- study guides

- lesson plans

- homework help

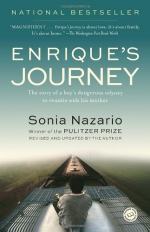

Enrique's Journey - Chapter 2 Summary & Analysis

Fast-forward a few years and find Enrique bleeding, beaten, in Oaxaca, Mexico. Sirenio Gomez Fuentes, a field hand, finds Enrique wearing only underpants, limping and swerving as he walks. Enrique asks Fuentes for a pair of pants, which Fuentes gives him before telling Enrique to seek out the Las Anonas mayor, Carlos Carrasco.

The mayor takes Enrique to his home, where the mayor and his mother treat Enrique's wounds the best they can. Enrique's teeth are broken. People come to see him, ask if he's going to be OK. Enrique tells them he is seeking his mother and people give him money. Carrasco knows Enrique will die if they can't find someone to drive him to get medical care. Carrasco convinces Adan Diaz Ruiz, mayor of San Pedro Tapanatepec, to drive Enrique. Ruiz thinks it's cheaper and easier to get Enrique to a doctor...

(read more from the Chapter 2 Summary)

FOLLOW BOOKRAGS:

Enrique’s Journey

Sonia nazario, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

At the age of five, Enrique watches his mother, Lourdes , leave their doorstep in Honduras. He does not know that she will not return. Lourdes is heading to the United States in search of work so that she can send money home to her two children, Enrique and Belky . Her experience in America is not easy; she becomes pregnant and works many different jobs. She wires money back home, but feels guilty and sad at the thought that her children are growing up without her. Meanwhile, Enrique struggles through his childhood and wishes for his mother's return. After many false promises, he begins to realize that she may never come home. He becomes lonely and angry, and turns to drugs when he becomes an adolescent. He moves from house to house under the care of different family members. When he is seventeen, he knows that he cannot continue his life in Honduras without the love of his mother. He sets out to find his mother in the United States, determined to make the difficult journey through Guatemala, up Mexico, and across the river. With hardly any money and few belongings, he leaves his hometown of Tegucigalpa and travels north.

Enrique must cross thirteen of Mexico's thirty-one states and traverse over 12,000 miles to reach his mother. He is one of many children who make a similar journey in search of a parent. The journey is extremely dangerous—he must face the depredations of bandits, gangsters, immigration officers, and corrupt police. Every region is different, and he must learn what to look out for and guard against through multiple trials. He attempts the journey from Honduras seven times. Much of the trip is made atop freight trains, where the chances of getting severely wounded and even dying are high. He survives the trip because of his perseverance, luck, drive, and above all, with the help of others. On his way, he meets fellow migrants with whom he shares stories and common experiences. In spite of the harsh circumstances and the ruthless people who target migrants, Enrique also encounters generous, kind, and compassionate people who offer their help at the risk of their own punishment. Although he makes much of the journey alone, crossing the river is too risky on his own. After getting in touch with his mother, he is able to secure a smuggler, his protector El Tiríndaro , to help him cross the border. Finally, on the eighth journey, after an arduous and long trip, he finds himself in the hands of his mother.

Their reunion, at first, is happy. Lourdes has established a good life in North Carolina with her boyfriend and daughter, Diana . Enrique is glad to be with his mother, but soon the complicated feelings of abandonment and anger come out. He and his mother begin to argue, and their relationship becomes tense. Back home in Honduras, Enrique's girlfriend, Maria Isabel , gives birth to their daughter, Jasmin . Enrique longs to bring his family to the United States, but continues to struggle with drug addiction and emotional problems. He sends money back to Maria Isabel as often as he can, but their relationship becomes strained. Maria Isabel receives criticism from Enrique's family members about how she is raising Jasmin and spending Enrique's money. Maria Isabel grows closer to Jasmin and has trouble deciding what will be best for her child. Finally, she decides to go to the United States to join Enrique. If she leaves now, the chances that her daughter will be able to come to America and grow up with both her parents will be higher. The book ends much in the same way that it begins: with a mother leaving behind her young child, unable to say goodbye.

Enrique’s Journey | Chapter Two: Badly Beaten, a Boy Seeks Mercy in a Rail-Side Town

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

The day’s work is done at Las Anonas, a rail-side hamlet of 36 families in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, when a field hand, Sirenio Gomez Fuentes, sees a startling sight: a battered and bleeding boy, naked except for his undershorts.

It is Enrique.

He limps forward on bare feet, stumbling one way, then another. His right shin is gashed. His upper lip is split. The left side of his face is swollen. He is crying.

Gomez hears him whisper, “Give me water, please.”

The knot of apprehension in Sirenio Gomez melts into pity. He runs into his thatched hut, fills a cup and gives it to Enrique.

“Do you have a pair of pants?” Enrique asks.

Gomez dashes back inside and fetches some. There are holes in the crotch and the knees, but they will do. Then, with kindness, Gomez directs Enrique to Carlos Carrasco, the mayor of Las Anonas. Whatever has happened, maybe he can help.

Enrique hobbles down a dirt road into the heart of the little town. He encounters a man on a horse. Could he help him find the mayor?

“That’s me,” the man says. He stops and stares. “Did you fall from the train?”

Again, Enrique begins to cry.

Mayor Carrasco dismounts. He takes Enrique’s arm and guides him to his home, next to the town church. “Mom!” he shouts. “There’s a poor kid out here! He’s all beaten up.” Carrasco drags a wooden pew out of the church, pulls it into the shade of a tamarind tree and helps Enrique onto it.

Lesbia Sibaja, the mayor’s mother, puts a pot of water on to boil and sprinkles in salt and herbs to clean his wounds. She brings Enrique a bowl of hot broth, filled with bits of meat and potatoes.

He spoons the brown liquid into his mouth, careful not to touch his broken teeth. He cannot chew.

Townspeople come to see. They stand in a circle. “Is he alive?” asks Gloria Luis, a stout woman with long black hair. “Why don’t you go home? Wouldn’t that be better?”

“I am going to find my mom,” Enrique says, quietly.

He is 17. It is March 24, 2000. Eleven years before, his mother had left home in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, to work in the United States. She did not come back, and now he is riding freight trains up through Mexico to find her.

Gloria Luis looks at Enrique and thinks about her own children. She earns little; most people in Las Anonas make 30 pesos a day, roughly $3, working the fields. She digs into a pocket and presses 10 pesos into Enrique’s hand.

Several other women open his hand, adding 5 or 10 pesos each.

Mayor Carrasco gives Enrique a shirt and shoes. He has cared for injured immigrants before. Some have died. Giving Enrique clothing will be futile, Carrasco thinks, if he can’t find someone with a car who can get the boy to medical help.

Adan Diaz Ruiz, mayor of San Pedro Tapanatepec, the county seat, happens by in his pickup.

Carrasco begs a favor: Take this kid to a doctor.

Diaz balks. He is miffed. “This is what they get for doing this journey,” he says. Enrique cannot pay for any treatment. Why, Diaz wonders, do these Central American governments send us all their problems?

Looking at the small, soft-spoken boy lying on the bench, he reminds himself that a live migrant is better than a dead one. In 18 months, Diaz has had to bury eight of them, nearly all mutilated by the trains. Already today, he has been told to expect the body of yet another, in his late 30s.

Sending this boy to a doctor would cost the county $60. Burying him in a common grave would cost three times as much. First, Diaz would have to pay someone to dig the grave, then someone to handle the paperwork, then someone to stand guard while Enrique’s unclaimed body is displayed on the steamy patio of the San Pedro Tapanatepec cemetery for 72 hours, as required by law.

All the while, people visiting the graves of their loved ones would complain about the smell of another rotting migrant.

“We will help you,” he tells Enrique finally.

He turns him over to his driver, Ricardo Diaz Aguilar. Inside the mayor’s pickup, Enrique sobs, but this time with relief. He says to the driver, “I thought I was going to die.”

An officer of the judicial police approaches in a white pickup. Enrique cranks down his window. Instantly, he recoils. He recognizes both the officer and the truck.

The officer, too, seems startled.

For a moment, the officer and the mayor’s driver discuss the new dead immigrant. Quickly, the policeman pulls away.

“That guy robbed me yesterday,” Enrique says. The policeman and a partner had taken 100 pesos from him and three other migrants at gunpoint in Chahuites, about five miles south.

The mayor’s driver is not surprised. The judicial police, he says, routinely stop trains to rob and beat immigrants.

The judiciales--the Agencia Federal de Investigacion--deny it.

In San Pedro Tapanatepec, the driver finds the last clinic still open that night.

Perseverance

When Enrique’s mother left, he was a child. Six months ago, the first time he set out to find her, he was still a callow kid. Now he is a veteran of what has become a perilous children’s pilgrimage to the north.

Every year, experts say, an estimated 48,000 youngsters like Enrique from Central America and Mexico enter the United States illegally and without either of their parents. Many come looking for their mothers. They travel any way they can, and thousands ride the tops and sides of freight trains.

They leap on and off rolling train cars. They forage for food and water. Bandits prey on them. So do street gangsters deported from Los Angeles, who have made the train tops their new turf. None of the youngsters have proper papers. Many are caught by the Mexican police or by la migra, the Mexican immigration authorities, who take them south to Guatemala.

Most try again.

Like many others, Enrique has made several attempts.

The first: He set out from Honduras with a friend, Jose del Carmen Bustamante. They remember traveling 31 days and about 1,000 miles through Guatemala into the state of Veracruz in central Mexico, where la migra captured them on top of a train and sent them back to Guatemala on what migrants call el bus de lagrimas, the bus of tears. These buses make as many as eight runs a day, deporting more than 100,000 unhappy passengers every year.

The second: Enrique journeyed by himself. Five days and 150 miles into Mexico, he committed the mistake of falling asleep on top of a train with his shoes off. Police stopped the train near the town of Tonala to hunt for migrants, and Enrique had to jump off. Barefoot, he could not run far. He hid overnight in some grass, then was captured and put on the bus back to Guatemala.

The third: After two days, police surprised him while he was asleep in an empty house near Chahuites, 190 miles into Mexico. They robbed him, he says, and then turned him over to la migra, who put him, once more, on the bus to Guatemala.

The fourth: After a day and 12 miles, police caught him sleeping on top of a mausoleum in a graveyard near the depot in Tapachula, Mexico, known as the place where an immigrant woman had been raped and, two years before that, another was raped and stoned to death. La migra took Enrique back to Guatemala.

The fifth: La migra captured him as he walked along the tracks in Queretaro, north of Mexico City. Enrique was 838 miles and almost a week into his journey. He had been stung in the face by a swarm of bees. For the fifth time, immigration agents shipped him back to Guatemala.

The sixth: He nearly succeeded. It took him more than five days. He crossed 1,564 miles. He reached the Rio Grande and actually saw the United States. He was eating alone near some railroad tracks when migra agents grabbed him. They sent him to a detention center, called El Corralon, or the corral, in Mexico City. The next day they bused him for 14 hours, all the way back to Guatemala.

It was as if he had never left.

This is his seventh try, and it is on this attempt that he suffers the injuries that leave him in the hands of the kind people of Las Anonas.

Here is what Enrique recalls:

It is night. He is riding on a freight train. A stranger climbs up the side of his tanker car and asks for a cigarette.

Trees hide the moon, and Enrique does not see two men who are behind the stranger, or three more creeping up the other side of the car. Scores of migrants cling to the train, but no one is within shouting distance.

One of the men reaches a grate where Enrique is sitting. He grabs Enrique with both hands.

Someone seizes him from behind. They slam him face down.

All six surround him.

Take off everything, one says.

Another swings a wooden club. It cracks into the back of Enrique’s head.

Hurry, somebody demands. The club smacks his face.

Enrique feels someone yank off his shoes. Hands paw through his pants pockets. One of the men pulls out a small scrap of paper. It has his mother’s telephone number. Without it, he has no way to locate her. The man tosses the paper into the air. Enrique sees it flutter away.

The men pull off his pants. His mother’s number is inked inside the waistband. But there is little money. Enrique has less than 50 pesos on him, only a few coins that he has gathered begging. The men curse and fling the pants overboard.

The blows land harder.

“Don’t kill me,” Enrique pleads.

His cap flies away. Someone rips off his shirt. Another blow finds the left side of his face. It shatters three teeth. They rattle like broken glass in his mouth.

One of the men stands over Enrique, straddling him. He wraps the sleeve of a jacket around Enrique’s neck and starts to twist.

Enrique wheezes, coughs and gasps for air. His hands move feverishly from his neck to his face as he tries to breathe and buffer the blows.

“Throw him off the train,” one man yells.

Enrique thinks of his mother. He will be buried in an unmarked grave, and she will never know what happened.

“Please,” he asks God, “don’t let me die without seeing her again.”

The man with the jacket slips. The noose loosens.

Enrique struggles to his knees. He has been stripped of everything but his underwear. He manages to stand, and he runs along the top of the fuel car, desperately trying to balance on the smooth, curved surface. Loose tracks flail the train from side to side. There are no lights. He can barely see his feet. He stumbles, then regains his footing.

In half a dozen strides, he reaches the rear of the car.

The train is rolling at nearly 40 mph. The next car is another fuel tanker. Leaping from one to the other at such speed would be suicidal. Enrique knows he could slip, fall between them and be sucked under.

He hears the men coming. Carefully, he jumps down onto the coupler that holds the cars together, just inches from the hot, churning wheels. He hears the muffled pop of gunshots and knows what he must do. He leaps from the train, flinging himself outward into the black void.

He hits dirt by the tracks and crumples to the ground. He crawls 30 feet. His knees throb.

Finally, he collapses under a small mango tree.

Enrique cannot see blood, but he senses it everywhere. It runs in a gooey dribble down his face and out of his ears and nose. It tastes bitter in his mouth. Still, he feels overwhelming relief: The blows have stopped.

He recalls sleeping, maybe 12 hours, then stirring and trying to sit. His mind wanders to his mother, then his family and his girlfriend, Maria Isabel, who might be pregnant. “How will they know where I have died?” He falls back to sleep, then wakes again. Slowly, barefoot and with swollen knees, he hobbles north along the rails. He grows dizzy and confused. After what seems to be several hours, he is back again where he began, at the mango tree.

Just beyond it, in the opposite direction, is a thatched hut surrounded by a white fence.

It belongs to field hand Sirenio Gomez Fuentes, who watches as the bloodied boy walks toward him.

At the clinic, Dr. Guillermo Toledo Montes leads Enrique to an examination table.

Enrique’s left eye socket has a severe concussion. The eyelid is injured and might droop forever. His back is covered with bruises. He has several lesions on his right leg and an open wound hidden under his hair. Two of his top teeth are broken. So is one on the bottom.

Dr. Toledo jabs a needle under the skin near Enrique’s eye, then on his forehead. He injects a local anesthetic. He scrubs dirt out of the wounds and thinks of the immigrants he has treated who have died. This one is lucky. “You should give thanks you are alive,” he says. “Why don’t you go home?”

“No.” Enrique shakes his head. “I don’t want to go back.” Politely he asks if there is a way that he can pay for his care, as well as the antibiotics and the anti-inflammatory drugs.

The doctor shakes his head. “What do you plan to do now?”

Catch another freight train, Enrique says. “I want to get to my family. I am alone in my country. I have to go north.”

The police in San Pedro Tapanatepec do not hand him over to la migra. Instead, he sleeps that night on the concrete floor of their one-room command post. At dawn, he leaves, hoping to catch a bus back to the railroad tracks. As he walks, people stare at his injured face. Without a word, one man hands him 50 pesos. Another gives him 20. He limps on, heading for the outskirts of town.

The pain is too great, so he flags down a car. “Will you give me a ride?”

“Get in,” the driver says.

Enrique does. It is a costly mistake.

The driver is an off-duty immigration officer. He pulls into a migra checkpoint and turns Enrique over.

You can’t keep going north, the agents say.

He is ushered onto a bus, with its smell of sweat and diesel fumes. He is relieved that there are no Central American gangsters on board. Sometimes they let themselves be caught by la migra so they can beat and rob the migrants on the buses. In spite of everything, Enrique has failed again -- he will not reach the United States this time, either.

He tells himself over and over that he’ll just have to try again.

Next: Chapter Three: Defeated Seven Times, a Boy Again Faces ‘the Beast’

More to Read

Mob in Mexico beats kidnapping suspect to death hours before Holy Week procession

March 29, 2024

L.A.’s Oaxacan community rallies after wildfire devastates a region of Mexico famed for its mezcal

March 15, 2024

How a Mennonite farmer became a drug suspect

Feb. 1, 2024

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

World & Nation

Egypt sends delegation to Israel, its latest effort to broker a cease-fire between Israel and Hamas

Betting on Trump to fail has made his stock shorters millions

U.S. found Israeli military unit committed human-rights abuses before Gaza war, Blinken says in letter

Biden says he’s ‘happy to debate’ Trump, during interview with Howard Stern

Enrique's Journey

39 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Prologue-Chapter 2

Chapters 3-5

Chapter 6-Epilogue

Key Figures

Index of Terms

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Immigration and Family Separation

Enrique’s Journey addresses the impact of immigration on families. Thus, it provides an alternative to common immigration narratives, which focus on ideological talking points designed to win political arguments. Studies show that an increasing number of unaccompanied minors are crossing the US-Mexico border. Like Enrique , many of these children undertake the trip north to find their mothers. Poverty and high divorce rates in Central America and Mexico leave many women unable to provide for their children. These women face hard choices: They can either remain in their home countries and watch their children suffer or immigrate to the US and send money home to support them.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Featured Collections

Books on U.S. History

View Collection

Contemporary Books on Social Justice

Immigrants & Refugees

Inspiring Biographies

Politics & Government

Required Reading Lists

Enrique's Journey

By sonia nazario, enrique's journey summary and analysis of on the border.

An American Border Patrol agent yells into his bullhorn, “You are in American territory. Turn back. Thank you for returning to your country” (137). Enrique is stymied. He has been in Nuevo Laredo, living in an encampment on the banks of the Rio Grande, for days. He has no idea if is mother is still in North Carolina. He does not have her phone number or enough money to call her. He knows his mother must have learned from relatives that he is gone. He decides to earn money to buy phone cards, so that he can call his former employer in Honduras (he remembers that number), to try and obtain his mother's number. Each card costs fifty pesos each; he decides to wash cars to earn it.

Enrique stays at an encampment for migrants, coyotes, drug addicts, and criminals. It is hidden from the U.S. immigration authorities by high reeds, thereby enabling the migrants to watch the agents and their sports utility vehicles. Enrique knows he will have to cross the river in order to get to the U.S., but so far has no idea how to achieve this. Some migrants swim over, while others use inner tubes.

Each evening, Enrique takes a bucket and two rags to a popular taco stand. There, he attracts potential costumers with a red rag. He earns very little money. Luckily, two local parish centers offer free meals to migrants. Though overcrowded, Enrique benefits from the charity, and meets other children who have similar stories to his own.

The encampment is run by a man called El Tiríndaro , a patero who smuggles people into the U.S. by pushing them across the river in an inner tube. He is a heroin addict who finances his drug use through tattooing people, petty theft, and smuggling. In Mexico, heroin is called la cura (the cure).

Enrique, known in the encampment as El Hongo (the mushroom) because of his shyness, continues to explore options as he lives under the protection of El Tiríndaro, who considers him a potential customer for smuggling. For $1,200, El Tiríndaro can not only get a migrant across the river, but also set him up with a smuggling operation that will get him further into the country. Luckily, many migrants in the camp look after him because of his age, which allows him to explore options. Each night, when he leaves to wash cars, he is scared to be outside of their protection.

Unfortunately, Enrique is not making enough money for phone cards, and feels guilty when he uses his meager savings on food. El Tiríndaro helps Enrique by taking him to sell the clothing left behind on the riverbank by migrants. Finally, Enrique saves enough to buy two phone cards. To celebrate, he gets a tattoo which reads “EnriqueLourdes” across his chest. He knows his mother will not be pleased. The next day, hungry, he trades one of his phone cards for money to buy food. He begins to sniff glue again, to battle his hunger, fear, and loneliness. Then, someone steals his washing bucket, and he must beg to make money for another phone card.

Enrique considers crossing the river by himself, but he cannot swim and if he were caught, he would be deported. Trains going from Mexico into Texas are out of the question, as they are searched several times and scanned with infrared telescopes to sense body heat. He also cannot walk through Texas, as he is unfamiliar with the terrain. Migrants have been known to die of dehydration in 120 degree weather, or to end up shot by Texan ranchers.

Nazario discusses the extent of security at the border. The INS has hired 5,600 additional agents since 1993 to staff the border. Some agents can track the footprints of migrants as they walk through the Texas desert. Others can tell how old the footprints are and in which directions the migrants are headed. Agents are paid to bring migrants in, and are given a bonus for catching them. They also insist that they actually work in the best interest of migrants, since migrants are too often wounded or killed by rattlesnake bites, train injuries, dehydration, or animals like coyotes and bobcats. In the depressing, difficult terrain, many migrants are thankful when apprehended.

Enrique decides to hire a smuggler, and chooses El Tiríndaro because of his high success rate. Before he can call his family in Honduras, someone steals his right shoe in the middle of the night. Enrique is furious; shoes are almost as important as food in the encampment. He has gone through seven pairs during his journey north. Desperately, he searches for a shoe and finds one on the riverbank - unfortunately, it is a left show, and so now he has wears two left shoes.

On May 19th, Enrique visits Padre Leo , a local priest and advocate for migrant care. Padre Leo is a disheveled but lovable man who rides a blue bicycle. Migrants call him their "champion" because he literally gives them the shirt off his back and the shoes from his feet (175). He also allows the migrants to use the church phone, which Enrique does to call his old boss, who eventually connects him with his relatives, who in turn give him Lourdes 's phone number. He next calls Lourdes collect, and they begin preparations to hire a coyote for $1,200.

From the banks of the Rio Grande, the overwhelming sight of the United States represents not only the illusive imagery of the American dream, but also the culmination of Enrique’s journey. His mother feels nearby, although he has no idea whether she is still in North Carolina and has no way to reach her. The promise of the U.S. stands in stark contrast to to the harsh poverty of Nuevo Laredo, where Enrique thanklessly washes cars but can barely save anything.

One of the photographs by Don Bartletti, included in Enrique’s Journey , shows Enrique washing cars at night. Nazario first met Enrique in Nuevo Lardeo during this time period. Her personal insight into the encampment, the stories of other child migrants, and the information she relates about the U.S. Border Patrol all work together to provide a well rounded and insightful image of what life is like for Enrique without compromising the narrative. Bartletti’s photographs further enhance the overall story, giving faces to the names, which naturally underscores the reality of Enrique’s situation.

Nazario's authorial interjections do not detract from Enrique's position as a protagonist. It is an exciting development from a narrative standpoint - our hero has almost reached his goal, but suddenly finds himself facing a new set of overwhelming odds. We continue to root for him, even as setbacks like losing a shoe make his success seem impossible. The chapter ends with something of a cliffhanger - he will get the money! - but clearly, there are more challenges to face.

The phone cards serve as physical representations of Enrique's hope. When he trades one of them for food, it is a visceral reminder of the poverty that grounds him even at his strongest. Were he to fail now, he would have to start over for a ninth time. Two symbols are juxtaposed in this section to exhibit his conflict - his tattoo expresses his unshakeable hope, while the phone card, which he sells the next day, represents the inescapable demands of money and food. These are the forces that compete throughout the story, and no matter how close he gets, the conflict continue to resonate.

Other mothers in the encampment are less enthusiastic or hopeful. As Mother’s Day passes, the young women Nazario speaks to relate how worried they are for the children they have left behind. Mother’s Day is a harsh reminder of the distance between themselves and their children. These mothers pray for their children’s safety, too. One mother says she fears she will lose the love of her children if she stays too long in the United States. On the other side of the Rio Grande, Lourdes worries for her son and prays to St. Judas, patron saint of those in need as well as those who are lost.

Drug use, a distressing but dominant motif within the text, reappears at the end of “On the Border” when Enrique begins to sniff glue again. What is heartbreaking is that we understand the forces that lead him in that direction - his fear, his hunger, his loneliness - but also know that such activity could compromise his mission. His love for her has not faltered, but it now competes with his more physical pain. Narratively, the book stays intriguing as we wonder not only whether Enrique will make it to the U.S., but also whether he will be able to find personal happiness there.

Enrique’s Journey Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for Enrique’s Journey is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

WHAT IS ENRIQUE FORCCED TO DO UPON RINALY REACHING THE AMERICAN SIDE OF THE RIO GRANDE

In order to remain undetected, Enrique and the others must wait for an hour in a half in a freezing creek into which a sewage treatment plant dumps refuse.

Why is crossing the river so difficult?

For Enrique, crossing the river by himself is dangerous. He cannot swim and if he's caught, he will be deported.

They are put in detention centers and sent back. The detention centers ar cramped full of crooks and people that exploit them.

Study Guide for Enrique’s Journey

Enrique's Journey study guide contains a biography of Sonia Nazario, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About Enrique's Journey

- Enrique's Journey Summary

- Character List

Essays for Enrique’s Journey

Enrique's Journey essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of Enrique's Journey by Sonia Nazario.

- Criticism, Sympathy, and Encouragement: Depicting the American Dream in 'The Great Gatsby' and 'Enrique's Journey'

Lesson Plan for Enrique’s Journey

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Common Core Standards

- Introduction to Enrique's Journey

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- Enrique's Journey Bibliography

Wikipedia Entries for Enrique’s Journey

- Introduction

- Don Francisco Presenta Reunion

- Recognition

- Sonia Nazario

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Analysis. In a small town in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, Enrique, severely battered and wearing only his underwear, limps towards a field hand. The man provides Enrique with a pair of pants and directs him to the mayor, who brings him to his home and takes care of him. A mayor from a neighboring town arrives in a truck and takes Enrique to the ...

Chapter 2 displays the life-and-death nature of Enrique 's attempt to reach the United States. At the beginning of the chapter, the reader sees Enrique bloody and beaten, with Nazario pointing out that this is his seventh attempt to cross the U.S. border. His determination to reunite with Lourdes is so strong that it will take his own death to ...

Chapter Summary; Prologue: The prologue of Enrique's Journey begins with an anecdote from 1997 in which Sonia Nazario chats with her Guatemalan hou... Read More: Chapter 1: It is January 29, 1989. Enrique is five years old. He lives with his mother, Lourdes, and seven-year-old sister, Belky, ... Read More: Chapter 2

Summary. Fast-forward a few years and find Enrique bleeding, beaten, in Oaxaca, Mexico. Sirenio Gomez Fuentes, a field hand, finds Enrique wearing only underpants, limping and swerving as he walks. Enrique asks Fuentes for a pair of pants, which Fuentes gives him before telling Enrique to seek out the Las Anonas mayor, Carlos Carrasco.

Chapter 2 describes Enrique's seven failed attempts to migrate to the United States, stressing the dangers he encounters along the way. The journey is long and treacherous. To reach the US, Enrique must travel through many regions of Mexico controlled by gangs, where he faces risk of arrest by immigration officers.

Enrique must cross thirteen of Mexico's thirty-one states and traverse over 12,000 miles to reach his mother. He is one of many children who make a similar journey in search of a parent. The journey is extremely dangerous—he must face the depredations of bandits, gangsters, immigration officers, and corrupt police.

Summary. Near a small rail side town in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, Enrique hobbles up towards a field hand. He is severely beaten, and dressed only in his underwear. The field hand gives him clothes and water, while women from the town give him money. A mayor from a neighboring town arrives in a pickup truck, and takes Enrique to a local ...

This study guide for Sonia Nazario's Enrique's Journey offers summary and analysis on themes, symbols, and other literary devices found in the text. Explore Course Hero's library of literature materials, including documents and Q&A pairs. ... Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 ...

Prologue Summary. The Prologue explains why Nazario wrote the articles that served as the basis for Enrique's Journey. In 1997, she learned that her housekeeper, Carmen, had four children in Guatemala whom she had not seen in 12 years. Carmen immigrated to the US to find work, leaving her children behind and placing an emotional strain on her ...

Enrique's Journey Summary. Enrique 's Journey chronicles the life of a young Central American boy, and his quest to reunite with a mother who left him at the age of five to find work in the United States. Enrique's mother, Lourdes, struggles in Honduras to support her young children, Belky and Enrique. She knows she will not be able to send ...

Complete summary of Sonia Nazario's Enrique's Journey. eNotes plot summaries cover all the significant action of Enrique's Journey. ... 1984 Part 1 Chapter 6 and 7 Quiz ©2024 eNotes.com, Inc. All ...

The day's work is done at Las Anonas, a rail-side hamlet of 36 families in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, when a field hand, Sirenio Gomez Fuentes, sees a startling sight: a battered and bleeding ...

Analysis. Enrique's Journey opens with a photo of a young Enrique looking sadly into the camera while wearing his kindergarten graduation gown and hat. His expression is somber, which sets the tone for the first few sections of the book, in which a young Enrique adjusts to life without his mother.

Get unlimited access to SuperSummaryfor only $0.70/week. Thanks for exploring this SuperSummary Study Guide of "Enrique's Journey" by Sonia Nazario. A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Enrique's Journey Plot Diagram. 1 Lourdes raises two kids in poverty-stricken Honduras. 2 She moves to the United States to make money to send home. 3 Her son, Enrique, has a troubled, drug-plagued childhood. 4 At age 17, Enrique treks through Mexico to join Lourdes. 5 They reunite at Lourdes's mobile home in North Carolina.

Summary. An American Border Patrol agent yells into his bullhorn, "You are in American territory. Turn back. Thank you for returning to your country" (137). Enrique is stymied. He has been in Nuevo Laredo, living in an encampment on the banks of the Rio Grande, for days. He has no idea if is mother is still in North Carolina.

What two things did carmen want to make known by writing this book. 1- mothers should think more before abandoning their kids. 2- highlight the immigration journey. How old is Enrique and his siblings when his mom leaves. 5 and belkey is 7. Why is lourdes embarrassed.

A Fateful Robbery. One afternoon when Jasmín is age nine, she is hanging out with Diana at the phone store where Diana works. Business is slow, and the two are watching a movie. A man with a gun enters and demands the money in the cash register. When he runs out the door, Jasmín follows and gets a description of his car.