production of the status data, not the system itself. The probe is still sending back science observations while the engineering team tries to fix the problem or find a way to work around it.

“The Voyagers have continued to make amazing discoveries, inspiring a new generation of scientists and engineers,” said Suzanne Dodd, project manager for Voyager at JPL. “We don’t know how long the mission will continue, but we can be sure that the spacecraft will provide even more scientific surprises as they travel farther away from the Earth.”

A division of Caltech in Pasadena, JPL built and operates the Voyager spacecraft. The Voyager missions are a part of the NASA Heliophysics System Observatory, sponsored by the Heliophysics Division of the Science Mission Directorate in Washington.

For more information about the Voyager spacecraft, visit:

https://www.nasa.gov/voyager

Calla Cofield Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. 626-808-2469 [email protected]

- The Contents

- The Making of

- Where Are They Now

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Q & A with Ed Stone

golden record

Where are they now.

- frequently asked questions

- Q&A with Ed Stone

The Golden Record

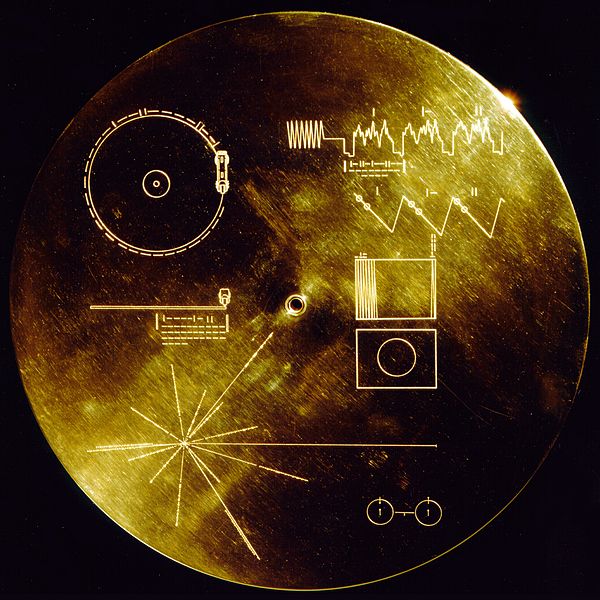

Pioneers 10 and 11, which preceded Voyager, both carried small metal plaques identifying their time and place of origin for the benefit of any other spacefarers that might find them in the distant future. With this example before them, NASA placed a more ambitious message aboard Voyager 1 and 2, a kind of time capsule, intended to communicate a story of our world to extraterrestrials. The Voyager message is carried by a phonograph record, a 12-inch gold-plated copper disk containing sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth.

Voyager 1 Sends Clear Data to NASA for the First Time in Five Months

The farthest spacecraft from Earth had been transmitting nonsense since November, but after an engineering tweak, it finally beamed back a report on its health and status

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Will-Sullivan-photo.png)

Will Sullivan

Daily Correspondent

:focal(2016x1133:2017x1134)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/32/30/3230d19e-cc50-4905-840c-7f3afeb2a0c3/e1-pia26275-voyager-copy-16.jpg)

For the first time in five months, NASA has received usable data from Voyager 1, the farthest spacecraft from Earth.

The aging probe, which has traveled more than 15 billion miles into space, stopped transmitting science and engineering data on November 14. Instead, it sent NASA a nonsensical stream of repetitive binary code . For months, the agency’s engineers undertook a slow process of trial and error, giving the spacecraft various commands and waiting to see how it responded. Thanks to some creative thinking, the team identified a broken chip on the spacecraft and relocated some of the code that was stored there, according to the agency .

NASA is now receiving data about the health and status of Voyager 1’s engineering systems. The next step is to get the spacecraft to start sending science data again.

“Today was a great day for Voyager 1,” Linda Spilker , a Voyager project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), said in a statement over the weekend, per CNN ’s Ashley Strickland. “We’re back in communication with the spacecraft. And we look forward to getting science data back.”

Hi, it's me. - V1 https://t.co/jgGFBfxIOe — NASA Voyager (@NASAVoyager) April 22, 2024

Voyager 1 and its companion, Voyager 2, separately launched from Earth in 1977. Between the two of them, the probes have studied all four giant planets in the outer solar system—Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune—along with 48 of their moons and the planets’ magnetic fields. The spacecraft observed Saturn’s rings in detail and discovered active volcanoes on Jupiter’s moon Io .

Originally designed for a five-year mission within our solar system, both probes are still operational and chugging along through space, far beyond Pluto’s orbit. In 2012, Voyager 1 became the first human-made object to reach interstellar space, the area between stars. The probe is now about eight times farther from the sun than Uranus is on average.

Over the decades, the Voyager spacecraft have transmitted data collected on their travels back to NASA scientists. But in November, Voyager 1 started sending gibberish .

Engineers determined Voyager 1’s issue was with one of three onboard computers, called the flight data system (FDS), NASA said in a December blog post . While the spacecraft was still receiving and executing commands from Earth, the FDS was not communicating properly with a subsystem called the telemetry modulation unit (TMU). The FDS collects science and engineering data and combines it into a package that the TMU transmits back to Earth.

Since Voyager 1 is so far away, testing solutions to its technical issues requires time—it takes 22.5 hours for commands to reach the probe and another 22.5 hours for Voyager 1’s response to come back.

On March 1, engineers sent a command that coaxed Voyager 1 into sending a readout of the FDS memory, NASA said in a March 13 blog post . From that readout, the team confirmed a small part—about 3 percent—of the system’s memory had been corrupted, NASA said in an April 4 update .

The core of the problem turned out to be a faulty chip hosting some software code and part of the FDS memory. NASA doesn’t know what caused the chip to stop working—it could be that a high-energy particle from space collided with it, or the chip might have just run out of steam after almost 50 years spent hurtling through the cosmos.

“It’s the most serious issue we’ve had since I’ve been the project manager, and it’s scary because you lose communication with the spacecraft,” Suzanne Dodd , Voyager project manager at JPL, told Scientific American ’s Nadia Drake in March.

To receive usable data again, the engineers needed to move the affected code somewhere else that wasn’t broken. But no single location in the FDS memory was large enough to hold all of the code, so the engineers divided it into chunks and stored it in multiple places, per NASA .

The team started with moving the code responsible for sending Voyager’s status reports, sending it to its new location in the FDS memory on April 18. They received confirmation that the strategy worked on April 20, when the first data on the spacecraft’s health since November arrived on Earth.

In the next several weeks, the team will relocate the parts of the FDS software that can start returning science data.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Will-Sullivan-photo.png)

Will Sullivan | | READ MORE

Will Sullivan is a science writer based in Washington, D.C. His work has appeared in Inside Science and NOVA Next .

Research | Science | UW and the community | UW News blog

August 23, 2017

Greetings from Earth: Documents that Changed the World podcast revisits Voyager’s ‘Golden Record,’ 1977

The Voyager spacecraft showcasing where the Golden Record is mounted. NASA/JPL

Forty years ago this month, Planet Earth said hello to the cosmos with the launch of the two Voyager probes that used gravity to swing from world to world on a grand tour of the solar system. Each bore a two-sided, 12-inch, gold-plated copper “Golden Record” of sights and sounds from Earth and its people — and a stylus to help play the record.

About 20 billion kilometers (about 12 ½ billion miles) from home now, Voyager I has since become the most distant human-made object in space. Voyager 2, in clear second place, is now about 17.2 billion kilometers away.

You could call the Golden Record a sort of intergalactic greeting card, love letter, map or time capsule — even humankind’s most epic mixtape.

“It may also be the last surviving human artifact and thus perhaps an ark,” says UW Information School associate professor Joe Janes in a new episode to his ongoing Documents that Changed the World podcast noting the Voyager anniversary.

“It’s all these things and more,” Janes adds. “Though for me the best metaphor is a message in a bottle — likely the ultimate message in a bottle.”

In the podcast series — which also became a book this year — Janes explores the origin and often evolving meaning of historical documents both famous and less-known.

In this new, Voyager-inspired episode, Janes discusses the planning and creation of the Golden Record, which was the brainchild of Carl Sagan , the world-famous Cornell University physicist who led the group that built two records and decided what information they should carry, to represent Earth to the universe.

- Fast facts about Voyager .

- Learn more about the Golden Record

- Learn about the PBS documentary “ The Farthest: Voyager in Space “

Janes is a longtime fan of Sagan and his work: “I saw Cosmos on PBS in 1980 and was hooked, both on the mysteries of the universe and our presence in it,” he says, discussing the podcast episode. “And on the whole idea of public intellectualism — that it’s OK to be smart and articulate and thoughtful and forceful, in not only educating but advocating for science and reason.”

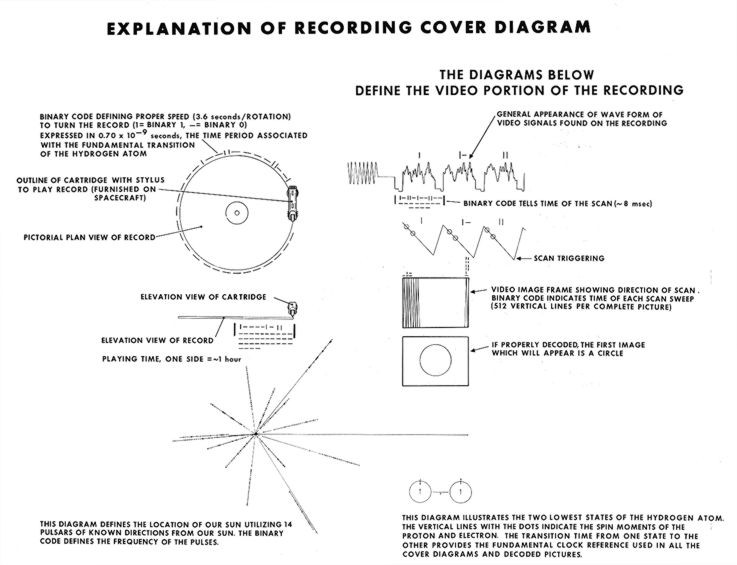

Sagan’s group, he says, decided early on that the language of science would be the best common means of communication, and so included on the records images to reflect basic scientific concepts and symbols “to establish mathematical and physical bases, then images of the sun and solar system.

“The first image, meant to help in the decoding process, is a circle, which I don’t think the designers ever fully appreciated for its beauty, simplicity and unity,” Janes says.

Music and sounds sent include Bach, gamelan music, Senegalese percussion, a Pygmy girl’s initiation song, Australian Aboriginal songs, and more. Rock and roll was represented by Chuck Berry’s guitar-fueled classic, “ Johnny B. Goode .”

The organizers were nearly all Western, Caucasian men.

“The choices they made are imperfect, as they would be in any case,” Janes says. “But they also bear the stamp of a small group of people who genuinely wanted to do well in encapsulating the human experience for anybody who might care to listen, beyond the stars or here at home.”

Even Sagan may never have dreamed that the records would really find aliens. But we can hope. And as Janes says in the podcast, “Bound up in the attempt is one of the most basic of human desires — to be remembered and understood.”

The Voyager spacecraft, not aimed at anything in particular now, continue to speed away from Earth at about 40,000 miles per hour.

And so the Golden Records take their place among Janes’ Documents that Changed the World.

Will they go on to become documents that change other worlds?

Only time — “ billions and billions of years,” as Sagan might have said — will tell.

For more information about Janes or his work, contact him at [email protected] .

- Learn more about the Golden Records .

UW News Blog

Read more from the UW News Blog

Search UW News

Artificial intelligence, flooding and landslides, latest news releases.

10 hours ago

11 hours ago

UW Today Newsletter

UW Today Daily

UW Today Week in Review

For UW employees

Be boundless, connect with us:.

© 2024 University of Washington | Seattle, WA

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Voyager 1 transmitting data again after Nasa remotely fixes 46-year-old probe

Engineers spent months working to repair link with Earth’s most distant spacecraft, says space agency

Earth’s most distant spacecraft, Voyager 1, has started communicating properly again with Nasa after engineers worked for months to remotely fix the 46-year-old probe.

Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), which makes and operates the agency’s robotic spacecraft, said in December that the probe – more than 15bn miles (24bn kilometres) away – was sending gibberish code back to Earth.

In an update released on Monday , JPL announced the mission team had managed “after some inventive sleuthing” to receive usable data about the health and status of Voyager 1’s engineering systems. “The next step is to enable the spacecraft to begin returning science data again,” JPL said. Despite the fault, Voyager 1 had operated normally throughout, it added.

Launched in 1977, Voyager 1 was designed with the primary goal of conducting close-up studies of Jupiter and Saturn in a five-year mission. However, its journey continued and the spacecraft is now approaching a half-century in operation.

Voyager 1 crossed into interstellar space in August 2012, making it the first human-made object to venture out of the solar system. It is currently travelling at 37,800mph (60,821km/h).

Hi, it's me. - V1 https://t.co/jgGFBfxIOe — NASA Voyager (@NASAVoyager) April 22, 2024

The recent problem was related to one of the spacecraft’s three onboard computers, which are responsible for packaging the science and engineering data before it is sent to Earth. Unable to repair a broken chip, the JPL team decided to move the corrupted code elsewhere, a tricky job considering the old technology.

The computers on Voyager 1 and its sister probe, Voyager 2, have less than 70 kilobytes of memory in total – the equivalent of a low-resolution computer image. They use old-fashioned digital tape to record data.

The fix was transmitted from Earth on 18 April but it took two days to assess if it had been successful as a radio signal takes about 22 and a half hours to reach Voyager 1 and another 22 and a half hours for a response to come back to Earth. “When the mission flight team heard back from the spacecraft on 20 April, they saw that the modification worked,” JPL said.

Alongside its announcement, JPL posted a photo of members of the Voyager flight team cheering and clapping in a conference room after receiving usable data again, with laptops, notebooks and doughnuts on the table in front of them.

The Retired Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield, who flew two space shuttle missions and acted as commander of the International Space Station, compared the JPL mission to long-distance maintenance on a vintage car.

“Imagine a computer chip fails in your 1977 vehicle. Now imagine it’s in interstellar space, 15bn miles away,” Hadfield wrote on X . “Nasa’s Voyager probe just got fixed by this team of brilliant software mechanics.

Voyager 1 and 2 have made numerous scientific discoveries , including taking detailed recordings of Saturn and revealing that Jupiter also has rings, as well as active volcanism on one of its moons, Io. The probes later discovered 23 new moons around the outer planets.

As their trajectory takes them so far from the sun, the Voyager probes are unable to use solar panels, instead converting the heat produced from the natural radioactive decay of plutonium into electricity to power the spacecraft’s systems.

Nasa hopes to continue to collect data from the two Voyager spacecraft for several more years but engineers expect the probes will be too far out of range to communicate in about a decade, depending on how much power they can generate. Voyager 2 is slightly behind its twin and is moving slightly slower.

In roughly 40,000 years, the probes will pass relatively close, in astronomical terms, to two stars. Voyager 1 will come within 1.7 light years of a star in the constellation Ursa Minor, while Voyager 2 will come within a similar distance of a star called Ross 248 in the constellation of Andromeda.

Cosmic cleaners: the scientists scouring English cathedral roofs for space dust

Russia acknowledges continuing air leak from its segment of space station

Uncontrolled European satellite falls to Earth after 30 years in orbit

Cosmonaut Oleg Kononenko sets world record for most time spent in space

‘Old smokers’: astronomers discover giant ancient stars in Milky Way

Nasa postpones plans to send humans to moon

What happened to the Peregrine lander and what does it mean for moon missions?

Peregrine 1 has ‘no chance’ of landing on moon due to fuel leak

Most viewed.

Contact restored with NASA’s Voyager 1 space probe

Contact restored.

That was the message relieved NASA officials shared after the agency regained full contact with the Voyager 1 space probe, the most distant human-made object in the universe, scientists have announced.

For the first time since November, the spacecraft is returning usable data about the health and status of its onboard engineering systems, NASA said in a news release Monday.

The 46-year-old pioneering probe, now 15.1 billion miles from Earth, has continually defied expectations for its life span as it ventures farther into the uncharted territory of the cosmos .

More: Voyager 1 is 15 billion miles from home and broken. Here's how NASA is trying to fix it.

Computer experts to the rescue

It wasn't as easy as hitting Control-Alt-Delete, but top experts at NASA and CalTech were able to fix the balky, ancient computer on board the probe that was causing the communication breakdown – at least for now.

A computer problem aboard Voyager 1 on Nov. 14, 2023, corrupted the stream of science and engineering data the craft sent to Earth, making it unreadable .

Although the radio signal from the spacecraft had never ceased its connection to ground control operators on Earth, that signal had not carried any usable data since November, NASA said. After some serious sleuthing to fix the onboard computer, that changed on April 20, when NASA finally received usable data.

In interstellar space

The probe and its twin, Voyager 2, are the only spacecraft to ever fly in interstellar space (the space between the stars).

Voyager 2 continues to operate normally, NASA reports. Launched more than 46 years ago , the twin spacecraft are standouts on two fronts: they've operated the longest and traveled the farthest of any spacecraft ever.

Before the start of their interstellar exploration, both probes flew by Saturn and Jupiter, and Voyager 2 flew by Uranus and Neptune.

More: NASA gave Voyager 1 a 'poke' amid communication woes. Here's why the response was encouraging.

They were designed to last five years but have become the longest-operating spacecraft in history. Both carry gold-plated copper discs containing sounds and images from Earth, content that was chosen by a team headed by celebrity astronomer Carl Sagan .

For perspective, it was the summer of 1977 when the Voyager probes left Earth. "Star Wars" was No. 1 at the box office, Jimmy Carter was in the first year of his presidency, and Elvis Presley had just died.

Contributing: Eric Lagatta and George Petras

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

40 Years Ago, NASA Launched Message To Aliens Into Deep Space

Christopher Joyce

Forty years ago, NASA launched two Voyager spacecraft into deep space. Onboard both were gold discs with music, greetings and sounds from Earth — a message to aliens. Ann Druyan, the creative director of the project, talks about how they decided what message to put in the interstellar bottle.

AUDIE CORNISH, HOST:

Forty years ago this month, NASA launched the Voyager 2 spacecraft. Its mission was to explore space, and it carried audio greetings, music, animal sounds and images of people and our planet. NPR's Christopher Joyce spoke with Ann Druyan, one of the creators of this interstellar message, about how it was put together.

CHRISTOPHER JOYCE, BYLINE: The message was astronomer Carl Sagan's idea. Let's send a pocket history of us into space. If there's life out there, maybe they'll find it. There would be images, equations, solar system maps as well as sounds on a phonograph record - after all, this was the 1970s - a record made of gold. Sagan asked Ann Druyan to be the creative director of the project.

ANN DRUYAN: When he told me about the record, he said, and we're going to have greetings in all these human languages. And I looked at him, and I said, just human languages? How do you know that those are going to be the ones that are most open to interpretation? And he just gave me this look, and I knew that he and I were completely on the same wavelength.

JOYCE: So there were animal sounds - whales, for example...

(SOUNDBITE OF WHALE SONG)

JOYCE: ...And a chimpanzee.

(SOUNDBITE OF CHIMPANZEE SCREECH)

DRUYAN: So it was a kind of enthusiastic collaboration with people yelling out the names of different animals and languages and buildings and all of - and pieces of music of course - all of those possibilities.

JOYCE: Druyan wanted Beethoven, but she also wanted to rock 'n' roll.

DRUYAN: I wanted it to be by one of the geniuses and progenitors of rock 'n' roll, one of the inventors. And I felt it should be Chuck Berry.

JOYCE: Sagan didn't like rock and roll.

(SOUNDBITE OF CHUCK BERRY SONG, "JOHNNY B. GOODE")

JOYCE: But Chuck Berry's classic song "Johnny B. Goode" made the cut.

JOYCE: The team had other disagreements. They debated whether to show humanity's ugly side - Auschwitz, the Cambodian genocide. Sagan argued against it.

DRUYAN: He was concerned that it would be misconstrued as a threat. And he wasn't really certain that it would be understood for what it was - an expression of failure and regret on our part.

JOYCE: Instead, the recording features friendly greetings in numerous languages, such as one in the Amoy dialect of southern China.

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN: (Speaking Amoynese).

JOYCE: Friends of space, how are you all? Have you eaten yet? Come visit us if you have time. Visiting Earth to eat actually worries critics of interstellar outreach. Advertising our location could be a recipe, quite literally, for disaster. Druyan is having none of it.

DRUYAN: You know, the idea of, like, don't tell them where we are 'cause they'll come and eat us for lunch - if you're traveling in space, then you probably also figured out how to get lunch without traveling the astonishing distances between the stars.

JOYCE: Druyan says one of her fondest memories came 12 years after the 1977 launch of the two spacecraft. There was a big party at NASA's Jet Propulsion Lab in California. She and Sagan arrived late with a surprise guest - Chuck Berry.

DRUYAN: All of a sudden, Chuck Berry came out in his white suit, and the opening chords of "Johnny B. Goode" echoed through the night. And the hundreds of scientists and engineers who'd been involved, technicians, everyone and their families were rocking out that night.

JOYCE: The two Voyagers are now billions and billions of miles from Earth. Any time now, we could be getting a message back from space. Hey, Earthlings, take me to "Johnny B. Goode." Christopher Joyce, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "JOHNNY B. GOODE")

CHUCK BERRY: (Singing) Where lived a country boy named Johnny B. Goode who never ever learned to read or write...

Copyright © 2017 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

- Share full article

The Loyal Engineers Steering NASA’s Voyager Probes Across the Universe

As the Voyager mission is winding down, so, too, are the careers of the aging explorers who expanded our sense of home in the galaxy.

Larry Zottarelli, who recently retired from the Voyager flight crew. Credit... Graeme Mitchell for The New York Times

Supported by

By Kim Tingley

- Aug. 3, 2017

I n the early spring of 1977, Larry Zottarelli, a 40-year-old computer engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, set out for Cape Canaveral, Fla., in his Toyota Corolla. A Los Angeles native, he had never ventured as far as Tijuana, but he had a per diem, and he liked to drive. Just east of Orlando, a causeway carried him over the Indian and Banana Rivers to a triangular spit of sand jutting into the Atlantic, where the Air Force keeps a base. His journey terminated at a cavernous military hangar.

A fleet of JPL trucks made the trip under armored guard to the same destination. Their cargo was unwrapped inside the hangar high bay, a gleaming silo stocked with tool racks and ladder trucks. Engineers began to assemble the various pieces. Gradually, two identical spacecraft took shape. They were dubbed Voyager I and II, and their mission was to make the first color photographs and close-up measurements of Jupiter, Saturn and their moons. Then, if all went well, they might press onward — into uncharted territory.

It took six months, working in shifts around the clock, for the NASA crew to reassemble and test the spacecraft. As the first launch date, Aug. 20, drew near, they folded the camera and instrument boom down against the spacecraft’s spindly body like a bird’s wing; gingerly they pushed it, satellite dish first, up inside a metal capsule hanging from the high bay ceiling. Once ‘‘mated,’’ the capsule and its cargo — a probe no bigger than a Volkswagen Beetle that, along with its twin, had nevertheless taken 1,500 engineers five years and more than $200 million to build — were towed to the launchpad.

By T-minus two hours, a select few engineers, too nervous to sit down, stood at computers outside the high bay, overseeing the spacecraft telemetry. Elsewhere in the hangar, scientists, NASA brass from Washington and several dozen ‘‘nonessential’’ engineers — Zottarelli among them — huddled around TV monitors. At T-minus 30 seconds, the spacecraft’s engines roared to life, and many of the nonessentials took off running out of the room and toward the exit — ‘‘seven, six, five.’’ They burst out into the morning. Shielding their eyes, they peered across a flat expanse at smoke billowing on the horizon. Slowly and silently, the capsule rose out of the cloud, its rockets trailing flames. In an instant, there came a terrific boom as the sound waves from blastoff hit the hangar like a gong, ringing it as the spacecraft disappeared.

Two weeks later, after the second launch, everyone headed home. The show was over — both spacecraft were performing flawlessly — but behind the scenes, the mission, on a tight budget, lagged in hiring the more than 200 computer engineers needed to shepherd the spacecraft through a planetary encounter. Many of those on the flight team were fresh out of college, running the most sophisticated electronics systems in the world. They had barely had a chance to jell, when, in April 1978, not yet halfway to Jupiter, Voyager 1 experienced a problem. Its scan platform, where the cameras and instruments are mounted, got stuck.

As the engineers scrambled to figure out what they could do from more than 100 million miles away, someone forgot to send a weekly command to reset a timer on the other spacecraft. When it ran down without hearing from Earth, it triggered so-called fault-protection software, 600 lines of code that respond to malfunctions automatically. In this instance, fault protection assumed the radio receiver was broken and switched to the backup. On the mission-control monitors in a situation like this, the crawl of numbers reporting the status of the receivers would have turned crimson: a ‘‘red alarm.’’

Voyager’s 40th Anniversary

Long after they have stopped communicating with earth, the twin voyager spacecraft will forever drift among the stars..

Forty years ago, in August and September of 1977, a band of humans launched a pair of robots to explore the solar system and probe the infinite darkness beyond. “3, 2, 1. We have ignition and we have liftoff!” Taking advantage of a rare planetary alignment, the twin Voyager spacecraft raced outward toward Jupiter, then used the giant planet’s gravity to slingshot on to Saturn. At Saturn they parted company. Voyager 1 turned upward, leaving the plane of the planets and heading toward interstellar space. But Voyager 2 kept trekking, spiraling outward on a grand tour of the outer planets, toward distant Uranus and Neptune. At each planetfall, fuzzy dots bloomed into worlds. Every image sent back to Earth was another lesson on nature’s ability to surprise. Voyager saw swirls within swirls in Jupiter’s banded jet streams. Volcanoes spouting sulphur on Jupiter’s moon Io, a tormented world twisted and pulled by gravity. And eggshell-smooth Europa, an icy shell around a hidden ocean. Two years after Jupiter, the Voyagers approached Saturn, jewel of the solar system. Its broad rings dissolved into thousands of grooves, like a phonograph record. Braided, kinked and patrolled by tiny moonlets. Voyager probed the methane skies of Titan. It slid past two-faced Iapetus, with light and dark sides. Giovanni Cassini’s disappearing moon. And Enceladus. Trapped under its crust of ice is another dark ocean, and perhaps living creatures. After Saturn, Voyager 1 turned away from the planets but Voyager 2 sailed on. Voyager found ghostly Uranus tipped on its side, its south pole facing the sun. A blue-green bulls eye with faint rings. Voyager slipped passed methane-blue Neptune, a pacific-looking world bruised with dark, violent hurricanes. Antennas on Earth strained to hear the trickle of data from almost 3 billion miles out. Voyager 2’s last port of call was Triton, Neptune’s biggest moon. A mottled ball of exotic ices, plumed with dark geysers of nitrogen. One final world added to Voyager’s tally. But the Voyager mission was not only to observe. Each spacecraft carried a message. A gold record, with a needle and instructions on how to play it. A time capsule from the 1970s, grooved with the sights and sounds of Earth. “I send greetings on behalf of the people of our planet. We step out of our solar system, into the universe, seeking only peace and friendship, to teach if we are called upon, to be taught if we are fortunate.” Of all the voices ever recorded, of all the photographs ever taken, these few will survive the end of our planet. Scratches on gold, adrift in the void. A time capsule from the 1970s, grooved with the sights and sounds of Earth. Of all the voices ever recorded, of all the photographs ever taken, these few will survive the end of our planet. Scratches on gold, adrift in the void. As Voyager 1 climbed away from the planets, it turned its cameras backward. To snap a family portrait of the worlds it was leaving behind forever. The Earth appears as a bright pixel in a wash of scattered sunlight. A “Pale Blue Dot” in the words of astronomer and cosmic sage, Carl Sagan: “Consider again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. ... The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena.” No other spacecraft have gone so far, or explored so many new worlds. In the fullness of galactic time the Voyagers might yet be found, but by then the human race could be long extinct. Long after they have ceased speaking to us, the twins will forever drift among the stars. Mute, but carrying sounds and greetings from home. “Hello from the children of Planet Earth” The last lonely evidence that we too once lived in this starry realm, on an island of ice and rock. As Carl Sagan put it: “A dust mote in a sunbeam.”

Realizing their mistake, the engineers tried to stop the fault-protection routine, but the newly awakened backup receiver would not register their command. Helpless, they waited for the spacecraft to reason its way back to the original receiver; when it did, and the command went through normally, they were giddy with relief. They were still high-fiving when the working receiver shorted out like a blown fuse. Now it really was dead.

Fortunately, the malfunctioning backup receiver was still drawing current. They guessed that its oscillator, which allows it to accept a wide range of frequencies, had quit, essentially shrinking the target for transmissions from Earth. Assuming a much narrower bandwidth, and manually subtracting the Doppler effect, they recalibrated their signal. It worked — but to this day, the same calculation must precede every command. The original receiver remains useless: one engineer’s simple oversight nearly doomed humankind’s lone visit to Uranus and Neptune . ‘‘You like to think you have checks and balances,’’ Chris Jones, JPL’s chief engineer, who designed Voyager’s fault protection, told me. ‘‘In reality, we all worry about being that person.’’

Today the Voyagers are 10 billion and 13 billion miles away, the farthest man-made objects from Earth. The 40th anniversary of their launch will be celebrated next month. We tend to think of space as vacant, but it is actually matter, created, as everything in the universe is, by the explosions of ancient stars. Within our planetary neighborhood, this ‘‘space’’ is made up of different particles than the space outside is, because of supersonic wind that blows out from the surface of our sun at a million miles per hour. The wind generates a bubble around our solar system called the heliosphere. Five years ago, Voyager 1 reached the boundary where the heliosphere gives way to interstellar space, a region as novel to us — and potentially relevant — as the Pacific was to Europeans 500 years ago. The data the probes are collecting are challenging fundamental physics and will provide clues to the biggest of questions: Why did our sun give birth to life only here? Where else, within our solar system or others, are we most likely to find evidence that we are not alone?

The mission quite possibly represents the end of an era of space exploration in which the main goal is observation rather than commercialization. In internal memos, Trump-administration advisers have referred to NASA’s traditional contractors as ‘‘Old Space’’ and proposed refocusing its budget on supporting the growth of the private ‘‘New Space’’ industry, Politico reported in February. ‘‘Economic development of space’’ will begin in near-Earth orbit and on the moon, according to the president’s transition team, with ‘‘private lunar landers staking out de facto ‘property rights’ for Americans on the moon, by 2020.’’

All explorations demand sacrifices in exchange for uncertain outcomes. Some of those sacrifices are social: how many resources we collectively devote to a given pursuit of knowledge. But another portion is borne by the explorer alone, who used to be rewarded with adventure and fame if not fortune. For the foreseeable future, Voyager seems destined to remain in the running for the title of Mankind’s Greatest Journey, which might just make its nine flight-team engineers — most of whom have been with the mission since the Reagan administration — our greatest living explorers. They also may be the last people left on the planet who can operate the spacecraft’s onboard computers, which have 235,000 times less memory and 175,000 times less speed than a 16-gigabyte smartphone. And while it’s true that these pioneers haven’t gone anywhere themselves, they are arguably every bit as dauntless as more celebrated predecessors. Magellan never had to steer a vessel from the confines of a dun-colored rental office, let alone stay at the helm long enough to qualify for a senior discount at the McDonald’s next door.

Their fluency in archaic programming languages will become only more crucial as the years go on, because even as the probes harvest priceless information from the cosmos, they are running out of fuel. (Decaying plutonium supplies their power.) By 2030 at the latest, they will not have enough juice left to run a single experiment. And even that best case comes with a major caveat: that the flight-team members forgo retirement to squeeze the most out of every last watt.

One of the greatest obstacles to planetary science has always been the human life span: Typically, for instance, a direct flight to Neptune would take about 30 years. But in the spring of 1965, Gary Flandro, a doctoral student at Caltech, noticed that all four outer planets — Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune — would align on the same side of the sun in the 1980s. If a spacecraft were launched in the mid- to late 1970s, it could use the gravity of the first body to slingshot to the second, and so on. Such a trajectory would add enough speed to shorten the total journey by almost two-thirds. What’s more, this orbital configuration would not appear again for 175 years.

The Voyagers carried cameras and instruments for analyzing atmospheric temperatures, moon masses, gravitational and magnetic fields and radiation levels. Reaching Jupiter in 1979, they captured images of lightning in its cloud tops and astounded scientists — who had assumed all moons were as barren as our own — with pictures of eight active volcanoes on its satellite Io; Europa, another Jovian moon, was encased in a shell of water ice, cracked in places by what appeared to be the tides of an ocean below. The photographs revealed themselves on control-room monitors pixel by pixel, row by row. ‘‘I would be sitting in here at night sometimes when the Voyager mission was flying,’’ Esker Davis, project manager for the Saturn encounter, told David W. Swift, who published an oral history of the mission in 1997, after Davis’s death. ‘‘And my wife would call up and ask what I was doing. I said, ‘Just watching pictures come in, being the first person to see this picture.’ ’’

The mission would have ended there, but President Ronald Reagan bestowed an extension, possibly swayed by the real-time briefings hosted by Ed Stone, the project’s lead scientist, on the occasion of every planetary encounter. Hundreds of reporters, as well as politicians and celebrities, attended, packing into a cramped JPL auditorium for the debuts of Uranus in 1986 and Neptune in 1989.

The final flyby, of Neptune’s moon Triton, took place on a hot August night. Afterward, everyone celebrated with Champagne, cold cuts and drunken singing; on the JPL lawn, Chuck Berry performed ‘‘Johnny B. Goode,’’ one of the tracks included on gold-plated records of human sights and sounds attached to the spacecraft for any intelligent life that might find them. Then, gradually, the hallways grew quiet. Stone and his colleagues moved on to new projects while analyzing Voyager data part time; the flight team laid off 150 engineers (many of whom went on to staff subsequent missions). The probes’ new goal was to reach interstellar space. But though scientists had measured the speed of the solar wind that forms the heliosphere, the properties of the matter beyond it had never been analyzed. How much pressure it exerted on the bubble, and thus the size of the bubble, were a mystery. So, too, was how long — years? decades? — it might take a craft to escape it.

At the mission’s outset, the flight-team members were mischievous kids. They relieved stress with games and pranks: bowling in the hallway, using soda cans as pins; filling desk drawers with plastic bags of live goldfish; making scientists compete in disco-pose contests. Now, by 1990, they were older, with kids of their own. They had experienced the deaths of colleagues and watched others’ marriages falter as a result of long hours at the lab. With no planets to explore, they spent the decade doing routine spacecraft maintenance with a fraction of their bygone manpower. Six of the current nine engineers were on the team then. Sun Kang Matsumoto, who joined the mission in ’85, studied so diligently to master the new roles pressed upon her that her sons learned the spacecraft contours by osmosis. When her eldest was 8, he surprised her with a perfect Lego model; now in college, ‘‘he calls and asks, ‘How is Voyager?’ Like, ‘How is Grandma?’ ’’ Matsumoto says.

The mission originally occupied three floors of Building 264 on the JPL campus, home to many of the lab’s highest-profile projects. But soon after Neptune, says Jefferson Hall, who joined the project in 1978, ‘‘we were booted out.’’ Their first move was into the former offices of a mainframe-computer company in Sierra Madre. In 2002, after more staff cuts, they moved to a rental suite in Altadena. NASA reviewed the mission to determine if it should be canceled altogether.

The scientists’ models, meanwhile, began to reveal subtle changes in the raw data. By late 2004, it was clear that Voyager 1’s magnetometer had detected an abrupt increase in the strength of the surrounding magnetic field, suggesting the probe had entered the outermost layer of the heliospheric bubble, the ‘‘heliosheath.’’ This is where the solar wind ions abruptly slow as they press outward against the surrounding interstellar matter and swerve to create a cometlike tail. A wind of interstellar ions flows around the outside of the bubble like water around the bow of a ship. Finally, on Aug. 25, 2012, the density of particles around the spacecraft precipitously increased, as though it had plunged from sky to sea. It had crossed the threshold of interstellar space.

I n 2016, the year he turned 80, Zottarelli, the flight team’s most experienced programmer, gave six months’ notice and spent the time training a successor. None of the other engineers, only one of whom is under 50, have a replacement in waiting in the event that they abdicate more suddenly. Unlike the astrophysicists who devise experiments for Voyager and who interpret the results, the core flight-team members don’t have the luxury of being able to work simultaneously on other missions. Over decades, the crew members who have remained have forgone promotions, the lure of nearby Silicon Valley and, more recently, retirement, to stay with the spacecraft. NASA funding, which peaked during the Apollo program in the 1960s, has dwindled, making it next to impossible to recruit young computer-science majors away from the likes of Google and Facebook.

Last autumn, I drove through the San Gabriel Valley to a squat concrete building beside Scott-Fox Puppy Preschool. Suzanne Dodd, 56, the mission’s project manager, answered the door. She wore red-framed glasses over sharp blue eyes, and her fair hair was cut short. She escorted me past the vestibule to a common room ringed by office doors. Hanging over the cubicle partitions in the center was a shingle that read ‘‘Mission Control.’’

‘‘You can see where we are in the culture,’’ she said, with a mild sweep of her palm. Voyager was her first job. She pointed out a used microfiche reader that Tom Weeks, a hardware engineer and the self-described mission librarian, purchased on eBay to read old diagnostics reports. To conserve power on the spacecraft, the engineers must decide what to turn off when, and for how long — which means estimating how cold they can let each component get. (On Voyager 2, because of the broken oscillator, any change in temperature also tweaks the receiver frequency.) Turning the heaters off for a while is the safest way to get enough power to run the instruments, but the lower the overall wattage drops, the faster parts will freeze. One of the team’s most valuable insights so far: Spinning the wheels of an eight-track tape recorder — the spacecrafts’ only data-storage option — generates a bit of additional heat.

Enrique Medina, the power subsystem expert, was preparing to implement a ‘‘patch,’’ an update that would turn off a heater on Voyager 2 in order to run the gyroscope, roll the spacecraft and calibrate the magnetometer. Even though they simulate every patch with software, there is plenty of room for human error. Far more often, hardware fails for no evident reason. In 1998, Voyager 2 reacted to a command by going silent. For 64 hours straight, the flight team studied the specific instruction — consisting of 18 bits, or 1s and 0s — that preceded the blackout. Bits have been known to ‘‘flip’’ to the opposite value, changing the instruction the same way that swapping a single letter turns ‘‘cat’’ into ‘‘cut.’’ The question was: What instruction had they accidentally given and how could they undo it? At last, modeling the outcome of each possible bit, they discovered one that turned off the exciter, which generates the spacecraft’s radio signal; when they turned it back on, the transmissions resumed. A similar scare took place in 2010, when a bit involved in formatting telemetry flipped, turning the transmissions to gibberish. ‘‘A lot of our anomalies we’ve come up with workarounds for, and at the time we didn’t know why it happened,’’ Weeks explained. Dodd added, ‘‘The No. 1 rule with spacecraft is: Don’t change it if you don’t have to.’’

In the mission-control cubby, Medina, who is 68 and a grandfather of four, with a husky voice and a Tom Selleck mustache, rolled a chair over to two pairs of monitors labeled with construction-paper signs that read: ‘‘Voyager Mission Control Hardware, PLEASE DO NOT TOUCH.’’ He jiggled a mouse, and one of the screens woke to a stream of numbers and letters describing the health of Voyager 1.

Because they have only four kilobytes of computer storage, the spacecraft transmit data 24/7, but the radio signals take 19 hours and 12 hours to reach Earth. The three antenna dishes big enough to register them are shared, so Voyager gets only four to six hours of reception time per spacecraft per day; outside these often odd windows, their data dissipate into the ether. Medina gestured to another computer in the corner that monitors the telemetry that comes in when the office is empty and, if it detects an anomaly, phones an on-call engineer: the Voyager Alarm Monitor Processor Including Remote Examination tool. ‘‘We call it Vampire,’’ Medina said, ‘‘because it works in the middle of the night.’’

In March 2014, after news broke that Voyager 1 had crossed into interstellar space, I spoke with Medina over the phone. ‘‘I would not leave my wife to go with Angelina Jolie, as exciting as that sounds,’’ he told me. ‘‘And I would not leave Voyager to go to the new Mars missions. I will not leave Voyager until it ceases to exist. Or until I cease to exist.’’

A ll the billions of stars in the universe, hosts to billions of planets, have a heliosphere. Understanding the properties of our own will help us interpret observations of those systems. Voyager 1 has shown that it blocks 75 percent of cosmic radiation, which at extreme levels is toxic to life as we know it. This is not a static number: Our sun is orbiting the galaxy at 125 miles per second; its interstellar environment — and thus the size and shape of its heliosphere — is constantly in flux.

‘‘If the pressure outside got high enough, and there are some areas in the Milky Way galaxy where it would be high enough, it could compress the heliosphere down to where in fact the boundary is almost to where we are. And that would change the radiation environment of the planets, which is important when you want to try to understand anything about the origin of life,’’ Ed Stone, the science-team leader, told me when I visited him at Caltech last fall. ‘‘Here on Earth, wherever there’s liquid water, whether it’s boiling water coming out of the vents or frozen water, there are microbes there. So life is remarkably robust where there’s water.’’

He went on: ‘‘I think that one of the biggest questions is, Can we find a spot here in the solar system where there’s microbial life? If there’s no microbial life anywhere else, that would be surprising, given here on Earth it appeared fairly quickly after the end of the bombardment,’’ an epic rain of asteroids some four billion years ago. ‘‘If one could ever find some evidence of it here in the solar system where we could get a sample, then one could look at the DNA. All life on Earth has a related DNA. Is that true for everywhere? Either answer would be amazing. Either there’s only one way that life evolves, or no, there’s more than one way.’’

In his office, Stone stood on tiptoe to lift an intricate model of Voyager from the top of a bookcase. At 81, he moves more stiffly than the Stone of NASA archival footage. Otherwise, he is remarkably unchanged. On a bulletin board behind his computer, he pins the latest graphs of the rate of charged particles that each spacecraft has detected. A drastic dip in low-energy ones is what convinced him that Voyager 1 had exited the heliosphere, and he is eager for Voyager 2, which entered the heliosheath from a different angle in 2007, to see a comparable drop before it goes quiet.

‘‘When we started this, I realized we were on a mission of discovery,’’ he said. ‘‘I just had no idea how much discovery there was going to be. And I certainly had no idea that it would last as long as it has.’’ After we lose contact with them, the spacecraft will continue to orbit the galaxy for billions of years, never striking another star. ‘‘Space,’’ Stone said, ‘‘is really empty.’’

Astrophysicists who study the heliosphere wage a constant battle against apathy when it comes to invisible substances nearly 100 times farther away from us than the sun is. ‘‘I hear a lot of people saying, ‘So what?’ I try to explain: ‘It’s like your home,’ ’’ Merav Opher, a professor of astrophysics at Boston University and a member of the Voyager science team, told me. ‘‘You just found out the walls aren’t walls. They’re porous. I think it’s existential.’’ In 2006, Opher and Stone published a landmark paper in The Astrophysical Journal predicting that Voyager 2 would encounter the heliosphere boundary closer to the sun than its twin had, pointing to a startling contradiction: The heliosphere must be asymmetrical; it is not a ‘‘sphere’’ after all.

There is passionate disagreement about what its exact shape is. (The Voyager scientists argue over practically every scrap of data; a few holdouts insist that Voyager 1 has yet to reach interstellar space.) In 1961, Eugene Parker, the renowned astrophysicist who first predicted the existence of a heliosphere, hypothesized that it might look like a comet — compressed in front with a tail in back. Earlier this year, Tom Krimigis, the emeritus head of the Space Department at the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University and the principal investigator for Voyager’s Low-Energy Charged Particle Experiment, published a paper in Nature Astronomy showing that the heliosphere has a very short tail and ‘‘kind of moves through space like a clenched fist.’’ His instrument has also shown that cosmic rays — expected to flow toward the heliosphere uniformly from across interstellar space — actually move quite differently depending on their orientation to the interstellar magnetic field. ‘‘Every once in a while, a tsunami passes Voyager,’’ Krimigis told me, referring to these waves. ‘‘The galaxy was supposed to be a calm sea, and that’s not what we find.’’

Opher believes that the influence of the sun’s magnetic field may warp the heliosphere into the shape of a ‘‘croissant.’’ At its plump center, interstellar matter presses in closer than previously thought — which would mean we are less isolated from the rest of the galaxy than we believe.

Last Sept. 29, a Thursday, Larry Zottarelli awoke before 7, as he did most weekdays, and dressed quietly so as not to disturb his sleeping wife. He raked a comb through his silver hair, donned trifocals and a calculator watch and drove to the office. He brewed his first mug of coffee in the efficiency kitchen and carried it to his desk. He’d been on the job for 40 years; the next day would be his last. A printed-out email taped to his computer hutch had instructions for handing in his badge and parking pass and collecting his final paycheck. He had cleared out most of his belongings, except two gallon-size Ziploc bags, in which he had sealed the plastic arms of his office chair to protect them from disintegrating under the daily weight of his elbows. Sitting facing the door, backed by a windowless, conch-pink brick wall, he brought to mind a hermit crab wearing a seashell.

Later that morning, when Zottarelli entered the conference room to attend his last daily flight-team briefing, his colleague Adans Ko, 58, was arranging takeout containers of dim sum on the table for a celebration. He threw an arm around his shoulders and said, ‘‘Larry is going to give me a kiss today!’’ Matsumoto, who was holding a camera, said, ‘‘O.K., look at me.’’ She was making a photo album for him. When the party broke up, I found Zottarelli’s replacement, Lu Yang, at her desk. I asked her if he had given her any specific advice. ‘‘Whatever the problem, you go there and solve it,’’ she said, and laughed.

In retirement, Zottarelli told me, he would like to see Florida again. He wonders how it has changed. In his garage is a 1954 Swallow Doretti, a fixer-upper. ‘‘It probably needs new brakes,’’ he said. I asked him if there was anywhere he liked to drive for fun. ‘‘No,’’ he replied. ‘‘Not anymore.’’

I had stopped by his office to say goodbye and ask him what he planned to do with his newfound freedom. I pictured him in the Doretti, flying down the Pacific Coast Highway, wind in his hair. But he seemed to be in no mood for talking. I wished him well and turned to go. Then he spoke. ‘‘I expect my second stroke will be on the 17th of November,’’ he said ruefully, gesturing toward his empty wall calendar. ‘‘Life expectancy is five to seven years at my age on retiring, so —’’ He paused. ‘‘That was humor, I guess. I’m not looking forward to being even older. Got no choice in the matter.’’

I asked if he ever found himself thinking about the billions of years that the Voyagers will circle the center of the galaxy, long after our sun has exploded, scattering more stardust throughout the universe. ‘‘Of course,’’ he said. ‘‘I was raised in the Roman Rite. I’m pretty much an atheist. But what is the meaning of life? It’s not Monty Python, O.K.?’’

Had he reached any conclusions about what it is? ‘‘Well, on Earth, yeah,’’ he said. ‘‘One species always prepares the way for the next generation — that’s all.’’

An article on Aug. 6 about the Voyager space probes misstated the title of Tom Krimigis. He is the emeritus head of the Space Department at the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University, not the emeritus head of the entire laboratory.

How we handle corrections

Kim Tingley is a contributing writer for the magazine. She last wrote about the future of automation .

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of The New York Times Magazine delivered to your inbox every week

What’s Up in Space and Astronomy

Keep track of things going on in our solar system and all around the universe..

Never miss an eclipse, a meteor shower, a rocket launch or any other 2024 event that’s out of this world with our space and astronomy calendar .

Scientists may have discovered a major flaw in their understanding of dark energy, a mysterious cosmic force . That could be good news for the fate of the universe.

A new set of computer simulations, which take into account the effects of stars moving past our solar system, has effectively made it harder to predict Earth’s future and reconstruct its past.

Dante Lauretta, the planetary scientist who led the OSIRIS-REx mission to retrieve a handful of space dust , discusses his next final frontier.

A nova named T Coronae Borealis lit up the night about 80 years ago. Astronomers say it’s expected to put on another show in the coming months.

Is Pluto a planet? And what is a planet, anyway? Test your knowledge here .

Advertisement

The Message Voyager 1 Carries for Alien Civilizations

The "Golden Record" aboard the interstellar spacecraft is a time capsule of humanity, sent from 1977 to the distant future.

The year was 1977. Jimmy Carter was president. Rod Stewart topped the Billboard chart with " Tonight's the Night (Gonna Be Alright) ." The economy was recovering from recession. Oil was scarce. Ties may have been wide , but patience, among many, was thin. Into that turbulent and indolent and somewhat cynical world -- and on behalf of it -- NASA launched two little probes, tiny even by spaceship standards, from Cape Canaveral. Voyager 1 and its twin, Voyager 2, were initially meant to explore Jupiter, Saturn, and their moons. They did that. But then they kept going. And going. And going. At a rate of 35,000 miles per hour . One of them, almost 35 years to the day after it left Earth behind, finally ventured beyond the influence of the body that has defined so much of life on Earth: the sun .

The Voyager probes are technically unmanned; in another sense, however, they carry all of humanity with them as they speed through space. Each craft bears an object that is, in every way, a record -- of Earth, of humanity, of humanity's drive to reach and strive and dream and connect. The two epic mementos, given the sunny hue of their aluminum coverings, have been dubbed the Golden Records . They were the product of Carl Sagan and a team that, in January 1977, realized the far-traveling probes would stand a better chance than most human spacecraft would of encountering extraterrestrial life. So they decided to undertake a task that was both uniquely human and uniquely of its moment: They would make a record that would, if discovered by aliens, represent humanity. They would make a time capsule of human civilization. One that would, as NASA puts it , "communicate a story of our world to extraterrestrials." An artifact that would be epic and Quixotic in equal measure.

So how would a notional extraterrestrial, encountering this sweeping record of human existence, actually play it? Like you'd play any record . (NASA apparently assumed that alien civilizations, should they be sufficiently advanced, would be familiar with vinyl. Which is fair.) Each Golden Record is encased in a protective aluminum jacket, along with a cartridge and, yep, a needle. And both include instructions -- in the symbolic language you can see etched in the image above -- that both explain the origin of the Voyager crafts and indicate how the record is meant to be played. (Ideally, NASA explains , the record is played at 16-2/3 revolutions per minute.) The logic of all this is simple: It will be tens of thousands of years (if ever) before either Voyager can make a close approach to any planetary system that lies beyond our own. "The spacecraft," Carl Sagan put it , "will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced spacefaring civilizations in interstellar space."

He added: "But the launching of this bottle into the cosmic ocean says something very hopeful about life on this planet."

Link to Smithsonian homepage

Voyager Golden Record: Through Struggle to the Stars

Voyager "Sounds Of Earth" Record Cover, 1977, National Air and Space Museum, Transferred from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

An intergalactic message in a bottle, the Voyager Golden Record was launched into space late in the summer of 1977. Conceived as a sort of advance promo disc advertising planet Earth and its inhabitants, it was affixed to Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, spacecraft designed to fly to the outer reaches of the solar system and beyond, providing data and documentation of Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto. And just in case an alien lifeform stumbled upon either of the spacecraft, the Golden Record would provide them with information about Earth and its inhabitants, alongside media meant to encourage curiosity and contact.

Listen to the music recorded on the Voyager album with this Spotify playlist from user Ulysses' Classical.

Recorded at 16 ⅔ RPM to maximize play time, each gold-plaited, copper disc was engraved with the same program of 31 musical tracks—ranging from an excerpt of Mozart’s Magic Flute to a field recording made by Alan Lomax of Solomon Island panpipe players—spoken greetings in 55 languages, a sonic collage of recorded natural sounds and human-made sounds (“The Sounds of Earth”), 115 analogue-encoded images including a pulsar map to help in finding one’s way to Earth, a recording of the creative director’s brainwaves, and a Morse-code rendering of the Latin phrase per aspera ad astra (“through struggle to the stars”). In 2012, Voyager 1 became the first Earth craft to burst the heliospheric bubble and cross over into interstellar space. And in 2018, Voyager 2 crossed the same threshold.

A tiny speck of a spacecraft cast into the endless sea of outer space, each Voyager craft was designed to drift forever with no set point of arrival. Likewise, the Golden Record was designed to be playable for up to a billion years, despite the long odds that anyone or anything would ever discover and “listen” to it. Much like the Voyager spacecraft themselves, the journey itself was in large part the point—except that instead of capturing scientific data along the way, the Golden Record instead revealed a great deal about its makers and their historico-cultural context.