- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Patient Perspectives

- Methods Corner

- ESC Content Collections

- Author Guidelines

- Instructions for reviewers

- Submission Site

- Why publish with EJCN?

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Read & Publish

- About European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing

- About ACNAP

- About European Society of Cardiology

- ESC Publications

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- War in Ukraine

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, why patient journey mapping, how is patient journey mapping conducted, use of technology in patient journey mapping, future implications for patient journey mapping, conclusions, patient journey mapping: emerging methods for understanding and improving patient experiences of health systems and services.

Lemma N Bulto and Ellen Davies Shared first authorship.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Lemma N Bulto, Ellen Davies, Janet Kelly, Jeroen M Hendriks, Patient journey mapping: emerging methods for understanding and improving patient experiences of health systems and services, European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing , 2024;, zvae012, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvae012

- Permissions Icon Permissions

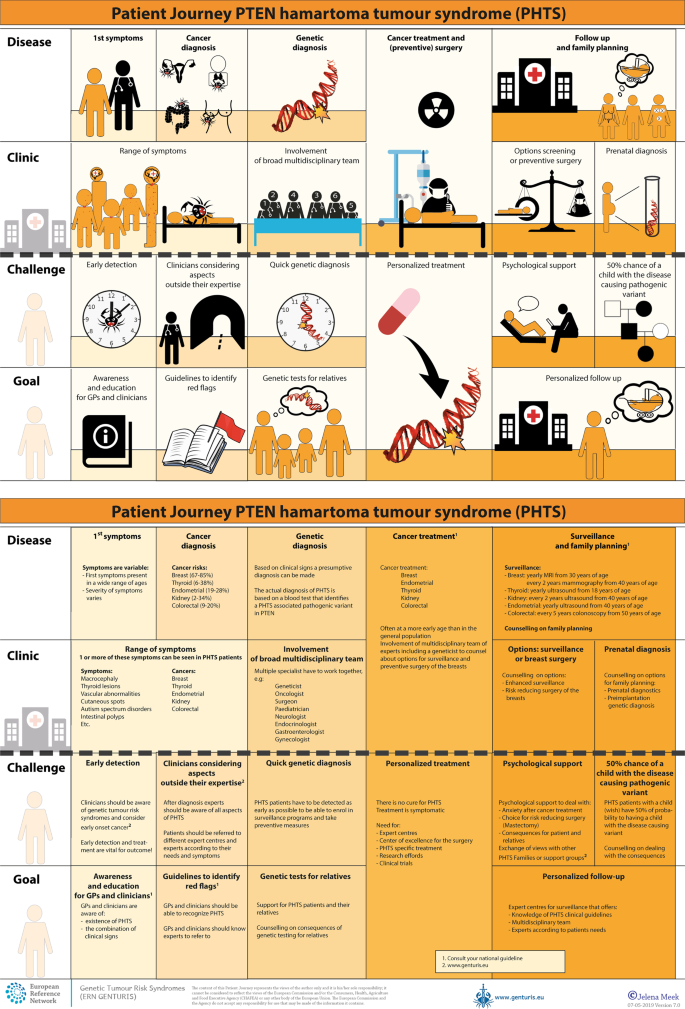

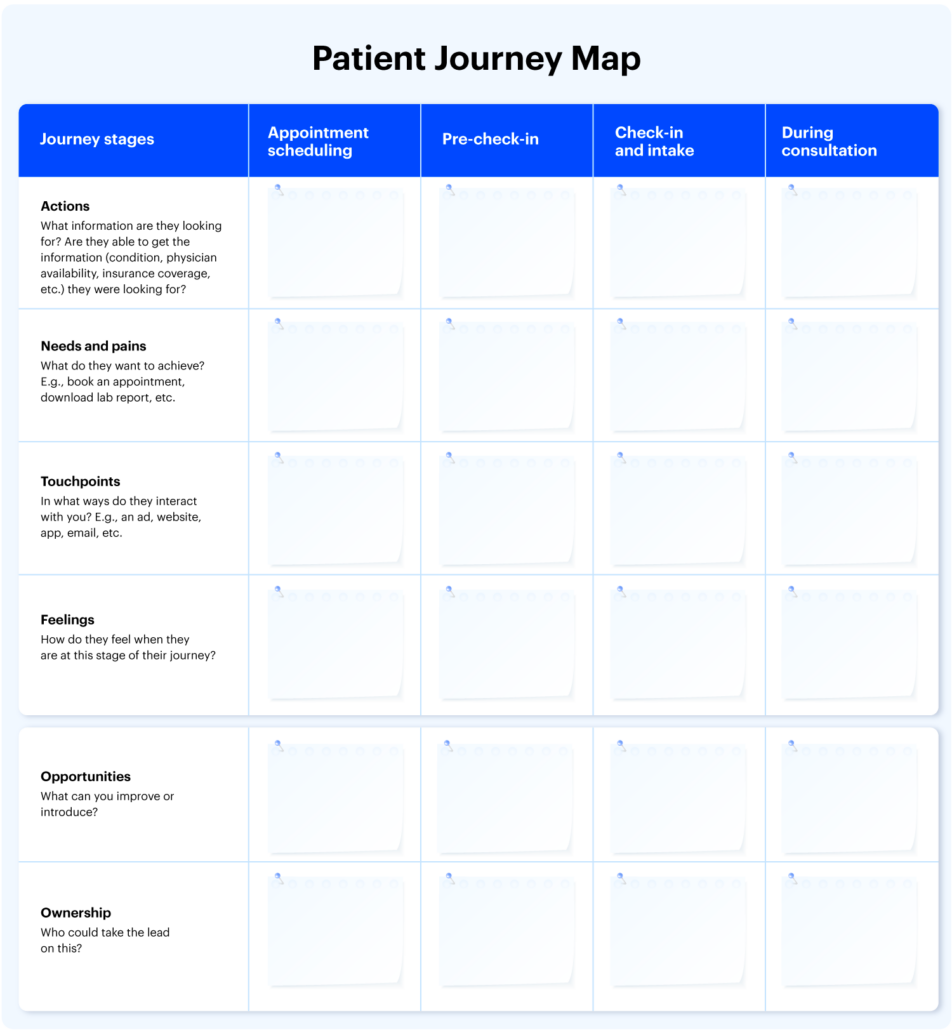

Patient journey mapping is an emerging field of research that uses various methods to map and report evidence relating to patient experiences and interactions with healthcare providers, services, and systems. This research often involves the development of visual, narrative, and descriptive maps or tables, which describe patient journeys and transitions into, through, and out of health services. This methods corner paper presents an overview of how patient journey mapping has been conducted within the health sector, providing cardiovascular examples. It introduces six key steps for conducting patient journey mapping and describes the opportunities and benefits of using patient journey mapping and future implications of using this approach.

Acquire an understanding of patient journey mapping and the methods and steps employed.

Examine practical and clinical examples in which patient journey mapping has been adopted in cardiac care to explore the perspectives and experiences of patients, family members, and healthcare professionals.

Quality and safety guidelines in healthcare services are increasingly encouraging and mandating engagement of patients, clients, and consumers in partnerships. 1 The aim of many of these partnerships is to consider how health services can be improved, in relation to accessibility, service delivery, discharge, and referral. 2 , 3 Patient journey mapping is a research approach increasingly being adopted to explore these experiences in healthcare. 3

a patient-oriented project that has been undertaken to better understand barriers, facilitators, experiences, interactions with services and/or outcomes for individuals and/or their carers, and family members as they enter, navigate, experience and exit one or more services in a health system by documenting elements of the journey to produce a visual or descriptive map. 3

It is an emerging field with a clear patient-centred focus, as opposed to studies that track patient flow, demand, and movement. As a general principle, patient journey mapping projects will provide evidence of patient perspectives and highlight experiences through the patient and consumer lens.

Patient journey mapping can provide significant insights that enable responsive and context-specific strategies for improving patient healthcare experiences and outcomes to be designed and implemented. 3–6 These improvements can occur at the individual patient, model of care, and/or health system level. As with other emerging methodologies, questions have been raised regarding exactly how patient journey mapping projects can best be designed, conducted, and reported. 3

In this methods paper, we provide an overview of patient journey mapping as an emergent field of research, including reasons that mapping patient journeys might be considered, methods that can be adopted, the principles that can guide patient journey mapping data collection and analysis, and considerations for reporting findings and recognizing the implications of findings. We summarize and draw on five cardiovascular patient journey mapping projects, as examples.

One of the most appealing elements of the patient journey mapping field of research is its focus on illuminating the lived experiences of patients and/or their family members, and the health professionals caring for them, methodically and purposefully. Patient journey mapping has an ability to provide detailed information about patient experiences, gaps in health services, and barriers and facilitators for access to health services. This information can be used independently, or alongside information from larger data sets, to adapt and improve models of care relevant to the population that is being investigated. 3

To date, the most frequent reason for adopting this approach is to inform health service redesign and improvement. 3 , 7 , 8 Other reasons have included: (i) to develop a deeper understanding of a person’s entire journey through health systems; 3 (ii) to identify delays in diagnosis or treatment (often described as bottlenecks); 9 (iii) to identify gaps in care and unmet needs; (iv) to evaluate continuity of care across health services and regions; 10 (v) to understand and evaluate the comprehensiveness of care; 11 (vi) to understand how people are navigating health systems and services; and (vii) to compare patient experiences with practice guidelines and standards of care.

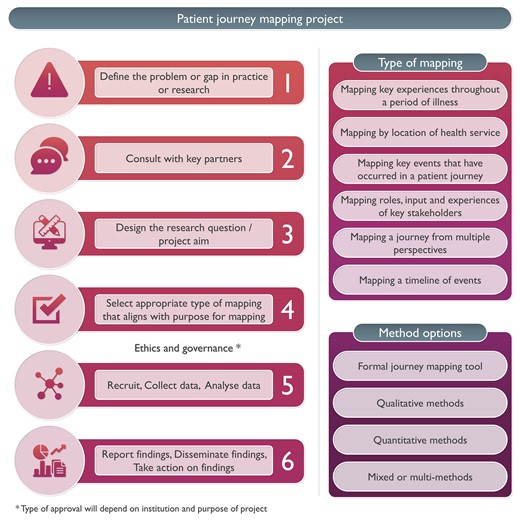

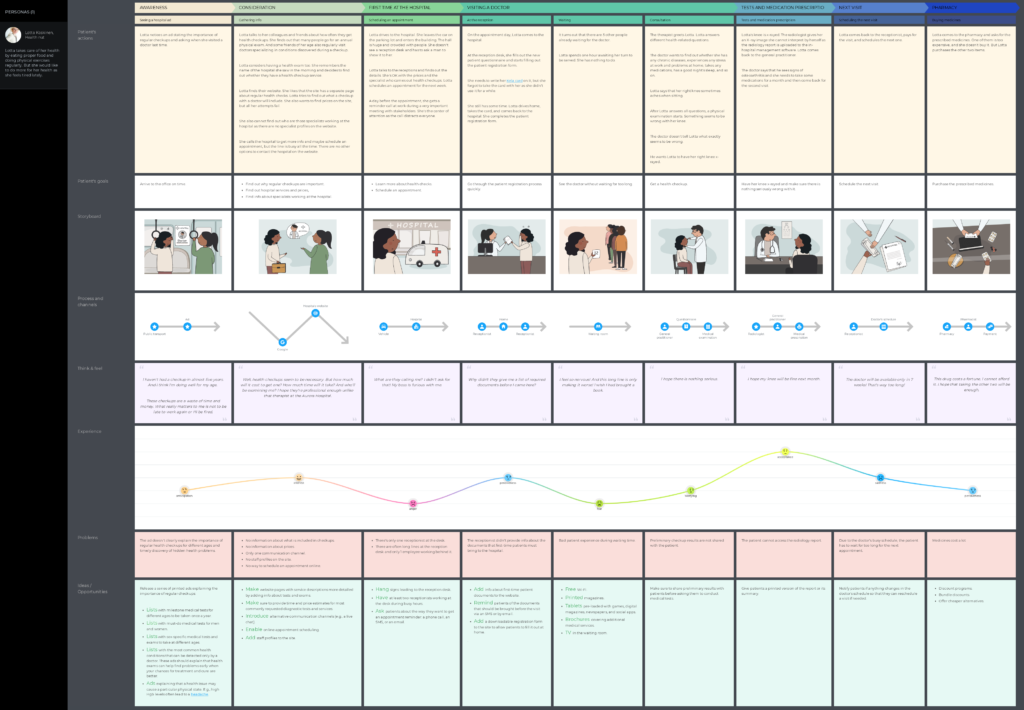

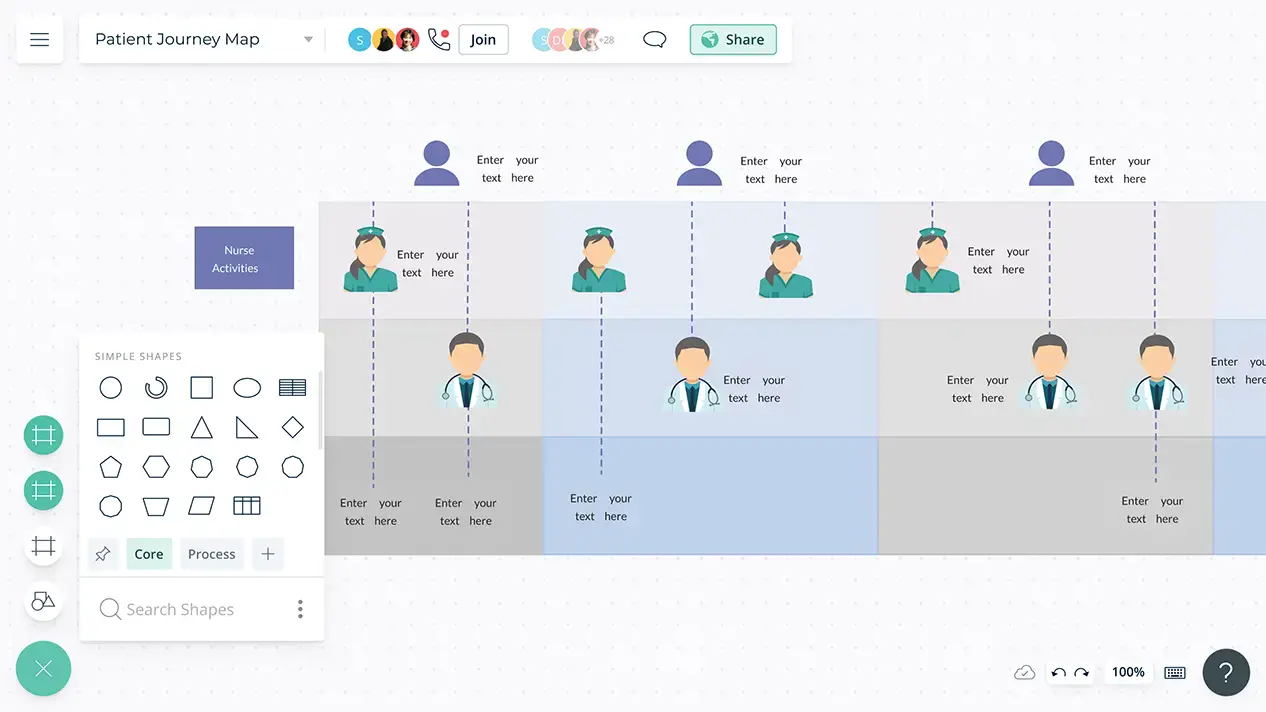

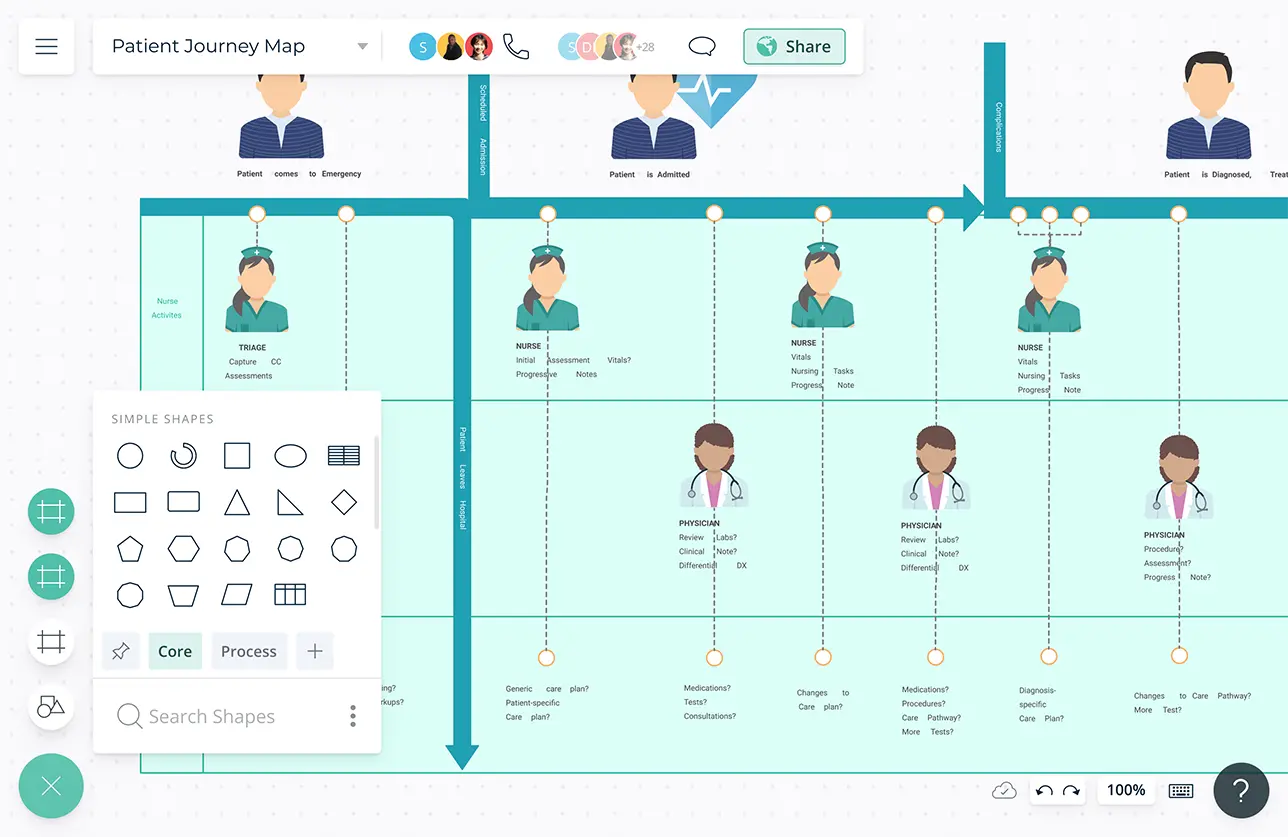

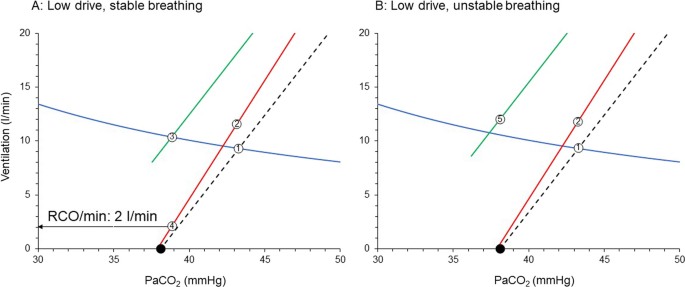

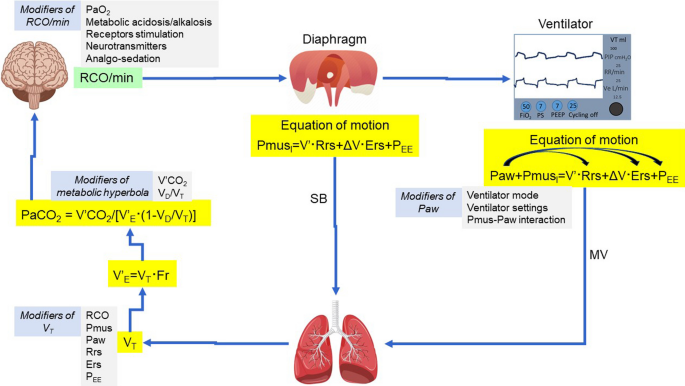

Patient journey mapping approaches frequently use six broad steps that help facilitate the preparation and execution of research projects. These are outlined in the Central illustration . We acknowledge that not all patient journey mapping approaches will follow the order outlined in the Central illustration , but all steps need to be considered at some point throughout each project to ensure that research is undertaken rigorously, appropriately, and in alignment with best practice research principles.

Steps for conducing patient journey mapping.

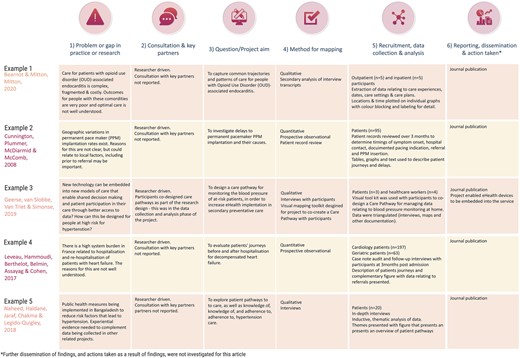

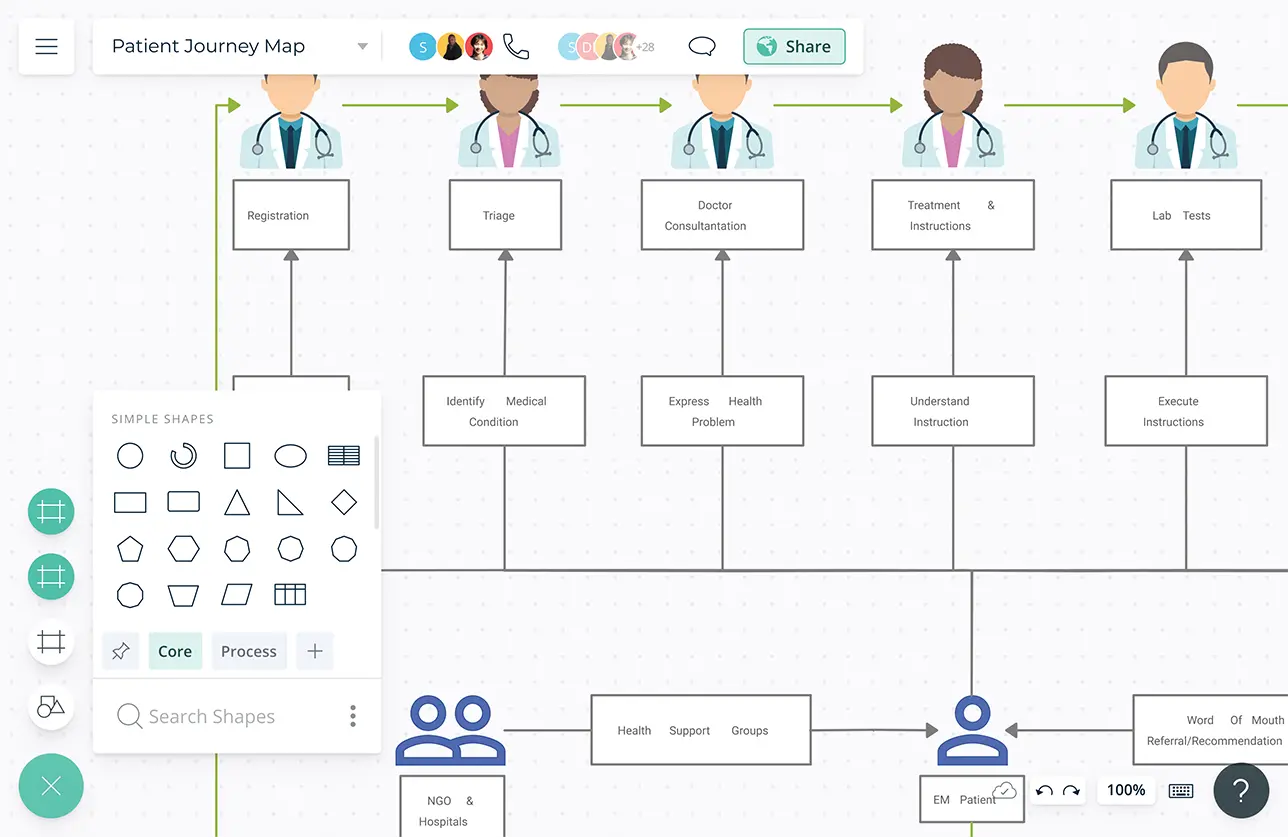

Five cardiovascular patient journey mapping research examples have been included in Figure 1 , 12–16 to provide specific context and illustrate these six steps. For each of these examples, the problem or gap in practice or research, consultation processes, research question or aim, type of mapping, methods, and reporting of findings have been extracted. Each of these steps is then discussed, using these cardiovascular examples.

Examples of patient journey mapping projects.

Define the problem or gap in practice or research

Developing an understanding of a problem or gap in practice is essential for facilitating the design and development of quality research projects. In the examples outlined in Figure 1 , it is evident that clinical variation or system gaps have been explored using patient journey mapping. In the first two examples, populations known to have health vulnerabilities were explored—in Example 1, this related to comorbid substance use and physical illness, 13 and in Example 2, this related to geographical location. 13 Broader systems and societal gaps were explored in Examples 4 and 5, respectively, 15 , 16 and in Example 3, a new technologically driven solution for an existing model of care was tested for its ability to improve patient outcomes relating to hypertension. 14

Consultation, engagement, and partnership

Ideally, consultation with heathcare providers and/or patients would occur when the problem or gap in practice or research is being defined. This is a key principle of co-designed research. 17 Numerous existing frameworks for supporting patient involvement in research have been designed and were recently documented and explored in a systematic review by Greenhalgh et al . 18 While none of the five example studies included this step in the initial phase of the project, it is increasingly being undertaken in patient partnership projects internationally (e.g. in renal care). 17 If not in the project conceptualization phase, consultation may occur during the data collection or analysis phase, as demonstrated in Example 3, where a care pathway was co-created with participants. 14 We refer readers to Greenhalgh’s systematic review as a starting point for considering suitable frameworks for engaging participants in consultation, partnership, and co-design of patient journey mapping projects. 18

Design the research question/project aim

Conducting patient journey mapping research requires a thoughtful and systematic approach to adequately capture the complexity of the healthcare experience. First, the research objectives and questions should be clearly defined. Aspects of the patient journey that will be explored need to be identified. Then, a robust approach must be developed, taking into account whether qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods are more appropriate for the objectives of the study.

For example, in the cardiac examples in Figure 1 , the broad aims included mapping existing pathways through health services where there were known problems 12 , 13 , 15 , 16 and documenting the co-creation of a new care pathway using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods. 14

In traditional studies, questions that might be addressed in the area of patient movement in health systems include data collected through the health systems databases, such as ‘What is the length of stay for x population’, or ‘What is the door to balloon time in this hospital?’ In contrast, patient mapping journey studies will approach asking questions about experiences that require data from patients and their family members, e.g. ‘What is the impact on you of your length of stay?’, ‘What was your experience in being assessed and undergoing treatment for your chest pain?’, ‘What was your experience supporting this patient during their cardiac admission and discharge?’

Select appropriate type of mapping

The methods chosen for mapping need to align with the identified purpose for mapping and the aim or question that was designed in Step 3. A range of research methods have been used in patient journey mapping projects involving various qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods techniques and tools. 4 Some approaches use traditional forms of data collection, such as short-form and long-form patient interviews, focus groups, and direct patient observations. 18 , 19 Other approaches use patient journey mapping tools, designed and used with specific cultural groups, such as First Nations peoples using artwork, paintings, sand trays, and photovoice. 17 , 20 In the cardiovascular examples presented in Figure 1 , both qualitative and quantitative methods have been used, with interviews, patient record reviews, and observational techniques adopted to map patient journeys.

In a recent scoping review investigating patient journey mapping across all health care settings and specialities, six types of patient journey mapping were identified. 3 These included (i) mapping key experiences throughout a period of illness; (ii) mapping by location of health service; (iii) mapping by events that occurred throughout a period of illness; (iv) mapping roles, input, and experiences of key stakeholders throughout patient journeys; (v) mapping a journey from multiple perspectives; and (vi) mapping a timeline of events. 3 Combinations or variations of these may be used in cardiovascular settings in the future, depending on the research question, and the reasons mapping is being undertaken.

Recruit, collect data, and analyse data

The majority of health-focused patient journey mapping projects published to date have recruited <50 participants. 3 Projects with fewer participants tend to be qualitative in nature. In the cardiovascular examples provided in Figure 1 , participant numbers range from 7 14 to 260. 15 The 3 studies with <20 participants were qualitative, 12 , 14 , 16 and the 2 with 95 and 260 participants, respectively, were quantitative. 13 , 15 As seen in these and wider patient journey mapping examples, 3 participants may include patients, relatives, carers, healthcare professionals, or other stakeholders, as required, to meet the study objectives. These different participant perspectives may be analysed within each participant group and/or across the wider cohort to provide insights into experiences, and the contextual factors that shape these experiences.

The approach chosen for data collection and analysis will vary and depends on the research question. What differentiates data analysis in patient journey mapping studies from other qualitative or quantitative studies is the focus on describing, defining, or exploring the journey from a patient’s, rather than a health service, perspective. Dimensions that may, therefore, be highlighted in the analysis include timing of service access, duration of delays to service access, physical location of services relative to a patient’s home, comparison of care received vs. benchmarked care, placing focus on the patient perspective.

The mapping of individual patient journeys may take place during data collection with the use of mapping templates (tables, diagrams, and figures) and/or later in the analysis phase with the use of inductive or deductive analysis, mapping tables, or frameworks. These have been characterized and visually represented in a recent scoping review. 3 Representations of patient journeys can also be constructed through a secondary analysis of previously collected data. In these instances, qualitative data (i.e. interviews and focus group transcripts) have been re-analysed to understand whether a patient journey narrative can be extracted and reported. Undertaking these projects triggers a new research cycle involving the six steps outlined in the Central illustration . The difference in these instances is that the data are already collected for Step 5.

Report findings, disseminate findings, and take action on findings

A standardized, formal reporting guideline for patient journey mapping research does not currently exist. As argued in Davies et al ., 3 a dedicated reporting guide for patient journey mapping would be ill-advised, given the diversity of approaches and methods that have been adopted in this field. Our recommendation is for projects to be reported in accordance with formal guidelines that best align with the research methods that have been adopted. For example, COREQ may be used for patient journey mapping where qualitative methods have been used. 20 STROBE may be used for patient journey mapping where quantitative methods have been used. 21 Whichever methods have been adopted, reporting of projects should be transparent, rigorous, and contain enough detail to the extent that the principles of transparency, trustworthiness, and reproducibility are upheld. 3

Dissemination of research findings needs to include the research, healthcare, and broader communities. Dissemination methods may include academic publications, conference presentations, and communication with relevant stakeholders including healthcare professionals, policymakers, and patient advocacy groups. Based on the findings and identified insights, stakeholders can collaboratively design and implement interventions, programmes, or improvements in healthcare delivery that overcome the identified challenges directly and address and improve the overall patient experience. This cyclical process can hopefully produce research that not only informs but also leads to tangible improvements in healthcare practice and policy.

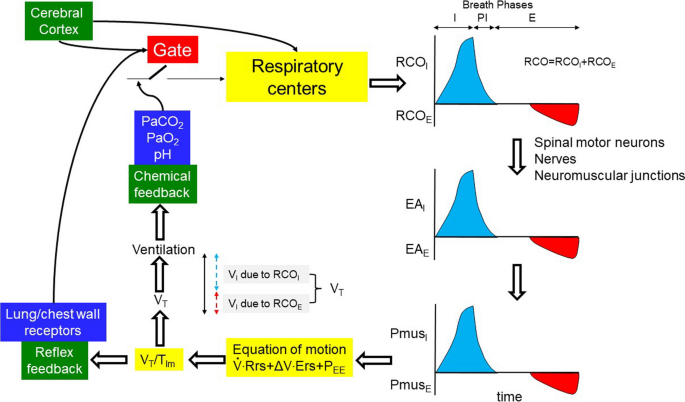

Patient journey mapping is typically a hands-on process, relying on surveys, interviews, and observational research. The technology that supports this research has, to date, included word processing software, and data analysis packages, such as NVivo, SPSS, and Stata. With the advent of more sophisticated technological tools, such as electronic health records, data analytics programmes, and patient tracking systems, healthcare providers and researchers can potentially use this technology to complement and enhance patient journey mapping research. 19 , 20 , 22 There are existing examples where technology has been harnessed in patient journey. Lee et al . used patient journey mapping to verify disease treatment data from the perspective of the patient, and then the authors developed a mobile prototype that organizes and visualizes personal health information according to the patient-centred journey map. They used a visualization approach for analysing medical information in personal health management and examined the medical information representation of seven mobile health apps that were used by patients and individuals. The apps provide easy access to patient health information; they primarily import data from the hospital database, without the need for patients to create their own medical records and information. 23

In another example, Wauben et al. 19 used radio frequency identification technology (a wireless system that is able to track a patient journey), as a component of their patient journey mapping project, to track surgical day care patients to increase patient flow, reduce wait times, and improve patient and staff satisfaction.

Patient journey mapping has emerged as a valuable research methodology in healthcare, providing a comprehensive and patient-centric approach to understanding the entire spectrum of a patient’s experience within the healthcare system. Future implications of this methodology are promising, particularly for transforming and redesigning healthcare delivery and improving patient outcomes. The impact may be most profound in the following key areas:

Personalized, patient-centred care : The methodology allows healthcare providers to gain deep insights into individual patient experiences. This information can be leveraged to deliver personalized, patient-centric care, based on the needs, values, and preferences of each patient, and aligned with guideline recommendations, healthcare professionals can tailor interventions and treatment plans to optimize patient and clinical outcomes.

Enhanced communication, collaboration, and co-design : Mapping patient interactions with health professionals and journeys within and across health services enables specific gaps in communication and collaboration to be highlighted and potentially informs responsive strategies for improvement. Ideally, these strategies would be co-designed with patients and health professionals, leading to improved care co-ordination and healthcare experience and outcomes.

Patient engagement and empowerment : When patients are invited to share their health journey experiences, and see visual or written representations of their journeys, they may come to understand their own health situation more deeply. Potentially, this may lead to increased health literacy, renewed adherence to treatment plans, and/or self-management of chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease. Given these benefits, we recommend that patients be provided with the findings of research and quality improvement projects with which they are involved, to close the loop, and to ensure that the findings are appropriately disseminated.

Patient journey mapping is an emerging field of research. Methods used in patient journey mapping projects have varied quite significantly; however, there are common research processes that can be followed to produce high-quality, insightful, and valuable research outputs. Insights gained from patient journey mapping can facilitate the identification of areas for enhancement within healthcare systems and inform the design of patient-centric solutions that prioritize the quality of care and patient outcomes, and patient satisfaction. Using patient journey mapping research can enable healthcare providers to forge stronger patient–provider relationships and co-design improved health service quality, patient experiences, and outcomes.

None declared.

Farmer J , Bigby C , Davis H , Carlisle K , Kenny A , Huysmans R , et al. The state of health services partnering with consumers: evidence from an online survey of Australian health services . BMC Health Serv Res 2018 ; 18 : 628 .

Google Scholar

Kelly J , Dwyer J , Mackean T , O’Donnell K , Willis E . Coproducing Aboriginal patient journey mapping tools for improved quality and coordination of care . Aust J Prim Health 2017 ; 23 : 536 – 542 .

Davies EL , Bulto LN , Walsh A , Pollock D , Langton VM , Laing RE , et al. Reporting and conducting patient journey mapping research in healthcare: a scoping review . J Adv Nurs 2023 ; 79 : 83 – 100 .

Ly S , Runacres F , Poon P . Journey mapping as a novel approach to healthcare: a qualitative mixed methods study in palliative care . BMC Health Serv Res 2021 ; 21 : 915 .

Arias M , Rojas E , Aguirre S , Cornejo F , Munoz-Gama J , Sepúlveda M , et al. Mapping the patient’s journey in healthcare through process mining . Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020 ; 17 : 6586 .

Natale V , Pruette C , Gerohristodoulos K , Scheimann A , Allen L , Kim JM , et al. Journey mapping to improve patient-family experience and teamwork: applying a systems thinking tool to a pediatric ambulatory clinic . Qual Manag Health Care 2023 ; 32 : 61 – 64 .

Cherif E , Martin-Verdier E , Rochette C . Investigating the healthcare pathway through patients’ experience and profiles: implications for breast cancer healthcare providers . BMC Health Serv Res 2020 ; 20 : 735 .

Gilburt H , Drummond C , Sinclair J . Navigating the alcohol treatment pathway: a qualitative study from the service users’ perspective . Alcohol Alcohol 2015 ; 50 : 444 – 450 .

Gichuhi S , Kabiru J , M’Bongo Zindamoyen A , Rono H , Ollando E , Wachira J , et al. Delay along the care-seeking journey of patients with ocular surface squamous neoplasia in Kenya . BMC Health Serv Res 2017 ; 17 : 485 .

Borycki EM , Kushniruk AW , Wagner E , Kletke R . Patient journey mapping: integrating digital technologies into the journey . Knowl Manag E-Learn 2020 ; 12 : 521 – 535 .

Barton E , Freeman T , Baum F , Javanparast S , Lawless A . The feasibility and potential use of case-tracked client journeys in primary healthcare: a pilot study . BMJ Open 2019 ; 9 : e024419 .

Bearnot B , Mitton JA . “You’re always jumping through hoops”: journey mapping the care experiences of individuals with opioid use disorder-associated endocarditis . J Addict Med 2020 ; 14 : 494 – 501 .

Cunnington MS , Plummer CJ , McDiarmid AK , McComb JM . The patient journey from symptom onset to pacemaker implantation . QJM 2008 ; 101 : 955 – 960 .

Geerse C , van Slobbe C , van Triet E , Simonse L . Design of a care pathway for preventive blood pressure monitoring: qualitative study . JMIR Cardio 2019 ; 3 : e13048 .

Laveau F , Hammoudi N , Berthelot E , Belmin J , Assayag P , Cohen A , et al. Patient journey in decompensated heart failure: an analysis in departments of cardiology and geriatrics in the Greater Paris University Hospitals . Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2017 ; 110 : 42 – 50 .

Naheed A , Haldane V , Jafar TH , Chakma N , Legido-Quigley H . Patient pathways and perceptions of treatment, management, and control Bangladesh: a qualitative study . Patient Prefer Adherence 2018 ; 12 : 1437 – 1449 .

Bateman S , Arnold-Chamney M , Jesudason S , Lester R , McDonald S , O’Donnell K , et al. Real ways of working together: co-creating meaningful Aboriginal community consultations to advance kidney care . Aust N Z J Public Health 2022 ; 46 : 614 – 621 .

Greenhalgh T , Hinton L , Finlay T , Macfarlane A , Fahy N , Clyde B , et al. Frameworks for supporting patient and public involvement in research: systematic review and co-design pilot . Health Expect 2019 ; 22 : 785 – 801 .

Wauben LSGL , Guédon ACP , de Korne DF , van den Dobbelsteen JJ . Tracking surgical day care patients using RFID technology . BMJ Innov 2015 ; 1 : 59 – 66 .

Tong A , Sainsbury P , Craig J . Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups . Int J Qual Health Care 2007 ; 19 : 349 – 357 .

von Elm E , Altman DG , Egger M , Pocock SJ , Gøtzsche PC , Vandenbroucke JP , et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies . Lancet 2007 ; 370 (9596): 1453 – 1457 .

Wilson A , Mackean T , Withall L , Willis EM , Pearson O , Hayes C , et al. Protocols for an Aboriginal-led, multi-methods study of the role of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers, practitioners and Liaison officers in quality acute health care . J Aust Indigenous HealthInfoNet 2022 ; 3 : 1 – 15 .

Lee B , Lee J , Cho Y , Shin Y , Oh C , Park H , et al. Visualisation of information using patient journey maps for a mobile health application . Appl Sci 2023 ; 13 : 6067 .

Author notes

Email alerts, citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1873-1953

- Print ISSN 1474-5151

- Copyright © 2024 European Society of Cardiology

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Case studies

- Expert advice

Patient journey mapping: what it is, its benefits, and how to do it

We've all been patients at some point, but our journeys were not the same. Patient journey mapping holds the key to unraveling this mystery, providing a strategic lens into the diverse pathways individuals tread throughout their healthcare experiences.

In this article, we'll explore the pivotal role of patient journey mapping in the healthcare industry, uncovering its profound benefits for both providers and patients. From amplifying patient satisfaction to streamlining operational processes, the impact is transformative.

But how does one embark on this journey of understanding and improvement? We'll guide you through the essential steps and considerations, offering insights into the art of crafting a meaningful healthcare patient journey map.

Join us as we peel back the layers of patient experience journey mapping. This powerful tool not only illuminates the complexities of healthcare but also empowers providers to reshape and enhance the patient experience.

- 1.1 Difference from other customer journeys

- 2 Patient journey mapping benefits

- 3 Patient journey stages

- 4.1 Clinical journey maps

- 4.2 Service delivery maps

- 4.3 Digital journey maps

- 4.4 Chronic disease management maps

- 4.5 Emergency care journey maps

- 4.6 Pediatric patient journey maps

- 4.7 Palliative care maps

- 5 How to do patient journey mapping?

- 6.1 Patient-centered care

- 6.2 Streamlined access to care

- 6.3 Effective communication

- 6.4 Education and empowerment

- 6.5 Care coordination

- 6.6 Technology integration

- 6.7 Feedback and continuous improvement

- 6.8 Cultural competency

- 6.9 Emotional support

- 6.10 Efficient billing and financial assistance

- 7 Templates

- 8 Wrapping up

What is a patient journey?

A patient journey is the entire process a person goes through when seeking and receiving a healthcare service. It covers everything from first noticing symptoms or realizing the need for care and medical attention to finally resolving the health issue. The journey involves patient interactions with healthcare professionals, diagnostic procedures, treatment activities, and follow-up care.

Mapping and understanding the patient journey can help boost the quality of hospital care and improve patient satisfaction. By pinpointing challenges, patient communication gaps, and areas for enhancement, care providers can refine their services to better cater to patients' needs. It also contributes to promoting patient-centered care, shifting the focus beyond just treating diseases to considering the overall well-being and experience of the patient.

Difference from other customer journeys

While the concept of patient journey mapping is similar to customer journey mapping , there are unique aspects specific to the healthcare domain. This is how a patient journey differs from any other customer journey:

- Emotional intensity. Health-related experiences often involve heightened emotions, including fear, anxiety, uncertainty, a sense of losing control, and a dependence on others. The emotional aspect is more pronounced in patient journeys compared to customer journeys in most industries.

- Complexity and uncertainty. Healthcare journeys often involve multiple stakeholders, various diagnostic and treatment options, and inherent uncertainties. Navigating these complexities requires a different approach compared to more straightforward consumer experiences. Comparing buying eyeglasses online and visiting a doctor — both are experiences, but how different they are!

- Regulatory and ethical considerations. Healthcare is heavily regulated, and ethical considerations play a significant role there. Patient journeys must align with regulatory standards and ethical principles that other industries don’t have.

- Clinical decision points. Patient journeys involve critical clinical decision points, such as diagnosis and treatment choices. These decisions not only impact the patient's health but also influence the overall trajectory of the journey.

- Care continuum. Patient journeys often extend beyond a single episode of care. They may involve long-term management, follow-up appointments, and ongoing support, creating a continuous care continuum.

- Interdisciplinary collaboration. Healthcare is often delivered by a team of professionals from different disciplines. The patient journey may involve collaboration among physicians, nurses, specialists, and other healthcare providers.

Patient journey mapping benefits

Mapping a patient journey offers a range of benefits that contribute to improving the overall quality of healthcare delivery. Here are some key advantages:

- Visualization of the entire patient journey helps healthcare providers identify critical patient journey touchpoints that impact patient satisfaction and experience and require immediate attention. By paying more attention to these touchpoints, you ensure a more positive overall journey.

- Gaps in care and challenges are highlighted among healthcare professionals. Addressing these issues ensures a more seamless and collaborative approach to patient care.

- Pain points and barriers become evident, enabling healthcare providers to proactively address issues that may hinder effective care delivery.

- Understanding individual patient journeys allows for more personalized ongoing care plans. Tailoring interventions to specific needs and preferences improves patient engagement and outcomes.

- By mapping a patient journey, you can identify resource-intensive stages and areas where efficiency can be improved, enabling a healthcare organization to allocate resources more effectively.

- It's a great way to identify opportunities for smoother transitions between different stages of care, ensuring continuity and preventing gaps in treatment.

- It becomes clear where patient involvement in the decision-making process can contribute to their healthcare journey.

Example: Tom, recovering from surgery, feels more empowered as his healthcare team provides clear post-operative care instructions, making him an active participant in his recovery.

In summary, patient journey mapping provides a comprehensive framework for healthcare improvement, addressing specific challenges at each stage and leading to tangible enhancements in patient experience, communication, and overall care delivery.

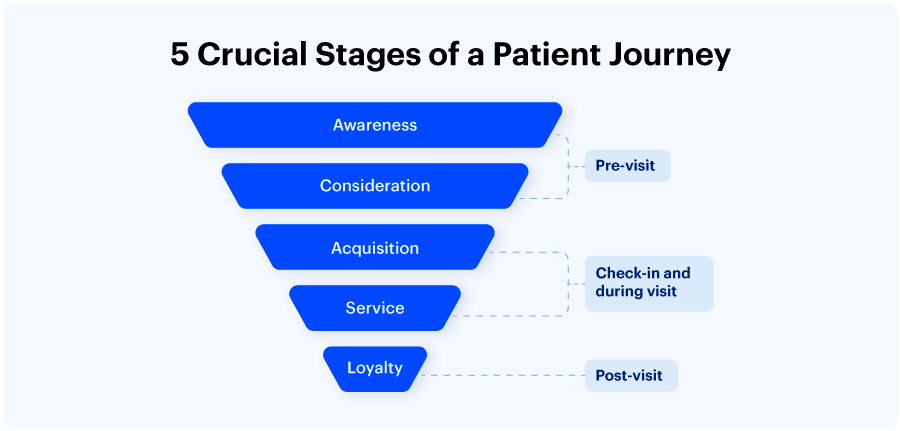

Patient journey stages

Patient journeys can differ, and if we take a broad perspective, some key stages would include:

Awareness

This stage involves the patient recognizing symptoms and becoming aware of a potential health issue.

- Key considerations: Pay attention to how patients identify and interpret their symptoms, as well as the information sources they consult.

Example: John notices persistent joint pain and, through online research, suspects it might be arthritis. His journey begins with a heightened awareness of his symptoms.

Seeking information

Patients actively look for information to understand their symptoms, potential causes, and the importance of consulting a healthcare professional.

- Key considerations: Review the information sources patients use and how well they understand the need for professional medical advice.

- Example: Emily researches her persistent cough online, learning about various respiratory conditions and recognizing the importance of seeing a doctor for an accurate diagnosis.

First contact

This marks the initial interaction with the healthcare system, typically through scheduling an appointment with a primary care physician.

- Key considerations: Assess the ease of access to healthcare services and the patient's initial experience with medical professionals.

- Example: Alex schedules an appointment with his family doctor to discuss recent changes in his vision, initiating his journey within the healthcare system.

Diagnostic process

Patients undergo diagnostic tests to identify the root cause of their symptoms.

- Key considerations: Examine the efficiency of the diagnostic process and the clarity of communication about the tests.

- Example: Maria undergoes blood tests and imaging to determine the cause of her abdominal pain, marking the diagnostic phase of her journey.

Treatment planning

Patients receive a diagnosis, and healthcare providers collaborate on creating a personalized treatment plan.

- Key considerations: Evaluate how well the diagnosis is communicated and involve patients in treatment decisions.

- Example: Emily receives a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Her healthcare team takes the time to explain the condition, discusses various treatment options, and actively involves her in deciding on a comprehensive plan that combines medication, physical therapy, and lifestyle adjustments.

Treatment and clinical care service

Patients initiate the recommended treatment plan, experiencing the day-to-day challenges and improvements associated with their patient journey in a hospital.

- Key considerations: Monitor treatment adherence, side effects, and the patient's overall experience during this active phase.

- Example: Sarah starts chemotherapy for her cancer, navigating the treatment process with the support of her healthcare team.

Psychological support

Patients deal with the emotional toll of managing a health condition, including anxiety, frustration, or isolation.

- Key considerations: Acknowledge and address the emotional aspects of the journey, providing resources for mental health support.

- Example: James copes with the emotional challenges of managing chronic pain, seeking counseling to navigate the psychological impact.

Regular checkups

Patients undergo routine checkups to monitor their health status and adjust treatment plans as needed.

- Key considerations: Ensure consistent communication and scheduling of regular checkups to track progress and address any emerging issues.

- Example: Sarah, diagnosed with hypertension, attends regular checkups where the healthcare team monitors blood pressure, discusses lifestyle adjustments, and ensures medication efficacy. The routine checkups create a proactive approach to managing her condition.

Patients provide feedback on their experiences, allowing healthcare providers to refine and tailor their care.

- Key considerations: Establish mechanisms for patients to share feedback easily and transparently, encouraging an open dialogue.

- Example: John shares his experiences with a new treatment plan, providing feedback on its effectiveness, side effects, and overall impact on his daily life. This feedback loop allows the healthcare team to make timely adjustments and improve the patient's journey.

The stages may vary based on diverse scenarios and individual health circumstances. For instance, when a patient undergoes surgery or faces an acute medical event, the trajectory of their journey can diverge significantly from a more routine healthcare experience.

Factors such as the need for emergency care, hospitalization, and specialized interventions can introduce unique stages and considerations. Additionally, variations may arise due to the specific nature of medical conditions, treatments, and the individual preferences and needs of patients.

Recognizing this variability is crucial for comprehensive journey mapping, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of the patient experience across different healthcare contexts.

Types of healthcare journey maps

Healthcare journey maps can take various forms depending on their focus, purpose, and the specific aspects of the patient experience they aim to understand.

Here are a few types of healthcare journey maps:

Clinical journey maps

Focus: Emphasize the clinical aspects of a patient's experience, including diagnosis, treatment, and recovery.

Purpose: Help healthcare providers understand the medical processes and interventions involved in the patient's journey.

Example: A clinical journey map for a cancer patient would detail the steps from initial symptoms to diagnosis, treatment modalities, and post-treatment care.

Service delivery maps

Focus: Highlight the various touchpoints and services a patient encounters throughout their healthcare journey. Then, detail the back and front processes your team does or has to do during each stage.

Purpose: Enable healthcare organizations to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of service delivery.

Example: Mapping the service delivery for a patient undergoing surgery, including preoperative consultations, surgical procedures, and post-operative care.

Digital journey maps

Focus: Examine the patient's interaction with digital tools and technologies, such as online portals, mobile apps, and telehealth platforms.

Purpose: Help improve the digital aspects of patient engagement and communication.

Example: Mapping the patient's journey when using a telehealth platform for virtual consultations, prescription refills, and accessing medical records.

Chronic disease management maps

Focus: Explore the long-term journey of patients managing chronic conditions.

Purpose: Aid in understanding the challenges and opportunities for supporting patients in their ongoing self-management.

Example: A journey map for a diabetes patient would encompass regular monitoring, medication management, lifestyle adjustments, and periodic checkups.

Emergency care journey maps

Focus: Examine the patient’s experience during emergencies, from the onset of symptoms to emergency room admission and follow-up care.

Purpose: Help optimize response times, communication, and the overall emergency care process.

Example: Mapping the journey of a patient experiencing chest pain, from the initial call to emergency services to the triage process and subsequent cardiac care.

Pediatric patient journey maps

Focus: Tailored specifically for the unique needs and considerations of pediatric patients and their families.

Purpose: Address the emotional and practical aspects of pediatric healthcare experiences.

Example: Such a map is good for a child undergoing surgery to consider the role of parents, age-appropriate communication, and post-operative care.

Palliative care maps

Focus: Center on the patient's journey when facing serious illness, with a focus on providing comfort and support.

Purpose: Enhance the quality of life for patients and their families during end-of-life care.

Example: This kind of journey map suits a patient receiving palliative care when considering symptom management, emotional support, and coordination of services.

The mentioned types of maps cover different patient scenarios and clinical cases. There can also be "AS-IS" and "TO-BE" maps, reflecting the current state of the journey and the desired one, respectively.

All these types of healthcare journey maps offer a nuanced understanding of the diverse aspects of patient experiences, allowing healthcare providers and organizations to tailor their services to meet the unique needs of different patient populations.

How to do patient journey mapping?

Mapping a patient's journey is a thorough process that needs careful planning, teamwork, and analysis. Here's a guide on how to do it:

- Define the objectives

Clearly articulate the goals of the patient journey mapping exercise. Determine what aspects of the patient experience you want to understand and improve. All involved parties should be aware of these goals and agree with them.

- Assemble a cross-functional team

Form a team that includes representatives from various departments, including healthcare providers, administrative staff, patient advocates, and anyone involved in the patient experience.

- Do research

Conduct thorough research to gather quantitative and qualitative data related to the patient experience. This may involve analyzing patient records, studying existing feedback, diving into analytics and market research, and reviewing relevant literature on best practices in healthcare.

- Select a patient segment

Identify a specific patient segment or persona to focus on. This could be based on demographics, health conditions, or specific healthcare services.

Tip: You can leverage your segments or patient personas to craft an empathy map , which is particularly valuable in healthcare.

- Conduct stakeholder interviews

Interview stakeholders, including healthcare professionals and administrative staff. Gather insights into their perspectives on the patient journey, pain points, and opportunities for improvement.

- Define the stages

Outline the patient journey by mapping out each stage and interaction with the healthcare system. This can include pre-visit, during a visit, and post-visit experiences.

Tip: To speed up the process, run a journey mapping workshop with your team. It will help with the next step, too.

- Create the patient journey map

Develop a visual representation of the patient journey. This can be a timeline or infographic that illustrates each stage, touchpoint, and the emotional experience of the patient.

- Identify pain points and opportunities

Analyze the collected data to pinpoint pain points, areas of friction, and opportunities for improvement. Consider emotional, logistical, and clinical aspects of the patient experience.

- Review and validate

Consider collaborative journey mapping . Share the draft patient journey map with stakeholders, including frontline staff and patients, to validate its accuracy. Incorporate feedback to ensure a comprehensive and realistic representation.

- Develop actionable plans

Generate specific, actionable plans based on the identified pain points and opportunities. Each initiative should be feasible, considering resources and organizational constraints.

- Prioritize and implement changes

Prioritize the recommendations based on impact and feasibility. Begin implementing changes that address the identified issues, whether they involve process improvements, staff training, or technology enhancements.

- Monitor and iterate

Continuously monitor the impact of implemented changes. Gather feedback from both staff and patients to understand the effectiveness of the improvements. Iterate on the patient journey map and make recommendations as needed.

- Measure your success

You can also establish KPIs to measure the success of any improvements made based on the patient journey mapping insights. These could include patient satisfaction scores, reduced wait times, or improved communication metrics.

- Document insights (optional)

And keep a record of the lessons learned during the patient journey mapping process. This documentation can inform future initiatives and contribute to ongoing efforts to enhance the patient experience.

- Promote a culture of continuous improvement

Foster a culture within the organization that values continuous improvement in patient care. Encourage ongoing feedback and regularly revisit your journey map to ensure its relevance over time.

By following these steps, healthcare organizations can gain valuable insights into the patient experience, leading to targeted improvements that enhance healthcare quality and patient satisfaction.

How to improve the patient journey?

Striving for a seamless patient journey involves enhancing the overall experience that individuals have when seeking and receiving healthcare services. Here are some strategies to consider:

Patient-centered care

- Prioritize patient needs and preferences.

- Emphasize education and empower patients to actively participate in their healthcare journey.

- Foster open communication and active listening.

Streamlined access to care

- Reduce wait times for appointments and procedures.

- Implement online scheduling and appointment reminders.

- Provide options for virtual consultations when appropriate.

Effective communication

- Ensure clear and understandable communication with patients.

- Provide information about treatment plans, medications, and follow-up care.

- Confirm that patients are well-informed about the potential risks and benefits of treatment options.

Education and empowerment

- Offer educational resources to help patients understand their conditions and treatment options.

- Encourage patients to actively participate in their health management.

- Provide tools for self-monitoring and self-management when possible.

Care coordination

- Improve collaboration and communication among healthcare providers to strengthen care coordination, ensuring a more cohesive and seamless experience for patients throughout their healthcare journey.

- Define and implement standardized protocols for communication and handovers between care teams, reducing the risk of errors and ensuring continuity of care.

- Implement remote monitoring technologies to track patients' health remotely, enabling timely interventions and reducing the need for frequent in-person visits.

Technology integration

- Adopt electronic health records (EHRs) for efficient information sharing.

- Use telemedicine to enhance accessibility and convenience.

- Implement mobile health apps for appointment reminders, medication management, and health tracking.

Feedback and continuous improvement

- Conduct regular surveys to gather specific insights into patient satisfaction, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of their experiences.

- Establish easily accessible channels for patients to provide real-time feedback, ensuring that their voices are heard promptly.

- Respond promptly to patient feedback, address concerns, and communicate any changes or resolutions, fostering a sense of responsiveness and accountability.

Cultural competency

- Train healthcare staff to be culturally competent and sensitive to diverse patient needs.

- Promote diversity in healthcare staff to reflect the communities served, fostering a more inclusive and culturally sensitive environment.

- Recognize and celebrate cultural awareness events within the healthcare setting, fostering an inclusive atmosphere that appreciates the richness of diverse traditions.

Emotional support

- Address the emotional and psychological aspects of healthcare.

- Provide resources for mental health and emotional well-being.

- Consider support groups or counseling services.

Efficient billing and financial assistance

- Simplify billing processes and provide clear information about costs.

- Offer financial assistance programs for patients in need.

- Communicate transparently about insurance coverage and out-of-pocket expenses.

Staff training:

- Train healthcare staff in patient-centered communication and empathy.

- Ensure staff is knowledgeable about the resources available to patients.

- Foster a culture of empathy and compassion in the healthcare environment.

By focusing on these aspects, healthcare providers can contribute to a more positive and effective patient journey. Regularly reassessing and adapting strategies based on feedback and evolving healthcare trends is crucial for ongoing improvement.

UXPressia already has some healthcare journey map examples:

- Surgical patient journey

This map focuses on the healthcare journey of a patient persona, Robin, from the moment when the patient understands that something is wrong to the recovery period. This journey is long and very detailed.

- Non-surgical patient journey

This map visualizes the journey of a patient, Lotta, who decides to undergo a checkup at a hospital. She schedules a visit, gets a consultation, takes some tests, and starts taking some medicine prescribed by her doctor.

More healthcare and well-being templates are available in our library.

Wrapping up

In wrapping up, think of patient journey mapping as a powerful tool reshaping the healthcare landscape, with the patient's experience taking center stage. It's like creating a roadmap that intricately traces every step of a patient's interaction within the healthcare system.

This deliberate mapping isn't just a plan; it's a compass guiding healthcare organizations toward key points where they can enhance patient satisfaction, simplify access to care, and cultivate a more compassionate and patient-focused healthcare environment. Investing in patient journey mapping is more than a strategy—it's a dedication to raising the bar in care quality, amplifying the patient's voice, and ensuring that every leg of the healthcare journey is characterized by empathy, understanding, and an unwavering pursuit of excellence in patient experience.

Related posts

Rate this post

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Process mapping the...

Process mapping the patient journey: an introduction

- Related content

- Peer review

- Timothy M Trebble , consultant gastroenterologist 1 ,

- Navjyot Hansi , CMT 2 1 ,

- Theresa Hydes , CMT 1 1 ,

- Melissa A Smith , specialist registrar 2 ,

- Marc Baker , senior faculty member 3

- 1 Department of Gastroenterology, Portsmouth Hospitals Trust, Portsmouth PO6 3LY

- 2 Department of Gastroenterology, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London

- 3 Lean Enterprise Academy, Ross-on-Wye, Hertfordshire

- Correspondence to: T M Trebble tim.trebble{at}porthosp.nhs.uk

- Accepted 15 July 2010

Process mapping enables the reconfiguring of the patient journey from the patient’s perspective in order to improve quality of care and release resources. This paper provides a practical framework for using this versatile and simple technique in hospital.

Healthcare process mapping is a new and important form of clinical audit that examines how we manage the patient journey, using the patient’s perspective to identify problems and suggest improvements. 1 2 We outline the steps involved in mapping the patient’s journey, as we believe that a basic understanding of this versatile and simple technique, and when and how to use it, is valuable to clinicians who are developing clinical services.

What information does process mapping provide and what is it used for?

Process mapping allows us to “see” and understand the patient’s experience 3 by separating the management of a specific condition or treatment into a series of consecutive events or steps (activities, interventions, or staff interactions, for example). The sequence of these steps between two points (from admission to the accident and emergency department to discharge from the ward) can be viewed as a patient pathway or process of care. 4

Improving the patient pathway involves the coordination of multidisciplinary practice, aiming to maximise clinical efficacy and efficiency by eliminating ineffective and unnecessary care. 5 The data provided by process mapping can be used to redesign the patient pathway 4 6 to improve the quality or efficiency of clinical management and to alter the focus of care towards activities most valued by the patient.

Process mapping has shown clinical benefit across a variety of specialties, multidisciplinary teams, and healthcare systems. 7 8 9 The NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement proposes a range of practical benefits using this approach (box 1). 6

Box 1 Benefits of process mapping 6

A starting point for an improvement project specific for your own place of work

Creating a culture of ownership, responsibility and accountability for your team

Illustrates a patient pathway or process, understanding it from a patient’s perspective

An aid to plan changes more effectively

Collecting ideas, often from staff who understand the system but who rarely contribute to change

An interactive event that engages staff

An end product (a process map) that is easy to understand and highly visual

Several management systems are available to support process mapping and pathway redesign. 10 11 A common technique, derived originally from the Japanese car maker Toyota, is known as lean thinking transformation. 3 12 This considers each step in a patient pathway in terms of the relative contribution towards the patient’s outcome, taken from the patient’s perspective: it improves the patient’s health, wellbeing, and experience (value adding) or it does not (non-value or “waste”) (box 2). 14 15 16

Box 2 The eight types of waste in health care 13

Defects —Drug prescription errors; incomplete surgical equipment

Overproduction —Inappropriate scheduling

Transportation —Distance between related departments

Waiting —By patients or staff

Inventory —Excess stores, that expire

Motion —Poor ergonomics

Overprocessing —A sledgehammer to crack a nut

Human potential —Not making the most of staff skills

Process mapping can be used to identify and characterise value and non-value steps in the patient pathway (also known as value stream mapping). Using lean thinking transformation to redesign the pathway aims to enhance the contribution of value steps and remove non-value steps. 17 In most processes, non-value steps account for nine times more effort than steps that add value. 18

Reviewing the patient journey is always beneficial, and therefore a process mapping exercise can be undertaken at any time. However, common indications include a need to improve patients’ satisfaction or quality or financial aspects of a particular clinical service.

How to organise a process mapping exercise

Process mapping requires a planned approach, as even apparently straightforward patient journeys can be complex, with many interdependent steps. 4 A process mapping exercise should be an enjoyable and creative experience for staff. In common with other audit techniques, it must avoid being confrontational or judgmental or used to “name, shame, and blame.” 8 19

Preparation and planning

A good first step is to form a team of four or five key staff, ideally including a member with previous experience of lean thinking transformation. The group should decide on a plan for the project and its scope; this can be visualised by using a flow diagram (fig 1 ⇓ ). Producing a rough initial draft of the patient journey can be useful for providing an overview of the exercise.

Fig 1 Steps involved in a process mapping exercise

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

The medical literature or questionnaire studies of patients’ expectations and outcomes should be reviewed to identify value adding steps involved in the management of the clinical condition or intervention from the patient’s perspective. 1 3

Data collection

Data collection should include information on each step under routine clinical circumstances in the usual clinical environment. Information is needed on waiting episodes and bottlenecks (any step within the patient pathway that slows the overall rate of a patient’s progress, normally through reduced capacity or availability 20 ). Using estimates of minimum and maximum time for each step reduces the influence of day to day variations that may skew the data. Limiting the number of steps (to below 60) aids subsequent analysis.

The techniques used for data collection (table 1 ⇓ ) each have advantages and disadvantages; a combination of approaches can be applied, contributing different qualitative or quantitative information. The commonly used technique of walking the patient journey includes interviews with patients and staff and direct observation of the patient journey and clinical environment. It allows the investigator to “see” the patient journey at first hand. Involving junior (or student) doctors or nurses as interviewers may increase the openness of opinions from staff, and time needed for data collection can be reduced by allotting members of the team to investigate different stages in the patient’s journey.

Data collection in process mapping

- View inline

Mapping the information

The process map should comprehensively represent the patient journey. It is common practice to draw the map by hand onto paper (often several metres long), either directly or on repositionable notes (fig 2 ⇓ ).

Fig 2 Section of a current state map of the endoscopy patient journey

Information relating to the steps or representing movement of information (request forms, results, etc) can be added. It is useful to obtain any missing information at this stage, either from staff within the meeting or by revisiting the clinical environment.

Analysing the data and problem solving

The map can be analysed by using a series of simple questions (box 3). The additional information can be added to the process map for visual representation. This can be helped by producing a workflow diagram—a map of the clinical environment, including information on patient, staff, and information movement (fig 3 ⇓ ). 18

Box 3 How to analyse a process map 6

How many steps are involved?

How many staff-staff interactions (handoffs)?

What is the time for each step and between each step?

What is the total time between start and finish (lead time)?

When does a patient join a queue, and is it a regular occurrence?

How many non-value steps are there?

What do patients complain about?

What are the problems for staff?

Fig 3 Workflow diagram of current state endoscopy pathway

Redesigning the patient journey

Lean thinking transformation involves redesigning the patient journey. 21 22 This will eliminate, combine and simplify non-value steps, 23 limit the impact of rate limiting steps (such as bottlenecks), and emphasise the value adding steps, making the process more patient-centred. 6 It is often useful to trial the new pathway and review its effect on patient management and satisfaction before attempting more sustained implementation.

Worked example: How to undertake a process mapping exercise

South Coast NHS Trust, a large district general hospital, plans to improve patient access to local services by offering unsedated endoscopy in two peripheral units. A consultant gastroenterologist has been asked to lead a process mapping exercise of the current patient journey to develop a fast track, high quality patient pathway.

In the absence of local data, he reviews the published literature and identifies key factors to the patient experience that include levels of discomfort during the procedure, time to discuss the findings with the endoscopist, and time spent waiting. 24 25 26 27 He recruits a team: an experienced performance manager, a sister from the endoscopy department, and two junior doctors.

The team drafts a map of the current endoscopy journey, using repositionable notes on the wall. This allows team members to identify the start (admission to the unit) and completion (discharge) points and the locations thought to be involved in the patient journey.

They decide to use a “walk the journey” format, interviewing staff in their clinical environments and allowing direct observation of the patient’s management.

The junior doctors visit the endoscopy unit over two days, building up rapport with the staff to ensure that they feel comfortable with being observed and interviewed (on a semistructured but informal basis). On each day they start at the point of admission at the reception office and follow the patient journey to completion.

They observe the process from staff and patient’s perspectives, sitting in on the booking process and the endoscopy procedure. They identify the sequence of steps and assess each for its duration (minimum and maximum times) and the factors that influence this. For some of the steps, they use a digital watch and notepad to check and record times. They also note staff-patient and staff-staff interactions and their function, and the recording and movement of relevant information.

Details for each step are entered into a simple table (table 2 ⇓ ), with relevant notes and symbols for bottlenecks and patients’ waits.

Patient journey for non-sedated upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

When data collection is complete, the doctor organises a meeting with the team. The individual steps of the patient journey are mapped on a single long section of paper with coloured temporary markers (fig 2 ⇑ ); additional information is added in different colours. A workflow diagram is drawn to show the physical route of the patient journey (fig 3 ⇑ ).

The performance manager calculates that the total patient journey takes a minimum of 50 minutes to a maximum of 345 minutes. This variation mainly reflects waiting times before a number of bottleneck steps.

Only five steps (14 to 17 and 22, table 2 ⇑ ) are considered both to add value and needed on the day of the procedure (providing patient information and consent can be obtained before the patient attends the department). These represent from 13 to 47 minutes. At its least efficient, therefore, only 4% of the patient journey (13 of 345 minutes) is spent in activities that contribute directly towards the patient’s outcome.

The team redesigns the patient journey (fig 4 ⇓ ) to increase time spent on value adding aspects but reduce waiting times, bottlenecks, and travelling distances. For example, time for discussing the results of the procedure is increased but the location is moved from the end of the journey (a bottleneck) to shortly after the procedure in the anteroom, reducing the patient’s waiting time and staff’s travelling distances.

Fig 4 Workflow diagram of future state endoscopy pathway

Implementing changes and sustaining improvements

The endoscopy staff are consulted on the new patient pathway, which is then piloted. After successful review two months later, including a patient satisfaction questionnaire, the new patient pathway is formally adopted in the peripheral units.

Further reading

Practical applications.

NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement ( https://www.institute.nhs.uk )—comprehensive online resource providing practical guidance on process mapping and service improvement

Lean Enterprise Academy ( http://www.leanuk.org )—independent body dedicated to lean thinking in industry and healthcare, through training and academic discussion; its publication, Making Hospitals Work 23 is a practical guide to lean transformation in the hospital environment

Manufacturing Institute ( http://www.manufacturinginstitute.co.uk )—undertakes courses on process mapping and lean thinking transformation within health care and industrial practice

Theoretical basis

Bircheno J. The new lean toolbox . 4th ed. Buckingham: PICSIE Books, 2008

Mould G, Bowers J, Ghattas M. The evolution of the pathway and its role in improving patient care. Qual Saf Health Care 2010 [online publication 29 April]

Layton A, Moss F, Morgan G. Mapping out the patient’s journey: experiences of developing pathways of care. Qual Health Care 1998; 7 (suppl):S30-6

Graban M. Lean hospitals, improving quality, patient safety and employee satisfaction . New York: Taylor & Francis, 2009

Womack JP, Jones DT. Lean thinking . 2nd ed. London: Simon & Schuster, 2003

Cite this as: BMJ 2010;341:c4078

Contributors: TMT designed the protocol and drafted the manuscript; TMT, MB, JH, and TH collected and analysed the data; all authors critically reviewed and contributed towards revision and production of the manuscript. TMT is guarantor.

Competing interests: MB is a senior faculty member carrying out research for the Lean Enterprise Academy and undertakes paid consultancies both individually and from Lean Enterprise Academy, and training fees for providing lean thinking in healthcare.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- ↵ Kollberg B, Dahlgaard JJ, Brehmer P. Measuring lean initiatives in health care services: issues and findings. Int J Productivity Perform Manage 2007 ; 56 : 7 -24. OpenUrl CrossRef

- ↵ Bevan H, Lendon R. Improving performance by improving processes and systems. In: Walburg J, Bevan H, Wilderspin J, Lemmens K, eds. Performance management in health care. Abingdon: Routeledge, 2006:75-85.

- ↵ Kim CS, Spahlinger DA, Kin JM, Billi JE. Lean health care: what can hospitals learn from a world-class automaker? J Hosp Med 2006 ; 1 : 191 -9. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Layton A, Moss F, Morgan G. Mapping out the patient’s journey: experiences of developing pathways of care. Qual Health Care 1998 ; 7 (suppl): S30 -6. OpenUrl

- ↵ Peterson KM, Kane DP. Beyond disease management: population-based health management. Disease management. Chicago: American Hospital Publishing, 1996.

- ↵ NHS Modernisation Agency. Process mapping, analysis and redesign. London: Department of Health, 2005;1-40.

- ↵ Taylor AJ, Randall C. Process mapping: enhancing the implementation of the Liverpool care pathway. Int J Palliat Nurs 2007 ; 13 : 163 -7. OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Ben-Tovim DI, Dougherty ML, O’Connell TJ, McGrath KM. Patient journeys: the process of clinical redesign. Med J Aust 2008 ; 188 (suppl 6): S14 -7. OpenUrl PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ King DL, Ben-Tovim DI, Bassham J. Redesigning emergency department patient flows: application of lean thinking to health care. Emerg Med Australas 2006 ; 18 : 391 -7. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Mould G, Bowers J, Ghattas M. The evolution of the pathway and its role in improving patient care. Qual Saf Health Care 2010 ; published online 29 April.

- ↵ Rath F. Tools for developing a quality management program: proactive tools (process mapping, value stream mapping, fault tree analysis, and failure mode and effects analysis). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008 ; 71 (suppl): S187 -90. OpenUrl PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Womack JP, Jones DT. Lean thinking. 2nd ed. London: Simon & Schuster, 2003.

- ↵ Graban M. Value and waste. In: Lean hospitals. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2009;35-56.

- ↵ Westwood N, James-Moore M, Cooke M. Going lean in the NHS. London: NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, 2007.

- ↵ Liker JK. The heart of the Toyota production system: eliminating waste. The Toyota way. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004;27-34.

- ↵ Womack JP, Jones DT. Introduction: Lean thinking versus Muda. In: Lean thinking. 2nd ed. London: Simon & Schuster, 2003:15-28.

- ↵ George ML, Rowlands D, Price M, Maxey J. Value stream mapping and process flow tools. Lean six sigma pocket toolbook. New York: McGraw Hill, 2005:33-54.

- ↵ Fillingham D. Can lean save lives. Leadership Health Serv 2007 ; 20 : 231 -41. OpenUrl CrossRef

- ↵ Benjamin A. Audit: how to do it in practice. BMJ 2008 ; 336 : 1241 -5. OpenUrl FREE Full Text

- ↵ Vissers J. Unit Logistics. In: Vissers J, Beech R, eds. Health operations management patient flow logistics in health care. Oxford: Routledge, 2005:51-69.

- ↵ Graban M. Overview of lean for hospital. Lean hospitals. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2009;19-33.

- ↵ Eaton M. The key lean concepts. Lean for practitioners. Penryn, Cornwall: Academy Press, 2008:13-28.

- ↵ Baker M, Taylor I, Mitchell A. Analysing the situation: learning to think differently. In: Making hospitals work. Ross-on-Wye: Lean Enterprise Academy, 2009:51-70.

- ↵ Ko HH, Zhang H, Telford JJ, Enns R. Factors influencing patient satisfaction when undergoing endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc 2009 ; 69 : 883 -91. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Del Rio AS, Baudet JS, Fernandez OA, Morales I, Socas MR. Evaluation of patient satisfaction in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007 ; 19 : 896 -900. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Seip B, Huppertz-Hauss G, Sauar J, Bretthauer M, Hoff G. Patients’ satisfaction: an important factor in quality control of gastroscopies. Scand J Gastroenterol 2008 ; 43 : 1004 -11. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Yanai H, Schushan-Eisen I, Neuman S, Novis B. Patient satisfaction with endoscopy measurement and assessment. Dig Dis 2008 ; 26 : 75 -9. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Employee Exit Interviews

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

- Market Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

- Experience Management

- Sector Specific

- Patient Experience

- Patient Journey

Try Qualtrics for free

The patient journey: what it is and how it’s vital for success.

10 min read In the digital age, the patient experience has become more complex but also more critical as it relates to patient retention, reimbursement, and patient satisfaction. In order to thrive in today’s healthcare landscape, it’s important to look at the patient journey when aiming to improve the patient experience.

Does your healthcare organization ask patients for feedback following clinical encounters? This is a common approach used to improve the patient experience . You may gather key insights about a specific encounter, but you’ll miss out on an untapped system of important patient interactions throughout the care journey .

Stay up-to-date on patient experience management trends with our guide

Improving patient experiences requires looking at the entire healthcare ecosystem. Patients communicate with their healthcare providers through a variety of channels, while interacting with a wide range of departments and individuals along the way.

To stand out in the market and provide an optimal experience for your patients , hospitals and health systems should look beyond clinical service delivery and begin patient journey mapping.

The patient journey is the entire sequence of events that begins when the patient first develops a need for clinical care and engages with your organization. It follows the patient’s steps as they navigate your healthcare system, from initial scheduling to treatment to continuous care.

The patient journey vs. the patient experience

Why is the patient journey important? Each touchpoint of the patient engagement journey, from a simple visit to your website to checking in for an appointment, has downstream effects that can help or hinder meeting patient needs.

As the patient experience evolves , it’s important to expand how you are listening to your patients in order to close gaps and make continuous improvements.

In recent years, emphasis on the patient experience has become the focus of regulatory programs and payment incentives. Many quality measures today center around collecting patient feedback on the healthcare experience.

To satisfy these measures and drive quality improvement efforts, many organizations turn to post-transactional patient satisfaction surveys . The feedback from these surveys often measures only a limited set of touchpoints while overlooking other critical data from the full patient journey.

A holistic view

Patient experience programs often hone in on clinical service delivery, and many regulatory programs focus solely on numerical scores to measure improvement. These approaches may fail to identify pain points occurring in dozens of patient interactions within a healthcare system.

A holistic view of the patient journey is the key to modernizing and strengthening your efforts to meet your patients’ needs . By breaking down silos into separate patient events, you can begin to identify blind spots where hidden challenges exist in your patient experiences.

By the time your patients engage with their care providers, they’ve likely interacted with your organization a number of times. These interactions can occur digitally, over the phone, or in person. Navigating your website, verifying insurance coverage, and scheduling an appointment are all examples of pain points that may be creating barriers to care.

It’s easy to assume any given touchpoint is more or less important than another. The fact is that each one provides unique value to the patient’s experience. Each of them plays a role in helping the patient achieve their goals.

Patient engagement with your organization doesn’t begin when the patient is examined by the healthcare provider, or even when they enter your medical facility. From initial awareness to ongoing care, the patient journey encompasses every separate interaction throughout the process of seeking, receiving, and continuing care within a health system.

There are several stages of the patient journey you should consider.

What triggers the patient’s need for care, and how does the patient learn about your organization?

- Quality ratings and online reputation

- Campaign management

- Community involvement

Consideration

What drives a patient to choose your organization over another?

- Coverage and benefits

- Healthcare provider search

What impacts your patient’s ability to receive care or support from your organization?

- Patient portal

- Call center

- Price transparency

Service delivery

What is your patient’s experience with their clinical care?

- Interaction with healthcare professionals

- Check-in and check-out

- Discharge process

Ongoing care

What type of patient engagement occurs after a visit?

- Wellness and care management

- Social determinants of health

- Population health