The Garden Party

By katherine mansfield, the garden party summary and analysis of "the voyage".

Fenella hurried toward the Picton boat with her father and Grandma. The night was mild, the sky starry but Fenella took little joy in it, sensing her Father’s unease. Her Grandma’s fancy umbrella with the swan head handle was tucked into the luggage Fenella had strapped to her back. The swan head pecked her repeatedly on the shoulder as if it too wanted her to hurry.

A whistle on the large boat sounded just as they arrived at the Old Wharf harbor. The Picton boat was beaded with light and Fenella thought it belonged more to the sky than the sea. She followed her family up the gangway and listened as her Father, Frank, asked after their cabin tickets. Fenella was not deceived by his stern tone of voice and was concerned for him; he looked sad and tired. She was surprised; however, when he hugged his mother close and wished her a safe journey and she in turn held his face in her hands and lovingly called him “my own brave son” (103). Fenella turned away and chocked down her own sadness so they would not see her tears.

Fenella’s father kissed her cheek and told her to be a good girl but she grabbed his lapels in desperation and asked how long she was going to be away. He would not look at her and shook her off gently, pressing a shilling into her hand. She took that as a bad sign and called after him but he had already turned to leave.

The boat was pulling away from the wharf and Fenella could no longer see her father on the dock. She turned to her Grandma who was sitting on their luggage and praying. Fenella waited respectfully for her to finish and then they went below to find their cabin. Her Grandma led the way, having traveled on the Picton boat many times before.

They carefully navigated the steep flight of stairs and hallways below deck until they came to their cabin. The stewardess, who knew Grandma, saw their black mourning clothes. Grandma said simply, “It was God’s will” (105) and the kind stewardess promised to look in on them later on. The cabin was very small and they undressed quickly and readied themselves for bed. Grandma put on a crocheted headscarf that Fenella’s mother had made before she died. Grandma smiled tenderly at Fenella, the headscarf a silent reminder of the grief they shared.

Soon they were both ready for bed and Fenella watched in disbelief as her Grandma nimbly climbed into the upper berth. The stewardess came to check on them and warned them that the boat might pitch. The words seemed to bring on the tilting of the boat and the slapping of water at her sides. Fenella worried that the umbrella would fall and break. Thinking along the same lines, Grandma asked the stewardess to lay the swan-neck umbrella flat so it would not be damaged. The stewardess did as she was asked and they spoke about the recent death of Fenella’s mother. The stewardess called Fenella a “poor little motherless mite” (107) but she wasn’t listening to their chatter and soon drifted off to sleep.

The next day dawned early and Fenella watched the harbor appear out of the portside window. She reflected on how sad her life had been after the death of her mother. Now she was traveling with her Grandma to a new life. She hoped her luck would change.

Once her Grandma woke, she told Fenella to make haste and they dressed quickly and left the cabin to go up on deck with their luggage. Fenella watched land slowly approach in the distance, the wind like ice against her skin. She could see umbrella ferns and little houses and soon the landing stage came along side of them.

“You’ve got my-”

“Yes, grandma” (108).

Mr. Penreddy, a friend of Grandma’s was guiding the landing stage closer, an old horse and cart waited onboard. Grandma was pleased to see Mr. Penreddy and as she and Fenella climbed into the cart he said that old Mr. Walter Crane, Grandma’s husband, was in good spirits and he had looked in on him the day before.

Once ashore, the horse pulled the cart off of the landing stage and toward one of the houses. They got down and Fenella walked up a little a path of round pebbles toward her grandparents’ home. Her Grandma opened the front door and called out to her husband who called back in a stifled voice “Is that you, Mary?” (108).

Grandma left Fenella in a side room where a white cat was sleeping. She petted the cat and listened to the voices of her grandparents. Her Grandma returned and Fenella went to see her Grandpa who lay in an immense bed, his rosy face and silver beard showing over the quilt.

He happily greeted her and she kissed him hello showing him the swan-head umbrella when he asked for it.

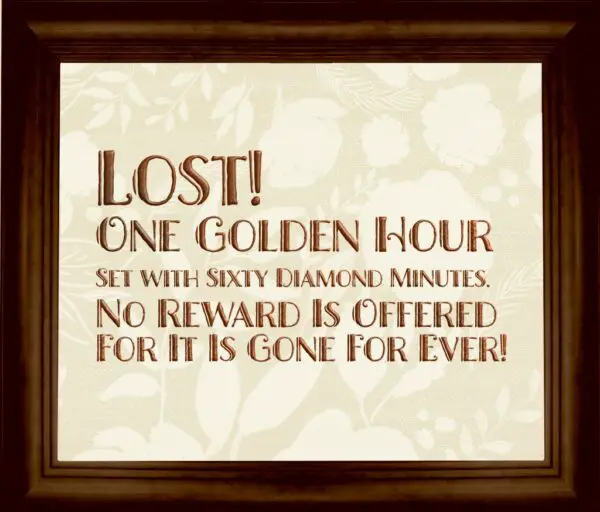

Above the bed a needlepoint hung in a black frame with the following text:

"Lost! One Golden Hour

Set with Sixty Diamond Minutes.

No Reward is Offered

For It Is GONE FOR EVER" (109).

Grandpa explains that Grandma had made it and then he smiled so merrily at Fenella she thought he might have winked at her.

Published on December 24, 1921 in Weekly Westminster Gazette , "The Voyage" is the only story within the Garden Party and Other Stories told from the point of view of a child. Although the exact age of Fenella Crane, the young protagonist, is not mentioned in the text, she is assumed to be older than five and younger than ten. Key word choices in the dialogue support this theory. Characters refer to Fenella as a “child,” “a motherless mite” and she is told to be a “good girl” by her father. She is old enough to realize the implications of being sent away to live with her grandparents but is still too young to travel alone by herself.

As a character Fenella is very observant and yet she reacts to her surroundings passively, as if she is overwhelmed by her circumstances but is incapable of expressing her true emotions. Note how she turns away from her father during his emotional goodbye to his mother. Fenella puts on a brave face for her father’s sake but her desperate clinging to his jacket’s lapels reveals her inner turmoil over being sent away from home. Mansfield portrays Fenella as an atypical child who hides her grief over the loss of her mother very well and takes only a moment to reflect on her feelings of abandonment as she watches her father fade into the distance as the boat pulls away from the harbor. The shilling Frank Crane gives his daughter suggests to Fenella that she will be gone for a long time. To the reader Frank’s shilling may imply that he is having financial difficulties and that is the reason he is sending her away. No other hint of an explanation is given in the text and Fenella’s placid reaction fails to capture the reader’s imagination. Unlike Mansfield’s other, stronger female characters in the overall collection, Fenella appears weak in comparison and suffers for want of a better narrative.

Mansfield often experimented with structure, narration, and especially with characterization. In “The Voyage ” she settles on capturing a moment in time without explaining why Fanella is leaving her father or how her mother died. As a modernist, Mansfield’s stories were often minimalist and lacked any character introductions or explanations of plot. She begins her stories in medias res and slowly reveals information as the story progresses; this tactic is especially evident in “The Voyage ” as the reader learns after Fenella and her Grandma are settled in their cabin on the boat that Fenella’s mother had died recently. This is revealed in dialogue between the Grandma and the stewardess while Fenella drifts off to sleep. Very stylistic and a true quality of the modernists, this revelation explains why Fenella is leaving but does little to develop her characterization. The only hint of character growth on Fenella’s part is her welcoming of the dawn and her hope that her life will change for the better now that she is leaving home.

Although the text does not specify Fenella’s departure point, Wellington, New Zealand is a possibility. Wellington is the author’s birthplace and a frequently used setting in her stories. Logistically it is also a boat ride away from Fenella’s destination, Picton, New Zealand, a small isolated coastal town and home of her grandparents. Although the setting fluctuates throughout the story, the primary setting is the boat that Fenella and her Grandma take on their journey and the ports they leave from and arrive in. Such temporary settings reflect the transition that Fenella is undertaking as she leaves childhood and enters young adulthood.

A coming of age story set on a very short voyage, Mansfield uses several instances of symbolism to reflect Fenella’s emotional growth. The sea, a reoccurring motif in The Garden Party and Other Stories, reflects Fenella’s mood. When she arrives on the boat the sea is dark, mysterious; Fenella does not know what to expect on her journey. Onboard, the sea is turbulent and tips the boat sideways while Fenella tries to sleep but by morning it is calm again, just as Fenella wakes and greets the new day, praying for her life to change. The passage of night into day is also significant. Mansfield begins the story at night to reflect Fenella’s grief and the dark nature of her circumstances. Later when she and her Grandma arrive in Picton, the dawn has arrived and with it a new life for Fenella. The most obvious symbol of Fenella’s emotional growth is; however, her Grandma’s swan-necked umbrella.

At the beginning of her journey Fenella carries the swan-necked umbrella in her traveling gear on her back. The swan beak pecks her in the back, urging her toward the boat and away from her former life. Fenella, obedient and docile, rushes forward and is reminded by her Grandma to look after the fragile umbrella. Perhaps Grandma gave Fenella the umbrella to distract the child on the journey, to give her something to think of other than the loss of her mother and more pressingly, life without her father. Regardless of her reasoning, Fenella takes the responsibility to heart and carefully conveys the umbrella onto the boat and into the cabin. That night, as the boat threatens to tip, Fenella thinks she should lay the umbrella down so it does not fall over and break during the night. Her Grandma, thinking along the same lines, asks the stewardess to lay the umbrella flat on the ground. This small scene reflects Fenella’s growing maturity and her use of logic. Later when she and her Grandma board the landing dock, Mansfield’s simple use of dialogue “You’ve got my-” and “Yes, grandma” (108) reflect the final stage of Fenella’s entry into young adulthood.

Now that she has taken ownership of the care of the umbrella, Fenella is in good spirits and hopeful for the future. It does seem a cruel trick of fate for Fenella to exchange her mother’s deathbed for her Grandpa’s sickbed but she seems unaffected by the association and happy to see her Grandpa, showing him the swan-necked umbrella with pride. Above his bed is a needlepoint of an abbreviated quote often attributed to the American educator and reformist, Horace Mann. The quote in its entirety reads:

“Lost- Yesterday, somewhere between sunrise and sunset, two golden hours, each set with sixty diamond minutes. No reward is offered, for they are gone forever.”

Mansfield’s use of the poem within the context of the story may be a reference to the passage of time and the importance of letting go of the past, specifically of Fenella’s life with her parents and the death of her mother. Grandpa points out the poem to Fenella while lying in bed and although it is not stated in the story, he appears to be either ill or bedridden. Note Mr. Penreddy’s remark to Grandma on the landing stage, that he had looked in on her husband and found him in good spirits. Grandpa, his white beard showing above the bed sheets, is the embodiment of old age whereas Fenella is in the first flush of young womanhood. At opposite ends of life’s spectrum, one beginning, the other ending, Fenella and her Grandpa share a moment of understanding. They recognize that the future is inevitable and the events of the past unchangeable. This is a difficult lesson at any age, but is especially so for a child.

The Garden Party Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for The Garden Party is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

What is the theme of death in the garden party?

A minor theme in comparison to life, death is the catalyst by which change occurs in a number of key stories within the overall work. Mr. Scott’s death in "The Garden Party" awakens in Laura Sheridan, the main character, a dislike of her family’s...

How death and It's acceptance as a theme has been incorporated in Mansfield's "The Garden Party"?

The death of Mr. Scott, only a passing acquaintance, shocks Laura into action. She feels it would be incredibly rude of her family to proceed with their garden party so soon after Mr. Scott’s death especially because he lived and died so close to...

How does the mood in the story change on p. 10 when Laura goes to the cottages down the hill? What type of concrete details does the author use to change the mood?

There is a rather sudden shift in mood as Laura enters the Cottages. There is a sort of apprehensive melancholy as dusk begins. There is a shadowy bog and the cottages began to be shaded in an oppressive way.

Study Guide for The Garden Party

The Garden Party study guide contains literature essays, a complete e-text, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About The Garden Party

- The Garden Party Summary

- Character List

Essays for The Garden Party

The Garden Party essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of The Garden Party by Katherine Mansfield.

- Marxism in Mansfield

- “The Daughters of the Late Colonel” as a Modernist Work

- Literary Devices in "Miss Brill"

- Discoveries That Broaden Understanding: Katherine Mansfield and Robert Gray

- Definitions of Place: Katherine Mansfield and Virginia Woolf

Lesson Plan for The Garden Party

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Common Core Standards

- Introduction to The Garden Party

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- The Garden Party Bibliography

E-Text of The Garden Party

The Garden Party e-text contains the full text of The Garden Party by Katherine Mansfield.

- 1. AT THE BAY.

- 2. THE GARDEN PARTY.

- 3. THE DAUGHTERS OF THE LATE COLONEL.

- 4. MR. AND MRS. DOVE.

- 5. THE YOUNG GIRL.

Wikipedia Entries for The Garden Party

- Introduction

- Characters in "The Garden Party"

- Major themes

- References to other works

SLAP HAPPY LARRY

The voyage by katherine mansfield short story analysis.

“The Voyage” is a short story by Katherine Mansfield, written 1921. Find it in The Garden Party collection.

Katherine Mansfield always disliked intellectualism and aestheticism (one thing she had in common with her husband John Middleton Murray). She strove to combine a realist way of writing with personal and relatable symbols.

“The Voyage” is a good example of her philosophy on that. This is one of Katherine Mansfield’s later stories and was published only after her death, in her 1923 collection The Garden Party . (She died in January of that year.)

Mansfield’s technique can be called impressionist , a term borrowed from art world. (“Impressionist” generally describes the way 19 th century painters depicted sensory impressions.) Mansfield mainly aimed to offer the reader a series of interconnected experiences. It’s often said there’s no ‘point’ to her stories other than that. It’s true that Mansfield’s stories were without didacticism (morals). We’re used to that now. It was unusual at the time.

It’s easy to forget how avant garde Mansfield was. You’ll have seen a lot of modernist, impressionist work since Mansfield’s time, and in fact, series of montages with none of the 19th century padding is now the storytelling norm. So I’d like to really emphasise that Mansfield’s impressionistic way of writing was a very new technique back in the 1920s. Katherine Mansfield was part of a movement, and made an important contribution to the development of the short story genre in particular.

Scholars are sometimes keen to point out that Mansfield’s short stories had ‘no plot’, either, comprising nothing but a series of quotidian snippets. Think of the montage technique in film and you’ve got the idea.

I disagree with the view that Mansfield’s short stories are without plot. Her stories are lyrical , but still adhere to conventional storytelling structure, which I’ll show you below.

What Happens In “The Voyage”

A girl of about five (Fenella) travels from Wellington with her grandmother by boat to her grandparents’ home in Picton, where she will live with the grandmother and grandfather. Her mother has passed away and her grandmother now takes care of her as her guardian. It is only halfway through the story when we discover Fenella’s mother is dead, hence the grandmother as new guardian. This information is revealed via imagery rather than via the narration, which emulates the way we learn things as children, before language and explanations even make much sense. It’s likely that Fenella has already been told in words exactly what’s happening, but she cannot really understand her new situation — or her mother’s death — until she feels it.

Setting of “The Voyage”

In the opening sentence we know where this story is set. Picton is a small town at the top of the South Island of New Zealand.

Is it time for Picton to have the conversation about changing its name? from The Spinoff. (The gateway to the South Island is named after a notorious slave trader who tortured a 13-year-old girl.)

If you want to travel between the North and South Islands, that’s where you catch the ferry, which takes you to the capital of Wellington, where Mansfield grew up. Historians and Mansfield’s contemporary readers would know the characters on the Picton side of the trip because of the landing stage:

‘And now the landing stage came out to meet them. Slowly it swam towards the Picton boat.’

Mansfield was very familiar with the Picton Boat. As a child she visited her Picton relatives many times with her family, and the Picton relatives came often to visit her.

It’s difficult to imagine now, just how dark it was before street lighting. The buildings ‘all seemed carved out of solid darkness’. The area around the Old Wharf is brought to life, with words like ‘quivering’, and the description of how it ‘burns softly, as if for itself’.

Why? Candles are used not only to light spaces but also as meditations. We have a tradition of lighting candles to remember dead loved ones. This is Fenella burning a candle for her early childhood life. We don’t know this yet — this is all foreshadowing.

This was an era when it was believed fathers were incapable of bringing up their own children. I’m sure a few did, but it was just as acceptable to give children to other female relatives if the children’s mother had died. The father walks in ‘quick, nervous’ strides. We’re not encouraged to take a good look into the father’s psychology, but it must have been terrible to lose a wife and then to lose your child, via nothing other than social circumstance.

A Brief History Of The Picton Boat

If you’d like a painterly view of the Ferry in Wellington in 1910, check out this painting by Sean Garwood, called “The Duchess” .

These days it’s common to take a flight between islands, but of course back in Mansfield’s era, the ferry was your only choice.

Now, a large proportion of the passengers will be travelling by ferry mainly for the tourist experience. The view of the mountains as you sail close to land is magnificent. And if you’re not sick to the stomach from choppy waters, it’s even more magnificent! The Cook Strait is a strip of water above a major network of fault lines — hence New Zealand is chopped in two in the first place!

The ‘Picton Boat’ known in my childhood as the ‘Picton Ferry’ is now called The Interislander, and the journey takes between 3-3/5 hours. But in the early 1900s, this boat trip between islands lasted an entire day. Back then, a trip between islands (a strip of water known as The Cook Strait) was more drama than a trip to Australia is today. Apart from the boat trip itself, you had to make it to the Old Wharf in Wellington, probably by horse and cart, and you couldn’t pay to just leave your horse there. You had to be dropped off. Today, travelling between islands is simple. To call it a ‘voyage’ would be hyperbole. But not for young Fenella, and not back then.

Other Setting Details

Without knowing anything else about the story, the reader can deduce the early 1900s setting of “The Voyage”:

- They use the old British style currency (shilling, tuppence). New Zealand switched to dollars and cents in 1967.

- Fenella’s grandmother wears restrictive clothing such as stays and bodice. Adults are wearing bonnets and caps in public. Even my mother, who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s, was required to wear a hat in public. Straw hats were part of her public school uniform. The social revolution of the late 1960s meant people no longer regarded it ‘improper’ to leave the house without wearing a hat. ‘To her surprise Fenella saw her father take off his hat.’

- The language used by the characters feels dated at times e.g. ‘what wickedness’.

- Bananas were a luxury product in this era. You couldn’t get them just anywhere, but Picton wharf was one place known for bananas. Unlike Australia, New Zealand’s climate has never been able to support its own banana growing industry. Even so, bananas are cheaply available now. They’re grown in the Phillipines and imported. New Zealand’s cheap bananas have huge ethical implications because the people who grow them are working under slave conditions . When I lived in London in 2006, I noticed Londoners had the option of buying ‘regular’ bananas or ‘fair trade’ bananas. There was never that option in New Zealand and I’d never given much thought to where bananas came from. Ethical bananas have since become an option for New Zealanders who still want to eat bananas.

- We know the grandmother doesn’t drink alcohol because the staff know her and therefore now it’s hopeless offering. Then she eats wine biscuits, and I realised that’s a word I haven’t heard in a very long time. I grew up in the 1980s with Griffins biscuits, and wine biscuits describe a sweet, plain biscuit with a complicated imprint of grapes on one side. I must have eaten thousands of those. Did they originally have something to do with wine? Probably, given the grapes. Griffins has rebranded them as ‘Superwine’ biscuits . I don’t know what the Picton Boat offerings looked like, and I can’t find a single image of a single Superwine biscuit on the entire Internet! In any case, Grandma was eating a plain, sweet biscuit, probably to settle her stomach.

- I’ve never booked a cabin on the Interislander. I have slept literally underneath the seats in the main area, on a midnight trip… after having missed my daytime one. According to one reviewer who booked a cabin in 2015: For $40 extra we had our own 4 bunk cabin on the Interislander. It had lovely white sheets, a window, our own shower and toilet. Two free cups of coffee and a newspaper thrown in! It was excellent and well worth the money.’ — Paula from Christchurch

For more on the historical era and the setting around the Old Wharf, see this post by Julie Kennedy .

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE VOYAGE”

Shortcoming.

When the child is a main character, their biggest shortcoming is their naivety and their reliance upon those around them.

Mansfield never lets readers know the exact age of Fenella, but we can guess she is a young child because of the limited understanding she has of different situations.

Mansfield writes this story in free, indirect discourse. Another story written with this narration is What Maisie Knew by Henry James , a description of a divorce but via the limited understanding of a girl about Fenella’s age.

When the audience knows something the character does not, this is a technique known as dramatic irony . Irony describes any sort of ‘meaningful gap’ in a story — in this case between audience and character.

Examples of dramatic irony:

- The woodpile is described as a “huge black mushroom”, an image that would perhaps be unusual from an adult’s point of view, but completely understandable from a child’s.

- In the middle of the story Fenella is in the private cabin with her grandmother. In wonder, Fenella sees the old woman undress. Until then she had hardly ever seen her grandmother with even her head uncovered. Because this is new and strange to Fenella. We know this is through the Fenella-filter because Fenella does not know the right words to describe women’s clothing: ‘Then she undid her bodice, and something under that, and something else under that.’ This is Fenella’s introduction to what it would be like to have a woman’s body.

- Fenella doesn’t know why Grandma thinks selling sandwiches for twopence is such ‘wickedness’. She doesn’t understand the value of money.

- Also, it is the first time Fenella makes this trip. We can also tell from the images — Fenella’s impressions — the narrator uses to describe the public area on the boat that everything is new to the girl: ‘They were in the saloon. It was glaring bright and stifling; the air smelled of paint and burnt chop-bones and india-rubber.’ An experienced traveler would no longer register this strangeness, but children — in common with adults on psychedelics — notice every new detail around them.

Fenella is a typical child, and small children tend to live in the moment. She’s not fully aware of the significance of this journey and she may not even know where they’re going. She doesn’t know how long she’ll be away from her father.

For this reason, her desires are very much in the moment.

- She wants to take care of her grandmother’s fetching umbrella.

- She wants to touch the sandwich, so she does. (She wants to eat it, too, but it’s too expensive.)

- She wants to take off her lace booties.

- She wants the soap to lather up, though it doesn’t.

Sometimes in a story populated by two people, they are each other’s opposition.

Definition of opponent: Any character who stands in the way of what the main character wants.

It’s irrelevant how kind the opponent is. In this story, grandmother is a caring, kind woman. The way in which she deals with Fenella belies her personality – she tells Fenella she would be more comfortable taking her lace socks off, though doesn’t insist that she do so. She reminds me a lot of my own grandmother.

Yet this loving grandmother is still Fenella’s opponent, because Fenella is a little anxious, and the grandmother is requiring her to do something she’d really prefer not to. The grandmother is taking her away from everything she knew and loved. To a child, who has not yet developed the meaning of permanence, a dead parent might come back at any stage.

The other opponent is that of nature — the inherent danger — or the sense of danger — which attends boat travel.

Grandma tells Fenella that ‘God is with you at sea more than he is on land’, betraying her nervousness, and the possibility of disaster.

The grandmother’s fears aren’t wholly imagined. The most notorious of New Zealand’s ferry disasters is the Wahine Disaster of 1968. My father was living and working in central Wellington at that time. He describes the wind as so strong that day that for a smaller individual it was impossible to stand upright outside. He remembers office workers on their hands and knees, trying to cross the street. 53 people lost their lives. The unbelievable part of it was, the ship was so very close to shore.

The Wahine was not New Zealand’s first maritime disaster. Shipwrecks were common in the 1800s, when this grandmother grew up, and as for this particular route:

On 12 February 1909 the Penguin struck a rock (Maybe Thoms Rock or the floating remains of a wreck) off the Wellington coast of Cook Strait and foundered with the loss of 75 lives. Katherine Mansfield left New Zealand in July 1908 so it is possible to speculate that if the Beauchamp family had been on the boat New Zealand might have lost its best known writer. She would certainly have been upset about this incident when she heard about it in England. Julie Kennedy

When Grandma and Fenella first go into the cabin, Fenella feels she has been ‘shut into a box’ with Grandma. The ‘box’ refers equally to a coffin. Mansfield probably thought of coffins whenever she entered small rooms — she uses that same imagery with the same reference in her story “ Miss Brill “ , who returns to her small bedsit after a visit to a public garden, in which she realises for the first time that she’s old. (I wonder if Mansfield suffered a little from claustrophobia.)

In any case, when Fenella thinks of grandma, she thinks of death. If they’re both in the coffin-like cabin together, they’re both adjacent to death, together. But then Mansfield juxtaposes this vision of grandma as one-foot-in-the-grave by making her climb nimbly up the ladder to the top bunk. Though this is a juxtaposed image of the elderly woman (who probably wasn’t all that old, given the era — she was probably in her forties, dammit), the story function is the same and therefore reinforces the idea that though Fenella is at one end of her life and grandma is at the other, they are both equal: they are both mortal. They will both die, and whenever that is? That doesn’t matter. It can happen at any time, as it happened to her mother.

If grandmother is an opponent, it’s because she is positioned as Fenella’s older version of herself. Fenella is therefore unable to get away from the concept of mortality.

Mansfield is drawing on a long history of the elder-care in this story, especially upon the history of old women. European fairytales are a good place to look for the contradictory feelings people have always held in regards to the sick, frail and elderly. On the one hand, old people have been given special status and privilege as founts of wisdom. By the same token, once a person becomes senile and can no longer contribute to family and society, they are pushed from this position of honour. In the medieval era, the elderly were oft-times executed or abandoned. Death is often considered a good thing, especially when compared to being old here on earth. When dies and joins her grandmother in Heaven, this is considered a happy ending.

THE LITTLE BOY

The little boy in “The Voyage” functions as more of a foil character than of outright opposition. His circumstances are the inverse of Fenella’s: Fenella’s grandmother is kind to her, but the little boy is jerked angrily along between two parents. Note that he has his parents, so is technically more lucky. But what if your parents are angry types?

The plan is made by the adults and Fenella has no choice but to go along with it. That’s the typical case for a naive child character.

BIG STRUGGLE

The ‘big struggle’ scene isn’t any sort of argument or fight but rather conveyed through an imagistic system of light and dark. (See below.)

ANAGNORISIS

Now’s a good time to talk about the imagery, which links directly to Fenella’s Anagnorisis .

LIGHT AND DARK IMAGERY

There are two themes symbolised by the contrast between darkness and light. First of all, complete the following chart using quotes and examples from the text.

This darkness/light imagery symbolizes:

1. TRANSITION FROM EARLY CHILDHOOD TO CHILDHOOD

There’s a point in our childhoods when we understand the concept of death. Until that moment, we believed everyone lives forever. The death of her mother forces Fenella to confront this fact earlier than she otherwise would have.

In a different story, “The Wind Blows” , Katherine Mansfield uses a ship in the distance to symbolise the later developmental phase — that of a teenager: The realisation that childhood comes to an end. This can feel like a kind of death (in hindsight more than at the time, I think).

2. LIFE AND DEATH

The sense of darkness may illustrate both Fenella’s uncertainty and her grief.

Symbolically, these images may indicate a difficult period in Fenella’s life is now behind her. Perhaps there have been years of her mother being ill, and now she has arrived in a new, stable home. (The mother might equally have died in childbirth.) However, it is implied that life will never regain the stability it seemed to have from a child’s point of view. Dealing with the death of a beloved one and becoming an adult also means getting a sense of the irrevocable passage of time. Fenella’s grandparents are obviously no longer young, and a final image, the text painted by her grandfather, underlines the awareness that life is transitory. Fortunately for Fenella, Grandpa looks very happy.

Fenella’s slight maturation over the course of a single night on the ferry is such a subtle ‘Anagnorisis’ that the reader is offered a second one, in the form of the grandmother’s painted message, affixed above the old grandfather’s head:

I wonder if this saying is a Katherine Mansfield original. It sounds like a poem that was commonly passed around, but I can’t say either way.

This story is about the inevitable passing of time — the hurtling towards death. When Katherine Mansfield wrote “The Voyage”, she had well and truly faced her own mortality. She would die just a few years later. The passing of time must have felt acute.

NEW SITUATION

The umbrella is important when making sense of the ending.

The umbrella is a repeated symbol throughout “The Voyage”, which technically makes it a motif . Fenella’s grandmother lets Fenella take care of her swan-necked, probably expensive umbrella. At first it seems a burden to Fenella as it is big and awkward (too big for her to manage — just like the notion of death). Fenella focuses on it during the trip, almost as a way of avoiding anxiety. At one point she prevents it from falling over at the same moment her grandmother does.

When they have arrived on the island, Grandma does not even have to say the word or Fenella can confirm she has performed her duty:

“You’ve got my—” ‘Yes, Grandma.’ Fenella showed it to her.”

The umbrella comes to symbolize Fenella’s new sense of responsibility, a process which has been accelerated because of the death of her mother. It surprises her grandfather that Fenella arrives carrying his wife’s precious novelty umbrella.

“Ugh!” said grandpa. “Her little nose is as cold as a button. What’s that she’s holding? Her grandma’s umbrella?”

We have learned, along with the grandfather, that little Fenella has grown up a little — enough to be trusted with a precious umbrella, and enough to cope with the tragic death of her mother. She’s going to be okay.

CONTEMPORARY FICTION SET IN AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND (2023)

On paper, things look fine. Sam Dennon recently inherited significant wealth from his uncle. As a respected architect, Sam spends his days thinking about the family needs and rich lives of his clients. But privately? Even his enduring love of amateur astronomy is on the wane. Sam has built a sustainable-architecture display home for himself but hasn’t yet moved into it, preferring to sleep in his cocoon of a campervan. Although they never announced it publicly, Sam’s wife and business partner ended their marriage years ago due to lack of intimacy, leaving Sam with the sense he is irreparably broken.

Now his beloved uncle has died. An intensifying fear manifests as health anxiety, with night terrors from a half-remembered early childhood event. To assuage the loneliness, Sam embarks on a Personal Happiness Project:

1. Get a pet dog

2. Find a friend. Just one. Not too intense.

KINDLE EBOOK

More from Katherine Mansfield

- A Man and His Dog

- A Married Man’s Story

- The Garden Party

More in Modernist Literature

- A Child’s Christmas in Wales

- The Snows of Kilimanjaro

- A Rose for Emily

- Hills Like White Elephants

- The Last Laugh

- Cross Country Snow

1901 Short Story

The Voyage is an English Modernist Literature short story by New Zealand writer Katherine Mansfield . It was first published in 1901.

The Voyage by Katherine Mansfield

The Picton boat was due to leave at half-past eleven. It was a beautiful night, mild, starry, only when they got out of the cab and started to walk down the Old Wharf that jutted out into the harbour, a faint wind blowing off the water ruffled under Fenella’s hat, and she put up her hand to keep it on. It was dark on the Old Wharf, very dark; the wool sheds, the cattle trucks, the cranes standing up so high, the little squat railway engine, all seemed carved out of solid darkness. Here and there on a rounded wood-pile, that was like the stalk of a huge black mushroom, there hung a lantern, but it seemed afraid to unfurl its timid, quivering light in all that blackness; it burned softly, as if for itself.

Fenella’s father pushed on with quick, nervous strides. Beside him her grandma bustled along in her crackling black ulster; they went so fast that she had now and again to give an undignified little skip to keep up with them. As well as her luggage strapped into a neat sausage, Fenella carried clasped to her her grandma’s umbrella, and the handle, which was a swan’s head, kept giving her shoulder a sharp little peck as if it too wanted her to hurry … Men, their caps pulled down, their collars turned up, swung by; a few women all muffled scurried along; and one tiny boy, only his little black arms and legs showing out of a white woolly shawl, was jerked along angrily between his father and mother; he looked like a baby fly that had fallen into the cream.

Then suddenly, so suddenly that Fenella and her grandma both leapt, there sounded from behind the largest wool shed, that had a trail of smoke hanging over it, “Mia-oo-oo-O-O!”

“First whistle,” said her father briefly, and at that moment they came in sight of the Picton boat. Lying beside the dark wharf, all strung, all beaded with round golden lights, the Picton boat looked as if she was more ready to sail among stars than out into the cold sea. People pressed along the gangway. First went her grandma, then her father, then Fenella. There was a high step down on to the deck, and an old sailor in a jersey standing by gave her his dry, hard hand. They were there; they stepped out of the way of the hurrying people, and standing under a little iron stairway that led to the upper deck they began to say good-bye.

“There, mother, there’s your luggage!” said Fenella’s father, giving grandma another strapped-up sausage.

“Thank you, Frank.”

“And you’ve got your cabin tickets safe?”

“Yes, dear.”

“And your other tickets?”

Grandma felt for them inside her glove and showed him the tips.

“That’s right.”

He sounded stern, but Fenella, eagerly watching him, saw that he looked tired and sad. “Mia-oo-oo-O-O!” The second whistle blared just above their heads, and a voice like a cry shouted, “Any more for the gangway?”

“You’ll give my love to father,” Fenella saw her father’s lips say. And her grandma, very agitated, answered, “Of course I will, dear. Go now. You’ll be left. Go now, Frank. Go now.”

“It’s all right, mother. I’ve got another three minutes.” To her surprise Fenella saw her father take off his hat. He clasped grandma in his arms and pressed her to him. “God bless you, mother!” she heard him say.

And grandma put her hand, with the black thread glove that was worn through on her ring finger, against his cheek, and she sobbed, “God bless you, my own brave son!”

This was so awful that Fenella quickly turned her back on them, swallowed once, twice, and frowned terribly at a little green star on a mast head. But she had to turn round again; her father was going.

“Good-bye, Fenella. Be a good girl.” His cold, wet moustache brushed her cheek. But Fenella caught hold of the lapels of his coat.

“How long am I going to stay?” she whispered anxiously. He wouldn’t look at her. He shook her off gently, and gently said, “We’ll see about that. Here! Where’s your hand?” He pressed something into her palm. “Here’s a shilling in case you should need it.”

A shilling! She must be going away for ever! “Father!” cried Fenella. But he was gone. He was the last off the ship. The sailors put their shoulders to the gangway. A huge coil of dark rope went flying through the air and fell “thump” on the wharf. A bell rang; a whistle shrilled. Silently the dark wharf began to slip, to slide, to edge away from them. Now there was a rush of water between. Fenella strained to see with all her might. “Was that father turning round?” – or waving? – or standing alone? – or walking off by himself? The strip of water grew broader, darker. Now the Picton boat began to swing round steady, pointing out to sea. It was no good looking any longer. There was nothing to be seen but a few lights, the face of the town clock hanging in the air, and more lights, little patches of them, on the dark hills.

The freshening wind tugged at Fenella’s skirts; she went back to her grandma. To her relief grandma seemed no longer sad. She had put the two sausages of luggage one on top of the other, and she was sitting on them, her hands folded, her head a little on one side. There was an intent, bright look on her face. Then Fenella saw that her lips were moving and guessed that she was praying. But the old woman gave her a bright nod as if to say the prayer was nearly over. She unclasped her hands, sighed, clasped them again, bent forward, and at last gave herself a soft shake.

“And now, child,” she said, fingering the bow of her bonnet-strings, “I think we ought to see about our cabins. Keep close to me, and mind you don’t slip.”

“Yes, grandma!”

“And be careful the umbrellas aren’t caught in the stair rail. I saw a beautiful umbrella broken in half like that on my way over.”

“Yes, grandma.”

Dark figures of men lounged against the rails. In the glow of their pipes a nose shone out, or the peak of a cap, or a pair of surprised-looking eyebrows. Fenella glanced up. High in the air, a little figure, his hands thrust in his short jacket pockets, stood staring out to sea. The ship rocked ever so little, and she thought the stars rocked too. And now a pale steward in a linen coat, holding a tray high in the palm of his hand, stepped out of a lighted doorway and skimmed past them. They went through that doorway. Carefully over the high brass-bound step on to the rubber mat and then down such a terribly steep flight of stairs that grandma had to put both feet on each step, and Fenella clutched the clammy brass rail and forgot all about the swan-necked umbrella.

At the bottom grandma stopped; Fenella was rather afraid she was going to pray again. But no, it was only to get out the cabin tickets. They were in the saloon. It was glaring bright and stifling; the air smelled of paint and burnt chop-bones and indiarubber. Fenella wished her grandma would go on, but the old woman was not to be hurried. An immense basket of ham sandwiches caught her eye. She went up to them and touched the top one delicately with her finger.

“How much are the sandwiches?” she asked.

“Tuppence!” bawled a rude steward, slamming down a knife and fork.

Grandma could hardly believe it.

“Twopence each?” she asked.

“That’s right,” said the steward, and he winked at his companion.

Grandma made a small, astonished face. Then she whispered primly to Fenella. “What wickedness!” And they sailed out at the further door and along a passage that had cabins on either side. Such a very nice stewardess came to meet them. She was dressed all in blue, and her collar and cuffs were fastened with large brass buttons. She seemed to know grandma well.

“Well, Mrs. Crane,” said she, unlocking their washstand. “We’ve got you back again. It’s not often you give yourself a cabin.”

“No,” said grandma. “But this time my dear son’s thoughtfulness–“

“I hope–” began the stewardess. Then she turned round and took a long, mournful look at grandma’s blackness and at Fenella’s black coat and skirt, black blouse, and hat with a crape rose.

Grandma nodded. “It was God’s will,” said she.

The stewardess shut her lips and, taking a deep breath, she seemed to expand.

“What I always say is,” she said, as though it was her own discovery, “sooner or later each of us has to go, and that’s a certingty.” She paused. “Now, can I bring you anything, Mrs Crane? A cup of tea? I know it’s no good offering you a little something to keep the cold out.”

Grandma shook her head. “Nothing, thank you. We’ve got a few wine biscuits, and Fenella has a very nice banana.”

“Then I’ll give you a look later on,” said the stewardess, and she went out, shutting the door.

What a very small cabin it was! It was like being shut up in a box with grandma. The dark round eye above the washstand gleamed at them dully. Fenella felt shy. She stood against the door, still clasping her luggage and the umbrella. Were they going to get undressed in here? Already her grandma had taken off her bonnet, and, rolling up the strings, she fixed each with a pin to the lining before she hung the bonnet up. Her white hair shone like silk; the little bun at the back was covered with a black net. Fenella hardly ever saw her grandma with her head uncovered; she looked strange.

“I shall put on the woollen fascinator your dear mother crocheted for me,” said grandma, and, unstrapping the sausage, she took it out and wound it round her head; the fringe of grey bobbles danced at her eyebrows as she smiled tenderly and mournfully at Fenella. Then she undid her bodice, and something under that, and something else underneath that. Then there seemed a short, sharp tussle, and grandma flushed faintly. Snip! Snap! She had undone her stays. She breathed a sigh of relief, and sitting on the plush couch, she slowly and carefully pulled off her elastic-sided boots and stood them side by side.

By the time Fenella had taken off her coat and skirt and put on her flannel dressing-gown grandma was quite ready.

“Must I take off my boots, grandma? They’re lace.”

Grandma gave them a moment’s deep consideration. “You’d feel a great deal more comfortable if you did, child,” said she. She kissed Fenella. “Don’t forget to say your prayers. Our dear Lord is with us when we are at sea even more than when we are on dry land. And because I am an experienced traveller,” said grandma briskly, “I shall take the upper berth.”

“But, grandma, however will you get up there?”

Three little spider-like steps were all Fenella saw. The old woman gave a small silent laugh before she mounted them nimbly, and she peered over the high bunk at the astonished Fenella.

“You didn’t think your grandma could do that, did you?” said she. And as she sank back Fenella heard her light laugh again.

The hard square of brown soap would not lather, and the water in the bottle was like a kind of blue jelly. How hard it was, too, to turn down those stiff sheets; you simply had to tear your way in. If everything had been different, Fenella might have got the giggles … At last she was inside, and while she lay there panting, there sounded from above a long, soft whispering, as though some one was gently, gently rustling among tissue paper to find something. It was grandma saying her prayers …

A long time passed. Then the stewardess came in; she trod softly and leaned her hand on grandma’s bunk.

“We’re just entering the Straits,” she said.

“Oh!”

“It’s a fine night, but we’re rather empty. We may pitch a little.”

And indeed at that moment the Picton Boat rose and rose and hung in the air just long enough to give a shiver before she swung down again, and there was the sound of heavy water slapping against her sides. Fenella remembered she had left the swan-necked umbrella standing up on the little couch. If it fell over, would it break? But grandma remembered too, at the same time.

“I wonder if you’d mind, stewardess, laying down my umbrella,” she whispered.

“Not at all, Mrs. Crane.” And the stewardess, coming back to grandma, breathed, “Your little granddaughter’s in such a beautiful sleep.”

“God be praised for that!” said grandma.

“Poor little motherless mite!” said the stewardess. And grandma was still telling the stewardess all about what happened when Fenella fell asleep.

But she hadn’t been asleep long enough to dream before she woke up again to see something waving in the air above her head. What was it? What could it be? It was a small grey foot. Now another joined it. They seemed to be feeling about for something; there came a sigh.

“I’m awake, grandma,” said Fenella.

“Oh, dear, am I near the ladder?” asked grandma. “I thought it was this end.”

“No, grandma, it’s the other. I’ll put your foot on it. Are we there?” asked Fenella.

“In the harbour,” said grandma. “We must get up, child. You’d better have a biscuit to steady yourself before you move.”

But Fenella had hopped out of her bunk. The lamp was still burning, but night was over, and it was cold. Peering through that round eye she could see far off some rocks. Now they were scattered over with foam; now a gull flipped by; and now there came a long piece of real land.

“It’s land, grandma,” said Fenella, wonderingly, as though they had been at sea for weeks together. She hugged herself; she stood on one leg and rubbed it with the toes of the other foot; she was trembling. Oh, it had all been so sad lately. Was it going to change? But all her grandma said was, “Make haste, child. I should leave your nice banana for the stewardess as you haven’t eaten it.” And Fenella put on her black clothes again and a button sprang off one of her gloves and rolled to where she couldn’t reach it. They went up on deck.

But if it had been cold in the cabin, on deck it was like ice. The sun was not up yet, but the stars were dim, and the cold pale sky was the same colour as the cold pale sea. On the land a white mist rose and fell. Now they could see quite plainly dark bush. Even the shapes of the umbrella ferns showed, and those strange silvery withered trees that are like skeletons … Now they could see the landing-stage and some little houses, pale too, clustered together, like shells on the lid of a box. The other passengers tramped up and down, but more slowly than they had the night before, and they looked gloomy.

And now the landing-stage came out to meet them. Slowly it swam towards the Picton boat, and a man holding a coil of rope, and a cart with a small drooping horse and another man sitting on the step, came too.

“It’s Mr. Penreddy, Fenella, come for us,” said grandma. She sounded pleased. Her white waxen cheeks were blue with cold, her chin trembled, and she had to keep wiping her eyes and her little pink nose.

“You’ve got my–“

“Yes, grandma.” Fenella showed it to her.

The rope came flying through the air, and “smack” it fell on to the deck. The gangway was lowered. Again Fenella followed her grandma on to the wharf over to the little cart, and a moment later they were bowling away. The hooves of the little horse drummed over the wooden piles, then sank softly into the sandy road. Not a soul was to be seen; there was not even a feather of smoke. The mist rose and fell and the sea still sounded asleep as slowly it turned on the beach.

“I seen Mr. Crane yestiddy,” said Mr. Penreddy. “He looked himself then. Missus knocked him up a batch of scones last week.”

And now the little horse pulled up before one of the shell-like houses. They got down. Fenella put her hand on the gate, and the big, trembling dew-drops soaked through her glove-tips. Up a little path of round white pebbles they went, with drenched sleeping flowers on either side. Grandma’s delicate white picotees were so heavy with dew that they were fallen, but their sweet smell was part of the cold morning. The blinds were down in the little house; they mounted the steps on to the veranda. A pair of old bluchers was on one side of the door, and a large red watering-can on the other.

“Tut! tut! Your grandpa,” said grandma. She turned the handle. Not a sound. She called, “Walter!” And immediately a deep voice that sounded half stifled called back, “Is that you, Mary?”

“Wait, dear,” said grandma. “Go in there.” She pushed Fenella gently into a small dusky sitting-room.

On the table a white cat, that had been folded up like a camel, rose, stretched itself, yawned, and then sprang on to the tips of its toes. Fenella buried one cold little hand in the white, warm fur, and smiled timidly while she stroked and listened to grandma’s gentle voice and the rolling tones of grandpa.

A door creaked. “Come in, dear.” The old woman beckoned, Fenella followed. There, lying to one side on an immense bed, lay grandpa. Just his head with a white tuft and his rosy face and long silver beard showed over the quilt. He was like a very old wide-awake bird.

“Well, my girl!” said grandpa. “Give us a kiss!” Fenella kissed him. “Ugh!” said grandpa. “Her little nose is as cold as a button. What’s that she’s holding? Her grandma’s umbrella?”

Fenella smiled again, and crooked the swan neck over the bed-rail. Above the bed there was a big text in a deep black frame:-

“Lost! One Golden Hour Set with Sixty Diamond Minutes. No Reward Is Offered For It Is Gone For Ever!”

“Yer grandma painted that,” said grandpa. And he ruffled his white tuft and looked at Fenella so merrily she almost thought he winked at her.

Katherine Mansfield

Katherine Mansfield (1888–1923) was a New Zealand-born modernist short-story writer known for her innovative narrative techniques and vivid characterizations. Her stories, including “The Garden Party” and “Bliss,” are celebrated for their psychological depth and exploration of the human condition. Mansfield’s impact on short fiction is profound.

Read More in

Read more in modernist literature.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- study guides

- lesson plans

- homework help

The Voyage - Pages 1 – 3 Summary & Analysis

On a pleasant night in Wellington, New Zealand, Fenella Crane is being ushered toward a boat bound for Picton by her father Frank and her grandmother Mary. The stars are out in the sky, and the boat is scheduled to leave at 11:30 PM. Fenella notices how dark the night is, apart from a single lantern hanging near the Old Wharf, "but it seemed afraid to unfurl its timid, quivering light in all that blackness; it burned softly, as if for itself" (1). As they hurry toward the boat, Fenella holds her grandmother's umbrella. The handle hits her shoulder repeatedly "as if it too wanted her to hurry" (1). Fenella notices another young boy being jerked back and forth between his parents as everyone scurries to make it to the boat on time.

The first whistle blows, and Fenella and her family make their way onto the...

(read more from the Pages 1 – 3 Summary)

FOLLOW BOOKRAGS:

The Sitting Bee

Short Story Reviews

The Voyage by Katherine Mansfield

In The Voyage by Katherine Mansfield we have the theme of innocence, responsibility, change and moving on. Taken from her The Garden Party and Other Stories collection the story is narrated in the third person by an unnamed narrator and it would appear that the narrator’s point of view, mirrors that of the main protagonist in the story, Fenella. What is also noticeable early on in the story is that Mansfield appears to be exploring the theme of innocence. As the boat is pulling away from the wharf, Mansfield tells the reader that ‘silently the dark wharf began to slip, to slide, to edge away from them (Fenella and her grandmother).’ This line is significant as it suggests that Fenella believes that it is the wharf that is moving, rather than the boat. This in turn may suggest that Fenella is innocent. Also by describing Mrs Crane as looking ‘astonished’ (in Fenella’s eyes), when Mrs Crane discovers the sandwiches on the boat are two pence each, it is possible that Mansfield is suggesting that Fenella, does not understand that her grandmother considers the sandwiches to be expensive which again may suggest Fenella is innocent of the world around her.

It is also noticeable that while Mrs Crane is in the cabin, stripping and getting ready for bed, Fenella is unable to describe her grandmother’s clothing. Mansfield telling the reader that Mrs Crane ‘undid her bodice, and something under that, and something else underneath that.’ This lack of knowledge when it comes to her grandmother’s clothing is significant as it further suggests the idea of innocence. Fenella is too young to know the name of each garment that her grandmother is wearing. Symbolically Mrs Crane’s name may also be important. A crane is usually used to pick things up and move them. It is possible that Mansfield by giving Fenella’s grandmother the name Crane is also suggesting (and it also appears to be the case) that Mrs Crane is picking Fenella up (from her father’s home in Wellington) and moving her (to Picton).

Mansfield also appears to be using Mrs Crane’s umbrella as a symbol for responsibility. Throughout the story it is Fenella’s responsibility to look after the umbrella. At the start she appears to have difficulty looking after the umbrella (and may even be afraid of the umbrella) but as the story progresses and particularly at the end, it becomes clear to the reader that Fenella has been successful in her task of looking after the umbrella, without having to be reminded continuously by her grandmother. Something that is noticeable when the boat docks at Picton and before Mrs Crane can finish her sentence, Fenella tells her grandmother that she does have the umbrella. It is possible that Mansfield, through using the umbrella as symbolism, is suggesting that now that Fenella’s mother has passed away, Fenella needs to learn (or become) more responsible. No longer does she have her mother to look after her.

It is also possible that Mansfield is using colour and the setting of the story as symbols for change. At the beginning of the story, particularly at the wharf, Mansfield describes the setting as being ‘very dark: the wool sheds, the cattle trucks, the cranes standing up so high, the little squat railway engine, all seemed carved out of solid darkness.’ In many ways this setting mirrors how Fenella, her father and her grandmother may feel (now that Fenella’s mother is dead). Mansfield continues to use dark imagery when Mrs Crane and Fenella are aboard the boat and talking to the stewardess – ‘she (stewardess) turned around and took a long mournful look at grandma’s blackness and at Fenella’s dark coat and skirt, black blouse, and hat with a crepe rose.’

However it is noticeable that Mansfield, when Fenella and Mrs Crane are in the cabin, begins to use brighter colours, Fenella notices ‘the hard square of brown soap’ and ‘the water in the bottle was like a blue kind of jelly.’ Also when Fenella wakes up and is standing on the deck of the boat, Mansfield tells the reader that ‘the cold pale sky was the same colour as the cold pale sea.’ This shift from dark to brighter continues when the boat docks in Picton, the reader discovering that when Mrs Crane sees Mr Penreddy ‘her white waxen cheeks were blue with cold, her chin trembled, and she had to keep wiping her eyes and her little pink nose.’ By associating Fenella and Mrs Crane’s arrival in Picton with brighter imagery (something that is also noticeable when Fenella is stroking the white cat at her grandfather’s home), Mansfield may be suggesting that life will change (and improve) for Fenella. No longer will her life (or her grandmother’s) be as dark or as mournful as the setting on the wharf. If anything Fenella’s life is to begin again.

The verse (by Horace Mann) introduced at the end of the story may also be important. It is possible that Mansfield, by introducing this verse, is suggesting that what has happened in the past (Fenella’s mother’s death) cannot be changed (and is lost forever) and that an individual (Fenella) should look forward to the future and move on from the past. Something that may be possible for Fenella now that she is to begin a new life living with her grandparents. It is also interesting that Mansfield tells the reader (again at the end of the story) that Fenella’s grandfather looked at her ‘so merrily she almost thought he winked at her.’ This line may be significant as by ending the story with a hint of affection, Mansfield may be suggesting that Fenella, despite losing her mother, will be loved by her grandfather (and grandmother).

- All Serene by Katherine Mansfield

- A Cup of Tea by Katherine Mansfield

- The Fly by Katherine Mansfield

- Revelations by Katherine Mansfield

- Katherine Mansfield

It is an awesome story….

Thanks for the comment Ashwini. It is a great story.

The psychological separation from her parents is emotionally expressed during this voyage with her grandma

Thanks Youssef.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments via e-mail

Currently you have JavaScript disabled. In order to post comments, please make sure JavaScript and Cookies are enabled, and reload the page. Click here for instructions on how to enable JavaScript in your browser.

This is an archived copy of the KMS website from April 2021. To view the current website, click here .

- Join the KMS

- Notable Members

- KM Sculpture

- Bad Worishofen 2021

- Birthday Lecture 2020

- Menton 2020

- Birthday Lecture 2019

- Krakow 2019

- Birthday Lecture 2018

- London 2018

- Postgraduate Day 2018

- Bandol 2018

- Birthday Lecture 2017

- Huntington, USA 2017

- Fontainebleau-Avon June 2017

- Postgraduate Day 2017

- Birthday Lecture 2016

- Avon Birthday Lecture 2016

- Bandol Conference 2016

- Messines Symposium 2015

- Birthday Lecture 2015

- Sierre 2015

- Chicago Conference 2015

- KM in Gray 20-22 February 2015

- UNSW, Sydney, 2015

- Birthday Lecture 2014

- Festival at Avon

- Postgraduate Day 2013

- Wellington 125th Anniversary Weekend 2013

- Birthday Lecture 2013

- Wellington 2013

- Birthday Lecture 2012

- Crans-Montana 2012

- Slovakia 2012

- Birthday Lecture 2011

- Cambridge 2011

- Birthday Lecture 2010

- RMIT Melbourne 2010

- Menton 2009

Essay Prize

- Previous Essay Competitions

- Style Guide

Publications

- Heron: Creative Journal of the Katherine Mansfield Society

- Tinakori: Critical Journal of the Katherine Mansfield Society

- Audio / Visual

- Bibliography

- Poems Around KM

- Plays about Mansfield

- UK Census 1911

- Artistic Representations

- KM Image Collections

- KM Today Blog

- Short Stories by KM

- Poems by KM

- KM Chronology

- KM and China Database

- Story Translations

A large selection of freely available Mansfield resources can be found at the New Zealand Electronic Text Centre | www.nzetc.org In particular, there are the following texts:

- Something Childish and Other Stories

- The Garden Party and Other Stories

- The Life of Katherine Mansfield

- Recollecting Mansfield

- In a German Pension

- The Letters of Katherine Mansfield vol 1

The stories below were prepared by Gerri Kimber, Paul Capewell and especially Robert Corrington, to whom the KMS extends its grateful thanks.

Pre 1910

Silhouettes (1907)

A Happy Christmas Eve

Die Einsame (The Lonely One)

The Education of Audrey

The Tiredness of Rosabell (1908)

The Child-Who-Was-Tired

Germans at Meat

The Luftbad

At 'Lehmann's'

Frau Brechenmacher Attends a Wedding

The Sister of the Baroness

Frau Fischer

The Modern Soul

The Advanced Lady

The Swing of the Pendulum

The Journey to Bruges

Being a Truthful Adventure

The Festival of the Coronation (with Apologies to Theocritus)

Two Parodies: Arnold Bennett and H. G. Wells

Green Goggles

The Woman at the Store

How Pearl Button was kidnapped

The Little Girl

New Dresses

Old Cockatoo Curl

Ole Underwood

Epilogue I: Pension Seguin

Epilogue II: Violet

Epilogue III: Bains Turc

Something Childish But Very Natural

The Little Governess

Spring Pictures

An Indiscreet Journey

The Wind Blows

The Lost Battle ( fragment of Geneva )

Two Tuppenny Ones Please

Late at Night

The Black Cap

In Confidence

Mr Reginald Peacock's Day

Feuille d'Album

A Dill Pickle

Je ne parle pas Francias

Sun and Moon

A Suburban Fairy Tale

This Flower

The Man Without a Temperament

The Wrong House

Revelations

Bank Holiday

The Young Girl

The Singing Lesson

The Stranger

The Lady's Maid

The Daughters of the Late Colonel

Life of Ma Parker

Mr and mrs Dove

An Ideal Family

Her First Ball

Marriage a la Mode

A Married Man's Story

The Garden Party

The Doll's House

Six Years After

The Doves' Nest

A Cup of Tea

Taking The Veil

A Man and His Dog

Father and the Girls

Mr and Mrs Williams

Second Violin

Such a Sweet Old Lady

Taking the Veil

"A certain melancholy has been brooding over me this fortnight. I date it from Katherine's death. The feeling comes to me so often now – Yes. Go on writing of course: but into emptiness. There's no competitor."

Virginia Woolf

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Voyage" is a 1921 short story by Katherine Mansfield. ... Plot summary. At the harbour Fenella and her grandmother say goodbye to Fenella's father and board the Picton boat; a number of everyday situations are described during the journey, which highlight a degree of tension between the rather religious grandmother and staff on the boat. At ...

The Garden Party Summary and Analysis of "The Voyage". Summary. Fenella hurried toward the Picton boat with her father and Grandma. The night was mild, the sky starry but Fenella took little joy in it, sensing her Father's unease. Her Grandma's fancy umbrella with the swan head handle was tucked into the luggage Fenella had strapped to her ...

"The Voyage" is a short story by Katherine Mansfield, written 1921. Find it in The Garden Party collection. Katherine Mansfield always disliked intellectualism and aestheticism (one thing she had in common with her husband John Middleton Murray). She strove to combine a realist way of writing with personal and relatable symbols. "The Voyage" is a […]

Katherine Mansfield's "The Voyage" was first published in 1922 as part of a collection of short works of fiction entitled The Garden Party and Other Stories.Mansfield, herself, was a master of the ...

Summary. Last Updated September 5, 2023. Katherine Mansfield's "The Voyage" takes place in New Zealand—in Wellington and Picton—near the turn of the twentieth century. The protagonist is ...

The Voyage Summary & Study Guide includes comprehensive information and analysis to help you understand the book. This study guide contains the following sections: This detailed literature summary also contains Quotes and a Free Quiz on The Voyage by Katherine Mansfield. The following version of this story was used to create this guide ...

Katherine Mansfield (1888-1923) was a New Zealand-born modernist short-story writer known for her innovative narrative techniques and vivid characterizations. Her stories, including "The Garden Party" and "Bliss," are celebrated for their psychological depth and exploration of the human condition.

Discussion of themes and motifs in Katherine Mansfield's The Voyage. eNotes critical analyses help you gain a deeper understanding of The Voyage so you can excel on your essay or test.

The Voyage. The Picton boat was due to leave at half-past eleven. It was a beautiful night, mild, starry, only when they got out of the cab and started to walk down the Old Wharf that jutted out into the harbour, a faint wind blowing off the water ruffled under Fenella's hat, and she put up her hand to keep it on.

The Voyage Overview. "The Voyage" is a short story by English writer Katherine Mansfield. It was originally published in The Sphere in 1921, and it later appeared in the collection The Garden Party and Other Stories, published in 1922. "The Voyage" tells the story of a young girl named Fenella Crane, who travels with her grandmother on a boat ...

The Voyage - Pages 1 - 3 Summary & Analysis Katherine Mansfield This Study Guide consists of approximately 16 pages of chapter summaries, quotes, character analysis, themes, and more - everything you need to sharpen your knowledge of The Voyage.

THE VOYAGE (1921) By Katherine Mansfield -past eleven. It was a beautiful night, mild, starry, ffled under Fenella's hat, and she there on a rounded wood-pile, that was like the ck, nervous strides. Beside him her grandma bustled ied clasped to her her grandma's umbrella, and the handle, la and her grandma both leapt, there sounded from

Subscribe to our channel for more videos🔔"The Voyage" is a short story by Katherine Mansfield. Set probably in Wellington, New Zealand as Picton is a tiny c...

In The Voyage by Katherine Mansfield we have the theme of innocence, responsibility, change and moving on. Taken from her The Garden Party and Other Stories collection the story is narrated in the third person by an unnamed narrator and it would appear that the narrator's point of view, mirrors that of the main protagonist in the story, Fenella.

Frank is the father of Fenella and the son of Mary and Walter. He appears only at the beginning of the story, when he accompanies Fenella and Mary to the Wellington dock. He appears to have a ...

SUMMARY. Katherine Mansfield's "The Voyage" takes place in New Zealand—in Wellington and Picton —near the turn of the twentieth century. The protagonist is a young girl named Fenella Crane, whose mother has recently died. At the beginning of the story, Fenella's father, Frank, accompanies her and her grandmother, Mary, to the wharf ...

Other articles where The Voyage is discussed: Katherine Mansfield: …includes "At the Bay," "The Voyage," "The Stranger" (with New Zealand settings), and the classic "Daughters of the Late Colonel," a subtle account of genteel frustration. The last five years of her life were shadowed by tuberculosis. Her final work (apart from unfinished material) was published posthumously ...

the voyage by katherine mansfield summarythe voyage by katherine mansfield summarythe voyage by katherine mansfield summary the voyage by katherine mansfield...

Summary for The Garden Party: Katherine Mansfield revolutionized the short story genre by ending the predominant reliance upon traditional plot structure, instead relying more on a specific moment in time, expressed through image patterns. By doing this, Mansfield carried the short story genre away from formalistic structuring and helped to establish its credibility as a literary form.

Take a quick interactive quiz on the concepts in The Voyage by Katherine Mansfield | Summary, Symbolism & Analysis or print the worksheet to practice offline. These practice questions will help ...

Katherine Mansfield. Fenella Crane struggles to keep up with her father and grandmother as they stride toward the Picton boat. Her neatly-rolled luggage is strapped to her back and she clutches her grandmother's umbrella closely to her. Her father looks tired and sad, she thinks, and as the second whistle blows, he removes his hat and takes ...

Katherine Mansfield (born October 14, 1888, Wellington, New Zealand—died January 9, 1923, Gurdjieff Institute, near Fontainebleau, France) was a New Zealand-born English master of the short story, who evolved a distinctive prose style with many overtones of poetry. Her delicate stories, focused upon psychological conflicts, have an ...

The Voyage . A Married Man's Story. The Garden Party . The Doll's House. Six Years After. Weak Heart. The Doves' Nest. 1922. A Cup of Tea. Taking The Veil. The Fly. Honeymoon. The Canary. 1923. A Bad Idea. All Serene. ... The Katherine Mansfield Society - CC46669 is a ...