10 Economic impacts of tourism + explanations + examples

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

There are many economic impacts of tourism, and it is important that we understand what they are and how we can maximise the positive economic impacts of tourism and minimise the negative economic impacts of tourism.

Many argue that the tourism industry is the largest industry in the world. While its actual value is difficult to accurately determine, the economic potential of the tourism industry is indisputable. In fact, it is because of the positive economic impacts that most destinations embark on their tourism journey.

There is, however, more than meets the eye in most cases. The positive economic impacts of tourism are often not as significant as anticipated. Furthermore, tourism activity tends to bring with it unwanted and often unexpected negative economic impacts of tourism.

In this article I will discuss the importance of understanding the economic impacts of tourism and what the economic impacts of tourism might be. A range of positive and negative impacts are discussed and case studies are provided.

At the end of the post I have provided some additional reading on the economic impacts of tourism for tourism stakeholders , students and those who are interested in learning more.

Foreign exchange earnings

Contribution to government revenues, employment generation, contribution to local economies, development of the private sector, infrastructure cost, increase in prices, economic dependence of the local community on tourism, foreign ownership and management, economic impacts of tourism: conclusion, further reading on the economic impacts of tourism, the economic impacts of tourism: why governments invest.

Tourism brings with it huge economic potential for a destination that wishes to develop their tourism industry. Employment, currency exchange, imports and taxes are just a few of the ways that tourism can bring money into a destination.

In recent years, tourism numbers have increased globally at exponential rates, as shown in the World Tourism Organisation data below.

There are a number of reasons for this growth including improvements in technology, increases in disposable income, the growth of budget airlines and consumer desires to travel further, to new destinations and more often.

Here are a few facts about the economic importance of the tourism industry globally:

- The tourism economy represents 5 percent of world GDP

- Tourism contributes to 6-7 percent of total employment

- International tourism ranks fourth (after fuels, chemicals and automotive products) in global exports

- The tourism industry is valued at US$1trillion a year

- Tourism accounts for 30 percent of the world’s exports of commercial services

- Tourism accounts for 6 percent of total exports

- 1.4billion international tourists were recorded in 2018 (UNWTO)

- In over 150 countries, tourism is one of five top export earners

- Tourism is the main source of foreign exchange for one-third of developing countries and one-half of less economically developed countries (LEDCs)

There is a wealth of data about the economic value of tourism worldwide, with lots of handy graphs and charts in the United Nations Economic Impact Report .

In short, tourism is an example of an economic policy pursued by governments because:

- it brings in foreign exchange

- it generates employment

- it creates economic activity

Building and developing a tourism industry, however, involves a lot of initial and ongoing expenditure. The airport may need expanding. The beaches need to be regularly cleaned. New roads may need to be built. All of this takes money, which is usually a financial outlay required by the Government.

For governments, decisions have to be made regarding their expenditure. They must ask questions such as:

How much money should be spent on the provision of social services such as health, education, housing?

How much should be spent on building new tourism facilities or maintaining existing ones?

If financial investment and resources are provided for tourism, the issue of opportunity costs arises.

By opportunity costs, I mean that by spending money on tourism, money will not be spent somewhere else. Think of it like this- we all have a specified amount of money and when it runs out, it runs out. If we decide to buy the new shoes instead of going out for dinner than we might look great, but have nowhere to go…!

In tourism, this means that the money and resources that are used for one purpose may not then be available to be used for other purposes. Some destinations have been known to spend more money on tourism than on providing education or healthcare for the people who live there, for example.

This can be said for other stakeholders of the tourism industry too.

There are a number of independent, franchised or multinational investors who play an important role in the industry. They may own hotels, roads or land amongst other aspects that are important players in the overall success of the tourism industry. Many businesses and individuals will take out loans to help fund their initial ventures.

So investing in tourism is big business, that much is clear. What what are the positive and negative impacts of this?

Positive economic impacts of tourism

So what are the positive economic impacts of tourism? As I explained, most destinations choose to invest their time and money into tourism because of the positive economic impacts that they hope to achieve. There are a range of possible positive economic impacts. I will explain the most common economic benefits of tourism below.

One of the biggest benefits of tourism is the ability to make money through foreign exchange earnings.

Tourism expenditures generate income to the host economy. The money that the country makes from tourism can then be reinvested in the economy. How a destination manages their finances differs around the world; some destinations may spend this money on growing their tourism industry further, some may spend this money on public services such as education or healthcare and some destinations suffer extreme corruption so nobody really knows where the money ends up!

Some currencies are worth more than others and so some countries will target tourists from particular areas. I remember when I visited Goa and somebody helped to carry my luggage at the airport. I wanted to give them a small tip and handed them some Rupees only to be told that the young man would prefer a British Pound!

Currencies that are strong are generally the most desirable currencies. This typically includes the British Pound, American, Australian and Singapore Dollar and the Euro .

Tourism is one of the top five export categories for as many as 83% of countries and is a main source of foreign exchange earnings for at least 38% of countries.

Tourism can help to raise money that it then invested elsewhere by the Government. There are two main ways that this money is accumulated.

Direct contributions are generated by taxes on incomes from tourism employment and tourism businesses and things such as departure taxes.

Taxes differ considerably between destinations. I will never forget the first time that I was asked to pay a departure tax (I had never heard of it before then), because I was on my way home from a six month backpacking trip and I was almost out of money!

Japan is known for its high departure taxes. Here is a video by a travel blogger explaining how it works.

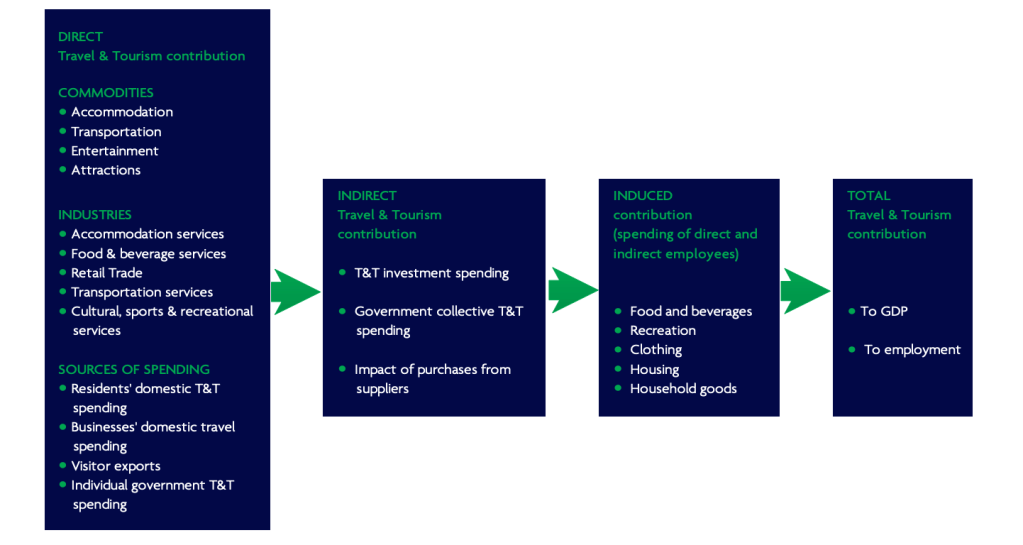

According to the World Tourism Organisation, the direct contribution of Travel & Tourism to GDP in 2018 was $2,750.7billion (3.2% of GDP). This is forecast to rise by 3.6% to $2,849.2billion in 2019.

Indirect contributions come from goods and services supplied to tourists which are not directly related to the tourism industry.

Take food, for example. A tourist may buy food at a local supermarket. The supermarket is not directly associated with tourism, but if it wasn’t for tourism its revenues wouldn’t be as high because the tourists would not shop there.

There is also the income that is generated through induced contributions . This accounts for money spent by the people who are employed in the tourism industry. This might include costs for housing, food, clothing and leisure Activities amongst others. This will all contribute to an increase in economic activity in the area where tourism is being developed.

The rapid expansion of international tourism has led to significant employment creation. From hotel managers to theme park operatives to cleaners, tourism creates many employment opportunities. Tourism supports some 7% of the world’s workers.

There are two types of employment in the tourism industry: direct and indirect.

Direct employment includes jobs that are immediately associated with the tourism industry. This might include hotel staff, restaurant staff or taxi drivers, to name a few.

Indirect employment includes jobs which are not technically based in the tourism industry, but are related to the tourism industry. Take a fisherman, for example. He does not have any contact of dealings with tourists. BUT he does sell his fish to the hotel which serves tourists. So he is indirectly employed by the tourism industry, because without the tourists he would not be supplying the fish to the hotel.

It is because of these indirect relationships, that it is very difficult to accurately measure the economic value of tourism.

It is also difficult to say how many people are employed, directly and indirectly, within the tourism industry.

Furthermore, many informal employments may not be officially accounted for. Think tut tut driver in Cambodia or street seller in The Gambia – these people are not likely to be registered by the state and therefore their earnings are not declared.

It is for this reason that some suggest that the actual economic benefits of tourism may be as high as double that of the recorded figures!

All of the money raised, whether through formal or informal means, has the potential to contribute to the local economy.

If sustainable tourism is demonstrated, money will be directed to areas that will benefit the local community most.

There may be pro-poor tourism initiatives (tourism which is intended to help the poor) or volunteer tourism projects.

The government may reinvest money towards public services and money earned by tourism employees will be spent in the local community. This is known as the multiplier effect.

The multiplier effect relates to spending in one place creating economic benefits elsewhere. Tourism can do wonders for a destination in areas that may seem to be completely unrelated to tourism, but which are actually connected somewhere in the economic system.

Let me give you an example.

A tourist buys an omelet and a glass of orange juice for their breakfast in the restaurant of their hotel. This simple transaction actually has a significant multiplier effect. Below I have listed just a few of the effects of the tourist buying this breakfast.

The waiter is paid a salary- he spends his salary on schooling for his kids- the school has more money to spend on equipment- the standard of education at the school increases- the kids graduate with better qualifications- as adults, they secure better paying jobs- they can then spend more money in the local community…

The restaurant purchases eggs from a local farmer- the farmer uses that money to buy some more chickens- the chicken breeder uses that money to improve the standards of their cages, meaning that the chickens are healthier, live longer and lay more eggs- they can now sell the chickens for a higher price- the increased money made means that they can hire an extra employee- the employee spends his income in the local community…

The restaurant purchase the oranges from a local supplier- the supplier uses this money to pay the lorry driver who transports the oranges- the lorry driver pays road tax- the Government uses said road tax income to fix pot holes in the road- the improved roads make journeys quicker for the local community…

So as you can see, that breakfast that the tourist probably gave not another thought to after taking his last mouthful of egg, actually had the potential to have a significant economic impact on the local community!

The private sector has continuously developed within the tourism industry and owning a business within the private sector can be extremely profitable; making this a positive economic impact of tourism.

Whilst many businesses that you will come across are multinational, internationally-owned organisations (which contribute towards economic leakage ).

Many are also owned by the local community. This is the case even more so in recent years due to the rise in the popularity of the sharing economy and the likes of Airbnb and Uber, which encourage the growth of businesses within the local community.

Every destination is different with regards to how they manage the development of the private sector in tourism.

Some destinations do not allow multinational organisations for fear that they will steal business and thus profits away from local people. I have seen this myself in Italy when I was in search of a Starbucks mug for my collection , only to find that Italy has not allowed the company to open up any shops in their country because they are very proud of their individually-owned coffee shops.

Negative economic impacts of tourism

Unfortunately, the tourism industry doesn’t always smell of roses and there are also several negative economic impacts of tourism.

There are many hidden costs to tourism, which can have unfavourable economic effects on the host community.

Whilst such negative impacts are well documented in the tourism literature, many tourists are unaware of the negative effects that their actions may cause. Likewise, many destinations who are inexperienced or uneducated in tourism and economics may not be aware of the problems that can occur if tourism is not management properly.

Below, I will outline the most prominent negative economic impacts of tourism.

Economic leakage in tourism is one of the major negative economic impacts of tourism. This is when money spent does not remain in the country but ends up elsewhere; therefore limiting the economic benefits of tourism to the host destination.

The biggest culprits of economic leakage are multinational and internationally-owned corporations, all-inclusive holidays and enclave tourism.

I have written a detailed post on the concept of economic leakage in tourism, you can take a look here- Economic leakage in tourism explained .

Another one of the negative economic impacts of tourism is the cost of infrastructure. Tourism development can cost the local government and local taxpayers a great deal of money.

Tourism may require the government to improve the airport, roads and other infrastructure, which are costly. The development of the third runway at London Heathrow, for example, is estimated to cost £18.6billion!

Money spent in these areas may reduce government money needed in other critical areas such as education and health, as I outlined previously in my discussion on opportunity costs.

One of the most obvious economic impacts of tourism is that the very presence of tourism increases prices in the local area.

Have you ever tried to buy a can of Coke in the supermarket in your hotel? Or the bar on the beachfront? Walk five minutes down the road and try buying that same can in a local shop- I promise you, in the majority of cases you will see a BIG difference In cost! (For more travel hacks like this subscribe to my newsletter – I send out lots of tips, tricks and coupons!)

Increasing demand for basic services and goods from tourists will often cause price hikes that negatively impact local residents whose income does not increase proportionately.

Tourism development and the related rise in real estate demand may dramatically increase building costs and land values. This often means that local people will be forced to move away from the area that tourism is located, known as gentrification.

Taking measures to ensure that tourism is managed sustainably can help to mitigate this negative economic impact of tourism. Techniques such as employing only local people, limiting the number of all-inclusive hotels and encouraging the purchasing of local products and services can all help.

Another one of the major economic impacts of tourism is dependency. Many countries run the risk of becoming too dependant on tourism. The country sees $ signs and places all of its efforts in tourism. Whilst this can work out well, it is also risky business!

If for some reason tourism begins to lack in a destination, then it is important that the destination has alternative methods of making money. If they don’t, then they run the risk of being in severe financial difficulty if there is a decline in their tourism industry.

In The Gambia, for instance, 30% of the workforce depends directly or indirectly on tourism. In small island developing states, percentages can range from 83% in the Maldives to 21% in the Seychelles and 34% in Jamaica.

There are a number of reasons that tourism could decline in a destination.

The Gambia has experienced this just recently when they had a double hit on their tourism industry. The first hit was due to political instability in the country, which has put many tourists off visiting, and the second was when airline Monarch went bust, as they had a large market share in flights to The Gambia.

Other issues that could result in a decline in tourism includes economic recession, natural disasters and changing tourism patterns. Over-reliance on tourism carries risks to tourism-dependent economies, which can have devastating consequences.

The last of the negative economic impacts of tourism that I will discuss is that of foreign ownership and management.

As enterprise in the developed world becomes increasingly expensive, many businesses choose to go abroad. Whilst this may save the business money, it is usually not so beneficial for the economy of the host destination.

Foreign companies often bring with them their own staff, thus limiting the economic impact of increased employment. They will usually also export a large proportion of their income to the country where they are based. You can read more on this in my post on economic leakage in tourism .

As I have demonstrated in this post, tourism is a significant economic driver the world over. However, not all economic impacts of tourism are positive. In order to ensure that the economic impacts of tourism are maximised, careful management of the tourism industry is required.

If you enjoyed this article on the economic impacts of tourism I am sure that you will love these too-

- Environmental impacts of tourism

- The 3 types of travel and tourism organisations

- 150 types of tourism! The ultimate tourism glossary

- 50 fascinating facts about the travel and tourism industry

- 23 Types of Water Transport To Keep You Afloat

Liked this article? Click to share!

- Press Releases

- Press Enquiries

- Travel Hub / Blog

- Brand Resources

- Newsletter Sign Up

- Global Summit

- Hosting a Summit

- Upcoming Events

- Previous Events

- Event Photography

- Event Enquiries

- Our Members

- Our Associates Community

- Membership Benefits

- Enquire About Membership

- Sponsors & Partners

- Insights & Publications

- WTTC Research Hub

- Economic Impact

- Knowledge Partners

- Data Enquiries

- Hotel Sustainability Basics

- Community Conscious Travel

- SafeTravels Stamp Application

- SafeTravels: Global Protocols & Stamp

- Security & Travel Facilitation

- Sustainable Growth

- Women Empowerment

- Destination Spotlight - SLO CAL

- Vision For Nature Positive Travel and Tourism

- Governments

- Consumer Travel Blog

- ONEin330Million Campaign

- Reunite Campaign

Economic Impact Research

- In 2023, the Travel & Tourism sector contributed 9.1% to the global GDP; an increase of 23.2% from 2022 and only 4.1% below the 2019 level.

- In 2023, there were 27 million new jobs, representing a 9.1% increase compared to 2022, and only 1.4% below the 2019 level.

- Domestic visitor spending rose by 18.1% in 2023, surpassing the 2019 level.

- International visitor spending registered a 33.1% jump in 2023 but remained 14.4% below the 2019 total.

Click here for links to the different economy/country and regional reports

Why conduct research?

From the outset, our Members realised that hard economic facts were needed to help governments and policymakers truly understand the potential of Travel & Tourism. Measuring the size and growth of Travel & Tourism and its contribution to society, therefore, plays a vital part in underpinning WTTC’s work.

What research does WTTC carry out?

Each year, WTTC and Oxford Economics produce reports covering the economic contribution of our sector in 185 countries, for 26 economic and geographic regions, and for more than 70 cities. We also benchmark Travel & Tourism against other economic sectors and analyse the impact of government policies affecting the sector such as jobs and visa facilitation.

Visit our Research Hub via the button below to find all our Economic Impact Reports, as well as other reports on Travel and Tourism.

The COVID-19 travel shock hit tourism-dependent economies hard

- Download the paper here

Subscribe to the Hutchins Roundup and Newsletter

Gian maria milesi-ferretti gian maria milesi-ferretti senior fellow - economic studies , the hutchins center on fiscal and monetary policy.

August 12, 2021

The COVID crisis has led to a collapse in international travel. According to the World Tourism Organization , international tourist arrivals declined globally by 73 percent in 2020, with 1 billion fewer travelers compared to 2019, putting in jeopardy between 100 and 120 million direct tourism jobs. This has led to massive losses in international revenues for tourism-dependent economies: specifically, a collapse in exports of travel services (money spent by nonresident visitors in a country) and a decline in exports of transport services (such as airline revenues from tickets sold to nonresidents).

This “travel shock” is continuing in 2021, as restrictions to international travel persist—tourist arrivals for January-May 2021 are down a further 65 percent from the same period in 2020, and there is substantial uncertainty on the nature and timing of a tourism recovery.

We study the economic impact of the international travel shock during 2020, particularly the severity of the hit to countries very dependent on tourism. Our main result is that on a cross-country basis, the share of tourism activities in GDP is the single most important predictor of the growth shortfall in 2020 triggered by the COVID-19 crisis (relative to pre-pandemic IMF forecasts), even when compared to measures of the severity of the pandemic. For instance, Grenada and Macao had very few recorded COVID cases in relation to their population size and no COVID-related deaths in 2020—yet their GDP contracted by 13 percent and 56 percent, respectively.

International tourism destinations and tourism sources

Countries that rely heavily on tourism, and in particular international travelers, tend to be small, have GDP per capita in the middle-income and high-income range, and are preponderately net debtors. Many are small island economies—Jamaica and St. Lucia in the Caribbean, Cyprus and Malta in the Mediterranean, the Maldives and Seychelles in the Indian Ocean, or Fiji and Samoa in the Pacific. Prior to the COVID pandemic, median annual net revenues from international tourism (spending by foreign tourists in the country minus tourism spending by domestic residents overseas) in these island economies were about one quarter of GDP, with peaks around 50 percent of GDP, such as Aruba and the Maldives.

But there are larger economies heavily reliant on international tourism. For instance, in Croatia average net international tourism revenues from 2015-2019 exceeded 15 percent of GDP, 8 percent in the Dominican Republic and Thailand, 7 percent in Greece, and 5 percent in Portugal. The most extreme example is Macao, where net revenues from international travel and tourism were around 68 percent of GDP during 2015-19. Even in dollar terms, Macao’s net revenues from tourism were the fourth highest in the world, after the U.S., Spain, and Thailand.

In contrast, for countries that are net importers of travel and tourism services—that is, countries whose residents travel widely abroad relative to foreign travelers visiting the country—the importance of such spending is generally much smaller as a share of GDP. In absolute terms, the largest importer of travel services is China (over $200 billion, or 1.7 percent of GDP on average during 2015-19), followed by Germany and Russia. The GDP impact for these economies of a sharp reduction in tourism outlays overseas is hence relatively contained, but it can have very large implications on the smaller economies their tourists travel to—a prime example being Macao for Chinese travelers.

How did tourism-dependent economies cope with the disappearance of a large share of their international revenues in 2020? They were forced to borrow more from abroad (technically, their current account deficit widened, or their surplus shrank), but also reduced net international spending in other categories. Imports of goods declined (reflecting both a contraction in domestic demand and a decline in tourism inputs such as imported food and energy) and payments to foreign creditors were lower, reflecting the decline in returns for foreign-owned hotel infrastructure.

The growth shock

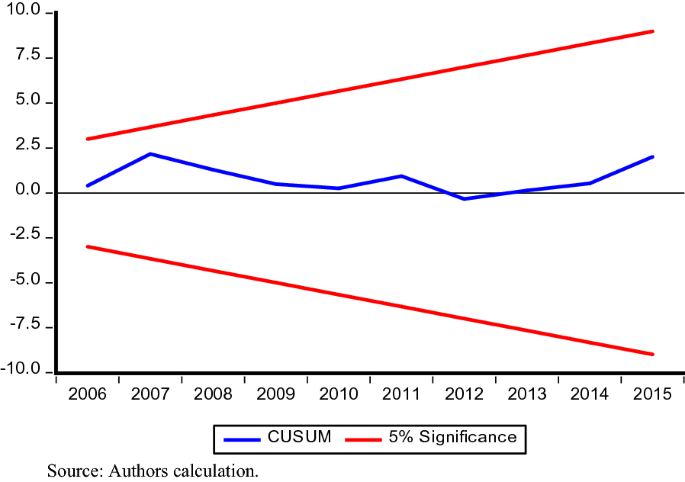

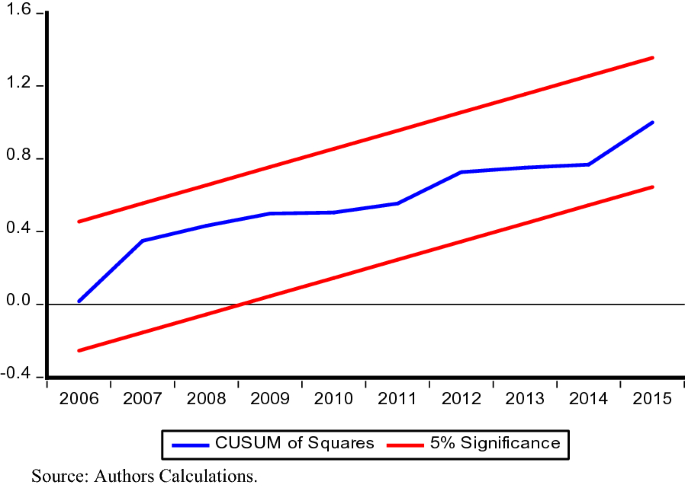

We then examine whether countries more dependent on tourism suffered a bigger shock to economic activity in 2020 than other countries, measuring this shock as the difference between growth outcomes in 2020 and IMF growth forecasts as of January 2020, just prior to the pandemic. Our measure of the overall importance of tourism is the share of GDP accounted for by tourism-related activity over the 5 years preceding the pandemic, assembled by the World Travel and Tourism Council and disseminated by the World Bank . This measure takes into account the importance of domestic tourism as well as international tourism.

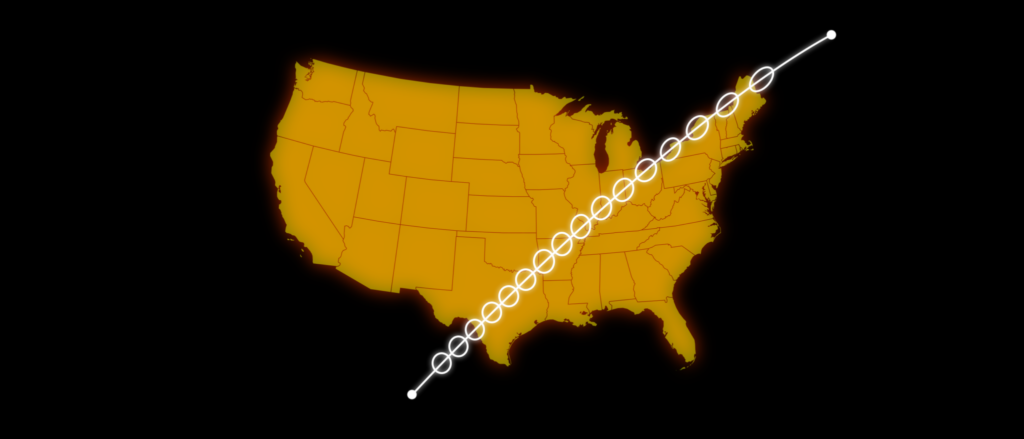

Among the 40 countries with the largest share of tourism in GDP, the median size of growth shortfall compared to pre-COVID projections was around 11 percent, as against 6 percent for countries less dependent on tourism. For instance, in the tourism-dependent group, Greece, which was expected to grow by 2.3 percent in 2020, shrunk by over 8 percent, while in the other group, Germany, which was expected to grow by around 1 percent, shrunk by 4.8 percent. The scatter plot of Figure 2 provides more striking visual evidence of a negative correlation (-0.72) between tourism dependence and the growth shock in 2020.

Of course, many other factors may have affected differences in performance across economies—for instance, the intensity of the pandemic as well as the stringency of the associated lockdowns. We therefore build a simple statistical model that relates the “growth shock” in 2020 to these factors alongside our tourism variable, and also takes into account other potentially relevant country characteristics, such as the level of development, the composition of output, and country size. The message: the dependence on tourism is a key explanatory variable of the growth shock in 2020. For instance, the analysis suggests that going from the share of tourism in GDP of Canada (around 6 percent) to the one of Mexico (around 16 percent) would reduce growth in 2020 by around 2.5 percentage points. If we instead go from the tourism share of Canada to the one of Jamaica (where the share of tourism in GDP approaches one third), growth would be lower by over 6 percentage points.

Measures of the severity of the pandemic, the intensity of lockdowns, the level of development, and the sectoral composition of GDP (value added accounted for by manufacturing and agriculture) also matter, but quantitatively less so than tourism. And results are not driven by very small economies; tourism is still a key explanatory variable of the 2020 growth shock even if we restrict our sample to large economies. Among tourism-dependent economies, we also find evidence that those relying more heavily on international tourism experienced a more severe hit to economic activity when compared to those relying more on domestic tourism.

Given data availability at the time of writing, the evidence we provided is limited to 2020. The outlook for international tourism in 2021, if anything, is worse, though with increasing vaccine coverage the tide could turn next year. The crisis poses particularly daunting challenges to smaller tourist destinations, given limited possibilities for diversification. In many cases, particularly among emerging and developing economies, these challenges are compounded by high starting levels of domestic and external indebtedness, which can limit the space for an aggressive fiscal response. Helping these countries cope with the challenges posed by the pandemic and restoring viable public and external finances will require support from the international community.

Read the full paper here.

Related Content

February 18, 2021

Eldah Onsomu, Boaz Munga, Violet Nyabaro

July 28, 2021

Célia Belin

May 21, 2021

The author thanks Manuel Alcala Kovalski and Jimena Ruiz Castro for their excellent research assistance.

Economic Studies

The Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy

Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, Alexander Conner

April 19, 2024

Belinda Archibong, Peter Blair Henry

April 18, 2024

Witney Schneidman

April 17, 2024

What is overtourism and how can we overcome it?

The issue of overtourism has become a major concern due to the surge in travel following the pandemic. Image: Reuters/Manuel Silvestri (ITALY - Tags: ENTERTAINMENT)

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Joseph Martin Cheer

Marina novelli.

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Travel and Tourism is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, travel and tourism.

Listen to the article

- Overtourism has once again become a concern, particularly after the rebound of international travel post-pandemic.

- Communities in popular destinations worldwide have expressed concerns over excess tourism on their doorstep.

- Here we outline the complexities of overtourism and the possible measures that can be taken to address the problem.

The term ‘overtourism’ has re-emerged as tourism recovery has surged around the globe. But already in 2019, angst over excessive tourism growth was so high that the UN World Tourism Organization called for “such growth to be managed responsibly so as to best seize the opportunities tourism can generate for communities around the world”.

This was especially evident in cities like Barcelona, where anti-tourism sentiment built up in response to pent-up frustration about rapid and unyielding tourism growth. Similar local frustration emerged in other famous cities, including Amsterdam , Venice , London , Kyoto and Dubrovnik .

While the pandemic was expected to usher in a new normal where responsible and sustainable travel would emerge, this shift was evidently short-lived, as demand surged in 2022 and 2023 after travel restrictions eased.

Have you read?

Ten principles for sustainable destinations: charting a new path forward for travel and tourism.

This has been witnessed over the recent Northern Hemisphere summer season, during which popular destinations heaved under the pressure of pent-up post-pandemic demand , with grassroots communities articulating over-tourism concerns.

Concerns over excess tourism have not only been seen in popular cities but also on the islands of Hawaii and Greece , beaches in Spain , national parks in the United States and Africa , and places off the beaten track like Japan ’s less explored regions.

What is overtourism?

The term overtourism was employed by Freya Petersen in 2001, who lamented the excesses of tourism development and governance deficits in the city of Pompei. Her sentiments are increasingly familiar among tourists in other top tourism destinations more than 20 years later.

Overtourism is more than a journalistic device to arouse host community anxiety or demonize tourists through anti-tourism activism. It is also more than simply being a question of management – although poor or lax governance most definitely accentuates the problem.

Governments at all levels must be decisive and firm about policy responses that control the nature of tourist demand and not merely give in to profits that flow from tourist expenditure and investment.

Overtourism is often oversimplified as being a problem of too many tourists. While that may well be an underlying symptom of excess, it fails to acknowledge the myriad factors at play.

In its simplest iteration, overtourism results from tourist demand exceeding the carrying capacity of host communities in a destination. Too often, the tourism supply chain stimulates demand, giving little thought to the capacity of destinations and the ripple effects on the well-being of local communities.

Overtourism is arguably a social phenomenon too. In China and India, two of the most populated countries where space is a premium, crowded places are socially accepted and overtourism concerns are rarely articulated, if at all. This suggests that cultural expectations of personal space and expectations of exclusivity differ.

We also tend not to associate ‘overtourism’ with Africa . But uncontrolled growth in tourist numbers is unsustainable anywhere, whether in an ancient European city or the savannah of a sub-Saharan context.

Overtourism must also have cultural drivers that are intensified when tourists' culture is at odds with that of host communities – this might manifest as breaching of public norms, irritating habits, unacceptable behaviours , place-based displacement and inconsiderate occupation of space.

The issue also comes about when the economic drivers of tourism mean that those who stand to benefit from growth are instead those who pay the price of it, particularly where gentrification and capital accumulation driven from outside results in local resident displacement and marginalization.

Overcoming overtourism excesses

Radical policy measures that break the overtourism cycle are becoming more common. For example, Amsterdam has moved to ban cruise ships by closing the city’s cruise terminal.

Tourism degrowth has long been posited as a remedy to overtourism. While simply cutting back on tourist numbers seems like a logical response, whether the economic trade-offs of fewer tourists will be tolerated is another thing altogether.

The Spanish island of Lanzarote moved to desaturate the island by calling the industry to focus on quality tourism rather than quantity. This shift to quality, or higher yielding, tourists has been mirrored in many other destinations, like Bali , for example.

Dispersing tourists outside hotspots is commonly seen as a means of dealing with too much tourism. However, whether sufficient interest to go off the beaten track can be stimulated might be an immoveable constraint, or simply result in problem shifting .

Demarketing destinations has been applied with varying degrees of success. However, whether it can address the underlying factors in the long run is questioned, particularly as social media influencers and travel writers continue to give attention to touristic hotspots. In France, asking visitors to avoid Mont Saint-Michelle and instead recommending they go elsewhere is evidence of this.

Introducing entry fees and gates to over-tourist places like Venice is another deterrent. This assumes visitors won’t object to paying and that revenues generated are spent on finding solutions rather than getting lost in authorities’ consolidated revenue.

Advocacy and awareness campaigns against overtourism have also been prominent, but whether appeals to tourists asking them to curb irresponsible behaviours have had any impact remains questionable as incidents continue —for example, the Palau Pledge and New Zealand’s Tiaki Promise appeal for more responsible behaviours.

Curtailing the use of the word overtourism is also posited – in the interest of avoiding the rise of moral panics and the swell of anti-tourism social movements, but pretending the phenomenon does not exist, or dwelling on semantics won’t solve the problem .

Solutions to address overtourism

The solutions to dealing adequately with the effects of overtourism are likely to be many and varied and must be tailored to the unique, relevant destination .

The tourism supply chain must also bear its fair share of responsibility. While popular destinations are understandably an easier sell, redirecting tourism beyond popular honeypots like urban heritage sites or overcrowded beaches needs greater impetus to avoid shifting the problem elsewhere.

Local authorities must exercise policy measures that establish capacity limits, then ensure they are upheld, and if not, be held responsible for their inaction .

Meanwhile, tourists themselves should take responsibility for their behaviour and decisions while travelling, as this can make a big difference to the impact on local residents .

Those investing in tourism should support initiatives that elevate local priorities and needs, and not simply exercise a model of maximum extraction for shareholders in the supply chain.

How is the World Economic Forum supporting the development of cities and communities globally?

The Data for the City of Tomorrow report highlighted that in 2023, around 56% of the world is urbanized. Almost 65% of people use the internet. Soon, 75% of the world’s jobs will require digital skills.

The World Economic Forum’s Centre for Urban Transformation is at the forefront of advancing public-private collaboration in cities. It enables more resilient and future-ready communities and local economies through green initiatives and the ethical use of data.

Learn more about our impact:

- Net Zero Carbon Cities: Through this initiative, we are sharing more than 200 leading practices to promote sustainability and reducing emissions in urban settings and empower cities to take bold action towards achieving carbon neutrality .

- G20 Global Smart Cities Alliance: We are dedicated to establishing norms and policy standards for the safe and ethical use of data in smart cities , leading smart city governance initiatives in more than 36 cities around the world.

- Empowering Brazilian SMEs with IoT adoption : We are removing barriers to IoT adoption for small and medium-sized enterprises in Brazil – with participating companies seeing a 192% return on investment.

- IoT security: Our Council on the Connected World established IoT security requirements for consumer-facing devices . It engages over 100 organizations to safeguard consumers against cyber threats.

- Healthy Cities and Communities: Through partnerships in Jersey City and Austin, USA, as well as Mumbai, India, this initiative focuses on enhancing citizens' lives by promoting better nutritional choices, physical activity, and sanitation practices.

Want to know more about our centre’s impact or get involved? Contact us .

National tourist offices and destination management organizations must support development that is nuanced and in tune with the local backdrop rather than simply mimicking mass-produced products and experiences.

The way tourist experiences are developed and shaped must be transformed to move away from outright consumerist fantasies to responsible consumption .

The overtourism problem will be solved through a clear-headed, collaborative and case-specific assessment of the many drivers in action. Finally, ignoring historical precedents that have led to the current predicament of overtourism and pinning this on oversimplified prescriptions abandons any chance of more sustainable and equitable tourism futures .

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Travel and Tourism .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

How Japan is attracting digital nomads to shape local economies and innovation

Naoko Tochibayashi and Naoko Kutty

March 28, 2024

Turning tourism into development: Mitigating risks and leveraging heritage assets

Abeer Al Akel and Maimunah Mohd Sharif

February 15, 2024

Buses are key to fuelling Indian women's economic success. Here's why

Priya Singh

February 8, 2024

These are the world’s most powerful passports to have in 2024

Thea de Gallier

January 31, 2024

These are the world’s 9 most powerful passports in 2024

South Korea is launching a special visa for K-pop lovers

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Economic effects of tourism and its influencing factors

An overview focusing on the spending determinants of visitors, zusammenfassung.

Zahlreiche Studien belegen die ökonomische Bedeutung des Tourismus, die mit Hilfe verschiedener theoretischer Konzepte und Methodenansätze analysiert werden kann. Dieser Einführungsbeitrag in das Themenheft gibt einen Überblick über die unterschiedlichen Konzepte zu den wirtschaftlichen Wirkungen des Tourismus und arbeitet deren wichtigste Einflussfaktoren heraus. Häufig werden der räumliche Maßstab sowie die Kostenseite des Tourismus übersehen. Besonderes Augenmerk richtet der vorliegende Beitrag auf einen weiteren, entscheidenden Einflussfaktor ökonomischer Effekte, die Besucherausgaben. Die Rolle des Ausgabeverhaltens der Besucher wird unter Rückgriff auf einen umfassenden Literaturüberblick vorgestellt. Auf diese Weise ist es möglich, auf verallgemeinerbare und systematische Weise die wichtigsten Treiber des Ausgabeverhaltens von Besuchern zu identifizieren.

The economic relevance of tourism has been proven by numerous studies using various theoretical constructs and methodological approaches. This introduction to the special issue provides an overview of the different concepts of the economic effects of tourism and distinguishes their most relevant influencing factors. Often overlooked influences are the geographical scale and the cost side of tourism. A special focus of this paper lies on a further determinant of economic impact of utmost importance: visitor spending. The role of visitors’ expenditure behavior is comprehensively reviewed using an extensive literature base. Thus, we are able to identify the most important driving factors of visitor expenditure in tourism in a generalizable and systematic way.

1 Introduction

Tourism is often regarded (and used by regional developers and funding institutions) as an economic development path for structurally weak, peripheral areas, as a cure-all providing jobs and income, capital inflow and finally stopping outmigration by creating a positive socio-economic perspective for the future. However, more often than not these high hopes fall short and either the number of visitors or the resulting economic contribution or even both do not meet earlier expectations ( Vogt 2008 ; Blake et al. 2008 , p. 115; Lehmeier 2015 ; Mayer, Job 2016 ). In order to put these expectations on more realistic grounds, respectively to choose more suitable development strategies, a deeper understanding of the mechanisms is required: What influences the economic outcomes of tourism and can these determinants in turn be optimized by decision makers? However, before dealing with this question, it appears necessary to first clarify what the economic consequences of tourism activities actually are – as stakeholders tend to become confused by different concepts like economic contribution, impact or benefits, gross turnover, value added, or economic value (see section 2 )–, how they occur, how different measures vary and what costs have to be taken into account. In practice, these considerations should lead to a more realistic picture of tourism as a means of regional development and to better-reasoned strategies.

There are also additional reasons why the topic of the economic effects of tourism is very relevant for both academic research and practitioner-oriented consultancy: First, and in contrast to other sectors whose economic relevance is not contested, respectively broadly recognized (like car manufacturing in Germany for instance), tourism stakeholders need to underline the economic relevance of tourism in order to emphasize lobby efforts regarding financial resources, laws, planning, regulation, taxation and subsidies ( Hall, Page 2006 , p. 155; Stabler et al. 2010 , p. 199). There is a danger as Crompton ( 2006 , p. 67) puts it: “Most economic impact studies are commissioned to legitimize a political position rather than to search for economic truth”. Second, due to the complex structure of the different branches forming the tourism sector huge empirical efforts are required to measure the economic relevance of tourism for these sub-sectors and branches as well as for the national/regional economy in total. This complexity opened up the path for an own field of research dealing with economic analysis in tourism which has achieved considerable progress over the years. Third, studies evaluating the economic effects of tourism provide the only quantifiable results of tourism impact in monetary terms compared to image, infrastructure or competence effects of tourism where several other variables intervene ( Bieger 2001 ).

For these reasons, this special issue presents recent progress in the field of economic effects of tourism and its influencing factors by researchers from the German-speaking community. As an introduction to this special issue, this article provides an overview of the different measures of the economic importance of tourism and summarizes the influencing factors on the economic contribution of tourism using a self-developed framework ( Section 2 ). One of the most important drivers is the spending behavior of visitors. Thus, this paper offers a comprehensive review of studies dealing with the different determinants of visitor spending by systematizing the influences and drawing generalizable conclusions ( Section 3 ). Finally, this paper provides an outline of the special issue ( Section 4 ).

2 Economic effects of tourism and its influencing factors – an overview

2.1 definitions and differentiations.

The economic effects of tourism are often divided into tangible (quantitative or directly quantifiable in monetary values) and intangible (qualitative or not directly quantifiable) effects ( Woltering 2012 , p. 68; Metzler 2007 , p. 33). The positive tangible and intangible effects correspond to the benefits of tourism for societies and economies. Dwyer et al. ( 2010 , p. 222) point out that economic benefits of tourism equal neither the economic impact of tourism nor the economic contribution of tourism (see Figure 1 ). The notion of economic benefits of tourism require that a territorial entity or citizen has to be better off with tourism than without tourism. Thus, it is the net benefits that have to be analyzed, which encompass both the consideration of the costs of tourism development as well as the opportunity costs of tourism activities ( Dwyer et al. 2010 , p. 222) – defined as forgone income from alternative investment possibilities ( Job, Mayer 2012 ). This notion is related to the often neglected difference between real and distributive effects ( Hanusch 1994 , p. 8 f.; Schönbäck et al. 1997 , p. 4 f.): real effects lead to an overall improvement in the private households’ supply of goods and thus to a positive influence on the overall welfare level. In contrast, distributive effects sum up all monetary changes in the aftermath of a measure where the gains in one sector of the economy mirror the corresponding losses in another – the general welfare level remains constant ( Mayer 2013 , p. 93). Other negative economic effects of tourism for destinations are rising prices due to imported inflation and increasing demand ( Bull 1991 , p. 135) as well as potentially rising taxes because governments need to finance costly tourism infrastructure ( Stynes 1997 , p. 15).

Economic contribution, impact and benefit of tourism and influencing factors. Source: own draft, based on Ennew 2003 and Dwyer et al. 2010 , p. 213 ff.

“The economic contribution of tourism refers to tourism’s economic significance – to the contribution that tourism-related spending makes to … Gross Domestic (Regional) Product, household income, value added, foreign exchange earnings, employment” ( Dwyer et al. 2010 , p. 11, p. 213 f.). One common approach to quantify this economic contribution of tourism is Tourism Satellite Accounts (TSA) ( Spurr 2006 , Frechtling 2010 ). However, TSA as an accounting approach only measure direct effects ( Fig. 1 ), while indirect and induced effects have to be assessed using modeling approaches like input-output-(IO) models ( Ahlert 2003 , p. 19) or more recent advancements (see 2.3). This means that results of TSA and IO approaches are not directly comparable.

“While the economic contribution of tourism measures the size and overall significance of the industry within an economy, economic impact refers to the changes in the economic contribution resulting from specific events or activities that comprise ‘shocks‘ to the tourism system. This should not be confused with the contribution itself” ( Dwyer et al. 2010 , p. 216). These changes are brought about by new/non-regular tourism expenditure injected into a destination. Watson et al. (2007) provide two related definitions of economic impact underlining this understanding: “Economic impacts are the net changes in new economic activity associated with an industry, event, or policy in an existing regional economy” (p. 142). “Economic impact is the best estimation at what economic activity would likely be lost from the local economy if the event, industry, or policy were removed” (p. 143). In our case, this refers to tourism activities, such as a special event, a specific attraction or the shut-down of a previously popular accommodation. Thus, technically, the difference between the analysis of the economic contribution and the impact of tourism lies in the scope of the analysis (overall significance vs. the effect of “shocks”/”changes”) and not in the methods.

Central to both the evaluation of the economic contribution and the impact of tourism is the concept of leakages , occurring in the form of imported intermediate input from outside the country/region but also in the form of profit transfer to external headquarters or tax payments to a government. This means that not the complete share of tourism expenditure leads to income at the destination ( Hjerpe, Kim 2007 , p. 144 f.). On the national level, only the leakages to foreign countries are of interest while on a regional/ local level the share of income remaining in the survey area is crucial. This share is termed capture rate in English ( Stynes 1997 ) or “Wertschöpfungsquote“ in German ( Küpfer 2000 , p. 107 ff.; Job et al. 2009 , p. 33) and can be defined as “tourist expenditures minus leakage“ ( Hjerpe, Kim 2007 , p. 145). A similar concept is the Regional Purchase and Absorption Coefficient (RPC), defined as “the percentage of demand for a sector’s output from within the study area that is supplied by production within the study area” ( Watson et al. 2008 , p. 575). The higher the RPC, respectively the higher the capture rate, the higher the share of tourism income occurring in the survey area ( Hjerpe, Kim 2007 , p. 145; Watson et al. 2008 , p. 575). That means, from an economic geography perspective only the money actually remaining in the survey region is relevant.

As explained above, the economic contribution/impact of tourism refers to the actual expenditures of visitors. In economic valuation terminology, these expenditures represent the visitors’ revealed willingness to pay (WTP) and thus, a (quasi-)market price for recreation ( Moisey 2002 , p. 235 f.; Küpfer 2000 , p. 36). Based on this notion, one aspect is often overlooked, the value of the recreational experience , referring to the consumer surplus of visitors measured in their maximum WTP for visiting a destination/attraction minus their actual expenditure. In other words, the consumer surplus of visitation equals the difference between the visitors’ WTP and the actual expenditure. This is because visitors’ expenditures do not completely reveal their maximum WTP, which differs individually. Consequently, the economic impact only constitutes a subset of the tourism benefits and it does not equal the economic value of recreational use. This aspect is especially important where tourism attractions share characteristics of public goods, such as protected areas which do not charge entrance fees, etc. The recreational value can be estimated, for example, with the help of the travel cost method ( Carlsen 1997 ; Moisey 2002 ; Mayer, Job 2014 , p. 77).

2.2 Spatial aspects of the economic effects of tourism

The economic effects of tourism occur and are measurable on different spatial scales, from the global, continental, national to the regional and local level. Also the relevance of the effects vary along these scales. For instance, on the national level, the effects on the foreign exchange earnings are of great importance. Zooming in to the regional/ local level job creation and leakages become increasingly relevant ( Metzler 2007 , p. 33).

Not only the spatial scale should be taken into account but also the location where expenditures occur and which actors actually profit. Referring to Freyer ( 2011 , p. 41 ff.) we can distinguish between (a) the source area of tourists, (b) the travel area and (c) the destination. Each area has a differing mix of expenditure categories and empirical problems. Ad (a): in the source area, travelers seek information, book their trip and buy equipment. However, it is often problematic to assign expenditures for equipment to a specific trip or holiday. Ad (b): while on the trip, travelers spend money for gas, food, road toll, accommodation for stopovers, etc. Two problems occur: First, most transport expenditures are booked and paid for in advance in the source area and the area crossed by airplanes, trains or ships does not gain any benefits. Second, if one wants to assign the travel expenses to a specific attraction the multiple-trip bias has to be considered (round trips) ( Freeman 2003 , p. 421 f.). Ad (c): at the destination, tourists pay for accommodation, gastronomy, groceries, activities, souvenirs, services, etc. Thus, for a regional economic analysis (for instance of events or specific attractions), the spatial limitation, respectively the size of the destination are crucial influencing factors (see below) “because a good proportion of total spending by spectators might not [have] been incurred within the community” ( Gelan 2003 , p. 411). Furthermore, for these evaluations of attractions or events mostly only the expenditure at the destination is considered while expenditure on the trip or in the source area is disregarded. In general, the economic impact of an event/ attraction is likely inversely related to the distance from its location in space ( Gelan 2003 ). Additional insights into the spatial aspects of the economic effects of tourism can be found in several, mostly case study contributions (e.g. Connell, Page 2005 ; Daniels 2007 ; He et al. 2008 ) which cannot be presented here in detail due to space constraints. However, there is to date no comprehensive review of these works and it would be worth compiling.

2.3 Factors influencing economic effects of tourism

This sub-section presents the factors influencing the economic effects of tourism and discusses the input variables for its analysis. Loomis, Caughlan ( 2006 , p. 33 ff.) sum up the basic requirements for any analysis of the economic contribution/impact of tourism: (a) number of visitor days; (b) spending amounts per visitor; (c) types of visitors and trip purposes; and (d) an economic model to calculate multiplier effects. In addition, there is a moderating effect of the spatial limitation of the survey area.

Ad (a): The number of visitor days is often confused with the number of visitors which could be identical in some cases but most often both measures differ. For overnight tourism also the length of stay, the number of visits to specific attractions or the frequency of an activity have to be taken into account. In this issue, Arnberger et al. (2016) discuss the methods of visitor counting in detail.

Considering visitation it is debatable whether economic impacts of tourism should be used on a national scale, because those of domestic tourism represent distributive effects only ( Küpfer 2000 , p. 68 f.). These visitors would have spent their vacation in their home country anyway or would have visited another destination there instead. Only incoming tourists provide additional input for the national economy ( Schönbäck et al. 1997 , p. 191; Baaske et al. 1998 , p. 159 f.). However, one might argue that a domestic trip can avoid a trip abroad which would lead to leakage from the national economy ( Mayer, Job 2014 , p. 79).

Similarly, it is contested whether local residents in the survey areas should be included in the regional economic assessments. Some maintain that locals should be excluded as their expenditures are considered a re-circulation of preexisting income in the region ( Dwyer et al. 2004 , p. 313 f.; Loomis, Caughlan 2006 ; Crompton et al. 2001 , p. 81). Conversely others argue that ignoring locals’ expenditures will lead to an underestimate of total impacts ( Johnson, Moore 1993 , p. 287). Locals could also spend their money outside their home region again leading to leakages ( Ryan 1998 , p. 345).

Ad (b) Expenditure : Stynes, White (2006) sum up the most important dos and don’ts when it comes to analyzing visitors’ spending behavior, while Frechtling (2006) reviews several methods and models used to estimate visitor expenditures. The third section of this article deals with the influences on expenditure patterns in detail. In addition, Butzmann (2016) analyzes the expenditures of nature tourists in his contribution to this issue.

Ad (c) Trip purpose : In order not to overestimate the economic contribution of specific attractions/ activities the trip purpose has to be analyzed. It is decisive that only those expenditures are considered which are spent in addition to the money spent anyway at the destination as the spenders would have traveled there even if the attraction in question did not exist ( Dixon, Sherman 1990 , p. 155 ff.; Küpfer 2000 ; Job et al. 2009 ; Loomis, Caughlan 2006 , p. 33 ff.).

Ad (d) Multipliers : Economic models are inevitably necessary to estimate the indirect and induced economic effects of tourism and are often regarded as the most complex part of the evaluation process. The evolution of methodologies started with comparatively simple multipliers ( Archer 1977 ) and continued with superior input-output models (IO) ( Fletcher 1989 ). The latter, however, exhibit methodological shortcomings owing to restrictive assumptions like the “free, unrestricted flow of resources to [...] the economy. [...] As a result, it [the IO model] does not capture the feedback effects, which typically work in opposite directions to the initial change“ ( Dwyer et al. 2004 , p. 307; Armstrong, Taylor 2000 , p. 56 ff.). As important improvements to the IO social accounting matrices (SAM) ( Wagner 1997 ) and computable general equilibrium models (CGE) [1] ( Dwyer et al. 2004 ) were proposed, which are able to incorporate resource restrictions and feedback effects ( Zhang et al. 2007 ). The CGE are most likely the most advanced group of multiplier models overcoming many of the overestimation effects of IO-models ( Blake 2005 ; Song et al. 2012 ), even though they still have their drawbacks. These include some restrictive assumptions like constant returns to scale in production functions and perfect markets ( Croes, Severt 2007 ), high input data quality requirements and related costs or the not very vivid presentation of results ( Pfähler 2001 ). Thus, when comparing CGE models to conventional IO Klijs et al. (2012) conclude that CGE models are inferior in terms of transparency (the predictability of results), efficiency (data, time and cost) and comparability (standardization of model structure, complexity and assumptions). In addition, the analysis of past data is beyond the scope of CGE models because they “simulate what will happen in the economy as a consequence of external shocks, but do not state what has already happened” ( Ivanov, Webster 2007 , p. 380). Further (dis)advantages of the modeling approaches are discussed in the academic literature ( West 1995 , Dwyer et al. 2010 , Chap. 7-9, Pratt 2015 , p. 151).

The magnitude of multiplier effects is decisively influenced by three factors ( Archer 1977 : 29 ff., Archer, Fletcher 1996 : p. 58 ff., Wall 1997 , p. 447; Hall, Page 2006 , p. 155): (1) The size of the survey area to which the multiplier refers because the possibilities for economic autarky largely depend on this size. The number of potential spending rounds is also influenced. The larger the survey area, the larger the multipliers and the lower the leakages. (2) The level of economic development of a region: “The more that the inputs of enterprises can be acquired locally, the smaller will be the leakage and the larger will be the multiplier“ ( Wall 1997 , p. 447). However, there is no automatism for higher multipliers due to complex interregional value chains nowadays. (3) The expenditure structure: the higher the locally produced share of goods/ services, the higher also the resulting direct and indirect effects.

The sensitivity of the economic contribution of tourism to changes in these influencing factors is seldom analyzed, one important exception being Woltering ( 2012 , p. 249 ff.). Finally, all estimation approaches necessarily rely on reliable empirical data input about the number of visitors and their expenditures. Without those appropriate measures, even the most detailed, theoretically sound economic model would provide misleading results ( Tyrrell et al. 2001 , p. 94). Besides, Crompton et al. ( 2001 , p. 80 ff.) stress that “economic impact analysis is an inexact process, and output numbers should be regarded as a ‘best guess’ rather than as being inviolably accurate”. This quotation refers to the inherent problems of all economic valuation approaches, as does the lack of comparability of TSA and IO results: estimations of the economic effects of tourism should not be regarded as incontestable, because they are open to interpretation and misuse ( Crompton 2006 ). Consequently, a critical assessment of different economic valuation studies should take into account who is estimating which values using which approaches and models based on which assumptions and data input funded by whom. As issues of power and attempts to influence results can never be completely excluded it would be a task for a critical (economic) geography of tourism in the sense of Britton (1991) to deal with these related questions.

The following section focuses on one of the four basic requirements for any economic evaluation of tourism, variable expenditure. Along with visitor days spending behavior is the most influential driver of the economic effects of tourism and, thus, warrants special attention. Section 4 makes clear how the other influencing factors on the economic importance of tourism are addressed in this special issue.

3 Tourist expenditure: an overview of spending drivers

3.1 general issues.

The research history of tourists’ spending patterns is comparatively short. Wang and Davidson (2010) highlight that apart from a study undertaken in the 1970s ( Mak et al. 1977a , b ) the research community started focusing on the issue only in the 1990s. Most of these studies have been case studies ( Xiao, Smith 2006 ), so conclusions referring to a larger population cannot be drawn ( Gerring 2007 ). For a validation of such findings they can be triangulated by comparing results with those from case studies at different sites ( Decrop 1999 ). Brida, Scuderi (2012) , however, point out the problems of generalizing such empirical findings, as different models, dependent variables and regressors using inter alia different scales of measure are employed. Mak et al. (1977a) showed, furthermore, that different spending measurement methods (spending diaries vs. recall after their return home) lead to different results. Considering the caveats mentioned this chapter aims at outlining the most significant findings on expenditure patterns using a narrative review approach. Sampling of studies was based on a systematic research in the web of knowledge® provided by Thompson Reuters; search terms were “tourism* expenditure* determinants”, “tourism* expenditure behavior”, “tourism* expenditure”, combined with tourism forms (nature tourism, mountain tourism) in addition. We have included only destination-based studies in the analysis and omitted studies comprising expenditure in the areas of origin. Database entries up to December 2015 have been taken into account. 50 papers fulfilled the criteria and form the basis for the following evaluation.

To obtain a quick overview, it helps to systematize the predictor variables analyzed. Following Pouta et al. (2006) and Woltering (2007) , we systematize drivers of expenditure of the empirical studies into tourist-, travel- and destination-based variables analyzed. Omitted are macroeconomic variables such as the GDP or the price level in the countries of origin, destination and competing destinations (analyzed e.g. by Saayman, Saayman 2015 ); they are mainly relevant for explaining spending behavior of international tourists in different countries.

Tables 1 - 3 summarize the findings from previous studies regarding the statistical significance and the signs of the independent variables. The statistical methods used range from variance analyses to regression methods (OLS or quantile regression) or more advanced econometric techniques (double-hurdle, Heckit and similar methods). Moreover, the expenditure variable varies and takes the level or the log form ( Thrane 2014 ). Some studies apply several statistical models in the same paper to compare results (being usually but not in all cases quite similar); only the first mentioned model is included here. Studies differ, furthermore, regarding how they define spending (average per person or group, respectively per day or journey). Moreover, few studies not only measure spending at the destination itself but also in the country or region of origin (e.g. Alegre et al. 2011 ). In these cases, only expenditure at the destinations or total spending has been considered. Further studies do not use a single expenditure variable but differentiate spending in categories such as accommodation or food and beverages (e.g. Marcussen 2011 , Brida et al. 2013 ). If these studies include a total expenditure indicator only this variable is analyzed, if not, the variables considered are indicated.

Tourist-based drivers of visitor expenditure

Significant results (p < 0.05):+ = positive - = negative o = neutral

s. = significant categorical variable; n.s. = tested, but results not significant; p. (= partly)/m. (= mostly) s.: categorical variable with some but not all significant feature characteristics / … with significant feature characteristics except for one.

Significant results (p < 0.05): + = positive - = negative o = neutral; n.s. = tested, but results not significant; s. = significant categorical variable; p. (= partly)/m. (= mostly) s.: categorical variable with some but not all (not) significant feature characteristics / … with significant feature characteristics except for one.

d.v.: dependent variable; (1) group spending per stay; (1a) group spending per day; (2) individual spending per stay; (2a) individual spending per day; (3) not specified, probably group spending per day; (4) total travel spending per stay; (5) spending per day; (6) overnight; (7) dayvisitor

Destination-based drivers of visitor expenditure

Significant results (p < 0.05): + = positive - = negative o = neutral

s. = significant, categorical variable; n.s. = tested, but results not significant; p. (= partly) s. = categorical variable with some but not all significant feature

3.2 Tourist-based variables

Tourist-based variables relate to the travelers themselves and are based upon variables identified as decisive for consumption decisions in general ( Meffert 2000 ). They include socio-demographic variables such as age, gender, marital status, income, education and profession, and geographical variables reflecting the spatial and economic structure in the visitors’ region of origin ( Table 1 ). In many studies, age has been tested as a predictor variable with ambiguous results: in 11 out of 31 studies age was not found to influence spending in a statistically significant way, in seven studies spending depends positively on the age of visitors and four times a negative relation was found. The findings of Aguilo Perez, Juaneda Sampol (2000) , Pouta et al. (2006) , Thrane, Farstad (2011) or García-Sánchez et al. (2013) suggest that age might not be related to expenditure in a linear but curvilinear way. That means low spending is found in the youngest and the oldest age segments whereas high spenders are middle aged. Gender and marital status do not seem to predict spending in general ( Lawson 1994 ; Wang et al. 2006 ); this is reflected in the large share of non-significant results in the studies reviewed even though, for example, Mak et al. (1977b) found the latter variable to be significant. In contrast, income can generally be regarded as a reliable predictor ( Fish, Waggle 1996 ): consistent with economic theory the relationship between income level and tourism expenditure is positive in 21 out of 29 studies with Agarwal and Yochum (1999) , Downward, Lumsdon (2003) , Fredman (2008) as well as Thrane, Farstad (2011) reporting inelastic relations. This means with growing income, tourism expenditure increases as well but at a lower rate. Profession and level of education are only significant occasionally (possibly due to multicollinearities with the income variable), whereas the country of origin tends to be a good indicator of spending levels. The type of residential location does not seem to influence travel expenditure.

3.3 Travel-based variables

Table 2 summarizes the results of visitor expenditure studies regarding observable characteristics of the journey. The sign of group size seems to vary ambiguously: 10 out of 29 studies report positive signs, 14 studies negative signs, and two different signs according to the dependent variable ( Kozak et al. 2008 ; Marcussen 2011 ). The most straightforward explanation for the varying sign is the dependent variable. With group spending, expenditure tends to rise the larger the group, whereas with individual spending expenditure tends to fall due to cost-sharing.

The effect of travel length depends on the exact specification of the dependent variable as well. It is usually positive when total travel expenditure is analyzed. The influence of length of stay tends to be negative with per day expenditure as a dependent variable. Non-linear effects can be observed: for longer trips the generally positive relationship between length of stay and total expenditure becomes weaker, a diminishing positive effect was observed, theoretically explained by economies of scale ( Thrane, Farstad 2011 ; Aguilo Perez, Juaneda Sampol 2000 ; Roehl, Fesenmaier 1995 ).