- Help Center

- Plan Your Visit

- Places to Stay

- Youth Programs

- Student & Youth Groups

- Dining Programs

- Events & Catering

- Live Cameras

- Our Mission

- Conservation Status: Threatened

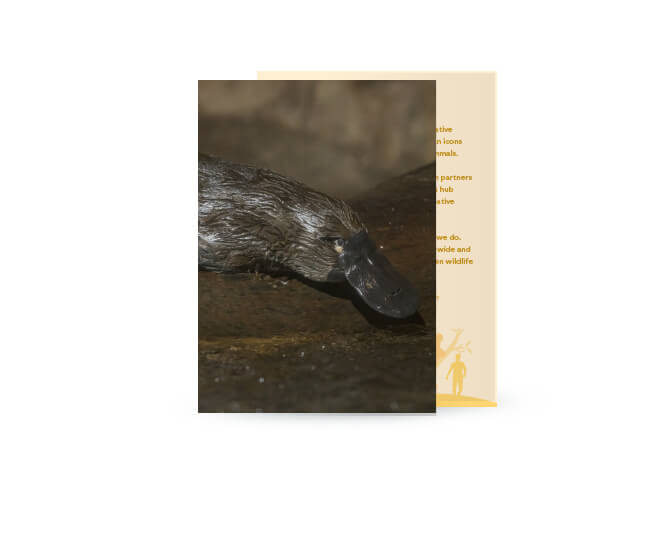

With a duck-like bill, a fur coat, big webbed feet, and a paddle-shaped tail, the platypus looks like no other mammal. And even more unusual: this mammal lays eggs. The platypus is a monotreme (like the echidna), which lays eggs, incubates them, and nurses its young when they hatch. Found only in Australia (in Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, and Tasmania), the platypus lives in freshwater habitats, including streams and ponds. It forages about 12 hours a day, eating shellfish, worms, and insect larvae—and it must consume the equivalent of about 20 percent of its body weight each day. The platypus locates food by using electroreceptors in its soft bill, which detect their prey's movements.

Save the Chubby Unicorns

Gorilla Shadow

PREFERRED HOTELS

Come Travel with Us!

Travel with us to see Monarchs

Picture Your Special Day at the Park!

Search form

- Class: Mammalia

- Order: Monotremata

- Family: Ornithorhynchidae

- Genus: Ornithorhynchus

- Species: anatinus

The platypus is as fascinating on the inside as it is on the outside! Among Australia’s most iconic wildlife, this semi-aquatic, egg-laying species is also one of the few venomous mammals. At a glance, it looks like a hodgepodge of animal pieces stitched together: a paddle-shaped tail from an otter, a sleek body covered in dense, chestnut-colored fur like a mole, a wide, flat duck-like bill attached in front of its little round eyes, and big webbed feet like a pelican.

All these characteristics come in handy for its freshwater lifestyle—that bizarre looking bill is laden with thousands of receptors that help a platypusl navigate the murky depths and detect tiny movements of potential food like shellfish or insects.

Just “fur” fun. While their range is just one small area of the world, they weather many climate extremes (and fresh water sources) from toasty plateaus and rainforests, to the chilly mountainous regions of Tasmania and the Australian Alps. Their dense fur makes fine insulation, both in the water and out.

Platypus fur is waterproof and traps an insulating layer of air to keep its body temperature stable, even in cold water. Long guard hairs protect the dense fur underneath, which stays dry even after a platypus has been in the water for hours. Mostly brown on its body, there’s a flash of white fur beneath its eyes, and its belly is lighter in color, too.

Those big webbed feet help propel them through the water, and the claws make digging burrows a breeze. While lumbering somewhat awkwardly on land to protect the webbing on its feet, they are sleek missiles in the water. Its plump tail serves as a stabilizer during swimming and stores extra fat for energy. Its rear feet serve as rudders and brakes.

Ready for the bill. Its signature “duck bill” is actually soft and pliable, not hard like a duck’s bill at all. It is dark colored, nearly black in contrast to its chocolate-colored coat. This strange-looking snout is laden with “pushrods” that respond to stimuli like touch, pressure, sound waves, and motion. Additionally, about 40,000 electroreceptors help them find the direction and distance of prey (its eyes and ears are closed while it’s underwater) by detecting electrical impulses generated by living creatures. Moving its head back and forth, it can find prey nearby and swiftly move in for the kill.

Platypuses stow their prey in cheek pouches, and swim to the surface to eat. They (and their relatives the echidnas) don’t have teeth, but instead grind their food between mouth pads made of keratin. These pads are replaced continuously throughout its lifetime. Interestingly, freshly hatched platypuses have molar-like “milk teeth," but these are shed around the time they leave the nesting burrow.

More wow. Of course, its major claim to fame is being an egg-laying mammal, or monotreme. While most other mammals have so-called live young, platypuses (along with echidnas) lay eggs, incubate them, and nurse their young. Wow!

Other interesting characteristics include extra bones in the shoulder girdle, which is absent in other mammals. On land, the platypus has a reptilian gait because its legs are on the sides of the body, rather than underneath. The white spots on the fur under its eyes make it look like its eyes are open underwater, but they’re not.

There is considerable variation in size among platypus populations. Generally, body size increases with latitude. So “Down Under” platypuses are smaller in northern regions, and larger in southern regions. For instance, a large male platypus in Tasmania can weigh three times as much as an average male in a northern population. Overall, males are larger than females and can measure 16 percent longer and 40 percent heavier than them.

HABITAT AND DIET

Wet and wonderful. According to the platypusspot.org website, ideal habitat for these monotremes “includes permanent water, stable earthen banks consolidated by the roots of native riparian vegetation that is also overhanging the water, and an abundant supply of macroinvertebrates.” Needless to say, natural changes like prolonged drought or human-made alterations like dams, tree clearing, and development, all impact the platypuses’ necessary habitat. Humans competing for fresh water poses even more threats to the platypus.

Platypuses may also be found in shallow lakes, artificial water sources like water storage lakes, weir pools, ponds, and farm dams. They occasionally dip into brackish areas of estuaries, but mostly stick with freshwater areas.

Adult male platypuses have larger home ranges than females—as long as 9.3 miles (15 kilometers)! A male may travel over 6 miles (10 kilometers) in a single night’s jaunt. Females tend to hunt closer to home, and her turf is usually less than 2.8 miles (4.5 kilometers) long.

Detecting dinner. While they may make repeated short dives of 30 to 60 seconds or so, they can stay underwater for up to 2 minutes. Dive time and depth is reliant on air in its lungs—they usually dive less than 16 feet (5 meters), though they occasionally take deeper dives to about 26 feet (8 meters). They come to the surface to recover for 10 to 20 seconds between dives.

These underwater forays enable it to feed on insect larvae, freshwater shrimp, freshwater crayfish called "yabbies" (which it nuzzles out of the riverbed with its snout or catches while swimming), and worms. It uses cheek pouches to stow its bounty until it reaches the surface, where it can eat. Each day, a platypus needs to eat about 20 percent of its body weight, which requires about 12 hours of looking for food.

Lacking teeth, the platypus must scoop up bits of gravel with its food to help “chew” its meal. They swallow soft parts of their prey and spit out the chitinous exoskeletons (like the shells of crayfish and insects).

Due to its somewhat limited ability to hold its breath, the platypus forages in more shallow lakes and bodies of water, between 3 and 16 feet (1 and 5 meters) deep.

Nice digs. Male and female platypuses dig simple burrows along rivers and streams outside the breeding season. They can also make their home under rock ledges, roots, and debris, where they rest throughout the day. However, pregnant females dig a deeper, more elaborate nesting burrow, with multiple chambers and entrances, called a nursery burrow. When the female leaves her young behind to forage, she makes a soft covering of soil and debris to plug the opening. Resting burrows are used by males and nonbreeding females.

Runs cool. The average body temperature of a platypus is about 90 degrees Fahrenheit (32 degrees Celsius), while most placental mammals run about 99 degrees Fahrenheit (37 degrees Celsius). It is able to maintain this temperature even when foraging for hours in water below 39 degrees Fahrenheit (4 degrees Celsius). Brrrr!

FAMILY LIFE

Nocturnal journal. The platypus is generally active at night and dusk, and occasionally active by day. It emerges from its burrow in late afternoon to forage for food. By early morning, it is ready to re-enter the burrow. One scientist found that platypuses in the southeastern Australian state of Victoria spent 11 to 17 hours holed up in the burrow. Others have found that platypuses can hunt for 10 to 12 hours at a time. Its high-calorie diet of crustaceans enables the platypus to sleep soundly for up to 14 hours a day! Interesting side note: the platypus spends nearly 60 percent of its daily sleep in deep, brain-active REM sleep (in contrast, humans spend about 25 percent of their slumber in that rich, REM state).

Pregnant females spend time building a cozy nest, nursing and nurturing their young, and foraging for food. While platypuses are not considered hibernators, they may be inactive for extended periods of time.

Watch out! For the platypus, leaving its burrow is a high-risk proposition, even at night. When drought or altering of waterways occurs, platypuses are forced to travel on land, making them more vulnerable to predation. Aerial predators like owls, eagles, and hawks may prey upon them. Native threats like dingoes, Tasmanian devils, monitor lizards, snakes, and water rats also await. Invasive feral and unleashed dogs, cats, and foxes also take them. Low platypus numbers in northern Australia may be due to heavy predation by crocodiles.

Male platypuses have spurs on the rear ankles, connected to a venom gland located over its thighs. If the spur pierces the skin, it can release enough venom to kill a medium-sized dog. (It is not fatal to humans, but is excruciating, and causes swelling.) The venom is more plentiful during breeding season, leading scientists to believe that it is used to defend mates and resources from rival males.

As air-breathing, aquatic mammals, platypuses can quickly drown after getting entangled in discarded litter, fishing line, and mesh netting. “Opera house” nets that people set to catch crayfish and yabbies can be death traps for platypuses, turtles, and water rats, as wildlife cannot escape. These underwater traps (roughly shaped like the Sydney Opera House, hence the name) are often set during summer months, when female platypuses may be pregnant, which exacerbates the impact on fragmented populations.

Even common items like rubber bands, plastic rings, or hair ties can be lethal when caught on the legs or neck of a swimming platypus.

Say what? The platypus is largely solitary, so a vast vocal repertoire is not necessary. It emits a growl when disturbed, and a range of other vocalizations have been noted.

Scent glands on both sides of the neck produce a musky scent during the breeding season. They rub against logs and rocks near the water to mark objects. When swimming, the platypus will make a big splash when alarmed as it slips beneath the surface, likely to give other platypuses a heads up. Usually, they are nearly silent when diving.

You’re a good egg. Males compete for breeding opportunities (hence the venomous spur), while females typically mate with a single male. Once she has settled on a male, aquatic courtship ensues, with the pair diving and swimming past each other, then grasping and rolling together.

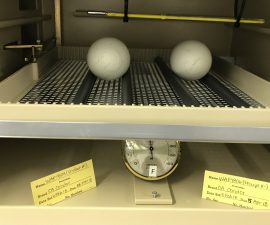

Pregnant platypuses seek shelter in a burrow chamber dug into a riverbank to lay 1 to 3 eggs. (The four echidna species are the only other living egg-laying mammals, which are called monotremes.) This elaborate burrow is much deeper and blocked at intervals with plugs, which may protect her eggs from predators or rising waters, or regulate humidity and temperature in the burrow. She lines this nesting chamber with wet leaves, twigs, and vegetation, which she carries into her burrow between her hind feet and her tail.

Safely sealed inside, she keeps her eggs between her rump and her tail to keep them warm, only leaving the burrow to defecate and wet her fur. Typically, her eggs are about 0.7 inches (1.7 centimeters) in a diameter and rounder than bird eggs. The shell is soft and pliant.

After about 10 days, the hairless, bean-sized babies hatch and begin to suckle for the next 3 or 4 months. The mother does not have nipples, but rather special patches of skin on the abdomen that exude milk for her babies to slurp up. By the time they are weaned and leave the nest, the baby platypuses have fur and can swim on their own.

The San Diego Zoo Safari Park is currently the only zoo outside Australia to house platypuses. When two platypuses—a male named Birrarung and a female named Eve—arrived in San Diego in October 2019, it was the first time in more than 50 years that platypuses were cared for outside of Australia. San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance recognizes that we are only the most recent stewards of wildlife that means a great deal to Australians, and holds cultural significance for the Aboriginal Nations of Australia.

The two platypuses were flown to San Diego from their home at Australia's Taronga Zoo Sydney to serve as ambassadors outside their native Australia, to help communicate the importance of fresh water for both humans and wildlife. Freshwater resources and habitats are being affected by pollution and climate change. People are encouraged to be part of the solution and protect wildlife through water conservation measures and practices that help slow climate change.

Guests can now see the platypus pair in Walkabout Australia's new Nelson A. Millsberg Platypus Habitat, which includes three pools, naturalistic river banks, extensive tunnels, and nesting areas. The platypuses quickly acclimated to their new home, exploring every inch of their surroundings, playing in the waterfalls and hunting for crayfish. Because platypuses are most active during dusk and nighttime hours, the lighting cycle in their habitat has been reversed to mimic evening light during the day and daylight at night.

CONSERVATION

Fresh water is a precious resource. As development and growing human populations disrupt these aquatic ecosystems, it can impact platypus populations. San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance is proud to support a cutting-edge conservation effort in southeastern Australia that benefits endemic wildlife, including the platypus. A collaborative team is using a new technology called environmental DNA (eDNA) to map the distribution of and threats to five kinds of fish and the platypus. The goal is to secure populations in at least three natural catchment areas.

As living things shed their DNA through skin, hair, scales, feces, and eggs, water samples collected and filtered through a special unit that strains out cells and analyzes them will reveal the wildlife that are present. San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance is pleased to be supporting the “boots on the ground” efforts to preserve endemic wildlife, including the platypus.

By supporting San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, you are our ally in saving and protecting wildlife around the globe.

Length from tip of bill to tip of tail: males 16 to 25 inches (40 to 63 centimeters); females 15 to 22 inches (37 to 55 centimeters)

Weight: males: 1.8 to 6.6 pounds (0.8 to 3 kilograms); females: 1.3 to 3.7 pounds (0.6 to 1.7 kilograms)

Length at hatch: about 1 inch (2.5 centimeters)

Life span: 7 to 14 years; or up to 21 years in zoos

Gestation: approximately 21 days

Incubation: approximately 10 days Number of young at hatch: 1 to 3 eggs per breeding season; usually 2 eggs

Age of weaning: 3 to 4 months old

The word “platypus” is derived from a Greek word meaning “flat foot.” The correct plural ending is “es”—making “platypuses” preferred over “platypi.”

The platypus and the echidna are the only living mammals that lay eggs. They are called monotremes.

Females don’t nurse their young with nipples, rather they exude milk through skin patches.

Adult male platypuses have venomous spurs, an unusual characteristic among mammals, used to defend mates and territory from rival males.

Females have two ovaries, but only the left one is functional, similar to many birds and some reptiles.

DISCOVER WILDLIFE

More animals & plants from san diego zoo and san diego zoo safari park.

San Diego Zoo Safari Park Launches New Platypus Cam Presented by Animal Crossing™: New Horizons

We’re Here Together Campaign Brings Platypuses to Your Home—Virtually

While the San Diego Zoo Safari Park is temporarily closed to on-grounds visitors due to COVID-19 restrictions, online guests can now visit the platypuses at the Safari Park’s Walkabout Australia on their smartphone or computer. The all-new Platypus Cam presented by the Animal Crossing™: New Horizons game provides livestreaming video of the Safari Park’s platypus pair as they swim and frolic in their world-class habitat—including three pools, naturalistic river banks, extensive tunnels and nesting areas. The Animal Crossing: New Horizons game is available on the Nintendo Switch system and invites players of all ages to create their own island paradise while making friends with charming animal residents in the process.

“San Diego Zoo Global is grateful for Nintendo’s support of Platypus Cam, adding to the many ways our guests engage with wildlife during these trying times,” said Ted Molter, chief marketing officer of San Diego Zoo Global. “Platypus Cam is the newest addition to San Diego Zoo Global’s We’re Here Together Campaign, which invites guests from around the world to stay connected to their favorite animals and species through a wealth of free online content, entertainment and educational tools.”

Guests at home can view livestreaming video from the platypus habitat at sdzsafaripark.org/platypus-cam .

The two platypuses featured on the cam—an 8-year-old male named Birrarung and a 15-year-old female named Eve—serve as ambassadors for the species outside of their native Australia. The San Diego Zoo Safari Park is currently the only zoo outside of Australia to house platypuses.

Platypuses can be difficult to see, both in the wild and in a zoological setting, so being able to get a glimpse of these elusive, busy animals is a rare and special experience.

The platypus is a semiaquatic, egg-laying mammal found along the eastern coast of Australia, within the states of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania. They live in freshwater streams, creeks and rivers. The two platypuses at the Safari Park communicate the importance of fresh water for both humans and wildlife. Freshwater resources and habitats are being affected by pollution and climate change. People are encouraged to be part of the solution and protect wildlife through water conservation measures and practices that help slow climate change.

To understand what is occurring with platypuses in Australia—and to better understand the conditions they live in, and those affecting other river species—San Diego Zoo Global has pledged an ongoing commitment of funds to field conservation of platypuses. San Diego Zoo Global, the University of Melbourne and the environmental research and conservation group cesar have teamed up on a unique project designed to learn more about the elusive platypus and the threats to its survival. The project uses innovative technology, in which samples of water are tested for traces of environmental DNA (eDNA) to learn about the species present in freshwater ecosystems.

Platypus populations were considered to be at risk before the 2019 wildfires that burned through Australia. The species’ status was recently uplisted by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, to Near Threatened. Unfortunately, the region that burned was considered to be a stronghold for the platypus, with some of the healthiest populations in the country. With funding raised by San Diego Zoo Global’s Australian Wildfire Relief Campaign, researchers are now also going to assess the status of the platypus population in the wake of the fires, with the hope of guiding future recovery for the species.

In addition to the Platypus Cam presented by the Animal Crossing: New Horizons game, San Diego Zoo Global offers 12 other live wildlife cams where online visitors can check in on their favorite animals and enjoy daily updates . Recently, the San Diego Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Park have seen a 1,000% increase on average in online webcam viewership. The live wildlife cams are reaching audiences around the world—from the United States to the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Brazil, Mexico, India, Romania, Saudi Arabia, Ireland, Germany and China, #WereHereTogether provides a wide array of supplemental curriculum on wildlife , plants and animals , and habitats, with engaging content for students in grades K–12, animal care professionals, educators, parents and fans alike, including:

- K–5 Students: Youngsters can jump right into the world of wildlife with San Diego Zoo Kids video stories, hands-on activities and games, with links to live wildlife cams and information about how to be a superhero to help save species. Kids can also tune into the San Diego Zoo Kids YouTube Channel any time of day for dedicated wildlife content that is provided at children’s hospitals and Ronald McDonald Houses around the world, or visit the San Diego Zoo and Safari Park YouTube channels. ZOONOOZ Online also includes fascinating stories about wildlife and ongoing conservation projects around the world, with new features posted each week.

- Middle School and High School Students: Dig into science on the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research Science Blog , with posts that cover everything from what happens inside a pathology lab to information on interning with the alala education program in Hawaii. Or, become a “citizen scientist” and contribute valuable data to conservation researchers by counting, identifying and tracking burrowing owls, giraffes and other wildlife online, at San Diego Zoo Global’s Wildwatch Burrowing Owl and Wildwatch Kenya . Participants can help researchers by viewing and classifying wildlife images from remote trail cameras. In addition, San Diego Zoo Global Academy offers middle and high school teachers and students access to 22 free, self-paced online courses covering a variety of taxonomic groups and individual animal species, including monotremes. These fun, fast-paced, interactive courses are designed to be completed by students in as little as one to two hours. They include video, images and quizzes to teach students about mammals, birds, primates, bears, reptiles, monotremes, marsupials and more.

Anyone with a smartphone or computer can bring wildlife into their homes today, and engage using the hashtag #WereHereTogether. And for anyone who engages in online meetings via Zoom, San Diego Zoo Global has created new downloadable backgrounds featuring some of the most beloved animals. With just a click, you can add platypuses, hippos, rhinos and more to your meetings! Visit SDZSafariPark.org for more information, and to see the latest offerings in the We’re Here Together campaign. #WereHereTogether

Related Posts

Cute and Curious 9-day-old Southern White Rhino Explores Habitat

Condor Breeding Season 2018 Begins!

You’ve Got Meal!

Recommended.

The Hatch of 2020

- Wildlife Care

Rare Platypus On Display At San Diego Zoo Safari Park

A pair of platypuses were introduced to the public on Friday at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park.

The animals are the only platypuses on display outside of their native country.

The male and female have actually been living in San Diego for just over a month.

The Australian government donated the pair of unusual animals to the San Diego Zoo after more than a decade of negotiations.

“As the world’s only island continent we were surrounded by water for millions of years,” said Chelsey Martin, the consul general at the Australian embassy. “This means that our plants and animals have been able to evolve in an incredibly distinctive way.”

RELATED: Endangered Birds Released In Tijuana River Estuary

The platypuses come to San Diego from the Taronga Zoo in Sydney where they also shared an exhibit space.

“A platypus is a monotreme which means it is an egg-laying mammal," said Lori Hieber, a San Diego Zoo Safari Park lead mammal keeper. "They share that characteristic only with four species of echidna so they’re pretty unique.”

The animals live both in and out of the water.

“They’re small brown animals that tend to live in brown water,” Hieber said. “They’re nocturnal and crepuscular so they’re most active at night and during dusk and dawn so they’re very hard to find.”

And that makes putting them on display a challenge. But zoo officials came up with a solution. The day and night times are upside down in the exhibit. When it is light out the exhibit is dark and vice versa.

It has been more than 60 years since platypuses were on display in the United States.

Zoo officials are hopeful the animals will rear some young, but they said the pair has lived together for several years without producing any young.

Platypuses are big eaters, but their prey are small. They eat mostly insect larvae and crustaceans like crayfish. Sometimes, they eat worms, clams, aquatic snails, and tadpoles.

description

Filling the bill

A platypus is the only mammal with a bill. The dark gray skin on the bill is hairless and moist. Grooves along the sides of a platypus’s bill help it filter food from the water. A platypus grinds its food with tough pads in its bill; it has no teeth. A platypus spends 10 to 12 hours each day looking for food underwater.

It's electric!

Did you know that animals produce electric fields? Probably not, because the electrical fields an animal makes are too weak for us to feel. Platypuses are much better at detecting electricity than we are. Sense organs on a platypus’s bill detect even weak electrical fields—and help a platypus find its food.

Venomous males

Adult male platypuses have a venom gland in each thigh. The venom gland is connected to a small spur on its hind leg—think of a platypus’s spur as a tiny horn, about as long as your fingernail. Only males platypuses produce venom, and only during breeding season. As they fight for a chance to mate with a female, both males try to drive their sharp spurs into each other. The venom doesn’t kill a rival; it just slows him down for a while.

Night and day

Platypuses are active at night, when they are busy finding food in the water. During the daytime, a platypus hides in its burrow in an earthen stream bank. Inside a platypus burrow, tunnels lead to oval-shaped chambers.

At home with mom

A mother platypus lays one or two eggs and keeps them warm inside her nursery burrow. She curls up and nestles an egg between her body and her tail. About 10 days later, the baby platypus hatches. It is very tiny, naked, and blind—kind of like a gummy bear! Baby platypuses stay in nursery burrow for the first three or four months. Like other young mammals, they drink their mothers’ milk.

A mammal that lays eggs?

Platypuses are one of only five mammals that lay eggs. The other four are species of echidnas.

Cheeky fellows

A platypus's cheek pouches hold food while it dives.

Coming or going?

A platypus's hind feet point backward.

- Give Monthly

- San Diego Zoo

- Safari Park

- Special Experiences

- Plan Your Visit

- Renew/Rejoin

- Conservation

- Take Action

- Adventure Travel

Your symbolic adoption supports collaborative efforts to save platypuses. These Australian icons are one of the world’s only egg-laying mammals.

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance works with partners through our Australian forest conservation hub to protect platypuses and preserve their native freshwater habitats.

Conservation is at the heart of everything we do. As an ally, you offer hope to wildlife worldwide and we cannot thank you enough. Because when wildlife thrives, all life thrives.

Adoption Packages

$25 Virtual Platypus Adoption

Share your passion for wildlife with friends and family by sending your loved ones a Virtual Platypus Adoption. Your gift will be sent through email and will include a Virtual Platypus Adoption card! This option does not include a mailed adoption package.

$100 Platypus Adoption

Your generous gift fuels critical conservation worldwide and offers hope to the world’s most extraordinary wildlife, including platypuses. Your $100 Platypus Adoption package includes 1 soft 10” platypus plush, a 5” x 7” Platypus Adoption card, and a limited edition San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance pin.

$500 Platypus Adoption

$1,000 Platypus Adoption

Your generous gift fuels critical conservation worldwide and offers hope to the world's most extraordinary wildlife, including platypuses. Your $1,000 Platypus Adoption package includes 1 soft 10" platypus plush, a 5" x 7" Platypus Adoption card, a backpack, a beach towel, a thermos, a limited edition San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance pin, and a 50% discount gift voucher for one guest on select tours at the San Diego Zoo or Safari Park.

For questions on San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s Adoption Program, please contact us at [email protected] .

- San Diego Zoo Tickets

- Safari Park Tickets

San Diego Zoo Safari Park welcomes okapi calf to the herd

The as-yet-unnamed calf will be able to be viewed by safari park visitors daily starting in april in the safari park's african woods area, by eric s. page • published april 8, 2024 • updated on april 8, 2024 at 6:07 pm.

The number of okapis at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park increased by one recently with the birth of a male calf of the unique species nicknamed the "forest giraffe," it was announced Monday.

The as-yet-unnamed calf will be able to be viewed by safari park visitors daily starting in April in the safari park's African Woods area.

The calf was the first born to Mahameli (“Meli,” mother) and Mpangi (Mm-pong-ee, father). Zookeepers say the young buck nurses several times a day and "likes to run circles around his mom and even playfully kick her once in a while," the safari park said in a news release sent out on Monday. "He also started taste-testing the [vegetation in his habitat], following Meli’s lead."

A reclusive species rarely seen in the wild, Okapi are native to central Africa and were discovered by Europeans in 1901. Although often confused with a zebra due to the black and white striped patterns on its front and hind legs, the okapi is actually the closest living relative to the giraffe.

Get San Diego local news, weather forecasts, sports and lifestyle stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC San Diego newsletters.

Various causes, including habitat destructing and hunting, threaten the wild okapi in its native Central Africa, but, fortunately, "one-fifth of the okapi habitat within Africa’s Ituri Forest was designated as a wildlife reserve [in 1992,]" the news release also stated. "And since okapis are an 'umbrella species,' by aiding in their conservation, we also contribute to the protection of other wildlife that coexist in their African habitat."

This article tagged under:

- Help Center

- Plan Your Visit

- Places To Stay

- Special Experiences

- Youth Programs

- Student & Youth Groups

- Events & Catering

- Live Cameras

- Our Mission

Hike to Hippos

$49 & up*.

Prices vary by season and days of the week. Please click BUY NOW to check prices by date. Admission is separate and required, and may be added before checkout.

At a Glance

- Ages 5 & up; recommended for 12 and older

- Offered daily

Wear comfortable walking shoes. Maximum of 2 children per adult; ages 15 and younger must be accompanied by a paid adult. Ages 5 and up; recommended for ages 12 and older. Walking is required; guests will be on their feet for one hour, including walking uphill. Guests must be able to traverse hills and steep inclines. Wear comfortable walking shoes. Pathways are paved, and the route is wheelchair accessible. Please notify us if special accommodations are needed. Some tours require walking to visit several exclusive areas. Maximum of two children per adult; children 15 years old and younger must be accompanied by a paid adult. All tour participants require a ticket, regardless of age.

- Ages 5 & up; recommended for ages 12 & up

- Offered select dates

Maximum of 2 children per adult; ages 15 and younger must be accompanied by a paid adult. Ages 5 and up; recommended for ages 12 and older.

Walking is required; guests will be on their feet for one hour, including walking uphill. Guests must be able to traverse hills and steep inclines. Wear comfortable walking shoes.

Pathways are paved, and the route is wheelchair accessible. Please notify us if special accommodations are needed.

Change/Cancellation: Reservations may be changed up to 5 days before the program and will be subject to a $15 Administrative Change Fee. Less than 5 days, changes not permitted. Cancellations received 5 days before scheduled program are subject to a $25 Cancellation Fee. Less than 5 days, payment is non-refundable.

Skip the snooze and join us for an unforgettable early morning adventure! Led by our wildlife experts, this 60-minute tour introduces you to both pint-sized pygmy hippos and iconic river hippos. Strap on your sturdiest sneakers and kick-start your day with this unique hike at the San Diego Zoo!

You May Also Like

Animals in Action Experience

Bring your camera to this fun and interactive experience, as we bring the animals out to you for an up-close view.

Let us answer your questions and help create your day at the Zoo!

PREFERRED HOTELS

Picture Your Special Day at the Park!

Save the Chubby Unicorns

Gorilla Shadow

Okapi calf born at San Diego Zoo Safari Park

ESCONDIDO, Calif. (FOX 5/KUSI) — The okapi family at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park has just welcomed a new addition.

A male calf was born to first-time parents, Mahameli and Mpangi. In a release Monday, the zoo said Mahameli (Meli), the mother, can often be seen basking in the sun with her unnamed calf.

According to the zoo , okapis have black-and-white striped hindquarters, similar to zebras, although they’re actually related to the giraffe. Okapis are native to the deep forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and are known to be elusive and highly alert.

Check out the photo gallery of the San Diego Zoo Safari Park’s new okapi calf above.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to FOX 5 San Diego & KUSI News.

- Blog Archives

- Copyright | Cookie policy

- Literature

- (V)IPs Zoos

- Rest of the World

- Endangered Species

- Species Classification

- (V)IPs Evolution

- Latest Newsletter

- Newsletter Archive

- Subscription

- Video Gallery

Select a Zoo

Reviews — zoos in europe, history description, history documentary.

During the second half of the nineteenth century the first menageries in Moscow were established as entertainment facilities. The first was founded in 1855 by two Frenchmen (names unknown), while the Kreuzberg family owned a private menagerie that opened its door to the public in 1862 . Together these animal collections formed the heart of the Moscow Zoological Garden founded by the Society for Acclimatization of Plants and Animals, which was established by professors of the Moscow State University. The initial idea for such a zoological garden came in 1857 , but it took the Society, including one of its founding fathers professor Anatoly P. Bogdanov, until 1863 to be able to buy property for the future zoo. The Zoo was opened to visitors on 13 February 1864 at the location where it still exists until this very day. On opening day 287 animals were on display, of which 134 were domestic animals, while the others were exotic specimens such as tigers, lions, jaguar, leopard and rhino.

In those days it was an unique experiment to create “a living museum outdoors,” as professor Bogdanov said, in such severe climatic conditions of central Russia. The primary purpose of the Zoological Garden according to the members of the Society was:

to collect alive specimens of higher vertebrates ( firstly — the animals of Russian fauna) for scientific observations;

to establish a collection of typical animals that could serve educational purposes, i.e. distribution of zoological knowledge among the wide public communities;

to carry out scientific experiments and observations of important animals, especially domestic animals of Russian breeds.

The Zoo was financed by the entrance fees and private donations, including contributions by members of the imperial family. In the first years the annual number of visitors grew up to ten thousands. Nevertheless, the incomes did not cover the expenses and the Moscow City Council refused to give financial support. So, the Zoo went into private hands of the Ryabinins’ family in 1874 . They transformed the Zoo into an amusement park and in three years time ruined the place. In 1878 the Zoo was run by the Society for Acclimatization of Plants and Animals again, including fund raising activities. This time the Society was able to manage the Zoo successfully, and even to buy a number of animals. But in the turmoil of the Revolution of 1905 the Zoo was severely damaged: the buildings were ruined, the library was set on fire, many animals perished. So, for the second time the Society was forced to turn over the Zoo to private owners.

Then in 1914 World War I broke out. For the Zoo this meant that in the autumn of 1914 the only building that remain to this day was transformed from the director’s premises to a hospital for wounded WWI soldiers. The WWI impact compounded Russia’s suffering from a number of economic and social problems, which resulted first in the 1917 February revolution followed by the October revolution. In the aftermath of the Great October Socialist Revolution of 1917 and the fall of the Russian Empire, the Society ceased to exist, and in 1919 the Zoological Garden was declared national property and transferred under the responsibility of the ministry of Culture of the communist Moscow parliament, the Mossovet. In 1922 it was transferred to the authority of Moscow City Council and since then it has been supported by the City Authorities. Construction work began on the Zoo grounds. The Zoological Garden premises almost doubled in size with the establishment of the ‘New’ territory on the opposite side of Bolshaya Gruzinskaya street. New exhibits, which followed the principle of Carl Hagenbeck’s bar-less enclosure design were established. One of the most interesting exhibits of the Zoo called ‘Animal Island’ still exists. It was a high stony rock surrounded by a deep water ditch that separated the visitors from bears, tigers, lions and other large predators on the ‘Island’. The total size at the time was nearly 18 hectares.

In 1926 the Zoological Garden was renamed ‘Zoological Park’. At that time the range of activities extended, the animal collection increased considerably with expeditions collecting wildlife in Central Asia, the Far East and the Caucasus. New departments were established, focussed on for instance scientific research, education, veterinary science and nutrition. In those same years Moscow Zoo was the first zoo in the world where educational activities were the main priority.

In 1924 the Zoo had established the Young Biologists Club that gathered like-minded young people that joined in real scientific research. Many of them became a Zoo employee. The Club was founded by Petr Manteifel, who also was the pioneer father of the science called ‘zoo biology’. Manteifel and his young biologists discovered a way of artificial breeding sables (Martes zibellina), which were on the verge of extinction due to man’s insatiable pursuit for its expensive fur. In the 1930 s during Stalin’s great purge many members of the Young Biologists Club were arrested accused of spreading anti-soviet propaganda and liberal-minded ideas and having contact with German colleagues at Berlin zoo, some were even executed as foreign spies. The Club was considered a non-governmental organisation beyond the direct control of the authorities, which in fact was partly true because the Club was a real democracy, with membership available to all.

Although many animals were evacuated and many of the zoo staff were called to arms at the beginning of World War II the Zoo was kept open. Of the 750 employees at autumn 1941 only 220 remained on the staff, most of them women. Getting enough food for the animals was a constant challenge, for instance carcasses of killed horse at the battlefield around Moscow were brought to the zoo. More than six million people visited the Zoo from 1941 to 1945 to enjoy the sights of animals that had remained.

At wartime the scientific work proceeded, perhaps even more intense than before or after the war. The scientific staff worked especially on development of antibiotics. But the most important mission of the Zoo during the war was to give people hope. It produced the illusion of a peaceful life until people survived through the desperation of the war with the Red Army soldiers as the most frequent visitors of the Zoo. Which were given the pleasure of watching newborn offspring even during the war.

During the soviet union period ( 1922 − 1991 ) not many highly ranked people cared about the zoo — no soviet leader had any interest in it. The city encroached on the zoo premises, while the zoo needed additional space for the ever expanding zoo population of animals. Because the breeding results were still excellent.

The Zoo lived up to the goal it had set for itself and made educational activities the main priority. Zoo staff distributed knowledge in the field of natural history and tried to raise the public awareness and concern about the necessity for wildlife conservation. The zoo assisted schoolchildren and students with studying biology, actively participated in scientific research, and actively contributed to scientific publications. So, the Zoo became one of the larger scientific institutions in Moscow. And of course it still was the favourite recreational place for Moscow citizens and those who visited the city.

As off 1974 when Igos Sosnovsky retired as director and his successor Vladimir Spitsyn took over Moscow Zoo became part of the international zoo community again. Sosnovsky as a WWII veteran hadn’t been able to brush aside the fear of repression and avoided all international contacts for some reason. Spitsyn restored all international activities from before the war and the Zoo became member of many European and International Breeding Programmes in which it exchanged its rare and endangered animals, shared experience and information.

Although already in the 1970 s improvement of all zoo facilities was needed and ideas of a new zoo in another region of Moscow were launched, nothing happened due to local economical and social problems. By the end of the 1980 s the Zoo’s condition became alarming. Facilities were deteriorating, enclosures were dilapidated and technical equipment needed to be replaced as well. And while a few improvements had been achieved — such as a partial renovation of the main entrance, the monkey house and lion house — urgent measures were still needed.

Then, in 1992 the new Moscow government made a decision to start the most ambitious reconstruction project in Moscow Zoo’s history with the first stage of the project to be completed by 1997 , when the 850 th anniversary of the City would be celebrated. Anatoly A. Andreev who had been involved in the Zoo’s design and architecture since the 1970 s headed the team of architects. The project’s renovation objectives were focussed at (a) preservation or partial renovation of the historically valuable buildings and existing pools, (b) reduction of the noise from the surrounding streets, © connection of the Old and the New territory via a footbridge, and (d) expansion of the Old territory by incorporating adjacent areas and buildings.

Besides the preservation and renovation of almost all important zoo constructions, including the ones that actually were dilapidated, many new enclosures and facilities were built. Already in 1993 the footbridge that connected the Old and New territory was completed. It allowed visitors to avoid crossing the busy B. Gruzinskaya street with its heavy traffic. In 1993 other constructions were completed as well, such as an enclosure for large birds of prey and a complex of enclosures for feline species, including leopards, Pallas’ cats and lynx. Next, the Hagenbeck-style ‘Animal Island’, one of the most remarkable exhibits in the New territory, was renovated. The historic appearance with enclosures that resembled the natural habitats of Amur tiger, striped hyena, African wild dog and Asian black bear was preserved. Later they introduced Asian lions in one of the enclosures around the large rock in the centre of the ‘island’. During the renovation they created the Exotarium, which held several aquariums, inside the rock on the second floor.

The following years many more enclosures were renovated, besides the new research and veterinarian facilities that were put into operation in 1994 . In 1996 , the main entrance itself (featuring a small artificial waterfall) was reconstructed. The same year the old, dilapidated elephant complex was demolished and a new elephant house was erected at the same spot, while the inhabitants (four African elephants and four Asian elephants) were temporarily moved to a a former tram depot that was completely renovated and specially equipped. A new children’s zoo was opened in the New territory, including a children’s theatre that organises shows with educational elements. And besides several aviaries, a pavilion for water birds was built on the shore of the large pond in the New territory.

Although in those days 4 additional hectares of space was added to the former existing 18 hectares, the Zoo still lacked space to create favourable conditions for their species to breed. And its location in the centre of Moscow didn’t contribute to the favourable breeding conditions they wanted of course. Therefore, the 200 hectares area near the city of Volokolamsk (about 100 km from Moscow) that was given to the Zoo in 1996 for the establishment of a breeding station was very much welcomed (see also Breeding Centre ).

The first major stage of the general reconstruction of the Moscow zoo represents a unique event. Not only over 50 facilities have been renovated ( 90 % of all existing facilities) and newly built, but it was achieved in such a short period of time. But maintenance and small and larger refurbishment is ongoing business in a zoo. So, i n 2002 , the Moscow City Government and the City Council allocated the necessary funds to start construction of a new pavilion for the Asian elephants. In 2003 the three elephants could move house already, and in spring 2009 , the first newborn elephant calf was welcomed.

The Moscow Zoological Park has come a long way from the small zoological garden it was to the large institution of scientific research, education, conservation and recreation it is today. And due to the dynamics of the standards used in the zoo community regarding animal health and welfare, Moscow Zoo is constantly improving its facilities, also during 2014 celebrating its 150 th anniversary.

(Source: Moscow Zoo website; Zoo with a Human Face, to the 150 th anniversary of the Moscow Zoo — a documentary by Darya Violina and Sergei Pavlovsky, 2014 ; Zoo and Aquarium History by Vernon N. Kisling, Jr., 2001 ; Wikipedia)

An account of 150 years of history of the Moscow Zoo

(A documentary by Darya Violina and Sergei Pavlovsky)

The history of Moscow Zoo shown through the perspective of the lives of the people who have been important to the Zoo’s development and continuous progress over those many years since 1864 . Thousands of photographs, hundreds of chronicles, accounts and recollections that have preserved the story that began so long ago, against all odds, and lasts uninterrupted to this day. A documentary about those who have devoted their lives to serving a noble and rewarding cause, those who have started from scratch, those who maintained that work and about those who revive the Zoo as off today.

(Source: sdpavlovskiy YouTube channel)

20 . 06 . 2014

Finally, Moscow Zoo is paid a visit. I have been looking forward to this for quite some time. It has been on my to-do list since I learnt about the large collection of feline species on display at the Zoo. So, I am here on this sunny day in June to satisfy my curiosity, in the year they celebrate the Zoo’s 150 th anniversary.

I am entering as one of the 1 , 5 million paying attendance yearly. Which is not even half of the total number of visitors a year. This is about 4 million, because there are specific categories (e.g. disabled, pensioners, children, students, etc.) for whom the admission is free.

OLD TERRITORY

I turn left after the main entrance to visit the large predator section of the Old territory. Not that only here you will find predators, but the greatest part of their predator collection is grouped in this section. I will come back to the grouping of Moscow Zoo’s animal collection later. After having walked along a fence that blocks most of the views on the work in progress at the lake I arrive at what they call here the ‘tropical cats’ section: Bengal tiger (unfortunately the genetically aberrant version — a white tiger), jaguar and cheetah. Both the tiger and the jaguar have their indoor enclosures in the same house built at the perimeter of the premises. The cheetahs have their shelter for the night and bad weather in their outdoor paddock, so that cannot be visited. The tiger and the jaguar however have interesting housing that serves the needs for both the cats and the visitors. The latter are pleased with Asian and South American (Inca) ornaments to make sure they understand the geographical origin of the species. While the walls have murals representing the species’ original habitat … Machu Pichu for the jaguar. The animals themselves have various enrichment features at their disposal, including high level observation posts, in rather small exhibits. The outdoor facilities for these two species are accessible from the indoors. It has natural vegetation, but not a lot. Likewise there are not a lot of options to shelter from extreme weather or loud crowds. Although the cats have access to several resting posts at different levels, these enclosures can do with some improvements — at least more vegetation — to make them better fit for purpose, in my opinion. The enormous exposure of the cats is also due to the fact that they use windows to separate animal from man along almost the total length of the enclosures.

When I walk the few steps to the entrance of the Bear House, which is like the jaguar and tiger indoor enclosure built at the edge of the Zoo grounds, I pass in between the Pallas’ cat exhibit and a second jaguar exhibit. The Pallas’ cat has a flat grassy area with three large trees, some shrubs and a potential pond (when filled with water) available in its outdoor enclosure. Windows all around and a wire mesh roof prevent the cat from fleeing this scenery that doesn’t resemble the cat’s original Himalyan habitat. Across the footpath there’s a jaguar enclosure that’s more interesting than the one directly neighbouring the tiger. This one has a small stream and loads of vegetation and a multilevel resting platform. Still the animal is quite exposed.

The Bear House provides a nice and secluded area where three adjacent bear enclosures houses sloth bear and spectacled bear. As a visitor you walk via a roofed corridor more or less in the dark along the enclosures having good views on the exhibit via man-sized windows. The enclosures have a dry shallow moat at the visitor’s side, but I don’t think this withhold the bears from coming close to the windows. The enclosures are small but almost completely filled with enrichment features including various platforms, a tree trunk structure, rubber hammocks and natural vegetation. Considering the design I think these enclosures offer peace and quiet for the bears, unless people start banging the windows of course.

In slightly larger enclosures they keep Amur leopard, snow leopard and cougar ( Puma concolor ). At all of these felid species enclosures the distance between the public barrier and the fence does allow contact when people lean far forward.

Further along the footpath around the corner the arctic fox and the dhole are housed in enclosures that have a similar interior design as those for the felids. Despite the fact that these species live under different natural circumstances in the wild (forest and tundra habitat respectively).

When I walk back to have a look at the large birds of prey aviary I cannot prevent myself to have a brief look at the giraffe enclosure as well. It’s obviously a relic of the past that is not fit for purpose anymore. Still they have one reticulated giraffe on display at a saddening small area. It loves to be fed by the public that doesn’t care about the warning not to feed the animals. On the other side of the building a similar pitiful situation for the single white-tailed gnu can be seen.

One of the most extraordinary group of species brought together on display can be found right after the row of predator enclosures. The maned wolf from South America has the red-necked wallaby and emu from Australia as neighbour. But also in the same area the African wild dog is on display as well as white-tailed gnu (Africa) and kiang (Asia) in the row of stables along the rim of the premises.

The raccoon exhibit is worth mentioning considering the aforementioned accident risks. It has a very typical enclosure design with electrical wire on top of windows surrounding the entire exhibit. The electrical wire is within reach of the public. So, there are numerous warning signs! But why they installed electrical wire on top of windows that are unclimbable for raccoons? To keep out the public perhaps?

In the bird house, in the far end corner from the main entrance, birds from all geographical regions are grouped together, including Humboldt penguin and African penguin. The house consists of two part with one part half empty, and has also very common species on display, such as wild turkey, common pheasant and European hedgehog. Outside this building several aviaries comprise a large array of parrot species (South America and Australia).

Proceeding with my tour around the Old territory I have a look at the Asian elephant house and its surrounding grounds. The fancy steel with blue details of the elephant house doesn’t appeal to me, but that is just a matter of taste. It is definitely the most modern exhibit in the Zoo I’ve seen yet, in style and in size, with a nice pool at the visitor’s side.

I skip the reptile house to save some time, and money too, because an additional fee complies. So I walk straight to another modern enclosure — the bar-less and moated wolf exhibit. Although it has a Hagenbeck-style design, the space available for the wolves is ridiculously small. The wolves will never be able to cross the water-filled moat and climb the wall and thus break out, still there is impressive electrical wiring in place on top of the wall. Again, probably to keep out the public.

Making my way to the footbridge that connects the Old and New territory I pass along a very old-fashioned row of enclosures built in a semicircle in front of the 16 metres high sculpture by Zurab Tsereteli called ‘Tree of Fairy Tales’, 1996 . The enclosures house several species of mustelidae (sable, European polecat, stone marten), as well as African wild cats. Then followed by several aviaries again. At this point I am really lost regarding the way they group the Zoo’s animal collection.

NEW TERRITORY

Proceeding clockwise I find the doors of the Tropical House closed for renovation. So, no butterflies for me this time. But in one of the two spacious aviaries around this house I discover several ducks, such as the mandarin duck and the black-bellied whistling duck, together with the common kestrel ( Falco tinnunculus ), though neither rare nor endangered.

Then a rather special exhibit appears, the Animal Island, which was developed in the 1920 s as one of the first Hagenbeck-style enclosures in the New territory. Although it took some renovation activities it still exists to this very day. In the centre of this moated area they have erected a fake ruined fortress, which serves as the background for the species in the surrounding exhibits. These bar-less exhibits have a more modern appearance but it isn’t necessarily an improvement for the animals. For instance the Asian black bear has a bare environment with minor enrichment available and no vegetation, but the brown bear is even worse off in a similar enclosure but next to nothing of enrichment features. The tundra wolf ( Canis lupus alba ) and the striped hyena have a little better place at their disposal, but the Asian lions have by far the best enclosure. They have several resting platforms, trees and a stream that ends in the moat. Again to save time I skip an exhibit. This time the Exotarium with its aquariums that has been created inside the ruined fortress and by the way requires an additional fee to get in.

One of the rare areas in Moscow Zoo where you find mixed-species exhibits is called ‘Fauna of the Savannah’. It has a South American section with capybara vicuna and guanaco, and — very importantly — a large pool at the disposal of the largest rodent on earth. Though absolutely not endangered, these water-loving capybaras should have access to water at all times, in my opinion. The real savannah area with African species has several enclosures. A mixed species exhibit with sable antelope and dikdik. And Grevy’s zebra together with ostrich and giraffe. Also this time there’s only one giraffe in the paddock. The location of the meerkat enclosure is well chosen, because when they sit on top of one of their hills they can watch the other animals. Although it is the largest and probably the most modern facility at the Moscow Zoo I still think it is disappointingly mediocre compared to other zoos I have seen in Europe and North America.

Before I go to the primate section I buy myself an ice cream and walk along the horse stables on the eastern edge of the New territory premises. Looking for an answer to the question “why are there horse stables at this place?” The question still waits for an answer.

At Moscow Zoo they keep both Sumatran as Bornean orangutans, which is quite unusual. The outdoors for the five individuals, including 2 young, of the Sumatran species looks impressive due to the enormously high rock face at the rear. The wall looks extra impressive because it is rather close to the viewing windows. Unfortunately, the exhibit lacks trees and vegetation other than grass while the enrichment is scant and I don’t see puzzle feeders. The Bornean orangutans have a similar outdoor enclosure, but it is suggested that olive baboons ( Papio anubis ) are on display here as well. It could be that they alternate in the same outdoor enclosure, but this is not very clear.

The western lowland gorillas also have a similar outdoor enclosure design due to which the animals are enormously exposed to the inquisitive public. Considering the number of youngsters Moscow Zoo appears to be having good results breeding orangutans and gorillas.

Indoors, all the great ape exhibits have much enrichment and jungle-like murals, but the agile gibbon has even more enrichment inside. I haven’t seen a specific outdoor enclosure for the agile gibbon but it could be possible that it alternates with the Sumatran orangutans. Only this enclosure lacks high trees or other options for the gibbon to brachiate, which is its natural behaviour in the canopy of the gibbon’s native habitat, the rainforests of southeast Asia.

The terrarium building, located behind the Primate House, is beautifully decorated with little mosaic tiles. They have the usual row of exhibits, but in this case especially the larger reptiles and tortoises (python, crocodiles, alligator, tortoise) are kept. And outside they have two giant tortoise species, the Aldabra and the Galapagos tortoise.

On my return to the exit I pass the exhibits of a few of the many predator species they have on display at Moscow Zoo. The polar bear is provided with a big heap of artificial ice, but that’s about it when it comes to enrichment, though there are some plastic drums to play with. The enclosure as such is the prototype of polar bear enclosures worldwide, rear wall of cement and large bricks, concrete floor, large and deep water-filled moat. Unfortunately, again here the annoying reflecting windows. The yellow-throated marten I do not see, and the same counts for the Eurasian otter in its large elongated outdoor exhibit with a shallow pool along the whole length. It must be great to see the submerged otters swim in this pool.

Conclusion There are several ways to group a collection of animals which can support a zoo’s educational efforts. Of course, some people just come to the zoo to be entertained, but when an individual is ready to learn some things the worst thing you can do is confuse him or her. And to be fairly honest, confusing it is. Sometimes they group the collection according their taxonomic tree, which is the case with the felids, the bird species and the primates. Then again they have decided to present the collection by geographical origin, like in the ‘Fauna of the Savannah’, or according original habitat like the mountain-dwelling tur and markhor. And at some point they just make a mess of the grouping, for instance in the area with the maned wolf, the red-necked wallaby and others. In the end it seems the Zoo just want to have on display as many species as possible, because all species that live in herds they keep them in small numbers. I do understand that it is not easy, requires tough decisions and certainly is not cheap to rearrange your entire collection, especially when it is that huge as it is here at Moscow Zoo. Anyway, further renovation is foreseen and probably some rethinking as well.

I hope that they get rid of all these windows they have at so many exhibits. For some situations it is inevitable I understand, but I sincerely hope they will return to the original Hagenbeck idea of bar-less enclosures, taking into account modern husbandry standards of course. As the position of the sun makes it sometimes hard to get even the slightest glimpse of the animals due to the reflections in the windows. And last but not least they have the tendency to have windows all around or at more than 50 percent of the perimeter of an enclosure. Most of the time leading to more exposure of the animals to the public and possible unrest.

Sumatran orangutan youngsters at Moscow Zoo

Just another day at the zoo for these orangutans ( Pongo abelii ) — nothing much exciting going on in this safe and secure environment. But wouldn’t it be nice to see them swinging and romping in the forests of Sumatra.….

Raccoons at Moscow Zoo

Raccoons are known for their habit to clean their food in the water before eating it. It seems they also want to have a clean ball before playing with it.

Breeding Centre

Information and education, zoo details, breeding farm.

The Moscow Zoo has always been trying to create the most favourable conditions for their animals to fulfil their basic needs. Not only for animal health and welfare purposes but also to breed the animals successfully. These specific breeding conditions could not be achieved due to its location in the City centre and the lack of space. In 1996 the Zoo came into possession of an area of 200 hectares near the city of Volokolamsk (about 100 km from Moscow). In this picturesque hilly area of the former quarries of the Sychovo mining factory, with streams, springs and artificial ponds better opportunities were available for breeding various — predominantly rare — species of animals.

The main goals of the Breeding Centre, besides maintaining rare and endangered species of animals, are establishing breeding pairs and groups and developing new husbandry methods. Since excessive disturbance is likely to have adverse effect on the breeding efforts, the actual Breeding Centre is not open to the public.

The construction of the Breeding Centre started in March 1996 . The first inhabitants of the Centre were birds of prey and waterfowl and they have been successfully breeding birds ever since. The collection of waterfowl has grown notably since the beginning. Apart from the numerous mallards and ruddy shelducks, the inhabitants of the ponds include pintails, pochards, tufted ducks and black geese of the genus Branta. Bewick’s swans are thriving, raising their chicks every year. Japanese, white-naped and Siberian cranes are also breeding successfully and many other species, including parrots. The breeding centre for birds of prey is continuously expanding, with Himalayan griffon vultures, golden eagles, imperial eagles, Steller’s sea eagles, and black vultures among its most prominent inhabitants. Regular breeding has also been achieved in saker falcons ( Falco cherrug ).

They keep carnivorous mammals as well at the Breeding Centre. These include endangered species such as Amur leopard, Pallas’ cat, cheetah, Amur tiger, dhole, wolverine, and yellow-throated marten. Of these species the Amur leopard is listed Critically Endangered according the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ , with about 45 individuals left in the wild. The Zoo’s track record says they have produced offspring from Pallas’ cat, dhole, yellow-throated marten, and Amur tiger.

For the ungulates that are kept at the Centre the environment is almost ideal. There are bactrian camels as well as kiangs, Saiga antelopes, blue sheep and vicunas. Hoofed animals originating from mountainous areas have large paddocks at their disposal that are situated on the slopes of the surrounding hills, more or less similar to their natural habitat.

Besides the more rare and endangered species the Centre also has an interesting collection of domestic hens, a horse stable and a dog-breeding centre, mainly for the breeding of Central Asian sheep dogs. Furthermore, there is a small quail farm and a poultry farm with layer hens.

Moreover a subsidiary farm in Lotoshino houses some cattle, smaller livestock, and the main herd of bactrian camels and yaks. The area of the subsidiary farm is about 51 hectares and it comprises hayfields, pastures, a sheepfold and an apiary. Most importantly it provides the Moscow Zoo with ecological feed for its animals.

The Breeding Centre’s collection comprises 10 species of carnivores, 6 species of ungulates, 74 species of birds and a great number of domestic animals, but the collection is expanding constantly. Although it is still closed to visitors, the Zoo’s goal is to open part of the farm (as they call the Breeding Centre themselves) to outside visitors soon. They plan to create an additional safari park at the location of the Breeding Centre.

(Source: Moscow Zoo website; Zoo with a Human Face, to the 150 th anniversary of the Moscow Zoo — a documentary by Darya Violina and Sergei Pavlovsky, 2014 )

Information panels and Education at the Zoo

First thing to be noticed of course is that the information on the panels around Moscow Zoo is given in the Russian language. And no other language. This is not unexpected as most of the information provided in Moscow is only in Russian. Fortunately, the name of the species on display is given in English as well, together with its scientific name. As far as I can tell and understand no information is provided on the species conservation status (or IUCN Red List status). On the new revamped website this information is available but only in Russian and no icons or logos are used, so you have to rely on machine translation services. The panels show geographic maps of the species distribution and sometimes the IUCN status and if the species is part of EEP /ESB, as well. But this is not done consistently, and I am not sure how reliable the information is. Nevertheless I have been able to find on the internet a list of species that represent the Moscow Zoo contribution to the European Endangered species Programmes (EEPs).

There is also a zoo school that is primarily focussed on children, and I assume that the Young Biologists Club still exist. Foremost because it has been very successfully delivering a range of important staff members over the years.

- Directions

directions to Moscow Zoo

Address : B. Gruzinskaya 1 123242 Moscow Russia

public transport

The metro system can be quite intimidating for foreigners because of the language issue, but I can assure you it is the best way of navigating the city. The metro stations are the most beautiful I’ve ever seen and buying tickets can be done using sign language (see the tripadvisor website how it is done). When you are not able to decipher the Cyrillic alphabet on the fly it is best to prepare your metro trip beforehand and make sure that you know how many stops you have to travel from the departure station to your destination, including transfer stations. Another way of travel support is the Art-Lebedev metro map , which has the names of the stations both in Russian and English mentioned. The most fancy way however is by using the Russian metro app on your smartphone. The Yandex.Metro app — provides a bilingual metro map which can even build connection routes for you and estimate travel times.

Moscow Zoo’s main entrance is conveniently located right across from the Krasnopresnenskaya metro station on the Brown Circular line (no. 5 ). Also the Barrikadnaya metro station is rather close to the main entrance, Purple line (no. 7 ).

by bicycle

As mentioned already Moscow is a very large city. So, it really depends on how close you already are to the Zoo if cycling could be an option. The obvious challenge is the traffic which has grown dramatically in recent years — the centre of Moscow is a non-stop traffic jam. Furthermore the poor driving habits of Moscow motorists are notorious, from road rage to rear-ending. In addition, knee-deep snow and the grimy slush that inevitably follows during the long and fearsome winters doesn’t make cycling in Moscow a very attractive mode of transport. Nevertheless the City Council tries to make the city more bike-friendly with a bike rental scheme like in many major cities around the world. I decided to use the metro.

There is no dedicated parking available at the Zoo, but if you really want to drive yourself you can get directions below by providing your point of departure.

From : -- Choose source -- Moscow Zoo or

Download the zoo map here .

Goal: 7000 tigers in the wild

“ Tiger map” ( CC BY 2 . 5 ) by Sanderson et al., 2006 .

Latest Additions

Tallinn zoological gardens, tallinna loomaaed, stadt haag zoo, tierpark stadt haag, salzburg zoo, krefeld zoo, cerza zoo, cerza parc zoologique lisieux, bratislava zoo, rheine zoo, naturzoo rheine.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Platypus Cam. You're watching a live stream of the Safari Park's platypuses—the only ones in the US. These special animals serve as ambassadors for the species outside of their native Australia and communicate the importance of fresh water for both humans and wildlife, and we're honored to be entrusted with their care. Learn more about ...

The platypus is a monotreme (like the echidna), which lays eggs, incubates them, and nurses its young when they hatch. Found only in Australia (in Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, and Tasmania), the platypus lives in freshwater habitats, including streams and ponds. It forages about 12 hours a day, eating shellfish, worms, and insect ...

The San Diego Zoo Safari Park is currently the only zoo outside Australia to house platypuses. When two platypuses—a male named Birrarung and a female named Eve—arrived in San Diego in October 2019, it was the first time in more than 50 years that platypuses were cared for outside of Australia.

Platypus Cam. You're watching a live stream of the Safari Park's platypuses—the only ones in the US. These special animals serve as ambassadors for the species outside of their native Australia and communicate the importance of fresh water for both humans and wildlife, and we're honored to be entrusted with their care. You're watching a ...

San Diego Zoo Safari Park ... New Horizons game provides livestreaming video of the Safari Park's platypus pair as they swim and frolic in their world-class habitat—including three pools, naturalistic river banks, extensive tunnels and nesting areas. The Animal Crossing: New Horizons game is available on the Nintendo Switch system and ...

The San Diego Zoo Safari Park announced the arrival of two platypuses from Australia and the official opening of the Nelson M. Millsberg Platypus Habitat at the Safari Park's Walkabout Australia earlier today (Nov. 22, 2019). The two... #platypuses #SanDiegoZooSafariPark #walkaboutaustralia

The San Diego Zoo Safari Park is currently the only zoo outside of Australia to house platypuses—and this is the first time in more than 50 years that platypuses have been cared for outside of Australia. The Nelson M. Millsberg Platypus Habitat at the Safari Park's Walkabout Australia officially opened Nov. 22, 2019.

Birra is an early, eager riser. In the wild, platypuses sleep during the daytime, and are most active at dawn and dusk. At the San Diego Zoo Safari Park, we set up our lighting schedule inside the platypus exhibit so that "daytime" starts at around 10 p.m., and "sunset" starts around 8 a.m. When our platypuses start to see the lights ...

The two platypuses featured on the cam—an 8-year-old male named Birrarung and a 15-year-old female named Eve—serve as ambassadors for the species outside of their native Australia. The San Diego Zoo Safari Park is currently the only zoo outside of Australia to house platypuses.

The only two platypuses in the world, outside of their native Australia, now reside in San Diego. It marks the first time in 60 years that platypuses are on ...

Platypus: Freshwater Wonders. IUCN Conservation Status: Near Threatened. ... "Having platypuses at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park allows us to broaden the work of Australian zoos to raise awareness for the unique species they work so hard to protect. Caring for these two platypuses, and sharing them with our guests, is a great responsibility ...

Sleeping in. style Every morning, when the Safari Park's animal care specialists arrive at the platypus habitat, they try hard not to wake the animals. They quietly peek in the nest boxes to check on the snoozing platypuses. The female, Eve, likes to curl up under her bedding. The male, Birra, sleeps on top of his towels.

A platypus on display at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park on Nov. 22, 2019. This is one of two platypuses that were flown to the U.S. from their home at Australia's Taronga Zoo in Sydney. A pair of ...

Filling the bill. A platypus is the only mammal with a bill. The dark gray skin on the bill is hairless and moist. Grooves along the sides of a platypus's bill help it filter food from the water. A platypus grinds its food with tough pads in its bill; it has no teeth. A platypus spends 10 to 12 hours each day looking for food underwater.

San Diego Zoo Safari Park is the only zoo in the United States that displays platypus and this was my first time seeing one! They are a very unique semi-aqua...

Your $1,000 Platypus Adoption package includes 1 soft 10" platypus plush, a 5" x 7" Platypus Adoption card, a backpack, a beach towel, a thermos, a limited edition San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance pin, and a 50% discount gift voucher for one guest on select tours at the San Diego Zoo or Safari Park.

The as-yet-unnamed calf will be able to be viewed by safari park visitors daily starting in April in the safari park's African Woods area By Eric S. Page • Published 14 seconds ago San Diego Zoo

Updated: Apr 2, 2024 / 08:51 PM PDT. ESCONDIDO, Calif. (FOX 5/KUSI) — Looks can be deceiving, and that is the case for one animal at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park. Meg, a black-footed cat, is ...

April 8 (UPI) -- The San Diego Zoo Safari Park announced the birth of a male okapi, the only living relative of the giraffe. The okapi, also sometimes known as a "forest giraffe" or "zebra giraffe ...

Hike to Hippos. BUY NOW. Ages 5 & up; recommended for ages 12 & up. $49 and up. Offered select dates. 60 minutes. View Age/Safety Restrictions. Maximum of 2 children per adult; ages 15 and younger must be accompanied by a paid adult. Ages 5 and up; recommended for ages 12 and older.

ESCONDIDO, Calif. (FOX 5/KUSI) — The okapi family at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park has just welcomed a new addition. A male calf was born to first-time parents, Mahameli and Mpangi. In a release ...

Reviews — Zoos in Europe. Moscow Zoo. During the second half of the nineteenth century the first menageries in Moscow were established as entertainment facilities. The first was founded in 1855 by two Frenchmen (names unknown), while the Kreuzberg family owned a private menagerie that opened its door to the public in ...

We have a newborn takin! We're not sure about the sex yet, but a baby takin is always good news. Takins are rare animals in European zoos, especially this very subspecies — Sichuan takin. The animal is on the IUCN Red List. VENOMOUS BEAUTY.

Tuscany Day Trip from Florence: Siena, San Gimignano, Pisa and Lunch at a Winery. 14,396. from $156.90. Perth, Western Australia. Pinnacles Desert Sunset Stargazing Tour. 626. from $163.23. Free cancellation ... San Diego Zoo Safari Park; London Natural History Museum; Xplor Park; Stonehenge; Öresund Bridge; Distillery Historic District; El ...