Aéroport de Poitiers Biard

Poitiers biard airport.

IDEALLY LOCATED IN THE CENTRE-WEST OF FRANCE, BETWEEN PARIS AND BORDEAUX

Often, it is a stay at Futuroscope that incites the visitor to discover our destination. On the spot, you will discover our historical monuments, our animal parks, our nature, our gastronomy...

JUST FLY FROM LONDON-STANSTED TO POITIERS

REACH BARCELONE FROM POITIERS

From April 1st to October 25th, 2024 :

REACH EDINBURG FROM POITIERS

From June 1st to October26th, 2024 :

Access and parking

Poitiers Biard airport is easily accessible by car thanks to our access map and our car park. Situated 2km from the city centre and 12km from Futuroscope you can also get around thanks to the shuttles (project), taxis or by renting a car.

Located on the west ring road of Poitiers, halfway between Futuroscope and Poitiers Porte Sud, Poitiers Biard airport is only 10 minutes from the city centre and the train station.

Poitiers Biard airport has a car park open 24 hours a day, free of charge for the first 15 minutes.

In order to allow you to rent a car at the end of your flight, 5 car rental companies are present in the Poitiers Biard terminal hall.

Tourist sites

Do not wait anymore and live unforgettable experiences by setting out to explore “La Vienne, the land of Futuroscope”. Enjoy hundreds of activities throughout the year by discovering amazing and unusual sites.

When you arrive in Poitiers, you can choose between two taxi companies. Do not hesitate to book your taxi before your arrival by contacting directly one of the two taxi companies.

Hotels nearby, in the city centre and near Futuroscope.

Arcue ut vel commodo

Aliquam ut ex ut augue consectetur interdum endrerit imperdiet amet eleifend fringilla.

De Re Militari

The society for medieval military history.

- Society By-Laws

- Prizes – Past Winners

- JMMH Back Issues

- Memberships

- Membership Form

- JMMH Style Guide

- Conferences

- Primary Sources

- Upcoming Book Reviews

- Dissertations

The Battle of Tours-Poitiers Revisited

By William E. Watson

Providence: Studies in Western Civilization Vol.2 No.1 (1993)

Introduction: The Place of the Battle of Tours-Poitiers in Western Historiography

The Battle of Tours-Poitiers has long occupied a prominent position in Western historiography. The eighth- or ninth-century Carolingian Continuator of Fredegar wrote that Charles Martel won his famous victory over the Muslim invaders of the Frankish Kingdom Christo auxiliante.1 Eight centuries later, other clerical authors, the Bollandists, emphasized the miraculous nature of Charles’ victory in their writings.2 Beginning in the eighteenth century, however, non-clerical authors began to exaggerate the significance of the battle. Edward Gibbon, for example, wrote in 1776,

A victorious line of march had been prolonged above a thousand miles from the rock of Gibraltar to the bank of the Loire; the repetition of an equal space would have carried the Saracens to the confines of Poland and the Highlands of Scotland; the Rhine is not more impassable than the Nile or Euphrates, and the Arabian fleet might have sailed without a naval combat into the mouth of the Thames. Perhaps the interpretation of the Koran would now be taught in the schools of Oxford, and her pupils might demonstrate to a circumcised people the sanctity and truth of the revelation of Muhammad.3

Similarly, M. Guizot and Mme. Guizot de Witt wrote in 1869 that it was a struggle between East and West, South and North, Asia and Europe, the Gospel and the Koran; and we now say, on a general consideration of events, peoples, and ages, that the civilization of the world depended on it.4

Ernest Mercier provided the first objective assessment of the battle in an article in 1878, and Leon Levillain and Charles Samaran first attempted (unsuccessfully) to scientifically locate the site of the battle in an article in 1938.5 Maurice Mercier and Andre Seguin produced the first monograph devoted entirely to the battle in 1944, entitled Charles Martel et la bataille de Poitiers in which Latin and Arabic sources were used comparatively.6 Having examined the first part of Ibn Idhari’s Al-Bayan al-Mughrib fi Akhbar al-Maghrib, but not the second, Michel Baudot provided an inaccurate chronology for the Muslim invasion in a 1955 article entitled “Localisation et datation de la premiere victoire remportee par Charles Martel contre les musulmans.”7 Baudot’s incorrect dating of the battle as 733 A.D. has been employed to this day by those unfamiliar with the sources. A revision of the previous generally-held views of the battle has occurred over the past several decades as well, resulting in the conscious minimizing of the significance of Tours-Poitiers in the textbooks of medieval European and Islamic history.8

In this essay I intend to suggest answers to the four most crucial questions concerning the Battle of Tours-Poitiers which have not been answered sufficiently by Frankish experts or Islamicists. What motivated the Muslims to move north of the Pyrenees? What do the Latin and Arabic sources reveal about what transpired in the course of the battle? Precisely when and where did the encounter occur? Can we attach a macrohistorical significance to the battle?

Historical and Geographical Motives for Muslim Operations North of the Pyrenees

Early Roman authors such as Caesar and Strabo noted the distinctiveness of Aquitaine in comparison to the rest of Gaul. Caesar’s statement in the Gallic War concerning the divisibility of Gaul into three parts (or peoples – the Belgae, Aquitani, and Galli (Celtae]) is evidence that ethnographic differences were apparent in the first century before Christ.9 No definite physical boundaries delineated Aquitaine from other regions of Gaul, but it is clear that Aquitaine was perceived as a coherent unit in the early eighth century A.D. This territorial coherence partly explains the emergence of a princely tradition in Aquitaine, a tradition which was notably absent from the Languedoc region to the south. Michel Rouche calls the years 719-21, “the apogee of independent Aquitaine,” as a result of the degree of self determination exercised by the Aquitanian princely family at Toulouse.10

The Languedoc region was largely comprised of the old Roman province of Septimania, named for the veterans of the seventh legion who settled in the vicinity of Beziers.11 This region did not possess the indigenous political and ethnic uniformity which Aquitaine possessed. In the eighth century, before the Muslim invasions, it was an underpopulated, culturally insular, and economically stagnant area which possessed a few notable monasteries (such as Aniane), and two important frontier forts (Carcassone and Nimes), as well as a city of some size (Narbonne). Although politically more coherent than Languedoc, Aquitaine was as economically insular, judging by the lack of archaeological evidence from the seventh and eighth centuries of trade with the north or with the Mediterranean ports.12

In previous centuries these areas were ruled by the Romans, whose economy bound much of Gaul to the Iberian peninsula. In addition to economic ties which had existed since Roman days, politico-military ties connecting southern Gaul to Iberia were reinforced by the Visigothic warriors who settled Aquitaine, Languedoc, and Iberia in the fifth century. They suffered a setback, however, when the dominant power in northern Gaul, the Frankish army of Clovis, crossed the Loire and decisively defeated them at Vouille, killing their king (Alaric III) and wresting Toulouse from them. In addition, Narbonne was taken from them by Burgundian allies of the Franks.13

Narbonne was subsequently reacquired by the Visigoths with the help of the Ostrogothic king Theodoric, whose grandson Amalaric was the heir to the Visigothic throne. Narbonne was then the capital of the Visigothic kingdom for twenty years (511-31), and during this time the Visigothic realm has been described as “an Ostrogothic dependency, ruled by Ostrogothic governors.”14 The Visigoths were pushed south of the Pyrenees by the Franks a few years after Theodoric died (526), and the Iberian peninsula was henceforth the center of the Visigothic kingdom.

Septimania remained a frontier province of the Visigoths, but possession of it was contested on several occasions by the Franks, and the Gallic inhabitants periodically revolted against the central authority in Toledo.15 The Visigoths who resided in Septimania from the third decade of the sixth century until the termination of the monarchy were a small military and ecclesiastical elite. The members of this elite resided in Septimania for very short periods of time, which indicates that service to the king north of the Pyrenees was not as desirable as service in Iberia. The high rate of attrition of the Gothic residents has been attributed in part to the hostility of the Gallic population towards the Visigoths. Ecclesiastical ties between Septimania and Iberia, however, were strengthened after the conver–sion of the Visigoths from Arianism to Catholic orthodoxy in 589 under King Recared, and this is reflected by the preponderance of Gothic bishops in Septimanian bishoprics.16

By virtue of the Roman and Visigothic ties which bound Iberia and the Languedoc region together, the lands north of the Pyrenees could potentially be threatened by problems faced by the Visigoths within Iberia proper. This was indeed the case in 711 when the Visigothic army was defeated by a North African Muslim army comprised of Arabs and Berbers commanded by the Umayyad general (and manumitted slave) Tariq Ibn Ziyad. Although the accuracy of many of the details of the Muslim invasion of Iberia recorded by later Arabic historians has been questioned by many scholars, we know that the backbone of the Visigothic army was defeated in one fateful battle on the Rio Barbate, and that the Visigothic king, Roderick (710-11), was killed in the action.17

The initial wave of invasion in the spring and summer months of 711 was followed by a larger force commanded by Tariq’s former master, the Umayyad amir Musa Ibn Nusayr. With the defeat of the regular Visigothic army and the death of the monarch, many Visigoths lost their resolve to resist the invading Muslim forces. Those urban centers which did resist Muslim occupation were systematically destroyed with the help of certain disaffected Visigothic nobles and local Jewish communities which had suffered under economic and social restrictions placed on them by the later Visigothic kings.18

The authority of the Umayyad Caliphate of Damascus was firmly established in the peninsula by Musa’s army, and was accom–panied by the settlement of many Berbers and a small Arab military/religious elite who imported Arabic/Islamic cultural forms into Iberia. The Iberian peninsula was reorganized as the province of al–Andalus and was, in this early period of Muslim settlement, a distant, rather insignificant outpost of the Umayyad Caliphate, an Arab empire which stretched from Iran to the Atlantic, and whose capital was the bustling Syrian city of Damascus. The name “al-Andalus” is generally believed to be derived from the Vandals, the ephemeral early Germanic tribe who stayed for a time in southern Iberia before continuing their wanderings, ultimately settling on the North African coast.

Some of the Visigoths who refused to submit to the Muslims fled to the mountainous region of Asturias in the northwestern section of the peninsula, from which region came the strongest early resistance to the Muslims, such as the successes of Pelayo (ca. 717-18) and of King Alfonso I (ca. 739-57). Other Visigothic nobles made separate treaties with the Muslims. Such is the case with Prince Theodemir of Murcia, whose treaty with the Muslims in 713 allowed him to retain his principality as a Christian entity under Islamic suzerainty. Subse–quently, Arabic authors invariably referred to Murcia as “Tudmir” (an Arabic transliteration of the prince’s name), in deference to Theodemir.19 Aside from Asturias, which was never taken by the Muslims, the only other region of the Visigothic kingdom not taken by the time of Musa’s departure for Damascus in 714, was the province of Septimania.

Within Septimania, Visigothic supporters of the former king, Witiza (700-10), had held sway since the reign of Roderick, when they acknowledged the legitimacy of Witiza’s son Akhila over Roderick. Although some of the partisans of the House of Witiza accepted Islamic suzerainty over Septimania in 714 (including Witiza’s three sons, who were guaranteed provisions similar to those of Theodemir), many of the Septimanian Visigoths revolted against the Umayyads and made one Ardo their king.20

It was probably in response to this action that the first trans-Pyrenean expeditions were launched by the Muslims in 717 and 719. After Musa left for Damascus in 714, his son Abd al-Aziz was chiefly occupied with the further consolidation of al-Andalus until his assassination in 716. He was too concerned with Andalusi problems to be concerned with Ardo.21 In 717, however, Musa’s successor as amir, al–Hurr ath-Thaqafi, led a small raiding party into Septimania, the purpose of which was simply to reconnoiter the region. The next Muslim expedition into Septimania was put off for two years because ethnic tension between Arabs and Berbers in al-Andalus kept the Umayyad authorities preoccupied with internal difficulties.

The reign of Ardo and the independence of the Septimanian Visigoths, however, ended in 719-720 when amir as-Samh Ibn Malik al-Khawlani captured the city of Narbonne for the Umayyad Caliphate. The city was subsequently transformed into an Islamic city and was brought into the political orbit of the Umayyad Caliphate and the cultural orbit of the Andalusi Muslims who settled there. Although as-Samh died before the walls of Toulouse in 721, the Visigothic garrisons holding the key Languedocian forts at Carcassonne and Nimes were subdued in 724 by amir Anbasah Ibn Suhaym al-Kalbi. The conquests definitively ended the Visigothic kingdom and gave the Muslims several bases for further expansion to the north. Indeed, in the very next year after the fall of Carcassonne and Nimes, Anbasah engaged in daring operations far to the north in the Rhone valley as far as Autun.

After Anbasah died suddenly in 725, six amirs followed him in rapid succession. Some of the Muslims of northern Iberia separated themselves from the Umayyad province of al-Andalus during the five-year period (725-30) in which the Andalusi leadership was chiefly occupied with an internal power struggle.22 The Languedocian Muslims were likely affected by the confusion in al-Andalus, as well, although it is not apparent that they wished to break with the Umayyad province.23 A Berber leader named Munusa based at Llivia in Cerdagne, however, did indeed wish to assert his independence from al-Andalus. To this end, he contracted an alliance in 729 with Prince Eudo of Aquitaine in order to strengthen his position. Michel Rouche suggests that the treaty between Munusa and Eudo was similar to the treaties of capitulation signed by Visigothic Christian leaders during the Muslim invasion of the Visigothic kingdom.24

Eudo had earlier entered into alliance with the Merovingian Franks, and some Frankish chroniclers noted that Eudo’s alliance with Munusa was viewed by the Merovingian major domus Charles as an attempt to abrogate the Frankish Aquitanian treaty (although this is by no means certain).25 Both Munusa and Eudo, however, soon paid for their alliance. The Frankish army invaded Aquitaine on two separate occasions in 731, capturing a great deal of booty and decisively humbling Eudo.26

The principal Latin source for the alliance, the Mozarabic Chronicle of 754 attests that Eudo’s daughter was given in marriage to Munusa to solidify the alliance.27 According to this account, the amir of al-Andalus soon invaded the region held by Munusa, causing the rebellious Berber to commit suicide (and Eudo’s unfortunate daugh–ter was sent along with the severed head of Munusa to Damascus).28 Some of this is corroborated by al-Maqqari, who writes that “al-–Haytham Ibn Ubayid al-Kinani attacked the land of Munusa and conquered it …he [al-Haytham] died in the year 113 [730].”29 Despite his success against Munusa, al-Haytham’s tenure as amir of al-Andalus was short-lived, and he was unable to decisively suppress the desire for independence on the part of northern Andalusi Muslims. The border region between al-Andalus and the Principality of Aquitaine remained a problem for the Umayyad leadership for decades after Munusa’s defeat.

The power struggle in al-Andalus was resolved in 730 when Abd ar-Rahman was determined to straighten out the uncertain political situation along his northern border, and he quickly prepared an expedition aimed at Aquitaine, to ensure that the Aquitanian prince would no longer be capable of tempting northern Andulusi Muslims from the Umayyad fold. Rather than being merely a raid for plunder in the dar al-Harb, or an attempt to conquer the entire Christian world, the northern expedition of Abd ar-Rahman was designed to eliminate the strategic threat that Eudo of Aquitaine posed to the Andalusi Muslims.

The Activities of ‘Abd ar-Rahman according to the Latin and Arabic Sources

‘Abd ar-Rahman set off in 732, marching in a northwestern direction through the Pyrenees at the Roncevaux Pass. A decade earlier, as-Samh took the most direct route from Narbonne to the Aquintanian capital at Toulouse. Undoubtedly ‘Abd ar-Rahman’s decision to take a northwestern route in 732 was partly based on the knowledge that as-Samh had failed before the walls of Toulouse. It is also possible that ‘Abd ar-Rahman did not trust the loyalty of the Muslims in the vicinity of Narbonne. Given the fact that north Iberian Muslims had rebelled against the Umayyad province under Manusa prior to 732, ‘Abd ar-Rahman may have been aware that the Muslims of Narbonne would not be particularly cooperative when he passed through with his army.

The expedition is recorded in a number of Latin and Arabic sources, and both types of sources distinguish between two phases in the invasion: the Muslim drive to Bordeaux, resulting in the defeat of Eudo’s Aquitanian army, and the Muslim drive towards Tours, resulting in the defeat of ‘Abd ar-Rahman’s army by the Franks between Poitiers and Tours. According to the earliest Arabic source for the campaign, the Futuh Misr of Ibn ‘Abd al-Hakam (c. 803-71), ‘Abd ar Rahman set off on the military expedition against “the most distant enemies of al-Andalus ” because “he was a virtuous man.”30 He gained a swift and decisive victory over Eudo’s army before Bordeaux, and then sacked the city. Ibn ‘Abd al-Hakam reports that’Abd ar-Rahman “took a great deal of booty,” including gem- and pearl–encrusted golden objects.31

The destruction of Bordeaux is described in the previously mentioned common corpus of material found in two Latin monastic chronicles composed in the ninth century; the Annals of Aniane and the Chronicle of Moissac, as well as the Chronicle of Fredegar. The Annals of Aniane and the Chronicle of Moissac contain the same text, and call ‘Abd ar-Rahman “Abderaman, the king of Spain.” According to this account, ‘Abd ar-Rahman marched “with a large army of Saracens” from Pamplona through the Pyrenees, and occupied Bordeaux. Eudo then gathered his army to meet the Muslims on the banks of the Dordogne, across the Garonne, apparently arriving too late to save Bordeaux.32

Confusing ‘Abd ar-Rahman with Munusa, the Chronicle of Fredegar reports that Eudo lured the Muslims north as the result of an alliance between the Andalusi Muslims and the Aquintanian prince (who here receives the less illustrious title of duke). The Chronicle of Fredegar states that Bordeaux’s churches were burned and its inhabitants slain by the Muslims.33

The ensuing Battle of Bordeaux is recorded in the Annals of Aniane and the Chronicle of Moissac, which contain the same account: the Aquintanian army was decisively defeated and incurred many casualties, causing Eudo to flee north into the Frankish kingdom.34 The Mozarabic Chronicle of 754 also mentions the Battle of Bordeaux, and stated that the Aquitanian casualties in the encounter were so high that “only God knows how many died and [simply] vanished.”35

Following their victory over Eudo’s army, the Muslims ad–vanced through Aquitaine, hoping to catch Eudo. The Annals of Aniane and the Chronicle of Fredegar describe the general depredations that attended the Muslim advance northward through Aquitaine, and the Mozarabic Chronicle of 754 mentions that the Muslims specifically destroyed “palaces” (i.e. “forts”) and burned churches on the way, in the likely anticipation that they were eliminating future sites of resistance and demoralizing the enemy.36 The Chronicle of Fredegar reports that the Muslims specifically targeted the Church of St. Hilary in Poitiers for destruction on their northward advance.37 At some point in the campaign, the Muslims became aware of the existence of the wealthy shrine of St. Martin at Tours, and they intended to sack it. The large amount of plunder taken at Bordeaux described by Ibn ‘Abd al-Hakam was undoubtedly being continually enlarged by the Muslims in Aquitaine (for example, at Poitiers), and this added weight probably slowed their progress.

In the meantime, Eudo had managed to alert the Merovingian major domus Charles of the Muslim threat, and Charles assembled the Frankish army to meet ‘Abd ar-Rahman’s force before it reached Tours. From Charles’ perspective, the Muslims were not only threatening to damage or destroy the Frankish kingdom’s most sacred shrine (and also one of the greatest in all Latin Christendom), but Abd ar-Rahman was challenging the integrity of the regnum Francorum. As major domus of the Merovingian kingdom, and the strongest and most charismatic of its princes in an age when the Merovingian “Long–haired Kings” were said to have become “Do-nothing Kings,” it was natural that Charles would be the man to lead the Frankish army in the field against the Muslims.

The resulting battle between Charles and ‘Abd ar-Rahman is described in a large number of Latin and Arabic sources. Ibn ‘Abd al-Hakam refers to the northward extension of ‘Abd ar-Rahman’s operation into the Frankish kingdom as a separate campaign: ‘He then led another military expedition against the Franks.”38 Ibn Abd al-Hakam says: “He went out as a ghazi, and he [and his companions] were martyred for the faith.”39 The greatest medieval Arabic historian, ‘Izz ad-Din Ibn al-Athir (1160-1233), writes of the battle in his annalistic history of the world, al-Kamil fi t’ Ta’rikh. Like Ibn Abd al-Hakam, Ibn al-Athir writes that ‘Abd ar-Rahman went out ghaziyan (“going out as a ghazi”) into the land of the Franks.40

When one is described as a ghazi in Islamic literature, one can either be engaged in a border war for Islam waged against “infidels,” or engaged in simple piratical raids, a continuation of the ancient Bedouin practice of brigandage into the Islamic era.41 One can imagine that both aspects of the ghazi ethic were present in ‘Abd-ar Rahman’s army and both Ibn ‘Abd al-Hakam and Ibn al-Athir describe ‘Abd ar-Rahman as a sincere, just Muslim.42 Again following Ibn ‘Abd al-Hakam, Ibn al-Athir writes that ‘Abd ar-Rahman and his companions died in the battle as shuhada’i, “martyrs for the faith.”43

This idea is reiterated by the thirteenth-century Moroccan au–thor Ibn Idhari al-Marrakushi, who mentioned the battle in his history of theMaghrib, al-Bayan al-Mughrib fi Akhbaral-Maghrib. According to Ibn Idhari, ‘Abd ar-Rahman and many of his men found martyrdom on the balat ash-Shuhada’i (“the path of the martyrs).44 This balat, or “path” was identified by Levi-Provencal and others with the Roman road connecting Poitiers and Tours.45

The Franks intercepted the Muslims on this road a short distance from Poitiers, at a site known as Moussais-la-bataille. The details of this encounter, herein called the Battle of Tours/Poitiers, are contained exclusively in Latin sources, as the Arabic sources are silent on the specific events of the battle. The Annals of Aniane and the Chronicle of Moissac contain the same account: Charles and his large army met the Muslims in suburbio Pictavensi (“in the vicinity of Poitiers”) and defeated them in a great slaughter, driving the survivors back to al-Andalus.46 The Chronicle of Fredegar contains a more substantial account of the battle: the Franks killed ‘Abd ar-Rahman in the operation and overran the tents of the Muslim camp, presumably to recapture the treasure that had been taken from the Aquitanian churches.47

The Mozarabic Chronicle of 754 describes the battle in greater detail than any other Latin or Arabic source: the Franks drew themselves into a large infantry square, so that they were “like an immovable wall” and a “glacier.”48 The Muslims threw themselves at the Frankish square in fruitless attempts to break the formation, and many Muslims were cut down by Frankish swordsmen.49 The Muslim assault, however, ceased when night fell. The discipline and resolve of the Franks was apparently too much for the Muslims, as Frankish scouts discovered on the following morning that the Muslim camp had been abandoned in haste during the night, with a great deal of plunder having been left behind in the tents.50

The Dating of the Battle

Neither the Mozarabic Chronicle nor the Chronicle of Fredegar date the battle, but the event is recorded sub anno 732 in the Annals of Aniane and the Chronicle of Moissac. The battle is also recorded in brief notices in several other monastic chronicles. The Annals of St. Amand report sub anno 732: Karlus bellum habuit contra Saracinos in mense Octobri.51 The Annales Petaviani are more specific, as die sabbato is added to the same account.52 Both the Annals of Lorsch and the Annals of Alamannia report sub anno 732: Karolus pugnavit contra Saracenos die sabbato ad Pectavis.53 Thus, there is a consensus in most of the Latin sources that the battle occurred on a Saturday in October, 732.

Two of the Arabic sources also place the battle in 732. Although he does not mention his sources, Ibn al-Athir writes in al-Kamil that some Arabic chroniclers had placed the battle in 113 A.H. (731 A.D.), but that 114 A.H. (732 A.D.) is the correct date.54 Ibn Idhari states in the first part of al-Bayan that the battle occurred in 115 A.H. (733 A.D.), but he corrects the date in the second part of his work to Ramadan 114 (October-November 732 A.D.).55 Considering this evidence, Levi-Provençal argued for a date between October 25 and October 31, 732, and Michel Rouche has argued specifically for October 25, 732.56 This particular date is acceptable when one recognizes that the evidence contained in the Latin and Arabic chronicles does converge rather clearly on this point.

Conclusion: The Macrohistorical Significance of the Battle

After examining the motives for the Muslim drive north of the Pyrenees, one can attach a macrohistorical significance to the encounter between the Franks and Andalusi Muslims at Tours-Poitiers, especially when one considers the attention paid to the Franks in Arabic literature and the successful expansion of Muslims elsewhere in the medieval period. Lured on by the promise of plunder and by a desire to catch Eudo, as well as a desire to defeat more foes of Islam, ‘Abd ar-Rahman extended his campaign towards the regnum Francorum. His invasion was neither simply a raid nor part of a grand scheme to conquer all Christendom, it was a failed attempt to elimi–nate a strategic threat located north of the Andalusi border. Moreover, the battle did not decide the outcome of the Christian-Muslim struggle in Francia. Rather, it brought a determined new participant into the field of combat, the Frankish army, which launched an offensive against the remaining Muslin bases to the south only a few years after Charles won his victory at Tours-Poitiers and earned himself the title Martel (“Hammer”).57

The Arabs attached a greater significance to their confrontation with the Franks than with any other European people save the Byzantine Greeks. We find a great many references to the Franks in medieval Arabic literature. The Baghdadi geographer al-Masudi (d. 956), for instance, preserved a list of sixteen Frankish kings (examined by Bernard Lewis), as well as various references to Frankish-Arab military contacts in his Muruj.58

The Iraqi historian Ibn al-Athir (d. 1233) included many references to the Franks in al-Kamil fi ‘t-Ta’rikh and he distinguished between the Latin- and Greek-rite Christians of southern Italy as “those from ar-Rum (Byzantium) and those from al-Franj (the Franks).”59 The word “Franj ” entered the Arabic language in the eighth century with the meaning of “Franks” (and later, “French–men”) in particular, and of “Europeans” in general. The impact of “the Franks” has persisted in Modern Standard Arabic (Fusha): the verb tafarnaja (root=f-r-n-j) means “to become Europeanized;” the adjective mutafarnij means “Europeanized;” al-Ifranj means “the Europeans;” Firanja and bilad al-Firanj mean “Europe,” and so on.

There is clearly some justification for ranking Tours-Poitiers among the most significant events in Frankish history when one considers the result of the battle in light of the remarkable record of the successful establishment by Muslims of Islamic political and cultural dominance along the entire eastern and southern rim of the former Christian, Roman world. The rapid Muslim conquest of Palestine, Syria, Egypt and the North African coast all the way to Morocco in the seventh century resulted in the permanent imposition by force of Islamic culture onto a previously Christian and largely non-Arab base. The Visigothic kingdom fell to Muslim conquerors in a single battle on the Rio Barbate in 711, and the Hispanic Christian population took seven long centuries to regain control of the Iberian peninsula. The Reconquista, of course, was completed in 1492, only months before Columbus received official backing for his fateful voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. Had Charles Martel suffered at Tours-Poitiers the fate of King Roderick at the Rio Barbate, it is doubtful that a “do-nothing” sovereign of the Merovingian realm could have later succeeded where his talented major domus had failed. Indeed, as Charles was the progenitor of the Carolingian line of Frankish rulers and grandfather of Charlemagne, one can even say with a degree of certainty that the subsequent history of the West would have proceeded along vastly different currents had ‘Abd ar-Rahman been victorious at Tours-Poitiers in 732.

1.The Fourth Book of the Chronicle of Fredegar with its Continuations, ed. J. M. Wallace–Hadrill (London, 1960), 90.

2. Maurice Mercier and Andre Seguin, Charles Martel et la bataille de Poitiers (Paris, 1944), 55-56.

3. Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, (New York, 1974), 6:16.

4. M. Guizot and Mme. Guizot De Witt, A History of France (New York,1869),1:154.

5. Ernest Mercier, “La bataille de Poitiers et les vraies causes du recul de l’invasion arabe,” Revue Historique 7 (1878),1-13; Leon Levillain and Charles Samaran, “Sur le lieu et la date de la bataille dite de Poitiers de 732, ” Bibliotheque de 1’Ecole de Chartres 99 (1938), 243-67.

6. Evariste Levi-Provencal wrote (I believe unjustly) in Histoire de I’Espagne omusulmane (Paris, 1950,1: 60, n. 3: “une etude recente, mais sans grande portee.”

7. Michel Baudot, “Localisation et datation de la premiere victoire remportee par Charles Martel contre les Musulmans,” Memoires et documents publies par la Societe de 1’Ecole de Chartres 12, i (1955), 93-105.

8. Baudot’s article was first brought to the attention of English-speaking scholars by Lynn White, Jr., who based some of his theories in Medieval Technology and Social Change (Oxford 1962) upon Baudot’s misinterpretations. See, for example, White’s comments on the stirrup on 2-12. Michel Rouche challenged Baudotin 1968 article entitled “Les Aquitains ont-ils trahi avant la bataille de Poitiers?,” Le Moyen Age 74 (1968),5-26. See also the comments of Donald A. Bullough in “Europae Pater: Charlemagne and his achievement in the light of recent scholarship,” English Historical Review 85 (1970), 73 and 85; Bernard S. Bachrach, “Charles Martel, Mounted Shock Combat, the Stirrup, and Feudalism,” Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History ed. William M. Bowsky, 7 (1970), 50-51.

9. Michel Rouche, L’Aquitaine des Visigoth aux Arabes. 418-781: Naissance d’une region (Paris, 1979), 11-15.

10. Ibid, 113.

11. Edward James, “Septimania and its Frontier: An Archaeological Approach,” in James, ed. Visigothic Spain: New Approaches (Oxford, 1980), 223.

12. Ibid, 226, 239-40.

13. Joseph F. O’Callaghan, A History of Medieval Spain (Ithaca, 1975), 41.

15. E. A. Thompson, The Goths in Spain (Oxford, 1969), 216, 218-28.

16. Ibid, 226; James, “Septimania,” 225.

17. Thomas F. Glick, Islamic and Christian Spain in the Middle Ages (Princeton, 1979), 14 and 32.

18. Eliyahu Ashtor, The Jews of Moslem Spain (Philadelphia, n.d.), 10-24; Bernard S. Bachrach, Early Medieval Jewish Policy in Western Europe (Minneapolis, 1977), 24-26; Allan H. Cutler and Helen E. Cutler, The Jew as Ally of the Muslim (Notre Dame, 1986), 93; Evariste Levi-Provencal, Histoire 1:80-81; William Montgomery Watt and Pierre Cachia, A History of Islamic Spain (Edinburgh, 1977), 12.

19. Watt and Cachia, History, 17,19, 25; Glick, Islamic and Christian Spain, 14.

20. Ibid, 12; Thompson, The Goths, 251; Arthur Zuckerman, A Jewish Princedom in Feudal France, 768-900 (New York, 1972), 11.

21. Watt and Cachia, History, 15.

22. Levi-Provencal, Histoire, 1:60-61, n.l; Michel Rouche, L’Aquitaine,113-14; Idem, “Les Aquitains, ” 5-26.

24. Rouche, “Les Aquitains,” 11.

25. Rouche, L’Aquitaine, 113.

26. Ibid, 113.

27. Cronica Mozarabe de 754, ed. Jose Eduardo Lopez Pereira (Zaragoza, 1980), 96-99.

29. AI-Maqqari, Analectes sur 1’histoire et la litterature des Arabes d’Espagne par al Makkari, ed. R. Dozy, G. Dugat, L. Krehl, and W. Wright (Amsterdam, 1967), 216.

30. Ibn’Abd al-Hakam, Futuh Misr, ed. Charles C. Torrey (New Haven, 1922), 216.

32. Annals of Aniane, in Claude Devic and Jean Vaissette, eds. Histoire generale du Languedoc (Toulouse, 1875), 2:2:5; Chronicle of Moissac, MGH SS 1:291.

33. Chronicle of Fredegar, ed. J.M. Wallace-Hadrill, 89-90.

34. Annals of Aniane, 2:2:5; Chronicle of Moissac MGH SS 1:291.

35. Cronica Mozarabe, 98-99.

36. Annals of Aniane, 2:2:5; Chronicle of Moissac, MGH SS 1:291. Cronica Mozarabe, 98-9.

37. Chronicle of Fredegar, 89-90.

38. Ibn ‘Abd al-Hakam, Futuh Misr, 217.

40. Ibn al-Athir, AI-Kamil fi t-Ta’rikh (Beirut, 1985), 5:174.

41. I. Melikoff, “Ghazi;” Encyclopaedia of Islam, ser. 2,1043-44.

42. Ibn’Abd al-Hakam, Futuh Misr, 217, Ibn al-Athir, AI-Kamil, 5:174.

43. Ibn al-Athir, AI-Kamil, 5:174.

44. Ibn Idhari al-Marrakushi, Histoire de 1’Afrique et de I’Espagne intitulee al-bayano 1–Maghrib, ed. E. Fagnan (Algiers, 1901), 1:49.

45. Levi-Provencal, Histoire,1:62; Mercier and Sequin, Charles Martel, 17-19.

46. Annals of Aniane, 2:2:5; Chronicle of Moissac, MGH SS 1:291.

47. Chronicle of Fredegar, 89-91.

48. Cronica Mozarabe,100-01.

51. Annals of St. Amand, MGH SS 1:8.

52. Annales Petaviani, MGH SS 1:9.

53. Annals of Lorsch, MGH SS 1:24; Annals of Alemannia, MGH SS 1:24.

54. Ibn al-Athir, AI-Kamil, 5:174.

55. Ibn Idhari, Histoire,1:49; 2:39.

56. Levi-Provencal, Histoire,1:62; Rouche, “Les Aquitains;” 26.

57. The purpose of Charles’ subsequent drive south along the Rhone River in 737 was to dislodge the Muslims from their bases at Lyon, Avignon, Carcassonne, and Nimes. While he decisively established Frankish supremacy in the Rhone valley, Charles was unable to capture Narbonne. Eventually, his son Pepin III (“the Short”) succeeded in taking Narbonne with the assistance of the indigenous Christian population (759). Later, however, after Carolingian power waned in the second half of the ninth century, yet another Andulusi Muslim base was estab–lished in Francia at a coastal Provencal site called Fraxinetum in the Latin sources (jabal al-Qilal in the Arabic sources). The successful establishment of this preda–tory base in Provence in 888 and its long duration (almost a century) was a sign of how ineffective local Christian resistance was by the late ninth century in the former Carolingian realm. Without the Frankish army to assist them local military leaders were finally able to push out this last Muslim base under the skillful leadership of Count William of Arles (thereafter known as “the Liberator”) in 972. See especially Charles Pellat, “Les Sarrasins en Avignon,” in En terre d’Islam 1944/ 4 (Lyon, 1944), reprinted in Etudes sur 1’histoire socioculturelle de 1’Islam (London, 1976); William E. Watson, “The Hammer and the Crescent: Contacts Between Andulusi Muslims, Franks, and Their Successors in Three Waves of Muslim Expansion into Francia,” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 1990), 61-97; Gonzague De Rey, Les invasions des sarrasins en Provence (Marseilles, 1971); Philippe Senac, Provence et piraterie sarrasine (Paris, 1982); Bruno Luppi, l Sarraceni in Provenza in Liguria a nelle Alpi occidentale (Bordighera,1973); Stephen Weinberger, “Peasant Households in Provence: ca. 800-1100,” in Speculum 48 (1973).

58. Bernard Lewis, “Mas udi on the Kings of the Franks;” Al-Mas udi Millennary Commemoration Volume (Aligarh, 1960), 7-10; Idem, The Muslim Discovery of Europe (New York, 1982)139-40.

59. Ibn al-Athir, Al-Kamil, 6:520-21.

This article was first published in Providence: Studies in Western Civilization v.2 (1993). We thank the Department of Western Civilization at the the University of Providence and William Watson for their permission to republish this article.

Comments are closed.

- Search for:

Recent Posts

- Matthew P. McDiarmaid and James A.C. Stevenson (eds), Barbour’s Bruce: A! Fredome is a Noble Thing! Volumes I, II, & III (Reviewer- Simon Egan)

- Michael S. Fulton. Contest for Egypt. The Collapse of the Fatimid Caliphate, the Ebb of Crusader Influence, and the Rise of Saladin (Reviewer- Lucas McMahon)

- Brian Todd Carey, Joshua B. Allfree, John Cairns, Warfare in the Age of the Crusades: The Latin East (Reviewer- Nicholas Wallace)

Shopping Cart

Your shopping cart.

- Avant votre départ, vérifier les documents obligatoires à fournir aux autorités locales : retrouvez toutes les informations sur le site internet de la compagnie Ryanair

- Ouverture des comptoirs d'enregistrement 2h avant les départs excepté pour les vols à destination de Marrakech ouverture 2h30 avant les départs

Attention javascript est désactivé sur votre navigateur, vous devez l'activer pour profiter de toutes les fonctionnalités du site.

RESERVER UN VOYAGE avec ANNECY MONT-BLANC

- Carte des destinations

- Informations vols Réguliers

- Informations vols Vacances

- Compagnies Aériennes

- Situation et Accès

- Taxis & Transports en commun

- Voitures de location

- Consignes de sûreté

- Enregistrement et Bagages

- Personnes à Mobilité Réduite

- Enfants non accompagnés

- Voyage avec un animal

- Service client - bagages

- Commerces et Services

- Les Châteaux de la Loire

Vols & Destinations

The making of a world historical moment: The Battle of Tours (732/3) in the nineteenth century

- Original Article

- Published: 17 July 2019

- Volume 10 , pages 206–218, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- James T. Palmer 1

448 Accesses

5 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The Battle of Tours (or Poitiers) in 732/3 is frequently cited as a turning point in world history, when the advance of Muslim Arabs was decisively halted by the Christian army of Frankish mayor Charles Martel. Yet the battle and its reputation seem relatively modest in the earliest sources, with little sense that conquest or religious tensions were key issues. This paper explores how the importance of the battle became amplified in grand historical narratives produced across Europe and in the U.S. in the nineteenth century, as historians contributed to arguments about national and religious identities. It highlights in particular the ways that historians, from Michelet to Oman, were led by their own dispositions in speculating about what could have happened had the result been different. In the process, although their interpretations often differed, debate about the battle generated the legend popular in modern political discourse.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Why populism?

The Colonial Matrix of Power

The Godfather as Philosophy: Honor, Power, Family, and Evil

Later writers would also have the Spanish nationalist work of Conde ( 1820 –1).

‘Saracens’ is the common pejorative Latin term for Arabs from Late Antiquity: see Tolan ( 2002 ).

‘Europeans’ is a highly unusual collective term in this period.

See Price ( 2008 , 88–90) and Wood ( 2013 , 188–9).

Monod later wrote a biographical study of Michelet: Monod ( 1923 ).

Borgolte, M. 2006. Christen, Juden, Muselmanen. Die Erben der Antike und der Aufstieg des Abendlandes 300 bis 1400 n. Chr. Munich, Germany: Siedler.

Breysig, T. 1869. Jahrbücher des fränkischen Reiches 714–741: Die Zeit Karls Martells . Leipzig, Germany: Dunder & Humblot.

Google Scholar

Brunner, H. 1887. Der Reiterdienst und die Anfänge des Lehnwesens. Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte, Germanische Abteilung 8: 1–38.

Article Google Scholar

Burckhardt, J. 1843 . Questions alioquot Caroli Martelli historiam illustrantes. Basel, Germany: Mast.

Cardonne, D.D. 1765. Histoire de l’Afrique et de l’Espagne sous la domination des Arabes . Paris, Franc: Saillant.

Collins, R. 1989. The Arab Conquest of Spain 710–797 . Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Conde, J. 1820–1. Historia de la Dominación de los Árabes en España . Madrid, Spain: Garcia.

Creasy, E. 1851. The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World: From Marathon to Waterloo . New York: Harper & Brothers.

Davis, W.S. 1913. Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources , 2 vols. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Davis, W.S. 1926. Europe since Waterloo. New York: Century.

Duchesne, L. 1886. Le Liber Pontificalis . Paris, France: Thorin.

Fouracre, P. 2000. The Age of Charles Martel . Harlow, UK: Longman.

Gibbon, E. [1788] 1906. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire , 12 vols. Ed. J. B. Bury. New York: DeFau.

Gil, J. 1973. Corpus Scriptorum Muzarabicorum . Madrid, Spain: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas.

Haaren, J.H., and A. B. Poland. 1904. Famous Men of the Middle Ages. New York: American Book Company.

Hallam, H. [1818] 1900. History of Europe during the Middle Ages. New York: Colonial Press.

Halphen, L. 1926. Les barbares. Des grandes invasions aux conquêtes Turques du XI e siècle . Paris: Alcan.

Hauck, A. [1887] 1898. Kirchengeschichte Deutschlands 1 . Leipzig, Germany: Hinrischs’sche Buchhandlung.

Katz, E. 1889. Annalium Laureshamensium editio emendata . Sankt Paul im Lavanttal: Selbstverlag des Stiftes.

König, D. 2015. Arabic-Islamic Views of the West: Tracing the Emergence of Medieval Europe . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Krusch, B. 1888. Fredegarii et aliorum chronica. Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Scriptores rerum Merowingicarum 2 . Hanover, Germany: Hahn.

Mango, C. 1985. Le développement urbain de Constantinople, IVe-VIIe siècles . Paris, France: Boccard.

Meneghini, R. and R. Santangeli Valenzani. 2004. Roma nell’altomedioevo: topografia e urbanistica della città dal V al X secolo. Rome, Italy: Volpe.

Michelet, J. 1833. Histoire de France 1. Paris, France: Hachette.

Monod, G. 1891. Histoire de l’Europe et en particulier de la France de 395 à 1270, with C. Bémont. Paris, France: Alcan.

Monod, G. 1923. La vie et la pensée de Jules Michelet (1798-1852). Paris, France: Champion.

Oman, C. 1905. The Dark Ages, 476–918. London: Rivingtons.

Palmer, J.T. 2015. The Otherness of Non-Christians in the Early Middle Ages. Studies in Church History 51: 33–52.

Pertz, G. 1911 Einhardi Vita Karoli Magni. Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Scriptores rerum Germanicarum in usum scholarum separatism editii 25 , ed. G. Waitz and O. Holder-Egger. Hanover, Germany: Hahn.

Pirenne, H. 1937. Mahomet et Charlemagne . Paris, France: Alcan.

Price, A.B. 2008. Pierre Puvis de Chavannes . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Richter, G. 1873. Annalen der deutschen Geschichte im Mittelalter 1 . Halle, Germany: Waisenhaus.

Rodriguez, J. 2015. Muslim and Christian Contact in the Middle Ages: A Reader . Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

Said, E. 1978. Orientalism . London: Routledge.

Teubner, M. 2008. Historismus und Kirchengeschichtsschreibung. Leben und Werk Albert Haucks (1845–1918) bis zu seinem Wechsel nach Leipzig 1889. Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht.

Tolan, J. 2002. Saracens. Islam in the Medieval European Imagination . New York: Columbia University Press.

White, H. 1973. Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe . Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Wood, I. 2013. The Modern Origins of the Early Middle Ages . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of History, University of St Andrews, Fife, UK

James T. Palmer

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to James T. Palmer .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Palmer, J.T. The making of a world historical moment: The Battle of Tours (732/3) in the nineteenth century. Postmedieval 10 , 206–218 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41280-019-00126-y

Download citation

Published : 17 July 2019

Issue Date : 01 June 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41280-019-00126-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

TheHistoryFiles.com

Weapons and Warfare throughout history and the analysis of doctrine, strategy and tactics.

TOURS (POITIERS)

October 732

Forces Engaged

Franks: Unknown. Commander: Charles Martel.

Moslems: Approximately 20,000-80,000. Commander: Abd er-Rahman.

Moslem defeat ended the Moslem’s threat to western Europe, and Frankish victory established the Franks as the dominant population in western Europe, establishing the dynasty that led to Charlemagne.

Historical Setting

During 717–718, Moslem forces tried and failed to capture Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine Empire. That was a major setback for the Moslems, whose forces (intent on spreading their faith) had been virtually unstoppable in conquests that spread Islam from India to Spain. Although that defeat kept the followers of Mohammed out of eastern Europe for another seven centuries, it must have motivated other Moslems to attempt to spread the faith into Europe via another route: North Africa into Spain into western Europe.

Moslem forces had spread across the southern Mediterranean coast through the later decades of the seventh century and in the process of converting their conquered enemies absorbed them into the armies of the faithful. In North Africa, some of the most ardent converts were Moors (called Numidians by the Carthaginians of Hannibal’s time), the Berbers of modern Morocco. In 710, Musa ibn Nusair, Moslem governor of the region, decided to attack across the Straits of Gibraltar and raid Spain. Without ships, however, he turned to Julian, a Byzantine official, who loaned him four ships. Julian did this because of a grudge he bore against Roderic, the Visigoth king that ruled in Spain. With four ships able to carry 400 men, Musa launched a raid that netted him sufficient plunder to whet his appetite for more.

In 711, he ferried 7,000 men across the straits under Tarik ibn Ziyad. Although this was originally intended to be simply a larger raid, Tarik’s victory over Roderic opened the Iberian peninsula to Moslem troops. Within a year, Musa was back in command and master of Spain. Recalled to the Middle East by the caliph, Musa’s successor, Hurr, pushed deeper into Spain and through the Pyrenees into the province of Acquitaine during 717–718. Over the next several years, Moslem power ebbed and flowed through southern, central, and even northern Gaul (France).

The arrival of the Moslems was fortuitously timed, as internal feuds divided the population of Gaul. The dominant population, the Franks, were in a slump. Upon the death of Pepin II in 714, the Frankish throne was disputed between Pepin’s legitimate grandson and illegitimate son. Eudo of Acquitaine saw an opportunity to escape Frankish domination, so he declared his independence and received in return the wrath of Charles Martel, Pepin’s illegitimate son who finally succeeded to the throne in 719. After defeating Eudo, Charles then turned toward the Rhine River to secure his northeastern flank. He made war against the Saxons, Germans, and Swabians until 725, when Moslem successes in southern Gaul diverted his attention.

While Charles was off fighting in Germany, Eudo feared for his future because he was located between aggressive Moslems to the south and a hostile Charles to the north and east. Eudo entered into an alliance with a renegade Moslem named Othman ben abi Neza, who controlled an area of the northern Pyrenees. That alliance provoked Abd er-Rahman, Moslem governor of Spain, who marched against Othman in 731. After defeating him, Abd er-Rahman decided to drive deeper into Gaul, spreading Moslem influence and, more importantly, looting the wealthy Gallic countryside. He defeated Eudo at Bordeaux and proceeded north toward Tours, whose abbey was reputed to hold immense wealth. To spread as much terror and accumulate as much loot as possible, Abd er-Rahman divided his army, probably some 80,000 strong, into several columns and sent them pillaging.

Eudo fled to Paris, where he met with Charles and begged his aid. Charles agreed on the condition that Eudo would swear loyalty and never again try to remove himself from Frankish dominion. With that promise, Charles gathered together as many men as he could and marched toward Tours.

The army that Charles amassed was probably some 30,000 men, a mixture of professional soldiers whom he had commanded in campaigns across Gaul and Germany and a mixed lot of militia with little weaponry or military skills. The Franks were hardy soldiers that armed themselves as heavy infantry, wearing some armor and fighting mainly with swords and axes. How much the Franks depended on cavalry has been disputed, for infantry had long dominated the European battlefield, and cavalry was only at this time becoming common. The strength of both infantry and cavalry was their determination in battle, but their weakness was their almost complete lack of discipline. Further, Charles lacked the wherewithal to maintain any sort of supply train, so his army lived off the land.

The army he marched to face was made up primarily of Moors who fought from horseback, depending on bravery and religious fervor to make up for their lack of armor or archery. Instead, the Moors fought with scimitars and lances. Their standard method of fighting was to engage in mass cavalry charges, depending on numbers and courage to overwhelm any enemy; it was a tactic that had carried them thousands of miles and defeated dozens of opponents. Their weakness was that all they could do was attack; they had no training or even concept of defense. They, like the Franks, lived off the land.

The two armies approached each other in the early autumn of 732. Abd er-Rahman’s army had succeeded in plundering many towns and churches, and they were overwhelmed with their loot. They met in an unknown location somewhere south of Tours, between that city and Poitiers. Abd er-Rahman was surprised by the arrival of the Franks. Exactly how large the opposing forces were is the point of much disagreement. The Moslem army is numbered by modern writers as anywhere from 20,000 to 80,000, whereas the Frankish army has been described as both larger and smaller than those numbers. Abd er-Rahman faced a dilemma: to fight, he would have to abandon his loot, and he knew that his men would balk at that order. Luckily for him, Charles did not attack, but merely kept his distance and observed the Moslems for about a week. Abd er-Rahman used that break to send men south with the loot, where they could recover it after they beat the Franks. In the meantime, Charles was awaiting the arrival of his militia, whom he used primarily as foragers for his fighting men and less as fighters themselves.

After 7 days of waiting, watching, and certainly a bit of probing by both sides, Abd er-Rahman felt his loot sufficiently safe to focus on the battle. The exact date of the battle is unknown, although some sources (Perrett, The Battle Book) name 10 October. Charles knew the nature of the Moslem fighting style, and he had just the troops to counter it. As the Moslems massed to launch their charge, Charles formed his men into a defensive square made up primarily of his Frankish followers, but supplemented with troops from a variety of tribes subject to the Franks. No detailed account of the battle exists, but later reports relate that the Moslem cavalry beat unsuccessfully against the Frankish square, and the javelins and throwing axes of the Franks inflicted severe damage on the men and horses as they closed. The Moslems, knowing no other tactic, continued to attack and continued to fail to break the defense. Isidorus Pacensis wrote staunch Frankish square: “The men of the North stood motionless as a wall; they were like a belt of ice frozen together, and not to be dissolved, as they slew the Arab with the sword. The Austrasians [Franks from the German frontier], vast of limb, and iron of hand, hewed on bravely in the thick of the fight.” It was this display of strength that earned for Charles his nickname Martel, or “the Hammer.” Eudo, fighting with Charles, led an attack that turned the Moslem flank; they either panicked or feared for their loot. Creasy (Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World, p. 166) quotes a Moslem source: “But many of the Moslems were fearful for the safety of the spoil which they had stored in their tents, and a false cry arose in their ranks that some of the enemy were plundering the camp; whereupon several squadrons of the Moslem horsemen rode off to protect their tents.” The departure of some of the cavalry apparently had a bad effect on the rest, and the Moslem effort collapsed.

At day’s end, the Moslems withdrew toward Poitiers. Charles kept his men together and did not pursue, thinking that the battle would resume the following day. In the night, however, the Moslems learned that Abd er-Rahman had been killed in the fighting, so they fled. When the Franks found the Moslem camp empty of men the next morning, they contented themselves with recovering the abandoned loot. No accurate casualty count for either side was recorded.

Survivors of Abd er-Rahman’s army retreated back toward Spain, but they were not the last Moslems that ventured across the Pyrenees in search of easy wealth. They were, however, the last major invasion. Pockets of Moslem power remained along the southern frontier and Mediterranean coast until 759, but, for the most part, Islam settled into Spain and went no farther. Although the effectiveness of Charles Martel’s tactics was certainly a factor, it was internal struggles within Islam that limited continued expansion. When factional fighting broke out in Arabia, the effects spread throughout the Moslem empire. This not only divided the fighting forces, it also isolated the Moslem occupants in Spain from any religious leadership from the Middle East. Thus, consolidation seemed preferable to expansion.

Had the Moslems been victorious in the battle near Tours, it is difficult to suppose what population in western Europe could have organized to resist them. On the other hand, Abd er-Rahman’s force was rather limited, and the religious schism that flared soon after the battle could well have stopped his campaigning as effectively as did the Franks. Thus, whether Charles Martel saved Europe for Christianity is a matter of some debate. What is sure, however, is that his victory ensured that the Franks would dominate Gaul for more than a century. For a couple of centuries, the ruling Merovingian dynasty had produced young, weak kings that ceded much of their ruling power to men who held the position of majordomo, or mayor of the palace. As the representative from the king to the aristocracy, the majordomos were able to coordinate public activity more than order it. By the time of Pepin II, however, the role of the majordomo was virtually indistinguishable from that of the king, and the monarch ruled in name only. Indeed, Charles was majordomo without a king, and upon his death in 741 his sons claimed kingship and divided the realm between them. During this same period, the aristocrats began exercising hereditary rights to their lands, rather than receiving their positions at the king’s pleasure. This was the start of the feudal era, which dominated European society for centuries. To exercise control over these aristocrats, Charles Martel also granted land in payment for military service rendered, but to acquire that land he had to take it from the greatest landowner, the Catholic Church. That earned him the displeasure of Rome, but similar actions on the part of Charles’s grandson actually brought the military power of the Franks and the religious authority of the church closer together. His grandson was also called Charles, later termed “the Great,” or Charlemagne. Under his rule, the Franks rose to their greatest power both politically and militarily.

The nature of the European military changed after this battle. The concept of heavy cavalry was forming in the eighth century. The introduction of the stirrup made stability on horseback possible, and stability was vital for both carrying an armored rider and using heavy lances. The age of the armored knight, a fighting machine that was both the result and the foundation of feudalism, was being born. Although infantry remained key to winning European battles, it was paired with or subordinated to cavalry from this point until the fifteenth century.

Thus, the establishment of Frankish power in western Europe shaped that continent’s society and destiny, and the battle of Tours confirmed that power.

References:

Creasy, Edward S. Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World. New York: Harper, 1851; Dupuy, R. Ernest, and Trevor Dupuy. Encyclopedia of Military History. New York: Harper & Row, 1970; Fuller, J. F. C. A Military History of the Western World, vol. 1. New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1954; Gregory of Tours. History of the Franks. Translated by Ernest Brehaut. New York: Columbia University Press, 1916; Oman, Charles. The Art of War in the Middle Ages. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1953 [1885].

You Might Also Like:

Varna 1444 part ii, leave a reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Members can access discounts and special features

Check availability

- About this activity

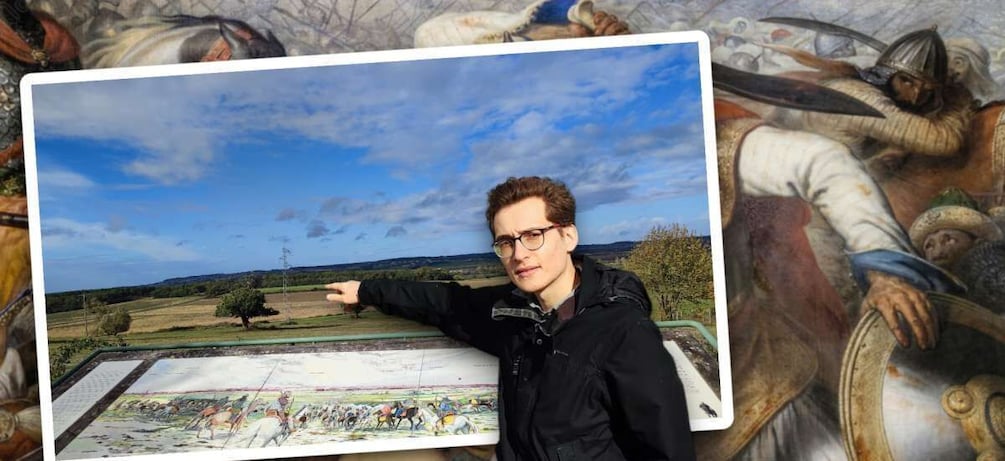

Guided tour of the Battlefield of 732 + Poitiers's center

- Free cancellation available

- Mobile voucher

- Instant confirmation

- Selective hotel pickup

- Multiple languages

- Discover the legendary battlefield of Poitiers 732

- Visit the historical center of Poitiers

- Discover local heritage and History

Activity location

- Poitiers, Nouvelle-Aquitaine, France

Meeting/Redemption Point

- Thu, Apr 25 -

- Fri, Apr 26 $412

- Sat, Apr 27 $412

- Sun, Apr 28 $412

- Mon, Apr 29 $412

- Tue, Apr 30 $412

- Wed, May 1 $412

- Thu, May 2 $412

- Fri, May 3 $412

- Sat, May 4 $412

- Sun, May 5 $412

- Mon, May 6 $412

- Tue, May 7 $412

- Wed, May 8 $412

- Thu, May 9 $412

- Activity duration is 2 hours 2h 2h

What's included, what's not

- What's included What's included Private guide

- What's included What's included Private transportation

- What's included What's included Entrance and fees

What you can expect

Did you know that the faith of Europe was decided in Poitiers, in 732 ? This tour is dedicated to the discovery of the History of the famous Battle of Poitiers (also called Battle of Tours). Your guide will pick you up in car, in front of your accomodation, and you will go to the incredible battlefield of 732. There, you will know more about this civilisational clash, where the muslims armies tried to conquer western Europe, but were stopped by the Kingdom of the Franks. After the tour of the battlefield, you will go to the center of Poitiers to discover more about the heritage of the city : this express tour will be focus hidden gems and artefacts of the middle age.

Flight search

- Adults Remove adult 1 Add adult

- Children Aged 2-11 Aged 2 to 11 Remove child 0 Add child

- Infants In seat Remove infant in seat 0 Add infant in seat

- Infants On lap Remove infant on lap 0 Add infant on lap

- Premium economy

Find cheap flights from France to anywhere Close dialog These suggestions are based on the cheapest fares to popular destinations in the next six months. Prices include required taxes + fees for 1 adult. Optional charges and bag fees may apply.

Useful tools to help you find the best deals, popular destinations from france, frequently asked questions.

A Decrease font size. A Reset font size. A Increase font size.

- france-ico COME TO IN POITIERS

from 01/04/2024 to 04/30/2024

Guided tours grand poitiers.

Home _ Events _ Guided tours Grand Poitiers

Prices from 4€ / Free under conditions

Appointment communicated at the time of reservation Limited group, registration required at the Palais : on site at Palace of the Dukes of Aquitaine, Place Alphonse-Lepetit, Poitiers or at the 06 75 32 16 64 every day from 11am to 1pm and from 2pm to 6pm

Wednesdays April 3, 10, 17, 24 at 3pm Sundays, April 7, 14, 21, 28 at 3 p.m.

1h / 1 monument : The Palace

Former residence of the Counts of Poitou - Dukes of Aquitaine, and then a courthouse, it is one of the most remarkable examples of medieval civil architecture in France. Its imposing tower and its great hall, at the same time place of life, festivals and justice, saw passing some of the illustrious characters of the History of France of which it still carries the print: William the Great, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Alphonse of Poitiers, Pope Clement V, King Philip IV the Fair, Jean de Berry.... Access to the Maubergeon Tower subject to availability // Includes presentation of the exhibition L'ours, le cygne et le crocodile, les animaux dans l'environnement du prince au Palais // Price: €4 - free under certain conditions // Duration: 1h

Saturday, April 6 at 3 p.m.

La Puye step by step

Take a step-by-step tour of La Puye to discover the town's rich history and heritage. Free visit // Duration: 01h30 // Meeting point: place de la Mairie, La Puye

Tuesday, April 9 at 12:30 p.m.

Sandwich visit: La Grand'Rue

Located between Notre-Dame-la-Grande church and the Sainte-Croix district, the Grand'Rue has been a lively shopping street since the Middle Ages. Discover the history of this street, lined with private mansions, craftsmen's stores and galleries. Free visit // Duration: 30mn

Saturday, April 13 at 3 p.m.

Poitiers, follow the guide !

Surprise visit during which the guide-lecturer makes you discover "his" Poitiers. Price: €5.5 - free under certain conditions // Duration: 1h30 to 2h

Tuesdays, April 16 and 23 at 2:30 p.m.

Croq'Palais: Budding architects

Fun heritage activities for children. Since the Middle Ages, and still today, the Palais has undergone many transformations, and its stones have been moved and "reused". Put yourself in the shoes of an architect, and discover the shapes that make up the architecture of the Palais, and recompose certain parts of the monument using recycled paper cut-outs. Children aged 5 to 7 accompanied by a parent // Price: €4/child - free for accompanying adults // Duration: 2h

Thursdays, April 18 and 25 at 2:30 p.m.

Croq'Patrimoine: Ulysses' Temporal Odyssey

Fun heritage discovery activities for children. Ulysse Texier de La Caillerie, an eccentric inventor, has created a time machine to explore different eras of Poitiers. But something has gone wrong: Ulysse is stuck in the Past! It's up to you to bring him back to the present. Children aged 8 to 12 accompanied by a parent // Price: €4/child - free for accompanying adults // Duration: 2h

Saturday, April 20 at 3 p.m.

Poitiers, 2000 years of history

Poitiers' historic center reveals over 2,000 years of history. Architectural gems from medieval times stand side by side with remarkable contemporary buildings. Ideal for getting to know the city! Price: €5.5 - free under certain conditions // Duration: 1h30 to 2h

Contact details

Social networks.

Tourism or press professionals, this space is designed for you to meet your specific needs.

Download here all our documentation (brochures, plans, outings,...)

Grand Poitiers Tourist Office

45, place Charles de Gaulle 86000 Poitiers

+33 (0)5 49 41 21 24

Opening Hours Monday to Saturday from 9:30am to 6pm

Tourist information offices

- Chasseneuil-du-Poitou

- Saint-Benoît

Practical information

- Coming to Poitiers

- Brochures/Maps

- Groups Area

- Visit Poitiers - Grand Poitiers Tourist Office

- Accommodation

- Deliberations

- Legal Notice

- Proxi'Loisirs 2024 competition

DISCOVER GRAND POITIERS

- GRAND POITIERS

- CHASSENEUIL-DU-POITOU

- SAINT-BENOÎT

TOPS & MUST-HAVES

- THE ESSENTIALS

- TALES & LEGENDS OF GRAND POITIERS

- BREATHTAKING TERRACES

- WHERE TO DINE LATE IN POITIERS

- RESTAURANTS: THE TOP OF THE KIDS

- Futuroscope

- Around the water

- Discotheques

- Heritage and historical centres

- Spirituality & churches

- Art Galleries

- Commercial streets

- The markets

Everclear announces 2024 tour with Marcy Playground. Get tickets

In 2000, Everclear got ambitious.

Following the success of their hit 1997 record “So Much For The Afterglow,” the band decided to release the sonically adventurous double album “Songs From An American Movie.”

Sales stalled because of how the record was rolled out — Vol. 1 hit shelves in July; Vol. 2 came out just four months later in November.

Now, a quarter century later, Art Alexakis and co. are dusting off “Songs From An American Movie” and taking the double album on the road along with fellow ’90s legends Marcy Playground and Jimmie’s Chicken Shack .

Along the way, they’ll visit Huntington, NY’s The Paramount on Oct. 6 and Asbury Park, NJ’s Asbury Lanes on Oct. 11.

“Join us as we celebrate 25 years of ‘Songs from an American Movie’, which we’ll be putting out on vinyl for the first time ever later this year,” Everclear shared on Instagram .

“A lot of these songs we haven’t played in a while or, in some cases, we’ve never played live before. We’ll of course be playing the hits and fan favorites too.”

Although inventory isn’t available on Ticketmaster until Friday, April 26, fans who want to ensure they have tickets ahead of time can purchase on sites like Vivid Seats before tickets are officially on sale.

Vivid Seats is a secondary market ticketing platform, and prices may be higher or lower than face value, depending on demand.

They have a 100% buyer guarantee that states your transaction will be safe and secure and will be delivered before the event.

A complete calendar including tour dates, venues and links to buy tickets can be found below.

*Shows from May through August are not officially part of the ‘Soundtrack From An American Movie Tour.’ All bolded September through November concerts are part of the newly announced tour.

As noted above, “Soundtrack From An American Movie” is a double album.

The first album, the 14-track “Learning How To Smile” features a handful of modest hits for the group including the bouncy “AM Radio” and the upbeat cover of Van Morrison’s “Brown Eyed Girl.”

Our hot take is the evocative title track “Learning How To Smile” is the real winner here; jaunty instrumentals and romantic lyrics about “leav(ing) this place and run(ning) away” are sure to melt even the most cynical hearts.

Hard rockin’ “Now That It’s Over” and “Unemployed Boyfriend” are bona fide headbangers, too.

Album number two — dubbed “Good Time For A Bad Attitude” and comprised of 12 songs — features crunchy, radio-friendly jams like “When It All Goes Wrong Again,” “Rock Star” and “Short Blonde Hair.”

Most of the record stays in that lane. Still, there’s one notable exception.

Folksy “The Good Witch Of The North” shows off Alexakis’ sensitive singer-songwriter side as the band wades into soft pop territory.

Want to do a deeper dive? You can find Everclear’s complete discography here .

At all shows, the “Santa Monica” quartet will be joined by Marcy Playground and Jimmie’s Chicken Shack.

As a quick refresher, here’s each act’s most-streamed song on Spotify:

Marcy Playground: “Sex & Candy”

Jimmie’s Chicken Shack: “High”

Quite a few acts that broke out when “Seinfeld” and “Friends” ruled the airwaves are hitting the road once again this year.

Here are just five of our favorites you won’t want to miss live these next few months.

• Gin Blossoms

• Third Eye Blind with Yellowcard

• Better Than Ezra

• Goo Goo Dolls

• The Wallflowers

Who else is on the road from the Clinton era? Take a look at our list of the 58 biggest ’90s stars on tour in 2024 to find out.

This article was written by Matt Levy , New York Post live events reporter. Levy stays up-to-date on all the latest tour announcements for your favorite musical artists and comedians, as well as Broadway openings, sporting events and more live shows – and finds great ticket prices online. Since he started his tenure at the Post in 2022, Levy has reviewed Bruce Springsteen and interviewed Melissa Villaseñor of SNL fame, to name a few. Please note that deals can expire, and all prices are subject to change.

Vivid Seats is the New York Post's official ticketing partner. We may receive revenue from this partnership for sharing this content and/or when you make a purchase.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

From June 1st to October26th, 2024 : On Tuesday and Saturday. Poitiers Biard airport is easily accessible by car thanks to our access map and our car park. Situated 2km from the city centre and 12km from Futuroscope you can also get around thanks to the shuttles (project), taxis or by renting a car. Découvrez les destinations en vol direct ...

The Battle of Tours-Poitiers Revisited. By William Watson. Providence: Studies in Western Civilization, Vol.2:1 (1993) The Battle of Tours-Poitiers has long occupied a prominent position in Western historiography. The eighth- or ninth-century Carolingian Continuator of Fredegar wrote that Charles Martel won his famous victory over the Muslim ...

Providence: Studies in Western Civilization Vol.2 No.1 (1993) Introduction: The Place of the Battle of Tours-Poitiers in Western Historiography. The Battle of Tours-Poitiers has long occupied a prominent position in Western historiography. The eighth- or ninth-century Carolingian Continuator of Fredegar wrote that Charles Martel won his famous ...

Si vous comparez le prix des transports par exemple, la course en taxi à Poitiers coûte en moyenne 2.40 EUR euros, ce qui est 4% moins cher que dans la ville de Tours, qui elle a des tarifs aux alentours de 2.50 EUR €, alors qu´un billet de train coûte 6% de moins à Poitiers: 1.50 EUR euros contre 1.60 EUR euros à Tours. Enfin, si vous comparez le repas du midi, les prix sont ...

Vols & Destinations Passagers. Suivez-nous. Contactez-nous. Heures d'ouverture Du lundi au dimanche et jours fériés : 8h00 à 19h00. Passagers ... Tours Val de Loire www.edeis.com +33(0)2 47 49 37 00 +33(0)2 47 49 37 00 40 rue de l'Aéroport 37100 TOURS France Mentions légales;

De Re Militari - The Battle of Tours-Poitiers Revisited (Apr. 05, 2024) Battle of Tours, (October 732), victory won by Charles Martel, the de facto ruler of the Frankish kingdoms, over Muslim invaders from Spain. The battlefield cannot be exactly located, but it was fought somewhere between Tours and Poitiers, in what is now west-central France.

The Battle of Tours (or Poitiers) in 732/3 is frequently cited as a turning point in world history, when the advance of Muslim Arabs was decisively halted by the Christian army of Frankish mayor Charles Martel. Yet the battle and its reputation seem relatively modest in the earliest sources, with little sense that conquest or religious tensions were key issues. This paper explores how the ...

Le moyen le plus rapide. Bus • 4 € • 1 h 20 min. Compagnie de voyage populaire. BlaBlaCar Bus. Voyager 92 kms en bus depuis Tours vers Poitiers. BlaBlaCar Bus est la meilleure compagnie pour cette itinéraire. Les voyageurs peuvent choisir un direct depuis Tours vers Poitiers.

This paper examines the Battle of Tours/Poitiers in 732 between the Merovingian Mayor of the Palace, Charles Martel, and the Umayyad governor-general of al-Andalus in modern-day Spain, Abdul Rahman Al-Ghafiqi. Since the pivotal works of Sir Edward Gibbons were published in 1776, the battle has been seen as keeping Europe from falling completely to Islam.

They met in an unknown location somewhere south of Tours, between that city and Poitiers. Abd er-Rahman was surprised by the arrival of the Franks. ... A Military History of the Western World, vol. 1. New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1954; Gregory of Tours. History of the Franks. Translated by Ernest Brehaut. New York: Columbia University Press, 1916 ...

The Battle of Tours, also called the Battle of Poitiers and the Battle of the Highway of the Martyrs (Arabic: معركة بلاط الشهداء, romanized: Maʿrakat Balāṭ ash-Shuhadā'), was fought on 10 October 732, and was an important battle during the Umayyad invasion of Gaul.It resulted in the victory for the Frankish and Aquitanian forces, led by Charles Martel, over the invading ...

This paper examines the Battle of Tours/Poitiers in 732 between the Merovingian Mayor of the Palace, Charles Martel, and the Umayyad governor-general of al-Andalus in modern-day Spain, Abdul Rahman Al-Ghafiqi. Since the pivotal works of Sir Edward Gibbons were published in 1776, the battle has been seen as keeping Europe from falling completely to

The defeat of the Saracen invaders of Frankish lands at Tours (more properly Poitiers) in 732 A.D. was a turning point in history. It is not likely the Muslims, if victorious, would have penetrated, at least at once, far into the north, but they would surely have seized South Gaul, and thence readily have crushed the weak Christian powers of Italy.

Website of the Tourist Office of Grand Poitiers, find out what to visit in Poitiers and the surrounding area, heritage, outings,... A Decrease font size. A Reset font size. A Increase font size. ... Guided tours Grand Poitiers. Discover Grand Poitiers through a variety of themes, accompanied by a certified guide! See the sheet. ALL NEWS ...

Did you know that the faith of Europe was decided in Poitiers, in 732 ? This tour is dedicated to the discovery of the History of the famous Battle of Poitiers. Vacation Packages. Stays. Cars. Flights. Support. All travel. Vacation Packages Stays Cars Flights Cruises Support Things to do.

TGV inOui operates a train from St Pierre Des Corps to Poitiers hourly. Tickets cost €24 - €55 and the journey takes 32 min. Two other operators also service this route. Alternatively, FlixBus operates a bus from Tours to Poitiers twice daily. Tickets cost €10 - €15 and the journey takes 2h 5m. BlaBlaCar Bus also services this route 3 ...

Use Google Flights to explore cheap flights to anywhere. Search destinations and track prices to find and book your next flight.

Poitiers, 2000 years of history. Poitiers' historic center reveals over 2,000 years of history. Architectural gems from medieval times stand side by side with remarkable contemporary buildings. Ideal for getting to know the city! Price: €5.5 - free under certain conditions // Duration: 1h30 to 2h. Sunday, April 21 at 3 p.m.

Find local businesses, view maps and get driving directions in Google Maps.

Moscow is home to some extravagant metro stations and this 1.5-hour private tour explores the best of them. Sometimes considered to be underground "palaces" these grandiose stations feature marble columns, beautiful designs, and fancy chandeliers. Visit a handful of stations including the UNESCO-listed Mayakovskaya designed in the Stalinist architecture. Learn about the history of the ...